Abstract

Background

The clinical course of severe COVID-19 in cystic fibrosis (CF) is incompletely understood. We describe the use of alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) as a salvage therapy in a critically unwell patient with CF (PWCF) who developed COVID-19 while awaiting lung transplantation.

Methods

IV AAT was administered at 120 mg/kg/week for 4 consecutive weeks. Levels of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and soluble TNF receptor 1 (sTNFR1) were assessed at regular intervals in plasma, with IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and neutrophil elastase (NE) activity measured in airway secretions. Levels were compared to baseline and historic severe exacerbation measurements.

Results

Systemic and airway inflammatory markers were increased compared to both prior exacerbation and baseline levels, in particular IL-6, IL-1β and NE activity. Following each AAT dose, rapid decreases in each inflammatory parameter were observed. These were matched by marked clinical and radiographic improvement.

Conclusions

The results support further investigation of AAT as a COVID-19 therapeutic, and re-exploration of its use in CF.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Cystic fibrosis, Alpha-1 antitrypsin, Inflammation, Cytokinemia, Interleukin-1β, Interleukin-6, Neutrophil elastase, Anti-inflammatory

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global threat to health. Those with severe disease typically develop a febrile pro-inflammatory cytokinemia with accelerated progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1]. While SARS-CoV-2 infection in cystic fibrosis (CF) has previously been reported [2], the clinical and biochemical course of severe COVID-19 in the context of advanced CF remains incompletely understood.

We present the case of a 43 year old woman with CF who developed COVID-19 while an inpatient, following a ward-level outbreak. A precautionary nasopharyngeal swab obtained while the patient was asymptomatic was negative on a reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay. However, several days later following the onset of low-grade pyrexia, increased dyspnea and cough above baseline, a repeat swab was positive for COVID-19.

1.1. Pre-study clinical baseline and phenotype

The patient, who was diagnosed in early childhood, was homozygous for the p.Gly551Asp (previously termed G551D) mutation, and in late 2012 became one of the first Irish people with CF (PWCF) to receive ivacaftor. However, she had established structural airways disease and severely compromised pulmonary function at the time of commencement. Despite sustained improvements in body mass index and decreased exacerbation frequency, she remained chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophila, and an initial stabilization in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) gradually gave way to clinical decline (Fig. 1 ). Of relevance to COVID-19, Stenotrophomonas degrades the airway epithelial cell tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin, a pathogenic mechanism that may facilitate enhanced viral entry [3]. This process is likely mediated via secreted virulence factors including the extracellular serine proteases StmPR1, StmPR2, and StmPR3, and is also blocked by protease inhibition.

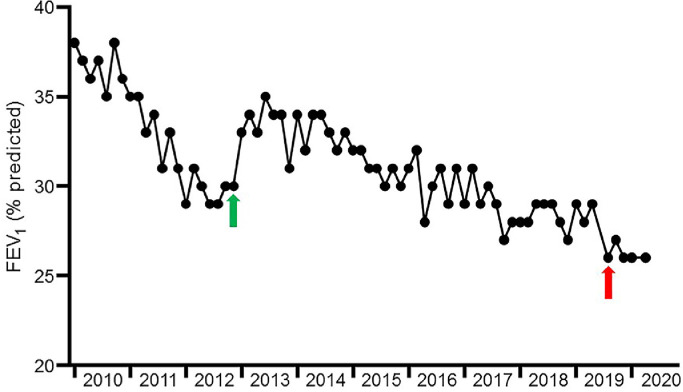

Fig. 1.

Lung function over time prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The patient demonstrated a progressive decrease in FEV1 between 2010 and late 2012. Commencement of ivacaftor in late 2012 (green arrow) resulted in initial stabilization of lung function, but was followed by gradual resumption of FEV1 decline. The IECF that triggered the patient's 2019 admission to ICU, during which she underwent a tracheostomy, is indicated with a red arrow (for interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

A severe exacerbation in September 2019 necessitated an ICU admission for intubation and mechanical ventilation, but she responded well enough to return to the CF ward with a tracheostomy in situ. She was accepted onto the active lung transplant list in late 2019, with an FEV1 of 0.73 L (26% of the predicted value), and elected to remain in hospital until a donor organ became available.

1.2. Clinical course

The patient experienced a pronounced and rapid deterioration within 2 days of the onset of symptoms; her respiratory rate rose to 48 breaths/min despite maximal bi-level positive airway pressure support via her tracheostomy and supplemental oxygen at 10 L/min. This was accompanied by hypotension, tachycardia and worsening fever.

She was admitted to the ICU for mechanical ventilation; at this point, she met the criteria for diagnosis of severe ARDS, with a PaO2:FiO2 of 96 mmHg (Table 1 ). In addition to a widespread cytopenia, circulating levels of C-reactive protein and lactate were elevated, as were several other critical illness markers known to be increased in severe COVID-19, such as lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, procalcitonin and d-dimer. Following her re-admission to ICU on this occasion, the patient was suspended from the active transplant list.

Table 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics at time of ICU admission.

| Variable | Normal value or range | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 108 | |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/minute) | 48 | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 103/68 | |

| Temperature ( °C/°F) | 39.5/103.1 | |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation (%) | 91 | |

| Arterial blood gas | ||

| PaO2 (kPa) | 7.7 | 11.1–14.4 |

| PaCO2 (kPa) | 6.9 | 4.3–6.0 |

| pH | 7.45 | 7.35–7.45 |

| PaO2:FiO2 (mmHg) | 96 | 400–500 |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 1.2 | 0.5–1.0 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 372 | 0–5 |

| White cell count (109/l) | 5.69 | 4.0–11.0 |

| Neutrophils | 4.59 | 2.0–7.5 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.87 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Monocytes | 0.21 | 0.2–1.0 |

| Eosinophils | 0.02 | 0.04–0.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9.8 | 11.5–16.5 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/l) | 13 | 0–41 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/l) | 36 | 0–40 |

| Albumin (IU/l) | 34 | 35–52 |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 3.2 | 2.8–8.1 |

| Creatinine (µmol/l) | 36 | 45–84 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/l) | 704 | 135–225 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 1646 | 13–150 |

| Fibrinogen (g/l) | 7.8 | 1.9–3.5 |

| Procalcitonin | 0.56 | 0–0.49 |

| D-Dimer | 3.2 | 0–0.5 |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin (g/l) | 2.64 | 0.9–2.0 |

PaO2 – partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

PaCO2 – partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

PaO2:FiO2 – ratio of the partial pressure of arterial oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen.

1.3. Airway inflammation at admission to ICU

Bronchoscopy was undertaken upon ICU arrival to relieve mucus plugging and perform bronchoalveloar lavage (BAL). Central to airway inflammation and lung injury in both cystic fibrosis (CF) and ARDS is neutrophil elastase (NE), an omnivorous serine protease released by activated or disintegrating neutrophils [4]. NE activity levels and cytokines in the BAL fluid obtained were compared to levels from BAL fluid collected at a recent routine bronchoscopy performed at the patient's clinical baseline and BAL fluid obtained during a previous infective exacerbation of CF (IECF, Table 2 ). Airway NE activity was markedly increased in the ICU sample, as were the levels of interleukin (IL)−1β, IL-6 and the potent neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8 (Table 2). Plasma concentrations of these cytokines, along with levels of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNFR1, a surrogate marker for circulating TNF-α) were also increased (Table 2). For both blood and airway samples, the sharpest increases were observed in IL-6 and IL-1β. This was more in keeping with the pattern observed in severe COVID-19 [5] than for a typical IECF.

Table 2.

Inflammatory cytokines and neutrophil elastase activity levels relative to baseline.

| Inflammatory mediators | Baseline | Most recent severe IECF* | COVID-19† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood cytokines (pg/ml) | |||

| IL-1β | 12.1 | 20.7 | 141.4 |

| IL-6 | 63.8 | 97.4 | 571.3 |

| IL-8 | 88.3 | 119.9 | 238.7 |

| sTNFR1 | 2870.9 | 3615.1 | 4092.5 |

| Airway cytokines (pg/ml)‡ | |||

| IL-1β | 202.6 | 299.0 | 374.6 |

| IL-6 | 104.7 | 198.4 | 633.9 |

| IL-8 | 492.2 | 658.3 | 788.1 |

| Airway NE activity (nM)‡ | 741.9 | 905.6 | 1298.8 |

Also required intensive care unit admission.

At time of admission to intensive care unit.

Measured in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

IECF – infective exacerbation of cystic fibrosis

IL – interleukin

sTNFR1 – soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1.

Lung protective ventilation and prone positioning were unsuccessful in slowing her decline, and chest radiography identified worsening bilateral consolidation (Fig. 2 ). Given the patient's grave prognosis and the specific inflammatory phenotype observed, we examined the possibility of using alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) as an off-label therapeutic, based on biological plausibility.

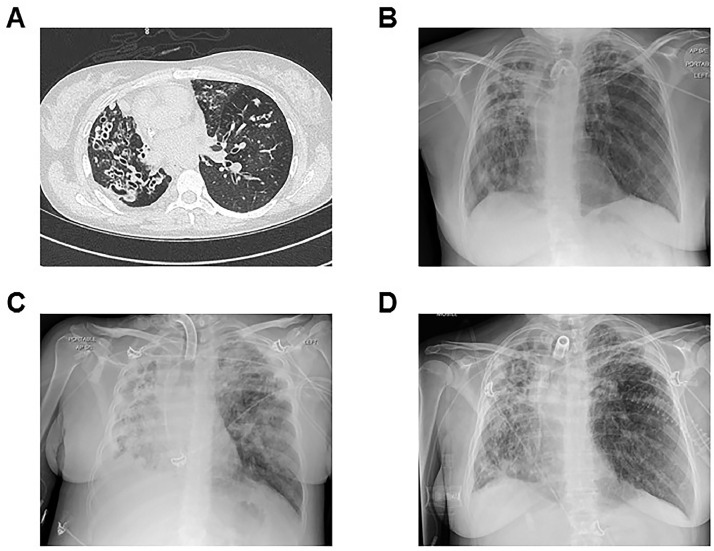

Fig. 2.

Thoracic imaging for the patient over time.

A high-resolution chest CT obtained at the patient's baseline (Panel A) demonstrated extensive and bilateral varicose bronchiectasis, more pronounced within the right lung and associated with mucus plugging and bronchial wall thickening. In Panel B, chest radiography from the day the patient tested positive for COVID-19 showed bilateral infiltrates. Panel C shows the patient's chest radiograph on the morning of commencement of AAT therapy. Volume loss in the right hemithorax was associated with a right-sided pleural effusion. Extensive opacification was observed throughout the right lung. Airspace change in the left lung was most confluent at the left upper zone. The chest radiograph shown in Panel D was taken at the conclusion of therapy (day 28) and demonstrated bilateral radiological improvement.

1.4. Study medication and rationale for use

AAT is a 52 kDa glycoprotein synthesized primarily in the liver, and the archetypal serine protease inhibitor, acting to protect the airway from NE-mediated damage [6], [7], [8]. Of additional relevance to COVID-19, AAT is also a potent immunomodulator, regulating the production and activity of several key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], while preserving the production of IL-10 [14,15]. Plasma-purified AAT (Prolastin) was provided on compassionate grounds by Grifols Pharmaceuticals, Spain. Intravenous (IV) administration was preferred to the aerosol route for two reasons. First, the patient displayed significant systemic inflammation; second, the use of an aerosol-generating device may have introduced a safety hazard by increasing the risk of viral transmission.

1.5. Anti-protease and anti-inflammatory effects observed following administration of IV AAT

A dose of 120 mg/kg was chosen given the half-life of IV AAT, and its successful inhibition of airway NE in AAT-deficient individuals [16]. Regular blood and airway sampling – the latter via the patient's tracheostomy – was undertaken immediately before the first dose (day 0), 2 days post-dose to coincide with peak circulating AAT levels (day 2) [7], and at 7 days post-dose (day 7). For this repeated airway sampling, tracheal aspirates were used, since they are more easily obtained and less invasive than BAL. Samples were handled and processed according to strict protocols, as previously described [17]. A decrease in inflammation was observed at day 2 compared to day 0, with substantial reductions in IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and sTNFR1 in blood and decreased airway levels of NE activity, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 (Fig. 3 A and B). These changes were matched by clinical improvement (Figure S1). However, as AAT approached pre-infusion levels by day 7, both pulmonary and systemic inflammation re-emerged, and the patient deteriorated once more. A second AAT dose was given, following which she again demonstrated discernible clinical and biochemical improvement. Furthermore, the inflammatory rebound following this second infusion was less pronounced. This effect was also seen following the patient's third and fourth doses (Fig. 3), reducing the likelihood that the changes in NE activity and cytokine levels observed following administration of AAT were merely a coincidental occurrence.

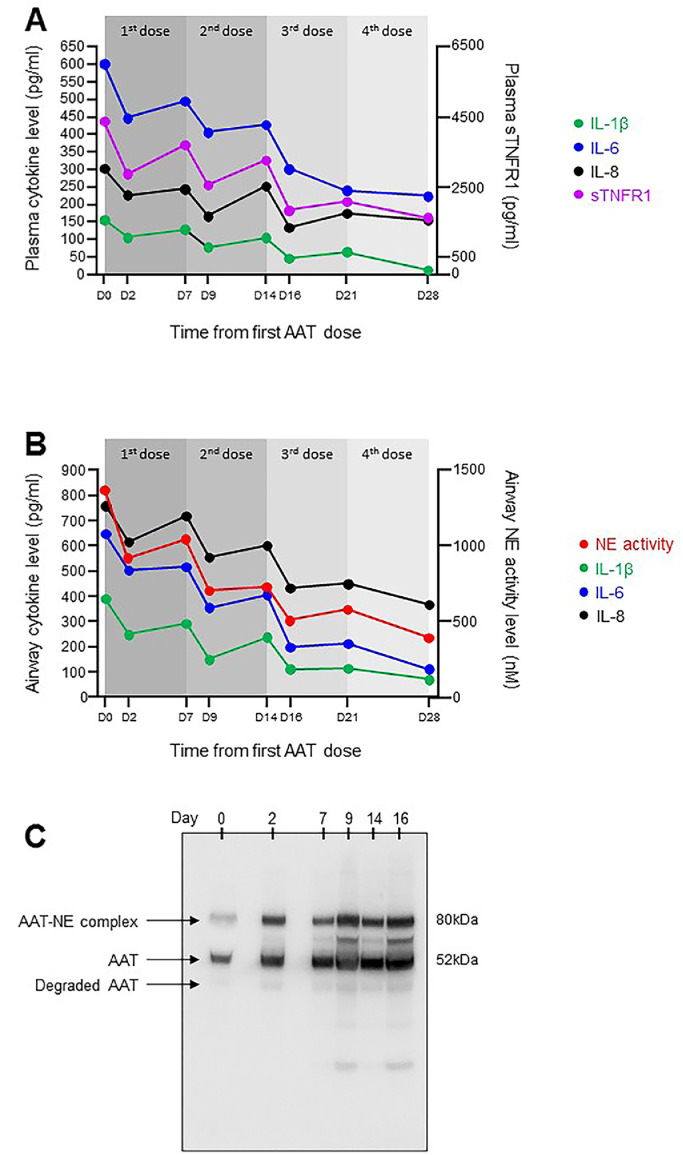

Fig. 3.

Anti-protease and anti-inflammatory effects of AAT in the circulation and the lung.

Serial blood samples and tracheal aspirates were obtained immediately prior to the first infusion (day 0) at day 2 post-infusion to coincide with peak plasma AAT concentration, and at day 7. A) circulating levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 were reduced post-AAT (left Y-axis), with sTNFR1, a surrogate for circulating TNF-α, also decreased (right Y-axis). As circulating AAT returned to pre-infusion levels, a re-emergence of the pro-inflammatory mediators was observed. Repeat doses at day 7, day 14 and day 21 were required to maintain the anti-inflammatory effect. B) As for plasma, airway levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 fell abruptly with each weekly dose, as did NE activity. By day 16, airway NE activity had decreased to levels well below the patient's baseline. C) Western blot analysis of airway samples demonstrated increased AAT-NE complexation at 81 kDa following the initial AAT dose (day 2), and 2 days following each subsequent dose (day 9, day 16). In addition to complexation with NE, AAT also undergoes proteolytic cleavage and oxidative inactivation in the lung. The non-complexed, non-degraded AAT present at 52 kDa had lost its anti-protease activity, as evidenced by the presence of active NE in the same airway samples in Panel B. For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Western blot analysis of serial airway samples (Fig. 3C) demonstrated increased AAT-NE complexes two days after the initial AAT dose, with this pattern replicated following subsequent doses, (day 9, day 16), confirming that the decrease in NE activity was due to direct inhibition by AAT in the form of a direct binding event.

1.6. Clinical status at one month

IV AAT was well tolerated throughout, with no adverse events attributable to the drug encountered. At one month, following radiographic improvement (Fig. 2D) and return to her airway inflammatory baseline, the patient was successfully liberated from sedation and mechanical ventilation. While she had experienced physical deconditioning with loss of muscle mass, she did not demonstrate clinical evidence of critical care myopathy, and was ambulatory within days. Her tracheostomy remained in situ, both to facilitate suctioning of airway secretions, and in anticipation of a lung transplant following her return to the active list.

2. Discussion

Here we report the first successful administration of IV AAT for severe cytokinemic COVID-19 complicated by ARDS. While the magnitude and nature of the inflammatory response observed differentiated it from a typical IECF, the present case cannot be ascribed solely to COVID-19. Instead, it likely represents the coalescence of two heavily pro-inflammatory conditions. The blended immunophenotype and rapid clinical decline that ensued were unresponsive to conventional ARDS management, prompting the off-label use of plasma-purified AAT as a salvage therapeutic. In addition to a systemic anti-inflammatory effect, airway cytokine concentrations and NE activity decreased in following treatment, and were matched by clinical improvement.

This study is limited in that it involved treatment of one patient only. However, this allowed us to investigate in greater detail than would have otherwise been possible. We were fortunate in that regular airway sampling throughout the treatment period was made possible by the presence of a pre-existing tracheostomy, thereby facilitating the demonstration of a biological response to AAT in the airway. Had we been confined to BAL at less frequent intervals, we would have failed to capture the effects identified here. While it was clinically indicated in this case, conserved tracheostomy tubes may also introduce an element of risk in CF if they are not accompanied by regular physiotherapy, cough training and suctioning protocols, since they can impair the natural cough mechanism.

Although airway NE activity is increased in patients with ARDS, the levels encountered here are more consistent with severe CF lung disease and chronic infection. Similarly, while the blood and airway cytokinemia observed was more in keeping with severe COVID-19, several CF-related factors are likely to have contributed to the patient's cytokine profile. For example, both macrophages and neutrophils undergo metabolic reprogramming in advanced CF, with increased aerobic glycolysis and inflammasome activation promoting increased production and processing of IL-1β [18,19]. NE induces further release of IL-1 and IL-8 from respiratory epithelial cells [20], with IL-1 in turn upregulating IL-6 in viral illness [21]. This begs the question of whether the novel therapeutic approach taken here is applicable to non-CF patients with severe COVID-19. The answer may be provided by a randomized, multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of IV AAT for ARDS secondary to COVID-19 currently underway (EudraCT 2020–001391–15).

The implications of this study for PWCF go beyond COVID-19. In discussions regarding the allocation of resources and ICU support during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with significant CF lung disease are at risk of being overlooked. Current CF Foundation guidelines state that PWCF with advanced disease should be considered for ICU [22]. However, as concerns regarding ventilator shortages mount, PWCF risk being included in the same triage categories as older and less functional patients suffering from more common chronic pulmonary diseases [23]. Similarly, practice guidelines that are not based on more recent prognostic data [24] may discriminate unfairly against PWCF. The findings may also prompt re-exploration of AAT as an anti-protease and anti-inflammatory CF therapeutic. Prior attempts to reduce airway inflammation using inhaled AAT strategies have provided mixed results [25], [26], [27], with the heterogeneity of the CF lung, and differences in mucus rheology between PWCF potentially contributing to the variability observed between studies. These potential confounders may not have applied to the same extent in this instance due to the IV route of administration used.

Moreover, previous studies focused primarily on AAT as a maintenance treatment, rather than an IECF therapeutic. The anti-inflammatory effects of AAT, coupled with its protection against C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) cleavage – a protease-driven event that results in impaired phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [28] – would seem to support further investigation of the latter.

As our understanding of the clinical and inflammatory characteristics of severe COVID-19 evolve, so too does our knowledge of the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 infection in CF. Although these data do not necessarily apply to all COVID-positive PWCF, they do identify a potential therapeutic for those who are in extremis. Perhaps most importantly, the outcomes described emphasize the importance of translational research in driving patient-tailored care. In this instance, a personalized approach was facilitated by an understanding of the molecular basis of inflammation and the pathogenesis of multiple conditions in a critically unwell patient. At a time of unprecedented demand on health services, precision medicine remains possible.

Credit author statement

Author contributions: O.J.McE., G.F.C. and N.G.McE. conceptualized the study; O.J.McE., E.O'C., N.L.McE., D.F. J.C. O.F.McE., C.G., J.O'R., G.F.C. and N.G.McE. collected clinical data, attended to the patient and administered treatment; O.J.McE., E.O'C., N.L.McE., D.F., O.F.McE., C.G. and J.O'R. collected and processed samples; O.J.McE., N.L.McE. and O.F.McE. designed and performed experiments. O.J.McE., E.O'C. and N.G.McE. co-wrote the manuscript; All authors edited the manuscript.

Sources of support

O.J.McE. received support from the Elaine Galwey Memorial Research Bursary and the American Thoracic Society in the form of an ATS International Trainee Scholarship award and an ATS abstract scholarship award.

Declaration of Competing Interest

N.G.McE. has previously been an investigator in trials for CSL Behring, Galapagos and Vertex. He has sat on advisory boards for CSL Behring, Grifols, Chiesi and Shire. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.11.012.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosgriff R., Ahern S., Bell S.C., Brownlee K., Burgel P.R., Byrnes C., et al. A multinational report to characterise SARS-CoV-2 infection in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19(3):355–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molloy K., Cagney G., Dillon E.T., Wynne K., Greene C.M., McElvaney N.G. Impaired airway epithelial barrier integrity in response to stenotrophomonas maltophilia proteases, novel insights using cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cell secretomics. Front Immunol. 2020;11:198. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantin A.M., Hartl D., Konstan M.W., Chmiel J.F. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease: pathogenesis and therapy. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14(4):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McElvaney O.J., McEvoy N., McElvaney O.F., Carroll T.P., Murphy M.P., Dunlea D.M., et al. Characterization of the Inflammatory Response to Severe COVID-19 Illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1583OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doring G. The role of neutrophil elastase in chronic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(6 Pt 2):S114–S117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/150.6_Pt_2.S114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wewers M.D., Casolaro M.A., Sellers S.E., Swayze S.C., McPhaul K.M., Wittes J.T., et al. Replacement therapy for alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency associated with emphysema. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(17):1055–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadek J.E., Klein H.G., Holland P.V., Crystal R.G. Replacement therapy of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Reversal of protease-antiprotease imbalance within the alveolar structures of PiZ subjects. J Clin Invest. 1981;68(5):1158–1165. doi: 10.1172/JCI110360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonigk D., Al-Omari M., Maegel L., Muller M., Izykowski N., Hong J., et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of alpha1-antitrypsin without inhibition of elastase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(37):15007–15012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309648110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy C., Dunlea D.M., Saldova R., Henry M., Meleady P., McElvaney O.J., et al. Glycosylation repurposes alpha-1 antitrypsin for resolution of community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(10):1346–1349. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201709-1954LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pott G.B., Chan E.D., Dinarello C.A., Shapiro L. Alpha-1-antitrypsin is an endogenous inhibitor of proinflammatory cytokine production in whole blood. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(5):886–895. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stockley R.A. Role of inflammation in respiratory tract infections. Am J Med. 1995;99(6B) doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80304-0. 8S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strnad P., McElvaney N.G., Lomas D.A. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1443–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1910234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElvaney O.J., Carroll T.P., Franciosi A.N., Sweeney J., Hobbs B.D., Kowlessar V., et al. Consequences of abrupt cessation of alpha1-antitrypsin replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1478–1480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1915484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janciauskiene S.M., Nita I.M., Stevens T. Alpha1-antitrypsin, old dog, new tricks. Alpha1-antitrypsin exerts in vitro anti-inflammatory activity in human monocytes by elevating cAMP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(12):8573–8582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campos M.A., Geraghty P., Holt G., Mendes E., Newby P.R., Ma S., et al. The biological effects of double-dose alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy. a pilot clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(3):318–326. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201901-0010OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McElvaney O.J., Gunaratnam C., Reeves E.P., McElvaney N.G. A specialized method of sputum collection and processing for therapeutic interventions in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McElvaney O.J., Zaslona Z., Becker-Flegler K., Palsson-McDermott E.M., Boland F., Gunaratnam C., et al. Specific inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome as an anti-inflammatory strategy in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-1013OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forrest O.A., Ingersoll S.A., Preininger M.K., Laval J., Limoli D.H., Brown M.R., et al. Frontline science: pathological conditioning of human neutrophils recruited to the airway milieu in cystic fibrosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104(4):665–675. doi: 10.1002/JLB.5HI1117-454RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll T.P., Greene C.M., Taggart C.C., Bowie A.G., O'Neill S.J., McElvaney N.G. Viral inhibition of IL-1- and neutrophil elastase-induced inflammatory responses in bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7594–7601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose-John S., Winthrop K., Calabrese L. The role of IL-6 in host defence against infections: immunobiology and clinical implications. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(7):399–409. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapnadak S.G., Dimango E., Hadjiliadis D., Hempstead S.E., Tallarico E., Pilewski J.M., et al. Cystic fibrosis foundation consensus guidelines for the care of individuals with advanced cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19(3):344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos K.J., Pilewski J.M., Faro A., Marshall B.C. Improved prognosis in cystic fibrosis: consideration for intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1434–1435. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-0999LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos K.J., Quon B.S., Heltshe S.L., Mayer-Hamblett N., Lease E.D., Aitken M.L., et al. Heterogeneity in survival in adult patients with cystic fibrosis with FEV1 < 30% of predicted in the United States. Chest. 2017;151(6):1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griese M., Latzin P., Kappler M., Weckerle K., Heinzlmaier T., Bernhardt T., et al. Alpha1-antitrypsin inhalation reduces airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis patients. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(2):240–250. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00047306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McElvaney N.G., Hubbard R.C., Birrer P., Chernick M.S., Caplan D.B., Frank M.M., et al. Aerosol alpha 1-antitrypsin treatment for cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1991;337(8738):392–394. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91167-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaggar A., Chen J., Chmiel J.F., Dorkin H.L., Flume P.A., Griffin R., et al. Inhaled alpha1-proteinase inhibitor therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15(2):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartl D., Latzin P., Hordijk P., Marcos V., Rudolph C., Woischnik M., et al. Cleavage of CXCR1 on neutrophils disables bacterial killing in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Nat Med. 2007;13(12):1423–1430. doi: 10.1038/nm1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.