Abstract

The COVID-19 reported initially in December 2019 led to thousands and millions of people infections, deaths at a rapid scale, and a global scale. Metropolitans suffered serious pandemic problems as the built environments of metropolitans contain a large number of people in a relatively small area and allow frequent contacts to let virus spread through people's contacting with each other. The spread inside a metropolitan is heterogeneous, and we propose that the spatial variation of built environments has a measurable association with the spread of COVID-19. This paper is the pioneering work to investigate the missing link between the built environment and the spread of the COVID-19. In particular, we intend to examine two research questions: (1) What are the association of the built environment with the risk of being infected by the COVID-19? (2) What are the association of the built environment with the duration of suffering from COVID-19? Using the Hong Kong census data, confirmed cases of COVID-19 between January to August 2020 and large size of built environment sample data from the Hong Kong government, our analysis are carried out. The data is divided into two phases before (Phase 1) and during the social distancing measure was relaxed (Phase 2). Through survival analysis, ordinary least squares analysis, and count data analysis, we find that (1) In Phase 1, clinics and restaurants are more likely to influence the prevalence of COVID-19. In Phase 2, public transportation (i.e. MTR), public market, and the clinics influence the prevalence of COVID-19. (2) In Phase 1, the areas of tertiary planning units (i.e., TPU) with more restaurants are found to be positively associated with the period of the prevalence of COVID-19. In Phase 2, restaurants and public markets induce long time occurrence of the COVID-19. (3) In Phase 1, restaurant and public markets are the two built environments that influence the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases. In Phase 2, the number of restaurants is positively related to the number of COVID-19 reported cases. It is suggested that governments should not be too optimistic to relax the necessary measures. In other words, the social distancing measure should remain in force until the signals of the COVID-19 dies out.

Keywords: COVID-19, Built environment, Social distancing measures, Census data

1. Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic, also known as COVID-19, appeared in December 2019 soon spread all over the world [1]. The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 is of very-high-concern to the public, and it affects different industries and economies. According to the recent report from the World Health Organization [2], there are over 20 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, of which 13 million recovered and 0.7 million fatalities are reported in more than 188 countries and territories up to July 15, 2020. The transmission of COVID-19 virus through large droplet transmission, aerosol transmission, and indirect fomite. This virus infection rate is much higher than the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Disease (SARS-CoV) in 2003. And the human-to-human and zoonotic (between human and animals) transmission have been drastically boosting the potential reach of the virus outbreak, especially in the metropolitans with a large population and concrete jungles.

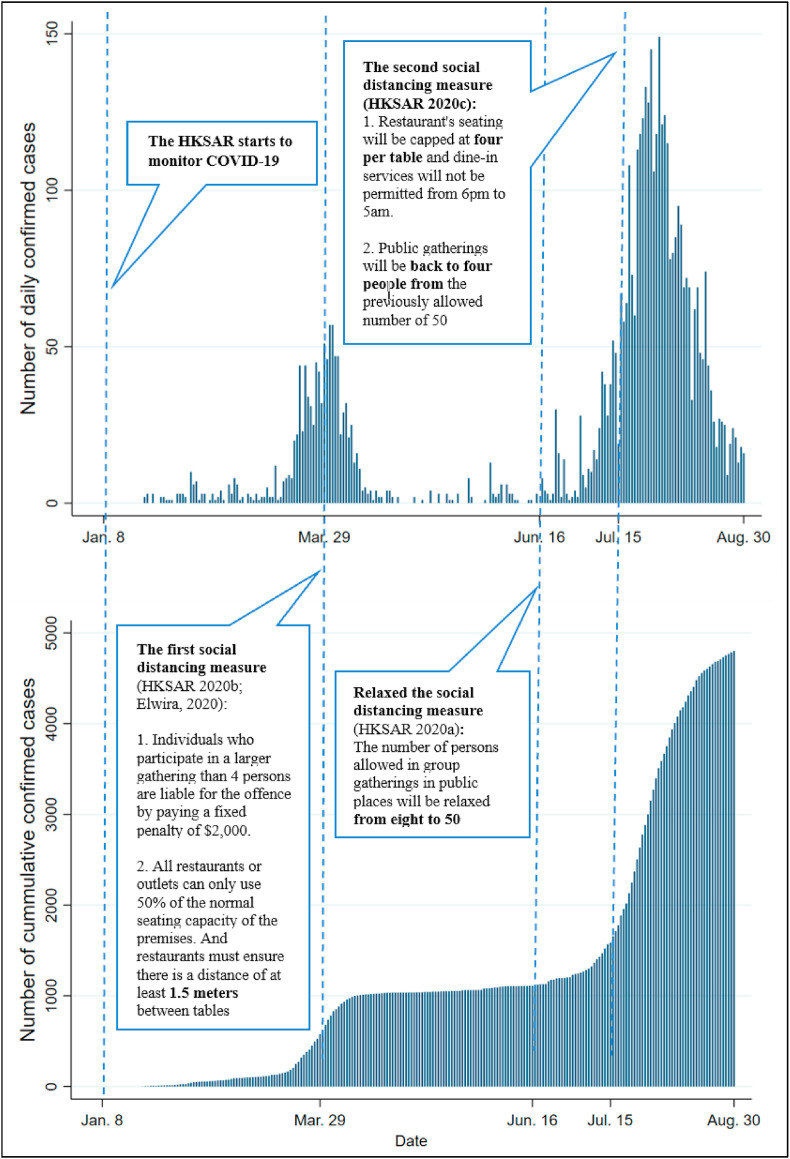

To date, no effective vaccine or special treatment is available for infected individuals. Therefore, the governments of different countries have to rely on non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI), including city lockdown, travel restriction, contact tracing, self-quarantine, and social distancing, to suppress the coronavirus spread. The metropolitans with a high-density population face great threats from the virus and call for more stringent NPI. Yet the effectiveness of the NPI is varied among different countries or territories. In Asia, Korea and Vietnam responded aggressively from the beginning of the pandemic, and now slowly move back to normal without observing new outbreaks. The city of Hong Kong is a typical metropolitan in the world and contains 7.5 million residents living in a small geographic area of 1100 km2. Hong Kong government took early and prompt intervention at the outset of the pandemic and it was nearly unscathed at the early stage. However, it declared to be back to normal in June, leading to a new wave of the outbreak of COVID-19 [3] and over 4800 confirmed cases accumulated at the end of August 2020 (Fig. 1 ). Hong Kong was one of few metropolitans that were not locked down during the observed period and in which Hong Kongers were free to commute, although they may change travel behaviours and frequencies.

Fig. 1.

Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong from January to August 2020.

The outbreak of COVID-19 piqued the researchers’ interest. The studies in the early stages reported that the transmission rate of COVID-19 was influenced by demographic and social attributes such as age and gender difference [[4], [5]]. Risk reduction relied on intensive NPI [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. Through inspired by the early studies, some recent studies [[10], [11], [12], [13]] attempted to investigate the effectiveness of the NPI via mathematical analysis or simulation studies. Zhang et al. [13] proposed an agent-based SEIIR model to study the impacts of various NPI on suppressing the infection of COVID-19 in Shenzhen, China. They found that quarantining recent individuals visit Hubei Province, shortening the time period from symptom onset to hospital admission, and let symptomatic individuals self-quarantined at home are the three most important NPIs to suppress the risk of infection in Shenzhen. Cadoni and Gaeta [10] simulated the impact of maintaining social distance on controlling the epidemic diffusion. They argued that early detection and prompt self-quarantine would be more effective (than keeping social distance) to reduce coronavirus transmission. Dolbeault and Turinici [11] studied how city lockdown would affect the infection rate in France in a qualitative manner. They found that even a large number of the population abided by the lockdown arrangement, while a small fraction of the people who are health workers still have to maintain some certain level of social interactions, is not enough to control the outbreak. Pang [12] measured the lockdown policy on the spread of COVID-19 by incorporating the asymptomatic transmissions into the mathematical model. The findings are that the lockdown policy shows limited effects on the asymptomatic viral carriers.

Nonetheless, the existing COVID-19 studies assume that the execution of the NPI may generate similar effects for different areas in the city. Some recent reports outline that the spread rate of COVID-19 is varied across different areas [14]. The impact of the different communities (characterized by built environments) on the spread of COVID-19 are overlooked, which may not provide a holistic view of how to implement the NPI to suppress the virus effectively for the city governors. In a broad sense, the built environment includes our homes, schools, workplaces, recreation areas, business areas, and roads [15]. Considering that the outbreak of the COVID-19 is most likely related to our living environment, therefore the built environment in this paper includes locations where people may have social interactions such as restaurants, private and public housing areas, public markets, subway stations, and clinics.

To our best knowledge, people spend most of their time inside the built environment, COVID-19 can be transmitted through air, direct and indirect contact when individuals move inside the built environment [16]. In the literature of building and environment, a growing number of studies have unveiled the mysterious transmission mechanism of COVID-19 inside the built environment. Cheng et al. [17] formulated the motion and the large respiratory droplets trajectories by employing a simplified single-droplet approach. They suggested that maintaining a safe social distance of about 2 m is necessary. Mao et al. [18] performed a comprehensive review of the transmission mechanism and risks of viral infections by infectious droplets at different time. They show that large droplets are of high transmission risk than that of small droplets. Zhou and Ji [19] took a typical fever clinic as the study objected to consider the issues of cross-infection in terms of the transport of droplets generated by patients and doctors. They concluded that the risk of infection is negatively associated with the distance from occupants. Despite the above studies disclose the relationship between the droplets and virus transmission of COVID-19, yet their settings are either considered as the general case [[17], [18]] or limited in the clinic (or hospital) environment [20]. One exceptional example is research conducted by Blocken et al. [21]. They intended to investigate the challenges of re-opening the in-door sports facilities. They advocated that cardio training; workout training with weights; non-contact group exercises in classes could partially be restarted outside provided that the outdoor space is available and the weather allows. Among the most recent publications in the existing literature of building and environment, the problem of which specific types of the built environment are of a high risk of infecting COVID-19 is understudied. To identify in what specific built environments we bear a high risk of being infected by COVID-19 should be our priority concern before deep diving into discussing the transmission mechanism of COVID-19.

We are therefore motivated by the proposition that the spread of COVID-19 is related to the aspects of the built environments. In this study, we would like to explore two research questions: (1) What are the association of the built environment with the risk of being infected by the COVID-19? (2) What are the association of the built environment with the duration of suffering from COVID-19? To address these 2 questions, we will use a massive data set from the Hong Kong government (i.e. the census statistics, confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Hong Kong as well as built environment data in Hong Kong), and employ three different empirical models to analyze two dependent variables (the cumulative number of infected cases and the duration to the first confirmed cases) across tertiary planning unites (TPU) over two phases. The investigation of these two research questions is timely, and this paper documents the spatial variations of the metropolitan built environment and the COVID-19 spread, which have not been jointly studied yet. The findings would help the city governors and authorities to make some necessary NPI allocate sufficient resources for the different built environments to control the virus spread.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows. After a brief introduction, we discuss the study area, data, and variables in Section 2. Section 3 portrays the research method. Section 4 summarizes the results and findings. Section 5 addresses the conclusion.

2. Study area, data and variable

2.1. Study area

The city of Hong Kong lies in the southern part of China. The total land area is 1106 km2, of which about 24% (i.e. 268 km2) and 4% (i.e. 43 km2) are existing built-up areas and areas under planning studies, respectively [22]. The remaining land area (i.e. 72% of the total land) is left for green areas, ecologically sensitive areas, and hilly terrain [22]. With reference to the recent demographical report from the Hong Kong government, the population is around 7,524,100 (CSD, 2019). In other words, the average population density of Hong Kong is about 6802 persons per km2 on a territorial scale. If only the built-up areas are considered, the average population density is as high as 28,075 persons per km2. To make good use of limited land resources, Hong Kong follows the pattern of high-rise and high-density development. It functions well in Hong Kong compared to other well-developed cities in the U.S. and Europe. However, the high-rise and high-density development in Hong Kong has inevitably generated some potential problems for anti-COVID-19, as the densely living environment may boost the potential reach and such that the built environment that allows people have social interactions may be of the high risk of being infected by COVID-19.

2.2. Data

Three sets of data have been sourced and collected in this study. The first set is the semi-decennial census statistics of 2016, which is obtained from the Hong Kong Census and Statistical Department. This data set documents the demographical information in the tertiary planning units (TPU) level. The TPU is a geographic reference system demarcated by the Hong Kong Planning Department (HKPD) for the Territory of Hong Kong, which is similar to the tract-level census in the U.S. According to the HKPD, the city of Hong Kong is divided into 291 TPUs, incorporating the TPU boundaries and demographic information. For those TPUs that are less than 1000 people, the census statistics would be merged in the adjacent TPUs for the sake of protecting the privacy of individual household and personal records [23]. As such, there are in total 154 TPUs, including the merged TPUs and single TPU are reported in 2016 census statistics. Apart from the 2016 census statistics (the most up-to-date official records of the census statistics in Hong Kong), the usage of this static record in the following study is legit as there are no significant changes in the demographic factors since the outbreak of COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

The second set of data utilized in this study comes from the Department of Health in Hong Kong. This set of data details the information of COVID-19 confirmed cases, where the COVID-19 confirmed cases were reported based on the testing results from the Hong Kong government recognized hospitals [24]. It also contains the information of the location/building where the confirmed cases resided, and the date at which the confirmed cases was reported. The time span of this set of data is between January 8, 2020, and August 30, 2020. As of August 30, 2020, a total of 4802 COVID-19 confirmed cases are reported in which some are the imported cases who are non-HK residents and do not have permanent local addresses. In this regard, only residents who have permanent/living addresses would be used for the following analysis and they are 3884 confirmed cases in total.

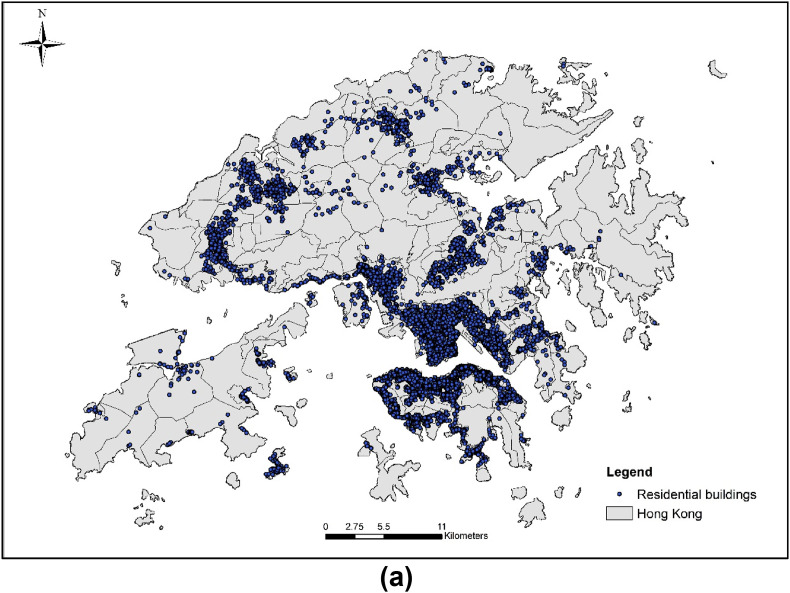

The third set of data employed in this study records the information of the built environment, which consists of information about residential buildings, transportation, clinic, public markets. The location information as regards the built environment is static. In specific, 17,540 records of residential buildings, including private housing and public housing, are obtained from the website of the Home Affairs Department in Hong Kong, 15,458 records of restaurants and 67 records of public markets are collected from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department in Hong Kong, 2421 records of private clinics are from the website of Electronic Health Record Sharing System in Hong Kong. The information of 426 subway entrances is from the website of the Mass Transit Rail Company (i.e., MTR).

2.3. Variables

By geocoding the addresses of the COVID-19 confirmed cases and the built environment data, we link up the demographic information, residential building information, and built environmental information to the TPU.

As indicated by recent studies [[4], [5], [25]], the distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases is influenced by demographic and social factors (i.e., age and population density), therefore the population of TPU (Population), the median level of domestic household size in TPU (HSize), the number of labor work in TPU where they do not live in (WorkDT), the percentage of people aged 65 or above is over 20% in TPU (Age65_O20), and the percentage of population 65 or above is between 14% and 20% (Age65_14) are selected as the control variables.

In this study, we pay special interest to the built environment variables, including the number of people living in public housing (Pub_Housing), whether the public housing dominated in the TPU (i.e. over 50%, PublicDom), coverage of public housing in the TPU (Pert_Pub), number of private clinics (N_Clinic), the number of restaurants in the TPU (N_Restaurant), the number of public markets in the TPU (N_PublicMarket), number of entrances of the mass transit railway (i.e. MTR) (N_MTRE), the median value of the closest distance to the built environmental attributes (D_Clinic, D_Restaurant, D_PublicMarket, and D_MTRE). The closest distance refers to the distance from the residential building to the nearest built environmental attributes, which is the straight line between the residential building and the nearest built environmental attributes. The closest distance is produced by ArcGIS 10.2.

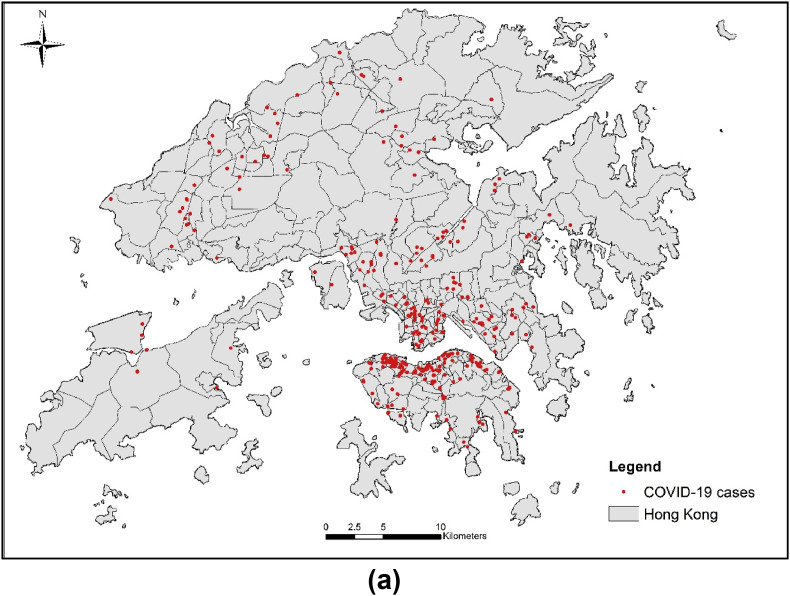

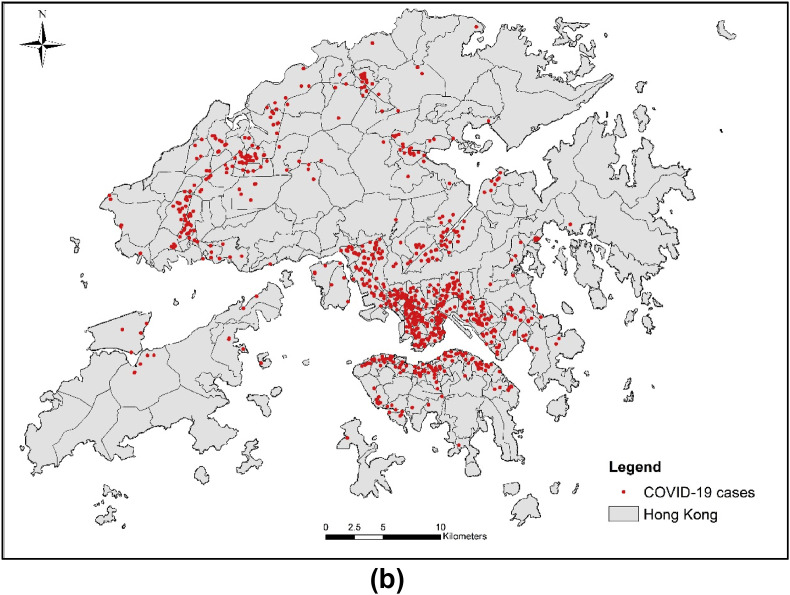

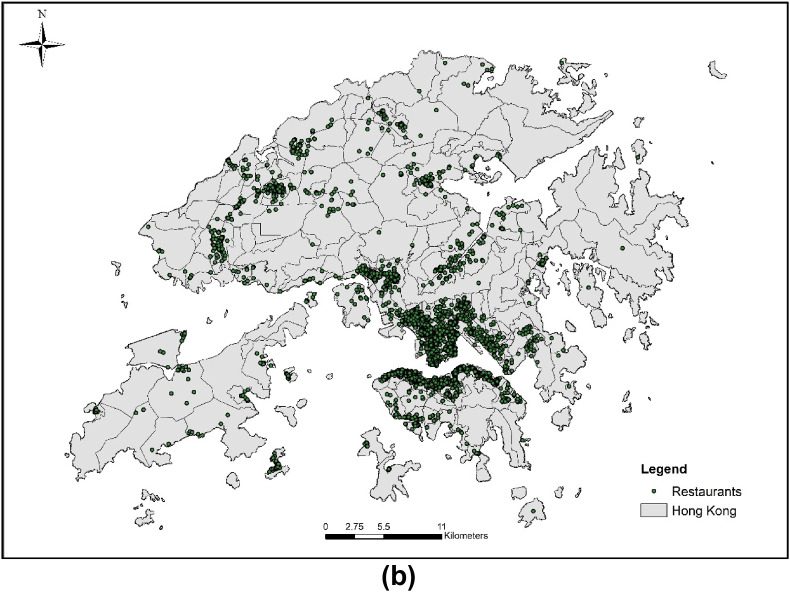

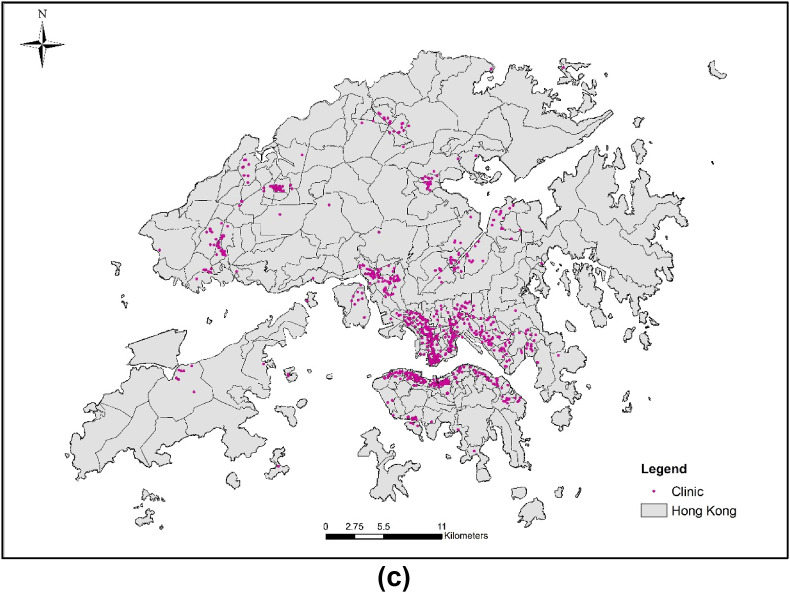

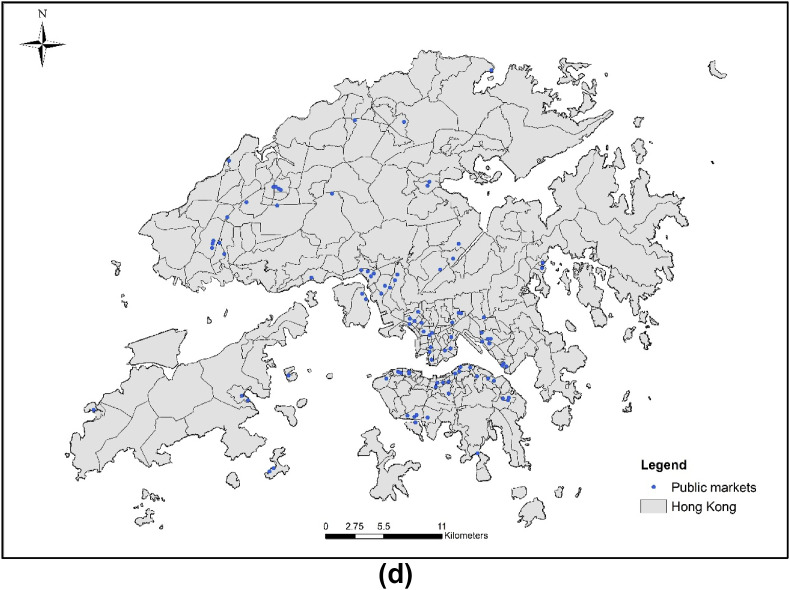

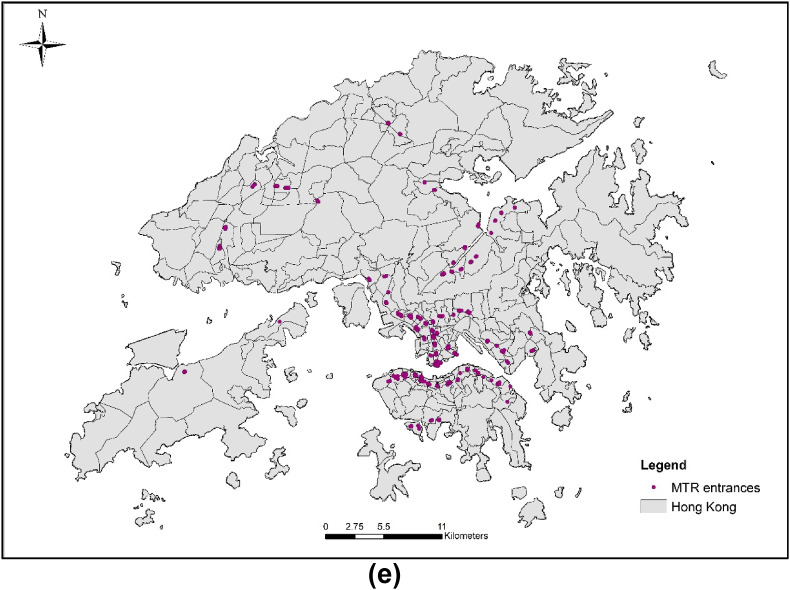

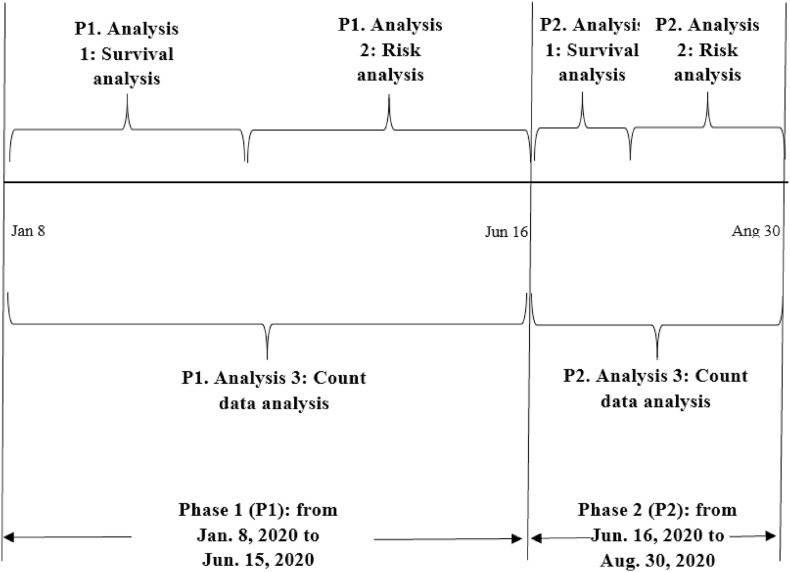

Apart from the control variables and interested variables, the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases are used as the dependent variables in this study. These data sets are divided into two phases over time, which are Phase 1 and Phase 2. The period of Phase 1 covers the period from January 8 to June 15 (including June 15), while time span of Phase 2 is between June 16 and August 30. The cut-off point is set as June 16 that is the date when the Hong Kong Government executed the policy of relaxing the social distancing measure that allows up to 50 people gathering and social interaction [26]. Accordingly, the dependent variables selected in these two phases correspond to two different phases (before and after relaxing the social distancing measure). Based on the reported COVID-19 data, we have done some simple calculations to generate key dependent variables. It is the period between the starting day the Hong Kong government monitored the COVID-19 and the official reported date of the first COVID-19 confirmed case in each TPU. The first set of dependent variables (DurFCJJ and DurFCJA, Table 1 ) documents the duration until the TPU becomes infectious from the normal status. The consideration of these two variables (DurFCJJ and DurFCJA, in Table 1) enables us to address the first research question. Also, the duration between the first and the last reported COVID-19 cases in Phase 1 (DurFP, Table 1, Table 2 (DurSP, Table 1) are considered as the alternative sets of dependent variables. Last but not least, the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases reported in Phase 1 (CasesFP, Table 1) and Phase 2 (CasesSP, Table 1) would be pondered as the third set of dependent variables in this study. The consideration of DurFP, DurSP, CasesFP, and CasesSP allows us to examine the second research question. The descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 1. The distribution of COVID-19 cases in Phase 1 and Phase 2 are shown in Fig. 2 a and Fig. 2b. The distribution of residential buildings, restaurants, clinics, public markets, and the MTR entrances are shown in Fig. 3 a–e respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of variables and descriptive statistics.

| Variables |

Description |

Unit |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||||

| DurFCJJ | The period between the starting day the government documented the COVID-19 related case(s) and the first COVID-19 confirmed case from Jan 8 to Jun 15. | Days | 79.18 | 42.85 | |

| DurFP | Duration of suffering COVID-19 in the first phase. It refers to the period between the first confirmed case and the last confirmed case from Jan 8 to Jun 15. | Days | 2.13 | 1.69 | |

| CasesFP | The number of confirmed cases in the first phase from Jan 8 to Jun 15. | Count | 5.89 | 10.04 | |

| ΔCasesFP | Difference between the confirmed cases before and after the first social distancing measure issued on Mar 29. | Count | 4.79 | 9.13 | |

| DurFCJA | The period between the first day the government documented the COVID-19 related case(s) and the first COVID-19 confirmed case from Jun 16 to Aug 30. | Days | 34.09 | 14.26 | |

| DurSP | Duration of suffering COVID-19 in the second phase. It refers to the period between the first confirmed case and the last confirmed case from Jun 16 to Aug 30. | Days | 2.86 | 1.34 | |

| CasesSP | The number of confirmed cases in the second phase from Jun 16 to Aug 30. | Count | 19.41 | 28.59 | |

| ΔCasesSP | Difference between the confirmed cases before and after the second social distancing measure issued on Jul 15. | Count | 16.31 | 19.89 | |

| Independent Variables | |||||

| Age65_O20 (C) | The percentage of the population aged over 65 is over 20% in the TPU | Dummy (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.29 | 0.46 | |

| Age65_14 (C) | The percentage of the population aged over 65 is between 14% and 20% in the TPU | Dummy (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.53 | 0.50 | |

| §Age65_U14 (Ref) | The percentage of the people aged over 65 is between 7% and 14% in the TPU | Dummy (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.16 | 0.37 | |

| Population (C) | Population in the TPU | Number | 47632.36 | 42676.80 | |

| HSize (C) | The median level of domestic household size in the TPU | Number | 2.87 | 0.33 | |

| WorkDT (C) | Number of labor work in the TPU that is different to where they live | Number | 14307.56 | 13957.63 | |

| Pub_Housing | Number of people living in public housing in the TPU | Percentage | 13841.25 | 24015.86 | |

| PublicDom | Whether Pub_Housing is greater than 50% | Dummy (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.15 | 0.36 | |

| Pert_Pub | Coverage of public housing in the TPU | Dummy (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.20 | 0.26 | |

| N_Clinic | Number of clinics in the TPU | Number | 15.85 | 41.66 | |

| N_Restaurant | Number of restaurants in the TPU | Number | 95.85 | 143.11 | |

| N_PublicMarket | Number of public markets in the TPU | Number | 0.64 | 0.98 | |

| N_MTRE | Number of entrances of Massive Transit Rail in the TPU | Number | 2.78 | 4.31 | |

| D_Clinic | Median value of the shortest distance between the clinics and the residential buildings in the TPU | meters | 393.59 | 604.61 | |

| D_Restaurant | Median value of the shortest distance between the restaurants and the residential buildings in the TPU | Meters | 155.92 | 220.73 | |

| D_PublicMarket | Median value of the shortest distance between the public market(s) and the residential buildings in the TPU | meters | 1030.94 | 1114.27 | |

| D_MTRE | Median value of the shortest distance between the entrance of MTR and the residential buildings in the TPU | meters | 1204.01 | 1741.95 | |

Note: 1. §Age65_U14 (Ref) is treated as reference group to avoid dummy trap.

2. (C) is short for control variable.

3. The total number of the TPUs (Tertiary Planning Units) used for the analysis is 154.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics of Cox regression of Phase 1.

| Variable |

Model 1 (Dependent Variable: DurFCJJ) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | z-stat | p-value | |

| Age65_O20 | 1.0394 | 0.14 | 0.891 |

| Age65_14 | 1.3761 | 1.35 | 0.176 |

| Population | 1.0001*** | 4.08 | 0.000 |

| HSize | 2.2878** | 2.60 | 0.009 |

| WorkDT | 0.9998*** | −3.71 | 0.000 |

| Pub_Housing | 0.9999 | −0.36 | 0.722 |

| PublicDom | 0.5572 | −1.22 | 0.224 |

| Pert_Pub | 1.1512 | 0.19 | 0.850 |

| N_Clinic | 1.0057* | 2.21 | 0.027 |

| N_Restaurant | 1.0009 | 1.06 | 0.287 |

| N_PublicMarket | 1.0989 | 1.04 | 0.298 |

| N_MTRE | 0.9971 | −0.11 | 0.913 |

| D_Clinic | 0.9998 | −0.51 | 0.613 |

| D_Restaurant | 1.0007* | 2.24 | 0.025 |

| D_PublicMarket | 1.0002 | 1.56 | 0.119 |

| D_MTRE | 0.9999 | −0.84 | 0.402 |

| log-likelihood | −533.7288 | ||

| No. of TPU | 154 | ||

| No. of failures | 126 | ||

| N | 154 | ||

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Phase 1 denotes the period from January 8 to June 15, 2020.

Fig. 2.

(a) Distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases (phase 1: from January 23 to June 15). (b) Distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases (phase 2: from June 16 to August 30).

Fig. 3.

(a) Distribution of residential buildings in Hong Kong. (b) Distribution of restaurants in Hong Kong. (c) Distribution of clinics in Hong Kong. (d) Distribution of public markets in Hong Kong. (e) Distribution of MTR (Mass Transit Railway) entrances in Hong Kong.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Design for analysis

As the time span of the collected data covers 8 months (i.e. from January 2020 to August 2020), during which the Hong Kong government issued three important policies related to COVID-19. They are social distancing measures (from March 28 to June 15), relaxed social distancing measures (from June 16 to July 14), and tightened social distancing measures (from July 15 onwards). It is not appropriate to perform the data analysis without considering the circumstance in which social distancing measures are tightened or relaxed. In this regard, the exploration of the research questions will be carried out by dividing the study period into two phases (Fig. 4 ). The cut-off point is set as June 16 as the date when the social distancing measure was relaxed and other NPIs were adjusted. In each phase, we will first conduct the survival analysis, where the results provide the answer to the first research question. Afterward, the risk analysis and the count data analysis will be performed to seek out the answer to the second research question. Detailed information about the model and method for these three analyses will be disclosed in the following two sections.

Fig. 4.

Design for analysis.

3.2. Survival analysis for the association between the built environment and COVID-19

To examine the first research question of what the association of the built environment is with the risk of being infected by the COVID-19, the Cox proportional hazards regression (hereafter Cox model) is adopted. The advantage of the Cox model is its flexibility to adjust the association of the potential confounder [20]. To be specific, the built environment such as exposure to restaurants, clinics, public markets, and transportation service locations are considered as risk factors. The consideration of the Cox model is to link these risk factors to the survival time, where the survival time in the TPU refers to the period that between the starting day to monitor the situation of COVID-19 (i.e. January 8, 2020) and the day when the first case reported by the Hong Kong government. Mathematically, the equation is shown as Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where t denotes the time to the first confirmed cases reported, λ0(t) is the baseline hazard function, E[λ(t; X i)] is the expected hazards function at time t, X i = {Control i, Built i} is the covariate for the i-th TPU, Control i, and Built i are the two vectors that document the control variables and built environment-related variables in the i-th TPU, β j (j = 0, 1, 2) are the coefficients that need to be estimated.

3.3. The association of the built environment and the duration of suffering the COVID-19

To explore the association analysis regarding the built environment and the duration of suffering the risk of COVID-19, the empirical analysis will be conducted in two sections. Section 3.3.1 is to use the OLS to consider the impact of built environment attributes on the duration of COVID-19 for two phases, where the duration for each phase is termed as the time period between the first confirmed case and the last confirmed case. In section 3.3.2, we further investigate the association of COVID-19 confirmed cases and the built environment. The models are detailed in the following subsections in which Section 3.3.1 discusses the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates, while Section 3.3.2 portrays the count data analysis.

3.3.1. Duration model for risk analysis (OLS analysis)

As inspired by the recent study [27], the impact of the built environment on the duration of the COVID-19 can be modelled as the linear function of a series of the built environment attributes. The mathematical presentation is shown as follows

| (2) |

where E[ln(Days i)] is the expected duration of COVID-19 in i-th TPU, Control i, and Built i, are the same variables as indicated in Section 3.2.

3.3.2. Count data models

To carry out the analysis as regards the association between the reported confirmed cases and the built environment, we will utilize the count data models. Three main types of count data models, namely Poisson regression, negative binomial regression, and zero-inflated models are widely considered in the existing literature.

3.3.2.1. Poisson regression

Recall that the Poisson probability function is with the mathematical form [28]:

| (3) |

with E[y] = Var(y) = λ, where λ serves as both the mean and variance of the Poisson model. The investigation of association analysis is to relate the parameter λ to the covariates X such that X = {Control, Built}. Mathematically, the function form is shown as follows:

| (4) |

where Control i , and Built i share the same meaning of section 3.2, γ j (j = 0, 1, 2) are the coefficients to be estimated.

3.3.2.2. Negative binomial regression

The probability function of the negative binomial distribution is of the mathematical form:

| (5) |

The mean and variance of random variable y are E(y) = λ and Var(y) = λ + αλ2, respectively. The link of association to the built environment is similar to the Poisson regression above, which is

| (6) |

where the θ j (j = 0, 1, 2) are the coefficients that need to be estimated, the other terms remain the same as equation (4). The usage of θ j is because the estimation of equation (6) relates to the negative binomial model rather than equation (4) that relates to the Poisson model.

3.3.2.3. Zero-inflated models

On seeing the distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases in Hong Kong, not all the TPUs are reported to have cases. As such, the i-th TPU consists of “zero” confirmed cases that may not be well handled by the aforementioned models (i.e. Poisson regression and negative binomial regression). To tackle this issue, the mixture model that incorporates the zeros and the above count data model is considered for the following analysis. Without losing generality, the mathematical equation is shown as follows

| (7) |

where p(y i) is the count data distribution in the i-th TPU as listed above and stands for the uncertainty parameter.

4. Results and discussion

The statistical results are summarized in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9a, Table 9b, Table 10, Table 11 . Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 report the results of Phase 1 (from January 8 to June 15), and Table 7, Table 8, Table 9a, Table 9b, Table 10, Table 11 display the results of Phase 2 (from June 16 to August 30). All the statistical results were performed using Stata/MP 16.

Table 3.

Summary of test of proportional hazards assumption (Phase 1).

| Variable | Rho | Chi2 | Degree of freedom | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age65_O20 | −0.1072 | 1.38 | 1 | 0.2393 |

| Age65_14 | −0.0891 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.3714 |

| Population | 0.0609 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.5153 |

| HSize | 0.0213 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.8169 |

| WorkDT | −0.0701 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.4416 |

| Pub_Housing | 0.0567 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.5949 |

| PublicDom | −0.0427 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.5618 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.0134 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.8676 |

| N_Clinic | 0.0470 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.6186 |

| N_Restaurant | 0.0146 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.8758 |

| N_PublicMarket | 0.0369 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.7392 |

| N_MTRE | −0.0597 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.4946 |

| D_Clinic | 0.0072 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.9347 |

| D_Restaurant | 0.0344 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.7633 |

| D_PublicMarket | 0.0310 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.7117 |

| D_MTRE | 0.0318 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.7902 |

| Global test | 4.27 | 16 | 0.9983 |

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Phase 1 denotes the period from January 8 to June 15, 2020.

Table 4.

Summary of OLS for the duration in Phase 1.

| Model 2 (Dependent Variable: ln(DurFP) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t-stat | p-value |

| Age65_O20 | 0.1540 | 0.36 | 0.718 |

| Age65_14 | 0.0574 | 0.15 | 0.877 |

| Population | 2.2355* | 2.23 | 0.027 |

| HSize | 2.8015* | 2.11 | 0.037 |

| WorkDT | −1.3115 | −1.48 | 0.140 |

| Pub_Housing | −0.0515 | −0.87 | 0.386 |

| PublicDom | −0.3779 | −0.59 | 0.558 |

| Pert_Pub | −0.0260 | −0.02 | 0.985 |

| N_Clinic | 0.2239 | 1.27 | 0.208 |

| N_Restaurant | 0.1914* | 2.00 | 0.047 |

| N_PublicMarket | −0.1623 | −0.35 | 0.724 |

| N_MTRE | 0.0062 | 0.04 | 0.971 |

| D_Clinic | −0.0779 | −0.29 | 0.770 |

| D_Restaurant | 0.0948 | 0.70 | 0.487 |

| D_PublicMarket | 0.1346 | 0.64 | 0.523 |

| D_MTRE | 0.0392 | 0.20 | 0.844 |

| Breusch-Pagan | 0.07 | 0.794 | |

| Jarque-Bera | 4.58 | 0.101 | |

| R-Squared | 0.3025 | ||

| N | 154 | ||

Note: 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

2. Null Hypothesis of Breusch-Pagan Test: Constant variance is preferable.

3. Null Hypothesis of Jarque-Bera Test: Normality is preferable.

4. Phase 1 denotes the period from January 8 to June 15, 2020.

Table 5.

Model Selection Tests of Confirmed cases in Phase 1.

| CaseFP |

ΔCasesFP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test-stat | p-vaule | Test-stat | p-vaule | |

| LR Test 1 | 222.59*** | 0.000 | 51.99*** | 0.000 |

| (Poisson vs. Negative Binomial) | ||||

| Vuong Test 1 | 2.32** | 0.010 | 1.76* | 0.039 |

| (ZIP vs. Poisson) | ||||

| LR Test 2 | 158.52*** | 0.000 | 31.30*** | 0.000 |

| (ZIP vs. ZINB) | ||||

| Vuong Test 2 | 0.00 | 0.501 | −0.01 | 0.500 |

| (ZINB vs. Negative Binomial) | ||||

| 2Zeros | 28 | 48 | ||

| 1N | 154 | 154 |

Note: 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4. ZIP is short for Zero-inflated Poisson regression model, ZINB is short for Zero-inflated negative binomial model. LR is short for the log-likelihood ratio.

5. Zero shows the number of tertiary planning units (TPUs) does not appeared the COVID-19 confirmed cases.

6. Null Hypothesis of LR test 1: Poisson model is preferable.

7. Null Hypothesis of Vuong Test 1: Standard Poisson model is preferable.

8. Null Hypothesis of LR test 2: ZIP is preferable.

9. Null Hypothesis of Vuong Test 2: Negative Binomial Regression is preferable.

10.4. Phase 1 denotes the period from January 8 to June 15, 2020.

The number of ΔCasesFP is 153 as there is one TPU is negative.

Zeros is only used for ZIP and ZINB.

Table 6.

Results of negative binomial regression in phase 1.

| Model 3 (DV. CaseFP) |

Model 4 (DV: ΔCasesFP) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | z-value | p-value | IRR | z-value | p-value | |

| Age65_O20 | 0.9952 | −0.02 | 0.985 | 1.0212 | 0.11 | 0.938 |

| Age65_14 | 1.4915* | 1.97 | 0.049 | 1.3036 | 1.14 | 0.253 |

| Population | 1.0003** | 3.34 | 0.001 | 1.0000* | 2.48 | 0.013 |

| HSize | 2.0652** | 2.83 | 0.005 | 1.5614* | 1.57 | 0.042 |

| WorkDT | 0.9999** | −3.10 | 0.002 | 0.9999* | −2.39 | 0.017 |

| Pub_Housing | 0.9999 | −0.17 | 0.865 | 0.9999 | −0.35 | 0.724 |

| PublicDom | 0.8390 | −0.51 | 0.612 | 1.0659 | 0.15 | 0.879 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.7693 | −0.44 | 0.661 | 1.1351 | 0.18 | 0.853 |

| N_Clinic | 1.0023 | 1.14 | 0.256 | 1.0013 | 0.62 | 0.533 |

| N_Restaurant | 1.0024** | 2.79 | 0.005 | 1.0024** | 3.44 | 0.001 |

| N_PublicMarket | 1.0971 | 1.12 | 0.262 | 1.0493 | 0.55 | 0.582 |

| N_MTRE | 1.0207 | 0.88 | 0.381 | 1.0408 | 1.67 | 0.096 |

| D_Clinic | 0.9996 | −1.69 | 0.090 | 0.9996 | −1.57 | 0.117 |

| D_Restaurant | 1.0004 | 1.21 | 0.227 | 0.9998 | −0.32 | 0.748 |

| D_PublicMarket | 1.0002* | 2.01 | 0.044 | 1.0003** | 3.19 | 0.001 |

| D_MTRE | 0.9999 | −0.30 | 0.766 | 0.9999 | −0.12 | 0.905 |

| constant | 0.2304 | −1.66 | 0.098 | 0.2098 | −1.62 | 0.106 |

| Log-likelihood | −396.98 | −288.70 | ||||

| N | 154 | 154 | ||||

Note: 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. DV is short for dependent variable. IRR is short for incidence rate ratio.

2. absΔCasesFP stands for taking the absolute value of ΔCasesFP.

3. Phase 1 denotes the period from January 8 to June 15, 2020.

Table 7.

Summary Statistics of Cox regression of Phase 2.

| Variable |

Model 5 (Dependent Variable: DurFCJA) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | z-stat | p-value | |

| Age65_O20 | 1.5328 | 1.54 | 0.122 |

| Age65_14 | 2.0083** | 2.72 | 0.006 |

| Population | 1.0000 | 0.31 | 0.758 |

| HSize | 0.6908 | −1.40 | 0.161 |

| WorkDT | 0.9999 | −0.48 | 0.633 |

| Pub_Housing | 1.0000 | 0.95 | 0.340 |

| PublicDom | 1.6908 | 1.21 | 0.227 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.5791 | −0.88 | 0.376 |

| N_Clinic | 1.0076** | 2.75 | 0.006 |

| N_Restaurant | 1.0004 | 0.43 | 0.666 |

| N_PublicMarket | 1.3473* | 2.15 | 0.031 |

| N_MTRE | 1.0014 | 0.05 | 0.959 |

| D_Clinic | 0.9998 | −1.03 | 0.302 |

| D_Restaurant | 1.0005 | 1.27 | 0.206 |

| D_PublicMarket | 1.0004** | 3.12 | 0.002 |

| D_MTRE | 0.9998* | −2.10 | 0.036 |

| CaseFP | 1.0214 | 1.41 | 0.160 |

| log-likelihood | −577.9092 | ||

| No. of subjects | 154 | ||

| No. of failures | 143 | ||

| N | 154 | ||

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Phase 2 denotes the period from June 16 to August 30, 2020.

Table 8.

Summary of test of proportional hazards assumption (Phase 2).

| Variable | Rho | Chi2 | Degree of freedom | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age65_O20 | 0.1037 | 1.42 | 1 | 0.2338 |

| Age65_14 | 0.0548 | 0.39 | 1 | 0.5299 |

| Population | 0.0935 | 1.69 | 1 | 0.1936 |

| HSize | 0.0957 | 1.26 | 1 | 0.2615 |

| WorkDT | −0.0804 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.2904 |

| Pub_Housing | −0.0937 | 1.16 | 1 | 0.2817 |

| PublicDom | −0.0233 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.7343 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.0568 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.4326 |

| N_Clinic | −0.0070 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.9385 |

| N_Restaurant | 0.0642 | 0.90 | 1 | 0.3439 |

| N_PublicMarket | −0.0612 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.3041 |

| N_MTRE | −0.0071 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.9259 |

| D_Clinic | 0.0689 | 0.53 | 1 | 0.4648 |

| D_Restaurant | 0.0184 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.8274 |

| D_PublicMarket | −0.0525 | 0.60 | 1 | 0.4394 |

| D_MTRE | 0.0568 | 0.70 | 1 | 0.4012 |

| CaseFP | −0.0804 | 1.10 | 1 | 0.2941 |

| Global test | 5.85 | 17 | 0.9941 |

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Phase 2 denotes the period from June 16 to August 30, 2020.

Table 9a.

Summary of OLS for the duration in Phase 2.

| Model 6 (Dependent Variable: ln(DurSP) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | St. Err. | t-stat | p-value |

| Age65_O20 | 0.3587 | 0.2901 | 1.24 | 0.219 |

| Age65_14 | 0.3371 | 0.2479 | 1.36 | 0.177 |

| Population | −1.7216* | 0.6891 | −2.50 | 0.014 |

| HSize | −3.1526** | 0.9204 | −3.43 | 0.001 |

| WorkDT | 1.7251** | 0.6143 | 2.81 | 0.006 |

| Pub_Housing | −0.0136 | 0.0397 | −0.34 | 0.731 |

| PublicDom | 0.1868 | 0.4226 | 0.44 | 0.659 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.2407 | 0.9110 | 0.26 | 0.792 |

| N_Clinic | 0.0171 | 0.1163 | 0.15 | 0.883 |

| N_Restaurant | 0.1473* | 0.0689 | 2.14 | 0.035 |

| N_PublicMarket | 0.3331 | 0.2879 | 1.16 | 0.250 |

| N_MTRE | −0.0755 | 0.1125 | −0.67 | 0.504 |

| D_Clinic | −0.2512 | 0.1825 | −1.38 | 0.172 |

| D_Restaurant | 0.1038 | 0.0852 | 1.22 | 0.226 |

| D_PublicMarket | 0.4361** | 0.1461 | 2.98 | 0.004 |

| D_MTRE | 0.0017 | 0.1453 | 0.01 | 0.991 |

| CaseFP | 0.2563* | 0.1043 | 2.46 | 0.016 |

| Constant | 5.3862* | 2.4679 | 2.18 | 0.031 |

| Breusch-Pagan | 28.28*** | 0.000 | ||

| Jarque-Bera | 38.41*** | 0.000 | ||

| R-Squared | 0.4705 | |||

| N | 154 | |||

Note: 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

2. Null Hypothesis of Breusch-Pagan Test: Constant variance is preferable.

3. Null Hypothesis of Jarque-Bera Test: Normality is preferable.

4. Phase 2 denotes the period from June 16 to August 30, 2020.

Table 9b.

Summary of OLS for the duration in Phase 2.

| Model 7 (Dependent Variable: ln(DurSP) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Robust St. Err. | t-stat | p-value |

| Age65_O20 | 0.3587 | 0.3505 | 1.02 | 0.308 |

| Age65_14 | 0.3371 | 0.2865 | 1.18 | 0.242 |

| Population | −1.7216* | 0.7919 | −2.17 | 0.032 |

| HSize | −3.1526** | 1.0395 | −3.03 | 0.003 |

| WorkDT | 1.7251** | 0.7120 | 2.42 | 0.017 |

| Pub_Housing | −0.0136 | 0.0381 | −0.36 | 0.721 |

| PublicDom | 0.1868 | 0.3218 | 0.58 | 0.563 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.2407 | 0.8819 | 0.27 | 0.785 |

| N_Clinic | 0.0171 | 0.1007 | 0.17 | 0.865 |

| N_Restaurant | 0.1473* | 0.0636 | 2.31 | 0.023 |

| N_PublicMarket | 0.3331 | 0.2215 | 1.50 | 0.136 |

| N_MTRE | −0.0755 | 0.1062 | −0.71 | 0.479 |

| D_Clinic | −0.2512 | 0.1769 | −1.42 | 0.159 |

| D_Restaurant | 0.1038 | 0.0703 | 1.48 | 0.143 |

| D_PublicMarket | 0.4361** | 0.1322 | 3.30 | 0.001 |

| D_MTRE | 0.0017 | 0.1493 | 0.01 | 0.991 |

| CaseFP | 0.2563* | 0.1332 | 1.93 | 0.057 |

| Constant | 5.3862* | 2.2103 | 2.44 | 0.016 |

| R-Squared | 0.4705 | |||

| N | 154 | |||

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Phase 2 denotes the period from June 16 to August 30, 2020.

Table 10.

Model Selection Tests of Confirmed cases in Phase 2.

| CaseSP |

ΔCasesSP |

absΔCasesSP |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test-stat | p-vaule | Test-stat | p-vaule | Test-stat | p-vaule | |

| LR Test 1 | 1246.64*** | 0.0000 | 868.24*** | 0.0000 | 867.66*** | 0.0000 |

| (Poisson vs. Negative Binomial) | ||||||

| Vuong Test 1 | 2.25* | 0.0123 | 2.40** | 0.0083 | 2.40** | 0.0083 |

| (ZIP vs. Poisson) | ||||||

| LR Test 2 | 1123.78*** | 0.0000 | 765.46*** | 0.0000 | 765.03*** | 0.0000 |

| (ZIP vs. ZINB) | ||||||

| Vuong Test 2 | 0.25 | 0.4002 | 0.00 | 0.5003 | 0.00 | 0.5013 |

| (ZINB vs. Negative Binomial) | ||||||

| Zeros | 11 | 11 | 11 | |||

| ⁑N | 154 | 153 | 154 |

Note: 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. absΔCasesSP stands for taking the absolute value of ΔCasesSP.

2. ⁑The number of ΔCasesFP is 153 as there is one TPU is negative.

3. † Zeros is only used for ZIP and ZINB.

4. ZIP is short for Zero-inflated Poisson regression model, ZINB is short for Zero-inflated negative binomial model. LR is short for the log-likelihood ratio.

5. Zero shows the number of tertiary planning units (TPUs) does not appeared the COVID-19 confirmed cases.

6. Null Hypothesis of LR test 1: Poisson model is preferable.

7. Null Hypothesis of Vuong Test 1: Standard Poisson model is preferable.

8. Null Hypothesis of LR test 2: ZIP is preferable.

9. Null Hypothesis of Vuong Test 2: Negative Binomial Regression is preferable.

10. Phase 2 denotes the period from June 16 to August 30, 2020.

Table 11.

Results of negative binomial regression in phase 2.

| Model 8 (DV. CaseSP) |

Model 9 (DV: ΔCasesSP) |

Model 10 (DV: absΔCasesSP) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | z-value | p-value | IRR | z-value | p-value | IRR | z-value | p-value | |

| Age65_O20 | 1.3134 | 1.16 | 0.246 | 1.3242 | 1.13 | 0.259 | 1.3239 | 1.13 | 0.259 |

| Age65_14 | 1.4819 | 1.77 | 0.076 | 1.4301 | 1.56 | 0.118 | 1.4300 | 1.56 | 0.118 |

| Population | 0.9999 | −0.16 | 0.873 | 1.0000 | 0.64 | 0.522 | 1.0000 | 0.64 | 0.522 |

| HSize | 0.3726** | −3.48 | 0.001 | 0.4180** | −3.12 | 0.002 | 0.4181** | −3.12 | 0.002 |

| WorkDT | 1.0000 | 0.71 | 0.476 | 0.9999 | −0.01 | 0.989 | 0.9999 | −0.01 | 0.989 |

| Pub_Housing | 1.0000 | 0.73 | 0.464 | 1.0000 | 0.58 | 0.562 | 1.0000 | 0.58 | 0.562 |

| PublicDom | 1.5056 | 1.25 | 0.211 | 1.1815 | 0.55 | 0.582 | 1.1813 | 0.55 | 0.582 |

| Pert_Pub | 0.6025 | −0.61 | 0.541 | 0.8599 | −0.21 | 0.832 | 0.8602 | −0.21 | 0.832 |

| N_Clinic | 0.9977 | −1.00 | 0.320 | 0.9976 | −0.97 | 0.333 | 0.9976 | −0.97 | 0.333 |

| N_Restaurant | 1.0016* | 2.47 | 0.013 | 1.0014* | 2.24 | 0.025 | 1.0014* | 2.24 | 0.025 |

| N_PublicMarket | 1.0553 | 0.64 | 0.524 | 1.0113 | 0.13 | 0.896 | 1.0113 | 0.13 | 0.896 |

| N_MTRE | 1.0036 | 0.16 | 0.870 | 1.0062 | 0.29 | 0.774 | 1.0062 | 0.29 | 0.774 |

| D_Clinic | 0.9997 | −1.55 | 0.122 | 0.9997 | −0.92 | 0.358 | 0.9997 | −0.92 | 0.359 |

| D_Restaurant | 1.0003 | 0.73 | 0.462 | 1.0002 | 0.48 | 0.632 | 1.0002 | 0.48 | 0.632 |

| D_PublicMarket | 1.0001 | 1.04 | 0.297 | 1.0000 | 0.25 | 0.803 | 1.0000 | 0.25 | 0.804 |

| D_MTRE | 0.9999 | −0.77 | 0.444 | 0.9999 | −0.71 | 0.477 | 0.9999 | −0.71 | 0.477 |

| Δ_negative | 0.193*** | −6.38 | 0.000 | ||||||

| constant | 101*** | 4.85 | 0.000 | 68.84*** | 4.55 | 0.000 | 68.82*** | 4.55 | 0.000 |

| Log-likelihood | −565.83 | −543.99 | −545.28 | ||||||

| N | 154 | 153 | 154 | ||||||

Note: 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. DV is short for dependent variable.

2. Δ_negative is a dummy variable, which is used to indicate whether the ΔCasesSP is negative.

3. absΔCasesSP stands for taking the absolute value of ΔCasesSP.

4. Phase 2 denotes the period from June 16 to August 30, 2020.

4.1. Results of phase 1

4.1.1. Survival analysis in phase 1 (from Jan. 8 to Jun. 15)

As suggested by Fig. 4, we first consider the association between the built environment and the risk of infecting COVID-19. The results of the Cox model are shown in Table 2. Five variables are detected to be significant. They are Population, HSize, WorkDT, N_Clinic, and D_Restaurant. The magnitude of the Population is slightly greater than one (1.0001, Table 2), indicating that the TPU with a high population would bear a high risk of COVID-19. Similarly, the significant value of the hazard ratio of HSize (2.2878, Table 2) indicates that more interaction between family members provided that household size is large, the higher risk of COVID-19 infection. Surprisingly, the hazard ratio of WorkDT (0.9998, Table 2) is found to be significant with a magnitude is less than one. The significance of N_Clinic (1.0057, Table 2) may exhibit that people in the TPU with more clinics have a high risk of being infected by COVID-19. Another significant built environment variable D_Restaurant is found to have a hazard ratio with a scale slightly larger than one (1.0007, Table 2).

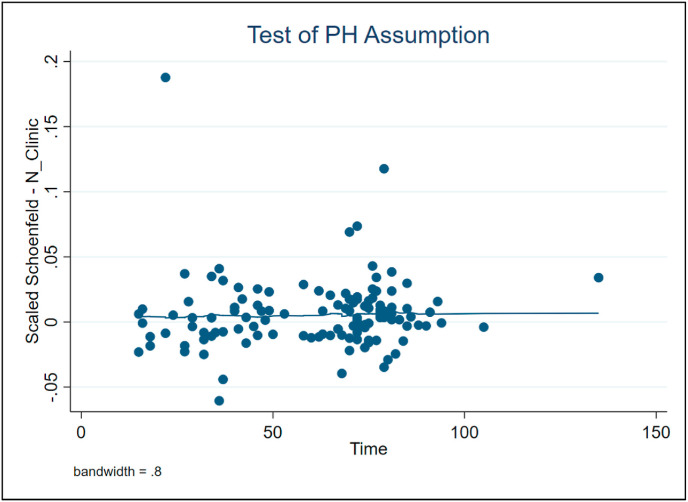

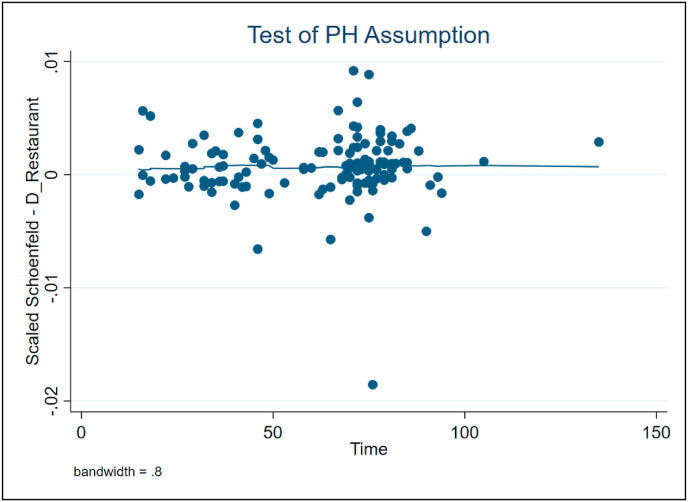

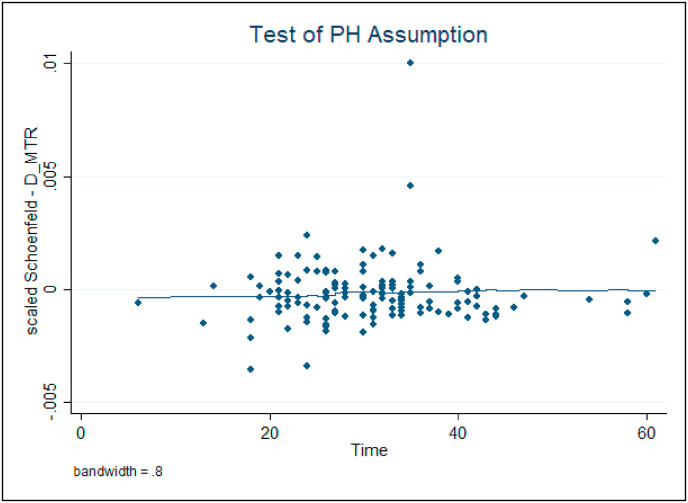

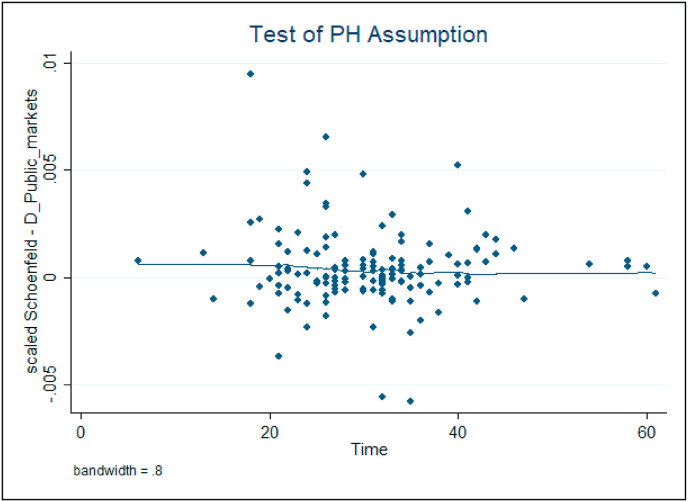

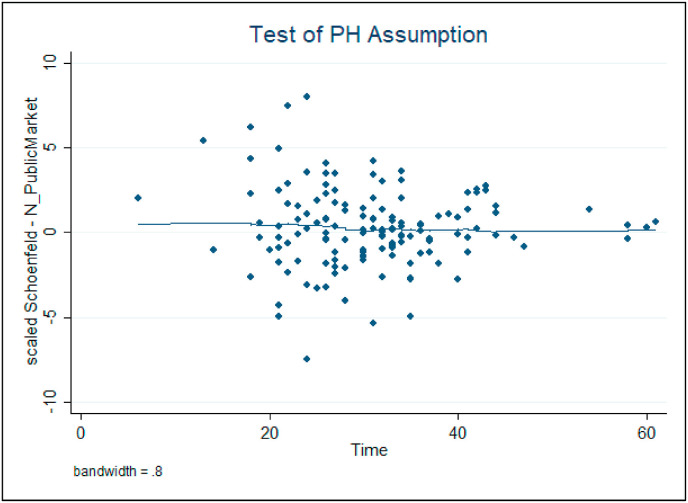

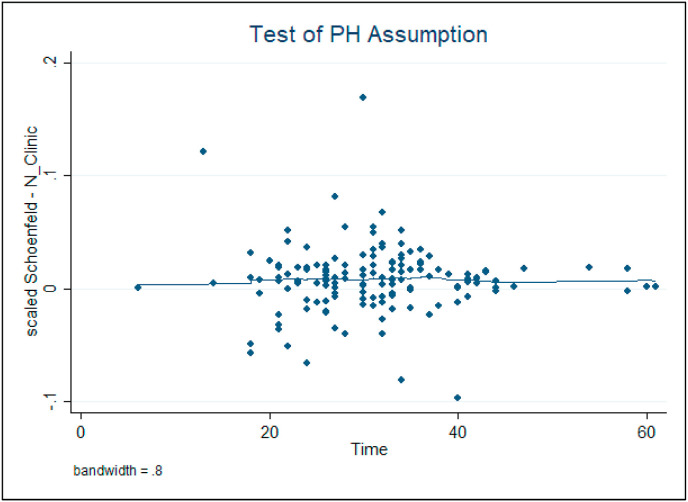

The validity of the statistical results in Table 2 should not violate the Cox proportion hazard assumption. In this regard, we would like to consider the Schoenfeld Residuals tests for the Cox model. The residual plots of the significant variables N_Clinic and D_Restaurant are shown in Figure B.1 and B.2 (See Appendice, Section B), respectively. It is easy to observe that both of these two graphs have zero slopes, indicating that they do not violate the assumption of the Cox model. Moreover, the test results for the proportional hazard assumption for the rest of the variables are summarized in Table 3. None of them are detected to be significant, suggesting that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the data meets the proportional hazard assumption.

4.1.2. Ordinary least squares (OLS) analysis in phase 1(from Jan. 8 to Jun. 15)

We employ OLS to consider the association between the built environment and the duration of suffering the COVID-19. The results are demonstrated in Table 4, where only three variables are found to be significant, namely Population, HSize, and N_Restaurant. The TPU with high population density and large household size would lead to a longer period of COVID-19. If a TPU has more restaurants, people have a long period to bear the risk of the spread of COVID-19. During the period of Phase 1, the Hong Kong government issued the social distancing measure on March 29, which states that group gatherings with more than 4 people are prohibited and restaurants must ensure there is a distance of at least 1.5 m between tables [[29], [30]]. The social distancing measure to some extent limited the scale of group gathering rather than entirely restricting the group gathering. In Hong Kong, restaurants are served as an important built environment to enable people to have more social interactions and compensate tiny living space to cook food. People in Hong Kong heavily rely on a different kind of restaurant in their daily life. As such, the Hong Kong government has to make a difficult decision to restrict the group gathering size instead of forcing all the restaurants to shut down for some days or weeks. In this regard, more restaurants in the TPU may give rise to more exposure of COVID-19 to the residents.

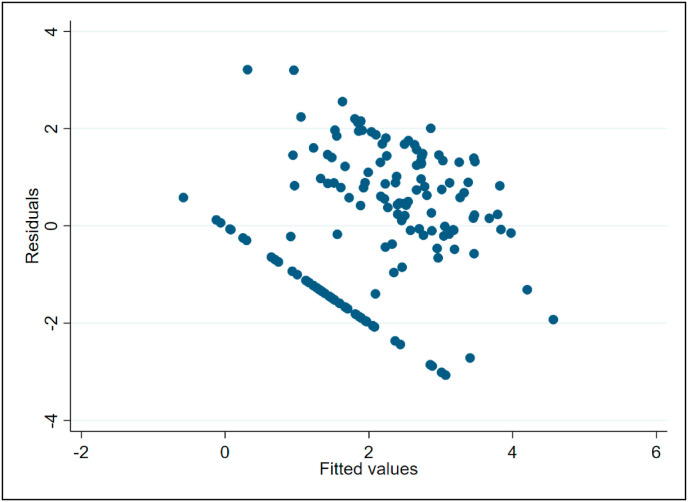

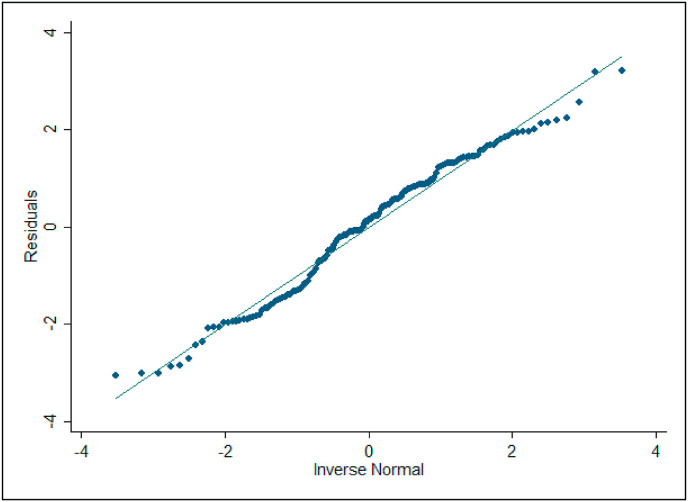

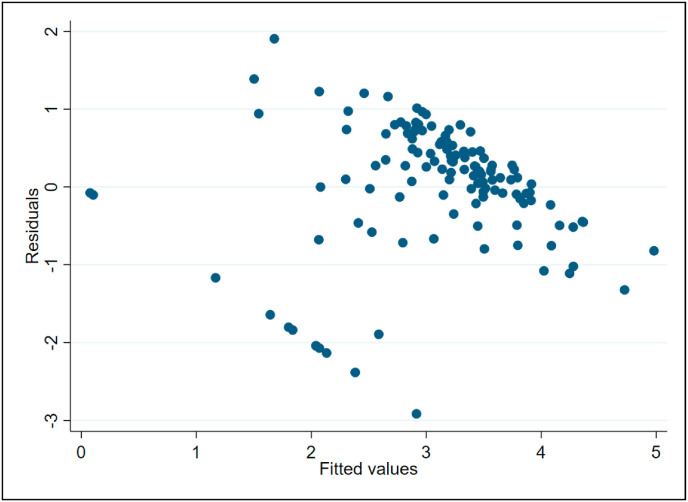

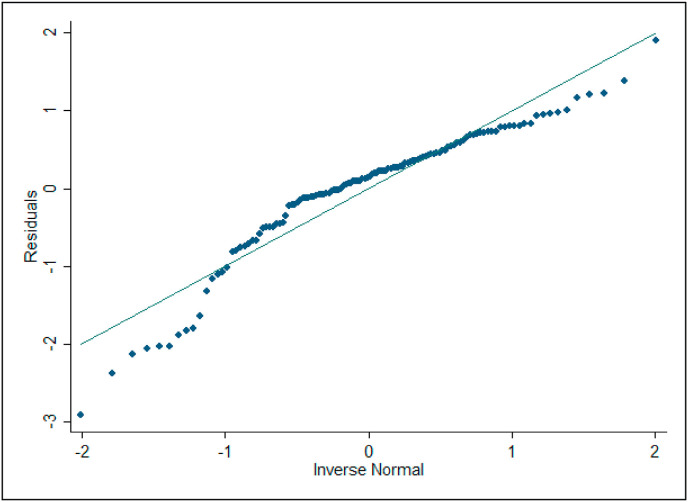

We intend to check the heteroscedasticity (see Appendices, section A1) of the OLS presented in Table 4. The statistics of the Breusch-Pagan test is 0.07 (p-value = 0.794, Table 4), which is in line with the residuals - versus - fitted plot (Figure B.3, in Appendices). It suggests that we do not find evidence of heteroscedasticity. Also, we need to check whether the residuals of OLS in Table 4 is normal. The insignificant result of the Jarque-Bera test (4.58, with p-value = 0.101, Table 4), which echoes with the Q-Q plot (Figure B4, in Appendices) that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of the Jarque-Bera test (the residuals follow a normal distribution).

4.1.3. Count data analysis in phase 1 (from Jan. 8 to Jun. 15)

Using OLS is not enough to unveil the association between the built environment and duration of suffering the COVID-19 as the analysis of OLS does not consider the size of confirmed cases in TPU. For such purpose, we consider the association between the built environment and the risk of COVID-19 in terms of the reported cases. As suggested in Section 3, there is more than one choice to model the reported COVID-19 cases. Before we explain the model results, it is necessary to discuss the legitimacy of picking up the negative model as a reasonable choice for this study. On seeing the patterns of COVID-19 confirmed cases in Fig. 2a and b, it is easy to identify that some TPUs have no confirmed case, which motives us to model the data with zero-inflated Poisson regression and zero-inflated negative binomial regression.

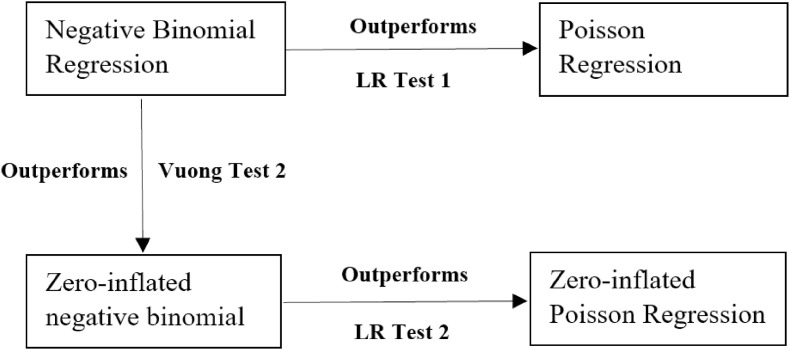

As such, we conduct four statistical tests for the model selection, where the results are displayed in Table 5. Considering that there are two different dependent variables in Phase 1 (Table 5), therefore eight scenarios in total need to be considered. It is straightforward to see that all test-statistics of LR test 1 (Poisson vs. Negative Binomial) and LR test 2 (ZIP vs. ZNIB) are significant. The significance of the statistics of LR test 1 implies that, on comparing the Poisson regression and the negative binomial model, the latter one is preferable for CaseFP and ΔCasesFP. Similarly, the significant test statistics of LR test 2 demonstrates that the zero-inflated negative binomial model is preferable to that of zero-inflated Poisson regression. As none of the statistics of Vuong Test 2 is significant, illustrating that the negative binomial regression is more reasonable than the zero-inflated negative binomial regression for all scenarios. By incorporating the results of LR test 1 and LR test 2, the negative binomial regression outperforms the Poisson regression, and the ZINB is better fitted than ZIP. In other words, the results of Vuong Test 1 would not affect the final result of model selections (Fig. 5 ). To warp up, the negative binomial model outperforms the other three models (see Fig. 5), which is reasonable and appropriate for CaseFP and ΔCasesFP. The following analysis will be carried out based on the negative binomial regression analysis.

Fig. 5.

Model selection for count data analysis.

Table 6 reports the association of the built environment and the COVID-19 confirmed cases from late January to mid-June in 2020. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) is used to present the model results in the following context as the IRR is a relative difference measure utilized to compare the incidence rates of events occurring at a given point of time in epidemiology [[31], [32]]. The magnitude of significant IRR greater than 1 in the negative binomial regression model indicates the greater or higher the variables are, the more likely they are to increase the infected COVID-19 cases (or the spread of COVID-19), otherwise, it implies that they are less likely to increase COVID-19 infected cases.

In the beginning, we consider the total COVID-19 confirmed cases in Phase 1 (Model 3, Table 6). The model results show that six variables are significant (Model 3, Table 6). They are Age65_14, Population, HSize, WorkDT, N_Restaurant, and D_PublicMarket. Specifically, the coverage of age 65 or above in TPU between 14% and 20% have a relatively high risk of COVID-19 by 49.15% than other TPU areas where the percentage of age 65 or above is between 7% and 14%. A TPU with high population density is found to be slightly high exposure to COVID-19 (1.0003, Model 3 of Table 6). Besides the population, we also found that one more family member in the household likely increases the risk of infection of COVID-19 by 106.52% (2.0652, Table 6). A household of large size implies more interactions between the family members such that the virus of COVID-19 is more likely to spread among family members. Surprisingly, the IRR of WorkDT is determined to be smaller than one (0.9999, Table 6). A possible explanation is that a large number of companies shifted the working style from “work at the office” to “work from home”. Employees keep themselves stand-by in front of the smart devices’ screen for the workdays, equivalently to be isolated at home passively. N_Restaurant and D_PublicMarket are the two built environment variables that are found to be significant. It outlines that purchasing fresh food in public markets and having meals in the restaurants are the two necessities and basic needs of Hong Kongers such that they bear a high risk of being infected COVID-19 when visiting these two built environments.

Considering that the Hong Kong government issued the social distancing measure on March 29, we expect to explore the association between the built environment and the changes of confirmed cases, which is comparing the cases before and after the social distancing measures in Phase 1. We change the dependent variable as ΔCasesFP, which is the difference of reported confirmed cases after and before the social distancing measure. The results are reported in Model 4 (Table 6), which are similar to that of Model 3. Though social distancing measure was in force from late March, the restaurants and public markets are founded to be the two built environments that influence the transmission of COVID-19.

4.2. Results of phase 2 (from Jun. 16 to Aug. 30)

The statistical results of Phase 2 are shown in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9a, Table 9b, Table 10, Table 11 Table 7 reports the survival analysis of the Cox regression of Phase 2, which documents what built environment given the social distancing measure was relaxed, would induce the new wave of COVID-19. Four built environment variables, that is the number of clinics (N_Clinic), the number of public markets (N_PublicMarket), the distance to the nearest public markets (D_PublicMarket), and the distance to the nearest entrances of the MTR (D_MTRE). On checking the residual plots of these four variables (Figure B.5-B.8 in Appendices), the slops are all zero. The results do not violate the assumption of the Cox model, which is in line with the Schoenfeld Residuals tests displayed in Table 8.

We then consider the association between the built environment and the duration of suffering the COVID-19. We consider the association between the built environment and the duration of suffering the COVID-19. Distinguished to the results presented in Phase 1 (Table 4, and Figure B.3), we have observed the problems of heteroscedasticity (Table 9a, and Figure B.9 in Appendices) and not following normal distribution (Table 9a, and Figure B.10 in Appendices), where the Breusch-Pagan test and Jarque-Bera statistics are found to be significant with a coefficient of 28.28 (p-value = 0.000, Table 9a) and 38.41(p-value = 0.000, Table 9a), respectively. To tackle this issue, estimation is a remedy by using the robust standard error (Table 9b). On comparting to the result in Phase 1, two built environment variables are found to be significant. They are N_Restaurant and D_PublicMarket. Relaxing social distancing measures provides a signal for all the residents to resume normal social interaction, which could be well explained why restaurants and public markets may induce a long time suffering from COVID-19 in Phase 2.

We further investigate the association between the built environment and COVID-19 confirmed cases in Phase 2. Like what has been shown in the previous section, a model selection should be made before addressing the model results. By following the same strategy in section 4.2.3, the results shown in Table 10 delineate that negative binomial regression is the legitimacy for the count data analysis in Phase 2. The estimations of negative binomial models are summarized in Table 11. Only one built environment variable (i.e. N_Restaurant) is significant with IRR greater than one. More restaurants in the TPU provide convenience for social interaction, and however, it is also the risk area that virus can be spread among people through resuming normal social interaction. It also implies that the Hong Kong government underestimated the risk of the COVID-19 and relaxed social distancing measures with undue haste.

5. Conclusions

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has soon become a very high concern to the public as it led to the infection, death of thousands of people worldwide at a fast speed. The existing literature as regards COVID-19 are clustered on studying the infection rate, and which NPI would effectively decrease the infection rate. However, the relationship between the built environment and the spread of COVID-19 has not been well addressed in the literature. To fill this knowledge gap, this paper is a pioneering work to study two research questions: (1) What are the association of the built environment with the risk of being infected by the COVID-19? (2) What are the association of the built environment with the duration of suffering from COVID-19? These two research questions align with our proposition that the heterogeneous spread of COVID-19 is based on the characteristics of the built environment.

Using the census statistics on TPU level in 2016, a large sample of built environment data and confirmed cases of COVID-19 from the Hong Kong government, the analysis is conducted based on two time period, that is Phase 1 (from January 8 to June 15) (when the social distancing was tight) and Phase 2 (between June 16 and August 30) (after the social distancing was slightly relaxed). In each phase, we have considered the association between the built environment and the risk of being infected by COVID-19, then we have carried out the analysis about the association between the built environment and duration of suffering the COVID-19, last but not least, the association between the built environment and reported COVID-19 confirmed cases have been measured and quantified.

The statistics of the survival model (i.e. Cox model) herein shed light on what built environments induce the prevalence of COVID-19 confirmed cases. In Phase 1, we found that the clinics and restaurants are the two built environments that are more likely to influence the prevalence of COVID-19. In Phase 2, we discovered that MTR, public market, and the clinics are the built environments that influence the prevalence of COVID-19. The results of OLS models disclose what built environments induce a long time suffering from the COVID-19. In Phase 1, the areas of TPUs with more restaurants are found to be positively associated with the period of the prevalence of COVID-19. In Phase 2, we found that restaurants and public markets are the two key built environments induce long time occurrence of the COVID-19. The statistical results of the negative binomial models report the association between the built environment and the severity of the COVID-19. In Phase 1, restaurant and public markets are the two built environments that influence the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases. In Phase 2, we found that the number of restaurants is positively related to the number of COVID-19 reported cases. To recap, public markets and restaurants are the two built environments that influence the transmission of the COVID-19 in both phases. It is suggested that the government should not be too optimistic to relax the social distancing measure even the COVID-19 confirmed cases decline to be single-digit level. Without seeing the signals of the COVID-19 die out, the social distancing measure should remain in force to avoid the large-scale outbreak.

The limitation of this research lies in the following dimensions, which could be potentially fruitful directions for future research. In the first place, this study employs survival analysis (i.e. Cox model), ordinary least square method, and count data analysis to study the link between the built environment and the spread of COVID-19. These methods focus on cross-sectional analysis only. Future studies should consider longitude analysis, which incorporates both time and location information. In the second place, this study is carried out based on the aggregate level of census data, the future study should be conducted on the micro-scale (i.e. individual data). In the third place, the analysis covered in this study follows the indirect manner, which investigates the impacts of static indicators (e.g. number of the built environment facilities and distance to the built environment facilities) on the spread of COVID-19. However, people's social behaviour such as whether people strictly follow the social distancing measure with no more than 4 people in group gathering in restaurants should be considered in future studies. Last but not least, the study only covers one city, future research should also consider the built environment and the spread of the COVID-19 at the regional level or cross-country level.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Fig. B.1.

Test of Cox model assumption for N_Clinic (phase 1)

Fig. B.2.

Test of Cox model assumption for D_Restaurant (phase 1)

Fig. B.3.

Residual - versus - fitted plot for testing the heteroscedasticity (phase 1)

Fig. B.4.

Q-Q plot of residuals for OLS (phase 1)

Fig. B.5.

Test of Cox model assumption for D_MTRE (phase 2)

Fig. B.6.

Test of Cox model assumption for D_Public_markets (phase 2)

Fig. B.7.

Test of Cox model assumption for N_Public_markets (phase 2)

Fig. B.8.

Test of Cox model assumption for N_Clinic (phase 2)

Fig. B.9.

Residual - versus - fitted plot for testing the heteroscedasticity (phase 2)

Fig. B.10.

Q-Q plot of residuals for OLS (phase 2)

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Research Grants of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Project Codes: 1-YW3L (P0000319)) and the research grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (UGC/IDS16/17).

Appendices

Section A

Utilization of the OLS should follow two assumptions [[33], [34]]: (1) the residual (or error term) of the OLS should not be heteroscedasticity (or called unequal scatter); (2) the residual (or error term) of the OLS should follow the normal distribution. The technical procedures of checking these two assumptions are listed in section 1, 2 below.

A1. Checking the assumption of heteroscedasticity of the OLS (Phase 1).

To check the assumption of heteroscedasticity of the OLS, we first use the data visualization method to capture the patterns, then follow with some solid statistical tests. In specific, the visualization method called residual - versus - fitted plot is commonly used in the existing studies [[33], [34]]. The term residual is equivalent to error term, which in mathematical form can be produced by doing some simple algebra of equation (2) in section 3.3.1: residual = ln(Days i) – E[ln(Days i)] or residual = ln(Days i) – α 0 – α 1 Control i – α 2 Built i. The term fitted means the fitted value is based on the estimated coefficient α k (k = 0, 1, 2). The mathematical form of the fitted value is: , where , , and are the estimated value. The residual - versus - fitted plot of phase 1 is shown in Figure B.3, we can easily observe that some points are clustered, while some other not. The pattern shown in Figure B.3 may not provide a clear idea of whether the residuals are equal scatter. Therefore, we turn to perform the Breusch-Pagan test. The null hypothesis of the Breusch-Pagan test is that the constant variance (or equal scatter) of the error term is preferable [34]. The Breusch-Pagan test in Table 4 shows that the statistics are 0.07, which is found to be not significant (p-value = 0.794, Table 4). The Breusch-Pagan test results suggest that we do not find evidence of heteroscedasticity. In other words, the OLS results satisfy the first assumption.

A2. Checking the assumption of the residual (or error term) of the OLS follows the normal distribution (Phase 1).

As for checking the second assumption, we again employ the scatter plot to identify the pattern, then perform the statistical test. As indicated by Gujarati [34] and Greene [33], the visualization method to check whether the residuals or error terms of the OLS follow normal distribution can rely on a quantile-quantile plot (i.e. Q-Q plot). The Q-Q plot is a graphical method for comparing two probability distributions by plotting their quantiles against each other. In this paper, we first calculate the residuals based on equation (2) in section 3.3.1, which follows the same procedure in checking the heteroscedasticity above (Appendix A1). Then we used the calculated residuals to estimate the quantiles (or cumulative distribution). On knowing the cumulative distribution, we can easily generate the inversed quantile of the standard normal distribution in a theoretical manner. Mathematically, these procedures can be presented as the following two equations:

N−1(probability of residuals) = quantile of residuals (*)

N−1(probability of standard normal distribution) = quantile of a standard normal distribution or called inversed normal (**)

Where N−1(●) stands for the inverse function of standard cumulative normal distribution. If the residuals follow the standard normal distribution, then the plot of the value of (*) and (**) should land on the straight-line y = x. On seeing the patterns of the Q-Q plot in Figure B.4, it is not difficult to see that some points at two extremes are a little bit far away from the straight-line y = x, while the rest of the dots are located closer to the straight-line y = x. The pattern displayed in Figure B.4 may suggest that the residuals follow the normal distribution, we then consider the statistical test to validate what we observe. We employ the Jarque-Bera test. The null hypothesis of the Jarque-Bera test is that the error term follows the normal distribution. The statistics of the Jarque-Bera test in Table 4 is 4.58 (p-value = 0.101), which is not significant. The Jarque-Bera test results echo with the Q-Q plot (Figure B.4) such that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of the Jarque-Bera test (the residuals follow a normal distribution).

A3. Checking two assumptions of the OLS (phase 2).

The analysis of checking two assumptions of the OLS in phase 2 follows the same procedures in Appendices A1 and A2. We first test the heteroscedasticity assumption of the OLS residuals. Then we check whether the residuals follow normal distribution. The patterns displayed in Figure B.9 is very similar to that of Figure B.3. But we cannot identify whether the residuals are heteroscedasticity or not. We therefore need to conduct the Breusch-Pagan test. The statistics are found to be significant with a coefficient of 28.28 (p-value = 0.000, Table 9a), which is distinguished to that of phase 1 (Table 4). We also need to check whether the residuals follow normal distribution. It is easy to see from Figure B.10 that more points are located further away from the fitted line, which maybe the signal that the residuals do not follow normal distribution. The Jarque-Bera test exhibited in Table 9a is significant with coefficient 38.41 (p-value, Table 9a), which again is different from that of phase 1.

References

- 1.Hui D.S., Azhar E.I., Madani T.A., Ntoumi F., Kock R., Dar O., Zumla A. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins University (JHU) Johns. 2020. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering. (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). ArcGIS. Retrieved from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.BBC . 2020. Pneumonia: Hong Kong's "third wave of outbreak of COVID-19". . (in Chinese) Retrieved from:// https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/chinese-news-53344652. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraemer M.U., Yang C.H., Gutierrez B., Wu C.H., Klein B., Pigott D.M., Brownstein J.S. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenham C., Smith J., Morgan R. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):846–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali S.T., Wang L., Lau E.H., Xu X.K., Du Z., Wu Y., Cowling B.J. Serial interval of SARS-CoV-2 was shortened over time by nonpharmaceutical interventions. Science. 2020;369(6507):1106–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.abc9004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo J.R., Cook A.R., Park M., Sun Y., Sun H., Lim J.T., Dickens B.L. Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: a modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(6):P678–P688. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prem K., Liu Y., Russell T.W., Kucharski A.J., Eggo R.M., Davies N., Abbott S. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):E261–E270. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadoni M., Gaeta G. 2020. How Long Does a Lockdown Need to Be?https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.11633 arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.11633. Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolbeault J., Turinici G. 2020. Heterogeneous Social Interactions and the COVID-19 Lockdown Outcome in a Multi-Group SEIR Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.00049. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang W. 2020. Public Health Policy: Covid-19 Epidemic and Seir Model with Asymptomatic Viral Carriers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.06311. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang N., Cheng P., Jia W., Dung C.H., Liu L., Chen W., Xiao S. Impact of intervention methods on COVID-19 transmission in Shenzhen. Build. Environ. 2020;180 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centre for Health Protection (CHP) 2020. Countries/areas with Reported Cases of Coronavirus Disease‐2019.https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/statistics_of_the_cases_novel_coronavirus_infection_en.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelks N.T.O., Hawthorne T.L., Dai D., Fuller C.H., Stauber C. Mapping the hidden hazards: community-led spatial data collection of street-level environmental stressors in a degraded, urban watershed. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2018;15(4):825. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Megahed N.A., Ghoneim E.M. Antivirus-built environment: lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;61:102350. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng C.H., Chow C.L., Chow W.K. Trajectories of large respiratory droplets in indoor environment: a simplified approach. Build. Environ. 2020;183:107196. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao N., An C.K., Guo L.Y., Wang M., Guo L., Guo S.R., Long E.S. Building and Environment; 2020. Transmission Risk of Infectious Droplets in Physical Spreading Process at Different Times: A Review. 107307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y., Ji S. Building and Environment; 2020. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Transport of Droplet Aerosols Generated by Occupants in a Fever Clinic. 107402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Stralen K.J., Dekker F.W., Zoccali C., Jager K.J. Confounding. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2010;116(2):c143–c147. doi: 10.1159/000315883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blocken B., van Druenen T., van Hooff T., Verstappen P.A., Marchal T., Marr L.C. Building and Environment; 2020. Can Indoor Sports Centers Be Allowed to Re-open during the COVID-19 Pandemic Based on a Certificate of Equivalence? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong Kong Planning Department (HKPD) 2016. Hong Kong 2030+: towards a Planning Vision and Strategy Transcending 2030---Land Supply Considerations and Approach.https://www.hk2030plus.hk/document/Land%20Supply%20Considerations%20and%20Approach_Eng.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Census and Statistical Department (CSD) 2020. By Census Result-District Profile-Tertiary Planning Units.https://www.bycensus2016.gov.hk/en/bc-dp-tpu.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centre for Health Protection (CHP) 2020. Data Dictionary for “Details of Probable/confirmed Cases of COVID-19 Infection in Hong Kong”.https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/nid_spec_en.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin J.M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.F., Han D.M., Yang J.K. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.HKSAR . 2020. Government Relaxes Social Distancing Measures under Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance.https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202006/16/P2020061600761.htm Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian H., Liu Y., Li Y., Wu C.H., Chen B., Kraemer M.U., Wang B. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6491):638–642. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berk R., MacDonald J.M. Overdispersion and Poisson regression. J. Quant. Criminol. 2008;24(3):269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elwira . 2020. Coronavirus: Latest Social Distancing Rules in Hong Kong. Retrieved from Ref. [1] [Google Scholar]

- 30.HKSAR . 2020. Public Should Properly Maintain Social Distancing at All Times.https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202003/30/P2020033000752.htm Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calle E.E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., Thun M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(17):1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray W.A., Stein C.M., Daugherty J.R., Hall K., Arbogast P.G., Griffin M.R. COX-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of serious coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1071–1073. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greene W.H. Stern School of Business; New York University: 2018. Econometric analysis, 8e. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gujarati D.N. Tata McGraw-Hill Education; 2009. Basic Econometrics. [Google Scholar]