Abstract

This paper explores the use of dance/movement therapy, as a Whole Person approach to working with trauma and building resilience, to effect individual and community change around the world. The arts are a particularly effective way for people who cannot express themselves verbally to find symbolic and embodied expression of their suffering and hopes for the future. Dance/movement therapy can draw on folk dance and specific cultural forms to address universal themes. The content of this paper was presented as a workshop at the American Dance Therapy Association convention in San Diego, 2015.

Introduction: How Does Art Heal?

The arts heal from the basic human need to create, communicate, create coherence, and symbolize. They are symbolic representations of human experience, usually visual, kinesthetic (dance), verbal (poetry), or musical (song, music). They are transcultural, expressing archetypal symbols that are universal throughout history and across cultures. In an age of increased interconnectedness, we are challenged by natural and manmade disasters from around the globe. The clash of cultures brings misunderstandings and conflict. The arts can “help us search again not only for the meaning of life but also the purpose of our individual and collective experience…for ways we might re-create ourselves anew as a human species, so that we may end at last the cycle of violence that has marred our history “(Walsh, 2001, p. 17).

The arts provide symbolic nonverbal ways to work with unspeakable trauma, natural and manmade disasters, dislocation and caregiver burnout. Building on creativity, they facilitate posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996; Serlin & Cannon 2004), growth through adversity (Joseph & Linley, 2008), hardiness (Maddi & Hightower, 1999), optimism and resilience (Antonovsky, 1979; Epel et al, 1998) and self-efficacy. Used to build resiliency in a Whole Person context (Serlin, 2007a, 2010a, b, c), they bring together body, speech, mind and spirit.

The arts heal by improving immune functioning and reducing stress and health complaints, and help people live longer (Pennebaker, 1990). Increasingly, studies have demonstrated the relationship between stress and the body, including the relationship between negative emotions and the fight/flight response, cortisol levels, hypertension and Type A personalities (Babette, 2006; Schore, 1994). Positive emotions also impact wellness including hope, curiosity, and a positive expectation about the future. Finally, stress is not the same for all people, but is individually and subjectively mediated by perceptions, beliefs and cognitions (Serlin, 2006a).

The arts provide access to multiple modes of intelligence (Gardner, 1982), thinking, communicating, and problem solving (Briere & Spinazzola, 2005), connecting us to the imagination (McNiff, 1981), and bridging the conscious and the unconscious. They take us into expanded states of consciousness, helping us understand our waking reality, mindfulness, altered states and dreamtime. And, in many cultures, art takes us into the realm of ritual and the sacred (Graham-Pole, 1997; Marcow Speiser, 1995, 1998; Marcow Speiser and Speiser, 2005, 2007; Serlin, 1993, 1996a, 2012a; Sonke-Henderson, 2007). Facilitating creativity, compassion and connectedness, new contexts and new frames of reference, the arts help each person to discover his or her personal strengths and preferred channel of communication (Carey, 2006; Haen, 2009; Harris, 2007; Levine, 2009; Serlin, 2007b, 2010a).

Stories of death and rebirth descend into sadness and ascend to joy. Disconnection and reconnection are ancient themes reflected in the myths common to all humankind (Serlin, 1993). With the courage to create (May, 1975), new narratives move the self from deconstruction to reconstruction (Feinstein & Krippner, 1988; Gergen, 1991; McAdams et al, 1997; Sarbin, 1986). These healing narratives are experienced as coherent and meaningful and have been gaining attention in many areas of clinical practice, including family therapy (Epston & White, 1992; Howard, 1991; Lieblich & Josselson, 1997; Omer & Alon, 1997; Polkinghorne, 1988). The act of telling stories has always helped humans deal with the threat of nonbeing, and sometimes the expressive act itself has a healing effect (Pennebaker, 1990; Serlin, 2012a, b, c). It expresses not only the individual person, but also the collective unconscious and universal states of the human condition (Jung, 1966).

Art heals by helping us transcend our stuck places and imagine a future or a different situation. The arts are used in rituals around the world for individual and communal healing. Spiritually based rituals have been shown to be effective coping strategies for dealing with life stresses (Pargament, 1997; Marcow Speiser, 1995, 1998) and serious trauma (Frankl, 1959). Art opens doors to the religious and spiritual dimensions of human nature and human fate, which are ultimate questions that are central to an integrative whole person healthcare (Sue, Bingham, Porche-Burke, & Vasquez, 1999).

Art helps us create in the face of these ultimate questions. Rollo May reminds us that the creative act is a courageous affirmation of life in face of the void of death (Maslow, 1962; May, 1975; Serlin & Hansen, 2015). Trauma brings a confrontation with mortality that can lead to the creation of a new identity, sense of meaning, beliefs, existential choice and a renewed will to live (Serlin, 2002; Stolorow, 2007). Through art, through the telling and re-telling of their stories, people can rediscover meaning, gain a sense of efficacy and re-create themselves (Paulson & Krippner, 2007; Yalom, 1980).

From Destruction to Reconstruction: The Path of Resilience

What is resilience? Resilience is the capacity to bounce back after stress and trauma, to rebuild a life even after devastating tragedy. Being resilient doesn’t mean going through life without experiencing stress and pain. Grief, sadness, and pain are natural after adversity and loss (Herman, 1992). The road to resilience lies in working through the emotions and effects of stress and painful events and learning from them. Reflecting on adversity can increase a sense of meaning, purpose and compassion in life. Meeting challenges with creativity can widen horizons and possibilities.

Resiliency includes many dimensions. The arts and narrative methods express and record life stories (Gergen, 1991; May, 1975, 1989; Sarbin, 1986) and facilitate healing (Pennebaker, 1990) within a community of witnesses (Marcow Speiser, 2014). Qualities that build resiliency include optimism, joy and compassion. The use of the arts and particularly dance/movement, builds resilience at the body level.

What brings resiliency? Resiliency grows with enhanced self-management skills and more wisdom. It is helped by supportive relationships with parents, peers and others, as well as through cultural beliefs and spiritual traditions. Developed across the lifespan, resiliency is marked by close relationship with family and friends, a positive view of oneself and confidence in one’s strengths and abilities, the ability to manage strong feelings and impulses, and good problem-solving and communication skills. Additionally, the ability to seek help and find resources, seeing oneself as resilient rather than as a victim, coping with stress in healthy ways and avoiding harmful coping strategies, helping others, and finding positive meaning in life despite difficult or traumatic events is helpful.

Domains of Resiliency

For an online support group used in workshops in Silicon Valley and with youth groups for high school students going into healthcare professions, Dr. Laleh Shahidi, Dan Esbensen and this author developed the following four domains of resiliency as composite descriptions from many definitions of resiliency (www.selfresiliency.com):

Physical

Kinaesthetic intelligence includes the ability to keep one’s balance, to clarify boundaries, to read the messages from one’s body, to take stretch breaks while working, and to be aware of one’s nonverbal communication to others.

Psychological

From a cognitive perspective, resiliency means the ability to see the glass as half full, and to know deeply who one is. From an emotional perspective, it means the ability to support and love oneself, to be able to self-soothe and self-regulate, and to feel and express one’s emotions.

Social

The social domain of resiliency includes the relational ability of forming and sustaining attachments, enjoying satisfying intimate relationships, and creating a healthy support system. Also included are the environmental aspects of respecting and enjoying nature and one’s community.

Meaning and Purpose

The existential aspect of meaning and purpose includes the ability to confront mortality and to live a life of commitment and authenticity. The spiritual aspect can mean having a “calling”, and a sense of meaning and belonging larger than oneself. The transcendent aspect is the ability to feel at home in the universe (Serlin, 2010, summer).

Resilience from a Whole Person Perspective

A Whole Person (Serlin, 2001–2002, 2007a, b, c) perspective on resiliency brings together mind, body and spirit in an integrated healthcare model with a focus on meaning and purpose, wellness, strengths, creativity and humor.

Whole Person Healthcare is built on a new vision of a fully-actualizing person first articulated by Abraham Maslow, former president of APA: “There is now emerging over the horizon a new conception of human sickness and of human health…Perhaps we shall soon be able to use as our guide and model the fully growing and self-fulfilling human being, the one in whom all his potentialities are coming to full development, the one whose inner nature expresses itself freely.” In 2001, the American Psychological Association added “health” to its mission statement, and this author convened a panel at the APA convention on the subject (De Leon et al, 1998). In 2004, she was part of an APA Task Force on Health Care for the Whole Person, and in 2006 part of one from Division 42 of APA. The question of what it means to be human can be understood from the Humanistic Psychology perspective on identity, beliefs, and existential issues; from the creative arts therapy perspective of imagery, art, dance music drama, poetry, and journaling; from a somatic psychology perspective including qigong, tai chi, aikido, Feldenkrais, movement, EMDR, EFT and yoga, and a spiritual perspective that includes meditation, mindfulness awareness, stress reduction and prayer.

A Whole Person psychotherapy embraces diverse approaches that include non-verbal and multi-modal modalities such as expressive therapies and mindfulness meditation (Shapiro & Walsh, 1984), cultural beliefs about living and dying (Sue et al, 1999), opening healthcare to diverse, disabled, and marginalized populations. A Whole Person model offers new ways of cultivating resourcefulness and nurturing a growth mindset.

Whole Person approaches to psychotherapy include: can be grouped into three areas: (1) Meditation or mindfulness (Shapiro & Walsh, 1984); (2) Imagery including guided imagery, KinAesthetic imagery (Serlin, 1996), and verbal imagery (Serlin, Rockefeller & Fox, 2007); (3) Movement including dance movement therapy (Serlin, 2010a, b, c), qigong, yoga, Feldenkrais, Alexander, and somatic therapies.

Movement is a whole person approach that helps clarify and release the stress, countertransference and burnout carried by both caregiver and the person in need of care. The kind of approach used by this author is a process of dance/movement therapy called Kinaesthetic Imagining. Kinaesthetic imagery comes from the Greek word “kinaesthesia” (Gr.), the sensations and expressions arising from bodily movement that become a nonverbal expressive text (Serlin, 1996). By learning to listen to our bodily signals, we can understand better how to care for ourselves and others. Kinaesthetic Imagery has three basic components: Warm-up and check-in, using breath, sound, stretching and circle dance movements to warm up the body and mobilize the healing energies; Body Language includes the development of the themes to explore images and emotions that arise from the movement, individually, in dyads, and in the group so that participants have an opportunity to develop their own personal healing images, stories, and mythologies; and Reflection (Action Hermeneutics) as a time to wind down, internalize the imagery, and reflect on its meaning in order to make a transition into real life.

Posttraumatic Growth

Without a bit of sadness a beautiful samba cannot be made (Vinicius de Morais & Baden Powell)

The concept of resilience is closely tied to a new theory called Posttraumatic growth (PTG) (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006). Instead of focusing on restoring personal and communal functioning to premorbid levels of functioning, as is done in traditional trauma recovery, the theory of posttraumatic growth suggests that from the break-down of trauma can come break-through, and that further growth is possible (Lev-Weisel & Amir, 2006; Rosner & Poswell, 2006).

Reflecting on the fact that posttraumatic growth might seem too positive, Stephen Joseph and Alex Linley from proposed a theory called “Growth Following Adversity” (2008). Proponents of this theory value the learning that comes from adversity and bring this dimension into the therapy.

Both Posttraumatic Growth and Growth following Adversity support an approach that builds resiliency by going through stages of destruction to reconstruction. The arts have an important role to play here as they help people re-imagine and re-energize their lives.

Secondary Trauma

The arts can also play a large role to help with secondary trauma; the trauma that caregivers experience after prolonged exhaustion from caregiving. Caregivers also experience what psychologist Charles Figley called “compassion fatigue” (1995). Even in non-combat situations such as families living with elders who have dementia or Alzheimer’s, these caregivers need help. The arts can facilitate resilience, self-care, care-giver satisfaction and compassion regeneration from a whole person relational and client-centered perspective. This toolkit, that includes mindfulness, imagery and movement, was developed by the author to help caregivers with a form of burnout called “Compassion Fatigue” (Serlin, 2012b) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Compassion fatigue and regeneration

Whole Person Approaches to Trauma and PTSD

Whole Person approaches to working with trauma and building resilience include all dimensions: existential, embodied, creative and mindful. Recent research tells us that trauma is in the body (Levine, 1997; Ogden et al, 2006). Trauma has been called by Bessel Van der Kolk “speechless terror;” therefore, approaches need to utilize nonverbal, symbolic methods (Van der Kolk, 2014; Serlin, 2015). Trauma is a crisis of mortality, meaning and identity; therefore, approaches need to cover existential and spiritual perspectives. Trauma is about “stuckness” and “numbness” and the inability to play; therefore, approaches that are creative, imaginal, moving and emotional are important. Finally, trauma is about fragmentation; therefore, approaches that support connection, integration and transitions can be helpful.

Resilience in Regional Contexts

These tools of arts have been brought into the American Psychological Association to help psychologists develop better self-care. Last year, a collaboration between the San Francisco and the Los Angeles Psychological Association explored the role of the arts in self-care (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Dance therapy, creativity, and self-care workshop

Global Applications of Trauma and Resilience

In Israel, this author did workshops with staff on resiliency and learned from site visits to Natal, Israeli Trauma Center for Victims of Terror and War; SELAH, Israeli Crisis Management Center; the Casualty Division of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), and The Israel Center for the Treatment of Psychotrauma (ICTP). All of these use Whole Person approaches, including the arts and movement (Serlin, 2006b, 2007a, 2014). Pathways to resiliency developed at Selah include control, commitment, challenge, connectedness, courage, compassion, confidence, contribution, and creativity (Pardess, 2004, 2005). Below is a photo of a session at SELAH, a culturally sensitive trauma center that specializes in the needs of Ethiopian and Ukrainian immigrants.

For a workshop with the caregivers (Casualty Division) of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), we worked with young officers whose movements and drawings reflected their level of stress (Fig. 3).

Calm on the outside, chaos inside. When the mess is inside it’s difficult to see

The stresses included losses such as loss of innocence, missing their own beds at home, and loss of what made them feel “human and whole.”

Fig. 3.

Casualty division of the Israeli defense forces

In Natal, the Israel Trauma Center for Victims of Terror and War, we used movement and art to work with staff at the center to help them with burnout (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Natal: training staff

One participant’s drawing was called: The Tree of Life, White Bird. In her description, she said: “I really enjoyed the movement to let go a little, the passing from the floor felt good, the tree turned into a White Bird.”

In 2006, during the war in Lebanon, an extraordinary conference was organized by Lesley University called “Imagine: Expression in the Service of Humanity.” There, Israeli, Palestinian and Bedouin caregivers presented and co-presented their work on the ground caring for the wounded in an intercultural exchange (Serlin & Speiser, 2007) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Imagine: Expression in the service of humanity

We explored the use of movement to amplify dreams as a way to work with trauma. The following words were written by an Israeli student during the 2006 war in Lebanon:

The State of Israel—war in the north—I had a dream; I dreamt I lose all that is nearest to me, Arabs seize my home and take it under their control, into my sister’s kindergarten bursts a strange man who proceeds to pack all the children’s belongings into boxes; in one box he places all the childrens’ handiwork of butterflies.

One small room,

Lots of boxes

One box,

Lots of butterflies

A struggle

The man closes the box

A woman tries to open it

The butterflies in the box struggle to fly and be freed of the box….

One small room…. lots of boxes…

She recited the dream as the class was in a relaxation state, receptive to the images arising from the bodily sensations and the words. As she chanted and walked around the room, the class began to move around her. They draped themselves in fabric, slowly moving around the room, creating a dreamlike atmosphere.

Describing this class, the student wrote:

By means of the movement, by means of my participation in the movement therapy course, I searched for the center part of my body and equilibrium:

within my emotions, movement and thoughts… what is the center of me or

what is the place from which my movements evolve, from where come the

things I say; I felt that words and movements are connected as if they are one; sometimes there was no need for words to understand about others or what I do… Due to its processes we are able to turn our attention to another, to “feel” him, to touch him and enable him to touch us emotionally, spiritually and even physically…The amazing bond was between the personal dream and the group dream, in which each one could be in a place of her choice… It was wonderful how group members supported each other; joining together without words and

I, in the background, used the words as mantra, repeating the words that strengthened the support of the group’s physical movements. ..Upon my observation of the others’ support, I felt I was floating with the mantra that I had created for the group and myself; finally, I too, once a captive within, was freed…I felt that the dream told the story of the little spirits of the entire group and the butterflies in the box desiring to fly to freedom are a metaphor of each

one of the group members’ hurt spirits. This same hurt spirit of each one that desires to be free from its soul and to feel better, happier in life after the burden

is released from its heart. I felt that through the dream and the movement, joint and individual, we had advanced one additional and small step towards our joint task – to reach happiness.

In her paper, the student reflected (Fig. 6):

I understood that this connection probably came from my strong unconscious thought of my connection with the Holocaust and the fear that enveloped me during the period of the war that we experienced recently, if so why a butterfly?

In the Lochamei HaGettaot Memorial Museum, a special building in memory of the million and a half children lost in the Holocaust, was built. Engraved on the metal flooring are the words: “There are no butterflies in the Ghetto”… in the museum you lift up your eyes to see a huge stained glass window illuminated by incoming rays of the sun and it depicts a colored butterfly surrounded by flowers. This expresses the memory of the million and a half little spirits lost in the Holocaust; this picture is deeply engraved within me from my visits to the museum and I continually connect the butterfly with a hurt spirit wanting to be freed. Through the experience of our group process I also succeeded in becoming released from the visions of the little children and their spirits in the Holocaust. When I accompany a group of school pupils to Poland this will surely assist me in dealing with the difficult journey. I understood that in the group we had succeeded in sensing the great curative strength that exists in the connection of body and soul.

The butterfly is trapped behind bars the sun illuminates with hope, this is the hope that I found during the war through the experiencing of realization of a dream by means of movement therapy.

Through the process of KinAesthetic Imagining, this student was able to enact a dream image of grief and loss, use group support to develop its themes and feelings, and discover its meaning for her life.

Fig. 6.

Stained glass window in the roof of the ‘hand-to-hand’ museum, Lochamei HaGettaot

Developing Resilience: Using KinAesthetic Imagining to Explore Lived Experience

Some psychological descriptions of resilience are abstract and don’t convey its lived experience. If we understand the lived experience, perhaps it will be easier to teach skill to develop the capacity for resilience. In classes through Lesley University in Israel, we explored the physicality of resiliency, using rubber bouncing dolls and props, and by sinking down to the floor and rising again in an archetypal pattern of death and rebirth. We experienced the weight of our bodies as we rolled, using the earth for support to rise again. We understood resilience in Laban terms of space, rhythm, and time. We identified four existential elements of regeneration: Death/Rebirth, Down/Up, Dark/Light, and Transitions. Seven elements were related to time: Rhythm, Rest and Renewal, Recuperation, Recovery, Breath and Heartbeat. Eight elements related to space were: In/Out, Big/Small, Boundaries/Borders, Opening/Closing, Yes/No, Here/There, Entrance/Exit, and Coming Home. These elements are related to existential themes of facing mortality, freedom versus constriction, connection and attachment versus disconnection, and meaning expressed as mindful and committed actions in the world (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Developing resiliency

Students co-created final projects based on the existential themes. These themes often brought out deep emotions that were both personal and cultural.

Themes of resilience were similar in other global contexts. For example, in China one group worked with the theme of “Freedom and Fate”. For their project, they staged a re-enactment of Chinese version of Romeo and Juliet. Not only did the music sound different than the traditional Western romantic music, but the ending changed significantly. After both Romeo and Juliet die, they are re-incarnated as butterflies and their whole family flies beautifully away.

In Istanbul, the embodiment of the “Life and Death” theme triggered deep feelings and existential inquiries among group members. Two days after their group performance for the class occurred a tragic event in Turkey, May 13th, 2014: the Soma coalmine disaster where hundreds of workers died. Their class papers wrote about how the “courage to move” could facilitate expression and awareness on a deeper level as a part of the transformation process: “It functions to remind us; keep moving since life is movement and also a never-ending journey of transformation”. One student wrote:

…as I was dancing to the life and death theme, freezing one moment and

moving the other.. I realized that when I freeze, I can see only one part of

the reality, I couldn’t see the people behind or out of my sight zone..it

translates for me, seeing one side of the reality is death!! that death means

all my preconceived ideas, judgments, belief systems, attitudes that inhibit me

to move ahead, make me stuck…as I shared in our small group ‘we can be

dead while we physical are living’ as living deads....

In many ways, their re-enactment of death and rebirth echoed early initiation rituals for women, as expressed in the myth of Inanna’s descent to the underworld, dismemberment and “re”memberment (Perera, 1981).

The death and rebirth theme was also the one chosen by Irmgard Bartenieff when she led a group of us in her first movement choir in the US at the ADTA conference in 1976. It is not only a visual archetype (an image of Inanna going to the underworld), but it is an experiential and existential archetype, in this case expressed in the movements of sinking down and rising up.

Another Turkish student wrote:

I am also so deeply touched and feel sorry and terrified about all happened

in Soma. Not only the disaster or massacre in many ways, but things that happened afterwards have shaken me a lot, as most others would share. Still

I feel the pain for those whose bodies are still locked in that darkness in order

to hide and cover the real scope of the event and the attitude towards the community who are not allowed to grieve and express their feelings … There

is lot to scream. On, death and rebirth theme now, there is so much death

around us…but still need to feel the hope for the rebirth of a new potential life

or era.

In Istanbul, we trained healthcare professionals at Safir Institute, a training program that is now at Mimar Sinan University. Students have begun applying The Art of Embodiment training to work in psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, with breast cancer and hematology units in general hospitals (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Resilience in Istanbul

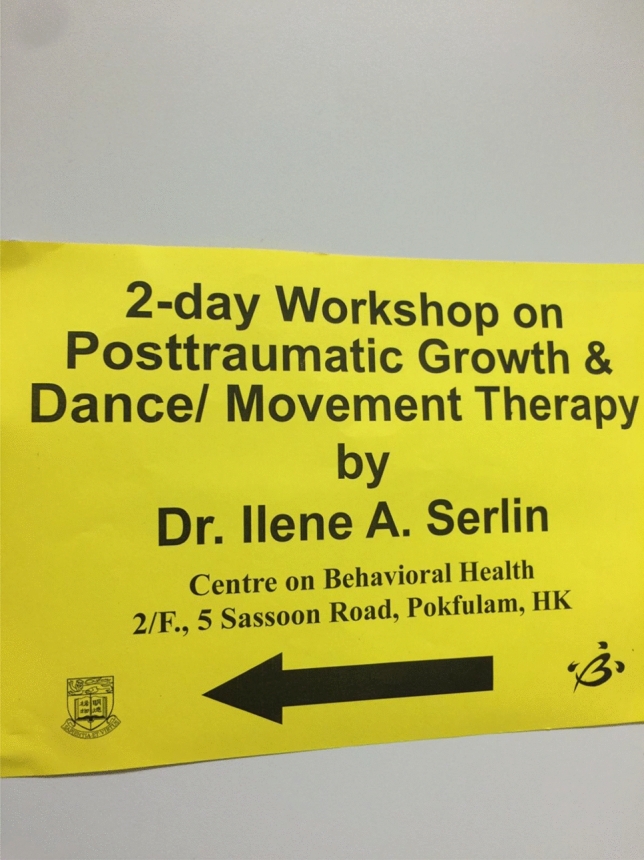

The training in Beijing took place at the China Institute of Psychology, where students are taking the training back to their hometowns. In Hong Kong, the training took place at the University of Hong Kong in a master’s program in Expressive Therapies at the Centre on Behavioural Health. Masters students in the program work with situations of child abuse, domestic violence, and life-threatening illnesses (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Resilience in Hong Kong

The world is increasingly interconnected, and in need of powerful healing responses to trauma and human suffering. Dance Movement Therapy is one trauma approach that can address this suffering. Reaching across cultures, it can be shared in global training settings.

Ilene A. Serlin

Ph.D, BC-DMT is a licensed psychologist and registered dance/movement therapist in practice in San Francisco and Marin county. She is the past president of the San Francisco Psychological Association, a Fellow of the American Psychological Association, past-president of the Division of Humanistic Psychology. Ilene Serlin is Associated Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies, has taught at Saybrook University, Lesley University, UCLA, the NY Gestalt Institute and the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich. She is the editor of Whole Person Healthcare (2007, 3 vol., Praeger), over 100 chapters and articles on body, art and psychotherapy, and is on the editorial boards of PsycCritiques, the American Dance Therapy Journal, the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, Arts & Health: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice, Journal of Applied Arts and Health, and The Humanistic Psychologist. In 2019, she received the Rollo May award from APA’s Society for Humanistic Studies, and the California Psychological Association Distinguished Humanitarian Contribution award.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the author has no conflict of interest

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Antonovsky A. Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Babette, R. (2006). Help for the helper. The psychophysiology of compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma. WWW. Norton.

- Briere J, Spinazzola J. Phenomenology and psychological assessment of complex posttraumatic states. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:401–412. doi: 10.1002/jts.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun L, Tedeschi R. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carey L, editor. Expressive and creative arts therapy methods for trauma survivors. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Leon, P. Newman, R., Serlin, I., & Di Cowden, M. et al. (1998, August). Town Hall, “Integrated Health Care”. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the American Psychological Association 106th Convention, San Francisco, CA.

- Epel ES, McEwan BS, Ickovics SR. Embodying psychological thriving: Physical thriving in response to stress. Journal of Social Issues. 1998;54:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Epston D, White M. Experience, contradiction, narrative and imagination: Selected papers of David Epston & Michael White, 1989-1991. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein D, Krippner S. Personal mythology. Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Figley C. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl V. Man’s search for meaning. New York: Praeger; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H. Art, mind and brain: A cognitive approach to creativity. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen K. The saturated self. New York: Basic Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Pole, J. (1997) Applications of art to health. In Whole Person Healthcare, pp. 1–23.

- Haen, C. (Guest Ed.) (2009, April). The arts in psychotherapy: The creative arts therapies in the treatment of trauma. Vol. 36, No. 2.

- Harris DA. Dance/movement therapy approaches to fostering resilience and recovery among African adolescent torture survivors. Journal on Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and Prevention of Torture. 2007;17(2):134–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Howard G. Culture tales: A narrative approach to thinking, cross-cultural psychology, and psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 1991;46:187–197. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Linley PA, editors. Trauma, recovery and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. On the relation of analytical psychology to poetry. The spirit in man, art and literature. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1966. pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Levine P. Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Trauma, tragedy, therapy: The arts and human suffering. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Weisel R, Amir M. Growing out of ashes: Posttraumatic growth among Holocaust child survivors. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of post-traumatic growth: Research and practice. Taylor and Francis: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 248–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich A, Josselson R, editors. The narrative study of lives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Maddi S, Hightower M. Hardiness and optimism as expressed in coping patterns. Consulting Psychology Journal. 1999;51(2):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Marcow Speiser V. The dance of ritual. Journal of the Creative and Expressive Arts Therapies Exchange. 1995;5:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Marcow Speiser V. The use of ritual in expressive therapy. In: Robbins A, editor. Therapeutic presence: Bridging expression and form. Jessica Kingsley: Bristol, PA; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marcow Speiser V. Working in a troubled land: Using the applied arts towards conflict transformation and community health in Israel. Journal of Applied Arts and Health. 2014;4(3):335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Marcow Speiser V, Speiser P. A theoretical approach to working with conflict through the arts. In: Marcow Speiser V, Powell C, editors. The arts, education and social change. New York: Peter Lang; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marcow Speiser V, Speiser P. An arts approach to working with cross cultural conflicts. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2007;47(1):361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- May R. The courage to create. New York: Bantam Books; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Diamond A, de St. Aubin E, Mansfield E. Stories of commitment: The psychosocial construction of generative lives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:678–694. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff S. The arts and psychotherapy. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden P, Minton K, Pain C. Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Omer H, Alon N. Constructing therapeutic narratives. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pardess, E. (2004). Harnessing the power of metaphors in group-work with bereaved families. Global conference: Making sense of dying and death.

- Pardess E. Training and mobilizing volunteers for emergency response and long-term support. In: Danieli Y, Brom D, Sills J, editors. The trauma of terrorism: Sharing knowledge and shared care—An international handbook. New York: Haworth Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson D, Krippner S. Haunted by combat. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Opening up: The healing power of expressing emotions. New York: The Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Perera SB. Descent to the goddess: A way of initiation for women. Toronto: Inner City Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne DE. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R, Poswell S. Posttraumatic growth after war. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of post-traumatic growth: Research and practice. Taylor and Francis: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 197–240. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbin T, editor. Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct. New York: Praeger; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN. Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development. Mahweh, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. A. (1993, Fall/Winter). Root images of healing in dance therapy. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 15(2), 65–76.

- Serlin IA. Body as text: A psychological and cultural reading. The Arts in Psychotherapy, Special Edition. 1996;23(2):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. A. (2002, September). Psychologists working with trauma: A humanistic approach. APA Monitor, 33(8), 40.

- Serlin IA. Psychological effects of the virtual media coverage of the Iraq war: A postmodern humanistic perspective. In: Kimmel P, Stout C, editors. Collateral damage: How the US war on terrorism is harming American mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin IA. Action stories. In: Krippner S, Bova M, Gray L, editors. Healing stories: The use of narrative in counseling and psychotherapy. Charlottesville, VA: Puente Publications; 2007. pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin IA. Whole person healthcare. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. A. (2007b). Arts therapies and trauma: An emerging field. In (Review of the book Expressive and Creative Arts Methods for Trauma Survivors, edited by Lois Carey). PsycCritriques-Contemporary Psychology: APA Review of Books, vol. 52 (33).

- Serlin IA. Dance/movement therapy. In: Weiner IB, Craighead WE, editors. Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. 4. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. pp. 459–460. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. (2010a). Trauma and the arts [Review of the book Trauma, tragedy, therapy: The arts and human suffering]. PsycCRITIQUES, 55, (21).

- Serlin, I. A. (2010, Summer) The first international conference on existential psychology: An intellectual dialogue between east and west: How to face suffering and create a life of value. The San Francisco Psychologist, 6, 18.

- Serlin IA. Literary expressions of trauma. In: Figley C, editor. Encyclopedia of trauma: An interdisciplinary guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. pp. 352–354. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. A. (2012a) The courage to move. In S. Schwartz, V. Marcow Speiser, P. Speiser, & M. Kossak (Eds.), Art and social change: The Lesley University experience in Israel. The Arts Institute Project in Israel Press and the Academic College of Social Sciences and the Arts Press. Netanya: Israel, pp. 117–124.

- Serlin IA. Compassion fatigue and regeneration: Whole person tool kits. San Francisco, CA: Union Street Health Associates; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin IA. Kinaesthetic Imagining. In: Thompson B, Neimeyer R, editors. Grief and the expressive therapies: Practices for creating meaning. New York: Routledge; 2014. pp. 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. A. (2015, June 15). Dance, creative arts, and somatic therapies in the healing of trauma. Review of B. Van der Kolk, The body keeps the score: Brain, mind and body in the healing of trauma. PsycCritiques, Vol. 60, No. 24 (pp. 1–6). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association..

- Serlin IA, Cannon J. A humanistic approach to the psychology of trauma. In: Knafo D, editor. Living with terror, working with trauma: A clinician’s handbook. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin IA, Hansen E. Stanley Krippner: Advocate for healing trauma. In: Davis JA, Pitchford DB, editors. Stanley Krippner: A life of dreams, myths, and visions. Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, I. A. (Spring, 1996). Kinaesthetic Imagining. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 36(2), 25–33.

- Serlin, I.A. (Fall/Winter, 2001–2002). Year of the whole person. Somatics. 4–7.

- Serlin, I.A. (September 2006). The use of the arts to work with Trauma in Israel. The San Francisco Psychologist. 8–9.

- Serlin, I., Rockefeller, K. & Fox, J. (2007). Multi-modal imagery and healthcare. In I. Serlin, (Gen. Ed.) Whole person healthcare, pp. 63–83.

- Serlin I, Speiser V. Imagine: Expression in the service of humanity. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2007;47(3):278–279. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D, Walsh R, editors. Meditation: Classic and contemporary perspectives. New York: Aldine; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sonke-Henderson, J. (2007). History of the arts and health across cultures. In Whole Person Healthcare, 23–43.

- Stolorow R. Trauma and human existence. New York: The Analytic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Bingham RP, Porche-Burke L, Vasquez M. The diversification of psychology: A multicultural revolution. American Psychologist. 1999;54(12):1061–1069. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.54.12.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk B. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, N.D. (2001) What is the proper response to hatred and violence? In From the ashes: A spiritual response to the attack on America. New York: St Martin’s Rodale and Beliefnet.

- Yalom ID. Existential psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]