Abstract

The present study examined the effects of dexmedetomidine (Dex) on cognitive and motor recovery in mice following traumatic brain injury (TBI). TBI induces synaptic damage, which leads to motor dysfunction and cognitive decline. Although Dex is known to induce neuroprotection, its role following TBI remains unknown. In the present study, male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old; n=72) were subjected to cortical impact injury to generate a TBI mice model. Mice were divided into four groups: TBI, sham, TBI + vehicle, and TBI + Dex. Mice in the TBI + vehicle and TBI + Dex groups received intraperitoneal injections of saline (n=18) and 100 µg/kg Dex (n=18), respectively, at 1 and 12 h following surgery. At 24 h post-injury, 10 animals from each group were sacrificed, and brain tissue was isolated for Fluoro-Jade B staining and RNA and protein extraction. At 72 h post-TBI, motor function was evaluated. Furthermore, cognitive impairment was assessed between day 14 and 19 using the Morris water maze. The results demonstrated that the mRNA and protein expression of post-synaptic density 95 (PSD95) was reduced post-TBI. In addition, neuronal degeneration was evaluated using FJB staining, where PSD95 formed a complex with the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor subunit (NR2B) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) inducing neuronal death post-TBI. Treatment with Dex efficiently decreased the PSD95-NR2B-nNOS interaction, which reduced the TBI-induced neuronal death. Furthermore, Dex treatment contributed to the enhanced cognitive and motor recovery following TBI. The results from the present study reported a potential mechanistic action of Dex treatment post-TBI, which may be associated with the inhibition of PSD95-NMDA interaction.

Keywords: dexmedetomidine, post-synaptic density 95, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has deleterious effects on public health and is associated with high mortality and morbidity rates worldwide, with an incidence of 69 million individuals suffering from TBI each year (1,2). Global mortality rate has been recorded to be 30-40% in severely affected patients with TBI (2). Patients who survive TBI commonly suffer from physical and cognitive disabilities that increase their susceptibility to other neurological disorders (3). In addition to primary mechanical damage, TBI activates a cascade of pathophysiological mechanisms leading to secondary brain injury (4,5). The secondary effects include glutamate excitotoxicity, free radical production, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of ATP, inflammation and ultimately neuronal death (4-7). TBI evolves within weeks to months, and can induce behavioural perturbations (8). It is therefore crucial to develop novel strategies to treat multifaceted and complex pathophysiological mechanisms associated with TBI.

TBI induces synaptic damage that results in neuronal dysfunction and subsequent neuronal apoptosis (9,10). Synaptic structure and function serve a crucial role in brain development and cognitive functions. Under normal conditions, the synaptic vesicle in neurons fuses with the plasma membrane and releases neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft (11). It is therefore essential to determine the neurological synaptic molecules that may be released following TBI. At present, >5,000 synaptic proteins have been identified; however, only a few are associated with synaptic dysfunction post-TBI (10). The postsynaptic compartment of excitatory synapses contains an electron-dense region known as the postsynaptic density (PSD). The postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD95) of the PSD family acts as a scaffolding protein during synaptogenesis and regulates synaptic maturation (12). In addition, PSD95 serves a vital role in repairing injuries affecting the PSD region, since it is essentiel for synaptic integration and functional recovery following neuronal damage (13,14). PSD95 interacts with the N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor subunit (NR2B) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) to modulate glutamate transmission and maintain excitatory synapse balance (10).

The present study hypothesized that pharmacologically targeting the PSD95-NMDA interaction may provide novel insight into neuroprotective strategies post-TBI. Numerous neuroprotective agents against TBI have been identified; however these agents have rarely been successful during clinical trials. Dexmedetomidine (Dex), which is an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist drug, has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is known for its anaesthetic, analgesic and neuroprotective effects (15). Dex also exerts a positive impact on neuronal development by regulating PSD95expression (16); however, the role of Dex in post-TBI neuroprotection remains unknown. The present study investigated the effect of Dex on the PSD95-NMDA interaction and subsequent functional recovery post-TBI.

Materials and methods

Animals and TBI induction

Male C57 BL/6 mice (8 weeks old; n=72) were obtained from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center. All procedures were approved by the Research Review and Ethics Board (RREB) of the Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital and was performed according to the guidelines from the National Research Council Guide. Mice (n=72) were subjected to controlled cortical impact injury (CCI) (that is representative of TBI induction) as previously described (17). Prior to surgery, anesthetized mice (3% isoflurane) were placed in a stereotaxic frame. The skin was removed to expose the skull, and a 4-mm craniotomy was performed between the lambda and bregma sutures under sterile procedure. The skullcap was removed carefully without damaging the dura underneath. A pneumatic impactor was used to control the contact velocity and the level of cortical deformation, which determined the severity of the injury. The contact velocity and degree of deformation were set at 3.5 m/sec and 0.5 mm, respectively. These settings provided an injury of moderate severity. Immediately after the injury, the skin incision was sutured. Sham animals (n=18) were not subjected to CCI injury; however craniotomy was performed on them.

Drug administration

Following surgery, mice were divided into different groups: TBI, TBI+vehicle, TBI+Dex and sham (n=18 in each group). Mice in TBI+vehicle and TBI+Dex groups received intraperitoneal injections of saline (n=18) and Dex 100 µg/kg (18) (n=18; Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA), respectively, at 1 h and 12 h following surgery. At 24 h post-injury, 10 animals out of 18 in each group were sacrificed [according to ARRIVE and 2013 AVMA euthanasia guidelines (19,20)] to isolate brain tissue for Fluoro-Jade B (FJB) staining and RNA and protein extraction.

For the neurobehavioral tests involving motor and cognitive function, TBI mice were placed in two groups (the remaining n=8 in each group) and were injected with saline or Dex intraperitoneally as aforementioned. The motor function was assessed over the course of five days post-TBI and cognitive function was evaluated from days 14 to 19. The sham surgery mice (n=8) served as the control.

Histological analysis

Mice were sacrificed using the anesthetic agent Avertin (400 mg/kg of body weight) administered intraperitoneally and were transcardially perfused with cold saline and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Subsequently, brains were removed, fixed with 4% PFA overnight at 4˚C and kept in 30% sucrose for 48 h at 4˚C. Brain sections (30 µm) were cut using a cryostat for histological analysis and stored at -80˚C, whereas brain samples were cut and dissected using a brain chisel, and mechanically lysed in the ice-cold lysis buffer containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for western blot analysis.

FJB staining

FJB stain is a fluorochrome that is commonly used to label degenerating neurons. The isolated frozen sections that were obtained after histological processing were mounted on Superfrost plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Slides were rinsed in water and transferred into 0.06% potassium permanganate solution for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Sections were washed with double-distilled water and incubated with 0.0004% FJB solution (Merck KGaA) containing 0.1% DAPI for 20 min at RT. Slides were washed with dd water, air-dried thoroughly until completely dry and visualised under a fluorescence microscope (490/525 wavelength; magnification, x20).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the excised tissue using RNA isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the purity was tested using Nanodrop1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). According to the manufacturer's instructions, RT-qPCR was performed to detect the mRNA expression level using SyBr Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). qPCR (Applied Biosystem) was performed (95˚C initial template denaturation, and 40 cycles of 95˚C denaturation and 60˚C anneal/extension) to assess the relative mRNA expression level of PSD95 following TBI. PSD95 relative expressions level was normalized to the endogenous control GAPDH and was expressed as 2-ΔΔCq (21). The sequences of primers used are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Primer sequences for RT-PCR reaction.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| PSD95 | 5'-TCTGTGCGAGAGGTAGCAGA-3' | 5'-AAGCACTCCGTGAACTCCTG-3' |

| GAPDH | 5'-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3' | 5'-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3' |

PSD95, postsynaptic density protein 95.

Western blotting

Brain samples were cut and dissected using a brain chisel, and mechanically lysed in the ice-cold lysis buffer containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Proteins (20 µg) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked using 5% skimmed milk dissolved in PBS for 1 h at RT and incubated with the primary antibodies. Primary antibodies used were as follows: Rabbit polyclonal anti-PSD95 (Abcam; cat. no. ab18258, 1:1,000), rabbit monoclonal anti-nNOS (Abcam; cat. no. ab76067; 1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal anti-NR2B (Abcam; cat. no. ab65783; 1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal anti-MMP2 (Abcam; cat. no. ab97779; 1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal anti-MMP9 (Abcam; cat. no. ab38898; 1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal caspase-3 (Abcam; cat. no. ab13847; 1:1,000) and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (Abcam; cat. no. ab8245; 1:500) overnight at 4˚C. Membranes were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween and incubated with horeradish peroxidase goat anti-rabbit (Abcam; cat. no. ab7090; 1:1,000) or anti-mouse immunoglubulin G secondary antibodies (Abcam; cat. no. ab150117. 1:1,000) for 2 h at room temperature. Bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Relative expression of proteins was normalized to GAPDH endogenous control using Image J software version 1.50 (National Institute of Health).

Immunoprecipitation analysis

Brain samples were lysed using ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The lysate was incubated overnight at 4˚C with protein-specific antibodies for proteins PSD95, nNOS, NR2B or rabbit IgG (Abcam; cat. no. ab7090), which served as the negative control. Protein A/G Sepharose beads (Abcam; cat. no. ab193262; 2 µl/µg of total protein) were added to each immune complex. The mixture was kept for 4 h at 4˚C with rotational shaking. The beads were washed three times with RIPA lysis buffer. Furthermore, the lysate bead mixture was eluted by heating the samples in 4X SDS loading buffer for 10 min at 50˚C. Protein bands were detected using western blot analysis following the aforementioned protocol.

Motor function

Motor performance was evaluated using beam-balance and beam-walk tests (22,23). For the beam balance test, mice were placed on 1.5 cm wide elevated narrow beam-balance and the time each mouse remained on beam was recorded. A maximum of 60 sec was allowed (22). For the beam-walk test, the time needed to traverse the 2.5 cm width and 100 cm length beam was recorded (23). A pre-assessment test was performed prior to the surgery to obtain a baseline. Each experiment consisted of three trials per day with 60 sec of maximum allotted time for each task. The average daily scores were analyzed.

Cognitive function

The cognitive function was assessed using the Morris Water Maze test (24). A plastic pool of 180 cm diameter and 60 cm height constituted the maze. The pool was filled with water (temperature 26±1˚C, 28 cm depth) and was placed in a space with prominent visual cues. A clear Plexiglas stand of 10 cm diameter and 26 cm height was kept in the southwest quadrant of the maze 26 cm was away from the wall of the maze. This position of the platform was held constant for each mouse. To evaluate the spatial learning, the mice were given four trials with 4 min inter-trial interval for 5 days from days 14 to 19 following surgery. A maximum of 120 sec was permitted for the mice to find the platform that was hidden at 2 cm under the water surface. At day 19 post-surgery, the platform was kept 2 cm over the water surface so it was visible to mice. This test provided information on the effect of non-spatial factors, including sensorimotor performance, visual acuity and motivation on cognitive function. Every trial continued until the mice successfully climbed onto the platform or the allowed threshold time of 120 sec had passed. If the platform remained unfound in the given time, mice were manually directed towards it. Mice were returned to a heated incubator between each trial after 30 sec spent on the platform. The time recorder for each trial during one day was averaged and statistically analyzed. Spontaneous motor activity recording and tracking system (SMART 2.0 tracking software; Panlab) was used to record the time needed for the mice to locate the platform.

Statistical analysis

Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. One way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test was used for the comparison of variables using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

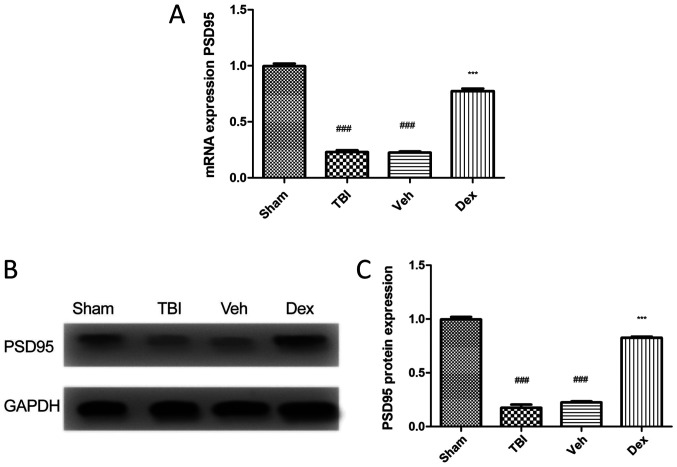

PSD95 expression is reduced in mice following TBI

To evaluate the expression of PSD95 following TBI, RT-qPCR and western blotting were performed. The results demonstrated that PSD95 expression level was significantly decreased in mice following TBI compared with mice in the sham group (0.7705 fold decrease; P<0.001; Fig. 1A). This result was supported by the reduced protein expression of PSD95 in mice following TBI compared with mice in the sham group (0.8205 fold decrease; P<0.001; Fig. 1B and C). Conversely, treatment with Dex following TBI induced an increased PSD95 expression at mRNA (0.5505-fold increase; P<0.001 vs. vehicle; Fig. 1A) and protein (0.6005 fold increase; P<0.001 vs. vehicle; Fig. 1C) levels.

Figure 1.

PSD95 expression of in mice treated with following TBI. (A) PSD95 expression level in the four groups. TBI induced a significantly reduced PSD95 expression level compared with sham group. Dex treatment significantly increased PSD95 expression level compared with Veh group. (B) Western blotting confirmed the increased PSD95 expression in mice treated with Dex following TBI. (C) PSD95 protein quantification. Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. ###P<0.001 vs. sham and ***P<0.001 vs. Veh. Dex, dexmedetomidine; PSD95, post-synaptic density 95; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

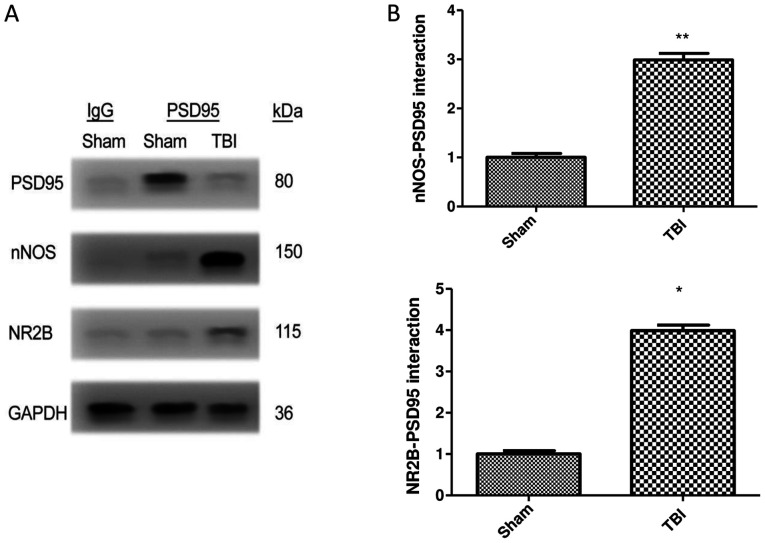

TBI increases the interaction of PSD95 with NR2B and nNOS

The interaction of PSD95 with NR2B and nNOS was examined by co-immunoprecipitation in brain samples of mice following TBI. The results demonstrated that the generation of PSD95-NR2B-nNOS complex was significantly increased in the TBI group compared with the sham group. Furthermore, there was a 1.99 and 2.98 fold increase in nNOS and NR2B interaction, respectively, with PSD95 in the TBI group compared with the sham group (P<0.01 vs. sham). TBI therefore increased the expression of NR2B and nNOS when co-immunoprecipitated with PSD95 (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Co-immunoprecipitation of nNOS and NR2B with PSD95. (A) Western blotting of samples following immunoprecipitation demonstrated the PSD95 interaction PSD95 with nNOS and NR2B. (B) Relative levels of nNOS and NR2B immunoprecipitated with PSD95 and normalized to the sham group. Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. **P<0.01 and *P<0.05 vs. sham group. Dex, dexmedetomidine; IgG, immunoglobulin G; kD, kilodalton; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; NR2B, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor subunit; PSD95, post-synaptic density 95; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

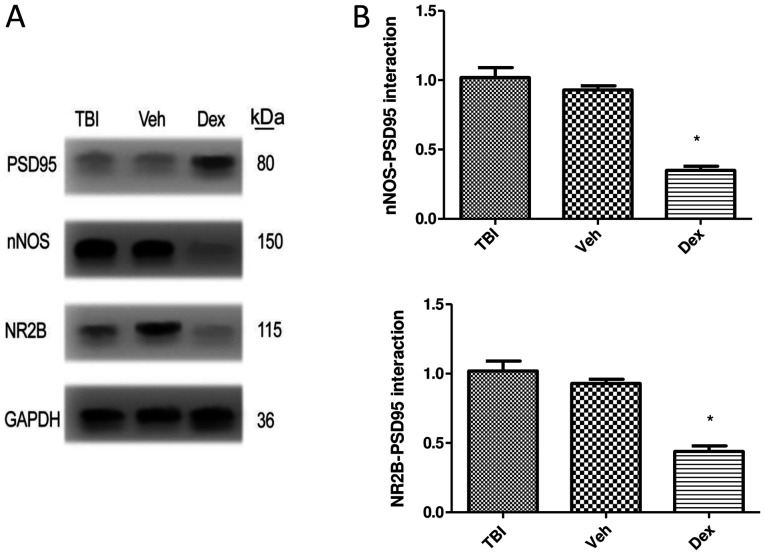

Dex treatment alleviates PSD95-NR2B-nNOS complex generation following TBI

The formation of the PSD95-NR2B-nNOS complex following Dex treatment was assessed by co-immunoprecipitation. The results demonstrated that Dex treatment prevented the interaction of PSD95 with NR2B-nNOS following TBI. The expression of NR2B (0.58-fold decrease; P<0.05 vs. vehicle) and nNOS (0.67-fold decrease; P<0.05 vs. vehicle) was significantly reduced when co-immunoprecipitated with PSD95 following Dex treatment compared with vehicle group (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

PSD95 interaction with NR2B and nNOS following Dex treatment. (A) Dex treatment reduced PSD95 interaction with NR2B and nNOS as presented by immunoprecipitation assay. (B) Relative levels of nNOS and NR2B immunoprecipitated with PSD95 and normalized to the Veh group. Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05 vs. Veh. Dex, dexmedetomidine; IgG, immunoglobulin G; kD, kilodalton; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; NR2B, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor subunit; PSD95, post-synaptic density 95; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

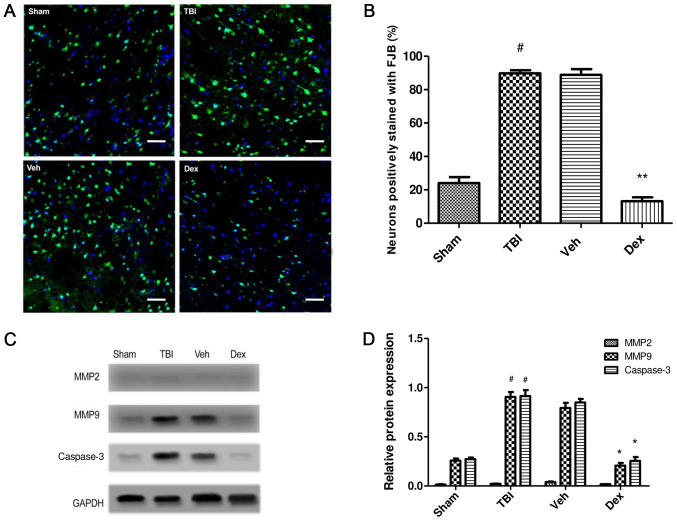

Effect of Dex treatment on TBI-induced secondary brain injury

To study the effect of Dex administration on secondary brain injury following TBI, FJB staining was performed at 24 h post-TBI. FJB staining was conducted to evaluate the effect of Dex on neuronal degeneration post-TBI. The results demonstrated that number of cells stained with FJB was increased in the TBI group (65.75% increase; P<0.001 vs. sham) implying increased neuronal degeneration, whereas the number of FJB-positive cells was reduced following Dex treatment compared with the vehicle group (75.7% decrease; P<0.001 vs. vehicle; Fig. 4A and B). To further study the effect of Dex on neuronal death following TBI, the expression of caspase-3 in the brain tissue near the injury was detected by western blotting. The results indicated that Dex treatment inhibited neuronal apoptosis post-TBI (0.594 fold decrease; P<0.05 vs. vehicle; Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4.

Effect of Dex on secondary brain injury leading to neuronal death. (A) FJB staining in TBI, sham, Veh and Dex groups. Magnification, x20, Scale bar= 20 µm. (B) Quantification of FJB staining. The positively stained cells in each group were counted, normalized to the total number of cells (stained by DAPI) and expressed as percentage in the examined area. (C) MMP2, MMP9 and Casp3 expression assessed by western blotting in TBI, sham, Veh and Dex groups. (D) Quantification of protein expression. Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. #P<0.05 vs. sham. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. Veh. Casp3, caspase 3; Dex, dexmedetomidine; FJB, Fluoro-Jade B; MMP2, matrix metalloproteinase 2; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

The effect of Dex treatment on protein expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2 and MMP9 following TBI was also evaluated. The results demonstrated that MMP9 expression was significantly increased at 24 h post-TBI (0.672-fold increase; P<0.05 vs. sham) but was significantly decreased following Dex treatment (0.586-fold decrease; P<0.05 vs. vehicle). No change in MMP2 expression was observed following TBI and Dex treatment (P>0.05). These findings demonstrated that Dex administration efficiently reduced the TBI-induced activation of MMP9, which may be consecutive to the inhibition of PSD95-NMDA complex formation (Fig. 4C and D).

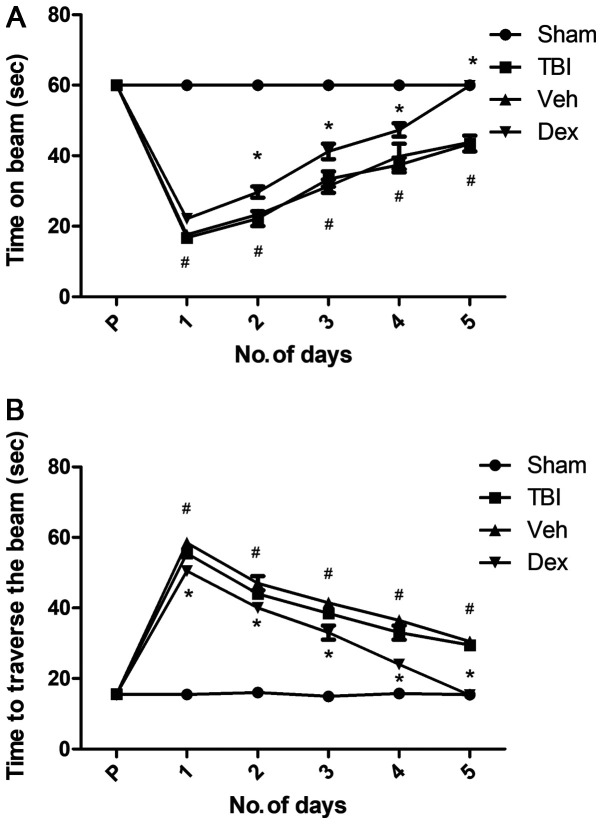

Dex treatment improves motor function

The motor function of mice following TBI was evaluated using the beam balance and beam walk tests. Following surgery, mice were tested twice daily for 5 days. Prior to surgery, mice motor performance, which corresponds to the duration spent on the beam and the distance traversed was recorded and served as a baseline. The results demonstrated that mice in each group were capable of balancing on the beam for 60 sec for three trials and presented no pre-surgical variance among groups. Following TBI, all injured mice exhibited significantly impaired balance compared with sham mice (P<0.05 vs. sham; Fig. 5A), whereas Dex-treated mice presented improved balance (P<0.05 vs. vehicle; Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Effect of Dex on motor recovery evaluated by beam balance and beam walking tests (A) Time required by mice to balance on an elevated narrow beam in TBI, sham, Veh and Dex groups. (B) Time taken to traverse the beam in TBI, sham, Veh and Dex groups. Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. #P<0.05 vs. sham and *P<0.05 vs. Veh. Dex, dexmedetomidine; No, number; s, seconds; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

Following TBI, there was a significant increase in the time needed for mice to traverse the beam compared with the sham group (55.5 sec on day 1 post-TBI; P<0.05 vs. sham; Fig. 5B). Furthermore, a dramatic decrease in the time needed for mice to traverse the beam was observed in the vehicle group at five days following TBI (29.5 sec on day 5 post-TBI; P<0.05 vs. sham; Fig. 5B). This result could be due to to the skill acquired by the mice during the test. However, Dex treatment facilitated a rapid recovery, and on day 5, Dex-treated mice needed a minimum time to traverse the beam (15.3 sec; P<0.05 vs. vehicle; Fig. 5B). This result suggested that Dex treatment may improve motor function recovery in mice following TBI.

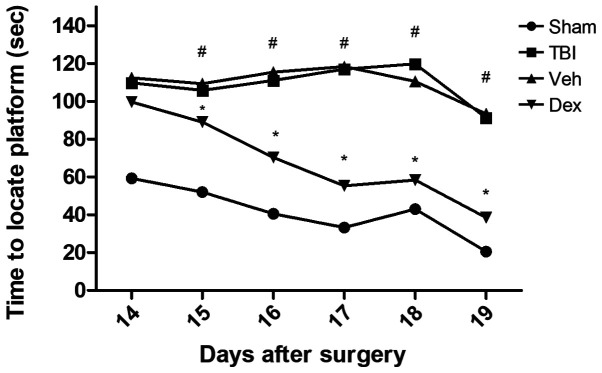

Dex treatment rescues cognitive impairment caused by TBI

The Morris Water Maze was used to assess cognitive impairment of mice following TBI and to determine the effect of Dex treatment on mice 14-19 days after TBI (Fig. 6). The results demonstrated that TBI group requested longer time to find the hidden platform (110.1 sec on day 14 post-TBI; P<0.05 vs. sham), which was close to the threshold of 120 sec allowed for each animal. However, Dex treatment significantly reduced the amount of time needed to mice to find the underwater platform compared with the vehicle group (98.3 sec on day 14 post-TBI; P<0.05 vs. vehicle; Fig. 6). In addition, when the platform was elevated on day 19 so that it was visible to mice, the time needed to find the platform was reduced in all groups. However, mice that were treated with Dex exhibited a greater cognitive recovery compared with mice in the vehicle group (38.5 sec on day 19 post-TBI; P<0.05 vs. vehicle; Fig. 6). These results suggested that Dex treatment may serve a crucial role in the cognitive recovery following TBI.

Figure 6.

Effect of Dex on cognitive recovery following TBI evaluated by Morris water maze test analysis. The test was assessed from days 14 to 19 following TBI. Time required by mice to locate the platform hidden/visible on the water surface was recorded. Mice treated with Dex needed significantly less time to locate the platform. Data were represented as the means ± standard error of the mean. #P<0.05 vs. sham and *P<0.05 vs. Veh. D, days; Dex, dexmedetomidine; s, seconds; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

Discussion

The present study examined the underlying mechanism of Dex on the PSD95-NMDA receptor interaction to promote functional recovery in mice following TBI. The results demonstrated that Dex treatment reduced the PSD95-NR2B-nNOS complex formation, which subsequently improved the motor and cognitive function in mice following TBI.

TBI can induce secondary brain damage, initiating a cascade of pathophysiological events leading to motor dysfunction and cognitive decline (1,2); however, no effective treatment for the multifaceted and complex disorders associated with TBI is available. One of the most preferred clinical approaches to treat severe TBI is to control intracranial pressure through pharmacologic sedation (25). The sedative agents used on patients following TBI should have a rapid effect with a short elimination half-time and no adverse effects on other organ systems (25,26). The commonly used sedative agents, including propofol and benzodiazepines, are associated with respiratory depression and hypotension, which interfere with neurological evaluations (26). Conversely, Dex is an alpha-2 receptor adrenergic agonist FDA approved, with an elimination half-time of ~2 h, which is acceptable in humans (27); however, the underlying mechanisms of Dex treatment following TBI has not been thoroughly investigated. The present study investigated the molecular mechanism by which Dex may allow cognitive and motor recovery following TBI.

Functional recovery following TBI largely depends on brain plasticity, which is determined by the synapse number and the enhanced function of synapses in the neurons. Improved synaptic function inhibits neuronal apoptosis, which enhances the action of peripheral neurons following TBI (10). Numerous studies have targeted the postsynaptic membrane-associated proteins for the treatment of neurological disorders. For example, PSD95 is abundantly expressed in excitatory neurons and is connected with the activation of the NMDA receptor with nitric oxide (NO)-mediated neurotoxicity (11-13). Following TBI, NMDA excitatory potential in the neurons is reduced and attenuates glutamate-induced excitatory currents (10).

The results from the present study demonstrated that PSD95 expression was reduced following TBI, and that the formation of PSD95-NMDA complex was increased post-TBI. It has been demonstrated that excessive generation of the PSD95-NMDA complex can stimulate NO production and activate MMP9, which can induce neuronal apoptosis (28). The present study reported that Dex treatment could decrease the PSD95-NMDA interaction and consequently reduce neuronal death caused by TBI. It was also demonstrated that Dex treatment contributed to the cognitive and motor recovery enhancement following TBI.

Previous findings have shown Dex to be a safe and effective treatment in neurosurgical patients. For example, post-surgical treatment with Dex can improve neurological scores and reduces brain oedema following sub-arachnoid haemorrhage (29). Furthermore, Dex exerts a neuroprotective effect against TBI through the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathway (30). In addition, Dex was demonstrated to be neuroprotective in hippocampal slice cultures (31,32), and a recent report substantiated neuroprotective property of Dex in an in vivo model of TBI (18). An extensive review has discussed that alpha 2-adrenergic agonists are neuroprotective agents (33). These agents can reduce the release of excitatory neurotransmitters at the supracellular level and inhibit adenylate and guanylate cyclases at the cellular level (33). The modulation of NMDA receptor function via alpha 2-adrenergic agonists is a vital mechanism in neuroprotection (34). In the present study, the regulation of PSD95-NMDA interaction by Dex may be attributed to its agonistic effect on the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor.

Following TBI, post-synaptic glutamate receptors are activated, inducing an increased release of glutamate and reduced glutamate intake. Following glutamate stimulation, NMDA receptors impose a toxic effect through PSD95. PSD95 anchors the NMDA receptor and stimulates the migration of downstream signalling molecules towards the calcium channel of the NMDA receptor. Intracellular calcium excess can lead to oxidative stress by generating large amounts of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. The subsequent release of inflammatory cytokines and caspase-3 cascade activation lead therefore to neuronal apoptosis (35). Dex treatment could inhibit the activation of MMP9 and caspase-3 and therefore reduce the neuronal excitotoxicity.

The present study demonstrated that Dex administration following TBI reduced cognitive impairment. Previous studies reported that cognitive recovery depends on the interaction between synapses (36-38). Following the initial trauma, the loss of PSD95 is directly associated with cognitive decline that is observed within weeks to months (39). Another study reported that activation of the protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase following TBI causes memory impairment through PDS95 and cAMP response element binding protein downregulation (40). Furthermore, post-traumatic hypothermia increases PSD95 expression to restore learning and memory function (41). PSD95 is therefore considered as an important therapeutic target that promotes cognitive and motor recovery after TBI-induced secondary brain damage.

In conclusion, the present study described a potential mechanism of action of Dex treatment in mice following TBI. Dex treatment reduced neuronal death as well as promoted motor and cognitive recovery. Furthermore, improvement of cognitive and motor function post-TBI in mice treated with Dex may be attributed to the inhibition of PSD95-NMDA receptor activation. The regulation of PSD95-NMDA receptor complex may largely contribute to synaptic plasticity and learning abilities following brain injury. In addition, the present study demonstrated that Dex treatment inhibited PSD95 interaction with NR2B and nNOS, which resulted in cognitive and motor recovery following TBI. The long-term effect of Dex treatment and other associated molecular targets on functional recovery following TBI will be further investigated.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

ZZ and YH conceptualised and designed the experiments, ZZ performed the experiments, YR and HJ performed the statistical analysis and provided assistance for the current study. ZZ and YH drafted the manuscript. YH revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version to be submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the experiments were ethically approved and performed according to the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, ARRIVE guidelines (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arrive-guidelines) and the AVMA euthanasia guidelines 2013.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018;1:1–18. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blennow K, Brody DL, Kochanek PM, Levin H, McKee A, Ribbers GM, Yaffe K, Zetterberg H. Traumatic brain injuries. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(16084) doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stocchetti N, Zanier ER. Chronic impact of traumatic brain injury on outcome and quality of life: A narrative review. Crit Care. 2016;20(148) doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1318-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheriff FG, Hinson HE. Pathophysiology and clinical management of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in the ICU. Semin Neurol. 2015;35:42–49. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph B, Haider A, Rhee P. Traumatic brain injury advancements. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015;21:506–511. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corps KN, Roth TL, McGavern DB. Inflammation and neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:355–362. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Rodríguez A, Egea-Guerrero JJ, Murillo-Cabezas F, Carrillo-Vico A. Oxidative stress in traumatic brain injury. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:1201–1211. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666131217153310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mckee AC, Daneshvar DH. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;127:45–66. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52892-6.00004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama K, Kiyosue K, Taguchi T. Diminished neuronal activity increases neuron-neuron connectivity underlying silent synapse formation and the rapid conversion of silent to functional synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4040–4051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4115-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merlo L, Cimino F, Angileri FF, La Torre D, Conti A, Cardali SM, Saija A, Germanò A. Alteration in synaptic junction proteins following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:1375–1385. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travaglia A, Bisaz R, Cruz E, Alberini CM. Developmental changes in plasticity, synaptic, glia and connectivity protein levels in rat dorsal hippocampus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;135:125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keith D, El-Husseini A. Excitation control: Balancing PSD-95 function at the synapse. Front Mol Neurosci. 2008;1(4) doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.004.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christopherson KS, Hillier BJ, Lim WA, Bredt DS. PSD-95 assembles a ternary complex with the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor and a bivalent neuronal NO synthase PDZ domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27467–27473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mo SF, Liao GY, Yang J, Wang MY, Hu Y, Lian GN, Kong LD, Zhao Y. Protection of neuronal cells from excitotoxicity by disrupting nNOS-PSD95 interaction with a small molecule SCR-4026. Brain Res. 2016;1648:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahmani S, Rouelle D, Gressens P, Mantz J. Characterization of the postconditioning effect of dexmedetomidine in mouse organotypic hippocampal slice cultures exposed to oxygen and glucose deprivation. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:373–383. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ca6982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv J, Ou W, Zou XH, Yao Y, Wu JL. Effect of dexmedetomidine on hippocampal neuron development and BDNF-TrkB signal expression in neonatal rats. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:3153–3159. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S120078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao X, Deng-Bryant Y, Cho W, Carrico KM, Hall ED, Chen J. Selective death of newborn neurons in hippocampal dentate gyrus following moderate experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2258–2270. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Vogel T, Gao X, Lin B, Kulwin C, Chen J. Neuroprotective effect of dexmedetomidine in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2018;8(4935) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments-the ARRIVE guidelines. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:991–993. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.220. National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Veterinary Medical Association: AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition. American Veterinary Medical Association, Schaumburg, IL, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luong TN, Carlisle HJ, Southwell A, Patterson PH. Assessment of motor balance and coordination in mice using the balance beam. J Vis Exp. 2011;49(pii: 2376) doi: 10.3791/2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hausser N, Johnson K, Parsley MA, Guptarak J, Spratt H, Sell SL. Detecting behavioral deficits in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Vis Exp. 2018;131(56044) doi: 10.3791/56044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidi M, Foster TC. Behavioral model for assessing cognitive decline. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;829:145–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-458-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oddo M, Crippa IA, Mehta S, Menon D, Payen JF, Taccone FS, Citerio G. Optimizing sedation in patients with acute brain injury. Crit Care. 2016;20(128) doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1294-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flower O, Hellings S. Sedation in traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Int. 2012;2012(637171) doi: 10.1155/2012/637171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bejian S, Valasek C, Nigro JJ, Cleveland DC, Willis BC. Prolonged use of dexmedetomidine in the paediatric cardiothoracic intensive care unit. Cardiol Young. 2009;19:98–104. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109003515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu Z, Kaul M, Yan B, Kridel SJ, Cui J, Strongin A, Smith JW, Liddington RC, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of matrix metalloproteinases: Signaling pathway to neuronal cell death. Science. 2002;297:1186–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1073634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Han R, Zuo Z. Dexmedetomidine post-treatment induces neuroprotection via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in rats with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116:384–392. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen M, Wang S, Wen X, Han XR, Wang YJ, Zhou XM, Zhang MH, Wu DM, Lu J, Zheng YL. Dexmedetomidine exerts neuroprotective effect via the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in rats with traumatic brain injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoeler M, Loetscher PD, Rossaint R, Fahlenkamp AV, Eberhardt G, Rex S, Weis J, Coburn M. Dexmedetomidine is neuroprotective in an in vitro model for traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol. 2012;12(20) doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang MH, Zhou XM, Cui JZ, Wang KJ, Feng Y, Zhang HA. Neuroprotective effects of dexmedetomidine on traumatic brain injury: Involvement of neuronal apoptosis and HSP70 expression. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:8079–8086. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Kimelberg HK. Neuroprotection by alpha 2-adrenergic agonists in cerebral ischemia. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2005;3:317–323. doi: 10.2174/157015905774322534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mori-Okamoto J, Namii Y, Tatsuno J. Subtypes of adrenergic receptors and intracellular mechanisms involved in modulatory effects of noradrenaline on glutamate. Brain Res. 1991;539:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90687-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo P, Fei F, Zhang L, Qu Y, Fei Z. The role of glutamate receptors in traumatic brain injury: Implications for postsynaptic density in pathophysiology. Brain Res Bull. 2011;85:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung ZH, Ip NY. From understanding synaptic plasticity to the development of cognitive enhancers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:1247–1256. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sultana R, Banks WA, Butterfield DA. Decreased levels of PSD95 and two associated proteins and increased levels of BCl2 and caspase 3 in hippocampus from subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Insights into their potential roles for loss of synapses and memory, accumulation of Abeta, and neurodegeneration in a prodromal stage of alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:469–477. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao CY, Mirra SS, Sait HB, Sacktor TC, Sigurdsson EM. Postsynaptic degeneration as revealed by PSD-95 reduction occurs after advanced Aβ and tau pathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0843-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakade C, Sukumari-Ramesh S, Laird MD, Dhandapani KM, Vender JR. Delayed reduction in hippocampal post-synaptic density protein-95 expression temporally correlates with cognitive dysfunction following controlled cortical impact in mice. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:1195–1201. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.JNS091212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen T, Gupta R, Kaiser H, Sen N. Activation of PERK elicits memory impairment through inactivation of CREB and downregulation of PSD95 after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2017;37:5900–5911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2343-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang CF, Zhao CC, Jiang G, Gu X, Feng JF, Jiang JY. The role of posttraumatic hypothermia in preventing dendrite degeneration and spine loss after severe traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6(37063) doi: 10.1038/srep37063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.