Recent studies have identified two mutually exclusive recurrent rearrangements in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) that have important clinical significance (Feldman et al, 2011) (Vasmatzis et al, 2012). The DUSP22 rearrangement, which involves the DUSP22-IRF4 locus on 6p25.3, most commonly occurs as a t(6;7)(p25.3;q32.3)(2) and the TP63 rearrangement, which results from a TP63-TBL1XR1 inversion (Vasmatzis et al, 2012). In the first clinical report, DUSP22 rearrangements occurred in ~30% of all ALK-negative ALCL and were associated with a very favourable prognosis [5-year overall survival (OS) 90%] whereas TP63 rearrangements occurred in 8% and were associated with a dismal prognosis (5-year OS 17%) (Parrilla Castellar et al, 2014). The majority of ALK-negative ALCL were ‘triple negative’, lacking any known rearrangements, and had an intermediate prognosis (5-year OS 42%) (Parrilla Castellar et al, 2014). More recently, five cases of DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL from a Danish series (Pedersen et al, 2017a) and eight cases (including one PTCL-not otherwise specified) from an upfront transplant Phase 2 study (Pedersen et al, 2017b), were evaluated, with similar favourable outcomes (5 year OS >80%). These data have led to treatment guideline modifications, but represent a limited number of cases (NCCN 2018). Herein, we evaluated the frequency, clinical features and outcome of previously defined ALCL genetic subgroups in an independent series of systemic ALCL. In addition, the prognostic significance of immunohistochemical (IHC) markers was explored.

All cases of newly diagnosed ALCL were identified in the British Columbia Cancer Lymphoid Cancer database and confirmed by expert haematopathologists based on the World Health Organization classification (GWS, PF). A tissue microarray was constructed and IHC and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) was performed as previously described using in-house bacterial artificial chromosome break-apart probes for DUSP22 and TP63 loci (Figs S1 and S2) (Scott et al, 2012).

Of 62 ALK-negative ALCL cases evaluated, 12 (19%) harboured a DUSP22 rearrangement, one (2%) had a TP63 rearrangement and the remainder were triple negative (n = 49, 79%). All DUSP22 rearrangements were verified on whole sections and at an independent laboratory (AF).

Most patients (78%) received CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)/CHOP-like chemotherapy (92% in DUSP22) (Table I, Table SI). Some high-risk clinical features were noted in the DUSP22-rearranged cases: Median age 61·5 years; extranodal involvement (67%); bone/bone marrow involvement (42%); high lactate dehydrogenase (42%) (Table I).

Table I.

Baseline clinical features of 91 patients with systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

| Clinical features at diagnosis | ALCL by ALK status, n (%) | ALK-negative ALCL by subtype n (%) | All ALCLn (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALK-positive | ALK-negative | DUSP22 | P63 | Triple negative | ||

| Total n | 29 | 62 | 12 | 1 | 49 | 91 |

| Median age, years | 33 | 62 | 61–5 | 79 | 62 | 57 |

| (range) | 7–79 | 9–96 | 27–86 | 9–96 | 7–96 | |

| Male | 17 (59) | 46 (74) | 10 (83) | 0 | 36 (72) | 63 (69) |

| B symptoms | 19 (66) | 30 (48) | 5 (42) | 1 (100) | 24 (49) | 48 (53) |

| Bulky (≥10 cm) | 6 (21) | 8 (13) | 0 | 0 | 8 (17) | 14 (15) |

| PS ≥ 2 | 12 (44) | 24 (55) | 3 (25) | 1 (100) | 15 (37–5) | 30 (33) |

| Stage | ||||||

| 1 | 4 (14) | 10 (16) | 2 (12) | 0 | 8 (16) | 14 (15) |

| 2 | 7 (24) | 13 (21) | 1 (8) | 0 | 12 (24–5) | 20 (22) |

| 3 | 5 (17) | 11 (18) | 2 (12) | 0 | 9 (18) | 16 (18) |

| 4 | 13 (45) | 45 (28) | 7 (58) | 1 (100) | 20 (41) | 41 (45) |

| Extranodal (any) | 21 (72) | 39 (63) | 8 (67) | 1 (100) | 30 (61) | 60 (66) |

| Skin | 3 (10) | 9 (15) | 3 (25) | 0 | 6 (12) | 12 (13) |

| Soft tissue | 8 (28) | 13 (21) | 0 | 0 | 13 (27) | 21 (23) |

| Bone | 0 | 11 (18) | 4 (33)* | 0 | 7 (14) | 11 (12) |

| GI Tract | 1 (3) | 3 (5) | 3 (6) | 0 | 3 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Liver | 1 (3) | 4 (7) | 1 (8) | 0 | 3 (6) | 5 (6) |

| Lung | 4 (14) | 4 (7) | 1 (8) | 0 | 5 (10) | 10 (11) |

| Pleural effusion | 3 (10) | 6 (10) | 1 (8) | 1 (100) | 3 (6) | 7 (8) |

| Bone marrow/peripheral blood | 4 (14) | 8 (13) | 2 (12)* | 1 (100) | 5 (10) | 12 (13) |

| Extranodal >1 | 7 (24) | 21 (34) | 4 (33) | 1 (100) | 16 (33) | 28 (31) |

| LDH elevated | 10 (40) | 25 (4) | 6 (50) | 0 | 19 (42) | 48 (53) |

| LDH >2× ULN | 3 (10) | 12 (19) | 5 (42) | 0 | 12 (24) | 15 (17) |

| IPI | ||||||

| 0–1 | 8 (32) | 19 (31) | 5 (42) | 0 | 14 (31) | 27 (30) |

| 2 | 10 (40) | 11 (18) | 2 (12) | 0 | 9 (20) | 21 (23) |

| 3 | 3 (12) | 12 (20) | 2 (12) | 0 | 10 (22) | 15 (17) |

| 4–5 | 4 (16) | 15 (25) | 3 (25) | 1 (100) | 12 (27) | 20 (22) |

| Primary therapy | ||||||

| CHOP/CHOP(like) | 24 (83) | 46 (74) | 11 (92) | 0 | 35 (72) | 71 (78) |

| RT or surgery alone | 0 | 6 (10) | 1 (8) | 0 | 5 (10) | 6 (8) |

| Other | 3 (10) | 4 (7) | 0 | 0 | 4 (8) | 7 (8) |

| None | 2 (7) | 5 (9) | 0 | 1 (100) | 5 (10) | 7 (8) |

| Consolidative ASCT | - | - | 1 | - | - | - |

Missing data: LDH missing (ALK-positive n = 4; triple negative n = 4); IPI missing n = 8 (ALK-positive n = 4; triple negative n = 4); Mass size (n = 2); PS n = 12.

ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; GI, gastrointestinal; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PS, performance status; RT, radiotherapy; ULN, upper limit of normal.

One patient had bone and bone marrow involvement. Estimates were rounded.

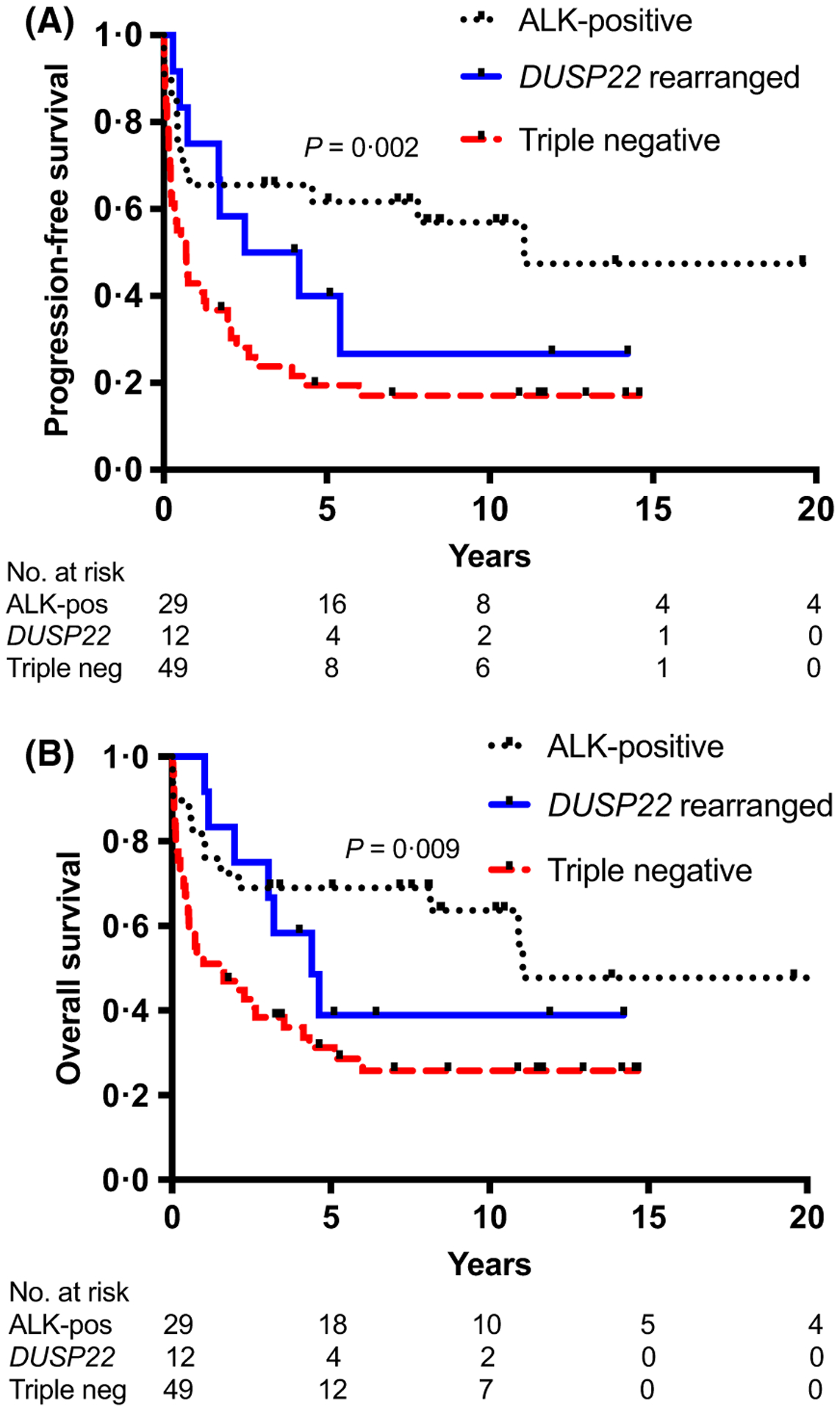

The median follow-up for all living patients was 8·6 years (range 1·8–34 years). Consistent with prior studies, outcomes in ALK-negative ALCL were inferior to those with ALK-positive ALCL [5-year progression-free survival (PFS) 23% vs. 62%, P < 0·002; 5-year OS 32% vs. 69%, P < 0·01] (Fig S3A,B). Of note, survival estimates for ALCL in our study are lower than some, but not all other series (Hapgood & Savage, 2015), possibly reflecting the population-based nature of this analysis.

Surprisingly, the outcome of DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL cases was lower than that observed in published series, with a 5-year PFS and OS of 40% (Fig 1A,B) and 5-year disease-specific survival of 45%, with similar findings when only those treated with curative intent chemotherapy are evaluated (DUSP22-rearranged, n = 11), 5-year PFS and OS 44%. One patient had a central nervous system (CNS) parenchymal relapse (Table SI). Interestingly, five of the relapses occurred over 1 year from diagnosis, including two ≥4 years. Further details on the clinical course are provided in the Supplementary Material. Of note, the 5-year PFS and OS estimates were poor for triple negative ALK-negative ALCL (19% and 28%, respectively) but comparable to the Danish series (n = 20, 5-year OS 33%) (Fig 1A,B). The sole case with a TP63 rearrangement died within 6 months of diagnosis.

Fig 1.

Survival curves. (A) Progression-free survival by genetic subgroup: anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive, DUSP22-rearranged and triple negative. (B) Overall survival by genetic subgroup: ALK-positive, DUSP22-rearranged and triple negative. Note: the sole case of TP63-rearranged ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is excluded from this analysis. P-value is across all groups.

Excluding the case with a TP63 rearrangement, multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) using ALK-positive ALCL as the reference group (Table SII). There was no statistical difference in OS and PFS in both crude and adjusted [for international prognostic index (IPI) and age] analyses. Similarly, no differences were observed using triple negative cases as the reference group (results not shown). This may reflect the challenge of analysing small datasets with limited power. Regardless, the outcome observed in DUSP22-rearranged cases remains of clinical significance.

Despite the aggressive clinical course in some patients, the IHC features of DUSP22-rearranged cases were in keeping with prior reports and highlight that it is a defined entity. CD2 and CD3 expression was frequent and all cases were EMA negative (Table SIII) (Parrilla Castellar et al, 2014). Most cases were cytotoxic marker-negative and all were negative for pSTAT3 and PDL1 (Luchtel et al, 2018) (Table SIII). Taken together, this data suggests that there may be further genetic and/or biological heterogeneity that impacts prognosis, which can only be captured in larger datasets.

Despite usually good outcomes, higher risk groups have been noted in ALK-positive ALCL, including older patients, multiple IPI risk factors and CD3+ tumours (Sibon et al, 2017). CD3 positivity was also associated with an inferior outcome in triple negative cases in our cohort, a finding that has not been previously reported (5-year OS 18% vs. 40%, P = 0·01; 5-year PFS 7% vs. 28%, P = 0·05 in the CD3+ and CD3− groups, respectively) (Fig S4A,B). This was consistent after adjusting for the IPI (OS: HR 2·31 (95% confidence interval 1·16, 4·61, P = 0·017); PFS: HR 1·825 (95% confidence interval 0·95, 3·51, P = 0·07). Our data suggests that triple negative cases may also not be a homogeneous group and further studies are needed to confirm these findings and investigate the functional consequence.

In summary, in this comprehensive clinico-pathological and genetic analysis, we confirm that DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL have unique pathological features. However, similar to prior observations in ALK-positive ALCL, some can present with high risk clinical features and have an aggressive course, including CNS relapse. CD3+ triple negative ALK-negative ALCL is associated with a dismal outcome, supporting additional heterogeneity in the largest subgroup. Additional large-scale studies are needed to fully understand the full disease spectrum of ALK-negative ALCL.

Supplementary Material

Table SI. Clinical features at diagnosis and outcome of twelve cases of DUSP22 rearranged ALK-negative ALCL.

Table SII. Multivariate Cox regression model for overall survival and progression-free survival: Unadjusted and adjusted analysis.

Table SIII. Immunohistochemical features in ALCL by genetic subtype.

Fig S1. (A) Bacterial artificial chromosome (BACs) used for fluorescence in situ hybridization DUSP22 break-apart assays with hg 19 co-ordinates. (B) Partial karyotype showing the expected site of chromosomal localization (6p25.3) on normal metaphases. (C) Schematic diagram indicating the alignment of in house BAC probes to the DUSP22 locus of UCSC Hg19. (D) A representative example of interphases with DUSP22 break-apart in an ALCL case demonstrating a rearrangement, with 1 normal fusion and separation of the red and green signal (arrows).

Fig S2. (A) Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) used for fluorescence in situ hybridization break-apart assays detect TP63 rearrangements with hg 19 coordinates. (B) Partial karyotype showing the expected site of chromosomal localization (3q28) on normal metaphases. (C) Schematic diagram indicating the alignment of in house BAC probes to the TP63 locus of UCSC Hg19. (D) Sole case of TP63 break-apart rearrangement, with 1 normal fusion and separation of the red and green signal (arrows) indicating a rearrangement.

Fig S3. (A) Progression-free survival ALK-positive (pos) versus ALK-negative (neg) ALCL. (B) Overall survival of ALK-positive versus ALK-negative.

Fig S4. (A) Progression free survival in triple negative ALK-negative (neg) ALCL by CD3 expression. (B) Overall survival in triple negative ALK-negative (neg) ALCL by CD3 expression.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kathryn E. Pierce, laboratory development co-ordinator, Mayo Clinic. FISH studies at the Mayo Clinic were supported by R01 CA177734 from the National Cancer Institute. This work is supported by a Terry Fox Research Institute team grant (#1023 and #1061) to RDG and CS. We thank the British Columbia Cancer Foundation for their support. CS is supported by a career investigator award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- Feldman AL, Dogan A, Smith DI, Law ME, Ansell SM, Johnson SH, Porcher JC, Ozsan N, Wieben ED, Eckloff BW & Vasmatzis G (2011) Discovery of recurrent t(6;7) (p25.3;q32.3) translocations in ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas by massively parallel genomic sequencing. Blood, 117, 915–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapgood G & Savage KJ (2015) The biology and management of systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood, 126, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchtel RA, Dasari S, Oishi N, Pedersen MB, Hu G, Rech KL, Ketterling RP, Sidhu J, Wang X, Katoh R, Dogan A, Kip NS, Cunningham JM, Sun Z, Baheti S, Porcher JC, Said JW, Jiang L, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Moller MB, Norgaard P, Bennani NN, Chng WJ, Huang G, Link BK, Facchetti F, Cerhan JR, d’Amore F, Ansell SM & Feldman AL (2018) Molecular profiling reveals immunogenic cues in anaplastic large cell lymphomas with DUSP22 rearrangements. Blood, 132, 1386–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCCN. (2018) T-cell lymphomas. NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2018. December 17 2018 National Comprehensive Cancer Network. www.nccn.org [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrilla Castellar ER, Jaffe ES, Said JW, Swerdlow SH, Ketterling RP, Knudson RA, Sidhu JS, Hsi ED, Karikehalli S, Jiang L, Vasmatzis G, Gibson SE, Ondrejka S, Nicolae A, Grogg KL, Allmer C, Ristow KM, Wilson WH, Macon WR, Law ME, Cerhan JR, Habermann TM, Ansell SM, Dogan A, Maurer MJ & Feldman AL (2014) ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a genetically heterogeneous disease with widely disparate clinical outcomes. Blood, 124, 1473–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MB, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, Ellin F, Lepp€a S, Mannisto S, Jantunen E, Ketterling RP, Bedroske P, Luoma I, Sattler C, Delabie JM, Sundstrom C, Sander B, Karjalainen-Lindsberg M, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Ehinger M, Vornanen M, Ralfkiaer E, Boddicker R, Bennani NN, Oishi N, Moeller MB, Noergaard P, Cerhan JR, Maurer MJ, Liestol K, Toldbod H, Feldman AL & d’Amore F (2017a) The impact of upfront autologous transplant on the survival of adult patients with ALCL and PTCL-NOS according to their ALK, DUSP22 and TP63 gene rearrangement status - a Joined Nordic Lymphoma Group and Mayo Clinic Analysis. Blood, 130, 822. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MB, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Bendix K, Ketterling RP, Bedroske PP, Luoma IM, Sattler CA, Boddicker RL, Bennani NN, Norgaard P, Moller MB, Steiniche T, d’Amore F & Feldman AL (2017b) DUSP22 and TP63 rearrangements predict outcome of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a Danish cohort study. Blood, 130, 554–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DW, Mungall KL, Ben-Neriah S, Rogic S, Morin RD, Slack GW, Tan KL, Chan FC, Lim RS, Connors JM, Marra MA, Mungall AJ, Steidl C & Gascoyne RD (2012) TBL1XR1/TP63: a novel recurrent gene fusion in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood, 119, 4949–4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibon D, Nguyen D, Schmitz N, Suzuki R, Feldman AL, Gressin R, Lamant L, Weisenburger DD, Nakamura S, Ziepert M, Maurer MJ, Bast M, Armitage JO, Vose JM, Tilly H, Jais J & Savage KJ (2017) Systemic ALK-Positive Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma (ALCL): final analysis of an International, Individual Patient Data Study of 263 Adults. Blood, 130, 1514.28774880 [Google Scholar]

- Vasmatzis G, Johnson SH, Knudson RA, Ketterling RP, Braggio E, Fonseca R, Viswanatha DS, Law ME, Kip NS, Ozsan N, Grebe SK, Frederick LA, Eckloff BW, Thompson EA, Kadin ME, Milosevic D, Porcher JC, Asmann YW, Smith DI, Kovtun IV, Ansell SM, Dogan A & Feldman AL (2012) Genome-wide analysis reveals recurrent structural abnormalities of TP63 and other p53-related genes in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood, 120, 2280–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table SI. Clinical features at diagnosis and outcome of twelve cases of DUSP22 rearranged ALK-negative ALCL.

Table SII. Multivariate Cox regression model for overall survival and progression-free survival: Unadjusted and adjusted analysis.

Table SIII. Immunohistochemical features in ALCL by genetic subtype.

Fig S1. (A) Bacterial artificial chromosome (BACs) used for fluorescence in situ hybridization DUSP22 break-apart assays with hg 19 co-ordinates. (B) Partial karyotype showing the expected site of chromosomal localization (6p25.3) on normal metaphases. (C) Schematic diagram indicating the alignment of in house BAC probes to the DUSP22 locus of UCSC Hg19. (D) A representative example of interphases with DUSP22 break-apart in an ALCL case demonstrating a rearrangement, with 1 normal fusion and separation of the red and green signal (arrows).

Fig S2. (A) Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) used for fluorescence in situ hybridization break-apart assays detect TP63 rearrangements with hg 19 coordinates. (B) Partial karyotype showing the expected site of chromosomal localization (3q28) on normal metaphases. (C) Schematic diagram indicating the alignment of in house BAC probes to the TP63 locus of UCSC Hg19. (D) Sole case of TP63 break-apart rearrangement, with 1 normal fusion and separation of the red and green signal (arrows) indicating a rearrangement.

Fig S3. (A) Progression-free survival ALK-positive (pos) versus ALK-negative (neg) ALCL. (B) Overall survival of ALK-positive versus ALK-negative.

Fig S4. (A) Progression free survival in triple negative ALK-negative (neg) ALCL by CD3 expression. (B) Overall survival in triple negative ALK-negative (neg) ALCL by CD3 expression.