Abstract

Objectives:

The probability of insulin independence after intraportal islet autotransplantation (IAT) for chronic pancreatitis (CP) treated by total pancreatectomy (TP) relates to the number of islets isolated from the excised pancreas. Our goal was to correlate the islet yield with the histopathologic findings and the clinical parameters in pediatric (age, <19 years) CP patients undergoing TP-IAT.

Methods:

Eighteen pediatric CP patients aged 5 to 18 years (median, 15.6 years) who underwent TP-IAT were studied. Demographics and clinical history came from medical records. Histopathologic specimens from the pancreas were evaluated for presence and severity of fibrosis, acinar cell atrophy, inflammation, and nesidioblastosis by a surgical pathologist blinded to clinical information.

Results:

Fibrosis and acinar atrophy negatively correlated with islet yield (P = 0.02, r = −0.50), particularly in hereditary CP (P = 0.01). Previous duct drainage surgeries also had a strong negative correlation (P = 0.01). Islet yield was better in younger (preteen) children (P = 0.02, r = −0.61) and in those with pancreatitis of shorter duration (P = 0.04, r = −0.39).

Conclusions:

For preserving beta cell mass, it is best to perform TP-IAT early in the course of CP in children, and prior drainage procedures should be avoided to maximize the number of islets available, especially in hereditary disease.

Keywords: islet autotransplantation, chronic pancreatitis, pediatrics, fibrosis, acinar atrophy, islet yield

The main goal in the treatment for patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP) is to achieve pain relief without dependence on opioids while preserving as much pancreatic function as possible, particularly endocrine.1 Other than narcotic analgesics, medical treatments, such as giving pancreatic enzymes orally for feedback inhibition, have very limited effect on the pain of CP, and nerve blocks or ablations, even if initially effective, do not give durable pain relief in most patients.1,2

Direct interventions on the pancreas in attempts to obtain pain relief are of 2 broad classifications: duct drainage or resection. Surgical or endoscopic duct drainage procedures are usually done if there is a dilated duct or evidence of obstruction3,4; pancreatic resection (partial or total) is done if the duct is not dilated or obstructed5 or if drainage procedures have failed to provide pain relief.6

A total pancreatectomy (TP) is more likely to provide pain relief than a partial pancreatectomy but poses the problem of making diabetes and insulin dependence inevitable unless sufficient beta cell mass is preserved by islet isolation and autotransplantation from the resected pancreas.7 At the University of Minnesota, we have done islet isolation in conjunction with TP for the treatment of CP since 1977.8 Our series includes both adults and children,9 the first child undergoing the procedure in 1989.10 Previous studies of both the adults11-14 and the children15 in our series showed that at least some beta cell function could be preserved in nearly two thirds of the patients after TP–islet autotransplantation (TP-IAT) and insulin independence could be maintained in approximately a third.

In the recently published retrospective analysis of outcomes in our pediatric cases,15 the probability of preserving insulin independence after TP-IAT directly correlated with the islet yield and the number of islet equivalents (IEs) embolized to the liver via the portal vein. The islet yield is quite variable from case to case. It would be useful to predict the islet yield and the probability of insulin independence in individual cases. Thus, the current analysis was performed to determine which histopathologic and clinical features are associated with high or low yields in pediatric patients with CP undergoing TP-IAT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

This study was conducted retrospectively using clinical information available in the medical records and stored histopathologic specimens from the excised pancreas of the patients. Between July 1989 and December 2006, 26 pediatric patients (<19 years old) underwent TP-IAT to treat CP.15 In 18 of these patients, biopsies of the resected pancreases were obtained before processing the organs for islet isolation. We analyzed the correlation between clinical findings, pancreatic histological findings, and islet yield in these 18 patients.

Medical Records Review

Patient medical records were reviewed for the following information: sex, age at surgery, age at onset of pancreatitis, duration of disease, etiology of CP, prior pancreatic surgeries, narcotic use, and total IEs and IE per kilogram body weight isolated at the time of surgery.

Operative Procedures

Of these 18 patients, 12 underwent 1-stage TP; 5, completion (thus resulting in total) pancreatectomy; and 1, near TP (95%). Our operative techniques for near or total pancreatectomy for CP was described in 1991.11 For TP, the pylorus and the distal duodenum were preserved whenever possible, and only the second portion of the duodenum was resected with the pancreas, maintaining the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arterial arcade as recently described in detail by Nakao and Fernandez-Cruz.16 Enterobiliary reconstruction was done by an end-to-end duodenoduodenostomy whenever possible and when not by an end-to-end or end-to-side duodenojejunostomy. Bile duct continuity was usually restored by a choledochoenterostomy adjacent to the duodenoduodenostomy or duodenojejunostomy. When the peripancreatic duodenal inflammation was extensive, the entire duodenum was resected, as in a standard Whipple procedure extended to remove the entire pancreas. To preserve islet viability for the autotransplant, the blood supply to the pancreas was preserved as long as possible to minimize warm ischemic time; thus, the last step in the pancreatectomy procedure was to ligate and divide the splenic artery and vein at their origin and termination, respectively. Before this step, the vessels were ligated and divided distally in the hilum of the spleen; if the spleen remained viable on its collateral circulation, it was left in, if not it was removed.

Islet Preparation and Transplantation

After resection, the pancreas was immediately placed in a balanced salt preservation solution at 4°C and transported to the islet processing laboratory. Free islets were prepared by collagenase digestion of the pancreas, using the semiautomated technique as described by Ricordi et al.17 The pancreas was distended intraductally with collagenase (purchased from Sigma, Worthington, or Roche Companies) dissolved in a buffer solution and incubated at 37°C. The digested tissue was washed 3 to 5 times and concentrated. If the final pellet volume was less than 20 mL, the islets were not further purified and the tissue was simply diluted in at least 200 mL of the preservation solution, placed in plastic infusion bags, and transported back to the operating room. When the total pellet volume was more than 20 mL, the islets were separated from the nonislet tissue by gradient purification using a COBE 2991 cell processor (CaridianBCT, Lakewood, Colo) and then diluted and bagged for transport.

Islet preparation took approximately 3 hours, and the autografts were done within 5 hours of pancreatectomy. The patients were given 70 U/kg of heparin intravenously just before embolization of the islet preparation to the liver by slow infusion into the portal vein (20–60 minutes). Portal venous pressure was measured before and during infusion, and the infusion was stopped if the portal pressure increased to higher than 30 cm of water.18 All islets were embolized to the liver in 14 cases, but in 4, because the portal pressure limit was reached, the islet infusion was stopped and the residual tissue was placed elsewhere: under the kidney capsule in 2, in the stomach subserosa in 1, and intraperitoneal in 1.

Histopathologic Studies of Excised Pancreas

Biopsy specimens from the excised pancreases were retrieved from the files of the Department of Pathology or the Diabetes Institute for Immunology and Transplantation, University of Minnesota Medical Center. Material for histological examination was available on 18 patients who were 5 to 18 years old at the time of TP-IAT for CP. Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections from all blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were also stained for islet hormones using the immunoperoxidase technique.

Pancreatic tissue sections were evaluated microscopically by a surgical pathologist without knowledge of the clinical data and islet yield. The extent of parenchymal fibrosis and acinar cell atrophy were scored from 0 to 4, based on the estimated percentage of the area involved: 0, no change; 1, minimal (less than 5%); 2, mild (5%–20%); 3, moderate (20%–50%); and 4, severe (>50%). The extent of inflammation was scored as absent (0), minimal or mild (1), moderate (2), and severe (3). Distribution of fibrosis, acinar cell atrophy, and inflammation (focal or diffuse, periductal [P] and/or interstitial [I], and/or septal [S]) was also evaluated. The extent of nesidioblastosis was scored from 0 to 3, based on the number and size of endocrine cell aggregates budding from ducts: 0, absent; 1, rare to occasional, small aggregates of endocrine cells; 2, moderate number of aggregates of endocrine cells, generally of small size; 3, numerous aggregates of endocrine cells of variable size.

Assessment of Clinical Outcomes

Postsurgical insulin use, pain medication use, and quality of life were ascertained from the medical records and/or from a questionnaire administered to patients or patient families as part of a retrospective analysis.15 Subjects were asked to return a hemoglobin A1c kit by mail to confirm glycemic control in those patients on minimal or no insulin.

Statistical Analysis

Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the significance of differences in median values. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the association between the number of IE per kilogram and the histopathologic score, the age at IAT, and the duration of symptoms. For all statistical tests, P < 0.05 defined significance.

RESULTS

Summary of Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical information for the 18 pediatric patients (11 were female, and 7 were male) aged 5.8 to 18.9 years (median, 15.6 years), of whom 7 were preteen or prepubertal. The age of pancreatitis onset ranged from 1.2 to 16.9 years (median, 6.9 years), and the duration before TP-IAT ranged from 0.8 to 15.5 years (median, 5.3 years).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient | Sex | Etiology of CP | Age at Onset of CP, yr |

Age at IAT, yr |

Narcotics at Admission |

Previous Surgery for CP |

Islet Yield (IE/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | Familial | 8 | 18.9 | Yes | DP | 939 |

| 2 | F | Biliary | 14.9 | 16.3 | Yes | DP and pseudocyst drainage | 6538 |

| 3 | M | Drug induced* | 8.3 | 9.1 | No | DP and pseudocyst drainage | 4268 |

| 4 | F | Idiopathic | 5.6 | 7.9 | Yes | No surgery | 12,561 |

| 5 | F | Idiopathic | 3.6 | 10.2 | Yes | Puestow | 5482 |

| 6 | F | Divisum | 12.8 | 16.1 | Yes | Frey | 1386 |

| 7 | M | Familial | 1.2 | 15.6 | Yes | Puestow and DP | 178 |

| 8 | F | Familial | 3 | 18.5 | Yes | Sphincterotomy and Puestow | 449 |

| 9 | F | Familial/hereditary† | 3.4 | 7.7 | No | Sphincterotomies | 1240 |

| 10 | F | Idiopathic | 12.6 | 16.5 | Yes | DP | 4839 |

| 11 | M | Cystic fibrosis | NA | 5.8 | No | Papillotomy | 10,647 |

| 12 | F | Idiopathic | 10.4 | 15.7 | Yes | Sphincterotomy | 5063 |

| 13 | F | Annular pancreas | 3.4 | 13.9 | No | No surgery | 11,576 |

| 14 | M | Familial | 4.5 | 7.5 | Yes | Sphincterotomies | 12,576 |

| 15 | M | Familial | 2 | 15.6 | Yes | No surgery | 515 |

| 16 | M | Idiopathic | 6.9 | 12.8 | No | Sphincterotomies | 8125 |

| 17 | F | Familial | 16.9 | 18.3 | No | No surgery | 1420 |

| 18 | M | Idiopathic | 8 | 18.4 | Yes | No surgery | 4065 |

Patients 13 and 16 underwent partial purification after islet isolation.

Secondary to 2 l-asparginase.

No family history; genetic analysis confirmed mutation of serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 (SPINK1).

DP indicates distal pancreatectomy; F, female; Frey, limited pancreatic head excision combined with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy; M, male; NA, not available; Puestow, lateral pancreaticojejunostomy.

The diagnosis of the CP was based on the history; the results of computed tomography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and/or endoscopic ultrasound; and the prior histopathologic findings in patients who had undergone surgical treatment of CP. The etiology of CP was classified as familial/hereditary in 7 patients, idiopathic in 6, and biliary, pancreas divisum, cystic fibrosis, annular pancreas, and drug induced in 1 patient each.

Eight patients had a prior surgical drainage procedure or partial pancreatic resection for management of CP (4, distal pancreatectomy [tail]; 2, Puestow procedure; 1, Puestow procedure plus distal pancreatectomy; 1, Frey procedure). An additional 5 patients had a prior history of sphincterotomy or papillotomy.

All the patients had abdominal pain and had received or were currently taking narcotic analgesics. These patients were highly selected in that they were referred for TP-IAT because all previous medical and/or surgical treatment had failed to alleviate pain.

Islet yields from the excised pancreases ranged from 178 to 12,576 IE/kg (median 4554 IE/kg). Eleven (61%) of the 18 patients had yields of more than 4000 IE/kg.

Summary of Histopathologic Findings

Pathologic findings are summarized in Table 2. Representative histopathologic changes are illustrated in Figure 1.

TABLE 2.

Histopathologic Findings

| Patient | Fibrosis |

Acinar Atrophy |

Inflammation |

Nesidioblastosis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Distribution | Location | Degree | Distribution | Degree | Distribution | Location | Type | Degree | |

| 1 | 4 | Diffuse | I and P | 4 | Diffuse | 1 | Diffuse | P | C | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | Diffuse | P and S | 2 | Diffuse | 1 | Focal | S | C | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | Focal | P and I | 2 | Focal | 1 | Focal | P | C | 0 |

| 5 | 4 | Diffuse | P, I, and S | 4 | Diffuse | 2 | Focal | P | C | 0 |

| 6 | 4 | Diffuse | I | 4 | Diffuse | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 2 |

| 7 | 4 | Diffuse | P and I | 4 | Focal | 1 | Focal | P | C | 0 |

| 8 | 4 | Focal | P, I, and S | 4 | Focal | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 2 |

| 9 | 4 | Diffuse | P and I | 4 | Diffuse | 1 | Focal | P | C | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | Focal | P | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| 11 | 4 | Diffuse | P and I | 3 | Focal | 1 | Focal | P and I | A, C | 1 |

| 12 | 2 | Focal | P and I | 2 | Focal | 1 | Focal | P | C | 1 |

| 13 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| 14 | 3 | Diffuse | P and S | 3 | Focal | 2 | Diffuse | I and S | A, C | 0 |

| 15 | 3 | Diffuse | P and S | 3 | Diffuse | 1 | Focal | P | C | 1 |

| 16 | 1 | Diffuse | P and S | 2 | Diffuse | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| 17 | 4 | Diffuse | P, I, and S | 4 | Diffuse | 1 | Focal | S | C | 2 |

| 18 | 2 | Focal | P and S | 2 | Focal | 1 | Focal | P | C | 1 |

Degree of fibrosis: 0, absent; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; and 4, severe. Degree of acinar atrophy: 0, absent; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; and 4, severe. Degree of inflammation: 0, absent; 1, minimal-mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe. Degree of nesidioblastosis: 0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe.

A indicates acute; C, chronic; NA, not applicable.

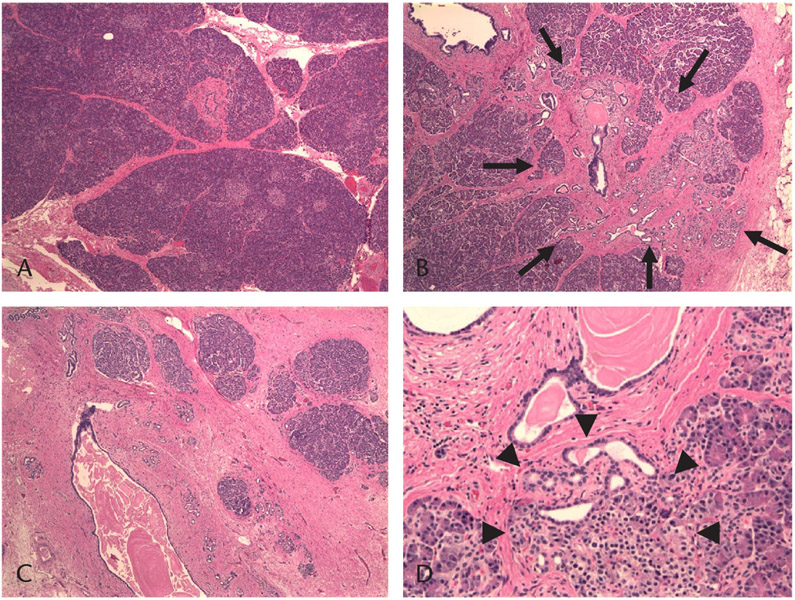

FIGURE 1.

Histopathologic examination of an excised pancreas showing various degrees of fibrosis, acinar atrophy, inflammation, and nesidioblastosis. Paraffin-embedded sections were prepared and attained with hematoxylin and eosin. A, Example of minimal fibrosis without acinar atrophy or inflammation. Minimal focal periductal fibrosis is seen. B, Example of moderate fibrosis and acinar atrophy. Note the more prominent, focal periductal and septal (interlobular) moderate fibrosis and acinar atrophy (arrows). C, Example of severe fibrosis and atrophy. Note the diffuse severe fibrosis and acinar atrophy; mild chronic inflammation is also present. D, Nesidioblastosis and ductular proliferation are shown (arrowheads).

Parenchymal fibrosis was scored as absent in 2 patients (11%), minimal in 2 (11%), mild in 4 (22%), moderate in 2 (11%), and severe in 8 (44%). Acinar atrophy was scored as absent in 3 patients (17%), minimal in 0, mild in 5 (28%), moderate in 3 (17%), and severe in 7 (39%). The inflammatory cell infiltration was scored as absent in 6 patients (33%), minimal to mild in 10 (56%), moderate in 2 (11%), and severe in 0. Nesidioblastosis was present in 9 patients (50%) and was scored as 1 in 5 (28%), 2 in 3 (17%), and 3 in 1 (6%). The 5 patients with the most prominent nesidioblastosis (grade 2 or 3) all had severe parenchymal fibrosis and acinar atrophy, suggesting that nesidioblastosis may be a late finding of a severely damaged pancreas.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed for insulin, glucagon, and chromogranin. There was a strong trend toward decreased insulin-positive staining in areas of nesidioblastosis compared with normal islets (mean ± SD, 71.1 ± 20.3% vs 86.2 ± 6.9%, P = 0.053). No other significant abnormalities in islet insulin or glucagon composition were identified by immunohistochemical stains.

Correlation Between the Extent of Histological Changes and the Islet Yield

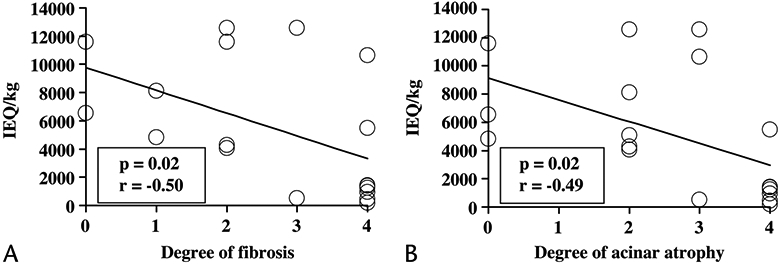

There was a statistically significant negative correlation between the degree of fibrosis and the IE per kilogram (P = 0.02, r = −0.50; Fig. 2A) and between the degree of acinar atrophy and the IE per kilogram (P = 0.015, r = −0.49; Fig. 2B). More severe fibrosis or acinar atrophy was associated with a lower islet yield. All patients with no more than mild fibrosis (<20% fibrosis, n = 8) received more than 4000 IE/kg. In contrast, more than 4000 IE/kg were recovered in just 1 of 2 patients with moderate fibrosis (20%–50%) and in only 2 (25%) of 8 with severe fibrosis (>50%). Similarly, when acinar atrophy was no more than mild, more than 4000 IE/kg were recovered in all patients (n = 8) and in 2 (67%) of 3 with moderate acinar atrophy, but such a yield was obtained in only 1 (17%) of 7 with severe acinar atrophy.

FIGURE 2.

Correlation between the extent of histological changes and islet yield. There was a negative correlation between the degree of fibrosis and IE per kilogram (A) and between the degree of acinar atrophy and IE per kilogram (B). Degree of fibrosis: 0, absent; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; and 4, severe. Degree of acinar atrophy: 0, absent; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; and 4, severe.

There was no statistical correlation between the degree of inflammation and the IE per kilogram (P = 0.66). No other histopathologic factors (distribution and location of fibrosis, distribution of acinar atrophy, distribution and location, or type of inflammation) correlated with islet yield.

We also examined the IE per gram of the pancreas tissue. The IE per gram similarly correlated with fibrosis (P = 0.003, r = −0.67) and acinar atrophy (P = 0.001, r = −0.72) but not with inflammation (P = 0.12).

Association of Clinical Variables With the Degree of Histological Change

The etiology of the pancreatic disease and the past pancreatic surgical history also correlated with the histological findings. Patients with familial CP (n = 7) had more severe fibrosis (P = 0.01) and acinar atrophy (P = 0.01) than those with idiopathic CP (n = 6). Patients with a history of prior drainage procedure (Puestow or Frey) had more severe fibrosis (P = 0.03) and acinar atrophy (P = 0.01) than other patients. Sex, previous history of distal pancreatectomy, and narcotics usage at the time of surgical admission were not related to histological changes.

Correlation Between Age at IAT, Duration of CP, Prior Surgeries, and Islet Yield

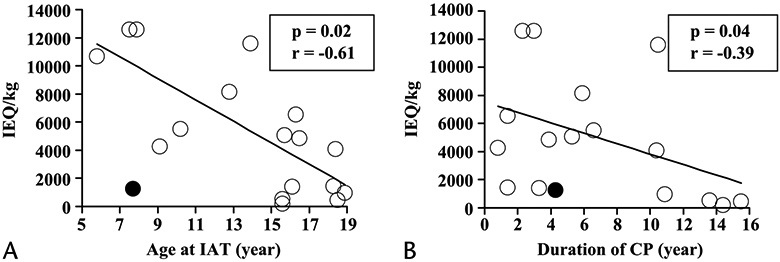

The patient age at pancreatectomy and IAT was negatively correlated with islet yield (IE/kg; P = 0.02, r = −0.61; Fig. 3A). When the analysis was performed without case 9 (the only patient who underwent partial [near total] pancreatectomy), the significance of this correlation was even greater (P = 0.008, r = −0.74). Thus, a younger age at pancreatectomy and IAT was associated with a greater islet yield. More than 4000 IE/kg were recovered in all patients 13 years or younger (n = 7, without case 9) but in only 40% of the patients older than this (4 of 10).

FIGURE 3.

Correlation between age at IAT and duration of CP and islet yield. A, Age at pancreatectomy and IAT correlated with islet yield (IE/kg). B, Duration of CP is also correlated with IE per kilogram. Patient 9 (closed circle) underwent partial pancreatectomy only; all other patients (open circle) underwent total or completion pancreatectomy.

The duration of CP was negatively correlated with islet yield (P = 0.04, r = −0.39; Fig. 3B). More than 4000 IE/kg were recovered in 75% of the patients (9 of 12) with less than 7 years’ duration of CP but in only 33% of patients (2 of 6) with more than 7 years’ duration of CP.

There was a strong trend toward a lower IE per kilogram (P = 0.08) and a lower IE per gram (P = 0.06) in those patients with a prior history of a Puestow or a Frey procedure (n = 4). In contrast, in this small set of patients, the history of prior distal pancreatectomy did not result in a significantly lower IE per kilogram (P = 0.32) or IE per gram (P = 0.95).

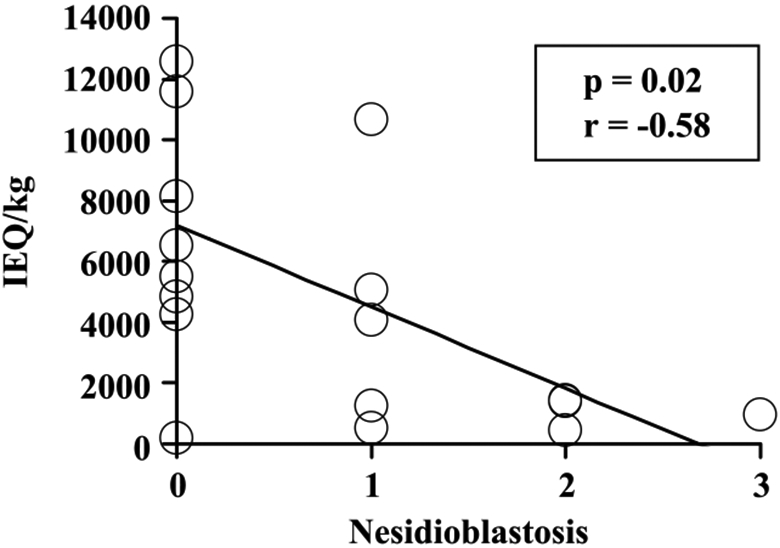

Correlation Between Nesidioblastosis With Clinical and Other Histological Features

The degree of nesidioblastosis correlated positively with the extent of fibrosis (P = 0.01, r = 0.59), severity of inflammation (P = 0.02, r = 0.57), and patient age at IAT (P = 0.03, r = 0.50). Greater nesidioblastosis was associated with a poorer islet yield (P = 0.02, r = −0.58; Fig. 4). Thus, nesidioblastosis tends to increase with age and with late stages of CP in children and has a negative impact on islet yield.

FIGURE 4.

Correlation between nesidioblastosis with islet yield (IE/kg). There was a negative correlation between the degree of nesidioblastosis and IE per kilogram. Nesidioblastosis is scored as 0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe.

Postoperative Outcomes

The clinical course and the postsurgical outcomes for these patients were included in greater detail in a prior publication.15 Briefly, these 18 patients were hospitalized for a mean ± SD duration of 24 ± 18 days after surgery. Nine patients experienced 1 or more postoperative complication: intraabdominal infection requiring drainage in 2, line infection or bacteremia in 2, urinary tract infection in 2, pneumonia in 4, and splenic infarct in 2.

Insulin requirements, pain symptoms, and quality-of-life outcomes are available for 15 of the 18 patients included in this analysis at a variable duration after transplant (mean ± SD, 3.1 ± 2.4 years). At follow-up, 6 patients were insulin independent, 3 were on once-daily glargine alone, and 6 were on a basal-bolus insulin regimen. Good glycemic control was confirmed by hemoglobin A1c in 5 of the insulin-independent patients (range, 5.0%–5.9%); 1 insulin-independent subject did not provide a sample for hemoglobin A1c analysis. The IE per kilogram was significantly greater in the insulin-independent patients than in those requiring insulin therapy (P = 0.004).

Four patients continued on narcotic pain medications, although 2 of these patients were on relatively mild medications (tramadol in 1 and suboxone in 1). Of the 13 patients responding to a telephone questionnaire, all patients reported pain as absent (n = 10) or better (n = 3). Overall quality of life was characterized as excellent or good in 10 of these 13 patients. All patients were prescribed with pancreatic enzymes. Weight loss or failure to gain weight normally on enzyme therapy was reported in 1 patient.

DISCUSSION

Fibrosis, acinar atrophy, and inflammation are seen in pancreas samples from children with CP, similar to findings in adult patients.19,20 As in adults, various degrees of nesidioblastosis are also seen, mainly in the late stage of CP.21 In the TP-IAT cases described in this report, islet yield was lower in pancreases with nesidioblastosis than in pancreases without nesidioblastosis, suggesting that nesidioblastosis is a response to progressive islet destruction while the pathologic process of CP advances.

The pertinent findings in our analysis are that (1) the greater the degree of pancreatic fibrosis and acinar atrophy, the lower the islet yield (IE/kg) in children undergoing TP-IAT to treat CP and that (2) the islet yield is much better in younger children than in older children, in part because of the longer duration of CP in the teenagers. Because insulin independence after pancreatectomy and IAT correlates highly with the number of islets transplanted,15 these data suggest that performing the surgery at an earlier stage of the disease is advantageous, particularly in the cases of familial CP, which showed an association with more severe histopathologic changes than those of idiopathic CP in our pediatric study population.

Patients who had a history of prior drainage procedures (Puestow or Frey) had more severe disease by histopathologic examination and a trend toward fewer islets recovered, both in IE per kilogram and IE per gram. Drainage procedures may increase fibrosis and other histological changes by the intervention itself or by simply delaying the definitive therapy with TP-IAT as the pathologic condition naturally progresses. In either case, surgical drainage procedures are associated with a reduced islet yield and a lower probability of insulin independence. We had previously found in adults undergoing TP-IAT that a prior Puestow procedure or distal pancreatectomy reduced the mean islet yield by 30% to 70% and lowered the proportion of patients able to remain insulin independent.22 In this retrospective analysis of children, we could not ascertain that the patients who underwent surgical drainage had more severe disease clinically than those who did not, but having had drainage was predictive of a more severe histopathologic condition and a lower islet yield at the time of TP-IAT.

Interestingly and in contrast to the adults, our 3 children who underwent distal pancreatectomy by itself before a completion pancreatectomy-IAT all had islet yields more than 4000 IE/kg; the only child with a prior distal pancreatectomy with a low yield was the one who also had a Puestow procedure. The higher islet yields in children than in adults who underwent distal pancreatectomy before TP-IAT may relate to differences in the extent of the initial resection because in our adult series, both the body and the tail had usually been removed, whereas in the children, only the tail or part of the tail may have been excised before TP-IAT. Thus, we would still caution against distal pancreatectomy as an initial operation for CP in children because of the potential to remove so much beta cell mass that a subsequent completion pancreatectomy will result in a low islet yield. In addition, we caution against a Puestow operation for the same reason.

Younger age at the time of TP-IAT and shorter duration of CP clearly resulted in a higher islet yield. One could hypothesize that this was because the procedure was performed before extensive damage to the islets had occurred. One might also speculate that the prepubertal milieu is more protective of transplanted islets than that of puberty when greater insulin resistance is present.

These data support considering TP-IAT early in the course of pediatric CP. It would help to have definite parameters for the procedure, which currently are based on clinical course. Fine-needle pancreatic biopsy under endoscopic ultrasound guidance is a promising tool for early diagnosis or assessment of CP because gross pancreas morphology can be correlated directly with histological findings.23 However, we could find no study that correlated the severity of the clinical syndrome of CP with the severity of the gross morphologic or histopathologic condition of the pancreas.

We found no statistical difference in the degree of histological changes between the pancreases of children who were on narcotics versus those who were not on narcotics preoperatively. These findings suggest that severity of pain is not a good predictor of the extent of damage to the pancreas. In fact, a group of adult patients with severe pain and minimal pancreatic changes have been described.24

Unexpectedly, nesidioblastosis was more commonly seen on pathologic examination in the adolescent (age, ≥13 years old) subjects with low islet yields (<2000 IE/kg). Thus, nesidioblastosis is not a marker for available newly formed islets but rather reflects severe islet damage and portends low yield. Laidlaw25 coined the term nesidioblastosis in 1938 to describe diffuse or disseminated clusters of pancreatic islet cells arising from pancreatic ducts or ductules, and it has been used to designate the morphologic features in cases of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy.26,27 Nesidioblastosis with euglycemia has been observed in the pancreas of patients with severe CP21 and cystic fibrosis28 and in normal pancreases of neonates29 and adults.30 Autopsy studies of children with cystic fibrosis show prominent new islet formation, but this capacity is lost by adolescence.31 Only 2 preadolescent subjects in our series had nesidioblastosis: 1 had a yield less than 2000 IE/kg, and cystic fibrosis was the underlying pancreatic disease in the other. Thus, in our series, nesidioblastosis was most prominent among older children with CP and reflected severe damage to the pancreas from the ongoing pathologic process.

In conclusion, the likelihood of a diabetes-free outcome in children undergoing TP-IAT for CP is related to the number of healthy islets recovered. The greater the degrees of pancreas fibrosis and atrophy are, the longer the duration of the disease, and older age all reduce islet yield. Our data suggests that TP-IAT should be considered early in the course of painful CP that persists after medical or endoscopic interventions and that surgical drainage procedures should be avoided to maximize the number of islets available. This recommendation is particularly germane for children with hereditary forms of pancreatitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Mary E. Knatterud for editing the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry, the General Clinical Research Center at the University of Minnesota, the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International, the Indirect Cost Recovery Fund, and the JB Hawley Student Research Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warshaw AL, Banks PA, Fernandez-Del CC. AGA technical review: treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(3):765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buscher HC, Jansen JB, van Dongen R, et al. Long-term results of bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2002;89(2):158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dite P, Ruzicka M, Zboril V, et al. A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35(7):553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356(7):676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frey CF, Suzuki M, Isaji S, et al. Pancreatic resection for chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1989;69(3):499–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz JS, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Failure of symptomatic relief after pancreaticojejunal decompression for chronic pancreatitis. Strategies for salvage. Arch Surg. 1994;129(4):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson A, Kobayashi T, Sutherland DER. Islet autotransplantation to prevent or minimize diabetes after pancreatectomy. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2007;12(1):82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, Najarian JS. Pancreatic islet cell transplantation. Surg Clin North Am. 1978;58(2):365–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blondet J, Carlson A, Kobayashi T, et al. The role of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(6):1477–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahoff DC, Paplois BE, Najarian JS, et al. Islet autotransplantation after total pancreatectomy in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(1): 132–135; discussion 135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farney AC, Najarian JS, Nakhleh RE, et al. Autotransplantation of dispersed pancreatic islet tissue combined with total or near-total pancreatectomy for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1991;110(2):427–437; discussion 575–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahoff DC, Papalois BE, Najarian JS, et al. Autologous islet transplantation to prevent diabetes after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 1995;222(4):562–575; discussion 575–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jie T, Hering BJ, Ansite JD, et al. Pancreatectomy and auto-islet transplant in patients with chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(suppl 3):S14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland DER, Gruessner AC, Carlson AM, et al. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation. 2008;86:1799–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellin M, Carlson A, Kobayashi T, et al. Outcome after pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakao A, Fernandez-Cruz L. Pancreatic head resection with segmental duodenectomy: safety and long-term results. Ann Surg. 2007; 246(6):923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Scharp DW. Automated islet isolation from human pancreas. Diabetes. 1989;38(suppl 1):140–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manciu N, Beebe DS, Tran P, et al. Total pancreatectomy with islet cell autotransplantation: anesthetic implications. J Clin Anesth. 1999; 11(7):576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloppel G Chronic pancreatitis of alcoholic and nonalcoholic origin. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2004;21(4):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard JM, Nedwich A. Correlation of the histologic observations and operative findings in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;132(3):387–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloppel G, Bommer G, Commandeur G, et al. The endocrine pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural studies. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1978;377(2):157–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Dunn DL, et al. Transplant options for patients undergoing total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):559–567; discussion 568–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iglesias-Garcia J, Abdulkader I, Larino-Noia J, et al. Histological evaluation of chronic pancreatitis by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy. Gut. 2006;55(11):1661–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh TN, Rode J, Theis BA, et al. Minimal change chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1992;33(11):1566–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laidlaw GF. Nesidioblastoma, the islet tumor of the pancreas. Am J Pathol. 1938;14(2):125–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heitz PU, Kloppel G, Hacki WH, et al. Nesidioblastosis: the pathologic basis of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in infants. Morphologic and quantitative analysis of seven cases based on specific immunostaining and electron microscopy. Diabetes. 1977; 26(7):632–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sempoux C, Guiot Y, Dubois D, et al. Pancreatic B-cell proliferation in persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy: an immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. Mod Pathol. 1998; 11(5):444–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown RE, Madge GE. Cystic fibrosis and nesidioblastosis. Arch Pathol. 1971;92(1):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould VE, Memoli VA, Dardi LE, et al. Nesidiodysplasia and nesidioblastosis of infancy: structural and functional correlations with the syndrome of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Pediatr Pathol. 1983;1(1):7–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouwens L, Pipeleers DG. Extra-insular beta cells associated with ductules are frequent in adult human pancreas. Diabetologia. 1998; 41(6):629–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iannucci A, Mukai K, Johnson D, et al. Endocrine pancreas in cystic fibrosis: an immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1984; 15(3):278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]