Abstract

Background

Child protection is and will be drastically impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Comprehending this new reality and identifying research, practice and policy paths are urgent needs.

Objective

The current paper aims to suggest a framework for risk and protective factors that need to be considered in child protection in its various domains of research, policy, and practice during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Strategy

From an international collaboration involving researchers and child protection professionals from eight countries, the current paper examines various factors that were identified as playing an important role in the child protection system.

The initial suggested framework

Through the use of an ecological framework, the current paper points to risk and protective factors that need further exploration. Key conclusions point to the urgent need to address the protection of children in this time of a worldwide pandemic. Discussion of risk and protective factors is significantly influenced by the societal context of various countries, which emphasizes the importance of international collaboration in protecting children, especially in the time of a worldwide pandemic.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed the urgent need to advance both theory and practice in order to ensure children's rights to safety and security during any pandemic. The suggested framework has the potential to advance these efforts so that children will be better protected from maltreatment amidst a pandemic in the future.

Keywords: COVID-19, Child maltreatment, Child protection

1. The current paper context and aims

The COVID-19 pandemic has had worldwide and far-ranging impacts. As societies struggled to contain infection as their primary goal, questions arose as to the consequences, many unintended, for children and families. An informal working group of international researchers and child protection professionals from eight countries (Brazil, Colombia, Canada, Israel, South Africa, Uganda, United Kingdom, and the United States) came together to consider the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child maltreatment (CM). The current paper illustrates the key issues that were identified in the discussion among the countries both within each country but also were found relatable and relevant to the international discussion. The aim of this international discussion platform was to generate an initial framework for possible risks and protection of children from maltreatment during COVID-19. This initial suggested framework wishes to further advance research, policy and practice about the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on CM. While there are currently inadequate data to draw firm conclusions, this is an opportunity to build practice and policy addressing CM, built on and informed by world-class research.

The current paper integrated a modified ecological model (National Research Council, 1993), familiar in the field of child development and CM, to offer a framework for understanding the impact of COVID-19 on risk and protective factors related to CM. It aims to do so across interrelated ecological levels of the individual and interpersonal interactions, the neighborhood and communities, and broader societal and cultural contexts. The current paper seeks to advance the development of a framework to understand, assess and approach risk and protective factors in children’s lives throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, both when quarantine and lockdown are mandated and during the period of re-integration, when children and families return to the “new normal/routine” after quarantine/lockdown is lifted.

2. Background and rationale

On 11 March 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. The United Nations Framework for the Immediate Socio-Economic Response to COVID 19 (United Nations, 2020) concluded that the worldwide pandemic is not only a health crisis but is affecting economies and societies at their core (Fernandes, 2020). In this regard, scholars worldwide argue that children are at significant risk for maltreatment due to increased rates of poverty, food insecurity, unemployment, and inequalities (Fore, 2020; Van der Berg & Spaull, 2020). Suggestions also have been made that CM will increase as children are isolated from adults who provide care and support and also those who have responsibility for reporting CM. As such, a renewed call for research has emerged to inform policy and practice on the influence the pandemic has on CM globally. Although there is abundant speculation about the impact of the pandemic on CM, we have very little reliable, empirical data to support these assumptions. The challenge is to turn good hypotheses into valid and reliable research that will enhance effective protection and intervention with maltreated children and their families. As such, the current paper is cautionary and stresses the need for well-designed research to inform policy and practice, and vice versa.

COVID-19 is not the first pandemic that the world has seen. However what makes it notable is the lockdown regulations that have been imposed in many countries and the resulting potential consequences for children. Under these conditions, children may have been more vulnerable to abusive situations and cut off from potential protective interventions (Van der Berg & Spaull, 2020). Assessing the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on societies, economies and vulnerable groups is fundamental to inform and tailor the responses of governments and partners to recover from the crisis and ensure that no one is left behind in this effort.

The COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to better understand CM through what is termed naturally occurring experiments. There are known dates for emergence and distribution of the virus as well as for changes in policies and practices. Research would, for example, be able to undertake space and time analyses of the effects of policies such as school closings and openings on CM and the various mechanisms involved (e.g. parental stress, parental unemployment, social cohesion, scrutiny and observation of children by adults charged with reporting, access to services including healthcare). It would also enable us to better explore the interplay between the natural environment (for example air quality, access to clean water) and pathways to addressing CM. Therefore, it is important to analyze the impact COVID 19 has across diverse contexts based on their specific, culturally-contextualized circumstances.

3. An ecological framework for exploring the links between COVID-19 and child maltreatment

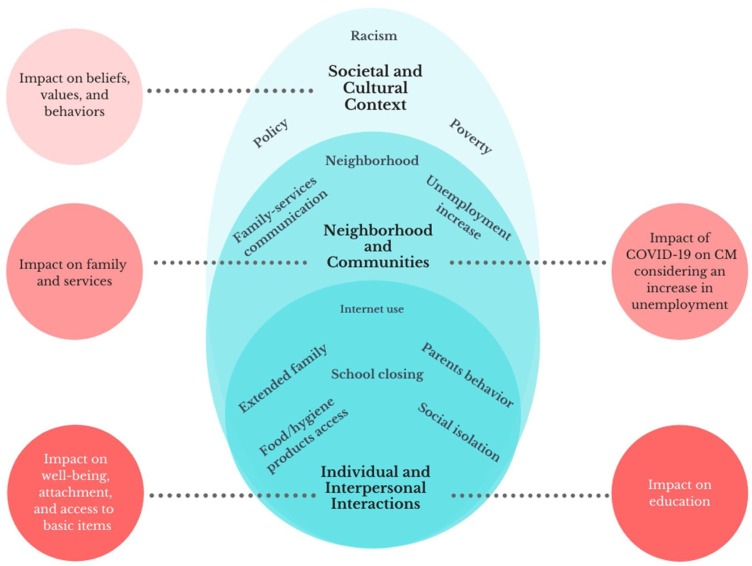

Research supports the conclusion that CM results from a complex interaction of risk and protective factors across ecological levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) ranging from the individual to the larger socio-cultural context (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; see Fig. 1 ). An ecological framework is not in and of itself causal, but points to opportunities for understanding causal paths of interactions across these ecological levels. Ecological models inform our understanding of human developmental processes and organize information in a way that may have an impact on practical and theoretical questions. An ecological perspective can guide the study of risk and protective factors across each these levels and afford a perspective on the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on CM.

Fig. 1.

An Ecological Model for CM and COVID-19.

Considering the current situation still unfolding, the current paper aims to suggest a framework for risk and protective factors that need to be considered in child protection in its various domains of research, policy, and practice during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1. Strategy

Based on the ecological model, each of the authors considered the relevance of each level and overall factors with regards to the context of their country. Next, we present an integrated discussion of these various perspectives, in order to promote the development of an international framework that will advance the protection of children against CM during a global pandemic. Researchers from an international group of scholars for child protection during COVID-19 pandemic from the International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) contributed with information regarding their own country.

3.2. Initial suggested framework

For each of the levels presented in Fig. 1 above, we present the international perspectives offered from the countries involved in this working group.

3.3. The individual level and interpersonal interactions

In this section we will focus on main factors that affected children during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors present common challenges that arose across the countries, and their unique characteristics regarding child protection. Current knowledge suggests that children have lower chances of severe forms of COVID-19 infection and symptoms and better prognosis (Ludvigsson, 2020). Whether this turns out to be the final outcome of the pandemic remains to be seen, but currently children are viewed as presenting infection risk to the adults with whom they interact, notably their elderly relatives. This, of course, does not mean that they are free of biological, psychological and social consequences from the virus. Additionally, as is the case with CM more generally, the impact of COVID-19 on children may vary by categories including age, gender, developmental disabilities, and prior experience of adversity and abuse.

Children of preschool age may be at greater risk for CM given their dependency on their parents and caregivers and the challenges of this developmental stage. Around the globe, parents are the primary perpetrators of violence against children, and child physical and sexual abuse are the main reasons for children entering the child protection system (Devries et al., 2019; Waiselfisz, 2015). Victims of CM disproportionately exhibit a range of adverse outcomes during childhood and adulthood including physical injury, physical and mental health problems, as well as an increased risk of substance use (e.g., Afifi et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2014; Norman et al., 2012). In addition, exposure to violence during childhood has been linked to a wide range of violence perpetration and victimization in adulthood (Stith et al., 2000). Therefore, it is important to analyze the COVID-19 crisis from this perspective, since children are a greater risk of these outcomes based on the current situation.

From the Israeli perspective, preschoolers have been one of the most disadvantaged and overlooked groups of children during routine times, which has been intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preschoolers from the age of 3 months to 3 years of age do not have standardized childcare arrangements. Parents must find their own childcare which means that it is sometimes expensive and unsafe. From the age of 3–6 children are supposed to be cared for in nurseries, but these are not monitored or supervised by the education office in Israel. This has meant that during the COVID-19 pandemic, babies and toddlers continued to be “undocumented” residents in Israel rendering them and their parents unaccounted for. In Quebec, Canada prior to COVID-19, preschools and childcare were supervised. However, the consequences of the pandemic were damaging for them as closing of all daycare centers and schools meant that children went from formal child care arrangements to being with their parents full-time.

In South Africa, young children were particularly disadvantaged as a result of the government’s (National Department of Social Development DSD) inability to adequately decide on and communicate the status of Early Childhood Development Centers (ECDs). In addition to providing stimulation and access to education, these centers act as safe places for millions of children. The DSD took 3 months following the nationwide lockdown to decide on whether these ECD’s would be re-opened and concluded that ECD’s would remain closed, even after the country moved to Level 3 lockdown measures. This decision was met with much resistance and legal action was taken. During Level 3, many sectors were reopened which meant that children would be left alone, without supervision and care. The courts decided in favor of re-opening these schools, if all necessary safety precautions were taken.

Children of all ages but mainly adolescents spent more time on the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase in online time must be monitored for two main reasons: 1) to avoid the stress of inaccurate and attention-grabbing (“click-bait”) posts or news that increase anxiety with inaccurate or false information; and 2) increased risk for online child sexual abuse (UNICEF, 2020a, Huremovic, 2019, 2020b). Practitioners in the various countries working with families have mentioned the latter to be an important parental concern. Access to screen time as well as access to the internet, seem to be the two preoccupations. In Israel there is a national center for handling children’s safety online, and according to their reports there were twice as many referrals to the center during the COVID-19 pandemic than in the parallel month the previous year.

On the other end of the spectrum, children in Uganda have limited access to the internet. During the COVID-19 pandemic children had limited access to learning which was being delivered virtually. Attending school in person was the only way for many children to have their educational rights met. With the closure of schools, and with the option for virtual learning out of reach for the majority, children’s rights to education were reduced. Additionally, proposed lessons delivered on television or radio programs are largely accessible only by urban based children. The majority of the children in Uganda live in rural settings without access to electric power, radios or televisions. Many children are left staying at home without the possibility of home learning. At the same time, they are doubly exposed to potential overwork given the chores and laborious but necessary tasks including domestic water collection, farming, and household chores.

As with Uganda, in South Africa, not all children have had equal access to education during the lockdown. While some children (a minority) were able to continue with online learning, for most children this was not possible. Pre-existing structural challenges means that the majority of children do not have access to mobile phones, computers and/or data to access educational opportunities. Many public schools were not equipped to deliver this form of learning. Measures were taken by the Department of Basic Education to ensure that children had access to some learning through community radio and television. It is unclear whether it has been useful. While schools are re-opening gradually through a phased in approach, with certain key grades beginning first, this has been hampered by inadequate preparation, lack of protective equipment for both teachers and learners as well as teacher trade unions insisting that schools remain closed until the peak of the epidemic has passed. During this period, children in private schools have had access to online classes and many schools have re-opened. The differences in access, widens the socio-economic divide in the country.

In countries with high inequality also face this divide regarding school access during the quarantine and must put efforts to provide education for all its children. This international discussion on internet exposure stresses its potential risk and protective factors for children. Despite differences among the countries, most of them aimed at school-closures and online education, with some returning to normalcy after the first wave of infections. Class returns must follow health experts’ protocols and provide all necessary measures for safety. Those aspects can be harder to achieve on countries already struggling with educational issues, as cited above. Child protection professionals must enforce and ensure that all safety measures are in place not just for children's physical, but mental wellbeing as well in this return. Along with the embedded risk in the exposure to the internet, the examples that were given by Uganda and South Africa with respect to the internet’s central role to ensure children’s right to education points into its potential role as protective factor. Not only that, but future studies also should consider the way internet exposure during lockdown and worldwide pandemic might impact children's wellbeing. Given the impact that COVID-19 and the forced shut down might have on family dynamics and stress, it might be that the exposure to internet has a beneficial impact on child well-being, serving as a safe place or an outlet for social interaction.

Comprehensive child protection is not possible without acknowledging gender inequality. Before the COVID-19 crisis, the situation of women and girls in Latin American countries (LAC) was already difficult. Inequality has put women at greater risk for poverty. For example, 40 % of rural women over the age of 15 do not have their own income (FAO, 2017). Further, there are important gender gaps regarding education, family structure (1 out 3 households are headed by a woman), and career opportunities (Marchionni, Gasparini, & Edo, 2019).

These differences often have an impact on intimate partner violence (IPV; McKay, 1994; Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, 2014). Before COVID-19, it was estimated that in the LAC region, 1 out 3 women aged 15–49 years had experienced physical or sexual violence from their partner (Bott, Guedes, Ruiz-Celis, & Mendoza, 2019). In Colombia, during the lockdown enforced by the government to face COVID-19, the number of calls reporting domestic violence increased 150 % and 169 women were murdered (Observatorio Feminicidios Colombia, 2020; Observatorio Mujeres, 2020). As indicated by Van Gelder et al. (2020), while the private aspect of IPV and its, unfortunately, low priority for many governments was a barrier before the pandemic, it might further endanger women and children in quarantine times without a concentrated effort on awareness and action. In Israel as well, during the enforced quarantine, domestic violence reports increased in 600 % and six women were murdered (Levi & Katz, 2020). These initial reports on increased rates of IPV during COVID-19 should be further explored, as it is a known risk factor for maltreatment (McGuigan & Pratt, 2001) and trauma symptomology among children (Evans, Davies, & DiLillo, 2008).

Additionally, children with developmental disabilities, who are at increased risk of maltreatment (Jones et al., 2012; Kendall-Tackett, Lyon, Taliaferro, & Little, 2005), also are at increased risk of maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Israel, during the COVID-19 pandemic there was no standardized support for children with developmental disabilities and their families. Additionally, their routine support was taken away from them creating often a regression in these children's conditions which often results in intense stress for their parents and families. In Uganda, a recent vulnerability assessment (Giles-Vernick et al., 2019) revealed that children with various learning and physical disabilities were at increased risk of missing routine services since most of them were not in residential care programs. With the quarantine, restrictions on or a total ban on movement in extreme cases, children were missing out on their daily routine care. For instance, some children who require caretakers to move with them were reportedly unable to be transported with the ban on passengers on ‘boda boda’ (motorcycle taxis).

Adding to these contexts of age, gender and developmental disabilities, it is crucial to discuss the context of prior experience of adversity and abuse. Dysregulation among multiple stress response systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary –adrenal axis, and sympathetic nervous system are frequently observed following childhood adversity like maltreatment (Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006). These alterations are considered as the principle pathways driving risk of psychological disorders into adulthood among both male and female victims (Tiwari & Gonzalez, 2018). While COVID-19 may represent a chronic stress experience for children, it is unclear what the short- and long-term implications of isolation, quarantine and associated environmental adversity will be on stress physiology. It is plausible to believe, however, that the interactions among existing and new psychosocial disruptions following the pandemic will increase risk of maltreatment, and consequently, biological vulnerability and risk for psychopathology.

Prior studies illustrate that higher parental sensitivity to child cues may predict lower stress reactivity recovery among children (Hibel, Granger, Blair, Cox, & Family Life Project Key Investigators, 2011; Laurent, Harold, Leve, Shelton, & Van Goozen, 2016). While unintentional, the circumstances and consequences of the pandemic and resultant lockdown rules may affect parental care. The absence of quality parenting among young children could result in an adaptive stress response among children and have long-term implications for stress reactivity to future psychosocial stressors. Biological vulnerability is a complex matter requiring in depth study. For the purpose of this paper, however, we limit our discussion to this brief section to draw attention towards an integrative approach to study changes in stress physiology in the context of CM and COVID-19. Studies on biological embedding and stress trajectories among children of current high-risk families, and now many others, will be needed now more than ever.

In this context it is important to highlight that the 24/7 exposure of children to parents will be new to both children and parents. Major adjustments will have to be made by both children and parents to ensure some level of harmony in interactions and to preserve relationships. This is more complex in some family settings, such as homes at risk for psychosocial reasons. The duration of these adjustments may well have an impact on emerging child outcomes. Whereas in some contexts it may be highly beneficial for children to increase their contact with their parents, where parents are at risk, this increased exposure may lead to deleterious effects and may increase the chances of being exposed to maltreatment.

Considering family relationships in the context of COVID-19, it is essential to examine the pandemic of COVID-19 on children`s attachment. Maltreatment certainly leads to different forms of insecure and disorganized attachment, but the relation is not linear nor the same with both parents (e.g., Morton & Browne, 1998). As presented earlier, the lack of physical and social contact can harm the mental health of adults and children during quarantine. Investigating how this affects the bond with extended family members is a key consequence of this pandemic that needs clarification; especially how maltreated children experience the lack of physical contact and the long-term effects, which must be part of a research agenda.

In some communities, technologically-mediated contact provided by tools such as social media or communication apps could foster this bond (Levine & Stekel, 2016). In the United Kingdom the role of ‘digitally-mediated safeguarding’ has arisen as a fundamental concept for understanding the spaces across and between ecological levels. Digitally-mediated safeguarding in the UK has provided early examples of cross-sectoral practice in both identifying and reporting CM, and also in intervention delivery.

Despite these pockets of advances and because of new social conditions in response to the pandemic, there remains a clear lack of empirical data regarding attachment, social isolation, and child development. One analogy might be made with long-term hospitalization that can increase isolation feelings in children that can be diminished with technology (for an example see Antón, Mana, Munoz, & Koshutanski, 2011). Future investigations might approach how the use of digital technologies impact feelings of isolation with children and adolescents, and also how they can sustain or deepen bonds with significant members of family and friends, or service providers (such as teachers or social workers). Finally, a research agenda must include how attachment with maltreated children will be affected after social isolation and the possible long-term effects.

Elaborating on the central role of relationship for children’s mental health and development, it is of crucial importance to delve into the impact of COVID-19 and the social isolation on families. Although paramount to public health prevention, guidelines on shelter-in-place and quarantine have placed new constraints on family functioning, with families spending as much as 24 h per day in the home environment (Wang et al., 2020). Increased time at home, with potential economic stressors related to loss of income and/or unemployment and little access to external social support may intensify conflict and tensions within the home. A recent review on the psychological impact of quarantine offers insights on plausible effects of restrictions, describing heighted trauma related distress, confusion, and anger among both children and adults (Brooks et al., 2020).

Given that parents are the primary perpetrators for CM (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2020) it is of crucial importance to dedicate the resources of policy makers and practitioners to the ecological level that encompasses the family. Within the household, parents are facing new demands with meeting basic and educational childcare needs and working remotely within in the home environment. Conversely, parents may also contend with the consequences of unemployment while still being responsible to meet their children’s needs. As a result, these pressures may increase parental stress and subsequently reduce the quality of parent child interactions (Deater-Deckard, 2004). Although limited data are available on the effects of the pandemic on households, one recently published study among caregivers by Brown, Doom, Watamura, Lechuga-Pena, and Koppels (2020) provides early evidence of such risk, demonstrating associations between parental reports of increased family disruptions associated with COVID-19 and higher levels of parental internalizing symptomology, parental stress and risk of child abuse perpetration.

The pandemic may also amplify the risk of CM within existing high-risk parent households. At-risk parents themselves experience deficits in executive functioning, and emotion regulation that amplify negative parenting behaviors (Crouch et al., 2019; Whitaker et al., 2008; Hiraoka et al., 2016; Sidebotham, Golding, & ALSPAC Study Team, 2001; Stith et al., 2009). In an initial assessment conducted in Israel among vulnerable families (Levi & Katz, 2020), parents struggling with parenting during daily routines found the quarantine to be a continuous trauma, triggering perceptions of loneliness, uncertainty, and fear of the unknown, all together escalating parent mental health symptomology. The parents described a strong struggle to survive given the repeated flashbacks they experienced which made it, sometimes, impossible to take care of their children. The extended periods of isolation and quarantine could contribute to further dysregulation in parent sensitivity and consequently increase the potential for family violence.

Caregivers and children are facing a unique challenge with the COVID-19 pandemic that can lead to a range of lasting consequences (Brooks et al., 2020).The long-term duration of quarantine can lead to poorer mental health outcomes. A Canadian study with health professionals shows that quarantines exceeding 10 days have negative consequences with challenges created by the lack of social and family contact (Hawryluck et al., 2004). All but one publication reviewed by Brooks et al. (2020) had adults as participants, indicating the lack of investigations about the impacts of quarantine on children, especially maltreated children. The literature lacks evidence on how children respond to the lack of family contacts while quarantined, especially in long duration quarantines, as has been in most countries. Sprang and Silman (2013) used parents’ information regarding their own children’s PTSD and pandemic-related information regarding H1N1 and SARS. Those authors indicate that children in isolation or quarantine have more PTSD symptoms when compared to general databases. It is important to understand if quarantine and CM can have an amplifying effect on the already reported CM effect on PTSD (Messman‐Moore & Bhuptani, 2017; McTavish, Sverdlichenko, MacMillan, & Wekerle, 2019), or whether the children in isolation/quarantine were already at higher risk of PTSD. Despite Sprang and Silman (2013) not directly investigating the children's mental health outcomes in the long-term, their study provides important cues for future research in a post-pandemic world.

Within the family dynamic, caregiver-level influences may also buffer against the ill effects of the pandemic. For example, Brown, Doom, Watamura, Lechuga-Pena, and Koppels (2020)) documented the positive potential of both parental perceived control over the pandemic and parental supports on risk of maltreatment perpetration. Recent evidence also suggests that parental warmth is a common cross-cultural factor protecting against a range of internalizing and externalizing symptoms among adolescents (Rothenberg et al., 2020). Going forward, such factors will be important targets for services among families. Effective prevention and intervention efforts, which strengthen positive parenting behaviors and foster parent-child relationships, will help improve family capacity during such times of heightened stress.

3.4. The neighborhood and community

There is an abundance of evidence that neighborhood conditions including structural factors and relationships among neighbors influence CM (e.g. Coulton, Crampton, Irwin, Spilsbury, & Korbin, 2007). Neighborhood and community level factors overlap with those at the individual and relationship level and also at the broader societal and cultural level. Structural characteristics of neighborhoods include demographic factors that are easily measured through census or Earth observation data. Multiple structural characteristics of neighborhoods have been investigated in relation to maltreatment, including economic disadvantage (poverty, unemployment, single-headed households), residential instability (percent of residents that are new to the neighborhoods, renter-occupied housing units, vacant housing units), ethnic heterogeneity (percent immigrants within the neighborhood, percentage of various racial and ethnic groups), and child care burden (ratio of children to adults, ratio of younger adults versus elderly) (Maguire-Jack, 2014). Although there have been some mixed findings on these structural characteristics, economic disadvantage has been found to be related to maltreatment across a variety of studies, using various child maltreatment measures and samples (Maguire-Jack, 2014).

In addition to structural characteristics, process factors are also investigated for their relation to maltreatment. While structural characteristics are composite demographic rates, process factors relate to the interactions within neighborhoods between residents and between residents and their environment. Social cohesion (the bond and trust between neighbors) and informal social control (the willingness of neighbors to intervene when they observe social problems) are two factors that are commonly investigated for their relationship with child maltreatment (Coulton et al., 2007). Social cohesion has been found to be particularly protective against child maltreatment (Maguire-Jack & Showalter, 2016), while the findings on informal social control have been more mixed (Emery, Trung, & Wu, 2015). Social cohesion has also been found to serve as a mediator between neighborhood poverty and child neglect (McLeigh, McDonell, & Lavenda, 2018).

Three pathways have been proposed for how neighborhoods and communities influence CM (Coulton et al., 2007). These pathways can lead to child maltreatment behaviors in and of themselves which may go largely unmeasured without self-reports and/or to official child maltreatment reports which is the more usual measure of child abuse and neglect incidence and prevalence.

3.4.1. Neighborhood pathway 1: behavioral influences

This causal pathway is one in which neighborhood structural factors (e.g. poverty, demographics, residential stability) influence social processes (collective efficacy, social organization, community resources and deficits) that might be mediated (e.g. by social support or environmental stressors) and then lead to maltreating behaviors. In the context of COVID-19, periods of quarantine may affect this pathway in a multitude of ways. As families are spending a much greater quantity of time within their local neighborhood the relative importance of the neighborhood may be significantly increased. Additionally, economic downturns as a result of inability to work may increase rates of poverty within the neighborhood. Similarly, in the United Kingdom lack of access to green space for families living in high-rise blocks and over-crowded conditions are hypothesized by practitioners to have impacted on family stress levels, and subsequent CM. In terms of the interactions within neighborhoods, residents may have more time and ability to intervene in problematic situations, by virtue of spending more time within the neighborhood. However, the willingness to interact and intervene with neighbors may be decreased as a result of concerns about social distancing.

3.4.2. Neighborhood pathway 2: definition, recognition and reporting

This causal pathway suggests that there are neighborhood conditions that influence how maltreatment is defined and thereby recognized and reported. This pathway leads to child maltreatment reports but not necessarily to child maltreatment behaviors that may go unreported. This pathway is important because so much of the literature is based on reports of child maltreatment to relevant agencies. This pathway may be subject to bias and questions of increased scrutiny versus increased stress in the literature. This pathway also reflects the importance of understanding different categories of reporters, for example mandated reporters (physicians, teachers) as opposed to non-mandated reporters (friends, family members).

While reliable data are not yet available, some preliminary reports have suggested that CM reports have decreased, sometimes dramatically, as a result of COVID-19 related actions such as closing schools, daycares and other child facilities and stay at home orders in various states in the U.S (Whaling et al., 2020). This pathway is based on a reliance of scrutiny and observation of children with the decision made to report. It would be important to know if reports have changed among mandated (teachers, physicians, child welfare professionals, etc.) versus non-mandated reporters (neighbors, family members, etc.) and what factors can be associated with these changes.

It is interesting to elaborate that in Israel, many grassroots initiatives were generated during COVID-19, although these were mainly targeted at the elderly who were the focus for the public discourse. Children were regarded as an irrelevant population in Israel during COVID-19 perhaps that can explain why most of the grassroots initiatives did not consider children as a group who in need for informal support.

3.4.3. Neighborhood pathway 3: selection Bias effects

The third causal pathway that links neighborhoods to CM reflects how families select or otherwise come to live in their neighborhoods. In essence, it is a form of selection bias: maltreating families “self-select” to specific neighborhoods. This selection process is not well understood and may result from a number of factors including availability of affordable housing, presence of relatives in neighborhood/community, or the quality of schools or other services. The decisions about where to live may vary widely by income and by racial segregation. This pathway presents a challenge in not knowing the reasons that groups of neighbors find themselves living in proximity (Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Recent attention to structural racism that has restricted residential choice through such mechanisms as “redlining” in the United States (selective denial of mortgages and other housing support in targeted geographic areas or neighborhoods) has resulted in underrepresented minority populations being restricted in residential choice with implications for the quality of neighborhood resources available to them (Maguire-Jack et al., 2020).

The impact of this pathway under COVID-19 may be profound but difficult to measure. While nations have instituted different “safety nets” for their populations, the conditions of the pandemic could exacerbate selection effects – for example COVID-related policies to shelter at home could increase unemployment and increased evictions thereby ultimately increasing the number of income-insecure families moving to a given area.

3.5. Societal and cultural contexts

In this level the discussion will address the following domains as central to the understanding of COVID-19 on risk and protection of children. The first is the presence or absence of policy with respect to the protection of children during COVID-19 as well as the impact of media. The second addresses social dynamics within various societies with specific focus on racism and its potential adverse impact on children and their families. And the third domain relates to poverty as a core context to examine in the unique context of COVID-19 as a worldwide economic crisis.

3.5.1. Policy towards welfare and children during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic surprised many countries worldwide with an unknown virus and new regulations such as forced quarantine with its impact on the economic and health situations in these countries. The issue of children’s welfare, unfortunately, was not identified as a top priority in many countries and policy guidelines did not address or overlooked the issue of protecting children from maltreatment and child protective services availability during the pandemic.

In South Africa, social workers were not considered essential workers in the beginning of lockdown and therefore could not deliver services (Rasool, 2020). As levels of lock down were eased, social workers could slowly return to work under different regulations and according to new office specific guidelines (e.g. younger and healthy social workers did home visits and older at-risk social workers wrote reports from home). Anecdotal reports indicate that many social workers refused to work, while others were very reluctant to work. As such, many children were at greater risk, because not only was the ability of community members to report maltreatment possibly restricted, (many South Africans do not have cellphones, or enough data or airtime to call or text child abuse hotlines or social workers), but also, many (not all) representatives of their ecology mandated to protect them (i.e. social workers), were unsupported, unwilling or hesitant. Furthermore, anecdotal reports revealed that some registered designated child protection organizations had still not received their much- needed funding from government even before lockdown, and reportedly, many continued to receive no funds during lockdown; likewise, Child and Youth Care Centers’ registrations were not renewed and some of them have also not received funding. This all made effective service delivery, especially under very restrictive lockdown conditions, almost impossible.

In the UK social workers were defined as key workers, but lack of adequate testing and access to personal protection equipment, along with changes in the definition of ‘vulnerable’ children caused initial confusion. The British Association of Social Workers produced practice guidelines for practitioners as early as 3 April 2020, and have continued to update these regularly, but what has been lacking has been intersectoral guidance that goes beyond definitions for identification or treatment.

In Colombia some of the major adjustments made by CPS were forbidding all family visits and family interventions, prioritizing online or telephone meetings/interventions, postponing non-urgent medical appointments and suspending new adoptions processes (ICBF, 2020). These measures were held for almost 3 months and children in foster care had little or non-contact with their families during this period of time.

In Israel, the government’s initial response to COVID-19 was defining social workers as not essential, therefore removing from children and their families all the support that was provided for them routinely (Katz, 2020; Levi & Katz, 2020). Additionally, several residential care facilities in Israel were closed during the quarantine, which meant that many children were suddenly returned to their unsafe homes with no support and no supervision. This initial response which dramatically escalated the risk for children was responded to by child advocates in Israel with intensive media campaign which aimed to raise the awareness for children's safety during COVID-19. After five weeks, policy in Israel started to change and CPS workers were allowed to get back to work (Katz, 2020; Levi & Katz, 2020).

In South Africa, children’s rights groups have been very active during this period; they’ve advocated for an increase in the Basic Child Support Grant as well as other social welfare grants, they have also instituted legal action against the government in terms of both the re-opening of ECDs as well as in the re-instatement of the Nutritional School feeding scheme. Children and youth care centers have continued on despite interruptions in government funding and have made alternate plans to ensure that children in care are safe.

These initial examples from various countries illustrate the importance of continuing to explore child protection policy at the international level. It might be that some countries actively addressed the protection of children in their policies which might be a good starting point to further elaborate and expand to additional countries.

One noteworthy point relating to social and cultural domains in the context of child protection during COVID-19is the interplay between the natural environment and the physical and mental health of children and their families. Recent research has documented the links between air quality and the respiratory impacts of COVID-19 (Fattorini & Regoli, 2020; Isphording & Pestel, 2020), indicating that chronic air pollution, for example, is correlated with higher infection rates. Similarly, resilience science has in recent years begun to articulate the links between the natural environment, the socio-cultural importance of the environment, and risk/protective factors – (e.g. Faulkner, Brown, & Quinn, 2018; Ungar & Theron, 2020). While we are just beginning to understand the relationships between these dimensions, we note the importance of the natural environment in our model here, and the significant opportunities afforded by interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research in coming years. By working in collaboration with earth observation sciences, life sciences, artificial intelligence, ethics, and others, and ensuring we work in decolonizing ways that place children and young people at the heart of our research, we can begin to ensure that every resource is maximized for children’s safety and wellbeing in the future.

3.5.2. Racism

The forced quarantine and the context of social isolation that characterized many countries during COVID-19, might have the potential to escalate negative social dynamic within societies, mainly given the competition for limited resources in such a stressful economic and health time.

Ethnic minorities and those of African descent struggle with discrimination all over the world. Race discrimination affects aspects such as employment, income, health, education, and housing. One important example is the health disparities among population groups which are the consequence of complex dynamics between social exclusion, poverty, adverse environmental factors, and cultural/behavioral factors (Giuffrida, 2010). For instance, the Covid-19 mortality rate among Black Americans is not only the highest in the USA, but it is about 2.3 times as high as the rate for white people (APM Research, 2020). As per race and child protection services, research has found that black children are involved at approximately twice the rate of white children in cases of child abuse and neglect. Nonetheless, results based on national child abuse, neglect and child health data in the USA showed that the increased exposure to risk factors such as poverty was a significant factor, rather than racial bias in reporting (Drake et al., 2011). In Latin America, children from ethnic minorities experience high levels of poverty, well above white children (CEPAL, 2014) and they are already overrepresented in protection institutions all over the region (UNICEF, 2013). In Israel, there are several disadvantaged groups and their condition got worse during COVID-19. Israeli-Arabs are routinely disadvantaged and excluded, including CPS resources. This situation was intensified during COVID-19 with more racism and fewer resources targeted towards them. An additional disadvantaged group in Israel is the ultra-orthodox Jewish. During COVID-19 there was a lot of hate and racism towards them, blaming them for spreading the virus. It might be that the social isolation and competition on limited resources contribute to a possible phenomenon of community alienation, this should be the focus for further exploration (Levi & Katz, 2020).

The impact of racism has adverse effects on all involved (Dettlaff, 2020). Children and their families might become more isolated and suspicious towards others which might impact their request for help and CM reports.

Poverty. Economic experts have asserted that COVID-19 will bring the worst economic crisis seen since the great depression of 1930s. The lockdowns enforced by different governments around the world have already impacted the economy, increasing the unemployment rates to excessive levels (Gromada, Richardson, & Rees, 2020; ILO, 2020). This impact will probably be felt strongly by developing countries, including those in Latin America. Before the Covid-19 crisis, this area was already struggling with poverty, being the most unequal region of the World (CEPAL, 2018). A recent analysis by UNICEF (2020a, 2020b) stressed that because of the economic impact of COVID-19 and unless urgent measures are taken, the number of children living in poor households in low- and middle-income countries could reach a total of 672 million, a 15 % increase. Research also warns about a significant increase in child mortality due to COVID-19. An estimative indicates a 10–50 % child mortality increase due to acute malnutrition and lack of access to appropriate health services (Roberton et al., 2020).

This issue also can be seen around the globe. From a South African perspective, it is important to look at how Covid-19 has exacerbated structural inequalities. One of the key concerns related to children during this period is escalating poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition. In a study by Spaull et al. (2020), 7041 South African adults were interviewed using the NIDS-CRAM survey between May and June 2020. The study found that in 15 % of these adults’ lives their children were hungry and 22 % of these adults also were hungry. Child hunger was associated with the loss of a main income, highlighting the impact of a national shutdown on the economy which in turn has affected the wellbeing of children in South Africa. Over 9 million children are dependent on the National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP) (Devereux et al., 2018); with schools closed, they have not been able to access this one meal a day. Aid organizations have been inundated with calls for food hampers – promised by government but not adequately delivered.

South Africa has among the highest rates of stunting in children caused by under nourishment (Zere & McIntyre, 2003), and these figures could increase with the economic difficulties. Furthermore, Early Childhood Development Centers (ECDs) also closed down during the lockdown period, resulting in many children left unattended and unsupervised as a result of their caregivers continuing to work. This pattern is being observed in a wide range of Majority and Minority World countries (Power, Doherty, Pybus, & Pickett, 2020), with foodbanks being overwhelmed with the societal needs across the globe (Nicola et al., 2020). The long-term economic and social impacts of this pandemic are still to be seen, although a social crisis hitting especially the most vulnerable and in countries with weak leadership regarding COVID-19 will probably face longer and worse hardship (Nicola et al., 2020; Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020).

In Canada whole systems are in place to ensure a shared responsibility in responding to children. Those include free medical follow-up from infancy to the end of adolescence, free education, interventions and support for children with special needs, free breakfast and lunches offered at school to children growing up in poverty, social services to support families in need, and some provinces offer subsidized state-run care system for preschoolers. Suddenly, with the social isolation imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, families saw the disappearance of those sources of support and it was now left to them to answer every need of their child. For months, daycare centers and schools were closed, health follow-up was postponed, community organizations were closed, and even the families’ informal support networks of extended family and friends were only available virtually. Parents, many of whom were still working during the pandemic, became the only source of response for all the needs of children. Therefore, by its very nature, the pandemic with its requirements of social distancing and in many cases social isolation became a risk factor for child neglect.

4. Discussion of the potential impact of the suggested framework

The COVID -19 crisis provides an opportunity to consider CM within a broader socioecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Luyten, Campbell, & Fonagy, 2019). Analyzing CM during the COVID-19 crisis could easily lead to simplistic etiological models that unjustly focus on early parent–child relationships during COVID -19 quarantine, neglecting the role of peer relationships, child protection services, the political and economic climate, and the mediating and moderating role of later experiences, as has been found in longitudinal studies (Carlson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2004; Carlson, Egeland, & Sroufe, 2009; Salvatore, Haydon, Simpson, & Collins, 2013).

Child development is deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Professionals, researchers, parents, teachers, and all responsible to act in the best interest of children must unite efforts in the search for the best outcomes during and after this crisis. This paper aimed to be a starting point for research discussions and interventions that might improve the situation for children across the globe. Scientific research yielding empirical data is urgently needed to inform immediate practice.

The initial framework that was suggested and discussed in the current paper started with the discussion of the individual level and interpersonal interactions. Although children are not considered to be a group at high risk for COVID-19 itself, the initial evidence and the former discussion emphasizes the dramatic impact the pandemic and related policies did have on the lives of children worldwide. Policies during the COVID-19 for child protection widely varied across countries and regions. Despite those differences, this paper aimed at providing an overview of variables that can affect CM in different countries. Also, it is unclear how those local policies and health measures affected children in the short and long-term. Researchers and child protection professionals must work together for a better view on the best policies for preventing CM and providing wellbeing for children during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is especially important, considering that many countries might face second and third waves during 2021 and until there is wide vaccination available.

In the various countries preschool children were identified as a specific age group that needs to be further explored, both in research and practice and that it is essential that policy makers dedicate greater resources for protection of this age group. Several aspects were identified in the potential risk for this age group: the withdrawal of day centers, the continuous exposure to a family that might experience stress, and their developing capabilities that require attention and both physical and emotional resources, which might place them at a great risk for CM.

Exposure to the internet can be both risk and protective factors. It is well known that exposure to the internet might put children at increased risk for online exploitation, however, in the current paper two protective factors of exposure to internet were identified. The first one is that during a worldwide pandemic with forced quarantine, internet is key in ensuring children`s rights to education. Digital technology use can also play a central platform for professionals to communicate with children and one another, and provide them with help. It is also important to stress the possibility that in this intensive time of worldwide pandemic, homes can become a stress context; the internet (for those not experiencing digital poverty or exclusion) can offer children a place where they can escape from their problems and find comfort and hope (e.g. through access to education). The framework encourages us to understand digital technologies in more nuanced and culturally-sensitive ways, in operation both within and between levels in the ecological system, and therefore operating as both risk and protective factor for all actors. The future potential and ethical implications for artificial intelligence and machine learning in child protection are only just beginning to be explored; the COVID-19 pandemic invites us to ensure that research surrounding technology-mediated or informed practice benefits all children globally (Leslie, Holmes, Hitrova, & Ott, 2020).

The suggested framework strongly points to gender inequality. The World Health Organization (2020a, 2020b) indicate that domestic violence tends to increase during crises, such as this epidemic. This signals that gender inequality is intensifying during this pandemic and must be recognized in policies and resource allocation. A more systematic exploration of the increase in domestic violence during COVID-19 should be executed, as well as the impact it has on CM and children mental health.

Children with disabilities were identified as high-risk for CM during the pandemic. The routines for these children and their families is challenging during non-pandemic times, and this might intensify during a pandemic in which social isolation, economic distress and withdrawal of professional support might increases the risk for maltreatment. This deserves further exploration in future studies.

The prior experience of adversity and abuse was strongly marked as one with potential impact on the children. Children with prior experiences of trauma may either intensify the stress of COVID-19, or potentially provide greater resilience to deal with the trauma of the pandemic. This should be further explored in future studies.

In the transition to the interpersonal interactions, attachment was identified as a way COVID-19 and the reality it created for many families worldwide as poses a challenge for the relationship between parents and their children. It is clear that the forced stay home restrictions impacted the relationship within the family and between the various sub systems within the family, including the siblings sub system. Further exploration of this aspect of the ecological framework is urgently needed. It is also important to highlight, that for many children the significant others in their life are not only members of their nuclear family, including grandparents, extended family and close friends to the family. The immediate absence of these significant figures for the children given the forced quarantine needs to be further explored and ways to maintain these significant relationships even in time of social distancing should be further explored.

Highlighting the dynamics and relationships within the family, it is crucial to point to the multifaced impact of COVID-19 on families, in which they need to contend with growing economic stress and fears about health and relationships in a context where the family is 24/7 together. This pandemic context creates challenges in addressing the educational needs of children which was the full responsibility of the parents given school shutdowns, to the challenging nature of emotional regulation in this time of uncertainty with a main aim of balancing positive parental behavior with the negative ones. These given challenges for all the families worldwide might be intensified by previous trauma of parents which might be escalated during the pandemic and with adverse effects for mental health of all family members following the stress of the pandemic and the forced quarantine.

At the level of the neighborhood and communities several issues should be further explored and addressed. The first one is that given the shutdown of many formal systems in families’ lives, neighbors have more central role and that needs to be further addressed, especially given the role that neighbors can have in reporting, in protecting children from maltreatment and in providing families with informal support. This pandemic illustrates how future efforts should be targeted in order to advance the development of the processes within neighborhood and communities, stressing its central role in protecting children.

At the third and last level, the suggested framework identified three main factors that need to be highlighted: policy, racism and poverty. Discussing policy, two main conclusions should be drawn. The first is that deficits in protecting children during routine times will only be intensified during worldwide crises such as a pandemic. Therefore, it is essential that along with advancing policy for protecting children from maltreatment worldwide, there will be transparency in the policy with respect to the deficits in existing policy in order for it to receive attention in times of worldwide crisis. The role of, for instance, qualified and seasoned child protection social workers in formulating national responses and strategy developments in times of pandemics, must be prioritized, as these are the experts on the ground level who understand the realities of protecting children and can assist in creating feasible and effective responses. The second conclusion is the crucial role that child advocates have worldwide in protecting children's rights and advancing public awareness and promoting policy changes through media coverage. The examples that were given by several countries illustrated that in times where chaos is taking place, child advocates such as researchers and practitioners have a central role in reprioritizing children’s rights.

A central factor in this level is racism. In all countries there are disadvantaged groups in routine times. The suggested framework emphasizes that the social isolation and the economic crisis that were generated by COVID-19 have a high potential to exacerbate racism towards these disadvantaged groups worldwide, with adverse impacts for both the short and the long term. In the short term it means that these disadvantaged groups will continue to receive less resources which will intensify the risk for children and their families during the pandemic. In the long term, that means that these harsh traumatic experiences of racism will only increase the suspicion and gap between these disadvantaged groups and the formal authorities in the countries, which will result in more closed dynamics within these group, mistrust in the formal authorities and therefore decrease opportunity to protect children and provide families with support.

Finally, the last factor that was discussed in the third level, addresses the risk that poverty holds for the protection of children and supporting families in times of a pandemic. Given the dramatic worldwide economic crisis, it is of crucial importance to delve into the impact both on families who lived in poverty before COVID-19 as well as to new children and families pushed into poverty by the COVID-19 pandemic. This should be further explored for its impact on the relationship within these families as well as to CM.

Researchers should make another important effort in the adaptation and validation of instruments that might provide comparable data across cultures. ISPCAN made some efforts in that direction (Zolotor et al., 2009) with the ICAST, and many countries have validated the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (for an example of a worldwide research see Viola et al., 2016). A few questions arise from this idea of standard instruments across the globe. The first is that how those instruments measure child abuse and how they deal with different local and cultural practices still is unknown. The pandemic raises the importance of having access to highly validated measures that can be used quickly.

A second aspect is that despite the instruments performing better than clinical assessments, there is lack of evidence on how far they can help professionals with case support (van der Put, Assink, & van Solinge, 2017). Those instruments are valuable as comparable measures of prevalence across countries. Mathews, Pacella, Dunne, Simunovic, and Marston (2020)) performed a systematic review regarding national prevalence and found 30 studies from 22 countries. Interesting to identify that only 3 of those were developing countries (Saudi Arabia, Suriname, and South Africa) with a variety of instruments and methods to access that information. These methodological differences make cross-country comparisons difficult. As with many points that are made, COVID-19 makes the issues more salient, but these questions should be systematically addressed on a current, running basis to help us gain greater understanding of child outcome and maltreatment in different parts of the world.

To conclude, the suggested framework stresses the crucial importance of acknowledging the potential risk of COVID-19 to children worldwide, stressing the urgent need to advance the development of theory, the adaptations of policy and the promotion of prevention and intervention programs in order to protect children from maltreatment and to increase support for families. The current paper illustrates the importance of international discussion, as COVID-19 emphasizes the strong connecting that must be enhanced among multiple countries in order to increase the protection of children.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- Afifi T.O., MacMillan H.L., Boyle M., Cheung K., Taillieu T., Turner S.…Sareen J. Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Reports. 2016;27(3):10–18. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2016003/article/14339-eng.pdf Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antón P., Mana A., Munoz A., Koshutanski H. International workshop on ambient assisted living. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2011. Live interactive frame technology alleviating children stress and isolation during hospitalization; pp. 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- APM Research L. 2020. COVID-19 deaths analyzed by race and ethnicity.https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2020. COVID-19: El número de niños que viven en hogares pobres aumentará hasta en 86 millones para finales de este año[COVID-19: The number of children living in poor households will increase by up to 86 million by the end of this year]https://www.unicef.org/es/comunicados-prensa/numero-ninos-hogares-pobres-aumentara-hasta-86-millones Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. COVID-19 and violence against women what the health sector/system can do.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331699/WHO-SRH-20.04-eng.pdf?ua=1 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bott S., Guedes A., Ruiz-Celis A.P., Mendoza J.A. Intimate partner violence in the Americas: A systematic review and reanalysis of national prevalence estimates. Revista Panamericana de Salud PÃoblica. 2019;43:1–12. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2019.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. The American Psychologist. 1977;32:513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-0066x.32.7.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N.…Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.M., Doom J., Watamura S.E., Lechuga-Pena S., Koppels T. Stress ‘and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/ucezm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.A., Egeland B., Sroufe L.A. A prospective investigation of the development of borderline personality symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1311–1334. doi: 10.1017/S0954-579409990174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.A., Sroufe L.A., Egeland B. The construction of experience: A longitudinal study of representation and behavior. Child Development. 2004;75:66–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL . CEPAL; United Nations: 2014. Los pueblos indígenas en América Latina: Avances en el último decenio y retos pendientes para la garantía de sus derechos[Indigenous peoples in Latin America: Advances in the last decade and pending challenges to guarantee their rights]https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/37050/4/S1420783_es.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL . CEPAL; United Nations: 2018. Social panorama of Latin America.https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/44396-social-panorama-latin-america-2018 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D., Toth S.L. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.J., Spencer R.A., Everson-Rose S.A., Brady S.S., Mason S.M., Connett J.E.…Suglia S.F. Dating violence, childhood maltreatment, and BMI from adolescence to young adulthood. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):678–685. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C.J., Crampton D.S., Irwin M., Spilsbury J.C., Korbin J.E. How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(11–12):1117–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch J.L., Davila A.L., Holzman J.B., Hiraoka R., Rutledge E., Bridgett D.J.…Skowronski J.J. Perceived executive functioning in parents at risk for child physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0886260519851185. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0886260519851185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K.D. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2004. Parenting stress. [Google Scholar]

- Dettlaff A.J., editor. Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system. Springer Nature; Heidelberg: 2020. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux S., Hochfeld T., Karriem A., Mensah C., Morahanye M., Msimango T.…Sanousi M. Centre of Excellence in Food Security; South Africa: 2018. School feeding in South Africa: What we know, what we don’t know, what we need to know, what we need to do.https://foodsecurity.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CoE-FS-WP4-School-Feeding-in-South-Africa-11-jun-18.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Devries K., Merrill K., G, Knight L., Bott S., Guedes A.…Abrahams N. Violence against children in Latin America and the Caribbean: What do available data reveal about prevalence and perpetrators? Revista Panamericana de Salud PÃoblica. 2019;43:e66. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2019.66. https://dx.doi.org/10.26633%2FRPSP.2019.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B., Jolley J.M., Lanier P., Fluke J., Barth R.P., Jonson-Reid M. Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):471–478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery C.R., Trung H.N., Wu S. Neighborhood informal social control and child maltreatment: A comparison of protective and punitive approaches. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;41:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S.E., Davies C., DiLillo D. Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2017. Women in Latin America and the Caribbean face greater poverty and obesity compared to men.http://www.fao.org/americas/noticias/ver/en/c/473028/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environmental Pollution. 2020:114732. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner L., Brown K., Quinn T. Analyzing community resilience as an emergent property of dynamic social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society. 2018;23(1) doi: 10.5751/ES-09784-230124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. 2020. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy (March 22, 2020)https://ssrn.com/abstract=3557504 Available at SSRN 3557504. Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Fore H.H. A wake-up call: COVID-19 and its impact on children’s health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2020;18(7):e861–e862. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Vernick T., Kutalek R., Napier D., Kaawa-Mafigiri D., Dückers M., Paget J.…Hardon A. A new social sciences network for infectious threats. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(5):461–463. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida A. Racial and ethnic disparities in Latin America and the Caribbean: A literature review. Diversity in Health and Care. 2010;7(2):115–128. https://diversityhealthcare.imedpub.com/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-a-literature-review.php?aid=2002 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Gromada A., Richardson D., Rees G. Innocenti Research Brief: UNICEF; 2020. ). Childcare in a global crisis: The impact of COVID-19on work and family life.https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IRB-2020-18-childcare-in-a-global-crisis-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-work-and-family-life.pdf Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluck L., Gold W.L., Robinson S., Pogorski S., Galea S., Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(7):1206. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201%2Feid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibel L.C., Granger D.A., Blair C., Cox M.J., Family Life Project Key Investigators Maternal sensitivity buffers the adrenocortical implications of intimate partner violence exposure during early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(2):689–701. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka R., Crouch J.L., Reo G., Wagner M.F., Milner J.S., Skowronski J.J. Borderline personality features and emotion regulation deficits are associated with child physical abuse potential. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;52:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huremovic D. In: Psychiatry of pandemics: A mental health response to infection outbreak. Huremovic D., editor. Springer Switzerland; Cham: 2019. Mental health of quarantine and isolation. [Google Scholar]

- ICBF . Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar; Gobierno de Colombia: 2020. Medidas de prevención y contención en los servicios de protección del ICBF frente a la infección por COVID-19[Prevention and containment measures in the ICBF protection services against COVID-19 infection]https://www.icbf.gov.co/system/files/procesos/pu1.p_cartilla_icbf_recomendaciones_covid-19_v1.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- ILO . International Labour Organization; 2020. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work - updated estimates and analysis.https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_745963.pdf Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Isphording I.E., Pestel N. 2020. Pandemic meets pollution: Poor air quality increases deaths by COVID-19. IZA discussion paper No. 13418.https://ssrn.com/abstract=3643182 Retrieved from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., Bellis M.A., Wood S., Hughes K., McCoy E., Eckley L.…Officer A. Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet (British Edition) 2012;380(9845):899–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60692-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz C. How can children be protected during COVID-19? Mifgash: Harun National Journal. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K., Lyon T., Taliaferro G., Little L. Why child maltreatment researchers should include children’s disability status in their maltreatment studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(2):147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent H.K., Harold G.T., Leve L., Shelton K.H., Van Goozen S.H. Understanding the unfolding of stress regulation in infants. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28(4pt2):1431–1440. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie D., Holmes L., Hitrova C., Ott E. 2020. Ethics review of machine learning in children’s social care: Executive summary.https://whatworks-csc.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/WWCSC_Ethics_of_Machine_Learning_in_CSC_Executive_Summary_Jan2020.pdf Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Levi H., Katz C. Unseen: How the Israeli government is failing in protecting children during COVID-19. Meidaos: The Israeli National Journal for Social workers. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Levine D.T., Stekel D.J. So why have you added me? Adolescent girls’ technology-mediated attachments and relationships. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;63:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson J.F. Systematic review of COVID‐19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatrica. 2020;109(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyten P., Campbell C., Fonagy P. Borderline personality disorder, complex trauma, and problems with self and identity: A social‐communicative approach. Journal of Personality. 2019;88(1):88–105. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K. Multilevel investigation into the community context of child maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2014;23(3):229–248. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2014.881950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K., Showalter K. The protective effect of neighborhood social cohesion in child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;52:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K., Korbin J.E., Perzynski A., Coulton C., Font S., Spilsbury J.C. In: Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system. Dettlaff A.J., editor. Springer; Dordrecht: 2020. How place matters in child maltreatment disparities: Geographical context as an explanatory factor for racial disproportionality and disparities. (in press 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Marchionni M., Gasparini L., Edo M. Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina; Caracas: 2019. Brechas de género en América Latina. Un estado de situación[Gender gap in Latin America. A state of affairs]https://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/1401 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews B., Pacella R., Dunne M.P., Simunovic M., Marston C. Improving measurement of child abuse and neglect: A systematic review and analysis of national prevalence studies. PloS One. 2020;15(1):e0227884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan W.M., Pratt C.C. The predictive impact of domestic violence on three types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(7):869–883. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M.M. The link between domestic violence and child abuse: Assessment and treatment considerations. Child Welfare. 1994;73(1):29–39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8299407/ Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeigh J.D., McDonell J.R., Lavenda O. Neighborhood poverty and child abuse and neglect: The mediating role of social cohesion. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;93:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McTavish J.R., Sverdlichenko I., MacMillan H.L., Wekerle C. Child sexual abuse, disclosure and PTSD: A systematic and critical review. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;92:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]