A thermodynamically guided approach enables the solvent-based recycling of multilayer plastic packaging films.

Abstract

Many plastic packaging materials manufactured today are composites made of distinct polymer layers (i.e., multilayer films). Billions of pounds of these multilayer films are produced annually, but manufacturing inefficiencies result in large, corresponding postindustrial waste streams. Although relatively clean (as opposed to municipal wastes) and of near-constant composition, no commercially practiced technologies exist to fully deconstruct postindustrial multilayer film wastes into pure, recyclable polymers. Here, we demonstrate a unique strategy we call solvent-targeted recovery and precipitation (STRAP) to deconstruct multilayer films into their constituent resins using a series of solvent washes that are guided by thermodynamic calculations of polymer solubility. We show that the STRAP process is able to separate three representative polymers (polyethylene, ethylene vinyl alcohol, and polyethylene terephthalate) from a commercially available multilayer film with nearly 100% material efficiency, affording recyclable resins that are cost-competitive with the corresponding virgin materials.

INTRODUCTION

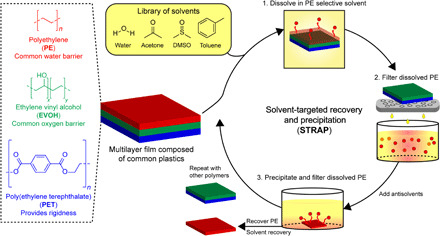

Multilayer plastic films are ubiquitous in the flexible and rigid plastic packaging industry (1). These complex materials, represented schematically in Fig. 1, are constituted by distinct layers of heteropolymers such as polyolefins and polyesters, with each layer selected to contribute a corresponding property advantage to the bulk material, depending on the application (2). The following are examples: Polyethylene (PE) is a flexible material that is often used as a moisture barrier in packaging materials for medical and consumer goods; ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH) is an oxygen barrier commonly found in food packaging materials; polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is an effective gas and moisture barrier that imparts rigidness and strength and is ubiquitous in single-use plastic water bottles (3). Adding to the complexity of these materials, although not shown explicitly in Fig. 1, are any number of tie layers [such as ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA)], wet bond adhesives, or additives (such as TiO2) that may be present in small [<1 weight % (wt %)] quantities compared with the principal resin fractions.

Fig. 1. Overview of the STRAP process.

Schematic representation of a multilayer plastic film consisting of three common polymer resins, and key steps in the solvent-targeted recovery and precipitation (STRAP) process for segregating these component resins into pure, recyclable streams using a series of solvent washes.

The versatility and affordability of multilayer plastic films have created a large demand for them. Accordingly, more than 100 million tons of multilayer thermoplastics are produced globally each year (4). However, up to 40% of manufactured multilayer films go unused in the final packaging application because of inefficiencies in the packaging fabrication processes, such as cutting the film into templated shapes (5). These unused fractions represent large, postindustrial waste (PIW) sources that are not contaminated with food or other impurities and could be readily captured and reintroduced into multilayer film manufacturing equipment. This sort of closed-loop recycling scheme, wherein manufactured waste materials are collected and reused in their originally intended capacity, meets the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s definition of primary recycling (6). However, multilayer packaging materials cannot be recycled using traditional plastic recycling technologies (like mechanical recycling) owing to the chemical incompatibility of the different layers. To be compatible with existing recycling infrastructures, multilayer plastic waste scraps would first need to be partially or fully deconstructed into their constituent resins before being cofed into processing equipment to produce reconstituted multilayer films (7). Currently, no commercially viable technologies exist to do so. Multilayer plastics present in postconsumer municipal waste streams present a similar problem: Technologies exist to recycle single-component plastics based on mechanical or chemically assisted methods (8), but no strategies exist to process multilayer films in closed-loop primary recycling schemes (9, 10). Furthermore, in contrast to PIW wastes, these postconsumer waste streams are contaminated with food and other impurities, making the cleaning of them a challenge. Together, these technology gaps represent key facets of an ongoing human and environmental health crisis that is characterized by outcomes such as the accumulation of plastic waste in oceans, fetid human habitats, and dead marine life (11).

One approach for recovering individual polymer components from mixed plastic wastes is to selectively dissolve the targeted polymer in a solvent system (12, 13). At least two technologies based on this strategy are being commercialized in Europe and Asia: the Newcycling process operated by APK AG, and the CreaSolv Process operated by Unilever and the Fraunhofer Institute. Both technologies are premised on selective dissolution of polyolefins (such as PE and polypropylene) in hydrocarbon solvents (14, 15). These commercially relevant examples demonstrate that solvent-based technologies represent realistic, near-term approaches for recycling complex PIW plastics. Few details regarding these or similar technologies have been reported in the scientific literature, which represents a barrier to deployment on a broader scale. Toward reducing solid waste associated with the manufacture of multilayer films in the near term, it would be helpful to outline a more rigorous approach for how solvents can be used to recycle these materials in a systematic way.

Here, we report a computationally guided platform strategy to deconstruct multilayer films of realistic complexity (three or more layers) into their constituent resins via a series of solvent washes in an approach that we call solvent-targeted recovery and precipitation (STRAP). As shown in Fig. 1, the general principle underlying the STRAP process is to selectively dissolve a single polymer layer in a solvent system in which the targeted polymer layer is soluble, but the other polymer layers are not. The solubilized polymer layer is then separated from the multilayer film by mechanical filtration and precipitated by changing the temperature and/or adding a cosolvent (an antisolvent) that renders the dissolved polymer insoluble. The solvent and antisolvent are distilled and reused in this process, and the targeted polymer layer is recovered as a dry, pure solid. This process is repeated for each of the polymer layers in the multilayer film, resulting in a number of segregated streams that can then be recycled.

We demonstrate the STRAP process by separating three representative polymer resins—PE, EVOH, and PET—from an actual postindustrial multilayer film (manufactured by Amcor Flexibles) that is primarily composed of these three components. We achieved separation of these three components with nearly 100% material efficiency, recovering the individual resins in a chemically pure form, through sequential solubilization of each component in a solvent system identified by molecular modeling of temperature-dependent polymer solubilities. Detailed technoeconomic analyses demonstrate that, in a postindustrial operating environment characterized by minimum volumes of 5400 tons/year and near-constant film compositions, the STRAP process could recycle the Amcor multilayer film into pure, corresponding resins at a cost comparable to the virgin materials. Therefore, the STRAP process represents a realistic and near-term approach to design solvent systems for recycling multilayer plastics.

RESULTS

Computational tools used to select solvents for the STRAP process

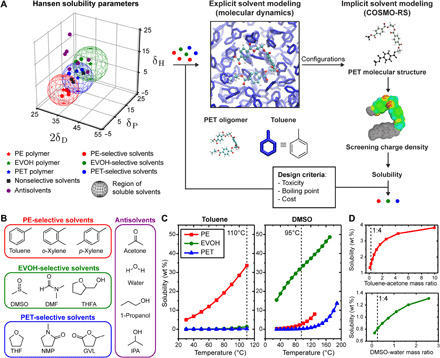

The key to successful implementation of the STRAP process is the ability to preselect solvent systems and temperatures capable of selectively dissolving a single polymer layer from among all of the components present in a multilayer film. Given the complexity of multilayer films, which are often composed of more than 10 layers (16), and the large number of industrial solvents and solvent mixtures available, solvent selection is challenging using experimental screening alone. The aforementioned tie layers and additives present in actual multilayer films further complicate the problem of identifying an appropriate series of solvent-mediated steps to deconstruct the bulk material into a manageable series of segregated streams, as they are present in dilute quantities (<1 wt %) and are often ill-defined. Here, we prescribe a guided approach to rationally select solvents using calculations of Hansen solubility parameters (HSPs), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and a combined quantum chemical and statistical mechanical approach called the conductor-like screening model for realistic solvents (COSMO-RS) as summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Computational tools used to guide the solvent selection for the STRAP process.

(A) Process of selecting solvents using a combination of HSPs, classical MD simulations, and COSMO-RS calculations. The solubility of PE, EVOH, and PET was estimated using HSPs for 22 common solvents (values in Supplementary Materials). Solvents selective to each polymer were then used for subsequent calculations. Classical MD simulations were performed to provide input oligomer configurations for COSMO-RS, which uses ab initio methods to calculate the screening charge density of each molecule. COSMO-RS calculations then determine thermodynamic properties, such as solubilities. (B) PE-, EVOH-, and PET-selective solvents and antisolvents (in which none of the polymers are soluble) determined from HSP calculations. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; THFA, tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol; THF, tetrahydrofuran; NMP, N-methylpyrrolidinone; GVL, γ-valerolactone; IPA, isopropyl alcohol. (C) Predicted solubility versus temperature for PE, EVOH, and PET in pure toluene (PE selective) and DMSO (EVOH selective) computed using COSMO-RS. (D) Predicted solubility versus solvent-antisolvent mass ratio for PE (red curve) and EVOH (green curve). Acetone and water were used as antisolvents for the dissolution of PE and EVOH, respectively. Black dashed lines in (C) and (D) are the temperatures and mass ratios selected for the STRAP process.

The solubility of a polymer can be characterized by three HSPs that quantify the strength of dispersion interactions (δD), dipole-dipole interactions (δP), and hydrogen bonding interactions (δH) between solvent and solute molecules. HSPs for a wide range of pure solvents and polymers have been tabulated on the basis of empirical measurements to obtain self-consistent values (17). HSPs for solvents are estimated as functions of their measured enthalpies of vaporization. HSPs for polymers are determined by experimentally quantifying polymer solubility in reference solvent systems that span HSP space (17) and by identifying a spherical subspace centered on the HSPs of the polymer such that solvents that promote polymer dissolution fall within the sphere. The radius of the polymer’s solubility sphere (R0) therefore depends on the polymer’s solubility in the reference solvent systems. “Good” solvents (those that promote polymer dissolution at the desired concentration) that are not included in the reference set can then be identified by calculating the geometric distance between HSP values for the solvent and solute in δD − δP − δH space (Ra); good solvents are defined as those that fall within the solubility sphere for the corresponding polymer (Fig. 2A) or equivalently when the ratio Ra/R0 is less than one (see Supplementary Materials, section S3). HSP calculations can thus select good solvents (with Ra/R0 less than one) and poor solvents (with Ra/R0 greater than one) using only a small number of experiments. Antisolvents can also be identified as solvents in which none of the polymer layers are readily soluble.

We tabulated HSPs for 22 common industrial solvents from (17) and compared with HSPs for PE, EVOH, and PET to determine solvents suitable for selective dissolution of each resin from among physical mixtures of the three (Fig. 2B). HSPs for a subset of solvents considered are listed in Table 1. On the basis of these calculations and consideration of design criteria relating to cost, co-miscibility of solvents and antisolvents, and toxicity limits, we selected toluene/acetone and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)/water mixtures as solvent/antisolvent systems for selectively dissolving/recovering PE and EVOH resins, respectively. The HSP analysis does not predict PET to be readily soluble in any of these solvents.

Table 1. Solubilities of PE, EVOH, and PET in select solvent systems determined by HSPs (Ra/R0), COSMO-RS calculations, and experiments.

Ra/R0 is the ratio of the polymer-solvent distance to the interaction radius of the polymer (R0) in δD − δP − δH space. Ra/R0 less than unity means that the polymer is likely to dissolve in the solvent, whereas Ra/R0 greater than unity means that the polymer is insoluble in the solvent. ND indicates nondetected solubilities.

| Component resin | Solvent system | Temperature (°C) | Ra/R0 |

COSMO-RS solubility (wt %) |

Experimental solubility (wt %) |

| PE | Toluene | 110 | 0.37 | 33.62 | 14.56* |

| PE | DMSO | 95 | 2.66 | 2.69 | 0.04 |

| PE | 1:4 toluene:acetone | 25 | 1.31 | 1.57 | ND |

| PE | 1:4 DMSO:water | 25 | 5.53 | 0.00 | ND |

| EVOH | Toluene | 110 | 2.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| EVOH | DMSO | 95 | 1.03 | 32.54 | 14.05 |

| EVOH | 1:4 toluene:acetone | 25 | 1.53 | 0.13 | ND |

| EVOH | 1:4 DMSO:water | 25 | 3.53 | 0.82 | ND |

| PET | Toluene | 110 | 1.06 | 1.33 | 0.00 |

| PET | DMSO | 95 | 1.65 | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| PET | 1:4 toluene:acetone | 25 | 0.91 | 0.00 | ND |

| PET | 1:4 DMSO:water | 25 | 4.80 | 0.00 | ND |

*upper limit of PE wt% in toluene tested, as higher concentrations resulted in a viscous solution that was difficult to stir. This value therefore represents a lower limit for PE solubility in toluene at the temperature indicated.

We next performed COSMO-RS calculations to estimate process conditions (temperature and specific mixture compositions) for efficient material recovery. COSMO-RS combines unimolecular density functional theory calculations with statistical thermodynamics methods to account for molecular interactions, thus enabling a priori predictions of polymer solubility in solvent mixtures as a function of both the temperature and the composition of the liquid phase (18, 19). To consider different polymer configurations, we performed classical MD simulations of a single oligomer in solution (see Supplementary Materials, section S3). The lowest energy configurations were then input to COSMO-RS and used to calculate the solubilities of the three polymers in the same 22 solvents for which HSPs were computed. Good solvents (i.e., with high polymer solubility) identified by COSMO-RS largely overlapped with those selected based on HSPs, indicating that both methods produce similar solvent selections. Toluene and DMSO are among the top candidate solvents that selectively dissolve PE and EVOH, respectively, based on both methods. Both methods also indicate that tetrahydrofuran (THF) is a possible candidate for selectively dissolving PET, but the COSMO-RS calculations suggest that solubility would still be low at room temperature (table S10).

We next calculated the solubilities of all three polymers in toluene and DMSO at temperatures ranging from room temperature to the boiling point of each solvent to determine the temperatures necessary to facilitate the desired separations (Fig. 2C). In toluene, the solubility of PE increases more rapidly than PET and EVOH with temperature, and the solubility of PET or EVOH never exceeds a few weight percent in the temperature range considered. Therefore, we chose the boiling point of toluene (110°C) for the separation of PE. In DMSO, although the solubility of EVOH is much higher than the solubilities of PET and PE, the PE solubility begins to increase near 100°C. We thus chose to separate EVOH in DMSO at 95°C. We lastly computed the solubilities of PE in a toluene-acetone mixture and EVOH in a DMSO-water mixture by varying the solvent-to-antisolvent mass ratios (Fig. 2D). Both solubilities decrease as the fraction of antisolvent increases. We chose a mass ratio of 1:4 DMSO:water for precipitation, which is close to the lowest mass ratios we calculated.

Table 1 lists the normalized HSP interaction radii (Ra/R0), COSMO-RS–predicted solubilities, and experimentally determined solubility limits for PE, EVOH, and PET in select solvent systems. As expected, the highest experimentally determined solubilities are obtained for the solvent systems selected from simulations, with discrepancies between the predicted and experimental solubilities due in part to uncertainty in the crystallinity of the polymer samples. Together with Fig. 2, the results in Table 1 form the basis for a process to separate a mixture consisting of PE, EVOH, and PET into pure resins consisting of three steps:

-

1)

Selectively dissolving the PE fraction in toluene at 110°C and then separating the solubilized fraction from the EVOH and PET via mechanical filtration;

-

2)

Selectively dissolving the EVOH fraction in DMSO at 95°C and then separating the solubilized fraction from the remaining PET via mechanical filtration; and

-

3)

Recovering the solubilized PE and EVOH fractions by lowering the corresponding solutions’ temperatures to 25°C and adding four masses of acetone or water, respectively, to precipitate the polymer resins as solids. The recovered PE and EVOH are then separated from the toluene-acetone or DMSO-water mixtures by filtration. The solvents used in this process can then be separated via distillation and reused.

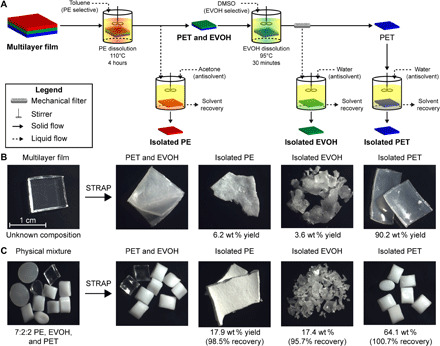

STRAP process used to separate PE, EVOH, and PET

To demonstrate the STRAP process using the protocol outlined above, we first attempted to separate a physical mixture of resin beads consisting of 7:2:2 PET:EVOH:PE by weight. The detailed methods along with the materials and analytical methods used are described in the Supplementary Materials. As shown in Fig. 3, near quantitative yields of the original polymers were recovered (98.5 wt % recovery of PE, 95.7 wt % recovery of EVOH, and 100.7 wt % recovery of PET). The solid fractions isolated from this process were essentially pure in their individual PE, EVOH, or PET components, as expressed by their Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra (fig. S2).

Fig. 3. STRAP process separates PE, EVOH, and PET mixtures.

(A) Process schematic for deconstructing an Amcor Evolution multilayer film into its constituent resins using the STRAP process. (B) Photographs of the Evolution film and the recovered resin using the STRAP process in (A). The mass balance for this process is 100.44 wt % with respect to the initial mass of the evolution film, with an SE of ±1.39 wt %. Photo credit: Theodore W. Walker, University of Wisconsin-Madison. (C) Photographs of comingled plastic resin beads consisting of 7:2:2 PE, EVOH, and PET and the recovered resins using the same procedure in (A). The mass balance for this process is 99.40 wt % with respect to the initial mass of the physical mixture, with an SE of ±0.19 wt %. Photo credit: Theodore W. Walker, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

We next attempted to deconstruct an actual postindustrial, rigid multilayer film manufactured by Amcor Flexibles. This multilayer film consists primarily of PET with PE and EVOH. The film was cut into 1 × 1 cm2 stamps and stirred in a solvent system consisting of toluene at 110°C, and then a solvent consisting of DMSO at 95°C, each with a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:4 by mass. Following vacuum filtration at 95°C, the filtered solutions were combined with an antisolvent at room temperature consisting of four masses of acetone or water with respect to toluene or DMSO, and the resulting mixtures were allowed to cool to room temperature before filtering out the precipitated solids. The resulting three solid fractions were all washed with water and dried in a vacuum oven overnight at 85°C to remove residual solvents. Near quantitative recovery of the pure resins was achieved with a total mass balance of 100.4 wt % with an SE of ±1.39 wt % between three replicate experiments (Fig. 3).

Characterizing the solids from the STRAP process

Figure S2 displays the attenuated total reflectance (ATR)–FTIR spectra corresponding to representative solid materials recovered from the experiments described above. As express by their ATR-FTIR spectra, the PET, EVOH, and PE recovered from the physical mixture are indistinguishable from the same, corresponding virgin resins. These results demonstrate that the STRAP process is able to separate a physical mixture of PET, EVOH, and PE into three solid fractions that are essentially pure in the individual resin components. Likewise, the virgin PET and the PET-rich solids recovered from the Amcor multilayer film are indistinguishable from one another, indicating a complete separation of PET from the multilayer film. Similar results were achieved for the EVOH fraction recovered from the multilayer film.

The toluene-soluble material recovered from the Amcor multilayer film contains primarily PE with an EVA impurity (fig. S2). The presence of this EVA component (a copolymer tie layer) was not known a priori, and its removal is not necessary for the recycling of the PE in Amcor equipment. Nonetheless, a third solvent-mediated separation step was performed to complete the separation of these two components by dissolving the EVA component in N-methylpyrrolidinone (NMP) in which PE is immiscible (see Supplementary Materials). The resulting solids (fig. S3) displayed a marked decrease in the EVA contaminant, as expressed by a reduction in the corresponding spectral feature in the FTIR signature.

Having demonstrated the near-complete separation of three representative polymer components of a multilayer film, we tested the physical properties of the recovered solids to assess their suitability for reuse in standard industrial processing equipment like blown film extruders. The glass transition temperatures (Tg) for the PET and EVOH fractions tested in this study are displayed in table S3. The Tg of PE is difficult to measure, and therefore, these tests were not conducted in this study. The Tg for the EVOH fractions recovered from a physical mixture and the actual multilayer film are unchanged from the virgin resin and are similar to literature values (20–22). The Tg for the PE recovered from the multilayer film is slightly lower than the Tg for PE recovered from the physical mixture. However, the Tg for the PET fraction recovered from the physical mixture is unchanged compared with the virgin resin and similar to reported values (23, 24). These results suggest that the Tg of the PET is slightly modified during the process used to manufacture the multilayer film but not during the STRAP process. We note that, under the conditions studied in the report, we do not expect the average molecular weight of the PE, EVOH, and PET resins to change during the dissolution/recrystallization process. Although not performed in this study, this behavior could be confirmed by gel permeation chromatography coupled with multiangle laser light scattering.

Last, headspace gas chromatography–flame ionization detector test were conducted to test for the presence of entrained solvents in the recovered polymer fractions (see Supplementary Materials) (25). It was found that, for all materials listed in Table 1, there was less than 1000 parts per million (ppm) residual solvent present in the recovered resins. At these levels of solvent retention, the recovered polymers are fit for use in most multilayer films insomuch as the solvents will not compromise the mechanical properties of the final, reconstituted products.

Although a detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this report, additional concerns in this context include how the toxicity, odor, or other properties of retained solvents affect the suitability of the recovered polymers for applications such as food packaging. A number of solutions can be conceived to address these issues on a case-by-case basis. For example, if solvent retention is an issue in a food packaging application, then the recycled resin could be used to produce a multilayer film in which the recycled fraction does not come in contact with the food (i.e., an interior layer of film). Whatever the application, however, the viability of the STRAP process ultimately hinges on the ability to produce fit-for-use recycled resins while efficiently recovering and reusing the solvents so that production of the recycled polymer resins is cost-competitive with the production of the virgin materials.

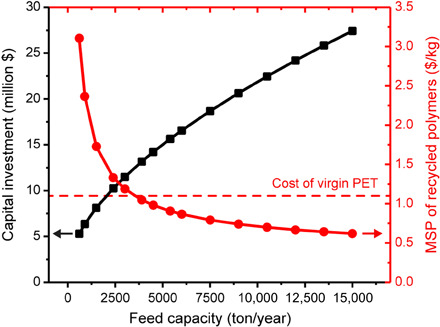

Technoeconomic analysis of the STRAP process

Following the point that recycled polymers must be produced at a cost comparable to the price of the corresponding, virgin resins, we carried out a technoeconomic analysis of the STRAP process based on the experimental data reported here. The detailed methods underlying this analysis, along with relevant assumptions, model parameters, and detailed results, are available in the Supplementary Materials (figs. S5 and S6 and tables S5 and S15 to S18). Figure 4 shows the total capital investment and the minimum selling price (MSP) of recycled polymer components as a function of the feed capacity.

Fig. 4. Total capital investment and MSP for the combined, recycled PE, EVOH, and PET streams derived from an Amcor Evolution multilayer film using the STRAP process, both as a function of feed capacity in tons of Amcor Evolution film per year (circles, MSP; squares, Capital Investment).

Market price of virgin PET is shown as a dotted line for reference.

According to our estimates, the STRAP process could separate the Amcor Evolution film at an MSP of $1.19/kg for the combined, recycled resins when the feed rate is 3000 tons of Amcor Evolution film per year. The MSP decreases to $0.6/kg as the feed rate is increased to 15,000 tons/year. The distillation columns and the heat required to separate the solvents and antisolvents are the major cost drivers for this process, accounting for 33.6% of the total capital investment and 79.3% of the variable operating cost, respectively. When the feed rate is 3800 tons/year, which is less than half of the volumes processed in APK’s Newcycling plant in Germany (14), the MSP of the recovered polymers is competitive with the average market value of virgin PET ($1.1/kg) (26, 27). Note that the Amcor evolution film consists of 90.2 wt % PET.

The energy requirement for separating the multilayer film is 79.13 MJ/kg, which is about 37% less than the energy required to manufacture virgin PET resin (125 MJ/kg). For comparison, the energy generated from combustion of waste plastics (the most realistic, non-landfill disposition for plastic films today) is 6.09 MJ/kg of the multilayer film (28, 29); however, combustion releases 950 kg of CO2 per ton of plastic waste (30). These analyses, together with the aforementioned examples of comparable solvent-based technologies (12–15), show that the STRAP process could be deployed at scale to fully recycle realistic waste streams originating from multilayer plastic film plants.

DISCUSSION

Solvent-based PIW plastic recycling technologies most immediately comparable to the STRAP process are the two aforementioned examples currently being practiced at the commercial scale: APK’s Newcycling process (14) and the Unilever/Fraunhofer Institute CreaSolv process (15). APK’s Newcycling process is based on preferentially dissolving PE or polypropylene from multilayer plastics in a solvent system consisting of alkanes, isooctane, or cycloalkanes (14); dissolved polymers are recovered from solution and pelletized by extrusion (31, 32). APK has built an 8000 ton/year plant in Germany based on this process and suggests that polypropylene, PET, polystyrene, polylactic acid, and aluminum could also be recovered with this process in the future (31). The Fraunhofer Institute has reported a multilayer film recycling process called CreaSolv. This process is based on selective dissolution of polyolefins using a solvent selected from a group of aliphatic hydrocarbons. An antisolvent consisting of mono/polyhydroxy hydrocarbons, e.g., 1-propanol or 1,3-propanediol, is then used to precipitate the polyolefin from the mixture (15). The institute has also studied the separation of polystyrene (33).

PureCycle Technologies, in a prominent example of commercial-scale solvent-based polymer recycling, is building a 54,000 ton/year facility to recover polypropylene from postindustrial and postconsumer waste, in collaboration with Proctor and Gamble (34). PureCycle’s process consists of contacting the plastic waste with a proprietary solvent at elevated temperatures and pressures to obtain the purified polypropylene. In contrast to the STRAP process, PureCycle’s technology processes larger volumes of waste plastic from distributed sources but recovers only a single recycled polymer component. Another example of a solvent-based, industrial-scale plastic recycling technology is the Solvay VinyLoop process. This technology separates polyvinyl chloride (PVC) from polymer coatings and involves both a mechanical step and a selective dissolution step using a proprietary solvent (35); however, this process was no longer operating commercially as of 2018.

Several chemical depolymerization processes have been developed for conversion of polyesters into monomer units including Eastman’s methanolysis process (36), IBM’s Volcat process (37), and Ioniqa’s catalytic PET process (38). These technologies are likely more expensive to operate than the STRAP process, as they involve reconstituting the virgin polymer from their corresponding monomers and require more separation steps. Other basic research efforts in waste plastic recycling are aimed at replacing multilayer film components with polymers that are more easily depolymerized or biodegraded; however, these efforts represent longer-term approaches that are far from commercialization (39, 40).

The multiplicity of these examples demonstrates the timeliness of the problem around recycling of complex, multilayer PIW plastic. The examples of solvent-based technologies currently commercially practiced indicate that selective dissolution represents a promising approach to recycling of complex plastics wastes. However, the aforementioned approaches did not leverage the thermodynamic calculations described here for solvent design and were therefore able to recover at most two polymer components in pure form. In contrast, the methodology described here is demonstrably capable of fully deconstructing multilayer plastic wastes of realistic complexity. While we have not carried out a detailed analysis of the dilute but-non-zero levels of tie layers (e.g., EVA; fig. S3), wet bond adhesives, and other additives present in realistic multilayer films, it is likely that these layers can be recycled with the principle resin fractions, as they are chemically compatible. Highly cross-linked polymers (such as cross-linked polybutadiene), however, may not readily dissolve in any available solvents, making their complete separation from the targeted resins impossible. As discussed above, the impact that these impurities, as well as the entrained solvents (table S1), have on the fitness of the recovered polymer for use depends on the intended application of the final, reconstituted multilayer film, and a detailed analysis of these impurities is necessary to fully derisk the STRAP process in a particular operating environment.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the ability of the STRAP process to efficiently deconstruct a commercial PIW film into nearly 100% yield of three constituent resins. The process uses sequential solubilization steps in solvents selected on the basis of computational modeling of polymer solubility. We propose that the STRAP process could be quickly implemented on the large scale to target postindustrial multilayer plastic waste streams, as they originate from point sources (manufacturing plants), are of known and near-constant composition, and are of substantially high volume (~100 billion pounds per year globally). These attributes would allow large volumes of postindustrial multilayer plastic waste to be processed and recycled using existing equipment combined with STRAP technology. Detailed economic analyses of the STRAP process, assuming an annual feed rate of 3800 tons, indicate that the STRAP process could fully deconstruct a multilayer plastic waste stream consisting of PE, EVOH, and PET into their corresponding resins at costs similar to the corresponding virgin resins.

Future work should focus on deconstructing films composed of resins not studied in this report to include polyamides, polystyrene, and PVC, which we believe is possible using readily available industrial solvents. Our in-depth molecular modeling framework, which leverages a fundamental understanding of the thermodynamics of the polymer-solvent interactions, is broadly applicable and will allow for the rational design of new solvent systems for processing complex multilayer plastics of almost any composition going forward. This rapidly adaptable aspect of the STRAP process represents a key advancement toward addressing the problem of complex plastic wastes accumulating in the environment, as the compositions of multilayer films are constantly being redesigned to meet changing needs, requiring flexible technologies to successfully recycle them. Last, being based on simple unit operations such as stirred tanks, filters, and distillation columns, the STRAP process can be viewed as a platform technology that could be derisked in a well-defined, postindustrial operating environment and, in the future, be adapted to process more complex postconsumer waste streams. Together, these attributes make the STRAP process a promising strategy toward the near-term reduction of postindustrial and postconsumer plastic waste and toward addressing the ongoing environmental crisis associated with the permeation of these wastes into human and animal habitats at every scale.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Model resins were obtained from vendors and used as received: Soarnol EVOH (Mitsubishi Chemical, 32 mole percent ethylene), high-density PE (ExxonMobil Chemical; molecular weight, 7845.30 Da), and Array 9921M PET (DAK Americas). Solvents and antisolvents were obtained from vendors and used as received: acetone (Fisher Scientific, histological grade), water (Alfa Aesar, high-performance liquid chromatography grade), toluene (Sigma-Aldrich, >99.5%), and DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, American Chemical Society reagent grade). The model multilayer film was obtained from Amcor Flexibles (Evolution film, proprietary formulation).

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was conducted using a Bruker Optics Vertex system with a diamond-germanium ATR single reflection crystal. Samples were dried in a vacuum oven overnight to remove water content before analysis and were pressed uniformly against the diamond surface using a spring-loaded anvil. Sample spectra were obtained in triplicates using an average of 128 scans over the range between 400 and 4000 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1. Air was used as background.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Glass transition temperatures of PET and EVOH samples were determined by differential scanning calorimetry on a TA Instruments Q100 calorimeter equipped with a liquid nitrogen–cooled refrigeration unit. Temperature ramps were calibrated with an empty pan reference cell. The heating rate was 5°C min−1, and 20 mg of sample was used in each experiment. The glass transition temperature was determined using the TA Instrument–provided analytical software that locates the maximum in the apparent heat capacity of the sample over the observed temperature range, as per standard methods.

Headspace gas chromatography–flame ionization detector tests

One gram of each of the samples was sealed inside a 20-ml headspace vial. The vials were heated at 130°C for 5 min using a Teledyne Tekmar “Versa” headspace autosampler and delivered to an Agilent 7890 GC with an Rtx-1701 column. The resulting peaks were compared to an external standard containing 1 mg of each of the solvents in 1 ml of a high boiling glycol ether, where 1 mg is equivalent to 1000 ppm in 1 g.

Computational and technoeconomic modeling methods

Technoeconomic modeling was performed in the Aspen Plus suite. HSPs (δD, δP, and δH) and values of R0 described above were taken from (17). COSMO-RS calculations were carried out using COSMOtherm 19 software with the parameterization file named BP_TZVPD_FINE_18 (41, 42). All density functional theory calculations were performed using the TURBOMOLE 7.3 software (43). All classical MD simulations used to generate polymer conformations for the COSMO-RS calculations were performed using GROMACS 2016 (44). Polymer and solvent molecules were parameterized using Antechamber and the Generalized AMBER force fields (45, 46). Details of all molecular modeling methods, force field parameters, technoeconomic analyses, and thermodynamic calculations are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

MSPs of recycled polymers afforded from separation of the PE, EVOH, and PET components in the Amcor Evolution film using the STRAP process were estimated using a process model developed in Aspen Plus (V11.0 Aspen Technology). To this end, the STRAP process was divided into two sections as shown in fig. S1: (i) a PE separation process section and (ii) an EVOH/PET separation process section. Process models for the polymer dissolution units (stirred tanks), polymer precipitation units (settling tanks), and solvent/antisolvent separation units (distillation columns) were developed in the Aspen Plus modeling suite, with corresponding performance metrics based on the experimental data reported here. Process models for feed handling equipment such as shredders, floating tanks, friction washers, dewatering machines, and thermal dryers were adapted from previous work and scaled appropriately (47). Mass balances for the main streams in fig. S1 are summarized in tables S1 and S2. Details relating assumptions, input parameters, and operating bases can also be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under award number DE-SC0018409. We also acknowledge funding from the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Alumni Research Fund. We acknowledge K. Sanchez-Rivera from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, for providing a summary of multilayer plastic film solvent recycling technologies. Author contributions: T.W.W., N.F., J.A.D., and G.W.H. performed and designed the STRAP process. Z.S., A.K.C., and R.C.V.L. performed the calculations and designed the computational aspect of this work. J.B. and S.G. supplied the Amcor Evolution film and provided information about multilayer films. S.G. also aided with characterization of the recovered resins. M.S.K. provided the detailed technoeconomic analysis. All authors interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/47/eaba7599/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.L. K. Massey, Permeability Properties of Plastics and Elastomers: A Guide to Packaging and Barrier Materials (William Andrew, Norwich, NY, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 2.O. G. Piringer, A. L. Baner, Plastic Packaging: Interactions with Food and Pharmaceuticals (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuczenski B., Geyer R., Material flow analysis of polyethylene terephthalate in the US, 1996–2007. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 54, 1161–1169 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lithner D., Larsson Å., Dave G., Environmental and health hazard ranking and assessment of plastic polymers based on chemical composition. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 3309–3324 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.R. Coles, M. J. Kirwan, Food and Beverage Packaging Technology (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Salem S., Lettieri P., Baeyens J., Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): A review. Waste Manag. 29, 2625–2643 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia J. M., Robertson M. L., The future of plastics recycling. Science 358, 870–872 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rorrer N. A., Nicholson S., Carpenter A., Biddy M. J., Grundl N. J., Beckham G. T., Combining reclaimed PET with bio-based monomers enables plastics upcycling. Joule 3, 1006–1027 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horodytska O., Valdés F. J., Fullana A., Plastic flexible films waste management – A state of art review. Waste Manag. 77, 413–425 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.P. Lacy, J. Rutqvist, Waste to Wealth: The Circular Economy Advantage (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rochman C. M., Browne M. A., Halpern B. S., Hentschel B. T., Hoh E., Karapanagioti H. K., Rios-Mendoza L. M., Takada H., Teh S., Thompson R. C., Policy: Classify plastic waste as hazardous. Nature 494, 169–171 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappa G., Boukouvalas C., Giannaris C., Ntaras N., Zografos V., Magoulas K., Lygeros A., Tassios D., The selective dissolution/precipitation technique for polymer recycling: A pilot unit application. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 34, 33–44 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Achilias D. S., Roupakias C., Megalokonomos P., Lappas A. A., Antonakou E. V., Chemical recycling of plastic wastes made from polyethylene (LDPE and HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). J. Hazard. Mater. 149, 536–542 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vollmer I., Jenks M. J. F., Roelands M. C. P., White R. J., Harmelen T., Wild P., Laan G. P., Meirer F., Keurentjes J. T. F., Weckhuysen B. M., Beyond mechanical recycling: Giving new life to plastic waste. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15402–15423 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeurer, Andreas, Martin Schlummer, Otto Beck. Method for recycling plastic materials and use thereof, U.S. Patent No. 8,138,232. 20 Mar. 2012.

- 16.B. A. Morris, The Science and Technology of Flexible Packaging: Multilayer Films From Resin and Process to End Use (William Andrew, Cambridge, MA, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 17.S. Abbott, C. M. Hansen, Hansen Solubility Parameters in Practice (2008); Hansen-Solubility.com.

- 18.Klamt A., Conductor-like screening model for real solvents: A new approach to the quantitative calculation of solvation phenomena. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 2224–2235 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klamt A., Jonas V., Bürger T., Lohrenz J. C. W., Refinement and parametrization of COSMO-RS. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 5074–5085 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z., Britt I. J., Tung M. A., Water absorption in EVOH films and its influence on glass transition temperature. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Phys. 37, 691–699 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samus M. A., Rossi G., Methanol absorption in ethylene−vinyl alcohol copolymers: Relation between solvent diffusion and changes in glass transition temperature in glassy polymeric materials. Macromolecules 29, 2275–2288 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang W., Qiao X., Sun K., Mechanical and thermal properties of thermoplastic acetylated starch/poly (ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) blends. Carbohydr. Polym. 65, 139–143 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson A. B., Woods D. W., The transitions of polyethylene terephthalate. Trans. Faraday Soc. 52, 1383–1397 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobbs W. Jr., Burton R., Crystallization of polyethylene terephthalate. J. Polym. Sci. 10, 275–290 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dutra C., Pezo D., de Alvarenga Freire M. T., Nerín C., Reyes F. G. R., Determination of volatile organic compounds in recycled polyethylene terephthalate and high-density polyethylene by headspace solid phase microextraction gas chromatography mass spectrometry to evaluate the efficiency of recycling processes. J. Chromatogr. A 1218, 1319–1330 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishna S. H., Huang K., Barnett K. J., He J., Maravelias C. T., Dumesic J. A., Huber G. W., de bruyn M., Weckhuysen B. M., Oxygenated commodity chemicals from chemo-catalytic conversion of biomass derived heterocycles. AlChE J. 64, 1910–1922 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.D. Zhang, E. A. del Rio-Chanona, N. Shah, in Computer Aided Chemical Engineering (Elsevier, 2018), vol. 44, pp. 1693–1698. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gradus R. H. J. M., Nillesen P. H. L., Dijkgraaf E., Van Koppen R. J., A cost-effectiveness analysis for incineration or recycling of Dutch household plastic waste. Ecol. Econ. 135, 22–28 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.G. Bergsma, M. Bijleveld, M. Otten, B. Krutwagen, LCA: Recycling Van Kunststof Verpakkingsafval Uit Huishoudens (CE Delft, Delft, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khoo H. H., LCA of plastic waste recovery into recycled materials, energy and fuels in Singapore. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 145, 67–77 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.M. Niaounakis, Recycling of Flexible Plastic Packaging (Plastics Design Library, William Andrew, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.K. Wohnig, in GPCA PlastiCon (2018).

- 33.A. Maeurer, M. Schlummer, O. Beck (Google Patents, 2012).

- 34.J. M. Layman, M. Gunnerson, H. Schonemann, K. Williams (Google Patents, 2017).

- 35.B. Vandenhende, J.-P. Dumont (Google Patents, 2006).

- 36.Muhs P., Plage A., Schumann H., Recycling PET bottles by depolymerization. Kunstst. Ger. Plast. 82, 289–292 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukushima K., Lecuyer J. M., Wei D. S., Horn H. W., Jones G. O., Al-Megren H. A., Alabdulrahman A. M., Alsewailem F. D., McNeil M. A., Rice J. E., Hedrick J. L., Advanced chemical recycling of poly (ethylene terephthalate) through organocatalytic aminolysis. Polym. Chem. 4, 1610–1616 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 38.M. V. Artigas et al. (Google Patents, 2019).

- 39.Fan B., Trant J. F., Wong A. D., Gillies E. R., Polyglyoxylates: A versatile class of triggerable self-immolative polymers from readily accessible monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10116–10123 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen E. K. Y., McBride R. A., Gillies E. R., Self-immolative polymers containing rapidly cyclizing spacers: Toward rapid depolymerization rates. Macromolecules 45, 7364–7374 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klamt A., Eckert F., Hornig M., Beck M. E., Bürger T., Prediction of aqueous solubility of drugs and pesticides with COSMO-RS. J. Comput. Chem. 23, 275–281 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen Z., Van Lehn R. C., Solvent selection for the separation of lignin-derived monomers using the conductor-like screening model for real solvents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 7755–7764 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.V. TURBOMOLE, a development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007, TURBOMOLE GmbH, since 2007. There is no corresponding record for this reference.[Google Scholar], (2010).

- 44.Abraham M. J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J. C., Hess B., Lindahl E., GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J. M., Wang W., Kollman P. A., Case D. A., Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 25, 247–260 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J. M., Wolf R. M., Caldwell J. W., Kollman P. A., Case D. A., Development and testing of a general AMBER force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.P. Naviroj, J. Treacy, C. Urffer, Chemical Recycling of Plastics by Dissolution (University of Pennsylvania, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loschen C., Klamt A., Prediction of solubilities and partition coefficients in polymers using COSMO-RS. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 11478–11487 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qi X., Watanabe M., Aida T. M., Smith R. L. Jr., Selective conversion of D-fructose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural by ion-exchange resin in acetone/dimethyl sulfoxide solvent mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47, 9234–9239 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 50.TURBOMOLE, Version 7.3, a development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007, TURBOMOLE GmbH, since 2007. (2010).

- 51.Eckert F., Klamt A., Fast solvent screening via quantum chemistry: COSMO-RS approach. AIChe J. 48, 369–385 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 52.B. Wunderlich, Thermal Analysis (Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warangkhana P., Sadhan C. J., Rathanawan M., Preparation and characterization of reactive blends of poly(lactic acid), poly(ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol), and poly(ethylene-co-glycidyl methacrylate). AIP Conf. Proc. 1664, 030007 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Habgood D. C. C., Hoadley A. F. A., Zhang L., Techno-economic analysis of gasification routes for ammonia production from Victorian brown coal. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 102, 57–68 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weeden G. S. Jr., Soepriatna N. H., Wang N.-H. L., Method for efficient recovery of high-purity polycarbonates from electronic waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2425–2433 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ioelovich M., Optimal method for production of amorphous cellulose with increased enzymatic digestibility. Org. Polym. Mater. Res. 1, 22–26 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 57.A. Dutta, A. Sahir, E. Tan, D. Humbird, L. J. Snowden-Swan, P. Meyer, J. Ross, D. Sexton, R. Yap, J. Lukas, Process design and economics for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to hydrocarbon fuels: Thermochemical research pathways with in situ and ex situ upgrading of fast pyrolysis vapors, (Pacific Northwest National Lab.(PNNL), Richland, WA (United States), 2015).

- 58.G. Towler, R. Sinnott, Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design (Elsevier, 2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/47/eaba7599/DC1