Abstract

Objective

The motion-activated system (MAS) employs vibration to prevent intraluminal chest tube clogging. We evaluated the intraluminal clot formation inside chest tubes using high-speed camera imaging and post-explant histology analysis of thrombus.

Methods

The chest tube clogging was tested (MAS vs. control) in acute hemothorax porcine models (n=5). The whole tubes with blood clots were fixed with formalin-acetic acid solution and cut into cross-sections, proceeded for H&E stained paraffin-embedded tissue sections (MAS sections, n=11; control sections, n= 11), and analyzed. As a separate effort, high-speed camera (FASTCAM Mini AX200, 100-mm Zeiss lens) was used to visualize the whole blood clogging pattern inside the chest tube cross-section view.

Results

Histology revealed a thin string-like fibrin deposition, which showed spiral eddy or aggregate within the blood clots in most sections of Group MAS, but not in those of the control group. Histology findings were compatible with high-speed camera views. The high-speed camera images showed a device-specific intraluminal blood “swirling” pattern.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that a continuous spiral flow in blood within the chest tube (MAS vs. static control) contributes to the formation of a spiral string-like fibrin network during consumption of coagulation factors. As a result, the spiral flow may prevent formation of thick band-like fibrin deposits sticking to the inner tube surface and causing tube clogging, and thus may positively affect chest tube patency and drainage.

Keywords: fibrin deposition, chest tube, bleeding, coagulation, hemothorax, motion-activated system, high-speed imaging

Introduction

In patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery, chest tube placement is a standard practice and the management of chest tubes is essential for the thoracic surgeon(1). The functionality of chest-tube drainage must be properly maintained postoperatively, as the quality and conditions of postoperative hemostasis often suggest the status of bleeding through the volume and character of drainage output. (1–4) Occlusion of chest drainage tubes by thrombus is not uncommon after open heart operations, and has been previously linked to incidence of pericardial effusions, fewer postoperative supraventricular arrhythmias, a shorter hospital stay and significant reduction in postoperative morbidity.

Normal process of blood coagulation in the healthy conditions is achieved through the interaction of blood platelets, the coagulation system and the vascular endothelial cells. The dysregulation of hemostasis may cause serious thrombotic and/or hemorrhagic pathologies. (5) The regulated performance of the coagulation system prevents thrombosis and promotes blood clotting triggered by tissue damage to stop bleeding. This process has been evolved as protective, as it prevents excessive blood loss following injury. (6) Thrombin generation is closely regulated to locally achieve rapid hemostasis after injury without causing uncontrolled systemic thrombosis. (7) The ultimate outcome is the polymerization of fibrin and the activation of platelets, leading to a blood clot.

Unfortunately, the blood clotting system can also lead to unwanted blood clots inside blood vessels, which could further expand to clotting during cardiovascular surgical procedures. During these procedures, there are major disturbances in coagulation and inflammatory systems because of hemorrhage/hemodilution, blood transfusion, and surgical stresses. Postoperative alteration of the coagulation cascade may cause dysregulation of bleeding control mechanisms and drastically affect catheters and devices routinely used for postoperative patient management and monitoring.

Since chest tubes have been routinely used to drain the pleural space, particularly after lung surgery, the management of chest tubes is essential for the thoracic surgeon (1). Drainage of surgical sites, traumatic lesions, and disease-related fluid exudate is usually employed as an important part of postoperative care.

Patency of drainage tubes is essential to treating patients effectively and monitoring abnormal conditions. Chest tube protocols are still largely dictated by personal preferences and experience. A general lack of published evidence encourages individual decision-making and hinders the development of clear-cut guidelines (4). There is still no standardization of chest tube placement, the number of tubes that should be placed, or removal criteria (8). Furthermore, the relative pros and cons of using suction versus no suction have been established as an evidence-based approach (9). Occlusion of the drainage catheters remains an important clinical problem and leads to life-threatening complications such as tamponade and tension pneumothorax.

The most important cause of drainage tube occlusion is intraluminal blood clot formation that alters catheter patency and function. In fact, chest tube occlusion is not uncommonly encountered after open heart operations.(10, 11) Caregivers should use an indwelling tube with a large diameter and introduce manual procedures such as milking, squeezing and tapping, which is not considered sufficient to prevent the tube from clogging and often remain ineffective.(12) In addition to that, the chest tube management can be time-consuming, decreasing the time nurses have for other important tasks. Moreover, caregivers may end up spending less time on proper drainage vs. other priorities in critical care units after surgery.(13) Which de-reprioritizes other tasks of the medical personnel in early postoperative phase.

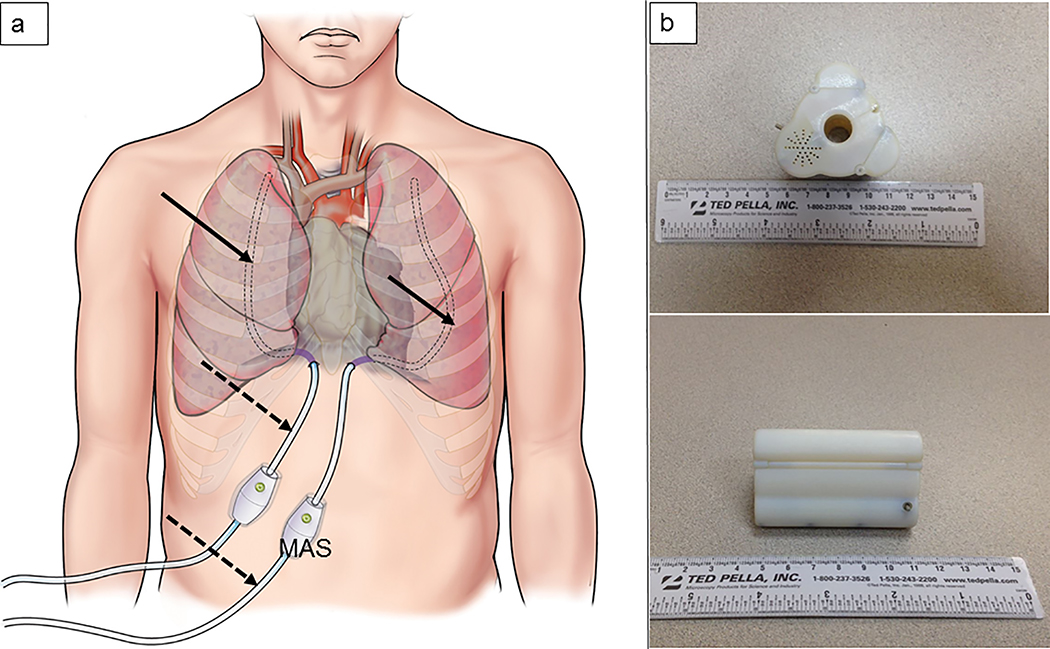

We have recently developed an innovative device, a motion-activated system (MAS), to prevent tube clogging.(14) The MAS was designed to employ vibration to prevent intraluminal chest tube clogging (Figure 1a). Our earlier report showed that the MAS device effectively maintained tube patency by preventing the formation of blood clots that would obstruct inner tube lumens as compared with control tubes, both in vitro and in vivo.(14) As a result, the drainage efficiency of chest tubes with the MAS device was better than that of control tubes in an acute hemothorax porcine model. The mechanisms underlying vibration-mediated prevention of tube clogging remain to be explained. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the mechanisms of the anti-clogging effect of the MAS.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of MAS placement (a) and device prototype (b)

Methods

Device description

The MAS device was developed using SOLIDWORKS® solid modeling software (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) and an Objet350 Connex 3-D printer (Stratasys, Minneapolis, MN) for prototyping. The MAS with external and internal power supply were used during in vitro and in vivo testings. The battery-powered, sterilizable, device units with self-locking housing were fabricated specifically for the clinical evaluation (Figure 1b). The advanced prototype design consisted of a modified high-precision DC motor (Maxon Motor; Sachseln, Switzerland) with an eccentric mass affixed to the motor shaft (spinning axis parallel with chest tube centerline) and on-board battery supply. The nominal external dimensions of advanced MAS device prototypes were 67 mm (length) and 44 mm (diameter).

Histological evaluation for blood clots in an acute hemothorax porcine model (in vivo)

The in vivo study protocol was approved by Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and all animals received humane care in compliance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and institutional guidelines. In five healthy pigs (Yorkshire mix, 48.0 ± 2 kg [M. Fanning Farms, Howe, IN]), an acute hemothorax model was introduced as previously established to evaluate chest-tube drainage.(14) Two regular 32 Fr polyvinyl chloride chest tubes (control and MAS) were bilaterally inserted (6th-7th intercostal space) (Figure 2). The time-controlled blood injections into the chest (each side) were performed (120 ml, every 15 minutes, up to 840 ml of total volume). The standard protocol has been applied for chest tube and canister setup. The flow was not regulated or controlled throughout the blood drainage duration. Chest tubes (both control and device tube) were connected to drainage canisters set at −20 cm H2O suction. The clamps on the chest tubes were released to allow drainage. At the end of two hours, the animals were euthanized. The inserted drainage tubes were collected and cut at the same distance points from the tip. The whole tubes with blood clots were fixed with Formalin-Acetic Acid solution to prevent shrinkage of the blood clots, cut into cross-sections, processed for paraffin-embedded tissue sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (MAS sections, n=11; control sections, n= 11), and analyzed.

Figure 2.

Surgical setup of acute hemothorax model in porcine model

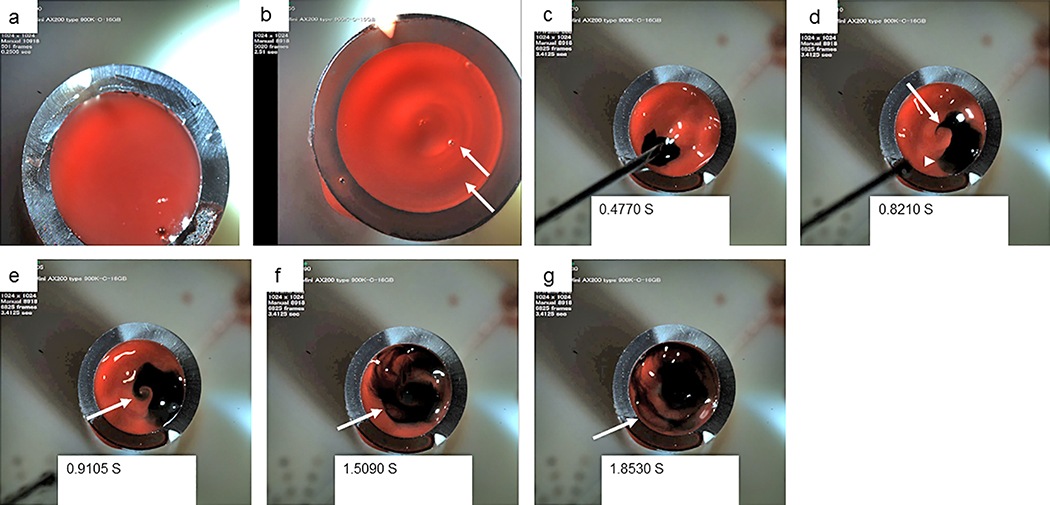

Evaluation by high-speed camera for blood flow in tubes with MAS

The MAS in vitro test was performed using a blood-filled chest-tube model (32 Fr polyvinyl chloride chest tubes; Covidien®, Mansfield, MA). The MAS-coupled tubes were subjected to motion-activation (Figure 3); the Control tube was held still. The chest tubes were clamped at one end and filled with whole porcine blood preserved with the anticoagulant mix of citrate-phosphate-dextrose-adenine. Test tubes with MAS were suspended vertically and filled with blood. A high-speed camera (FASTCAM Mini AX200, 100-mm Karl Zeiss lens) was used to visualize flow patterns of whole blood inside the chest tubes cross-section view. To visualize blood flow in tubes with MAS, blue dye was dropped on the surface of the blood. The intraluminal blood imaging of the tested 32 Fr chest tube cross-sectional area was performed at 1000–2000 fps rate during MAS device activation.

Figure 3.

Bench setup of high-speed camera positioned at the top of the 32-Fr chest tube cross-section (a), and device prototype with whole blood sample during MAS activation and macro image capturing (b)

Results

Macroscopic findings for blood clots

As consistent with the previous report,(14) macroscopic findings of the cutting surface of the chest tubes in the current study series revealed friable soft blood clots within the tubes of the MAS group, which moved easily along the inner lumen of the tubes, while the control tubes were clogged by solid blood clots, which stuck firmly to the tubes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Macroscopic findings for blood clot formation. The photographs shows longitudinal (a) and cross-view (b) of the chest tubes. In the control group, the blood clots expand within the tubes and stick to the inner surface of tube walls, while in MAS, the blood clots are small in size and do not stick to the surface of the tube walls.

Histological findings for blood clots

In the control group, we found homogenous blood clots with lumps of red blood cells entrapped by the fibrin network and fibrin/plasma protein clots, which were surrounded by broad fibrin/plasma protein bands attaching to the inner surface of tube walls (Figure 5a and 5c). The compact mass of red blood cells had a cobblestone appearance (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Histopathological findings for blood clots. The photographs show microscopic findings for blood clots in the control group (a, c) and the MAS Group (b, d, e). Arrows and arrowheads indicate as follows: white arrow, fibrin deposition with or without plasma protein; black arrowhead, inner lumen of tubes; green dotted arrow, band-like fibrin deposition with plasma protein; yellow arrow, small, spiral, eddy-like fibrin depositions or fine fibrin depositions; white arrowhead, cobblestone appearance of lumps of red blood cells entrapped by fibrin network. The magnifications are indicated in the photographs.

In contrast, in the blood clots of the MAS group, there were many small, spiral, eddy-like and thin string-like fibrin deposits, which irregularly comparted the lumps of red blood cells (Figures 5b, 5d, and 5e). Fibrin bands on the inner surface of the tube walls in the MAS group were also observed, but were thinner than those of the control group (Figure 5d). Interestingly, there were many spaces without red blood cells in the clots in the MAS group (Figure 5b), while such spaces were almost filled with fibrin/plasma protein clot in the control groups (Figure 5a and 5c). The free spaces in the blood clots in the MAS group may be contributing to the macroscopic characteristics of thrombi, “friable and soft” blood clots. Table 1 shows a summary of the existence ratio of characteristic histological findings with fibrin/plasma protein depositions in the control MAS groups. Thin string-like fibrin deposits were observed in the MAS group only, and thick band-like fibrin/plasma protein deposits on the inner surface of tube walls was observed in the control group only (Table 1). These histological findings led us to hypothesize that blood clots might form under swirling flow induced by vibration, resulting in heterogeneous fibrin depositions and characteristic clot formation.

Table 1.

Incidence ratios of characteristic fibrin deposition

| Group | Histological findings | Experimental Number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-003 | A-004 | A-005 | ||

| MAS | Fibrin deposits lining the inner surface of tube | 2/2* | 3/4 | 5/5 |

| Thick fibrin/plasma protein band surrounding blood clot | 0/2 | 0/4 | 0/5 | |

| Thin string-like fibrin deposition | 2/2 | 3/4 | 4/5 | |

| Control | Fibrin deposits lining the inner surface of tube | 2/2 | 3/4 | 3/5 |

| Thick fibrin/plasma protein band surrounding blood clot | 0/2 | 1/4 | 2/5 | |

| Thin string-like fibrin deposition | 0/2 | 0/4 | 0/5 | |

MAS - Motion Activated System.

The incidence ratios are indicated: the numbers of specimens with the histological finding/total numbers of the section.

Blood flow in tubes with MAS (In vitro)

The histological assessment of blood clot samples prompted us to directly observe flow patterns in blood within the chest tubes with the MAS device using high-speed camera visualization and optical magnification. Whereas the surface of blood was flat in the control group (Figure 6a), a round wave was triggered on the surface of blood in the MAS Group (Figure 6b). The high-speed camera images revealed that the dye quickly moved in a counterclockwise direction, making a bird beak-like or a sea snail whorl-like figure with swirling movement (Figure 6c, 6d, and 6e) and then, heterogeneously dispersed in the blood with formation of thin line structures entrapping red blood without portions of dye while swirling (Figure 6f and 6g). During the movement, dye tended to converge at the center from the periphery rather than dispersing irregularly. It is noteworthy that the thin line dye patterns resembled the thin line fibrin depositions in the histological findings. These findings suggest that blood clots form under swirling blood flow with a centering vector, resulting in heterogeneous fibrin depositions apart from the inner surface of tube walls with the MAS.

Figure 6.

Blood flow in tubes with MAS. Photographs by high-speed camera for blood fluid in a control tube (a) and in a test tube with MAS (b-g). Arrows indicate round waves on the blood surface in a tube with MAS (b). The photographs were taken at the indicated time points after starting to record (c-g). An arrowhead indicates a dot of dye (d), which quickly moved counterclockwise from the position in c. An arrow indicates a beak-like figure (d). An arrow indicates a “sea snail”, whorl-like figure (e). Arrows indicate thin line dye pattern entrapping unstained blood fluid in different time phases (f, g).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of an intraluminal anti-blood clogging mechanism observed under the effects of catheter motion-activation. High-speed camera analysis and histological findings indicated that a continuous spiral flow in blood within the chest tubes (MAS vs. static control) contribute to the formation of small, spiral, eddy-like and thin string-like fibrin deposits during consumption of coagulation factors. As a result, the spiral flow may have preventive effects on thrombus formation out of homogenous blood clots, with a stiff fibrin network and a peripheral thick fibrin/plasma protein band sticking to the inner surface of tube walls, and positively affecting the chest tube patency and the drainage efficiency.

In histological sections, we found unique friable soft blood clots consisting of heterogeneous fibrin deposition and many spaces in the MAS group, whereas the clogging homogenous blood clots in the control group consisted of a homogenous fibrin network trapping red blood cells and peripheral thick band-like fibrin/plasma protein deposition sticking to the inner surface of tube walls. High-speed camera analysis revealed that MAS-derived vibration triggered the blood-swirling flow with a converging vector to a center. These findings suggest that a continuous spiral flow triggered by the MAS device in blood prevents formation of homogenous substantial blood clots and affects chest tube patency and drainage.

Postoperatively, the controversy often occurs due to the effects of the targeted anticoagulation to reduce complications associated with surgery types (i.e., valves, MCS, etc.), and with the intention to reduce bleeding through better hemostasis and medical management to reduce blood loss. Since the drainage occurs and is only possible through the pre-placed chest tubes, the MAS device platform aims to address the problem that occurs within the indwelling catheter and in adjacent areas to enable patency of blood retreating into and down the drain.

The thrombus formation within the tubes can be affected by multiple factors. The blood flow is an important parameter, but may not always work in favor of better drainage as not only overall volume of drainage, but drainage pattern plays an important role in maintenance of chest tube patency and overall production of drainage. Efficacy of drainage depends on conditions of the internal lumen level of obstruction, but also the areas surrounding the chest tube. It is important to note that there are two regions that might affect clotting: the external area around the chest tube and the internal (the lumen) surface of the chest tube.

Blood clots form at injured vasculatures to prevent blood loss. However, this important physiological phenomenon also causes tube clogging in drainage tubes. Blood clots mainly consist of a fibrin network entrapping red blood cells, and the characteristics of clots determines the mechanical properties.(15, 16) The fibrin network forms through a multistep process: 1) thrombin catalyzes fibrinogen to fibrin monomers, 2) the monomers aggregate to form two strand structures, protofibrils, 3) the protofibrils polymerize into fibrin fibers, 4) the fibrin fibers are cross-linked within and between protofibrils to form a stiff fibrin network (17–21). The viscoelastic property of blood clots affects not only mechanical stability, but also the sensitivity of fibrinolysis. (22, 23) Various factors such as fibrinogen/thrombin concentration, inflammatory responses, and physical stress during fibrin network formation could affect the mechanical property of clots.(18, 23–26) Therefore, it is possible that physical motion may also have an impact on blood clot formation in artificial tubes.

The quality of thrombin-mediated fibrin network formation is important to determine the mechanical properties of blood clots, which is affected by various factors.(18, 23–26) This study clearly showed that the artificial motion affects the fibrin deposition/network pattern during blood clotting. The fibrin depositions were more prominent in the MAS group than those in the control group, which suggests that activation of the coagulation cascade may be facilitated to a greater degree by MAS motion than by the control group. Even though the blood was put under hypercoagulable states, because the MAS device triggered the spiral flow with a central vector to prevent formation of peripheral fibrin deposition close to the inner surface of tube walls, the blood clots may not stick to the inner surface tube walls. In fact, tubes installed with the MAS device did not have broad band-like fibrin/plasma deposits sticking to tube walls, which were often observed in the control group (Table 1). Unlikely in blood circulation, because the amount of coagulation factors must be limited in blood in the chest tubes, the hypercoagulable states may facilitate the consumption of coagulation factors at the center of the tube lumen and contribute to prevention of stiff fibrin network formation at the peripheral blood clots.

There were many spacing lesions in blood clots of the MAS group, but not in those of the control group. The figures of blood clots with spacing resemble those of unretracted blood clots formed in a flint glass, but not in stiff retracted blood clots formed in hydrophilic borosilicate-glass, which have homogenous fibrin network formation in histological sections.(24) The unretracted blood clots are softer than the retracted clots. Therefore, the spacing within the blood clots may contribute to the softness of the blood clots. The qualitative difference between the unretracted and retracted blood clots is similar to the difference in blood clots between the MAS group and the control group, respectively. Both the retracted blood clots and our control blood clots appeared homogenous and displayed very densely packed red blood cells, allowing only scant amounts of fibrin to be visible. Although we could not perform qualitative and quantitative analysis of electron microscopy imaging, the blood clots in the control group are expected to have dense fibrin networks. These findings suggest that homogenous fibrin network formation may be attributed to stiff blood clots clogging tubes, and that the MAS is an appropriate device to prevent such detrimental complications in tube drainages.

When it comes to potential side effects of the vibration related to technology use, we started early to evaluate the range of vibration effects that could be considered substantial and exceeding our requirements for clotting prevention. Those parameters and ranges of motion transmission that were non-effective enough to provide a required effects through vibration were explored. We are currently looking into a clinical study using the device in patients to evaluate tolerance to the device in surgical patients after attachment and prior to activation, and after device activation.

The purpose of this early work was primarily to establish a methodology to evaluate blood clots more specifically to the application that our group is developing. From the array of existing instrumental imaging technologies and modalities that were considered, these histology techniques were selected because we were interested in a microstructural analysis of the clot at the time of formation. However, we were also interested in dynamic evaluation, specifically during the clot formation process. We hypothesized that two techniques that were completely irrelevant to each other would help us to build a better understanding of the preventive mechanisms behind this technology.

Research and development has been performed to render the device parameters, such as motor performance and overall motion transmission. The battery-operated device has been designed to target the focus range to achieve its maximum efficacy while maintaining its miniature size and operational capabilities.

There is no technology directly comparable to our device, as few existing technologies for chest tube drainage are based on different principles and/or address the problem of chest tube clogging by addressing different aspects of the matter. The present technology uniquely affects clot formation within chest tubes, and also affects clot formation at the areas external and adjacent to chest tubes within the patient’s chest cavity.

Over the years, there have been many attempts to organize the imaging and histological analysis in such a way as to actually capture the changes occurring during vibration. Especially during high-speed visualization, it has been extremely cumbersome to organize perfect timing between whole-blood sampling from a live animal and setting up the testing platform as quickly as possible in order to avoid triggering a natural coagulation cascade.

In the early research and development phase, we tested effects using different manufacturers’ tubes and also different size and selected durometers. In order to standardize the testing in this study series, it was decided to use the same size and same manufacturers’ tubing. Different materials may demonstrate different properties related to vibration transmission. The device design is capable of addressing the variability of different materials through its proprietary design points and functional range.

Because this was our first experience with these techniques, we did not aim to analyze the data quantitatively. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time blood clots were analyzed during constant motion, and also visualized at high speed to observe dynamic patterns during vibration. The coagulation process has a complex underlying mechanism, and being able to conduct the feasibility test by using these techniques for the first time fulfilled our intended objective completely. The testing with the blood flow was focused on studying the circular movement and evaluating the vibration patterns of vertically placed chest tubes with variable vibration force. For the cross-sectional analysis using a high-speed camera, a study that would allow blood flow and an adequate field of visualization was of primary interest, since the chest tube end has been defined as a working field.

On other hand, it is important to note that we are indeed considering using a quantitative approach for upcoming studies that will involve larger sample sizes. More importantly, we hope to develop a data collection protocol in order to standardize data sampling.

Conclusions

Our findings provide characterization of intraluminal blood clots formed within chest tube catheters, which can occlude chest tubes, and MAS-triggered vibration prevents formation of such blood clots with homogenous fibrin deposition. The design features of the MAS affect intraluminal blood clotting by preventing the initial clot formation and buildup that contribute to chest tube patency maintenance. High-speed evaluation could be a useful tool for fluid dynamic evaluation in cardiovascular catheters where fluid pattern is of interest. More investigations will be necessary to elucidate anti-clotting mechanisms in a range of chest tube types and sizes.

Sources of Funding

This project has been funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), NIH Center for Accelerated Innovation at Cleveland Clinic (NCAI), (NIH-NHLBI 1UH54HL119810–01; NCAI-14–2-APP-CCF).

Funding: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), NIH Center for Accelerated Innovation at Cleveland Clinic (NCAI), (NIH-NHLBI 1UH54HL119810–01; NCAI-14–2-APP-CCF)

References

- 1.Satoh Y Management of chest drainage tubes after lung surgery. General thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016;64(6):305–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallen M, Morrison A, Gillies D, O’Riordan E, Bridge C, Stoddart F. Mediastinal chest drain clearance for cardiac surgery. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004(4):Cd003042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charnock Y, Evans D. Nursing management of chest drains: a systematic review. Australian critical care : official journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses. 2001;14(4):156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zardo P, Busk H, Kutschka I. Chest tube management: state of the art. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2015;28(1):45–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simak J, De Paoli S. The effects of nanomaterials on blood coagulation in hemostasis and thrombosis. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews Nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology. 2017;9(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SA, Travers RJ, Morrissey JH. How it all starts: Initiation of the clotting cascade. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2015;50(4):326–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka KA, Key NS, Levy JH. Blood coagulation: hemostasis and thrombin regulation. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009;108(5):1433–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smulders YM, Wiepking ME, Moulijn AC, Koolen JJ, van Wezel HB, Visser CA. How soon should drainage tubes be removed after cardiac operations? The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1989;48(4):540–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pompili C, Salati M, Brunelli A. Chest Tube Management after Surgery for Pneumothorax . Thoracic surgery clinics. 2017;27(1):25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter S, Angelini GD. Phosphatidylcholine-coated chest tubes improve drainage after open heart operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56(6):1339–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karimov JH, Gillinov AM, Schenck L, Cook M, Kosty Sweeney D, Boyle EM, et al. Incidence of chest tube clogging after cardiac surgery: a single-centre prospective observational study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44(6):1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shalli S, Saeed D, Fukamachi K, Gillinov AM, Cohn WE, Perrault LP, et al. Chest tube selection in cardiac and thoracic surgery: a survey of chest tube-related complications and their management. J Card Surg. 2009;24(5):503–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook M, Idzior L, Bena JF, Albert NM. Nurse and patient factors that influence nursing time in chest tube management early after open heart surgery: A descriptive, correlational study. Intensive & critical care nursing. 2017;42:116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karimov JH, Dessoffy R, Kobayashi M, Dudzinski DT, Klatte RS, Kattar J, et al. Motion-activated prevention of clogging and maintenance of patency of indwelling chest tubes. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisel JW. Biophysics. Enigmas of blood clot elasticity. Science. 2008;320(5875):456–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Kempen TH, Peters GW, van de Vosse FN. A constitutive model for the time-dependent, nonlinear stress response of fibrin networks. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14(5):995–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan EA, Mockros LF, Weisel JW, Lorand L. Structural origins of fibrin clot rheology. Biophys J. 1999;77(5):2813–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collet JP, Shuman H, Ledger RE, Lee S, Weisel JW. The elasticity of an individual fibrin fiber in a clot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(26):9133–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Jawerth LM, Sparks EA, Falvo MR, Hantgan RR, Superfine R, et al. Fibrin fibers have extraordinary extensibility and elasticity. Science. 2006;313(5787):634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cilia La Corte AL, Philippou H, Ariens RA. Role of fibrin structure in thrombosis and vascular disease. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2011;83:75–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurniawan NA, Grimbergen J, Koopman J, Koenderink GH. Factor XIII stiffens fibrin clots by causing fiber compaction. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(10):1687–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C, Favaloro EJ. Novel and emerging therapies: thrombus-targeted fibrinolysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39(1):48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machlus KR, Cardenas JC, Church FC, Wolberg AS. Causal relationship between hyperfibrinogenemia, thrombosis, and resistance to thrombolysis in mice. Blood. 2011;117(18):4953–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutton JT, Ivancevich NM, Perrin SR Jr., Vela DC, Holland CK. Clot retraction affects the extent of ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis in an ex vivo porcine thrombosis model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39(5):813–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luyckx V, Dolmans MM, Vanacker J, Scalercio SR, Donnez J, Amorim CA. First step in developing a 3D biodegradable fibrin scaffold for an artificial ovary. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuki I, Kan I, Vinters HV, Kim RH, Golshan A, Vinuela FA, et al. The impact of thromboemboli histology on the performance of a mechanical thrombectomy device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(4):643–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]