Abstract

Purpose:

Emerging evidence suggests that limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) impacts domain-specific literacy, a complex ability not assessed in traditional cognitive evaluations. We examined longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy in relation to LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC).

Participants:

275 community-dwelling older persons who had completed annual literacy assessments, died and undergone brain autopsy.

Methods:

Financial and health literacy was assessed using a 32-item instrument. Latent class mixed effects models identified groups of individuals with distinct longitudinal literacy profiles. Regression models examined group differences in 9 common age-related neuropathologies assessed via uniform structured neuropathologic evaluations.

Results:

Two distinct literacy profiles emerged. The first group (N=121, 44%) had higher level of literacy at baseline, slower decline and less variabilities over time. The second group (N=154, 56%) had lower level of literacy at baseline, faster decline, and greater variabilities. Individuals from the latter group were older, with fewer years of education and more female. They also had higher burdens of AD and LATE-NC. The group association with AD was attenuated and no longer significant after controlling for cognition. By contrast, the association with LATE-NC persisted.

Conclusion:

LATE is uniquely associated with distinct longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy in old age.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, Domain-specific literacy

INTRODUCTION

TAR DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43) proteinopathy is common in the aging brain. The pathology is present in more than 40% of community-dwelling persons past 80 years of age, and the percentage is higher among the oldest old (90+)1,2. TDP-43 pathology exacerbates loss of cognition and increases the risk of dementia above and beyond other comorbid neurodegenerative conditions including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Lewy bodies3. A recent consensus working group coined the term limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) to describe TDP-43 pathology localized in the limbic region and beyond with or without co-existing hippocampal sclerosis2. Following the same terminology, we further define the neuropathologic change of LATE as LATE-NC. While prior evidence suggests that LATE-type diseases (e.g. hippocampal sclerosis of aging) may present distinct neurocognitive patterns4,5, LATE is preferentially involved in amnestic syndromes including decline in episodic memory, the clinical hallmark of AD6,7. As such, it is difficult to distinguish the cognitive profile of LATE from that of AD8, and identifying a discernable neurobehavioral signature of LATE is needed to facilitate differential diagnosis in a clinical setting.

Recent evidence from cross-sectional work suggests that LATE-NC impacts financial and health literacy independent of cognition and AD pathology9. Domain-specific literacy, particularly financial and health literacy, involves the ability to acquire and utilize domain-specific knowledge to make advantageous decisions, and requires functional connectivity across multiple brain regions and coordination of various neural systems10. Therefore, financial and health literacy may represent a high-order neurobehavioral function that extends beyond traditional aspects of cognition and is more sensitive to neurodegeneration. Notably, the previous finding on neuropathologic correlates of literacy was limited to cross-sectional data. The longitudinal profile of financial and health literacy in old age remains unknown, and the associations of change in financial and health literacy with LATE-NC and other common neuropathologies have not been investigated.

In this study, by leveraging annual literacy assessments from 275 community-dwelling older persons who were followed up to 10 years, died and underwent brain autopsy, we first characterized the longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy. Next, we examined the differences in common age-related neuropathologies between groups with distinct longitudinal profiles of literacy. Building upon our previous cross-sectional findings, we hypothesize that LATE-NC is implicated in longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy.

METHODS

Participants

The Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a clinical-pathologic cohort study of aging and dementia, provided the data for this study. MAP, started in 1997, recruits older lay persons throughout the greater Chicago area11. Participants enrolled without known dementia and agreed to annual clinical evaluations and organ donation after death. As part of a decision making substudy, financial and health literacy assessment was implemented in 2010. By December 2, 2019, 1,250 eligible participants had completed baseline literacy assessment. We excluded 42 participants who were demented by the time of literacy assessment and 200 who did not have follow-up assessments. Of the remaining 1,008, 275 participants had died and undergone brain autopsy. The analyses were performed using the data from this autopsied group. Both the parent study and decision making substudy were approved by an institutional review board of the Rush University Medical Center. Written informed consents and an anatomical gift act were obtained from each participant.

Financial and Health Literacy

Financial and health literacy were assessed using a 32-item instrument, as previously described12. Briefly, financial literacy was measured using 23 items, which were adapted from the Health and Retirement Study. These items assess numeracy and knowledge of financial concepts and institutions (e.g. stocks, bonds, compound interest, and the FDIC). Health literacy was measured using 9 items, which assesses knowledge of Medicare and Medicare Part D, following prescription instructions, leading causes of death among older persons, and understanding risk of drugs. Each item was scored as correct or incorrect. Financial and health literacy scores were computed as the percent correct out of total items within each domain (ranging from 0–100), which were then averaged to obtain a total literacy score. Higher scores represent higher financial and health literacy.

Cognitive Function and Alzheimer’s Dementia

Cognitive function was assessed using a battery of 19 cognitive performance tests that are widely used in the field. These tests emphasize traditional cognitive aspects of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed and visuospatial ability. To minimize random variability and floor/ceiling effects of individual tests, a composite score was used to summarize the cognitive performance. Briefly, raw scores on each test were standardized using the baseline mean and standard deviation of the cohort. Standardized scores from the 19 tests were then averaged to yield a single composite score for global cognition13. Higher score represents higher cognitive function. Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis follows the modified NINCDS/ADRDA criteria14, which requires a history of cognitive decline, and impairment in memory and at least one other cognitive domain.

Neuropathologic Evaluation

Neuropathologic evaluation was performed by examiners blinded to all clinical data. Brains were removed following standard procedures with cerebral hemispheres cut into 1cm coronal slabs. Slabs from one hemisphere were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and dissected for histopathology assessment. Measures on 9 common age-related pathologies, including AD, LATE-NC, hippocampal sclerosis, Lewy bodies, chronic macroscopic and micro infarcts, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis, were obtained following uniform structured evaluations.

Global burden of AD pathology was measured as previously described15. Briefly, tissues from 5 brain regions (midfrontal, middle temporal, entorhinal and parietal cortices, and hippocampus) were sectioned at 6μm and stained using a modified Bielschowsky silver stain. For each brain region, neuritic plaques, diffuse plaques and neurofibrillary tangles were counted in a 1mm2 area of greatest density. Region-specific counts for each AD index were scaled and averaged across brain regions to obtain a summary score for neuritic plaques, and separately diffuse plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The three summary scores were averaged to yield a composite score of global AD pathology. Pathologic diagnosis of AD followed modified NIA-Reagan criteria16. TDP-43 was quantified in 8 brain regions (amygdala, entorhinal cortex, hippocampus CA1 and dentate gyrus, anterior temporal pole, inferior frontal, midfrontal and midtemporal cortices) with monoclonal antibodies1. For each region, the number of TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions (both neuronal and glial) in a 0.25mm2 area of greatest density was summarized into a semiquantitative rating between 0 and 61. Following the recommendation by the consensus committee2, LATE-NC was defined in 3 stages, i.e. localization of TDP-43 in amygdala only (Stage 1), extension to other limbic regions including hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Stage 2), and finally extension to neocortices (Stage 3). Hippocampal sclerosis, defined as significant neuronal loss and gliosis in the hippocampus and subiculum, was identified unilaterally with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain17. Lewy bodies were identified with antibodies to α-synuclein in 7 regions including amygdala, substantia nigra, limbic and neocortices. Hippocampal sclerosis and Lewy bodies were measured as presence versus absence.

The presence of chronic infarcts was recorded. Macroscopic infarcts were identified during gross examination and confirmed histologically18. Microinfarcts were examined in at least 9 brain regions using H&E stained sections19. Meningeal and parenchymal vessels in 4 brain regions (midfrontal, inferior temporal, angular gyrus, and calcarine cortices) were assessed for amyloid deposition with immunohistochemistry20. Cerebral arteries and proximal branches in the circle of Willis were visually inspected for atherosclerosis21, and vessels in the anterior basal ganglia were examined for arteriolosclerosis using H&E stained sections22. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis were rated as none, mild, moderate and severe.

Statistical Analysis

To characterize longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy, we analyzed data from annual literacy assessments over multiple years using a latent class mixed effects model23. We hypothesize that there are K groups of distinct profiles of literacy and each differs in the mean baseline level, mean rate of change over time, as well as between-person and between-assessment variabilities. The optimal number of K was determined empirically using the model fit statistic of Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). After the optimal number of latent classes was identified, posterior probabilities estimated the likelihood of individuals belonging to each of the identified classes, and the class membership was determined based on the largest probability. We examined the associations of literacy profiles with common neuropathologies using a series of linear (continuous measures) and logistic regression (binary or ordinal measures) models, adjusted for age, sex and education. As the relationship between literacy and neuropathology could be confounded by cognition, subsequent analyses further controlled for the global cognition proximate to death.

The latent class mixed-effects models were fit using Mplus software, version 5.2. Regression analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined at α level of 0.05 unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study participants are described (Table 1). Briefly, the mean baseline age was 86 years and the mean years of education was 15 years. Approximate three quarters were female and almost all were non-Latino whites. Participants died at an average age of 91 years and a third of those were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia at death. Over 60% met the modified NIA-Reagan criteria for pathologic AD. Other non-AD neurodegenerative conditions were less frequent. Lewy bodies were observed in nearly a quarter of the individuals, a third had LATE-NC stage 2 or 3, and less than 10% had hippocampal sclerosis. Cerebrovascular conditions were common. Chronic macroscopic or microinfarcts were observed in about 57% of the individuals. Over a third of individuals show moderate or severe amyloid angiopathy, 16% show moderate or severe atherosclerosis and 22% show moderate or severe arteriolosclerosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (N=275)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or N (percent) |

|---|---|

| Age at baseline | 86.1 (5.8) |

| Age at death | 91.3 (6.0) |

| Education | 15.1 (2.9) |

| Female | 199 (72.4%) |

| Non-Hispanic whites | 267 (97.1%) |

| Total literacy at baseline | 63.7 (13.7) |

| Total literacy proximate to death | 57.2 (17.3) |

| Global cognition at baseline | 0.04 (0.50) |

| Global cognition proximate to death | −0.68 (0.99) |

| MMSE at baseline | 27.8 (1.9) |

| MMSE proximate to death | 22.6 (7.9) |

| Alzheimer’s dementia at death | 90 (33.1%) |

| Pathologic AD (NIA Reagan) | 156 (61.9%) |

| Macroscopic infarcts | 93 (37.2%) |

| Microinfarcts | 94 (37.6%) |

| Lewy bodies | 60 (23.8%) |

| 3 | 59 (23.7%) |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 18 (7.4%) |

| Severe | 36 (14.3%) |

| Severe | 1 (0.4%) |

| Severe | 11 (4.4%) |

LATE-NC stage: 1=TDP-43 localized in amygdala only; 2=extension to other limbic regions; 3=extension to neocortical regions

Distinct Longitudinal Profiles of Financial and Health Literacy

The participants completed up to 10 annual literacy assessments (Median: 4, Interquartile range: 3–6). We fit a series of latent class mixed effects models by sequentially increasing the number of classes starting from K=1. The BIC statistic reached the minimum at K=2, suggesting that the 2-class model had the optimal fit to the data.

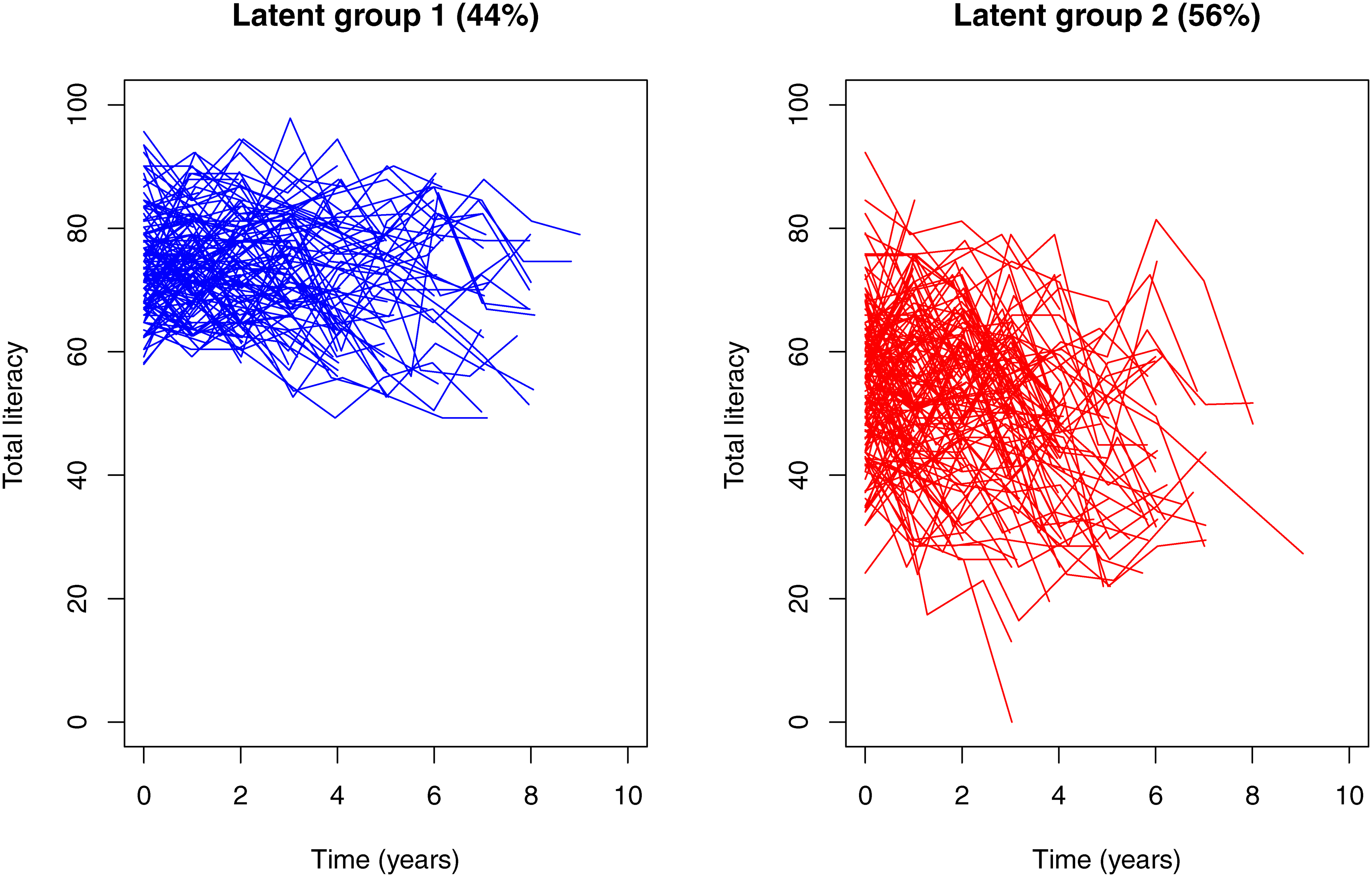

Two distinct profiles of longitudinal financial and health literacy were identified (Figure 1). The first (high performance) group, which consisted of approximately 44% of the participants (N=121), showed a relatively higher level of baseline literacy, slower decline and less between-person and between-assessment variabilities. Specifically, the mean baseline literacy score of this group (Estimate: 74.1%, Standard error (SE): 1.5%, p<0.001) was 10 percentage points higher than the overall sample, and there was a nominal decline in literacy over time such that the literacy score decreased by about 1 percentage point every year (Estimate for annual rate of decline: −0.75, SE: 0.28, p=0.009). Further, the between-person and between-assessment variabilities of the literacy scores were smaller compared to the other group (Table 2). In this high literacy performance group, the average age at baseline was about 84.6 years (SD: 6.0) and the average age at death was 90.2 years (SD: 6.2). The average years of education was 16.1 years (SD: 2.5), and 61.2% were female.

Figure 1.

Distinct profiles of longitudinal financial and health literacy by latent groups. The figure illustrates the observed person-specific longitudinal trajectories for high literacy performance (left panel) and low performance (right panel).

Table 2.

Key features of literacy profile by latent groups

| Latent group 1 (44%) | Latent group 2 (56%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Intercept | 74.1 (1.51), <.001 | 57.9 (1.64), <.001 |

| Mean Slope | −0.75 (0.28), 0.009 | −2.59 (0.35), <.001 |

| Variance of random intercept | 41.7 (11.0), <.001 | 106.5 (17.4), <.001 |

| Covariance of intercept & slope | 1.97 (1.86), 0.291 | −0.20 (4.45), 0.971 |

| Variance of random slope | 0.66 (0.35), 0.063 | 2.95 (1.73), 0.089 |

| Residual variance | 37.6 (5.4), <.001 | 75.4 (5.83), <.001 |

The statistics in each cell were point estimate (standard error), p value.

The second (low performance) group consisted of a majority of the participants (N=154, 56%). These participants performed relatively poorly, with an average baseline literacy score about 6 percentage points lower than the overall sample (Estimate: 57.9%, SE: 1.6, p<0.001), and the literacy score decreased by more than 2 percentage points every year (Estimate for annual rate of decline: −2.59, SE: 0.35, p<0.001). Participants in this group also showed larger between-person and between-assessment variabilities. Participants in the low literacy performance group were older. The average age at baseline was 87.3 years (SD: 5.4) and the average age at death was 92.2 years (SD: 5.8). Participants also had fewer years of education (Mean: 14.3 years, SD: 2.8), and a larger proportion were female (81.2%).

A total of 90 Alzheimer’s dementia cases (33.2%) were reported at death, and a marked difference was observed by the literacy grouping. Among the group with high literacy performance (i.e. higher baseline literacy, slower decline and less variability in longitudinal literacy), only 15 (12.7%) developed Alzheimer’s dementia. By contrast, the number of Alzheimer’s dementia cases increased to 75 (49.0%) for the low performance group (i.e. lower baseline literacy, faster decline and larger variability in longitudinal literacy). In a logistic regression model adjusted for demographics and baseline cognition, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia was more than tripled for individuals in the low literacy performance group (Odd ratio [OR]: 3.40, 95% Confidence interval [CI]: 1.65–7.00). Of note, this result was independent of the established association of cognition with Alzheimer’s dementia (OR: 0.17, 95% CI: 0.08–0.35).

Common Neuropathologies by Financial and Health Literacy Profiles

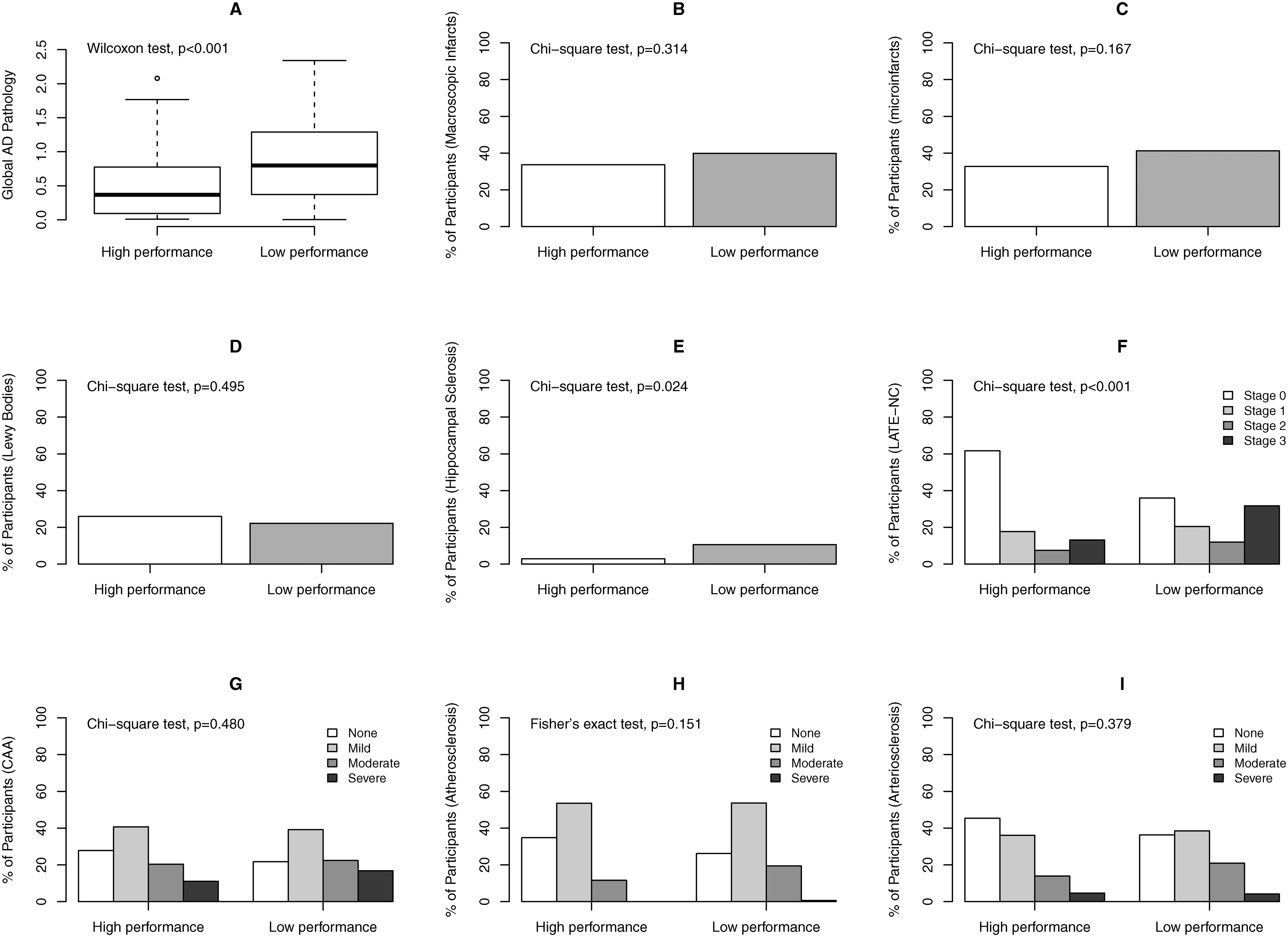

Neuropathologic burdens between the groups with distinct longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy are shown in Figure 2. We examined the group difference for each of the neuropathologic indices in a series of regression models after adjusting for age, sex and education. In these analyses, statistical significance was determined at α level of 0.005 in order to correct for multiple testing of 9 neuropathologic indices. Regression analyses showed that, compared to the high financial and health literacy performance group, individuals with low literacy performance had more AD pathology (β coefficient: 0.19, SE: 0.05, p<0.001). Separately, the odds of having more severe LATE-NC was tripled for participants with low literacy performance (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.84–5.38). The low literacy performance groups also show higher odds of hippocampal sclerosis, but the result didn’t reach the statistical cut-off after multiple testing correction. No statistically significant associations were observed for other pathologic indices (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Burdens of common neuropathologies by literacy performance groups. The figure shows distributions of common neuropathologic indices between the groups of high and low literacy performance. Panel A: boxplot for global burden of AD pathology; Panel B through Panel I: bar charts for percent participants with chronic macroscopic infarcts (B), chronic microinfarcts (C), neocortical Lewy bodies (D), hippocampal sclerosis (E), LATE-NC (F), amyloid angiopathy (G), atherosclerosis (H) and arteriolosclerosis (I). Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test compared the unadjusted group difference for each neuropathologic index.

Table 3.

Association of latent class with neuropathologic indices

| Neuropathologic indices | Estimate (96% Confidence interval) |

|---|---|

| Global AD pathology1 | 0.192 (0.095–0.289) |

| LATE-NC2 | 3.144 (1.836–5.384) |

| Hippocampal sclerosis2 | 5.001 (1.295–19.31) |

| Lewy bodies2 | 1.023 (0.535–1.953) |

| Macroscopic infarcts2 | 1.082 (0.610–1.919) |

| Microinfarcts2 | 1.268 (0.716–2.243) |

| Amyloid angiopathy2 | 1.352 (0.823–2.223) |

| Atherosclerosis2 | 1.278 (0.757–2.157) |

| Arteriolosclerosis2 | 1.068 (0.640–1.782) |

Linear regression;

logistic regression

The point estimates (beta coefficient for linear regression and odds ratio for logistic regression) in each cell were obtained from separate regression models, adjusted for age at death, sex and education. The beta coefficient estimates the between-group difference in the composite score of global AD pathology, and the odds ratio compares the odds of having corresponding neuropathology (or the odds of having more severe neuropathology for semiquantitative measure) between participants with low literacy performance and high performance (reference).

LATE-NC is a semiquantitative measure coded as Stage 0: no TDP-43 inclusion, Stage 1: inclusion limited to amygdala, Stage 2: inclusion extended to other limbic regions, and Stage 3: inclusion extended to neocortical regions. Amyloid angiopathy, atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis are semiquantitative measures coded as 0: none, 1: mild, 2: moderate and 3: severe.

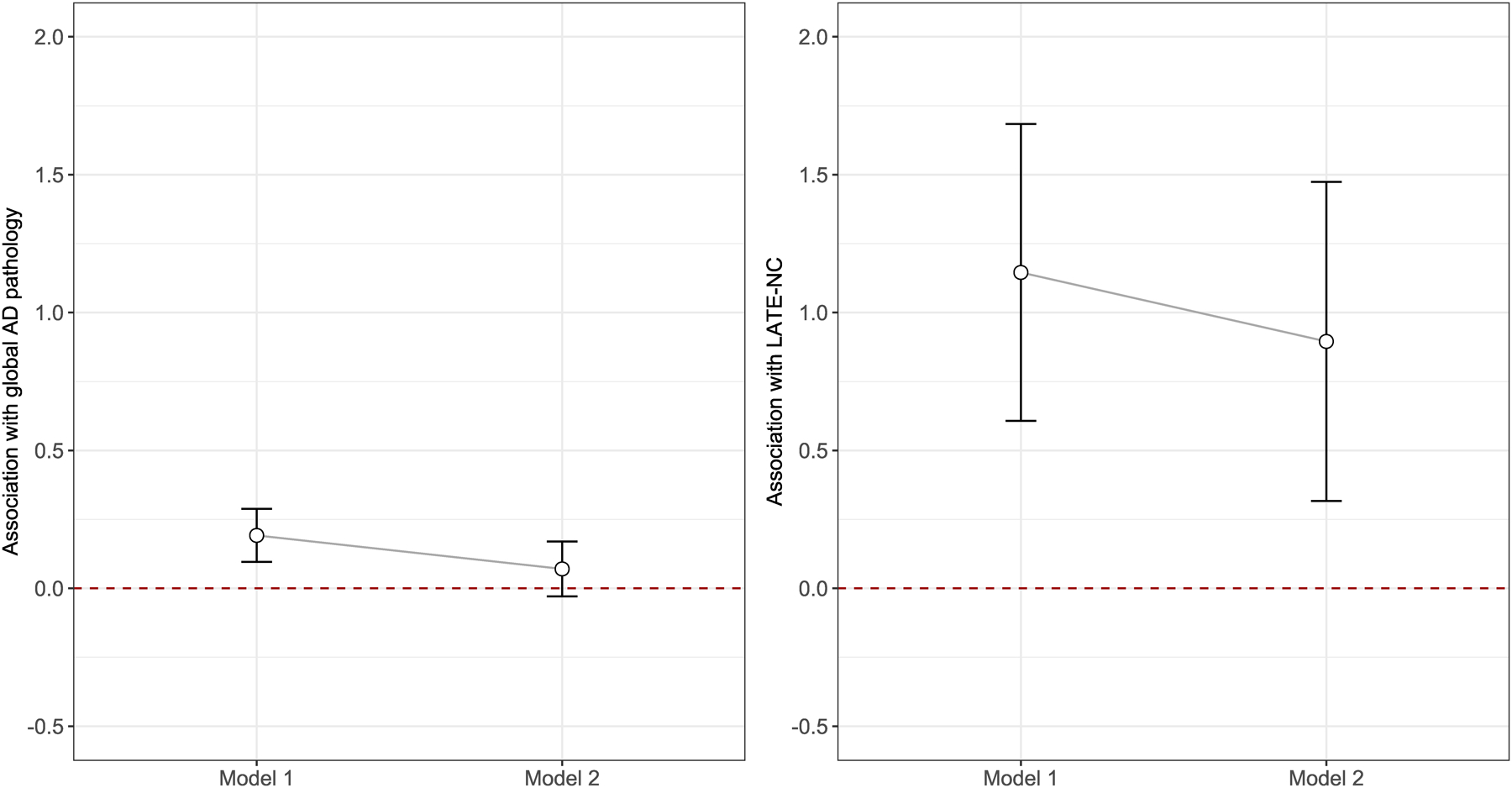

Finally, literacy performance is strongly correlated with cognition. Therefore, we examined whether the associations of financial and health literacy profiles with AD and LATE-NC were confounded by cognition. We repeated the regression analysis for AD, and separately LATE-NC, by further adjusting for global cognition proximate to death (Figure 3). The association with AD was attenuated and no longer significant (β coefficient: 0.07, SE: 0.05, p=0.165). This result suggests that the observed difference in AD pathology between high and low literacy performance groups was confounded by the association of cognition and AD. In a similar analysis for LATE-NC, after controlling for global cognition, the association with LATE-NC remained significant (OR: 2.45, 95% CI: 1.37–4.37), a result suggesting that LATE-NC is uniquely implicated in distinct longitudinal profiles of financial and health literacy in old age.

Figure 3.

Difference in burdens of AD and LATE-NC by literacy performance groups. The figure illustrates the difference in burdens of AD (left panel) and LATE-NC (right panel) by literacy performance groups in the models without (Model 1) and with (Model 2) the adjustment for cognition. The point estimate (regression coefficient for AD model, and log odd ratio for LATE-NC model), shown as open circle, corresponds to the additional burden of each pathology for the low literacy performance group. The error bar is calculated using +/− 1.96 times corresponding standard errors.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined longitudinal change in financial and health literacy using data from 275 community-dwelling older persons who were followed annually for up to 10 years, died and underwent brain autopsy. Two distinct longitudinal profiles of literacy emerged. The high performance group was characterized by higher than average literacy level at baseline, slower decline and less between-person and between-assessment variabilities. The low performance group was characterized by lower baseline level of literacy, faster decline and larger variabilities. Participants in the low performance group were substantially more likely to develop Alzheimer’s dementia. The neuropathologic correlates of distinct longitudinal literacy profiles include AD and LATE-NC. Interestingly, however, the association of the literacy profiles with AD pathology was primarily driven by cognition. By contrast, the low literacy performance group had greater odds of having more severe LATE-NC above and beyond the association of cognition, suggesting that the association of financial and health literacy with LATE-NC is relatively unique.

These findings have several important implications. First, this study provides novel information regarding age-related change in financial and health literacy, abilities that are critical for maintaining independence and wellbeing in old age. Prior research has shown that low literacy is associated with poor decision making and increased risks of adverse health outcomes, especially among the aged population. However, despite increasing recognition that poor literacy poses a critical public health challenge, longitudinal change in literacy has not been well characterized. We previously reported that, on average, financial and health literacy decline 1 percentage point each year, suggesting literacy deteriorates over time in old age24. Here, we extend this prior finding. First, this study analyzed data from a group of participants who had died and undergone brain autopsy, which allowed us to capture the entire history of their longitudinal change in financial and health literacy. Second, our analytic approach relaxed the assumption that late-life change in literacy follows a homogenous pattern and specifically aimed to identify groups of persons with distinct literacy profiles. Third, instead of focusing only on the rate of decline, we characterized the profile of literacy by incorporating multiple key features of longitudinal change in literacy, including baseline level, rate of decline as well as between-person and between-assessment variabilities. Building on our previous report, the current study showed that in this autopsied group, almost all the participants experienced some degree of decline in financial and health literacy. This finding informs on the large scope of age-related decline in domain-specific literacy. Further, by classifying participants based on distinct literacy profiles, our findings facilitate future research on the underlying neurobiologic and behavioral basis of age-related change in literacy and may inform efforts to identify modifiable factors that maintain or boost literacy performance in older age.

The current study expands upon previous cross-sectional work by investigating the relationship between common age-related neuropathologies and longitudinal profiles of literacy. Our results show that participants in the low literacy performance group tend to have higher burdens of AD pathology and LATE-NC. While it is acknowledged that common age-related neuropathologies are the key drivers of cognitive decline in old age, the impact of these neuropathologies on change in other neurobehavioral abilities such as domain-specific literacy has not been examined. Findings from this study provide new evidence that neuropathologies affect a broader spectrum of behaviors than currently recognized, including change in financial and health literacy. Of note, the current analysis incorporates three key features in profiling the longitudinal change in literacy; it may be of interest for future studies to examine the extent to which neuropathologies are differentially associated with each of the individual features.

Separately, our findings suggest that neuropathologic correlates of the longitudinal profile of domain-specific literacy are distinct from those of traditionally measured cognition. We and other have consistently shown that a wide range of neurodegenerative and vascular conditions are implicated in late-life cognitive decline25. In addition, it is reported that AD and Lewy bodies are the main contributors of yearly fluctuation in cognition26. Different from the results for cognition, however, the current study highlights the specific role of LATE-NC in relation to profiles of domain-specific literacy. Whether the neuropathologic correlates of financial and health literacy are confined to LATE-NC requires further examination in independent clinical-pathologic studies.

Our findings suggest that neurobehavioral measures that assess complex abilities not typically assessed in clinical settings, particularly financial and health literacy, may hold the potential to aid in the assessment and diagnosis of LATE-related syndromes. To date, there is little to no clinical recognition of LATE-NC and no current means for in-vivo diagnosis. In this study, we observed associations of AD pathology and LATE-NC with distinct literacy profiles. After further controlling for cognition, however, only the result for LATE-NC persisted, suggesting that the impact of LATE-NC on change in literacy is unique and may extend beyond its impact on more traditional aspects of cognition. This result is of particular importance because, despite increasing recognition of LATE as a common disease with deleterious consequences in aging, identification of neurobehavioral features specific to LATE-NC has proven to be challenging. Most prior work suggests that in older persons LATE is primarily characterized by impairment and decline in episodic memory, the clinical hallmark of AD. Thus, it is difficult to distinguish LATE from AD in a clinical setting. Some prior work suggests patients with TDP-43 have later onset and worse cognitive performance compared to those without TDP-4327, and that neuropsychiatric symptoms may differ by TDP-43 status such that TDP-43 positivity is linked to more severe aberrant motor behavior and less severe depression28; notably however, those studies were restricted to patients with AD. In this study, we show that, among older persons initially free of dementia, those who have low literacy levels, fast decline in literacy, and high variability between assessments have higher risk of having more severe LATE-NC. Our finding suggests that longitudinal profiles in domain-specific literacy in old age may be relatively unique to LATE-NC and opens a new venue for exploring both better measures of literacy and novel neurobehavioral signatures of LATE.

Strength and limitations are noted. We are not aware of any study that has characterized longitudinal change in financial and health literacy and examined the neuropathologic correlates of distinct longitudinal profiles of literacy. The instrument for literacy assessment has adequate internal consistency and the measures have shown robust associations with various adverse health outcomes. Uniform structured postmortem evaluations provide systematic and comprehensive documentation of pathologic indices common in aging brain. The novel analytic approach characterizes distinct profiles of literacy by incorporating multiple features from longitudinal measures of literacy. This study also has important limitations that may affect generalizability of our findings. First, the majority of participants are non-Latino whites. Literacy assessment was recently introduced to an African American cohort and data collection is ongoing. Second, all participants are organ donors in order to be included in the MAP cohort, and participants in general are older with higher education than general population. It is also important to note that while this study demonstrates that poor literacy performance is indicative of LATE-NC in the brain, future work is needed for defining a comprehensive profile that integrates neurobehavioral, genetic, neuropathologic and imaging markers. Finally, our current financial and health literacy instrument was not specifically designed for use in detecting LATE-NC, and additional studies are warranted to evaluate the utility of this or other related measures as a potential clinical marker for the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The study is funded by the National Institute on Aging Grants (R01AG17917, R01AG042210, R01AG33678, and R01AG34374). We are indebted to thousands of participants from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. We also thank investigators and staff at Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (RADC). Data in this work can be requested via Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center Research Resource Sharing Hub (www.radc.rush.edu).

The study was funded by National Institute on Aging Grants (R01AG17917, R01AG042210, R01AG33678, and R01AG34374)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: No relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nag S, Yu L, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology in anterior temporal pole cortex in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica communications. May 1 2018;6(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain. June 1 2019;142(6):1503–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). January 2010;20(1):66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta neuropathologica. August 2013;126(2):161–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray ME, Cannon A, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Differential clinicopathologic and genetic features of late-onset amnestic dementias. Acta neuropathologica. September 2014;128(3):411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nag S, Yu L, Wilson RS, Chen EY, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology and memory impairment in elders without pathologic diagnoses of AD or FTLD. Neurology. February 14 2017;88(7):653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RS, Yang J, Yu L, et al. Postmortem neurodegenerative markers and trajectories of decline in cognitive systems. Neurology. February 19 2019;92(8):e831–e840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, et al. TDP-43 is a key player in the clinical features associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127(6):811–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapasi A, Yu L, Stewart CC, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Association of TDP-43 Pathology With Domain-specific Literacy in Older Persons. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. July 10 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han SD, Boyle PA, Yu L, et al. Financial literacy is associated with medial brain region functional connectivity in old age. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. Sep-Oct 2014;59(2):429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Current Alzheimer research. July 2012;9(6):646–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett JS, Bennett DA. The impact of health and financial literacy on decision making in community-based older adults. Gerontology. 2012;58(6):531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, et al. Temporal course and pathologic basis of unawareness of memory loss in dementia. Neurology September 15 2015;85(11):984–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology July 1984;34(7):939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Memory complaints are related to Alzheimer disease pathology in older persons. Neurology. November 14 2006;67(9):1581–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. June 27 2006;66(12):1837–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nag S, Yu L, Capuano AW, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis and TDP‐43 pathology in aging and Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2015;77(6):942–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Cochran EJ, et al. Relation of cerebral infarctions to dementia and cognitive function in older persons. Neurology. April 08 2003;60(7):1082–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. March 2011;42(3):722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu L, Boyle PA, Nag S, et al. APOE and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in community-dwelling older persons. Neurobiology of aging. 2015;36(11):2946–2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The Relationship of Cerebral Vessel Pathology to Brain Microinfarcts. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). January 2017;27(1):77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. Neurology August 2016;15(9):934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu L, Boyle PA, Segawa E, et al. Residual decline in cognition after adjustment for common neuropathologic conditions. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(3):335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu L, Wilson RS, Han SD, Leurgans S, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Decline in Literacy and Incident AD Dementia Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons. Journal of Aging and Health. 2017:0898264317716361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old age. Ann Neurol. January 2018;83(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu L, Wang T, Wilson RS, et al. Common age-related neuropathologies and yearly variability in cognition. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. November 2019;6(11):2140–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, et al. Abnormal TDP-43 immunoreactivity in AD modifies clinicopathologic and radiologic phenotype. Neurology. May 6 2008;70(19 Pt 2):1850–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayram E, Shan G, Cummings JL. Associations between Comorbid TDP-43, Lewy Body Pathology, and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. May 20 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]