Abstract

In positron emission tomography (PET), the finite range over which positrons travel before annihilating with an electron places a fundamental physical limit on the spatial resolution of PET images. After annihilation, the photon pair detected by the PET instrumentation is emitted from a location that is different from the positron-emitting source, resulting in image blurring. Here, we report on the localization of positron range, and hence annihilation quanta, by strong nanoscale magnetization of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) in PET-MRI. We found that positron annihilations localize within a region of interest by up to 60% more when SPIONs are present (with [Fe] = 3 mM) compared to when they are not. The resulting full width at half maximum of the PET scans showed the spatial resolution improved by up to 30%. We also found evidence suggesting that the radiolabeled SPIONs produced up to a six-fold increase in ortho-positronium. These results may also have implications for emerging cancer theranostic strategies, where charged particles are used as therapeutic as well as diagnostic agents and improved dose localization within a tumor is a determinant of better treatment outcomes.

Subject terms: Biological physics, Nanomedicine, Diagnostic devices, Imaging techniques and agents, Nanotechnology in cancer

Introduction

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is an essential medical imaging technology for detecting and diagnosing diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s1,2. It works by detecting pairs of photons emitted following electron–positron annihilation inside the body after administration of a positron-emitting radiopharmaceutical. Although PET is a widely available clinical technology, its accuracy is limited by the spread in positron range, the distance a positron travels before it annihilates. This imposes a fundamental physical limit on the spatial resolution of PET images, a problem that has been studied for many years1, 3–5. The spatial resolution of PET imaging is also limited by lack of collinearity of the annihilation photons and other instrument related factors such as detector size and material, as well as off-axis detector penetration. Since the overall resolution is a convolution of these factors, improvement of the positron range in conjunction with advances in the state-of-the-art detector technology can enhance the PET spatial resolution significantly6. Improving the spatial resolution of PET images would improve diagnostic accuracy and would also improve emerging cancer treatment strategies using theranostic radiopharmaceuticals (isotopes delivering both therapeutic and diagnostic benefits). Here we report, for the first time, on the impact of nanoscale magnetization by superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) on the range of positrons in PET imaging. Using PET-MRI, a dual-mode technology combining PET with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), we found that SPIONs labeled with a PET tracer can localize positron range by their strong nanoscale magnetization, producing images with noticeably improved spatial resolution.

Depending on the parent nucleus, emitted positrons can have mean and endpoint energies ranging from 0.3 meV and 0.6 meV (for the most commonly used tracer, 18F) to 1.5 meV and 3.35 meV (for 82Rb), respectively. This corresponds to mean and maximum positron ranges of 2.4 and 17 mm, and 0.6 and 7.1 mm in tissue, with values in between for other commonly used isotopes (e.g. 89Zr, 68Ga, 11C)7,8. After thermalization, annihilation with an electron can occur either instantaneously, or can be delayed by the formation of a meta-stable intermediate positronium () state9. In PET, coincidence detection of counter-propagating 511 keV annihilation photon pairs enables reconstruction of a three-dimensional (3D) image of the source region. The position of where these annihilation photons are created is different from the position of the parent nucleus, resulting in image blurring1,3. Recently, we showed that by delivering the PET tracer using SPIONs, PET-MRI technology can be leveraged to achieve better overall image quality by integrating the high sensitivity of PET with the high spatial resolution of MRI10 (see Fig. 1). In that study, the strong local magnetization of SPIONs enhanced MRI contrast by shortening the transverse (spin–spin) relaxation time of protons in surrounding water molecules. Here, we show that the strong nanoscale magnetization of SPIONs labeled with a PET tracer can also improve PET spatial resolution by localizing positron range and hence, the distribution of annihilation photons.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the use of a radiolabeled magnetized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle for simultaneous multimodal imaging (MRI magnetic resonance imaging, PET positron emission tomography).

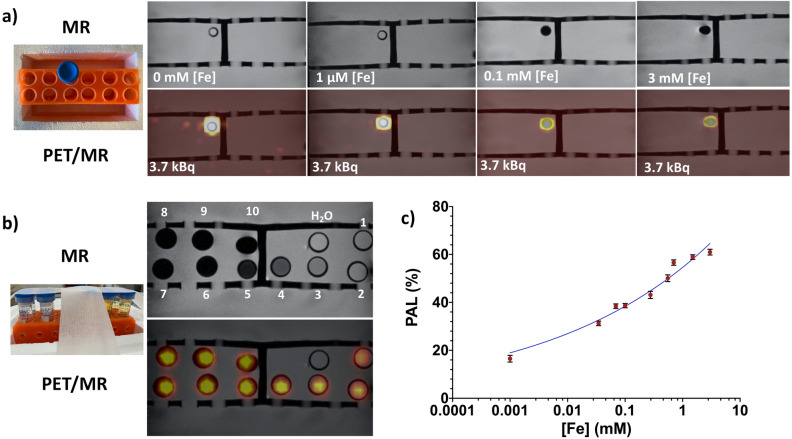

A series of [Fe] dilutions (i.e. 0.001–3 mM, see Table 1) of 89Zr-SPION samples was prepared in 10 separate phantom vials (including 89Zr-water). The activity of 89Zr (half-life 74.4 days) in each phantom was kept constant, A0 = 3.7 kBq. Phantoms were scanned using a clinical PET-MRI scanner and images are shown in Fig. 2a,b. The top and bottom panels in Fig. 2a show individual close-ups of the T2*-Weighted (T2*-W) MRI and co-registered PET-MRI phantom images for four 89Zr-SPION [Fe] concentrations, respectively. Figure 2b shows images for all [Fe] SPION concentrations. MRI images of phantoms containing 89Zr-water (i.e. Fig. 2b phantom #1 0 mM [Fe]) and 1 µM [Fe] 89Zr-SPION (Fig. 2b phantom #2) did not show contrast against background water. However, at [Fe] = 0.1 mM (Fig. 2b phantom #5), the concentration was sufficient to cause strong dark contrast against water and at [Fe] = 3 mM, a geometric distortion of the image is discernable (Fig. 2b, phantom #10). This is due to a large magnetic susceptibility difference at the phantom boundary. The distortion is also evident in the PET-MRI images at [Fe] = 3 mM, indicating that the nanoscale amplification of magnetic field by the SPIONs restricts positron range. The integrated PET signal intensity for a circular region of interest for each phantom scan was calculated (see “Methods” section) to quantify this positron annihilation localization (PAL) effect (Fig. 2c).

Table 1.

List of 89Zr-SPION [Fe] concentrations in each phantom and the percentage changes in the true and random counts for the phantom PET scans shown in Fig. 3a–d.

| Phantom number | [Fe] mM | 89Zr A0 (kBq) | PAL (%) | True (%) | Random (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.000 | 3.70 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.001 | 3.70 | 16.52 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 5.10 ± 0.02 |

| 3 | 0.034 | 3.70 | 31.24 | ||

| 4 | 0.069 | 3.70 | 38.40 | ||

| 5 | 0.100 | 3.70 | 38.64 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 6.00 ± 0.02 |

| 6 | 0.277 | 3.70 | 43.12 | ||

| 7 | 0.553 | 3.70 | 50.09 | ||

| 8 | 0.700 | 3.70 | 56.61 | ||

| 9 | 1.500 | 3.70 | 58.90 | ||

| 10 | 3.000 | 3.70 | 60.96 | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 6.30 ± 0.02 |

Figure 2.

MR and co-registered PET/MR images. (a) Top and bottom panels show close-ups of T2*W MR and PET/MR phantom images for four of the 89Zr-SPION [Fe] concentrations, respectively. (b) MR and PET/MR images for all ten 89Zr-SPION [Fe] concentrations (listed in Table 1). (c) Plot of positron annihilation localization (PAL) as a function of [Fe].

Although the lowest PAL occurred at [Fe] = 1 µM where SPION magnetization was insufficient to produce an obvious negative contrast against the background water, a ≈ 16% PAL was still observed. The nanoscale magnetic field gradient induced by SPIONs is strongly depended on its saturation magnetization and magnetic properties11–14. For instance, SPIONs in the low 1 µM [Fe] solution phantom (containing ≈ 2 × 1015 SPIONs with minimum SPION separation core-to-core distance of approximately 20 nm15) in an external 3 T MR magnetic field, can have an induced three dimensional (3D) local magnetic field around the SPION as high as 3 T at the SPION center16–18. Thus, an emitted from the 89Zr atom at the surface of a radiolabeled 89Zr-SPION is influenced by not only the magnetic force (i.e. Lorentz force) from the magnetized SPION16 that it is labeled to but also the magnetic force of the other 2 × 1015 SPIONs in its vicinity. Collisions are suppressed in directions transverse to the local magnetic field. Therefore, compared to the 89Zr-water only phantom (i.e. the 0 mM [Fe] sample) shown in Fig. 2, phantoms with increasing magnetized 89Zr- SPION [Fe] concentrations exhibit PET signals that become increasingly spatially localized. Note this is different from the case of the Lorentz force exerted by the static magnetic field B0 of the MR magnet, which can restrict positron range in the transaxial direction, as has been reported in previous PET-MRI studies19,20. In this study, PAL is defined [cf. Eq. (1) in “Methods” section] relative to the PET signal when SPIONs are absent and thus measures the effect solely due to SPION magnetization. As demonstrated in Fig. 2c, PAL increased with [Fe] concentration of the 89Zr-SPIONs. Interestingly, our results show a significant PAL (≈ 40%) at a clinically relevant dose of 0.1 mM [Fe]21. As the presence of SPIONs increases mass density only by approximately 0.015%, the effect of collisions on positron range is negligible and thus, the observed PAL can be attributed to SPION nanoscale magnetization.

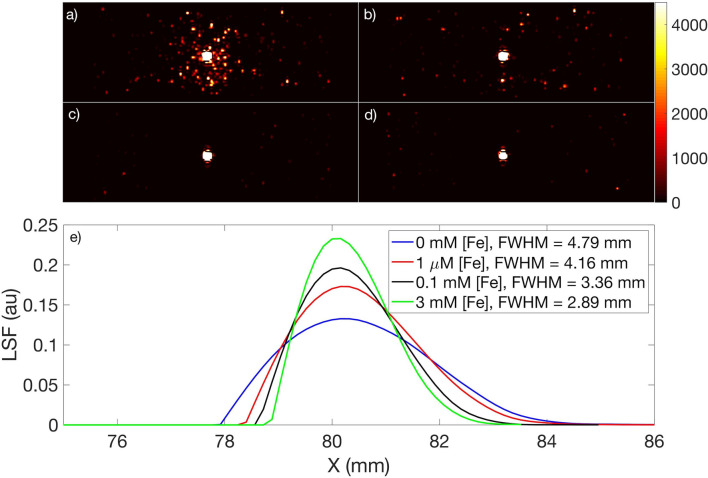

Positron range restriction was further quantified by measuring the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the PET images of the phantom vials with 89Zr in water and with 89Zr-SPIONs, with [Fe] = 0.001 mM, 0.1 mM and 3 mM (see Fig. 3a–d). These images show the distribution of positron annihilation events in water projected onto a plane (i.e. an integration of events). In comparison to the 89Zr in water image (Fig. 3a), it is evident that magnetized SPIONs increasingly localize the positron annihilation events within their vials as [Fe] increases. This is quantified with the FWHM of each line spread function (LSF, see “Methods” section) in Fig. 3e, which shows that spatial resolution improves by up to 40% in the presence of SPIONs. This can be attributed to the restriction of positron range by the strong nanoscale localization of magnetic field induced around the SPIONs in the presence of the external B0 = 3 T in the PET-MRI scanner. These results suggest that SPIONs radiolabelled with suitable PET tracers10,15,22 offer a novel approach to mitigating the well-known effect of positron range on spatial resolution in PET images1,3–5. Thus, in PET-MRI, SPIONs can not only enhance MRI contrast, but can also enhance PET spatial resolution, with the potential to improve overall image quality compared to that achieved with either modality separately.

Figure 3.

PET scans (axial view) of four vials containing 89Zr and varying amounts of SPIONs. (a) 89Zr only (i.e. 0 mM [Fe]) in de-ionized water. (b–d) 89Zr-SPION disperssion in de-ionized water with [Fe] = 0.001 mM, 0.1 mM and 3 mM, respectively. (e) The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the line spread function (LSF) calculated for each PET scan to assess the impact of magnetized SPIONs on spatial resolution. The activity of 89Zr in each phantom was kept constant, A0 = 3.7 kBq.

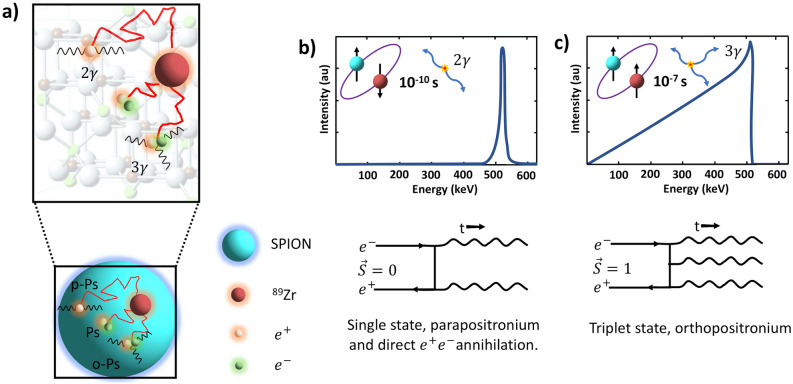

We also found an increase of up to ≈ 1% and 6% in the true and random counts, respectively, detected by the PET scanner in phantom vials containing 89Zr-SPIONs compared to 89Zr only (see Table 1). This can be attributed to the interaction of positrons within the Fe3O4 crystal structure of SPION cores resulting in annihilation via formation of ortho-positronium (o-Ps, in the triplet state, 3S1) and emission of three gammas23. Such triple-coincidences may be processed as a set of double coincidence events or detected as random counts by the PET scanner24. However, further investigation is required for more accurate quantification of o-Ps and para-positronium (p-Ps) productions in SPION dispersions. Since most of the clinical and pre-clinical PET scanners are not capable of detecting o-Ps as triplet coincidences, positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy might be the best option for accurately measuring the o-Ps yield in SPION dispersions23. Figure 4a is a schematic diagram demonstrating the possible interactions of the emitted with the radiolabeled SPIONs in water. PET is based on registration of two gamma quanta originating from positron annihilation in tissue, where the most common (≈ 70%) annihilation route for a thermalized is direct annihilation with an (see Fig. 4b). The alternate route is via formation and decay of positronium (Ps)25. Ps can decay electromagnetically into two, three or more gamma quanta depending on the Ps quantum mechanical state just prior to annihilation25. Thus the energy of three annihilation photons has a continuum spectrum (with energies between 0 and 511 keV, with sum 1022 keV), due to energy and momentum conservation26 (see Fig. 4c). Due to spin statistics, 25% of all Ps are formed in the ground state (1S0) called para-positronium (p-Ps), while the remaining 75% form the triplet state (3S1), called ortho-positronium (o-Ps). In vacuum, o-Ps can only decay into at least three photons, and its lifetime (142 ns) is much longer than that of p-Ps (125 ps) or that of a free positron25,27. In water, due to the excess of oxygen atoms, the majority of o-Ps spins are inverted and thus the effective yield of annihilation quanta into three gammas approaches ≈ 1%28. The formation of o-Ps and the 3γ/2γ yield in materials can be significantly affected by open volume defects such as in the Fe3O4 crystal structure of SPION cores23,29. The lack of collinearity of the annihilation photons due to residual momentum of the or Ps at the time of decay can also impact the spatial resolution in PET imaging. A previous study30 showed that p-Ps decays in solution have significantly more Doppler broadening of the annihilation photons compared to o-Ps and thus significantly higher residual momentum in p-Ps at the time of decay. This indicates that noncollinearity of annihilation photons in our study is mainly contributed by p-Ps. In our experiment, the true and random counts measured for the four phantoms (Fig. 3a–d) increased with increasing [Fe] concentration. This suggests the increase in true and random counts (listed in Table 1) may be attributed to the interaction of with the crystal structure of SPION cores resulting in annihilation via formation of o-Ps (in the triplet state, 3S1) and decay into three gammas. Such triple-coincidences may be processed as a set of double coincidence events or a random event by the PET scanner, thereby incorrectly increasing the true and random counts detected by the PET scanner. Furthermore, the random counts recorded by the scanner for [Fe] = 3 mM is within 0.05% of the counts expected for a 6% increase in count rate relative to the [Fe] = 0 measurement. Furthermore, scintillators currently used in PET scanners, with an energy resolution that is typically worse than 15% at 662 keV and 35% at 340 keV, have low efficiency and sensitivity for detecting three annihilation photons (with a continuum spectrum)31. Nevertheless, triple coincidences may be identified by operating the scanner in LIST mode32. Another study has shown, with modifications in the acquisition electronics of a pre-clinical PET scanner, detection and processing of triple coincidences32. It would be interesting to follow up our study using emerging total body PET scanners, which with their superior sensitivity and 4π geometry are ideal for triple coincidence detection33. The novel Jagiel-lonian PET (J-PET) system9,28,34 has also been designed for detecting three gamma decay from ortho-positronium (o-Ps). Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated a proof of principle of positronium imaging using combined Compton-PET imaging35. Furthermore, although pre-clinical PET-MR scanners would be suitable for future studies, it requires a custom-designed phantom suitable for radiolabeled SPIONs. For the targeted SPION concentrations and magnetization effect in this study, the volume and size of a capillary tube phantom (internal diameter < 1 mm with up to 250 µL36) would not be appropriate, as such a small volume could cause SPION aggregation, clumping and precipitation which can significantly impact measurement accuracy.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of possible interactions of emitted with radiolabeled SPIONs in water. (a) Different routes of positron annihilation: instantaneous annihilation with an electron in the surrounding water, formation of positronium (Ps) in the open volume defects within the SPION core Fe3O4 crystal structure or in surrounding water with two possible quantum states: the singlet state called para-Ps (p-Ps) decaying into two gammas and the triplet state called ortho-Ps (o-Ps) decaying in three gammas. (b,c) Corresponding schematic photon spectra: two back-to-back photons with equal energy of 511 keV for p-Ps decay and three annihilation photons with energies between 0 and 511 keV summing to 1022 keV for o-Ps respectively. Feynman diagrams for both p-Ps and o-Ps decay are illustrated beneath each spectrum.

These results may also have implications for ongoing developments in cancer theranostics, where radiopharmaceuticals are used to both diagnose and treat cancer. Isotopes such as 90Y and 64,67Cu that are already in clinical use for PET imaging and radionuclide therapy (due to their and decays) could be administered by labelling, along with a tumor-targeting agent, onto SPIONs to take advantage of magnetization localization using a PET-MRI scanner. In this context, localization of charged particles by SPION magnetization could help to localize radiation dose within tumor cells, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy of these emerging cancer theranostic strategies37–40.

Overall, these results reveal a unique synergy between nanotechnology and medical imaging technology not previously recognized. In PET-MRI, the magnetic field induces a strong magnetization in SPIONs, which arises from their nanoscale geometric confinement. This nanoscale magnetization localizes the positrons emitted by the PET radiopharmaceutical, thus mitigating the fundamental limit imposed by finite positron range on PET image accuracy in a way that could not be achieved by any other means. As PET-MRI becomes increasingly more mainstream and SPIONs become an attractive alternative to existing MRI contrast agents, we anticipate further development and clinical translation of these synergistic 21st-century technologies.

Methods

SPIONs (Feraheme) were radiolabeled with 89Zr according to the published protocol15,22

Ten phantom vials were prepared with the following dimensions: diameter 17 mm; height 120 mm; and volume 15 mL (see Fig. 2). A series of dilutions of 89Zr-SPION samples were prepared in these 11 separate phantom vials with deionized water. A control phantom vial was made with 89Zr in deionized water only (phantom 1 in Fig. 2). All the phantoms were placed into a tube holder used for simultaneous PET-MRI. Phantom were then scanned using a simultaneous clinical PET-MRI scanner (3 T Biograph mMR). A head PET-MRI coil was used for both the PET and MRI scans. The PET scan was acquired over a period of 10 min. For each scan, the following settings were applied: scanner quantification factor = 88.9 M, branching factor = 0.228, phantom position = Head First-Supine, coincidence window width = 5.86 ns and an energy window with lower and higher levels of 410 and 610 keV respectively. Attenuation and scatter corrections were applied to all the images, which were reconstructed from the PET data using an iterative reconstruction algorithm (Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization (OSEM) with 3 and 21 iterations and subsets respectively). Multi-slice T2W, T1W and T2*W images were acquired using a turbo spin echo (TSE) sequence. Multiple acquisitions of the T1W (at TE = 11 ms with TR = 350 ms) and T2W (at TE = 90 ms with TR = 3000 ms) and T2*W (at TE = 9 ms with TR = 350 ms) scans were acquired. The mean magnitudes of PET image signal intensities were obtained within drawn circular regions of interest (ROIs) using MATLAB software for each sample to calculate the PAL for each phantom according to Eq. (1):

| 1 |

where SER is the signal enhancement ratio (i.e. PET signal intensity image with SPIONs/PET signal intensity image without SPIONs) within the ROI. To assess the spatial resolution of the PET images, the FWHM was calculated from the line spread function (LSF) based on the edge smearing function (ESF) using Eqs. (2) and (3)10:

| 2 |

| 3 |

The ESF was calculated from line profiles of the PET images, where X, xi, and n are the input array of voxel intensity data, the ith element of X and the number of voxels used in averaging, respectively.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Sydney Vital Translation Cancer Research Centre, the Kolling Institute of Medical Research, the University of Sydney and the USA National Institute of Health (NIH): P41EB022544.

Author contributions

Y.G. designed the experiment, developed the method and obtained the results. Y.G. and H.Y. performed the experiments. Y.G. and Z.K. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors were participants in the discussion and interpretation of results, determination of the conclusions and revision of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yaser H. Gholami, Email: yaser.gholami@sydney.edu.au

Zdenka Kuncic, Email: zdenka.kuncic@sydney.edu.au.

References

- 1.Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestor PJ, Scheltens P, Hodges JR. Advances in the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2004;10:S34–S41. doi: 10.1038/nrn1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin CS, Hoffman EJ. Calculation of positron range and its effect on the fundamental limit of positron emission tomography system spatial resolution. Phys. Med. Biol. 1999;44:781–799. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/3/019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laforest R, Liu X. Image quality with non-standard nuclides in PET. Q. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;52:151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jødal L, Le Loirec C, Champion C. Positron range in PET imaging: non-conventional isotopes. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014;59:7419–7434. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/23/7419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conti M, Bendriem B. The new opportunities for high time resolution clinical TOF PET. Clin. Transl. Imaging. 2019;7:139–147. doi: 10.1007/s40336-019-00316-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson RE, et al. Positron kinetics in an idealized PET environment. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moses WW. Fundamental limits of spatial resolution in PET. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2011;648(Supplement 1):S236–S240. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2010.11.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moskal P, Jasińska B, Stępień EŁ, Bass SD. Positronium in medicine and biology. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019;1:527–529. doi: 10.1038/s42254-019-0078-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gholami YH, et al. A radio-nano-platform for T1/T2 dual-mode PET-MR imaging. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:1253–1266. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S241971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez JM, Josephson L, O’Loughlin T, Högemann D, Weissleder R. Magnetic relaxation switches capable of sensing molecular interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:816–820. doi: 10.1038/nbt720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min C, et al. Mechanism of magnetic relaxation switching sensing. ACS Nano. 2012;6:6821–6828. doi: 10.1021/nn301615b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conde J, et al. Revisiting 30 years of biofunctionalization and surface chemistry of inorganic nanoparticles for nanomedicine. Front. Chem. 2014;2:48. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutiérrez L, et al. Aggregation effects on the magnetic properties of iron oxide colloids. Nanotechnology. 2019;30:112001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aafbff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gholami YH, et al. A chelate-free nano-platform for incorporation of diagnostic and therapeutic isotopes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:31–47. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S227931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grillo V, et al. Observation of nanoscale magnetic fields using twisted electron beams. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41467-016-0009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngamchuea K, Tschulik K, Compton RG. Magnetic control: Switchable ultrahigh magnetic gradients at Fe3O4 nanoparticles to enhance solution-phase mass transport. Nano Res. 2015;8:3293–3306. doi: 10.1007/s12274-015-0830-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams PS, Carpino F, Zborowski M. Characterization of magnetic nanoparticles using programmed quadrupole magnetic field-flow fractionation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010;368:4419–4437. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolb A, et al. Shine-through in PET/MR imaging: effects of the magnetic field on positron range and subsequent image artifacts. J. Nucl. Med. 2015;56:951–954. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.147637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, S., Savic, D., Yang, J., Shrestha, U. & Seo, Y. The effect of magnetic field on positron range and spatial resolution in an integrated whole-body time-of-flight PET/MRI system. In 2014 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC) (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Turkbey B, et al. A phase I dosing study of ferumoxytol for MR lymphography at 3 T in patients with prostate cancer. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015;205:64–69. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan H, et al. Heat-induced radiolabeling and fluorescence labeling of Feraheme nanoparticles for PET/SPECT imaging and flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:392–412. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Čížek J. Characterization of lattice defects in metallic materials by positron annihilation spectroscopy: a review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018;34:577–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2017.11.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cal-González J, et al. Simulation of triple coincidences in PET. Phys. Med. Biol. 2015;60:117–136. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/1/117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harpen MD. Positronium: review of symmetry, conserved quantities and decay for the radiological physicist. Med. Phys. 2004;31:57–61. doi: 10.1118/1.1630494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abuelhia E, Kacperski K, Spyrou NM. Three-photon annihilation in PET: 2D imaging experiments. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2007;271:489–495. doi: 10.1007/s10967-007-0235-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Champion C, Le Loirec C. Positron follow-up in liquid water: I. A new Monte Carlo track-structure code. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006;51:1707–1723. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/7/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamińska D, et al. A feasibility study of ortho-positronium decays measurement with the J-PET scanner based on plastic scintillators. Eur. Phys. J. C. 2016;76:445. doi: 10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-4294-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajesh P, Sellaiyan S, Uedono A, Arun T, Joseyphus RJ. Positron annihilation studies on chemically synthesized FeCo alloy. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:9764. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27949-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castellaz P, Siegle A, Stoll H. Positron age-momentum-correlation (AMOC) measurements on organic liquids. J. Nucl. Radiochem. Sci. 2002;3:R1–R7. doi: 10.14494/jnrs2000.3.2_R1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kacperski K, Spyrou NM. Performance of three-photon PET imaging: Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005;50:5679–5695. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/23/019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lage E, et al. Recovery and normalization of triple coincidences in PET. Med. Phys. 2015;42:1398–1410. doi: 10.1118/1.4908226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cherry SR, et al. Total-body PET: maximizing sensitivity to create new opportunities for clinical research and patient care. J. Nucl. Med. 2018;59:3–12. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.184028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moskal P, et al. Performance assessment of the 2 γpositronium imaging with the total-body PET scanners. EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7:44. doi: 10.1186/s40658-020-00307-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida E, et al. Whole gamma imaging: a new concept of PET combined with Compton imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2020;65:125013. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab8e89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferretti A, et al. Phantom study of the impact of reconstruction parameters on the detection of mini- and micro-volume lesions with a low-dose PET/CT acquisition protocol. Eur. J. Radiol. 2012;81:3363–3370. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Jong M, et al. Inhomogeneous localization of radioactivity in the human kidney after injection of [111In-DTPA]octreotide. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:1168–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vegt E, et al. Renal toxicity of radiolabeled peptides and antibody fragments: mechanisms, impact on radionuclide therapy, and strategies for prevention. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51:1049–1058. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.075101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meredith R. Clinical trial design and scoring of radionuclide therapy endpoints: normal organ toxicity and tumor response. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2002;17:83–99. doi: 10.1089/10849780252824109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ. Radiobiologic principles in radionuclide therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2005;46(Suppl 1):4S–12S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.