Abstract

Objective

Bile acid (BA) diarrhea is the cause in ~26% of chronic unexplained (non-bloody) diarrhea (CUD) based on 75SeHCAT testing.

Aim

To assess fecal BA excretion and healthcare utilization in patients with CUD.

Methods

In a retrospective review of 1,071 consecutive patients with CUD who completed 48h fecal BA testing, we analyzed symptoms, diagnostic tests performed, and final diagnoses.

Results

After 135 patients were excluded due to mucosal diseases, increased BA excretion was identified in 476 (51%) of the 936 patients with CUD: 29% with selective increase in primary BA, and 22% with increased total BA excretion (35% with normal primary BA excretion). There were no differences in demographics, clinical symptoms, or history of cholecystectomy in patients with elevated total or selective primary fecal BA excretion compared to patients with normal excretion. Before 48h fecal BA excretion test was performed, patients completed on average 1.2 transaxial imaging 2.6 endoscopic procedures, and 1.6 miscellaneous tests/person. Less than 10% of these tests identified the etiology of CUD. Total fecal BAs >3,033µmol/48h or primary BAs >25% had a 93% negative predictive value to exclude mucosal disease. Among patients with increased fecal BA excretion, >70% reported diarrhea improved with BA sequestrant compared to 26% with normal fecal BA excretion. Patients with selective elevation in primary fecal BAs were 3.1 times (95% CI, 1.5–6.63) more likely to respond to BA sequestrant therapy compared to those with elevated total fecal BAs.

Conclusions

Increased fecal BA excretion is frequent (51%) in patients with CUD. Early 48h fecal BA evaluation has potential to decrease healthcare utilization in CUD.

Keywords: primary, total, 75SeHCAT test, 7alphaC4, FGF19, functional, IBS

INTRODUCTION

Functional gastrointestinal disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), constitute a significant source of healthcare utilization; based on data for 2015 in the United States, $1.765 billion were spent on noninfectious gastroenteritis, including 15.3% for office-based visits and 17.1% for medications (1). The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is estimated at 15% in most industrialized countries, and one-third is associated with IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) or chronic unexplained diarrhea. Diagnostic evaluation contributes to the significant economic burden. In a recent evaluation of the rising healthcare costs, unnecessary diagnostic testing was one of the top four factors associated with excessive cost costing approximately $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion annually (2). When patients present with chronic diarrhea, the diagnostic algorithm (3,4) includes screening blood and fecal tests including markers of inflammation or infection, and second line testing with imaging, endoscopy, and mucosal biopsies to exclude conditions such as celiac disease (population prevalence ~0.8%), inflammatory bowel disease (usually associated with blood in the stool and constitutional symptoms), and colorectal cancer.

Bile acid diarrhea is a condition where excess bile acids enter the colon resulting in increased colonic secretion and motility (5). There are increased synthesis and fecal excretion of bile acids in some patients with IBS-D (6). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have estimated that bile acid diarrhea affects up to 25–30% of patients with chronic, non-bloody diarrhea (7).

In clinical practice, the most common causes of bile acid diarrhea are idiopathic and prior cholecystectomy. With formal diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea (typically with 75SeHCAT retention test), response to cholestyramine occurred in 70–96% of patients with bile acid diarrhea with different degrees of bile acid loss (8). A positive 75SeHCAT retention test in patients with chronic diarrhea resulted in fewer subsequent investigations over the next five years, particularly CT or MRI scans and outpatient visits (9), and provides an opportunity to provide a cost-effective diagnostic evaluation for patients who present with IBS-D or chronic unexplained diarrhea.

Until recently, there were no diagnostic tests for bile acid diarrhea in the United States, since the 75SeHCAT retention test is not approved. Therefore, most clinicians have resorted to therapeutic trials with bile acid sequestrants (10,11) after excluding other diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal neoplasia with abdominal imaging (computerized tomography and/or magnetic resonance scanning including enterography) and colonoscopy with multiple colonic biopsies. Fasting serum 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one or 7αC4 (12) and 48h fecal BA excretion tests have been validated and introduced as diagnostic tests for bile acid diarrhea (13). Although the fasting serum 7αC4 has considerable appeal because of the ease of sample collection, the performance characteristics are significantly inferior compared to those of the fecal bile acid measurements (14–16). The 48h fecal bile acid excretion test has the advantage of measuring total and individual fecal bile acids, which include primary [chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) and cholic acid (CA)] and secondary bile acids [lithocholic acid (LCA) and deoxycholic acid (DCA)].

Our aim was to assess the prevalence of increased total or selective primary fecal bile acid excretion in patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea, identify symptoms that are associated with higher likelihood of diarrhea associated with increased total or selective primary fecal bile acid excretion, assess the potential reduction in healthcare utilization in patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea in clinical practice and levels of bile acid excretion that may be associated with mucosal disease and, therefore, require further diagnostic tests.

METHODS

Study Design

This medical records study was approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB #17–009774). All patients included in this study provided written consent to use their medical records for research purposes. All patients were evaluated between January 1, 2015 and December 17, 2018.

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patients and Medical Records

The study consisted of a sequential cohort of 1,071 patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea, characterized by non-bloody stools and no weight loss. The clinician documented the presence of diarrhea based on the stool frequency and consistency. Patients with IBS-D and those with persistent symptoms in the presence of quiescent celiac or inflammatory bowel disease or steroid-unresponsive microscopic colitis were included. Quiescent celiac disease was defined as complete small bowel healing (no villous atrophy). Quiescent inflammatory bowel disease was based on absence of active inflammation on serum, stool, and endoscopic evaluation. Every patient had completed a clinically conducted 48h fecal bile acid excretion test during a 4-day, 100-g, fat diet. All patients underwent clinical investigations based on the individual provider’s judgement.

Data were collected via the Advanced Cohort Explorer (ACE) application available at Mayo Clinic. ACE is a clinical data repository maintained by the Unified Data Platform. Data collected included demographics (age, gender, BMI), all documented symptoms of diarrhea [frequency, consistency based on Bristol Stool Form Scale (17), nocturnal bowel movements], prior surgeries (particularly cholecystectomy), diagnostic testing and results, and final diagnosis (diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion or other). We also recorded whether patients received treatment with bile acid sequestrants and the outcomes. Treatment response was patient reported improvement in diarrhea. Follow up varied per person and ranged from 2 months to 2 years.

Diagnostic testing included serum, endoscopic procedures (including mucosal biopsies), transaxial imaging, and fecal studies and were completed at the discretion of the clinician evaluating the patient. We subdivided all tests into transaxial imaging, endoscopic procedures, and miscellaneous tests. Miscellaneous testing included serum and fecal studies and breath tests. We considered the diagnostic test as positive if an etiology of chronic unexplained diarrhea was identified. Mucosal disease was defined as conditions that would require additional treatment for disease with definitive biological mechanism or etiology, such as celiac disease, small bowel villous atrophy, malignancy, carcinoid, and inflammatory bowel disease. We evaluated patients with steroid-unresponsive microscopic colitis, diagnosed by pathologist based on colonic mucosal biopsies, in a separate subgroup, but they were included in the main chronic unexplained diarrhea cohort. The rationale for including these patients with steroid-unresponsive microscopic colitis is that up to 43% of patients with microscopic colitis had evidence of bile acid diarrhea, and 86% of those patients responded to cholestyramine (18).

Identification of Diarrhea with Increased Fecal Bile Acid Excretion

Patients completed a 4-day, 100-gram fat diet with 48h stool collection to measure primary and total fecal bile acids as part of their clinical evaluation. Measurements were performed using an established chromatographic method; the extraction, chromatographic (LC/MS-MS) analysis, calculations, and analytical performance of the fecal bile acid assay are detailed elsewhere (5). Diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion was diagnosed based on three previously validated criteria: >10% primary bile acids (without elevated total fecal bile acids); >4% primary bile acids + >1,000µmol/48h; or total fecal bile acids >2,337µmol/48h (15).

Diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion was subdivided into elevated total fecal bile acids (total fecal bile acids >2,337µmol/48h) or elevated primary fecal bile acids (>10% primary bile acids or >4% primary bile acids + >1,000µmol/48h). Diagnosis was not determined based on response to bile acid sequestrant.

Fecal fat measurement was performed on the same collected specimens using the van de Kamer test (19). Fecal bile acid and fecal fat measurements are cost-effective and accurate biomarkers of bowel dysfunction among patients with IBS-D, including significant prediction of increased stool weight, frequency and consistency with AUC >0.71 (sensitivity >55%, specificity >74%) (16).

Data and Statistical Analysis

Data were collected by multiple reviewers of the medical records. Reviewers were not blinded to the administration of bile acid sequestrants. Two separate reviewers assessed the charts, and any conflict was reviewed by an expert senior reviewer who was blinded. We used the Student t test to compare differences between patients with diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion and those with normal fecal bile acid excretion, as well as ANOVA to compare differences in patients with normal fecal bile acid excretion, elevated total fecal bile acids, and elevated primary fecal bile acids. We utilized univariate logistic regression and ROC curves to determine ‘upper bounds’ of total and primary fecal bile acids to help differentiate chronic unexplained diarrhea from patients who had underlying mucosal disease causing diarrhea. We utilized this cut-off to determine the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with true mucosal disease. We conducted multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of response to bile acid sequestrant therapy. For the multivariate logistic regression to determine factors associated with response to bile acid sequestrant therapy, we utilized all clinical parameters collected in addition to patient category of bile acid diarrhea, and total and primary fecal BA levels.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics, Stool Collection and Fecal Bile Acid Excretion

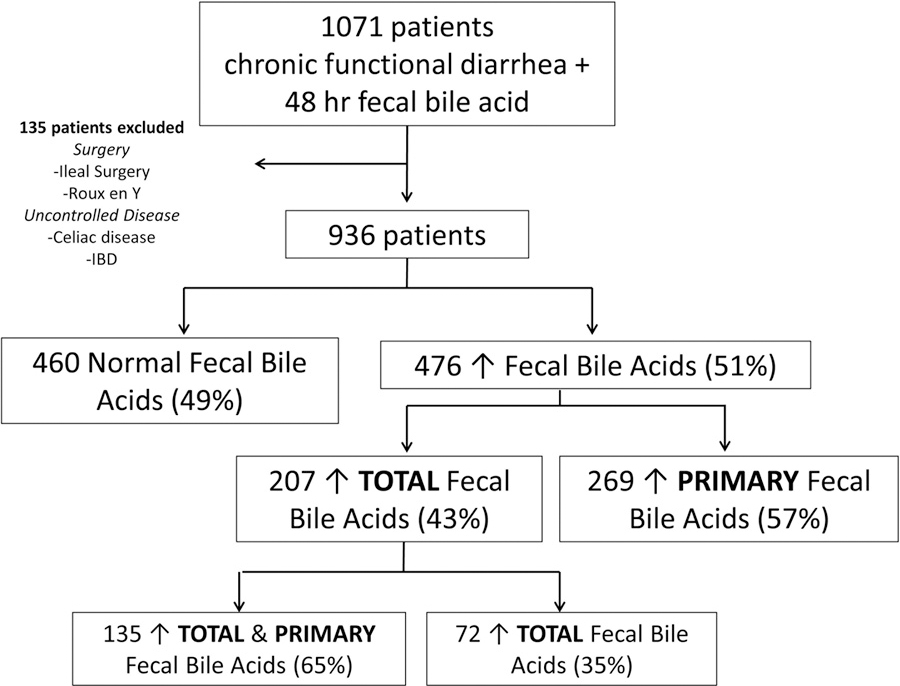

From the entire cohort of 1,071 patients, 62% (661/1071) were considered local or resided within Mayo Clinic’s catchment area. The remaining 38% (410/1071) were from the tertiary referral contingency of patients seen at Mayo Clinic fulfilling eligibility criteria. Figure 1 and Table 1 show patients in the study cohort; 135 patients were excluded because of prior surgery (ileal resection or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) or uncontrolled mucosal disease (specifically, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel diseases, or malignancy). Among the remaining 936 patients, 476 (51%) had elevated fecal bile acids/48h: 207 (22% of total cohort) had elevated total fecal bile acid excretion and 269 (29% of total cohort) had elevated primary fecal bile acid excretion. Among patients with elevated total fecal bile acid, 65% (135/207) also had elevated primary fecal bile acid excretion. There were no differences in demographics, clinical characteristics, fecal weight, fecal fat, or total fecal bile acid excretion between patients with combination of elevated total fecal bile acid and elevated primary fecal bile acid and patients with elevated total fecal bile acid but normal primary fecal bile acid excretion (Table 1). Therefore, we will not separate these groups throughout the remaining Results and Discussion sections, unless directly specified.

Figure 1.

Participants

Table 1.

Demographics, bowel functions, and fecal measurements (median, IQR) in patients with chronic functional diarrhea.

| Parameter | Overall cohort CUD | CUD normal BA excretion | Chronic Unexplained Diarrhea (CUD) high BA excretion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High total BA excretion >2337µmol/48h (Normal Primary BA) | High total BA excretion >1000 µmol/48h with ↑ Primary BA >4% | High primary BA excretion >10% | |||

| Demographics and Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| N | 936 | 460 | 72 | 135 | 269 |

| Age (years) | 52 (36–65) | 52.5 (36.3–66) | 59.5 (49 – 69.5) | 52 (37–65) | 47 (33–62) |

| Gender (M/F) | 299/637 | 149/311 | 26/46 | 49/86 | 75/194 |

| BMI | 26 (21.6–31.3) | 25 (21– 30) | 26.4 (22.6 – 32.3) | 28.2 (23 – 35) | 26 (22–32) |

| Cholecystectomy | 29% (273/1071) | 25% (115/460) | 36% (26/72) | 37% (50/135) | 30% (81/269) |

| BM/day | 5 (3.5–7.5) | 5 (3–6.5) | 5 (3.9 – 7.5) | 5.5 (3.5 – 7.8) | 5 (4–8.8) |

| Avg. daily BSFS | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5.5 – 6.5) | 6 (5.5–6.5) | 6 (5.5–7) |

| Nocturnal BM | 19% (202/1071) | 19% (87/460) | 18% (13/72) | 21% (29/135) | 27% (73/269) |

| Stool Studies | |||||

| 48h fecal weight, g | 393 (247–604) | 301 (182–444) | 631 (456 – 860) | 625 (454 – 855) | 406 (269–630)* |

| 24h fecal fat g/day | 6 (4–10) | 5 (4 – 8.3) | 11 (6.5 – 18) | 8 (5 – 13) | 5 (3–9)* |

| 48h total BA, µmol | 1015 (521– 2123) | 591 (330–965) | 3218 (2661–4046) | 3723 (2861–5030) | 1262 (715– 1778)* |

| 48h primary BA % | 4.5 (1.1–30.2) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 2.7 (0.9–4.7)** | 49.4 (24.8 – 83.1) | 34.5 (15–69.1) |

BA=bile acids; the BA measurements refer to high total BA excretion and high excretion of primary BAs (cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid; either >10% primary BA, or >1000µmol/48h plus >4% primary BAs); BM=bowel movements; BSFS=Bristol Stool Form Scale; CUD=chronic unexplained diarrhea

There was no clinically significant difference in demographics and clinical characteristics among the three groups with elevated BA excretion: elevated both total and primary, or elevated total, or elevated primary BA.

The group with elevated primary BA alone had lower fecal weight and fat vs. elevated total BA group.

p <0.05 when comparing selective elevated primary BA excretion to both groups with high total BA excretion

p <0.05 when comparing high total BA excretion with normal primary BA compared to selective primary BA excretion and high total BA excretion with elevated primary BA excretion

The collection of 48 hour stool samples was successful. Based on the 5th %ile of fecal weight in healthy volunteers (16), <2% of patients within this cohort was found to have a poor or inadequate stool collection. Patients within this cohort were able to follow the stool collection.

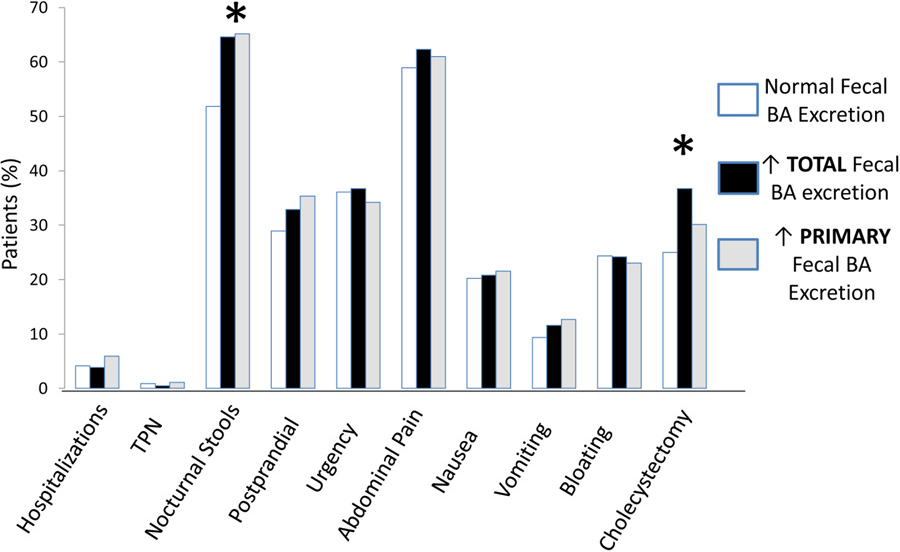

There were no differences in BMI or sex or other clinical characteristics such as bowel movement frequency, consistency or record of nocturnal bowel movements between the groups with normal fecal bile acids, elevated total fecal bile acids, or selective increased primary fecal bile acids (Table 1, Figure 2). Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) rating was available in 69% (643/936) of the cohort. A minority (~13%) of the patients with normal fecal bile acids appeared to have more solid consistency bowel movements (BSFS ≤4); these patients were included in the diarrhea cohort based on the frequency of stool. However, the proportion of patients with documented nocturnal stools was higher in those with elevated fecal bile acids (total or selective primary) and there was a higher proportion of cholecystectomy in those with elevated total fecal bile acid excretion. Prior cholecystectomy was associated with normal fecal bile acid excretion in 115 patients and elevated excretion of total or selective primary fecal bile acids in 157 patients.

Figure 2.

Symptoms and rates of cholecystectomy in patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea, subdivided by those with normal, elevated total, and elevated primary fecal bile acids. There were no clinically significant differences in proportions of diverse symptoms between all groups other than documented nocturnal stools in those with elevated fecal bile acids (total or only primary) and higher proportion of cholecystectomy in those with elevated total fecal bile acid excretion.

Patients with high total or high selective primary fecal bile acid excretion had higher stool weight than patients with normal fecal bile acid excretion (Table 1). In addition, patients with high total fecal bile acid excretion (but not those with selectively higher primary fecal bile acids) had higher stool fat excretion (Table 1). There were no clinically significant differences in demographics, clinical characteristics or stool studies other than the grouping by bile acid excretion, and a statistically significant lower fecal weight and fecal fat in the selective primary fecal bile acid group compared to the elevated total fecal bile acid group.

Supplemental Figure 1 shows prevalence based on 48h fecal bile acid excretion, and the 22% identified with elevated total fecal bile acid excretion is similar to the reported proportion in previous studies utilizing 75SeHCAT (8).

Specialized Gastroenterological Tests Conducted for Diagnosis of Cause of Chronic Diarrhea

In total, the 936 patients had undergone 2,439 endoscopies (2.6/person, 45% colonoscopies), 1,113 cross-sectional imaging (1.2/person), 1,528 miscellaneous tests including 683 stool microbiology tests (Supplemental Figure 2), and 20 exploratory laparotomies (performed elsewhere) before bile acid testing was performed. Even after excluding patients who needed to undergo routine monitoring of disease activity with endoscopy (celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease), the average number of endoscopic procedures did not change (average 2.6/person). Diagnostic evaluation was similar in patient groups with diarrhea associated with increased or normal fecal bile acid excretion, demonstrating no difference in how the chronic diarrhea in these patients was investigated. The diagnostic yields of specific diagnoses associated with these tests were ~4% for cross-sectional imaging (3.6% inflammation within the colon or small intestine), ~5% for endoscopies (2.0% lymphocytic colitis, 1.4% collagenous colitis, 1.2% chronic colitis/ileitis), and 8.3% for the miscellaneous tests (1.6% stool infection, 5.6% small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, 1.1% fructose or lactose malabsorption) (Figure 3). Thus, the additional investigations identified the cause of chronic unexplained diarrhea in less than 10% of patients.

Figure 3.

For each group of tests, <10% identified etiology of non-bloody, chronic unexplained diarrhea.

Timing of Specialized Gastroenterological Tests Conducted for Diagnosis of Cause of Chronic Diarrhea

We evaluated the timing of diagnostic testing completed for chronic unexplained diarrhea relative to the time of referral to Mayo Clinic. Pre-referral testing (done at outside institutions) included 822 cross-sectional imaging and 1630 endoscopic evaluations; testing at Mayo Clinic included 386 cross-sectional images and 771 endoscopic procedures that were <50% compared to numbers at outside institutions. In addition, only 61/386 (15.8%) imaging studies and 401/771 (52%) endoscopic procedures conducted at Mayo Clinic were duplicate studies, with the majority being colonoscopy and upper endoscopies.

Based on evaluation of the pre-referral testing, each patient had completed on average 1 cross-sectional imaging study and 1.7 endoscopic studies, with low diagnostic yield (<10%).

Differentiation of Patients with Mucosal Diseases Compared to Chronic Unexplained Diarrhea Based on Bile Acid Testing

Table 2, upper panel, summarizes the differences in bowel functions and fecal measurements in patients with mucosal diseases compared to chronic unexplained diarrhea in this cohort of patients. Based on the ‘upper bound’ cut-offs based on the ROC curves from univariate logistic regression, we found that patients with total fecal bile acids <3033 µmol/48h or primary bile acids <25% had a 93% negative predictive value to rule out mucosal disease (Table 2, lower panel).

Table 2.

Upper panel: Differentiation of bowel function and fecal measurements in patients with mucosal diseases compared to functional diarrhea. Data shown are median (IQR). Microscopic colitis was included within the functional diarrhea cohort if patients were steroid-unresponsive. Lower panel: Primary bile acids ≤25% and total fecal bile acids ≤3033 µmol/48h has a 93% negative predictive value for ruling out mucosal disease. Patients with primary bile acids >25% and total fecal bile acids >3033 µmol/48h would require additional mucosal evaluation.

| Parameter | Mucosal disease causing diarrhea | Functional diarrhea | P value, |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 135 | 936 | |

| # BM/day | 6.5 (5–10) | 5 (3.5–7.5) | <0.001 |

| BSFS (7 point scale) | 6 (5.9–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.02 |

| Fecal weight (g/48h) | 776 (455–1263) | 391 (247–601) | <0.001 |

| Fecal Fat (g/24h) | 14 (6–36) | 6 (4–10) | <0.001 |

| Primary BA (%) | 43.5 (7.6–97.9) | 4.5 (1.1–30.2) | <0.001 |

| Total Fecal BA (µmol/48h) | 3,067 ( 1126–7339) | 1,015.5 (522–2130) | <0.001 |

| Mucosal Disease | No Mucosal Disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total fecal BA >3033 µmol /48h | 73 | 131 | PPV = 36% (73/204) |

| Total fecal BA ≤3033 µmol/48h | 62 | 805 | NPV = 93% (805/867) |

| Sensitivity = 54% (73/135) | Specificity= 86% (805/936) | ||

| Mucosal Disease | No Mucosal Disease | ||

| Primary BA > 25% | 89 | 243 | PPV = 36% (89/243) |

| Primary BA ≤ 25% | 46 | 693 | NPV = 94% (693/739) |

| Sensitivity = 66% (89/135) | Specificity= 74% (693/936) |

Bold numbers=IQR; BM=bowel movements; BA=bile acids; BSFS=Bristol Stool Form Scale

BA=bile acids; PPV=positive predictive value; NPV=negative predictive value

Outcomes of Treatment with Bile Acid Sequestrants

Follow-up data were available in 47% of the 476 patients with diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion who received bile acid sequestrants. Improvement in the diarrhea was documented with bile acid sequestrant treatment: 75% (56/76) with cholestyramine, 71% (67/95) with colesevelam, and 67% (14/21) with colestipol (Figure 4). Some of these patients who did not respond to cholestyramine were switched to a second bile acid sequestrant: 87% (7/8) of patients transitioned to colesevelam and 50% (2/4) transitioned to colestipol had an improvement in diarrhea. Rates of cholecystectomy were the same in patients who responded to bile acid sequestrant (34%) and those who did not respond (29%). Cholecystectomy did not predict response to bile acid sequestrant therapy (p=0.71).

Figure 4.

Response to bile acid sequestrants in patients diagnosed with bile acid diarrhea; patients with diagnosis based on only elevated primary bile acids are designated as the “selective”primary bile acid group.

In the 60 patients who discontinued the bile acid sequestrant therapy, 43 provided reasons for discontinuation which included constipation (28%), nausea (26%), bloating (12%), abdominal pain (7%), and vomiting (5%). Nausea was reported predominantly in cholestyramine users. Bloating and constipation were associated equally in those taking cholestyramine and colesevelam.

Sixty-one patients with chronic diarrhea with normal fecal bile acid excretion received bile acid sequestrants as a therapeutic trial. Follow-up data were available for 62% of patients (38/61). The proportion of responders was 37%: 26% (6/23) cholestyramine, 50% (5/10) colesevelam, 60% (3/5) colestipol (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Response to bile acid sequestrants in patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea with normal fecal bile acid excretion.

Predictors of Responsiveness to Bile Acid Sequestrants in Diarrhea Associated with Increased Fecal Bile Acid Excretion

Multivariable logistic regression predicted that patients with isolated increase in primary fecal bile acids had three times higher odds [OR 3.1 (95% CI 1.5–6.63)] of responding to bile acid sequestrants compared to those with increased total fecal bile acids.

Within the group with increased total fecal BA excretion, those with increased compared to normal primary BA excretion showed no statistically significant difference in the response to bile acid sequestrant therapy [OR 2.5 (95% CI 0.83–7.6)].

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that measurement of 48h fecal bile acid excretion while the patient receives 100 grams of dietary fat/day leads to the diagnosis of diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion in clinical gastroenterology practice. After the recommended serum and stool studies for the evaluation of chronic unexplained diarrhea, we believe these data support that the 48h fecal bile acid measurement adopted earlier in clinical practice has the potential to reduce healthcare utilization and costs in patients with chronic non-bloody, unexplained diarrhea.

Our study reports a consecutive series of 1,000 patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea at a single referral center; the chronic diarrhea subgroups with increased or normal fecal bile acid excretion had similar predisposing factors for diarrhea, such as proportions with prior cholecystectomies (approximately 33% in all groups), and clinical symptoms. The balance in proportion with prior cholecystectomy is reassuring, even though the literature shows that the prevalence of bile acid diarrhea in patients with prior cholecystectomy is only about 10%. Thus, a systematic review of 25 studies that included 3388 patients post-cholecystectomy determined that only 9.1% of patients developed diarrhea, and 6% of the total cohort had bile acid diarrhea (20). In 125 consecutive post-cholecystectomy patients, 25.2% developed diarrhea at 1 week and only 5.7% at 3 months after surgery (21). More importantly, cholecystectomy did not predict response to bile acid sequestrant therapy.

Therefore, these data suggest that all patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea may benefit from 48h fecal bile acid testing. Correct identification of patients with bile acid diarrhea will be important with the availability of bile acid diarrhea targeted therapy with bile acid sequestrants or, in the future, farnesoid X receptor agonists such as obeticholic acid (22,23) or tropifexor (24). These approaches would be indicated instead or in addition to symptomatic treatment with an anti-diarrheal medication.

What Is the Optimal Method for Positive Diagnosis of Bile Acid Diarrhea?

Among the diagnostic tests for bile acid diarrhea, most of the prior literature involved the 75SeHCAT retention test. In a systematic analysis of studies of patients in secondary and tertiary care centers, 75SeHCAT test identified bile acid diarrhea in 26% of patients with unexplained chronic diarrhea (8). However, this test is not available in the United States, and the two alternative diagnostic approaches currently available through reference laboratories are serum 7αC4 and 48h fecal excretion of total and individual bile acids. Our study demonstrated that 51% of patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea in a secondary/tertiary referral cohort had diarrhea associated with increased fecal bile acid excretion. We acknowledge that this estimate needs to be assessed prospectively in a primary care setting to truly determine the prevalence of bile acid diarrhea. However, the known prevalence of bile acid diarrhea based on 75SeHCAT has also been determined in patients who were referred to secondary and tertiary care centers for chronic unexplained diarrhea (8).

Since our study did not prospectively appraise the response to bile acid sequestrants in every patient with increased fecal bile acid excretion, we have been conservative in our interpretation. Thus, we have not assumed the diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea in this patient cohort, even though the proportion of responders (based on documentation in the medical records) among those with increased fecal bile acid excretion (75%) approximates the 70–96% of the responders to cholestyramine in patients with bile acid diarrhea based on 75SeHCAT, as compared to only a quarter of patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea with normal fecal bile acid excretion responding to bile acid sequestrants.

Excess fecal excretion of primary bile acids may either result from increased amounts synthesized or secreted into the small intestine by the liver, or decreased ileal reabsorption (25), or decreased bile acid dehydroxylation by colonic bacteria during the accelerated transit through the colon as a result of the diarrheal diseases. Further studies need to be conducted to help further characterize these processes in patients with increased fecal excretion of primary bile acids.

It would be ideal if the diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea could be achieved with avoidance of a 48h stool collection, for example, by means of fasting serum 7αC4 and FGF19. Recent validation studies using multivariate analysis showed that total fecal bile acid excretion and excretion of the primary bile acids were significantly associated with increased fecal weight >469g in 48 hours (a marker of significant diarrhea), whereas serum 7αC4 and FGF19 were not significant predictors (16). Moreover, elevated total and primary fecal bile acids (using each of the three parameters to define increased fecal bile acid excretion in this study) were associated with similar accuracy in predicting fecal weight >400g/48h (definition of diarrhea) with AUC values of 0.73 to 0.86. The corresponding AUC values for serum 7αC4 and FGF19, or combined serum 7αC4 and FGF19 were 0.57, 0.52, and 0.57, respectively (15). Thus, at present, 48h total and primary fecal bile acid excretion is the most valid method available to physicians in the United States for diagnosis of chronic unexplained diarrhea with increased fecal bile acid excretion.

When and How Should Organic Mucosal Diseases Be Investigated?

Organic mucosal diseases may be associated with alarm symptoms such as blood in the stool and weight loss. However, despite the extensive use of endoscopy and mucosal biopsies, abdominal transaxial imaging, and fecal microbiological tests, the diagnostic yield is low. Based on the data in Table 2 and Figure 6, fecal primary bile acids >25% or total fecal bile acids >3033µmol/48h have a 93% negative predictive value at excluding mucosal disease, that is, they suggest the need to conduct further screening to exclude organic mucosal diseases, by performing endoscopic or transaxial imaging. This demonstrates that 48h fecal bile acid testing may have utility as a screening method in patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea and can identify patients requiring more diagnostic testing for identification of mucosal disease.

Figure 6.

Proposed algorithm to interpret 48-hour fecal bile acid excretion. We recommend completing serum and stool testing (hemoglobin, electrolyte panel, CRP, ESR, iron, celiac serology, fecal calprotectin and fecal fat) (3).

Consideration of Colonic Cancer and Microscopic Colitis

Screening and surveillance colonoscopies are indicated in accordance with multi-society guidelines, even in patients presenting with chronic unexplained diarrhea. Given that the median age of patients in this cohort was 52 years, it is possible that, in 50% of patients, the clinician evaluating the patient with chronic unexplained diarrhea may have considered the opportunity to conduct colonoscopy for cancer screening as well as excluding colonic diseases. Nevertheless, in the absence of alarm symptoms such as rectal bleeding or a recent change in bowel function, we believe it is perfectly reasonable not to use endoscopy and CT/MR imaging as first line tests in patients presenting with chronic unexplained diarrhea.

Another consideration is exclusion of microscopic colitis. Here, it is important to consider the population prevalence in general and prevalence of microscopic colitis as well as bile acid diarrhea among patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea. Thus, an authoritative review (26) summarized important numerical data regarding microscopic colitis: First, population-based studies in Europe and North America reported the incidence of microscopic colitis between 1 and 25 per 100,000 person-years. Second, microscopic colitis is present in 8–16% of patients undergoing colonoscopy for evaluation of chronic watery diarrhea. On the other hand, it is estimated by Walters and Pattni (27) that the prevalence of bile acid diarrhea is 1%, and 25–33% of patients with symptoms of IBS-D or functional diarrhea in two systematic reviews (7,8) had bile acid diarrhea. Given these facts, exclusion of microscopic colitis (which requires costly colonoscopy with multiple biopsies) may not be mandatory in a cohort in which 75% of patients were <65 years old, since microscopic colitis is more prevalent in those >65 years of age (26). We conclude that selection of patients to undergo colonoscopy should be individualized, based on pre-test probabilities.

How Can Healthcare Utilization and Costs Be Reduced in Patients with Chronic Unexplained Diarrhea?

We propose that more widespread utilization of the fecal bile acid 48h excretion test has the potential to reduce unnecessary imaging with endoscopy and biopsies, CT or MRI, consistent with the recommended need to curb unnecessary and wasted diagnostic imaging (28). Even though chronic diarrhea is not one of the 8 priority areas mandated in imaging appropriate use criteria to be enforced on January 1, 2020 by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (29). In 2014, the indications of “non-infectious gastroenteritis/colitis” and “diarrhea” constituted almost 1.8 million emergency department visits, 120,000 hospital diagnoses, 80,000 readmissions to hospitals within 30 days; in addition there were >17 million endoscopic procedures performed in 2013 (1). This suggests there are opportunities for reducing healthcare costs for these common presentations.

Another approach proposed to reduce costs in the evaluation of IBS-D is a novel IBS diagnostic blood panel; this blood test was predicted to result in $509 cost savings when compared with the standard of care exclusionary diagnostic pathway involving downstream testing (e.g., colonoscopy, computed tomography scans). This serum test costs approximately $500 per the manufacturer (30). A maximum estimated cost for the 48 hour fecal bile acid test is $240. The novel IBS diagnostic blood panel utilized cost minimization decision tree model which included endoscopy within first line evaluation. As such, fecal bile acid testing at half the cost of the IBS panel may have at least similar if not more cost savings. We are pursuing additional modeling analyses to understand the cost saving opportunities with 48 hour fecal bile acid testing, not only as a diagnostic test but as a screening tool to differentiate those who deserve further mucosal evaluation.

Based on the findings in the current study, we propose an algorithm to interpret 48h fecal bile acid excretion and to select patients for additional endoscopic and imaging studies (Figure 6). We recommend the 48 hour fecal bile acid testing after serum and stool samples (hemoglobin, electrolyte panel, CRP, ESR, iron, celiac serology, fecal calprotectin and fecal fat on random stool sample) (3).

Limitations

Our study involved a historical cohort study and the findings need to be confirmed in a prospective study. The single center is a tertiary care center, reflecting a biased patient population. However, 62% of the patient population was found within the catchment area and received regular care. Even within this smaller portion of patients, the results of the study were similar to those reported for the entire cohort.

There was no direct comparison of 48h fecal bile acids to 75SeHCAT retention test. At this time, there are no accurate alternatives for diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea within the United States. The 48h fecal bile acid excretion does require a 4-day, 100-gram fat diet with 48h stool collection. However, although some patients may find 48h fecal collection difficult, it is worth noting that >1,000 patients evaluated at a single center successfully completed this stool testing within a 2-year period. It is also worth noting that the test is accessible everywhere within the U.S. through a reference laboratory, is cost effective, and only requires measurement by HPLC mass spectrometry which is available in most clinical chemistry laboratories.

Lastly, the response to bile acid sequestrants was based on an open-label treatment without rigorous quantitation of continuous variables to define the diarrhea (e.g. number of bowel movements per day or Bristol Stool Form Scale ratings) or categorical variables such as proportion with adequate relief relative to baseline pre-treatment. We plan on pursuing randomized, controlled trials to assess change in diarrhea with bile acid sequestrants in patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea with elevated fecal bile acids and those with normal fecal bile acids.

Conclusion

The fecal bile acid excretion test provides a positive diagnosis of chronic unexplained diarrhea with increased fecal bile acid excretion with the opportunity to select targeted treatment. Increased BA excretion was identified in 476 (51%) of the 936 patients with CUD: 29% with selective increase in primary BA, and 22% with increased total BA excretion. Our data also suggest that implementation of this biochemical measurement has the potential to reduce healthcare utilization and thereby reduce healthcare costs.

Supplementary Material

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

What is known?

75SeHCAT test is accurate for diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea.

75SeHCAT test can reduce subsequent consultations and costs of care for patients with bile acid diarrhea.

What is new here?

In a cohort of patients with chronic unexplained diarrhea, 48h fecal excretion of total and primary bile acids identified ~50% having elevated bile acid excretion.

These patients had undergone an average of 1.2 transaxial imaging/person, 2.6 endoscopic procedures/person, and 1.6 miscellaneous tests/person.

However, those tests provided the definitive diagnosis in less than 10% of patients.

Early 48h fecal bile acid evaluation has the potential to decrease healthcare utilization.

Total fecal bile acids >3033µmol/48h or primary bile acid >25% in the 48h collection are indications to screen for underlying mucosal disease.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the following for assistance with records review: Hiba Saifuddin, Patrick Duggan, Valeria Melo, Taylor Thomas, Megan Heeney, Adrian Beyde, James Miller, Kenneth Valles, Kafayat Oyemade, Joseph Fenner, and Victor Chedid. We also thank Leslie Donato, Ph.D., Department of Laboratory Medicine, Mayo Clinic, for collaboration in developing the assays used in this study, and Mrs. Cindy Stanislav for excellent secretarial assistance.

Financial support: Dr. Michael Camilleri’s research on bile acid diarrhea is supported by RO1-DK115950 grant from National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used:

- 7αC4

7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one

- BA

bile acid

- FGF-19

fibroblast growth factor 19

- CA

cholic acid

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- DCA

deoxycholic acid

- LCA

lithocholic acid

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Michael Camilleri takes full responsibility for the conduct of the study. He had access to the data and control of the decision to publish.

Competing interests: The authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019;156:254–72, e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019. October 7 10.1001/jama.2019.13978. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Camilleri M, Sellin JH, Barrett KE. Invited Review: Pathophysiology, evaluation and management of chronic watery diarrhea. Gastroenterology 2017;152:515–32, e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smalley W, Falck-Ytter C, Carrasco-Labra A, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Laboratory Evaluation of Functional Diarrhea and Diarrhea- Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults (IBS-D). Gastroenterology 2019; 157:851–4, e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin A, Camilleri M, Vijayvargiya P, et al. Bowel functions, fecal unconjugated primary and secondary bile acids, and colonic transit in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1270–5, e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong BS, Camilleri M, Carlson P, et al. Increased bile acid biosynthesis is associated with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1009–15, e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentin N, Camilleri M, Altayar O, et al. Biomarkers for bile acid diarrhea in functional bowel disorder with diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2016;65:1951–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wedlake L, A’Hern R, Russell D, et al. Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:707–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner JM, Pattni SS, Appleby RN, et al. A positive SeHCAT test results in fewer subsequent investigations in patients with chronic diarrhoea. Frontline Gastroenterol 2017;8:279–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beigel F, Teich N, Howaldt S, et al. Colesevelam for the treatment of bile acid malabsorption-associated diarrhea in patients with Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández-Bañares F, Rosinach M, Piqueras M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: colestyramine vs. hydroxypropyl cellulose in patients with functional chronic watery diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:1132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donato LJ, Lueke A, Kenyon SM, et al. Description of analytical method and clinical utility of measuring serum 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (7aC4) by mass spectrometry. Clin Biochem 2018;52:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M. Commentary: Current practice in the diagnosis of bile acid diarrhea. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, Carlson P, et al. Performance characteristics of serum C4 and FGF19 measurements to exclude the diagnosis of bile acid diarrhoea in IBS-diarrhoea and functional diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:581–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, Chedid V, et al. Analysis of fecal primary bile acids detects increased stool weight and colonic transit in patients with chronic functional diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:922–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, Burton D, et al. Bile and fat excretion are biomarkers of clinically significant diarrhoea and constipation in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49:744–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heaton KW, Ghosh S, Braddon FE. How bad are the symptoms and bowel dysfunction of patients with the irritable bowel syndrome? A prospective, controlled study with emphasis on stool form. Gut 1991;32:73–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez-Banares F, Esteve M, Salas A, et al. Bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis and in previously unexplained functional chronic diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci 2001;46:2231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van De Kamer JH, Ten Bokkel Huinink H, Weyers HA. Rapid method for the determination of fat in feces. J Biol Chem 1949;177:347–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farahmandfar MR, Chabok M, Alade M, et al. Post cholecystectomy diarrhoea: a systematic review. Surg Sci 2012;3:7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yueh T-P, Chen F-Y, Lin T-E, et al. Diarrhea after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: associated factors and predictors. Asian J Surg 2014;37:171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegyi P, Maléth J, Walters JR, et al. Guts and gall: bile acids in regulation of intestinal epithelial function in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2018;98:1983–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walters JR, Johnston IM, Nolan JD, et al. The response of patients with bile acid diarrhoea to the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camilleri M, Linker Nord S, Burton D, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover, multiple-dose study of tropifexor, a non bile acid FXR agonist, in patients with primary bile acid diarrhea. Gastroenterology 2019;156(Suppl. 1):S204–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camilleri M Physiological underpinnings of irritable bowel syndrome: neurohormonal mechanisms. J Physiol 2014;592:2967–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pardi DS. Diagnosis and management of microscopic colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters JR, Pattni SS. Managing bile acid diarrhoea. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2010;3:349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oren O, Kebebew E, Ioannidis J. Curbing unnecessary and wasted diagnostic imaging. JAMA 2019;321:245–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hentel KD, Menard A, Mongan J, et al. What physicians and health organizations should know about mandated imaging appropriate use criteria. Ann Intern Med 2019. June 11 10.7326/M19-0287. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Pimentel M, Purdy C, Magar R, et al. A predictive model to estimate cost savings of a novel diagnostic blood panel for diagnosis of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Ther 2016;38:1638–52, e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.