Abstract

Aim:

Interleukin-23 (IL-23) is a cytokine that promotes the differentiation of T cells into pro-inflammatory Th17. We have previously shown that IL-23 is upregulated in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients and lupus prone mice. As SLE is highly heterogeneous, we asked whether IL-23 production correlates with different manifestations of the disease.

Methods:

We recruited 56 subjects who fulfilled the ACR criteria for SLE. Interleukin-23 was measured in the serum by ELISA.

Results:

IL-23 levels were positively correlated with the overall SLE disease activity as measured with the SLEDAI. Moreover, IL-23 correlated with the skin, renal domains of SLEDAI and arthritis but not with cytopenias or serositis. IL-23 did also correlate with anti-dsDNA antibody positivity and inversely correlated with C3 levels. We found no relationship between patients’ demographics, prior disease manifestations, medications, or autoantibody profile and IL-23 levels. No immunomodulatory medication seemed to be affecting IL-23 levels suggesting that current medications used in SLE are not as effective in shutting down the IL-23/IL-17 axis.

Conclusions:

IL-23 levels track SLE disease activity mostly in the renal, skin and musculoskeletal domains. Our data suggest that IL-23 inhibitors may be helpful in combination with current standard of care in alleviating arthritis, renal and cutaneous manifestations of the disease.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, interleukin 23, T helper-17, nephritis

Introduction

Far from being fully understood, the mechanisms that drive inflammation and ultimately damage in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) include both the innate and the adaptive immune systems.1 Much emphasis has been given to the autoantibody producing B cells and the imbalance between regulatory and pro-inflammatory T cells. Our and others’ work though has shown that some of the adaptive immune system aberrancies in SLE are driven by innate immune system derived cytokines.

Interleukin 23 (IL-23) is such a cytokine, produced by monocytes and driving T cell differentiation into proinflammatory Th17 cells.2 We have shown that SLE patients have on average higher IL-23 serum levels and IL-23 receptor (IL23R) expression on T cells than controls3 and that lupus-prone mice depend on the IL-23R for the development of nephritis.4,5 We initially attributed this phenomenon to the effect that IL-23 has on Th17 development, as Th17 were detected in the kidneys of patients with lupus nephritis and were thought to be orchestrating inflammation locally.6 We found though that IL-23 may have a more profound effect on SLE T cell phenotype; it induces extrafollicular T helper cells (eTfh) that drive B cell autoantibody production while limiting IL-2 production and regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation.3 This effect was further demonstrated by the fact that murine lupus lymphocytes treated in vitro with IL-23 can induce mild nephritis in lymphopenic but otherwise normal mice.4

Following successful treatment of lupus-prone mice with an anti-IL23 antibody,7 patients with non-renal SLE were treated with the IL-23p40 blocking antibody Ustekinumab. Patients treated with Ustekinumab were more likely to achieve the pre-specified SLE disease activity response index (SRI) than placebo treated patients (62% vs 33%).8 Of note, as IL-23 and IL-12 share the p40 unit, Ustekinumab’s effect on disease activity cannot be solely ascribed to its effect on IL-23. Following the positive results of this phase II trial, Ustekinumab is currently being evaluated in a phase III trial in patients with non-renal lupus.

As multiple medications are moving towards phase II and III trials in patients with SLE and/or lupus nephritis, it has become apparent that biomarkers are needed to help predict the effectiveness of these medications. This is crucial for SLE as the disease is characterized by profound heterogeneity and has not to date a well-understood etiopathogenesis. To this end, we measured IL-23 levels in the serum of patients with SLE at various stages of the disease with the ultimate goal of identifying the phenotype that is most likely to respond to IL-23 inhibition.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Patients who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the diagnosis of SLE9 were enrolled in the study. The subjects were recruited at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) division of rheumatology outpatient practice. At the day of the index visit each subject’s history of SLE manifestations including renal biopsy results, and immunological profile were collected. In addition, the subject’s current manifestations, and medication doses were determined. Each subject gave blood and urine samples that were used for pertinent laboratory tests including white cell count, lymphocyte count, platelet count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, BUN, creatinine, complement C3 and C4, anti-dsDNA antibody levels, sedimentation rate, urinalysis and urine protein and creatinine levels. At the same time, subjects donated 10 ml of blood for research purposes. Using the above clinical and laboratory measurements, the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) was calculated.10 We also calculated the clinical SLEDAI (cSLEDAI) by using all but the two immunologic components (anti-dsDNA antibodies and complement) of the SLEDAI. The BIDMC institutional review board approved the study protocol and informed consents were obtained from all study subjects.

Serum isolation and IL-23 measurement

All study subjects donated blood that was collected in 10 mL serum separator tubes. The supernatant (serum) was collected after centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 5 minutes. IL-23 was measured using ELISA (R&D systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA®. Statistical significance was determined by non-paired t-test, linear and logistic regression and Pearson correlation test where appropriate.

Results

We enrolled 56 patients with SLE in this study (Table 1). Most of the subjects had mild to moderate disease activity as measured by the SLEDAI with a mean of 6.71 ± 1.02. The demographics, disease activity parameters, key laboratory data and medications of the patient cohort are shown in Table 1. Mean age of our cohort was 36 years. Racial distribution was 42% white, 29% black, 20% Asian while 8% identified as ‘other’. Predominant clinical manifestations were mucocutaneous in 82% of patients followed by arthritis in 64%. Renal involvement was observed in 46% of patients who uniformly had high titer of anti-dsDNA antibodies. More specifically 12.5% had biopsy proven class III nephritis, 18% class IV and 12.5% class V. 3.5% of patients had proteinuria but not biopsy proven nephritis.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients.

| Number of subjects | 56 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean +/− SD | 36.2 +/− 12.1 years |

| Race | |

| Asian | 20% |

| White | 43% |

| Black | 29% |

| Other | 8% |

| SLEDAI, mean +/− SD | 6.7 +/− 1.02 |

| Renal | 46% (26/56) |

| Mucocutaneous | 82% (46/56) |

| Arthritis | 64% (36/56) |

| Hematologic | 11% (6/56) |

| Serositis | 32% (18/56) |

| Cytopenias | 73% (41/56) |

| White Cell Count, mean +/− SD | 5.58 +/− 3.06 × 1,000/μL |

| Lymphocytes, mean +/− SD | 1.19 +/− 0.61 × 1,000/μL |

| Hemoglobin, mean +/− SD | 11.73 +/− 1.69 g/dL |

| Platelets, mean +/− SD | 260.21 +/− 113.92 × 1,000/μL |

| Creatinine, mean +/− SD | 0.89 +/− 0.72 mg/dL |

| C3, mean +/− SD | 90.88 +/− 33.71 mg/dL |

| C4, mean +/− SD | 18.61 +/− 11.14 mg/dL |

| Anti-dsDNA antibody positive | 52% |

| ESR, mean +/− SD | 37.17 +/− 31.59 |

| Urine protein to creatinine, mean +/− SD | 0.88 +/− 2.04 mg/mg |

| Immune-modulatory Medications | Percent subjects treated; Mean Dose +/− SD |

| Hydroxychloroquine (po, daily) | 68 %; 373 ± 60 mg |

| Prednisone (po, daily) | 55 %; 16 ± 18 mg |

| Mycophenolate (po, daily) | 34 %; 1973 ± 564 mg |

| Azathioprine (po, daily) | 11 %; 100 ± 27 mg |

| Tocilizumab (SC, weekly) | 2 %; 162 mg |

| Belimumab (IV) | 4 %; 670 ± 183 mg |

| Tacrolimus (po, daily) | 2 %; 3 mg |

| Methotrexate (weekly) | 4 %; 13 ± 5 mg |

| Cyclophosphamide (IV) | 4 %; 1600 ± 566 mg |

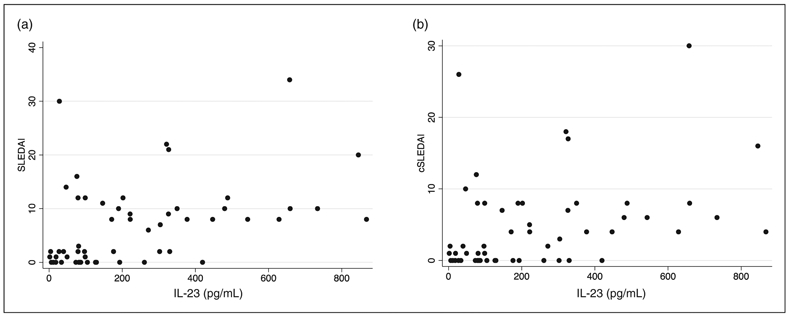

We then measured the IL-23 level in the serum of all patients using a validated ELISA method. We found that IL-23 levels were higher in patients with higher disease activity (r:0.47 p < 0.001) as shown in Figure 1. Moreover, when we calculated the clinical SLEDAI by subtracting the complement and anti-dsDNA antibody components from the SLEDAI, the correlation between IL-23 and disease activity remained strong as shown in Figure 1(b) (r = 0.3752, p < 0.001). We also used regression analysis to adjust for age and race, which did not affect the correlation between IL-23 and SLEDAI (r2: 02634, p < 0.001). Similarly, IL-23 levels did not correlate with hydroxychloroquine, prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil or other DMARD use (data not shown).

Figure 1.

IL-23 positively correlates with SLE disease activity. IL-23 concentration in the serum of patients with SLE is plotted against SLEDAI (a) and clinical SLEDAI (b) as described in the Materials and Methods.

To further understand the role of IL-23 in SLE, we evaluated the levels in patients with various manifestations of SLE. As shown in Table 2, we found that patients with active nephritis, mucocutaneous or musculoskeletal manifestations were more likely to have elevated IL-23 levels (p: 0.029, 0.033 and 0.037 respectively). Contrary to that, hematologic manifestations and active serositis did not correlate with IL-23 (p:0.386, 0.238 and 0.386 respectively). We then asked whether anti-dsDNA antibody positivity or decrease of complement level correlate with IL-23. We found that patients with elevated anti-dsDNA antibody levels had higher IL-23 serum levels (326.1 ± 49.4 pg/ml vs. 152.9 ± 30.3 pg/ml; p = 0.003) (Table 2). Of note we have previously shown that healthy individuals have IL-23 serum levels of 28.6+/−28.8 pg/mL.3 C3, but interestingly not C4 levels, inversely correlated with IL-23 (r = −0.4734, p = 0.0003 for C3 levels; r = −0.4075, p = 0.22 for C4 levels).

Table 2.

Correlation of IL-23 with clinical manifestations and laboratory parameters.

| IL-23 mean ± SE (pg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | p-Value | |

| Renal | 212.32 +/− 48.8 | 261.41 +/− 48.8 | 0.029 |

| Mucocutaneous | 150.60 +/− 41.36 | 251.29+/−35.21 | 0.033 |

| Arthritis | 223.85 +/− 56.04 | 238.56+/−35.72 | 0.037 |

| Hematologic | 237.07+/−32.74 | 194.93+/−56.05 | 0.386 |

| Serositis | 243.49+/−37.68 | 211.81 +/− 50.99 | 0.238 |

| Cytopenias | 190.18+/−59.61 | 249.08+/−35.09 | 0.386 |

| Antibody against | |||

| dsDNA | 152.9 +/− 30.3 | 326.1 +/− 49.4 | 0.003 |

| Sm | 204.6 +/− 36.5 | 266.4 +/− 49.5 | 0.311 |

| RNP | 218.3 +/− 34.1 | 249.4 +/− 51.3 | 0.611 |

| SSA | 179.7 +/− 25.8 | 290.8 +/− 54.6 | 0.065 |

Traditionally, antibodies such as SSA and anti-dsDNA have been used to prognosticate the clinical course of patients with SLE. We therefore asked whether IL-23 levels differ in patients who tested positive for SLE related autoantibodies. As shown in Table 2, we found no specific correlation between IL-23 levels and anti-RNP or Sm positivity. We did find that SSA positive patients had a non-statistically significant trend towards higher IL-23 levels than SSA negative patients.

Taking all these results together we concluded that IL-23 is upregulated in patients with active disease, and especially patients who have active nephritis, dermatitis and arthritis.

Discussion

Herein we provide evidence that IL-23 is detected in the serum of SLE patients, and its levels correlate with clinical disease activity and the commonly used laboratory parameters C3 and anti-dsDNA antibodies. This report follows our earlier finding that active but not SLE patients with quiescent disease have higher levels of IL-23 than control individuals. Importantly patients with low disease activity have, as previously found, almost undetectable IL-23 levels. It is important to note that not all manifestations of SLE are associated with increased IL-23 levels, suggesting but not proving variability in the mechanisms that underly different disease manifestations in SLE. In particular we found that patients with nephritis, cutaneous manifestations and arthritis had elevated IL-23 levels. Contrary to our results, Mok et al.11 did not find elevated IL-23 levels in SLE patients compared to controls or between active and inactive patients. Several studies have shown though that IL-23 is elevated in patients with active renal disease.10,12-14 Moreover, in a report by Fischer et al14 IL-23 levels were found to correlate with surrogate indicators of atherosclerosis and obesity in SLE patients, suggesting a role of this cytokine in the aberrant metabolism of SLE as well. Furthering this, our results suggest a broad role of IL-23 in the pathogenesis of not only nephritis, but also lupus arthritis and dermatitis.

Our finding that IL-23 levels correlate strongly with anti-dsDNA antibody positivity is quite intriguing. Previously we have shown that peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with SLE and treated in vitro with IL-23 produce higher levels of T cell dependent anti-dsDNA antibodies.3 This was associated with a reversal of the extrafollicular T follicular helper cells (eTfh) to regulatory T cells (Treg) ratio in favor of the eTfh. Current theory proposes that in SLE, eTfh play an outsize role in providing help to B cells to produce potentially pathogenic auto-antibodies such as anti-dsDNA antibodies. In support of this hypothesis, we showed that in murine models of lupus, blocking IL-23 signaling by deleting the receptor for IL-23, restores Treg levels and decreases the production of anti-dsDNA antibodies.4,14 In addition, murine lupus models lacking IL-23p19 or IL-23 receptor had significantly decreased renal glomerular and interstitial injury vs. control mice.3,5 These murine data suggested an important role for IL-23 in lupus nephritis but could not address well the role of IL-23 in other manifestations of SLE. Our data show that IL-23 may be playing a wider role in SLE, including arthritis and dermatitis. They also further support the role of IL-23 in pathogenic auto-antibody production and complement activation.

In our cohort, medications used for mild or severe lupus manifestations did not affect IL-23 levels suggesting that current drugs used in SLE may not be as effective in shutting down the IL-23/IL-17 axis. As discussed above, the anti-IL-23/IL-12 monoclonal antibody Ustekinumab, already approved for psoriatic arthritis, has shown promising results in a phase 2 clinical trial in SLE and is currently under investigation in a large phase 3 trial. Importantly though, there are several biologic medications specifically targeting IL-23 currently in clinical practice for the treatment of a variety of autoimmune diseases: our findings urge the exploration of these antibodies as therapeutic options in renal as well as non-renal SLE.

In conclusion, we found that IL-23 levels are not only elevated in patients with lupus nephritis but also in patients with non-renal lupus and in particular patients with arthritis and cutaneous disease. Patients who are serologically active with positive anti-dsDNA antibodies and/or low C3 levels are also more likely to have elevated levels of IL-23. Future studies will be needed to address whether serum IL-23 levels can serve as a biomarker of renal, dermatologic and musculoskeletal flares in lupus as well as predictor of response to biologics targeting the IL-23 pathway.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by NIAMS R01AR060849 (VCK).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Theofilopoulos AN, Kono DH and Baccala R. The multiple pathways to autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 2017; 18: 716–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M and Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27: 485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai H, He F, Tsokos GC and Kyttaris VC. IL-23 limits the production of IL-2 and promotes autoimmunity in lupus. J Immunol 2017; 199: 903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Z, Kyttaris VC and Tsokos GC. The role of IL-23/IL-17 axis in lupus nephritis. J Immunol 2009; 183: 3160–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyttaris VC, Zhang Z, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M and Tsokos GC. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor deficiency prevents the development of lupus nephritis in C57BL/6-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol 2010; 184: 4605–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crispin JC, Oukka M, Bayliss G, et al. Expanded double negative T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus produce IL-17 and infiltrate the kidneys. J Immunol 2008; 181: 8761–8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyttaris VC, Kampagianni O and Tsokos GC. Treatment with anti-interleukin 23 antibody ameliorates disease in lupus-prone mice. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 861028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Vollenhoven RF, Hahn BH, Tsokos GC, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, an IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitor, in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a multicentre, double-blind, phase 2, randomised, controlled study. Lancet 2018; 392: 1330–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zickert A, Amoudruz P, Sundström Y, Rönnelid J, Malmström V and Gunnarsson I. IL-17 and IL-23 in lupus nephritis – association to histopathology and response to treatment. BMC Immunol 2015; 16: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mok MY, Wu HJ, Lo Y and Lau CS. The relation of interleukin 17 (IL-17) and IL-23 to Th1/Th2 cytokines and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2010; 37: 2046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dedong H, Feiyan Z, Jie S, Xiaowei L and Shaoyang W. Analysis of interleukin-17 and interleukin-23 for estimating disease activity and predicting the response to treatment in active lupus nephritis patients. Immunol Lett 2019; 210: 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia LP, Li BF, Shen H and Lu J. Interleukin-27 and interleukin-23 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: possible role in lupus nephritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2015; 44: 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer K, Przepiera-Bȩdzak H, Sawicki M, Walecka A, Brzosko I and Brzosko M. Serum interleukin-23 in polish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: association with lupus nephritis, obesity, and peripheral vascular disease. Mediators Inflamm 2017; 2017: 9401432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]