Abstract

Background:

As the nature of the association between Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) and other disorders is not well understood, the ways in which psychological distress changes during the course of treatment for AUD are relatively unknown. Existing literatures posit two competing hypotheses such that treatment for AUD concurrently decreases alcohol use and psychological distress or treatment for AUD decreases alcohol use and increases psychological distress. The current study examined the ways in which psychological distress changed as a function of treatment for AUD, including the relationship between psychological distress and drinking behaviors.

Methods:

Secondary data analysis was conducted on an existing clinical trial dataset that investigated the effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy and therapeutic alliance feedback on AUDs. Specifically, data collected at baseline, post-treatment, 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month follow-up assessments were examined.

Results:

Results indicated decreases in heavy drinking days, increases in percentage of days abstinent, and decreases in overall psychological distress. Findings also revealed that changes in psychological distress did not predict changes in drinking at the next time interval; however, decreases in drinking predicted higher psychological distress at the next assessment. Further, average levels of psychological distress were positively associated with rates of drinking.

Conclusions:

The current study provides some insight for how psychological distress changes during the course of treatment for AUD, including the relationship between changes in drinking and such symptoms. Future research should continue to explore these relationships, including the ways in which treatment efforts can address what may be seen as paradoxical effects.

Keywords: Alcohol Use Disorder, Treatment, Psychological Distress

Introduction

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) is highly comorbid with other substance use disorders as well as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, and personality disorders regardless of degree of severity of alcohol dependence (Grant et al., 2015). Symptoms of psychopathology that cut across a range of diagnoses, including psychological distress and emotion dysregulation, are among the symptoms most closely related to problematic alcohol use (Berking et al., 2011, Falk et al., 2008, Gamble et al., 2010, Willinger et al., 2002). As compared to individuals with only AUD, those with AUD and comorbid psychological distress exhibit greater symptom severity, poorer physical and mental health, have higher rates of relapse and attrition in treatment, and worse long-term outcomes resulting in repeated treatment attempts and more frequent visits to hospitals and emergency rooms (e.g. Kessler, 2004, Kushner et al., 2005, Mark, 2003, Pettinati et al., 2013). The presence of high levels of distress may affect the course, prognosis, and treatment of AUD, as interactions between symptoms may lead to an intensification in the symptoms of either or both conditions (Gadermann et al., 2012, Lynskey, 1998, Sher et al., 2008), exacerbating the difficulties of treating AUD.

Despite a wealth of research on the co-occurrence of AUD and psychiatric disorders, no single or consistent pattern for the ways in which AUD and psychological distress (broadly defined as co-occurring psychiatric symptoms) interact to influence each other both during and after treatment has emerged. In fact, reviews of the dual diagnosis literature (Mueser et al., 1998, Kessler, 2004) have identified support for three major etiological theories that attempt to explain the high rates of comorbidity between alcohol and other drug use disorders and other psychiatric disorders in which high levels of distress are common: a) common factor models, in which factors such as genetics, socioeconomic status (SES), and cognitive functioning serve as vulnerabilities for both disorders; b) secondary alcohol or other drug use disorder models, in which another psychiatric disorder that develops first contributes to the development of an alcohol or other drug use disorder through factors including poor cognitive skills, lack of structured daily activities, psychobiological vulnerability, and drinking to alleviate distress; and c) secondary psychiatric disorder models, in which an alcohol or other drug use disorder develops first and contributes to the development of a subsequent psychiatric disorder through factors including biological mechanisms resulting from use, increased stress exposure due to negative consequences of use, and decreased resources (e.g., social support) to effectively cope with stress. Drawing upon this literature, a case could be made for multiple competing hypotheses. For example, reductions in alcohol use may improve overall functioning, as indicated by lessening psychological distress. In contrast, reductions in alcohol use may serve to exacerbate psychological distress among those who use alcohol as a means of alleviating negative affect or coping with stressors. The current study aims to investigate these relationships by examining the ways in which comorbid psychological distress and drinking behaviors change and relate to one another during and following an episode of outpatient AUD treatment.

Psychological Distress and Alcohol Use: Temporal Relationships

One way to characterize the association between psychological distress and alcohol use is based on the temporal onset of symptoms. For example, longitudinal and epidemiological studies have shown that pre-existing psychological disorders and distress frequently precede the onset of AUD (e.g. Farmer et al., 2016, Kessler, 2004, Kessler et al., 2003, Kushner et al., 1999, Slade et al., 2013, Vollebergh et al., 2001, Zimmermann et al., 2003) and positively predict later development of AUD (e.g. Farmer et al., 2016, Swendsen et al., 2010, Kessler, 2004, Slade et al., 2013). The development of AUD secondary to pre-existing symptoms has long been characterized by mechanisms of positive and negative reinforcement. Evolving from Reinforcement Theory (e.g., the Tension Reduction Hypothesis; Conger, 1956), several theories (e.g., Self-Medication Hypothesis: Khantzian, 1974, Khantzian, 1978, Khantzian, 1999, Motivational Model of Alcohol Use: Cooper et al., 1995) posit that alcohol use is motivated by the expectation of or desire to alter the experience of emotion or psychological distress, and such behavior is strengthened through positive and negative reinforcement. Thus, attempts to regulate affective experiences may be an important factor in the maintenance of psychological distress and alcohol use.

In contrast, psychological distress may be induced or markedly exacerbated by alcohol use and dependence (i.e, psychological distress may be secondary to the alcohol use). For example, AUD may be a risk factor for subsequent psychological distress (e.g., emotional distress and dysregulation) through the experience or worsening of drinking related negative consequences (Burns et al., 2005, Sullivan et al., 2005), including disruption in interpersonal relationships, workplace difficulties, legal trouble, and deterioration of physical health (Sullivan et al., 2005, Foster et al., 1999). Further, those with an AUD tend to report lower overall quality of life compared to those without an AUD, and increases in alcohol use are associated with increasingly poorer quality of life (Colpaert et al., 2013, Senbanjo et al., 2007). Thus, AUD has the potential to induce psychological distress indirectly by contributing to biopsychosocial consequences.

An additional pathway in which alcohol dependence may lead to acute psychological distress is through alcohol craving and withdrawal processes. Craving, or the urge or desire to use a drug, has consistently been found to be both a cause and consequence of affective processes (Baker et al., 2006, Baker et al., 1986, Baker et al., 2004, Tiffany, 2010, Kavanagh et al., 2005). Cue-reactivity studies have found that affect manipulations impact craving urges and conversely, craving manipulations impact affective ratings (e.g. Carter and Tiffany, 1999, Cooney et al., 1997, Fox et al., 2007, Niaura et al., 1988, Nosen et al., 2012). Thus, craving may induce or exacerbate internalizing states related to depressive and anxiety disorders (e.g. Baker et al., 2004). Relatedly, pharmacological and behavioral withdrawal symptoms often result in negative affect and craving, which in turn predict relapse (Baker et al., 2006, Baker et al., 2004, Tiffany, 2010).

Unfortunately, the mixed findings in the literature fail to clarify whether psychological distress acts as a risk factor for the development of AUD, or if distress and alcohol use are a bidirectional risk factor for each other (Boden and Fergusson, 2011, Kessler, 2004). Despite the lack of clear consensus, the strongest evidence suggests a bidirectional causal association (e.g. Kessler, 2004, Kushner, 2000, Slade et al., 2013, Witkiewitz and Wu, 2010). Consistent with models of reciprocal effects, a feed-forward cycle may best characterize the relationship between AUD and psychological distress (e.g., Trull et al., 2000, Kushner et al., 2005, Strakowski and DelBello, 2000). In this cycle, drinking is maintained by immediate reinforcement, which in turn worsens psychological functioning due to negative consequences. As a result, drinking follows the worsening of symptoms, and so forth. The feed-forward cycle has considerable implications for the maintenance of psychological distress and alcohol use.

Current Study

The development of broadly effective treatment approaches for individuals with AUD is hindered by the insufficient and conflicting empirical support regarding the nature of the relationship between AUD and psychological distress. By examining the course of distress during and after treatment for AUD in data from a clinical trial that measured both drinking and distress pre- and post-treatment, as well as every 3 months following treatment, the current study was designed to help elucidate the maintenance of co-occurring psychological distress in hopes of better understanding how distress and drinking may serve to reinforce one another over time. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to test two competing hypotheses: 1) co-occurring psychological distress and alcohol use decrease during and after AUD treatment, and 2) psychological distress increases as alcohol use decreases. Further, we explored whether changes in distress following treatment are associated with alcohol use.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 175 individuals who were seeking outpatient treatment for AUD recruited using local newspaper and radio advertisements. Participants were recruited to take part in a study examining the effect of providing therapists with session-to-session therapeutic alliance feedback on treatment outcomes (see Maisto et al., 2020). Inclusion criteria were: (1) were seeking outpatient help for a drinking problem and met criteria for alcohol dependence based on the fourth edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), (2) were between the age of 18 and 85 years, (3) resided within commuting distance of the program site, (4) exhibited a level of reading that would allow them to complete assessment materials, and (5) willingly signed the informed consent form and agreed to complete all dimensions of the investigation. Participants were excluded if they (1) had met criteria for a current psychotic disorder, (2) demonstrated gross neurocognitive impairment, or (3) had received treatment for substance use disorder currently or in the past year.

Participants were 34.29% female with a mean age of 48.5 years (SD = 8.95), 13.8 years (SD = 2.77) of education on average, 93.7% were White and 2.9% were African American, 45% were either married or cohabitating, and 55% were employed full time. Approximately 38% of participants reported receiving treatment previously (but not in the past twelve months). In the six months preceding admission, participants averaged 26% days abstinent (PDA; SD = 27) and 58% heavy drinking days (PHD; SD = 9.4), with heavy drinking defined as 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women (see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1.

Summary of Means (SD), Medians, Modes, and Ranges for Variables of Interest

| Baseline (n=175) | Post-Tx (n=168) | 3-month (n=158) | 6-month (n=156) | 9-month (n=153) | 12-month (n=151) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDA* | Mean | .261 (.268) | .786 (.271) | .801 (.302) | .743 (.337) | .757 (.329) | .749 (.352) |

| Median | .161 | .900 | .956 | .939 | .933 | .956 | |

| Mode | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Range | 0 – .91 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | |

| PHD* | Mean | .579 (.326) | .116 (.207) | .114 (242) | .144 (.268) | .145 (.277) | .142 (.278) |

| Median | .594 | .033 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mode | .990 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Range | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – .96 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | 0 – 1.00 | |

| BSI-Global | Mean | .864 (.600) | .585 (.541) | .602 (.587) | .575 (.552) | .583 (.586) | .600 (.639) |

| Median | .755 | .415 | .415 | .415 | .387 | .377 | |

| Mode | .38 | .08 | .09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Range | 0 – 2.51 | 0 – 2.57 | 0 – 2.72 | 0 – 2.53 | 0 – 3.13 | 0 – 3.40 | |

Note: PDA = Percent Days Abstinent; PHD = Percent Heavy Drinking; BSI-Global = Brief Symptom Inventory-Global Severity Index; Post-Tx = Post (end of) Treatment; SD = Standard Deviation.

Values of PDA and PHD represent percentages such that 0 = 0% and 1.00 = 100%.

Measures

Participants completed assessments (i.e., interviews and questionnaires) prior to treatment (baseline), the end of treatment (twelve weeks), and three, six, nine, and twelve months after treatment had ended. The baseline and follow-up evaluations both utilized the Timeline Follow-Back (Sobell and Sobell, 1992), which gauged drinking behavior and included questionnaires that measured drinking consequences, other drug use, and general psychosocial functioning. Demographics were captured using a questionnaire administered during the baseline measurement.

Timeline Follow-Back

Timeline follow-back (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell, 1992). is a calendar based retrospective recall of daily drinking data. TLFB was administered at baseline to measure drinking data for the 6 months prior to intake, at the end of treatment (12 weeks), and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after treatment with each assessment covering the time period since the previous assessment. Participant responses were summed to create two metrics of drinking behavior: Percent Days Abstinent (PDA) and Percent Heavy Drinking Days (PHD) which are commonly used in the literature. The TLFB measures have consistently proven reliable and accurate in this population for both alcohol and other substance use (Ehrman and Robbins, 1994, Sobell et al., 1996, Sobell and Sobell, 1992).

Brief Symptom Inventory

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983), a 53-item brief version of the Symptom Checklist-90—revised (Derogatis and Unger, 2010), was administered at baseline, the end of treatment, and at three, six, nine, and twelve-month follow-up appointments. It is a psychometrically sound measure of psychological functioning, and the Global Severity Index (BSI-Global Severity) acts as a measure of overall psychological distress reflective of symptoms of psychopathology (Derogatis and Unger, 2010). It is important to note that items on the BSI-Global Severity Index are not confounded with items related to alcohol or drug use.

Procedure

Initial screening interviews were scheduled for all potential participants who were referred to the treatment site or responded to newspaper advertisements. Eligible participants were scheduled for a baseline assessment and randomized to therapists who either received or did not receive therapeutic alliance feedback throughout treatment. All participants, regardless of therapeutic alliance feedback condition, received twelve weeks of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT; Kadden et al., 1992) tailored to treat AUD, which was conducted in an outpatient research clinic by experienced therapists. The first seven sessions were considered core sessions, consisting of Introduction to Coping Skills Training, Coping with Cravings and Urges to Drink, Managing Thoughts About Alcohol and Drinking, Problem Solving, Drink Refusal Skills, Planning for Emergencies and Coping with a Lapse, and Seemingly Irrelevant Decisions. The therapist and patient then identified the patient’s clinical needs and conducted additional sessions (e.g., Starting Conversations, Assertiveness, Anger Management, Managing Negative Thinking, and Enhancing Social Support Networks). Treatment gains and termination were discussed during the final session, occurring in the twelfth week of treatment. Participants completed assessments at baseline prior to treatment, throughout treatment, and for twelve months post-treatment. For more details on the procedures, see Maisto et al., in press.

Data Analytic Strategy

Multilevel modeling using HLM 7.03 (Raudenbush et al., 2017) was conducted to examine changes in both drinking and psychological distress during treatment and post-treatment, as well as the relationship between drinking and psychological distress. Data were nested on two levels: measurements within participants. First, to examine how alcohol consumption and psychological distress changed from baseline through the 12-month follow-up (six time points: baseline, post treatment, 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month), linear growth, linear growth with random slope, quadratic growth, and quadratic growth with random slope models were evaluated. Specifically, deviance testing was conducted to examine if inclusion of additional terms improved the fit of the overall model (initial model fit was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation; ML). Following the identification of the best fitting model, final model parameters were estimated with restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML).

To examine the bidirectional relationship between drinking and psychological distress, scores on PDA, PHD and BSI-Global Severity were divided into two levels: within-person effect and between-person effects. To disaggregate the two effects for each variable (PDA, PHD, BSI-Global Severity), we followed recommendations by (Curran and Bauer, 2011) by applying linear regression of the outcome against the best fitting growth model (with time centered at the mean session). Specifically, following the identification of the best fitting growth model (i.e., quadratic random effect, see results below), residuals and intercepts from these regression models were used to represent within-person and between-person effects. Specifically, the within-person effect was measured by the difference between the observed measurement and it’s expected value given growth over time (i.e., residuals). The estimated intercepts at level 2 were used to obtain the between effects.

Using the above approach, four random slope models were tested: a) PDA predicting BSI-Global Severity, b) PHD predicting BSI-Global Severity, c) BSI-Global Severity predicting PDA, and d) BSI-Global Severity predicting PHD. For each model, lagged within-person effects and outcomes were entered on level 1. Further, because the within-person effects represented deviation scores (i.e., residuals), these effects were entered into models without further centering. In contrast, the between-person effect was grand mean centered and modeled on the intercept at level-2.

Results

Unconditional Models and Intraclass Correlations

To examine the proportion of variance accounted for due to clustering (i.e., correlation among observations within person), unconditional models for each outcome were conducted (PDA, PHD, and BSI-Global Severity index). The ICCs for the unconditional models for PDA, PHD, and BSI-Global Severity were .391, .328, and .719, suggesting that 33% to 72% of the variance in outcome measures are accounted for the grouping structure of the data. Further, all random intercepts were significant, p’s <.001.

Description of Change

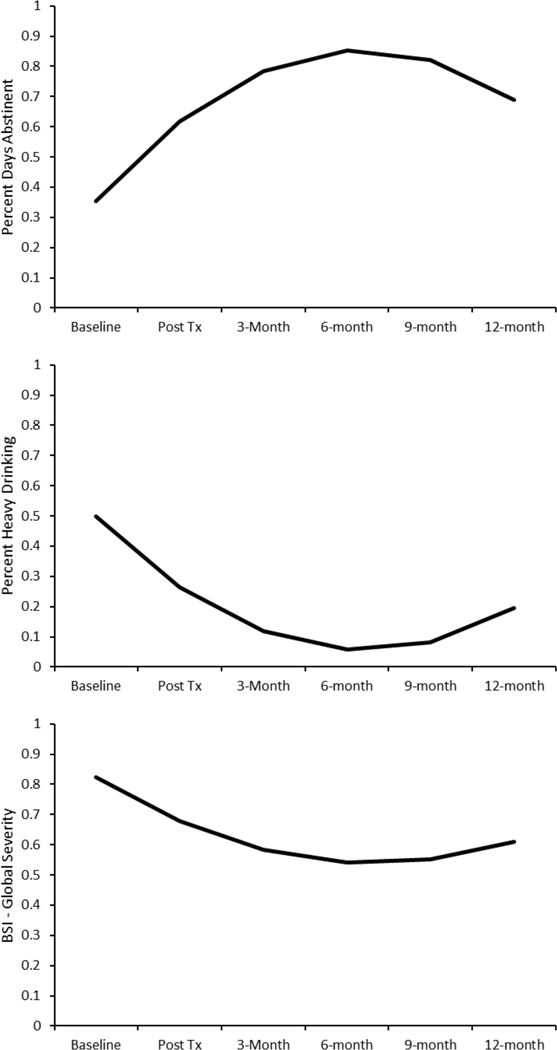

Based on deviation statistics, results indicated that the random quadratic model best fit the data for PDA (quadratic versus quadratic with random slope; χ2(3) = 31.27, p < .001), PHD (χ2(3) = 41.81, p < .001), and BSI-Global Severity (χ2(3) = 26.65, p < .001). See Table 2 and Figure 1 for summary of results. In short, significant increases were observed for PDA from baseline to post-treatment (i.e., significant linear fixed effect), followed by a slowing effect during followup with a potential decrease by 12-month followup (i.e., significant quadratic fixed effect). Similarly, both PHD and BSI-Global Severity had significant overall decreases from baseline to post-treatment (i.e., significant linear fixed effect), followed by a slowing effect and eventual increase at 12-months follow-up (i.e., significant quadratic effect).

Table 2.

Final Growth Curve Models (Restricted Maximum Likelihood Estimation)

| Percent Days Abstinent | Percent Heavy Drinking | BSI – Global Severity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p |

| Intercept | .352 | .018 | <.001 | .499 | .0212 | <.001 | .823 | .044 | <.001 |

| Time (fixed effect) | .315 | .017 | <.001 | −.277 | .017 | <.001 | −.171 | .024 | <.001 |

| Time2 (fixed effect) | −.050 | .003 | <.001 | .043 | .003 | <.001 | .026 | .004 | <.001 |

| Random Effects Variances | Var | χ2 | P | Var | χ2 | P | Var | χ2 | P |

| Intercept | .029 | 303.387 | <.001 | .053 | 486.434 | <.001 | .275 | 870.097 | <.001 |

| Time (random effect) | .021 | 283.131 | <.001 | .025 | 329.540 | <.001 | .037 | 247.684 | <.001 |

| Time2 (random effect) | .0004 | 232.705 | <.001 | .0005 | 265.056 | <.001 | .0008 | 203.277 | <.001 |

| Level-1, e | .037 | --- | --- | .031 | --- | --- | .067 | --- | --- |

Note: b = unstandardized estimates; SE = standard error; BSI-Global Severity = Brief Symptom Inventory-Global Severity Index; PDA = Percent Days Abstinent; PHD = Percent Heavy Drinking

Figure 1.

Final Growth Curves for Average Percent Days Abstinent (top panel), Average Percent Heavy Drinking (middle panel) and Average BSI-Global Severity (bottom panel)

Prior Psychological Distress Predicting Drinking

To examine the relation between prior psychological distress and current drinking outcomes, each drinking outcome was predicted from prior reports of the within-person and between-person component of BSI-Global Severity, controlling for drinking in the prior interval (see Table 3 for summary of results). Results indicated that changes in BSI-Global Severity (within-person component) did not predict percent days abstinent (b = −.020, SE = .032, p = .540) nor percent heavy drinking days (b = .006, SE = .028, p = .823), suggesting that changes in psychological distress were not associated with changes in drinking. However, the between-person component of BSI-Global Severity was associated with both PDA (b = −.118, SE = .033, p < .001) and percent heavy drinking days (b = .076, SE = .010, p < .001), such that those with greater psychological distress on average had fewer percent days abstinent and higher number of heavy drinking days.

Table 3.

Summary of Results for BSI Predicting Drinking Outcomes (full models)

| PDA | PHD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| Intercept | .712 | .026 | <.001 | .076 | .010 | <.001 |

| Mean BSI-Global (between-person effect) | −.118 | .033 | <.001 | .101 | .023 | <.001 |

| Prior Outcome (PDA or PHD) | .134 | .023 | <.001 | .105 | .022 | <.001 |

| Prior BSI-Global (within-person effect) | −.020 | .032 | .540 | .006 | .028 | .823 |

| Random Effects Variances | Var | χ2 | P | Var | χ2 | P |

| Intercept | .082 | 476.76 | <.001 | .008 | 320.17 | <.001 |

| Prior Outcome (PDA or PHD) | .027 | 155.89 | .155 | .028 | 144.52 | .335 |

| Prior BSI-Global | .031 | 207.60 | <.001 | .023 | 216.81 | <.001 |

| Level-1, e | .021 | -- | -- | .016 | -- | -- |

Note: b = unstandardized estimates; SE = standard error; BSI-Global = Brief Symptom Inventory-Global Severity Index; PDA = Percent Days Abstinent; PHD = Percent Heavy Drinking

Prior Drinking Predicting Psychological Distress

To examine the relation between prior drinking and subsequent psychological distress, BSI-Global Severity ratings was predicted from prior reports of either the within-person and between-person effects of percent days abstinent or percent heavy drinking days, controlling for prior BSI-Global Severity (see Table 4 for summary). Results indicated that both prior within-person effects of percent days abstinent (b = .154, SE = .068 p = .025) and percent heavy drinking days (b = −.204, SE = .078 p = .010) predicted changes in BSI-Global Severity, such that greater number of days abstinent and fewer heavy drinking days predicted higher psychological distress. Furthermore, the between-person effects of both percent days abstinent (b = −.647, SE = .037 p < .001) and percent heavy drinking days (b = .799, SE = .151 p < .001) was associated with BSI-Global Severity, such that greater frequency of drinking and a higher number of heavy drinking days predicted higher psychological distress.

Table 4.

Summary of Results for Prior Drinking Predicting BSI-Global Severity

| b | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Prior Percent Days Abstinent (PDA) | |||

| Intercept | .443 | .037 | <.001 |

| Mean PDA (between-person effect) | −.647 | .119 | <.001 |

| Prior BSI-Global | .198 | .042 | <.001 |

| Prior PDA (within-person effect) | .154 | .068 | .025 |

| Random Effects Variances | Var | χ2 | P |

| Intercept | .118 | 315.24 | <.001 |

| Prior BSI-Global | .064 | 158.12 | .047 |

| Prior Drinking Days | .042 | 171.45 | .009 |

| Level-1, e | .061 | -- | -- |

| b | SE | p | |

| 2. Prior Percent Heavy Drinking Days | |||

| Intercept | .434 | .036 | <.001 |

| Mean PHD (between-person effect) | .799 | .151 | <.001 |

| Prior BSI-Global | .205 | .042 | <.001 |

| Prior PHD (within-person effect) | −.204 | .078 | .010 |

| Random Effects Variances | Var | χ2 | P |

| Intercept | .109 | 313.78 | <.001 |

| Prior BSI-Global | .063 | 160.22 | .042 |

| Prior Drinking Days | .070 | 168.36 | .015 |

| Level-1, e | .061 | -- | -- |

Note: b = unstandardized estimates; SE = standard error; BSI-Global = Brief Symptom Inventory-Global Severity Index; PDA = Percent Days Abstinent; PHD = Percent Heavy Drinking

Discussion

The results of this study showed that during treatment patients experienced fewer days of drinking, a decrease in number of heavy drinking days, and decreased psychological distress. The data also revealed that changes in psychological distress (relative to one’s own mean) did not predict changes in drinking at the next time interval, but that changes in drinking (relative to one’s mean) predicted changes in BSI-Global Severity at the next assessment. Specifically, decreases in drinking predicted higher psychological distress. Finally, although changes in psychological distress did not predict changes in drinking, on average those with higher overall psychological distress reported higher rates of drinking.

Although initial growth suggested that both alcohol use and psychological distress measured weekly during treatment decreased concurrently and were positively associated with one another, the relationship between changes in drinking and psychological distress did not follow similar patterns once treatment ended. Specifically, our findings suggested that following treatment lower alcohol use predicted greater psychological distress at the next follow-up assessment 3 months later, and that greater psychological distress did not predict higher alcohol use. This finding supports the hypothesis that decreases in drinking predict increases in psychological distress and are consistent with several theoretical models of addiction and alcohol use. For example, the opponent-process model (Solomon, 1980) and the dual-affect model (Tiffany, 2010, Baker et al., 1986) are based on the premise that all addictive agents, alcohol included, can have withdrawal syndromes where negative affect and other comorbid symptomology are present (for review see Tiffany, 2010). Such aversive withdrawal syndromes can be produced by falling levels of alcohol within the body, with only a few uses of alcohol needed to trigger such a response (Baker et al., 2004). Although most withdrawal symptoms typically only last a few days, symptoms associated with psychological distress last much longer (Becker, 2008), with some symptoms of withdrawal still present after as long as a year (Martinotti et al., 2008). Thus, the comorbid symptoms seen in this study could be due in part to both the pharmacological effects of alcohol during early withdrawal (Schuckit, 2009), as well as longer term symptoms of withdrawal that may last up to a year or longer.

Extrapolation from the alcohol and drug use motivation literature, as well as models of relapse prevention, suggests that the “removal” of alcohol use may have several psychological consequences. The notion that individuals use alcohol for both the euphoric and positive reinforcement effects (e.g. Cooper et al., 1995, Goldman et al., 1999), as well as for reasons of “self-medication” or negative reinforcement properties (e.g. Greeley and Oei, 1999, Sayette, 1999, Sher, 1987) enjoys a long history of support. As such, cessation of alcohol use (a goal of many treatments) may inadvertently result in concurrent increases in subjective distress due to the removal of a potential “coping strategy” and/or pleasurable activity. Therefore, alcohol abstinence in some ways may mimic a “psychological loss.” Indeed, relapse prevention models (Marlatt and Witkiewitz, 2005) stress not only the importance of monitoring negative affective states, but also stress the importance of “lifestyle balance” and alternative positive activities (e.g., meditation, exercise). Such strategies may be particularly important long term as individuals begin to adjust to lifestyle changes made during treatment.

Alternatively, it is possible that following treatment those in recovery are more likely to experience psychological distress as they continued to struggle maintaining abstinence or moderated drinking, particularly following a lapse. This may be true even if lapses occur only a few times within the 90-day assessment period. Indeed, Maisto et al., 2019 found that changes in alcohol use post-treatment represents a process in which individuals transition in and out of “remsission” and “relapse” status (defined as heavy drinking day), identifing 6 profiles (remission, transition to remission, few long transitions, many short transitions, transition to relapse, and relapse). Findings also indicated that those with numerous short tranistions (quick lapses and returns to remission) and few longer transitions reported similar levels of depression when compared to those who transition to relapse or had continuous relapse at 1-year followup, which was higher when compared to those in remission and those with one transition to remission. These findings suggest that attempts at abstinence or moderated drinking may be related to greater psychological distress when experiencing lapses during recovery. Such an interpretation is consistent with the between-person effects found in the current study such that those with higher than average drinking also experienced higher psychological distress broadly. This may also explain why changes at the within-level found the opposite relationship, such that these individuals may be trying to maintain abstinence or moderate their drinking (decreases PDA and PHD at the within-person level) any any slip is viewed by them negatively. Future research would benefit from consideration of the timing of assessments when examining the relations between drinking and psychological distress, including the potential mechanisms underlying such relations (e.g., withdrawal symptoms versus “psychological loss” versus struggling to maintain abstinence/moderated drinking).

Consistent with past research, the finding that both alcohol consumption and BSI-Global Severity decreased from baseline to post-treatment suggests that treatment targeting drinking outcomes may impact other areas of psychological functioning. For example, Kushner et al. (2005) found that general anxiety disorder and depression decreased after the completion of CBT for Alcohol Dependence relative to baseline measurements. Recent reviews have theorized that a large percentage of variability in treatment outcomes can be attributed to non-specific factors common to many therapies (Miller and Moyers, 2014, Wampold, 2015). Therapists’ empathy, expectations, treatment fidelity, and interpersonal skills along with patients’ motivation, self-efficacy, hope, and readiness to change are examples of such non-specific treatment factors. Thus, it could be inferred that some features inherent in the treatment for AUD (e.g., therapeutic relationship) could have assisted in decreasing concurrent psychological distress.

The results of the current study have clinical implications. As previously discussed, increases in psychological distress associated with decreases in drinking may have paradoxical effects of placing individuals at risk for relapse. Indeed, research has shown negative symptomology (e.g., negative affective states) reinforces alcohol use, and those with comorbid diagnoses are more prone to relapse following the completion of alcohol treatment (Kessler, 2004, Kushner et al., 2005, Mills et al., 2009, Pettinati et al., 2013). Although changes in psychological distress did not predict changes in drinking, those who experienced higher levels of psychological distress had higher rates of drinking post-treatment. Efforts to address withdrawal induced negative affect and potential “psychological loss” associated with decreases in alcohol use will be important not only during treatment but also during periods of sustained abstinence. Aftercare or booster sessions post-treatment may help address any distress that may arise as a result of reductions in alcohol use. In this regard, incorporation of “behavioral activation” strategies may be integral for increasing alternative positive activities to replace alcohol use. Such strategies are consistent with suggestions outlined by Marlatt and Gordon (1985) over three decades ago, which argued for “positive addictions.”

Relatedly, results of the current study also point to the importance of considering outcomes besides alcohol consumption. As Kazdin (1999) noted, “it is still quite possible that multiple clients meet the operational definitions of clinically significant change but, in fact, are not functioning much better, do not feel better, or are not seen as improved by significant others” (p. 338). Although alcohol consumption remains the primary treatment outcome measure for alcohol use clinical trials, researchers have long argued for the inclusion of additional measures (e.g., Moos and Finney, 1983). Indeed, recent findings have not only demonstrated the predictive value of non-consumption outcome measures in the treatment of AUD (e.g., Kirouac and Witkiewitz, 2019), but that positive outcomes for AUD treatment can include non-abstinence (e.g., Witkiewitz and Tucker, 2020, Falk et al., 2019). Although the current study found that overall psychological distress was decreasing, focusing exclusively on reduction in drinking may result in higher psychological distress and misrepresent what the client is fully experiencing.

There are several limitations of this study that warrant consideration in interpretation of its findings. Specifically, the current study is a secondary data analysis of a clinical trial investigating the influence of providing therapists with feedback on participant ratings of therapeutic alliance on treatment outcomes, and, as such, several methodological considerations may affect the conclusions drawn. First, although follow-up assessments were conducted every three months following treatment, more frequent measurements would allow for a more dynamic examination of the interplay between drinking and psychological distress. Indeed, recent recommendations for studying treatment processes have called for researchers to pay closer attention to the timing of assessments (Witkiewitz et al., 2015). This is particularly important, as the mechanism underlying the relation between drinking and psychological distress may vary based on early versus later stages of treatment/recovery. Second, data on comorbid diagnoses were not available, nor information about previous or concurrent treatment of such disorders. Thus the impact of such variables on the current findings is unknown, and future research should examine whether associations between alcohol consumption and distress differ between those with and without a comorbid psychiatric condition, as well as whether the associations differ among individuals with different psychiatric conditions. Additionally, individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for psychotic disorders were excluded, limiting the generalizability of these findings to those diagnosed with an AUD and severe mental illness. Third, although several reviews suggest similar treatment effects across different treatment modalities, cognitive-behavioral therapy was the only treatment approach used in treating patients enrolled in this study. Therefore it is unclear if or how different treatment approaches may alter the current findings. Fourth, craving data was only available for a small subset of participants that was not sufficient to analyze for use in the current study, and as such we could not examine associations between craving, alcohol use, and psychological distress. This should be explored in future research, as craving may have an impact on the associations between alcohol use and distress we found in the current study.

Although a major advantage of our data analytic strategy is the ability to more accurately estimate between- and within-person effects, a limitation of random slope models is that effect sizes cannot be estimated (see Lorah, 2018). Given the low within-person variability of distress in our sample, effects sizes would have helped to put the relative contributions of between- and within person PDA and PHD on changes in distress into context. Concerns over the low variability, however, are somewhat mitigated by our findings that prior within-person PDA and PHD significantly predicted distress at the next assessment after controlling for prior distress scores. It is also possible that prior distress may be a stronger predictor of time to first lapse or relapse, however due to both theoretical concerns (i.e., definitions of lapse/relapse as well as its utility as a construct; see Maisto et al., 2016a, Maist et al., 2016b; Maisto et al., 2018) and the nature of our data collection (i.e., TLFB 90 day form instead of more frequent assessments of alcohol use instead of weekly to obtain more accurate daily levels of alcohol use; see Hoeppner et al., 2010), examination of the between- and within-person associations between distress and time until first drink following treatment were beyond the scope of this study. As mentioned previously, future research examining this topic would do well to include assessments of alcohol use on a daily or weekly level to examine these associations in more granular detail and possibly capture more within-person variations in distress.

In summary, the current study provides some insight for how psychological distress changes during the course of treatment for AUD, including the relationship between changes in drinking and such symptoms. Future research should continue to explore these relationships, including the ways in which treatment efforts can address what may be seen as paradoxical effects.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant R01 AA020253 (Connors/Maisto). The development of this report was supported in part by NIAAA grants K23-AA021768 (Schlauch) and 2K05 AA016928 (Maisto).

Contributor Information

Jacob A. Levine, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620.

Becky K. Gius, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620.

George Boghdadi, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620..

Gerard J. Connors, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, 1021 Main St., Buffalo, NY 14203.

Stephen A. Maisto, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, 430 Huntington Hall, Syracuse, NY 13244..

Robert C. Schlauch, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620..

References

- AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- BAKER TB, JAPUNTICH SJ, HOGLE JM, MCCARTHY DE & CURTIN JJ 2006. Pharmacologic and Behavioral Withdrawal From Addictive Drugs. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- BAKER TB, MORSE E. & SHERMAN JE 1986. The motivation to use drugs: A psychobiological analysis of urges. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 34, 257–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKER TB, PIPER ME, MCCARTHY DE, MAJESKIE MR & FIORE MC 2004. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev, 111, 33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKER HC 2008. Alcohol dependence, withdrawal, and relapse. Alcohol Research & Health. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERKING M, MARGRAF M, EBERT D, WUPPERMAN P, HOFMANN SG & JUNGHANNS K. 2011. Deficits in emotion-regulation skills predict alcohol use during and after cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol, 79, 307–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BODEN JM & FERGUSSON DM 2011. Alcohol and depression. Addiction, 106, 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNS L, TEESSON M. & O’NEILL K. 2005. The impact of comorbid anxiety and depression on alcohol treatment outcomes. Addiction, 100, 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER BL & TIFFANY ST 1999. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction, 94, 327–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLPAERT K, DE MAEYER J, BROEKAERT E. & VANDERPLASSCHEN W. 2013. Impact of Addiction Severity and Psychiatric Comorbidity on the Quality of Life of Alcohol-, Drug- and Dual-Dependent Persons in Residential Treatment. European Addiction Research, 19, 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONGER JJ 1956. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 17, 296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COONEY NL, LITT MD, MORSE PA, BAUER LO & GAUPP L. 1997. Alcohol cue reactivity, negative-mood reactivity, and relapse in treated alcoholic men. J Abnorm Psychol, 106, 243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOPER ML, FRONE MR, RUSSELL M. & MUDAR P. 1995. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 990–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURRAN PJ & BAUER DJ 2011. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual review of psychology, 62, 583–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEROGATIS LR & MELISARATOS N. 1983. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEROGATIS LR & UNGER R. 2010. Symptom Checklist-90-Revised The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- EHRMAN RN & ROBBINS SJ 1994. Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALK DE, O’MALLEY SS, WITKIEWITZ K, ANTON RF, LITTEN RZ, SLATER M, KRANZLER HR, MANN KF, HASIN DS & JOHNSON B. 2019. Evaluation of drinking risk levels as outcomes in alcohol pharmacotherapy trials: a secondary analysis of 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA psychiatry, 76, 374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALK DE, YI H-Y & HILTON ME 2008. Age of onset and temporal sequencing of lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders relative to comorbid mood and anxiety disorders. Drug and alcohol dependence, 94, 234–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARMER RF, GAU JM, SEELEY JR, KOSTY DB, SHER KJ & LEWINSOHN PM 2016. Internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of alcohol use disorder onset during three developmental periods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 164, 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOSTER JH, POWELL JE, MARSHALL EJ & PETERS TJ 1999. Quality of life in alcohol-dependent subjects–a review. Quality of Life Research, 8, 255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOX HC, BERGQUIST KL, HONG KI & SINHA R. 2007. Stress-induced and alcohol cue-induced craving in recently abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 31, 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GADERMANN AM, ALONSO J, VILAGUT G, ZASLAVSKY AM & KESSLER RC 2012. Comorbidity And Disease Burden In The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (Ncs-R). Depression and Anxiety, 29, 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAMBLE SA, CONNER KR, TALBOT NL, YU Q, TU XM & CONNORS GJ 2010. Effects of pretreatment and posttreatment depressive symptoms on alcohol consumption following treatment in Project MATCH. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDMAN MS, DARKES J. & DEL BOCA FK 1999. Expectancy mediation of biopsychosocial risk for alcohol use and alcoholism. How expectancies shape experience.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- GRANT BF, GOLDSTEIN RB, SAHA TD, CHOU SP, JUNG J, ZHANG H, PICKERING RP, RUAN WJ, SMITH SM, HUANG B. & HASIN DS 2015. Epidemiology of DSM-5Alcohol Use Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREELEY J. & OEI T. 1999. Alcohol and tension reduction. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism, 2, 14–53. [Google Scholar]

- HOEPPNER BB, STOUT RL, JACKSON KM & BARNETT NP 2010. How good is fine-grained Timeline Follow-back data? Comparing 30-day TLFB and repeated 7-day TLFB alcohol consumption reports on the person and daily level. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 1138–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KADDEN R, CARROLL K, DONOVAN D, MONTI P, ABRAMS D, LITT M. & HESTER R. 1992. Cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual, Rockville, MD, NIAAA. [Google Scholar]

- KAVANAGH DJ, ANDRADE J. & MAY J. 2005. Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: the elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychol Rev, 112, 446–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAZDIN AE 1999. The meanings and measurement of clinical significance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC 2004. The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biol Psychiatry, 56, 730–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, AGUILAR-GAXIOLA S, ANDRADE J, BIJL R, BORGES G. & CARAVEO-ANDUAGA JJ 2003. Cross-national comparisons of comorbities between substance use disorders and mental disorders: Results from the international consortium in psychiatric epidemiology In: BUKOSKI WJ & SLOBODA Z. (eds.) Handbook for Drug Abuse Prevention Theory, Science, and Practice. New York, NY: Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- KHANTZIAN EJ 1974. Opiate addiction: A critique of theory and some implications for treatment. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 28, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHANTZIAN EJ 1978. The ego, the self and opiate addiction: Theoretical and treatment considerations. International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 5, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- KHANTZIAN EJ 1999. Treating Addiction as a Human Process, London, Jason Aronson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- KIROUAC M. & WITKIEWITZ K. 2019. Predictive value of non-consumption outcome measures in alcohol use disorder treatment. Addiction, 114, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSHNER MG 2000. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders A review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 149–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSHNER MG, ABRAMS K, THURAS P, HANSON KL, BREKKE M. & SLETTEN S. 2005. Follow-up Study of Anxiety Disorder and Alcohol Dependence in Comorbid Alcoholism Treatment Patients. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 29, 1432–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSHNER MG, SHER KJ & ERICKSON DJ 1999. Prospective Analysis of the Relation Between DSM-III Anxiety Disorders and Alcohol Use Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LORAH J. 2018. Effect size measures for multilevel models: definition, interpretation, and TIMSS example. Large-scale Assessments in Education,6 10.1186/s40536-018-0061-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LYNSKEY MT 1998. The comorbidity of alcohol dependence and affective disorders: treatment implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 52, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAISTO SA, HALLGREN KA, ROOS CR, & WITKIEWITZ K. 2018. Course of remission from and relapse to heavy drinking folowing outpaitent treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drug and alcohol dependence, 187, 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAISTO SA, ROOS CR, HALLGREN KA, HUTCHINSON D, WILSON AD, & WITKIEWITZ K. (2016b), Do alcohol relapse episodes during treatment predict long-term outcomes?: Investigating the vailidy of existing definitions of alcohol use disorder relapse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research , 40, 2180–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAISTO SA, SCHLAUCH RC, CONNORS GJ, DEARING RL & O’HERN KA 2020. The effects of therapist feedback on the therapeutic alliance and alcohol use outcomes in the outpatient treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44, 960–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAISTO SA, WITKIEWITZ K, MOSKAL D, & WILSON AD 2016b. Is the construct of relapse heuristic, and does it advance alcohol use disorder clinical practice? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77, 849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARK TL 2003. Economic Grand Rounds: The Costs of Treating Persons With Depression and Alcoholism Compared With Depression Alone. Psychiatric Services, 54, 1095–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARLATT GA & GORDON JR 1985. Relapse prevention, New York, NY, Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- MARLATT GA & WITKIEWITZ K. 2005. Relapse Prevention for Alcohol and Drug Problems In: MARLATT GA & DONOVAN DM (eds.) Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, Second Edition. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- MARTINOTTI G, DI NICOLA M, REINA D, ANDREOLI S, FOCÀ F, CUNNIFF A, TONIONI F, BRIA P. & JANIRI L. 2008. Alcohol Protracted Withdrawal Syndrome: The Role of Anhedonia. Substance Use & Misuse, 43, 271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER WR & MOYERS TB 2014. The forest and the trees: relational and specific factors in addiction treatment. Addiction, 110, 401–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLS KL, DEADY M, PROUDFOOT H, SANNIBALE C, TEESSON M, MATTICK R. & BURNS L. 2009. Guidelines on the management of co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings. In: HEALTH DO (ed.). Sydney, Australia: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- MOOS RH & FINNEY JW 1983. The expanding scope of alcoholism treatment evaluation. American Psychologist, 38, 1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUESER KT, DRAKE RE & WALLACH MA 1998. Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Addictive behaviors, 23, 717–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAURA RS, ROHSENOW DJ, BINKOFF JA, MONTI PM, PEDRAZA M. & ABRAMS DB 1988. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 133–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSEN E, NILLNI YI, BERENZ EC, SCHUMACHER JA, STASIEWICZ PR & COFFEY SF 2012. Cue-elicited affect and craving: Advancement of the conceptualization of craving in co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Behavior Modification, 36, 808–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETTINATI HM, O’BRIEN CP & DUNDON WD 2013. Current Status of Co-Occurring Mood and Substance Use Disorders: A New Therapeutic Target. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAUDENBUSH SW, BRYK AS, CHEONG YF & CONGDON R. 2017. HLM 7.03 for Windows [Computer software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- SAYETTE MA 1999. Does Drinking Reduce Stress? Alcohol Research and Health, 23, 250–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUCKIT MA 2009. Alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet, 373, 492–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENBANJO R, WOLFF K. & MARSHALL J. 2007. Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with reduced quality of life among methadone patients. Addiction, 102, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHER KJ 1987. Stress Response Dampening In: BLANE HT & LEONARD KE (eds.) Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- SHER L, STANLEY BH, HARKAVY-FRIEDMAN JM, CARBALLO JJ, ARENDT M, BRENT DA, SPERLING D, LIZARDI D, MANN JJ & OQUENDO MA 2008. Depressed Patients With Co-Occurring Alcohol Use Disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLADE T, MCEVOY PM, CHAPMAN C, GROVE R. & TEESSON M. 2013. Onset and temporal sequencing of lifetime anxiety, mood and substance use disorders in the general population. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24, 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOBELL LC, BROWN JM, LEO GI & SOBELL MB 1996. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 42, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOBELL LC & SOBELL MB 1992. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption In: ALLEN J. & LITTEN R. (eds.) Measuring alcohol consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- SOLOMON RL 1980. The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: The costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. American Psychologist, 35, 691–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRAKOWSKI SM & DELBELLO MP 2000. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clinical psychology review, 20, 191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN LE, FIELLIN DA & O’CONNOR PG 2005. The prevalence and impact of alcohol problems in major depression: A systematic review. The American Journal of Medicine, 118, 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWENDSEN J, CONWAY KP, DEGENHARDT L, GLANTZ M, JIN R, MERIKANGAS KR, SAMPSON N. & KESSLER RC 2010. Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction, 105, 1117–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIFFANY ST 2010. Drug craving and affect In: KASSEL JD (ed.) Substance abuse and emotion. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- TRULL TJ, SHER KJ, MINKS-BROWN C, DURBIN J. & BURR R. 2000. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical psychology review, 20, 235–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOLLEBERGH WM, IEDEMA J, BIJL RV, DE GRAAF R, SMIT F. & ORMEL J. 2001. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The nemesis study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAMPOLD BE 2015. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14, 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLINGER U, LENZINGER E, HORNIK K, FISCHER G, SCHÖNBECK G, ASCHAUER HN & MESZAROS K. 2002. Anxiety as a predictor of relapse in detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37, 609–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITKIEWITZ K, FINNEY JW, HARRIS AH, KIVLAHAN DR & KRANZLER HR 2015. Recommendations for the Design and Analysis of Treatment Trials for Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 39, 1557–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITKIEWITZ K. & TUCKER JA 2020. Abstinence Not Required: Expanding the Definition of Recovery from Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44, 36–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITKIEWITZ K. & WU J. 2010. Emotions and Relapse in Substance Use: Evidence for a Complex Interaction Among Psychological, Social, and Biological Processes In: KASSEL JD (ed.) Substance Abuse and Emotion. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMANN P, WITTCHEN HU, HÖFLER M, PFISTER H, KESSLER RC & LIEB R. 2003. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: a 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine, 33, 1211–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]