SUMMARY

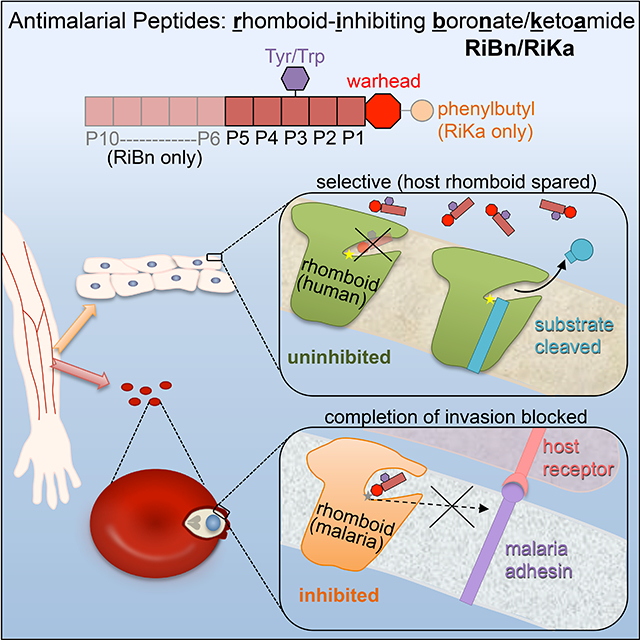

Rhomboid intramembrane proteases regulate patho-physiological processes, but their targeting in a disease context has never been achieved. We decoded the atypical substrate specificity of malaria rhomboid PfROM4, but found, unexpectedly, that it results from ‘steric exclusion’: PfROM4 and canonical rhomboid proteases cannot cleave each other’s substrates due to reciprocal juxtamembrane steric clashes. Instead, we engineered an optimal sequence that enhanced proteolysis >10-fold, and solved high-resolution structures to discover boronates enhance inhibition >100-fold. A peptide boronate modeled on our ‘super-substrate’ carrying one ‘steric-excluding’ residue inhibited PfROM4 but not human rhomboid proteolysis. We further screened a library to discover an orthogonal alpha-ketoamide that potently inhibited PfROM4 but not human rhomboid proteolysis. Despite the membrane-immersed target and rapid invasion, ultrastructural analysis revealed single-dosing blood-stage malaria cultures blocked host-cell invasion, and cleared parasitemia. These observations establish a strategy for designing parasite-selective rhomboid inhibitors, and expose a druggable dependence on rhomboid proteolysis in non-motile parasites.

eTOC Blurb

Gandhi et. al. combined substrate mapping, structural biology, and manually directed evolution to design potent peptidic inhibitors of the malaria rhomboid PfROM4 that do not target other rhomboid proteases. Treating malaria cultures revealed an essential role for PfROM4 only in invasion, and led to ‘tethered’ parasites that die out.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Intramembrane proteases are diverse enzymes that form a protease active site from their membrane-spanning segments within the plane of the membrane (Brown et al., 2000; Lemberg and Freeman, 2007; Sun et al., 2016; Wolfe, 2009). Although these ancient enzymes fall into four evolutionarily and chemically distinct families (Manolaridis et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2016; Wolfe, 2009), only the rhomboid and site-2 protease families are conserved in nearly all known bacterial, fungal, and protozoan pathogens (Kinch et al., 2006; Koonin et al., 2003; Urban, 2009). This broad distribution, coupled with multiple functions in pathogenesis by unrelated microbes, suggests understanding and ultimately inhibiting these enzymes could be a pan-antimicrobial strategy (Urban, 2009).

Although rhomboid proteases likely originated in bacteria (Koonin et al., 2003), the functions of these unusual serine proteases have been revealed predominantly in protozoan parasites (Baker et al., 2006; Baxt et al., 2008; Brossier et al., 2005; Deu, 2017; Lin et al., 2013; O’Donnell et al., 2006; Riestra et al., 2015). Early work identified adhesin molecules of apicomplexan parasites as probable substrates, including those from Plasmodium falciparum, the agent of malaria, and Toxoplasma gondii, a related parasite that infects nearly a third of the world’s population (Baker et al., 2006; Brossier et al., 2005). These obligate intracellular parasites must iteratively invade host cells, and rely upon an extensive arsenal of transmembrane adhesin molecules to attach to and invade cells (Sibley, 2011). Ultimately shedding adhesins from the parasite surface was postulated to be important for completing invasion (as reviewed in (Deu, 2017). Subsequent work has further broadened roles for rhomboid proteolysis to non-invasive, cytolytic parasites Entamoeba histolytica (Baxt et al., 2008; Rastew et al., 2015) and Trichomonas vaginalis (Riestra et al., 2015). Rhomboid cleavage of adhesins in these parasites is proposed to regulate parasite adherence, contact-dependent host-cell killing, and/or immune evasion, all of which are central to the virulence of these extracellular parasites.

Despite the promise that rhomboid proteases hold as therapeutic targets for treating diverse infectious diseases, three challenges have nearly quelled progress towards this goal. First, although the processes in which rhomboid enzymes participate are known to be essential, it remains unclear whether rhomboid proteolysis itself is indispensable in any parasite (Deu, 2017). Understanding the precise role played by the principal cell surface rhomboid, PfROM4, has been hindered by the inability to isolate malaria parasites lacking PfROM4 (Deu, 2017; Lin et al., 2013; O’Donnell et al., 2006), and by a lack of selective PfROM4 inhibitors. However, recent rhomboid knockouts in the related apicomplexan Toxoplasma gondii revealed surprisingly non-essential roles; absence of rhomboid cleavage led to elevated and non-polarized adhesin distribution on the parasite surface, but parasites nevertheless invaded successfully (Rugarabamu et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014). This first glimpse calls into question whether rhomboid proteases, even if successfully inhibited, are targets worthy of continued effort.

The second challenge is chemical: neither the rhomboid nor site-2 protease family has ever been successfully targeted pharmacologically in any pathological context despite over a decade of effort (Strisovsky, 2016; Wolf and Verhelst, 2016; Wolfe, 2009). The rapid nature of apicomplexan invasion, which can take only seconds (Dasgupta et al., 2014; Dvorak et al., 1975; Riglar et al., 2011), magnifies the challenge of whether there is even sufficient time to target rhomboid proteolysis sufficiently prior to parasites completing invasion and taking refuge in a host cell.

A third formidable complication is the conservation of rhomboid proteases in humans, and their emerging roles in important homeostatic processes like mitochondrial quality control (Saita et al., 2017). These functions necessitate developing parasite-selective (host-sparing) rhomboid inhibitors, yet no strategy has emerged for achieving such nuanced targeting.

Two unexpected observations present a conceivable path towards addressing all three challenges facing developing malaria rhomboid proteolysis into an anti-parasitic strategy. First, a subset of parasite rhomboid proteases, including PfROM4, have distinct substrate specificity relative to all other studied rhomboid proteases (Baker et al., 2006; Baxt et al., 2008; Riestra et al., 2015). If this subset of enzymes evolved to bind a distinct recognition sequence in adhesins (Strisovsky et al., 2009), in contrast to how other rhomboid enzymes target substrates (Dickey et al., 2013; Moin and Urban, 2012), this information could be exploited to design parasite-selective inhibitors. A second opportunity stems from the discovery of reversible chemical warheads that are dramatically more effective at blocking rhomboid proteolysis in the natural cell membrane of living cells and without preincubation (Cho et al., 2016; Ticha et al., 2017). Combining these emerging insights now raises the possibility of using a ‘conditional’ chemical genetic approach to evaluate the role PfROM4 plays in P. falciparum. We therefore started by focusing concerted effort on delineating the molecular basis of PfROM4’s atypical substrate specificity.

RESULTS

An exclusion mechanism underlies differential substrate selectivity of PfROM4

PfROM4 is able to process over a dozen malaria adhesins, but was the first active rhomboid protease found that could not cleave the canonical rhomboid substrate Drosophila Spitz (Baker et al., 2006). Conversely, metazoan rhomboid proteases cannot cleave malaria adhesins, implying that PfROM4 evolved distinct substrate specificity. In fact, P. falciparum contains at least one rhomboid protease, PfROM1, the specificity of which resembles Spitz-cleaving metazoan rhomboid proteases, and an adhesin, apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1), which is cleaved by canonical rhomboid proteases including PfROM1 but not by PfROM4 (Baker et al., 2006).

We focused on P. falciparum erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 (EBA175) and AMA1 to map the substrate requirements underlying PfROM4’s atypical substrate specificity, because these are the best-characterized malaria adhesins; they were the earliest to be identified (Camus and Hadley, 1985; Peterson et al., 1989), play critical roles (Duraisingh et al., 2003; Stubbs et al., 2005; Yap et al., 2014), had their crystal structures solved (Chesne-Seck et al., 2005; Tolia et al., 2005), and their cleavage sites have been mapped after being shed from parasites (Howell et al., 2005; O’Donnell et al., 2006). We examined rhomboid activity in a widely used cell-based assay by co-transfecting human HEK293T cells with GFP-tagged adhesin constructs and HA-tagged PfROM1 and PfROM4 (Baker et al., 2006).

AMA1 and EBA175 are large, type I transmembrane proteins of 622 and 1502 residues, respectively (Camus and Hadley, 1985; Peterson et al., 1989). To map the region of EBA175 responsible for targeting by PfROM4, we first created a chimeric AMA1 adhesin containing transmembrane and juxtamembrane residues from EBA175, with the junction being 5 residues N-terminal to their cleavage sites (termed P5 in protease nomenclature) (Schechter, 2005). Despite only having 40 residues from EBA175, this chimera converted AMA1 into a strong substrate for PfROM4 (Figure 1A). Conversely, a chimera that contained the extracellular region of EBA175 and the analogous juxtamembrane AMA1 residues (from P5 onwards) failed to be cleaved, yet one that contained AMA1 residues from P1 was cleaved efficiently, implying that PfROM4 recognizes EBA175 by the four residues P5 through P2. The same region also proved to be key for cleavage of the homologous adhesin BAEBL: mutating the P5-P2 sequence IPYF blocked PfROM4 cleavage, but it did not affect cleavage by two other parasitic rhomboid proteases (Figure S1A). Interestingly, PfROM1, which could not cleave wildtype BAEBL, acquired the ability to cleave the mutant form of BAEBL, further suggesting that its substrate specificity is reciprocal to that of PfROM4 (addressed further below).

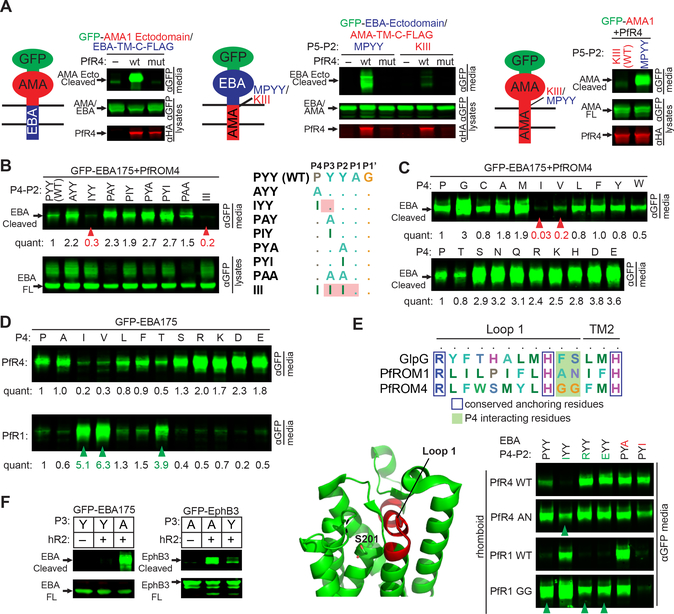

Figure 1. Differential substrate specificity of PfROM4 is mediated by steric exclusion not a new recognition sequence.

(A) Diagram of GFP-tagged (green) chimeras of EBA175 (blue) and AMA1 (red), with the membrane depicted as 2 horizontal lines (cytoplasm is down). Here and below, panels are western analyses of media and cell fractions from co-transfected HEK293T cells probed with the indicated antibodies. Also see Figure S1. Substrate cleavage releases products into media. ‘mut’ denotes the inactive PfROM4-H578A mutant. (B) Cleavage of GFP-EBA175 P4-P2 mutants by PfROM4 (quantification relative to wildtype appears below bands throughout). Arrowheads illustrate that a P4 isoleucine alone is sufficient to block processing to the same extent as a triple isoleucine stretch (that naturally occurs in AMA1). ‘FL’ denotes full-length substrate. (C) Processing of GFP-EBA175 harboring all 20 amino acids in the P4 position by PfROM4. Arrowheads denote substitutions that hindered PfROM4 cleavage. (D) P4 mutants of GFP-EBA175 that blocked PfROM4 cleavage activated cleavage by PfROM1. (E) Top, alignment of a short stretch of L1 loop residues between the universally conserved R and H residues (red region in structure, below left). Shaded in green are rhomboid residues that we found clash with P4 (but not P2) substrate residues. Right, processing of a panel of P4 (P, I, R, E in green) and P2 mutants (A, I in red) of GFP-EBA175 by wildtype or indicated L1 loop mutants of PfROM1 or PfROM4. Arrowheads denote substrates acquired by L1 loop mutants. (F) Processing of GFP-EBA175 and GFP-EphrinB3 by human RHBDL2. Presence of tyrosine at P3 of EBA175 (naturally) or Ephrin B3 (mutation) abrogated cleavage, while an alanine at the same position facilitated cleavage of both substrates. Results shown in B-E are representative of two or more biological replicates.

Accordingly, transplanting just the P5-P2 residues of EBA175 (MPYY) was sufficient to convert AMA1 into a strong PfROM4 substrate (Figure 1A). Reciprocally, mutating just the PYY residues (P4-P2) of EBA175 to III (P4-P2 of AMA1) completely abrogated EBA175 cleavage (Figure 1B). Finally, we tested single mutants of EBA175 and found that mutating just the P4 proline residue to isoleucine was sufficient to block EBA175 cleavage, while isoleucine or alanine substituted at either the P2 or P3 positions supported proteolysis (Figure 1B). These mapping experiments therefore highlighted the P4 proline of EBA175 as key for conferring cleavage by PfROM4.

To decipher the basis of this apparent molecular recognition, we installed each of the 20 naturally occurring amino acids at the P4 position of EBA175 and evaluated cleavage by PfROM4 (Figure 1C). Surprisingly, all but an isoleucine and valine supported cleavage, and many changes even enhanced EBA175 proteolysis. These changes included residues that were small and non-polar or polar (alanine, glycine, serine), large and hydrophobic (leucine, phenylalanine), positively charged (arginine, lysine), and negatively changed (aspartate, glutamate). The disparity in chemical characteristics and size suggested that, surprisingly, beta-branched residues are simply not tolerated at the P4 position, with the exception of threonine, which contains a hydrophilic hydroxyl instead of a hydrophobic methyl group that apparently significantly impacts its cleavage by PfROM4. All others were accommodated with ease or even preferred. This proved to be exactly reciprocal for conferring cleavage by PfROM1; only P4 mutants harboring beta-branched residues converted EBA175 into a PfROM1 substrate (Figure 1D). Finally, although neither AMA1 nor Spitz are substrates for PfROM4, a chimera with the extracellular region from AMA1 and remaining residues from Spitz (from its P5 residue onwards) was cleaved efficiently by PfROM4 (Figure S1B).

These experiments suggested that PfROM1 and 4 do not recognize separate sequences directly, but instead that they cannot cleave certain substrates because of residues that block cleavage. This model predicts that steric clashes with rhomboid explain the differences in substrate preferences. Although no structural information exists for malaria rhomboid enzymes, we could align PfROM4 and PfROM1 to Escherichia coli GlpG, whose high-resolution structure has been solved with bound substrate peptides (Cho et al., 2019; Cho et al., 2016; Zoll et al., 2014), in a short region of the L1 loop between two universally conserved residues, namely an arginine that supports L1 loop architecture and an oxyanion-stabilizing histidine near the start of transmembrane segment 2 (Figure 1E). This region of GIpG has been shown structurally to interact with the P4 residue of substrates (Cho et al., 2019; Cho et al., 2016; Zoll et al., 2014). We therefore mutated the corresponding A144 and N145 in PfROM1 to those that occur in PfROM4 (glycines), and found that the mutant PfROM1 gained the ability to cleave wildtype EBA175 with a P4 proline, or large and charged P4 residues (Figure 1E), while retaining its ability to process natural substrates. Reciprocally, mutating the corresponding glycines in PfROM4 to AN, as occur naturally in PfROM1, still allowed PfROM4 to cleave its natural substrates, but now also allowed it to cleave substrates with the previously non-tolerated beta-branched isoleucine in the P4 position (Figure 1E). The reduced selectivity was specific, because neither the PfROM1 nor the PfROM4 L1 loop mutants changed the ability or inability of either enzyme to process substrate mutants at the P2 position (Figure 1E).

We next examined whether similar steric clashes might explain why the human rhomboid RHBDL2 does not cleave EBA175, and discovered that its selectivity rests with the P3 residue (Figure 1F). Mutating the P3 tyrosine of EBA175 to alanine, which is the naturally occurring residue at the P3 position of the RHBDL2 substrate Ephrin B3, allowed RHBDL2 to cleave EBA175. Conversely, mutating just this alanine in Ephrin B3 to tyrosine inhibited RHBDL2 processing of Ephrin B3.

Taken together, these mapping and mutagenesis studies indicate that the mechanistic basis underlying the differential selectivity of PfROM4, PfROM1, and RHBDL2 for substrates is governed by negatively acting steric clashes that hinder cleavage, rather than presence of a unique, positively acting targeting sequence.

An alternative strategy: engineering a super-substrate by manually directed evolution

The steric exclusion mechanism that defines differential substrate specificity of PfROM4 made it non-obvious how to identify a sequence that we could use for inhibitor design. However, we previously discovered using a structural approach with E. coli GlpG that fostering ‘extra’ interactions in substrates at otherwise non-essential positions can enhance natural substrate processing (Cho et al., 2016; Ticha et al., 2017). In fact, we found a variant that increased substrate processing by a modest 2-fold actually increased peptide inhibitor potency by nearly 10-fold. We therefore focused on evolving an optimized targeting sequence for PfROM4 by engineering EBA175 mutations that enhanced natural substrate processing.

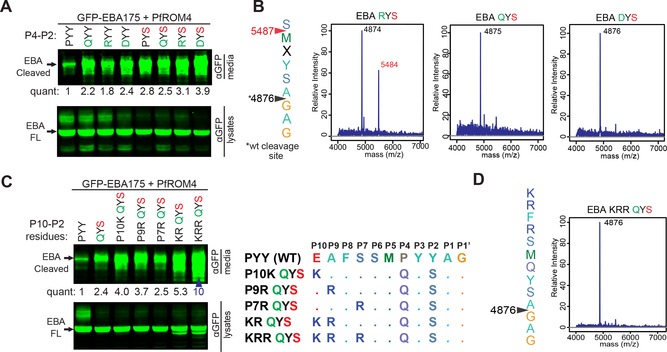

As a starting point, we subjected three diverse P4 mutants (Q, R, D) that enhanced processing of EBA175 to a second round of mutagenesis (while maintaining Y at P3 to avoid targeting RHBDL2), and isolated an additional serine substitution at the P2 residue that enhanced proteolysis further (Figure 2A). Although the presence of R at P4 shifted the cleavage site, the natural cleavage site was maintained in the enhanced Q and D P4 mutants (Figure 2B). We thus subjected these double mutant substrates to a third round of mutagenesis, and ultimately discovered that incorporating positively charged residues at the P7, P9 and P10 positions further enhanced processing (Figure 2C). The best quintuple mutant substrate that we engineered enhanced processing by >10-fold over wildtype EBA175, and fully maintained cleavage at the natural site (Figure 2D). This sequence was therefore a candidate for inhibitor design.

Figure 2. Engineering a ‘super-substrate’ for PfROM4 by manually guided evolution of EBA175.

(A) Western analysis revealed substituting a serine at the P2 position (in red) of GFP-EBA175 enhanced proteolysis of P4 R, D, and Q mutants (in green). Shown here and in C are western analyses of media and cell fractions from co-transfected HEK293T cells probed with the indicated antibodies. Substrate cleavage releases products into media. Quantification relative to wildtype appears below bands throughout. ‘FL’ denotes full-length GFP-EBA175. (B) Mass spectra of C-terminal proteolytic fragments immunoaffinity-isolated (anti-Flag) from HEK293T cells co-transfected with GFP-EBA175-Flag and PfROM4. Cleavage sites, based on experimentally measured molecular masses (in the spectra), are indicated by arrowheads (with corresponding predicted masses). Red arrowhead and mass correspond to a cleavage site shift. (C) Substituting K, R and R and P7, P9, and P10, respectively (diagram at right), enhanced PfROM4-catalyzed processing of the quintuple GFP-EBA175 mutant (red arrowhead). Note that PYY (first lane) is the natural P4–2 sequence. (D) Mass spectrum of the quintuple GFP-EBA175 mutant that was processed > 10-fold better by PfROM4 revealed cleavage occurred only at the natural site. Results of cleavage assays shown were reproduced in multiple independent biological experiments.

Peptide boronates are >100-fold more potent rhomboid inhibitors

Our next goal was to install a chemical warhead for PfROM4 inhibition. We previously discovered that, contrary to expectation, peptides bearing C-terminal aldehydes that act as covalent but reversible inhibitors are more effective at inhibiting E. coli rhomboid proteolysis than peptides harboring an irreversible chloromethylketone warhead (Cho et al., 2016). This has recently been observed with alpha-ketoamides, which are also covalent but reversible inhibitors of GlpG (Ticha et al., 2017). We therefore sought to test whether other reversible warheads might prove to be even more potent rhomboid inhibitors.

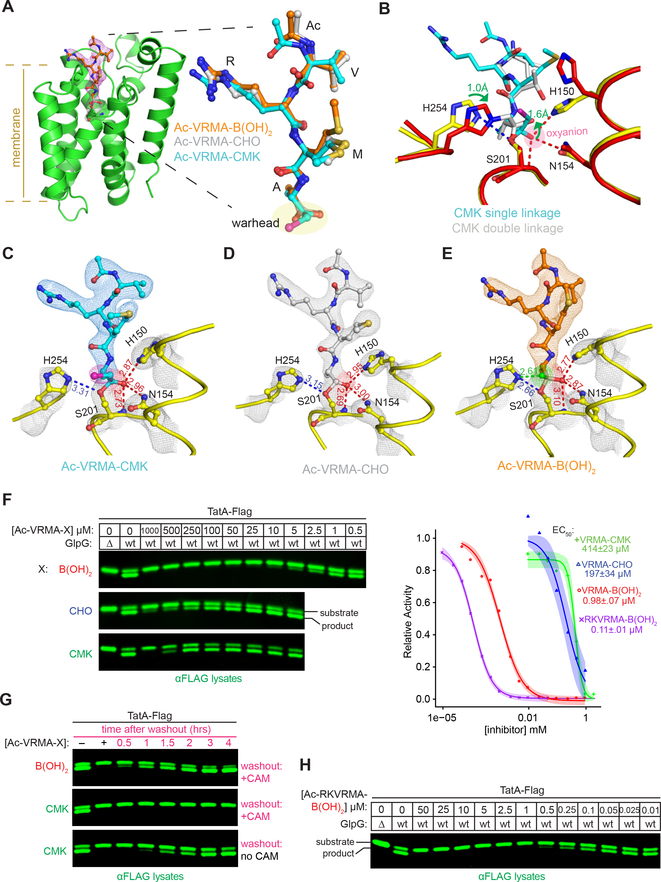

E. coli and P. falciparum rhomboid proteases are grossly dissimilar, sharing only ~9% sequence identity overall. However, the local constellation of residues performing catalysis in their active sites should be conserved, thereby potentially allowing structural analysis of GlpG to guide our attempt at PfROM4 inhibitor development. We therefore solved and compared the tetrahedral complex structures between E. coli GlpG and tetrapeptides harboring C-terminal chloromethylketone, aldehyde, or boronate warheads at 2.3A resolution (Supplemental Table S1).

In all cases, the position of the substrate peptide in the active site was similar, being dictated by the peptide sequence (Figure 3A). Interestingly, we were able to isolate the singly-linked tetrahedral complex with even the peptide chloromethylketone (Figure 3B,C), in contrast to the available structures that contain the doubly-linked covalent adduct (Zoll et al., 2014). A key difference is the oxyanion being dramatically pushed outwards by 1.64Å with the doubly-reacted chloromethylketone (Figure 3B), but clearly in the oxyanion hole with both the singly reacted peptide aldehyde (Cho et al., 2016) (Figure 3D) and chloromethylketone (Figure 3C). The boronate also adopted the ideal substrate position, but the second hydroxyl group of the boronate made an additional strong hydrogen bond to the catalytic H254 base of GlpG at a distance of 2.61Å (Figure 3E). In fact, H254 moved closer to the substrate as a whole. This was an encouraging observation, because such a strong, extra hydrogen bond could result in inhibitors of considerably higher affinity.

Figure 3. Atomic structures of E. coli rhomboid GlpG in catalytic complex with peptide inhibitors.

(A) Structure of GlpG (left, in green ribbon) in catalytic complex with Ac-VRMA-B(OH)2 (electron density map 2Fo-Fc at 2σ is in red mesh). In all cases electron density is continuous between the catalytic serine S201 and the inhibitors, indicating that catalysis had taken place. Right, ball-and-stick overlay of all three inhibiting Ac-VRMA peptides with different warheads reveals that all adopted nearly indistinguishable conformations in the GlpG active site. (B) Active site comparison of the CMK singly reacted with the catalytic serine S201 (in yellow/cyan), versus CMK doubly reacted with the catalytic serine S201 and histidine H254 (PDB = 4QO2 in red/grey). Note the dramatic shifts in position (denoted by green arrows) of the substrate oxyanion, which has left the oxyanion hole, and catalytic base (H254). (C-E) Atomic structures of tetrapeptide inhibitors in the active site of GlpG. The experimental electron density maps (2Fo-Fc at 2σ) are shown in grey mesh for the catalytic residues, and blue mesh for the Ac-VRMA-CMK in C (chlorine in pink), grey mesh for Ac-VRMA-CHO (PDB = 5F5B) in D and orange mesh for Ac-VRMA-B(OH)2 in E. Distances are in Å, oxyanion-stabilizing interactions are in red, and the extra hydrogen bond between catalytic H254 and the second hydroxyl of the boronate is highlighted in green. (F) Inhibition of endogenous GlpG activity in E. coli liquid cultures (Δ denotes the genomic GlpG deletion) by indicated concentrations of peptide inhibitors. Shown are quantitative infrared anti-Flag westerns of TatA-Flag uncut substrate and cut product. Quantification of cleavage was used to calculate the EC50 concentrations (graph on right, mean ± s.e.m.). (G) Inhibition of endogenous GlpG in living E. coli cells was performed as above, and after two hours, cells were spun, media containing inhibitor removed, cells were resuspended in media containing chloramphenicol, and grown for the indicated times. (H) Potency of the hexapeptide boronate Ac-RKVRMA-B(OH)2 was assessed against endogenous GlpG in living E coli cells as described in F. Data shown in F-H are representative of two or more biological replicates.

We next tested the effect of the boronate on the inhibition of GlpG in living E. coli cells (Figure 3F). Remarkably, just the presence of the boronate moiety itself increased potency of the same tetrapeptide by >400-fold relative to the chloromethylketone, and >100-fold relative to the aldehyde, in a direct, side-by-side comparison. Inhibition of GlpG in living E. coli cells was fully reversible, since washing out the inhibitor (while blocking new GlpG synthesis with chloramphenicol) resulted in recovery of protease activity with the boronate but not with the irreversible chloromethylketone (Figure 3G). Finally, extending the boronate by two residues increased potency by another ~10-fold (to a nanomolar EC50), suggesting that longer peptide boronates might provide an excellent warhead for PfROM4 inhibition (Figure 3H).

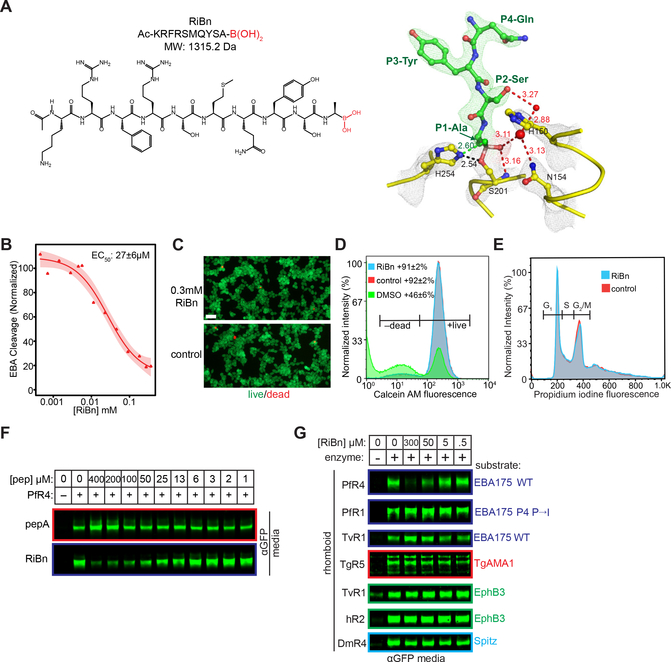

Parasite-selective rhomboid inhibition by a designed peptide boronate

We combined our >10-fold enhanced EBA175 substrate sequence with a C-terminal boronate warhead to engineer a rhomboid-inhibiting boronate, or RiBn (pronounced ‘ribbon’), as a candidate compound for the selective inhibition of PfROM4 (Figure 4A). We also solved the co-crystal structure of RiBn reacted with GlpG to 2.3 Å resolution as a quality control for inhibitor reactivity, mechanism, and purity (Figure 4A). Treating transfected HEK293T cells with RiBn inhibited EBA175 processing by PfROM4 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4B), and had no effect on cell viability or function (Figure 4C–E). In fact, even at the highest concentrations, a fluorescence-based live/dead cell assay revealed no change in cell viability (Figure 4C). We further used flow cytometry to quantify cell viability, and found 90% viability in cells treated with the highest dose of RiBn, relative to 91% in untreated controls and 51% of elevated DMSO-treated cells analyzed in parallel (Figure 4D). Moreover, flow cytometry also revealed no apparent change in the adherence, growth, or cell cycle distribution of treated versus untreated cells (Figure 4E), further highlighting the specificity of the designed RiBn. Finally, changing the warhead from a boronate to an aldehyde abrogated PfROM4 inhibition (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. RiBn is a non-toxic, selective inhibitor of only PfROM4.

(A) Chemical structure of RiBn (left). Ac denotes an N-terminal acetyl moiety, while the C-terminal boronate warhead is in red. Atomic structure (right) of RiBn in catalytic complex with GlpG at 2.3 Å resolution (overlying L5 loop residues have been removed for visual clarity). The experimental electron density maps (2Fo-Fc at 2σ) are shown in grey mesh for the catalytic residues and green mesh for the P4-P1 residues (QYSA) of RiBn. Shown are water molecules (red spheres), oxyanion-stabilizing interactions (red dashed lines), and the extra hydrogen bond between the catalytic histidine H254 and the second hydroxyl of the boronate (green dashed line). Distances are in Å. (B) Quantification of PfROM4 inhibition by RiBn (mean ± s.e.m. from three independent biological replicates, shading represents the 95% confidence interval). (C) Fluorescence microscopy of HEK293T cells growing in the presence/absence of RiBn, assayed for calcein AM green fluorescence (marking live cells) and ethidium homodimer-1 red fluorescence (marking dead cells). Scale bar is 10μm. (D) HEK293T cells cultured in the presence/absence of RiBn or 5% DMSO (toxicity control) for ~24 hours were quantified for calcein AM fluorescence (mean ± s.d. for two biological replicates) using flow cytometry. (E) Cell cycle analysis of HEK293T cells cultured in the presence/absence of RiBn for 24 hours was conducted by flow cytometry (propidium iodine fluorescence). Populations of cells in G1, S, and G2/M are indicated with gates. (F) Western analysis of EBA175 cleavage (anti-GFP, conditioned media) by PfROM4 in co-transfected HEK293T cells in the presence/absence of the peptide-aldehyde (top panel) or peptide-boronate (bottom panel). (G) Western analysis (anti-GFP, conditioned media) of RiBn inhibition of all known cell surface rhomboid enzymes and their substrates.

More exciting was the fact that RiBn had no inhibitory effect on any of the other five rhomboid proteases known to reside on the cell surface, including the human rhomboid enzyme, analyzed in parallel in the same assay (Figure 4G). In fact, even PfROM1, which is also a P. falciparum rhomboid but with distinct substrate specificity (Baker et al., 2006), proved completely unaffected even at the highest concentration of RiBn. Under all of these conditions, cells translated, glycosylated, trafficked, and secreted unrelated proteins indistinguishably from cells treated with the highest concentrations of RiBn, further corroborating no apparent effect on cell function (Figure 4G). These observations indicate that we succeeded in designing the first PfROM4-selective inhibitor that has no discernible effect on other rhomboid enzymes, or on cell viability or function.

PfROM4 inhibition blocks host-cell invasion by malaria parasites

Although several different species of Plasmodium naturally infect humans, P. falciparum causes the key lethal form of malaria worldwide (Murray et al., 2012). We thus adapted a high-resolution flow cytometry-based assay (Klonis et al., 2011) and validated it with the known anti-malarial chloroquine (Figure 5A) to evaluate the effect of RiBn on P. falciparum merozoites iteratively growing on human red blood cells. This constitutes the symptomatic and persistent stage of the parasite lifecycle, and thus the desired window for therapeutic intervention.

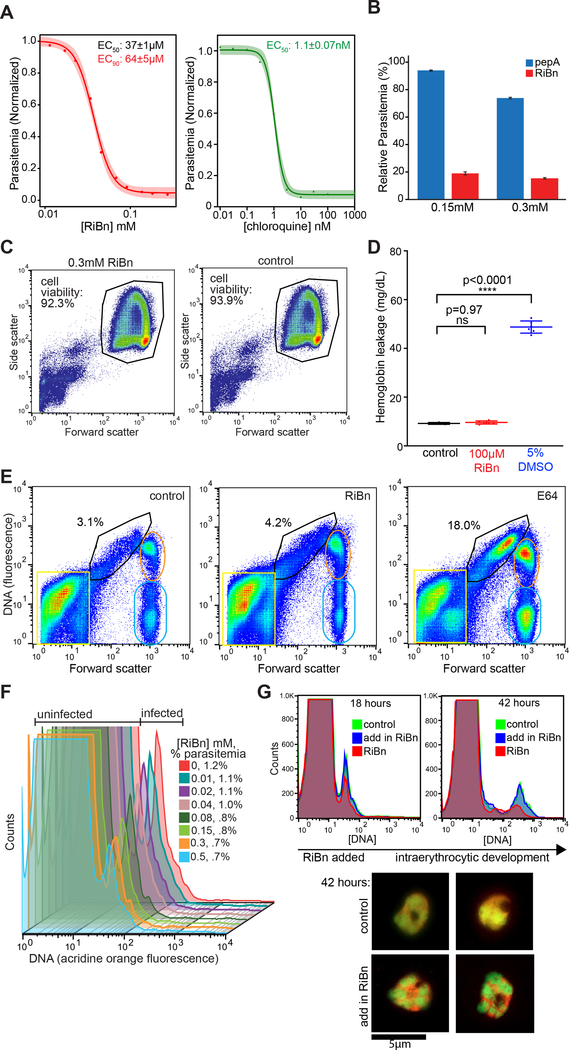

Figure 5. RiBn inhibits P. falciparum malaria growth on human erythrocytes.

(A) Quantification of parasite growth inhibition by RiBn (mean ± s.e.m.). Parasitemia was determined by flow cytometry (using acridine orange staining) of parasitized erythrocytes cultured in the presence of indicated concentrations of RiBn or chloroquine. Dose response curves are representative of five independent biological replicates for RiBn and two for chloroquine. (B) Quantification of parasitemia in parasitized erythrocytes cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of pepA (peptide-aldehyde, blue) or RiBn (red) for ~80 hours graphed as mean ± s.d. from two biological replicates. (C) Flow cytometry analysis (Forward Scatter vs Side Scatter) of erythrocytes cultured in the presence/absence of RiBn for ~18 hours. (D) Cytotoxicity of erythrocytes in the absence (control) or presence of RiBn or DMSO assessed by hemoglobin leak into culture media. Data are mean ± s.d. assessed by ordinary one-way ANOVA relative to control, n=6. (E) Flow cytometry of parasite egress is depicted. Heparin synchronized, magnetically purified schizont stage parasites were untreated (control) or treated with 10μM E-64, or 300μM RiBn, and monitored for stalled egress 8-hours post-treatment by flow cytometry analysis with acridine orange staining (DNA vs forward scatter shown). Percent of erythrocytes with stalled late-stage schizonts typical of E64 treatment (Wilson et al., 2013) are quantified in the gate (black). Populations of free merozoites and erythrocyte debris (yellow square), schizonts (orange oval) and uninfected or partially infected erythrocytes (green oval) are indicated. Results shown are representative of two independent biological replicates. (F) Blood cultures of synchronized schizont-stage parasites were treated with the indicated concentrations of RiBn for ~24 hours and probed for the presence of ring stage parasites by flow cytometry of parasitized (DNA+) and uninfected (DNA−) erythrocytes. Reduced parasitemia in RiBn-treated cultures was reproducible in three independent biological replicates with p<0.0001 (see Figure S2). (G) RiBn (0.3mM) was added to schizont-purified cultures after parasites were allowed to invade (18 hours, blue), and compared to those either treated with RiBn during invasion (red) or untreated control (green). The compound had no discernable effect on growth (flow cytometry, right panel) or parasite morphology (acridine orange stained fluorescent images, bottom panels) at 42-hours.

Treating malaria cultures with RiBn resulted in dose-dependent inhibition of parasite growth (Figure 5A). Substitution of the boronate with an aldehyde abolished inhibition (Figure 5B), and toxicity analysis with red blood cells again verified that the compound was not affecting host cell viability (Figure 5C, D). We next sought to characterize the basis of the inhibition.

Parasite egress from infected red blood cells is an intricate process that requires the action of multiple proteases and can be quite sensitive to indirect perturbations (Blackman and Carruthers, 2013; Deu, 2017; Yeoh et al., 2007). Therefore, to examine whether RiBn was inhibiting egress, we treated highly synchronized schizonts with RiBn and monitored egress using a sensitive and high-throughput flow cytometry assay that was developed for monitoring schizont rupture (Wilson et al., 2013). This analysis revealed the efficiency of egress to be unaffected (Figure 5E). Conversely, treating synchronized schizont-stage cultures with RiBn revealed a dose-dependent decrease in ring-stage parasites after 24 hours (Figure 5F) that was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy and was both highly reproducible and statistically significant (p<0.0001, Figure S2). Accordingly, RiBn had no effect on parasite growth if it was administered after invasion was complete (Figure 5G). Therefore, since RiBn was affecting only the invasive step of the merozoite lifecycle, we next sought to determine how.

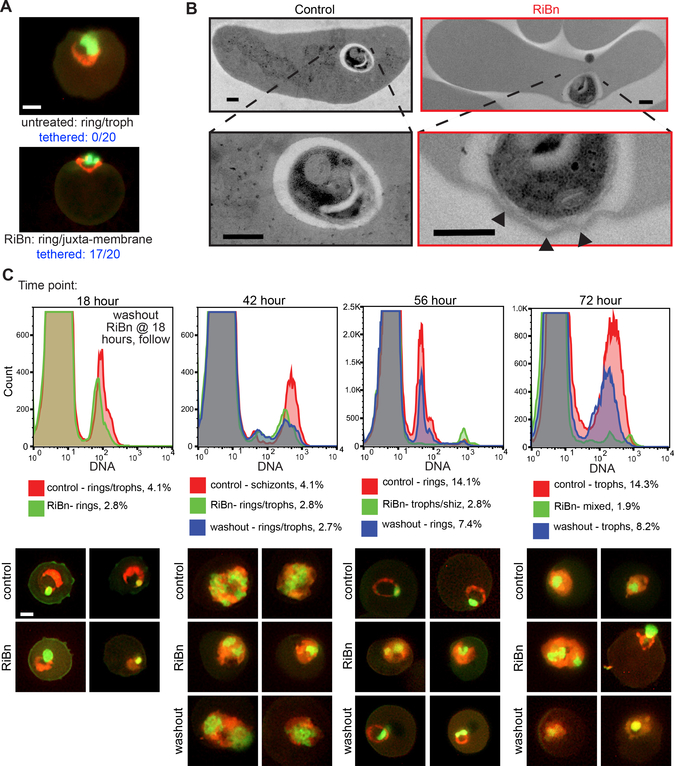

Interestingly, we noticed that, even at the highest dose of RiBn, some merozoites were able to invade. We examined these parasites by fluorescence microscopy and found that they appeared ‘stuck’ to the inner cell periphery (Figure 6A, p<0.0001), implying they could not free themselves from the plasma membrane. To examine this phenotype in greater detail, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on RiBn-treated versus untreated controls in parallel, and indeed found merozoites were attached to the erythrocyte membrane and in many cases induced severe membrane convolutions (Figure 6B, Figure S3A). Subsequent time points revealed that these treated parasites grew slower than untreated controls (Figure S3B). Ultimately the delayed parasites progressed through all of the lifecycle stages and released merozoites from schizonts (Figure 6C), again indicating that other parasite stages including egress itself were not affected by RiBn. In fact, washing out RiBn after the first round of invasion rescued parasite growth, which became evident in the second round of invasion (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. RiBn inhibits P. falciparum merozoite invasion of red blood cells.

(A) Fluorescence microscopy images of acridine orange stained parasitized erythrocytes (Green=DNA, Red=RNA) cultured in the absence or presence of RiBn for ~24 hours. Scale bar is 1μm. Images are representative of 20 each untreated and treated cells, with peripherally localized parasites observed in 0/20 untreated cells and 17/20 RiBn treated cells (p<0.0001). (B) TEM images of erythrocytes fixed 2 min after invasion by merozoites in the absence or presence of RiBn. Scale bars are 0.5μm and higher magnifications are shown below. Arrows denote membrane convolutions (also see Figure S3A). (C) Blood-stage cultures containing 1% well synchronized schizont stage parasitized erythrocytes were cultured in the presence (green histograms) or absence (red histograms) of 0.3mM RiBn and analyzed at various time points via flow cytometry (acridine orange, top panels, also see Figure S3B) and fluorescence microscopy (acridine orange staining, bottom panels, scale bar = 1μm). After 18 hours of culturing, RiBn was washed out of one replicate of the RiBn treated cultures and monitored as above (blue histograms).

Discovery of an orthogonal pharmacophore that potently inhibits PfROM4 and blocks invasion

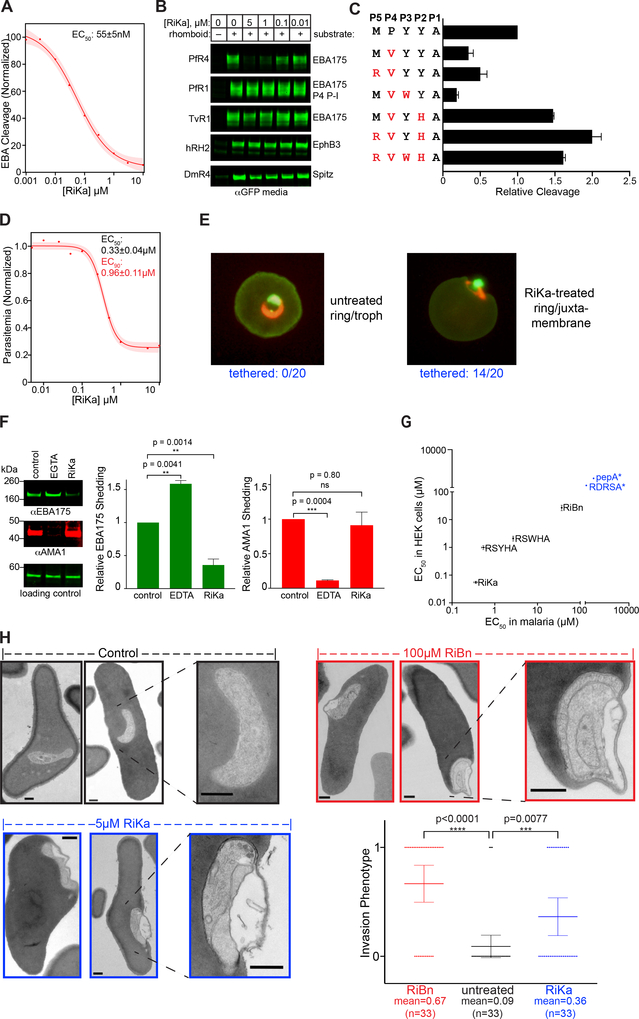

Despite the exciting results that we obtained with RiBn, its low potency necessitated using high concentrations that can raise concerns of potential off-target effects. During the course of our studies, a new class of potent rhomboid inhibitors were reported that incorporate an alpha-ketoamide warhead at the C-terminus of short peptides (Ticha et al., 2017). These compounds bind rhomboid in a similar way to peptide boronates by forming additional hydrogen bonds within the catalytic apparatus, but, additionally, extend interactions into the prime side of the rhomboid active site via their hydrophobic substituents at the amide nitrogen. We thus installed an alpha-ketoamide onto the last five residues of our optimal sequence, but the resulting compound proved to be of low potency. We next screened a mini library of peptide alpha-ketoamides of varying sequence and C-terminal extensions and fortuitously discovered a rhomboid-inhibiting ketoamide (RiKa), Ac-RVWHA-CONH-phenylbutyl (Figure S4A), that inhibited PfROM4 expressed in heterologous cells with an EC50 of 55±5 nM (Figure 7A). This is greater than two orders of magnitude more potent than our RiBn. We also solved the structure of RiKa with GlpG to 2.4 Å resolution, which revealed the expected inhibition mechanism (Figure S4A). Importantly, RiKa also did not cause any adverse cytotoxic effects on human HEK293T cells (Figure S4B), and did not inhibit other rhomboid proteases (Figure 7B). As such, we successfully identified a second, potent yet orthogonal PfROM4-selective inhibitor with a different peptide sequence and chemical warhead.

Figure 7. RiKa Potently Inhibits PfROM4 and blocks merozoite invasion.

(A) Dose response curve for RiKa-mediated inhibition of EBA175 cleavage by PfROM4 in HEK293T cells (also see Figure S4). The EC50 is the mean ± s.d. from two independent biological replicates (shading denotes 95% confidence interval). (B) Anti-GFP western blots of HEK293T cell media samples showing effect of RiKa on cleavage of indicated substrates by a panel of rhomboid proteases. (C) PfROM4-mediated cleavage in HEK293T cells of EBA175 variants with the indicated amino acid substitutions (in red) at P1 to P5 subsite positions was compared. Graphed are the mean ± s.d. from two biological replicates. (D) Malaria growth inhibition curve of parasitemia measured by flow cytometry of cultures that were treated with RiKa for 72h (also see Figure S5). Mean EC50 and EC90 values ± s.e.m were calculated from two technical replicates and are representative of three independent experiments). (E) Fluorescence microscopy images of parasitized erythrocytes cultured in the absence/presence of 5μM RiKa for ~24h and stained with acridine orange. Scale bar is 1μm. Representative images are shown, and peripheral parasite localization was observed in 0/20 untreated and 14/20 RiKa-treated cells (p<0.0001). Also see Figure S6. (F) Western blot analysis of adhesin shedding from free merozoites. Cleaved EBA175 and AMA1 were detected in supernatants from merozoites incubated with DMSO (control), 25mM EGTA, or 10μM RiKa. A non-specific band detected by anti-EBA175 is shown as a control for equivalent loading (lower panel). Graphed data (right panels) are mean ± s.d. from two biological replicates assessed for statistical significance using ordinary one-way ANOVA relative to control. (G) Rank order of potency of 6 designed anti-PfROM4 inhibitors in HEK293T cells transfected with PfROM4 compared to wildtype 3D7 merozoites growing on human red blood cells. Data in blue are only estimates since these loss-of-function variants failed to produce reliable inhibition curves. (H) TEM images of erythrocytes fixed 10 min after invasion by free merozoites in the absence/presence of inhibitors. Scale bar is 0.5pm and higher magnifications are on the right. Bottom right, column scatter plot of 99 randomized images scored blind (randomized at www.randomlists.com/random-numbers) for the absence (0) or presence (1) of the invasion phenotype.

One seemingly contradictory property of RiKa is a valine at the P4 position, which we previously found to be disallowed in PfROM4 substrates. To discern the basis of this apparent contradiction, we first introduced the RVWHA sequence into our EBA175 substrate construct, and indeed found this sequence increased substrate processing by ~1.5-fold (Figure 7C). Interestingly, when we incorporated residues in various combinations, we discovered that the P4 valine was indeed disallowed. However, a valine at P4 and histidine at P2 together strongly enhanced substrate processing to a level comparable to what we observed in the pentapeptide sequence. These observations suggest that the potency of RVWHA results from subsite cooperativity between the P2 and P4 positions.

Encouraged by its potency and selectivity, we next examined the effect of RiKa on malaria cultures. Consistent with our RiBn results, RiKa inhibited malaria culture growth, but with a ~100-fold more potent EC50 of 330±40 nM (Figure 7D). As with RiBn, the parasites that did manage to invade were often tethered to the inner surface of the red blood cell membrane (Figure 7E, p<0.0001). Again, RiKa exhibited no cytotoxic effects on erythrocytes (Figure S4C), and no effects on parasite growth or egress were apparent when we added RiKa after invasion had already taken place (Figure S5). Moreover, RiKa elicited dose-dependent inhibition of erythrocyte invasion directly by isolated merozoites and with a 3-fold lower EC50 value than when administered at the schizont stage, which was independent evidence that it does not exert its effect by inhibiting egress (Figure S6A). Furthermore, RiKa inhibited (p=0.0014) the shedding of EBA175 by PfROM4 from live, invasion-competent free merozoites while having no effect (p=0.80) on concurrent shedding of AMA1 by PfSUB2 (Figure 7F). Conversely, blocking AMA1 shedding by PfSUB2 did not inhibit cleavage of EBA175 by PfROM4.

Finally, we performed a rank order of potency analysis in order to validate the link between PfROM4 inhibition and the effect on parasite growth. Comparing RiBn and RiKa with four other peptide-warhead inhibitors, namely Ac-KRFRSMQYSA-CHO, Ac-RSYHA-CONH-phenylbutyl, Ac-RSWHA-CONH-phenylbutyl, and Ac-RDRSA-CONH-phenylbutyl, revealed the same order of potency for inhibition of PfROM4 activity in HEK293T cells and parasite blood-stage growth (Figure 7G). Taken together, these observations confirmed that the inhibitory effect stemmed from targeting PfROM4, and a specific effect directly and only on invasion.

Ultrastructural basis of the invasion defect resulting from PfROM4 inhibition

Since both RiBn and RiKa led to an invasion defect, we further characterized and quantified the ultrastructure of the invading merozoites by TEM directly in parallel. At late stages when invasion was already complete in untreated controls, both RiKa-treated and RiBn-treated merozoites continued to be attached to the red cell plasma membrane, and again often displayed severe contortions of the erythrocyte plasma membrane (Figure 7H). Blind scoring of infected parasites revealed that this phenotype was highly significant both in RiBn- and RiKa-treated parasites (p<0.0001 and <0.0077, respectively). This is consistent with PfROM4 proteolysis being required to dismantle the moving junction in order for parasites to untether themselves from the host-cell plasma membrane and fully gain entry for subsequent replication within the parasitophorous vacuole.

Single dose inhibition of PfROM4 clears red blood cell cultures of parasitemia

We finally examined the effect of prolonged culturing of parasites in the presence of RiKa or RiBn, as would be expected in a therapeutic setting. Remarkably, single application of either RiKa or RiBn had an even stronger effect on the second and subsequent rounds of invasion (Figure S6B), such that red blood cell cultures could be cleared of parasitemia by RiBn (which is more stable than RiKa) within 2 to 3 invasive cycles without applying any additional compound (Figure S6C). These observations reveal an essential role for PfROM4 in host-cell invasion, and suggest that targeting its enzymatic activity selectively is both chemically feasible and potentially curative.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have combined substrate profiling in living cells, manually directed evolution, X-ray crystallography, and parasitology to design and evaluate parasite-selective rhomboid proteolysis inhibitors. Subsequent chemical genetic dissection of P. falciparum infection revealed a clear, essential, and druggable role for PfROM4 in the invasion of human red blood cells. After nearly a decade of stalled progress (Deu, 2017), this success sheds mechanistic light on the invasion process, how rhomboid enzymes operate biochemically, and how to target them selectively.

Precisely why adhesins are shed from the surface of invading parasites has been a long-standing mystery. Studies in different parasites have identified roles in removing exposed epitopes from the parasite surface as an immune evasion strategy. In fact, even just slowing merozoite invasion led to enhanced antibody neutralization of malaria parasites (Alanine et al., 2019). A recent study further discovered that shed adhesins themselves are able to cluster uninfected red blood cells around an infected cell to protect merozoites from the immune system, and subsequently to provide nearby uninfected cells for efficient daughter parasite invasion (Paing et al., 2018). In contrast, our results reveal that, at least for malaria merozoites, the primary function of adhesin shedding is to facilitate resolution of the invasion process, because without it merozoites fail to invade productively.

While this function is compatible with additional roles in immune evasion, it is in clear contrast to Toxoplasma tachyzoites, which invade unimpeded without adhesin shedding (if they are able to establish apical contact with the host cell) (Shen et al., 2014). One likely explanation is that tachyzoites use ‘twisting motility’ to resolve invasion contacts physically from the host cell surface (Pavlou et al., 2018), and leave behind a separated punctum of uncleaved adhesins in the absence of rhomboid activity (Rugarabamu et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014). Conversely, P. falciparum merozoites are contractile cells, but in contrast to sporozoites, are incapable of gliding motility, and may have thus come to rely on enzyme-mediated resolution. This would suggest that targeting rhomboid proteases in parasites not capable of gliding motility would be a particularly effective strategy for therapeutic intervention. But in both gliding and non-gliding parasites, interfering with adhesin shedding in immune evasion would additionally aid in parasite clearance, which might even be synergistic in combination with recent vaccine strategies.

Biochemically, we sought to understand the nature of PfROM4-adhesin recognition, because PfROM4 presented the best candidate for a rhomboid that might have evolved dependence on a selective substrate recognition sequence. Instead, we discovered the opposite: even at decisive substrate positions like P4, positively charged, negatively charged, large, and small residues could all be accommodated with ease (only hydrophobic beta-branched residues were excluded). Second, as we first visualized through structural analysis (Cho et al., 2016), it was possible to create new enzyme-substrate interactions that enhance proteolysis. The fact that these interactions are readily possible but don’t occur naturally in substrates further underscores that, while rhomboid proteases display sequence preferences around the cleavage site, natural substrates may not be optimized in this regard, and substrate specificity is conferred primarily by helix instability (Moin and Urban, 2012). Furthermore, sequence preferences around the cleavage site might not be easy to map using single point mutations, because we found rhomboid subsites may show cooperativity. Finally, when we attempted switching substrate specificity by making reciprocal mutants between two different rhomboid enzymes, we only obtained two degenerate enzymes with the ability to cleave a wider panel of substrates. Understanding these counterintuitive properties ultimately allowed us to tailor a parasite rhomboid-selective inhibitor that carries a P3 clashing group with the human rhomboid protease, but fosters new binding affinity interactions with PfROM4 that are essential for targeting by small molecules. This holistic strategy now raises two key opportunities.

The first opportunity stems from blood-stage cultures being cleared of malaria with just a single dose of RiBn and without any apparent indirect effects. Indeed, evidence that we achieved selective PfROM4 targeting is already very encouraging. First, neither inhibitor exhibited any discernible effects on either human cells or other rhomboid proteases. Second, the effect on parasites was limited to invasion, and not the intricate egress or developmental growth phases that follow for 48 hours and are often perturbed by non-specific compounds. Third, the phenotype, as revealed by ultrastructural analysis, is uncommon and specific: a failure of parasites to untether themselves from the erythrocyte plasma membrane, which is an adhesion defect. Finally, two orthogonal compounds of unrelated peptide targeting sequence and warhead chemistries exhibited indistinguishable effects on malaria parasites, while altering either peptide sequence or the warhead to an aldehyde abolished inhibition. Since all six compounds directly affect PfROM4 in a heterologous assay with the same rank order of potency as in parasites (Figure 7F), the effect on parasites is overwhelmingly likely to result from PfROM4 inhibition.

This encouraging observation with model compounds now compels initiating development of selective anti-PfROM4 molecules with drug-like properties after the decade-long gap since rhomboid proteases were identified as adhesin-processing enzymes (Baker et al., 2006; O’Donnell et al., 2006). Even partial PfROM4 inhibition may be curative with the aid of an immune system that would be enhanced in its ability to attack partly exposed parasites that failed to complete invasion and/or free parasites displaying accumulated cell-surface antigens (Rugarabamu et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014). Nevertheless, even with promising early results, peptide-based compounds ultimately have too many pharmacological demerits to be fully effective in clinical settings (Craik et al., 2013).

Second and more broadly, many rhomboid proteases are thought to be involved in a diversity of parasitic diseases for which treatments are rudimentary or even ineffective, but their importance and/or targetability remain speculative. These include trichomoniasis, the most common non-viral sexually-transmitted disease (Riestra et al., 2015), and non-viral dysentery (Baxt et al., 2008), which has recently surpassed malaria as a leading cause of childhood death worldwide (Striepen, 2013). Transfection-based assays have already been established for these and many other parasitic rhomboid enzymes (Baker et al., 2006; Baxt et al., 2008; Brossier et al., 2005; Howell et al., 2005; O’Donnell et al., 2006; Riestra et al., 2015). Coupled with our approach described here, this core set of standardized assays should allow engineering selective RiBns and/or RiKas to start realizing the much-anticipated therapeutic promise of rhomboid proteases.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Sinisa Urban (rhomboidprotease@gmail.com).

Materials Availability

Custom inhibitors used in this study were consumed by experiments, and can be resynthesized commercially using commercially available precursors (for details, contact corresponding author).

Data and Code Availability

Structure coordinates have been deposited into the Protein Databank under the accession codes 6VJ8, 6VJ9, 6XRO, and 6XRP.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

P. falciparum Culture

Asexual P. falciparum 3d7 parasites (kind gift of Dr David Sullivan, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health) were cultured under standard conditions (Trager and Jensen, 1976) in human erythrocytes (O-donor, purchased from Interstate Blood Bank, Inc.) at 5% hematocrit in media consisting of RPMI 1640 with glutamine XL (Quality Biological) supplemented with 20mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1mM hypoxanthine, 20μg/mL gentamicin, and 0.5% Albumax II and in a gas mixture of 90%N2/5%O2/5%CO2 at 37°C. Sorbitol synchronization was performed by treating early ring stage parasites (16–24h post invasion) with 5% sorbitol for 10 minutes approximately once per week or as needed for experiments.

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmid Construction

All open reading frames were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) as N-terminal GFP-tagged/C-terminal Flag-tagged substrates or N-terminal 3xHA-tagged rhomboid proteases for expression from the pCMV promoter, exactly as described previously (Baker et al., 2006). Note that all malaria and Trichomonas genes were codon optimized for efficient expression in human cells (Baker et al., 2006). Substrate and enzyme mutants were generated by QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis (Agilent Genomics) or an inverse PCR strategy. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Genewiz).

Heterologous Cell-Based Rhomboid Cleavage Assay

Cleavage of substrates and the activity of enzymes was determined in the widely used and standardized rhomboid heterologous cleavage assay (Baker et al., 2006). Briefly, HEK293T cells (ATCC CRL-11268) that we verified to be mycoplasma negative were seeded into 12-well plates, and ~80% confluent cells were co-transfected using X-tremeGENE-HP (Roche) with the appropriate DNA constructs for the expression of substrate and/or enzymes. To identify a ‘super-substrate’, cells were transfected with reduced levels of plasmid encoding rhomboid enzyme: substrate:enzyme ~ 250:1. 18-hours post transfection, cells were washed once and conditioned in serum-free DMEM (Sigma) containing the appropriate chemical compound where indicated. For cells transfected with AMA1, the metalloprotease inhibitor BB-94 (20μM) was included to reduce spontaneous ectodomain shedding. Media containing the GFP-tagged N-terminal cleavage product and their respective cells were harvested ~16–20-h later, resuspended in reducing LDS sample buffer, resolved on 4–12% gradient Bis-Tris gels in MES running buffer (Life Technologies), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes with a Trans-Blot (BioRad) semi-dry system. Membranes were probed with anti-GFP (AbCam, ab32146), anti-HA (Roche, 3F10), or anti-Flag (Sigma, F7425) primary antibodies, anti-rabbit/rat secondary antibodies conjugated to infrared fluorophores (Li-COR Biosciences) and imaged on an Odyssey infrared laser scanner (Li-COR Biosciences). The intensity of bands corresponding to rhomboid cleavage products was quantified using ImageStudio Software as instructed by the manufacturer (Li-COR Biosciences).

Cleavage Site Determination

To determine the cleavage site of rhomboid substrates, HEK293T cells were transfected as described above, lysed in RIPA buffer, and subjected to anti-FLAG immunopurification (Sigma). Eluent was spotted onto a sinapinic acid matrix and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry on a standards-calibrated Voyager DE Instrument (AB SCIEX) as previously described (Moin and Urban, 2012). Resultant spectra were analyzed and plotted in the R environment with aid of the MALDIquant package (Gibb and Strimmer, 2012).

Compound Synthesis

Peptide aldehydes and boronates were commercially custom synthesized using solid-phase chemistry, purified to >90% purity by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, and verified by ESI mass spectrometry. Peptide alpha-ketoamides were synthesized, purified and characterized as described previously (Ticha et al., 2017).

Co-Crystallization of Rhomboid and Peptides

Crystals of E. coli GlpG consisting of residues 87–276 (ΔN-GlpG) were prepared as described previously (Cho et al., 2016). Briefly, purified ΔN-GlpG was concentrated to 5 mg/ml in a buffer of 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, and 0.2% (w/v) nonyl-glycoside, and crystallized by hanging-drop method over a reservoir buffer of 0.1M Tris pH 8.5, 3M NaNO3, and 15% glycerol at room temperature. For soaking experiments, harvested crystals were transferred twice to a fresh drop consisting of 25mM Tris (pH 7.0), 2.5M NaCl, 0.2% nonyl-glycoside, and 15% glycerol for an hour. Stocks of peptide inhibitors were prepared at 20mM in 2.5M NaCl for Ac-VRMA-CMK and Ac-VRMA-B(OH)2, 20mM in RPMI for Ac-KRFRSMQYSA-B(OH)2, and 6mM in DMSO for Ac-RVWHA-CONH-phenylbutyl and added to the crystals to a final soaking concentration of 5 mM (except for Ac-RVWHA-CONH-phenylbutyl that was 1.5 mM). After soaking (5h for Ac-VRMA-CMK and Ac-VRMA-B(OH)2, and ~96h for Ac-KRFRSMQYSA-B(OH)2 and Ac-RVWHA-CONH-phenylbutyl), crystals were flash-frozen in a nitrogen stream.

Crystallography Data Collection and Refinement

Crystal diffraction data were collected on beamline F1 of the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source. Data was processed with iMosflm 7.1.1 (Battye et al., 2011) and structures were determined by molecular replacement with Molrep (Vagin and Teplyakov, 2010) in CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011) using an apo-structure (PDB ID 2IC8) as the model. The solutions of molecular replacement clearly showed inhibitors directly connected with catalytic S201 in electron density maps, and were modeled as the peptide-CMK and peptide-boronate after several iterative rounds of model building using COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and refinement using Refmac5. Structures were further refined using refmac5 and PHENIX (Winn et al., 2003), and R/Rfree values of the final models were 0.217/0.258 and 0.215/0.242 at 2.3Å with good geometry. Crystallographic data and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplemental Table S1.

Fitting of Dose-Response Curves

Dose-response curves were analyzed in the R environment. Curve fitting and graphing was performed with the DRC package and, unless indicated, dose-response curves were fitted with a 4-parameter logistic regression model, accounting for top and bottom baselines, the EC50 and the slope of the curve. Shaded regions reflect 95% CI of the fit. The EC50 is depicted along with its SE derived from the fit.

Inhibition of Endogenous GlpG in E. coli Cells

Analysis of GlpG rhomboid proteolysis in living E. coli cells was assayed exactly as recently described (Cho et al., 2016). Briefly, E. coli cells (wildtype NR698 strain and its ΔGlpG sister strain) harboring the pBAD-TatA-Flag plasmid were grown shaking at 250rpm and 37°C in Lauria broth supplemented with ampicillin until culture optical density monitored at 600nm reached 0.4–0.5. TatA-Flag expression was induced with 25μM L-arabinose, the indicated compounds were added directly to the cultures, and cultures were grown for an additional 2 hours shaking at 250 rpm and 37°C. For reversibility studies, media containing inhibitor was removed, cells were resuspended in media containing 100 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and grown for the indicated times. Cells were lysed in reducing and denaturing TricineSDS buffer, proteins were resolved on 16% Tricine polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen), and electro- transferred to nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad). TatA-Flag was detected with anti-Flag antibodies (Sigma, F7425) and secondary antibodies conjugated to IRDye 800CW or IRDye 680LT, and quantified on an Odyssey infrared fluorescence laser scanner using ImageStudio software (Li-COR Biosciences).

P. falciparum Invasion, Shedding, and Egress Assays

For iterative invasion assays, schizont-stage parasites were magnetically purified as previously described (Bates et al., 2010) (MACS Miltenyi Biotec) and incubated at the appropriate parasitemia (0.2% for dose-response curves) at 1.5% hematocrit in a 96-well plate in the presence or absence of the inhibitors. Flow cytometry analysis for absolute parasitemia determination and growth characterization was performed by removing a small volume of culture, washing cells in 1xPBS, resuspending them in 1xPBS containing 0.1 μg/mL acridine orange and monitoring FL1/FL3 fluorescence on a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences). All flow cytometry data were analyzed in FlowJo.

Methanol-fixed, acridine orange stained parasitized erythrocytes were imaged on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon) with bandpass filters. Images were overlaid in Photoshop CC (Adobe). Parasite egress was analyzed by isolating tightly heparin synchronized schizont-stage parasites (Boyle et al., 2010) by magnetic purification on a CS Column (Miltenyi Biotec) and then treating them with 10μM E-64, 300pM RiBn, or RPMI control. Treated schizonts were incubated under standard conditions at 1.5% hematocrit in a 96-well plate and analyzed by flow cytometry 8-hours post-treatment. Merozoites were isolated from magnetically purified synchronized schizonts (as described above) treated with 10μM E-64 (Sigma) for ~6 hours to inhibit egress while allowing schizonts to fully mature.

For merozoite invasion assays, E64 was removed by spinning for 5 min at 2000 × g and then resuspending in RPMI+HEPES. Merozoites, isolated by gentle filtration through a 1.2μm syringe filter (PALL), were incubated with erythrocytes at 1% hematocrit in standard culture media in 96-well plates in the presence or absence of inhibitor. Plates were agitated for 20 min at 290 rpm and then incubated under standard conditions for ~36 hours prior to measurement of absolute parasitemia by flow cytometry.

To assay merozoite shedding, mature schizonts were washed out of E64 (as described above), resuspended in 20mM Tris (pH 7.6) and 5mM CaCl2, and passed through a 1.2μm syringe filter. Following treatment with 25mM EGTA, 10μM RiKa or DMSO vehicle for 90 min at 37°C, merozoites were spun at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were added to non-reducing LDS sample buffer, resolved on 4–12% gradient Bis-Tris gels in MOPS running buffer (Life Technologies), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes with a Trans-Blot (BioRad) semi-dry system. Membranes were probed with anti-EBA175 (region VI) rabbit antisera (MRA-2) and anti-AMA1 rat monoclonal antibody 4G2, followed by anti-rabbit/rat secondary antibodies conjugated to infrared fluorophores (Li-COR Biosciences) before imaging on an Odyssey infrared laser scanner (Li-COR Biosciences). The intensity of bands corresponding to adhesin cleavage products was quantified using ImageStudio Software (Li-COR Biosciences).

Cell Viability of Peptide-Treated Human Cells

Cell viability of RiBn or RiKa treated HEK293T cells was determined with a LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Molecular Probes). Treatment with 5% DMSO was used as a positive control for cytotoxicity. Calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1 stained cells were imaged on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon) with the appropriate bandpass filters. Flow cytometry on the same samples was performed with a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences). For cell cycle distribution determination, RiBn-treated or untreated HEK293T cells growing in serum were washed in 1xPBS, fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol, RNase A treated and stained with 50μg/mL propidium iodine. Flow cytometry was performed as above by monitoring the FL2/FL3 channels.

Cell viability of RiBn or Rika treated human erythrocytes was determined by measuring extracellular hemoglobin levels using a Hemoglobin Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Human erythrocytes were cultured at 5% hematocrit in 12-well plates in the absence or presence of 100μM RiBn, 5μM RiKa, or 5% DMSO for 24h at 37°C. Culture samples were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min and 50μL of each supernatant was transferred to separate wells of a 96-well plate. Additional wells contained water (blank) and hemoglobin standard (Calibrator). Following addition of 200μL Reagent to each well and incubation at RT for 5 min, absorbance at 400nm was read using a Synergy H4 hybrid microplate reader (BioTek). Hemoglobin concentration was calculated using the formula [(A400sample) – (A400blank)/(A400calibrator)-(A400blank)] × 100mg/dL.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Invasion-competent P. falciparum merozoites were isolated from highly synchronized malaria cultures as described (Boyle et al., 2010). Magnet-purified schizonts from 50mL of culture were allowed to mature in the presence of 10μM E64 until ~70% were ready to egress. After spinning at 500 × g for 5 min, schizonts were resuspended in 3mL RPMI supplemented with 10mM HEPES and then passed through a 32mm 1.2μm filter using a 10mL syringe.

Invasive merozoites were incubated with erythrocytes for 2 or 10 min at 37°C with gentle agitation in the absence of peptide inhibitor, or with 100pM RiBn or 5pM RiKa, and then fixed by adding an equal volume of 2X fixing buffer (4% glutaraldehyde, 6mM MgCl2 in 0.2M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2) for 10min on ice. Fixed erythrocytes were spun at 500 × g for 3 min at 4°C, resuspended in 1X fixing buffer, and stored at 4°C overnight. After a buffer rinse (spinning for 5 min at 2.7 rpm), samples were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate for at approximately 1h on ice in the dark. Samples were rinsed in dH2O, followed by 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (0.22μm filtered) for 1 hr in the dark, and then dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (5 min each in 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%, 100%, and 100%), followed by two 5 min changes of propylene oxide (PO). Embedding was performed in 1:1 PO:Eponate 12 (Ted Pella) resin with 1.5% catalyst overnight (rocking) followed by three 2h changes and polymerization at 60°C overnight.

Thin sections of 60 to 90 nm were cut with a diamond knife on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome and picked up with 2×1 mm formvar copper slot grids. Grids were stained with 2% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol for 10 min, washed with H2O, and stained with 0.5% lead citrate for 1 min at 4°C before observation with a Philips CM120 TEM at 80 kV. Images were captured with an AMT CCD XR80 (8 megapixel camera - side mount AMT XR80 – high-resolution high-speed camera).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The number of replicates, precision of measurements, and statistical analysis methods are indicated in Figure Legends. For experiments in which representative data are shown, experiments were repeated with the same results. Data was fitted and analyzed for statistical significance using Prism software (Graphpad).

Supplementary Material

Table S2: Sequences of Oligonucleotides used for Site-Directed Mutagenesis (Related to Key Resources Table)

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-GFP, Clone E385 | Abcam | Cat#32146; RRID:AB_732717 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-HA, Clone 3F10 | Roche | Cat#11867423001 ; RRID:AB_390918 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Flag | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F7425; RRID:AB_439687 |

| Plasmodium falciparum EBA175 (region VI) rabbit antisera | Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (MR4) | Cat#MRA-2 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-AMA1 (4G2) | Sheetij Dutta (Walter Reed) | 4G2 |

| IRDye 800CW Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG | Li-Cor Biosciences | Cat#926-32213; RRID:AB_621848 |

| IRDye 680LT Goat anti-Rat IgG | Li-Cor Biosciences | Cat#926-68029; RRID:AB_10715073 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli: NR698 | Tom Silhavy (Princeton) | N/A |

| E. coli: NR698 ΔGlpG | Cho et al., 2016 | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| X-tremeGENE-HP DNA Transfection Reagent | Roche | Cat#06366546001 |

| Batimastat (BB-94) protease inhibitor | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#SML0041 |

| NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (4X) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#NP0007 |

| Bolt MES SDS Running Buffer (20X) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#B000202 |

| Novex Tricine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#LC1676 |

| Novex Tricine SDS Running Buffer (10X) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#LC1675 |

| ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A2220 |

| SA matrix kit | LaserBio Labs | Cat#M002 |

| Purified E. coli ΔN-GlpG (residues 87–276) | Wu et al., 2006 | N/A |

| Acridine Orange hydrochloride solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A8097 |

| E64 protease inhibitor | Thermo Fisher | Cat#78434 |

| Chloroquine diphosphate salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C6628 |

| Heparin sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#3149 |

| Eponate 12 Resin | Ted Pella, Inc. | Cat#18005 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Agilent Technologies | Cat#200518 |

| LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit for Mammalian Cells | Invitrogen Molecular Probes | Cat#L3224 |

| Hemoglobin Assay Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#MAK115 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| E. coli GlpG complexed with Ac-VRMA-CMK | This study | PDB: 6VJ8 |

| E. coli GlpG complexed with Ac-VRMA-B(OH)2 | This study | PDB: 6VJ9 |

| E. coli GlpG complexed with Ac-KRFRSMQYSA-B(OH)2 | This study | PDB: 6XRO |

| E. coli GlpG complexed with Ac-RVWHA-CONH-phenylbutyl | This study | PDB: 6XRP |

| E. coli GlpG complexed with Ac-IATA-CMK | Zoll et. al., 2014 | PDB: 5F5B |

| E. coli GlpG complexed with Ac-VRMA-CHO | Cho et. al., 2016 | PDB: 4QO2 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: HEK293T cells | ATCC | CRL-11268 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 | David Sullivan (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health) | 3D7 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| PfEBA175mini-Flag codon-optimized synthetic gene (dsDNA) 5’- GGTACCGGATCCCATAGCCATCATGGTAAT CGTCAGGATCGTGGTGGTAATAGCGGTAA TGTGCTGAATATGCGCAGCAACAATAACAA CTTCAACAATATCCCGAGCCGCTATAATCT GTATGATAAGAAACTGGATCTGGATCTGTA TGAAAATCGCAATGATAGCACCACCAAAGA ACTGATTAAAAAACTGGCCGAGATCAATAA GTGCGAAAATGAAATTAGCGTGAAATATTG CGATCACATGATTCATGAAGAAATTCCGCT GAAAACCTGCACCAAAGAAAAGACCCGTAA TCTGTGTTGTGCAGTGAGCGATTATTGCAT GAGCTATTTTACCTATGATAGCGAAGAATA TTACAACTGCACCAAACGCGAATTTGATGA TCCGAGCTATACCTGCTTTCGTAAAGAGGC ATTTAGCAGCATGCCGTATTATGCCGGTGC CGGTGTTCTGTTCATCATTCTGGTGATTCT GGGTGCAAGCCAGGCAAAATATCAGCGCC TGGAGAAAATCAACAAGAACAAGATTGAGA AAAACGTGAATGATTACAAGGACGATGACG ATAAGTAG-3’ |

Invitrogen | N/A |

| Site-directed mutagenic primer sequences are listed in Table S2 | Sigma-Aldrich | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: pcDNA-HA-PfROM4 | Baker et al., 2006 | PfROM4 wt |

| Plasmid: pcDNA-HA-PfROM1 | Baker et al., 2006 | PfROM1 wt |

| Plasmid: pcDNA-HA-TvROM1 | Riestra et al., 2015 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pcDNA-HA-TgROM5 | Brossier et al., 2005 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pcDNA-HA-RHBDL2 | Baker et al., 2006 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pcDNA-HA-DmRho4 | Baker and Urban, 2015 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pBAD-TatA-Flag | Dickey et al., 2013 | N/A |

| See Table S3 for additional plasmid constructs generated in this study | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Image Studio | Li-Cor Biosciences | Version 5 https://www.licor.com/bio/image-studio/ |

| MALDIquant package for R environment | Gibb and Strimmer, 2012 | Version 1.16.4 http://www.strimmerlab.org/software/maldiquant |

| DRC package for R environment | Ritz et al., 2015 | Version 3.0-1 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/drc/index.html |

| iMosflm | Battye et al., 2011 | Version 7.2.2 http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| Molrep | Vagin and Teplyakov, 2010 | Version 11.7.02 http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| CCP4 | Winn et al., 2011 | Version 7.0.078 http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| COOT | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | Version 0.8.9.2 http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| Refmac5 | Winn et al., 2003 | Version 5.8.0258 http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| PHENIX | Adams et al., 2010 | Version 1.13.2998 https://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| Prism | GraphPad Software | Version 8 https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| FlowJo | FlowJo | Version 10.6 https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo/downloads |

| Photoshop CC | Adobe | Version 19 https://www.adobe.com |

| RStudio | RStudio, Inc. | Version 1.0.143 https://rstudio.com |

| Other | ||

| Leuko-reduced human erythrocytes from Caucasian Male O+ donors | Interstate Blood Bank and David Sullivan (JHSPH) | N/A |

| Bolt 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus Gels (15 well) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#NW04125BOX |

| Novex 16% Tricine Protein Gels (15-well) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#EC66955BOX |

| Trans-Blot Turbo RTA Midi Nitrocellulose Transfer Kit | Bio-Rad | Cat#1704271 |

| LS columns | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-042-401 |

| CS columns | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-041-305 |

SIGNIFICANCE.

Malaria has been known for millennia, yet even today this scourge infects most of the world’s population and claims the lives of hundreds of thousands of children each year. The escalating problem of drug resistance has made developing a diverse cadre of new anti-malarials an indisputable priority. With a mechanistic focus, we characterized the atypical substrate specificity of PfROM4, and found it to be guided unexpectedly by steric clashes to avoid cleavage of inappropriate proteins rather than a natural affinity for true substrates. Exploiting this unusual mechanism allowed us to engineer a selective anti-PfROM4 inhibitor that does not cross react with other rhomboid enzymes. This new chemical tool revealed that it is possible to block PfROM4 function within the short time window of merozoite invasion, and selectively relative to host rhomboid proteases. Moreover, failure to shed adhesins from invading merozoites results in an inability to detach from the erythrocyte membrane that ultimately leads to death of such ‘tethered’ merozoites. In addition to compelling anti-PfROM4 drug development as a malaria therapeutic, our inhibitor design approach offers a clear path to testing the functional consequences of rhomboid proteases in the lifecycle of other unrelated parasites that are responsible for an array of devastating diseases worldwide.

Highlights.

malaria rhomboid PfROM4 cleaves only cell-surface adhesins required for invasion

steric clashes alone prevent rhomboid enzymes from cleaving each other’s substrates

inhibitors with designed steric blocks inhibit PfROM4 but not other rhomboid enzymes

inhibiting PfROM4 impedes resolution of merozoite invasion and clears parasitemia

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all members of the Urban Lab for support and helpful discussions, but especially to our friend and former lab member Dr Slavica Pavlovic-Djuranovic for teaching SG malaria culturing techniques, Barbara Smith of the Johns Hopkins Microscope Core Facility for expert help with TEM, and Pavel Majer of IOCB for providing advice and infrastructure for chemical synthesis. This work was supported by NIH grants 2R01AI066025 and 1R01AI110925, and a Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Pilot Project grant that supported initial malaria culture set-up. X-ray diffraction data was collected using instruments at CHESS (beamline supported by NSF grant DMR-0936384 and NIH grant GM-103485). KS acknowledges support from the Gilead Sciences & IOCB Research Centre, Czech Science Foundation (project no. 18-09556S), and Institutional Research Concept RVO 61388963 to IOCB.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

SG, SC, and SU are listed as inventors on US Patent US20190144498 for using tetrahedral-mimicking groups as rhomboid inhibitors in parasites. KS and SS are inventors on a patent for the general use of alpha-ketoamides as rhomboid protease inhibitors registered in the United Kingdom, EU, and USA (publication numbers GB2563396, EP3638686 and US20200095278, respectively).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC & Zwart PH (2010). Acta Cryst D66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanine DGW, Quinkert D, Kumarasingha R, Mehmood S, Donnellan FR, Minkah NK, Dadonaite B, Diouf A, Galaway F, Silk SE, et al. (2019). Human Antibodies that Slow Erythrocyte Invasion Potentiate Malaria-Neutralizing Antibodies. Cell 178, 216–228 e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RP, Wijetilaka R, and Urban S (2006). Two Plasmodium Rhomboid Proteases Preferentially Cleave Different Adhesins Implicated in All Invasive Stages of Malaria. PLoS pathogens 2, e113: 922–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxt LA, Baker RP, Singh U, and Urban S (2008). An Entamoeba histolytica rhomboid protease with atypical specificity cleaves a surface lectin involved in phagocytosis and immune evasion. Genes Dev 22, 1636–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman MJ, and Carruthers VB (2013). Recent insights into apicomplexan parasite egress provide new views to a kill. Curr Opin Microbiol 16, 459–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossier F, Jewett TJ, Sibley LD, and Urban S (2005). A spatially localized rhomboid protease cleaves cell surface adhesins essential for invasion by Toxoplasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 4146–4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, and Goldstein JL (2000). Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell 100, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus D, and Hadley TJ (1985). A Plasmodium falciparum antigen that binds to host erythrocytes and merozoites. Science 230, 553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesne-Seck ML, Pizarro JC, Vulliez-Le Normand B, Collins CR, Blackman MJ, Faber BW, Remarque EJ, Kocken CH, Thomas AW, and Bentley GA (2005). Structural comparison of apical membrane antigen 1 orthologues and paralogues in apicomplexan parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol 144, 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Baker RP, Ji M, and Urban S (2019). Ten catalytic snapshots of rhomboid intramembrane proteolysis from gate opening to peptide release. Nature structural & molecular biology 26, 910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]