Abstract

For half a century, the dominant paradigm in psychotherapy research has been to develop syndrome-specific treatment protocols for hypothesized but unproved latent disease entities, as defined by psychiatric nosological systems. While this approach provided a common language for mental health problems, it failed to achieve its ultimate goal of conceptual and treatment utility. Process-based therapy (PBT) offers an alternative approach to understanding and treating psychological problems, and promoting human prosperity. PBT targets empirically established biopsychosocial processes of change that researchers have shown are functionally important to long terms goals and outcomes. By building on concepts of known clinical utility, and organizing them into coherent theoretical models, an idiographic, functional-analytic approach to diagnosis is within our grasp. We argue that a multi-dimensional, multi-level extended evolutionary meta-model (EEMM) provides consilience and a common language for process-based diagnosis. The EEMM applies the evolutionary concepts of context-appropriate variation, selection, and retention to key biopsychosocial dimensions and levels related to human suffering, problems, and positive functioning. The EEMM is a meta-model of diagnostic and intervention approaches that can accommodate any set of evidence-based change processes, regardless of the specific therapy orientation. In a preliminary way, it offers an idiographic, functional analytic, and clinically useful alternative to contemporary psychiatric nosological systems.

Keywords: Psychotherapy, mediation, diagnosis, therapy process, process-based therapy, evolutionary science

When the era of evidence-based therapy began, Gordon Paul formulated one of the most widely cited questions that guided psychological intervention researchers for decades: “What treatment, by whom, is most effective for this individual with that specific problem, under which set of circumstances, and how does it come about?” (Paul, 1969, p. 44). Paul’s question was intended to push the field toward empirically supported treatments for specific psychological problems areas that fit the needs of given individuals based on known processes of change.

In the several decades that have followed this statement, we have learned an enormous amount about how to produce positive outcomes with specific methods, but empirical clinical psychology failed to answer Paul’s question. This failure is not surprising because the field’s attention was soon directed elsewhere. As an alliance formed between a syndromal approach in academic psychiatry and the intervention science of empirical clinical psychology, research increasingly focused on the impact of treatment protocols on the signs and symptoms of diagnostic entities as examined in randomized controlled trials.

Now that era is drawing to a close and new ways forward are being entertained that are more person centered (Ng & Weisz, 2016). In a series of recent writings on what we are calling Process-Based Therapy (PBT; Hayes & Hofmann, 2018), we have sought to lay down a progressive foundation composed of evidence-based processes of change that lead to evidence-based procedures that ease suffering and promote prosperity. In contrast to a protocol-for-syndromes approach, we intend to argue that a “functional first” approach will help us build a diagnostic system from the ground up, based on clinical utility. Intervention designed to induce psychological change is a dynamic process that involves many variables, traditionally studied as mediators and moderators. Mediators often form bi-directional and complex relationships that differ between individuals (Hofmann, Curtiss, & Hayes, 2020). By definition, these mediators respond to specific treatment (the “a path” of mediation) and relate to outcomes (the “b path” of mediation, which must be statistically related to outcome beyond any given treatment). Treatment processes and mediators are not fully synonymous (Hofmann et al, 2020). Yet, we can begin a diagnostic system with known mediators of importance because, unlike forty years ago when syndromal diagnosis first captured the field, hundreds of studies now exist on the mediators of clinical outcomes. Taken together, these mediational studies provide a strategic place to ask a new question that is at the core of process-based diagnosis: “What core biopsychosocial processes should be targeted with this client given this goal in this situation, and how can they most efficiently and effectively be changed?” (Hofmann & Hayes, 2019a, p. 38).

Processes of change have been defined as theory-based, dynamic, progressive, contextually bound, modifiable, and multilevel changes or mechanisms that occur in predictable, empirically established sequences oriented toward desirable outcomes (Hofmann & Hayes, 2019a). They are:

theory–based, in the sense that we associate them with a clear scientific statement of relations among events that lead to testable predictions and methods of influence;

dynamic, because they may involve feedback loops and non-linear changes;

progressive, because we may need to arrange them in particular sequences to reach the treatment goal;

contextually bound and modifiable, so they directly suggest practical changes or intervention kernels within the reach of practitioners; and

multilevel, because some processes supersede or are nested within others.

So defined processes of change are biopsychosocial functions of the person in context, as distinguished from the procedures, interventions, or environmental changes that engage such functions.

Processes of change alone cannot lead to a coherent diagnostic system: they must be organized. There are already hundreds of such processes, overwhelming any practitioner who may be interested in applying them. Instead we need to organize them by models that are comprehensive, internally coherent, and functional, and that provide broad guidance to practitioners and researchers (Hayes et al., 2020). In our opinion, no approach is better suited to do so than a multi-dimensional, multi-level extended evolutionary approach.

A Multi-dimensional, Multi-level Extended Evolutionary Approach

Evolutionary principles are the most widely used concepts when seeking to understand how complex systems. develop in the life sciences. An immunologist asked how the immune system came to be will almost certainly reply with an evolutionary answer; as would a cardiologist asked about her area, or orthopedist asked about hers. That is not yet true when it is a psychologist being questioned, but the reasons for that discontinuity are falling away.

Behavioral and mental attributes are as subject to evolutionary analysis as are physical and anatomical ones. In a non-reductionistic sense, behavior is as “biological” as one’s ears. Indeed, that very example is not arbitrary since we now know that several decades of breeding foxes to be more tame also results in the floppy ears that are often characteristic of domesticated animals -- it turns out that selecting for juvenile behavioral traits, such as tameness, brings juvenile anatomical traits along for the ride (Trut, 1999).

In the past, a major barrier to using evolution to inform psychological interventions was evolutionary scientists took a gene-centric approach that diminished attention to other evolving dimensions (e.g., cognition) and other levels of selection (e.g., the behavior of small groups). That, in turn, reduced the application of evolutionary principles to different questions at different time scales, from minutes to eons. Furthermore, unlike behavior change specialists, evolutionary scientists were extremely cautious about any claim that evolution can be purposive (Wilson, Andrews, & Thayler, 2018).

This barrier is ameliorated by Tinbergen’s “four question” approach to any product of evolution: what are its functions, what are the mechanisms or processes involved in accomplishing these functions, how does the particular feature or trait develop, and what is its history. When we combine these questions with a multi-dimensional and multi-level evolutionary perspective, we can construct a science of intentional change from an extended evolutionary account (Wilson, Hayes, Biglan, & Embry, 2014a, 2014b).

The present paper considers whether that approach can now apply to the diagnosis of psychopathology and planning of interventions. We will attempt to show that an extended evolutionary approach can provide a robust pathway forward, and will provide some preliminary evidence that this perspective has been hiding in plain sight in the clinical psychological literature for much of its existence.

Syndromal Diagnoses

The need for classification is an issue faced by any knowledge domain, for both proximal and ultimate purposes. The proximal purpose of nosology is to have a common language that allows scientists to observe, measure, and discuss phenomena in a domain. This makes scientific communication more straightforward, and it helps consumers of knowledge know the extent or impact of a set of events. The distal purpose is more varied but the hope is that classes of observation will yield order that allows us to predict, influence, and understand events in a way that is precise, broad in scope, and coherent across scientific domains.

For half a century, a syndromal model has driven psychiatric nosology. The strategy was that empirical sets of signs (things the practitioner can see) and symptoms (things people complain about) would lead to the discovery of underlying causes, expressed in an identifiable mechanistic course over time that could be altered in known ways. When a syndrome had a known etiology, mechanistic course, and response to treatment, it would become a disease. Identifying the specific latent diseases assumed to underlie psychiatric syndromes has always been the ultimate practical and scientific purpose of the current forms of psychiatric nosology.

The strategy is plausible, but in mental and behavioral health it has been unsuccessful. There is now broad agreement that the clinical utility of DSM-5 categories is extremely limited (Maj, 2018), and the hope for conceptual linkage between syndromes and underlying disease processes remain as distant as ever. The DSM-5 workgroup summarized the situation this way:

“(…) the goal of validating these syndromes and discovering common etiologies has remained elusive. Despite many proposed candidates, not one laboratory marker has been found to be specific in identifying any of the DSM-defined syndromes. Epidemiologic and clinical studies have shown extremely high rates of comorbidities among the disorders, undermining the hypothesis that the syndromes represent distinct etiologies. Furthermore, epidemiologic studies have shown a high degree of short-term diagnostic instability for many disorders. With regard to treatment, lack of treatment specificity is the rule rather than the exception. … reification of DSM-IV entities, to the point that they are considered to be equivalent to diseases, is more likely to obscure than to elucidate research findings” (Kupfer, First, & Regier, 2002; pp. xviii-xix).

In hindsight, the evidence-based wing of clinical psychology inadvertently helped cover over this failure by developing increasingly specific psychosocial interventions tested with well-crafted randomized trials that successful targeting DSM syndromes and sub-syndromes. Research on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in particular prospered following the publication of the DSM-III in 1980. A recent review of the literature identified 269 meta-analytic studies examining CBT for nearly every DSM category (Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012). While this research was progressive, adopting a syndromal focus came at a high cost for psychosocial methods. Once human struggles are cast as things you have, not the results of things you do, the game may be over for psychological methods, regardless of their empirical support. For example, recipients of care tend to become disinterested in undertaking psychotherapy when they are given a diagnosis based on a latent disease model (e.g., Zimmermann & Papa, 2019). In North America during just the ten years from 1998 to 2007, the sole use of psychosocial change methods for mental health problems fell by half. Using psychological methods combined with medications also fell by one-third. What ballooned was the use of medications alone. By the end of that decade, nearly two-thirds of those with psychological struggles were using only medication to deal with them while ten percent or less were using only psychosocial methods (Olfson & Marcus, 2010). When we consider the long-term effects, side effects, and costs of medications, these trends are difficult to defend empirically (Antonuccio, Thomas, & Danton, 1997; Ormel et al., 2020). For developers of psychosocial interventions, the considerable effort needed to create increasingly specific protocols for syndromes and sub-syndromes makes little sense if practitioners underuse these methods.

It is not possible for a diagnosis to have treatment utility unless assessment leads systematically to differential treatment recommendations (Hayes, Nelson, & Jarrett, 1987) and treatment specificity is now the exception with psychoactive medications. Hardly a mental health problem exists that has not been treated using SSRIs, for example. One has to ask: what good is a syndromal diagnosis in terms of clinical outcomes if it does not change what treatment is being received?

The biomedicalization of human suffering has had a variety of other negative effects on world health (Kohrt, Ottman, Panter-Brick, Konner, & Patel, 2020). Instead of being a robust area of human improvement, mental and behavioral health stand out as areas where human progress is lacking (Hayes, 2019). Something is wrong in the scientific development strategy.

When other areas of the life science have faced such dead ends they have generally gone back to basics. When the ability to classify plants based on topographical features hit a dead end, genetic similarity emerged to successfully reorganize the field (Morton, 1981). When focusing on the forms and features of cancerous lesions failed to produce sufficient program oncology stopped “botanizing cancer,” and began studying the genetic, epigenetic, and immune system processes that explained cancerous cell growth (Croce, 2008).

Many hoped that behavioral genetics alone would provide a similarly useful route forward for psychopathology and its amelioration, but after the successful mapping of the human genome in 2003, it became obvious how complex the gene systems are that impact behavioral phenotypes (Jablonka & Lamb, 2014). Studies with full genomic analyses of tens or even hundreds of thousands of participants sometimes identify cumulatively meaningful genetic risk factors, but they involve hundreds if not thousands of alleles, the specific functions of which are often not understood (Crespi, 2020; Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2013). The hope that behavioral genetics would rapidly lead to the identification of specific psychiatric diseases has been replaced by the relative certainty that this will not happen, leading to a healthy refocusing of the field toward aspects of psychological phenotypes rather than “disorders” per se.

An analytic problem is that behavior results from a diverse set of evolving dimensions and levels that include not only genes, but also many other processes. As a result, behavioral phenotypes that clearly involve genes are not necessarily genetic in a process of change sense.

Consider the example of appearance. Physical attractiveness is one of the most powerful demographic variables known to science (Langlois et al., 2000), and it is substantially genetic (Gangestad & Scheyd, 2005). These genetically established differences in appearance enter a complex network of social environmental influences. On one hand, what we perceive as attractive has to do with cues for fitness and reproductive likelihood (Hoffman, 2019). On the other, these social and cultural responses of others, that are central to the psychological and behavioral impact of physical attractiveness, can be manipulated by non-genetic means such as plastic surgery or eye contacts that provide cues known to relate to health, youth, and likely reproductive success (Hoffman, 2019). In the same sense that we cannot interpret any statistical “main effect” if it takes part in a statistical interaction, we cannot understand the conceptual importance of the genetic dimensions of evolution until we examine and model its interaction with other evolutionary dimensions.

The analytic challenge of this realization is profound. For example, even if we identify all genes related to mind and behavior, and the extent these genes generally interact with other dimensions and levels of selection, it is mathematically inappropriate to assume that a given genome can specify whether or not a specific individual will or will not develop a psychological problem. Population-based studies do not necessarily apply to individuals.

We have understood the general issue in the physical sciences for nearly a century. We cannot assume that the behavior of collectives (e.g., a volume of gas) models the behavior of an individual element (e.g., a molecule of gas) unless the material involved is “ergodic” and thus all elements are identical and are unaffected by change processes (for the original mathematical proof see Birkhoff, 1931). These conditions exist (some ideal gases are ergodic for example: Volkovysskii & Sinai, 1971), but not in biobehavioral areas, including psychopathology. No one assumes that persons with a given psychiatric diagnosis respond to the many events that can influence symptoms in the same sequence and pattern. If psychological phenotypes are not ergodic, however, statistical techniques based on inter-individual variation cannot properly assess the contribution of given elements to phenotypic change (Molenaar, 2008). Thus, we need a new approach to model the role of genes in clinical psychology as just one of multiple dimensions and levels of variation, selection, retention, and context sensitivity that together make up a given behavioral phenotype (Hofmann et al., 2020).

We see a concrete example of the problem when we examine how genes are being up and down regulated via the impact of environment and behavior on epigenetic processes (Schiele, Gottschalk, & Domschke, 2020). Environmental events and their accompanying psychological functions can lead to epigenetic changes (e.g., methylation of cytosine; histone bundling) that alter gene expression, and can lead not just to long-term changes in traits within an individual, but sometimes to changes in later generations and eventually to genetic accommodation (Jablonka & Lamb, 2014). Epialleles can be stable across generations even when DNA variation is absent (Johannes et al., 2009). Taken as a whole these facts suggest that not only epigenetics, but also the psychological events that impact epigenetics (such as learning processes, emotional process, and cognitive processes) need to be included in any extended evolutionary synthesis that will apply to psychopathology, human prosperity, and their modifications.

The evidence for very long-term and even trans-generational changes in gene expression because of programmed changes in environment and behavior affecting epigenetic variables is clear in non-human animals. For example, when mice who had a gene that supports the ability to learn removed, and were then exposed to an enriched environment containing elevated social interactions, novel objects, and voluntary exercise, not only did they show epigenetic changes leading to an enhanced ability to learn despite their genetic defect, so too did their offspring (Arai, Li, Hartley, & Feig, 2009). In humans, we also know that shorter-term epigenetic processes are modifiable by psychological interventions. For example, just two months of meditation results in changes in gene expression over about 7% of the person’s genome via induced epigenetic changes largely in areas linked to stress responsivity (Dusek et al., 2008). And we know that catastrophic environmental events (e.g., starvation in utero) can have long term and multi-generational effects (Jablonka & Lamb, 2014). It is not a big step to suppose that psychotherapy could deflect some of these trajectories.

An Initial Move toward Process: The RDoC Initiative

As it became apparent that after decades of research and clinical trials, the DSM-5 offered very little new as compared to its predecessors, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; Insel et al., 2010) initiative emerged as an attempt to move the field of psychiatry forward by turning in a more basic process direction. The goal was to create a research agenda that might yield a classification system that integrated biological and behavioral data rather than solely relying on topographical problem features derived from clinical impressions and subjective symptom report. RDoC called for researchers to explore different units of analysis (e.g., positive and negative motivational systems) across various levels of analysis (e.g., molecular, brain circuit, behavioral, cultural, and symptom level) to identify processes that might lead to psychopathology.

This was a step forward from syndromal classification, but the RDoC initiative provided no comprehensive model within which to integrate this information and artificially constrained focus to biological dimensions. Despite the official definition of a mental disorder as a multidimensional construct, the NIMH and academic psychiatry have long put the brain, genes, and biology front and center. Subjective experience and the cognitive, emotional, motivational, social, cultural, and behavioral aspects of a person’s history and current problems are listed but with the assumption that they play a comparatively minor role, or that they are important only where they alter brain or other biological processes. This “bio-bias” is reflected in the statement by the former director of NIMH that “mental illnesses are brain disorders” (Insel et al., 2010, p. 749). Such a statement implies that to understand a mental disorder, we need to understand the brain, and unless we understand the brain, we will never fully understand mental disorders. The effort to tilt the scale toward a predetermined central role for the brain was transparent and publicly stated. RDoC followed the following three principles:

“First, the RDoC framework conceptualizes mental illnesses as brain disorders. In contrast to neurological disorders with identifiable lesions, mental disorders can be addressed as disorders of brain circuits. Second, RDoC classification assumes that the dysfunction in neural circuits can be identified with the tools of clinical neuroscience, including electrophysiology, functional neuroimaging, and new methods for quantifying connections in vivo. Third, the RDoC framework assumes that data from genetics and clinical neuroscience will yield biosignatures that will augment clinical symptoms and signs for clinical management. Examples where clinically relevant models of circuitry-behavior relationships augur future clinical use include fear/extinction, reward, executive function, and impulse control. For example, the practitioner of the future could supplement a clinical evaluation of what we now call an “anxiety disorder” with data from functional or structural imaging, genomic sequencing, and laboratory-based evaluations of fear conditioning and extinction to determine prognosis and appropriate treatment, analogous to what is done routinely today in many other areas of medicine” (Insel et al., 2010, p. 749).”

The RDoC initiative was met with mixed responses. In general, neuroscientists applauded the initiative (Casey, Craddock, Cuthbert, Hyman, Lee, & Ressler, 2013). Others criticized it as being overly reductionistic and too biologically oriented (Deacon, 2013; Miller, 2010).

As is acknowledged by the authors and administrators of the initiative, RDoC has limited clinical utility -- it is primarily intended to advance future research, but is not yet intended as a guide for clinical decision making (Cuthbert & Kozak, 2013; Vaidyanathan et al., in press). And while the RDoC initiative invited the field to go back to the lab, it shared with the DSM the strong theoretical assumption that latent diseases cause psychological problems, and that we would identify these “diseases” through research focused on nonthetic collections. With the DSM, these latent constructs are measured through symptom reports and clinical impressions, whereas with RDoC, the variable of latent disease would be measured through sophisticated behavioral tests and biological instruments, such as genetic tests and neuroimaging.

In principle, RDoC opens the field to a complex network approach that offers an alternative, less restrictive, and more sound theoretical foundation for an empirically-based classification system (Hofmann & Hayes, 2019a). But this possibility has beebn hindered by RDoC’s reductionistic, biocentric application, by the continued search for latent diseases, and by the treatment of change processes as ergodic phenomena.

Insel eventually resigned as director from NIMH and the continued commitment of NIMH to RDoC is highly uncertain. Insel himself summarized his tenure: “I spent 13 years at NIMH really pushing on the neuroscience and genetics of mental disorders, and when I look back on that I realize that while I think I succeeded at getting lots of really cool papers published by cool scientists at fairly large costs—I think $20 billion—I don’t think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalizations, improving recovery for the tens of millions of people who have mental illness. I hold myself accountable for that” (Insel cited in Rogers, 2017).

The new director of NIMH appears to be choosing a similar path. While acknowledging the weaknesses of RDoC, Joshua Gordon has vigorously embraced a priori commitment to a brain-based etiological model, rather than pivoting toward a more empirically open approach. He showed this when he stated “a DSM symptom or RDoC domain both likely reflect a dysfunction in a latent construct such as executive function or working memory. These dysfunctions, in turn, reflect changes in brain physiological states, and those altered states have a root cause. We need to gain more information on those underlying causes” (Gordon cited in Zagorski, 2017).

We are not dismissing the potential importance of neurobiology, neuroimaging, and genetics. The biological details of development are central to a broad understanding of how biopsychosocial processes of change operate (e.g., Horn, Carter, & Ellis, 2020). Our own research suggests that brain imaging can predict treatment outcome (Anteraper, Triantafyllou, Sawyer, Hofmann, Gabrieli, & Whitfield-Gabrieli, 2014; Doehrmann, Ghosh, Polli, Reynolds, Whitfield-Gabrieli, Hofmann, Pollack, & Gabrieli, 2013; Hofmann, 2013); and some of the psychological processes we have studied appear to function as endophenotypes that help link behavioral features to underlying genetic influences over mental health (Gloster et al., 2015). It is questionable, however, whether clients or practitioners will want to rely on expensive medical tests or full genomic analyses to inform treatment. Further, to fully understand brain responses, we need to examine them in part as dependent variables (influenced by environmental history and context), not simply independent variables (causing disorder); to fully understand genetics we need to understand its role as part of a multi-dimensional and multi-level dynamical system (Andrews, Maslej, Thomson, & Hollon, 2020).

There is a bigger picture that clinical psychologists should not miss. Academic psychiatry no longer believes that additional billions spent on “protocols for DSM syndromes” will be scientifically or clinically progressive. Instead, researchers are being challenged by mental health funding agencies to identify functionally important processes of pathology and change. This is an exciting opportunity for clinical psychology. It suggests that the decades-long era of protocols for syndromes, trademarked therapies, and insular schools of thought is ending, to be replaced by a more process-based era. As the implications of a process-based approach are explored, we argue that it will lead to more attention being placed on the dynamic, idiographic, multi-dimensional, and multi-level nature of human functioning (Hofmann & Hayes, 2019b).

Back to Basics: An Idiographic Process-Based Approach

Clinical psychology does not arrive at this moment empty handed. Like a spiral staircase that takes a person back over familiar territory, in some ways the field of diagnosis and interventions is going back to the future. But like that same walk up a staircase, the field is now far above where it was the last time it focused on idiographic processes of change.

Humanistic therapy (e.g., Rogers, 1951), for example, assumed that psychological problems resulted from the person’s unique history and maladaptive adjustment strategies, rather than from a latent disease process. Maslow (1962) emphasized an idiographic and process-based approach, saying “I must approach a person as an individual unique and peculiar, the sole member of his class” (p. 10). What was missing from this more qualitative research approach were the experimental methods needed to produce a systematic, replicable, and proven classification and intervention system with known treatment utility.

Behavioral approaches similarly attempted to analyze what was unique based on functional principles of variation and selection at the level of the person and their development within their lifetime. Behaviorists targeted psychological problems based on functional analysis drawn from direct contingency principles. The problem was that these processes formed too small of a set. Almost immediately it was clear that we needed a more robust and functional account of human cognition. Behavior therapists soon added ideas drawn from social learning or neo-behavioral associative learning to Skinnerian operant principles in an attempt to understand human functioning (Bandura, 1969; Eysenck, 1961; Wolpe, 1958). As a cognitive approach such as was as pioneered by Beck (1970) and Ellis (1962) strengthened, early forms of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) emerged in which practitioners focused on maladaptive cognitions as contributors to emotional distress and behavioral problems.

The turn toward concepts and protocols that could be aligned with the latent disease model largely thwarted these promising process-based beginnings. A case in point is the story of panic disorder. The original conceptualization of “Panic Disorder” was based on a medical disease model that assumed distinct and mutually exclusive syndromes with an organic etiology and specific treatment indications (Klein, 1964; Klein & Klein, 1989). When Clark (1986) introduced his cognitive model he wrote: “Paradoxically, the cognitive model of panic attacks is perhaps most easily introduced by discussing work which has focused on neurochemical and pharmacological approaches to the understanding of panic” (p. 462).

Clark’s (1986) model conceptualized panic attacks as a consequence of the catastrophic misinterpretation of certain bodily sensations, such as palpitations and breathlessness. An example of such a catastrophic misinterpretation would be a healthy individual perceiving palpitations as evidence of an impending heart attack. The vicious cycle of the cognitive model suggests that various external (i.e., a supermarket) or internal (i.e., body sensations or thoughts) stimuli trigger a state of apprehension if these stimuli are perceived as threatening: “For example, if an individual believes that there is something wrong with his heart, he is unlikely to view the palpitation which triggers an attack as different from the attack itself. Instead he is likely to view both as aspects of the same thing - a heart attack or near miss” (Clark, 1986, p. 463).

The model does not rule out any biological factors in panic. Instead, it is assumed that biological variables may contribute to an attack by triggering benign bodily fluctuations or intensifying fearful bodily sensations. Therefore, pharmacological treatments can be effective in reducing the frequency of panic attacks if they reduce the frequency of bodily fluctuations which can trigger panic or if they block the bodily sensations, which accompany anxiety. However, if the patient’s tendency to interpret bodily sensations catastrophically is not changed, discontinuation of drug treatment should be associated with a high rate of relapse.

In broad terms, this model has support. For example, panic patients who were informed about the effects of CO2 inhalation reported less anxiety and fewer catastrophic thoughts than uninformed individuals (Rapee, Mattick, & Murrell, 1986). Furthermore, panic patients who believed they had control over the amount of CO2 they inhaled by turning an inoperative dial were less likely to panic than individuals who knew that they had no control over it (Sanderson, Rapee, & Barlow, 1989).

A hidden problem was that the very fact that these ideas could be standardized and manualized to target panic disorder as a syndrome meant that there was little need to link specific treatment components to individual functional analysis. That same basic story was repeated as the golden era of “protocols for syndromes” settled in. On one hand there was a fantastic rise in research and funding for psychotherapy studies, on the other, processes of change received less attention.

A set of concerns gathered in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s that shone a light on the need for both theoretical and philosophical development. These included empirical issues such as the unexpected success of overtly behavioral methods such as behavioral activation (Jacobson, Martell, & Dimidjian, 2001); unexpected results from large component analysis studies (Dimidjian et al., 2006; Jacobson et al., 1996); an early response to treatment that did not appear to fit with the accepted model (Ilardi & Craighead, 1994); and challenges to the consistency of evidence regarding processes of change (e.g., Bieling & Kuyken, 2003; Morgenstern & Longabaugh, 2000). In these areas there were counter arguments (e.g., Tang & DeRubeis, 1999), but as the century turned, well-settled matters within evidence-based psychotherapy were now under scrutiny, and these concerns dovetailed with the growing concern over the adequacy of syndromal diagnosis. Stated another way, the era of “protocols for syndromes” weakened with a growing concern both over the adequacy of protocol-based intervention and the adequacy of syndrome-based diagnosis.

The rapid rise of successful intervention models and methods that focused on the function of cognition and emotion (e.g., Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993); Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2001); Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2012)), reinvigorated a concern over processes of change. This interest was only increased as the moderators and mediators of these new methods emerged and were shown to relate to existing methods as well (e.g., Arch, Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2012). A field-wide consensus began to build (Klepac et al., 2012) for more clarity about philosophical assumptions; greater understanding of processes of change (Kazdin, 2007); an increased focus on fitting intervention methods to the needs of individuals (Ng & Weisz, 2016); and a greater emphasis on competency in delivering a wide variety of helpful inventions kernels (Weisz, Ugueto, Herren, Afienko, & Rutt, 2011) rather than trademark protocols (Hayes & Hofmann, 2018). Even as the field moved toward processes of change, however, it was clear that an overarching theory would be needed to avoid a cacophony of constructs (Goldfried, 2009).

An Extended Evolutionary Meta-Model

In the rest of the life sciences the theory that does that heavy lifting is evolution. If it is the case that we can view all complex life systems through the filter of an extended evolutionary synthesis, why not apply evolutionary thought to the organization of processes of change?

Behavioral scientists have underutilized evolutionary ideas, sometimes because of concerns over the debunked ideas of eugenicists, who ignored critical features of evolutionary science (such as the importance of variation, multi-dimensionality, and context) in their rush to apply their racist ideology to imagined genetic differences. As modern evolutionary science evolved, the scope and source of that error has become obvious. As that sad era passes into history, however, a fresh look is possible.

We have argued (Hayes, Hofmann, & Wilson, 2020) that an extended evolutionary approach is one that applies the key concepts of variation, selection, and retention, in context, focused on the relevant dimensions and levels. The approach is designed to answer Tinbergen’s (1963) four central questions of function, mechanism, development, and history.

Without variation, evolution is impossible, and it is not by accident that psychopathology is characterized by rigidity over flexibility. Difficult environments tend to increase variation, whether that involves mutation rates or DNA repair (Galhardo, Hastings, & Rosenberg, 2007) on one hand, or extinction (Catania, 1992) on the other. Being able to stay flexible is a key feature of “survival of the most evolvable” (Wagner & Draghi, 2010, p. 381), but pathogenic processes interfere with healthy variation.

Evolution cannot work without selection. Again, it is not by accident that psychotherapists have given careful thought to what successful outcomes mean as defined by such criteria as client values, social expectations, long term health, social functioning, happiness, euthymia, values, and other measures.

Retention is key to any prosocial change, and psychotherapy is used to these issues in the form of maintenance at follow up, the use of homework, the reinforcement of skill practice, or the development of health habits.

Context is key to diagnosis and treatment because no psychological attribute is always useful. We need to see behavior change in the context of the client’s current situation, history, culture, and goal. It is context that determines selection pressures over particular phenotypes, but it becomes a particular focus of conscious attention when the goal is intentional evolutionary change. For example, some new forms of emotional expression may only take hold if an individual deploys this expression in the context of a loving relationship. Concerns over natural contingencies, stimulus control, cultural fit, social support, and so on are all typical ways that practitioners speak of context in an evolutionary sense.

Context is relevant in another way. All species capable of contingency learning can select environments by their behavior (“niche selection”), but many can also create physical and social contexts that alter production and reproduction, what is called “niche construction.” Humans are especially adept at niche construction. For example, they may deliberately create the kinds of relationships in which emotional growth is possible. The impact of niche selection and construction is one reason that learning is the ladder of evolution (Bateson, 2013).

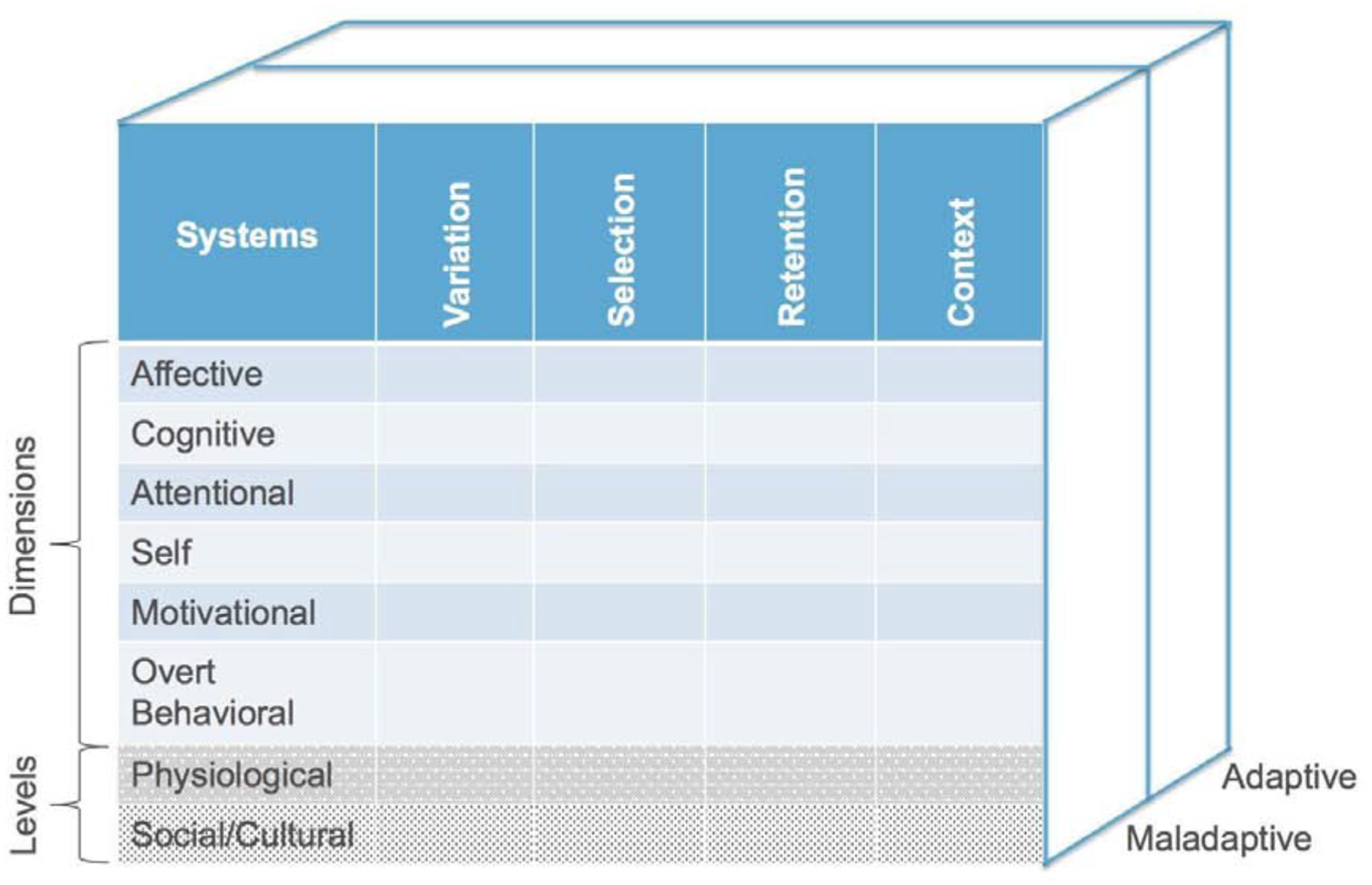

These processes of variation, selection, retention and context apply to all inheritance streams or dimensions. In previous work (Hayes et al., 2019), we have identified six dimensions of importance at the psychological level: affect, cognition, attention, motivation, self, and overt behavior (See Figure 1). By the “psychological level” we mean the level of the individual whole organism interacting in and with a context consider historically and situationally. By “dimensions” we mean the content domains within which processes of change are organized. For example, emotional acceptance is a process within affect as a dimension or content domain; similarly reappraisal is a processes within cognition as a dimension. We are not arguing that these psychological dimensions are discrete, or form an ultimate, irreducible set; but that they capture the dimensions most commonly emphasized and measured in clinical models. As one indication of that, most elements of our model are also echoed in the domains identified by the RDoC initiative (Insel et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

An extended evolutionary meta-model of change processes (copyright Steven C. Hayes and Stefan G. Hofmann)

Finally, selection operates simultaneously at different levels of organization that are nested in an arc of organizational complexity. A vast literature on multilevel evolution suggests that selection at the level of a small group sometimes predominates, provided the group can restrain selfishness of lower levels of organization. An example is the multicellular organism. Humans are composed of over 37 trillion cells (Bianconi et al., 2013), and while millions of them die each second, overall they do better as part of an organism than they would on their own. Selfishness at the level of the cell exists (in the form of cancerous growths for example) but the body continuously attempts to detect and rein in such selfishness.

In a similar way, while selfish behaviors of individuals may exist within a social group such as a family, team, or business, we can predict the effectiveness of these small groups by the degree to which aspects of the group foster cooperation, support individual needs, and restrain selfishness that diminishes cooperation (Wilson, Ostrom, & Cox, 2013). A multi-level selection perspective can predict social cultural features of human development that are key to psychological health, such as nurturance (Biglan, Johansson, Van Ryzin, & Embry, 2020). This “groups all the way down” approach suggests that processes at any level of complexity are nested within those at other levels. The psychological level is thus nested with the sociocultural level of group behavior and cultural practices (Wilson & Coan, 2020), but the psychological level in turn contains a genetic/physiological level -- genes, epigenes, brain circuits, organ systems, and so on -- and the other life forms contained within. Indeed, individual human beings are not just organisms, they are ecosystems. The “individual” human is a massive group of a wide variety of life forms – there are 150 times more genes in a person’s gut microbiome than in their own cells (Zhu, Wang, & Li, 2010). These microorganisms in turn have known impact on mental health (Mohammadi et al., 2016).

In diagnosis and treatment, the analysyst examines the six dimensions and two nested levels of organization, as these issues apply to issues of function, mechanism, development, and history. For example, the analyst may examine the function served by a given psychological pattern; how these features of pathology and health developed within the lifetime; what are the specific physical and psychological processes that make up these events; and what is their longer evolutionary history. Our model (Figure 1) links such questions both to maladaptive and adaptive issues. It is important to examine both adaptive and maladaptive processes because health is more than the removal of pathology; intervention needs to be focused on building human prosperity not just eliminating pathology. For example, reducing the use of a generally maladaptive process such as thought suppression might best be done by fostering positive processes such as attentional flexibility.

Taken together, the concepts we have been discussing combine to form an extended evolutionary meta-model (EEMM) -- that can in principle draw process-based work under a single umbrella, providing a kind of functional diagnostic system (Hayes et al., 2019; Hayes, Hofmann, & Ciarrochi, in press). We believe that the EEMM applies to virtually all known theory-based and empirically well-supported processes of treatment change.

The columns of the model in Figure 1 represent the key evolutionary concepts of variation, selection and retention in a given context. Maladaptation occurs because of problems in any of these systems. Although we do not claim that this is the final list of dimensions, we believe that it is reasonably comprehensive at the psychological level. We are not here adding dimensions to the levels of sociocultural processes and genetic/physiological process, but in the latter area it has begun (e.g., Hayes, Hofmann, & Stanton, in press; see also Atkins, Wilson, & Hayes, 2019).

We do not assume that these dimensions are independent constructs. Rather, the dimensions and levels are likely to form complex networks for any individual client. We need to examine the interrelatedness of these dimensions and the levels within functional-analytic networks for each client.

The EEMM provides a systematic framework to consider the potential contribution of any of these dimensions and levels to the particular problem space of an individual. For example, a client may display limited variation in affect but also shows exaggerated emotional responses to even minor events (and who might be diagnosed as borderline personality disorder in our conventional system); a client may display problems with selection of cognitions, as expressed by a consistent negative cognitive bias toward social encounters (and who might be diagnosed with social anxiety disorder in the DSM); and an alcoholic client may display a problem with retention of adaptive behaviors by returning to drinking with his drinking buddies after a brief period of recovery.

Many more examples can illustrate context-specific problems with variation, selection, and or retention. Some examples will be clearer than others, but we believe that any aspect of human suffering can be identified and coded in the EEMM. Once identified, clinicians can then apply specific treatment techniques to target the specific cells in the EEMM that are associated with maladaptation. For example, clinicians can target problems with affective variation through emotion regulation techniques; problems with cognitive selection bias through cognitive reappraisal; and problems with alcoholic relapse through motivational enhancement or contingency management strategies that restructure the client’s social life in order to retain the gains he or she has made. As noted above, these are simplistic examples to illustrate a concept. The dimensions and levels are highly interconnected and many of the treatment techniques target a multitude of systems and levels.

Trained clinicians generally know the intervention strategies, which comprise a circumscribed (yet expandable) list of “treatment kernels” we described elsewhere (Hayes & Hofmann, 2018). As reported in a recent review (Kazantzis, Luong, Usatoff, Impala, Yew, & Hofmann, 2018), these techniques are common and well-supported in the CBT literature. This review identified 30 meta-analyses since 2000 that have examined processes of change in CBT. We found that CBT had generally medium to large effects on cognitive processes such as reappraisal, reframing, and restructuring. For example, CBT changes self-efficacy in panic disorder (Fentz, Arendt, O’Toole, Hoffart, & Hougaard, 2014), trauma related cognitions in PTSD (Diehle, Schmitt, Daams, & Boer, 2014), imagery rehearsal in PTSD (Casement & Swanson, 2012), and problem solving for anxiety and depression (García-Escalera, Chorot, Valiente, Reales, & Sandín, 2016). CBT also appears to have small to large effects on behavioral strategies such as activity scheduling, exposure, and contingency management (Ale, McCarthy, Rothschild, & Whiteside, 2015; Chu & Harrison, 2007; Sánchez-Meca, Rosa-Alcázar, Marín-Martínez, & Gómez-Conesa, 2010). Finally, several people have posited that therapeutic alliance is an essential mediator of outcome (Priebe & Mccabe, 2008). Correlational meta-analytic research suggests that alliance has small to moderate associations with therapy outcome (Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, Symonds, & Horvath, 2012), but its role as a mediator is inconsistent in part because differential effects on the alliance because of treatment (the “a path”) are often not found (e.g., Anderson, Spence, Donovan, March, Prosser, & Kenardy, 2012).

Consider how cognitive processes such as reappraisal, reframing, and restructuring would be placed into the EEMM. These processes have to do with context-appropriate cognitive flexibility. In the short term, CBT therapists attempt to promote retention of these cognitive skills by practice, repetition, and homework, but in the long term they promote retention and prevent relapse by linking the skills to certain key situations in which they might make a critical difference in outcomes – providing selection and retention mechanisms in the client’s day to day life. In a similar fashion, activity scheduling, problem solving, and contingency management focus on variation and selection issues in overt behavior.

The EEMM is similarly consistent with so-called “third wave” forms of CBT such as ACT. We can show this by providing examples drawn from the online list of about 50 mediational studies (https://contextualscience.org/act_studies_with_mediational_data). ACT outcomes are consistently mediated by the six primary aspects of psychological flexibility, which line up with the six psychological dimensions of the EEMM. Researchers have shown this, for example, in areas such as change in acceptance or cognitive defusion in the treatment of Type II diabetes (Gregg, Callaghan, Hayes, & Glenn-Lawson, 2007), smoking cessation (Bricker, Wyszynski, Comstock, & Heffner, 2013), or chronic pain (Wicksell, Olsson, & Hayes, 2010, 2011). Acceptance involves emotional flexibility and as with traditional CBT, ACT therapists try to link its deployment to person-specific emotional cues, and foster its retention by the greater behavioral freedom and effectiveness it promotes. Researchers have also identified changes in values (Lundgren, Dahl, & Hayes, 2008) or committed action (Forman, Chapman, Herbert, Goetter, Yuen, & Moitra, 2012) as mediators. These fit in the selection of motivational processes, or variation, selection, and retention issues in the overt behavioral domain.

Stockton and colleagues (2019) subjected the more recent mediational studies in this area (since 2006) to their first meta-analysis, which concluded that there was mediational evidence for most of the psychological flexibility model underlying ACT. A strength that they noted of the ACT mediational evidence base is that many studies also examined mediators drawn from traditional CBT, including self-efficacy, negative or dysfunctional cognition, and general clinical measures such as symptom distress or pain intensity. These other processes do not consistently mediate ACT outcomes and thus the authors concluded that “processes of change in ACT are predominantly linked to the various components of the psychological flexibility model.” This finding suggests that models of intervention will still matter in a process-based era since change processes sometimes respond differently to components and models that specifically target them.

It is worth noting the larger lesson of the acceptance and reappraisal examples we have just described, namely, that selection and retention often involve the construction of positive feedback loops that go across dimensions or levels. Thus, we should not think of the EEMM as a cellular model with specific processes fit in each cell. Each row of the model appears to be important to comprehensive approaches to behavior change, and each column is needed for each process, but many specific cells are filled by the dynamic relationship among elements in the overall model. For example, the selection criteria for reappraisal may be found in its behavioral effectiveness; and its retention may be found in regular practice and use in emotionally challenging situations.

Importantly, processes of change point across levels of analysis. For example, while psychological inflexibility has a negative relation to distress about a pandemic, some of that impact is because of the neurobiological strain caused by poor sleep patterns (Peltz, Daks, & Rogge, 2020). Similarly, while mindfulness meditation affects biologically relevant outcomes as telomere length that influence is mediated by experiential avoidance (Alda et al., 2016), and the influence of therapist guided exposure on panic can be partially explain by changes in the neural correlates of fear conditioning (Straube et al., 2014). The frequency of process-based findings of this kind suggests that a process focus structured by the EEMM will not under emphasize biophysiological processes. That is also true of sociocultural processes as the next section shows.

Therapeutic relationship

The construct of the therapeutic relationship is so central and controversial in clinical intervention research that it warrants its own section. Therapeutic relationship is sometimes cast as a moderator (Spielmans & Flückiger, 2018), that is, a positive therapist relationship is hypothesized to improve the strength of the link between intervention and outcome. In this conception, intervention it thought to work better when clients form an alliance with a clinician. Perhaps a more controversial claim is that it therapeutic relationship is the critical mediator of therapeutic change (Budd & Hughes, 2009; Priebe & Mccabe, 2008). In this conception, perhaps all interventions, whether they are traditional CBT, psychodynamic, or ACT, work through a common core process: by building a strong therapeutic relationship. In extreme versions of this proposal, techniques specific to each therapy are argued to be unimportant. If true, one would expect the same outcomes regardless of intervention after adjusting for this process -- what has sometimes been termed the “dodo” bird effect.

There is clear evidence that better therapeutic relationship is associated with better outcomes (Cameron, Rodgers, & Dagnan, 2018), but does it follow that therapeutic relationship is the key mechanism of change in all therapy? We can use a process-based lens to view this issue. We would argue that what matters is not so much the positive therapeutic relationship per se, but whether positive relationships instigate, model, and support processes of change. If this idea is correct, then therapeutic relationship will be a powerful predictor not because it is the only important mechanism of change, but because it subsumes so many other mechanisms of change. If so, the key advantage of a process model would be that it gives clear instruction to the therapist on how to build a positive therapeutic relationship.

There is indirect evidence for this idea. Therapists who embody mindfulness process have high working alliance scores (Johnson, 2018). Clinicians who engage in a brief mindful centering process before session increase in effectiveness (Dunn, Callahan, Swift, & Ivanovic, 2013). Most of the key aspects of a therapeutic relationship might be subsumed under such processes as contacting the present moment, accepting difficult experiences, and engaging in valued action even in the presence of difficult internal experiences such as pain and distress. In other words, a strong therapeutic relationship may model, instigate, and support important processes of change and clients most benefit when they internalize those messages. If so, the alliance is a means to a process-based end. There are data supporting this idea as well. Research using multiple mediator models to explain outcomes of randomized controlled trials of ACT shows that psychological flexibility not only mediates outcomes, it statistically eliminates the functional role of the therapeutic relationship in mediating outcomes (e.g., Gifford et al., 2011; Walser, Karlin, Trockel, Mazina, & Taylor, 2013). Said in another way, a positive therapeutic relationship socially instigates, models, and supports key processes of change (e.g., acceptance, nonjudgment).

As these ideas are explored in more detail it is quite possible to create EEMMs that analyze the dyadic level into several process dimensions, nested in between a psychological level and the level of groups of groups (see Hayes, Hofmann, and Ciarrochi, 2020 for one such attempt) or to do likewise with the biophysiological level. The psychological level is distinguishable from other levels of analysis, but many psychological processes are themselves the result of social processes, and selection at the level of groups arguably gives primacy in many areas to the social history (phylogenetically and ontogenetically) that arguably has led to such psychological phenomena as human cognition (Hayes & Sanford, 2014).

Implications for the Future of Clinical Science

We believe that the era of protocols for syndromes has ended. Instead, a process-based approach is emerging. Although this approach is progressive, it is also positive and inclusive to any theoretically-sound and evidence-based approach.

A process-based approach to clinical practice is not just another name for eclecticism because it is necessary to organize processes of change into models that guide their selection and application (Hayes, Hofmann, & Ciarrochi, 2020). Over 15 years ago, the first book-length summary of processes of change (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004) could already identify over 100 such processes, and researchers have proposed many additional processes since. It is necessary to simplify the list, by theory and evidence. That is what models do. By “model” we mean an empirically and theoretically integrated set of change processes that guide the selection and deployment of interventions.

In Hayes, Hofmann, and Ciarrochi (in press) we describe three central features of viable models of change: they need to have clear philosophical assumptions; be comprehensive, coherent, and functional; and apply to many, if not most, clients. The models need philosophical clarity because if a model mixes its underlying assumptions incoherently, analytic confusion and wasted research energy will result. Concepts within a model are vitalized by their consistent connections to other concepts within the model, and unclear or inconsistent assumptions will undermine those connections. The need for comprehensive, coherent, and functional models of change progress requires that models cover enough key processes over relevant dimensions and levels that they can imply specific intervention steps that apply to the level of the individual. Said in another way, any adequate model of change processes should lead to forms of functional analysis that allow practitioners to select treatment elements that will produce better outcomes for individual clients. Models themselves need to be shown to have both conceptual and treatment utility (Hayes, Nelson, & Jarrett, 1987). Finally, the model must produce positive results across a broad range of clients.

We can use the EEMM to create a new form of process-based functional analysis (Hayes, Hofmann, & Stanton, in press) that builds on classical functional analysis (Haynes & O’Brien, 1990) but that solves its key problems (Hayes & Follette, 1992), such as the overuse of a limited set of direct contingency principles, the inability to define a reasonably limited set of assessment targets a priori, and the weak link to intervention recommendations. By populating the EEMM with the processes of change suggested by a specific model, we ameliorate all of these problems. We make the steps of classical functional analysis more precise and more intervention focused by considering the elements of the EEMM, applying them ideographically to the specific case, and looking for self-amplifying inter-relationships of maladaptive processes that select and retain rigid and context insensitive patterns of action. For a step by step application of this idea see Hayes, Hofmann, and Stanton, in press, and Hayes, Hofmann, and Ciarrochi, 2020).

The EEMM is a model of models from which specific forms of such models can be developed and compared. It offers a meta-theory of intervention relevant functional analytic models, rooted in evolutionary science, that directly link analysis to psychological intervention,. We believe that this system offers a viable and clinically useful beginning alternative to contemporary nosological systems, such as the DSM, ICD, and the RDoC.

The field of clinical science has reached the maturity to embrace evolutionary science principles as its overarching framework. The articles in this special issue show that these principles can provide the consilience needed to take on extremely diverse clinical science questions, while maintaining helpful linkages between these questions and the evidence-based answers they generate. Evolutionary science is the foundation of the clinical science of the future.

Highlights.

A syndrome-based approach to mental health is inadequate

A process-based approach offers an alternative

An extended evolutionary meta-model provides a common language for process-based diagnosis

Biography

Steven C. Hayes is Nevada Foundation Professor in the Behavior Analysis program at the Department of Psychology at the University of Nevada. An author of 44 books and nearly 600 scientific articles, his career has focused on an analysis of the nature of human language and cognition and the application of this to the understanding and alleviation of human suffering. He is the developer of Relational Frame Theory, an account of human higher cognition, and has guided its extension to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a popular evidence-based form of psychotherapy that uses mindfulness, acceptance, and values-based methods. Dr. Hayes has been President of Division 25 of the APA, of the American Association of Applied and Preventive Psychology, the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, and the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science. He was the first Secretary-Treasurer of the Association for Psychological Science, which he helped form and has served a 5 year term on the National Advisory Council for Drug Abuse in the National Institutes of Health. In 1992 he was listed by the Institute for Scientific Information as the 30th “highest impact” psychologist in the world and Google Scholar data ranks him among the top ~1,500 most cited scholars in all areas of study, living and dead (http://www.webometrics.info/en/node/58). His work has been recognized by several awards including the Exemplary Contributions to Basic Behavioral Research and Its Applications from Division 25 of APA, the Impact of Science on Application award from the Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy

Stefan G. Hofmann, Ph.D. is Professor of Psychology at Boston University, where he is the Director of the Psychotherapy and Emotion Research Laboratory. He was born and raised in Germany and has been living in Boston, USA, since 1996. He has published widely as an author of more than 300 articles and 15 books. He is a Highly Cited Researcher by Thomson Reuters and Clarivate Analytics. His research focuses on the mechanism of treatment change, translating discoveries from neuroscience into clinical applications, emotion regulation, and cultural expressions of psychopathology, especially anxiety disorders. Because of this expertise, he served as an advisor to the DSM-5 Development Process and was a member of the DSM-5 Anxiety Disorder Sub-Work Group. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including the ABCT’s 2010 Outstanding Service Award, the Aaron T. Beck Award for Excellence in Contributions to CBT by Assumption College, and the Aaron T. Beck Award for Significant and Enduring Contributions to the Field of Cognitive Therapy by the Academy of Cognitive Therapy. He is a fellow of the American Psychological Association and the Association for Psychological Science. He has also been president of numerous national and international professional societies, including the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) and the International Association for Cognitive Therapy (IACP). He is presently editor-in-chief of Cognitive Therapy and Research and associate editor of Clinical Psychological Science. His research has been funded through generous research grants from the National Institutes of Health private foundations.

Professor Joseph Ciarrochi has published many books, including the bestselling Get out of your mind and into your life teens and the widely acclaimed Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: the Seven Foundations of Well-Being. His research interests include identifying character strengths that promote social, emotional, physical well-being and performance, and contextual behavioural science.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Hayes: No COI. He receives financial support from NIH/NCCIH (R44AT006952). He also receives compensation for his work as a content expert from New Harbinger Publications. He also receives royalties and payments for his editorial work from various publishers.

Dr. Hofmann: No COI. He receives financial support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (as part of the Humboldt Prize), NIH/NCCIH (R01AT007257), NIH/NIMH (R01MH099021, U01MH108168), and the James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Understanding Human Cognition – Special Initiative. He receives compensation for his work as an advisor from the Palo Alto Health Sciences and for his work as a Subject Matter Expert from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and SilverCloud Health, Inc. He also receives royalties and payments for his editorial work from various publishers.

Joseph Ciarrochi: No COI

References

- Alda M, Puebla-Guedea M…. & Garcia-Campayo J (2016). Zen meditation, length of telomeres, and the role of experiential avoidance and compassion. Mindfulness, 7, 651–659. Doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0500-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ale CM, McCarthy DM, Rothschild LM, & Whiteside SPH (2015). Components of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Related to Outcome in Childhood Anxiety Disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(3), 240–251. 10.1007/s10567-015-0184-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson REE, Spence SH, Donovan CL, March S, Prosser S, & Kenardy J (2012). Working alliance in online cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders in youth: Comparison with clinic delivery and its role in predicting outcome. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), e88 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PW, Maslej MM, Thomson JA, & Hollon SD (2020). Disordered doctors or rational rats? Testing adaptationist and disorder hypotheses for melancholic depression and their relevance for clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anteraper SA, Triantafyllou C, Sawyer AT, Hofmann SG, Gabrieli JD, & Whitfield-Gabrieli S (2014). Hyper-connectivity of subcortical resting state networks in social anxiety disorder. Brain Connectivity, 4(2), 81–90. doi: 10.1089/brain.2013.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonuccio DO, Thomas M, & Danton WG (1997). A cost-effectiveness analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and fluoxetine (Prozac) in the treatment of depression. Behavior Therapy, 28 (2), 187–210. 10.1016/S0005-7894(97)80043-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arai JA, Li S, Hartley DM, & Feig LA (2009). Transgenerational rescue of a genetic defect in long-term potentiation and memory formation by juvenile enrichment. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(5), 1496–1502. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5057-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Eifert GH, Davies C, Vilardaga JCP, Rose RD, & Craske MG (2012). Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 750–765. doi: 10.1037/a0028310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Eifert GH, & Craske MG (2012). Longitudinal treatment mediation of traditional cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(7), 469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins P, Wilson DS, & Hayes SC (2019). Prosocial: Using evolutionary science to build productive, equitable, and collaborative groups. Oakland, CA: Context Press / New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson P (2013). Evolution, epigenetics and cooperation. Journal of Biosciences, 38, 1–10. 10.1007/s12038-013-9342-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1970). Cognitive therapy: Nature and relation to behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 1(2), 184–200. 10.1016/S0005-7894(70)80030-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1969). Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Bianconi E, Piovesan A, Facchin F, Beraudi A, Casadei R, … Canaider S (2013). An estimation of the number of cells in the human body. Annals of Human Biology, 40(6), 463–471. 10.3109/03014460.2013.807878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, & Kuyken W (2003). Is cognitive case formulation science or science fiction? Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 10 (1), 52–69. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.10.1.52 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Johansson M, Van Ryzin M, & Embry D (2020). Scaling up and scaling out: Consilience and the evolution of more nurturing societies. Clinical Psychology Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkhoff GD (1931). Proof of the ergodic theorem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 17(12), 656–660. 10.1073/pnas.17.2.656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J, Wyszynski C, Comstock B, & Heffner JL (2013). Pilot randomized controlled trial of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(10), 1756–1764. 10.1093/ntr/ntt056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd R, & Hughes I (2009). The Dodo Bird Verdict—controversial, inevitable and important: a commentary on 30 years of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 16(6), 510–522. 10.1002/cpp.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SK, Rodgers J, & Dagnan D (2018). The relationship between the therapeutic alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with depression: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(3), 446–456. 10.1002/cpp.2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casement MD, & Swanson LM (2012). A meta-analysis of imagery rehearsal for post-trauma nightmares: effects on nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and posttraumatic stress. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 566–574. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Craddock N, Cuthbert BN, Hyman SE, Lee FS, & Ressler KJ (2013). DSM-5 and RDoC: Progress in psychiatry research? Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 14(6), 810–814. doi: 10.1038/nm3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC (1992). Learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, & Harrison TL (2007). Disorder-specific effects of CBT for anxious and depressed youth: a meta-analysis of candidate mediators of change. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10(4), 352–372. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0028-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(4), 461–470. 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi B (2020). Evolutionary and genetic insights for clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce CM (2008). Oncogenes and cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 502–511. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra072367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2013). Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: A genome-wide analysis. Lancet, 381, 1371–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, & Kozak MJ (2013). Constructing constructs for psychopathology: The NIMH Research Domain Criteria. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(3), 928–937. doi: 10.1037/a0034028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon BJ (2013). The biomedical model of mental disorder: A critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research. Clinical Psychology Review, 33 (7), 846–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehle J, Schmitt K, Daams JG, & Boer F (2014). Effects of psychotherapy on trauma‐ related cognitions in posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress,27(3), 257–264. 10.1002/jts.21924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME, … & Jacobson NS (2006). Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 658–670. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehrmann O, Ghosh SS, Polli FE, Reynolds GO, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, … & Gabrieli JD (2013). Predicting treatment response in social anxiety disorder from functional magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(1), 87–97.doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn R, Callahan JL, Swift JK, & Ivanovic M (2013). Effects of pre-session centering for therapists on session presence and effectiveness. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 23(1), 78–85. 10.1080/10503307.2012.731713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusek JA, Otu HH, Wohlhueter AL, Bhasin M, Zerbini LF, … & Libermann TA (2008). Genomic counter-stress changes induced by the relaxation response. PLoS ONE, 3, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ (1961). Classification and the problem of diagnosis In Eysenck HJ (Ed.), Handbook of abnormal psychology (pp. 1–31). New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fentz HN, Arendt M, O’Toole MS, Hoffart A, & Hougaard E (2014). The mediational role of panic self-efficacy in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 60, 23–33. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Symonds D, & Horvath AO (2012). How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 10–17. doi: 10.1037/a0025749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Chapman JE, Herbert JD, Goetter EM, Yuen EK, & Moitra E (2012). Using session-by-session measurement to compare mechanisms of action for acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy. Behavior Therapy, 43 (2), 341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galhardo RS, Hastings PJ, & Rosenberg SM (2007). Mutation as a stress response and the regulation of evolvability. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 42, 399–435. 10.1080/10409230701648502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad SW & Scheyd GJ (2005). The evolution of human physical attractiveness. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34(1), 523–548. 10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Escalera J, Chorot P, Valiente RM, Reales JM, & Sandín B (2016). Efficacy of transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in adults, children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Revista de Psicopatología Y Psicología Clínica, 21(3), 147. doi: 10.5944/rppc.vol.21.num.3.2016.17811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Pierson HM, Piasecki MP, Antonuccio DO, & Palm KM (2011). Does acceptance and relationship focused behavior therapy contribute to bupropion outcomes? A randomized controlled trial of functional analytic psychotherapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 700–715. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster AT, Gerlach AL, Hamm A,…Rief A (2015). 5HTT is associated with the phenotype psychological flexibility: Results form a randomized clinical trial. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 265, 399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00406-015-0575-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried MR (2009). Searching for therapy change principles: Are we there yet? Applied and Preventive Psychology, 13, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, & Glenn-Lawson JL (2007). Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2), 336–343. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A, Watkins E, Mansell W, & Shafran R (2004). Cognitive behavioral processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC (2019). A liberated mind: How to pivot towards what matters. New York: Avery. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC & Follette WC (1992). Can functional analysis provide a substitute for syndromal classification? Behavioral Assessment, 14, 345–365. [Google Scholar]