Abstract

The discovery of regulated trafficking of extracellular vesicles (EVs) has added a new dimension to our understanding of local and distant communication among cells and tissues. Notwithstanding the expanded landscape of EV subtypes, the majority of research in the field centers on small and large EVs that are commonly termed exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic cell-derived vesicles. In the context of pregnancy, EV-based communication has a special role in the crosstalk among the placenta, maternal and fetal compartments, with most studies focusing on trophoblastic EVs and their effect on other placental cell types, endothelial cells, and distant tissues. Many unanswered questions in the field of EV biology center on the mechanisms of vesicle biogenesis, loading of cargo molecules, EV release and trafficking, the interaction of EVs with target cells and the endocytic pathways underlying their uptake, and the intracellular processing of EVs inside target cells. These questions are directly relevant to EV-based placental-maternal-fetal communication and have unique implications in the context of interaction between two organisms. Despite rapid progress in the field, the number of speculative, unsubstantiated assumptions about placental EVs is concerning. Here we attempt to delineate existing knowledge in the field, focusing primarily on placental small EVs (exosomes). We define central questions that require investigative attention in order to advance the field.

Keywords: Placenta, trophoblasts, extracellular vesicles, exosome, trafficking

Introduction

Placental trophoblasts exquisitely regulate gas exchange, supply of nutrients, removal of waste products, hormonal support, and immunological defense, all crucial for the development and growth of the eutherian fetus. These functions are orchestrated through communication of molecular cues that are essential for pregnancy health. Until recently, the repertoire of regulatory signals was comprised of hormones (such as hCG, placental lactogens, and steroids) or growth factors (such as epidermal growth factor or and placental growth factor) [1]. The recent identification of a spectrum of extracellular vesicles (EVs), their presence in virtually all biological fluids, and their trafficking among diverse cell types [2] has offered a new dimension of signal communications, and established these EVs as a means of local or distant communication among cells and tissues.

With the recent accelerated research on EV biology, it should be noted that the concept of extracellular vesicles was introduced in the 1860’s by Charles Darwin, who proposed that every cell in the body can produce “gemmules,” which are particles of minute size that contain diverse molecules and that are communicated to other bodily cell types [3,4]. Directly relevant to pregnancy, Georg Schmorl in 1893 detailed the first evidence of placental-maternal particle trafficking in the form of fetal cells, syncytialized fragments and syncytial knots that were found in the lungs of pregnant women [5]. Exosomes were initially considered a means to remove waste cargo (“cellular debris”) from reticulocytes during their differentiation into red blood cells [6,7]. This has been suggested again, but not fully pursued, in the context of the high prevalence of tRNAs and vault RNAs within EVs [7]. Considering EVs’ ability to exploit the cell’s innate exocytosis and endocytosis pathways for transferring cellular cargo to other cells, tissues, and even organisms, they were termed “Trojan horses” [8].

The EV sphere is made of a various non-replicating cellular phospholipid membranes, and naturally forms a globular structure in aqueous solutions, optimized to minimize the water-lipid interface. EV cargos, including nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and other metabolites, are highly diverse, and depend on their cell lineage, stage of differentiation, activation, neoplastic transformation, injury or infection of the cell of origin. Similarly, their sizes and other biophysical characteristics are heterogeneous and largely underexplored. Based on thermodynamic considerations related to membrane bending, the smallest vesicles would likely measure 10–20 nm in diameter [9]. In addition to the most commonly explored EVs (commonly termed exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic cell-derived vesicles), the recent deployment of asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation technology [10] has revealed distinct populations of larger and smaller EVs, including the 35-nm-in-diameter exomeres. Large EVs, including apoptotic bodies and oncosomes [11], measure several microns in diameter. Stromal extracellular macrovesicles, also measuring several microns in diameter, where recently observed within the placental villous stroma [12]. EV properties also depend on the type of membrane phospholipids and the presence of membrane proteins. It is therefore clear that the commonly employed size-based definition of EVs, using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) or similar systems, is overly simplistic, and comprehensive analysis of EV characteristics related to vesicle biogenesis, cargo, trafficking, and targeting properties should be contemplated in order to fully appreciate their diverse functionality. Additional considerations of EV definitions and their isolation technologies, which are not the subject of this text, can be found in recent publications by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) and the Extracellular RNA Communication Consortium (ERCC1) [13–15]. As recommended by ISEV [13–15], herein we use the term EVs as a general term that defines released vesicles, and small EVs to specifically denote exosomes.

The production and release of placental EVs had been suggested nearly 15 years ago [16,17], with the subsequent isolation of placental small EVs in 2006 using size exclusion chromatography followed by purification with anti-placental-type alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) antibody by Sabapatha et al [18]. This was followed by small EV isolation directly from placental explants, cultured human trophoblasts, or trophoblast cell lines [19–23]. Interestingly, EVs are found in uterine secretions even prior to implantation [24,25]. Termed uterosomes, they have been functionally implicated in fertilization, blastocyst intercellular communication, and implantation [26–29]. Based on differential ultracentrifugation and PLAP-purification, it is estimated that the concentration of small EVs in pregnant women’s plasma in early pregnancy is on the order of 1–2 × 1011 small EVs /ml plasma, with 10–20% contributed by PLAP-positive placental small EVs [30]. These levels gradually rise until the third trimester and are largely unaffected by fetal sex and maternal BMI [31–33]. Interestingly, similar levels of EVs were recently reported in the circulation of pregnant mice [34]. A similar concentration of small EVs was also reported in fetal circulation, with approximately 45% emanating from the placenta and with no significant effects due to fetal sex or growth restriction [33].

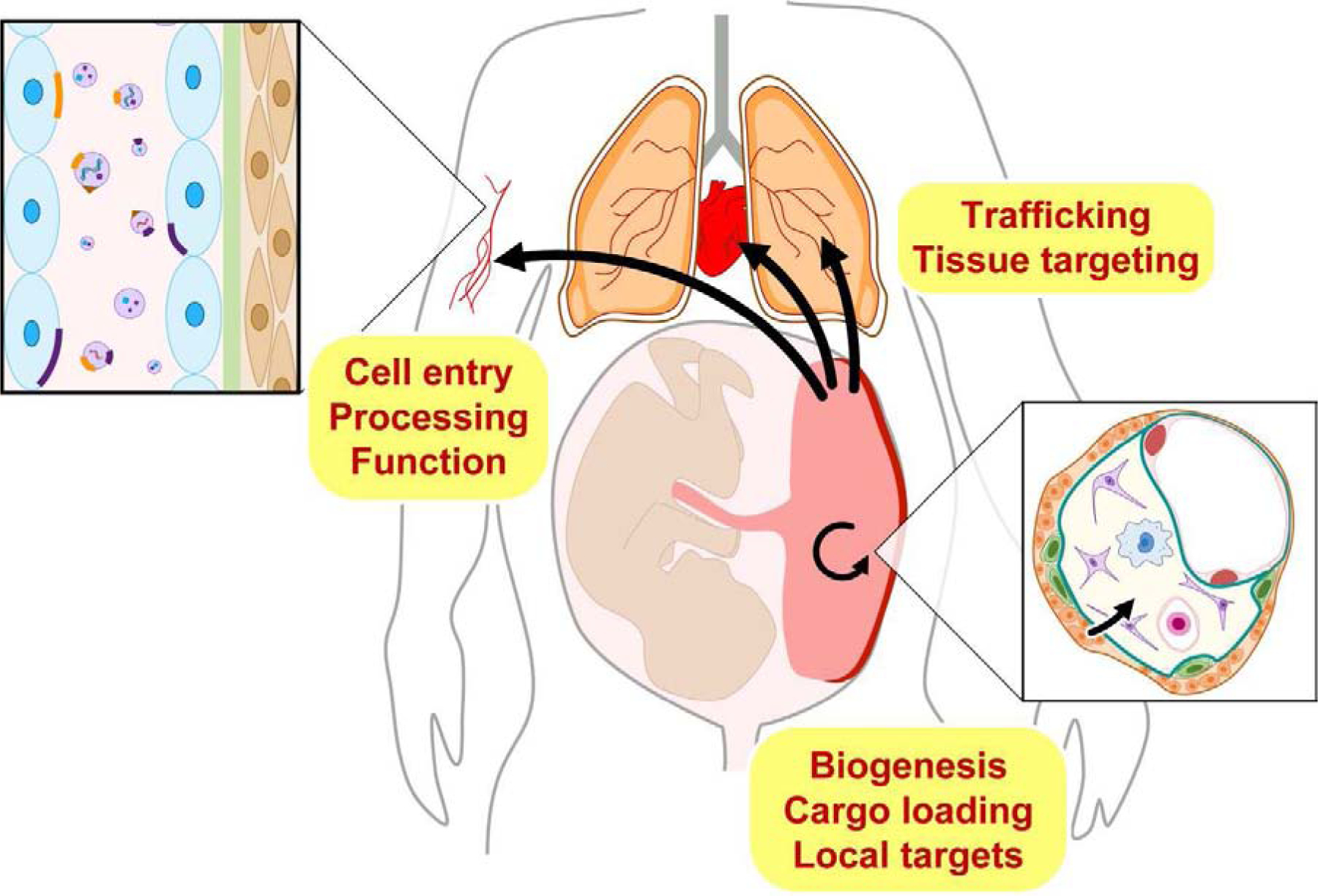

In this text, we will summarize key questions and research opportunities related to EV biology and their role in communication between trophoblasts and other cell types (Fig. 1). In accordance with the explicable ambiguity in the EV field, we focus mainly on small EVs in the broader context of EV biology. Recent reviews on exosomes as biomarkers can be found elsewhere [35–38].

Fig. 1. From biogenesis to target cell function: Key nodes in the biology of placental EVs.

Shown are key processes that should be pursued in order to elucidate the biology of trophoblastic extracellular vesicles.

Extracellular vesicle biogenesis, cargo loading, and release

Like many other cell types, placental trophoblasts produce EVs of diverse sizes [12,39,40]. While the precise mechanism of EV production by trophoblasts has not been fully elucidated, synthesis pathways implicated in other cell types, including production of small EVs by ESCRT protein–based pathways of intraluminal vesicles within multivesicular bodies, production of larger EVs by pinching off the plasma membrane, and apoptosis with surface membrane budding and cell body fragmentation [41,42], are likely to take place in trophoblasts. Whether trophoblast syncytialization affects EV biogenesis remains to be elucidated.

Recently, our understanding of the types of molecules packaged within EV cargo has been expanded and revised [43]. The cargo of trophoblastic small, medium and large EVs is variable [39], yet largely influenced by the cells of origin [44,45]. Placental small EVs are known to carry pro-apoptotic proteins such as TRAIL and Fas-ligand, cytokines, eicosanoids, growth factors, and their receptors [23,46–48]. As expected, unique placental proteins, such as PLAP, syncytin, and HLA-G, are also expressed in placental small EVs [49,50]. Akin to other tissues, placenta-derived EVs have a high concentration tRNAs [51] and microRNAs (miRNAs), including miRNAs expressed from the chromosome 19 miRNA cluster (C19MC) [22,40]. The repertoire of trophoblastic lipids has also been detailed [39]. Interestingly, discrete placental EV proteins may play a role in disease pathogenesis. For example, placental EVs from women with preeclampsia contain transthyretin, a thyroxine- and retinol-binding protein transporter, which is enriched in placental small EVs and implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia [52].

Apart from the fact that some proteins are unique to certain EV subtypes, reflecting their biosynthetic pathways, an important question in the field of EV biology centers on the possibility that certain cell-specific proteins, RNA, or lipid molecules are selectively sorted to distinct EV sub-types. The presence of such selectivity in trophoblast EVs is currently unknown. For example, several recent publications illuminated the role of RNA-binding proteins, such as YBX1, hnRNPA2B1, and HuR, in selective sorting of miRNAs into small EVs [53–57]. In contrast, using primary human villous trophoblasts, we were not able to recapitulate selective C19MC miRNA sorting into small EVs [22]. Selective sorting of proteins (for example, cytokines) has also been documented in EVs from other cell systems [58]. Whereas some of these proteins may function in their target cells, others are implicated in protecting EV cargo (such as RNA) against degradation [59]. The presence of enzymes, such as the RNA-processing DICER [60], within EVs may also suggest that processing of certain cargo molecules is ongoing during the trafficking and delivery process [60]. These exciting possibilities remain to be explored in the context of placental EVs.

EV Trafficking to specific targets

The extremely small volume for cargo within EVs implies that the mobilization of bioactive molecules to discrete target cells would depend on a most efficient trafficking and EV-specific delivery system [42,61]. This might be a smaller hurdle when EV trafficking occurs among neighboring cells but becomes a major challenge in the signal traffic to cells of distant organs. The introduction of human small EVs into mice has been used to study small EVs distribution and systemic effect in the context of physiology or diseases. An important example of the contribution of guided trafficking to disease pathogenesis is provided through the work of Lyden’s group, who demonstrated the role of various integrins in guiding small EVs trafficking, which in turn directs tumor metastatic spread [62]. Tracking small EVs in vivo usually requires their labeling with fluorescent or luminescent tracers, using lipophilic dyes or genetic tags, such as the small, (20kDa) ATP-independent nanoluciferase (NanoLuc) [63], carboxyfluorescin succinimidyl ester (CFSE) [64], or other technologies, with subsequent real-time localization using an in vivo imaging system. Several groups have used different methods to trace mouse placental small EVs or their cargo to distant maternal tissues [65,66]. Trafficking of maternal small EVs into the placenta, and even into the fetal compartment, has also been reported [66]. Within that context, it is easier to envision the trafficking of EVs from trophoblasts, which, in the hemochorial placenta, are directly bathed in the maternal blood, into the maternal circulation. Identifying pathways used by maternal small EVs to cross the placental barrier and reach the fetal compartment may be more challenging, as the basement membrane and additional cell types need to be engaged and crossed to enable that trafficking route. Deciphering these pathways is necessary in order to elucidate maternal-fetal patterns of placental EV trafficking.

EV targeting to distant “addresses” may be guided by the presence of a unique “barcode,” which may be located on the surface of small EVs or their target cells. Such a barcode may be generated by a combination of particular surface molecules, such as integrins [62] or cytokines [58], and can be recognized by a “barcode reader.” While this remains a central question in EV biology [67,68], it is likely that molecules unique to the EV donor cells may be required for specific recognition by target cells. Within that context, it has been shown that the expression of syncytin-1 and -2 is essential for the entry of trophoblastic small EVs into target cells [69]. The potential role of syncytin in EV fusion with target cells has been reviewed [70]. Deeper research into the interaction of EVs with target cells and the mechanism underlying barcode recognition will be essential for deciphering the mechanisms of EV trafficking and targeting and for EV-based therapeutics.

EV entry and impact on target cell physiology

Discrete mechanisms, such as endocytosis, fusion of EVs with the plasma membrane, and other processes, promote EV entry into target cells [42,68,71]. Some of these mechanisms may also be intertwined with cell-specific recognition systems, trigger a surface molecule “kiss and run” interaction, or interact through activation of target cell receptors [72]. The mechanisms utilized by target cells to uptake trophoblastic small EVs are largely underexplored. Limited data point to the role of phagocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the interaction of placental small EVs with endothelial cells in vitro [65].

It is generally believed that EV uptake into target cells may impact their physiology. Several recent examples in the fields of cancer, metabolism, and aging support this notion [62,73–76]. In pregnancy, trophoblastic EVs can be taken up by endothelial cells or circulating monocytes, B cells, or platelets and possibly affect their function [31,77–79]. Trophoblastic small EVs harboring C19MC miRNA attenuate viral replication in target cells via autophagy-mediated pathways [75]. Placental small EVs also attenuate mesenteric artery vasodilatory response [65].

Several immune functions are modulated by placental small EVs [80]. Maternal adaptive immunity, including impaired T-cell signaling, cytotoxicity and apoptosis are impacted by placenta-derived small EVs [81]. Placental small EVs modulate CD3, Janus kinase 3 (JAK3), and activation of caspase 3 in T-cells [18]. Human NKG2D ligands, expressed on the surface of trophoblastic small EVs, downregulate the NKG2D receptor on NK cells and CD8 T lymphocytes and modulate their cytotoxicity [20]. The miRNA miR-517a, within trophoblastic small EVs, regulates the serine/threonine kinase PRKG1 in Jurkat T-cells. [82]. Endoplasmic reticulum stress stimulates the production of EVs that contain damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules [83]. Other immunological targets of placental EVs have recently been reviewed [84].

Placental EVs and diseases during pregnancy

In general, a disease may stem from abnormal EV production and packaging by the donor cells, trafficking miscommunication, or anomalous uptake or processing by target cells. There are several examples that mechanistically link small EVs to non-gestational disease processes [85,86]. These include the role of small EVs in cancer metastasis [62,87,88], embryonic stem cell–derived small EVs in cardiac healing after myocardial infarction [85], and neurological disorders [89,90].

Placental small EVs have been recently implicated in a number of gestational disorders, largely based on the association of a disease with abnormalities in small EV number or cargo molecules. Abnormal EV number, communication, and function have been implicated in preeclampsia [91,92]. Specifically, EVs from preeclamptic placentas exhibit altered levels of Flt-1, endoglin, and syncytin-2 [69,93]; the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) has been reported to be reduced [94]; small EVs from the serum of preeclamptic patients reduce eNOS expression in target endothelial cells [95] and differentially influence platelet function [78]. The membrane-bound metalloprotease neprilysin is higher in EVs from preeclampsia [96]. Finally, EVs from injured placentas can induce a preeclampsia-like phenotype in mice [97].

In the context of diabetes in pregnancy, hyperglycemia increases small EV release by trophoblasts [98,99]. Trophoblastic EVs from patients with gestational diabetes contain more dipeptidyl peptidase IV, implicated in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes by degradation of GLP-1 [100], and miRNA in placental small EVs of patients with gestational diabetes have been implicated in reduced insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake by striated muscle cells [101].

Final thoughts

Deeper understanding of EV biology has led to an unequivocal acceptance of the presence of diverse EV types, which has been validated not only in vitro, but also in vivo, in virtually all bodily fluids. Moreover, changes in EV concentration and composition and their various effects on target cells have been associated with altered physiological and disease states. In addition, the ability of EVs to deliver bioactive molecules to target cells has been validated and explored for the development of new drug delivery approaches. The recent deployment of effective tools that allow better EV isolation, size characterization, and definition of cargo composition has helped in untangling the complexity of EV biology, enabling a deeper level of research in the field and overcoming some of the challenges related to data reproducibility.

Notwithstanding the rapid progress in the field, our understanding of EV biology, particularly as pertaining to placental EVs, is severely lacking. Key aspects of placental EVs remain enigmatic and await a more profound mechanistic investigation. First, we need to define the biological implications of trophoblastic EV diversity and the changes in EV characteristics during pregnancy and in response to gestational disorders. Second, we must define the key determinants of EV biogenesis pathways and processes underlying cargo loading and assess them during placental development and through the differentiation of cytotrophoblasts to syncytiotrophoblasts. Are changes in EV cargo relevant to placental physiology, pregnancy homeostasis or disease state, and does cargo modification underlie altered EV function? Along the same line, do trophoblasts also produce small EVs that are negative for PLAP or other markers currently known to be present in small EVs? Third, we should interrogate signals that guide EV trafficking and targeting. If selective EV targeting is proven, which surface molecules may signal an interaction between the “barcode” and the “barcode reader”? Fourth, we should define the mechanisms underlying the uptake of placental EVs by target cells, cargo processing by target cells, and the implications of these processes to the biology of pregnancy. Which cellular pathways link EV effectors (protein, RNA, and the like) to their functional machinery? Finally, better tools and animal models should be developed to define the role of EVs in health and disease during pregnancy. Can we harness knowledge derived from placental EVs to develop better biomarkers, drug delivery systems, or new therapeutics that target pregnancy-related diseases?

The field of placental EV biology should move from unproven hypotheses and weak biomarker screens to innovative mechanistic pursuits that can propel the field to the forefront of research in early development and perinatal biology.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our laboratories for valuable discussion. Our ideas and knowledge represent the work of many past and current laboratory members and of our collaborators, and we are grateful to all. We also thank Lori Rideout for assistance in manuscript preparation, and Bruce Campbell for editing.

Funding

This project was supported by NIH grants R01 HD086325 and R37 HD086916 (to Y.S.), R01 AI148690 (to A.M. and Y.S.), the Margaret Ritchie Battle Family Charitable Fund (to Y.S.), and the joint Third Xiangya Hospital/Central South University-University of Pittsburgh Scholar program (to H.L.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Napso T, Yong HEJ, Lopez-Tello J, et al. The role of placental hormones in mediating maternal adaptations to support pregnancy and lactation. Front Physiol, 9 (2018) 1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gyorgy B, Szabo TG, Pasztoi M, et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci, 68 (2011) 2667–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Darwin C. The variation of animals and plants under domestication. J. Murray: London,; 1868. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liu Y, Chen Q. 150 years of Darwin’s theory of intercellular flow of hereditary information. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 19 (2018) 749–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schmorl G. Pathologisch-anatomische Untersuchungen über Puerperal-Eklampsie. Verlag FCW: Leipzig; 1893. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, et al. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J Biol Chem, 262 (1987) 9412–9420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Buermans HP, Waasdorp M, et al. Deep sequencing of RNA from immune cell-derived vesicles uncovers the selective incorporation of small non-coding RNA biotypes with potential regulatory functions. Nucleic Acids Res, 40 (2012) 9272–9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gould SJ, Booth AM, Hildreth JE. The Trojan exosome hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 100 (2003) 10592–10597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huang C, Quinn D, Sadovsky Y, et al. Formation and size distribution of self-assembled vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 114 (2017) 2910–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat Cell Biol, 20 (2018) 332–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Di Vizio D, Morello M, Dudley AC, et al. Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am J Pathol, 181 (2012) 1573–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Palaiologou E, Etter O, Goggin P, et al. Human placental villi contain stromal macrovesicles associated with networks of stellate cells. J Anat, 236 (2020) 132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Das S, Extracellular RNACC, Ansel KM, et al. The extracellular RNA communication consortium: establishing foundational knowledge and technologies for extracellular RNA rResearch. Cell, 177 (2019) 231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Srinivasan S, Yeri A, Cheah PS, et al. Small RNA sequencing across diverse biofluids identifies optimal methods for exRNA isolation. Cell, 177 (2019) 446–462 e416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles, 7 (2018) 1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Frangsmyr L, Baranov V, Nagaeva O, et al. Cytoplasmic microvesicular form of Fas ligand in human early placenta: switching the tissue immune privilege hypothesis from cellular to vesicular level. Mol Hum Reprod, 11 (2005) 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Redman CW, Sargent IL. Circulating microparticles in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Placenta, 29 Suppl A (2008) S73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sabapatha A, Gercel-Taylor C, Taylor DD. Specific isolation of placenta-derived exosomes from the circulation of pregnant women and their immunoregulatory consequences. Am J Reprod Immunol, 56 (2006) 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Luo SS, Ishibashi O, Ishikawa G, et al. Human villous trophoblasts express and secrete placenta-specific microRNAs into maternal circulation via exosomes. Biol Reprod, 81 (2009) 717–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hedlund M, Stenqvist AC, Nagaeva O, et al. Human placenta expresses and secretes NKG2D ligands via exosomes that down-modulate the cognate receptor expression: evidence for immunosuppressive function. J Immunol, 183 (2009) 340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Atay S, Gercel-Taylor C, Suttles J, et al. Trophoblast-derived exosomes mediate monocyte recruitment and differentiation. Am J Reprod Immunol, 65 (2011) 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, et al. The expression profile of C19MC microRNAs in primary human trophoblast cells and exosomes. Mol Hum Reprod, 18 (2012) 417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fitzgerald W, Gomez-Lopez N, Erez O, et al. Extracellular vesicles generated by placental tissues ex vivo: A transport system for immune mediators and growth factors. Am J Reprod Immunol, 80 (2018) e12860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Machtinger R, Laurent LC, Baccarelli AA. Extracellular vesicles: roles in gamete maturation, fertilization and embryo implantation. Hum Reprod Update, 22 (2016) 182–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Burns GW, Brooks KE, Spencer TE. Extracellular vesicles originate from the conceptus and uterus during early pregnancy in sheep. Biol Reprod, 94 (2016) 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Greening DW, Nguyen HP, Elgass K, et al. Human endometrial exosomes contain hormone-specific cargo modulating trophoblast adhesive capacity: Insights into endometrial-embryo interactions. Biol Reprod, 94 (2016) 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Desrochers LM, Bordeleau F, Reinhart-King CA, et al. Microvesicles provide a mechanism for intercellular communication by embryonic stem cells during embryo implantation. Nat Commun, 7 (2016) 11958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bidarimath M, Khalaj K, Kridli RT, et al. Extracellular vesicle mediated intercellular communication at the porcine maternal-fetal interface: A new paradigm for conceptus-endometrial cross-talk. Sci Rep, 7 (2017) 40476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Simon C, Greening DW, Bolumar D, et al. Extracellular vesicles in human reproduction in health and disease. Endocr Rev, 39 (2018) 292–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sarker S, Scholz-Romero K, Perez A, et al. Placenta-derived exosomes continuously increase in maternal circulation over the first trimester of pregnancy. J Transl Med, 12 (2014) 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Salomon C, Torres MJ, Kobayashi M, et al. A gestational profile of placental exosomes in maternal plasma and their effects on endothelial cell migration. PLoS One, 9 (2014) e98667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu H, Kang M, Wang J, et al. Estimation of the burden of human placental micro- and nano-vesicles extruded into the maternal blood from 8 to 12 weeks of gestation. Placenta, 72–73 (2018) 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Miranda J, Paules C, Nair S, et al. Placental exosomes profile in maternal and fetal circulation in intrauterine growth restriction - Liquid biopsies to monitoring fetal growth. Placenta, 64 (2018) 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nguyen SL, Greenberg JW, Wang H, et al. Quantifying murine placental extracellular vesicles across gestation and in preterm birth data with tidyNano: A computational framework for analyzing and visualizing nanoparticle data in R. PLoS One, 14 (2019) e0218270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Salomon C, Nuzhat Z, Dixon CL, et al. Placental exosomes during gestation: Liquid biopsies carrying signals for the regulation of human parturition. Curr Pharm Des, 24 (2018) 974–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lai A, Kinhal V, Nuzhat Z, et al. Proteomics Method to Identification of Protein Profiles in Exosomes. Methods Mol Biol, 1710 (2018) 139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pillay P, Moodley K, Moodley J, et al. Placenta-derived exosomes: potential biomarkers of preeclampsia. Int J Nanomedicine, 12 (2017) 8009–8023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Salomon C, Guanzon D, Scholz-Romero K, et al. Placental exosomes as early biomarker of preeclampsia: Potential role of exosomal microRNAs across gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 102 (2017) 3182–3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ouyang Y, Bayer A, Chu T, et al. Isolation of human trophoblastic extracellular vesicles and characterization of their cargo and antiviral activity. Placenta, 47 (2016) 86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ouyang Y, Mouillet JF, Coyne CB, et al. Placenta-specific microRNAs in exosomes - good things come in nano-packages. Placenta, 35 Suppl (2014) S69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 19 (2018) 213–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, et al. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol, 21 (2019) 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, et al. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell, 177 (2019) 428–445.e418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Burkova EE, Dmitrenok PS, Bulgakov DV, et al. Exosomes from human placenta purified by affinity chromatography on sepharose bearing immobilized antibodies against CD81 tetraspanin contain many peptides and small proteins. IUBMB Life, 70 (2018) 1144–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tong M, Kleffmann T, Pradhan S, et al. Proteomic characterization of macro-, micro- and nano-extracellular vesicles derived from the same first trimester placenta: relevance for feto-maternal communication. Hum Reprod, 31 (2016) 687–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Stenqvist AC, Nagaeva O, Baranov V, et al. Exosomes secreted by human placenta carry functional Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules and convey apoptosis in activated immune cells, suggesting exosome-mediated immune privilege of the fetus. J Immunol, 191 (2013) 5515–5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Peiris HN, Vaswani K, Almughlliq F, et al. Eicosanoids in preterm labor and delivery: Potential roles of exosomes in eicosanoid functions. Placenta, 54 (2017) 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ermini L, Ausman J, Melland-Smith M, et al. A single sphingomyelin species promotes exosomal release of endoglin into the maternal circulation in preeclampsia. Sci Rep, 7 (2017) 12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Alegre E, Rebmann V, Lemaoult J, et al. In vivo identification of an HLA-G complex as ubiquitinated protein circulating in exosomes. Eur J Immunol, 43 (2013) 1933–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tolosa JM, Schjenken JE, Clifton VL, et al. The endogenous retroviral envelope protein syncytin-1 inhibits LPS/PHA-stimulated cytokine responses in human blood and is sorted into placental exosomes. Placenta, 33 (2012) 933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cooke WR, Cribbs A, Zhang W, et al. Maternal circulating syncytiotrophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles contain biologically active 5’-tRNA halves. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 518 (2019) 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tong M, Cheng SB, Chen Q, et al. Aggregated transthyretin is specifically packaged into placental nano-vesicles in preeclampsia. Sci Rep, 7 (2017) 6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shurtleff MJ, Temoche-Diaz MM, Karfilis KV, et al. Y-box protein 1 is required to sort microRNAs into exosomes in cells and in a cell-free reaction. Elife, 5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cha DJ, Franklin JL, Dou Y, et al. KRAS-dependent sorting of miRNA to exosomes. Elife, 4 (2015) e07197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Villarroya-Beltri C, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat Commun, 4 (2013) 2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Santangelo L, Giurato G, Cicchini C, et al. The RNA-binding protein SYNCRIP is a component of the hepatocyte exosomal machinery controlling microRNA sorting. Cell Rep, 17 (2016) 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Mukherjee K, Ghoshal B, Ghosh S, et al. Reversible HuR-microRNA binding controls extracellular export of miR-122 and augments stress response. EMBO Rep, 17 (2016) 1184–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Fitzgerald W, Freeman ML, Lederman MM, et al. A system of cytokines encapsulated in extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep, 8 (2018) 8973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shurtleff MJ, Yao J, Qin Y, et al. Broad role for YBX1 in defining the small noncoding RNA composition of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 114 (2017) E8987–e8995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tran N. Cancer exosomes as miRNA factories. Trends Cancer, 2 (2016) 329–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chevillet JR, Kang Q, Ruf IK, et al. Quantitative and stoichiometric analysis of the microRNA content of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 111 (2014) 14888–14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature, 527 (2015) 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Stacer AC, Nyati S, Moudgil P, et al. NanoLuc reporter for dual luciferase imaging in living animals. Mol Imaging, 12 (2013) 1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sheller-Miller S, Trivedi J, Yellon SM, et al. Exosomes cause preterm birth in mice: Evidence for paracrine signaling in pregnancy. Sci Rep, 9 (2019) 608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Tong M, Stanley JL, Chen Q, et al. Placental nano-vesicles target to specific organs and modulate vascular tone in vivo. Hum Reprod, 32 (2017) 2188–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Sheller-Miller S, Choi K, Choi C, et al. Cyclic-recombinase-reporter mouse model to determine exosome communication and function during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 221 (2019) 502.e501–502.e512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Horibe S, Tanahashi T, Kawauchi S, et al. Mechanism of recipient cell-dependent differences in exosome uptake. BMC Cancer, 18 (2018) 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DR. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J Extracell Vesicles, 3 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Vargas A, Zhou S, Ethier-Chiasson M, et al. Syncytin proteins incorporated in placenta exosomes are important for cell uptake and show variation in abundance in serum exosomes from patients with preeclampsia. FASEB J, 28 (2014) 3703–3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Record M. Intercellular communication by exosomes in placenta: a possible role in cell fusion? Placenta, 35 (2014) 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Heusermann W, Hean J, Trojer D, et al. Exosomes surf on filopodia to enter cells at endocytic hot spots, traffic within endosomes, and are targeted to the ER. J Cell Biol, 213 (2016) 173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Tkach M, Kowal J, Zucchetti AE, et al. Qualitative differences in T-cell activation by dendritic cell-derived extracellular vesicle subtypes. EMBO J, 36 (2017) 3012–3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Zhang Y, Kim MS, Jia B, et al. Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs. Nature, 548 (2017) 52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ying W, Riopel M, Bandyopadhyay G, et al. Adipose tissue macrophage-derived exosomal miRNAs can modulate in vivo and in vitro insulin sensitivity. Cell, 171 (2017) 372–384.e312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, et al. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 110 (2013) 12048–12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol, 9 (2007) 654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Saez T, de Vos P, Sobrevia L, et al. Is there a role for exosomes in foetoplacental endothelial dysfunction in gestational diabetes mellitus? Placenta, 61 (2018) 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Tannetta DS, Hunt K, Jones CI, et al. Syncytiotrophoblast extracellular vesicles from pre-eclampsia placentas differentially affect platelet function. PLoS One, 10 (2015) e0142538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Southcombe J, Tannetta D, Redman C, et al. The immunomodulatory role of syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles. PLoS One, 6 (2011) e20245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kshirsagar SK, Alam SM, Jasti S, et al. Immunomodulatory molecules are released from the first trimester and term placenta via exosomes. Placenta, 33 (2012) 982–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Mincheva-Nilsson L, Baranov V. Placenta-derived exosomes and syncytiotrophoblast microparticles and their role in human reproduction: immune modulation for pregnancy success. Am J Reprod Immunol, 72 (2014) 440–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kambe S, Yoshitake H, Yuge K, et al. Human exosomal placenta-associated miR-517a-3p modulates the expression of PRKG1 mRNA in Jurkat cells. Biol Reprod, 91 (2014) 129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Collett GP, Redman CW, Sargent IL, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress stimulates the release of extracellular vesicles carrying danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules. Oncotarget, 9 (2018) 6707–6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tong M, Abrahams VM, Chamley LW. Immunological effects of placental extracellular vesicles. Immunol Cell Biol, 96 (2018) 714–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Khan M, Nickoloff E, Abramova T, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes promote endogenous repair mechanisms and enhance cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Circ Res, 117 (2015) 52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Shah R, Patel T, Freedman JE. Circulating extracellular vesicles in human disease. N Engl J Med, 379 (2018) 958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Costa-Silva B, Aiello NM, Ocean AJ, et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol, 17 (2015) 816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Melo SA, Sugimoto H, O’Connell JT, et al. Cancer exosomes perform cell-independent microRNA biogenesis and promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell, 26 (2014) 707–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Saman S, Kim W, Raya M, et al. Exosome-associated tau is secreted in tauopathy models and is selectively phosphorylated in cerebrospinal fluid in early Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem, 287 (2012) 3842–3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Asai H, Ikezu S, Tsunoda S, et al. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat Neurosci, 18 (2015) 1584–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Chiarello DI, Salsoso R, Toledo F, et al. Foetoplacental communication via extracellular vesicles in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Mol Aspects Med, 60 (2018) 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Xiao X, Xiao F, Zhao M, et al. Treating normal early gestation placentae with preeclamptic sera produces extracellular micro and nano vesicles that activate endothelial cells. J Reprod Immunol, 120 (2017) 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Tannetta DS, Dragovic RA, Gardiner C, et al. Characterisation of syncytiotrophoblast vesicles in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia: expression of Flt-1 and endoglin. PLoS One, 8 (2013) e56754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Motta-Mejia C, Kandzija N, Zhang W, et al. Placental vesicles carry active endothelial nitric oxide synthase and their activity is reduced in preeclampsia. Hypertension, 70 (2017) 372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Shen L, Li Y, Li R, et al. Placenta associated serum exosomal miR155 derived from patients with preeclampsia inhibits eNOS expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J Mol Med, 41 (2018) 1731–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Gill M, Motta-Mejia C, Kandzija N, et al. Placental syncytiotrophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles carry active NEP (neprilysin) and are increased in preeclampsia. Hypertension, 73 (2019) 1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Han C, Wang C, Chen Y, et al. Placenta-derived extracellular vesicles induce preeclampsia in mouse models. Haematologica, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Salomon C, Scholz-Romero K, Sarker S, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with changes in the concentration and bioactivity of placenta-derived exosomes in maternal circulation across gestation. Diabetes, 65 (2016) 598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Rice GE, Scholz-Romero K, Sweeney E, et al. The effect of glucose on the release and bioactivity of exosomes from first trimester trophoblast cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 100 (2015) E1280–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Kandzija N, Zhang W, Motta-Mejia C, et al. Placental extracellular vesicles express active dipeptidyl peptidase IV; levels are increased in gestational diabetes mellitus. J Extracell Vesicles, 8 (2019) 1617000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Gillet V, Ouellet A, Stepanov Y, et al. miRNA profiles in extracellular vesicles from serum early in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 104 (2019) 5157–5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]