Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been threatening the globe since the end of November 2019. The disease revealed cracks in the health care system as health care providers across the world were left without guidelines on definitive usage of pharmaceutical agents or vaccines. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on the 11th of March 2020. Individuals with underlying systemic disorders have reported complications, such as cytokine storms, when infected with the virus. As the number of positive cases and the death toll across the globe continue to rise, various researchers have turned to cell based therapy using stem cells to combat COVID-19. The field of stem cells and regenerative medicine has provided a paradigm shift in treating a disease with minimally invasive techniques that provides maximal clinical and functional outcome for patients. With the available evidence of immunomodulatory and immune-privilege actions, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can repair, regenerate and remodulate the native homeostasis of pulmonary parenchyma with improved pulmonary compliance. This article revolves around the usage of novel MSCs therapy for combating COVID-19.

Abbreviations: ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; BM-MSC, Bone marrow derived MSC; CCL2, C–C motif chemokine ligand 2; CD146, Cluster of differentiation 146; CD200, Cluster of differentiation 200; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; DC, Dendritic cells; HGF, Hepatocyte growth factor; IL-1Ra, Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; ISSCR, International Society for Stem Cell Research; MACoVIA, MultiStem administration for COVID-19 induced ARDS; MIF, Macrophage migration inhibitory factor; MODS, Multi-organ dysfunction syndrome; MSCs, Mesenchymal stem cells; P-MSC, Placenta derived MSC; SARS, Severe acute respiratory syndrome; SIRS, Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; STAT3, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; SVF, Stromal vascular fraction; TGF-β, Transforming Growth Factor beta; UC-MSC, Umbilical cord derived MSC; WHO, World Health Organization

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, WHO, Mesenchymal stem cells

1. Introduction

The first known case of COVID-19 was recorded on the 1st of December 2019 in the city of Wuhan, China as pneumonia of unknown aetiology. Soon, there was a surge of similar cases [1]. This sudden emergence was initially attributed to the seasonal flu. However, later investigatory findings of the point of outbreak uncovered a newer aetiology. The famous Hunan Seafood Market was found as the point of outbreak and the virus was suggested to have a zoonotic origin [2,3]. Some reports that showed the doubling of cases every 7.5 days suggested that this virus was highly contagious [4]. On January 1st 2020, a common aetiological agent was found in four out of the total nine hospitalised patients. This newly emerged strain of coronavirus has a hereditary correlation of 5% with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and is a subclass of Sarbecovirus [1]. The virus was named SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes is called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as per the World Health Organization (WHO). On the 30th of January 2020, the WHO declared an International Public Health Emergency due to the rampant spread of COVID-19 around the world. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 was declared as a pandemic by the WHO on the 11th of March 2020. As a result, all clinicians and researchers from various disciplines of biomedicine have come together in search of a definitive therapy to combat this pandemic effectively [5].

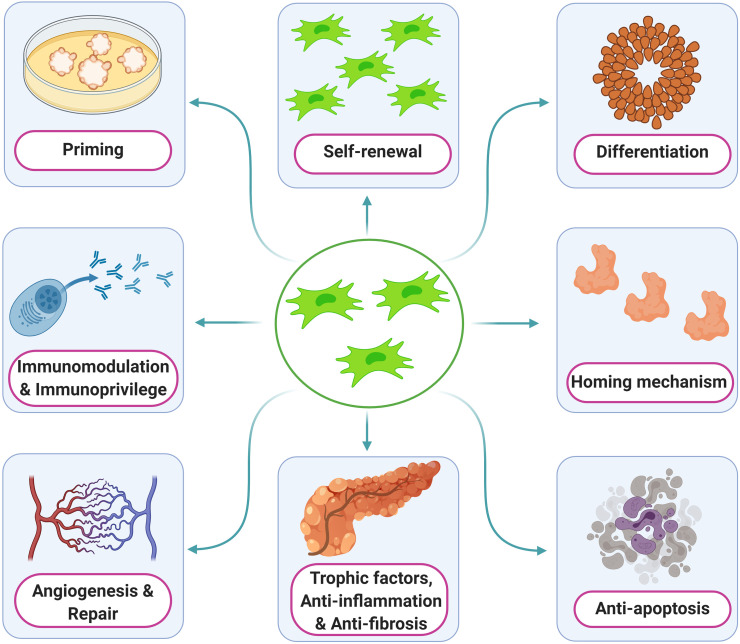

Researchers around the globe have greatly explored the potential uses of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in repairing damaged regions and in re-establishing regional homeostasis. MSCs are immature heterogeneous population of stromal progenitor cells. They possess the property of self-renewal, plasticity, lineage priming and homing, and differentiation of native environment cells [6]. MSCs can take on the properties of a particular lineage or shift into another lineage under the influence of growth factors, cytokines and chemokines [7].

The purpose of our article is to highlight recent developments of pathogenesis of COVID-19, with a particular focus on Stem Cells. This article also summarizes the usage of novel MSCs therapy for combating COVID-19. Our article updates the current status clinical trials of MSCs in COVID-19.

1.1. MSCs and Immunomodulation

MSCs possess unique non-differentiating cell surface markers such as CD146 and CD200 [8,9] and expresses matrix and MSC markers such as CD 105, CD 44, CD 29, CD 71 and CD 73 [10]. They serve as an immunotolerant and immunomodulant cell in damaged tissues. They help regenerate and rejuvenate the environment [11] by exerting their effects on T cells, B cells, Dendritic cells, and macrophages.

1.1.1. T cells and MSCs

MSCs produce their immunomodulatory action on T cells through any of the following three mechanisms:

-

1.

Inhibition of T Cell proliferation: It is a well-known fact that T cell mediated immunity plays a key protective role against various autoimmune disorders, malignancies, and infections [12]. Baboon MSCs, however, inhibit the proliferation of T cells [13]. Similar results have been seen in in-vitro human bone marrow MSCs. By arresting T-cells at the G1 phase via TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor beta) and HGF (Hepatocyte growth factor), MSCs inhibit the proliferation of T cells [14,15].

-

2.

Apoptosis of T cells: Apoptosis of activated T cells is mediated by Fas/Fas ligand-dependent pathway with the production of kynurenine from tryptophan [16,17].

-

3.

Modulation of activation and differentiation of T cells: MSCs induce the production of IL-10 and inhibit the production of both IFN-γ and IL-17. Therefore, they reduce production of regulatory T-cells. They also regulate dendritic cells and natural killer cells [[18], [19], [20]].

-

4.

Anti-inflammatory: MSCs induce the production of IL-1Ra and IL-1β, which anticipates the anti-inflammatory effects and proceeds to heal such damaged tissues [21].

-

5.

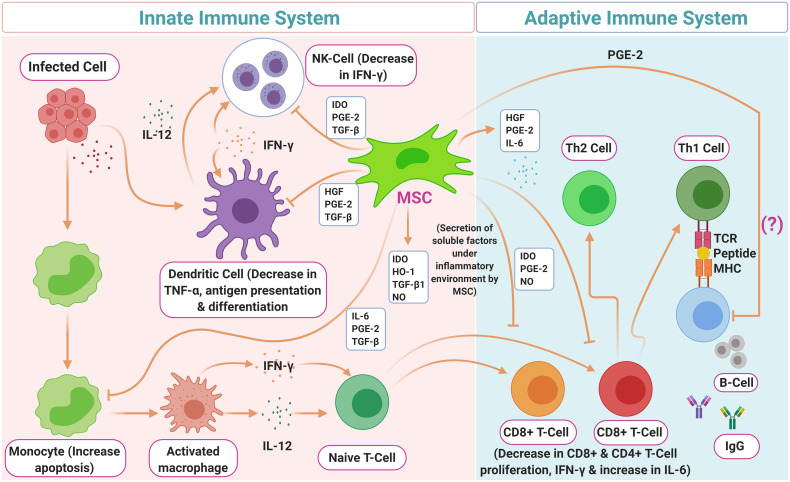

Immunomodulatory: The immunomodulatory potential of MSCs is triggered when they are stimulated by the inflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, inter-leukin (IL-) 1α, or IL-1β, which leads to the production of Nitrous oxide (NO) and Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) via upregulation of iNOS and COX-2 (as shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ) [[22], [23], [24]].

Fig. 1.

Secretion and modulation of cytokines by mesenchymal stem cells and their roles in T cell differentiation and inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Various roles of mesenchymal stem cells.

1.1.2. B cells and MSCs

The effect of MSCs on B cells is mediated by CCL-2 via STAT3 inactivation and PAX5 induction. As a result, MSCs go on to cause:

-

1.

Arrest of cell cycle

-

2.

Inhibition of plasma cell production

-

3.

Impaired immunoglobulin secretion

-

4.

Reduced chemotaxis

-

5.

Production of IL-1Ra (Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) to control B cell differentiation and progression of arthritis

-

6.

Extracellular vesicles, which are derived from MSCs, to suppress B cell proliferation, differentiation, and immunoglobulin production

-

7.

Induction of regulatory B cells which in turn produces IL-10 (Anti-inflammatory) [[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]].

1.1.3. Dendritic cells and MSCs

Dendritic cells (DC) are the main antigen presenting cells. MSCs are known to exert immunosuppressive effects on dendritic cells by [33,34]:

-

1.

Inhibiting DC activation

-

2.

Decreasing endocytosis

-

3.

Decreasing IL-12 production

-

4.

Cell maturation arrest

-

5.

Inhibiting formation of dendritic cells from monocytes

-

6.

Skewing mature DCs into an immature state

1.1.4. Macrophages and MSCs

Macrophages can be separated into M1 macrophages that produce various pro inflammatory molecules to combat the microbes and M2 macrophages that are involved in tissue regeneration because of their immunomodulatory action via the production of IL-10 [35]. MSCs have the potential to augment macrophage regenerative activity at the site of injury [36]. When MSCs are cultured with macrophages, they differentiate into M2 macrophages which will lead to high levels of anti-inflammatory IL-10 and low levels of pro-inflammatory molecules [37]. MSC's interaction with macrophages can combat local inflammation by both increasing IL-10 and by decreasing the production of TNF-α and IL-6 [38].

1.1.5. Natural killer cells and MSCs

Natural killer cells play a key role in the elimination and cytotoxicity of tumor cells and viral infected cells. High ratios of MSCs to NK cells restrain NK cell proliferation, production of proinflammatory molecules, and cytotoxicity. These effects are mediated by IDO, PGE2, HLA-5, and EVs. Blocking these molecules can reverse the effects of MSCs [[39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]].

1.1.6. Neutrophils and MSCs

Neutrophils play a key role in acute inflammation. MSCs have the capacity to interact with neutrophils to suppress apoptosis of resting neutrophils (IL-6 mediated) and to increase recruitment of neutrophils (via IL-8 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor-MIF) [45,46]. Furthermore, Superoxide dismutase 3 mediated inhibition of uncontrolled inflammation in a murine vasculitis model demonstrates the anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs which decreases tissue damage [46]. MSC derived micro vesicles have been shown to inhibit migration of neutrophils into the pulmonary parenchyma of mice in E-coli endotoxin medicated acute lung injury [47].

As is evident from the above discussion, MSCs have the innate ability to interact with almost all immune cells. Their action is either mediated through the various growth and immunomodulatory factors or through direct cell-cell contact. Due to their immunomodulatory properties, they have been used in many immune-mediated diseases for their known interaction with NK cells, polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, T and B cells [[48], [49], [50], [51]].

2. Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Nidovirales order, a member of the genus β-coronavirus (β-CoV) [21]. It is an encapsulated, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus (nucleocapsid) with a 79.6% similar sequence to SARS-CoV and accounts for having the largest genomic specifications among RNA viruses [51].

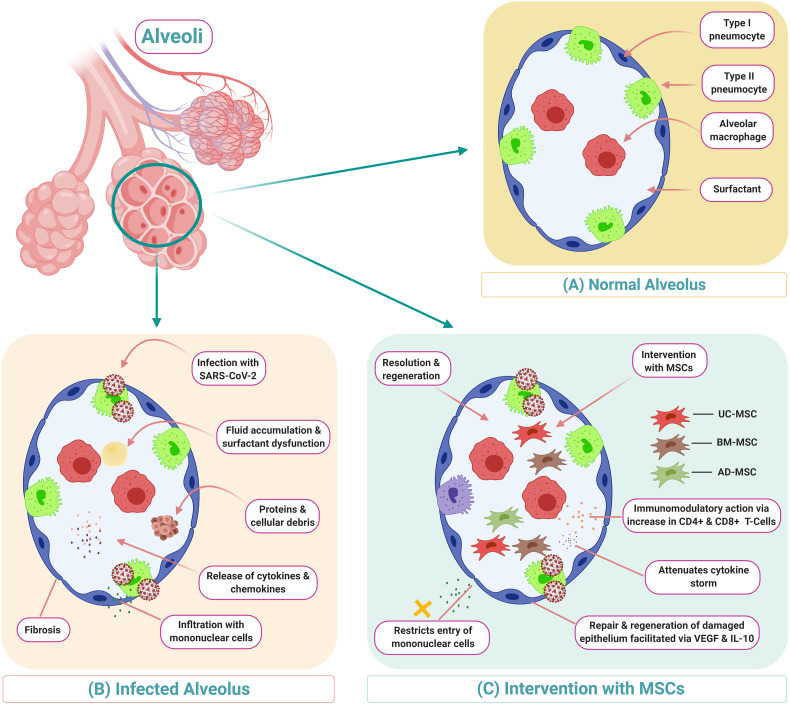

With the help of ACE-2 receptors, this virus gets access into pulmonary alveolar cells. ACE-2 receptors are found not only in the pulmonary epithelium but also in renal, cardiac and liver parenchymal cells, which explains the reason for development of multi organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) that often presents in the late stages of COVID-19 [52]. With the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the pulmonary parenchyma, it undergoes replication, transcription and translation of viral proteins and gets assembled in the Golgi apparatus. By exocytosis, millions of the newly assembled viral bodies leave the infected cell and infect the new pulmonary epithelium. The exocytosis causes further epithelial and endothelial damage that leads to increased vascular permeability inside the pulmonary environment. As a result of these events, initiation of a ‘cytokine storm’ leads to secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-α, TNF-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-8, IL-33, and TGF-β) [53]. The mechanism of the cytokine storm leads to increased mortality in patients with systemic debilitating illnesses. As a result of the cytokine storm, the patient develops acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and death. The immune-inflammatory mechanism leads to damage of pulmonary epithelium at a cellular level as depicted in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Description of COVID-19 and possible MSC therapy intervention including a demonstration of MSC's immunomodulatory actions.

3. mesenchymal stem cells in COVID-19

Amidst the COVID-19 rush for various vaccines and drugs, like Hydroxychloroquine and Remdesivir, some researchers have turned to MSCs as a new avenue for treating COVID-19. At present, cell-based therapy, and stem cell therapy, in particular, is a ground-breaking medical area with great potential to cure incurable diseases [54]. MSCs have drawn interest due to their source, high rate of proliferation, minimally intrusive treatment protocols, and lack of ethical problems. Furthermore, MSC rehabilitation is significantly better in comparison to that of other therapies. It is useful in the treatment of COVID-19 for the following reasons:

-

1.

COVID-19 causes a depletion of the CD4 and CD8 T Cells. MSCs can help in remodelling the function of these immune cells and thus improve pulmonary function.

-

2.

MSCs can decrease the cytokine storm via inhibition of T and B cell proliferation and through effective regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines to improve the microenvironment for endogenous repair.

-

3.

Gene expression profiles have shown that the therapeutic effects of MSCs are long lasting and actively maintained.

Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have recently approved the use of MSCs for coronavirus treatment under the discretion of expanded access. The choice of MSCs to be administered is assessed via the availability and accessibility of MSCs. Among all the available sources of stem cells, the usage of MSCs from bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and placenta are well documented in the literature and will be further discussed in this article.

3.1. Bone marrow derived MSC (BM-MSC)

BM-MSCs are versatile in nature, are easily accessible, and require less technical prowess to procure. BM-MSCs possess enhanced osteogenic and chondrogenic potentiality [55]. In bone marrow, after density gradient centrifugation, the yield of progenitor cell accounts for up to 0.001% to 0.01% [56]. Although the yield of progenitor cells is low, the quality of progenitor cells remain preserved with all properties of MSCs. These BM-MSCs can be cultured in vitro to exponentially increase the concentration of progenitor cells and can be transplanted to the site of action.

3.2. Adipose derived MSC (AD-MSC)

The beginning of the 21st century marked the addition of adipose derived stem cell to the adult stem cell population. The mesoderm-derived adipose tissue is ubiquitously present in the subcutaneous plane and comprises of a plethora of cells. The stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of adipose tissues is considered the warehouse of MSC-like cells [57]. The cellular components of SVF mixture have the property of multi lineage differentiation and can differentiate along the mesenchymal lineage [58]. These cells are easily accessible [59]. Furthermore, isolation of these MSCs requires minimal manipulation (mechanical centrifugation followed by filtration or by either automatic or manual enzymatic digestion).The SVF mixture has a higher yield of nucleated cells (2%) than other sources, such as bone marrow (0.001–0.004%) [60]. However, due to the presence of various components of cells in SVF mixture, the use of SVF in allogenic clinical setting is questionable.

3.3. Umbilical cord derived MSC (UC-MSC)

Due to the consideration of umbilical cord as a medical waste, the collection of MSC from UC needs no ethical approval [61]. Global researchers are interested in the umbilical cord blood for its stem cell property. The four forms of stem cells identified in UC are [62]:

-

1)

Whole UC-MSCs

-

2)

UCWJ (Wharton jelly), UCA (artery) and UCV (vein) MSCs (obtained as a result of mincing after removing umbilical vessels)

-

3)

UC lining and subamnion-derived MSCs

-

4)

UC perivascular stem cells (UCPVC)

UC-MSCs are faster at self-renewal and differentiation than bone marrow derived MSCs [63]. The immunomodulatory effect of UC-MSCs is due to secretion of galectin-1, HLA-G5 and PGE2 molecules. The isolation of MSC-like cells from UC follows either explant culture or enzymatic digestion with collagenases and hyaluronidases. UC-MSCs are used widely in the fields of bone and cartilage regeneration as well as neurological and hepatocytic disorders.

3.4. Placenta derived MSC (P-MSC)

An immuno-regulatory organ, the placenta maintains feto-maternal interface. The placental stem cells are amnion MSC, chorion MSC, chorionic villi MSC, and decidua MSC [64]. Due to its primitive origin, placental stem cells possess higher differentiative potential than other sources of stem cells [65]. These cells also display very low immunogenicity in both in-vivo and in-vitro studies as they are from an immunoprivileged organ. P-MSCs can be used for autologous and allogenic preparation. They represent more homogeneous and primitive population of cells with homing and priming potential. They have a high proliferative rate in culture than BM-MSCs [66]. P-MSCs are safe in regenerating a tissue as they possess low telomerase activity. P-MSCs are widely used in treating cancer, neurological diseases, and critical limb ischemia [66].

3.5. Other sources of MSCs

Synovium derived MSC-like cells (S-MSC) are found in the surface, the stroma, and the perivascular region of synovial lining [67]. S-MSCs have a higher propensity for osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation [68].

Menstrual blood derived MSC (Mens-MSC) can be harvested from monthly endometrial shedding and has the greatest capacity for self-renewal and differentiation [69]. Mens-MSC possesses pluripotent cellular (Oct-4, SSEA-4, nanog, and c-kit) and MSC markers (CD9, CD29, CD44).

4. Clinical trials of MSCs in COVID-19

MSCs have drawn attention among global researchers in treating COVID-19. A pilot study was conducted by Leng and colleagues on MSC transplantation for seven positive cases of SARS-CoV-2 [70]. They transplanted 1 × 106 clinical-grade MSCs per kilogram of body weight intravenously and followed up with various haematological and pulmonary compliance protocols for 2 weeks of MSC therapy. They observed a significant clinical improvement in pulmonary compliance. This pilot study also reported that MSCs are not infected by SARS-CoV-2 as they lack ACE-2 and TMPRSS-2 receptors. The pneumonic consolidation disappeared on the post-treatment CT imaging. MSC treated patients showed negative results for COVID-19 nucleic acid test 1.5 weeks average post treatment. Liang and colleagues also treated one critically ill 65-year-old patient with 3 doses 5 × 107 allogeneic human umbilical cord MSC intravenously. The patient showed a good clinical response without any major adverse side effects [71].

Currently, there are a total of 69 trials that have been registered for MSC therapy in COVID-19. Out of 69 registered trials, only 29 trials are in recruiting status (Table 1 ). Three clinical trials have already been completed (NCT04288102, NCT04492501, NCT04276987) but the results are not available yet. The summary of these 3 trials are as follows

-

1.

NCT04288102: A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in China on 100 hospitalised patients with RT-PCR proven COVID-19 status to evaluate the efficacy and safety of human umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with pneumonia. The experimental group received 3 does of UC-MSCs intravenously at Day 0, Day 3, Day 6 and control group received Saline containing 1% Human serum albumin.

-

2.

NCT04492501: A non-randomized interventional clinical trial with factorial assignment intervention model conducted in Pakistan with 600 participants to evaluate the role of investigational therapies alone or in combination to treat moderate, severe and critical COVID-19. The trial had 3 experimental arms: Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) arm, TPE with other investigational treatment (ex: convalescent plasma, tocilizumab, Remdesivir, MSC therapy), and a combination of, or single use of, tocilizumab, Remdesivir and MSCs.

-

3.

NCT04276987: An interventional single-arm clinical trial conducted in Shanghai, China with 24 participants to explore the safety and efficiency of aerosol inhalation of the exosomes derived from allogenic adipose mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of severe patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. The experimental arm received conventional treatment and 5 times aerosol inhalation of MSCs-derived exosomes for 5 days continuously. Time to clinical improvement and adverse reactions were the primary outcome measures.

Table 1.

Clinical trials of MSCs in COVID-19.

| Trial no | Title of the study | Place | Intervention | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04313322 | Treatment of COVID-19 patients using Wharton's jelly MSCs | Jordan | Biological: Wharton jelly derived MSC | I |

| NCT04444271 | MSC infusion for COVID-19 infusion | Pakistan | Drug: MSCs Other: Placebo |

II |

| NCT04336254 | Safety and efficacy study of allogenic human dental pulp MSCs to treat severe COVID-19 patients | China | Biological: Allogeneic human dental pulp stem cells Other: Intravenous saline injection |

I/II |

| NCT04416139 | MSCs for acute respiratory distress syndrome due for COVID-19 | Mexico | Biological: Infusion IV of MSCs | II |

| NCT04366323 | Clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of intravenous administration of allogeneic adult MSCs of expanded adipose tissue in patients with severe pneumonia due to COVID-19 | Spain | Drug: Allogeneic and expanded adipose tissue-derived MSCs | I/II |

| NCT04252118 | MSCs treatment for pneumonia patients infected with COVID-19 | China | Biologicals: MSCs | I |

| NCT04437823 | Efficacy of intravenous infusions of stem cells in the treatment of COVID-19 patients | Pakistan | Drug: Intravenous infusion of stem cells | II |

| NCT04339660 | Clinical research of human MSCs in the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia | China | Biological: UC-MSCs Other: Placebo |

I/II |

| NCT04366063 | MSC therapy for SARS-CoV-2 related acute respiratory distress syndrome | Iran | Biological: Cell therapy protocol 1 and 2 | II/III |

| NCT04355728 | Use of UC-MSCs for COVID-19 patients | United States | Biological: Umbilical cord MSCs + heparin along with best supportive care. Other: Vehicle + heparin along with best supportive care |

I/II |

| NCT04392778 | Clinical use of stem cells for the treatment of COVID-19 | Turkey | Biological: MSC treatment Biological: Saline control |

I/II |

| NCT04331613 | Safety and efficacy of CAStem for severe COVID-19 associated with/without ARDS | China | Biological: CAstem | I/II |

| NCT04371393 | MSCs in COVID-19 ARDS | United States | Biological: Remestemcel-L Drug: Placebo |

III |

| NCT04390139 | Efficacy and safety evaluation of MSCs for the treatment of patients with respiratory distress due to COVID-19 | Spain | Drug: XCEL-UMC-BETA Other: Placebo |

I/II |

| NCT03042143 | Repair of acute respiratory distress syndrome by stromal cell administration | United Kingdom | Biological: Human umbilical cord derived CD362 enriched MSCs Biological: Placebo (Plasma-Lyte 148) |

I/II |

| NCT04361942 | Treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with allogeneic MSCs | Spain | Biological: Mesenchymal stromal cells Other: Placebo |

II |

| NCT04269525 | Umbilical cord (UC)-derived MSCs treatment for the 2019 novel coronavirus | China | Biological: UC-MSCs | II |

| NCT04333368 | Cell therapy using umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in SARS-CoV-2 related ARDS | France | Biological: Umbilical cord Wharton's jelly-derived human Other: NaCl 0.9% |

I/II |

| NCT04389450 | Double-blind, multicenter, Study to evaluate the efficacy of PLX PAD for the treatment of COVID-19 | United States | Biological: PLX-PAD Biological: Placebo |

II |

| NCT04367077 | MultiStem administration for COVID-19 induced ARDS | United States | Biological: MultiStem Biological: Placebo |

II/III |

| NCT04535856 | Therapeutic study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of DW-MSC in COVID-19 patients | Indonesia | Drug: allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell Other: Placebo |

I |

| NCT04537351 | The mesenchymal COVID-19 trial: a pilot study to investigate early efficacy of MSCs in adults with COVID-19 | Australia | Biological: CYP-001 | I/II |

| NCT04565665 | Cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of COVID-19 related acute respiratory distress syndrome | United States | Biological: Mesenchymal stem cell | I |

| NCT04348435 | A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to determine the safety and efficacy of hope biosciences allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapy to provide protection against COVID-19 | United States | Drug: HB-adMSCs Drug: Placebos |

II |

| NCT04315987 | NestaCell® mesenchymal stem cell to treat patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia | Brazil | Biological: NestaCell® Biological: Placebo |

II |

| NCT04371601 | Safety and effectiveness of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of pneumonia of coronavirus disease 2019 | China | Drug: Oseltamivir Drug: Hormones Device: Oxygen therapy Procedure: Mesenchymal stem cells |

I |

| NCT04339660 | Clinical research of human mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia | China | Biological: UC-MSCs Other: Placebo |

I/II |

| NCT04355728 | Use of UC-MSCs for COVID-19 patients | United States | Biological: Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells + heparin along with best supportive care. Other: Vehicle + heparin along with best supportive care |

I/II |

| NCT04348461 | Battle against COVID-19 using mesenchymal stromal cells | Spain | Drug: Allogeneic and expanded adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells | II |

| NCT04377334 | Mesenchymal stem cells in inflammation-resolution programs of coronavirus disease 2019 induced acute respiratory distress syndrome | Germany | Biological: MSC | II |

| NCT04437823 | Efficacy of intravenous infusions of stem cells in the treatment of COVID-19 patients | Pakistan | Biological: Intravenous infusions of stem cells | II |

The details of the other trials are listed in the below table (https://clinicaltrials.gov/).

4.1. Clinical trial results of MSCs in acute lung diseases

For a variety of lung disorders (acute lung injury, pneumoconiosis, post lung transplant, radiation induced lung injury, COVID-19 pneumonia, ARDS, asthma, COPD, interstitial lung disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis), the several groups across the globe have investigated the usage of mesenchymal stem cells to curb the disease pathology. A total of 69 clinical trials were enrolled in clinical trials register and the research on the particular diseases was carried out. Out of 69 clinical trials, only 2 trials have published the results thus far and details are given in Table 2 . Of the 8 participants enrolled in NCT01385644, no patients experienced adverse effects of the two infusion amounts. Both groups were also able to walk a greater distance (104% of baseline) in 6 min, 6 months after MSC infusion. Other outcomes measured included FVC and DLCO. The study was limited by its sample size. The NCT02097641 study noted that one dose of MSC is safe for patients with moderate to severe ARDS. Concentrations of angiopoietin 2, a predictor of poor outcomes in ARDS patients, were significantly lower after MSC infusion. While oxygen contented was measured, it was not statistically different from the placebo group. The study was limited by its sample size [72].

Table 2.

Mesenchymal stem cells usage in lung disorders.

| Disease pathology | NCT number | Title | Source of stem cells & route of delivery | Dose of MSCs | Results analysed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis | NCT01385644 (Phase 1) | A study to evaluate the potential role of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Allogenic placental derived mesenchymal stem cells & IV route | Group 1: 1 × 106 MSC/kg for 4 patients Group 2: 2 × 106 MSC/kg for 4 patients |

Immediately after 4 h of infusion, no serious adverse effects were noted. After 6 months of infusion, forced vital capacity, 6 minute distance walk and DCLO were analysed in both the groups |

| ARDS | NCT02097641 (Phase 2) | Human mesenchymal stromal cells for acute respiratory distress syndrome (START) | Allogenic bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells & IV route over 60–80 min | Group 1: Single dose of 10 million cells/kg predicted body weight for 40 patients Group 2: Single dose of plasmalyte injection for 20 patients |

Within 6 h of infusion, both the groups were analysed for transfusion related complications and hypoxemia. After 24 h, all the patients were assessed for mortality. The secondary parameters of PaO2:FiO2, SOFA score, lung injury score, oxygenation index, number of ventilator free days, IL-6 & 8, angiopoietin 2 and non-pulmonary organ failure days were analysed in both the groups. |

5. Ethical concern with MSCs

Stem cells are a ray of hope in many diseases but their efficacy and safety profile are of utmost concern [73]. Regulating the use of these cellular products was an uphill task that the US FDA started to work on in 1993. Currently, many regulatory bodies like the US FDA, International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), and USP are working on establishing guidelines for MSC therapy.

The US FDA, through section 351 of Public Health Service (PHS), regulates these biological products [73] and categorizes the cultured cells into two categories named: “minimally manipulated” and “more than minimally manipulated” [74]. If the processing of cells/tissues does not alter its biological characteristics, it is considered “minimal manipulation”. Section 361 provides the criteria for minimal manipulation of human cellular and tissue based therapies or products (HCT/Ps) [73]. Density-gradient separation, cell selection, centrifugation, and cryopreservation constitute minimal manipulation. Whereas, more-than-minimal manipulations include cell activation, encapsulation, ex-vivo expansion, and gene modifications. Pre-market review is not necessary for minimally manipulated products.

According to 21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 1271.10, cellular products with minimal manipulation, chosen for homologous administration and not combined with any other articles (except for preservation and storage) are regulated by section 361 of the PHS act. If they do not qualify for exceptions under 21 CFR 1271.10 and 1271.15, they are regulated as a drug, device, or a biologic product under section 351 of the PHS act [73].

6. Discussion

Being anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and regenerative in nature, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown the capacity to control immune dysfunction and inflammation. After intravenous infusion, MSCs are entrapped in the lung vasculature before they enter other organ systems. Therefore, they may be effective in treating lung diseases. There are various mechanisms by which MSCs can be used to treat bronchial asthma, ARDS, chronic obstruction lung disease, and interstitial lung diseases [75,76]. The safety and efficacy of MSCs in human application have been confirmed through small- and large-scale clinical trials. MSCs can home to the site of injury in ARDS and repair the damage via secretion of paracrine factors such as keratinocyte growth factor, angiopoietin-1, and prostaglandin E2 that can further improve MSC migration and tissue repair especially through direct MSC interaction [77]. The MSCs can also promote alveolar fluid clearance, membrane permeability, and reduce inflammation. There is also a direct transfer of mitochondria by MSCs to increase ATP concentrations to reactivate the alveolar cells [78]. Areas for future study include improving homing of MSC to damaged lung tissue.

In the context of COVID-19, MSCs are not affected by the COVID-19 infection as per the noteworthy ACE2− and TMPRSS2− gene expression profiling of these cells [70]. As a result, they can be used to therapy of tissues that are affected. Furthermore, MSCs attenuate the cytokine storm induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines, restrict mononuclear entry into alveolar cells, and clear the alveolar oedematous fluid as shown in Fig. 3. MSCs can regenerate the damaged alveolar epithelium and improve pulmonary compliance.

There are ways to improve MSC therapy for COVID-19. Researchers have noticed that pre-conditioning the stem cells to the environment (hypoxic, ischemic environments), can improve the function and survival of the stem cells when transplanted into the area of injury [79]. Experimental methods, such as culturing of MSCs in spheroids (approximately 500 μM) for short periods of time (3 days) can improve the adhesion of stem cells to their environments via increased expression of CXCR4 [80]. Finding the optimal conditions, such as size of spheroid and incubation periods, can improve the use of MSC therapy in COVID-19. Treatment of MSCs with drugs and supplements such as Vitamin E can help counteract injury of MSCs [81]. Understanding dosages of drugs and supplements can also help MSC activity and protection.

7. Limitations

Implementation of MSCs as a treatment for COVID-19 has a few limitations. They are as follows:

-

1.

Standardization of isolation and harvesting protocols

-

2.

Dose, frequency, and route of MSC delivery

-

3.

Autologous or allogenic preparation protocols

-

4.

Ethical concern in selection and utility among wide array of sources of mesenchymal stem cells

-

5.

Randomized controlled trials to be conducted with aforementioned sources of mesenchymal stem cells.

Furthermore, further study into MSCs and their mechanism in immune regulation is required for better homing of MSCs as well as efficacy at site of damage. Unfortunately, high doses of MSC have been noted to increase risk of hypercoagulability and organ failure. As a result of the side-effects of MSCs, researchers are looking into modifying the MSC to improve its efficacy. Researchers are looking into use of the cytokine products, or the MSC secretome, to improve potency, production capability, storage, specificity of use, and to reduce costs. Of note, the MSC derived exosomes are particularly interesting as they are easy to produce and store while having comparable therapeutic efficacy as that to MSC administration. While research is still in its infancy, there are multiple different methods of embracing the MSC capabilities that can be further explored [82].

8. Conclusion

The field of stem cells and regenerative medicine has galvanized global researchers with a ray of hope for treating various disorders with minimally invasive procedures. Due to their multipotent nature and high differentiation potential, MSCs, can be used to treat severely ill COVID-19 pneumonia patients. However, to reiterate, the safety and efficacy of MSCs for curbing pneumonia in COVID-19 patients have to be tested in large randomized controlled trials before full implementation to win the battle against COVID-19.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank the Sharda University senior management for encouragement and facility. P.H.R acknowledged NIH for funding various projects (R01AG042178, R01AG47812, R01NS105473, AG060767, AG069333 and AG66347). Authors sincerely thank Ms. Hallie Morton for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G., Hu Y., Tao Z.W., Tian J.H., Pei Y.Y., Yuan M.L., Zhang Y.L., Dai F.H., Liu Y., Wang Q.M., Zheng J.J., Xu L., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y.Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhonghua L., Xing B., Xue Z., Zhi A., Liuxingbingxue Z. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2020;41:145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K.-W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C.-Y., Poon R.W., Tsoi H.W., Lo S.K., Chan K.H., Poon V.K., Chan W.M., Ip J.D., Cai J.P., Cheng V.C., Chen P.H. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qun L., Xuhua G., Peng W., Xiaoye W., Lei Z., Yeqinget T., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metcalfe S.M. Mesenchymal stem cells and management of COVID-19 pneumonia. Medicine in Drug Discovery. 2020:100019. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeyaraman M., Somasundaram S., Anudeep T.C., Ajay S.S., Kumar V.V., Jain R., Khanna M. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) as a novel therapeutic option for nCOVID-19—a review. Open Journal of Regenerative Medicine. 2020;9:20–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeyaraman M., Ranjan R., Kumar R., Arora A., Chaudhary D., Ajay S.S., Jain R. Cellular therapy: shafts of light emerging for COVID-19. Stem Cell Investig. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.21037/sci-2020-022. (PMID: 32695804; PMCID: PMC7367471) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojewski M.T., Weber B.M., Schrezenmeier H. Phenotypic characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from various tissues. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2008;35(3):168–184. doi: 10.1159/000129013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng-Juan L., Tuan S.R., Cheung M.C.K., Victor Y.L.L. Concise review: the surface markers and identity of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1408–1419. doi: 10.1002/stem.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maleki M., Ghanbarvand F., Behvarz M M.R., Ejtemaei M., Ghadirkhomi E. Comparison of mesenchymal stem cell markers in multiple human adult stem cells. Int J Stem Cells. 2014;7(2):118–126. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2014.7.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss A.R.R., Dahlke M.H. Immunomodulation by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): mechanisms of action of living, apoptotic, and dead MSCs. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1191. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimeloe S., Burgener A.V., Grahlert J., Hess C. T-cell metabolism governing activation, proliferation and differentiation; a modular view. Immunology. 2017;150(1):35–44. doi: 10.1111/imm.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartholomew A., Sturgeon C., Siatskas M., Ferrer K., McIntosh K., Patil S., Hardy W., Devine S., Ucker D., Deans R., Moseley A., Hoffman R. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lym- phocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Nicola M., Carlo-Stella C., Magni M., Milanesi M., Longoni P.D., Matteucci P., Grisanti S., Gianni A.M. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferationinduced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99(10):3838–3843. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glennie S., Soeiro I., Dyson P.J., Lam E.W., Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood. 2005;105(7):2821–2827. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plumas J., Chaperot L., Richard M.J., Molens J.P., Bensa J.C., Favrot M.C. Mesenchymal stem cells induce apoptosis of activated T cells. Leukemia. 2005;19(9):1597–1604. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akiyama K., Chen C., Wang D., Xu X., Qu C., Yamaza T., Cai T., Chen W., Sun L., Shi S. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-induced immunoregulation involves FAS-ligand-/FAS-mediated T cell apoptosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(5):544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luz-Crawford P., Kurte M., Bravo-Alegria J., Contreras R., Nova-Lamperti E., Tejedor G., Noel D., Jorgensen C., Figueroa F., Djouad F., Carrion F. Mesenchymal stem cells generate a CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell population during the differentiation process of Th1 and Th17 cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(3):65. doi: 10.1186/scrt216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selmani Z., Naji A., Zidi I., Favier B., Gaiffe E., Obert L., Borg C., Saas P., Tiberghien P., Rouas-Freiss N., Carosella E.D., Deschaseaux F. Human leukocyte antigen-G5 secretion by human mesenchymal stem cells is required to suppress T lymphocyte and natural killer function and to induce CD4(+)CD25(high) FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):212–222. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Consentius C., Akyuz L., Schmidt-Lucke J.A., Tschope C., Pinzur L., Ofir R., Reinke P., Volk H.D., Juelke K. Mesenchymal stromal cells prevent allostimulation in vivo and control checkpoints of Th1 priming: migration of human DC to lymph nodes and NK cell activation. Stem Cells. 2015;33(10):3087–3099. doi: 10.1002/stem.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao F., Chiu S.M., Motan D.A.L., Zhang Z., Chen L., Ji H.-L., Tse H.-F., Fu Q.-L., Lian Q. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(1) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren G.W., Zhang L.Y., Zhao X., Xu G.W., Zhang Y.Y., Roberts A.I., Zhao R.C., Shi Y.F. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren G.W., Zhao X., Zhang L.Y., Zhang J.M., L’Huillier A., Ling W.F., Roberts A.I., Le A.D., Shi S.T., Shao C.S., Shi Y.F. Inflammatory cytokine-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in mesenchymal stem cells are critical for immunosuppression. J. Immunol. 2010;184(5):2321–2328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crop M.J., Baan C.C., Korevaar S.S., Ijzermans J.N., Pescatori M., Stubbs A.P., van Ijcken W.F., Dahlke M.H., Eggenhofer E., Weimar W., Hoogduijn M.J. Inflammatory conditions affect gene expression and function of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162(3):474–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corcione A., Benvenuto F., Ferretti E., Giunti D., Cappiello V., Cazzanti F., Risso M., Gualandi F., Mancardi G.L., Pistoia V., Uccelli A. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107(1):367–372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabera S., Perez-Simon J.A., Diez-Campelo M., Sanchez-Abarca L.I., Blanco B., Lopez A., Benito A., Ocio E., Sanchez-Guijo F.M., Canizo C., San Miguel J.M. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells on the viability, proliferation and differentiation of B-lymphocytes. Haematologica. 2008;93(9):1301–1309. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Che N., Li X., Zhou S., Liu R., Shi D., Lu L., Sun L. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells suppress B-cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell. Immunol. 2012;274(1–2):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asari S., Itakura S., Ferreri K., Liu C.P., Kuroda Y., Kandeel F., Mullen Y. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress B-cell terminal differentiation. Exp. Hematol. 2009;37(5):604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafei M., Hsieh J., Fortier S., Li M., Yuan S., Birman E., Forner K., Boivin M.N., Doody K., Tremblay M., Annabi B., Galipeau J. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived CCL2 suppresses plasma cell immunoglobulin production via STAT3 inactivation and PAX5 induction. Blood. 2008;112(13):4991–4998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luz-Crawford P., Djouad F., Toupet K., Bony C., Franquesa M., Hoogduijn M.J., Jorgensen C., Noel D. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived interleukin 1 receptor antagonist promotes mac- rophage polarization and inhibits B cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2016;34(2):483–492. doi: 10.1002/stem.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Trapani M., Bassi G., Midolo M., Gatti A., Kamga P.T., Cassaro A., Carusone R., Adamo A., Krampera M. Differential and transferable modulatory effects of mesenchymal stromal cell- derived extracellular vesicles on T, B and NK cell functions. Sci Rep. 2006;6:24120. doi: 10.1038/srep24120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franquesa M., Mensah F.K., Huizinga R., Strini T., Boon L., Lombardo E., DelaRosa O., Laman J.D., Grinyo J.M., Weimar W., Betjes M.G., Baan C.C., Hoogduijn M.J. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells abrogate plasma- blast formation and induce regulatory B cells independently of T helper cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(3):880–891. doi: 10.1002/stem.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W., Ge W., Li C., You S., Liao L., Han Q., Deng W., Zhao R.C. Effects of mesenchymal stem cells on differentiation, maturation, and function of human monocyte- derived dendritic cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13(3):263–271. doi: 10.1089/154732804323099190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang X.X., Zhang Y., Liu B., Zhang S.X., Wu Y., Yu X.D., Mao N. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2005;105(10):4120–4126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glass C.K., Natoli G. Molecular control of activation and priming in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17(1):26–33. doi: 10.1038/ni.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaturvedi P., Gilkes D.M., Takano N., Semenza G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent signaling between triple-negative breast cancer cells and mesenchymal stem cells promotes macrophage recruitment. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(20):E2120–E2129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406655111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selleri S., Bifsha P., Civini S., Pacelli C., Dieng M.M., Lemieux W., Jin P., Bazin R., Patey N., Marincola F.M., Moldovan F., Zaouter C., Trudeau L.E., Benabdhalla B., Louis I., Beausejour C., Stroncek D., Le Deist F., Haddad E. Human mesenchymal stromal cell-secreted lactate induces M2-macrophage differentiation by metabolic reprogramming. Oncotarget. 2016;7(21):30193–30210. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Q.Z., Su W.R., Shi S.H., Wilder-Smith P., Xiang A.P., Wong A., Nguyen A.L., Kwon C.W., Le A.D. Human gingiva- derived mesenchymal stem cells elicit polarization of M2 macrophages and enhance cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. 2010;28(10):1856–1868. doi: 10.1002/stem.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aggarwal S., Pittenger M.F. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105(4):1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spaggiari G.M., Capobianco A., Becchetti S., Mingari M.C., Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK- cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107(4):1484–1490. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sotiropoulou P.A., Perez S.A., Gritzapis A.D., Baxevanis C.N., Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24(1):74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spaggiari G.M., Capobianco A., Abdelrazik H., Becchetti F., Mingari M.C., Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2008;111(3):1327–1333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu M.M., Cui J., Zhu J., Ma Y.H., Yuan X., Shi J.M., Guo D.Y., Li C.Y. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells sup- press NK cell recruitment and activation in PolyI:C-induced liver injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;466(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michelo C.M., Fasse E., Van Cranenbroek B., Linda K., van der Meer A., Abdelrazik H., Joosten I. Added effects of dexamethasone and mesenchymal stem cells on early natural killer cell activation. Transpl Immunol. 2016;37:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raffaghello L., Bianchi G., Bertolotto M., Montecucco F., Busca A., Dallegri F., Ottonello L., Pistoia V. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit neutrophil apoptosis: a model for neutrophil preservation in the bone marrow niche. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):151–162. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang D., Muschhammer J., Qi Y., Kugler A., de Vries J.C., Saffarzadeh M., Sindrilaru A., Beken S.V., Wlaschek M., Kluth M.A., Ganss C., Frank N.Y., Frank M.H., Preissner K.T., Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Suppression of neutrophil-mediated tissue damage—a novel skill of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2016;34(9):2393–2406. doi: 10.1002/stem.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu Y.G., Feng X.M., Abbott J., Fang X.H., Hao Q., Monsel A., Qu J.M., Matthay M.A., Lee J.W. Human mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles for treatment of Escherichia coli endotoxin- induced acute lung injury in mice. Stem Cells. 2014;32(1):116–125. doi: 10.1002/stem.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y., Chen X., Cao W., Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15(11):1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/ni.3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munir H., McGettrick H.M. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for autoimmune disease: risks and rewards. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(18):2091–2100. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frenette P.S., Pinho S., Lucas D., Scheiermann C. Mesenchymal stem cell: keystone of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and a stepping-stone for regenerative medicine. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:285–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pal M., Berhanu G., Desalegn C., Kandi V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): an update. Cureus. 2020;12(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., Chen H.-D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.-D., Liu M.-Q., Chen Y., Shen X.-R., Wang X., Zheng X.-S., Zhao K., Chen Q.J., Deng F., Liu L.-L., Yan B., Zhan F.-X., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Shi Z.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwata-Yoshikawa N., Okamura T., Shimizu Y., Hasegawa H., Takeda M., Nagata N. TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 2019;93(6):e01815–e01818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01815-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pittenger M.F., Mackay A.M., Beck S.C., Jaiswal R.K., Douglas R., Mosca J.D., Moorman M.A., Somonetti D.W., Craig S., Marshak D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golchin A., Farahany T.Z. Biological products: cellular therapy and FDA approved products. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2019;15(2):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12015-018-9866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu L., Liu Y., Sun Y., Wang B., Xiong Y., Lin W., Wei Q., Wang H., He W., Wang B., Li G. Tissue source determines the differentiation potentials of mesenchymal stem cells: a comparative study of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Stem Cell Res.Ther. 2017;8:275. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0716-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuk P.A., Zhu M., Mizuno H., Huang J., Futrell J.W., Katz A.J., Benhaim P., Lorenz H.P., Hedrick M.H. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Minteer D., Marra K.G., Rubin J.P. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: biology and potential applications. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2012:59–71. doi: 10.1007/10_2012_146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strem B.M., Hicok K.C., Zhu M., Wulur I., Alfonso Z., Schreiber R.E., Fraser J.K., Hedrick M.H. Multipotential differentiation of adipose tissue- derived stem cells. Keio. J. Med. 2005;54:132–141. doi: 10.2302/kjm.54.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gentile P., Calabrese C., Angelis B.D., Pizzicannella J., Kothari A., Garcovich S. Impact of the different preparation methods to obtain human adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction cells (AD-SVFs) and human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs): enzymatic digestion versus mechanical centrifugation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;2:20(21). doi: 10.3390/ijms20215471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Secco M., Zucconi E., Vieira N.M., Fogaça L.L., Cerqueira A., Carvalho M.D., Jazedje T., Okamoto O.K., Muotri A.R., Zatz M. Multipotent stem cells from umbilical cord: cord is richer than blood! Stem Cells. 2008;26:146–150. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagamura-Inoue T. H He, umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells: their advantages and potential clinical utility. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6(2):195–202. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macias M.I., Grande J., Moreno A., Dominguez I., Bornstein R., Flores A.I. Isolation and characterization of true mesenchymal stem cells derived from human term decidua capable of multilineage differentiation into all 3 embryonic layers. Am. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010;203(5):495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.045. (e9-23) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fong C.Y., Chak L.L., Biswas A., Tan J.H., Gauthaman K., Chan W.K., Bongso A. Human Wharton’s jelly stem cells have unique transcriptome profiles compared to human embryonic stem cells and other mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Torre P.D.L., Pérez-Lorenzo M.J., Flores A.I. IntechOpen; 2018. Human Placenta-derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Review From Basic Research to Clinical Applications, Stromal Cells - Structure, Function, and Therapeutic Implications. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sakaguchi Y., Sekiya I., Yagishita K., Muneta T. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues: superiority of synovium as a cell source. ArthritisRheum. 2005;52(8):2521–2529. doi: 10.1002/art.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mizuno M., Katano H., Mabuchi Y., Ogata Y., Ichinose S., Fujii S., Otabe K., Komori K., Ozeki N., Koga H., Tsuji K., Akazawa C., Muneta T., Sekiya I. Specific markers and properties of synovial mesenchymal stem cells in the surface, stromal, and perivascular regions. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0870-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Faramarzi H., Mehrabani D., Fard M., Akhavan M., Zare S., Bakhshalizadeh S., Manafi A., Kazemnejad S., Shirazi R. The potential of menstrual blood-derived stem cells in differentiation to epidermal lineage: A preliminary report. World J. Plast. Surg. 2016;5(1):26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leng Z., Zhu R., Hou W., Feng Y., Yang Y., Han Q., et al. Transplantation of ACE2- mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Aging Dis. 2020;11(2):216–228. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liang B., Chen J., Li T., Wu H., Yang W., Li Y., Li J., Yu C., Nie F., Ma Z., Yang M., Xiao M., Nie P., Gao Y., Qian C., Hu M. Clinical remission of a critically ill COVID-19 patient treated by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(31) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matthay M.A., Calfee C.S., Zhuo H., Thompson B.T., Wilson J.G., Levitt J.E., Rogers A.J., Gotts J.E., Wiener-Kronish J.P., Bajwa E.K., Donahoe M.P., McVerry B.J., Ortiz L.A., Exline M., Christman J.W., Abbott J., Delucchi K.L., Caballero L., McMillan M., McKenna D.H., Liu K.D. Treatment with allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (START study): a randomised phase 2a safety trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019;7(2):154–162. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30418-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deasy M.B., Anderson J.E., Zelina S. Intech Open; 2013. Regulatory Issues in the Therapeutic Use of Stem Cells. Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Torre M.L., Lucarelli E., Guidi S., Ferrari M., Alessandri G., Girolamo L.D., Pessina A., Ferrero I., Messenchimali G.T.S. Ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stromal cell minimal quality requirements for clinical application. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(6):677–685. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Akram K.M., Samad S., Spiteri M., Forsyth N.R. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy and lung diseases. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2013;130:105–129. doi: 10.1007/10_2012_140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Inamdar A.C., A.A. Inamdar AA. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in lung disorders: pathogenesis of lung diseases and mechanism of action of mesenchymal stem cell. Exp. Lung Res. 2013;39(8):315–327. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2013.816803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhao A., Pan Y., Cai S. Patient-specific cells for modeling and decoding amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: advances and challenges. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020;16(3):482–502. doi: 10.1007/s12015-019-09946-8. 31916190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Han J., Liu Y., Liu H., Li Y. Genetically modified mesenchymal stem cell therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):386. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1518-0. (PMID: 31843004; PMCID: PMC6915956) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chrzanowski W., Kim S., McClements L. Can stem cells beat COVID-19: advancing stem cells and extracellular vesicles toward mainstream medicine for lung injuries associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartosh T., Ylostalo J., Mohammadipoor A., Bazhanov N., Coble K., Claypool K., Lee R., Choi H., Prockop D. Aggregation of human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) into 3D spheroids enhances their antiinflammatory properties. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(31):13724–13729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008117107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hu C., Li L. Preconditioning influences mesenchymal stem cell properties in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017;22(3):1428–1442. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eiro N., Cabrera J.R., Fraile M., Costa L., Vizoso F.J. The coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2): new problems demand new solutions, the alternative of mesenchymal (stem) stromal cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:645. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00645. (PMID: 32766251; PMCID: PMC7378818) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]