Abstract

Problem

In an era of increasing complexity, leadership development is an urgent need for academic health science centers (AHSCs). The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and others have described the need for a focus on organizational leadership development and more rigorous evaluation of outcomes. Although the business literature notes the importance of evaluating institutional leadership culture, there is sparse conversation in the medical literature about this vital aspect of leadership development. Defining the leadership attributes that best align with and move an AHSC forward must serve as the foundational framework for strategic leadership development.

Approach

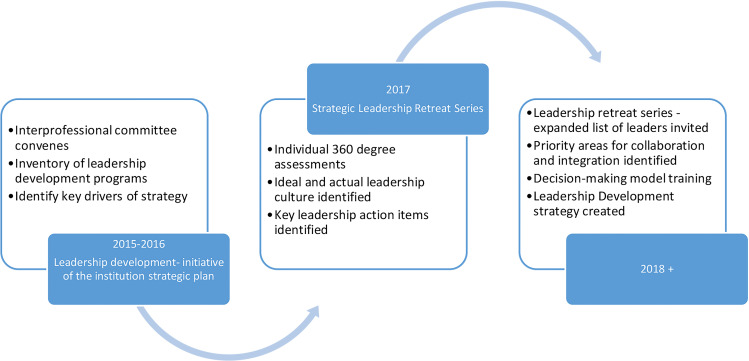

In 2015, the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) began a systematic process to approach strategic leadership development for the organization. An interprofessional group completed an inventory of our leadership development programs and identified key drivers of a new institutional strategic plan. A strategic leadership advisory committee designed a series of leadership retreats to evaluate both individual and collective leadership development needs.

Outcomes

Three key drivers were identified as critical attributes for the success of our institutional strategy. Four specific areas of focus for the growth of the institution’s ideal leadership culture were identified, with specific action items or behaviors developed for our leaders to model. As a result of this foundational work, we have now launched the MUSC Leadership Institute.

Next Steps

Knowledge of our current leadership culture, key drivers of strategy and our desired collective leadership attributes are the basis for building our institutional leadership development strategy. This will be a longitudinal process that will start with senior leadership engagement, organizational restructuring, new programming and involve significant experimentation. Disciplined, thoughtful evaluation will be required to find the right model. In addition to individual transformation with leadership development, MUSC will measure specifically identified strategic outcomes and performance metrics for the institution.

Keywords: key drivers, strategic development, collective efficacy, collaboration, courageous authenticity, interprofessional

Plain Language Summary

Academic health science centers (AHSCs) face an increasing number of challenges and many professional societies and other groups have described the clear need for effective leadership of these organizations. While individual leaders can learn and apply new skills, the development of an ideal leadership culture is thought to be vital for the continued success of the AHSCs. The authors describe their institution’s approach to strategic organizational leadership development and call for a shift in focus away from individual-centric leadership and towards the development of a common, organizational leadership culture and viewpoint. This approach included senior leadership buy-in starting with their own 360-degree evaluations, defining leadership collectively, and taking an inventory of institution leadership development opportunities to evaluate organizational leadership culture in preparation for the leadership culture shift.

Leadership Development – An Urgent Need

Leadership development is described as an urgent need for academic health science centers (AHSCs) in response to the multiple pressures on the traditional tripartite mission of education, research and patient care. Major changes in the funding mechanisms of these missions began in the 1990s and continue today. The role of technology has continued to expand and rapidly evolve. There is an explosion of information with the ensuing struggle to translate discoveries into patient outcomes in all health-care fields. Historically, AHSC leadership has been based on the concept of the individual leadership attributes and viewpoint that may or may not align with, and benefit, the overall function of the organization. This has led to a highly siloed, and sometimes fractious institutional leadership structure that often makes AHSCs less effective and more wasteful than their most innovative business counterparts.1,2 Digital transformation with big data, the internet of things, and artificial intelligence are transforming medicine and science as we speak.2 In this new environment, high-quality patient care delivery, health-care education, and transformational research require multidisciplinary teams capable of functioning across historical structures and boundaries to be effective.1,2 All of these point to the clear need for AHSC leadership to transform from an individual-centric culture to a strategic organizational leadership culture in order to envision, build and support what is required to fully step into the future. Perhaps for these reasons, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) noted the need for new roles for physician (arguably all) leaders, enhanced profiles of department chairs and the need to focus on organizational leadership to lead academic health systems into a new era.3

For decades the AHSC community has encouraged the development of leaders and more rigorous, outcomes-based evaluation of programs. Although the role of organizational context has been emphasized, and the need for collective leadership training voiced, there has been little conversation in the medical literature about the importance of evaluating and enabling the leadership culture of an institution.4,5

Culture is defined as “the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization”.6 There is an abundance of work in the health-care field studying the influence of the “Culture of Safety” on patient outcomes, and the concept of a “Just Culture” is widely used.7,8 A primary role of leadership is that of defining and influencing the culture of an organization, but this can be a daunting task particularly in rapidly changing and complex systems like AHSCs.

Collective organizational efficacy is part of organizational culture and is defined as a group’s belief that it can work together in commitment to the organization’s mission, demonstrating resiliency when facing challenges. Leadership promoting collective efficacy facilitates positive outcomes as demonstrated in research findings regarding schools, business organizations and athletic teams.9 Assessing collective efficacy can assist in evaluating whether projected goals are attained, but there are few published descriptions of such assessments in AHSCs.

A Strategic Approach to Leadership Development

Establishing a Baseline

The only integrated academic health science center in the state, the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) encompasses colleges of medicine, nursing, dentistry, health professions (allied health), pharmacy and graduate studies and the MUSC Health system. In 2015, MUSC unveiled a new institutional strategic plan with five goal areas (Figure 1), and actionable priorities were outlined for each. Under the goal, “Foster Innovative Education and Learning” was the priority initiative: “Identify and develop leadership development opportunities (both curricula and developmental experiences) across entities, levels and functions.” A team of interprofessional leaders from all of MUSC’s colleges and the health system (Leadership Development Team) came together to launch this initiative and discern next steps to enhance strategic leadership development for the organization.

Figure 1.

MUSC strategic plan graphic.

MUSC has defined leadership not as a position, but as a set of value-based behaviors and skills intentionally applied to create impact to drive strategic outcomes, foster influence of and service to others and to drive innovation. Transformational leadership, a style that can inspire others and encourage action, is thought to be a requirement for MUSC’s success. Leadership development in this context is centered on an institutional competency model that emphasizes both the role of personal development and that of effective interaction with other people and systems to create desired results.

The Leadership Development Team first created an inventory of leadership development programs across the organization. Areas of strength and gaps in opportunities were identified. Because the field of leadership development is broad, and the activities resource-intensive, the identification of key drivers of institutional strategy is a necessary component to creating programs of measurable value to the institution. Utilizing a blueprint to create leadership development within organizations, the group then identified these key drivers.4 The Leadership Development Committee reached several conclusions after review of the inventory of leadership development programs across the organization:

Many of these programs targeted specific roles or locations.

The majority focused on the operational versus strategic functions of leadership and individual development training.

All except one were siloed in colleges or departments.

The key drivers of our new institutional strategy identified for MUSC:

Innovation: Our leaders need to be more innovative.

Integration: Our leaders need to demonstrate integration of the three missions in their operations and goals.

Inspire a shared vision: Our leaders need to envision the future by imagining exciting and ennobling possibilities and enlist others in a common vision by appealing to shared aspirations.

Determining the Strategy

In 2017, we began a series of leadership retreats with the most strategic enterprise leaders identified by the President and the CEO of MUSC Health (Table 1). Each of the 35 leaders completed an external 360-degree assessment (The Leadership Circle©),10 and reviewed the results of surveys by employees on engagement with and connection to the institutional strategic plan. Research, academic and diversity and inclusion metrics were also reviewed. Ideal leadership characteristics were elicited from a wide variety of leaders across the enterprise, and over 100 institutional leaders were surveyed formally about MUSC’s leadership culture (The Leadership Culture Survey©). A series of leadership retreats designed to evaluate both individual and collective leadership development needs were organized.

Table 1.

Strategic Leadership Retreat Attendance MUSC January 2017, by Role

| MUSC | President |

|---|---|

| MUSC | Executive Vice President, Finance & Operations |

| MUSC | Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs & Provost |

| MUSC | Chief Information Officer |

| MUSC | Chief Communications & Marketing Officer |

| MUSC | Legislative Liaison |

| MUSC | Systems Controller |

| MUSC | General Counsel |

| MUSC | Chief Institutional Strategy Officer; Associate Provost for Educational Affairs and Student Life |

| MUSC | Vice President, Development & Alumni Affairs |

| MUSC University | Dean, College of Graduate Studies |

| MUSC University | Dean, College of Health Professions |

| MUSC University | Dean, College of Dental Medicine |

| MUSC University | Dean, College of Medicine |

| MUSC University | Dean, College of Nursing |

| MUSC University | Dean, College of Pharmacy |

| MUSC University | Vice President for Research |

| MUSC University | Chief Diversity Officer |

| MUSC University | Assistant Provost for Institutional Effectiveness |

| MUSC University | Director, Legal Affairs |

| MUSC Health | Chief Operating Officer |

| MUSC Health | Chief Financial Officer |

| MUSC Health | President, MUSC Physicians |

| MUSC Health | General Counsel, MUSC Physicians |

| MUSC Health | Chief Physician Executive |

| MUSC Health | Chief Medical Officer |

| MUSC Health | CEO, MUSC Health & Vice President Health Affairs |

| MUSC Health | Chief of Staff |

| MUSC Health | Chief Diversity Officer |

| MUSC Health | Executive Chief Nursing Officer & Chief Patient Experience Officer |

| MUSC Health | Chief People Officer |

| MUSC Health | Chief Quality Officer |

| MUSC Health | Chief Medical Officer, MUSC Physicians |

| MUSC Health | Chief Strategy Officer |

| MUSC Health | Chief Perioperative Officer |

Abbreviation: MUSC, enterprise-wide role.

The internally developed survey on MUSC’s strategy was sent to leaders, including lower and middle leadership, across the enterprise prior to the leadership retreats, in both 2015 and 2016, with sample sizes of 1424 and 1385 in respective years. The majority of respondents agreed that understanding organizational strategy helps employees perform their jobs better, and there were needs identified in both the communication of the strategy and confidence in the credibility of leaders to execute. Research and academic metrics tracked and reviewed included: national percentile rank in research and development expenditures, percentile rank in National Institutes of Health (NIH) award amount, percentage of graduating students that agree they received a high-quality education, percentage of faculty rated by students as effective teachers, and mean first time examinee pass rate on all licensing exams. Press Ganey© employee engagement data from the preceding year for both the health system and the university were also reviewed for trends. MUSC Diversity and Inclusion goals evaluated included activities and metrics around institutional leadership, patient care, workforce and processes/policy.

The Leadership System© is a proprietary group of aligned surveys that includes a 360-degree individual review (The Leadership Circle) and The Leadership Culture Survey. Both tools give feedback on the behavioral dimensions of relating, self-awareness, authenticity, systems awareness, achieving, controlling, protecting and complying as perceived by self and others and compared to a global norm. For individuals, coaching around these results can give insight into areas for development. Similarly, for groups of leaders, a gap between ratings in each dimension between the “ideal” and “actual” culture forms the basis for leadership groups to establish a purposeful change in behaviors and norms – thus to shape the culture of the organization.

After an analysis by the group of 35 leaders over two retreats, the gap between our current collective leadership culture and the ideal was explored with the goal of developing specific action items or behaviors for our leaders to model. When taken together, the 360 leader assessments revealed strongly creative leadership tendencies with a balance between managing relationships and tasks. There was also a tight correlation between results and self-assessment. The collective leadership culture results leaned more heavily towards reactive tendencies with larger gaps between actual and ideal behaviors. The specific action items and behaviors identified by the 35 leaders were:

Collaboration and Integration: how we become a more seamless institution among our three-part mission of education, research and patient care.

Courageous Authenticity: Our culture needs to be one that is bold enough to invite diverse ideas, opinions and conversations. Diversity in thought and approach is what will make us excel as an institution.

Decision-making Processes and Accountability: We are a large organization with many layers. While protocol is important, too often decisions are made without clear follow-up, implementation plans and/or accountability.

Communication: How can we be more intentional about highlighting ongoing work, addressing concerns and cascading important messages more effectively? Furthermore, leadership communication addressing longitudinal issues affecting the institution needs to occur more effectively.

Because of this process, it was clear to our group that MUSC needed leadership development in the strategic realm, and collective leadership in order to address the key drivers of our strategy. To do this would involve broad agreement by all of our strategic leaders on the purpose behind an investment in leadership development and an understanding of the leadership culture needed for our institution to succeed.

Over the remainder of 2017, subsequent retreats witnessed an expansion of invited leaders, the development of priority areas for collaboration and integration, and training on the use of a decision-making model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MUSC institutional leadership development process.

Instituting Culture Change

There are many elements critical to enabling fundamental change in the culture of an organization beyond leadership development. It is important to briefly describe other aspects of an ongoing multidimensional change process at our institution which provides new institutional leadership opportunities and enables sustainable leadership culture change. Using our key drivers of our new institutional strategy we have actively restructured many elements of our enterprise as part of integration. We also invested in new transformation technologies and programs to enable a more integrated, innovative, and inspirational organization that is institutionally focused with new collaborative leadership opportunities developed in the process. Significant examples are highlighted in Table 2 Instituting Cultural Change. Furthermore, we have focused on integrated communications and marketing to better inform our internal and external audiences.

Table 2.

Instituting Cultural Change

| Effort (Type) | Description | Key Strategy Driver |

|---|---|---|

| Create integrated clinical centers of excellence (restructure) | Single physician leader with administrative support – provides new patient focused clinical care delivery and interface with departmental model for academic interface | Integration |

| Clinical funds flow/responsibility centered management (restructure) | Transparent, mission-aligned financial model for increased accountability and integration | Integration |

| Information technology (IT) support fully integrated (restructure) | IT management centralized and accountable to all three missions of the enterprise through an IT governance council | Integration |

| Institutional advocacy committee (restructure) | Create a unified institutional legislative prioritization | Integration, Inspired Vision |

| New Office of Innovation (investment) | Responsible for fostering an integrated approach to innovation throughout the enterprise and instituting a culture of innovation in all areas | Innovation, Inspired Vision |

| New Office of External Affairs (investment) |

Works to advance MUSC’s vision and mission through meaningful relationships, collaborations, and partnerships with key external stakeholders | Inspired Vision |

| New South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (investment) | Facilitates the sharing of resources and expertise and streamlines research-related processes to bring about large-scale change in the state’s clinical and translational research efforts. | Innovation, Integration, Inspired Vision |

| New MUSC Health Center for Telehealth (investment) | One of only two National Telehealth Centers of Excellence in the country- focused on expanding access to services, coordinating care and improving the health of communities | Innovation, Inspired Vision |

| MUSC Leadership Institute (investment) | Integrating leadership development across the enterprise under a competency based model | Integration |

Measuring Impact

As a part of our strategy, we have put metrics in place which should be helpful in gaining objective information concerning collective organizational efficacy as a part of organizational culture. The metrics represent the key drivers of integration, innovation, and inspiration and reflect the tripartite mission of education, research and patient care. Metric subject examples include employee satisfaction, percentile rank of NIH awards compared to all health science centers, graduating students who would recommend MUSC to prospective students, employees who would recommend MUSC to friends and family for care, and percentile rank of MUSC on a Diversity Perception scale among comparison AHSCs. This is an ongoing process and metrics are evaluated and analyzed annually. Quality improvement initiatives are developed based upon metric results to improve outcomes.

Unique Approach to Leadership Development

Although it is recognized that collective leadership and the development of groups of leaders across an organization are required for causing institutional change, the majority of published program descriptions at AHSCs focus on the individual.11,12 In a comprehensive review of faculty leadership development programs offered by North American academic health centers, the authors found that the majority provided some form of leadership training, content was variable and rarely based on a specific leadership competency model.12 Approaches were compared to those that have been shown to align with an organization’s overall strategy and performance: skill building, opportunities for personal growth and feedback.

There were several innovative elements of our approach which were felt to be important. First, leadership development began in an integrated fashion engaging our institution’s strategic leaders across all three missions who received feedback for personal growth while specifically addressing the cultural aspect of leadership development. Second, we established a prima facie knowledge of our key drivers for our leadership development strategy and our desired collective leadership attributes. Third, in parallel to our leadership development, our strategic plan envisioned restructuring our enterprise in a manner that provided new strategic leadership opportunities, enabled more integration across the institution, and established innovation as a cultural norm.

To ultimately be successful, the strategic leadership programming for our institution will need to address collaboration and integration, communication and ideal decision-making processes emphasizing the importance of authentic and constructive interactions. Embedded within each of these action items is the seed of a competency that is part of our unique leadership competency model.

A new enterprise-wide entity, the MUSC Leadership Institute, has been established to guide leadership development strategy. Several new programs addressing both advanced and foundational leadership development have been created. A competency-based program for high-potential leaders has been launched and incorporates skill building, feedback and personal growth. Next steps will also include the launch of an enterprise-wide leadership orientation program and the integration of our leadership competency model into the hiring, development and evaluation of our future leaders.

Much work remains to be done, and rigorous evaluation of any planned program will be necessary. In addition to personal satisfaction with leadership development, MUSC will measure retention and promotion of leaders, the diversity of leadership, workforce engagement and specifically identified strategic outcomes for the institution. To what extent individual leadership development impacts the collective culture is not well explained in the literature, and we will need to discern which activities and teaching methodologies are best deployed in order to move us closer to our ideal leadership culture. Including training in collective efficacy may allow change and adoptions of innovations. New programs alone will not be sufficient to create this culture shift, and the leaders at MUSC will need to continue the process of behavioral change, and accountability for this change, in order to see this vision to fruition. This will be a longitudinal process that will likely start with programming and involve significant experimentation and disciplined, thoughtful evaluation to find the right model.

As the work of the AHSC continues to rapidly change and grow in complexity, leadership development is essential. By presenting this institutional process, we hope to elicit a conversation in the AHSC community about the role of leadership culture and the necessity of attending to that culture as the foundation for leadership development.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kathy Church, David McNair and Tim and Tova JohnPress for their consultative work on this initiative.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Previous Presentations

Presented in part at the ACLGIM Winter Summit December 2016, Austin, TX.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Fisher K. Academic Health Centers Save Millions of Lives. Washington DC: AAMC; June 4, 2019. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/academic-health-centers-save-millions-lives. Accessed September2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wartman SA. Nota Bene Ideas for Thought Leaders: Medicine and Machines: The Coming Transformation of Healthcare. Washington DC: AAMC; December, 2016. Accessed September2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enders T, Conroy J. Advancing the Academic Health System for the Future: A Report from the AAMC Advisory Panelon Health Care. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2014. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/advancing-future-academic-health-systems. Accessed October 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasmore W, Lafferty K, Spencer S. Developing a Leadership Strategy: A Critical Ingredient for Organizational Success. Greensboro: Center for Creative Leadership: Center for Creative Leadership; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beer M, Finnström M, Schrader D. Why leadership training fails—and what to do about it. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;94(10):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merriam Webster Dictionary. Culture. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture. Accessed January20, 2020.

- 7.Berry JC, Davis JT, Bartman T, et al. Improved safety culture and teamwork climate are associated with decreases in patient harm and hospital mortality across a hospital system. J Patient Saf. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dekker S. Just Culture: Restoring Trust and Accountability in Your Organization. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Leadership Circle. Leadership circle profile. https://leadershipcircle.com/en/products/leadership-circle-profile/. Accessed January20, 2020.

- 11.Garman AN, Lemak C. Developing Healthcare Leaders: What We Have Learned, and What is Next. National Center for Healthcare Leadership; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas R, Goldman EF, Scott AR, Dandar V. Leadership development programs at academic health centers: results of a national survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):229–236. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]