Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has developed into a serious pandemic with millions of cases diagnosed worldwide. To fight COVID-19 pandemic, over 100 countries instituted either a full or partial lockdown, affecting billions of people. In Tyrol, first lockdown measures were taken on 10 March 2020. On 16 March 2020, a curfew went into force which ended on 1 May 2020. On 19 March 2020, Tyrol as a whole was placed in quarantine which ended on 7 April 2020. The governmental actions helped reducing the spread of COVID-19 at the cost of significant effects on social life and behaviour. Accordingly, to provide a comprehensive picture of the population health status not only input from medical and biological sciences is required, but also from other sciences able to provide lifestyle information such as drug use. Herein, wastewater-based epidemiology was used for studying temporal trends of licit and illicit drug consumption during lockdown and quarantine in the area of the Tyrolean capital Innsbruck (174,000 inhabitants). On 35 days between 12 March 2020 and 15 April 2020, loads of 23 markers were monitored in wastewater. Loads determined on 292 days between March 2016 and January 2020 served as reference. During lockdown, changes in the consumption patterns of recreational drugs (i.e. cocaine, amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, methamphetamine, and alcohol) and pharmaceuticals for short-term application (i.e. acetaminophen, codeine, and trimethoprim) were detected. For illicit drugs and alcohol, it is very likely that observed changes were linked to the shutdown of the hospitality industry and event cancelation which led to a reduced demand of these compounds particularly on weekends. For the pharmaceuticals, further work will be necessary to clarify if the observed declines are indicators of improved population health or of some kind of restraining effect that reduced the number of consultations of medical doctors and pharmacies.

Keywords: Wastewater-based epidemiology, COVID-19, Illicit drug, Tobacco, Alcohol, Pharmaceuticals

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) is a well-established technique that provides information on human consumption and exposure to chemical residues at a community level. Commonly analysed chemicals include illicit drugs, ingredients of food, drink and tobacco, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, personal care products, and pollutants (Choi et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2018; Daughton, 2018; Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2017; Gracia-Lor et al., 2017; Gracia-Lor et al., 2018; Markosian and Mirzoyan, 2019; Rousis et al., 2017; van Nuijs et al., 2011a; Zuccato et al., 2005).

WBE involves systematically sampling of wastewater at the influent of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and quantitation of informative markers therein. Useful markers include the consumed chemicals as well as biotransformation products thereof. The per capita consumption of specific compounds can be estimated by converting wastewater concentrations into loads, correcting for compound-specific pharmacokinetics, and normalizing to the size of the contributing population (Jones et al., 2014; Zuccato et al., 2005).

WBE has been particularly successful in studying spatial and temporal trends of illicit drug use (Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2020; Ort et al., 2014; van Nuijs et al., 2011a). Spatial analysis can provide insights into the prevalence of drug use in different countries. For example, WBE results identify cocaine as the most prevalent and most frequently seized illicit stimulant in Southern and Western Europe, whereas amphetamines are reported as the most frequently consumed stimulants in northern and eastern countries (Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2020). Temporal analysis is able to identify changes in drug use over time. For instance, in many European cities population-normalized mass loads of benzoylecgonine increased significantly between 2011 and 2017 indicating changes in cocaine consumption over years that might be related to changes in prevalence, consumption habits or drug purity (Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2020).

Generally, wastewater composition is a mirror of the society. WBE provides insights in population lifestyle, behaviour and health. Recent studies have linked WBE results with sociodemographic and socioeconomic descriptors and changes (Choi et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). WBE was also able to detect and monitor changes induced by the Greek socioeconomic crisis (Thomaidis et al., 2016). Thus, in the current crisis triggered by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, WBE holds the promise to support governments, health authorities, and other relevant stakeholders in understanding the diseases and its impact on different communities as well as in finding options going through and forward after the COVID-19 pandemic (Adam, 2020).

To fight COVID-19 pandemic, over 100 countries worldwide had instituted either a full or partial lockdown, affecting billions of people. And many others had recommended restricted movement for some or all of their citizens. In the wake of the lockdown, a disturbance of the equilibrium of the market was expected. Disruption of demand and supply chains should have particularly affected the illicit drug market (UNODC, 2020). Due to the shutdown of the hospitality industry and the cancelation of all kinds of events, changes in alcohol and tobacco consumption are also likely to occur. Additionally, based on lessons learned from the 2008 financial crisis, it is hypothesized that the COVID-19 crisis will have further effects on public health, especially on mental health (Brooks et al., 2020; Karanikolos et al., 2016; Pfefferbaum and North, 2020) and in due consequence on the use of alcohol, drugs and pharmaceuticals (Clay and Parker, 2020; Rehm et al., 2020). Indeed, first reports from China (Qiu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), Italy (Moccia et al., 2020), and even Austria (Probst et al., 2020) pointed out that a relevant rate of individuals have experienced psychological distress following the COVID-19 outbreak.

The COVID-19 pandemic is clearly affecting lifestyle, behaviour and health. Changes are likely to alter wastewater compositions and loads of biomarkers that are analysed by WBE. Thus, the object of this work is to use the tools offered by WBE to identify direct and indirect effects of the current crisis on public health. In particular this study aims to identify trends in the use patterns of illicit and licit drugs during COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine in the Tyrolean capital Innsbruck. This is one of the first studies addressing this research question by WBE.

In order to achieve the aforementioned objective, the main illicit drugs together with important licit drugs, including alcohol, nicotine, caffeine as well as representatives of the classes of anaesthetics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, antihypertensives, analgesics and antibiotics, were investigated. The concentrations of 23 markers were determined in wastewater collected daily at the influent of Innsbruck's WWTP during COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine (12 March 2020 to 15 April 2020). Concentrations were converted to population normalized mass loads (PNLs) to identify temporal trends during the monitoring campaign. PNLs determined on 292 days between March 2016 and January 2020 served as reference.

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of targeted compounds

The study included analysis of markers for the consumption of caffeine, tobacco and alcohol, for illicit drug use, as well as for the intake of prescription or non-prescription medications. The targeted compounds are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Overview on studied compounds including information on the correction factors used to calculate drug consumption. The correction factors were taken from the literature (Castiglioni et al., 2015; Gracia-Lor et al., 2016; Thai et al., 2019; Zuccato et al., 2008).

| Compound | Biomarker for | Correction factor (CF) |

|---|---|---|

| 6-Acetylmorphine (MAM) | Heroin | 86.9 |

| Acetaminophen | Acetaminophen | n.a. |

| Amphetamine | Amphetamine | 3.3 |

| Benzoylecgonine | Cocaine | 3.59 |

| Caffeine | Caffeine | n.a. |

| Carbamazepine | Carbamazepine | 7.3 |

| Cocaine | Cocaine | 13 |

| Codeine | Codeine | 3.3 |

| Cotinine | Nicotine | 7.08 |

| 2-Ethylidene-1,5-dimethyl-3,3-diphenylpyrrolidine (EDDP) | Methadone | 3.4 |

| Ethyl sulfate (EtS) | Ethanol | 3046 |

| Lidocaine | Lidocaine | n.a. |

| 3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine | MDMA | n.a. |

| 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) | MDMA | 1.5 |

| Methadone | Methadone | 3.6 |

| Methamphetamine | Methamphetamine | 2.6 |

| Metoprolol | Metoprolol | n.a. |

| Morphine | Morphine | n.a. |

| 11-Nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC-COOH) | Tetrahydrocannabinol | 152 |

| Oxazepam | Oxazepam/Diazepam | n.a. |

| Tramadol | Tramadol | n.a. |

| Trimethoprim | Trimethoprim | n.a. |

| Venlafaxine | Venlafaxine | n.a. |

n.a. = data not available.

2.2. Chemicals and reagents

Water, methanol, isopropanol, and acetonitrile (all HPLC grade) were purchased from Honeywell (Seelze, Germany). Acetic acid (HOAc), heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA), triethylammonium acetate (TEAA, 1.0 M) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Formic acid was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Reference standards of the targeted compounds as well as the corresponding isotopically labelled internal standards were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX, USA) and Lipomed (Arlesheim, Switzerland). Stock solutions of the standards were prepared in methanol, stored at −20 °C. Calibrators and internal standards were prepared daily from the individual solutions.

2.3. Sample collection

Innsbruck was selected as model city to evaluate the usefulness of WBE for identifying changes in licit and illicit drug consumption. Innsbruck is the capital city of Austria's federal state Tyrol and the fifth-largest city of Austria, and has an actual population of about 132,000 inhabitants. The wastewater is collected in the city by a combined sewer system. Additionally, fourteen surrounding communities drain into the sewer system of Innsbruck, which is served by one WWTP. The total number of registered inhabitants in the catchment area is 174,000. Raw 24-h composite wastewater samples were collected following a common protocol (Castiglioni et al., 2013; Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2020; Ort et al., 2014) from the inlet of the WWTP in Innsbruck (ATTP_7-7101301). The mode of sampling was volume-proportional. Sewer system characteristics and key parameters of the influent wastewater are summarized in Supplementary materials Table S1. Between 2016 and 2020, 292 samples were collected in seventeen sampling series covering 7–22 consecutive days each (Supplementary materials Table S2). During COVID-19 lockdown, sample collection was accomplished daily from 2020-03-12 to 2020-04-15. This allows investigating of temporal trends throughout the week, over the studied periods and particularly the lockdown period. All samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.4. Sample analysis

Compound quantification was accomplished with five validated workflows (Fig. 1 ) involving liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Splitting was necessary to cover the range of compound concentrations and compound characteristics.

Fig. 1.

Overview on the five validated analytical workflows used for quantification of 23 targeted compounds in raw 24-h composite wastewater samples.

The LC-MS/MS system consisted of a 1100 series HPLC pump (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany), a CTC-PAL autosampler (CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, Switzerland) and a QTrap 4000 mass spectrometer (Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA).

Isotopically labelled analogues were used as internal standards (Supplementary materials Table S3). After addition of internal standard solutions, aliquots of the raw wastewater samples were processed by either centrifugation (EtS, caffeine, acetaminophen), evaporation (cotinine), or solid-phase extraction (SPE) methods (Fig. 1).

Details of the applied analytical methods are provided in Section S2 of the Supplementary material.

All methods were validated in influent wastewater according to published guidelines (Peters et al., 2007), and were found to be fit for the intended purpose. Internal quality control included analysis of blank and spiked samples (every 10 samples). External quality control involved the successful participation to inter-laboratory exercises (van Nuijs et al., 2018).

Seventeen biomarkers were investigated in all 327 samples available, methadone in 259 samples, caffeine, EtS, cotinine, acetaminophen, and THC-COOH in 218 samples. The reduced number of days covered by the later biomarkers is due to the fact that the corresponding analytical methods were introduced at a later stage of the monitoring process.

2.5. Estimation of loads and consumption rates

Daily mass loads of biomarkers were calculated by multiplying their concentrations in the 24-h composite samples with the corresponding daily flows of wastewater. Mass loads were then normalized to the number of people served by the WWTP to yield PNLs (mg/day/1000 inhabitants).

Consumed quantities and per capita intakes were estimated for caffeine, nicotine, ethanol, cocaine, amphetamine, MDMA, and methamphetamine using the following equations: (1) CONSUMPTION = CONC × F × CF, (2) INTAKE = CONC × F × CF × P−1. CONC is the concentration of each target analyte (ng/L) in influent wastewater, F is the daily wastewater flow rate (m3/day), CF is the specific correction factor for each analyte (Table 1) and P is the population served by the WWTP.

Different hydrochemical parameters were evaluated for characterizing the WWTP catchment population. This included the chemical oxygen demand (COD), the biological oxygen demand (BOD), ammonia-nitrogen (NH4-N), total-nitrogen (Ntot), and total-phosphorus (Ptot). Details of this evaluation are provided in Section S4 of the Supplementary material. As COD is a routine, economical, and daily available parameter and the studied WWTP mainly receives wastewater from residential areas, we decided to use this parameter for real-time estimates of catchment population size.

The statistical analysis and data visualizations were conducted in R (the R foundation, Vienna, Austria), SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

2.6. Mobility reports

Community mobility reports for Tyrol in March and April 2020 were obtained from Google LLC (Mountain View, CA, USA, https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/, accessed 2020-05-13). The mobility trends covered the following categories: (a) residential, (b) workplaces, (c) retail and recreation (e.g. restaurants, cafes, shopping centres, theme parks, museums, libraries, and movie theatres), and (d) grocery and pharmacy (e.g. grocery markets, food warehouses, farmers markets, specialty food shops, drug stores, and pharmacies).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Monitoring Innsbruck's wastewater before COVID-19

In this study, Innsbruck was selected as model city to evaluate the usefulness of WBE for identifying changes in licit and illicit drug consumption. Innsbruck is the capital city of Austria's federal state Tyrol and the fifth-largest city of Austria, and has an actual population of about 132,000 inhabitants. Innsbruck and fourteen surrounding communities are served by one WWTP. Thus, the total number of registered inhabitants in the catchment area of the WWTP is 174,000.

Because of the availability of a comprehensive set of WBE data, Innsbruck was perfectly suited for studying changes of lifestyle and behaviour during COVID-19 pandemic. WBE of Innsbruck's wastewater started in March 2016. Until January 2020, monitoring covered 292 days organized in seventeen series.

The available monitoring data served as baseline for evaluating the impact of lockdown and quarantine on licit and illicit drug consumption of the population living in the area of Innsbruck. Parts of the data have been submitted to the yearly international wastewater monitoring study focusing on the spatial comparison of drug consumption in Europe (Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2020). This study indicates that Innsbruck's patterns are similar to those observed in other Western and Southern European cities.

An overview on the ranges of compound-specific population normalized mass loads obtained during baseline monitoring (March 2016 to January 2020) is given in Fig. 2 . The loads spanned 5 orders of magnitude. Caffeine was the most abundant compound tested, followed by acetaminophen, EtS and cotinine. Methamphetamine, and MDA were found on the lower end of the concentration range. Nevertheless, methamphetamine was quantifiable in 88% of samples, and MDA in 69% of samples. MAM was not detected at all.

Fig. 2.

Population normalized loads observed for the 23 targeted compounds between March 2016 and January 2020.

The variability of the mass loads during the reference period can be expressed by the relative standard deviations (RSD). The RSDs ranged from 16.9% for caffeine to 86.6% for MDMA. Large RSD values suggest the occurrence of changes in consumption over time, either weekly, seasonally or yearly trends, and these were mainly observed for the biomarkers of illicit drugs (e.g. MDMA, benzoylecgonine, amphetamine) as well as for EtS, codeine and lidocaine.

3.2. The COVID-19 lockdown in Innsbruck

A time line covering the first two months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Innsbruck including information on the wastewater sampling period and the temporal distribution of active cases, is provided in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Timeline of the COVID-19 lockdown in Tyrol, including information on (a) the wastewater sampling period (2020-03-12 to 2020-04-15), (b) important government interventions, and (c) the number of acute cases.

The first two cases of COVID-19 in Innsbruck were confirmed on 25 February 2020. Beginning from 1 March 2020, authorities in different European countries began identifying the Tyrolean ski resorts as major coronavirus hotspots. On 10 March 2020, first steps towards lockdown were taken. On 16 March 2020, the Austrian government implemented a lockdown to contain further spread of the disease. A nationwide curfew went into force. On 19 March 2020, Tyrol as a whole was placed in quarantine. This quarantine ended on 7 April 2020. The nationwide curfew ended on 1 May 2020.

The number of active cases started to raise exponentially at the beginning of March. The government intervention helped reducing the spread of COVID-19 significantly. The peak of the number of active cases was reached on 2 April 2020. By the end of April less than 0.3 active cases per 1000 inhabitants were reported in Tyrol.

Wastewater was sampled from 12 March 2020 to 15 April 2020. Thus, the study started four days before the lockdown began, covered the full quarantine period, and ended when the first steps to exit the lockdown were taken.

Community mobility reports are a useful source of information to evaluate the impact of governmental interventions on social life and behaviour. Data for the Tyrolean population was collected and provided by Google LLC. The available data sets summarized the percent changes in visits to either places of residence, workplaces, places of retail and recreation, or places like grocery markets and pharmacies in March and April 2020 (Supplementary materials Fig. S1). As expected the governmental interventions (i.e. curfew, quarantine) were clearly affecting social life. All events were cancelled. Restaurants, bars, cafes and all kind of shops were closed. Only groceries and pharmacies were open. Inhabitants were not allowed to leave their main residences. Many companies introduced short-time working hours, and employees switched to home-based telework arrangements. Thus, Tyrolians were forced to spend more time at home. Traffic at workplaces, places of retail and recreation, as well as groceries and pharmacies was significantly reduced.

It was expected that the described changes in social life and mobility would have affected consumption of licit and illicit drugs as well, and this should be detectable by WBE.

3.3. Use of illicit drugs

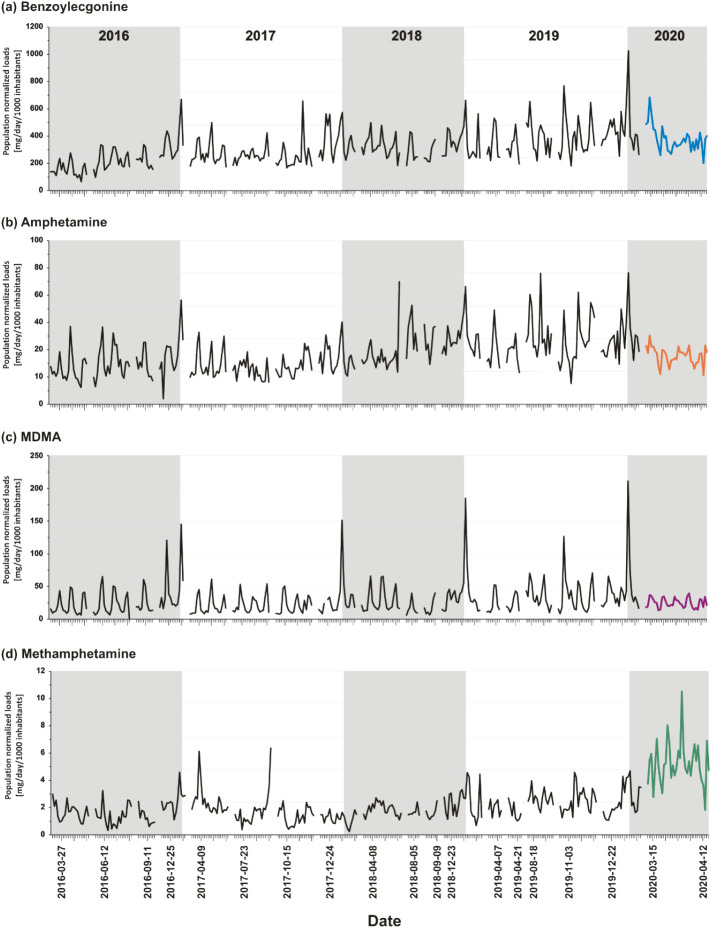

Fig. 4 presents the PNLs of benzoylecgonine, amphetamine, MDMA, and methamphetamine in the area of Innsbruck WWTP for the complete sampling campaign.

Fig. 4.

Temporal trends in population normalized loads of (a) benzoylecgonine, (b) amphetamine, (c) MDMA, and (d) methamphetamine between March 2016 and April 2020. Coloured lines are representing the lockdown period. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The weekly patterns of benzoylecgonine, amphetamine, and MDMA are shown in Fig. 5a–c. PNLs of 2019/2020 are compared to those observed during the lockdown 2020.

Fig. 5.

Weekly patterns in population normalized loads of (a) benzoylecgonine, (b) amphetamine, (c) MDMA, (d) ethyl sulfate, (e) cotinine, and (f) lidocaine during lockdown and the reference period (March 2019 to January 2020).

Like in other European cities (Gonzalez-Marino et al., 2020), cocaine consumption in Innsbruck increased significantly from 2016 to 2020 (Fig. 4a). The largest growth rate was observed in 2016. The average PNL of benzoylecgonine was more than doubled between the first sampling campaign in March 2016 (155 ± 52 mg/day/1000 inhabitants) and the fourth sampling campaign in December 2016 (345 ± 121 mg/day/1000 inhabitants). In 2019, the average PNL of benzoylecgonine was 389 ± 142 mg/day/1000 inhabitants. During lockdown, the average PNL of benzoylecgonine slightly decreased to 358 ± 71 mg/day/1000 inhabitants. A reduction was mainly observed during weekends (Fig. 5a).

Amphetamine use increased during 2018 (Fig. 4b). This is in agreement with findings in many other European cities observed in the annual monitoring campaign organized by the Sewage analysis CORe group - Europe (SCORE, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/wastewater_en). The average PNL of amphetamine was 16.8 ± 5.2 mg/day/1000 inhabitants in December 2017 and 24.2 ± 6.0 mg/day/1000 inhabitants in December 2018. In 2019/20, the average PNL of amphetamine was 23.2 ± 8.0 mg/day/1000 inhabitants. During lockdown, the average PNL of amphetamine decreased to 17.4 ± 3.0 mg/day/1000 inhabitants. Consumption was reduced on all weekdays (Fig. 5b). The largest effects were observed on weekends.

The pattern of MDMA consumption showed no significant changes between 2016 and 2020 (Fig. 4c). The highest MDMA loads were measured on New Year's Days (145–211 mg/day/1000 inhabitants). We observed more than two times higher PNL-values of MDMA during the weekend (Saturday and Sunday: 46.5 ± 18.6 mg/day/1000 inhabitants) than during weekdays (18.1 ± 8.7 mg/day/1000 inhabitants), reflecting the predominantly recreational use of this substance. On lockdown weekends, the average PNL of MDMA was reduced to 33.8 ± 3.3 mg/day/1000 inhabitants (Fig. 5c).

PNLs of methamphetamine were found to be lower than 4.0 mg/day/1000 inhabitants between 2016 and 2020 (Fig. 4d), indicating a very low demand for this drug on the local market. During lockdown, however, an average PNL of 5.3 ± 1.6 mg/day/1000 inhabitants was observed, indicating a significantly increased consumption of this drug.

Per capita intakes and consumed quantities are indicators for sales volumes on the illicit drug market. They are derived from PNLs. For the four stimulants, these indicators were calculated for the period 2019/2020 and the lockdown 2020. The results are summarized in Table 2 . Cocaine was the most used illicit stimulant in Innsbruck. This is followed by amphetamine and MDMA. Methamphetamine was hardly consumed before lockdown. During lockdown, sales of cocaine, amphetamine and MDMA were reduced by 6.1%, 28.1%, and 23.0%, respectively. Consumed quantities of methamphetamine, on the other hand, were more than doubled. It is very likely that this compound was used as substitute for other stimulants.

Table 2.

Summary of average per capita intakes and average quantities consumed per day of selected licit and illicit drugs calculated for the period 2019/2020 and the lockdown 2020.

| Compound | Average per capita intake before lockdown | Average per capita intake during lockdown | Average quantities consumedbefore lockdown | Average quantities consumedduring lockdown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | 1.4 ± 0.5 g/day/1000 inhabitants | 1.3 ± 0.3 g/day/1000 inhabitants | 340 ± 95 g/day | 320 ± 51 g/day |

| Amphetamine | 76 ± 26 mg/day/1000 inhabitants | 57 ± 10 mg/day/1000 inhabitants | 19 ± 5 g/day | 14 ± 2 g/day |

| MDMA | 54 ± 47 mg/day/1000 inhabitants | 37 ± 11 mg/day/1000 inhabitants | 13 ± 10 g/day | 9.3 ± 2.5 g/day |

| Methamphetamine | 6.3 ± 2.5 mg/day/1000 inhabitants | 14 ± 4 mg/day/1000 inhabitants | 1.5 ± 0.5 g/day | 3.4 ± 0.9 g/day |

| Ethanol | 12.6 ± 4.8 kg/day/1000 inhabitants | 9.9 ± 2.2 kg/day/1000 inhabitants | 3.0 ± 1.0 t/day | 2.5 ± 0.5 t/day |

| Nicotine | 4.3 ± 0.8 g/day/1000 inhabitants | 4.3 ± 0.6 g/day/1000 inhabitants | 1.0 ± 0.1 kg/day | 1.1 ± 0.2 kg/day |

| Caffeine | 519 ± 89 g/day/1000 inhabitants | 570 ± 91 g/day/1000 inhabitants | 128 ± 17 kg/day | 141 ± 13 kg/day |

For the stimulants, the equilibrium of the market was disturbed during lockdown. Due to the shutdown of the hospitality industry and the cancelation of all kinds of events, a reduced demand for drug use in recreational settings was observed, and this affected sales of MDMA, cocaine, and amphetamine. Additionally, difficulties with the delivery (e.g. amphetamine) may have occurred that were partially compensated by substitution with methamphetamine.

With WBE, the consumption of other important illicit drugs, including cannabis, heroin and methadone, was studied as well. On the community level, lockdown had no effect on the consumed quantities of these compounds.

Cannabis was the most used illicit drug in Innsbruck. Average PNLs of THC-COOH were 101 ± 25 mg/day/1000 inhabitants before lockdown and 109 ± 14 mg/day/1000 inhabitants during lockdown. During the complete sampling campaign, the average per capita intake of THC was 15.6 ± 3.6 g/day/1000 inhabitants.

MAM was used as biomarker for heroin consumption. Due to the facts that this compound is excreted in low amounts and shows limited stability in wastewater, we were not able to detect MAM in the collected samples.

Methadone and EDDP served as biomarker for methadone consumption. The lockdown had no clear effect on methadone consumption. This observation is quite reasonable, as this drug is primarily used in opioid maintenance treatment.

A recently published report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) summarized preliminary findings on the European level regarding changes in drug consumption patterns during lockdown (EMCDDA, 2020). The EMCDDA report further provided WBE results for Amsterdam (The Netherlands), Castellon de la Plana (Spain), and Helsinki (Finland). As expected, the results of Amsterdam and Castellon de la Plana were in line with our findings. Compared with previous years, PNLs of MDMA and benzoylecgonine were significantly reduced. THC-COOH loads remained stable. In Helsinki, situation was different. WBE indicated that a record amount of amphetamine was being used during lockdown. By comparison, no major changes were observed for methamphetamine use.

3.4. Consumption of alcohol, nicotine and caffeine

Known to mankind for several centuries, alcohol, tobacco and coffee have become an important part of culture, serving as a vehicle for social interaction, and shaping the urban landscape with dedicated places for sales and consumption. In western societies, ethanol, nicotine and caffeine are among the most prevalent psychotropic drugs. Their consumption can be studied with WBE.

The weekly patterns of ethyl sulfate and cotinine are shown in Fig. 5d–e. PNLs of 2019/2020 are compared to those observed during the lockdown 2020.

Ethyl sulfate was used as biomarker for estimating alcohol consumption. This compound is stable and detectable in wastewater (Reid et al., 2011). For Innsbruck, a strong weekly consumption pattern was observed (Fig. 5d). PNL-values of ethyl sulfate were higher during weekend than during weekdays. In 2019/20, the average PNL of ethyl sulfate was 4140 ± 1590 mg/day/1000 inhabitants. During lockdown, the average PNL of ethyl sulfate decreased to 3260 ± 710 mg/day/1000 inhabitants. Alcohol consumption was reduced on all weekdays.

Cotinine served as biomarker for estimating nicotine and tobacco consumption, respectively (Castiglioni et al., 2015; Mackulak et al., 2015). There was no statistically significant difference in PNLs between weekdays and sampling periods (Fig. 5e). The average PNLs of cotinine were 604 ± 112 mg/day/1000 inhabitants in 2019/20, and 611 ± 84 mg/day/1000 inhabitants during lockdown.

For the complete sampling campaign, the average nicotine intake was calculated to be 4.1 ± 1.0 mg/day/inhabitant, which corresponds to the consumption of 3.3 ± 0.8 cigarettes/day/inhabitant (1.25 mg nicotine per cigarette). The wastewater data correlates well to Austrian sales figures. According to official data provided by the Austrian Statistical Office, 3.4 cigarettes are purchased per day and inhabitant.

By using the average amount of cotinine excreted by a smoker, the share of smokers in Innsbruck's population can be assessed. If a smoker excretes about 2.4 mg/day (Buerge et al., 2008; Mackulak et al., 2015), then the observed average PNL of 60 mg/day/100 inhabitants of cotinine corresponds to 25.0 ± 4.6 smokers/day/100 inhabitants, which again correlates well to official data provided by the Austrian Statistical Office (24.5% in 2014).

Fig. 6a compares the PNLs of caffeine during lockdown 2020 with PNLs observed during the remaining days of the sampling campaign. From 2016 to 2020, the average PNL of caffeine was 16.3 ± 2.8 g/day/1000 inhabitants. During lockdown, the PNL slightly increased to 17.1 ± 2.7 g/day/1000 inhabitants. The difference, however, was not statistically significant.

Fig. 6.

Temporal trends in population normalized loads of (a) caffeine, (b) oxazepam, (c) morphine, (d) codeine (e) acetaminophen, and (f) trimethoprim during lockdown. The population normalized loads determined between March 2016 and January 2020 were used as reference.

Regarding the consumption of alcohol, nicotine and caffeine, the governmental interventions during lockdown mainly affected consumption of alcohol. With the shutdown of the hospitality industry, the cancelation of all kinds of events and the prohibition of any kind of social interaction with non-family members, common places and occasions for social drinking of alcoholic beverages were not available during quarantine. In Austria, social drinking accounts for approximately one third of the total amount of consumed alcohol (Bachmayer et al., 2020). Thus, a 20% reduction of alcohol consumption seems to be reasonable.

Consumed quantities of tobacco and coffee were hardly affected. Maybe, for these two licit drugs, reduced social consumption was compensated by an increased use in the private setting.

3.5. Use of pharmaceuticals

Ten biomarkers of pharmaceutical compounds were quantified in the collected wastewater samples. These included oxazepam, venlafaxine, carbamazepine, metoprolol, morphine, tramadol, lidocaine, acetaminophen, codeine, and trimethoprim. The patterns of use for the monitored compounds between the different sampling periods were evaluated.

The weekly pattern of lidocaine is shown in Fig. 5f. PNLs of 2019/2020 are compared to those observed during the lockdown 2020.

Lidocaine is primarily used as local anaesthetic. The efficacy profile of lidocaine is characterized by a rapid onset of action and intermediate duration of efficacy. Therefore, lidocaine is suitable for infiltration, block, and surface anaesthesia as single dose applications. Lidocaine is commonly used in dentistry. As the working week of dentists usually ends on Friday, a strong weekly consumption pattern was observed (Fig. 5f). Average PNL-values of lidocaine were 40% higher during weekdays than during weekends. There was no statistically significant difference in PNLs between sampling periods. The average PNLs of lidocaine were 31.5 ± 14.5 mg/day/1000 inhabitants in 2019/20, and 28.9 ± 9.9 mg/day/1000 inhabitants during lockdown.

Fig. 6b–f compare the PNLs of oxazepam, morphine, acetaminophen, codeine, and trimethoprim during lockdown 2020 with PNLs observed during the remaining days of the sampling campaign.

Oxazepam, venlafaxine, carbamazepine were regarded as markers for changes in mental health treatment during lockdown. Oxazepam is a benzodiazepine that is used in the treatment of anxiety and insomnia. Furthermore, it is a metabolite of diazepam, prazepam, and temazepam. Venlafaxine is an antidepressant of the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor class that is used in the treatment of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. Carbamazepine is an anticonvulsant that is primarily used in the treatment of epilepsy and neuropathic pain. Furthermore, it is used in schizophrenia along with other medications and as a second-line agent in bipolar disorder.

Lockdown and quarantine are essential interventions to prevent the uncontrolled spread of COVID-19. However, such measures pose a challenge for mental health (Pfefferbaum and North, 2020). Especially, people who contract the disease, those at heightened risk for it, people with pre-existing psychiatric problems, and health care providers are vulnerable to emotional distress. Possible emotional outcomes include stress, depression, insomnia, fear, anger, and frustration (Brooks et al., 2020). A recent study has pointed out that only 4% of the Austrian population had clinically relevant depression between 2013 and 2015, but around 20% during the early weeks of COVID-19 lockdown (Probst et al., 2020). Nevertheless, WBE provided no evidence for increased use of nervous system drugs in Innsbruck during the early weeks of lockdown. Average PNLs of oxazepam (328 ± 84 mg/day/1000 inhabitants, Fig. 6b) and carbamazepine (103 ± 39 mg/day/1000 inhabitants) showed no statistically significant difference to those observed the years before. For venlafaxine, a temporal trend was observed; but this was not directly linked with COVID-19. Between 2016 and 2020, venlafaxine loads showed yearly growth rates of 5–10%. During quarantine monitoring, the average PNL was higher than before (111 ± 18 mg/day/1000 inhabitants in 2019/20 vs. 127 ± 15 mg/day/1000 inhabitants during lockdown). Nevertheless, individual PNL-values during lockdown did not follow a trend.

There is evidence that lockdown and quarantine had an impact on mental health of both individuals and communities. Nevertheless, at least during quarantine, WBE results for Innsbruck did not support this hypothesis. An explanation for the observed discrepancy was provided recently. In the early weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown in Austria, the total number of patients treated on average per week was lower than in the months before (Probst et al., 2020). The indicated undersupply of psychotherapy might have prevented rise of prescribed drug consumption at the community level.

Metoprolol is a beta blocking agent that is used for a number of conditions, including hypertension, angina, acute myocardial infarction, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and prevention of migraine headaches. In this study, metoprolol was regarded as marker for changes in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases during lockdown. No statistically significant difference in PNLs before and during lockdown was observed. The PNL of metoprolol was 89 ± 20 mg/day/1000 inhabitants in 2016–2020, and 92 ± 13 mg/day/1000 inhabitants during lockdown. Furthermore, no trend could be identified over time for the PNL of metoprolol during lockdown monitoring.

Acetaminophen, codeine, tramadol and morphine are analgesics. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder for the treatment of pain (WHO, 1990), acetaminophen is a step 1 analgesic for treatment of mild pain. Codeine is a step 2 medication. Step 2 adds a moderate opioid agonist in combination with non-opioids (e.g. acetaminophen) for moderate pain or pain of shorter duration, such as postoperative. Tramadol and morphine are step 3 medications of the opioid/opiate family. They are used to treat moderate-severe and often chronic pain. Morphine is further applied for drug maintenance therapy in opioid-dependent individuals.

During quarantine, the average PNL of morphine (522 ± 75 mg/day/1000 inhabitants) was significantly higher than that observed in 2019/20 (396 ± 86 mg/day/1000 inhabitants). As the PNL of morphine showed no trend during quarantine monitoring (Fig. 6c), it is likely that the increase is not directly linked with the COVID-19 lockdown.

Tramadol is the other step 3 analgesic monitored. PNLs (134 ± 22 mg/day/1000 inhabitants) in lockdown were not significantly different to those observed in 2019/20 (130 ± 40 mg/day/1000 inhabitants).

Codeine and acetaminophen represent analgesics that are used for a limited duration. The PNL graphs of these two compounds showed specific characteristics (Fig. 6d, e): The PNLs started at levels in the third quartile of the concentration range indicating increased consumption of these analgesics prior to lockdown. It is unclear whether the higher demand was directly linked with the COVID-19 crisis or with another (seasonal) disease (e.g. flu and colds). An interesting observation was that the PNLs showed a decline during the quarantine period.

WBE indicates a decline of the consumption of analgesics used for short-term pain management during the quarantine period. An important class of this type of medication is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen. Their use has been associated with potentially serious dose-dependent gastrointestinal complications such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding (Butt et al., 1988). Interestingly, a recent report from Austria indicated that national lockdown resulted a decrease in upper gastrointestinal bleeding events (Schmiderer et al., 2020). The authors speculated that reduced visits to emergency departments as well as reduced stress factors could have played a role. Our results provided an additional explanation: reduced consumption of analgesics.

Trimethoprim is an antibiotic that is mainly used to treat urinary tract infections. Like the PNLs of the analgesics used for short-term pain management, PNLs of trimethoprim declined during quarantine (Fig. 6f).

WBE showed that the use of pharmaceuticals for short-term application (i.e. acetaminophen, codeine, and trimethoprim) declined during quarantine. For pharmaceuticals in long-term use (i.e. oxazepam, venlafaxine, carbamazepine, metoprolol, morphine, and tramadol), however, no such trend was detectable. Community mobility reports demonstrated that traffic at pharmacies was significantly reduced during quarantine (Supplementary materials Fig. S1d). Furthermore, a decline in medical consultations during COVID-19 pandemic was observed in Austria (Probst et al., 2020). The different indicators provided evidence for an impact of lockdown and quarantine on drug consumption patterns. Further work will be necessary to clarify if these changes are linked with the population health status. Currently, it cannot be answered whether people stayed at home with various diseases which would have required treatments or in contrast change in lifestyle during lockdown with social distancing resulted in less disease.

3.6. Assumptions and limitations of this study

This study is a first attempt to investigate the impact of COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine on use patterns of illicit drugs, ingredients of drinks and tobacco, as well as pharmaceuticals with WBE. Certain limitations are noted with respect to the interpretation of results.

Various sources of uncertainty are associated in each step of the analytical process: sampling, chemical analysis, wastewater flow measurement, excretion rate, and population estimation. The individual uncertainties were assumed to be 20% as described in previous studies (Castiglioni et al., 2013; Lai et al., 2015; Ort et al., 2014).

Systematic uncertainties, e.g. inaccurate population size or neglecting in-sewer transformation, can lead to systematic under- or overestimation of per capita loads and consumption.

COD-values were used for population size estimation. COD is a routine, economical, and daily available parameter. There are hints that COD-derived values might overestimate population size (see Section S4 of the Supplementary material). As the population size was used for normalization, calculated per capita loads and consumptions might have been underestimated. Nevertheless, based on the outcome of this and other studies (Gao et al., 2016; Tscharke et al., 2019; van Nuijs et al., 2011b), we believe that the bias is acceptable and will not affect the detection of temporal trends.

The impact of in-sewer processes leading to an underestimation of drug loads is not known for all chemicals tested in this study. Nevertheless, at least for many illicit drugs it is considered to be smaller than 10% (Castiglioni et al., 2013; McCall et al., 2016).

We have applied optimized and validated analytical workflows. Accuracy was generally among 85%–115% with a precision (%RSD) below 15%. Nevertheless, without the availability of reference material, the occurrence of systematic errors caused by environmental factors, sample preparation and analyses cannot completely be ruled out, and this was recently demonstrated for WBE of cannabis (Causanilles et al., 2017).

Unconsumed drugs dumped into sewers would lead to elevated loads. Dumping was indicated by unexpected high loads on a certain day in comparison to all other monitored days as well as by shifts of parent drug to metabolite ratios (e.g. MDMA, cocaine, and methadone). Such data points were removed from statistical analysis.

Random uncertainties may affect the assessment of temporal changes. This problem, however, should have been overcome by using a sufficient number of monitoring days to characterize drug consumption before and during lockdown.

The load of a biomarker in wastewater does not give insight into the prevalence of its excretion in the population sampled. Identical loads can either result from the same number of people exposed to the chemical at the same level or a fewer number of people exposed at a higher level. This is a limitation of the method but it is an advantage from an ethical viewpoint to ensure the anonymity of individuals in the catchment area.

4. Conclusions

In this study, WBE was used to investigate changes in in the use patterns of illicit and licit drugs during COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine in the Tyrolean capital Innsbruck. Temporal trends were identified by determining PNLs of 23 markers. Particularly, changes in the consumption patterns of recreational drugs and pharmaceuticals for short-term application were detected. Consumption patterns of drugs for long-term application (i.e. oxazepam, carbamazepine, venlafaxine, metoprolol, tramadol, and morphine), on the other hand, were not affected.

Due to the shutdown of the hospitality industry and the cancelation of all kinds of events, a reduced demand for drug use in recreational settings was observed, and this affected sales of alcohol, cocaine, MDMA, and amphetamine. Additionally, difficulties with the delivery of stimulants (e.g. amphetamine) might have occurred that were partially compensated by substitution with methamphetamine.

The observed decline in the use of pharmaceuticals for short-term application (i.e. acetaminophen, codeine, and trimethoprim) during quarantine might either be linked with improved population health or any kind of restraining effect that reduced the number of consultations of medical doctors and pharmacies.

Clearly, the results demonstrate that WBE can be used to identify quarantine-induced changes in lifestyle, behaviour and health that are associated with the consumption of specific chemicals or food components.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Extended information on applied methods.

Overview on population normalized mass loads (PNLs, in mg/day/1000 inhabitants) obtained for investigated compounds.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

HO elaborated conception and design of this study. All authors contributed to data acquisition and analysis. VR and HO wrote a first version of the manuscript. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to Klemens Geiger who was an important promotor of the local WBE initiative.

Editor: Dimitra A Lambropoulou

References

- Adam D. Modelling the pandemic: the simulations driving the world’s response to COVID-19. Nature. 2020;580:316–318. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmayer S., Strizek J., Hojni M., Uhl A. eighth ed. Gesundheit Österreich GmbH; Vienna, Austria: 2020. Handbuch Alkohol Österreich. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerge I.J., Kahle M., Buser H.R., Muller M.D., Poiger T. Nicotine derivatives in wastewater and surface waters: application as chemical markers for domestic wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:6354–6360. doi: 10.1021/es800455q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt J.H., Barthel J.S., Moore R.A. Clinical spectrum of the upper gastrointestinal effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Natural history, symptomatology, and significance. Am. J. Med. 1988;84:5–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni S., Bijlsma L., Covaci A., Emke E., Hernandez F., Reid M., et al. Evaluation of uncertainties associated with the determination of community drug use through the measurement of sewage drug biomarkers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:1452–1460. doi: 10.1021/es302722f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni S., Senta I., Borsotti A., Davoli E., Zuccato E. A novel approach for monitoring tobacco use in local communities by wastewater analysis. Tob. Control. 2015;24:38–42. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causanilles A., Baz-Lomba J.A., Burgard D.A., Emke E., Gonzalez-Marino I., Krizman-Matasic I., et al. Improving wastewater-based epidemiology to estimate cannabis use: focus on the initial aspects of the analytical procedure. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;988:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P.M., Tscharke B.J., Donner E., O’Brien J.W., Grant S.C., Kaserzon S.L., et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology biomarkers: past, present and future. Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;105:453–469. [Google Scholar]

- Choi P.M., Tscharke B., Samanipour S., Hall W.D., Gartner C.E., Mueller J.F., et al. Social, demographic, and economic correlates of food and chemical consumption measured by wastewater-based epidemiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:21864–21873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910242116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay J.M., Parker M.O. Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: a potential public health crisis? Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e259. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30088-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C.G. Monitoring wastewater for assessing community health: Sewage Chemical-Information Mining (SCIM) Sci. Total Environ. 2018;619:748–764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction . 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on Patterns of Drug Use and Drug-related Harms in Europe. EMCDDA Trendspotter Briefing. Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., O’Brien J., Du P., Li X., Ort C., Mueller J.F., et al. Measuring selected PPCPs in wastewater to estimate the population in different cities in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;568:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Marino I., Rodil R., Barrio I., Cela R., Quintana J.B. Wastewater-based epidemiology as a new tool for estimating population exposure to phthalate plasticizers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:3902–3910. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Marino I., Baz-Lomba J.A., Alygizakis N.A., Andres-Costa M.J., Bade R., Bannwarth A., et al. Spatio-temporal assessment of illicit drug use at large scale: evidence from 7 years of international wastewater monitoring. Addiction. 2020;115:109–120. doi: 10.1111/add.14767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Lor E., Zuccato E., Castiglioni S. Refining correction factors for back-calculation of illicit drug use. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;573:1648–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Lor E., Castiglioni S., Bade R., Been F., Castrignano E., Covaci A., et al. Measuring biomarkers in wastewater as a new source of epidemiological information: current state and future perspectives. Environ. Int. 2017;99:131–150. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Lor E., Rousis N.I., Hernandez F., Zuccato E., Castiglioni S. Wastewater-based epidemiology as a novel biomonitoring tool to evaluate human exposure to pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:10224–10226. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H.E., Hickman M., Kasprzyk-Hordern B., Welton N.J., Baker D.R., Ades A.E. Illicit and pharmaceutical drug consumption estimated via wastewater analysis. Part B: placing back-calculations in a formal statistical framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;487:642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanikolos M., Heino P., McKee M., Stuckler D., Legido-Quigley H. Effects of the global financial crisis on health in high-income OECD countries: a narrative review. Int. J. Health Serv. 2016;46:208–240. doi: 10.1177/0020731416637160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F.Y., Anuj S., Bruno R., Carter S., Gartner C., Hall W., et al. Systematic and day-to-day effects of chemical-derived population estimates on wastewater-based drug epidemiology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:999–1008. doi: 10.1021/es503474d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackulak T., Birosova L., Grabic R., Skubak J., Bodik I. National monitoring of nicotine use in Czech and Slovak Republic based on wastewater analysis. E. 2015;22:14000–14006. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markosian C., Mirzoyan N. Wastewater-based epidemiology as a novel assessment approach for population-level metal exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;689:1125–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall A.K., Bade R., Kinyua J., Lai F.Y., Thai P.K., Covaci A., et al. Critical review on the stability of illicit drugs in sewers and wastewater samples. Water Res. 2016;88:933–947. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moccia L., Janiri D., Pepe M., Dattoli L., Molinaro M., De Martin V., et al. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048. Published online 2020 Apr 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ort C., van Nuijs A.L.N., Berset J.D., Bijlsma L., Castiglioni S., Covaci A., et al. Spatial differences and temporal changes in illicit drug use in Europe quantified by wastewater analysis. Addiction. 2014;109:1338–1352. doi: 10.1111/add.12570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters F.T., Drummer O.H., Musshoff F. Validation of new methods. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007;165:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;20:1866. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst T., Stippl P., Pieh C. Changes in provision of psychotherapy in the early weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Kilian C., Ferreira-Borges C., Jernigan D., Monteiro M., Parry C.D.H., et al. Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19: implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39:301–304. doi: 10.1111/dar.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid M.J., Langford K.H., Morland J., Thomas K.V. Analysis and interpretation of specific ethanol metabolites, ethyl sulfate, and ethyl glucuronide in sewage effluent for the quantitative measurement of regional alcohol consumption. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1593–1599. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousis N.I., Gracia-Lor E., Zuccato E., Bade R., Baz-Lomba J.A., Castrignano E., et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology to assess pan-European pesticide exposure. Water Res. 2017;121:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiderer A., Schwaighofer H., Niederreiter L., Profanter C., Steinle H., Ziachehabi A., et al. Decline in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during Covid-19 pandemic after lockdown in Austria. Endoscopy. 2020;52(11):1036–1038. doi: 10.1055/a-1178-4656. Epub 2020 May 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai P.K., O’Brien J.W., Tscharke B.J., Mueller J.F. Analyzing wastewater samples collected during census to determine the correction factors of drugs for wastewater-based epidemiology: the case of codeine and methadone. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019;6:265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Thomaidis N.S., Gago-Ferrero P., Ort C., Maragou N.C., Alygizakis N.A., Borova V.L., et al. Reflection of socioeconomic changes in wastewater: licit and illicit drug use patterns. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:10065–10072. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tscharke B.J., O’Brien J.W., Ort C., Grant S., Gerber C., Bade R., et al. Harnessing the power of the census: characterizing wastewater treatment plant catchment populations for wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:10303–10311. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime . 2020. World Drug Report 2020. (Vienna, Austria) [Google Scholar]

- van Nuijs A.L.N., Castiglioni S., Tarcomnicu I., Postigo C., de Alda M.L., Neels H., et al. Illicit drug consumption estimations derived from wastewater analysis: a critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2011;409:3564–3577. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nuijs A.L.N., Mougel J.F., Tarcomnicu I., Bervoets L., Blust R., Jorens P.G., et al. Sewage epidemiology - a real-time approach to estimate the consumption of illicit drugs in Brussels, Belgium. Environ. Int. 2011;37:612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nuijs A.L.N., Lai F.Y., Been F., Andres-Costa M.J., Barron L., Baz-Lomba J.A., et al. Multi-year inter-laboratory exercises for the analysis of illicit drugs and metabolites in wastewater: development of a quality control system. Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;103:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 1990. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care: Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 804. Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.Z., Duan L., Wang B., Du Y.L., Cagnetta G., Huang J., et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology in Beijing, China: prevalence of antibiotic use in flu season and association of pharmaceuticals and personal care products with socioeconomic characteristics. Environ. Int. 2019;125:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Lu H., Zeng H., Zhang S., Du Q., Jiang T., et al. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:49–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E., Chiabrando C., Castiglioni S., Calamari D., Bagnati R., Schiarea S., et al. Cocaine in surface waters: a new evidence-based tool to monitor community drug abuse. Environ. Health. 2005;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E., Chiabrando C., Castiglioni S., Bagnati R., Fanelli R. Estimating community drug abuse by wastewater analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:1027–1032. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Extended information on applied methods.

Overview on population normalized mass loads (PNLs, in mg/day/1000 inhabitants) obtained for investigated compounds.