Patients with COVID-19 and preexisting diseases are likely to have poor outcomes. Coagulopathy is a prominent clinical manifestation and coagulation markers are recognized as haematological risk factors for mortality. Anticoagulant use is an important supportive treatment that may benefit patient survival. Preliminary data showed that anticoagulant therapy was associated with lower mortality in severe patients with markedly elevated D-dimer [1]. However, data on anticoagulation use in Chinese patients during the early pandemic era are limited. The associations of Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) and other available treatments with patients' prognoses are not well established. Therefore, we report our initial experience in treatments for COVID-19 hospitalized patients, particularly the use of LMWH.

A pragmatic cohort study was performed, involving adult patients with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 consecutively admitted to the affiliated hospital of Jianghan University between January 10th, 2020 and February 28th, 2020. Patients were followed for 28 days after admission. COVID-19 infection was diagnosed according to the Chinese management guideline (Trial Version 5 Revised, http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/d4b895337e19445f8d728fcaf1e3e13a.shtml). We obtained ethical approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Jianghan University and China-Japan Friendship Hospital (WHSHIRB-K-2020015) on April 21, 2020. Subcutaneous LMWH (Low Molecular Weight Heparin Sodium for Injection, Jiangsu Wanbang Biochemical Pharmaceutical Co. LTD, China) use was recorded, administered as prophylactic dosage 3000–5000 U/day or the therapeutic dose was based on actual body weight (100 U/kg, q12h). All patients were given intravenous methylprednisolone according to our guideline, 40 or 80 mg/day. The primary outcome was mortality within 28 days after hospital admission. Patients discharged earlier were followed to day 28 to ascertain survival.

Data were summarized as number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (SD) or median (interquartile ranges [IQR]) for continuous variables as appropriate. t-test, Mann Whitney U test, Chi-square test or Fisher exact test were used to compare differences in baseline characteristics, treatment and complications. To explore an association of LMWH treatment with 28-day mortality, we fitted multivariable Cox regression model with covariates adjusted. The proportional hazard assumption was tested and if the assumption was violated, an extended Cox analysis with time-varying covariates was performed. The violating covariates were handled by their interactions with followed-up time. Patients alive at day 28 were regarded as right-censored. Based on the up-to-date knowledge on COVID-19 and prior research, we constructed a causal diagram to visually illustrate the potential effect of exposures on fatal outcomes (Fig.A.1). Five blocks of factors were analyzed: typical demographic information, comorbidities, COVID-19 severity, coagulopathy on admission, and treatments provided in hospital. In our prior research, normal D-dimer on admission and day 3 were highly predictive of 28-day survival [2]. In this study, LMWH treatment was the major focus and D-dimer elevation was an important confounder requiring adjustment. Likewise, other factors potentially associated with mortality were adjusted in the multivariable Cox model. The hypothetical links from demographical characteristics, clinical features, and treatments to mortality at 28 day were included in a directed acyclic graph. Variables were evaluated for multicollinearity and independence. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) with two-tailed p < 0.05 considered significant.

Altogether, 761 adult patients with confirmed COVID-19 were consecutively admitted to hospital during the study period. We excluded 2 patients who died on admission and another 10 patients whose D-dimer data were unavailable, leaving 749 patients. The mean (SD) age was 60 (15) years and 48% were men. The admitted patients had an overall SOFA score of 1 (0–2) on admission. Fever and cough were predominant symptoms when admitted and 40% had underlying diseases, most commonly hypertension (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Demographic information, clinical characteristics, laboratory findings and treatments of COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

| Variablesa | Total (N = 749) |

Survivors (N = 671) |

Non-survivors (N = 78) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic information | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 60 (15) | 58 (15) | 71 (11) | <0.01 |

| Male, No. (%) | 356 (48) | 300 (45) | 56 (72) | <0.01 |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 65 (11) | 65 (11) | 66 (11) | 0.45 |

| Clinical characteristics at admission | ||||

| SOFA score | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 3 (2–5) | <0.01 |

| Symptoms, No. (%) | ||||

| Feverb | 567 (76) | 513 (76) | 54 (69) | 0.16 |

| Cough | 460 (61) | 412 (61) | 48 (62) | 0.98 |

| Fatigue | 346 (46) | 308 (46) | 38 (49) | 0.64 |

| Dyspnea | 226 (30) | 191 (28) | 35 (45) | <0.01 |

| Sputum | 187 (25) | 160 (24) | 27 (35) | 0.04 |

| Underlying diseasesb | 297 (40) | 253 (38) | 44 (56) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 235 (31) | 199 (30) | 36 (46) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes | 85 (11) | 73 (11) | 12 (15) | 0.24 |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 47 (6) | 37 (6) | 10 (13) | 0.02 |

| Coronary disease | 43 (6) | 36 (5) | 7 (9) | 0.20 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (1) | 5 (1) | 3 (4) | 0.04 |

| Laboratory findings at admission, median (IQR) | ||||

| WBC, 109/L | 5.12 (3.92–6.77) | 4.98 (3.82–6.28) | 7.88 (5.88–11.05) | <0.01 |

| Lymphocyte, 109/L | 0.87 (0.63–1.19) | 0.89 (0.65–1.21) | 0.61 (0.4–0.87) | <0.01 |

| PCT, ng/mL | 0.09 (0.04–0.17) | 0.08 (0.04–0.15) | 0.21 (0.13–0.35) | <0.01 |

| HCRP, mg/L | 42.09 (9.9–106.86) | 33.62 (8.71–86.43) | 155.41 (105.28–184.3) | <0.01 |

| AST, U/L | 28.31 (19.26–44.31) | 27.23 (18.65–41.33) | 46.86 (33.51–75.24) | <0.01 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 68.68 (55.17–85.04) | 67.28 (53.96–82.08) | 89.11 (69.88–122.63) | <0.01 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 0.43(0.32–0.70) | 0.40(0.31–0.62) | 0.91(0.59–2.87) | <0.01 |

| PT, s | 10.7 (10.1–11.3) | 10.6 (10.1–11.2) | 11.4 (10.7–12.5) | <0.01 |

| aPTT, s | 25.2 (22.5–28.3) | 25.1 (22.4–28.2) | 27.4 (23.5–31.0) | <0.01 |

| Plasma fibrinogen, g/L | 3.91 (2.96–4.69) | 3.82 (2.96–4.69) | 4.21 (3.32–4.97) | 0.02 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 185 (140–235) | 187 (142–236) | 172 (127–211) | 0.02 |

| Treatments in hospital, no. (%) | ||||

| Antibiotic | 738 (99) | 660 (98) | 78 (100) | 0.62 |

| Antivirus | 671 (90) | 602 (90) | 69 (89) | 0.73 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 43 (6) | 40 (6) | 3 (4) | 0.61 |

| Anti-platelet | 86 (12) | 73 (11) | 13 (17) | 0.13 |

| LMWH | 186 (25) | 142 (21) | 44 (56) | <0.01 |

| Started prophylaxis dosagec | 109 (59) | 90 (63) | 19 (43) | 0.02 |

| Started therapeutic dosage | 77 (41) | 52 (37) | 25 (57) | |

| Corticosteroids | 158 (21) | 118 (18) | 40 (51) | <0.01 |

| Immune globulin | 367 (49) | 314 (47) | 53 (68) | <0.01 |

| HFNC | 103 (14) | 82 (12) | 21 (27) | <0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| Non-invasive | 258 (34) | 200 (30) | 58 (74) | <0.01 |

| Invasive | 27 (4) | 1 (0.2) | 26 (33) | <0.01 |

| ARDSb | 206 (28) | 148 (22) | 58 (74) | <0.001 |

SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment; WBC=White blood cell; PCT = procalcitonin; HCRP=Hypersensitive c-reactive protein; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; PT = Prothrombin time; aPTT = activated Partial Thromboplastin Time. LMWH = Low molecular weight heparin; HFNC=High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy; ARDS = acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

Continuous variables were summarized as mean (SD) or median (interquartile ranges [IQR]) where appropriate and categorical variables were number (percentage).

Fever was axillary temperature ≥ 37.3 °C. Underlying diseases included any of the following diseases: coronary disease, hypertension, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, chronic kid diseases. ARDS was based on the 2012 Berlin new definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome, including PEEP / CPAP ≥5 cmH2O, PaO2 / FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg.

Among patients starting LMWH for prophylaxis, 19 switched to therapeutic during treatment period.

After 28-day follow-up, 78 (10%) patients had died. The median time to death after admission was 8.5 (4, 16) days in the non-survivors. Baseline characteristics, laboratory findings, and treatments in hospital were compared between survivors and non-survivors (Table 1). At admission, markers for inflammation (white blood cell, procalcitonin, hypersensitive c-reactive protein), renal (creatinine) and liver function (AST) were consistently higher but lymphocyte counts were significantly decreased in non-survivors (all P < 0.01). Coagulopathy markers, i.e., prothrombin time, plasma fibrinogen, aPTT, and D-dimer, but not platelet count, were higher in non-survivors, particularly D-dimer levels. Antimicrobials (Amoxicillin, Azithromycin, Cefamandole, Ceftazidime, Ceftriaxone, Piperacillin-sulbactam, Levofloxacin) were the most common treatment provided for COVID-19 patients. Nearly all received antibiotics (99%) and antiviral medications (90%). LMWH, corticosteroids, intravenous globulins, oxygen, non-invasive and invasive mechanical ventilation were more prevalent in non-survivors. ARDS occurred in 206 (28%) patients during hospitalization, more frequently in non-survivors (74% in non-survivors vs 22% in survivors, P < 0.001). LMWH was administered to 186 (25%) patients. Forty-five patients started LMWH treatment when they were admitted while the others mostly received LMWH within 7 days after admission (Fig. A.2). The median days from admission to LMWH initiation was 3 (1–7) days. Prophylactic dosage was begun for 109 patients while 77 began with therapeutic weight-based dosage.

Clinically relevant bleeding, including major and non-major bleeding, occurred in 6 (0.8%) patients who each received some form of mechanical ventilation. The itemized description of bleeding complications was shown in Table A.1. All six clinically relevant bleeds were gastrointestinal. The incidence of bleeding occurring after non-invasive mechanical ventilation was 1.1% (2/186) in LMWH recipients and 0.18% (1/563) in non-recipients, (P = 0.15).

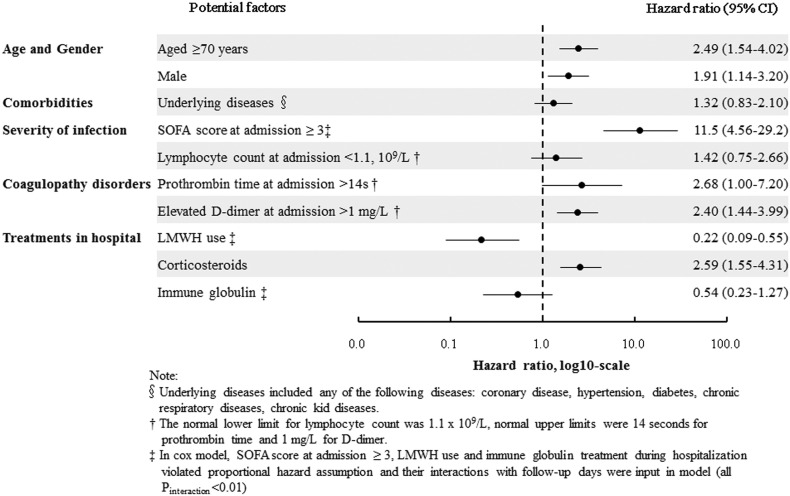

In Cox multivariable analysis, LMWH emerged as an independent factor for decreased 28-day death (Hazard Ratio [HR] 0.22, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.09–0.55). Age over 70 years, male gender, SOFA score ≥ 3, elevated D-dimer at admission and corticosteroid therapy were significantly associated with increased death risk (Fig. 1 ). Similar results were observed in univariable analysis (Table A.2). Analyzing the relationship between disease severity and anticoagulation on mortality, LMWH use was associated with decreased mortality in the subgroup of patients with SOFA score ≥ 3 [0.17 (0.06–0.43)] (Table A.3). The interaction was statistically significant (p < 0.01), suggesting SOFA might play a role in the influence of LMWH treatment on mortality.

Fig. 1.

Factors associated with 28-day mortality in multivariable Cox regression analysis

Note: X axis values were hazard ratios, log10-scale.

§Underlying diseases included any of the following diseases: coronary disease, hypertension, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, chronic kid diseases.

† The normal lower limit for lymphocyte count was 1.1 × 109/L, normal upper limits were 14 s for prothrombin time and 1 mg/L for D-dimer.

‡ In cox model, SOFA score at admission ≥3, LMWH use and immune globulin treatment during hospitalization violated proportional hazard assumption and their interactions with follow-up days were input in model (all Pinteraction < 0.01).

Individuals with elevated D-dimer at admission had a poorer prognosis [2,3] and anticoagulant therapy may improve their survival. In this pragmatic study, LMWH treatment was administered at the discretion of physicians and disproportionately delivered to elderly male patients with higher SOFA score and elevated D-dimer. Given the potential bias due to non-randomized nature of observational study, we constructed a diagram (Fig. A.1) with unidirectional arrows to present causal effects on COVID-19 and performed a hypothesis-driven analysis according to the guideline on casual inference in observational studies [4]. The protective association between LMWH and mortality suggested survival benefit of anticoagulation. The decrease in death risk might be attributable to LMWH's anticoagulant and other pleiotropic effects [5]. Other treatments like corticosteroids were mainly delivered to older male patients. Patients receiving corticosteroid treatment had increased death risk, consistent with a prior report of a nearly three-fold increase in death compared to patients not receiving steroid [6]. In our study, corticosteroid recipients were at a significant 2.59-fold increased death risk. While some researchers advocate against corticosteroid use for COVID-19 [7], whereas other experts recommended it [8]. In a randomized clinical trial, dexamethasone use resulted in lower 28-day mortality among patients receiving either invasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen alone [9]. For immunoglobulin therapy, also routinely administered in our study, there was an insignificant trend toward decreased death. Elsewhere, a case series demonstrated recovery of debilitated COVID-19 patients after early high-dose immunoglobulin [10]. In our observational cohort study conducted early in the epidemic era, LMWH, given at prophylactic dosage, was the predominant anticoagulant for COVID-19 patients and associated with survival. Whether early routine LMWH use, perhaps at higher dosage, would promote increased survival and limit massive D-dimer increases, is being tested in ongoing studies.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

2019 Coronavirus Disease

- LMWH

low molecular weight heparin

- PT

prothrombin time

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

- PCR

transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SOFA

sequential organ failure assessment

- aPTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- UFH

unfractionated heparin

- WBC

white blood cell

- PCT

procalcitonin

- HCRP

Hypersensitive c-reactive protein

- PT

Prothrombin time

- HFNC

high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy

- ARDS

acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of Jianghan University Affiliated Hospital and China-Japan Friendship Hospital (WHSHIRB-K-2020015). Before data collection, we obtained patients' consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data and relevant materials are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Chinese Academy of Engineering emergency research and cultivation project for COVID-19 (2020-KYGG-01-05), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC0905600; 2016YFC0901104), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (No. 2018-I2M-1-003) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570049; 81970058). The funding bodies are not involved in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author contributions

WQ, FD, ZZ, BH, SC, ZZ and CL conceived the study. WQ, BH, SC, ZZ, FL, XW, YZ, YW, KZ, and JW collected data. WQ, FD, ZZ, IE, CL, ZZ, and BD analyzed and interpreted data. WQ, FD, ZZ, BH, and SC drafted the manuscript. IE, CL, ZZ, BD, CW revised the manuscript. ZZ, CL, CW obtained funding and supervised the study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Min Liu, ZiMing Wang, Di Xu, Wei Yu, Wei Wan, Chong Zhang, and JiaQi Wang from Affiliated Hospital of Jianghan University, for their data collection. They were not compensated for their contributions. The authors also thank Prof Bin Cao for providing suggestions and support for the development of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Connors J.M., Levy J.H. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033–2040. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li C., Hu B., Zhang Z. D-dimer triage for COVID-19. Acad. Emerg. Med. Off. J. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020;27:612–613. doi: 10.1111/acem.14037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed S., Zimba O., Gasparyan A.Y. Thrombosis in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) through the prism of Virchow’s triad. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020;39:2529–2543. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05275-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lederer D.J., Bell S.C., Branson R.D. Control of confounding and reporting of results in causal inference studies. Guidance for authors from editors of respiratory, sleep, and critical care journals. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019;16:22–28. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-564PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whyte C.S., Morrow G.B., Mitchell J.L. Fibrinolytic abnormalities in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and versatility of thrombolytic drugs to treat COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1548–1555. doi: 10.1111/jth.14872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayerbe L., Risco C., Ayis S. The association between treatment with heparin and survival in patients with Covid-19. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell CD, Millar JE and Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395:473–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Shang L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395:683–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;(NEJMoa2021436) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao W, Liu X, Bai T, et al. High-Dose Intravenous Immunoglobulin as a Therapeutic Option for Deteriorating Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Open forum infectious diseases. 2020;7:ofaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data and relevant materials are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.