Abstract

TBC1 domain containing kinase (TBCK) protein is composed of three conserved domains, including N-terminal Serine/Threonine kinase domain, central TBC domain and C-terminal rhodanese homology domain (RHOD). A total of 9 different transcripts (classified as long and short TBCK) generated by alternative splicing have been reported in different cell lines. Exogenous expression of long TBCK has been identified to function as a suppressor of cell growth in certain cell types. On the contrary, TBCK has also been reported to serve a tumor-promoting role in other cell lines, indicating that TBCK might function differentially, depending on the context in different cellular environments. Furthermore, deleterious homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations identified by whole-exome sequencing in the TBCK gene could ablate the function of TBCK, further impacting the mTOR signaling pathway and leading to neurogenetic disorders, such as hypotonia, global developmental delay, facial dysmorphic features and brain abnormalities. However, as a poorly explored protein, there are a lot of studies associated with the functions of TBCK that need to be performed in the future. The present review summarizes data regarding the structural features and potential roles of TBCK in developmental and neurological diseases and tumorigenesis. Future prospects of TBCK research lie in revealing numerous biological functions of TBCK.

Keywords: TBC1 domain containing kinase, alternative splicing, mutation, neurogenetic disorders, tumorigenesis

1. Introduction

TBC1 domain containing kinase (TBCK), also known as hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells 302 (HSPC302) or Mammalian Gene Collection 16169 (MGC16169), was initially discovered in CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. It was then reported in the NEDO human cDNA sequencing project by researchers at the University of Tokyo (1,2). At that time, TBCK was considered a hypothetic protein with unknown functions. Since then, several groups have provided mRNA and peptide data of TBCK in different cell types. Resing et al (3) in 2004 identified 5130 proteins in the K562 cell line with high throughput shotgun proteomics, including two peptides of TBCK; Tanner et al (4) in 2007 also identified the expression of TBCK in HEK293 cell line with peptide mass spectrometry.

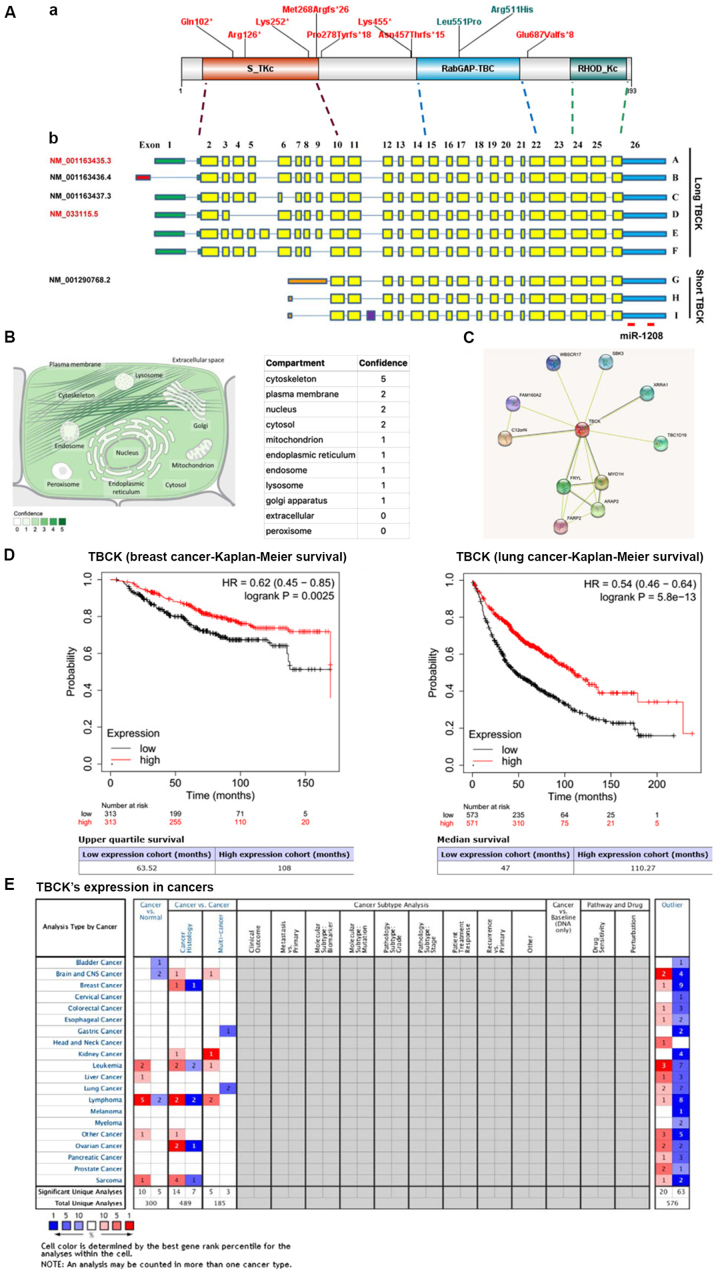

It has been shown that TBCK comprised three putative structural domains: S_TKc, TBC (Tre-2, Bub2 and Cdc16) and RHOD_Kc (5,6). TBCK included two types of alternatively spliced isoforms (long TBCK and short TBCK). Long TBCK comprised all the three conserved motifs, while short TBCK only comprised TBC and RHOD_Kc domains (Fig. 1A and B). At present, most of the TBCK-related research focuses on the relationship between TBCK gene mutations and neuronal development disorders. Our previous results have demonstrated TBCK's expression in a cell type-specific manner. The proteins produced by the two alternative isoforms contribute to differential functions of TBCK. In the following section, we will summarize the detailed gene structure, protein expression of TBCK and the important roles of TBCK in human diseases including cancers.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of TBCK gene and protein, and potential roles in predicting the prognosis of patients with breast and lung cancer. (A) Schematic representation of the two categories of TBCK isoforms and the matching functional domains. (a) A diagram of TBCK including known domains and the variants presented in this manuscript. (b) The 5′UTRs are shown as colored bars. Transcripts A/C/D/E/F share the same 5′UTR region (308 bp; green), while Transcript B (NM_001163436.4) has a relatively shorter 5′UTR region (165 bp; red). Besides, for short TBCK, they have different 5′UTR regions (orange). Differential transcription initiations and the 3′UTRs are shown as blue bars. Separated by introns shown by blue lines, exons are indicated by solid rectangles with yellow for known exons and purple for a newly-identified exon. A total of five transcripts are listed in the NCBI database with indicated accession numbers. One currently identified miRNA was matched to the 3′UTR region of TBCK mRNA. (B) Subcellular locations from COMPARTMENTS. The subcellular localizations are derived from database annotations, automatic text mining of the biomedical literature and sequence-based predictions. (C) Candidate interaction partners of TBCK were identified using STRING. (D) In breast and lung cancer tissues in the Kaplan-Meier Plotter database, high TBCK expression was associated with good prognosis. (E) Oncomine enabled the systematic analysis of TBCK expression in multiple cancer types. HR, hazard ratio; miR, microRNA; TBCK, TBC1 domain containing kinase; UTR, untranslated region.

2. General properties of TBCK

Molecular features of TBCK

TBCK is commonly and abundantly expressed in mammalian cells according to the human protein atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000145348-TBCK/summary/rna) (7–9). Based on an in silico analysis, homologues of TBCK in 12 Bilateria, and the conservation of these homologues was quite high. The percentage of protein identity in the top 7 species surpassed 90% (Table I), indicating that TBCK might participate in important activities.

Table I.

Homologues of TBCK in different species.

| Gene Species | Identity, % Symbol | Protein | DNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. sapiens | TBCK | ||

| vs. P. troglodytes | TBCK | 99.6 | 99.4 |

| vs. M. mulatta | TBCK | 97.2 | 97.0 |

| vs. C. lupus | TBCK | 96.8 | 93.2 |

| vs. B. taurus | TBCK | 96.5 | 92.7 |

| vs. M. musulus | Tbck | 95.4 | 89.1 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Tbck | 94.1 | 87.6 |

| vs. G. gallus | TBCK | 87.2 | 79.2 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | tbck | 81.5 | 73.9 |

| vs. D. rerio | tbck | 76.7 | 69.2 |

| vs. D. melanogaster | CD4041 | 47.9 | 49.3 |

| vs. A. gambiae | AgaP_AGAP000552 | 46.3 | 47.5 |

| vs. C. elegans | Tbck-1 | 33.9 | 44.9 |

TBCK, TBC1 domain containing kinase.

TBCK has three separate functional domains: N-terminal Serine/Threonine kinase domain, central TBC domain, and C-terminal rhodanese homology domain (RHOD). It has been reported that the kinase domain could bind GTP and possessed protein kinase activities (10). TBCK was discovered to possess the ability to selectively support coupling of active EGFR to ERK1/2 regulation (11) and positively correlated highly with rapamycin activity, indicating that TBCK might be a Serine/Threonine protein kinase (12). The TBC domain was identified as a conserved sequence in the three proteins including Tre-2, BUB2p and Cdc16p. These proteins have been proven to be functional domains of Rab GAP, which could catalyze GTP hydrolysis of Rab GTPase via a dual-finger mechanism (13). For containing the conserved TBC domain, TBCK was considered to be a member of the RabGAP family. However, a yeast two-hybrid assay showed that TBCK had no physical interaction with any one of the 60 known Rab proteins (14). The RHOD domain is a homologous domain of rhodanese, but little is known about its function.

According to the NCBI Core Nucleotide and UCSC Genome Browser database, 6 TBCK transcripts were listed. Jin and his colleagues have provided evidence for these transcripts in 4 different cell types (A431, HeLa, HepG2 and HEK293FT) using multiple primer sets covering the whole ORF region of TBCK. Furthermore, three more transcripts were identified and all isoforms were categorized as long and short types based on the mRNA sequence. The long isoforms (6 members) contained STYKc kinase, TBC, and RHOD domains, whereas the short isoforms (3 members) lacked the region of STYKc kinase. These two distinctive types were most likely products of differential transcription initiation (Fig. 1A) (6). Although the proteins representing the short isoforms of TBCK were not recognized in the above-mentioned four cell types, additional bands with a similar molecular mass were observed in HepG2 and HEK293FT cells, which were possibly generated by alternative splicing or post-translational modifications (6). Moreover, Chong et al (15) demonstrated that two major bands with molecular weights of ~101 and 71 kDa, which represented long and short TBCK respectively, were observed in two control fibroblast lines, and the full-length isoform was more abundant than the short TBCK.

Distribution and interaction partners of TBCK in mammalian cells

It has been approximately 7 years since the first protein evidence for TBCK was raised (5). Immunofluorescence analysis for endogenous TBCK revealed that TBCK was clearly colocalized with γ-tubulin in addition to punctate distribution in HEK293 cells. TBCK appeared to be not substantially colocalized with the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi and endosomes in both HEK293 and HeLa cells (5). However, GFP-tagged TBCK showed cell cycle-dependent distribution in HeLa cells. TBCK is mainly localized in the cytoplasm during interphase, while a portion of TBCK accumulated at the mitotic apparatus and colocalized with centrosomes and spindle fibers as shown by the fluorescent staining of α-tubulin. At the end of mitosis, a clear midbody staining of TBCK was usually observed between the two daughter cells (6). These inconsistent results might be due to the specificity of the chosen TBCK antibody. The TBCK antibody used in 2013 was generated by KLH conjugated peptide (LFEDGESFGQGRDRSSLLDDT), which was located adjacent to GAP domain and was not suitable for distinguishing the long and short isoforms of TBCK. GFP-tagged TBCK only reflected the distribution of long isoforms of TBCK.

Moreover, TBCK was also probably localized to plasma membrane, nucleus, and mitochondrion according to the COMPARTMENTS subcellular localization database (https://compartments.jensenlab.org/Entity?figures=subcell_cell_%%&knowledge=10&textmining=10&predictions=10&type1=9606&type2=−22&id1=ENSP00000273980) (Fig. 1B) (16).

As a poor-explored protein, no evidence has been raised for identifying the interaction partners of TBCK. Based on the public STRING database (https://string-db.org/cgi/network.pl?taskId=K08rYosvQxGl), several proteins exhibited higher possibility to be interaction partners of TBCK (Fig. 1C) (17–26). Besides, our recent research has uncovered 17 candidate proteins of TBCK using RNAi-mediated TBCK silencing in combination with 2-DE-DIGE assays (data not shown). These candidates played important roles in multiple activities, such as protein folding, post-translational modification, and the cytoskeleton. These candidates await further investigation.

3. TBCK and neurodevelopmental diseases

Although there is a long way to go to fully understand the function of TBCK, recent research indicates that TBCK plays an important role in brain development. Mutations to the TBCK gene could cause neurological developmental disorders. Until now, a total of 17 mutations were reported to be associated with neurodevelopmental diseases (Fig. 1A and Table II).

Table II.

Characteristics of TBCK mutations associated with neurogenetic disorders.

| Author, year | Disease type | Research target | Research approach | Variation of TBCK | Mapping region | Mutation type | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alazami et al, 2015 | Neurogenetic disorders | 143 multiplex consanguineous families | Whole-exome sequencing | NM_033115: c.1708+1G>A | RabGap-TBC | Splicing (frameshift) | (27) |

| Bhoj et al, 2016 | Syndrome of intellectual disability and hypotonia | 13 individuals from nine unrelated families | Whole-exome sequencing | NM_001163435.2: c.1897+1G>A; | RabGap-TBC | Splicing (frameshift) | (28) |

| c.831_832insTA | NA | Insertion | |||||

| (p.Pro278Tyrfs*18) | (frameshift) | ||||||

| c.1652T>C | RabGap-TBC | Missense | |||||

| (p.Leu551Pro) | |||||||

| c.[2060-2A>G] | NA | Splicing | |||||

| (frameshift) | |||||||

| c.803_806delTGAA, p.[=];[Met268fsArg*26] | S_TKc | Frameshift | |||||

| c.376C>T (p.Arg126*) | S_TKc | Nonsense | |||||

| c.1370delA | NA | Frameshift | |||||

| (p.Asn457Thrfs*15) | S_TKc | Splice | |||||

| c.455+4 C>G | (skipping of exons 3 and 4) | ||||||

| c.[(658+1_659-1)_(2059+1_2060-1) del] | S_TKc | Deletion of exons 7–22 | |||||

| Chong et al, 2016 | Infantile syndromic encephalopathy | Four unrelated families | Whole-exome sequencing | c.376C>T (p.Arg126*) | S_TKc | Nonsense | (15) |

| c.1363A>T | RabGap-TBC | Nonsense | |||||

| [p.Lys455*] | |||||||

| c.1532G>A | RabGap-TBC | Missense | |||||

| (p.Arg511His) | |||||||

| Guerreiro et al, 2016 | Recessive developmental disorder | A family with 3 siblings affected by a severe, yet viable, congenital disorder | Whole-genome genotyping and whole-exome sequencing | NM_033115: c.614_617del: p.205_206del | S_TKc | Frameshift | (29) |

| Mandel et al, 2017 | TBCK-related intellectual disability syndrome | Two siblings born to an Arab-Moslem family living in northern Israel | Whole-exome sequencing | NM_001163435.2: c.1854delT | RabGap-TBC | Frameshift | (30) |

| Ortiz-Gonzalez et al, 2018 | TBCK-encephalo-neuronopathy | Children (n=8) of Puerto Rican (Boricua) descent affected with homozygous TBCK p.R126X mutations | Whole-exome sequencing | c.376C>T (p.Arg126*) | S_TKc | Nonsense | (37) |

| Zapata-Aldana et al, 2019 | TBCK-infantile hypotonia | A family with two siblings who presented with a novel TBCK mutation | Whole-exome sequencing | NM_001163435.2: c.753dup; p.(Lys252*) | S_TKc | Nonsense | (31) |

| Beck-Wodl et al, 2018 | New type of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis | Two siblings born in 1972 and 1974 suffering from the disease | Sanger sequencing/whole exome sequencing | NM_001163435.2: c.304C >T, p.(Gln102*) | S_TKc | Nonsense | (32) |

| Sumathipala et al, 2019 | TBCK encephalo-neuropathy | A family with two siblings who presented with a novel TBCK mutation | Whole genome sequencing | p.Glu687Valfs*8 | NA | Splicing (frameshift) | (33) |

| Tsang et al, 2020 | Pediatric-onset mitochondrial diseases | A family with two siblings who presented with a novel TBCK mutation | Whole genome sequencing | c.976dupT, p.(Tyr326Leufs*10) | NA | Missense | (35) |

| 66 patients with pre-biopsy MDC scores of 3–8 were recruited | Whole-exome sequencing | c.478G>T, p.(Glu160*) | S_TKc | Nonsense | |||

| Saredi et al, 2020 | Muscle disease and severe psychomotor delay | Two sisters diagnosed with muscle disease and severe psychomotor delay | Whole-exome sequencing | c.535_554del, p.(Leu179ArgfsTer10) | S_TKc | Missense | (34) |

| Hartley et al, 2018 | Inherited peripheral neuropathies | A cohort of 50 families affected individuals with a molecularly undiagnosed IPN features | Whole genome sequencing | c.1652T>C (p.Leu551Pro) | RabGap-TBC | Missense | (36) |

NM_001163435.2, isoform a of TBCK; NM_033115, isoform d of TBCK. TBCK, TBC1 domain containing kinase; MDC, mitochondrial disease criteria; IPN, inherited peripheral neuropathy.

Most of the mutations were nonsense mutations, generating premature stop codons. After categorization, it can be found that 73.3% (11/15) of mutations were located in the region containing the first two domains, affecting the translation of full-length TBCK. It is worth noting that the two missense mutations happened in the RabGap domain, indicating that the RabGap domain might be the most important functional unit for proper brain development. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms still remain unknown.

Alazami et al (27) identified 69 genes related to neurogenic diseases through whole exome sequencing of 143 multiplex consanguineous families, of which an insertion mutation at 1709ntin the TBCK coding region was verified to cause a frameshift and further influence disease progression. This insertion was also detected in 13 individuals from nine unrelated families, likely being pathogenic variants of TBCK. Eight other mutations of the TBCK gene were reported to be the main cause of mental retardation and hypotonic syndrome, and L-type leucine-mediated activation of the mTOR signaling pathway helped alleviate related symptoms (28). In the meantime, another group verified two novel mutations of TBCK genes (c.1363A>T [p.Lys455*] and c.1532G>A [p.Arg511His) via whole-exome sequencing of infants with encephalopathy in 4 unrelated families, of which the former mutation would induce a stop codon and lead to the deletion of long TBCK, while the latter mutation was located in the TBC conserved domain and might affect the RabGap activity of TBCK (15). Unlike the overgrowth of the brain caused by mTOR pathway disorders, a gradually decrease of the brain volume of infants with encephalopathy would be caused by TBCK deficiency (29). Furthermore, six more mutations (either resulting in nonsense or frameshift) affecting the TBCK expression were reported by six different groups (Table II) (30–35).

It should be noted that four common mutations have been reported in different patients from at least two different groups (Table II): c.1897+1G>A (27,28); c.1652T>C (28,36); c.803_806delTGAA (28,29); and c.376C>T (15,28,37). All of the mutations would ablate the expression of full-length TBCK and cause TBCK-related developmental and neurological diseases. However, TBCK function has been poorly explored. Previous research shows that TBCK played a role in cell growth and actin organization by enhancing the signaling pathways of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), presumably at a transcriptional or post-transcriptional level (5). Besides, TBCK deficiency would disturb activation of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), thus, affecting the autophagy process and further leading to autophagosomal-lysosomal dysfunction (37). Nevertheless, does TBCK directly or indirectly affect the mTOR signaling pathway? Which domain contributes the most? What are the binding partners of TBCK? These open questions await further studies.

4. TBCK and tumorigenesis

TBCK was expressed universally in almost all human tissues, except a relatively low expression in heart, brain, skeletal muscle, and peripheral blood leukocytes (data not shown). Besides, TBCK was proven to be down-regulated in 55.6% of paired gastric carcinoma and 75.0% pair-matched esophageal carcinomas. Overexpression of TBCK in HeLa cells could remarkably inhibit cell growth and arrest cells at S phase, which was indicative of tumor suppressive function (6). After analyzing the clinical information collected from TCGA, the five-year survival rates for patients with high-level TBCK was significantly higher than that of patients with low-level TBCK in renal cancer (P=3.20E-4) and pancreatic cancer (P=3.67E-2). A similar phenomenon could be found in breast cancer (P=2.50E-3) and lung cancer (P=4.70E-13) (Fig. 1D) using Kaplan-Meier Plotter database [https://kmplot.com/analysis/] (38). This implied that TBCK might also possess the potential to be a viable prognosis marker for treatment of some cancer types.

However, TBCK might also exhibit tumor-promoting functions in certain cancer types. Based on the Oncomine database (Fig. 1E), it has been shown that TBCK exhibit the tumor-promoting functions in leukemia, lymphoma, liver cancer and sarcoma, in addition, individual experiments also validated that exhibit the functions in squamous cell carcinoma and renal cancers (11,39). In a human kinase mapping study using the entire kinome siRNA library targeting over 600 related genes, TBCK-specific RNAi decreased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and increased the phosphorylation of STAT3. TBCK was further proven to selectively support coupling of active EGFR to ERK1/2 regulation (11). A very recent study on TBCK showed that TBCK was a direct target of miR-1208, and that the miR-1208/TBCK interaction had an important role in the regulation of apoptosis, as well as in the enhancement of cisplatin or TRAIL sensitivities in renal cancer cells (39). However, how TBCK involved in both tumor promotion and inhibition in different cancer types is unknown, and requires further investigation.

5. Future prospects of TBCK research

Previous results indicated that the eukaryotic protein kinase comprised of 12 essential conserved subdomains to maintain its kinase activity (40). Due to its lack of two important motifs (GXGXXG motif and VAIK motif) responsible for ATP binding, and the replacement of those motifs with mutated HRD motif that was essential for catalytic activity, TBCK was considered a pseudokinase (5,41,42). Itis implied that TBCK might phosphorylate the ERK1/2 protein (11). However, further direct kinase assays should be performed to clarify whether TBCK has kinase activity or not. The positive answer also provides evidence for differential functions between long and short isoforms of TBCK (6).

TBC domain-containing proteins usually function as a RabGap (Rab GTPase-activating protein) to negatively regulate Rab functions through accelerating GTP hydrolysis via a ‘dual-finger’ mechanism (13,43–45). Although the crystallographic structure of TBCK has not been reported, Chong et al (15) generated a homology model of the TBC1 domain of TBCK using DeepView and the SwissModel server (46) and uncovered a structural impact of the disease-causing amino acid substitution (p.Arg511His). Other reports also demonstrated that the TBC domain in TBCK included the key conserved amino acid residues required for RabGAP activity in functional RabGAPs (5,13). However, the direct substrate of TBCK was failed to be identified in a systematical screening for target Rabs (60 Rab proteins) of TBC domain-containing proteins (40 proteins including TBCK) based on their Rab-binding activity (14). Thus, it is necessary to carry out critical experiments to figure out the physiological target of TBCK, which shall provide direct evidence for the RabGap activity of TBCK.

In addition, previous studies have shown that TBCK mutations would cause neurogenetic disorders. The mTOR pathway and mTOR-mediated autophagy might play important roles in such processes (28,37). However, it is still unclear how TBCK affects the mTOR signaling pathway, what the interacting proteins of TBCK are and whether there are other pathways involved remains unsolved. Our current research has uncovered 17 candidate proteins of TBCK using RNAi-mediated TBCK silencing in combination with 2-DE-DIGE assays. These candidates played important roles in multiple activities, such as protein folding, post-translational modification, and the cytoskeleton etc. (data not shown). More work on the mechanism of action needs to be completed in order to clearly clarify the roles of TBCK in neurogenetic disorders and tumor development.

6. Concluding remarks

An important finding for TBCK function in recent years was that TBCK functions as a candidate RabGAP. Deleterious mutations of TBCK would ablate the function of TBCK and cause severe infantile syndromic encephalopathy or other neurogenetic disorders. These mutation sites were found in the whole exons covering three conserved domains. Abnormal function of TBCK would destroy the mTOR signaling pathway and its mTOR-mediated autophagy process, which was considered the major cause of TBCK-related neurogenetic disorders. In addition, two types of TBCK isoforms were verified, and the kinase domain might account for the functional differences among TBCK isoforms. Limited research also suggested that the distribution of TBCK was cell cycle-dependent, and the role of TBCK in tumors was cell line-dependent. Overall, the function of TBCK is poorly explored and awaits further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Alexander Caradori (Center for Genetics and Pharmacology, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Cente) for providing constructive suggestions and manuscript proofreading.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81101490 to GL).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JW and GL wrote the manuscript and performed article revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Yudate HT, Suwa M, Irie R, Matsui H, Nishikawa T, Nakamura Y, Yamaguchi D, Peng ZZ, Yamamoto T, Nagai K, et al. HUNT: Launch of a full-length cDNA database from the Helix Research Institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:185–188. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T, Sugiyama T, Irie R, Wakamatsu A, Hayashi K, Sato H, Nagai K, et al. Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs. Nat Genet. 2004;36:40–45. doi: 10.1038/ng1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resing KA, Meyer-Arendt K, Mendoza AM, Aveline-Wolf LD, Jonscher KR, Pierce KG, Old WM, Cheung HT, Russell S, Wattawa JL, et al. Improving reproducibility and sensitivity in identifying human proteins by shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:3556–3568. doi: 10.1021/ac035229m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanner S, Shen Z, Ng J, Florea L, Guigó R, Briggs SP, Bafna V. Improving gene annotation using peptide mass spectrometry. Genome Res. 2007;17:231–239. doi: 10.1101/gr.5646507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Yan X, Zhou T. TBCK influences cell proliferation, cell size and mTOR signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu J, Li Q, Li Y, Lin J, Yang D, Zhu G, Wang L, He D, Lu G, Zeng C. A long type of TBCK is a novel cytoplasmic and mitotic apparatus-associated protein likely suppressing cell proliferation. J Genet Genomics. 2014;41:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uhlén M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjöstedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, Benfeitas R, Arif M, Liu Z, Edfors F, et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science. 2017;357:eaan2507. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thul PJ, Akesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Blal HA, Alm T, Asplund A, Björk L, Breckels LM, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science. 2017;356:eaal3321. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komurov K, Padron D, Cheng T, Roth M, Rosenblatt KP, White MA. Comprehensive mapping of the human kinome to epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21134–21142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen G, Yang N, Wang X, Zheng SY, Chen Y, Tong LJ, Li YX, Meng LH, Ding J. Identification of p27/KIP1 expression level as a candidate biomarker of response to rapalogs therapy in human cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:941–952. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan X, Eathiraj S, Munson M, Lambright DG. TBC-domain GAPs for Rab GTPases accelerate GTP hydrolysis by a dual-finger mechanism. Nature. 2006;442:303–306. doi: 10.1038/nature04847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh T, Satoh M, Kanno E, Fukuda M. Screening for target Rabs of TBC (Tre-2/Bub2/Cdc16) domain-containing proteins based on their Rab-binding activity. Genes Cells. 2006;11:1023–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chong JX, Caputo V, Phelps IG, Stella L, Worgan L, Dempsey JC, Nguyen A, Leuzzi V, Webster R, Pizzuti A, et al. University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics Recessive inactivating mutations in TBCK, encoding a rab GTPase-activating protein, cause severe infantile syndromic encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binder JX, Pletscher-Frankild S, Tsafou K, Stolte C, ODonoghue SI, Schneider R, Jensen LJ. COMPARTMENTS: Unification and visualization of protein subcellular localization evidence. Database (Oxford) 2014 Feb 25; doi: 10.1093/database/bau012. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1093/database/bau012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M, Wyder S, Simonovic M, Santos A, Doncheva NT, Roth A, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, et al. STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C, et al. STRING v9.1: Protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: Functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, et al. STRING 8 - a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Chaffron S, Doerks T, Krüger B, Snel B, Bork P. STRING 7 - recent developments in the integration and prediction of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D358–D362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Snel B, Hooper SD, Krupp M, Foglierini M, Jouffre N, Huynen MA, Bork P. STRING: Known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D433–D437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Mering C, Huynen M, Jaeggi D, Schmidt S, Bork P, Snel B. STRING: A database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:258–261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snel B, Lehmann G, Bork P, Huynen MA. STRING: A web-server to retrieve and display the repeatedly occurring neighbourhood of a gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3442–3444. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alazami AM, Patel N, Shamseldin HE, Anazi S, Al-Dosari MS, Alzahrani F, Hijazi H, Alshammari M, Aldahmesh MA, Salih MA, et al. Accelerating novel candidate gene discovery in neurogenetic disorders via whole-exome sequencing of prescreened multiplex consanguineous families. Cell Rep. 2015;10:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhoj EJ, Li D, Harr M, Edvardson S, Elpeleg O, Chisholm E, Juusola J, Douglas G, Guillen Sacoto MJ, Siquier-Pernet K, et al. Mutations in TBCK, encoding TBC1-domain-containing kinase, lead to a recognizable syndrome of intellectual disability and hypotonia. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guerreiro RJ, Brown R, Dian D, de Goede C, Bras J, Mole SE. Mutation of TBCK causes a rare recessive developmental disorder. Neurol Genet. 2016;2:e76. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandel H, Khayat M, Chervinsky E, Elpeleg O, Shalev S. TBCK-related intellectual disability syndrome: Case study of two patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173:491–494. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zapata-Aldana E, Kim DD, Remtulla S, Prasad C, Nguyen CT, Campbell C. Further delineation of TBCK - Infantile hypotonia with psychomotor retardation and characteristic facies type 3. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck-Wödl S, Harzer K, Sturm M, Buchert R, Riess O, Mennel HD, Latta E, Pagenstecher A, Keber U. Homozygous TBC1 domain-containing kinase (TBCK) mutation causes a novel lysosomal storage disease - a new type of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (CLN15)? Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:145. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0646-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sumathipala D, Strømme P, Gilissen C, Corominas J, Frengen E, Misceo D. TBCK encephaloneuropathy with abnormal lysosomal storage: Use of a structural variant bioinformatics pipeline on whole-genome sequencing data unravels a 20-year-old clinical mystery. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;96:74–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saredi S, Cauley ES, Ruggieri A, Spivey TM, Ardissone A, Mora M, Moroni I, Manzini MC. Myopathic changes associated with psychomotor delay and seizures caused by a novel homozygous mutation in TBCK. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62:266–271. doi: 10.1002/mus.26907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsang MH, Kwong AK, Chan KL, Fung JL, Yu MH, Mak CC, Yeung KS, Rodenburg RJ, Smeitink JA, Chan R, et al. Delineation of molecular findings by whole-exome sequencing for suspected cases of paediatric-onset mitochondrial diseases in the Southern Chinese population. Hum Genomics. 2020;14:28. doi: 10.1186/s40246-020-00278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartley T, Wagner JD, Warman-Chardon J, Tétreault M, Brady L, Baker S, Tarnopolsky M, Bourque PR, Parboosingh JS, Smith C, et al. FORGE Canada Consortium; Care4Rare Canada Consortium Whole-exome sequencing is a valuable diagnostic tool for inherited peripheral neuropathies: Outcomes from a cohort of 50 families. Clin Genet. 2018;93:301–309. doi: 10.1111/cge.13101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ortiz-González XR, Tintos-Hernández JA, Keller K, Li X, Foley AR, Bharucha-Goebel DX, Kessler SK, Yum SW, Crino PB, He M, et al. Homozygous boricua TBCK mutation causes neurodegeneration and aberrant autophagy. Ann Neurol. 2018;83:153–165. doi: 10.1002/ana.25130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagy Á, Lánczky A, Menyhárt O, Győrffy B. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim EA, Jang JH, Sung EG, Song IH, Kim JY, Lee TJ. MiR-1208 increases the sensitivity to cisplatin by targeting TBCK in renal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3540. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanks SK, Hunter T. Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: Kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 1995;9:576–596. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.8.7768349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boudeau J, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ, Alessi DR. Emerging roles of pseudokinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheeff ED, Eswaran J, Bunkoczi G, Knapp S, Manning G. Structure of the pseudokinase VRK3 reveals a degraded catalytic site, a highly conserved kinase fold, and a putative regulatory binding site. Structure. 2009;17:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barr F, Lambright DG. Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gavriljuk K, Gazdag EM, Itzen A, Kötting C, Goody RS, Gerwert K. Catalytic mechanism of a mammalian Rab·RabGAP complex in atomic detail. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:21348–21353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214431110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:269–309. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Gallo Cassarino T, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, et al. SWISS-MODEL: Modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.