Abstract

Background and Objectives

Nursing homes are intended for older adults with the highest care needs. However, approximately 12% of all nursing home residents have similar care needs as older adults who live in the community and the reasons they are admitted to nursing homes is largely unstudied. The purpose of this study was to explore the reasons why lower-care nursing home residents are living in nursing homes.

Research Design and Methods

A qualitative interpretive description methodology was used to gather and analyze data describing lower-care nursing home resident and family member perspectives regarding factors influencing nursing home admission, including the facilitators and barriers to living in a community setting. Data were collected via semistructured interviews and field notes. Data were coded and sorted, and patterns were identified. This resulted in themes describing this experience.

Results

The main problem experienced by lower-care residents was living alone in the community. Residents and family members used many strategies to avoid safety crises in the community but experienced multiple care breakdowns in both community and health care settings. Nursing home admission was a strategy used to avoid a crisis when residents did not receive the needed support to remain in the community.

Discussion and Implications

To successfully remain in the community, older adults require specialized supports targeting mental health and substance use needs, as well as enhanced hospital discharge plans and improved information about community-based care options. Implications involve reforming policies and practices in both hospital and community-based care settings.

Keywords: Social isolation, Mental health, Caregiving—informal, Long-term care, Qualitative research methods

Background and Objectives

Aging in place, or the ability to remain living in the home of one’s choice, is challenged when older adults experience declines in health, changes in their ability to complete activities of daily living tasks and to maintain their home environment (Callahan, 1992; Fausset, Kelly, Rogers, & Fisk, 2011), and experience an absence of informal support (Ryser & Halseth, 2011). Supporting older adults to age in place requires health care and community service planners to effectively organize and deliver various services (e.g., home care, meal delivery, and mental health support) and/or housing options with these services in place (i.e., assisted living facilities). The ineffective delivery of these supports and services is associated with the increased use of emergency departments and hospitals (Pallin, Allen, Espinola, Camargo, & Bohan, 2013), complicated hospital discharge processes (Halasyamani et al., 2006), and increased levels of patient dissatisfaction (Bull, Hansen, & Gross, 2000). Furthermore, and of interest to this study, challenges with these supports and services often result in earlier admissions to nursing homes than would usually be expected, and previous research demonstrates that about 12% of nursing home residents have clinical needs (e.g., activities of daily living, cognitive, behavioral, and continence) similar to community-dwelling people (Doupe et al., 2012; McNabney, Wolff, Semanick, Kasper, & Boult, 2007). Although these early nursing home admissions may benefit some older adults (Clay, 2001), the reasons for early admissions are largely unstudied.

The current evidence is largely a quantitative description of nursing home resident profiles, yet quantitative methods do not address the process experienced by residents as they move between community-based housing and nursing homes, nor do these studies explain why these individuals seek nursing home placements. The reasons why residents move, and the processes they experience during this transition, can be captured and explained by using qualitative research methods, thus filling the gap in knowledge about this human experience. As a result, we designed a qualitative study to explore lower-care residents’ and their family members’ perspectives describing why these residents were admitted to nursing homes, what they would have needed to live longer in the community, and the experience of being admitted to a nursing home. Our research questions included: (a) What factors influenced lower-care residents being admitted to nursing homes? and (b) What were the facilitators and barriers to living in a community setting? Collectively, the responses to these questions can help planners to develop aging-in-place policies and reform strategies that more effectively enable older adults to remain in the community.

Design and Methods

We used an interpretive description design methodology (Thorne, 2016) to generate an understanding of participants’ complex experiences of navigating the care continuum, supported by the methods of constructive grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006, 2014). The result is a thematic description of the social process under investigation (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003); this description led to a new understanding (Thorne, 2020) of the limits of community services and the health care system, and the impact of these limitations on lower-care older adults and their family members.

Epistemological and Theoretical Perspectives

Both interpretive description and constructivist grounded theory acknowledge a subjective epistemology whereby researchers are not separate from their work (Charmaz, 2006; Thorne, 2016). In the case of this project, we brought expertise in family studies, nursing, education, and sociology. We acknowledge that these areas of work and study place a high value on the family system as a focal point of care (Bowen, 1978; Feinberg, 2014) and guided the study design (e.g., including family members as study participants). As well, we were guided by an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988) in organizing our thinking about the needs of residents and their family members while living in the community setting; ecological models draw attention to internal and external factors influencing an individual’s well-being. McLeroy’s ecological model (1988) provided a framework for data analysis. According to this model, we considered factors at intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy levels.

Methodology and Methods

Interpretive description is a qualitative methodology that aims to provide a description of themes found in the data, the relationships in and between themes in order to explain the variation in the studied phenomenon, and to produce findings that can guide future practice and planning (Thorne, 2016; Thorne, Kirkham, & O’Flynn-Magee, 2004). Accordingly, we set out to describe the patterns and themes in the data to make an interpretive claim (Thorne et al., 2004) to inform health system planning rather than to develop an abstract theory. The interpretive description draws on various qualitative methods suited to the research question and context, and for this study, constructivist grounded theory methods were appropriate to support a rigorous analytical process (Charmaz, 2006; Rieger, 2019). These methods included data collection methods such as interviews with individual participants and writing supplementary field notes to record nonverbal communication. Data analysis methods included initial and focused coding methods and the constant comparison of data (i.e., comparing data with data, data with code, code with code, and code with category) to develop concepts and their relationships (Charmaz, 2006; Rieger, 2019).

Recruitment

In this study, we sought the perspectives of resident informants who qualified as lower-care residents as defined by their Resident Assessment Instrument—Minimum Data Set scores (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2012) upon nursing home admission (Table 1). Also, where possible, family member perspectives of these residents were sought to provide fulsome narratives of the experience.

Table 1.

Participant Inclusion Criteria

| Who are “lower-care” residents and their family members? |

| “Lower-care” residents are individuals who perform well in physical and cognitive tests, who are continent and have few to no responsive behaviors. The following study inclusion criteria were developed in conjunction with knowledge experts from the local health authority: |

| Resident participants must (a) currently reside at a local nursing home, (b) score 1 or less on the InterRAI MDS 2.0 Activities of Daily Living Hierarchy Scale, (c) score 2 or less on the Cognitive Performance Scale, (d) have no unmanaged bowel concerns, (e) have mild or no unmanaged bladder concerns, and (f) have mild or no responsive behaviors. |

| Family member participants must be a family member of a resident who qualifies for inclusion in the study. “Family member” is used as a broad term and may include anyone that a resident considers to be family (e.g., a close friend or companion). |

Staff members of seven nursing homes recruited participants through convenience sampling (i.e., any resident identified as eligible) and then theoretical sampling was used in an attempt to gather data to refine the analysis and to check for experiences not found through convenience sampling (e.g., residents were recruited to represent specific age groups, sex groups, and groups who had lived in various facilities prior to a nursing home). These sites were located across six community areas within the city of Winnipeg, MB, Canada and under the auspices of the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. Eligible residents were identified by directors of nursing homes who approached all eligible residents to introduce the study and ask if they would be interested in speaking with a researcher to learn more about the research. Those residents who agreed to meet the researchers were met in their nursing home and were provided with further information. All participants signed an informed consent form before data were collected. As a part of the consent process, residents were invited to identify a family member knowledgeable about their needs when they lived in the community. If consent to contact a family member was provided, nursing home staff invited the family member to participate in the study. Family members signed informed consent forms and were interviewed in a private space in the nursing home or by telephone. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the University of Manitoba, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, and individual nursing homes.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants took part in face-to-face, semistructured interviews. The interview guide (Table 2) was developed based on the existing literature and team member expertise to draw out the reasons residents moved into nursing homes, the challenges residents experienced living in the community, and their interactions with community services and the health care system. Interviews were conducted and audio recorded by two authors (H. J. Campbell-Enns and M. Campbell) and field notes were written after each interview. Interviews were transcribed and uploaded to ATLAS.ti software to assist in organizing the data.

Table 2.

Interview Guides

| Resident interview guide | Family member interview guide |

|---|---|

| Where were you living before you came to live in a nursing home? • Who were you living with? • Who were the people you saw the most or talked to the most? • What were the challenges in living in the previous home? |

Where was (the resident) living before she/he came to live in a nursing home? • Who were she/he living with? • Who were the people she/he saw the most or talked to the most? • What were the challenges in living in the previous home? |

| What were the main reasons that you moved to a nursing home? • Probe for physical, emotional, and financial reasons. • Were there rules that made it difficult to live somewhere else or made it necessary to move? |

What were the main reasons (the resident) moved to a nursing home? • Probe for physical, emotional, and financial reasons. • Were there rules that made it difficult to live somewhere else or made it necessary to move? |

| What did you try to help you stay in the previous home? • Probe for services (home care, meals, cleaning), changes to home environment (grab bars, ramps, etc.), and routine care of any kind. • Did you have visitors? • Did you get out into the community (friends, church/synagogue/mosque, day programs)? |

What was tried to help (the resident) stay in the previous home? • Probe for services (home care, meals, cleaning), changes to home environment (grab bars, ramps, etc.), routine care of any kind. • Did (the resident) have visitors? • Did (the resident) get out into the community (friends, church/synagogue/mosque, day programs)? |

| While you were still at your house/apartment what was that like for you? OR What was it like for you to be in hospital and not sure if you were going to return home? | During the time that (the resident) was still at her/his previous home, what was that time like for you as a family member? |

| What would you have needed for you to stay living in your home longer? | What do you think (the resident) would have needed to stay living in the community longer (e.g., home, assisted living)? |

| How did you come to live at a nursing home? • Who was involved in the decision to move there? • How were they involved? |

How did (the resident) come to live at a nursing home? • Who was involved in the decision to move there? • How were they involved? |

| What did you know about the options for places to live? • How did you learn about these options? • Did you consider other housing arrangements or options? |

What did you know about the options for places to live for (the resident)? • How did you learn about these options? • Had you heard of Assisted Living? • Was any other housing arrangement considered? |

| Is there anything else that occurred to you that you would like to share? | Is there anything else that occurred to you that you would like to share? |

Data were analyzed by reading and rereading transcripts, coding fragments of data sentence by sentence, sorting and organizing the data until patterns were identified. The following steps were taken in the process: (a) initial coding was conducted separately by two coders and then codes were discussed with team members; (b) codes were focused further and, using the focused codes, coding was conducted separately by two coders; (c) using the ecological model, factors were identified which corresponded with each component of the model; (d) data were sorted and organized by factors related to barriers and facilitators to living in the community and barriers and facilitators regarding interactions with the health system (Supplementary Figure 1); (e) patterns were identified which represented the common experiences of lower-care residents and their family members; and (f) relationships between patterns were identified which resulted in themes to describe the main problem held for participants in reference to their experiences leading to nursing home admissions.

All authors contributed to this process, and the resulting themes were discussed with two health care managers and three policymakers to evaluate the credibility, resonance, originality, and usefulness of the data collection and analysis (Charmaz, 2006). These health care managers and policymakers had detailed understandings of the continuing care processes and policies affecting residents and family members but did not have specialized knowledge of the individual participants. These discussions occurred at two separate meetings and health care managers and policymakers offered feedback about the credibility, resonance, originality, and usefulness of the findings. This feedback was not incorporated into the findings but assisted us in determining if we needed to continue theoretical sampling. Accordingly, data collection was stopped when associations between themes were examined sufficiently using multiple perspectives.

Results

Participants

The sample included 26 participants. These participants were 13 lower-care residents living in nursing homes and 13 family members of these residents. The family members represent the experiences of 10 lower-care residents; that is, two family members attended and contributed to the family interviews on three separate occasions. Furthermore, eight dyads consisting of a resident and their family member(s) are represented in this study while five residents participated without family member involvement (two resident family members did not respond to requests to participate, two residents chose not to involve their family members, and one resident did not have a family) and two residents informed nursing home staff they did not wish to be interviewed but asked the staff to contact their family member to invite the family member to participate instead.

The average interview length was 46 min (the average resident interview was 40 min and the average family interview was 57 min). Resident participants are described in Table 3 with an average age of 81.6 years (range: 61–94 years). Prior to moving into nursing homes, 10 residents were living independently in houses or apartments, 2 residents were living in a housing option that provided health services (e.g., assisted living facility), and 1 resident had been staying in an emergency shelter due to homelessness. Residents had lived in nursing homes an average of 594 days at the time of recruitment (range: 56–2,508 days). Family members included 10 children, 1 sibling, and 2 nephews/nieces of lower-care residents (9 female and 4 male family members).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Resident Participants (n = 13)

| Characteristic | Count |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 60–69 | 1 |

| 70–79 | 5 |

| 80–89 | 2 |

| 90–99 | 5 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 5 |

| Male | 8 |

| ADL scorea | |

| 0 (no assistance) | 7 |

| 1 (some oversight or cueing needed) | 6 |

| CPS scoreb | |

| 0 (cognitively intact) | 6 |

| 1 (borderline intact) | 5 |

| 2 (mild impairment) | 2 |

| Previous residence | |

| Independent housing | 10 |

| Assisted living facility | 2 |

| Emergency shelter | 1 |

aActivities of Daily Living (ADL) score: Possible scores range from 0 to 6 with higher scores indicating more impairment.

bCognitive Performance Scale (CPS) score: Possible scores range from 0 to 6 with higher scores indicating more impairment.

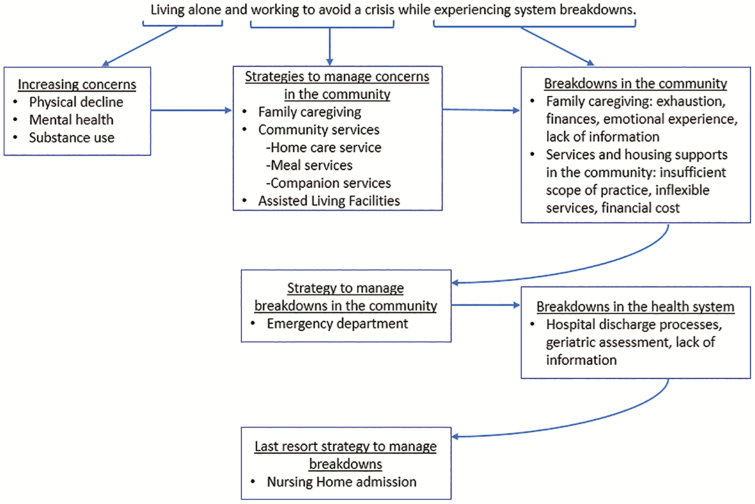

The Main Problem Experienced

The main problem experienced by participants was lower-care residents were living alone with increasing physical and emotional concerns, while both residents and family members were working to avoid safety crises (Figure 1). This was a common problem among all participants. As a result, residents and their family members implemented multiple strategies to manage their rising concerns including intense family caregiving and using multiple community-based health and social services. Each strategy had limitations and broke down over time, often resulting in family members bringing residents into emergency departments. Further breakdowns in the system were experienced at emergency departments and hospitals upon discharge, because residents discharged to the community were unable to remain in the community for long. This experience brought about the final strategy used by family members to manage the breakdowns in the system, that is, nursing home admission for the residents. This was a strategy of last resort for families; nursing home admissions were not desired, but family members saw no other safe care options for the residents. A more detailed description of how participants attempted to address this problem follows, and because residents were unable to recall detailed experiences related to crises and hospitalizations, we predominantly draw on the narratives of family members to illustrate those experiences.

Figure 1.

The main problem experienced by lower-care residents and their family members in the community.

Living Alone With Physical and/or Mental Health and Substance Use Concerns

All residents lived alone before nursing home admission with the exception of one resident who lived with a spouse who was unable to provide practical or emotional support. As residents remained in the community with physical, mental health and substance use concerns, family members felt that safety crises were imminent. Family and friends therefore provided increasingly intense and diverse practical, social, and emotional support to residents. Even so, residents were isolated for many hours each day and night. As a result, living alone was described as a critical factor contributing to nursing home admission; residents and family members described how living alone added complexity to other challenges residents experienced.

Declines in Physical Health

All lower-care residents experienced declines in their physical health while living in the community. Some residents experienced slow physical declines in one or more areas (e.g., mobility, vision, and hearing), whereas others experienced rapid physical declines requiring immediate attention (e.g., injury due to a fall). One family member described the speed of her father’s physical health decline after a car accident, saying that, “His mobility and everything just sort of, literally—it was bad before, now it just went downhill real fast.” In this case, family members struggled to anticipate residents’ day-to-day needs, especially when physical health deteriorated rapidly.

As well, many residents experienced multiple declines in physical health, resulting in relentless worry for both residents and family members, leading to more intense monitoring strategies. One family member described the concern and fear for her father, saying:

It was just a continual downward turn … knowing he was struggling in the home environment … he had really declined and so we were very concerned, you know, seeing him having trouble going to the bathroom, like just major issues were happening. Confusion at times. It was scary.

Although not living in the same neighborhood as her father, she monitored her father through multiple telephone calls and visits each day, interrupting her paid work to do so. Additionally, rapid physical declines were particularly frightening for family members because key community resources had not yet been accessed (e.g., home care services). To add to the stress and confusion, family members were unsure if these declines were temporary or permanent and thus were uncertain if short- or longer-term community resources were needed.

Mental Health

Concerns about depression and anxiety were described by residents and their family members. One resident’s son attributed his mother’s decline to her growing mental health challenges, saying, “[she became] manic, very manic, combative. Like, I think the underlying mental health issues were the primary source of everything [her nursing home admission].” In this case, from the son’s point of view, mental health challenges, combined with living alone, led to his mother’s poor nutrition and overuse of medications, followed by hospital admissions and readmissions, and her eventual nursing home admission.

Some participants experienced severe bouts of depression and anxiety while living alone in the community. Three residents described having persistent suicidal thoughts while living alone, and family members reported this time to be concerning and stressful. One resident’s daughter described bringing her father to the emergency department because he was depressed, and that she was concerned for his safety given his mood. She said, “they were evaluating my dad … and he kept saying that something’s got to be done because ‘I can’t do this anymore, I’m going to kill myself.’” He was admitted to the hospital but, when his mood improved, he was discharged back to the community to live alone with no additional resources. This resident’s health eventually declined to the point that he was admitted to a nursing home.

Residents explained that being alone, especially at night, exacerbated their depression and anxiety. For example, residents were fearful of potential intruders, falling when getting in or out of bed, or becoming very ill or dying when alone during the night. One resident stated, “I don’t sleep at night, because I worry I might not wake up … you know, it’s a worry.” Another resident explained how her anxiety interfered with life and the impact this had on her children. She said:

I got anxiety attacks, depression attacks, and panic—oh, it was really a miserable sort of thing. And my daughters were taking turns sleeping at my place so that I wouldn’t do anything to harm myself, or … you know. Yes, it was a very difficult time.

This resident was admitted into a nursing home after family members became exhausted from working to support their mother in the community.

Substance Use

Alcohol use by residents was problematic and exacerbated by other challenges such as failure to take prescribed medications, poor nutrition, and increased injuries. It also led to cases of alcohol-related dementia among resident participants. One family member discussed a resident’s substance use, saying:

I noticed he’d been drinking alcohol. My father always been a drinker, but this was something else again. It got to the point, you know, I ended up moving in with him for lack of not knowing what else to do. We’re still trying to arrange home care … I would define my father as an alcoholic. It was never just one drink. He never knew when to stop.

In cases such as these, family members were unsure of how best to support residents or how to access help so residents might live longer in the community.

Strategies Used to Avoid a Crisis and Limitations Experienced

While residents lived alone with growing concerns and challenging behaviors, family members worked diligently to avoid safety crises for the residents; yet, they expressed tension with wanting residents to remain in the community while observing mounting safety concerns. This work to avoid crises involved using multiple strategies to manage increasing concerns, including family caregiving, community services, and assisted living facilities.

Family Caregiving

Family members provided residents with intense and ongoing support in the hope residents could remain in the community. For many families, this strategy required daily face-to-face contact with residents to provide needed social interaction combined with essential care (e.g., monitoring nutrition intake and medication use, assisting with vision and hearing devices). When families could not provide daily visits, they supported residents by connecting daily through telephone calls (e.g., in the morning to check if the resident was well and in the evening as a social visit and to provide emotional support). Other activities occurred weekly (e.g., helping with grocery shopping, cooking meals, house cleaning, yard maintenance, and bathing). Irrespective of the frequency, families reported providing intense physical, emotional, and social care for community-dwelling residents.

Family care was often limited by geographical distance, family member time constraints, and the specialized skills needed to provide some types of physical or emotional support. Financial matters were also an important consideration, and some family members reduced their paid work to provide informal care. Family members explained how their exhaustion, coupled with these practical matters, limited their ability to provide ongoing and intensive care. One resident’s sister stated, “It was getting to be too much for me, trying to do it all.” The daughter of another resident explained the strain of caring on the family, stating:

I couldn’t live with him not having food, not having care. Like, it was a tremendous toll, yeah, tremendous. I know it was a toll on my brother, a toll on my husband, a toll on my dad’s siblings, my mom’s siblings. Everybody just felt helpless.

Community Services

Family members sought out community-based services to help support residents, including home care, meal delivery, and companion support services to fill the gap between informal and home care support. They also investigated congregate community-based housing with basic health care service options (e.g., assisted living facilities).

These services were perceived by participants to be of limited use due to their narrow scope, inflexible schedule, and, in some instances, extensive cost. First, both residents and families described home care services as limited and stated needing more visits than home care would provide and greater flexibility in when these visits occurred (e.g., needed visits at night). Participants also noted that home care did not provide consistent gender or culturally sensitive care (e.g., for intimate care services) and felt some staff lacked the ability to monitor medication adherence and to identify early signs of common concerns (e.g., bladder infections). One daughter explained the need for improved home care, saying:

She [mother] was forgetting to take her pills and—because home care doesn’t stay and wait to see if they take them—they’d hand them to her and she’d … some would fall on the floor and—oh gosh—it was just very scary.

Another family member described the limitations of home care by saying, “Having home care come in … she just needed more care than what they offered.”

Second, participants reported that meal delivery services lacked personalized meals (e.g., meals acceptable to the resident) and did not provide follow-up care (e.g., to check if the food was eaten, or if left-over food was stored safely). Family members reported that these meals were not eaten by residents, or residents set the food aside and consumed the spoiled food later. A resident’s son explained that his father was hospitalized due to food poisoning, stating that:

The meals, they were delivered. It was the lunch and dinner. And near the end he was just leaving them out, and he was stacking them up in the fridge. And he was eating stuff that was—had gone bad. So that’s why he was sort of initially admitted to the hospital, he was ill.

Third, while family members slept at the resident’s home to provide companionship and watch for safety concerns, this was not a sustainable solution. As a result, families paid for companion services to accompany residents at night, particularly when residents were depressed, anxious, or experiencing other safety concerns (e.g., fear of falling). Although this service was costly for families, it was utilized when family members were exhausted and as a break from intense informal caregiving. One family member explained this, saying:

We hired the companion to come in three nights a week … so we could have a weekend off. And my one sister paid for every Wednesday and then we all chipped in and got the other two nights a week so that we could—I mean I wouldn’t have lasted if we didn’t do that. There’s no way I could have done it.

Assisted Living Facilities

Two residents lived in congregate housing with health care services, and several other families investigated this option as an alternative to nursing home admission. This option was thought to provide valuable recreation opportunities and nutritional meals for residents, but only if the residents were well enough to care for themselves. Residents who could not attend meals and recreational events independently struggled to have their social and emotional needs met in assisted living facilities.

As a key limitation, families stated that assisted living residents were alone throughout the day and always alone at night. One daughter explored the possibility of her father moving to an assisted living facility, but she said, “I’m back to the same scenario where—in theory—he [resident] is alone in that room.” A family member of another resident explained how they had considered an assisted living facility but felt the facility could not prevent emergency department transfers from occurring during the night. She said:

They had a nurse on Monday to Friday during the day to help … very minimal assistance … we didn’t feel good about it because we thought, what happens in the middle of the night? Like, even though they have a call bell and stuff, but what happens in the middle of the night when she’s … are they still going to call 911 and send her to the ER anyway?

Experiencing Breakdowns in the Health System

Because of the previously described challenges, family members felt their only recourse was to transport residents to emergency departments, which were often followed by hospitalizations. However, breakdowns in acute care discharge processes, the timing and quality of geriatric assessments, and a lack of information regarding services and processes often precipitated nursing home admissions for lower-care residents.

Hospital Discharge and Geriatric Assessments

All residents in this study were transported to an emergency department on one or more occasions prior to their nursing home admission, and family members described the frustrating process of transitioning residents back to the community with inadequate supports. This process was particularly problematic because these residents lived alone. Without a discharge process connecting the resident to comprehensive community supports (i.e., home care and mental health team), gains made in the hospital faded quickly when the resident returned to the community. One family member described this process, saying:

They hydrate her so, of course, she feels great in the morning and they send her home. Again. Well, we [see her] two days later, and it wasn’t pretty. I tried to, we tried to, keep her out of the hospital [by sleeping at her home and assisting her]. But we couldn’t.

Soon after discharge, this resident was readmitted to the hospital after declining again at home.

Other families expressed similar stories and described varying degrees of frustration with hospital discharge procedures. One daughter described her intense feelings of frustration and fear when her father was discharged from the hospital. She said:

When they were getting ready to release my father the first time from the hospital—what are my options? … I need a checklist of—these are the people I need to call to help get home care. I need to have some sort of idea of somebody I can call to get my father really assessed … There’s nobody I can turn to; he doesn’t have a personal physician at the time … there’s absolutely nothing. Who do I turn to in the middle of the night if I’m having problems with this man? He’s already done some really wild things to start off with, what happens if this happens again? It’s going to happen again. We told the hospital he wasn’t ready to go. They released him anyway. Nobody offered us home services for him. There was absolutely no follow-up, absolutely none … you know, we’re concerned enough that we think he needs to be hospitalized … and we’re still concerned—why do you think it’s okay to release him without any kind of support behind it?

Once discharged from the hospital, this family member described feelings of helplessness, saying: “He started to deteriorate quickly again … he’s already been discharged once, like what’s the point in going back to the hospital? We’ve done that already.” In the end, the daughter moved in with her father and, while she was at work, the resident started a fire in his apartment. The resident was evacuated by firefighters and, upon his daughter’s insistence, was transported back to the hospital. Without a home to return to in the community, the resident was admitted to a nursing home. While this narrative highlights the chaos and intense feelings resulting from one family’s negative discharge experiences, all participants were frustrated with acute care discharge experiences.

Furthermore, when family members connected to a part of the health system that would assess the resident for community services or for nursing home placement, they found geriatric assessment procedures to be limited. Families wished for residents to be assessed on multiple occasions. A family member described how a single short assessment did not capture her growing concerns about her father living alone, saying, “He presents very well in a short time. But if you stay with him long enough, you can see how he sort of digresses into, you know, the past and [repeats] the same questions.”

Lack of Information

Residents and family members described the lack of information available to make informed decisions, be that about services available in the community, how to access the formal care continuum (i.e., home care, assisted living, and nursing homes), and when to access acute care services. One daughter said:

I don’t understand why there isn’t more information on the internet. I don’t understand, why not? In this day and age … people turn to looking for information. There is really nothing out there. I don’t know how else to explain it … Like you, your loved one is needing help, where do you start? You need a starting point and there doesn’t seem to be someplace where you can go and look.

Specific to the nursing home admission assessment (locally termed the “paneling” process; this is a complex process involving the evaluation of a person’s health, consideration of potential community supports, or, if deemed appropriate, matching of the patient to a nursing home with an available bed), families were unclear of its purpose or how to access it. Most families learned about admission assessment processes from knowledgeable people outside of the health care system. One family member said, “Everything that happened for us became us chasing the system.” Another family member described their experience, saying: “We were always navigating. I was navigating … I had to become very system-smart.” Those who felt most successful at navigating the process were either family members who worked in health care in some capacity, or family members who had “friends of friends” who worked in the health care system. One family member described the work an acquaintance did on her behalf, saying, “She actually did a bit of zigging and zagging to get this [panelling] all going.”

Residents continued to lack information once the nursing home paneling process began. Several family members were told (from acquaintances) that residents needed to restart the paneling process each time residents moved between the community and hospital settings. One family member said, “Mom went in the hospital … so then the panelling process was stopped.” I said, “so now what happens? She [staff] said, ‘you start all over again.’ … so, I had to start all over again.” Another family member said they did not need to restart the paneling process when their mother was admitted into the hospital because, as far as she could tell, the paperwork for paneling was still active. She said, “I think the panelling process itself was a bit confusing … Joe Public doesn’t know, like, is that a document that’s intact for a year? Like is there a time limit to it? There is a bit of confusion around the panelling process.” The uncertainty about the paneling process created feelings of additional unease among families in terms of where the resident should wait for nursing home admission; some families wondered if they should put their finite resources (i.e., time, energy, and money) into keeping the resident out of the hospital until the paneling process was completed, even if it did not feel very safe. Family members felt at a loss due to the lack of information and guidance in this process.

Nursing Home Admission as a Last Resort

Breakdowns in both the community and the health care system gave rise to residents and families seeking nursing home placements, a strategy of last resort to provide safety for residents in increasingly challenging contexts in the community. Nursing home placement was the least desirable option for families, and they expressed mixed emotions about placing residents in nursing homes. Families felt fear that comes with the uncertainty of how residents would react to the placements, and fear of a change in their relationship if residents felt forced to move. Emotions also included guilt and failure associated with not being able to care for residents in the way they had imagined. At the same time, family members felt relief that residents were in a place where their concerns could be better managed, and the residents knew they needed more care than they were able to have in community-based settings. One resident described feelings of not wanting to move to a nursing home, but she knew her family had reached their limit in providing care. She said:

I knew I needed help. I mean, they were doing the best they could for me, but, you know, I needed more of their time and their effort; and just knowing that they were with me, I think, is what I needed. And, that, it was getting to be a habit, cause they had their husbands, they had their lives to live.

Admission to a nursing home was not chosen willingly by residents or family members, but with no other meaningful choice in the community, it was a last resort strategy to provide a safe place for residents who lived alone among rising concerns for their well-being.

Discussion

The main problem experienced by residents and family members in this study was the desire to avoid a crisis while residents lived alone with growing concerns, which led to nursing home admissions. Prior research provides insight into the concerns described by residents and their family members. First, living alone is a known indicator of social isolation which can have negative physical and mental health associations (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). Despite this, there is little evidence of assessing social isolation in older adults. Routine assessment may indicate which individuals would benefit from targeted programs to reduce experiences of isolation (Patel, Wardle, & Parikh, 2019).

Second, physical and functional decline commonly occurs in the course of aging, and, when external supports are not in place, further and rapid declines may be expected (Colón-Emeric, Whitson, Pavon, & Hoenig, 2013). However, not all residents experienced a significant functional decline as a direct result of a medical condition. Instead, participants connected physical declines and the lack of access to community-based services; health declines were exacerbated when participants were unable to access these supports.

Third, mental health challenges are present among older adults with depression and anxiety affecting 5%–15% of older adults living in the community (Bryant, Jackson, & Ames, 2008; Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health, 2006) and more than 40% living in nursing homes (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010). In this study, residents and their family members discussed mental health challenges, including suicidality, while living alone at home. Families attempted to connect residents to mental health supports but did not experience emergency departments and hospitals to be responsive. This may be due to residents concealing their challenges due to mental health stigma, not understanding that these challenges are treatable (Solway, Estes, Goldberg, & Berry, 2010), or an overall lack of awareness within the health care system of mental health issues in older adults (Shastri et al., 2019).

Given the push of many jurisdictions of adopting aging in place strategies (Dupuis-Blanchard et al., 2015), this study provides valuable insight into the unique considerations that may be required for the successful implementation of these strategies. The main concerns noted by participants—isolation, physical and cognitive decline, anxiety and depression, and substance use—are a constellation of concerns which, together, created a sense of risk residents and family members felt was untenable in the community setting. Residents and family members experienced breakdowns in care in a society that strives to enable relatively well older adults to age in place.

Limitations

This study is limited by the cultural composition of participants who were mainly English speakers and were mainly Caucasian; we do not know why or how supports for aging in place may be provided differently across cultural groups. Also, this study looked to residents in nursing homes to explain the needs of persons in the community. This setting was necessary because we were unable to identify persons who met the inclusion criteria in the community.

Implications

Residents and their family members highlighted the limitations of the health services they encountered while living in the community. To address these, we recommend amendments to hospital discharge policies to allow for discharge plans to be negotiated with residents and family members earlier than at the time of discharge (Jack et al., 2009). As well, when older adults are living alone in the community, hospital discharge policies must address information support and the coordination of community-based services. Ideally, these services should be established prior to the individual being discharged, to minimize the substantial burden placed on family caregivers to fill the gap until services start.

Furthermore, in the community setting, health service delivery must be reformed to meet the unmet needs of older adults who are living alone. Services (e.g., home care) must be available on more flexible schedules (Patmore & McNulty, 2005) and staff must receive enhanced training for mental health and substance use support. As well, early and repeated geriatric assessments are required to assess for isolation (Extermann & Hurria, 2007). Residents and family members experienced care as both complex (Plsek & Greenhalgh, 2001) and fragmented (Clarfield, Bergman, & Kane, 2001), yet families expected comprehensive and integrated care processes. As a result, health system reform must strive for an integrated care approach in order to provide coordinated and comprehensive care (Gröne & Garcia-Barbero, 2001).

Conclusions

This study reveals reasons why lower-care residents are admitted to a nursing home, including the breakdowns in community and health care experienced by residents and family members. Residents were challenged by living alone with increasing physical and psychological concerns and, due to difficulties in accessing care in the community, had no other viable options but to be admitted to nursing homes.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through a Health Systems Impact Fellowship, with additional support from Research Manitoba and the Government of Manitoba (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bowen M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant C., Jackson H., & Ames D (2008). The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: Methodological issues and a review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 109(3), 233–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull M. J., Hansen H. E., & Gross C. R (2000). Predictors of elder and family caregiver satisfaction with discharge planning. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 14(3), 76–87. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200004000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J. J. (1992). Aging in place. Generations, 16(2), 5–5. doi: 10.4324/9781315227603-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (2006). National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: The assessment and treatment of depression.Toronto, Canada: Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (CCSMH) https://ccsmh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/NatlGuideline_Depression.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (2010). Depression among seniors in residential care.Toronto, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/ccrs_depression_among_seniors_e.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (2012). RAI-MDS 2.0© Decision-support tools for clinicians and managers. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/outcome_rai-mds_2.0_en.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Clarfield A. M., Bergman H., & Kane R (2001). Fragmentation of care for frail older people—An international problem. Experience from three countries: Israel, Canada, and the United States. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49(12), 1714–1721. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay M. (2001). Rehabilitation in nursing homes. Nursing Older People, 13(4), 23–27; quiz 28. doi: 10.7748/nop2001.06.13.4.23.c2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón-Emeric C. S., Whitson H. E., Pavon J., & Hoenig H (2013). Functional decline in older adults. American Family Physician, 88(6), 388–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupe M., St John P., Chateau D., Strang D., Smele S., Bozat-Emre S.,...Dik N (2012). Profiling the multidimensional needs of new nursing home residents: Evidence to support planning. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(5), 487.e9–487.17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Blanchard S., Gould O. N., Gibbons C., Simard M., Éthier S., & Villalon L (2015). Strategies for aging in place: The experience of language-minority seniors with loss of independence. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 2333393614565187. doi: 10.1177/2333393614565187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extermann M., & Hurria A (2007). Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(14), 1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausset C. B., Kelly A. J., Rogers W. A., & Fisk A. D (2011). Challenges to aging in place: Understanding home maintenance difficulties. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 25(2), 125–141. doi: 10.1080/02763893.2011.571105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L. F. (2014). Moving toward person- and family-centered care. Public Policy & Aging Report, 24(3), 97–101. doi: 10.1093/ppar/pru027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gröne O., & Garcia-Barbero M (2001). Integrated care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1525335/. Accessed December 30, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halasyamani L., Kripalani S., Coleman E., Schnipper J., van Walraven C., Nagamine J.,...Manning D (2006). Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 1(6), 354–360. doi: 10.1002/jhm.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack B. W., Chetty V. K., Anthony D., Greenwald J. L., Sanchez G. M., Johnson A. E.,...Culpepper L (2009). A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150(3), 178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh-Hunt N., Bagguley D., Bash K., Turner V., Turnbull S., Valtorta N., & Caan W (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K. R., Bibeau D., Steckler A., & Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNabney M. K., Wolff J. L., Semanick L. M., Kasper J. D., & Boult C (2007). Care needs of higher-functioning nursing home residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 8(6), 409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallin D. J., Allen M. B., Espinola J. A., Camargo C. A. Jr, & Bohan J. S (2013). Population aging and emergency departments: Visits will not increase, lengths-of-stay and hospitalizations will. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 32(7), 1306–1312. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. S., Wardle K., & Parikh R. J (2019). Loneliness: The present and the future. Age and Ageing, 48(4), 476–477. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patmore C., & McNulty A (2005). Flexible, person-centred home care for older people (p. 4). Toronto, Canada: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York; https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/rworks/aug2005.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek P. E., & Greenhalgh T (2001). The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ, 323(7313), 625–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger K. L. (2019). Discriminating among grounded theory approaches. Nursing Inquiry, 26(1), e12261. doi: 10.1111/nin.12261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryser L., & Halseth G (2011). Informal support networks of low-income senior women living alone: Evidence from Fort St. John, BC. Journal of Women & Aging, 23(3), 185–202. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2011.587734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M., & Barroso J (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 905–923. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastri A., Aimola L., Tooke B., Quirk A., Corrado O., Hood C., & Crawford M. J (2019). Recognition and treatment of depression in older adults admitted to acute hospitals in England. Clinical Medicine (London, England), 19(2), 114–118. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-2-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway E., Estes C. L., Goldberg S., & Berry J (2010). Access barriers to mental health services for older adults from diverse populations: Perspectives of leaders in mental health and aging. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 22(4), 360–378. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2010.507650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2020). Beyond theming: Making qualitative studies matter. Nursing Inquiry, 27(1), e12343. doi: 10.1111/nin.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Kirkham S. R., & O’Flynn-Magee K (2004). The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1177/160940690400300101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.