Abstract

Background:

Chlorhexidine has been widely used in the occupational field as an effective antiseptic and disinfectant, especially in the health-care services. Several cases of allergic reactions to chlorhexidine have been reported, both in the general population and in workers.

Objectives:

To describe a case of occupational chlorhexidine-induced severe anaphylaxis that occurred in the workplace in a health-care worker (HCW) and to update the literature on chlorhexidine as a possible occupational allergen.

Methods:

We report a case of a severe anaphylactic reaction that occurred in the workplace in a 63-year-old man, who had worked as a dentist for over 20 years. We also carried out a systematic review of the literature according to the PRISMA guidelines. No time or language filters were applied. Only occupational case-reports and case-series were included.

Results:

The causative role of chlorhexidine was suspected owing to the presence of chlorhexidine-containing products in the workplace. Positive results on the Basophil Activation Test confirmed the diagnosis of immediate chlorhexidine-induced hypersensitivity reaction and excluded a role of other disinfectants. No other causes of anaphylaxis were suspected. Our systematic literature review identified 14 cases of occupational chlorhexidine-induced allergy among HCWs; in these cases, the clinical presentation was mild and the symptoms resolved. No cases of systemic reactions in the workplace were reported.

Conclusions:

This is the first report of chlorhexidine-induced severe anaphylaxis occurring in the workplace. This case report underlines the importance of investigating and being aware of individual and environmental risk factors in the occupational field, which can cause, albeit infrequently, severe reactions with serious consequences.

Key words: Chlorhexidine, occupational anaphylaxis, health-care worker, disinfectant, sensitizers

Abstract

«Anafilassi da clorexidina sul luogo di lavoro in un operatore sanitario: case report e revisione della letteratura».

Introduzione:

La clorexidina è ampiamente utilizzata in ambito occupazionale come efficace prodotto antisettico e disinfettante, specialmente nei servizi sanitari. Sono noti numerosi casi di reazioni allergiche a clorexidina sia nella popolazione generale sia nei lavoratori.

Obiettivi:

Descrivere un caso di anafilassi occupazionale da clorexidina avvenuta sul posto di lavoro in un operatore sanitario, e aggiornare la letteratura sulla clorexidina come possibile allergene professionale.

Metodi:

Riportiamo un caso di reazione anafilattica grave avvenuta sul posto di lavoro in un uomo di 63 anni, odontoiatra da oltre vent’anni. Abbiamo inoltre effettuato una revisione sistematica della letteratura secondo le linee guida PRISMA, senza filtri temporali o linguistici, includendo solo case report e case-series di tipo occupazionale.

Risultati:

Il ruolo causale della clorexidina è stato sospettato per via della presenza di prodotti contenenti clorexidina sul posto di lavoro. I risultati postivi del Test di Attivazione dei Basofili hanno confermato la diagnosi di ipersensibilità immediata a clorexidina, e hanno escluso il ruolo di altri disinfettanti. Nessun’altra causa di anafilassi è stata sospettata. La nostra revisione sistematica della letteratura ha identificato 14 casi di allergia occupazionale a clorexidina in operatori sanitari; in tali casi le manifestazioni cliniche erano lievi e con risoluzione dei sintomi. Non è stato riportato nessun caso di reazione sistemica sul posto di lavoro.

Conclusioni:

Questo è il primo caso di reazione anafilattica grave da clorexidina avvenuta sul posto di lavoro. Questo caso clinico sottolinea l’importanza di indagare e conoscere i fattori di rischio individuali e ambientali in ambito occupazionale, potenziali cause, anche se non frequentemente, di reazioni severe con gravi conseguenze.

Introduction

Since its introduction in 1954, chlorhexidine, a synthetic bis-biguanide, has been widely used in the occupational field as an effective antiseptic and disinfectant, especially in the health-care services (e.g., peri-operative medicine and anesthesiology), for skin preparation, coating central venous lines and urinary catheters, and so on. Furthermore, chlorhexidine is one of the most commonly prescribed antimicrobial agents in the dental field (28), and can be found in a variety of therapeutics, including over-the-counter products (26). An increasing number of cases of delayed (type – IV, mediated by the cells of the immune system) and immediate (type I, IgE-mediated) hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine, including anaphylaxis, have been reported in the general population, particularly among surgical patients (e.g., in urology and gynecology). Chlorhexidine has been recognized as a cause of type – IV reactions such as allergic contact dermatitis, urticaria, photodermatitis and drug-related skin eruptions (5, 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, 20). Chlorhexidine IgE-mediated reactions can be very severe, with facial flushing, swelling and paresthesia, generalized urticaria or itching, difficulty in breathing and reduced blood pressure, and can require aggressive treatment with adrenaline. Rare anaphylactic reactions to chlorhexidine, first reported in 1984, are potentially life-threatening (20). The phenomenon has been more frequently described in the occupational field, especially among Health-care Workers (HCWs), and may impair their occupational activity (1, 8, 14, 16).

Here, we report a case of occupational chlorhexidine-induced severe anaphylaxis that occurred in the workplace in a HCW. We also update the literature on chlorhexidine as a possible occupational allergen.

Methods

This case is reported in accordance with the CARE checklist (4).

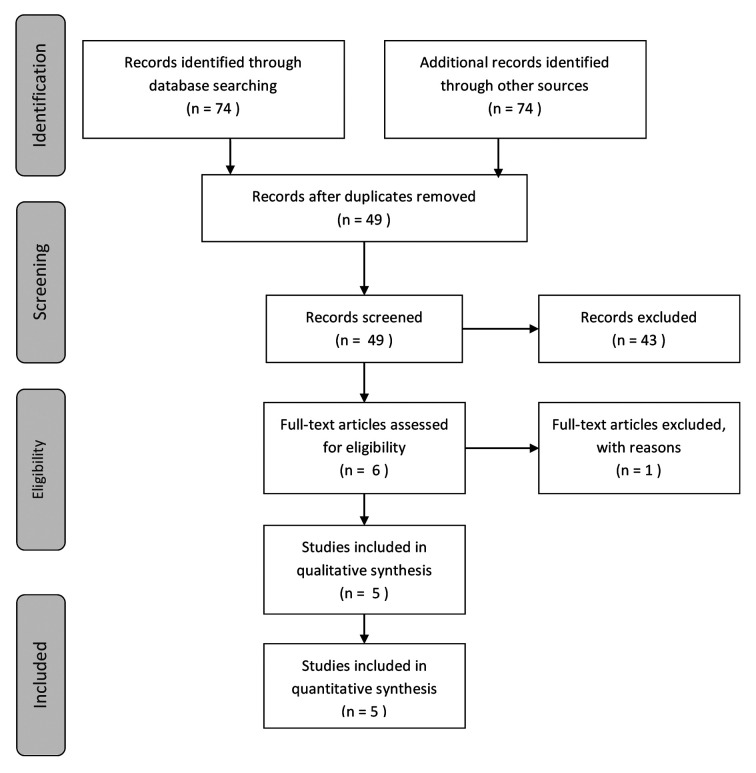

Moreover, our systematic review of the literature was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (11); we used a string of appropriate keywords, including “allergy”, “chlorhexidine” and “workers”, connected with ad hoc Boolean operators. Medical subject headings (MeSH) and wild-card options were utilized when appropriate. No time or language filters were applied. Only occupational case-reports and case-series were included. One study was excluded. All references cited in the studies included were searched in an iterative way, until no new study could be found. Target journals were extensively hand-searched. Further details of the search strategy used in the systematic review are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Details of search strategy used in the systematic review

| Search strategy item | Details |

| Keywords | Chlorhexidine AND (anaphylaxis OR allergy OR allergic OR hypersensitization) AND (worker OR work-related OR workplace OR occupational) |

| Databases/thesauri searched | PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar |

| Inclusion criteria | P: workers I: occupational exposure to chlorhexidine Study design: case-report, case-series |

| Exclusion criteria | Studies not dealing with occupational population Study design: cross-sectional studies, reviews (including systematic reviews and meta-analyses), Letters to editor, commentaries, expert opinions |

| Time filter | None applied |

| Language filter | None applied |

| Target journals | Allergo journal international; Allergologia et immunopathologia; Allergy; Annals of allergy, asthma and immunology; Australasian Journal of Dermatology, Chemical immunology and allergy; Clinical and experimental allergy; Clinical and experimental immunology; Contact dermatitis; Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology; Dermatitis; European annals of allergy and clinical immunology; International archives of allergy and immunology; International Review of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; Journal of investigational allergology and clinical immunology; Journal of occupational health; Occupational medicine; Skinmed; The journal of allergy and clinical immunology |

P: Participants

I: Interventions

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

For each study included, the following data were extracted: surname of first author, year of publication, country, age, gender, occupational activity of the patient(s), allergic history, type of exposure, clinical pictures, diagnosis, management/treatment and health outcome of the case.

Results

This case of anaphylaxis involved a 63-year-old non-atopic man who had been employed as a dentist for over 20 years in outpatient dental clinics.

In August 2015, while at work, he experienced a systemic reaction characterized by the rapid onset of acute and diffuse urticaria and recurrent loss of consciousness; he was immediately treated with steroids and epinephrine in the workplace. At the Emergency Department, anaphylactic shock was suspected. More than one year earlier, he had referred two episodes of transitory loss of consciousness at work, without other typical characteristics of anaphylaxis; these episodes were attributed to laryngeal hyper-reactivity. Skin Prick Tests (SPTs) for common inhalant and latex allergens were negative.

Three months later the man was evaluated at the Allergy Unit of the San Martino Teaching Hospital in Genoa. Determination of Immuno-CAP (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for chlorhexidine-specific IgE (sIgE) was prescribed. The result was 0.04 kU/L, together with a value of 46.7 kU/L of total IgE. A Basophil Activation Test (BAT) was also performed for all the products used in the workplace before the onset of anaphylaxis: indeed, the man’s working environment had previously been sanitized by means of an aerosol spray of various products containing phenol, ortho-phthalaldehyde and chlorhexidine. As the man had not worn any facial protection, he had been exposed via inhalation. BAT evaluates the expression of the activation marker CD63 on the membrane of basophils. The test is considered positive when CD63 on basophils incubated with the suspected agent is higher than 5.0% and when this expression is twice as high as that obtained with the wash buffer (stimulation index SI >2.0) (7). A clearly positive CD63 expression (14.5%) and SI=6.0 were recorded for chlorhexidine. This result was confirmed by testing a mouthwash containing chlorhexidine (CD63=9.6% and SI=4.0). All the other disinfectants tested proved negative (CD63 <5.0% and SI<2.0). The same disinfectant containing chlorhexidine proved negative in other sera, which were used as a negative control, as per usual laboratory procedures. The product that triggered the immediate systemic hypersensitivity reaction was a 2.0% solution chlorhexidine digluconate, mixed with other components (tetradecyltrimethylammonium bromide, dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide, isopropanol).

The systematic literature review retrieved and included 14 cases of chlorhexidine-induced allergy in HCWs. The characteristics of these cases are outlined in table 2. Exposure was mainly due to hand-washing with products containing chlorhexidine. In most cases, the clinical presentation was characterized by itching, redness and urticaria. Two cases of occupational asthma were also reported. Symptoms were generally mild and not persistent. The only anaphylactic reaction occurred in a nurse. In this case, some mild symptoms (i.e., urticaria and mild dyspnea) had occurred outside the workplace, during tooth brushing with chlorhexidine-containing toothpaste, and the anaphylactic reaction arose subsequently, during a specific inhalation challenge test with chlorhexidine (31).

Table 2.

General characteristics of 14 cases of occupational allergic reactions to chlorhexidine

| Reference | Country | Age | Gender | Occupational activity | Allergic history | Type of exposure | Clinical picture | Diagnosis | Management/Treatment | Health outcome |

| Nagendran et al., 2009 | UK | 31 | Female | Oncology-nurse | No | Chlorhexidine hand-washes | Itching and redness of wrists and forearms, urticaria | Clinical, SPT sIgE | 3 months after switching to non-chlorhexidine hand washes | Resolution of symptoms |

| Nagendran et al., 2009 | UK | 51 | Female | Theatre-nurse | No | Chlorhexidine hand-washes | Itching and urticarial rash | Clinical sIgE | Switching to non-chlorhexidine hand washes | Resolution of symptoms |

| Nagendran et al., 2009 | UK | 35 | Female | Endoscopy nurse | No | Powdered latex gloves + chlorhexidine hand-washes | Itching, redness of hands, rhinitis | Clinical, SPT sIgE | Avoiding wearing powdered latex gloves | Persistence of symptoms |

| Nagendran et al., 2009 | UK | 43 | Female | Domestic nurse | No | Chlorhexidine hand-washes | Hand dermatitis with secondary infection, urticaria of forearms | Clinical, SPT sIgE | Flucloxacillin and Dermovate, avoiding wearing powdered latex gloves | Resolution of symptoms |

| Toholka and Nixon, 2013 | Australia | 21 | Female | Graduate nurse | No | Chlorhexidine-based skin cleansers | Facial erythematous, pruritic eruption with localized edema | Clinical Patch tests | Oral corticosteroids, avoiding chlorhexidine-based skin cleansers | Resolution of symptoms |

| Toholka and Nixon, 2013 | Australia | 20 | Female | Nursing student | No | Chlorhexidine-based hand rub | Papular eruption | Clinical Patch tests | Avoiding chlorhexidine-based hand rub and other products | Resolution of symptoms |

| Toholka and Nixon, 2013 | Australia | 21 | Female | Nursing student | Yes (atopic eczema) | Chlorhexidine-based skin cleansers | Recurrent episodes of dermatitis | Clinical Patch tests | Avoiding chlorhexidine-based other products | Resolution of symptoms |

| Toholka and Nixon, 2013 | Australia | 28 | Female | Intensive care nurse | No | Chlorhexidine-based skin cleansers | Recurrent episodes of dermatitis | Clinical Patch tests | Avoiding chlorhexidine-based products | Resolution of symptoms |

| Waclawaski et al., 1989 | UK | 54 | Female | Nursing auxiliary | No | Chlorhexidine aerosols | Asthma | Clinical Spirometry | Not available | Not available |

| Waclawaski et al., 1989 | UK | 43 | Female | Midwife | No | Chlorhexidine aerosols | Asthma | Clinical Spirometry | Not available | Not available |

| Wittczak et al., 2013 | Poland | 46 | Female | Nurse in the internal medicine ward | No | Use of chlorhexidine as disinfectant in different medical procedures | Non-productive cough and dyspnea with wheezing | Clinical SPT sIgE Specific challenge tests | Not available | Not available |

| Wittczak et al., 2013 | Poland | 34 | Female | Nurse in the pediatric nephrology ward | No | Use of chlorhexidine as disinfectant in different medical procedures | Recurrent non-productive cough, dyspnea with wheezing, rhinorrhea and paroxysmal sneezing | Clinical, SPT sIgE Specific challenge tests | Not available | Not available |

| Wittczak et al., 2013 | Poland | 45 | Female | Nurse in the cardiology ward | No | Tooth brushing with chlorhexidine-containing toothpaste | Dyspnea and urticaria | Clinical, SPT SIgE Specific challenge tests (stopped due to anaphylactic reaction) | Not available | Not available |

| Vu et al., 2017 | Australia | 49 | Female | Endoscopy technician | Yes (contact dermatitis, allergy to aspirin) | Chlorhexidine-based hand rub | Urticaria on the hands and arms, chest tightness, dyspnea | Clinical, SPT, Patch tests | Avoiding chlorhexidine-based products | Resolution of symptoms |

sIgE: Specific IgE; SPT: Skin Prick Test

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of occupational chlorhexidine-induced severe anaphylaxis occurring in the workplace.

Our results show that chlorhexidine, a well-known allergen in non-professional settings (19), should be considered a possible occupational allergen able to cause, albeit infrequently, severe reactions with serious consequences (13, 24).

Allergic sensitization to antiseptics/disinfectants containing chlorhexidine could be frequent and is likely to increase given the widespread utilization of these products in health-care settings, and hence the chronic exposure of workers. In our case, the sanitation procedures carried out in the dental clinics included daily cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces with aerosol products containing antiseptic/disinfectant.

The first two cases of asthma, which were confirmed by means of occupational challenge, were reported in 1989 by Waclawaski et al. (30), and revealed the risk of using chlorhexidine aerosol in health-care settings.

In 2003 a Danish cross-sectional study failed to ascertain any laboratory-confirmed allergy to chlorhexidine among 104 HCWs recruited (physicians, nurses, auxiliary staff); the authors concluded that IgE sensitization was a very rare event in the occupational field, despite considerable exposure (6).

In 2009, Nagendran et al. identified the first confirmed occupational IgE-mediated chlorhexidine allergy among HCW with itching, urticarial rash and rhinitis, confirming the diagnosis in 4 (7.7%) of the 52 patients investigated (14).

The three cases described in 2013 by Wittczak et al. demonstrated that occupational allergy to chlorhexidine could be characterized by several clinical forms, such as cutaneous, respiratory or even systemic manifestations (31).

Occupational cases of cutaneous symptoms had already been described elsewhere (23), but only in 2013 did Toholka et al. report a case of contact allergy sensitization, confirmed by Patch Tests, in 10 (2%) out of 541 HCWs, a higher rate than previously documented (27).

In 2016, Ibler et al. studied a sample of 120 HCWs by performing allergy tests; chlorhexidine-mediated delayed-type and immediate-type hypersensitivity was found in 1 participant (<1%). However, they concluded that, owing to widespread exposure, chlorhexidine should be included in occupational allergy investigations in HCWs (8).

Recently, Vu et al. described a case of immediate hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine in an endoscopy technician, with a history of urticaria and respiratory symptoms, which was confirmed by means of SPTs (29).

The literature reports very few cases of allergic reactions in professional categories other than HCWs, such as agricultural workers (9).

Diagnosis is usually based on the subject’s clinical history, SPTs and serum-specific IgE in cases of clinical immediate-type manifestations (14). However, in cases of severe reaction, skin tests are deemed unethical and BAT may be carried out: this is another reliable in vitro diagnostic tool, though not usually available (2, 3).

In our case report, diagnostic procedures did not include SPTs for antiseptics because of the severity of the reaction and the fact that sIgE, measured three months after the reaction, showed low values. By contrast, positive BAT results confirmed the suspicion of an immediate chlorhexidine-induced hypersensitivity reaction and excluded a role of other disinfectants, which proved negative. The contradictory results yielded by BAT and sIgE for chlorhexidine may have been due to the different sensitivity of the two tests; indeed, basophil activation is triggered by the cross-linking of membrane IgE even when total and sIgE are low, while sIgE are detected in serum with a great dilution factor.

Conclusions

Hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine appears to be a rare phenomenon, though it may be overlooked and hence under-reported. In view of the widespread use of chlorhexidine to control infections in health-care settings, and the consequent high exposure of HCWs, the present case report underlines the importance of better investigating individual and environmental risk factors that may lead to chlorhexidine sensitization among employees.

As anaphylaxis and other severe systemic allergic reactions have serious consequences for both the health and productivity of workers, this issue needs to be more thoroughly investigated in order to acquire further knowledge for use in planning proper prevention strategies.

Appropriate health surveillance programs in these occupational settings should consider the implications of exposure to chlorhexidine in order to prevent life-threatening events. In this regard, it is noteworthy that workers who are sensitized to specific allergens in the workplace may also develop anaphylaxis outside (22, 31), creating further difficulties for the proper management of this severe clinical picture. Adequate information should be made available to the medical community, which generally has scant knowledge of the side effects of chlorhexidine and its potential severe adverse reactions (25).

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported by the authors

Acknowledgment:

We thank Dr. Bernard Patrick for correcting the English manuscript.

References

- 1.Chaari N, Sakly A, Amri C, et al. Occupational allergy in healthcare workers. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2010;4:65–74. doi: 10.2174/187221310789895630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebo DG, Bridts CH, Stevens WJ. Anaphylaxis to an urethral lubricant: chlorhexidine as the “hidden” allergen. Acta Clin Belg. 2004;59:358–360. doi: 10.1179/acb.2004.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebo DG, Bridts CH, Stevens WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis from chlorhexidine: diagnostic possibilities. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:301–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garvey LH, Roed-Petersen J, Husum B. Anaphylactic reactions in anaesthetised patients - four cases of chlorhexidine allergy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:1290–1294. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.451020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garvey LH, Roed-Petersen J, Husum B. Is there a risk of sensitization and allergy to chlorhexidine in health care workers? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:720–724. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hausmann OV, Gentinetta T, Bridts CH, et al. The basophil activation test in immediate-type drug allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibler KS, Jemec GB, Garvey LH, et al. Prevalence of delayed-type and immediate-type hypersensitivity in healthcare workers with hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:223–229. doi: 10.1111/cod.12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiec-Swierczynska M, Krecisz B, Swierczynska-Machura D. Contact allergy in agricultural workers. Exogenous Dermatology. 2003;2:246–251. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krautheim AB, Jermann TH, Bircher AJ. Chlorhexidine anaphylaxis: case report and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:113–116. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liippo J, Kousa P, Lalmmintausta K. The relevance of chlorhexidine contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:229–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moscato G, Pala G, Crivellaro M, et al. Anaphylaxis as occupational risk. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:328–333. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagendran V, Wicking J, Ekbote A, et al. IgE-mediated chlorhexidine allergy: a new occupational hazard? Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:270–272. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakonechna A, Dore P, Dixon T, et al. Immediate hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine is increasingly recognised in the United Kingdom. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2014;42:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngajilo D. Occupational contact dermatitis among nurses: A report of two cases. Current Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014;27:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odedra KM, Farooque S. Chlorhexidine: an unrecognised cause of anaphylaxis. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:709–714. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-132291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opstrup MS, Malling HJ, Krøigaard M, et al. Standardized testing with chlorhexidine in perioperative allergy–a large single-centre evaluation. Allergy. 2014;69:1390–1396. doi: 10.1111/all.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opstrup MS, Johansen JD, Garvey LH. Chlorhexidine allergy: sources of exposure in the health-care setting. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114:704–705. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pemberton MN, Gibson J. Chlorhexidine and hypersensitivity reactions in dentistry. Br Dent J. 2012;213:547–550. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pemberton MN. Allergy to Chlorhexidine. Dent Update. 2016;43:272–274. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quirce S, Fiandor A. How should occupational anaphylaxis be investigated and managed? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;16:86–92. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000241. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato K, Kusaka Y, Suganuma N, et al. Occupational allergy in medical doctors. J Occup Health. 2004;46:165–170. doi: 10.1539/joh.46.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siracusa A, Folletti I, Gerth van Wijk R, et al. Occupational anaphylaxis--an EAACI task force consensus statement. Allergy. 2015;70:141–152. doi: 10.1111/all.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sivathasan N, Goodfellow PB. Skin cleansers: the risks of chlorhexidine. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51:785–786. doi: 10.1177/0091270010372628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart M, Lenaghan D. The danger of chlorhexidine in lignocaine gel: A case report of anaphylaxis during urinary catheterisation. Australas Med J. 2015;8:304–306. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2015.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toholka R, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis to chlorhexidine. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:303–306. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varoni E, Tarce M, Lodi G, et al. Chlorhexidine (CHX) in dentistry: state of the art. Minerva Stomatol. 2012;61:399–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vu M, Rajgopal Bala H, Cahill J, et al. Immediate hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine. Australas J Dermatol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ajd.12674. Doi: 10.1111/ajd.12674. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waclawski ER, McAlpine LG, Thomson NC. Occupational asthma in nurses caused by chlorhexidine and alcohol aerosols. BMJ. 1989;298:929–930. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6678.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittczak T, Dudek W, Walusiak-Skorupa J, et al. Chlorhexidine--still an underestimated allergic hazard for health care professionals. Occup Med (Lond) 2013;63:301–305. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqt035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]