Abstract

Given the dearth need for healthcare workers in the control of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, e-learning has been adopted in many settings to hasten the continuation of medical training. However, there is a paucity of data in low resource settings on the plausibility of online learning platforms to support medical education. We aimed to assess the awareness, attitudes, preferences, and challenges to e-learning among Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB) and Bachelor of Nursing (B.NUR) students at Makerere University, Uganda. An online cross-sectional study was conducted between July and August 2020. Current MBChB and B.NUR students aged 18 years or older constituted the study population. Using Google forms, a web-based questionnaire was administered through the Makerere University mailing list and WhatsApp messenger. The questionnaire was developed using validated questions from previously published studies. Overall, 221 participants responded (response rate = 61%). Of the 214 valid responses, 195 (92.1%) were Ugandans, 123 (57.5% were male, and 165 (77.1%) were pursuing the MB ChB program. The median age was 23 (18 to 40) years. Ownership of computers, smartphones, and email addresses were at 131 (61.2%), 203 (94.9%), and 208 (97.2%), respectively. However, only 57 (26.6%) respondents had access to high or very high quality internet access. Awareness and self-reported usage of e-learning (MUELE) platforms were high among 206 (96.3%) and 177 (82.7%) respondents, respectively. However, over 50% lacked skills in using the Makerere University e-learning (MUELE) platform. About half (n = 104, 49%) of the students believed that e-learning reduces the quality of knowledge attained and is not an efficient method of teaching. Monthly income (P = .006), internet connectivity quality (P < .001), computer ownership (P = .015) and frequency of usage of academic websites or applications (P = .006) significantly affected attitudes towards e-learning. Moreover, internet costs and poor internet connectivity were the most important barriers to e-learning reported by 199 (93%) and 179 (84%) students, respectively. Sensitization and training of students and faculty on e-learning and use of existing learning platforms are important to improve the attitude and use of e-learning. Blended online and use of offline downloadable learning materials would overcome the challenges related to the variable quality of internet access in the country.

Keywords: Medical education, e-learning, challenges, attitudes, COVID-19, medicine and nursing students, Uganda

Introduction

The coronavirus diseases-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had and continues to inflict far-reaching effects on all sectors across the globe. With over 40 million cases and over 1.1 million deaths by 18 October 2020, the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is still rapidly spreading in many countries globally.1 Medical education has been greatly impacted by the pandemic globally.2,3 Senior medical students in countries hit hard by the pandemic were fast-tracked to provide extra manpower at the hospitals.4,5 In Uganda, all schools were closed on March 20th, 2020, following the presidential guidance on the prevention of COVID-19 spread.6 All undergraduate students, including those pursuing medicine and nursing courses, were sent home and prohibited in the premises of some major university teaching hospitals nationwide.

As the lockdown is being eased, the National Council for Higher Education has issued guidelines for adoption of emergency open, distance, and e-learning in institutions of learning in Uganda to reduce the risks associated with the transmission of COVID-19.7 E-learning, also known as online education refers to the usage of electronic resources like internet, computers, and smartphones to acquire and disseminate knowledge.8 When enriched by audiovisual elements, e-learning can offer educational content and various tests supporting these contents, can facilitate access to necessary relevant information, and most importantly, provide an interactive environment for students and the faculty.9 In Uganda, many institutions of learning have adopted e-learning for various programs, commonly called open, distance, and e-learning (ODeL).

Medical education in Uganda is unique from other academic programs offered at higher institutions of learning. Students in clinical years come into direct contact with the patients as part of clinical clerkship. This presents further risks of transmitting SARS-COV-2 among students and patients. E-learning presents a valuable option for the continuation of medical education amid the pandemic. A report by the World Health Organization (WHO) assessing 33 studies demonstrated statistically significant knowledge gains for medical students allocated to computer-based learning methods compared to those allocated to traditional learning methods.10 Medical students in clinical years in a study also felt that e-learning had a positive impact on their learning of clinical skills.11 In India, up to 84% of first-year medical students recommended conventional teaching to be supplemented with e-learning.12

Whereas e-learning has been assimilated in most institutions in the developed world, academic institutions in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) have not fully scaled up e-learning.13 Challenges of e-learning in medical education in these countries include inadequate resources in terms of infrastructure (gadgets and internet) and skilled professionals to implement this platform.14 The perceptions of students are crucial for the success of e-learning in Africa. A study among medical students from 4 government universities in Khartoum, Sudan found that 96.8% knew, 70.4% had a positive attitude, and only 52.2% used e-learning services.15 However, no study has been conducted in Uganda to assess the perceptions of health profession students in Uganda, necessitating this study.

This study therefore aimed at assessing the awareness, attitudes, preferences, and challenges to e-learning among undergraduate medicine and nursing students at Makerere University, Uganda.

Methods

Study design

An online descriptive, cross-sectional mixed-methods survey was conducted in July and August 2020 while medical schools were still closed due to COVID-19.

Study settings

The study was conducted at Makerere University College of Health Sciences (MakCHS), the oldest medical school in Uganda, and among the best medical schools in Africa. There are currently ten accredited medical schools in Uganda. MakCHS is located at Mulago Hospital Complex, Mulago Hill, which also acts as its teaching hospital. MakCHS has 4 schools (School of Medicine, School of Biomedical Sciences, School of Public Health, and School of Health Sciences) offering 12 undergraduate degree programs with a population of approximately 2000 students as of academic year 2019/2020. The duration of study ranges from 3 to 5 years. Makerere University E-learning Environment (MUELE) is run by the e-learning department under the College of Education and External Studies. Most colleges at Makerere University have also adopted and integrated e-learning. At the College of Health Sciences, e-learning has been integrated for teaching at the School of Public Health and Bachelor of Biomedical Engineering. At the time of the study, e-learning had not been adopted for students pursuing a Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery (MBChB, School of Medicine) and Bachelor of Nursing (B.NUR, School of Health Sciences).

Study population

Undergraduate students pursuing MBChB and B.NUR were considered for the study. MBChB is a 5-year program and B.NUR is a 4-year program. Preclinical studies are done in the first 2 years and clinical teaching in the remaining 3 and 2 years for MBChB and BNUR respectively. In the 2019/2020 academic year, there are approximately 950 and 110 registered MBChB and B.NUR students, respectively.

Selection criteria

Undergraduate students aged 18 years or older, pursuing MBChB or BNUR at Makerere University for the Academic Year 2019/2020 were included in the study. Students unable to access the internet during the period of the study were excluded.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info 7 StatCalc (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, United States) for population surveys. Using population size = 950 for MBChB and 110 for B.NUR, expected frequency = 50%, acceptable margin of error = 5%, design effect =1.0 and clusters = 1 at 95% confidence interval, a sample size of 274 MBChB students and 86 BNUR students were calculated. Therefore, the total sample size was 360 students.

Data collection procedures

A self-reported web-based questionnaire was used to enroll participants in the study. The questionnaire was designed using Google Forms (Google LLC, California, United States of America). By convenience sampling, the link disseminated using MakCHS students’ institutional mailing list. The link to the questionnaire was also shared with cohort groups of eligible students on WhatsApp Messenger (Facebook Inc., California, USA). Data were collected within a period of one week from July 29th, 2020 to August 4th, 2020. Daily reminders were sent to the participants during the study period to increase the response rate.

Study variables

Independent variables included demographic characteristics like sex, age, academic program, year of study, nationality, current residence type (urban or rural), estimated monthly income, ownership of electronic gadgets (smartphone and computer), internet connectivity. Dependent variables were awareness, preferences, attitude and challenges to e-learning.

Questionnaire development

Awareness and preferences

Ten questions on; e-learning awareness, academic sites/application usage, proficiency in the most common e-learning platforms, preference of teaching delivery, and application of e-learning in the various components of medical education were developed by the authors.

Attitudes

This section consisted of five 5-point Likert items adopted from a validated questionnaire by Kisanga and colleague.16 The responses ranged from strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree, with each weighing 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. Some questions were reversed to reduce bias. A positive attitude was regarded as an average score of ⩾4 out of 5 on all the 5 items on the scale. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the 5 items was 0.73 indicating acceptable internal reliability.

Barriers

This section consisted of 1 semi-structured question. Questions on barriers were adopted from themes on the challenges faced by medical schools located in LMICs in the implementation of e-learning.14

Data management and analyzes

Completed questionnaires were extracted from Google Forms™ and exported to a Microsoft Excel 2016 for cleaning and coding. Cleaned data were then be exported to STATA version 16.0 for further analyzes. Numerical data were summarized as means and standard deviations. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. To assess the associations between categorical variables (sociodemographic characteristics) and attitudes towards e-learning, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (for categories with frequencies <5) was performed in STATA 16.0 software. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Major themes were generated from responses on the semi-structured question to barriers and coded.

COVID-19 safety precautions

The study was conducted following the guidelines by the Ministry of Health and the National COVID-19 Taskforce, Uganda. All study team meetings, training, recruitment, data collection, and manuscript drafting were conducted online.

Ethical consideration

Mulago Hospital Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol, Number MHREC 1897. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided informed electronic consent before participation.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Overall, 221 participants responded (overall response rate [221/360] = 61%, MBChB: 172/274 [63%], and BNUR: 49/86 [57%]). After cleaning and removing 7 duplicates, data from two hundred and fourteen (214) participants with a median age of 23 (range: 18-40) years were analyzed. The majority of the participants were male (58%), aged 18 to 23 years (53%), pursuing MBChB (77%) and were Ugandans (92%). Up to 70% and 67% of the participants were living in urban settlements and earned a monthly income of less than 50 000 Uganda shillings (UGX; 1 United States Dollar ($) = 3750 UGX), respectively. Whereas 95% (204) of the participants possessed smartphones, up to 39% lacked a computer or a laptop. Over 90% of the participants also possessed an email address (n = 208, 97%). When asked to rate their internet connectivity, 39% (n = 84) had moderate quality internet, however, up to one-third of the participants regarded their internet as of low quality. Table 1 summarizes the social and demographic characteristics of the study participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Demographics (N = 214) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 123 | 57.5 |

| Female | 91 | 42.5 |

| Age: Median (Range) years | 23 | 18 to 40 |

| 18 to 23 | 114 | 53.3 |

| ⩾24 | 100 | 46.7 |

| Academic program | ||

| Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery | 165 | 77.1 |

| Bachelor of Science in Nursing | 49 | 22.9 |

| Year of study | ||

| 1 | 27 | 12.6 |

| 2 | 48 | 22.4 |

| 3 | 52 | 24.3 |

| 4 | 64 | 29.9 |

| 5 | 23 | 10.8 |

| Nationality | ||

| Uganda | 197 | 92.1 |

| India | 6 | 2.8 |

| Rwanda | 4 | 1.9 |

| Tanzania | 3 | 1.4 |

| Nigeria | 2 | 0.9 |

| Kenya | 1 | 0.5 |

| South Sudan | 1 | 0.5 |

| Nature of current residence | ||

| Urban | 150 | 70.1 |

| Rural | 64 | 29.9 |

| Estimated monthly income (Uganda Shillings) | ||

| <50 000 | 144 | 67.3 |

| 50 000 UGX to 99 999 | 22 | 10.3 |

| 100 000 UGX to 499 999 | 29 | 13.6 |

| ⩾500 000 | 19 | 8.9 |

| Ownership of a smartphone | ||

| Yes | 203 | 94.9 |

| No | 11 | 5.1 |

| Ownership of a computer or laptop | ||

| Yes | 131 | 61.2 |

| No | 83 | 38.8 |

| Ownership of an email address | ||

| Yes | 208 | 97.2 |

| No | 6 | 2.8 |

| Rated internet connectivity | ||

| Very low quality | 28 | 13.1 |

| Low quality | 45 | 21.0 |

| Moderate quality | 84 | 39.3 |

| High quality | 40 | 18.7 |

| Very high quality | 17 | 7.9 |

E-learning awareness and preferences

A vast majority (96%) of the students had heard about e-learning. Only 17% (n = 37) had never visited academic websites or used academic applications. Over 60% of the participants required extra training to effectively utilize e-learning and up to 75% preferred blended method of teaching delivery (both e-learning and conventional classroom lectures). The majority of the students agreed that e-learning can be used for sharing learning material, lectures, revisions, and discussions (Figure 1). Table 2 summarizes awareness and preferences of the medicine and nursing students towards e-learning.

Figure 1.

Perceived applications of e-learning by medicine and nursing students at Makerere University.

Table 2.

Awareness and preferences towards e-learning among medicine and nursing students.

| Question | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Have you heard about e-learning? | ||

| Yes | 206 | 96.3 |

| No | 8 | 3.7 |

| How often do you visit the academic websites or applications? | ||

| Never | 37 | 17.3 |

| Sometimes | 153 | 71.5 |

| Always | 24 | 11.2 |

| I would require training to use e-learning platforms effectively | ||

| Strongly agree | 48 | 22.4 |

| Agree | 82 | 38.3 |

| Neutral | 51 | 23.8 |

| Disagree | 16 | 7.5 |

| Strongly disagree | 17 | 7.9 |

| Preferred learning methods | ||

| Both classroom lectures and e-learning | 161 | 75.2 |

| Conventional classroom lectures only | 40 | 18.7 |

| E-learning only | 13 | 6.1 |

Majority of the participants perceived having intermediate skills in using a computer, internet browsing, Zoom™, Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, and Emails. Strikingly, the majority of the students reported having no skills in using the MUELE platform (53%), Google Meet (59%), Webex (81%), and Google classroom (74%). Up to 25% of the participants had no skills in using the Zoom™ application. Interestingly, half of medicine and nursing students had expert skills in operating smartphones. Figure 2 shows the perceived proficiency of medicine and nursing students in the various technologies used for e-learning.

Figure 2.

Perceived and self-reported proficiency of medical and nursing students in the common e-learning platforms and tools (%).

Attitudes towards e-learning

Table 3 summarizes the response of participants to questions on attitudes towards e-learning. Close to 50% of medicine and nursing students believed that e-learning reduces the quality of knowledge attained (n = 104, 49%) and is not an efficient method of teaching (n = 104, 49%).

Table 3.

Attitudes of study participants to e-learning.

| No. | Questions | S A (%) | A (%) | N (%) | D (%) | S D (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | E-Learning should only be used for the distribution of notes over the internet (R). | 41 (19) | 67 (31) | 43 (20) | 42 (20) | 21 (10) | 2.7 ± 1.3 |

| A2 | E-learning ensures schedule flexibility. | 28 (13) | 77 (36) | 59 (28) | 32 (15) | 18 (8) | 3.3 ± 1.1 |

| A3 | E-learning reduces quality of knowledge attained (R). | 38 (18) | 66 (31) | 43 (20) | 50 (23) | 17 (8) | 2.7 ± 1.2 |

| A4 | E-learning technology is easy to use. | 10 (5) | 48 (22) | 61 (29) | 66 (31) | 29 (14) | 2.7 ± 1.1 |

| A5 | E-learning is not efficient as a teaching method (R). | 41 (19) | 63 (29) | 56 (26) | 41 (19) | 13 (6) | 2.6 ± 1.2 |

Abbreviations: S A, strongly agree; A, agree; N, neutral; D, disagree; S D, strongly disagree; SD, standard deviation.

Attitudes were scored as; S A- 5, A- 4, N- 3, D- 2, and S D- 1. For reversed items (R), scores were reversed and computed as S A-1, A-2, N-3, D-4, and S D-5. Mean scores are calculated out of a total of 5 representing a positive attitude and a minimum of 1, representing negative attitudes.

Table 4 shows the mean attitude scores of the participants and factors associated with the mean attitude scores. Overall, the mean attitude score was 2.8 (SD = 0.8) out of 5 implying an overall negative attitude towards e-learning by medicine and nursing students. Mean attitude scores increased with an increase in internet connectivity quality.

Table 4.

Mean attitude scores and factors associated with attitudes towards e-learning among medicine and nursing students at Makerere University.

| Demographics (N = 214) | Mean ± SD | Positive attitude | Negative attitude | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 12 | 111 | .974 |

| Female | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 9 | 82 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18-23 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 10 | 104 | .585 |

| ⩾24 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 11 | 89 | |

| Academic program | ||||

| Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 18 | 147 | .323 |

| Bachelor of Science in Nursing | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 3 | 46 | |

| Year of study | ||||

| 1 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 3 | 24 | .538 |

| 2 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2 | 46 | |

| 3 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 5 | 47 | |

| 4 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 9 | 55 | |

| 5 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2 | 21 | |

| Nationality | ||||

| Ugandan | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 18 | 179 | .224 |

| Non-Ugandan | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3 | 14 | |

| Nature of current residence | ||||

| Urban | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 17 | 133 | .252 |

| Rural | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 4 | 60 | |

| Estimated monthly income (UGX) | ||||

| <50 000 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 8 | 136 | .006 |

| 50 000 UGX to 99 999 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2 | 20 | |

| 100 000 UGX to 499 999 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 7 | 22 | |

| ⩾500 000 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4 | 15 | |

| Smartphone ownership | ||||

| Yes | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 21 | 182 | .261 |

| No | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0 | 11 | |

| Computer or laptop ownership | ||||

| Yes | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 18 | 113 | .015 |

| No | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 3 | 80 | |

| Email ownership | ||||

| Yes | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 20 | 188 | .567 |

| No | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 1 | 5 | |

| Rate your internet connectivity | ||||

| Very low quality | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0 | 28 | <.001 |

| Low quality | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 0 | 45 | |

| Moderate quality | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 13 | 71 | |

| High quality | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2 | 38 | |

| Very high quality | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 6 | 11 | |

| Have you heard about e-learning? | ||||

| Yes | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 21 | 185 | .342 |

| No | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 0 | 8 | |

| How often do you visit the academic websites or applications? | ||||

| Never | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0 | 37 | .006 |

| Sometimes | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 15 | 138 | |

| Always | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 6 | 18 | |

On bivariate analysis, estimated monthly income (P = .006), internet connectivity quality (P < .001), computer or laptop ownership (P = .015), and frequency of usage of academic websites or applications (P = .006) were significantly associated with attitudes towards e-learning among medicine and nursing students. Students who earned over 100 000 UGX and those who owned a laptop had more positive attitudes towards e-learning.

Barriers to e-learning

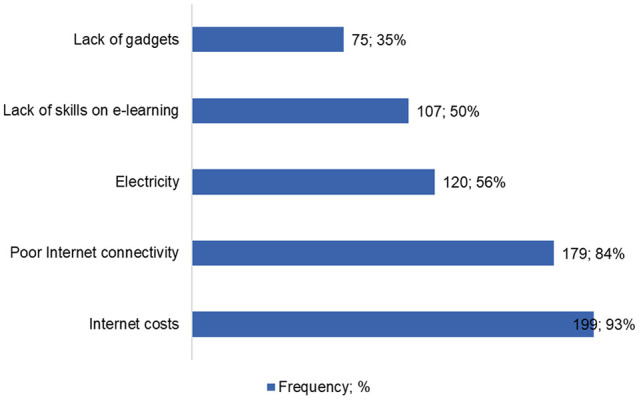

Figure 3 shows that internet costs and poor internet connectivity were cited as major barriers to e-learning access among medicine and nursing students at Makerere University. Also, over half of the students cited electricity challenges (n = 120, 56%) and lack of skills required to undertake e-learning (n = 107, 50%) as potential barriers. Some 35% (n = 75) chose the lack of gadgets like smartphones and personal computers are possible barriers to e-learning.

Figure 3.

Perceived barriers to e-learning access among medical and nursing students at Makerere University.

Discussion

COVID-19 is still an on-going pandemic and continues to negatively impact lives daily. With challenges like overcrowding in schools that can have potential in increasing the spread of SARS-CoV-2, virtual (computer or web-based) learning is on the rise as on-campus activities are on standstill.17 However, e-learning in low-resource countries is under-utilized in medical education.13 To our knowledge, this is the first study on awareness, attitudes, preferences, and barriers towards e-learning among medicine and nursing students in Uganda.

In this study, awareness of medicine and nursing students towards e-learning was high (96%) which correlates with findings from Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences in Iran where awareness was as high as 80%.18 At a medical school in Saudi Arabia, only 62% of health profession students knew about e-learning.19 Awareness is higher in studies done during the COVID-19 pandemic since most institutions have adopted e-learning in the absence of traditional lectures as a result of widespread lockdowns. A great number of students in our study had also visited academic websites or applications which is similar to that in Austria.20 The majority of students in our study had intermediate skills in popular information technologies required for e-learning. Successful implementation of an e-learning policy requires that the stakeholders are skilled in the various technologies required. Of concern, over half of the students had no skills in using MUELE. MUELE is the official e-learning platform used at Makerere University. Whereas MUELE has extensively been rolled out in other colleges, usage is low at the college of health sciences.

Medical education has practical sessions in anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry laboratories along with clinical bedside training that requires physical contact with the faculty and peer. This has been documented as a determinant of attitudes towards e-learning.14,21 In the present study, the lack of these practical / clinical exposures in the existing e-learning platforms including those at Makerere University was highlighted by the as a major caveat to e-learning for medical education in Uganda.

Although about half of the medicine and nursing students in this study perceived that e-learning reduces the quality of knowledge and is inefficient, up to 75% preferred blended learning, incorporating both traditional classroom or bedside lectures and e-learning. Utilizing both models ensures that students engage with the faculty in practical and bedside sessions as well as incorporating e-learning for theoretical sessions that do not require much physical. E-learning ensures flexibility,10 and reduces crowding in lecture rooms that are currently being faced at the college of health sciences due to the increased number of students admitted at the institution.

Our study showed that attitudes towards e-learning were generally negative. This is in line with a study among medical and dental students in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic, which found 77% having negative perceptions towards e-learning.22 However, medical students in Kerman and Shahid Sadoughi Universities of Medical Sciences in Iran had positive attitudes towards e-learning.23,24 Attitudes in our study differed by estimated monthly income, internet quality, ownership of a personal computer, and previous use of academic sites. Internet data costs in Uganda are high, costing as high as 2.67$ per gigabyte.25 Most undergraduate students at MakCHS receive financial support from their parents, guardians, or sponsors, except for a few who have a formal or an informal job. Many rural settings in Uganda also have poor bandwidth quality that makes access to the internet harder. All these influence attitudes towards e-learning. In our study, 61% of students possessed a computer unlike at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria where 94% had personal computers.20 Students who have personal computers have ease of using widely used word and PowerPoint applications, which are frequently needed for coursework assignments.

In addition to high internet data costs, poor internet quality was one of the most frequent barriers to e-learning in our study. This is in line with a study by Rafi and colleagues who reported that network issues affected up to 43.7% of medical students at Kerala while accessing e-learning during COVID-19 pandemic.26 In developed countries with good and cheap internet, e-learning has been assimilated as part of a blended education system, with both traditional lectures and e-learning. However, in developing countries, barriers like inadequate infrastructure and skilled personnel impede the enhancement of e-learning.14,21,27 Lack of electricity is a major cause of differences in internet use and smartphone penetration in urban and rural settings in Uganda.25

Moving forward, there exist viable options to ensure that e-learning is successfully integrated into medical education in Uganda. Firstly, universities can liaise with companies that manufacture computers or smartphones and establish a scheme for cheaper and affordable gadgets that are compatible with e-learning. Multilateral agreements with telecom companies to provide access to important e-learning applications like Zoom, Google Meet, MUELE, etc., for free thus reducing costs and increasing acceptability among students. Provision of good quality reading materials that can be downloaded and later used offline by the students both in soft and hard copies can be relieving for students who lack gadgets and face electricity problems.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, data were collected using an online questionnaire; therefore, students who were unable to access the internet at the time of data collection were unable to participate creating a potential selection bias. Therefore, awareness, preferences, and attitudes towards e-learning could potentially be inferior to those reported in this study. Secondly, this was a single center study with relatively small sample size and may not reflect the state of e-learning among this population in Uganda. Thirdly, our study highlights the perceived skill level which may or may not reflect actual skill level.

Conclusion

Awareness about e-learning among medicine and nursing students at Makerere University is high, however, attitudes are negative. High internet costs, poor internet connectivity, limited technical skills on the usage of e-learning platforms, and challenges in accessing electricity are common barriers to access or e-learning among the students. Addressing these challenges requires collaboration between the university and important stakeholders like the government, private partners like telecom companies, and the parents. Sensitization and training of medicine and nursing students and the faculty on the use of existing e-learning platforms is also recommended. Follow-up qualitative studies are suggested to explain the e-learning related attitudes described in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Allan Kanyesigye, Julius Sente, Clement Egwela, Charity Bulage, Blaise Kiyimba, Eden Mukisa, Kadooma Derrick, Abraham Matovu, Hilda Nanfuka and Ivaan Pitua for the assistance in data collection. The authors also appreciate Ms. Evelyn Bakengesa, Ms. Rhoda, and Ms. Regina from HEPI-SHSSU for their support towards funding acquisition.

Footnotes

Funding:Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of State’s Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy (S/GAC), and President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) under Award Number 1R25TW011213. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contributions: Conceptualization: RO and FB. Study design: RO, LA, AM, DRN, FB, and SK. Data curation: RO, LA, EK, AM and DN. Formal analysis: RO. Writing manuscript-original draft: RO, FB, and DRN. Writing manuscript-revision: RO, LA, AM, EK, DRN, FB, and SK. Supervision: FB and SK. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Ronald Olum  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-0111

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-0111

References

- 1. Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Accessed October 18, 2020 https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 2. Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:777-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:2131-2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harvey A. Covid-19: medical schools given powers to graduate final year students early to help NHS. BMJ. 2020;368:m1227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang JH, Tan S, Raubenheimer K. Rethinking the role of senior medical students in the COVID-19 response. Med J Aust. 2020;212:1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bozkurt A, Jung I, Xiao J, et al. A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 Pandemic: navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian J Distance Educ. 2020;15:1-126. [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Council for Higher Education. Guidelines for Adoption of An Emergency Open, Distance and E-Learning (ODeL) System By The Higher Education Institutions During the Covid-19 Lockdown. National Council for Higher Education; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masic I. E-learning as new method of medical education. Acta Inform Med. 2008;16:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sezer B. Faculty of medicine students’ attitudes towards electronic learning and their opinion for an example of distance learning application. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:932-939. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. eLearning for Undergraduate Health Professional Education: A Systematic Review Informing a Radical Transformation of Health Workforce Development. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gormley GJ, Collins K, Boohan M, Bickle IC, Stevenson M. Is there a place for e-learning in clinical skills? A survey of undergraduate medical students’ experiences and attitudes. Med Teach. 2009;31:e6-e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hiwarkar M, Taywade O. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and skills towards e-learning in first year medical students. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7:4119. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barteit S, Jahn A, Banda SS, et al. E-learning for medical education in Sub-Saharan Africa and low-resource settings: viewpoint. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e12449-e12449. doi: 10.2196/12449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frehywot S, Vovides Y, Talib Z, et al. E-learning in medical education in resource constrained low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alkanzi FK, Abd-Algader AA, Ibrahim ZA, Krar AO, Osman MA, Karksawi NM. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice in Electronic Education among Teaching Staff and Students in Governmental Medical Faculties-Khartoum State. Sud J Med Sci. 2014;9:43-48. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kisanga D, Ireson G. Test of e-Learning Related Attitudes (TeLRA) scale: development, reliability and validity study. Int J Educ Dev Using ICT. 2016;12:20-36. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chandratre S. Medical students and COVID-19: challenges and supportive strategies. J Med Educ Curr Dev. 2020;7:2382120520935059. doi: 10.1177/2382120520935059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lakbala P. Barriers in implementing E-learning in Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8:83-92. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Algahtani H, Shirah B, Subahi A, Aldarmahi A, Ahmed SN, Khan MA. Perception of students about E-learning: A Single-center Experience from Saudi Arabia. Dr Sulaiman Al Habib Med J. 2020;2:65-71. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Link TM, Marz R. Computer literacy and attitudes towards e-learning among first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, McGrath D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education–an integrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:130. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abbasi S, Ayoob T, Malik A, Memon SI. Perceptions of students regarding E-learning during Covid-19 at a private medical college. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36:S57-S61. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okhovati M, Sharifpoor Ghahestani E, Islami Nejad T, Hamzezadeh Marzooni M, Motamed Jahroomi M. Attitude, knowledge and skill of medical students toward E-learning Kerman University of Medical Sciences. دانش، نگرش و مهارت دانشجویان پزشکی نسبت به آموزش الکترونیک؛ دانشگاه علوم پزشکی کرمان Edu-Str-Med-Sci. 2015;8:51-58. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mirzaei M, Ahmadipour F, Azizian F. Viewpoints of students of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences towards E-learning in teaching clinical biochem-istry. بررسی نگرش دانشجویان دانشگاه علوم پزشکی یزد نسبت به بکارگیری آموزش الکترونیکی در تدریس بیوشیمی بالینی JMED. 2012;7:67-74. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gillwald A, Mothobi O, Ndiwalana A, Tusubira FF. The State of ICT in Uganda. Research ICT Africa; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rafi AM, Varghese PR, Kuttichira P. The Pedagogical Shift During COVID 19 Pandemic: Online Medical Education, Barriers and Perceptions in Central Kerala. J Med Educ Curr Dev. 2020;7:2382120520951795. doi: 10.1177/2382120520951795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ekenze O, Okafor C, Ekenze S. High Internet awareness and proficiency among medical undergraduates in Nigeria: a likely tool to enhance e-learning/instruction in Internal Medicine. Original Article. Int J Med Health Dev. 2019;24:9-17. doi: 10.4103/ijmh.IJMH_1_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]