Abstract

Background:

The Morehouse School of Medicine Patient Centered Medical Home and Neighborhood Project was developed to implement a community-based participatory research driven, integrated patient-centered medical home and neighborhood (PCMH) pilot intervention. The purpose of the PCMHN was to develop a care coordination program for underserved, high-risk patients with multiple morbidities served by the Morehouse Healthcare Comprehensive Family Health Clinic.

Measures:

A community needs assessment, patient surveys and provider interviews were administered.

Results:

Among a panel of 367 high-risk patients and potential participants, 93 participated in the intervention and 42 patients completed the intervention. The patients self-reported increased utilization of community support, increased satisfaction with health care options, and increased self-care management ability.

Conclusion:

The results were largely attributable to the efforts of community health workers and targeted community engagement. Lessons learned from implementation and integration of a community-based participatory approach will be used to train clinicians and small practices on how to affect change using a care coordination model for underserved, high-risk patients emphasizing CBPR.

Keywords: Patient-Centered Medical Home, community engagement, care coordination, community-based participatory research, social determinants of health

Introduction

A Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model is the foundation upon which to build systems designed to improve clinical outcomes among multi-morbidity patients from high-disparity neighborhoods. According to the Joint Principles of the Patient-centered Medical Home the PCMH-setting necessitates a personal physician allocated to each patient, a physician directed medical practice, whole person orientation, coordinated care among all elements across all elements of the healthcare system, safe and quality care and systems through which patients and their families actively participate in decision-making. Other elements include enhanced access to care and a proper payment framework that recognizes the added value provided to patients.1 Howard et al indicated that cultural appropriateness based on the population groups, especially pertaining to PCMH, is importance to success. It is assumed that true transformation to a PCMH requires a considerable shift in the culture of practice and consequently the workflow models.2,3 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality community-clinical linkages aligned with PCMH and highlights success stories of linking clinical practices to community organizations. Their resources have included better access methods, prevention approaches, and evidence-based strategies for providing integrated care.4,5 Similar to the PCMH model, the Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) model is capturing interest among a new generation of physicians and medical students who aim to improve health outcomes at a population level. The care team associated with this model puts considerable emphasis on defining the population group and locating the community partners to expand primary care access in community settings.6

The models and approaches detailed above prioritize and position the community as central stakeholders is critical in the development of the PCMH, particularly among high-risk underserved populations who have been marginalized in both healthcare settings and in research conducted by academic institutions. Community is contextually defined by the neighborhood and support systems in the neighborhood that help facilitate and/or maintain health-promoting practices. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a complementary approach toward PCMH development. It enhances health outcomes due to attention to the social determinants of health that go far beyond the individual in the clinical setting and extends reach to the neighborhoods where the patient manages chronic conditions with implications for a more responsive medical neighborhood.

The Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) PCMH pilot intervention was developed in 2014 to implement an integrated and community engagement project. The purpose was to develop a care coordination program for high-risk patients with multiple morbidities. Identified patients participated in a targeted intervention consisting of home visits by community health workers (CHWs), clinic visits with primary care physicians, and linkages to community supports. The purpose of this study is to illustrate how to engage neighborhoods and communities in support of the PCMH using CBPR and to show how the outcomes of patient participation, requested services and satisfaction of the PCMHN pilot informed the development and implementation of this model.

Health disparity populations experience a disproportionately higher percentage of chronic and infectious diseases when compared to other groups.7 The U.S. is at a critical juncture toward advancing health equity through strategies that improve the healthcare of ethnoracial minorities and, in turn, the health of the nation. Identifying effective multilevel strategies require an understanding of a neighborhood’s ecology toward approaches that are community-led, -implemented, and -sustained.

Engagement of patients and families in the design and the functioning of the PCMH is outlined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and includes 3 contexts: (1) care for the individual patients, (2) primary care practice improvement, and (3) policy design and implementation.8 Some researchers concluded that the feasibility of different strategies to strengthen patient engagement needs to be studied further, because the current evidence needed to support policy efforts is limited.8 If done properly, patient engagement within healthcare systems can minimize health disparities through culturally tailored approaches for treatment of chronic diseases.

Methods

Setting

MSM’s array of population health, community outreach and primary/specialty care assets within the enriched PCMH in East Point, a city south of Atlanta, Georgia. The PCMHN is centered around the Comprehensive Family Health Clinic (CFHC) in the 30344 (East Point) neighborhood.

Patient Population

Preparation for the PCMHN pilot intervention began April 2014 with a community-based assessment to determine community needs and attitudes toward healthcare.9 In order to develop a community-driven approach, community needs assessment and community asset mapping were used to determine most contextually appropriate PCMHN approach. The MSM Prevention Research Center (PRC) conducted a qualitative and quantitative assessment of zip code 30344 and surrounding communities, adapted from a previously conducted needs assessment.10 The purpose was to (1) select the demographic profile, health needs, priorities and assets of the communities served and (2) develop community-based recommendations to plan, implement and evaluate research, disease prevention, health promotion, and clinical services related to PCMHN implementation. The community needs assessment results underscored the need for a CBPR approach to be utilized in the development of the PCHMN.

Intervention

The PCMHN’s purpose necessitated a “neighborhood” feature of the intervention. Selected patients participated in a targeted 90+ day intervention, The intervention consisted of 4 home visits by CHWs, at least 1 clinic visit with their primary care physician, development of an individualized plan of care encouraging and supporting patient self-care management, linkages to community supports and community engagement activities.

The PRC and care coordination teams were key components of PCMHN planning and implementation. The PRC staff, consisting of a research assistant and 2 community health workers, served as advisory team members, community support liaisons and facilitators of community linkages. The PRC staff assisted the PCMHN in creating patient linkages with community-based organizations offering prioritized supports, tracking community supports using the Healthify system,11 training CHWs in community engagement, participating in PCMHN-CFHC referral coordination, and completing home visits with patients (CHWs). The care coordination team consisted of the project director, physician champion, CFHC resident physicians, 4 CHWs, a community supports and engagement specialist, a data analyst, a data coordinator, a nurse care manager, and a licensed clinical social worker. All met for at least 2 hours every week in a care coordination team meeting to discuss the needs of patients who were scheduled to have home visits that week and patients who received home visits the week prior.

Table 1 details a CBPR conceptual model used to understand patient engagement activities and related implementation phases. It is CBPR impact model adapted from Oetzel et al12 During Phase 1 (planning), key contexts were social, structural, and political. Policy changes, capacity building, practice readiness, collaboration and trust with the stakeholders were priority contextual determinants. During this formative research planning phase, staff met with the MSM PRC Community Coalition Board (CCB) to determine the cost (fiscal and non-fiscal) of care for high-risk patients and identified 7 major areas that needed to be addressed: (1) team-based care, (2) practice organizations, (3) knowledge and management of patients, (4) patient-centered access and continuity, (5) care management and support, (6) care coordination and care transition, and (7) performance measurement and quality improvement.

Table 1.

PCMHN + CBPA Conceptual Model- Building the “Neighborhood” in MSMs PCMHN.

| PCMHN Implementation Phases | 2014 Planning Grant (Phase 1) May 2014-December 2014 | Pilot Grant (Phase 2) January 2015-December 2015 | Care Coordination Dashboard Development Grant (Phase 3) January 2016-June 2018 | December 2014-2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBPR Conceptual model | Context | Partnership Process | Intervention | Outcomes | |

| Social and Structural Political and Policy Health Issue Importance Capacity and Readiness Collaboration and Trust |

Individual characteristic Relationships Partnership structures |

Processes Integrate community knowledge Empowering processes Community involved in research |

Outputs Culture-centered Interventions Partnership synergy Appropriate research design |

Intermediate Policy environment Sustained partnership Empowerment Equal power relations in research Cultural reinforcement Individual/agency capacity Research productivityLong-term Community transformation Social justice Health/health equity |

|

| PCMHN comparison to CBPR Conceptual model | Met with MSM PRC CCB to identify health/health care priorities Health issue of cost of care with high-risk patients-project addresses PCMH recognition program concept areas Team-based Care and Practice Organization Knowing and Managing your patients Patient-centered Access and Continuity Care management and Support Care Coordination and Care Transitions Performance Measurement and Quality Improvement |

PRC-CCB formative research United Health Foundation (funder) input MSM- academic MHC Clinical Morehouse ACO-LPCMH info/med= ACO policy Community agencies-What does partnership look like-agreements? |

Processes Linkages to social supports-list Outputs Doc policy/charter for advisory Empowering patient=chw facilitated self-care Clinic staff-workflow develop from high risk patient Integrated community knowledge=CHWs from the neighborhood |

Intermediate Agency capacity practice improvement care Care coordination toolkit Cognitive shift in family medicine now speaking “community” the inclusion of community considerations in the clinical enterprise such as focus on determinants that may impact health outcomes. Community engagement practice improvement in community Research productivity |

|

In Phase 2 (pilot implementation), key partnership processes included studying the characteristics of each collaboration, maintaining working relationships and establishing partnership structures. This time was used to lay the foundation for the research with the CCB and utilized input received from United Health Foundation to complete the pilot intervention. Optum Labs (a subsidiary of United Health Group) supplied data analytics expertise to assist in the development of care coordination dashboards utilized by the care coordination team. Central during this phase were accountable care organization (ACO) partnerships. The Morehouse ACO was simultaneously developing a care coordination program that was expanded toward incorporation of lessons learned from the pilot intervention. Later, the MSM model and the ACO model were merged.13 Collaborations with community agencies were also critical during this period. These partnerships allowed for important resource referrals for patients served; such as diabetes management classes, exercise and nutrition resources, smoking cessation classes, bill pay assistance and transportation assistance Central to all of these partnerships was the recruitment of CHWs from the neighborhood to ensure integrated community knowledge.

In Phase 3, dashboard development, the intervention was planned with an intent to integrate community knowledge and thereby inform culturally-sensitive interventions. Interfacing with community-based organizations allowed for the identification of the resources necessary to provide social supports prioritized by community residents/patients. A policy for the development of a patient advisory board was drafted and facilitated self-care programs for patients were established. During this phase, a work-flow that prioritized high-risk patients was developed.

Strategies and Data Collection Tools

Care for the individual patient

Assessment of community support utilization by patients.

During home visits, CHWs used an electronic survey on their tablets to ask patients if there were any supports needed related to their health and well-being utilizing motivational interviewing as necessary. Assessment questions asked included questions about patient support systems, personal hygiene and community supports needed by patient. A list of questions asked is provided in the appendix. Data was sent via secure data transfer to the PCMHN care coordination data warehouse where data was analyzed and discussed by the data analyst at the weekly care coordination meeting. The community engagement specialist entered that data into the Healthify system11 to match requests with community organizations providing those supports. The CHW then completed a “warm handoff” via telephone call to link those patients to the requested community supports.

Self care management

Assessment of CHW effort toward patient self-care management.

During the home visits CHWs helped patients develop their own health goals using care plan “I” statements and learn to manage their own care (patient self-care management). They also signed up patients up for Webview (EHR patient portal) and demonstrated use, set their clinic appointments, assisted with additional appointments with specialists, and linked patients to community supports. Common issues and proposed solutions were discussed by care coordination team (medicine non-compliance, family conflict, readiness to change). The CHWs used an electronic survey on their tablets to collect information from patients regarding progress on self-care management. A list of questions asked is provided in the appendix. The data was sent via secure data transfer to the PCMHN care coordination data warehouse where data was analyzed and discussed by the data analyst at the week care coordination meeting. The Physician Champion and Nurse Care Manager contributed to patient progress reports during the weekly care coordination meeting and made suggestions to the CHWs to assist patients with reaching self-management goals.

Practice improvement

Assessment of linkages to community support.

The Community Engagement Specialist, with assistance of the Data Analyst, analyzed number and type of community supports requested by patients. The Community Engagement Manager developed linkages with agencies in the targeted communities, visited those agencies to discuss the PCMHN program and to develop Memorandums of Agreement with those agencies to ensure patients would have access to those supports.

Results

Patient Panel and CHW efforts

CFHC patients were stratified by chronic health conditions using an innovative stratification process detailed elsewhere.9 High-risk patients were defined as those who are 40 to 75-years of age and who had multiple risk factors that were managed through focused coordination of 2 or more chronic health conditions and at least 1 behavioral health issue. High-risk patients (367 out of the 5364 CHFC patient panel) were assigned to the PCMHN pilot. The average age was 59 years; the sample was 74% female; and 43% were Medicare recipients.

Among a panel of 367 high-risk patients and potential participants, 93 participated in the intervention and 42 patients completed the intervention. Community Health Workers (3 FTE) conducted 261 total home visits between July 1, 2015 and January 31, 2016. Initial home visits averaged 1.5 to 2 hours in duration and follow-up visits averaged 45 minutes to 1.5 hours in duration. Forty-two patients completed all 4 home visits; 14 patients completed 3 home visits; 15 patients completed 2 home visits; 21 patients completed 1 home visit.

Community support utilization by and satisfaction of patients

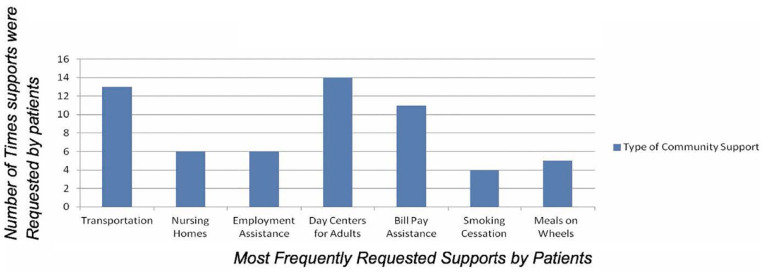

The “neighborhood” part of the PCMHN was designed to improve population health by linking the patient panel to community supports within their neighborhood. Priority community supports were initially identified through the needs assessment process and referrals were subsequently made by the care coordination team and CHWs during home visits. Transportation, day centers for adults, and bill-pay assistance were among the most referred supports. Figure 1 illustrates the most requested community supports by participants and the number of times during the pilot period those supports were requested.

Figure 1.

Frequency of community support.

Assessment of linkages to community support

Patients self-reported their experience in utilization of these supports. Among those who completed 4 home visits indicated 56% were satisfied with the services received. All (100%) indicated that the treatment received was better than that which they experiences at other health care systems. Nearly all (97%) felt that services offered met all of their health care needs. All (100%) patients said they used the supports and were satisfied with their benefits. Patient Satisfaction questions at fourth (Final) home visit are included below:

How happy are you with the services you receive at MHC?

Do you feel the treatment you receive for MHC is better than other healthcare systems?

Do you feel the services offered at MHC meet all of your health care needs?

If you used the community supports recommended, are you satisfied with the benefits?

Community level outcomes

Long-term outcomes of PCMHN integration were evidenced by the cognitive shift and culture in the practice of Family Medicine, which now also focuses on the community, as opposed to sole the individual patients. The ramifications of prioritizing the concept of community led to the creation of several community-facing programs led by student, preparing clinicians or youth for careers in the health professions. First, the Health Equity for All Lives (H.E.A.L.) Clinic, a free student-run community-based clinic serves those community members without insurance. Second, the High School Community Health Worker training program is designed to teach students how to care for their own health and the health of their family and community members. Third, the Community Health Advanced by Medical Practice Superstars program, which engages Medical Doctors and Physician Assistants to create Quality improvement projects in their clinical spaces in an effort to improve community health outcomes.

Discussion

Historically, PCMH models have been developed with strong support related to the important roles of patients, but few have reported how results of how their engagement has been used to inform responsive interventions. CBPR is a promising approach toward a patient-engaged PCMH model because it emphasizes the fostering, deployment and sustaining of community partners that share leadership in the planning, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of “innovative, culturally appropriate and evidence-based interventions that enhance translation of research findings for community and policy change.”7,10 The CBPR-driven PCMH can potentially elevate identification of the perspectives, preferences, and priorities of the communities with whom interventions are developed toward more effective and responsive health care systems.10

During the final phase, the evaluation of pilot, intermediate and long-term outcomes from the project were established (see Figure 1). Intermediate outcomes encompassed policy making, empowering the community, establishing equal power among the stakeholders, cultural reinforcement, capacity building for individual and agency practices, and conducting the demonstration project (pilot intervention). Intermediate outcomes were achieved by demonstrating an improvement in care by the practice agencies.9 Moreover, a coordination toolkit was designed to help community navigation of the system.

Conclusion

This study was designed to discuss the marriage of CBPR with a PCMHN project and to describe a model of planning and implementing community engagement in the context of a PCMH. Successful integration prioritizes community input, thereby increasing the likelihood of sustainability in the planning stages and not as an afterthought. The systemic community engagement processes detailed within this PCMHN model is one feasible and potentially-effective strategy for institutions seeking to achieve health equity in their own communities.

Appendix

Community support utilization assessment questions

Do you have a family or social supports system in place? Yes/no

- Do you need assistance with the following yes/no

- ■ Dressing

- ■ Bathing

- ■ Toileting

- ■ Transferring/Reposition in Bed or Chair

- ■ Feeding

- ■ Meals (Preparation or shopping)

- ■ Medical equipment repair/replacement

- ■ Housekeeping

- ■ Transportation to/from office visits

- ■ Health Insurance

- ■ Other? (The CHW also made suggestions based on observation/knowledge of Patient needs)

Since our last visit, have you used any of the referrals to supports? If so which ones and when? (CHW goes over list of requested supports with patient)

Are there any new resources needed?

Patient self-care management assessment questions

- CHW observation of patient/home include:

- 1. Grooming/Hygiene

- 2. Movements

- 3. Environment

- 4. Safety

- 5. Fall risk assessment

- Self-care Management assessment questions asked:

- 6. Medication Adherence yes/no:

- ■ Do you take your medication as prescribed? If no, why not?

- ■ Are you able to obtain all of your prescriptions? If no, why not?

- ■ Are you able to independently take your medication?

- ■ Are you able to take your medication if someone sets them up for you?

- 7. Patient self-care goals (developed in conjunction with CHW and PCP)

- ■ Where are you with your self-care goals? IG= INITIATED GOAL IP=IN PROGRESS GM=GOAL MET GU=GOAL UNMET (these are read as “I” patient health behavior statements)Maintain/enhance cardiovascular/blood pressure functioningPrevent complications of disease processesProvide information about disease process and treatment regimenSupport active patient control of conditionCardiovascular and other systemic complications prevented/minimizedDisease process and therapeutic regimen understoodNecessary lifestyle/behavioral changes initiated/maintainedPlan in place to meet needs after discharge (if applicable)

- ■ What barriers are you having to meeting your goals?

- 8. Overall Care coordination/self-care

- ■ Do you feel that we (Care Coordination team) talked with you about your concerns?

- ■ Do you feel we (Care Coordination team) have included you and your family in the planning of your healthcare goals?

- ■ Do you have a central role in managing your healthcare condition?

- ■ Do you feel the CHW home visits help play a role in managing your healthcare concerns?

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from the United Health Foundation. The sponsor was not involved in the conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

ORCID iD: Arletha Williams-Livingston  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4890-5568

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4890-5568

References

- 1. Acponline.org. Joint principles of a patient-centered medical home released by organizations representing more than 300,000 physicians. ACP Newsroom, ACP. https://www.acponline.org/acp-newsroom/joint-principles-of-a-patient-centered-medical-home-released-by-organizations-representing-more-than. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 2. Howard J, Etz R, Crocker J, et al. Maximizing the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) by choosing words wisely. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:248-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NCQA. Patient-centered medical home (PCMH) - NCQA. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers-practices/patient-centered-medical-home-pcmh/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 4. Hahn K, Gonzalez M, Etz R, et al. National Committee For Quality Assurance (NCQA) Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) recognition is suboptimal even among innovative primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:312-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahrq.gov. Clinical-community linkages. 2020. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/community/index.html. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 6. Laff M. Community-oriented primary care shows promise in value-based era. 2017. https://www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20170124grahamcopc.html. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- 7. Cdc.gov. 2020. CDC health disparities & inequalities report (CHDIR) - Minority Health - CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/CHDIReport.html. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 8. Pcmh.ahrq.gov. Engaging patients and families in the medical home. 2020. PCMH Resource Center. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/engaging-patients-and-families-medical-home. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 9. Xu J, Williams-Livingston A, Gaglioti A, et al. A practical risk stratification approach for implementing a primary care chronic disease management program in an underserved community. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29:202-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akintobi T, Lockamy E, Goodin L, et al. Processes and outcomes of a community-based participatory research-driven health needs assessment: a tool for moving health disparity reporting to evidence-based action. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2018;12:139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Healthify.us. Social determinants of health management-healthify. 2020. https://www.healthify.us/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 12. Oetzel J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, et al. Impact of participatory health research: a test of the community-based participatory research conceptual model. Biomed Res Int. 2018;1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown M, Ofili E, Okirie D, et al. Morehouse Choice Accountable Care Organization And Education System (MCACO-ES): integrated model delivering equitable quality care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]