Haeusler et al. (1) suggest that our analysis (2) of the distribution of relative bone volume across the articular surface (figure 5) does not justify different taxonomic allocations or locomotor classifications. We agree with their first suggestion, and we did not use these data to make direct arguments for the taxonomic attribution of either specimen in our paper. With regard to locomotor classifications, we note that our results “further [support] the inferred differences in loading between these two specimens as evidenced by their internal BV/TV distribution” (2). The strongest evidence for locomotor differences between StW 522 and StW 311 comes from the internal distribution of trabecular bone, which is not captured by the geometric morphometric analysis of articular surface relative bone volume.

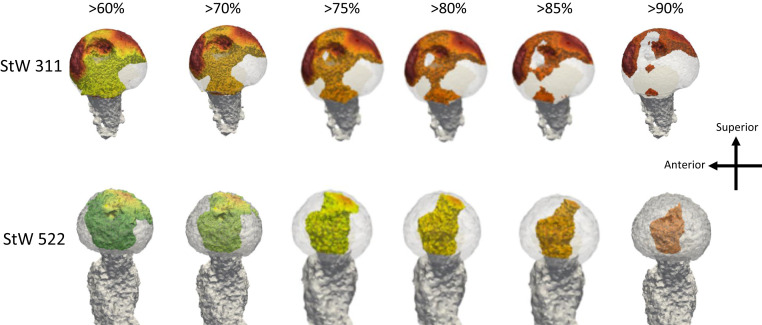

Haeusler et al. suspect our method of scaling relative bone volume (bone volume/total volume [BV/TV]) could have obscured an anteriorsuperior trabecular bundle in StW 522. Our original figure S5 (2) showed three different BV/TV thresholds (75th, 80th, and 85th percentiles) with specimens scaled to their own range (the most appropriate way to show patterns of distribution). In Fig. 1, we show three additional thresholds for StW 311 and StW 522. We maintain that StW 522 does not exhibit the nonhuman ape-like double pillar that is present in StW 311 and by extension that these two fossil hominins habitually practiced differing locomotor behavior. The slightly elevated BV/TV across the superior articular surface of StW 522 is also present in both fossil and modern humans, and is clearly distinct from the secondary, anteriorly positioned pillar in StW 311 and nonhuman apes.

Fig. 1.

Relative bone volume distribution in the femoral head of StW 311 and StW 522. From Left to Right are distribution maps showing regions at increasing percentiles of bone density scaled to each femur.

Finally, Hauesler et al. suggest that the stratigraphic context of StW 311 is uncertain and that this cannot be used to inform the taxonomic attribution of this specimen. Various authors have interpreted Member 4 (M4) as extending into the western area of the site, known as the “Extension Site” (3–5). However, apart from the isolated, collapsed blocks of M4 (Robinson’s Lower Breccia), M4 exposures are restricted to the southern breccias, and not close to the R53 grid square where StW 311 was found and are heavily eroded remnants underlying artifact-bearing deposits of Member 5 (M5). “Interfingering” of M4 and M5 is a result of deep and irregular erosion of M4. Furthermore, the original talus of M4 becomes deeper from south to north at the Extension Site (6), regardless of the additional gradient and incision caused by postdepositional erosion of M4. At just 14’5” to 15’5” below datum, StW 311 is well above the 22’ level that separates the Early Acheulean-bearing M5 from the underlying M5 Oldowan. The eastern boundary between M4 and M5 is complicated, but Oldowan-attributed artifacts were excavated from deeper levels of R53, and there is no stratigraphic evidence that in situ M4 overlies the Oldowan-bearing M5 (3). Given this evidence, it is highly unlikely that StW 311 derives from M4. Coupled with evidence for differing internal bone structure in the femoral heads of StW 311 and StW 522, we maintain there is strong evidence for both taxonomic and locomotor diversity at Sterkfontein.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Hauesler M. et al., Locomotor and taxonomic diversity of Sterkfontein hominins not supported by current trabecular evidence of the femoral head. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 28568–28569 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgiou L. et al., Evidence for habitual climbing in a Pleistocene hominin in South Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 8416–8423 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuman K., Clarke R. J., Stratigraphy, artefact industries and hominid associations for Sterkfontein, Member 5. J. Hum. Evol. 38, 827–847 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogola C. A., “The Sterkfontein Western Breccias: Stratigraphy, fauna and artefacts,” PhD dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa (2009).

- 5.Robinson J. T., Sterkfontein stratigraphy and the significance of the Extension Site. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 17, 87–107 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stiles D. N., Partridge T. C., Results of recent archaeological and palaeoenvironmental studies in the Extension Site. S. Afr. J. Sci. 75, 346–352 (1979). [Google Scholar]