Abstract

Objectives

To analyse characteristics and developmental trends of clinical study registration primarily sponsored by China’s institutions during 2009–2018.

Setting

Registration information registered prior to 31 December 2018 was obtained from the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) source registries, including Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry and International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number. Registration information on other ICTRP source registries was collected from the ICTRP.

Design

A cross-sectional analysis was performed. The studies sponsored by mainland China’s institutions (not including institutions in Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR or Taiwan of China) as of 31 December 2018 were filtered. For duplicate registrations, only the records with the earliest registration date were included. Global registrations were summarised for comparison.

Results

A total of 32 557 China-sponsored studies and 478 261 global studies were included. The registered China-sponsored studies, increased from a cumulative number of 1333 in 2009 to 32 557 in 2018, were less likely to have industry involvement (14% vs 30%) and more likely to be registered prospectively (63% vs 45%) than the global registrations during 2009–2018. The top three most studied health conditions were lung cancer (4.2%), diabetes (3.8%) and ischaemic heart disease (3.2%). Depression and depressive disorders and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) each represented 1.1% of registered China-sponsored studies. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials together accounted for 30%, notably lower than the global level (53%). The registered studies responding to an individual participant data (IPD) sharing plan had increased since 2016, but the proportions of studies indicating ‘yes’ were still at a low level and accounted for 5% of the registered China-sponsored studies and global registrations.

Conclusions

Clinical study registration activity in China has been substantial during 2009–2018. Some diseases with a high disease burden in China (depression and depressive disorders and COPD) were underrepresented by the proportion of registered studies. The accessibility of IPD merits improvement.

Keywords: medical ethics, health informatics, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study first focused on registered clinical studies primarily sponsored by China’s institutions that were registered in 18 International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) source registries around the world.

Global registrations were also summarised for comparison with registered studies sponsored by China, and the total number of studies analysed reached over 478 000.

The study focus of registered studies sponsored by China was analysed in the context of disease burden in China, which might indicate some areas that need more research.

We only recruited ICTRP source registries and did not include the registrations on the Platform for Registry and Publicity of Drug Clinical Trials in China (website: www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn), which is run by the Centre for Drug Evaluation, National Medical Products Administration. This would limit the comprehensive understanding of clinical trials in China.

Data comparison between the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) official website and ICTRP registration data revealed several inconsistencies, including redundant entries, missing entries, inconsistent registration status and incomplete countries of recruitment, but the comparison was only conducted for the ChiCTR and not for the other 17 primary registries.

Introduction

Clinical research describes many different elements of scientific investigation involving human subjects, including patient-oriented research, epidemiological and behavioural research, outcome research and health services research.1 There are two main types of clinical studies: clinical trials (also called interventional studies) and observational studies. Clinical trial registration is one of the most important changes in the field of clinical research. It is crucial for research transparency and for minimising bias and selective reporting as well as publicly demonstrating ongoing research to guide valuable research funding and efforts when needed.2 3 In 1970, the USA formally proposed the concept of clinical trial registration to reduce the publication bias of clinical trial results.4 In 1977, the American Cancer Institute launched the world’s first clinical trial registry, the Cancer Clinical Trial Registry. In February 2000, ClinicalTrials.gov was launched by the US FDA, the National Institutes of Health and the National Library of Medicine, and that in the same year the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) was launched in the UK. The next major move forward took place in 2004, following the case of New York against Glaxo, which inspired the Clinical Trial Registration Statement by the International Council of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE),2 followed by the Ottawa statement5 and the development of international standards for trial registration by the WHO.6 Subsequently, Australia, China, Japan, the Netherlands, Germany, Iran, Sri Lanka, South Korea and other countries launched clinical trial registration platforms. In 2007, the WHO International Clinical Trial Research Platform (ICTRP) was launched to provide a searchable database containing the trial registration data sets provided by source registries around the world. An increasing number of clinical trials have been registered on ICTRP source registries worldwide7 and clinical trial registries gradually started registering observational studies.8 As of January 2017, ICTRP had included more than 340 000 clinical studies in over 175 countries.9 There were more than 33 000 studies with China as the recruitment location.10 Over 20 000 studies registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) as of December 2018.11 In those cases, China’s institutions may play a leading role as primary sponsors, a collaborative role as secondary sponsors or as participants as one of recruitment countries. The primary sponsor is the individual, organisation, group or other legal person responsible for securing the arrangements to initiate and/or manage a study.12 No previous studies have focused on registered clinical studies primarily sponsored by China’s institutions on multiple registries, which can directly reflect the trial registration activity of China. Previous studies on clinical study registration mostly focused on one clinical trial registry as a whole7 12–15 or classified trials by countries or regions of recruitment,16–18 rather than differentiating study sponsors by their source countries, which is not a direct data field in most registries. Given that the construction of the national clinical medical research system has become a key task of base construction during the 13th 5-year plan period,19 more information regarding the current clinical trial registration activity in China is warranted. This work describes the characteristics and trends of registered clinical studies primarily sponsored by China’s institutions, and global registrations were also summarised for comparison to provide global insights into the trial registration activity of China over the studied decade.

Methods

Data collection and identification

Both clinical trials (also called interventional studies) and observational studies are included for analysis in this study. Registration data in XML format were downloaded from ICTRP20 and converted to Excel format. Based on preliminary investigations and other studies,21 the studies primarily sponsored by China are mainly registered on ChiCTR, ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN register and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR). We also downloaded complete data from the websites of these four registries, including the data set from the ISRCTN and ANZCTR websites, and the Static Copy of the Aggregate Analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov database provided by the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/aact-database).22 ChiCTR does not provide data sets for download, so the ChiCTR registration data from the ICTRP were compared and subjected with the retrieval results on the ChiCTR website.

The studies primarily sponsored by institutions in mainland China (not including institutions from Hong Kong SAR of China, Macau SAR of China or Taiwan of China) were extracted from source data according to the data field of the primary sponsor by using the advanced filter tool in Excel combined with manual data filtering. A list of keywords, including the China’s administrative division, government agencies, hospitals, universities and colleges, enterprises, foundations, non-profit organisations and Chinese surnames, was collected from the internet. The process of filtering adopted the principle of a broad match to an exact match. Rough filtering was conducted first to avoid missing data. Then, the retrieved items were checked for accuracy. The counting data are expressed as numbers and percentages and were processed by Microsoft Excel 2017.

Filtering and removal of duplicate registrations

Some studies were registered on multiple registries and hence may appear on more than one registry.23 The ICTRP has bridged (grouped together) multiple records for the same trial to facilitate the unique identification of trials. We initially found that quite a few duplicate registrations had not been bridged. Therefore, duplicate registration removal was only conducted on China-sponsored studies. For data sets downloaded from the websites of source registries, other study IDs, which were displayed as ‘ID value’ on ClinicalTrials.gov, ‘ClinicalTrials.gov number’ on ISRCTN, ‘secondary ID’ on ANZCTR and ‘The registration number of the Partner Registry or other register’ on ChiCTR, provide clues for duplicate registrations. For duplicate records, only the record with the earliest registration date was considered eligible.

Quality control

The investigators were trained with the protocol we produced before starting this study. Two investigators (YX and MD) independently identified the studies sponsored by China’s institutions and a third investigator (XL) adjudicated any disagreement. According to the results of the discussion, we revised the protocol. After the data extraction, another investigator will check the data to ensure accuracy.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this study.

Results

Registration activity

Number of studies

We identified 478 261 global registrations as of 31 December 2018, in which 32 557 registrations were primarily sponsored by China’s institutions (table 1). Fifty-two studies sponsored by China were registered on both ChiCTR and ClinicalTrials.gov, 5 studies on both ClinicalTrials.gov and ISRCTN, 2 studies on both ChiCTR and ISRCTN, and 1 study on both ANZCTR and ChiCTR. The registration entries with the later registration date were excluded from the analysis of studies sponsored by China.

Table 1.

Number of registered clinical studies sponsored by China and the distribution on ICTRP source registries as of December 2018

| Source registries | Source of data | Number of registered studies | Number of registered studies sponsored by China |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | AACT | 292 582 | 12 628 |

| Japan Primary Registries Network | ICTRP | 37 801 | 39 |

| EU Clinical Trials Register | ICTRP | 29 798 | 22 |

| ChiCTR | ICTRP and ChiCTR | 20 022 | 19 483 |

| Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) | ICTRP | 19 104 | 0 |

| ISRCTN | ISRCTN | 17 689 | 226 |

| ANZCTR | ANZCTR | 16 846 | 128 |

| Clinical Trials Registry—India | ICTRP | 16 653 | 10 |

| German Clinical Trials Register | ICTRP | 7621 | 1 |

| The Netherlands National Trial Register | ICTRP | 7429 | 2 |

| Clinical Research Information Service Republic of Korea | ICTRP | 3379 | 0 |

| Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry | ICTRP | 2650 | 0 |

| Thai Clinical Trials Registry | ICTRP | 2578 | 18 |

| Peruvian Clinical Trial Registry | ICTRP | 1761 | 0 |

| Pan African Clinical Trial Registry | ICTRP | 1756 | 0 |

| Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials | ICTRP | 295 | 0 |

| Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry | ICTRP | 295 | 0 |

| Lebanese Clinical Trials Registry | ICTRP | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 478 261 | 32 557 |

Data note: Exact registration year was not available in 96 entries on IRCT, so these entries were excluded from the analysis.

AACT, aggregate analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov; ANZCTR, Australian New Zealand clinical trials registry; ChiCTR, Chinese Clinical Trial Registry; ICTRP, International clinical trials registry platform; ISRCTN, International standard randomised controlled trial number.

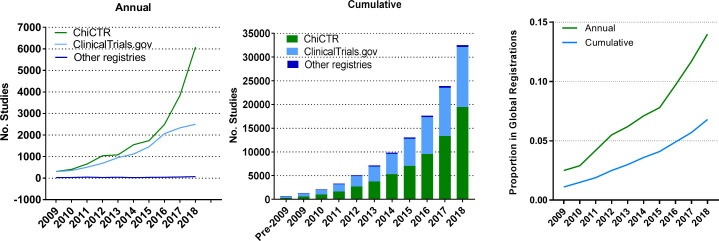

The cumulative registered studies sponsored by China have increased from 1330 in 2009 to 32 515 in 2018, accounting for 1% of global registrations in 2009 to 7% in 2018 (table 2). The majority of studies was registered on ChiCTR (19 483 trials or 60%) and ClinicalTrials.gov (12 628 trials or 39%). The average annual growth rate of studies registered from 2009 to 2018 for China was 34%, much higher than the growth rate of 11% for global registrations (figure 1).

Table 2.

Number of registered clinical studies worldwide and those sponsored by China, annually and cumulatively to December 2018

| Year | Annual registrations sponsored by China | Global annual registrations | Cumulative registrations sponsored by China | Global cumulative registrations | ||||||

| ChiCTR | ClinicalTrials.gov | Other registries | Total | ChiCTR | ClinicalTrials.gov | Other registries | Total | |||

| Pre-2009 | 306 | 348 | 50 | 704 | 91 384 | 306 | 348 | 50 | 704 | 91 384 |

| 2009 | 304 | 303 | 22 | 629 | 24 843 | 610 | 651 | 72 | 1333 | 116 227 |

| 2010 | 404 | 352 | 30 | 786 | 26 886 | 1014 | 1003 | 102 | 2119 | 143 113 |

| 2011 | 655 | 504 | 46 | 1205 | 28 234 | 1669 | 1507 | 148 | 3324 | 171 347 |

| 2012 | 1035 | 693 | 30 | 1758 | 32 148 | 2704 | 2200 | 178 | 5082 | 203 495 |

| 2013 | 1078 | 955 | 44 | 2077 | 33 550 | 3782 | 3155 | 222 | 7159 | 237 045 |

| 2014 | 1548 | 1118 | 22 | 2688 | 37 898 | 5330 | 4273 | 244 | 9847 | 274 943 |

| 2015 | 1742 | 1456 | 35 | 3233 | 41 215 | 7072 | 5729 | 279 | 13 080 | 316 158 |

| 2016 | 2489 | 2063 | 44 | 4596 | 47 412 | 9561 | 7792 | 323 | 17 676 | 363 570 |

| 2017 | 3835 | 2331 | 53 | 6219 | 53 061 | 13 396 | 10 123 | 376 | 23 895 | 416 631 |

| 2018 | 6087 | 2505 | 70 | 8662 | 61 630 | 19 483 | 12 628 | 446 | 32 557 | 478 261 |

| Total | Registrations by China 2009–2018 | 478 261 | Proportion of registrations by China | 100% | ||||||

| 19 177 | 12 280 | 396 | 31 853 | 60% | 39% | 1% | 478 261 | |||

Data note: In the 20 405 ChiCTR-retrieved registration entries on ICTRP up to 2018, 372 redundant entries and 413 missing entries were found when compared with the retrieval results on the ChiCTR website. The redundant entries were deleted, and the missing entries were supplemented by individual records from the ChiCTR website. Furthermore, there were 29 registration entries with the wrong registration year in 1990 and one registered study with the wrong registration date beyond the actual date. The registration year was determined according to ‘Study Execute Time’, ‘Date of Last Refreshed on’ and ‘Registration Status’. The static copy of the AACT database for ClinicalTrials.gov was downloaded, and the registration date was based on the data field of the ‘study first posted date’. After removing 811 trials with a study title of ‘trials of device that is not approved or cleared by the US FDA’, 292 582 studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov up to 2018 were included. Duplicate registration entries were only excluded for registrations primarily sponsored by China.

ChiCTR, Chinese Clinical Trial Registry; ISRCTN, International standard randomised controlled trial number.

Figure 1.

Number of registered clinical studies sponsored by China, annually and cumulatively, and their proportion in global registrations, 2009–2018. ChiCTR, Chinese Clinical Trial Registry.

Distribution of countries or regions of recruitment

Table 3 shows the distribution of countries or regions of recruitment per year of registered studies worldwide and those sponsored by China up to 2018. Multiregional clinical trials (MRCTs) were trials with more than one country/region of recruitment. There were 122 MRCTs, of which 69 trials (57%) recruited in two countries/regions, 23 trials (19%) recruited in three to five countries/regions and 29 trials (25%) recruited in more than five countries/regions, accounting for 0.4% of the registered studies sponsored by China. After China, the USA was the second most commonly cited country/region of recruitment for the registered trials sponsored by China, followed by Australia, Germany and Taiwan (a province of China). For registered global MRCTs, 42% had recruited in more than five countries/regions; the top five recruitment countries/regions for registered global MRCTs were the USA, Germany, the UK, Spain and France; China ranked 40th by number of registered trials (table 4).

Table 3.

Distribution of countries or regions of recruitment per study for registered studies sponsored by China and global registrations up to 2018

| Year | China (N=32 557) | Global (N=450 194) | ||

| One country/region | MRCTs | One country/region | MRCTs | |

| Pre-2009 | 700 | 4 | 72 400 | 13 527 |

| 2009 | 626 | 4 | 20 673 | 2934 |

| 2010 | 785 | 3 | 22 736 | 2956 |

| 2011 | 1199 | 1 | 24 098 | 3012 |

| 2012 | 1755 | 6 | 27 919 | 3224 |

| 2013 | 2072 | 3 | 29 750 | 2841 |

| 2014 | 2675 | 5 | 32 649 | 3107 |

| 2015 | 3220 | 13 | 34 842 | 3238 |

| 2016 | 4584 | 13 | 40 302 | 3162 |

| 2017 | 6198 | 12 | 46 287 | 2999 |

| 2018 | 8621 | 21 | 54 637 | 2901 |

| TOTAL (n/%) | 32 435 (99.6) | 122 (0.4) | 406 293 (90) | 43 901 (10) |

| Trials | Recruitment countries or regions per trial of MRCTs (n/%) | |||

| Two countries/regions | 3–5 | 6–10 | >11 | |

| China | 69 (57) | 23 (19) | 15 (12) | 15 (12) |

| Global | 12 804 (29) | 12 722 (29) | 9239 (21) | 9136 (21) |

Data note: There were 1932 registered studies sponsored by China with absent recruitment countries/regions data, and the recruitment country/region was assigned to China after manual verification. Another 28 067 registration entries with absent recruitment countries/regions data were excluded from the analysis because the missing recruitment countries/regions could not be determined manually. In addition, 407 registration entries on Japan Primary Registries Network only specified the continents of recruitment. The number of recruitment continents was used to represent the number of recruitment countries or regions in these entries.

MRCTs, multiregional clinical trials.

Table 4.

Top 10 recruitment countries/regions for registered studies sponsored by China, global studies and global MRCTs, by number of studies as of December 2018

| Rank | Studies sponsored by China | Global studies | Global MRCTs | |||

| Country/region | Number | Country/region | Number | Country/region | Number | |

| 1 | Mainland China | 32 369 | USA | 128 857 | USA | 22 563 |

| 2 | USA | 125 | Japan | 42 247 | Germany | 19 972 |

| 3 | Australia | 60 | Germany | 37 886 | UK | 15 672 |

| 4 | Germany | 35 | Mainland China | 36 657 | Spain | 14 853 |

| 5 | Taiwan, China | 30 | UK | 35 963 | France | 13 915 |

| 6 | Spain | 28 | France | 29 649 | Italy | 13 829 |

| 7 | Italy | 26 | Canada | 25 348 | Canada | 13 573 |

| 8 | France | 24 | Netherlands | 23 682 | Belgium | 10 691 |

| 9 | Japan | 24 | Australia | 22 263 | Poland | 9740 |

| 10 | UK | 21 | Spain | 21 884 | Netherlands | 9480 |

| … | … | … | … | … | ||

| 40 | … | … | Mainland China | 2422 | ||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

Data note: There were 1932 registered studies sponsored by China with absent recruitment countries/regions data, and the recruitment country/region was assigned to China after manual verification. Another 28 067 registration entries with absent recruitment countries/regions data were excluded from the analysis because the missing recruitment countries/regions could not be determined manually. In addition, 407 registration entries on JapanPrimary Registries Network only specified the continents of recruitment. The number of recruitment continents was used to represent the number of recruitment countries or regions in these entries.

MRCTs, multiregional clinical trials.

Industry involvement—sponsor type and funding type

Sponsor type or funding type can be divided into non-industrial institutions and industrial institutions. Non-industrial institutions usually include government bodies, hospitals, universities, charities/societies/foundations, individuals and other collaborative groups. Industrial institutions include China-based industry and global industry. All trials were mapped based on having industry involvement or not having industry involvement, which was derived from sponsor type and funding type. Over the decade analysed, 14% of the registered studies sponsored by China had some industry involvement, either as funding source, primary sponsor or secondary sponsor, below the average level of industry-related global registrations (30%). The proportion of industry involvement of the registered studies sponsored by China remained relatively stable and varied between 13% and 20%. For global registrations, there was an obvious downward trend in the proportion of industry involvement, from 39% in 2009 to 21% in 2018 (table 5).

Table 5.

Number and proportion of clinical studies registered each year with or without industry involvement, for the registered studies sponsored by China and the global registrations, up to 2018

| Year | Global (n/%) | China (n/%) | ||

| Industry | Non-industry | Industry | Non-industry | |

| Pre-2009 | 36 977 (40) | 54 382 (60) | 109 (15) | 595 (85) |

| 2009 | 9798 (39) | 15 034 (61) | 98 (15) | 531 (84) |

| 2010 | 9943 (37) | 16 931 (63) | 158 (20) | 628 (80) |

| 2011 | 9843 (35) | 18 379 (65) | 190 (16) | 1015 (84) |

| 2012 | 10 298 (32) | 21 836 (68) | 277 (16) | 1481 (84) |

| 2013 | 9407 (28) | 24 126 (72) | 304 (15) | 1773 (85) |

| 2014 | 11 259 (30) | 26 628 (70) | 369 (14) | 2319 (86) |

| 2015 | 11 080 (27) | 30 128 (73) | 478 (15) | 2755 (85) |

| 2016 | 11 367 (24) | 36 040 (76) | 580 (13) | 4019 (87) |

| 2017 | 11 631 (22) | 41 422 (78) | 790 (13) | 5426 (87) |

| 2018 | 12 755 (21) | 48 865 (79) | 1106 (13) | 7556 (87) |

| Total | 144 358 (30) | 333 771 (70) | 4459 (14) | 28 098 (86) |

Data note: Industry involvement was determined according to sponsor type and funding type from the official website of each registry. The ClinicalTrials.gov, Japan Primary Registries Network, EU Clinical Trials Register, Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, AustralianNew Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, InternationalStandard Randomised Controlled Trial Number, Clinical Trials Registry—India, German Clinical Trials Register and ReBec databases used several categories for sponsor type and funding type, and all these categories had been mapped to industry or non-industry. When the sponsor type and funding type could not be directly obtained from official websites, the type was manually determined according to the primary sponsor name and source support name. 132 entries with absent ‘primary sponsor’ and ‘source support’ values were excluded from the analysis for industry involvement.

Clinical study focus

Health conditions studied

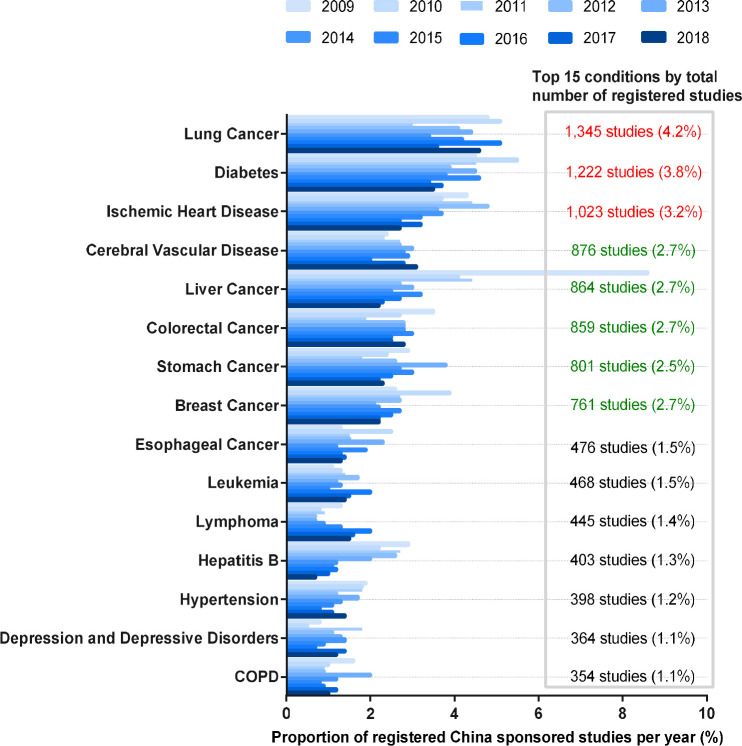

Registered clinical studies sponsored by China have covered a wide range of health conditions. As multiple condition codes could be selected for each trial, the total number of studies selecting each condition was more than the total number of registered studies. Lung cancer was the most commonly targeted health condition, with 1346 studies (4.2%) registered from 2009 to 2018, followed by diabetes (1223 trials or 3.8%) and ischaemic heart disease (1023 trials or 3.2%). Depression and depressive disorders and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were each represented by 1.1% of the registered China sponsored studies (figure 2). As the total number of registrations increased, the studies targeting some specific diseases showed a downward trend as a proportion of clinical studies registered each year despite a rapidly growing absolute number. In the top 15 most studied conditions, as a proportion of clinical studies registered each year from 2009 to 2018 sponsored by China, those investigating diabetes, ischaemic heart disease and hypertension had slightly decreased proportions, and those investigating liver cancer and hepatitis B had noticeably decreased proportions, with diabetes dropping from 4.5% to 3.5%, ischaemic heart disease from 4.3% to 2.7%, hypertension from 1.9% to 1.4%, liver cancer from 8.6% to 2.2% and hepatitis B from 2.9% to 0.7%.

Figure 2.

Top 15 conditions by the number of registered studies sponsored by China and their trends by proportion of registrations per year, 2009–2018 (N=31 853). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

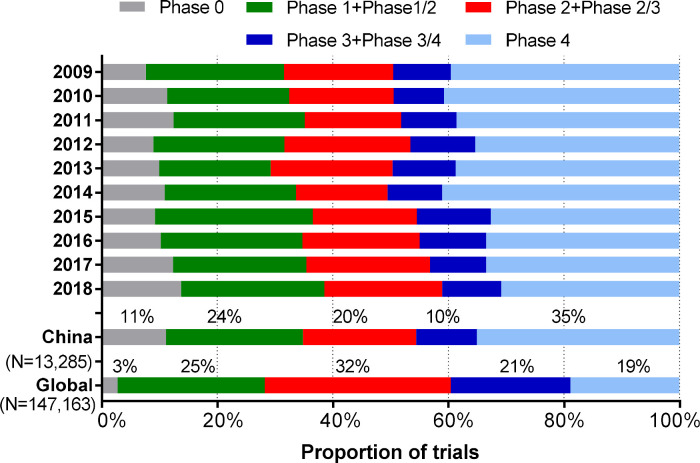

Phase of trials

In 31 853 studies sponsored by China registered 2009–2018, 13 285 trials had their ‘study phase’ field specified as phase 0 to phase 4. Phase 4 trials were most common among all registered trials (35%), followed by phase 1 trials (including phase 1/2 trials, 24%), phase 2 trials (including phase 2/3 trials, 20%), phase 0 trials (11%) and phase 3 trials (including phase 3/4 trials, 10%). For global registrations, the trials in phase 2 and phase 3 together accounted for 53%, which was obviously higher than that proportion in the registered trials sponsored by China (30%) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trends in the study phase for registered China sponsored trials and global registrations with study phase specified, 2009–2018.

Registration status and plan to share IPD

Prospective versus retrospective registration

If registration occurs prior to or coincides with the start date, the study is labelled prospectively registered; otherwise, it is labelled retrospectively registered. In 30 047 registered studies sponsored by China 2009–2018 with registration status available, compliance with prospective registration was 38% in 2009, fell slightly in 2011 (32%) and 2012 (36%), increased to 56% in 2013 and had since steadily increased and peaked to 72% in 2018. Overall, 63% of studies were registered prospectively for registered studies sponsored by China, higher than the prospective registration proportion of 45% for global registrations (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proportion of prospective versus retrospective registrations for registered studies sponsored by China and global registrations, 2009–2018. Data note: this section used direct data on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, Aggregate Analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number and registration data from International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. ClinicalTrials.gov did not provide direct data of ‘registration status’, whereas the fields of ‘study first posted date’ and ‘start date’ could be adopted for an equivalent analysis. On ClinicalTrials.gov, some registrations were excluded because their ‘start date’ was shown in a ‘month-year’ format and could not be analysed for registration status. The total number of studies with specified registration status 2009–2018 was 238 981.

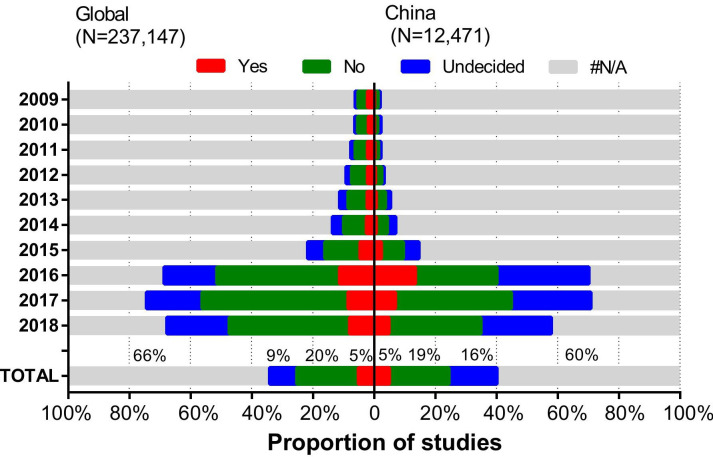

Plan to share individual participant data

Individual participant data (IPD) refers to the measurement data collected from each clinical trial participant, which is different from the summary data usually reported in journal articles or in the trial registry result database. IPD from completed clinical trials should be responsibly shared to support efficient clinical research, generate new knowledge and benefit patients.24 For global registrations, the proportion of studies responding to IPD sharing plans was low between 2009 and 2015 and had risen sharply to 70% since 2016, maintained at 71% in 2017 and then declined to 58% in 2018 (figure 5). Despite the sharp increase in the response rate, the proportion of indicating ‘yes’ to IPD sharing plans is still low, generally accounting for 5% of the registered studies sponsored by China and global registrations, respectively. A large proportion of studies had indicated ‘no’ or ‘undecided’ to IPD sharing plans (35% for the registered studies sponsored by China and 29% for global registrations, respectively).

Figure 5.

Trends in the proportion of trials with IPD sharing plans for the registered studies sponsored by China and global registrations, 2009–2018. Data note: this section used data on studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and ISRCTN. Although the IPD sharing plan was an option on ChiCTR, it could not be retrieved on the website. ANZCTR and other registries from ICTRP do not provide information on IPD sharing plan. Thus, the equivalent analysis was not conducted for ANZCTR, ChiCTR or ICTRP. ANZCTR, Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; ChiCTR, Chinese Clinical Trial Registry; ICTRP, InternationalClinical Trials Registry Platform; IPD, individual participant data; ISRCTN, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number.

Discussion

Increasingly, numerous researchers, hospital ethics committees and foundations have attached great importance to medical research ethics and the transparency of clinical trials in China. Registration in a publicly accessible and web-based searchable registry is the first step in clinical trial transparency. This analysis provided the first landscape of clinical study registration primarily sponsored by China’s institutions in a global context helped to better understanding of the current state of clinical study registration and provided insights into future developments. As shown in this review, several interesting trends and noteworthy observations have emerged in the past decade.

Registration activity

Clinical study registration by China’s institutions began in 2005, with just 18 studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and ISRCTN in the first year. ChiCTR was launched by the Chinese Cochrane Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University in 2004 and officially accepted clinical study registration in 2005. ChiCTR was assigned to be the representative registry of China to join the WHO Registry Network in 2007 and significantly promoted clinical study registration in China.25 26 After more than 10 years of development, the number of registered studies sponsored by China reached a cumulative number of 32 557 as of December 2018, accounting for 7% of global registrations. The average annual growth rate from 2009 to 2018 of registered studies sponsored by China was much higher than that for the global registrations in the same period (34% vs 11%).

We found that the proportion of registered studies sponsored by China with industry involvement was lower compared with those without industry involvement (14% vs 86%). This is not surprising considering the resistance of industry to trial registration details, as discussed in an earlier study.27 The reason may also relate to other platforms for clinical trial registration (eg, for the pharmaceutical industry). As for clinical drug trials for new drug applications, sponsored or funded by pharmaceutical enterprises and conduced in China, compulsory registration and publicise information are required on the Platform for Registry and Publicity of Drug Clinical Trials in China (website: www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn, abbreviated as ChinaDrugTrials.org), run by the Centre for Drug Evaluation, National Medical Products Administration. A total of 7345 industry-funded drug trials were registered on ChinaDrugTrials.org as of December 2018, in which 75 trials were registered simultaneously on ICTRP source registries. Thus, this study mainly reflected the situation of registered studies funded by China’s non-commercial institutions. It was suggested that data exchange and mutual recognition should be carried out between ChinaDrugTrials.org and ChiCTR to promote the transparency and sharing of clinical trial information.28

Only a small proportion of registered trials sponsored by China recruited participants from more than one country/region (122 trials or 0.4%). The number of registered MRCTs with China as one of the recruitment countries reached 2422 in 2018, with transnational pharmaceutical companies as the main sponsors.29 The huge gap demonstrated good international participation of China’s institutions with MRCTs but a lack of leadership. As the largest developing country and the largest patient resource country, China plays an important strategic role in the global pharmaceutical research and development market but is still located downstream and lacks high-quality and systematic clinical medicine research and research results with global influence.30 Research capabilities can be objectively assessed based on four indicators: number of interventional clinical trials, number of phase 1 clinical trials, number of phase 2 and phase 3 MRCTs and number of papers published in leading clinical research journals.31 Unlike the majority of phase 2 and phase 3 trials, with 53% of global registrations, 68% of Australian clinical trials16 and 73% of New Zealand clinical trials,17 phase 2 and phase 3 trials accounted for 30% of the registered trials sponsored by China. China currently ranks number 9, behind Japan and Korea in Asia, among leading drug innovation countries in terms of clinical research capabilities.31 In recent years, China has strengthened independent innovation in traditional chemical pharmaceuticals and in new fields such as biopharmaceutics, precision medicine and intelligent medicine,32 which will promote China’s leadership in high-quality clinical trials in the future.

Clinical study focus

In China, among the top 10 causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2017, eight non-communicable diseases ranked high to low by DALYs were stroke, ischaemic heart disease, COPD, lung cancer, liver cancer, diabetes, neck pain and depressive disorders, respectively; by per cent changes of DALYs from 2007 to 2017, lung cancer, ischaemic heart disease and stroke ranked top 3.33 There has been more activity in the diseases of greatest burden and per cent change of DALYs, with the most common targeted conditions being lung cancer, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, cerebral vascular disease and liver cancer; these conditions represented 4.2%, 3.8%, 3.2%, 2.8% and 2.8%, respectively, of all registered studies sponsored by China. However, some diseases with a high disease burden, such as depression and depressive disorders, COPD and neck pain, remain underrepresented, ranking 14th, 15th and below the top 25, respectively, by the number of registered trials. This is partly related to the limited availability of potential effective interventions assessed in the trials. These conditions may also warrant more research in the future.

For many serious diseases (such as liver cancer, stomach cancer, oesophageal cancer and hepatitis B) with high prevalence in China, there is a lack of therapeutic innovation worldwide. Therefore, it is even more necessary for medical workers to explore solutions by means of clinical research in China.31 Endemic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a particularly serious public health problem in China. The number of studies focusing on HBV infection ranked 12th, with 403 studies registered, and has been trending downward noticeably as a proportion of the clinical studies registered each year, from 2.9% in 2009 to 0.7% in 2018. A report in 2018 indicated that the efforts to address other HBV-related problems lagged behind the HBV immunisation programme; hence, the hepatitis B epidemic in China should receive more attention.34 According to the 5-year Development Plan on National Centres for Clinical Medicine Research (2017–2021), two national clinical research centres for viral hepatitis were approved on May 2019.35 These centres will greatly promote the clinical research of viral hepatitis.

Registration status and plan to share IPD

Prospective registration is an important part of the transparency of clinical trials.36 37 ICMJE issued a statement requiring the prospective registration of clinical trials as a condition for publication in a biomedical journal since 2007.38 Sixty-three per cent of the registered studies sponsored by China were registered prospectively, which was above the global level (45%) and close to the New Zealand clinical trials (69%) and Australian clinical trials (60%),16 17 indicating that researchers’ awareness of clinical study registration had gradually improved in China. Funding agencies can adopt clear policies to improve transparency and prevent publication bias.39 40 Compliance with prospective registration is expected to be further improved based on the ethical requirement to prospectively register all clinical studies by the state and research institutions.

The ICMJE issued an initiative on the IPD sharing plan in clinical trials on 20 January 2016, requiring the IPD sharing plan be stated when registering clinical trials from 2019.24 Sharing IPD is becoming broadly accepted as the new standard in clinical trial transparency.39 41 Accordingly, there had been a dramatic increase in the proportion and number of registered studies sponsored by China responding to the IPD sharing plan since 2016, but it decreased to 58% in 2018. This decrease is probably related to the majority of China-sponsored studies that were registered on ChiCTR, where the statement of the IPD sharing plan had been implemented since March 2016 but with related data that could not be retrieved. Only 5% of the registered studies indicated ‘yes’ to an IPD sharing plan, both for the registered studies sponsored by China and global registrations. Even in the highest sharing year of 2016, the proportion of willingness to share IPD data was just 13% and 11%. It was obviously lower than the proportion of 86% revealed by a survey, which randomly sampled 457 studies registered in 2016 on ChiCTR and downloaded the research plan for analysis.42 Although the researchers are willing to share the original data of their research, the accessibility of participant-level data is still a challenge.42 Only 28% of the studies described a correct data management system, and 67% of the researchers may not know that clinical studies should adopt professional and standard data management systems to manage their data.42 These findings highlight the need for more education, sufficient information and flawless technical support for IPD sharing plans.43

Registration quality

Better quality checks should be implemented on the data entered into the registry as there are often inadequacies and internal inconsistencies, such as a wrong registration date on the ChiCTR, unavailable or inexact ‘start date’ unable to be used for registration status judgement (prospective or retrospective) on ClinicalTrials.gov and internal inconsistencies in the registration status fields. ChiCTR registration data were downloaded from ICTRP and compared with retrieval results on the ChiCTR website, providing an opportunity to compare registration records from both sources. There are 372 redundant entries and 413 missing entries on ICTRP up to 2018. A total of 1594 trials with registration status shown on ICTRP were not consistent, and 3245 records with registration status derived from ‘date_registration’ and ‘date_enrollment’ on the ICTRP registration data were not consistent with the retrieval results on ChiCTR. Furthermore, recruitment countries/regions were not completely listed in 29 registered studies on ICTRP data sets. The reasons for these missing data and inconsistencies are not clear and need further study. These deficiencies in key areas of registered records undermined the potential benefits of trial registration and raised concerns that stricter quality control should be implemented for registration.44

Limitations

The number of clinical studies included in the study is very large, which can offset the bias caused by a single data source to some extent. However, some limitations should be considered in interpreting the findings. First, we only recruited ICTRP source registries and did not include trials registered on ChinaDrugTrials.org. This would limit the level of comprehensive understanding of clinical studies in China, especially those trials for new drug applications sponsored by industry. Second, the registration of clinical studies on ICTRP source registries in China is not compulsory at present.39 Therefore, the results of this study can only encompass the current registered clinical studies but cannot reflect the unregistered studies or accurately represent the overall level of relevant clinical studies in China.

Conclusions

Clinical study registration activity in China has been substantial during the decade of 2009–2018. Prospective registration has accounted for over half of the studies sponsored by China registered each year since 2013 and has continued to rise in recent years. Some diseases with a high disease burden in China, such as depression and depressive disorders and COPD, are underrepresented by the registered studies. Some serious diseases, such as liver cancer, stomach cancer, oesophageal cancer and hepatitis B, with high prevalence in China, have obviously decreased as a proportion of clinical studies registered each year and should receive more attention. The low number of registered MRCTs and low proportion of registered phase 2 and phase 3 trials might indicate inadequate innovation in clinical studies. Despite the sharp increase in studies responding to IPD sharing plans since 2016, the proportion of studies indicating ‘yes’ for IPD sharing did not increase noticeably. The accessibility of participant-level data of registered studies needs improvement both in China and worldwide. Furthermore, comparisons of data in ICTRP and WHO primary registries are needed to learn about eventual discrepancies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: XL and YX had the original idea for the study. YX devised the protocol. YX and MD collected and analysed the data; YX wrote the first draft of this manuscript. XL helped to refine the protocol and provide guidance on what data to collect. MD was involved in preparing the manuscript for submission. All authors read and approved the final submission.

Funding: This work was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020JDR0100).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Source data can be requested from the corresponding author at liuxuemei@wchscu.cn.

References

- 1.US National Library of Medicine Learn about clinical studies, 2019. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/about-studies/learn

- 2.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International committee of medical Journal editors. Lancet 2004;364:911–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17034-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickersin K, Rennie D. Registering clinical trials. JAMA 2003;290:516–23. 10.1001/jama.290.4.516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simes RJ. Publication bias: the case for an international registry of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 1986;4:1529–41. 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.10.1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krleza-Jerić K, Chan A-W, Dickersin K, et al. Principles for international registration of protocol information and results from human trials of health related interventions: ottawa statement (part 1). BMJ 2005;330:956–8. 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drazen JM, Wood AJJ. Trial registration report card. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2809–11. 10.1056/NEJMe058279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viergever RF, Li K. Trends in global clinical trial registration: an analysis of numbers of registered clinical trials in different parts of the world from 2004 to 2013. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008932. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RJ, Tse T, Harlan WR, et al. Registration of observational studies: is it time? CMAJ 2010;182:1638–42. 10.1503/cmaj.092252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Vello P, Smith E, Elias V, et al. Adherence to clinical trial registration in countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, 2015. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2018;42:e44:1–9. 10.26633/RPSP.2018.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO List by countries, 2019. Available: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ListBy.aspx?TypeListing=1

- 11.CHICTR Trial search, 2019. Available: http://www.chictr.org.cn

- 12.ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol registration data element definitions for interventional and observational studies, 2019. Available: https://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/definitions.html

- 13.Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, et al. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007-2010. JAMA 2012;307:1838–47. 10.1001/jama.2012.3424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TX W, Abudu M, Hao Y, et al. The past 10 years of clinical registration in China: status and challenge. Chin J Evid-based Med 2018;18:522–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarin DA, Tse T, Ide NC. Trial registration at ClinicalTrials.gov between may and October 2005. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2779–87. 10.1056/NEJMsa053234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Askie LM, Hunter KE, Berber S, et al. The clinical trials landscape in Australia 2006–2015. Sydney: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, 2017. http://www.anzctr.org.au/docs/ClinicalTrialsInAustralia2006-2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter KE, Seidler AL, Barba A, et al. The clinical trials landscape in New Zealand 2006–2015. Sydney: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, 2018. http://www.anzctr.org.au/docs/NZ_Report_2006-2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeeneldin AA, Taha FM. The Egyptian clinical trials’ registry profile: analysis of three trial registries (International clinical trials registry platform, Pan-African clinical trials registry and ClinicalTrials.gov). J Adv Res 2016;7:37–45. 10.1016/j.jare.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.General Office of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China Special plan for innovation of health and health science and technology in the 13th five-year plan, 2019. Available: http://www.most.gov.cn/tztg/201706/W020170613318790155749.docx

- 20.World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Who trial registration data set (version 1.3.1), 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/ictrp/network/trds/en/

- 21.Wu L, Tian GX, Wang XH, et al. Comparative analysis of clinical trial registration and registry platforms. Chin J Evid Based Carduivasc Med 2017;9:129–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative Download static copy of the database, 2019. Available: https://aact.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/static/exported_files/monthly/20190101_pipe-delimited-export.zip

- 23.WHO Linking related records on the ICTRP search portal, 2019. Available: http://www.who.int/ictrp/unambiguous_identification/bridging/en/index.html

- 24.Taichman DB, Sahni P, Pinborg A, et al. Data sharing statements for clinical trials: a requirement of the International Committee of medical Journal editors. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002315. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.TX W, YP L, Yao X, et al. Clinical trial registration: to improve the quality of clinical research in China. Chin J Evid-based Med 2006;6:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams M. Chinese research register joins who network, raising hopes for improved clinical trials. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:653–4. 10.2471/blt.07.010907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krleza-Jerić K. Clinical trial registration: the differing views of industry, the who, and the Ottawa group. PLoS Med 2005;2:e378. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zong X, Dong JP, Tao XM. Suggestions for clinical trial registration and information sharing in China. Chin J New Drugs 2015;24:2410–3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun M, Zhang CY, Chen YW. Analysis of the situation of international multi-center clinical trials in China. Chin J New Drugs 2016;25:1737–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.LM L, Zhang YQ, Guyatt G, et al. How to fulfil China’s potential for carrying out clinical trials. BMJ Chin Edition 2018;21:699–700. [Google Scholar]

- 31.China Association of Enterprises with Foreign Investment R&D-based Pharmaceutical Association Committee Deepening the drug innovation ecosystem reform–A plan to design and build China’s clinical research system, 2019. Available: http://enadmin.rdpac.org/upload/upload_file/1575474867.pdf

- 32.Yang ZZ, Sun YS, Wei LJ, et al. An overview of category 1 new drugs self-developed and Approved in China from 2014 to 2018. Chin J New Drugs 2019;28:1537–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.IHME China | Institute for health metrics and evaluation, 2019. Available: http://www.healthdata.org/china

- 34.Chen S, Li J, Wang D, et al. The hepatitis B epidemic in China should receive more attention. Lancet 2018;391:1572. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30499-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China List of supporting institutions of the fourth batch of national centers for clinical medicine research, 2019. Available: http://www.most.gov.cn/tztg/201905/t20190530_146874.htm

- 36.Harriman SL, Patel J. When are clinical trials registered? an analysis of prospective versus retrospective registration. Trials 2016;17:187. 10.1186/s13063-016-1310-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gopal AD, Wallach JD, Aminawung JA, et al. Adherence to the international committee of medical journal editors’ (ICMJE) prospective registration policy and implications for outcome integrity: a cross-sectional analysis of trials published in high-impact specialty society journals. Trials 2018;19:448–60. 10.1186/s13063-018-2825-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International committee of medical journal editors. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1250–1. 10.1056/NEJMe048225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moher D, Glasziou P, Chalmers I, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research: who's listening? Lancet 2016;387:1573–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00307-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeVito NJ, French L, Goldacre B. Noncommercial Funders' policies on trial registration, access to summary results, and individual patient data availability. JAMA 2018;319:1721–3. 10.1001/jama.2018.2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization Joint statement on public disclosure of results from clinical trials, 2019. Available: http://www.who.int/ictrp/results/ICTRP_JointStatement_2017.pdf

- 42.TX W, Abudu M, Bian ZX, et al. An investigation based on registered clinical trials on Chinese clinical trial registry for exploring the factors of impacting quality of clinical trials. Chin J Evid-based Med 2018;18:526–31. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergeris A, Tse T, Zarin DA. Trialists’ intent to share individual participant data as disclosed at ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA 2018;319:406–8. 10.1001/jama.2017.20581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viergever RF, Ghersi D. The quality of registration of clinical trials. PLoS One 2011;6:e14701. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.