Significance

Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots of great ecological, economic, and aesthetic importance. Their global decline under climate change and other stresses makes it urgent to understand the molecular bases of their responses to stress, including “bleaching,” in which the corals' photosynthetic algal symbionts are lost, thus depriving the host animals of a crucial source of energy and metabolic building blocks. We sought clues to the mechanisms that cause (or protect against) bleaching by analyzing the patterns of gene expression in a sea anemone relative of corals during exposure to a heat stress sufficient to induce bleaching. The results challenge some current ideas about bleaching while also suggesting hypotheses and identifying genes that are prime targets for future genetic analyses.

Keywords: heat-shock proteins, innate immunity, symbiosis, nutrient transport, reactive oxygen species

Abstract

Loss of endosymbiotic algae (“bleaching”) under heat stress has become a major problem for reef-building corals worldwide. To identify genes that might be involved in triggering or executing bleaching, or in protecting corals from it, we used RNAseq to analyze gene-expression changes during heat stress in a coral relative, the sea anemone Aiptasia. We identified >500 genes that showed rapid and extensive up-regulation upon temperature increase. These genes fell into two clusters. In both clusters, most genes showed similar expression patterns in symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones, suggesting that this early stress response is largely independent of the symbiosis. Cluster I was highly enriched for genes involved in innate immunity and apoptosis, and most transcript levels returned to baseline many hours before bleaching was first detected, raising doubts about their possible roles in this process. Cluster II was highly enriched for genes involved in protein folding, and most transcript levels returned more slowly to baseline, so that roles in either promoting or preventing bleaching seem plausible. Many of the genes in clusters I and II appear to be targets of the transcription factors NFκB and HSF1, respectively. We also examined the behavior of 337 genes whose much higher levels of expression in symbiotic than aposymbiotic anemones in the absence of stress suggest that they are important for the symbiosis. Unexpectedly, in many cases, these expression levels declined precipitously long before bleaching itself was evident, suggesting that loss of expression of symbiosis-supporting genes may be involved in triggering bleaching.

Shallow-water coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots in the tropical and subtropical oceans. These ecologically, economically, and aesthetically important ecosystems are underpinned by reef-building corals, whose ecological and evolutionary success is due in large part to their mutualistic relationship with dinoflagellates in the family Symbiodiniaceae (1). These algal endosymbionts enable corals to thrive in nutrient-poor waters by providing them with photosynthetically derived energy (via the transfer of glucose and perhaps other compounds) and metabolic building blocks, and in return the coral hosts provide the algae with shelter and inorganic nutrients, including ammonium (2–11). However, corals are endangered globally by a variety of anthropogenic stressors, including the rising sea-surface temperatures associated with climate change. These stresses have increased the frequency of coral bleaching, in which the algal symbionts are lost from the coral tissue; when prolonged, bleaching leads to coral death (12, 13).

Because of the critical threat posed by heat-induced bleaching, a major focus of recent research has been to investigate the molecular bases of the coral response to heat stress and the cellular mechanisms underlying heat-induced bleaching. Among other approaches, numerous transcriptomic studies over the past ∼15 y have examined the gene-expression responses to heat stress in corals and related symbiotic cnidarians (recently reviewed in refs. 14, 15). From these studies, it seems clear that heat-stressed symbiotic cnidarians, like most other organisms (16, 17), rapidly (within a few hours) up-regulate the genes encoding the heat-shock-protein (HSP) molecular chaperones (18–22). As two of these studies (18, 19) used aposymbiotic larvae, it appears that the up-regulation of HSP genes does not depend on the presence of algal symbionts but is rather an intrinsic part of the animal’s stress response (as expected from studies in other species). Moreover, the same two studies provided evidence that the up-regulation is transient (again as expected from studies in other organisms), although interpretation of the data is complicated both by the transcriptional changes associated with the concomitant larval development in these studies and by the reliance of each study on a single later time point. Thus, the detailed dynamics of the HSP transcriptional response have remained obscure. Nonetheless, the conclusion that HSP mRNA levels are rapidly but transiently up-regulated during heat stress in cnidarians is consistent with earlier studies showing a rapid but transient up-regulation of Hsp70 protein levels (23, 24).

Although many genes in addition to the HSPs have been reported to be up- or down-regulated during heat stress, there are as yet few cases in which the available data are convincing, consistent across multiple studies, and strongly suggestive of relevant biological mechanisms. For example, one study has reported a large increase in mRNA for the transcription factor NFκB (a major regulator of innate immunity) during the first few hours of heat stress (22), consistent with the hypothesis (25) that activation of innate-immunity and apoptotic pathways plays a central role in bleaching. However, that study only examined gene expression during the first few hours of heat stress, so that the full dynamics of the NFκB response remained unclear. Moreover, another study that examined early time points did not note changes in NFκB mRNA levels (19), whereas of two studies that examined a later time point (∼24 h of heat stress), one reported elevated levels of NFκB mRNA (26) while the other did not (27). A sustained elevation of NFκB mRNA during heat-induced bleaching would be consistent with the evidence that NFκB protein is present at lower levels in symbiotic than in aposymbiotic animals, which may be necessary to avoid innate-immune rejection of the foreign cells (28). In summary, the available data, although intriguing, have not yet provided a clear picture of the expression behavior of NFκB (and thus, presumably, of its targets) during heat stress.

Similarly, several studies have reported up-regulation during heat stress of genes whose products may be protective against the effects of oxidative stress (14, 19, 26, 29–33), consistent with the hypothesis that the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by heat-stressed algal chloroplasts plays a central role in triggering bleaching (25, 34). However, in all of the studies of which we are aware, the response detected has involved only one or a few genes (rather than the whole suite that might be expected), the fold changes observed have been modest, and/or the particular genes reported as up-regulated have been different from those reported in the other studies. Moreover, some studies that seemingly could have seen such changes did not (18, 35–37). Thus, it has remained unclear whether there is a concerted transcriptional response to oxidative stress during heat stress and, if so, whether it depends on the presence of the algal symbionts.

Finally, as the expression of many genes is markedly different between symbiotic and aposymbiotic animals in the absence of stress (7–10, 27, 38–45), it is of interest to ask how the expression of such “symbiosis genes” changes under conditions that will eventually lead to symbiosis breakdown: do their expression levels simply track with the numbers of remaining algae, or do they anticipate or lag behind the bleaching curve? To the best of our knowledge, no studies published to date have addressed this question through comparative time courses of gene expression in symbiotic and aposymbiotic animals.

In summary, despite a considerable effort, we do not yet have a clear picture of the transcriptional responses to heat stress in symbiotic cnidarians or of which of these responses may be involved in causing—or in protecting from—bleaching. The reasons include at least the following: (i) The studies to date have used a variety of cnidarian and algal species, often a variety of genotypes and prior thermal histories for the individuals within a given species, and a variety of temperature and light regimens for the stress experiments themselves, all of which complicate attempts to compare the results of different studies (46). (ii) Such comparisons are further complicated by the changes during the past dozen years in the methods used for such studies, which have progressed from an early reliance on microarrays (with limited numbers of features) and quantitative RT-PCR (of small numbers of preselected genes) to the more comprehensive and quantitatively reliable RNAseq. (iii) Although some studies have analyzed samples collected soon after the imposition of heat stress (and thus well before bleaching is observed), and others have analyzed samples collected considerably later (and thus concomitant with, or even after, bleaching), only one study of which we are aware has analyzed samples of both types, and that study used only aposymbiotic larvae (19). Thus, we have had no real picture of the dynamics of the transcriptional response to heat stress as it relates to bleaching itself. (iv) Although some studies have used aposymbiotic larvae, only two studies of which we are aware have attempted systematic comparisons of gene expression under heat stress in symbiotic and aposymbiotic animals (27, 39), and each of those studies involved a single time of sampling. Thus, there has been little information available on how the presence of the symbiotic algae might influence the dynamics of the heat-stress response, a point of particular interest given the prominent hypothesis suggesting that bleaching is triggered by the release of ROS by heat-stressed algae (25, 34).

In this study, we attempted to achieve a clearer picture of gene expression during heat stress by using RNAseq to analyze samples obtained over a full time course that began soon after the imposition of heat stress and continued until bleaching was essentially complete. We used the small sea anemone Aiptasia (sensu Exaiptasia pallida), a model system with great advantages for study of many aspects of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis (47–49), including the long-term viability of fully aposymbiotic animals (43, 50, 51). The results obtained suggest hypotheses about the molecular and cellular mechanisms of heat-stress response and bleaching that should be testable using the gene-knockdown and gene-knockout methods that are becoming available for symbiotic cnidarians (52–54).

Results

Strategy for Analysis of Gene Expression during Heat Stress.

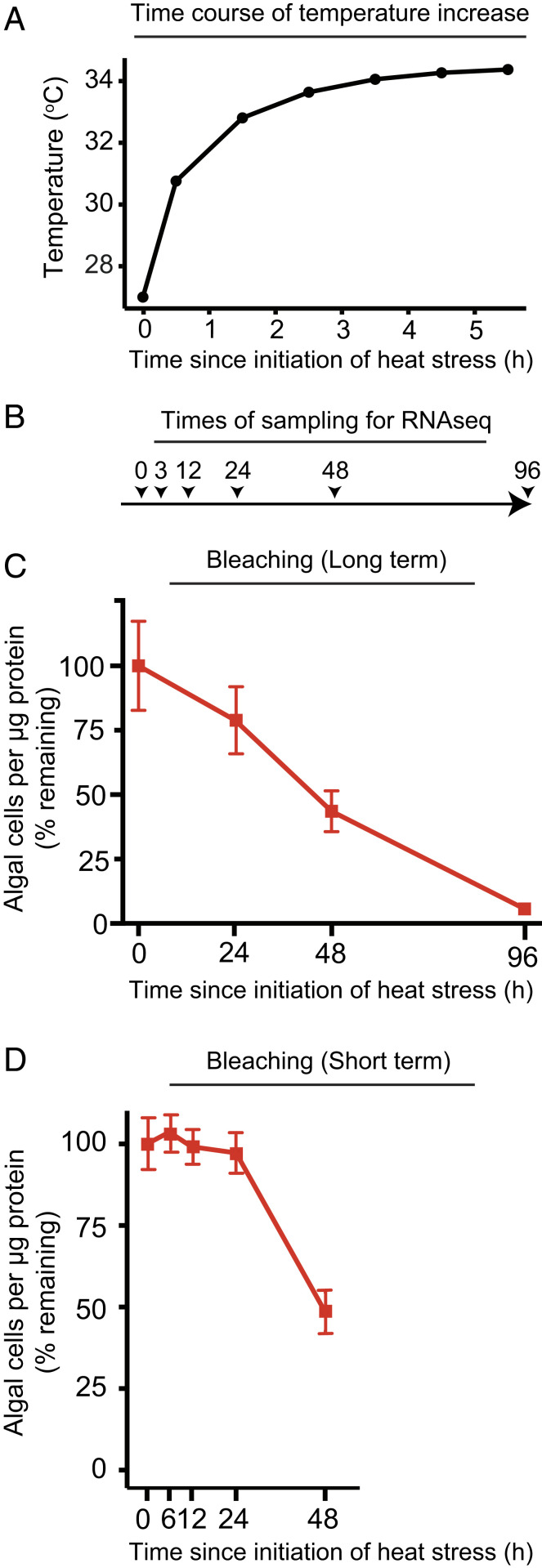

To examine the transcriptional responses of Aiptasia to heat stress, we performed RNAseq time courses on both symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones after a shift to 34 °C (Fig. 1 A and B). For comparison, we also determined bleaching rates in the symbiotic anemones (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Table S1). The sampling times for RNAseq were chosen to capture changes that occurred before, during, and after bleaching.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. (A) Gradual increase in temperature after shifting a tank containing anemones in 1 L of ASW from an incubator at 27 °C to one at 34 °C. (B and C) Time courses of sampling symbiotic (CC7-SSB01) and aposymbiotic (CC7-Apo) anemones for RNAseq analyses (B) and the symbiotic anemones for assessment of bleaching (C). The tanks were shifted from an incubator at 27 °C to one at 34 °C at time = 0. In C, algal counts were normalized to total protein in the homogenates (Materials and Methods) and then expressed as percentages of the value at time = 0. (D) In a separate experiment, bleaching was assessed over a shorter time course. Less bleaching was observed at 24 h than in the experiment of B and C (experiment-to-experiment variability at 24 h probably reflects the fact that bleaching is just beginning at around this time), but the levels of bleaching at 48 h were similar. In C and D, data are shown as means ± SEMs of the percentage values; the actual numbers of algae per microgram (μg) of protein are shown in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Rapid Up-Regulation of Many Immune-Response, Protein-Folding, and Other Genes in both Symbiotic and Aposymbiotic Anemones.

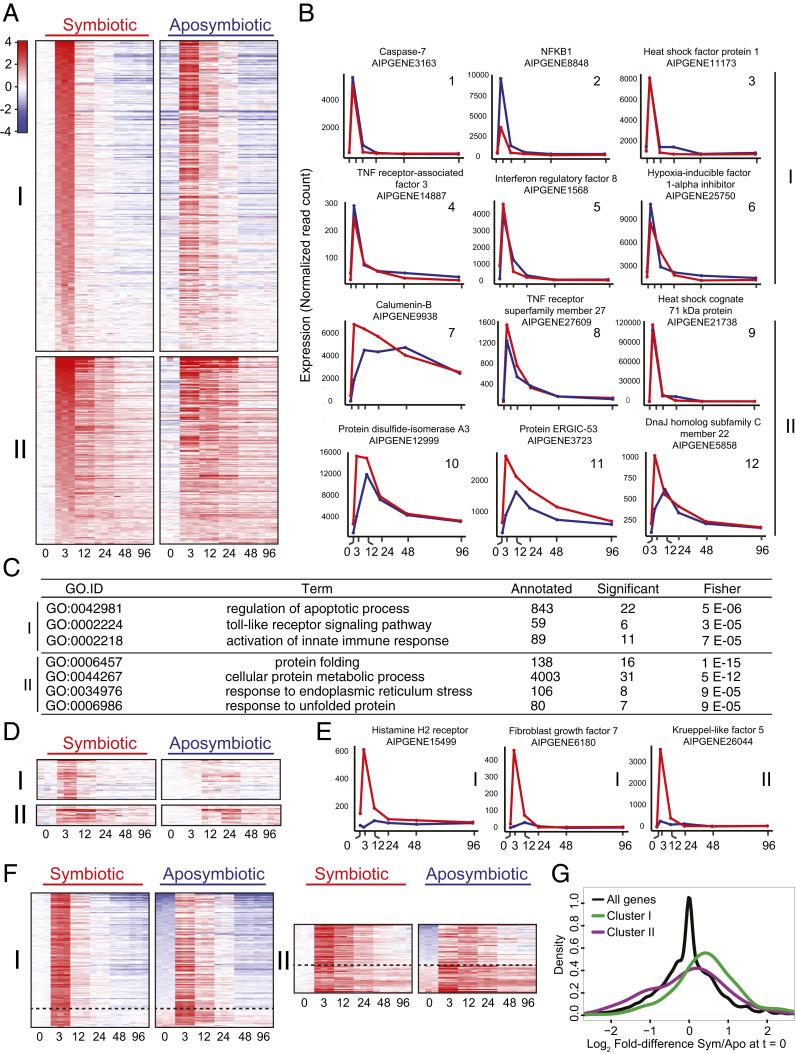

To explore the early transcriptional responses to heat stress, we used DESeq2 to identify genes that were significantly and highly up-regulated (P < 0.05, fold change >4) in symbiotic anemones during the first 3 h after the initiation of heat stress; this revealed a set of 524 genes (Dataset S1). After normalizing the expression of each gene to its value at time = 0, we used k-means clustering to group the genes into two clusters (320 and 204 genes, respectively) based on the similarity of their expression patterns across the time course; we then sorted each cluster according to the fold change from 0 to 3 h (Fig. 2 A, Left). The genes in the two clusters showed similarly dramatic levels of early up-regulation (e.g., 28 and 17 genes with up-regulation by 3 h of more than eightfold in clusters I and II, respectively) but differed in that expression of most genes in cluster I returned to near baseline levels by 12 h, whereas expression of most genes in cluster II returned to baseline levels more slowly (Fig. 2 A, Left and Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Rapid up-regulation of many genes in response to heat stress in both symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones. (A) Heatmaps of genes significantly and highly up-regulated in symbiotic anemones in response to a shift from 27 °C to 34 °C (Left; see text for details) and of the same genes in aposymbiotic anemones (Right). Genes were grouped into two clusters by k-means clustering based on their expression patterns in the symbiotic animals and are sorted by their extents of up-regulation from 0 to 3 h in those animals. Expression values for each gene in the aposymbiotic animals (Right column) were also normalized to the value for that gene in the symbiotic animals at time = 0, and the genes are shown in the same order as in the Left column. Colors in the heatmap are based on a log2 scale (as shown). (B) Expression patterns for example genes in clusters I (plots 1 through 6) and II (plots 7 through 12). Data are shown as raw read counts normalized to library size (Materials and Methods). Red, data for symbiotic animals; blue, data for aposymbiotic animals. (C) Results from GO-term-enrichment analyses of each cluster. The terms shown are those significant in each cluster (Fisher’s P value <1e-4) and represented by ≥6 genes; the full outputs of these analyses are provided in Dataset S2. (D) Heatmaps (color scale as in A) showing genes from clusters I and II after normalizing each gene's expression level to its mean value in aposymbiotic animals at time = 0 and then sorting by the degree of up-regulation from 0 to 3 h in aposymbiotic animals. Shown here are only the genes in which up-regulation in the aposymbiotic animals was less than twofold at 3 h; the complete heatmaps are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. (E) Examples of genes showing differential regulation between symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones. The cluster number for each gene is indicated. Red, data for symbiotic animals; blue, data for aposymbiotic animals. (F) Heatmaps (color scale as in A) of genes as in A but after resorting based on the fold difference between symbiotic and aposymbiotic animals at time = 0. All genes are shown in which this difference was statistically significant (adjusted P value <0.05), independent of the magnitude of the expression difference or of whether expression was higher at 0 h in symbiotic or aposymbiotic animals. The dashed line separates the two groups, and the complete heatmaps are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S2. (G) Smoothened-density histograms (Materials and Methods) of log2 fold differences between symbiotic and aposymbiotic animals at 0 h.

To ask if these early responses to heat stress are affected by the presence of the symbiotic algae, we examined the expression of the same 524 genes over an identical time course at 34 °C in aposymbiotic anemones. Strikingly, most (but not all) genes behaved similarly (Fig. 2 A, Right, Fig. 2B, and Dataset S1; and see below), suggesting that the majority of these gene-expression changes are part of the animal’s core response to heat stress independent of its symbiotic state.

To explore the functions of the genes showing an early response to heat stress, we performed Gene Ontology (GO)-term analyses on clusters I and II (Dataset S2). For cluster I, the most enriched GO terms were related to innate immunity and apoptosis (Fig. 2 C, Top; see also Fig. 2B, plots 1, 2, 4, and 5 for examples; Dataset S1). For cluster II, the most enriched GO terms were related to protein folding and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress response (Fig. 2 C, Bottom; see also Fig. 2B, plots 9, 10, and 12 for examples; Dataset S1).

Inspection of Fig. 2A suggested that some genes did not follow the general rule of rapid up-regulation in aposymbiotic animals paralleling that in symbiotic animals. This set of genes was revealed more clearly when we resorted the genes in each cluster by their fold change between 0 and 3 h in the aposymbiotic animals (Fig. 2 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Some of these genes (particularly in cluster I) seemed not to be up-regulated at all in the aposymbiotic animals during the heat stress, whereas others (particularly in cluster II) seemed to be up-regulated, but only after a delay relative to what was observed in the symbiotic animals. In total, this analysis identified 41 genes in cluster I and 18 genes in cluster II that were up-regulated less than twofold in aposymbiotic animals (versus their more than fourfold up-regulation in symbiotic animals). Surprisingly, inspection of the annotations of these genes (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Dataset S3) did not reveal any obvious common themes.

In particular, none of these genes had annotations relating directly to oxidative-stress response, a surprising result given the common expectation that symbiotic anemones would have higher levels of ROS due to their increased production by heat-stressed algal chloroplasts (25, 34, 55, 56). To explore this issue further, we asked if any of 99 Aiptasia genes with putative roles in the oxidative-stress response (the 97 genes manually curated in ref. 33 plus two genes [AIPGENEs 21344 and 21459] annotated as catalases) were up-regulated early during heat stress. Strikingly, only one of these genes was in either cluster I or cluster II, and this gene was up-regulated to similar extents in symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones (Dataset S1 and SI Appendix, Tables S3A and S3B: AIPGENE 8449). Thus, we found no evidence of an early transcriptional response to ROS that was specific to the presence of the algal symbiont.

Because our initial analysis had focused specifically on genes that were strongly up-regulated during the first 3 h of heat stress, and it seemed possible that a transcriptional response to ROS would be manifested only at later times, we performed two additional analyses. First, we asked if any of the 99 genes were strongly up-regulated (P < 0.05, fold change >4) in symbiotic animals at times later than 3 h. We found only two such genes, both annotated as glutathione S-transferases (Dataset S4 and SI Appendix, Table S3A: AIPGENEs 20480 and 6351). Both were modestly up-regulated throughout the time course and met the more than fourfold cutoff only at 12 h (AIPGENE 20480) or 48 and 96 h (AIPGENE 6351). Moreover, both genes were also up-regulated in aposymbiotic anemones (SI Appendix, Table S3B), while neither was up-regulated in symbiotic relative to aposymbiotic anemones (SI Appendix, Table S3C). Second, we asked if any of the 99 genes were strongly up-regulated (P < 0.05, fold difference >4) in symbiotic relative to aposymbiotic animals at any time point. We found only three such genes (SI Appendix, Table S3C: AIPGENEs 8889, 22290, and 27830), and, strikingly, none of them was also up-regulated during the heat-stress time course in symbiotic anemones (SI Appendix, Table S3A). Even relaxing the fold-change cutoff from fourfold to twofold revealed no very suggestive patterns of expression (SI Appendix, Table S3 and Dataset S4), and, strikingly, neither of the putative catalase genes met even this relaxed criterion. Taken together, these data indicate that at least for this Aiptasia strain and stress conditions, there is no concerted and strong transcriptional response to oxidative stress during heat stress despite the occurrence of nearly complete bleaching during the time course (Fig. 1).

Inspection of Fig. 2A also suggested that some of the genes that underwent dramatic up-regulation during the first 3 h of heat stress were also expressed at substantially higher levels in symbiotic than in aposymbiotic animals in the absence of stress. Such genes were revealed more clearly when we resorted the genes in each cluster according to the magnitude of the difference in expression between symbiotic and aposymbiotic animals at time = 0 (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2); they were present in both clusters (based on P < 0.05; fold difference > 2) but more numerous in cluster I (57 genes, ∼18%) than in cluster II (22 genes, ∼11%) (SI Appendix, Table S4 and Dataset S5). Such genes were also enriched relative to their frequency among all genes, particularly in cluster I (Fig. 2G; P < 2e-16 for cluster I and P < 0.02 for cluster II by two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests). Many of these genes have annotations related to immune response or apoptosis (particularly in cluster I: SI Appendix, Table S4A) and protein folding (particularly in cluster II: SI Appendix, Table S4B). These data suggest that there may be stress arising from the presence of the algae even at a nominally nonstressful temperature (Discussion).

Apparent Involvement of the NFκB and HSF1 Transcription Factors in the Early Up-Regulation of Stress-Responsive Genes.

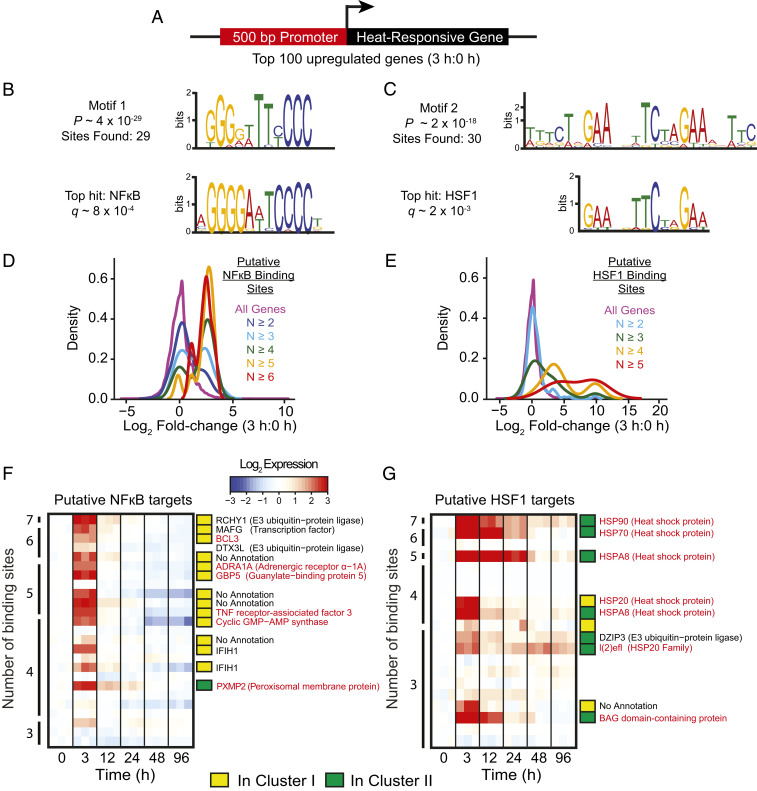

The seemingly coordinated up-regulation of many genes during the early hours of heat stress suggested that there might be common control by specific transcription factors. To explore this possibility, we first identified the 100 genes with the greatest up-regulation over the first 3 h of heat stress in symbiotic animals; 58 of these genes were in cluster I of Fig. 2A, and 42 were in cluster II. In each case in which the genome assembly contains 500 bp immediately upstream of the putative transcription start site (Fig. 3A; 96 of the 100 genes), we searched these 500 bp for significantly enriched DNA motifs (Materials and Methods). Remarkably, these searches identified two DNA motifs with high confidence (Fig. 3 B and C, Upper) that corresponded (again with high confidence) to canonical binding sites for the transcription factors NFκB and HSF1 (Fig. 3 B and C, Lower). In the 96 upstream regions, we found 29 putative NFκB binding sites (20 in 10 genes of cluster I; 9 in 9 genes of cluster II) and 30 putative HSF1 binding sites (9 in 8 genes of cluster I; 21 in 10 genes of cluster II). Consistent with the hypothesis that NFκB and HSF1 are important in driving the early burst of gene up-regulation upon heat stress, the genes encoding these two transcription factors were themselves highly up-regulated early in the course of heat stress (Fig. 2B, plots 2 and 3).

Fig. 3.

Enrichment of potential NFκB and HSF1 binding sites in the promoter regions of genes that are highly up-regulated during heat stress. (A) Strategy used to search for transcription-factor binding sites involved in the response to heat stress; see text for details. (B and C) Logo plots showing the top two hits returned by the MEME search (Upper plots) and their correspondence to canonical binding sites (Lower plots) for transcription factors NFκB (B) and HSF1 (C); see text for details. (D–G) Correlations between numbers of putative binding sites for NFκB (D and F) and HSF1 (E and G) and degrees of up-regulation of the associated genes. (D and E) Smoothened-density histograms for the indicated numbers of binding sites plotted as a function of the log2 fold changes in transcript levels between 0 and 3 h after the shift to 34 °C for all genes in the genome. (F and G) Heatmaps showing changes in transcript levels (log2 scale; see key) as a function of time since the initiation of heat stress for all of the genes with four or more putative NFκB (F) or HSF1 (G) binding sites plus some of the genes with three such sites in each case. Annotations were obtained from ref. 7 and by manual BLASTP searches against nonredundent databases on NCBI for genes with no annotation (99); red font shows genes that are known to be regulated by the respective transcription factor in at least one other organism.

To explore further whether the identified motifs, and their associated transcription factors, are indeed involved in the up-regulation of genes in response to heat stress, we performed two additional bioinformatic analyses. First, for all 22,872 annotated Aiptasia genes with 500 bp of immediately upstream sequence present in the genome assembly, we searched these 500-bp segments for the presence of each motif and then correlated the numbers of motifs found with the degrees of up-regulation found during the first 3 h of heat stress (Materials and Methods). The smoothened-density plots showed a strong correlation between the numbers of such motifs and the degrees of up-regulation (Fig. 3 D and E). Second, we examined the specific genes with three or more putative NFκB or HSF1 binding sites in their upstream regions. Strikingly, not only did many of these genes show strong up-regulation during the first 3 h of heat stress, but many of them are the Aiptasia homologs of genes known to be targets of these same transcription factors in other organisms (Fig. 3 F and G). Moreover, the putative NFκB and HSF1 target genes identified in this way had expression patterns similar to those typical of cluster I (rapid return to baseline) and cluster II (slower return to baseline), respectively, suggesting the existence of distinct patterns of regulation in the response to heat stress that are driven at least in part by NFκB and HSF1.

Surprisingly Rapid Changes in Expression of Many Genes with Putative Roles in Symbiosis Maintenance.

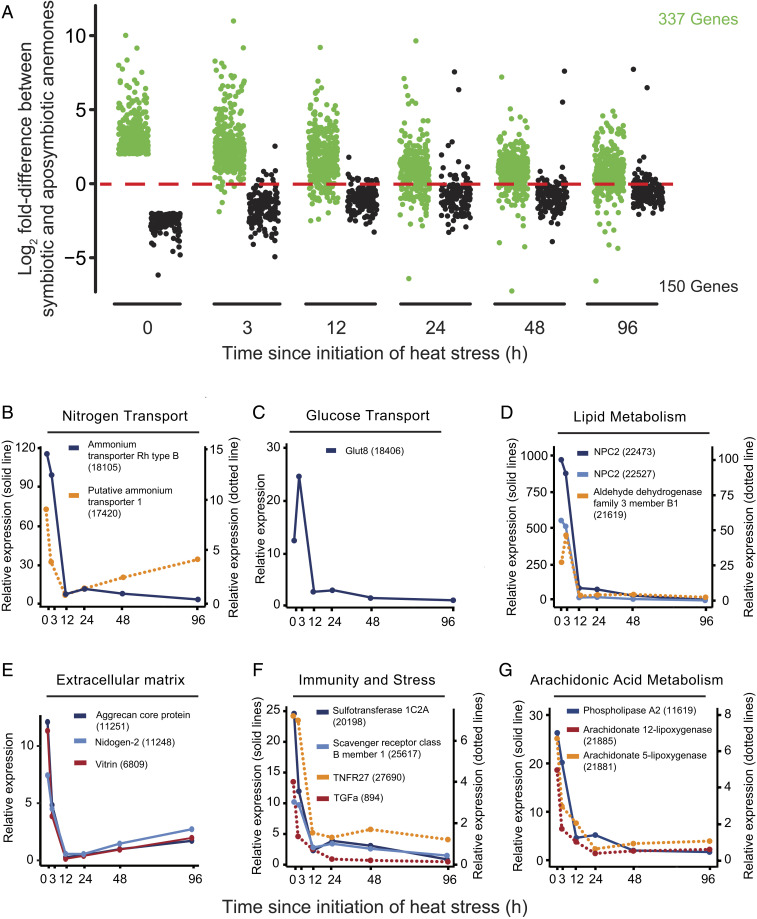

Previous studies have identified many genes that are differentially expressed between symbiotic and aposymbiotic cnidarians (in the Introduction). To investigate the behavior of such genes as symbiosis begins to break down under heat stress, we first identified the genes that showed strong differential expression (P < 0.05; fold difference >4 or <0.25) in our RNAseq dataset at time = 0, finding 337 that were up-regulated and 150 that were down-regulated in symbiotic relative to aposymbiotic anemones. We then followed these differences in expression during the period of heat stress (Fig. 4A). Not surprisingly, for many genes, the expression levels in the symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemone populations gradually converged as the symbiotic animals lost algae through bleaching (and thus approached the aposymbiotic state). Unexpectedly, however, for some genes the expression levels had changed dramatically by 12 or even 3 h (Fig. 4A), although no bleaching was detected until 24 h or later (Fig. 1 C and D).

Fig. 4.

Rapid changes in expression of many symbiosis-related genes after onset of heat stress. In the experiment of Fig. 1 A–C, genes with strong differential expression (≥4-fold, P < 0.05) between symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones prior to heat stress were identified and analyzed. (A) Dot plots of the ratios of expression levels between symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones for individual genes (log2 scale) as a function of time after the temperature shift. Both genes expressed at higher levels at time = 0 in symbiotic anemones (green dots) and those expressed at higher levels in aposymbiotic anemones (black dots) are shown. (B–G) Examples of genes whose expression is rapidly down-regulated in symbiotic anemones after the temperature shift. The mean expression values for each gene at each time in symbiotic anemones are shown relative to the mean expression of that gene in aposymbiotic anemones at time = 0. See SI Appendix, Table S5A and the text for more details.

To investigate these genes further, we first ranked the 337 genes that were initially expressed at higher levels in symbiotic anemones (green dots in Fig. 4A) by their fold decrease in expression in symbiotic anemones between 0 and 12 h (SI Appendix, Table S5A and Dataset S6). Strikingly, ∼25% (84 of 337) of these genes fell 3-fold or more during the first 12 h of heat exposure, with ∼5% (18 of 337) dropping 10-fold or more. Interestingly, among the genes whose expression dropped most rapidly were ones encoding ammonium-, glucose-, and sterol-transport proteins (Fig. 4 B–D and SI Appendix, Table S5A), all of which are likely to be involved in metabolite exchanges critical for support of the symbiosis. Other genes with dramatic early decreases in expression (Fig. 4 E–G and SI Appendix, Table S5A) include ones encoding extracellular-matrix/cell-adhesion, innate-immunity/stress-response, and potential signaling proteins, as well as proteins involved in lipid (including arachidonic acid) metabolism, all of which may also be important to support the symbiosis. Thus, the host begins to reduce the expression of many symbiosis-supporting genes long before bleaching is detected (Discussion).

We performed similar analyses of the 150 genes that were initially expressed at lower levels in symbiotic anemones (black dots in Fig. 4A), keeping in mind the ambiguity as to whether these genes should be viewed as down-regulated in unstressed symbiotic anemones, up-regulated in unstressed aposymbiotic anemones, or both. We first ranked the genes in this group by their fold increases in expression between 0 and 12 h in symbiotic anemones. However, this analysis was uninformative: only 10 genes had fold changes more than twofold, and their associated annotations did not fit any evident pattern (SI Appendix, Table S5B and Dataset S7). We then ranked the same genes according to their fold decreases in expression between 0 and 12 h in aposymbiotic anemones, obtaining potentially more informative results. Again, just 10 genes had fold changes <0.5-fold, but several of these did have annotations suggestive of possible roles in symbiont uptake or the digestion of food (both processes that might well be enhanced in aposymbiotic animals) (SI Appendix, Table S5C and Dataset S8). However, why heat stress would drive down the expression of these genes remains mysterious.

Discussion

It is important to understand both the mechanisms that cause coral bleaching under heat stress and those that may help protect against it. To this end, we used RNAseq to examine gene expression in the sea anemone Aiptasia through a time course that began soon after the start of heat stress and continued until bleaching was essentially complete. By using closely controlled laboratory conditions and clonal populations of both the animal host and the algal symbiont, we eliminated some of the variables that have complicated interpretation of many earlier studies (46). By focusing on genes with relatively large changes in mRNA levels, we tried to identify cases in which there would actually be significant changes at the protein level [for which mRNA levels are only a rather crude proxy (33, 57)]. And by subjecting both symbiotic and aposymbiotic anemones to the full time course in parallel, we could ask which aspects of the animal’s response relate directly to the presence of algal symbionts. The results have provided a clearer picture of the heat-stress response than has been available previously and suggest numerous hypotheses for which critical experimental tests should now be possible (58).

Highly Transient Up-Regulation of a Large Set of Genes Including Many Implicated in Innate-Immunity Function.

Our analyses revealed a set of >300 genes that were rapidly (within <3 h) and extensively (more than fourfold) up-regulated upon exposure of symbiotic anemones to heat stress but whose transcript levels also returned rapidly (by ≤12 h) to near-baseline levels even during continued heat stress (Fig. 2, cluster I). Many of these genes encode proteins with putative functions in innate immunity or apoptosis, and indeed many of them appear to be targets of the innate-immunity transcription factor NFκB. The finding of conserved NFκB binding sites in the Aiptasia genome was not in itself surprising (59), but their concentration in the regions upstream of genes that are highly up-regulated during heat stress was striking. The NFκB gene itself is in cluster I (Fig. 2B, plot 2), as are the genes encoding several proteins likely to be upstream or downstream of NFκB in a TNF-like signaling pathway (Fig. 2B, plot 4 and Dataset S1), while several other functionally related genes were in a second group (cluster II) of rapidly up-regulated genes (Fig. 2B, plot 8 and Dataset S1; see also below). Rapid up-regulation of some of these genes under heat stress had been reported previously [e.g., NFκB (22); TRAF3 (26, 32, 37)] but neither the full extent of this response nor its striking transience had been clear.

NFκB-regulated activation of innate-immunity and apoptotic pathways has been proposed to play a major role in bleaching (25, 60), a model consistent with recent evidence indicating that NFκB protein and activity levels are reduced in symbiotic relative to aposymbiotic Aiptasia (28). However, our results pose significant challenges for this model. First, the mRNA levels for most of these genes have returned to near-baseline levels well before bleaching is even detectable, much less complete. These observations are not necessarily incompatible with the model, because it is possible that the levels of the relevant protein products stay elevated long after the mRNA levels have declined and/or that the early activation of these genes triggers a later wave(s) of activation of other genes whose products are more directly involved in bleaching. However, it should be noted that the brief elevation of caspase 7 mRNA levels (Fig. 2B, plot 1) is paralleled by a similarly brief elevation of caspase enzyme-activity levels during heat stress (61), one of several lines of evidence suggesting that apoptosis does not play a major role in bleaching under these conditions (61). Nonetheless, as NFκB has many roles, it may be involved in bleaching in some way other than its promotion of apoptosis through caspases. Second, most of the genes in this group had very similar expression profiles in aposymbiotic anemones, indicating that this aspect of the response to heat stress is inherent to the animal and not specific to the presence of the symbiotic algae. However, these observations are also not necessarily incompatible with the model, because it is possible that an ancestral animal response to heat stress was co-opted during evolution to provide a mechanism for ridding the animal cells of algal partners that have become unwanted under stress conditions.

Resolution of these questions is likely to come only when the rates of bleaching can be evaluated in animals in which the genes encoding NFκB and/or others of this early up-regulated set have been inactivated. Fortunately, such experiments should soon be possible using the recently developed methods for morpholino-based gene knockdown (52) and CRISPR-based gene knockout (53, 54) in corals.

Longer Lasting Up-Regulation of a Large Set of Genes Including Many Implicated in Protein Homeostasis.

A second group of >200 genes showed equally striking early up-regulation but, in most cases, a slower return of mRNA levels to baseline during continued heat stress (Fig. 2, cluster II). Many of these genes encode proteins expected to function in protein folding and the response to ER stress. Early up-regulation of some of these genes in heat-stressed corals had been reported previously (18–22) and is consistent with the very wide conservation of these heat-stress responses in animals and other eukaryotes (16, 17). Many of the up-regulated genes appear to be targets of the transcription factor HSF1, as expected from extensive studies in other organisms (62), and the HSF1 gene itself was rapidly and extensively up-regulated in our experiment (Fig. 2B, plot 3).

Like the cluster I genes (see above), most of the cluster II genes showed up-regulation in aposymbiotic anemones that was very similar to that in symbiotic anemones. However, as argued above, the products of these genes might still play roles either in promoting bleaching or in protecting the animals from it. Indeed, given the well established role of the heat-shock proteins in protecting various types of cells from protein damage during heat stress, it seems likely that at least some of the cluster II gene products will prove to be protective (up to a point) against the stresses that lead to bleaching. In this regard, we have recently shown that a CRISPR-induced knockout of the gene encoding HSF1 produces increased sensitivity to heat-stress-induced death in aposymbiotic larvae of the coral Acropora millepora (54). As Acropora larvae can be infected with Symbiodiniaceae strains and then subjected to bleaching tests (63, 64), it should now be straightforward to ask whether a knockout of HSF1 (or of any of its targets) also produces an increased sensitivity to heat-induced bleaching.

Apparent Absence of a Gene-Expression Response to Oxidative Stress during Heat Exposure.

About 10% of the genes in clusters I and II differed from the majority in showing a delayed and/or much weaker up-regulation under heat stress in aposymbiotic than in symbiotic anemones (Fig. 2 D and E). Examination of the annotations of these genes did not reveal any obvious common themes, and, in particular, none of them encodes a protein known to be directly involved in response to oxidative stress. More extensive analyses of our data also failed to find any substantial signature of up-regulation of oxidative-stress-response genes during heat exposure (Results), even though bleaching was essentially complete by the end of the time course.

These results were initially surprising, given the prominence of models in which photosynthetically produced ROS play a central role in triggering bleaching (25, 34, 55, 56). However, examination of the literature revealed that previous gene-expression studies have also found either the up-regulation of only one or a few oxidative-stress-response genes during heat exposure, and generally with only modest levels of up-regulation (14, 19, 26, 29–33) or no such up-regulation at all (18, 35–37). Thus, to date, gene-expression studies in a variety of symbiotic cnidarians, using a variety of light- and heat-stress conditions, have failed to produce appreciable support for the ROS-induced-bleaching model.

However, these results do not necessarily invalidate the model. First, it is possible that increased levels of ROS during heat stress result in changes in transcript levels that are biologically meaningful but less than the twofold cutoff used in our analyses, that the relevant genes are not known to be involved in response to oxidative stress, or both. Second, it is possible that there is relevant regulation, but all at the posttranscriptional level. This might explain the apparent discrepancy between results at the mRNA level and those reported at the protein and enzyme-activity levels (34, 65–72). Third, our experiment used rather low light levels and a spectrum with little UV, and it is possible that experiments with more intense light or a full-sunlight spectrum would have yielded different results. However, it must be noted both that the conditions in our experiment did lead to full bleaching within ∼4 d and that some of the other studies cited above used more intense light, full-spectrum sunlight, or both, so that this possibility does not actually seem likely. Moreover, in a previous study, we observed that bleaching under heat stress could occur as rapidly in the dark as in the light both in Aiptasia and in several species of corals (73), results clearly incompatible with the hypothesis that photosynthetically derived ROS are necessary to trigger bleaching. Other studies have also reported results that are difficult to reconcile with the ROS-induced bleaching model (41, 44, 71, 74–76). We suggest that the possible role, if any, of photosynthetically produced ROS in bleaching will not be settled until bleaching rates have been measured in animals in which genes encoding proteins involved in controlling oxidative stress have been knocked down or knocked out, experiments that should now be feasible (52–54).

Evidence That the Presence of Algae May Be Stressful Even in the Absence of Heat.

Among the genes up-regulated early in response to heat stress were a substantial number that were already up-regulated in symbiotic relative to aposymbiotic anemones under nominally nonstressful conditions (Fig. 2F). Such genes were much more frequent than expected by chance, particularly in cluster I (Fig. 2G), and annotations relating to immunity, apoptosis, and protein folding appeared to be particularly frequent among them (SI Appendix, Table S4), even given the high overall frequencies of such annotations in the full clusters I and II. Taken together, these results suggest that even at nonstressful temperatures, symbiotic anemones experience some stress simply due to the presence of the algal symbionts. Although it is not yet clear what that stress might be, it may represent a physiological cost to the host that partially offsets the benefits of the symbiosis, as has been observed in many other mutualisms (77–79).

Possible Roles in Bleaching of a Rapid Down-Regulation of Many Symbiosis-Related Genes.

As observed also by others (7–10, 27, 38–45), we found that many genes were highly up-regulated in symbiotic relative to aposymbiotic anemones prior to stress (Fig. 4A, 0 h). The differential expression of these genes and putative functions of their products suggest that they have direct and important roles in supporting the symbiosis. Thus, we expected that in most cases, their levels of up-regulation would decline in parallel with the numbers of algal cells during bleaching, and such a gradual decline was indeed observed for many genes. Unexpectedly, however, we also found that in addition to some genes in this group that were actually up-regulated in response to heat stress (see preceding section), ∼25% were very rapidly down-regulated (to essentially aposymbiotic levels) by 12 or even 3 h (Fig. 4), and thus long before any bleaching was detected. The products of the genes showing this behavior include transporters likely to be involved in metabolite exchange between the host and alga, extracellular-matrix proteins that might be involved in surface contacts between host and algal cells, enzymes of lipid metabolism, and other proteins that might be involved in signaling between the symbiotic partners. Thus, it appears that host transcriptional support for important aspects of the symbiosis shuts down well before any actual loss of algae occurs. An important remaining question is whether the levels of the corresponding gene products also decline precipitously during the early hours of heat stress; this question should be answerable by experiments using appropriate antibodies or proteomic methods.

It will be of interest to determine what causes the rapid down-regulation of transcript levels. In this regard, it may be relevant that at least 20 putative transcription factors are in the sets of very rapidly up-regulated and very rapidly down-regulated genes (Datasets S1 and S6). Regulation by miRNAs might also be a factor (45). Further insight might be gained by examining the relative timing of the various transcriptional changes in an RNAseq time course with multiple time points during the first few hours of heat stress. However, a deeper understanding is likely to require experiments in which the relevant genes have been ectopically expressed from constitutive promoters, knocked down or knocked out, or both; such experiments should now be feasible (52–54, 80).

Of perhaps greater interest, however, is to ask how the rapid down-regulation of symbiosis-related genes relates to the breakdown of the symbiosis that follows later. Possible models include at least the following:

-

(i)

Breakdown of the symbiosis at the cellular level (ejection of algae from host gastrodermal cells) actually occurs much earlier than is evident from whole-animal color or algal counts on whole-animal homogenates. This possibility should be testable by real-time fluorescence video microscopy that takes advantage of the intrinsic chlorophyll fluorescence of the algae.

-

(ii)

Very soon after the onset of heat stress, the algae cease to release something that they normally provide to the host [e.g., glucose (6) or sterols (8, 10)], in response to which the host turns off genes necessary for support of the algae [e.g., the symbiosome-membrane NH3 transporter(s)], resulting in algal loss. This model is attractive in part because it fits well with an increasing body of evidence for the importance of nutritional interactions (and, especially, the regulation of nitrogen supply) in the control of algal numbers in symbiotic corals and anemones (4, 5, 9, 11, 81–88). Evaluation of this model should probably begin by establishing [by gene knockdown or knockout (52–54)] which of the metabolite-transporter genes [e.g., GLUT8 (43), the two NPC2s (8, 10), and the two NH3-transporter genes (9, 43) (Fig. 4B)] are actually essential for symbiosis maintenance. Evaluating heat-induced bleaching in animals expressing the appropriate NH3 transporter(s) from a constitutive promoter [which should soon be possible (54, 80)] might ultimately provide an incisive test of the model.

-

(iii)

Very soon after the onset of heat stress, the algae begin to release something (e.g., ROS; see, however, above) that is toxic to the host, in response to which the host turns off genes necessary for support of the algae, resulting in bleaching. This model might also be tested by establishing constitutive expression of (for example) an NH3 transporter, although the consequences of thus potentially forcing retention of a source of toxic molecules are difficult to predict.

-

(iv)

Very soon after the onset of heat stress, the host initiates a response in which it turns off genes necessary for support of the algae, resulting in bleaching. It is difficult to see why the host would do this, except in the context of model 2 or 3, but experimental tests could proceed along lines similar to those discussed above.

Rapidly Responding Genes as Possible Early Biomarkers for Coral Bleaching.

The identification of many genes that undergo large changes in expression (up or down) many hours in advance of the actual loss of algae from the host raises the possibility of using these changes in expression as early biomarkers of incipient coral bleaching. This idea presupposes only that the kinds of changes seen here in Aiptasia will be observed also in corals of ecological interest, which should be straightforward to test and indeed is already supported by considerable published data (18–22, 37). Such tests may be easier to deploy in the field if they can be done using protein rather than mRNA levels, but the degree to which protein levels track mRNA levels in this system is an issue that needs to be explored in any case, as already noted above.

Concluding Remarks.

It is important to note several limitations of this study. First, we examined a single combination of host and algal strain and subjected it to a moderate heat stress under low light, such that bleaching occurred to near completion over ∼4 d. Examination of a more (or less) sensitive holobiont or the use of more extreme conditions (e.g., higher light) might yield at least some different results. Second, except for the potential oxidative-stress-response genes, we focused here entirely on genes whose expression changed dramatically in the first few hours of heat stress. It is possible that an analysis focused on genes whose expression is altered strongly when bleaching is in full swing (e.g., ∼48 h in this study) would lead to additional interesting findings. Third, our analysis was done with mRNAs extracted from whole animals, so that we might have missed changes in expression that were strong but occurred only in specific cell types. Fortunately, methods for doing such cell-type-specific analyses have emerged and are improving rapidly (89, 90). Nonetheless, despite its limitations, this study has suggested a variety of specific hypotheses that should be susceptible to rigorous experimental tests using methods that are already available or rapidly emerging, as indicated above.

Materials and Methods

Aiptasia Strains and Husbandry.

All animals were from the clonal population CC7, which naturally contains algal symbionts of the Symbiodiniaceae clade A species Symbiodinium linucheae (61, 91). CC7 animals were rendered aposymbiotic as described previously (92, 93), generating strain CC7-Apo. CC7-Apo animals were then exposed to algae of the clonal, axenic strain SSB01 [Symbiodiniaceae clade B species Breviolum minutum (7, 93)] and grown under standard conditions (see below) until the algal population was in steady state. The resulting strain CC7-SSB01 was checked periodically by sequencing PCR-amplified fragments of cps23S (chloroplast rDNA), 18S (nuclear rDNA), and/or ITS2 (nuclear rDNA), as described previously (93), to ensure that the animals had not been repopulated by S. linuchae or another algal type.

Except where noted, animal stocks were maintained at 27 °C in artificial seawater (ASW) prepared using Coral Pro Salt (Red Sea) at 33.5 ppt in deionized water (dH2O) under a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle at an irradiance of ∼25 µmol photons m−2 s−1 (Phillips Alto II 25 W white fluorescent bulbs). Anemones were fed every 2 to 3 d with freshly hatched Artemia nauplii, and the water was changed on the days after feeding.

Design of Heat-Stress Experiments and Quantification of Bleaching.

To investigate the transcriptional response of Aiptasia to thermal stress, CC7-SSB01 and CC7-Apo anemones were first acclimated at 27 °C for ∼2 mo with a normal feeding regimen. For the experiment, polycarbonate tanks containing 1 L of ASW were used. Each of three tanks contained ∼35 CC7-SSB01 anemones, while each of three other tanks contained ∼25 CC7-Apo anemones. Time = 0 samples were taken at 3 h into the light phase, after which the tanks were shifted (within ∼20 min) to an incubator at 34 °C. The ASW gradually warmed to 34 °C over several hours (Fig. 1A), and anemones were not fed after the temperature shift. Anemones of each strain were sampled at 6.5 h into the light phase (thus, slightly more than 3 h after the tanks were shifted to the 34 °C incubator: time = 3-h samples), 9 h later (time = 12-h samples), and 3.5 h into the light phase on each of several subsequent days (time = 24-h, 48-h, and 96-h samples). At each time of sampling, three anemones were removed from each tank, pooled (thus, six samples containing three anemones apiece), and preserved in RNAlater (Ambion) at −20 °C until RNA extraction for RNAseq analysis. In addition, at times 0, 24, 48, and 96 h, eight individual CC7-SSB01 animals were removed at random from the three tanks (typically three from each of two tanks and two from the third), transferred into separate wells of a 96-well plate containing 500 µL of 0.01% SDS detergent (Sigma-Aldrich) in dH2O, and frozen at −20 °C for subsequent quantification of algal numbers by flow cytometry using a Guava cytometer (Millipore) as described previously (94). Each algal count was normalized to the total protein of the same anemone homogenate using the Thermo Scientific Pierce BCA assay (94).

The short-term bleaching experiment was performed similarly except that a single tank was used; eight anemones per time point were analyzed individually as just described.

RNA Isolation and Sequencing.

Total RNA was extracted from each pool of three anemones using the RNAqueous-4PCR Kit (Ambion AM1914) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA-integrity number of each sample was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer; all samples had values ≥8 and were therefore used for sequencing. For each sample, ∼1 µg of total RNA was processed (including the poly-A+ selection step) using the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina FC-122-1001) and following the manufacturer’s instructions to produce indexed libraries. The resulting libraries were pooled based on their indices (as described in the kit instructions), and sequencing of 36-bp single-end reads was performed by the Stanford Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer.

Analysis of Differential Gene Expression and GO-Term Analyses.

Reads were aligned to the Aiptasia genome (version 1.0) (7) using STAR (version 2.5.1b) (95) under default alignment parameters. Read counts for each gene were then generated using the Aiptasia gene models (version 1.0) using HTSeq (version 0.6.1) under default parameters (96). To generate library-normalized expression counts for each gene, raw read counts were normalized to the total numbers of reads from the corresponding libraries using the function counts with the parameter normalize = TRUE in DESeq2 (97). To identify differentially expressed genes, we used DESeq2 with the default parameters to generate fold-change (log2) expression ratios and adjusted P values (97). These expression ratios were used for all analyses except the ranking of genes for the motif analysis (see below) and for the analysis of symbiosis-associated genes (SI Appendix, Table S5). In these cases, shrunken log2 fold-change values (which are more accurate for gene ranking) were used after generation using the function lfcshrink in DEseq2 (97). For hierarchical clustering, we used the function rlog in DESeq2 to generate normalized, log2-transformed read counts and perform k-means clustering using the pheatmap function and specifying the number of clusters with the parameter kmeans_k. Smoothened density histograms were generated in R using the density function with default parameters. The statistical significance of differences between these histogram distributions was assessed using a two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (function ks.test in R).

To conduct the GO-term analyses, we used the R function topGO using default parameters except for specifying the program to report the top 20 terms and the gene-ontology level as biological process (parameters: topNodes = 20 and ontology = BP). We used the GO terms for each gene from the Aiptasia genome version 1.0 as our database (7). Enrichment analysis was done for each query GO-term list against this database using a Fisher’s exact test (parameter: statistic = Fisher). All analyses in R were performed using RStudio version 1.1.414 with the R version 3.5.1.

Analysis of Putative Transcription-Factor Binding Motifs.

We used the function lfcShrink in DESeq2 to generate log2 fold-change ratios for 3-h read counts vs. 0-h read counts for all genes in symbiotic anemones, and we used these ratios to rank the genes (97). For each of the top 100 most-up-regulated genes, we used a custom Python script (Python version 2.7.13) to extract the putative promoter sequence, defined as the 500 bp immediately upstream of the predicted transcription start site in the gene model. Four of the 100 genes did not have a full 500 bp upstream of their transcription start sites in the genome assembly and so were not included in the further analysis. We then used the 96 500-bp sequences to identify enriched motifs (possible binding sites for transcription factors) using the program MEME with the following parameters: max width = 25, motif site distribution = “any number of sites per sequence”, and maximum number of motifs = 2. The resulting enriched motifs were then searched against a database of known transcription factor binding sites with the TOMTOM program using default parameters. Next, we used the program FIMO to quantify the numbers of these motifs within the putative promoters of all 22,872 genes for which the gene models contain a full 500 bp immediately upstream of the putative transcription start site. To increase the specificity of the motif search, the sequence of the enriched HSF1 motif (Fig. 2 C, Top) was trimmed to “GAANNTTCTAGAA” to match the size of the canonical HSF1 binding site (Fig. 2 C, Bottom). The enriched Aiptasia NFKB motif (Fig. 2 B, Top) was used without alteration. The MEME, TOMTOM, and FIMO programs are parts of the MEME suite web server (98).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Amanda Tinoco for assistance with bleaching experiments and members of our own and the Arthur Grossman and Stephen Palumbi laboratories for many helpful discussions. Funding for this study was provided by grants from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Grant 2629.01), the Simons Foundation (LIFE#336932), and the National Science Foundation (IOS EDGE Award 1645164). This work used the Genome Sequencing Service Center of the Stanford Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine, supported by grant awards NIH S10OD025212 and NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P30DK116074.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2015737117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All data for this paper are provided in the main text or SI Appendix. Raw sequences and metadata have been deposited in the NCBI BioProject database (accession no. PRJNA662400).

References

- 1.LaJeunesse T. C., et al. , Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 28, 2570–2580 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muscatine L., Porter J. W., Reef corals: Mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience 27, 454–460 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkowski P. G., Dubinsky Z., Muscatine L., Porter J. W., Light and the bioenergetics of a symbiotic coral. Bioscience 34, 705–709 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkowski P. G., Dubinsky Z., Muscatine L., McCloskey L., Population control in symbiotic corals. Bioscience 43, 606–611 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J., Douglas A. E., Nitrogen recycling or nitrogen conservation in an alga-invertebrate symbiosis? J. Exp. Biol. 201, 2445–2453 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burriesci M. S., Raab T. K., Pringle J. R., Evidence that glucose is the major transferred metabolite in dinoflagellate-cnidarian symbiosis. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3467–3477 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgarten S. et al., The genome of Aiptasia, a sea anemone model for coral symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 11893–11898 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dani V. et al., Expression patterns of sterol transporters NPC1 and NPC2 in the cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Cell. Microbiol. 19, e12753 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui G. et al., Host-dependent nitrogen recycling as a mechanism of symbiont control in Aiptasia. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008189 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hambleton E. A. et al., Sterol transfer by atypical cholesterol-binding NPC2 proteins in coral-algal symbiosis. eLife 8, e43923 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang T. et al., Symbiont population control by host-symbiont metabolic interaction in Symbiodiniaceae-cnidarian associations. Nat. Commun. 11, 108 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoegh-Guldberg O., Poloczanska E. S., Skirving W., Dove S., Coral reef ecosystems under climate change and ocean acidification. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 158 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes T. P. et al., Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis Y. D., Bhagooli R., Kenkel C. D., Baker A. C., Dyall S. D., Gene expression biomarkers of heat stress in scleractinian corals: Promises and limitations. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 191, 63–77 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cziesielski M. J., Schmidt-Roach S., Aranda M., The past, present, and future of coral heat stress studies. Ecol. Evol. 9, 10055–10066 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindquist S., Craig E. A., The heat-shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22, 631–677 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morimoto R., Tissieres A., Georgopoulos C., Eds., Stress Proteins in Biology and Medicine, (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Lanetty M., Harii S., Hoegh-Guldberg O., Early molecular responses of coral larvae to hyperthermal stress. Mol. Ecol. 18, 5101–5114 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer E., Aglyamova G. V., Matz M. V., Profiling gene expression responses of coral larvae (Acropora millepora) to elevated temperature and settlement inducers using a novel RNA-Seq procedure. Mol. Ecol. 20, 3599–3616 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenkel C. D. et al., Development of gene expression markers of acute heat-light stress in reef-building corals of the genus Porites. PLoS One 6, e26914 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenkel C. D. et al., Diagnostic gene expression biomarkers of coral thermal stress. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14, 667–678 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traylor-Knowles N., Rose N. H., Sheets E. A., Palumbi S. R., Early transcriptional responses during heat stress in the coral Acropora hyacinthus. Biol. Bull. 232, 91–100 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharp V. A., Miller D., Bythell J. C., Brown B. E., Expression of low molecular weight HSP 70 related polypeptides from the symbiotic sea anemone Anemonia viridis Forskall in response to heat shock. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 179, 179–193 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes R. L., King C. M., Induction of 70-kD heat shock protein in scleractinian corals by elevated temperature: Significance for coral bleaching. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 4, 36–42 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weis V. M., Cellular mechanisms of Cnidarian bleaching: Stress causes the collapse of symbiosis. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 3059–3066 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desalvo M. K., Sunagawa S., Voolstra C. R., Medina M., Transcriptomic responses to heat stress and bleaching in the elkhorn coral Acropora palmata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 402, 97–113 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishii Y. et al., Global shifts in gene expression profiles accompanied with environmental changes in cnidarian-dinoflagellate endosymbiosis. G3 (Bethesda) 9, 2337–2347 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansfield K. M. et al., Transcription factor NF-κB is modulated by symbiotic status in a sea anemone model of cnidarian bleaching. Sci. Rep. 7, 16025 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richier S., Rodriguez-Lanetty M., Schnitzler C. E., Weis V. M., Response of the symbiotic cnidarian Anthopleura elegantissima transcriptome to temperature and UV increase. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 3, 283–289 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunagawa S., Choi J., Forman H. J., Medina M., Hyperthermic stress-induced increase in the expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase and glutathione levels in the symbiotic sea anemone Aiptasia pallida. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 151, 133–138 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voolstra C. R. et al., Effects of temperature on gene expression in embryos of the coral Montastraea faveolata. BMC Genomics 10, 627 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barshis D. J. et al., Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1387–1392 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cziesielski M. J. et al., Multi-omics analysis of thermal stress response in a zooxanthellate cnidarian reveals the importance of associating with thermotolerant symbionts. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285, 20172654 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lesser M. P., Oxidative stress in marine environments: Biochemistry and physiological ecology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68, 253–278 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Portune K. J., Voolstra C. R., Medina M., Szmant A. M., Development and heat stress-induced transcriptomic changes during embryogenesis of the scleractinian coral Acropora palmata. Mar. Genomics 3, 51–62 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moya A., Ganot P., Furla P., Sabourault C., The transcriptomic response to thermal stress is immediate, transient and potentiated by ultraviolet radiation in the sea anemone Anemonia viridis. Mol. Ecol. 21, 1158–1174 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seneca F. O., Palumbi S. R., The role of transcriptome resilience in resistance of corals to bleaching. Mol. Ecol. 24, 1467–1484 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuyama I., Ishikawa M., Nozawa M., Yoshida M. A., Ikeo K., Transcriptomic changes with increasing algal symbiont reveal the detailed process underlying establishment of coral-algal symbiosis. Sci. Rep. 8, 16802 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meron D. et al., The algal symbiont modifies the transcriptome of the Scleractinian coral Euphyllia paradivisa during heat stress. Microorganisms 7, 256 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maor-Landaw K., van Oppen M. J. H., McFadden G. I., Symbiotic lifestyle triggers drastic changes in the gene expression of the algal endosymbiont Breviolum minutum (Symbiodiniaceae). Ecol. Evol. 10, 451–466 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez-Lanetty M., Phillips W. S., Weis V. M., Transcriptome analysis of a cnidarian-dinoflagellate mutualism reveals complex modulation of host gene expression. BMC Genomics 7, 23 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganot P. et al., Adaptations to endosymbiosis in a cnidarian-dinoflagellate association: Differential gene expression and specific gene duplications. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002187 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lehnert E. M. et al., Extensive differences in gene expression between symbiotic and aposymbiotic cnidarians. G3 (Bethesda) 4, 277–295 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oakley C. A. et al., Symbiosis induces widespread changes in the proteome of the model cnidarian Aiptasia. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1009–1023 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumgarten S. et al., Evidence for miRNA-mediated modulation of the host transcriptome in cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Mol. Ecol. 27, 403–418 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLachlan R. H., Price J. T., Solomon S. L., Grottoli A. G., Thirty years of coral heat-stress experiments: A review of methods. Coral Reefs 39, 885–902 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weis V. M., Davy S. K., Hoegh-Guldberg O., Rodriguez-Lanetty M., Pringle J. R., Cell biology in model systems as the key to understanding corals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 369–376 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voolstra C. R., A journey into the wild of the cnidarian model system Aiptasia and its symbionts. Mol. Ecol. 22, 4366–4368 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weis V. M., Cell biology of coral symbiosis: Foundational study can inform solutions to the coral reef crisis. Integr. Comp. Biol. 59, 845–855 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schoenberg D. A., Trench R. K., Genetic variation in Symbiodinium (Gymnodinium) microadriaticum Freudenthal, and specificity in its symbiosis with marine invertebrates. III. Specificity and infectivity of Symbiodinium microadriaticum. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 207, 405–427 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belda-Baillie C. A., Baillie B. K., Maruyama T., Specificity of a model cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Biol. Bull. 202, 74–85 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yasuoka Y., Shinzato C., Satoh N., The mesoderm-forming gene brachyury regulates ectoderm-endoderm demarcation in the coral Acropora digitifera. Curr. Biol. 26, 2885–2892 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cleves P. A., Strader M. E., Bay L. K., Pringle J. R., Matz M. V., CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in a reef-building coral. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5235–5240 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cleves P. et al., Reduced thermal tolerance in a coral carrying CRISPR-induced mutations in the gene for a heat-shock transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 28899–28905 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker A. C., Cunning R., “Coral ‘bleaching’ as a generalized stress response to environmental disturbance” in Diseases of Coral, Woodley C. M., Downs C. A., Bruckner A. W., Porter J. W., Galloway S. B., Eds. (Wiley, 2015), pp. 396–409. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szabó M., Larkum A. W. D., Vass I., “A review: The role of reactive oxygen species in mass coral bleaching” in Photosynthesis in Algae: Biochemical and Physiological Mechanisms, Larkum A. W. D., Grossman A. R., Raven J., Eds. (Springer, 2020), pp. 459–488. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Washburn M. P. et al., Protein pathway and complex clustering of correlated mRNA and protein expression analyses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3107–3112 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cleves P. A., Shumaker A., Lee J., Putnam H. M., Bhattacharya D., Unknown to known: Advancing knowledge of coral gene function. Trends Genet. 36, 93–104 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilmore T. D., Wolenski F. S., NF-κB: Where did it come from and why? Immunol. Rev. 246, 14–35 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mansfield K. M., Gilmore T. D., Innate immunity and cnidarian-Symbiodiniaceae mutualism. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 90, 199–209 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bieri T., Onishi M., Xiang T., Grossman A. R., Pringle J. R., Relative contributions of various cellular mechanisms to loss of algae during cnidarian bleaching. PLoS One 11, e0152693 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gomez-Pastor R., Burchfiel E. T., Thiele D. J., Regulation of heat shock transcription factors and their roles in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 4–19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bay L. K. et al., Infection dynamics vary between Symbiodinium types and cell surface treatments during establishment of endosymbiosis with coral larvae. Diversity 3, 356–374 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buerger P. et al., Heat-evolved microalgal symbionts increase coral bleaching tolerance. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2498 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dykens J. A., Shick J. M., Oxygen production by endosymbiotic algae controls superoxide dismutase activity in their animal host. Nature 297, 579–580 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lesser M. P., Stochaj W. R., Tapley D. W., Shick J. M., Bleaching in coral reef anthozoans: Effects of irradiance, ultraviolet radiation, and temperature on the activities of protective enzymes against active oxygen. Coral Reefs 8, 225–232 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Downs C. A., Mueller E., Phillips S., Fauth J. E., Woodley C. M., A molecular biomarker system for assessing the health of coral (Montastraea faveolata) during heat stress. Mar. Biotechnol. 2, 533–544 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Downs C. A. et al., Oxidative stress and seasonal coral bleaching. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33, 533–543 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yakovleva I., Bhagooli R., Takemura A., Hidaka M., Differential susceptibility to oxidative stress of two scleractinian corals: Antioxidant functioning of mycosporine-glycine. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 139, 721–730 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Richier S., Furla P., Plantivaux A., Merle P.-L., Allemand D., Symbiosis-induced adaptation to oxidative stress. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 277–285 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krueger T. et al., Differential coral bleaching-Contrasting the activity and response of enzymatic antioxidants in symbiotic partners under thermal stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 190, 15–25 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gardner S. G. et al., A multi-trait systems approach reveals a response cascade to bleaching in corals. BMC Biol. 15, 117 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tolleter D. et al., Coral bleaching independent of photosynthetic activity. Curr. Biol. 23, 1782–1786 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nii C. M., Muscatine L., Oxidative stress in the symbiotic sea anemone Aiptasia pulchella (Carlgren, 1943): Contribution of the animal to superoxide ion production at elevated temperature. Biol. Bull. 192, 444–456 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lutz A., Raina J.-B., Motti C. A., Miller D. J., van Oppen M. J. H., Host coenzyme Q redox state is an early biomarker of thermal stress in the coral Acropora millepora. PLoS One 10, e0139290 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nielsen D. A., Petrou K., Gates R. D., Coral bleaching from a single cell perspective. ISME J. 12, 1558–1567 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bronstein J. L., The exploitation of mutualisms. Ecol. Lett. 4, 277–287 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pringle E. G., Integrating plant carbon dynamics with mutualism ecology. New Phytol. 210, 71–75 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keeling P. J., McCutcheon J. P., Endosymbiosis: The feeling is not mutual. J. Theor. Biol. 434, 75–79 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones V. A. S., Bucher M., Hambleton E. A., Guse A., Microinjection to deliver protein, mRNA, and DNA into zygotes of the cnidarian endosymbiosis model Aiptasia sp. Sci. Rep. 8, 16437 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hoegh-Guldberg O., Smith G., Influence of the population density of zooxanthellae and supply of ammonium on the biomass and metabolic characteristics of the reef corals Seriatopora hystrix and Stylophora pistillata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 57, 173–186 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dubinsky Z. et al., The effect of external nutrient resources on the optical properties and photosynthetic efficiency of Stylophora pistillata. Proc. Biol. Sci. 239, 231–246 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rees T. A. V., Are symbiotic algae nutrient deficient? Proc. Biol. Sci. 243, 227–233 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Muller-Parker G., McCloskey L. R., Hoegh-Guldberg O., McAuley P. J., Effect of ammonium enrichment on animal and algal biomass of the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Pac. Sci. 48, 273–283 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pogoreutz C. et al., Sugar enrichment provides evidence for a role of nitrogen fixation in coral bleaching. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 3838–3848 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosset S., Wiedenmann J., Reed A. J., D’Angelo C., Phosphate deficiency promotes coral bleaching and is reflected by the ultrastructure of symbiotic dinoflagellates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 118, 180–187 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xiang T. et al., Glucose-induced trophic shift in an endosymbiont dinoflagellate with physiological and molecular consequences. Plant Physiol. 176, 1793–1807 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morris L. A., Voolstra C. R., Quigley K. M., Bourne D. G., Bay L. K., Nutrient availability and metabolism affect the stability of coral-Symbiodiniaceae symbioses. Trends Microbiol. 27, 678–689 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kulkarni A., Anderson A. G., Merullo D. P., Konopka G., Beyond bulk: A review of single cell transcriptomics methodologies and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 58, 129–136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hu M., Zheng X., Fan C.-M., Zheng Y., Lineage dynamics of the endosymbiotic cell type in the soft coral Xenia. Nature 582, 534–538 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sunagawa S. et al., Generation and analysis of transcriptomic resources for a model system on the rise: The sea anemone Aiptasia pallida and its dinoflagellate endosymbiont. BMC Genomics 10, 258 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lehnert E. M., Burriesci M. S., Pringle J. R., Developing the anemone Aiptasia as a tractable model for cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis: The transcriptome of aposymbiotic A. pallida. BMC Genomics 13, 271 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xiang T., Hambleton E. A., DeNofrio J. C., Pringle J. R., Grossman A. R., Isolation of clonal axenic strains of the symbiotic dinoflagellate Symbiodinium and their growth and host specificity. J. Phycol. 49, 447–458 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Krediet C. J. et al., Rapid, precise, and accurate counts of Symbiodinium cells using the Guava flow cytometer, and a comparison to other methods. PLoS One 10, e0135725 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dobin A. et al., STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]