Abstract

Grandparent kinship caregivers may experience increased parenting stress and mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. It may lead to risky parenting behaviors, such as psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors towards their grandchildren. This study aims to examine (1) the relationships between parenting stress, mental health, and grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting practices, such as psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors towards their grandchildren during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (2) whether grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health is a potential mediator between parenting stress and caregivers’ psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors. A cross-sectional survey among grandparent kinship caregivers (N = 362) was conducted in June 2020 in the United States. Descriptive analyses, negative binomial regression analyses, and mediation analyses were conducted using STATA 15.0. We found that (1) grandparent kinship caregivers’ high parenting stress and low mental health were associated with more psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful parenting behaviors during COVID-19; and (2) grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health partially mediated the relationships between parenting stress and their psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors. Results suggest that decreasing grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting stress and improving their mental health are important for reducing child maltreatment risk during COVID-19.

Keywords: Parenting stress, Mental health, Psychological aggression, Corporal punishment, Neglect, Kinship care, Grandparents

Introduction

COVID-19 and its consequences (e.g., sheltering in place, quarantine, child care and school closures, financial instability, and lack of social connections), have produced high levels of parenting stress and psychological distress on caregivers who take care of children across the world (Brooks et al. 2020; World Health Organization 2020). In the United States, data from National Parent Helpline reported that there was a 30% increase in calls about childcare, food and other virus-related stressors since the onset of COVID-19 (Hurt et al. 2020). Prior research has found that economic hardship, lack of social support, increased parenting stress, and mental illness are risk factors for child abuse and neglect (Folger and Wright 2013; Kelley 1992; Mullick et al. 2001; Yang 2015). However, the number of substantiated child abuse and neglect cases reported to the child protective services has decreased during the pandemic due to school closures and interruptions in social services (Bhopal et al. 2020; Martinkevich et al. 2020). Reduced child maltreatment reporting during the pandemic does not indicate children are safe at home (Baron et al. 2020). Risk factors (e.g., economic instability, parenting stress, mental distress) associated with risky parenting behaviors and child maltreatment risk have been identified as being exacerbated by COVID-19 (Jonson-Reid et al. 2020; Humphreys et al. 2020; Wu and Xu 2020). Previous studies conducted during the economic recession and other disasters, such as Hurricanes, suggest child maltreatment risk may be triggered by contextual stressors, particularly among vulnerable and low-income families (Brooks-Gunn et al. 2013; Self-Brown et al. 2013). Grandparent-headed kinship families are unevenly affected by COVID-19 due to their pre-existing vulnerabilities in socioeconomic status and health conditions (Xu et al. 2020), which may increase risk factors associated with child maltreatment risk. Therefore, the current study aims to examine relationships between parenting stress, mental health, and risky parenting behaviors (i.e., psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors) among grandparent kinship caregivers during COVID-19.

Grandparent-Headed Kinship Families

Kinship care is the full-time care of children by relatives or close family friends when their biological parents are unable to take care of their children, and most kinship caregivers are grandparents (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2014). These grandchildren are placed with grandparents when they are maltreated by their biological parents, or when their parents experience some significant life events, such as incarceration, substance abuse, mental illness, intimate partner violence (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2014). In the United States, approximately 2.5 million grandparents, known as grandparent kinship caregivers, are fully responsible for their grandchildren (United States Census Bureau, 2012–2016). Grandparent-headed kinship families are often characterized by low economic status, poor physical and mental health, inadequate housing, and high levels of parenting stress and psychological distress (Lee et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2020).

Parenting Stress among Grandparent Kinship Caregivers

Parenting stress is conceptualized as an “aversive psychological reaction to the demands of being a parent” (Deater-Deckard 1998; p. 315). Several studies have examined parenting stress in kinship care. It is documented that grandparent kinship caregivers experience a high level of parenting stress due to parenting demands and other unique challenges in raising grandchildren during their late adulthood (Kelley et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2016). Prior research has indicated that material hardship, financial stress, physical and mental health problems, lack of social support, and conflicts with biological parents contribute to parenting stress among kinship caregivers (Kelley et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2020; Waldrop and Weber 2001). Moreover, children’s characteristics, such as younger age, physical illness, behavioral problems, and disabilities, have also been associated with kinship caregivers’ increased parenting stress (Kelley et al. 2011).

Parenting Stress and Psychological Aggression, Corporal Punishment, and Neglectful Behaviors

Parenting stress significantly increases caregivers’ risky parenting behaviors, including psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors (Crouch and Behl 2001; Holden and Banez 1996; Lee et al. 2011). Psychological aggression is defined as delivering information to a child that is worthless, unloved, unwanted, or threatened with psychological violence (Hart et al. 1996). Corporal punishment refers to the use of physical punishment that causes a child pain in order to correct or control the child’s behavior (Straus and Donnelly 1993). Neglectful behaviors are defined as those that do not meet a child’s basic needs or rights, and which result in harm to the well-being of the child (Proctor and Dubowitz 2014).

To our knowledge, only one study has examined grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting behaviors. Kaminski et al. (2008) found grandparent kinship caregivers were at a higher risk of using risky parenting behaviors than biological parents when facing parenting challenges. Given the limited understanding of parenting behaviors among grandparent kinship caregivers, we reviewed studies conducted among biological parents. For instance, Crouch and Behl (2001) found a positive correlation between parenting stress and corporal punishment, with the relationship being stronger among parents who believed in the value of corporal punishment. Niu et al. (2018) suggested that parenting stress would intensify caregivers’ corporal punishment and psychological aggression. In terms of neglectful parenting behaviors, Slack et al. (2011) suggested parenting stress was a significant predictor of child neglect risk across studies using different datasets in addition to low family economic status. As evidence indicates that parenting stress increases risky parenting behaviors, and that grandparent kinship caregivers experience significantly higher parenting stress, an understanding of how grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting stress is associated with their risky parenting behaviors is warranted, especially during COVID-19.

Mental Health and Psychological Aggression, Corporal Punishment, and Neglectful Behaviors

Being grandparent kinship caregivers also increases the risk of mental distress (Whitley et al. 2016). Prior research has found that approximately 40% of grandparent kinship caregivers report clinically significant depressive symptoms (Kelley et al. 2013; Lee and Jang 2019). Although we know grandparent kinship caregivers experience mental distress, the relationship between their mental health status and risky parenting behaviors remains less clear. Among studies conducted in biological parents, research indicates that caregivers’ mental illness is a risk factor for risky parenting behaviors and child maltreatment risk (Doidge et al. 2017; Stith et al. 2009). Walsh et al. (2002) found that parents who had mental illness history, such as depression, schizophrenia, antisocial behaviors were more likely to conduct child abuse. Similarly, parents’ depression has been found to contribute to corporal punishment of their children (Lee et al. 2011; Shin and Stein 2008). Likewise, Conron et al. (2009) found that maternal depression was positively associated with mothers’ use of psychological aggression in high-risk families. Slack et al. (2011) also identified parental depression as associated with increased risk for child neglect during early childhood. In the face of COVID-19, grandparent kinship caregivers face elevated mental distress in addition to economic instability and parenting stress (Xu et al. 2020), which may increase the potential to use risky parenting behaviors during this stressful time. Thus, it is critical to examine how grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health is associated with risky parenting behaviors to ensure child safety during COVID-19.

Theoretical Frameworks

The ecological and transactional model suggests risk for child maltreatment is an interactive result of characteristics of the individual, the family, and the context (Belsky 1993). Applying Belsky’s model, at the individual level, children’s (e.g., child’s age, physical and mental health) and caregivers’ attributes (e.g., caregivers’ child maltreatment history, personality, psychological resources) would trigger risky parenting behaviors. At the family level, Belsky’s (1993) model would emphasize the parenting and parent-child interactional processes between caregivers and children. And according to this model, context would be the COVID-19 pandemic. Belsky’s (1993) model provides us an overarching understanding of risk and protective factors contributing to risky parenting behaviors and child maltreatment risk. Family stress theory further illustrates family stressors, such as increased parenting stress during COVID-19, and its association with risky parenting practice via caregivers’ mental distress (Hill 1949). In this study, COVID-19 is treated as a contextual stressor that increases both grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting stress and mental distress, with parenting stress and mental distress further influencing their risky parenting behaviors towards their grandchildren.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Guided by these theoretical frameworks, this study aims to answer two research questions: (1) what are relationships between parenting stress and mental health with grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting behaviors, including psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglect, when controlling for other factors?; and (2) is the relationship between parenting stress and risky parenting behaviors mediated by grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health? Research hypotheses include (1a) increased parenting stress is positively associated with grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting behaviors (i.e., psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors); (1b) better mental health status is negatively associated with grandparent kinship caregivers’ psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors; and (2) grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health mediates the relationships between parenting stress and psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors, respectively.

Methods

Study Procedure

We used an online panel (Qualtrics n.d.), to collect cross-sectional data from grandparent kinship caregivers. Qualtrics panels includes millions of U.S. residents who have agreed to participate in regular research surveys. First, participants were screened to ensure a sample of eligible grandparent kinship caregivers, to determine whether they were currently the primary caregiver of one or more grandchildren. If they responded “Yes,” they were then asked whether at least one of their grandchild’s biological parents lived in the same household with them most of the time. If they replied “No,” they were eligible to continue the survey. Additional inclusion criteria included living in the U.S., born before 1985, and having at least one child residing in the household. If grandparents had more than one grandchild in their household, they were asked to answer questions as applied to their oldest grandchild. A total of 1908 participants answered this survey, but only 19% (N = 362) met our inclusion criteria. Participants who completed surveys were financially compensated by Qualtrics, with the rate (under $14) determined by the Qualtrics team. The data were collected in June 2020. The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Dependent Variables

Psychological Aggression, Corporal Punishment, and Neglectful Behaviors

Psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors were measured by the three subscales of the Conflict Tactics Scales Parent-Child (CTS-PC; Straus et al. 1998). Psychological aggression included items like “I threatened to hit or throw something at him/her” and “I insulted or swore at him/her.” Sample corporal punishment items included “I threatened to spank or hit him/her but did not actually do it” and “I shouted, yelled, or screamed at him/her.” Examples of neglectful behaviors included “I had to leave your child home alone, even when I thought some adult should be with him/her” and “I was not able to make sure my child got the food he/she needed.” In this study, grandparents were asked to recall whether they had engaged in these behaviors towards their grandchildren during the past month. We changed one response option “not in the past year, but it happened before” to “not during COVID-19, but it has happened” to match our study’s context. Thus, following Straus et al.’s (1998) response options, each subscale contained: “never,” “not during COVID-19, but it has happened,” “1 time,” “2 times,” “3–5 times,” “6–10 times,” “11–20 times,” and “more than 20 times.” We added midpoints of response categories answered by participants. In other words, 1 time was counted as 1, 2 times were counted as 2, 3–5 times were counted as 4 times, 6–10 times were counted as 8 times and so forth (Straus et al. 1998). Responses of “not during the pandemic but it happened” were recoded to 0. We used summative scores of these midpoints to count the total numbers of psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors towards grandchildren in May 2020, respectively.

Independent Variable

Parenting Stress

Parent Stress Index was used to assess parenting stress among kinship grandparent caregivers during COVID-19. Abidin (1995) originally developed this scale for parents, but we changed “parents” to “grandparents” and “child” to “grandchild” to fit the present study. The shortened scale included four items, including “Being a grandparent is harder than I thought it would be,” “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a grandparent,” “I find that taking care of my grandchild/ren is much more work than pleasure,” and “I often feel tired, worn out, or exhausted from raising my grandchildren.” The scale ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree) with a reliability of 0.85 in this sample. The average score of these items was used with a higher score indicating more parenting stress.

Mediator

Mental Health

Grandparents’ mental health was measured by the Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) scale, a shorter version of Veit and Ware’s (1983) original scale, which included 38-items. The five items in the shortened version included: “How much of the time during the last month have you (a) been a very nervous person?; (b) felt downhearted and blue?; (c) felt calm and peaceful?; (d) felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up?; and (e) been a happy person?”. The scale ranged from 1 (None of the time) to 6 (All of the time). Three items (a, b, and d) were reverse coded, and an average score was used with a higher score indicating better mental health. The MHI-5 has been used in previous studies among older adults with good reliability (e.g., Trainor et al. 2013; α = 0.78), but the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.59 in this sample.

Control Variables

Child Characteristics

Control variables at the child level included child age (a continuous variable measured by year), child gender (1 = Female and 0 = Male), and child physical (1 = Poor and 5 = Excellent) and mental health (1 = Poor and 5 = Excellent), as reported by the caregiver.

Grandparent Kinship Caregivers’ Characteristics

Eight dummy coded variables (i.e., child abuse and neglect, parental incarceration, parental mental illness, parental death, parental substance abuse, parental intimate partner violence, parental economic needs, and other) were included to describe the reason why the child stayed with grandparent kinship caregivers. Grandparents’ characteristics included their race (1 = Non-White and 0 = White), gender (1 = Female and 0 = Male), marital status (1 = Not married and 0 = Married), household income in 2019 (1 = Less than $ 30,000, 2 = Between $ 30,000 and $ 60,000, and 3 = More than $ 60,000, with Less than $ 30,000 as reference group), education (1 = Below college and 0 = College and above), number of children in the household (1 = One child and 0 = More than one child), years of caring for grandchildren (1 = More than one year and 0 = One year or less), licensed kinship caregivers (1 = Yes and 0 = No), and labor force status (1 = Full-time, 2 = Part-time, and 3 = Don’t work because of retirement, with working full time as reference group). For grandparents who worked full-time or part-time prior to COVID-19, losing jobs during COVID-19 was coded as 1; for grandparents who did not lose jobs or did not work because of retirement prior to COVID-19, it was coded as 0. Grandparent’s age was measured by year as a continuous variable, with their physical health (1 = Poor and 5 = Excellent) treated as a continuous variable. Grandparents’ household material hardship was measured by seven dichotomous questions (1 = Yes and 0 = No) asking about their food insecurity, housing instability, inability to pay the mortgage, disconnected telephone services and internet services, and medical hardship during COVID-19 (The Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing 2018). We used a summative score (ranging from 0 to 7; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74) of the seven types of material hardships as a continuous variable with a higher score indicating more material hardship during COVID-19. Grandparent kinship caregivers’ social support was measured by eight questions with a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = I get much less than I would like and 5 = I get as much as I like) using the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (Broadhead et al. 1989). An average score was used with higher scores indicating more social support, and the reliability for this scale was 0.93 in this study.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses, negative binomial regression analyses, and mediation analyses were conducted using STATA 15.0 (StataCorp 2017). Negative binomial regression analyses were performed because psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors were of a count nature and over dispersed at the left tail of the distribution. We did not use Poisson regression because our data did not meet the assumptions of Poisson regression to have an equal mean and variance (Gardner et al. 1995). A series of negative binomial regression models were performed to examine associations between parenting stress, mental health, and grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting behaviors.

To examine the mediating role of grandparent’s mental health, three mediation analyses were conducted for psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors, respectively. Following Baron and Kenny (1986), we conducted mediation models using PARAMED package in STATA, which accommodated the nature of count dependent variables and a continuous mediator (Emsley and Liu 2013). Bootstrapping estimation was used to further examine the mediational effect of grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health on these relationships.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of the sample. The sample included 362 grandparent caregivers. The average scores for grandparents’ psychological aggression, corporal punishment, neglectful behaviors, parenting stress and mental health were 10.96 (SD = 20.10) out of 100, 7.87 (SD = 19.43) out of 98, 8.05 (SD = 19.39) out of 95, 2.30 (SD = 0.82) out of 4 and 3.97(SD = 1.01) out of 6, respectively. The most common reason for grandparents to take care of their grandchildren was parental economic needs (33%), followed by parental substance abuse (17%), parental death (9%), parental mental illness (8%), child abuse and neglect (7%; see Table 1 for other trigger events).

Table 1.

Descriptive results (N = 362)

| N | %/Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

| Psychological aggression | 362 | 10.96 (20.10) | 0–100 |

| Corporal punishment | 362 | 7.87 (19.43) | 0–98 |

| Neglect | 362 | 8.05 (19.39) | 0–95 |

| Independent variable | |||

| Parenting stress | 362 | 2.30 (0.82) | 1–4 |

| Mediator | |||

| Mental health | 362 | 3.97 (1.01) | 1.4–6 |

| Control variables | |||

| Trigger event | |||

| Child abuse and neglect | 26 | 7.18% | |

| Parental incarceration | 18 | 4.97% | |

| Parental mental illness | 29 | 8.01% | |

| Parental death | 34 | 9.39% | |

| Parental substance abuse | 62 | 17.13% | |

| Parental intimate partner violence | 20 | 5.52% | |

| Parental economic needs | 122 | 33.70% | |

| Other | 51 | 14.09% | |

| Grandparent race | |||

| White | 246 | 68.72% | |

| Non-White | 112 | 31.28% | |

| Grandparent gender | |||

| Male | 136 | 37.57% | |

| Female | 226 | 62.43% | |

| Grandparent age | 362 | 56.5 (7.75) | 42–90 |

| Grandparent marital status | |||

| Married | 252 | 69.61% | |

| Other | 110 | 30.39% | |

| Grandparent household income in 2019 | |||

| ≤30,000 | 103 | 29.28% | |

| 30,000 - ≤60,000 | 135 | 37.29% | |

| >60,000 | 121 | 33.43% | |

| Material hardship | 362 | 1.62 | 0–7 |

| Grandparent education | |||

| Below college | 218 | 60.22% | |

| College and above | 144 | 39.78% | |

| Grandparent physical health | 361 | 3.48 (1.01) | 1–5 |

| Number of children in the household | |||

| One child | 64 | 17.68% | |

| More than one child | 298 | 82.32% | |

| Years of care | |||

| One year or less than one year | 77 | 19.15% | |

| More than one year | 325 | 80.85% | |

| Licensed kinship caregivers | |||

| Yes | 143 | 39.61% | |

| No | 218 | 60.39% | |

| Labor force status | |||

| Full time | 157 | 43.37% | |

| Part time | 83 | 22.93% | |

| Don’t work | 122 | 33.70% | |

| Lost job | |||

| Yes | 82 | 22.71% | |

| No | 279 | 77.29% | |

| Social support | 362 | 3.36 (1.11) | 1–5 |

| Child age | 358 | 9.53 (4.68) | 0–19 |

| Child gender | |||

| Male | 195 | 54.02% | |

| Female | 166 | 45.98% | |

| Child physical health | 362 | 4.45 (0.74) | 1–5 |

| Child mental health | 362 | 4.25 (0.96) | 1–5 |

In terms of grandparents’ demographic characteristics, the average age of grandparents was 56.5 (SD = 7.75) years old. Among the grandparents, about 70% were White, more than two-thirds (70%) were married, and 60% had an educational level below college. In terms of their household income in 2019, 29% had income less than $30,000, 37% had income between $30,000 to $60,000, and 34% had income more than $60,000. Most grandparents took care of more than one child (82%), and about 80% of them had provided care for more than one year. About 67% of grandparents worked full-time or part-time prior to COVID-19, and almost a quarter (23%) lost their jobs during the pandemic. On average, they experienced 1.62 types of material hardship out of 7, and the average score for social support was 3.36 out of 5. In terms of child characteristics, the average age was 9.53 (SD = 4.68) years old. More than half (54%) were male, and the average scores for child physical health and mental health were 4.45 and 4.25 out of 5, respectively.

Factors Associated with Psychological Aggression, Corporal Punishment, and Neglectful Behaviors

Table 2 presents six negative binomial regression models predicting psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Models 1, 3, and 5 did not include grandparents’ mental health variable, while models 2, 4, and 6 included grandparents’ mental health as a predictor. Results with grandparents’ mental health were only interpreted (Models 2, 4, and 6). Across all models, parenting stress was positively associated with increased psychological aggression (B = 0.99, p < 0.001), corporal punishment (B = 1.23, p < 0.001), and neglectful behaviors (B = 0.93, p < 0.001). Similarly, grandparent kinship caregivers’ better mental health status was negatively associated with psychological aggression (B = −0.47, p < 0.01), corporal punishment (B = −0.54, p < 0.01) and neglectful behaviors (B = −0.67, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Negative binomial regression results (N = 350)

| Psychological aggression | Corporal punishment | Neglect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| B | B | B | B | B | B | |

| Independent variable | ||||||

| Parenting stress | 1.17*** | 0.99*** | 1.39*** | 1.23*** | 1.18*** | 0.93*** |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Mental health | – | −0.47** | – | −0.54** | – | −0.67*** |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Trigger event (ref. child abuse and neglect) | ||||||

| Parental incarceration | −0.35 | −0.15 | −1.78 | −1.69 | −2.20* | −1.92* |

| Parental mental illness | −1.19* | −1.36* | −1.18 | −1.27 | −2.12* | −2.27** |

| Parental death | −1.02 | −0.92* | −1.08 | −0.85 | −1.33 | −1.81* |

| Parental substance abuse | −0.73 | −0.86 | −1.49* | −1.46* | −2.00** | −2.30** |

| Parental intimate partner violence | −1.36* | −1.42* | −2.54** | −2.62** | −2.20** | −2.60** |

| Parental economic needs | −0.79 | −0.79 | −0.91 | −0.90 | −1.19 | −1.32* |

| Other | −0.75 | −0.88* | −0.81 | −0.91 | −1.59* | −1.92** |

| Grandparent race (ref. White) | ||||||

| Non-White | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.31 | −0.24 | −0.06 |

| Grandparent gender (ref. Male) | ||||||

| Female | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| Grandparent age | 0.04* | 0.05** | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Grandparent marital status (ref. Married) | ||||||

| Not married | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.79 | −0.82 | −0.42 | −0.41 |

| Grandparent household income (ref. ≤30,000) | ||||||

| 30,000 - ≤60,000 | −0.07 | −0.26 | −0.44 | −0.54 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| >60,000 | −0.45 | −0.47 | −1.05* | −1.00* | −0.07 | −0.09 |

| Material hardship | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.39*** | 0.34** |

| Grandparent education (ref. College and above) | ||||||

| Below college | 0.15 | 0.14 | −0.49 | −0.41 | −0.80* | −0.65 |

| Grandparent physical health | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Number of children in the household (ref. one child) | ||||||

| More than one child | −0.14 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.19 | −0.12 | −0.23 |

| Years of care (ref. ≤ one year) | ||||||

| More than one year | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.35 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Licensed kinship caregivers (ref. No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.60** | 0.50 | 1.47*** | 1.38** | 2.12*** | 1.75*** |

| Labor force status (ref. Full time) | ||||||

| Part time | −1.20*** | −1.29* | −1.40** | −1.49** | −1.08* | −0.99* |

| Don’t work | −0.43 | −0.49 | −1.43* | −1.39* | −0.30 | −0.30 |

| Lost job (ref. No) | ||||||

| Yes | −0.18 | −0.30 | −0.27 | −0.17 | −0.14 | −0.07 |

| Social support | −0.25* | −0.09 | −0.19 | 0.01 | −0.18 | 0.08 |

| Child age | −0.11** | −0.14*** | −0.19*** | −0.21*** | −0.12* | −0.15** |

| Child gender (ref. Male) | ||||||

| Female | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.71 | −0.64 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| Child physical health | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.25 | −0.32 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| Child mental health | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.25 | −0.20 | −0.10 | 0.04 |

| Model fit | ||||||

| AIC | 1902.25 | 2036.98 | 1301.67 | 1417.12 | 1262.06 | 1212.50 |

| BIC | 2017.98 | 2044.67 | 1417.67 | 1424.84 | 1377.79 | 1328.33 |

Models 1, 3, 5 did not include mental health as a predictor. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Across models 2, 4, and 6, several significant covariates were associated with grandparents’ risky parenting behaviors, including: parental intimate partner violence compared to child abuse and neglect (psychological aggression: B = −1.42, p < 0.05; corporal punishment: B = −2.62, p < 0.01; neglect: B = −2.60, p < 0.01), working part time compared to full time (psychological aggression: B = −1.29, p < 0.05; corporal punishment: B = −1.49, p < 0.01; neglect: B = −0.99, p < 0.05), and child age (psychological aggression: B = −0.14, p < 0.001; corporal punishment: B = −0.21, p < 0.001; neglect: B = −0.15, p < 0.01).

However, some factors were significantly associated with different parenting behaviors. Several significant covariates were only associated with psychological aggression (see Model 2), including parental mental illness (B = −1.36, p < 0.05), parental death (B = −0.92, p < 0.05), other trigger (B = −0.88, p < 0.05), and grandparent’s older age (B = 0.05, p < 0.01). In terms of corporal punishment, results showed that parental substance abuse (B = −1.46, p < 0.05), having household income > $ 60,000 (B = −1.00, p < 0.05), licensure status (B = 1.38, p < 0.01), not in the labor force (B = −1.39, p < 0.05) were associated with corporal punishment (see Model 4). Results showed that material hardship was solely associated with neglectful behaviors (B = 0.34, p < 0.01; see Model 6), but not with psychological aggression and corporal punishment. Among different trigger events, a number of trigger events were less likely to be associated with grandparents’ neglectful behaviors compared to child maltreatment. These trigger events included parental incarceration (B = −1.92, p < 0.05), parental mental illness (B = −2.27, p < 0.01), parental death (B = −1.81, p < 0.05), parental substance abuse (B = −2.30, p < 0.01), parental economic needs (B = −1.32, p < 0.05), and other (B = −1.92, p < 0.01). Differently, grandparents’ kinship licensure status (B = 1.75, p < 0.001) was positively associated with increased neglectful behaviors.

Mediation by Mental Health

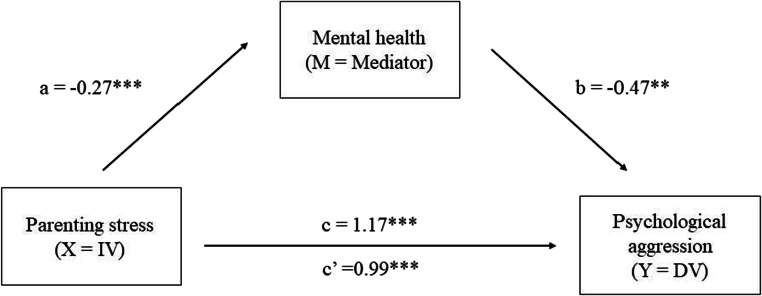

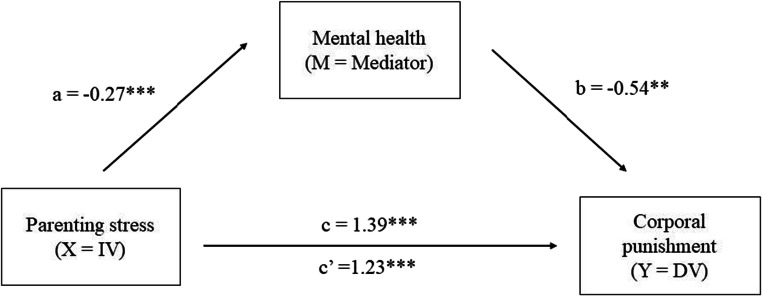

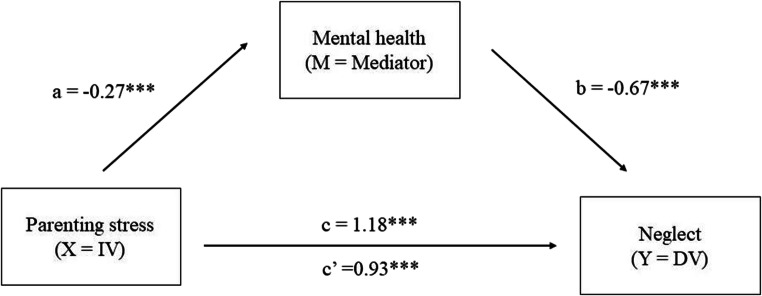

Our results indicated that mental health partially mediated relationships between parenting stress and psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglect behaviors, respectively. Figures 1, 2, and 3 present the results of the mediational models. Parenting stress was a significant predictor of grandparents’ mental health (B = −0.27, p < 0.001; see path a in Figures 1, 2, and 3) with the same coefficient across three mediational models. Other coefficients were different across models, which are presented separately as follows.

Fig. 1.

Mental health mediates the relationship between parenting stress and psychological aggression. Note: path a = Independent variable (IV) to Mediator (M), path b = direct effect of M on dependent variable (DV) while controlling for X, path c = total effect of IV on DV, path c’ = direct effect of IV on DV while controlling for M. All the covariates were controlled in this model. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001

Fig. 2.

Mental health mediates the relationship between parenting stress and corporal punishment. Note: path a = Independent variable (IV) to Mediator (M), path b = direct effect of M on dependent variable (DV) while controlling for X, path c = total effect of IV on DV, path c’ = direct effect of IV on DV while controlling for M. All the covariates were controlled in this model. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001

Fig. 3.

Mental health mediates the relationship between parenting stress and neglect. Note: path a = Independent variable (IV) to Mediator (M), path b = direct effect of M on dependent variable (DV) while controlling for X, path c = total effect of IV on DV, path c’ = direct effect of IV on DV while controlling for M. All the covariates were controlled in this model. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001

Psychological Aggression

Figure 1 shows parenting stress was a significant predictor of grandparent kinship caregivers’ psychological aggression (B = 1.17, p < 0.001) (path c, Fig. 1), and grandparents’ mental health was found to be a significant predictor for psychological aggression (B = −0.47, p < 0.01) (path b, Fig. 1), controlling for parenting stress. When grandparents’ mental health was included as a control variable, the strength of the relationship between parenting stress and psychological aggression was reduced (B = 0.99, p < 0.001), indicating that grandparents’ mental health was a partial mediator (path c’, Fig. 1). Bootstrapping results confirmed a significant indirect effect of mental health on this relationship (p = 0.007), and 39.50% of the relationship was mediated by grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health.

Corporal Punishment

Similar mediation results were found in the relationships between parenting stress, mental health, and corporal punishment (See Fig. 2). Parenting stress was a significant predictor of grandparents’ corporal punishment (B = 1.39, p < 0.001) (path c, Fig. 2), and grandparents’ mental health was also a significant predictor of corporal punishment (B = −0.54, p < 0.01), controlling for parenting stress (path b, Fig. 2). When grandparents’ mental health was included as a control variable, the strength of the relationship between parenting stress and corporal punishment was reduced (B = 1.23, p < 0.001), indicating that grandparents’ mental health was a partial mediator (path c, Fig. 2). Bootstrapping results confirmed a significant indirect effect of mental health on this relationship (p = 0.044), and 44.13% of the relationship was mediated by grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health.

Neglectful Behaviors

Not surprisingly, similar mediation effects were identified, as shown in Fig. 3. Parenting stress was a significant predictor of neglect (B = 1.18, p < 0.001) (path c, Fig. 3), and grandparents’ mental health was a significant predictor of neglect (B = −0.67, p < 0.001) (path b, Fig. 3), controlling for parenting stress. The strength of the relationship between parenting stress and neglect also was reduced (B = 0.93, p < 0.001) when grandparents’ mental health was included as a control variable, which indicates that grandparents’ mental health was a partial mediator (path c, Fig. 3). Bootstrapping results confirmed a significant indirect effect of mental health on this relationship (p = 0.012), and 51.67% of the relationship was mediated by grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health.

Discussion

Our findings support our research hypotheses and contribute to the literature by first examining the relationships between parenting stress and mental health, and risky parenting behaviors, including psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors, among grandparent kinship caregivers, and by second, exploring the mediating role of mental health in these relationships during COVID-19. Since the onset of COVID-19, grandparent kinship caregivers may have experienced job loss, have had to balance work responsibilities and childcare duties, and spend more time staying in the same household with their grandchildren. All these challenges contribute to parenting stress and mental distress (Xu et al. 2020). Our findings also indicate that grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting stress and mental distress are associated with elevated psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglect towards their grandchildren, which is in line with previous findings among biological parents (Casady and Lee 2002; Holden and Banez 1996; Lee 2013; Liu and Wang 2015; Slack et al. 2011).

Our study also highlights the mediating role of grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental health in relationships between parenting stress and psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors. This mechanism is aligned with the family stress theory (Hill 1949), which posits that in the face of stressful situations, grandparent kinship caregivers might assess stressors first and then interpret stressful events (Hill 1949). If they feel anxious, depressed, and frustrated, their mental well-being would affect their abilities to cope with stressful events appropriately (Kwok and Wong 2000), which may result in risky parenting behaviors towards their grandchildren (Hill 1949; Taylor and Stanton 2007).

Furthermore, our findings identify different factors associated with psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglectful behaviors. Our results suggest that older grandparents are more likely to use psychological aggression. This may be because the COVID-19 pandemic may bring additional stress to older grandparents in dealing with economic, mental, and physical challenges, and these challenges contribute to increased use of psychological aggression. In addition, results indicate that licensed grandparent kinship caregivers are more likely to use corporal punishment and neglectful behaviors towards their grandchildren compared to their unlicensed counterparts. It is very likely that licensed grandparent kinship caregivers have involvement with the public child welfare system, and might be more vulnerable in socioeconomic status than those who are not involved in the public system as social services target the most vulnerable population (Swann and Sylvester 2006). This vulnerability could increase parenting stress and mental distress, which contributes to risky parenting behaviors. The other possible explanation is that children with licensed caregivers may have more behavioral problems than those in the care of unlicensed caregivers due to severe childhood traumatic experiences (Starr et al. 1999), which might trigger risky parenting practice. We also found that family economic hardship (e.g., low household income, experiencing material hardship) was associated with the use of corporal punishment or neglectful behaviors, which is consistent with previous literature (Cuartas et al. 2019; Kobulsky et al. 2019; Slack et al. 2011; Yang 2015). But even when families experience economic hardship, we cannot overlook the importance of parental well-being in preventing child physical abuse and neglect.

Our study also found that certain predictors, including trigger events, grandparent kinship caregivers’ labor force status, and child age, similarly predict all three types of risky parenting behaviors. Results show that the trigger event for children raised by grandparents due to child abuse and neglect is associated with their grandparents’ higher likelihood to practice parenting inappropriately than other trigger events. It is possible that there is an intergenerational transmission of parenting attitudes and practices in families with child maltreatment history (Niu et al. 2018). In addition, compared to grandparent kinship caregivers who work full-time, grandparents working part-time are less likely to use psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and neglect children, which suggests that working full-time and meeting family needs during the pandemic adds parenting stress and mental distress to grandparent kinship caregivers. Child age is another significant factor that is associated with all three types of grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting behaviors. The results suggest that grandparents who raised older children have fewer risky parenting behaviors than those who raised younger children. The developmental stage of younger children requires grandparents’ intensive mental and physical involvement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, younger children may need more grandparents’ involvement in meeting their basic needs (e.g., food, clothes, sleeping) and facilitating daily activities (e.g., reading, playing) than that for older children. Given that online learning has become a primary learning mode for children during the pandemic, younger children need more technical assistance (e.g., using computers to log in and log off different online courses) from grandparents than that for older children. All these challenges and parenting demands contribute to stress that grandparent kinship caregivers may experience, which further leads to their risky parenting practice.

Limitations

This study advances our knowledge of grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting behaviors during COVID-19, but several limitations should be noted when interpreting findings. First, this study used a convenience sampling strategy via Qualtrics panels to collect data from grandparent kinship caregivers. Thus, the generalizability of the findings is limited because results may not be able to generalize to those grandparents who were not included in Qualtrics panels database and had limited access to the internet. Furthermore, grandparents who experienced high levels of stress and poor mental health might not participate in this study. Second, this study used cross-sectional data; therefore, no causal inferences among relationships between parenting stress, mental health, and parenting behaviors can be made. Third, we replied on grandparent kinship caregivers’ self-report data of parenting stress, mental health, and parenting behaviors. Due to social desirability, caregivers might underestimate their parenting stress, mental distress, and risky parenting behaviors. Also, data were collected during the pandemic time, and no previous data were available to examine the effect of the COVID-19 on parenting behaviors. Lastly, MHI-5 had relatively low reliability in this study, which might affect the accuracy in capturing grandparent kinship caregivers’ mental well-being.

Implications for Practice and Research

Despite limitations, the study has important implications for improving grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting practice and mental well-being, and for ensuring child safety. First, brief interventions that address parenting stress and mental health issues could be provided to grandparent kinship caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. As we are practicing social distancing during the pandemic, we should deliver interventions creatively. For example, interventions can be provided through the internet, phone calls, or other apps, but technical assistance should be provided given grandparent kinship caregivers may have low digital literacy (Charalambides 2019). It would also be beneficial to provide self-care guidance to keep mentally healthy and to provide coping strategies to manage stress. Also, positive parenting strategies should be promoted widely through television programs, social media, schools, and social services agencies during the pandemic. To prevent child neglect, extra financial supports should be provided to grandparents to address economic hardship in addition to parenting stress and mental distress during the pandemic. Providing financial supports to needy grandparents through fundraising, building family and friends support groups, and helping grandparents navigate or access social services and additional resources would be necessary. Easily accessible educational programs should be developed and provided to grandparents to help them understand COVID-19 better and cope with COVID-19 related stressors effectively. Given the mediating role of mental health in the relationship between parenting stress and risky parenting behaviors, quick mental health screening should be implemented. More accessible mental health services (e.g., counseling) should be offered to grandparent kinship caregivers. The timely treatment of grandparents’ mental distress could help decrease parenting stress and increase effectiveness of parenting practice. Our findings also suggest we should target more vulnerable grandparent kinship caregivers who need more support, such as those who are female, licensed, full-time or part-time workers, of low-income, and raising younger children. In the long-term, more evidence-based and tailored parenting programs should be provided to grandparent kinship caregivers (Kirby 2015; Kirby and Sanders 2014). As child maltreatment has negative effects on children, child welfare workers could conduct home visiting programs virtually or in-person with safety measures to ensure child safety at home. If suspected child maltreatment is detected, services could be provided to grandparents and children virtually or in-person with safety measures.

In terms of future studies, researchers could collect multiple wave data to examine long-term effects of COVID-19 on grandparent kinship caregivers’ parenting stress and their parenting behaviors. Future research could use qualitative methods to gain a deeper understanding of grandparents’ parenting stress and behaviors by race/ethnicity, gender, age, and licensure status. Our nuanced understanding of licensure status suggests that more research is needed to understand the relationship of licensure status with parenting behaviors and the well-being of grandparents and their grandchildren. Future studies could also investigate whether grandparent kinship caregivers’ coping strategies, family resources, social support, and the availability of and access to social services would moderate the relationships between parenting stress, mental health, and parenting behaviors. Also, it would be valuable to examine the effects of parenting practices on grandchildren’s outcomes (e.g., educational, physical and mental health outcomes) during the pandemic. The effectiveness of various interventions to support grandparent kinship caregivers, if implemented, should also be evaluated.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of South Carolina College of Social Work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress inventory. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, E. J., Goldstein, E. G., & Wallace, C. T. (2020). Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. Journal of Public Economics. 10.2139/ssrn.3601399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(3):413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal, S., Buckland, A., McCrone, R., Villis, A. I., & Owens, S. (2020). Who has been missed? Dramatic decrease in numbers of children seen for child protection assessments during the pandemic. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319783 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, DeGruy FV, Kaplan BH. Functional versus structural social support and health care utilization in a family medicine outpatient practice. Medical Care. 1989;27(3):221–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Schneider W, Waldfogel J. The great recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(10):721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casady MA, Lee RE. Environments of physically neglected children. Psychological Reports. 2002;91:711–721. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.3.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambides, A. (2019). Promoting digital literacy and active ageing for senior citizens: The GRANKIT project–grandparents and grandchildren keep in touch. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b8d0/70dc0ea57b1a39e69007905826cf0839b020.pdf

- Child Welfare Information Gateway (2014). About kinship care. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/outofhome/kinship/about/

- Conron KJ, Beardslee W, Koenen KC, Buka SL, Gortmaker SL. A longitudinal study of maternal depression and child maltreatment in a national sample of families investigated by child protective services. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(10):922–930. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JL, Behl LE. Relationships among parental beliefs in corporal punishment, reported stress, and physical child abuse potential. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(3):413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuartas J, Grogan-Kaylor A, Ma J, Castillo B. Civil conflict, domestic violence, and poverty as predictors of corporal punishment in Colombia. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;90:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5(3):314–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doidge JC, Higgins DJ, Delfabbro P, Segal L. Risk factors for child maltreatment in an Australian population-based birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;64:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley, R., & Liu, H. (2013). PARAMED: Stata module to perform causal mediation analysis using parametric regression models. https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s457581.htm

- Folger SF, Wright MOD. Altering risk following child maltreatment: Family and friend support as protective factors. Journal of Family Violence. 2013;28(4):325–337. doi: 10.1007/s10896-013-9510-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118(3):392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.N., Brassard, M.R., & Karlson, H.C. (1996). Psychological maltreatment. In Briere, J. E., Berliner, L. E., Bulkley, J. A., Jenny, C. E., & Reid, T. E (Eds.). The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (pp. 72–89). Sage.

- Hill, R. (1949). Families under stress: Adjustment to the crises of war separation and Reunion. Harper & Brothers.

- Holden EW, Banez GA. Child abuse potential and parenting stress within maltreating families. Journal of Family Violence. 1996;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02333337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;145(4):e20200982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt, S., Ball, A., & Wedell, K (2020, Mar) Children more at risk for abuse and neglect amid coronavirus pandemic, experts say. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2020/03/21/coronavirus-pandemic-could-become-child-abuse-pandemic-experts-warn/2892923001/

- Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B., Cobetto, C., & Ocampo, M. (2020). Child abuse prevention month in the context of COVID-19. https://cicm.wustl.edu/child-abuse-prevention-month-in-the-context-of-covid-19.

- Kaminski PL, Hayslip B, Jr, Wilson JL, Casto LN. Parenting attitudes and adjustment among custodial grandparents. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2008;6(3):263–284. doi: 10.1080/15350770802157737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ. Parenting stress and child maltreatment in drug-exposed children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(3):317–328. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90042-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley D, Sipe TA, Yorker BC. Psychological distress in grandmother kinship care providers: The role of resources, social support, and physical health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(3):311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. Behavior problems in children raised by grandmothers: The role of caregiver distress, family resources, and the home environment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(11):2138–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. Psychological distress in African American grandmothers raising grandchildren: The contribution of child behavior problems, physical health, and family resources. Research in Nursing and Health. 2013;36(4):373–385. doi: 10.1002/nur.21542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN. The potential benefits of parenting programs for grandparents: Recommendations and clinical implications. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(11):3200–3212. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0123-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN, Sanders MR. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a parenting program designed specifically for grandparents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;52:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobulsky, J. M., Dubowitz, H., & Xu, Y. (2019). The global challenge of the neglect of children. Child Abuse & Neglect., 104296. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104296. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kwok SYCL, Wong D. Mental health of parents with young children in Hong Kong: The roles of parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy. Child and Family Social Work. 2000;5(1):57–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2206.2000.00138.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ. Paternal and household characteristics associated with child neglect and child protective services involvement. Journal of Social Service Research. 2013;39(2):171–187. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2012.744618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y., & Jang, K. (2019). Mental health of grandparents raising grandchildren: Understanding predictors of grandparents’ depression. Innovation in Aging, 3(Supplement 1), S282-S282. 10.1093/geroni/igz038.1042

- Lee SJ, Perron BE, Taylor CA, Guterman NB. Paternal psychosocial characteristics and corporal punishment of their 3-year-old children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(1):71–87. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Clarkson-Hendrix M, Lee Y. Parenting stress of grandparents and other kin as informal kinship caregivers: A mixed methods study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;69:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wang M. Parenting stress and harsh discipline in China: The moderating roles of marital satisfaction and parent gender. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;43:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinkevich, P., Larsen, L. L., Græsholt-Knudsen, T., Hesthaven, G., Hellfritzsch, M. B., Petersen, K. K., ... & Rölfing, J. D. (2020). Physical child abuse demands increased awareness during health and socioeconomic crises like COVID-19: A review and education material. Acta Orthopaedica, 1–7. 10.1080/17453674.2020.1782012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mullick M, Miller LJ, Jacobsen T. Insight into mental illness and child maltreatment risk among mothers with major psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(4):488–492. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Liu L, Wang M. Intergenerational transmission of harsh discipline: The moderating role of parenting stress and parent gender. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018;79:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor LJ, Dubowitz H. Child neglect: Challenges and controversies. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. (n.d.). Online panels. https://www.qualtrics.com/support/survey-platform/sp-administration/brand-customization-services/purchase-respondents/

- Self-Brown S, Anderson P, Edwards S, McGill T. Child maltreatment and disaster prevention: A qualitative study of community agency perspectives. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013;14(4):401–407. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.2.16206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DW, Stein MA. Maternal depression predicts maternal use of corporal punishment in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2008;49(4):573–580. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Berger LM, DuMont K, Yang MY, Kim B, Ehrhard-Dietzel S, Holl JL. Risk and protective factors for child neglect during early childhood: A cross-study comparison. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(8):1354–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, R. H., Dubowitz, H., Harrington, D., & Feigelman, S. (1999). Behavior problems of teens in kinship care: Cross-informant reports. In R. L. Hegar & M. Scannapieco (Eds.), Kinship foster care: Policy, practice, research (pp. 193–207). Oxford University Press.

- StataCorp . Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, Som A, McPherson M, Dees JEMEG. Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(1):13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Donnelly DA. Corporal punishment of adolescents by American parents. Youth & Society. 1993;24(4):419–442. doi: 10.1177/0044118X93024004006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann CA, Sylvester M. Does the child welfare system serve the neediest kinship care families? Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28(10):1213–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Stanton AL. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing (2018). 9.4. Scale material hardship. https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/sites/fragilefamilies/files/year_1_guide.pdf#page=22

- Trainor K, Mallett J, Rushe T. Age related differences in mental health scale scores and depression diagnosis: Adult responses to the CIDI-SF and MHI-5. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;151(2):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2012-2016). Grandparents as caregivers. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/grandparents/

- Veit CT, Ware JE. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(5):730–742. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop DP, Weber JA. From grandparent to caregiver: The stress and satisfaction of raising grandchildren. Families in Society. 2001;82(5):461–472. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, MacMillan H, Jamieson E. The relationship between parental psychiatric disorder and child physical and sexual abuse: Findings from the Ontario health supplement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley DM, Kelley SJ, Lamis DA. Depression, social support, and mental health: A longitudinal mediation analysis in African American custodial grandmothers. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2016;82(2–3):166–187. doi: 10.1177/0091415015626550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak, 18 March 2020 (No. WHO/2019-nCoV/MentalHealth/2020.1). World Health Organization.

- Wu, Q., & Xu, Y. (2020). Parenting stress and risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A family stress theory-informed perspective. Developmental Child Welfare, 1-17. 10.1177/2516103220967937.

- Xu, Y., Wu, Q., Levkoff, S., & Jedwab, M. (2020). Material hardship and parenting stress during the COVID-19 pandemic among grandparent kinship providers: The mediating role of grandparents’ mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect., 104700. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang MY. The effect of material hardship on child protective service involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;41:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]