Abstract

Background

In December 2019, COVID-19 emerged and rapidly spread worldwide. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is high; as a result, countries worldwide have imposed rigorous public health measures, such as quarantine. This has involved the suspension of medical school classes globally. Medical school attachments are vital to aid the progression of students’ confidence and competencies as future physicians. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, medical schools have sought ways to replace medical placements with virtual clinical teaching.

Objective

The objective of this study was to review the advantages and disadvantages of virtual medical teaching for medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the current emerging literature.

Methods

A brief qualitative review based on the application and effectiveness of virtual teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted by referencing keywords, including medical student virtual teaching COVID-19, virtual undergraduate medical education, and virtual medical education COVID-19, in the electronic databases of PubMed and Google Scholar. A total of 201 articles were found, of which 34 were included in the study. Manual searches of the reference lists of the included articles yielded 5 additional articles. The findings were tabulated and assessed under the following headings: summary of virtual teaching offered, strengths of virtual teaching, and weaknesses of virtual teaching.

Results

The strengths of virtual teaching included the variety of web-based resources available. New interactive forms of virtual teaching are being developed to enable students to interact with patients from their homes. Open-access teaching with medical experts has enabled students to remain abreast of the latest medical advancements and to reclaim knowledge lost by the suspension of university classes and clinical attachments. Peer mentoring has been proven to be a valuable tool for medical students with aims of increasing knowledge and providing psychological support. Weaknesses of virtual teaching included technical challenges, confidentiality issues, reduced student engagement, and loss of assessments. The mental well-being of students was found to be negatively affected during the pandemic. Inequalities of virtual teaching services worldwide were also noted to cause differences in medical education.

Conclusions

In the unprecedented times of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical schools have a duty to provide ongoing education to medical students. The continuation of teaching is crucial to enable the graduation of future physicians into society. The evidence suggests that virtual teaching is effective, and institutions are working to further develop these resources to improve student engagement and interactivity. Moving forward, medical faculties must adopt a more holistic approach to student education and consider the mental impact of COVID-19 on students as well as improve the security and technology of virtual platforms.

Keywords: virtual teaching, medical student, medical education, COVID-19, review, virus, pandemic, quarantine

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared to be a global health emergency by the World Health Organization on January 30, 2020 [1]. The first reported cases of COVID-19 originated from Wuhan City, Hubei Province, in China during the month of December 2019 [1]. Since then, despite stringent global containment measures, including quarantine, testing, and social distancing, the worldwide incidence of COVID-19 has increased rapidly, with a global death toll of 360,679 as of May 29, 2020 [2]. COVID-19 is caused by the novel betacoronavirus SARS-CoV-2; the most common clinical features of the disease include fever, dry cough, chest tightness, and dyspnea [3]. At present, patients with COVID-19 are only treated with supportive care due to the limited use of antiviral drugs [3].

Undoubtedly, one of the countries most affected by COVID-19 is the United Kingdom [2]. As of May 27, 2020, the United Kingdom had reported 268,619 confirmed cases and 37,542 deaths [2]. The public health measures enforced by the UK government center around household isolation [4]. Through government websites and daily televised COVID-19 updates from officials, messages of isolation were reinforced, including staying at home as much as possible, working from home if able, limiting contact with people outside one’s household, and social distancing by remaining two meters apart from others [4].

The impact of COVID-19 on medical education has been substantial. Medical school attachments often require considerable clinical exposure; however, due to the risk of contracting COVID-19, many medical schools in the United Kingdom have discontinued placements [5]. Consequently, students have received decreased exposure to certain medical and surgical specialties, which may in turn reduce the students’ examination performance, confidence, and abilities as future physicians [5]. In these exceptional circumstances, the COVID-19 pandemic has posed an unparalleled challenge to medical schools, which are aiming to deliver quality education to students virtually [6].

The objectives of this study are to review the advantages and disadvantages of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic using the emerging current literature.

Methods

A systematic review of peer-reviewed literature on the subject of virtual medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted from May 2020 to June 2020, consistent with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [7]. Electronic databases, including PubMed and Google Scholar, were searched using the following key terms: medical student virtual teaching COVID-19, virtual undergraduate medical education COVID-19, and virtual medical education COVID-19. Qualitative results from the review were obtained by comparing and summarizing existing evidence and theories from recent literature.

The quantitative and qualitative studies were chosen based on specific inclusion criteria. The first and foremost criterion was that the study must be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. Second, the study was required to present original data assessing virtual medical teaching for medical students, with objectives related to analyzing the effectiveness or perception of this mode of learning. Finally, the included articles reported on studies conducted worldwide between February and June 2020, a period of time central to the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the shortage of available literature, this review considered any eligible study design, including case reports, case studies, cohort studies, randomized control trials, letters to the editor, commentaries, editorials, and perspectives. The first exclusion criterion was that the article was unrelated to undergraduate medical education. Excluded articles included those focusing on postgraduate medicine and on the teaching of other undergraduate health care professional students, such as dental, veterinary, or nursing students. Moreover, articles that assessed virtual teaching before the COVID-19 pandemic or articles relating to former pandemics were excluded.

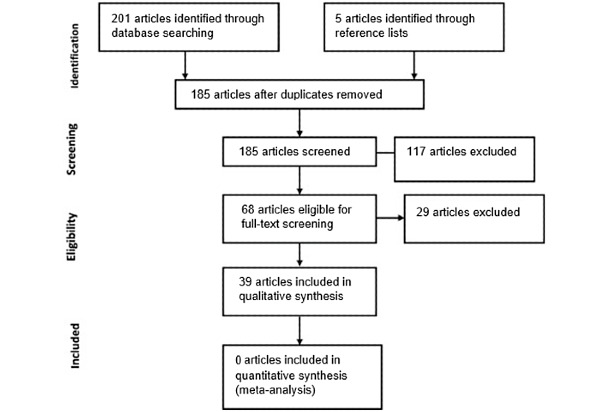

The search algorithm yielded 92 articles from the PubMed database and 109 articles from the Google Scholar database. After successful removal of duplicate articles, 185 articles were processed to analyze their titles and abstracts, and a total of 68 articles were found to be eligible for full-text screening. Following the full-text screening, a total of 34 articles were included for data extraction. An additional 5 articles were added after manually searching the reference lists of the included articles. Prominent findings from the review are presented in a table under the following headlines: summary of virtual teaching, strengths of virtual teaching, and weaknesses of virtual teaching.

Results

In the initial search, 201 articles were found in electronic databases. Following the removal of duplicates, 185 articles were scanned on the premise of title and abstract, and a total of 68 articles were determined to be eligible for full-text screening, of which 34 articles satisfied the inclusion criteria. Manual reviews of reference lists enabled the addition of 5 articles to the review. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, which demonstrates the process of study selection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram demonstrating the process of study selection.

The findings from the 39 papers reviewed are tabulated in Table 1. The table documents key findings from original articles relating to the type of virtual teaching offered and the strengths and weaknesses of virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative analysis of the included articles was conducted.

Table 1.

Comparison and evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Summary of virtual teaching offered | Advantages of virtual teaching | Disadvantages of virtual teaching | Reference |

| An observational study that reported the use of virtual ward rounds to educate medical students (n=14) regarding COVID-19 cases |

|

No weaknesses noted | [6] |

| A letter to the editor that reported the use of web-based education networks for medical students, such as lectures, case discussions, journal clubs, and virtual grand rounds |

|

No weaknesses noted | [8] |

| An observational study that reported the use of a medical student response team consisting of 500 students during the COVID-19 pandemic; there were 4 virtual teams that centered around education and activism for both health care professionals and the community |

|

No weaknesses noted | [9] |

| A reflective study that documented the concerns of medical students regarding their education during the COVID-19 pandemic; the study included 852 students, and 127 responses were analyzed | Virtual mentorship programs and virtual surgical skills workshops were suggested by 67% of medical students, closely followed by webinars (62%) and virtual research symposia (46%). |

|

[10] |

| A study evaluating the use of virtual medical education platforms |

|

|

[11] |

| A qualitative review documenting the challenges and innovations of virtual medical education platforms |

|

Loss of clinical opportunities: lack of bedside teaching, lack of direct patient care, halted improvement of examination skills, loss of feedback from tutors | [12] |

| An observational study that reviewed the use of academic coaching to supplement virtual medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

Without academic input, students may have ineffective learning strategies, poor motivation, and suboptimal communication skills, which are maximized by home learning. | [13] |

| A study highlighting the disruption of anatomy education, from dissecting laboratories to web-based virtual platforms, during the COVID-19 pandemic | No strengths noted |

|

[14] |

| A letter to the editor that reflected on the difficulties of virtual medical education | No strengths noted |

|

[15] |

| An analysis of the adaptations made to anatomical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Anatomy education within the United Kingdom has moved away from the use of cadavers to virtual lectures and virtual cadaveric resources. |

|

|

[16] |

| A study that reported the use of virtual callbacks for patients recently evaluated in the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

No weaknesses noted | [17] |

| A study conducted in Nepal evaluating the use of virtual medical education platforms |

|

|

[18] |

| A study that evaluated the use of virtual morning reports to deliver effective virtual teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

[19] |

| A study encouraging the sharing of virtual learning materials between institutions to aid virtual undergraduate medical education |

|

No weaknesses noted | [20] |

| A study evaluating the use of web-based virtual platforms for medical students and the future role these platforms may play in medical education after the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

[21] |

| A letter to the editor that explored how to sustain learning during the COVID-19 pandemic via the use of webinars, case-based discussions, journal clubs, and virtual classrooms |

|

|

[22] |

| A pilot study that reported the use of virtual clerkship for medical students (n=6) for 14 days. |

|

|

[23] |

| A study conducted in Iran documenting the shift to virtual medical education |

|

|

[24] |

| A study evaluating the use of virtual medical education for medical students |

|

|

[25] |

| A study demonstrating the value of peer learning during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

No weaknesses noted | [26] |

| A pilot study comparing face-to-face and virtual teaching of surgical skills for final year medical students (n=30) |

|

|

[27] |

| A study highlighting the possible methods of virtual education, including modules, reading assignments, and virtual scenarios |

|

No weaknesses noted | [28] |

| A letter to the editor documenting the structural changes of medical education within Brazil | No strengths noted |

|

[29] |

| A study conducted in Nepal demonstrating the difficulties faced by virtual medical education | Continuous education during the pandemic |

|

[30] |

| A letter to the editor documenting the impact of COVID-19 on the medical curriculum; the article references the effectiveness of Zoom and web-based lectures |

|

No weaknesses noted | [31] |

| A letter to the editor reflecting on the loss of clinical opportunities faced by current medical students | No strengths noted | Students must spend time on the ward with direct patient contact to prepare for the realities of working life. | [32] |

| A study evaluating the use of digital clinical placements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

Limited access to patients | [33] |

| A study evaluating the impact of virtual education on current medical students during the COVID-19 crisis. |

|

|

[34] |

| A study documenting the changes in medical education within the United Kingdom; the study references virtual teaching at Imperial College London, where patients are interviewed virtually by both physicians and medical students to facilitate teaching |

|

|

[35] |

| A study that reported the effects of virtual medical education on students in Italy | Virtual learning is effective to achieve primary aims and continue education in the short-term. |

Long-term virtual learning would have negative effects on students, administrative staff, and tutors. | [36] |

| A study that documented the replacement of clinical general practice attachments with e-learning programs in Australia |

|

|

[37] |

| A letter to the editor reflecting on student perspective and feedback regarding undergraduate ophthalmology virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

[38] |

| A study evaluating the student perspective of e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic; a survey was sent to 983 students in April 2020 questioning the effectiveness and satisfaction of web-based classes |

|

Students found that virtual teaching was less effective than classroom teaching for convenience, interaction, understanding individualized learning needs, and balancing practical and theoretical skills. | [39] |

| A study that demonstrated the effectiveness of virtual OSCEsa during the COVID-19 pandemic; a teleOSCEb was performed through Zoom with 49 medical students | There was no difference in mean score (mean difference –1.1; 95% CI –2.8 to 0.7; P=.2) or failure rate (rate difference 2%; 95% CI 0.7% to 10.7%; P=.06) between the groups. | No weaknesses noted | [40] |

| A commentary discussing the transition of medical education to the internet |

|

Lack of formal assessments |

[41] |

| A study that evaluated the use of virtual pastoral support during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

[42] |

| A study that documented the web-based transition of MCQsc for a medical education faculty |

|

No weaknesses noted | [43] |

| A review noting the impact of COVID-19 on medical education as well as mental well-being | Virtual learning is not new; many faculty members had prior training in the use of web-based platforms. |

|

[44] |

| A study that reported on the effectiveness of peer mentoring for medical students (n=371) during the COVID-19 pandemic via the use of WhatsApp |

|

Students desired face-to-face social interaction despite virtual interaction | [45] |

aOSCE: objective structured clinical examination.

bteleOSCE: teleconferencing objective structured clinical examination.

bMCQs: multiple choice questions.

Discussion

Summary of Results

This exploratory review questions the effectiveness of virtual teaching for medical students during the COVID-19 crisis by comparing the advantages and disadvantages listed in all available literature reports, as documented in Table 1.

Principal Strengths of Virtual Teaching

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided medical education institutions with a unique opportunity to adapt and advance their medical teaching methods. Previously, medical institutions relied upon classroom teaching, such as lectures, for preclinical year medical students, followed by various specialty medical attachments, completed in hospitals, for clinical year medical students [35]. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, university studies were suspended, and a rapid transition to virtual learning occurred [35].

The analysis of the available literature reveals several advantages of virtual teaching for medical students. First, the development of interactive virtual clinical teaching has been shown to be one of the most effective forms of virtual teaching, ranked by advancement of knowledge, student engagement, and student feedback. Hofmann et al [6] explored the use of virtual ward rounds to allow medical students to observe and interact with patients with COVID-19 while eliminating the risk of infection. Although their sample size of 14 students was limited, Hofmann et al demonstrated that students were enthusiastic to learn about a novel disease that is directly relevant to the world. Through student feedback, it was found that 92.9% of students recommended this form of teaching and agreed that it stimulated learning [6]. Similarly, a study by Murdock et al [19] evaluated the use of virtual morning reports to deliver effective and engaging teaching to medical students from multiple institutions worldwide. The strengths of this mode of teaching included the active development of student clinical reasoning skills as well as the ability to gain feedback from tutors and peers alike. Some institutions developed virtual clerkships, via the use of Zoom, to further increase medical students’ clinical exposure. Chandra et al [17] reported on the use of virtual callbacks conducted by medical students for patients who had recently evaluated in the emergency department. This program was found to help all parties; student feedback was overwhelmingly positive as a result of the direct patient interaction, and the students further stated that they felt that this mode of teaching increased their clinical reasoning and communication skills. Moreover, there was a reduced clinical load for the medical team, and the patients found it comforting to receive a follow-up appointment upon discharge. Likewise, a pilot study from Geha et al [23] reported on the use of 14-day virtual clerkships for medical students. The results of this paper indicated an advancement in medical knowledge and clinical reasoning skills through social learning and cognitive apprenticeship, increased student engagement due to interactivity, and the ability to learn from real-life patients. Although the study was limited due to a sample size of 6 students, the study showed that 5 of the 6 students felt positive about the placement and wanted to continue with this form of teaching above others [23]. Furthermore, Imperial College London hosted virtual patient interviews for medical students; the study reported excellent student attendance and interaction, with benefits of increasing student clinical reasoning skills and diagnostic thought processes as well as reducing the burden on the health care system by providing an efficient triage system [35]. Finally, Harvard Medical School developed the use of virtual medical student response teams that consisted of 500 students arranged into 4 virtual teams with the aim to either educate or help the community or health care teams [9]. Due to the active role of helping during a worldwide pandemic, students reported feeling empowered and enthusiastic, and they felt a sense of purpose during uncertain times. Moreover, the project facilitated team working skills and indirectly increased student knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 [9]. Despite the highlighted successes of these highly interactive forms of virtual teaching, limited literature is available on these programs, suggesting that they are underdeveloped and not in use by most medical education facilities. Potential factors that may contribute to the underdevelopment of these specific programs are the scalability of the programs as well as the time commitments needed from clinicians when work demand is already at a critical stage [23].

The main format of virtual teaching for medical students is through virtual web-based platforms. Virtual web-based platforms consist of webinars, case discussions, reading assignments, and prerecorded virtual scenarios [28]. An advantage, noted through multiple publications available on this theme, was the ease of accessibility and unlimited flexibility of medical resources [8,11,12,19,22,24,25]. In a time of great uncertainty and doubt, providing students with increased flexibility and access to teaching materials may further encourage self-directed learning and motivation. Furthermore, open access teaching from world-renowned medical specialists, irrespective of location and cost, has now become available during the COVID-19 crisis [8]. Teaching provided by experts and promoted through social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram Live can act as valuable adjuncts to virtual teaching. This teaching can also accelerate student knowledge and interest in specialties a student has not yet experienced and can enable students to observe the latest medical advancements [8,12,28,34]. Networking between students and physicians, which many students thought would be lost due to the suspension of attachments, has been revived through the use of virtual conferences and social media [8,12].

Peer mentoring during the COVID-19 crisis has proved to be a valuable form of teaching. Peer mentoring involves student-to-student teaching; it helps develop active discussion, exchange of ideas, critical thinking, and collaboration between colleagues [26]. In uncertain times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, peer mentoring can help drive student motivation and task management, increasing the effectiveness of self-directed study [26]. Personal development may also be improved by peer mentoring; qualities such as resilience, conflict resolution, and leadership may all be developed through this mode of teaching [26]. A study by Mohammed Sami Hamad et al [26] demonstrated that peer learning may also lead to increased examination performance due to improvements in problem-solving skills. Peer mentoring can also be used to provide psychological support to colleagues. A study by Rastegar Kazerooni et al [45] discussed the use of a WhatsApp group consisting of 371 medical students to provide advice and reassurance during the pandemic. Using student feedback from the study, it was found that 71% of junior medical students reported a smoother transition with quicker adjustment to the COVID-19 crisis, and senior students benefited from significant professional growth [45].

Student perception of virtual teaching is imperative to understand to deliver effective teaching throughout the pandemic. A study conducted by Sud et al [38] reported that 97.2% of students felt that web-based classes were a good alternative to classroom teaching during the pandemic. This was further reiterated by a study by Kaur et al [39] that surveyed 983 medical students on their satisfaction with virtual teaching during the COVID-19 crisis. The outcomes of the study showed that students felt that virtual teaching was as effective as classroom teaching for improving communication, increasing knowledge and skills, professional growth, and submission of assignments. Moreover, students were happy with the availability of electronic resources offered by virtual learning platforms [39]. Upon review of the current literature, it is evident that medical students have a strong passion and determination to learn during the pandemic. Articles written by Sandhu et al [21] and Marques du Silva [31] demonstrated increased class attendance at webinars and positive student feedback of web-based extracurricular lectures. Guadix et al [10] conducted a survey to understand what medical students with an interest in neurosurgery desired from virtual teaching. Of the 127 students who responded, 67% wanted virtual mentorship programs and virtual surgical skills workshops in addition to their medical school studies [10].

Principal Weaknesses of Virtual Teaching

A significant number of published studies indicated that a major disadvantage of virtual teaching is technical difficulties [11,15,18,21,22,25,27,29,30,37,38,42,44]. On further analysis of the technical difficulties experienced by students, several different challenges to virtual teaching arose. The largest problem presented by virtual teaching was that some students had no access to digital technology; thus, virtual learning was an ineffective or impossible form of teaching for those students [22,29,30,38,42,44]. Other technical challenges included difficulties establishing a reliable internet connection [11,18,27,30,38,42], problems with hardware and software for virtual learning platforms [21,42], problems relating to internet speed and quality [22,37], and problems with audio and video playback [25]. Moreover, a study by Machado et al [15] reported that virtual learning platforms may become overloaded due to the sheer number of students accessing the materials; overload of a platform stops the platform from working and hinders student learning [15].

Papers by Murdock et al [19] and Sleiwah et al [25] raised concerns with respect to confidentiality and security issues [19,25]. “Zoom-bombing” is a practice in which hackers invade Zoom sessions; therefore, virtual sessions that document real patient information may be at risk of security breaches [19].

The loss of face-to-face teaching was another significant weakness of virtual teaching. The loss of clinical attachments was referenced by numerous publications [10,12,22,34]. Dedeilia et al [12] suggested that the loss of clinical attachments, subsequently causing a loss of bedside teaching, a lack of direct patient care, and a loss of feedback from clinicians, halted the progression of the competencies of a medical student. This was further reiterated by Kaup et al [22], who reported a decline in the clinical and surgical competencies of medical students during the pandemic [22]. Interestingly, Sahi et al reported a possible cessation of professional growth of medical students due to a lack of influential clinical role models during this time [11]. Furthermore, Hilburg et al [34] described a life-changing effect in which the loss of clinical attachments during medical school may impact the specialty the student chooses to pursue in later life [34].

The transition to virtual teaching via the use of web-based medical education platforms presents its own individual disadvantages. Studies by Machado et al [15] and Atreya et al [18] reported the hardships of maintaining focus and concentration whilst sitting in front of a screen. Similarly, Lee et al [13] found that without academic input, students were more likely to have ineffective learning strategies, poor motivation, and reduced communication. Physical discomfort, such as exhaustion, visual problems, and muscle and joint pain, was also reported with long periods of virtual teaching [30]. Unsurprisingly, papers by Longhurst et al [16] and Kaup et al [22] found reduced student engagement levels associated with virtual teaching. Longhurst et al [16] suggested that student engagement decreased as a result of reduced monitoring of students, whereas Kaup et al [22] argued that reduced student engagement was due to a lack of student focus, interest in other environmental activities around students, and technical difficulties [22]. Surkhali et al [30] highlighted that a further disadvantage of virtual teaching is that tutors have difficulties assessing student disengagement, frustration, and disinterest; this may reduce the quality and effectiveness of virtual teaching. Loss of student-tutor interactivity was another potential causative factor for reduced student engagement, as evidenced by Michael et al [27] and Sud et al [38].

Concerns regarding preclinical year medical student education were also identified in this review. Studies by Hilburg et al [34] and Mian et al [35] highlighted that this student cohort would have significantly weak clinical foundations, which provide the building blocks for students’ clinical years and subsequent life as physicians. Hilburg et al [34] argued that the lack of face-to-face teaching for skills, such as history taking and physical examinations, would negatively impact students’ transition to their clinical years. Furthermore, suspension of studies has drastically disrupted the teaching of anatomy. A paper by Singal et al [14] documented the difficulties faced by students in understanding anatomy without the tools of dissection, practical teaching, specimens, or slides. A future concern of anatomists and medical education facilities alike is a lack of cadavers following the COVID-19 pandemic due to the potential risk of infection of the deceased [14].

The loss of formal assessments is an additional weakness of virtual teaching. A study by Longhurst et al [16] reported that 50% of medical student examinations had been cancelled, and even more had been adjusted to unfamiliar formats. Kaup et al [22] argued that this was due to a lack of security and validity of conducting virtual examinations. Interestingly, a study published by Lara et al [40] documented the novel use of a teleconference objective structured clinical examination (teleOSCE) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study indicated that for the 49 medical students who participated, there was no difference in mean score or failure rate between face-to-face and virtual OSCEs, suggesting that this form of assessment was an effective and reliable method of testing and could be explored in the future [40].

Weaknesses of virtual teaching identified by medical students included reduced interaction between peers and tutors, reduced understanding of individualized learning needs by tutors, and the difficulties of balancing practical and theoretical skills [39]. Virtual teaching platforms from the perspective of medical education faculties were found to be costly and time-consuming [11,15,16,21].

The Use of Virtual Medical Education Worldwide

The literature included in this review includes papers written worldwide. Upon analysis, it is evident that virtual teaching for medical students differs by country and that students may have exceedingly different learning experiences [9,18,24,29,30,35,37]. These different learning experiences delivered by virtual teaching may create inequalities of knowledge, confidence, and skills of medical students on a global basis [15].

In developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, Italy, the United States, and Australia, virtual teaching for medical students is a praised method of teaching [9,35-37]. Studies by Soled et al [9] from the United States and Roskvist et al [37] from Australia highlight the advancement of virtual medical teaching formats away from the standard virtual web-based platforms. Soled et al discussed the use of interactive virtual medical committees consisting of 500 medical students with the aim to educate or partake in community activism to help with and understand the global pandemic, whereas Roskvist et al documented the replacement of normal clinical attachments with interactive e-learning placements in Australia. The results of the study by Roskvist et al [37] showed web-based learning to be as effective as traditional teaching. Virtual teaching within the United Kingdom mirrored virtual learning in Australia and America; more interactive and advanced technological forms of virtual learning were found to increase student engagement and focus [35]. Italy reported that virtual learning is an effective way to teach medical students during a time of crisis [36].

In stark contrast, developing countries such as Nepal, Iran, and Brazil negatively reported on the effectiveness of virtual teaching due to poorly funded and inadequate infrastructures for virtual learning [18,24,29,30]. Studies conducted in Nepal demonstrated apparent barriers to virtual teaching, including lack of knowledge on how to operate virtual platforms by staff and students alike, difficulties finding a quiet environment to study, technical challenges, reduced student engagement due to the use of self-directed learning with limited interactivity, and mental distress from social isolation [18,30]. In Iran, due to a lack of preparation of virtual learning resources, not all age groups within the medical curriculum had access to virtual teaching materials; also, medical education facilities experienced difficulties virtualizing different aspects of the medical course [28]. Finally, Carvalho et al [29] published a letter from Brazil documenting the challenges faced by the medical education system in Brazil. Similarly, the reported challenges to virtual teaching primarily arose due to a lack of investment. Moreover, Carvalho et al [29] documented the important points that not all students within Brazil have access to digital technology and some may be socially vulnerable, which further inhibits learning away from the university.

Mental Well-Being of Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Virtual teaching for medical students is novel, and the distinct lack of social interaction may increase feelings of isolation, anxiety, and boredom [16]. The lack of physical, mental and social support from peers and institutions during this time may prevent learning [22] as a result of decreased motivation, lack of social engagement, decreased personal assessment of quality of life, and increased stress levels [16.] Feelings of isolation may further contribute to social withdrawal and cause a lack of student participation with virtual teaching resources [30]; in turn, the factors mentioned above may decrease academic performance [16,30]. A study conducted in Italy recognized that while short-term virtual learning is effective, long-term virtual learning would have significant negative effects on students, tutors, and administrative staff [36].

A study by Hodgson et al [42] discussed the use of virtual pastoral support to help students through this unsettling time. Virtual pastoral support was conducted through smartphones or computers at times that were convenient to the students; student engagement with this service was in high demand and student feedback was positive, noting that this support offered relief from stress and respite from studies. Moreover, the study highlighted that staff offering pastoral support may be less likely to interact with students virtually due to universities previously discouraging social media interaction and mobile phone contact with students [42].

Limitations of the Review

Limitations to be considered in this review include its preliminary and exploratory direction; the literature available for review was restricted due to the emerging nature of COVID-19. In turn, this limitation governed a wider set of inclusion criteria and allowed the acceptance of all types of manuscripts within the review, which may reduce the acceptability of the results to a broader population. Moreover, PubMed was the only legitimate scientific database used, with Google Scholar providing supplemental searches. This limitation raises concerns that some papers relevant to the topic may have been missed. In addition, in the literature analyzed, many studies had small sample sizes; this may decrease the reliability of the findings. A further limitation of this review was the lack of studies that incorporated student perception of traditional teaching in comparison to virtual teaching.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Virtual teaching for medical students has enabled medical education to continue despite the effects of the pandemic. The COVID-19 outbreak has provided medical education faculties with the perfect opportunity to develop and further the application and effectiveness of virtual learning for medical students. Medical education faculties should embrace the transition to virtual teaching and continue to develop web-based materials, such as secure web-based assessments and resources with increased student interactivity, to ensure that the most effective and suitable teaching is delivered. Virtual teaching requires significant investment from institutions, and many education faculties worldwide are struggling; institutions should actively seek to share web-based learning materials to improve content and accelerate student learning. Technical challenges and security concerns are inevitable barriers to virtual learning; students and staff members alike should strive to minimize these barriers.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- teleOSCE

teleconferencing objective structured clinical examination

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. Corrigendum to "World Health Organization declares Global Emergency: A review of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)" [Int. J. Surg. 76 (2020) 71-76] Int J Surg. 2020 May;77:217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.03.036. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32305321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. [2020-05-29]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- 3.Lake M. What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research. Clin Med (Lond) 2020 Mar;20(2):124–127. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2019-coron. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32139372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronavirus (COVID‑19) UK Government. [2020-05-29]. https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus.

- 5.Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;20(7):777–778. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30226-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmann H, Harding C, Youm J, Wiechmann W. Virtual bedside teaching rounds with patients with COVID-19. Med Educ. 2020 May 13;54(10):959–960. doi: 10.1111/medu.14223. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32403185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 18;151(4):264–9, W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abi-Rafeh J, Azzi AJ. Emerging role of online virtual teaching resources for medical student education in plastic surgery: COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020 Aug;73(8):1575–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.05.085. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32553546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soled D, Goel S, Barry D, Erfani P, Joseph N, Kochis M, Uppal N, Velasquez D, Vora K, Scott KW. Medical Student Mobilization During a Crisis: Lessons From a COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team. Acad Med. 2020 Sep;95(9):1384–1387. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003401. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32282373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guadix SW, Winston GM, Chae JK, Haghdel A, Chen J, Younus I, Radwanski R, Greenfield JP, Pannullo SC. Medical Student Concerns Relating to Neurosurgery Education During COVID-19. World Neurosurg. 2020 Jul;139:e836–e847. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.090. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32426066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahi PK, Mishra D, Singh T. Medical Education Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Indian Pediatr. 2020 May 14;57(7):652–657. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1894-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, Janga D, Dedeilias P, Sideris M. Medical and Surgical Education Challenges and Innovations in the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review. In Vivo. 2020 Jun 05;34(3 Suppl):1603–1611. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee I, Koh H, Lai S, Hwang N. Academic coaching of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Educ. 2020 Jun 12; doi: 10.1111/medu.14272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singal A, Bansal A, Chaudhary P. Cadaverless anatomy: Darkness in the times of pandemic Covid-19. Morphologie. 2020 Sep;104(346):147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2020.05.003. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32518047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado R, Bonan P, Perez DED, Martelli D, Martelli-Júnior H. I am having trouble keeping up with virtual teaching activities: Reflections in the COVID-19 era. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2020;75:e1945. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2020/e1945. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1807-59322020000100502&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longhurst GJ, Stone DM, Dulohery K, Scully D, Campbell T, Smith CF. Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat (SWOT) Analysis of the Adaptations to Anatomical Education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020 May 09;13(3):301–311. doi: 10.1002/ase.1967. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32306550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra S, Laoteppitaks C, Mingioni N, Papanagnou D. Zooming‐out COVID‐19: Virtual clinical experiences in an emergency medicine clerkship. Med Educ. 2020 Jul 07; doi: 10.1111/medu.14266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atreya A, Acharya J. Distant virtual medical education during COVID-19: Half a loaf of bread. Clin Teach. 2020 Jun 18;17(4):418–419. doi: 10.1111/tct.13185. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32558269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murdock HM, Penner JC, Le S, Nematollahi S. Virtual Morning Report during COVID‐19: A novel model for case‐based teaching conferences. Med Educ. 2020 Jun 22;54(9):851–852. doi: 10.1111/medu.14226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuo L, Dillman D, Miller Juvé A. Learning at home during COVID-19: A multi-institutional virtual learning collaboration. Med Educ. 2020 Jul;54(7):664–665. doi: 10.1111/medu.14194. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32330317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marques da Silva B. Will Virtual Teaching Continue After the COVID-19 Pandemic? Acta Med Port. 2020 Jun 01;33(6):446. doi: 10.20344/amp.13970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaup S, Jain R, Shivalli S, Pandey S, Kaup S. Sustaining academics during COVID-19 pandemic: The role of online teaching-learning. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(6):1220. doi: 10.4103/ijo.ijo_1241_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: Podcasts, peers and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020 Sep 17;54(9):855–856. doi: 10.1111/medu.14246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmady S, Shahbazi S, Heidari M. Transition to Virtual Learning During the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Crisis in Iran: Opportunity Or Challenge? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020 May 07;:1–2. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.142. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32375914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sleiwah A, Mughal M, Hachach-Haram N, Roblin P. COVID-19 lockdown learning: The uprising of virtual teaching. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020 Aug;73(8):1575–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.05.032. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32565141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammed Sami Hamad S, Iqbal S, Mohammed Alothri A, Abdullah Ali Alghamadi M, Khalid Kamal Ali Elhelow M. “To teach is to learn twice” Added value of peer learning among medical students during COVID-19 Pandemic. MedEdPublish. 2020;9(1) doi: 10.15694/mep.2020.000127.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Co M, Chu K. Distant surgical teaching during COVID-19 - A pilot study on final year medical students. Surg Pract. 2020 Jul 10; doi: 10.1111/1744-1633.12436. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32837531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg T, Shrigiriwar A, Patel K. Trainee education during COVID-19. Neuroradiology. 2020 Sep 17;62(9):1057–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00234-020-02478-w. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32556422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carvalho VO, Conceição LSR, Gois MB. COVID-19 pandemic: Beyond medical education in Brazil. J Card Surg. 2020 Jun 12;35(6):1170–1171. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14646. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32531127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surkhali B, Garbuja C. Virtual Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: Pros and Cons. J Lumbini Med Coll. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.22502/jlmc.v8i1.363. https://www.jlmc.edu.np/index.php/JLMC/article/view/363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandhu P, de Wolf M. The impact of COVID-19 on the undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2020 Dec 13;25(1):1764740. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1764740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammond D, Louca C, Leeves L, Rampes S. Undergraduate medical education and Covid-19: engaged but abstract. Med Educ Online. 2020 Jan 01;25(1):1781379. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1781379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sam A, Millar K, Lupton M. Digital Clinical Placement for Medical Students in Response to COVID-19. Acad Med. 2020 Aug;95(8):1126. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003431. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32744817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS. Medical Education During the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic: Learning From a Distance. Forthcoming. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mian A, Khan S. Medical education during pandemics: a UK perspective. BMC Med. 2020 Apr 09;18(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01577-y. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-020-01577-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bianchi S, Gatto R, Fabiani L. Effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on medical education in Italy: considerations and tips. EuroMediterranean Biomed J. 2020;15(24):100–101. doi: 10.3269/1970-5492.2020.15.24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roskvist R, Eggleton K, Goodyear-Smith F. Provision of e-learning programmes to replace undergraduate medical students' clinical general practice attachments during COVID-19 stand-down. Educ Prim Care. 2020 Jul 29;31(4):247–254. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2020.1772123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sud R, Sharma P, Budhwar V, Khanduja S. Undergraduate ophthalmology teaching in COVID-19 times: Students' perspective and feedback. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(7):1490. doi: 10.4103/ijo.ijo_1689_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaur N, Dwivedi D, Arora J, Gandhi A. Study of the effectiveness of e-learning to conventional teaching in medical undergraduates amid COVID-19 pandemic. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2020;10(7):1. doi: 10.5455/njppp.2020.10.04096202028042020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lara S, Foster CW, Hawks M, Montgomery M. Remote Assessment of Clinical Skills During COVID-19: A Virtual, High-Stakes, Summative Pediatric Objective Structured Clinical Examination. Acad Pediatr. 2020 Aug;20(6):760–761. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.05.029. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32505690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Jun 02;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodgson JC, Hagan P. Medical education adaptations during a pandemic: Transitioning to virtual student support. Med Educ. 2020 Jul 26;54(7):662–663. doi: 10.1111/medu.14177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eltayar AN, Eldesoky NI, Khalifa H, Rashed S. Online faculty development using cognitive apprenticeship in response to COVID-19. Med Educ. 2020 Jul 27;54(7):665–666. doi: 10.1111/medu.14190. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32324934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahu P. Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus. 2020 Apr 04;12(4):e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32377489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rastegar Kazerooni A, Amini M, Tabari P, Moosavi M. Peer mentoring for medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic via a social media platform. Med Educ. 2020 Aug;54(8):762–763. doi: 10.1111/medu.14206. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32353893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]