Abstract

Objective

To assess over 3 years of follow-up the effects of maintaining or switching to ocrelizumab (OCR) therapy on clinical and MRI outcomes and safety measures in the open-label extension (OLE) phase of the pooled OPERA: I/II studies in relapsing multiple sclerosis.

Methods

After 2 years of double-blind, controlled treatment, patients continued OCR (600 mg infusions every 24 weeks) or switched from interferon (IFN)-β-1a (44 μg 3 times weekly) to OCR when entering the OLE phase (3 years). Adjusted annualized relapse rate, time to onset of 24-week confirmed disability progression (CDP)/improvement (CDP), brain MRI activity (gadolinium-enhanced and new/enlarging T2 lesions), and percentage brain volume change were analyzed.

Results

Of patients entering the OLE phase, 88.6% completed year 5. The cumulative proportion with 24-week CDP was lower in patients who initiated OCR earlier vs patients initially receiving IFN-β-1a (16.1% vs 21.3% at year 5; p = 0.014). Patients continuing OCR maintained and those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR attained near complete and sustained suppression of new brain MRI lesion activity from years 3–5. Over the OLE phase, patients continuing OCR exhibited less whole brain volume loss from double-blind study baseline vs those switching from IFN-β-1a (−1.87% vs −2.15% at year 5; p < 0.01). Adverse events were consistent with past reports and no new safety signals emerged with prolonged treatment.

Conclusion

Compared with patients switching from IFN-β-1a, earlier and continuous OCR treatment up to 5 years provided sustained benefit on clinical and MRI measures of disease progression.

Classification of evidence

This study provides Class III evidence that earlier and continuous treatment with OCR provided sustained benefit on clinical and MRI outcomes of disease activity and progression compared with patients switching from IFN-β-1a. The study is rated Class III because of the initial treatment randomization disclosure that occurred after inclusion in OLE.

Clinical trial identifiers

NCT01247324/NCT01412333.

Ocrelizumab (OCR) is a humanized monoclonal antibody that selectively targets CD20+ B cells while preserving the capacity for B-cell reconstitution and preexisting humoral immunity.1,2 In phase III randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trials with identical designs (OPERA [A Study of Ocrelizumab in Comparison With Interferon Beta-1a (Rebif) in Participants With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis] I [NCT01247324] and OPERA II [NCT01412333]) in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS), OCR demonstrated superior efficacy for preventing relapses and disability worsening, and a higher rate of disability improvement, compared with subcutaneous interferon (IFN)-β-1a given 3 times weekly.3 Significant benefits of OCR on MRI outcomes, including the reduction of the number of gadolinium (Gd)-enhancing T1 lesions, new or newly enlarged hyperintense T2 lesions, new hypointense T1 lesions, and brain volume loss (baseline to week 96) were also reported.3 We report the interim efficacy and safety results of OCR over the 3-year follow-up in the open-label extension (OLE) phase of phase III trials in patients with RMS (5 years of total follow-up).

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The relevant institutional review boards/ethics committees approved the trial protocols (NCT01247324 and NCT01412333). All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial design and patients

As previously detailed,3 OPERA I (NCT01247324) and OPERA II (NCT01412333) were phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, IFN-β-1a controlled trials with identical designs, of OCR in patients with RMS (data available from Dryad, figure e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw). Key eligibility criteria included an age of 18–55 years, diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS; 2010 revised McDonald criteria),4 and screening Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 0–5.5. Consistency of baseline characteristics and treatment effects across both OPERA studies met predetermined criteria for pooled efficacy analysis, including annualized relapse rate (ARR) and confirmed disability progression (CDP).3 Following completion of the double-blind controlled treatment phase (DBP) of both trials, patients meeting specific criteria (data available from Dryad, supplemental data, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw) were eligible to enter an OLE phase to evaluate the long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of OCR in RMS; patients who declined or who were not eligible (since there was an OLE screening phase) to participate in the OLE phase entered safety follow-up. Patients entering the OLE phase first entered the OLE screening phase, which lasted up to 4 weeks. At the start of the OLE phase, patients who received OCR in the DBP continued OCR and patients from the IFN-β-1a group were switched to OCR, given every 24 weeks; in order to maintain blinding and in accordance with the start of the DBP, all patients received the first dose of OCR as 2 separate 300 mg infusions, 2 weeks apart. Patient treatment allocation was unblinded after the last data point from the last patient from the DBP was received. The 96-week core studies were conducted between 2011 and 2015. The first patient completing the DBP entered the OLE phase in August 2013; the last ongoing patient entered the OLE phase in February 2015. The clinical cutoff date for inclusion of data in this analysis was February 5, 2018. The OLE phase is planned until December 2020, with the collection of data for up to 8 years.

Classification of evidence

This study provides Class III evidence that earlier and continuous treatment with OCR provided sustained benefit on clinical and MRI outcomes of disease activity and progression compared with patients switching from IFN-β-1a. The study is rated Class III because of the initial treatment randomization disclosure that occurred after inclusion in the OLE.

Efficacy assessments

The following endpoints, which were also measured during the 96-week DBP, are reported for the OLE phase, using the pooled OPERA trial population.

Annualized relapse rate

The ARR was calculated as the total number of protocol-defined relapses (occurrence of new or worsening neurologic symptoms [consistent with an increase of at least half a step on the EDSS score, or 2 points on one of the appropriate Functional Systems Scores (FSS), or 1 point on 2 or more of the appropriate FSS] that were attributable to MS) for all patients in the treatment group divided by the total patient-years of exposure to that treatment.

Twenty-four week confirmed disability progression/improvement

CDP was defined as an increase in the EDSS score from the baseline of the DBP or of the OLE phase of at least 1.0 point (increase of ≥0.5 points if baseline EDSS score >5.5); confirmed disability improvement (CDI) was defined as a reduction in EDSS score ≥1.0 point compared with baseline of the DBP or of the OLE phase (reduction of ≥0.5 point if baseline EDSS score >5.5). For analyses based on the OLE phase only, a rebaseline of EDSS was performed for all patients, including those who had an event of CDP/CDI during the DBP. All analyses from the DBP baseline were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, except for CDI, which was performed in the prespecified subgroup of the ITT population with EDSS ≥2.0. All analyses from OLE baseline were based on the OLE population with treatment group assignment based on the originally randomized treatment, except for CDI, which was performed in the prespecified subgroup of the OLE population with EDSS ≥2.0. For both CDP and CDI, rebaselining at the start of OLE provides a representation of efficacy during the OLE period unconfounded by any disease activity during the DBP, hence values for the proportion of patients with events during DBP and rebaselined OLE may not correspond with those of the combined DBP and OLE period.

Mean change from baseline in EDSS score

Mean change from baseline in EDSS score was assessed at scheduled visits during the DBP and the OLE phase.

Acute brain MRI lesion activity

The total number of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions and total number of T1 Gd-enhancing lesions on brain MRI was assessed every 48 weeks in the OLE phase.

Brain volume change

Percentage change in whole brain volume (WBV) was assessed using SIENA/X.5 Percent change in cortical gray matter volume (GMV) and white matter volume (WMV) was assessed using paired Jacobian integration.6 All analyses from the DBP baseline were based on the ITT population. All analyses from the OLE baseline were based on the OLE population with treatment group assignment based on the originally randomized treatment.

No evidence of disease activity (NEDA)

NEDA status was defined as the combined absence of protocol-defined relapses, 24-week CDP, new or enlarging T2 lesions, and T1 Gd-enhancing lesions.

Safety

All patients who received any study treatment were included in the safety population. All data collected during the DBP and OLE and the safety follow-up were included in the safety analyses. Safety outcomes are reported for the OLE phase using the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II ITT population.

Statistical analyses

ARR was analyzed with the use of a generalized estimating equation Poisson regression model in the ITT population. CDP/CDI at 24 weeks were assessed using Kaplan-Meier and Cox survival analysis in the ITT population and for CDI, in patients with a baseline EDSS score of ≥2.0; hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated by stratified Cox regression. Mean change from baseline in EDSS score was analyzed using the mixed-effect model of repeated measures (MMRM). The number of new T1 Gd-enhancing lesions and the number of new or enlarging T2 lesions were analyzed using a negative binomial model; in previously reported analysis3 of lesion outcomes during the DBP, results were adjusted for baseline T2 lesion volume, baseline EDSS score (≤2.5 vs >2.5), and geographic region (United States vs rest of the world). However, as patients had no new T1 Gd-enhancing lesions/new or enlarging T2 lesions at several time points, it was impossible to fit a statistical model, and unadjusted rates were adopted for the OLE instead. The change in WBV, GMV, and WMV was analyzed using the MMRM, adjusted for baseline WBV or GMV or WMV and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 vs ≥4.0), study, and geographic region (United States vs rest of the world). NEDA was analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by study, geographic region (United States vs rest of the world), and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 vs ≥4.0) in a modified ITT population, which included all patients in the ITT population, but patients who discontinued treatment early for reasons other than lack of efficacy or death and had NEDA before early discontinuation were excluded. Safety outcomes are reported as incidence rates (events per 100 patient-years of exposure) with Poisson distribution-based confidence intervals (CIs).

Data availability

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level data through the clinical study data request platform (vivli.org). Further details on Roche's criteria for eligible studies are available at vivli.org/members/ourmembers. For further details on Roche's Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm.

Results

Patient disposition, demographics, and disease characteristics

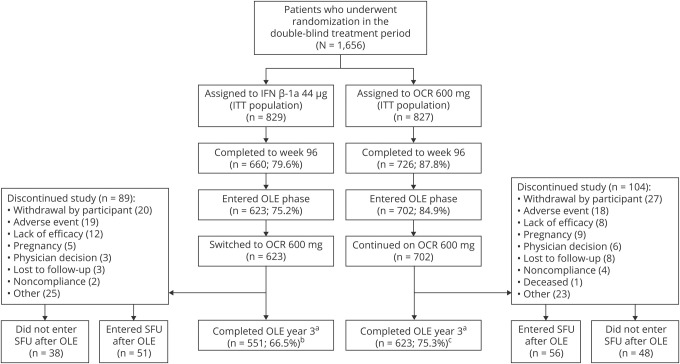

Patient disposition and reasons for discontinuation are shown in figure 1 by treatment group. More than 94% of patients in both groups who completed the DBP entered the OLE phase. Of 827 patients treated with OCR during the DBP, 702 (84.9%) entered the OLE phase and 623 (75.3%) remained at year 5. Of the 829 patients treated with IFN-β-1a in the DBP, 623 (75.2%) entered the OLE phase and 551 (66.5%) remained at year 5. Overall, 1,174 of 1,325 patients (89%) who entered the OLE phase of the OPERA studies completed year 5, representing 71% of the originally enrolled population (n = 1,656). Patient demographics and disease characteristics for the pooled studies at baseline of the DBP and at the start of the OLE phase were well balanced between treatment arms and between the ITT population and those patients with a baseline EDSS score of ≥2.0 (table 1). The number of OCR doses received (mean ± SD; median [range]) in the OLE phase population was 7.3 ± 2.0, 8.0 (1–10) for continuous OCR patients and 7.4 ± 1.9; 8.0 (1–10) in patients switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR.

Figure 1. Patient disposition in the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II intent-to-treat (ITT) population.

Percentages in parentheses are of the ITT population. aClinical cutoff date: February 5, 2018; patients entering the open-label extension (OLE) phase who completed the double-blind period (DBP): interferon (IFN)-β-1a 623/660 (94.4%) and ocrelizumab (OCR) 702/726 (96.7%). b88.4%, and c88.7%, of patients who entered the OLE completed year 3. SFU = safety follow-up.

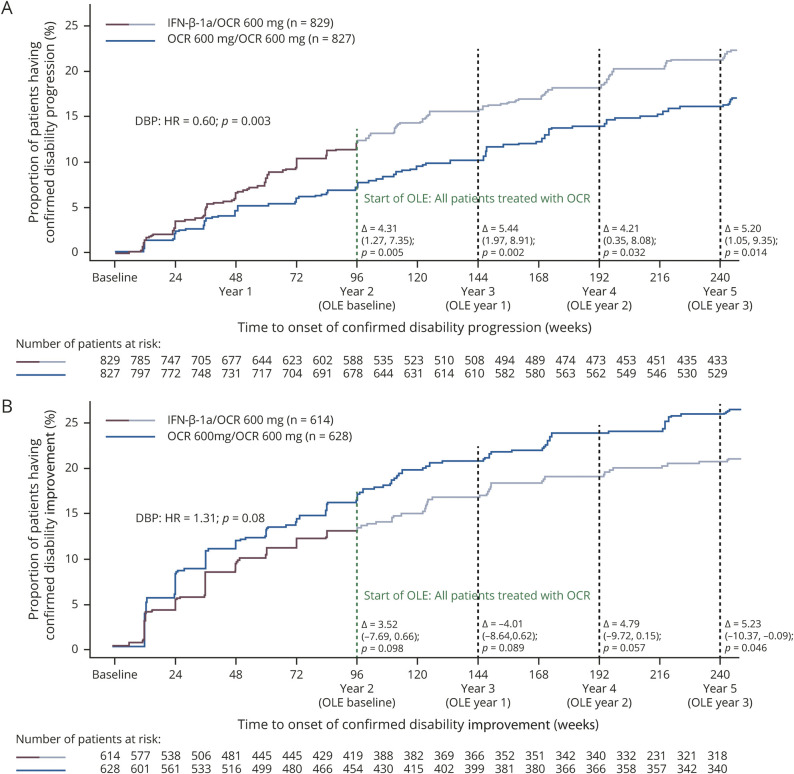

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II populations at the start of the double-blind period (DBP) and open-label extension (OLE)

Clinical efficacy assessments

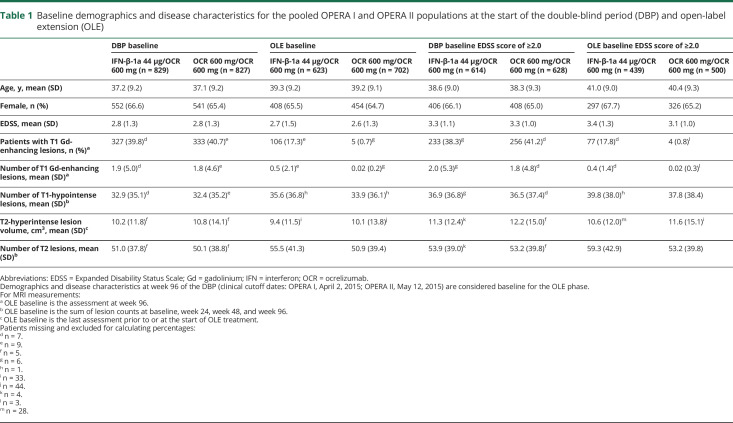

Patients receiving continuous OCR maintained a low ARR through year 1 to year 5 (0.14, 0.13, 0.10, 0.08, and 0.07; figure 2). Switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR at the start of the OLE phase was associated with a significant reduction in ARR (0.20 in year 2 to 0.10 in year 3; adjusted rate ratio [95% CI] 2.069 [1.547–2.766], p < 0.001; 52% relative reduction), which was maintained through years 4 and 5 (0.08 and 0.07; figure 2). In the OLE phase, there was no difference in ARR at years 3, 4, and 5 in patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a (p > 0.5, all comparisons; figure 2).

Figure 2. Annualized relapse rate (ARR) in double-blind controlled treatment phase (DBP) study years 1 and 2 and open-label extension (OLE) years 1–3.

Estimates are from analysis based on generalized estimating equation Poisson regression model with repeated measurements using unstructured covariance matrix, adjusted by randomized treatment, study, baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale (<4.0 vs ≥4.0), geographic region (United States vs rest of the world), year, and treatment-by-year interaction. Log-transformed exposure time is included as an offset variable. aThe total number of relapses for all patients in the treatment group divided by the total patient-years of exposure to that treatment. bDBP year 1 and DBP year 2 data include the intention-to-treat population (number of patients available); year 3 (OLE year 1), year 4 (OLE year 2), and year 5 (OLE year 3) data include the OLE ITT population (number of patients available). Clinical cutoff date: February 5, 2018. IFN = interferon; OCR = ocrelizumab.

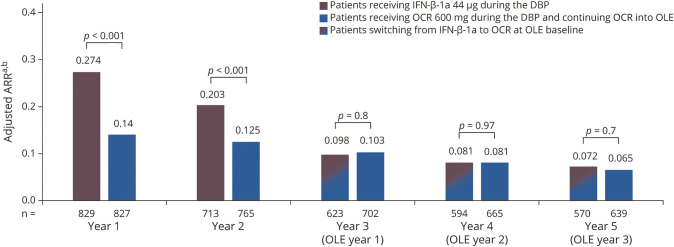

Over the duration of the DBP and OLE periods, time point analysis demonstrated that the proportion of patients with 24-week CDP from baseline remained significantly lower in patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR at the end of the DBP (year 2: 7.7% vs 12.0%; p = 0.005), at the end of year 3 (10.1% vs 15.6%; p = 0.002), at the end of year 4 (13.9% vs 18.1%; p = 0.03), and at the end of year 5 (16.1% vs 21.3%; p = 0.014; figure 3A). The HR for patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR for time to first 24-week CDP during the DBP was 0.60 (95% CI 0.43–0.84; p = 0.003); after rebaselining at the end of the DBP (i.e., start of the OLE), the HR during the OLE phase was 1.06 (95% CI 0.8–1.41; p = 0.7) (data available from Dryad, figure e-2A, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw).

Figure 3. Time to onset of confirmed disability progression (CDP) and confirmed disability improvement (CDI) for at least 24 weeks during double-blind controlled treatment phase (DBP) and open-label extension (OLE) periods.

Time to onset of (A) CDP and (B) CDI. Curves show Kaplan-Meier estimates of the proportion of patients with disability progression/improvement events relative to the original double-blind treatment period baseline throughout double-blind and OLE periods. Without imputation. Intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Pooled OPERA I and OPERA II population; DBP clinical cutoff dates: April 2, 2015, and May 12, 2015, respectively; OLE clinical cutoff date: February 5, 2018. Data shown up to week 240, the last visit all ongoing patients completed. HR = hazard ratio; IFN = interferon; OCR = ocrelizumab.

The proportion of patients with 24-week CDI over the duration of the DBP and OLE periods (figure 3B) in patients with a baseline EDSS score of ≥2.0 was numerically higher in patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR at the end of the DBP (year 2: 16.8% vs 13.3%; p = 0.099), at the end of year 3 (20.6% vs 16.6%; p = 0.089), at the end of year 4 (23.7% vs 18.9%; p = 0.057), and at the end of year 5 (25.8% vs 20.6%; p = 0.046). The HR for improvement (time to first 24-week CDI) from baseline to the end of the DBP in patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR was 1.31 (95% CI 0.96–1.78; p = 0.06; figure 3B); after rebaselining at the end of the DBP (i.e., start of the OLE), the HR during the OLE phase was 0.89 (95% CI 0.61–1.31; p = 0.6) (data available from Dryad, figure e-2B, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw).

Patients continuing OCR had a lower mean change from baseline in EDSS score compared with patients switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR, at the end of the DBP (year 2: −0.146 vs 0.032; p < 0.001), during year 3 (−0.118 vs 0.010; p = 0.008), during year 4 (−0.057 vs 0.041; p = 0.06), and during year 5 (−0.043 vs 0.058; p = 0.07) (data available from Dryad, figure e-3, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw).

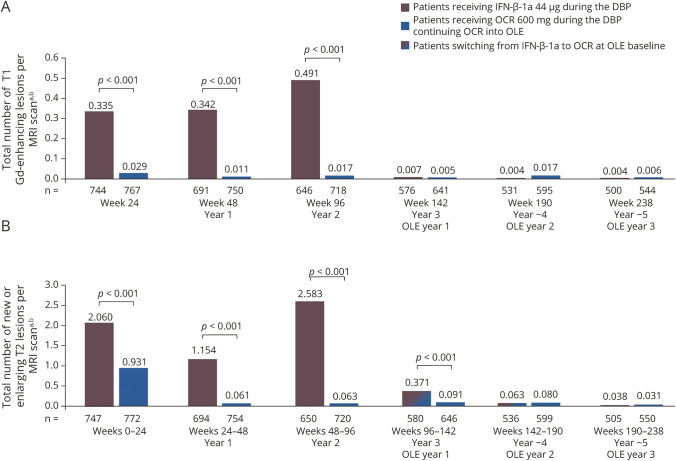

MRI efficacy assessments

Patients receiving continuous OCR maintained the near complete suppression of MRI disease activity seen in the DBP through to year 5 (figure 4, A and B): the unadjusted rate of total T1 Gd-enhancing lesions was 0.017 at the end of the DBP (for year 2 only), 0.005 at year 3, 0.017 at year 4, and 0.006 at year 5; and for new or newly enlarged T2 lesions, the unadjusted rate was 0.063 over year 2, 0.091 over year 3, 0.080 over year 4, and 0.031 over year 5. Patients switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR had almost complete and sustained suppression of MRI lesion disease activity from year 3 to year 5 (figure 4, A and B): the unadjusted rate of total T1 Gd-enhancing lesions was 0.491 at the end of the DBP (year 2), decreasing to 0.007 at year 3, 0.004 at year 4, and 0.004 at year 5; and for new or enlarging T2 lesions, the unadjusted rate was 2.583 over the duration of year 2, decreasing to 0.371 over year 3, 0.063 over year 4, and 0.038 over year 5. In the OLE phase, there was no difference in MRI lesion counts at years 3, 4, and 5 in patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a (p > 0.5, all comparisons; figure 4), except for new or enlarging T2 lesions at year 3, where the number was lower in patients receiving continuous OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a (0.091 vs 0.371; p < 0.001; figure 4B).

Figure 4. Total number of T1 gadolinium (Gd)-enhancing lesions and new or enlarging T2 lesions in the double-blind controlled treatment phase (DBP) and open-label extension (OLE).

(A) T1 Gd-enhancing lesions and (B) new or enlarging T2 lesions in the DBP and OLE. aDBP week 24, DBP year 1, and DBP year 2 data include the intention-to-treat (ITT) population; year 3 (OLE year 1), year 4 (OLE year 2), and year 5 (OLE year 3) data include the OLE ITT population; clinical cutoff date: February 5, 2018. bUnadjusted rate. IFN = interferon; OCR = ocrelizumab.

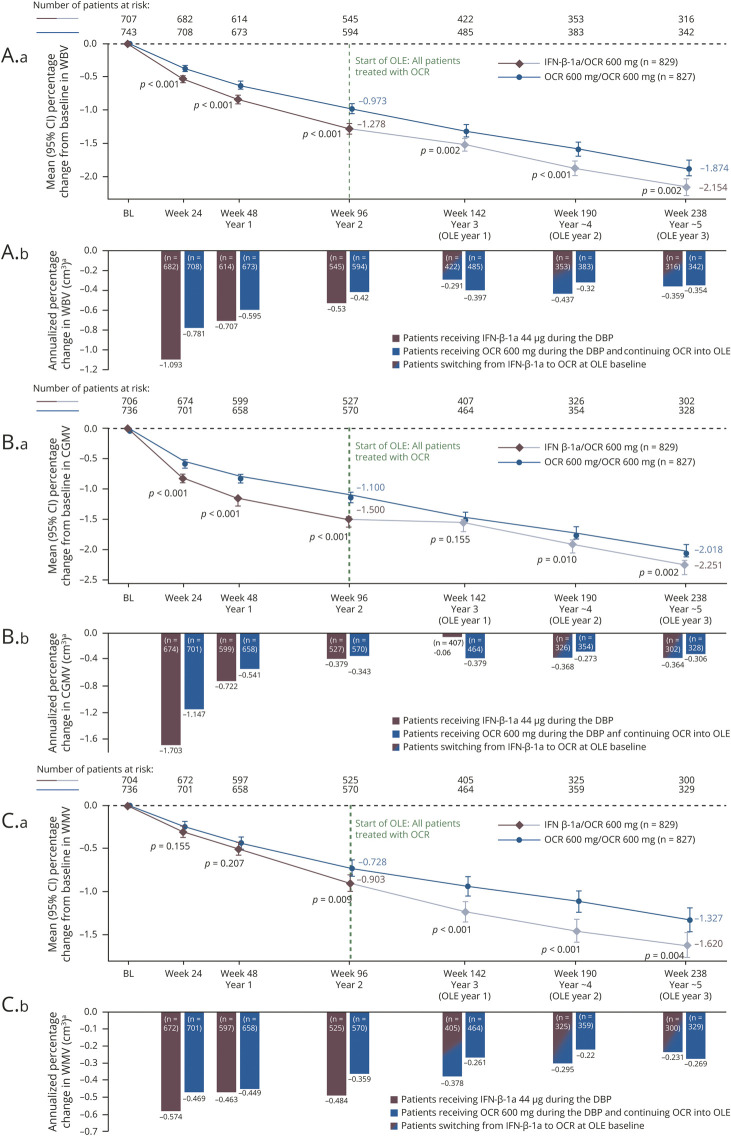

At 5 years (OLE year 3), patients treated continuously with OCR compared with those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR experienced significantly lower brain atrophy measured by change from DBP baseline in WBV, cortical GMV, and WMV (adjusted rate: WBV –1.87% vs −2.15%, cortical GMV −2.02% vs −2.25%, and WMV –1.33% vs −1.62%; p < 0.01 for all comparisons; figure 5, A1, B1, and C1). Similarly, significant differences between patients treated continuously with OCR compared with patients switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR were seen at years 2, 3, and 4 for change from baseline in WBV, cortical GMV, and WMV (adjusted rates: p ≤ 0.01 for all comparisons; figure 5, A1, B1, and C1), except for cortical GMV at year 3, where no difference was found (adjusted rate −1.47% vs −1.56%; p = 0.155; figure 5B1). When expressed as annualized percent change in volume occurring during the preceding 48 weeks, the adjusted rates were generally stable during the OLE phase for patients switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR and those continuing OCR (figure 5, A2, B2, and C2).

Figure 5. Percentage change from baseline and annualized, in whole brain volume (WBV), cortical gray matter volume (CGMV), and white matter volume (WMV) in the double-blind controlled treatment phase (DBP) and open-label extension (OLE).

Percentage change (A.a, B.a, C.a) from baseline and (A.b, B.b, C.b) annualized, in (A) WBV, (B) CGMV, and (C) WMV in the DBP and OLE mixed-effect model of repeated measures (MMRM) plot, intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Pooled OPERA [Rebif] I and OPERA II (clinical cutoff date: February 5, 2018); p values shown for difference in adjusted means. Graph includes patients with assessment at baseline and at least 1 postbaseline value. Estimates are from analysis based on MMRM using unstructured covariance matrix: percentage change = baseline brain volume + geographic region (United States vs rest of the world) + baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale (<4.0 vs ≥4.0) + study + week + treatment + treatment × week (repeated values over week) + baseline brain volume × week. aThe bars represent the annualized change in WBV, CGMV, or WMV occurring during the time period delineated by the axis label and the preceding 24 or 48 weeks. BL = baseline; CI = confidence interval; IFN = interferon; OCR = ocrelizumab.

NEDA in the OLE

In patients treated with OCR compared with IFN-β-1a, the relative proportion of patients with NEDA was increased by 74% in the DBP (OCR 48.5% [n = 369/761] vs IFN-β-1a 27.8% [n = 210/756]; p < 0.001) and by 88% over the duration of the DBP and OLE periods (OCR 35.7% [n = 255/715] vs IFN-β-1a/OCR 19.0% [n = 140/738]; p < 0.001). During the OLE period alone, the proportion of patients with NEDA was 65.4% (n = 409/625) in patients treated continuously with OCR compared with 55.1% (n = 310/563) in those switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR, a relative difference of 19% (p < 0.001).

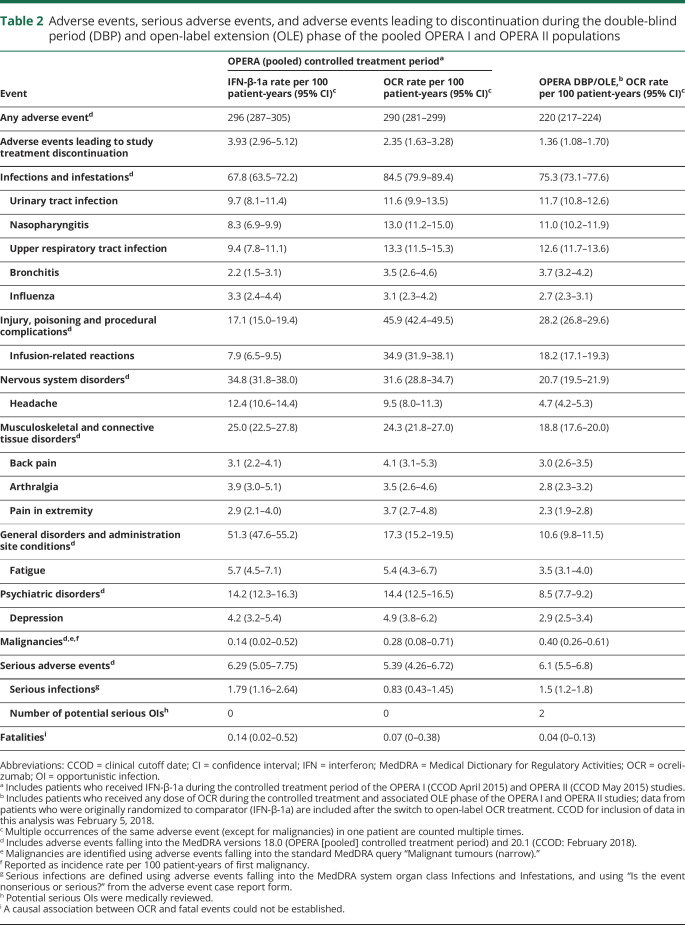

Safety in the OLE

Table 2 summarizes the safety analyses in all patients treated with OCR over a period of 5 years, which includes patients treated continuously with OCR (5 years) and patients switched from IFN-β-1a (3 years). As of February 2018, 1,448 patients with MS received OCR during the DBP and associated OLE periods of the OPERA trials. The rate of adverse events (AEs) in the overall OCR exposure population was 220 (95% CI 217–224) per 100 patient-years, lower than the rate observed at the primary DBP analysis cutoff date (May 2015) for each group (events per 100 patient-years [95% CI], IFN-β-1a: 296 [287–305]; OCR 290 [281–299]). The most common AEs included infusion-related reactions, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and upper respiratory tract infections. Overall, the rate of serious AEs was 6.1 (95% CI 5.5–6.8) events per 100 patient-years, consistent with the rate observed at the primary analysis cutoff date for each group (IFN-β-1a: 6.29 [5.05–7.75]; OCR: 5.39 [4.26–6.72]). The rate of infections per 100 patient-years was 75.3 (95% CI 73.1–77.6), consistent with the rate observed at the primary analysis cutoff date for each group (IFN-β-1a: 67.8 [95% CI 63.5–72.2]; OCR: 84.5 [95% CI 79.9–89.4]).

Table 2.

Adverse events, serious adverse events, and adverse events leading to discontinuation during the double-blind period (DBP) and open-label extension (OLE) phase of the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II populations

The most common serious AEs were classified as infections, which occurred at a rate of 1.5 per 100 patient-years (95% CI 1.2–1.8) over the 5-year period, and this was similar to the rate observed at the primary analysis cutoff date (IFN-β-1a: 1.79 [1.16–2.64]; OCR: 0.83 [0.43–1.45]). The most common serious infections were UTIs and pneumonia. Two potential serious opportunistic infections were reported in the OLE period; both patients recovered with treatment by standard therapies (systemic Pasteurella infection in a patient with RMS following a cat bite; enterovirus-induced fulminant hepatitis in a diabetic patient with RMS, resulting in liver transplant). As of end of April 2019, no cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) were identified in the overall OCR exposure population for the pooled OPERA studies. The crude incidence rate of all malignancies per 100 patient-years in the overall OCR exposure population was 0.40 (0.26–0.61), and at the primary analysis cutoff date the incidence rate for IFN-β-1a was 0.14 (0.02–0.52) and for OCR was 0.28 (0.08–0.71). A list of malignancies from the DBP and OLE phase of the pooled OPERA studies as of February 2018 is provided in the supplemental data (available from Dryad, supplemental data, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw).

The rate per 100 patient-years of AEs leading to treatment withdrawals in the overall OCR exposure population (year 5: 1.36 [95% CI 1.08–1.70]) did not increase over time (rate observed at the primary analysis cutoff date: IFN-β-1a: 3.93 [2.96–5.12]; OCR: 2.35 [1.63–3.28]).

Over 5 study years in the pooled OPERA study population, a reduction in serum immunoglobulin (Ig) levels was observed. At baseline, the number (%) of patients with Ig concentrations below the lower limit of normal (LLN) were 7 (0.5%) for IgG, 17 (1.2%) for IgA, and 7 (0.5%) for IgM. Over 5 study years, for the majority of patients, Ig levels remained above the LLN (data available from Dryad, table e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.stqjq2bzw); the number (%) of patients with a decrease below the LLN at year 5 were 33 (5.4%) for IgG, 31 (5.1%) for IgA, and 164 (29.5%) for IgM.

Discussion

These interim results from the OPERA extension study provide several important insights on the efficacy and safety of long-term (up to 5 years) treatment with OCR in patients with RMS. The low levels of disease activity observed in patients treated with OCR during the 2-year controlled period3 were sustained from years 3–5, suggesting a benefit of earlier treatment and persistence of the effect with maintained therapy. In patients who switched from IFN-β-1a, OCR consistently led to a rapid decrease in relapse activity and an almost complete suppression of MRI activity. Disability accrual occurred at similarly low rates in the 2 groups during the OLE phase but, at the end of year 5, the proportion of patients with CDP from baseline of the DBP was lower in those originally treated with OCR. The safety profile observed in years 3–5 was generally consistent with that observed during the controlled period, with no additional safety findings that suggest potential deleterious effects of long-term exposure to OCR.

In patients treated early and continuously with OCR, consistent and persistent effects were evident on clinical and MRI measures of inflammatory disease activity. ARR remained low over 5 years. Consistent with the effects on relapses, the near complete suppression of subclinical disease activity, as measured by MRI, observed in the DBP was maintained throughout the OLE phase, with few patients exhibiting either T1 Gd-enhancing lesions (0.006 lesions per scan) or new/enlarging T2 lesions (0.031 lesions per scan) at the end of year 5. Patients who started OCR after switching from IFN-β-1a experienced significant decreases in levels of disease activity, with relapse rates and lesion counts becoming similar to those observed in patients on early and continuous OCR at year 3 and consistently maintained through to year 5. The effect of OCR in reducing the relapse rate is of particular relevance to the long-term prognosis, as natural history and long-term follow-up studies of MS disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) show that more frequent relapses early in the disease course, and relapses occurring over the 2- to 3-year interval of a randomized clinical trial, are associated with adverse long-term disability outcomes.7

The benefits of earlier and sustained OCR treatment for measures of disease progression were evidenced by lower levels of clinically evaluated CDP, with only 16.1% of patients who continued OCR experiencing 24-week CDP at the end of the OLE phase (year 5). In patients who switched from IFN-β-1a, a treatment effect of OCR was observed starting in the first year of the OLE, leading to rates of disability progression similar to those seen in patients continuing OCR in the OLE phase. However, a higher proportion of IFN-β-1a–treated patients experienced 24-week CDP by the end of the OLE phase (year 5). Those patients who initiated OCR 2 years earlier accrued significantly less disability progression compared with those switched from IFN-β-1a (16.1% vs 21.3%). Similarly, by the end of the OLE phase (year 5), a significantly higher proportion of patients initiating OCR 2 years earlier achieved improvements in disability compared with patients switching from IFN-β-1a (25.8% vs 20.6%). These results add to the body of evidence that early high-efficacy treatment is more favorable than the traditional escalation approach. A recent observational study demonstrated that patients commencing high-efficacy DMTs, including OCR, early after disease onset accumulate less long-term disability compared with those exposed later in their disease.8–11

OCR also slowed the rate of brain volume loss. At 5 years from DBP baseline, patients on early and continuous OCR experienced lower WBV loss during the DBP compared with IFN-β-1a, and the difference between the 2 groups was maintained throughout the OLE phase. The beneficial effect was also observed in both the white matter and cortical gray matter compartments, with the exception of cortical GMV at year 3 where the absence of a difference might be due to the reversal of pseudoatrophy affecting gray matter in patients switching from IFN-β-1a to OCR.12 In patients with MS, a parenchymal loss of ≥0.4% per year (≥2.0% over a 5-year period) has been proposed as a pathologic atrophy rate.13 The 5-year cumulative WBV loss from DBP baseline in patients treated early and continuously with OCR (−1.87%) was lower than in those that switched from IFN-β-1a (−2.15%). Taken together, our findings converge in demonstrating that patients with RMS who start later with high-efficacy treatment do not catch up on clinical and MRI outcomes reflecting residual functional loss and tissue damage.

The durable efficacy of OCR across multiple endpoints, with an early impact not only on clinical and MRI measures of inflammation but also on disease progression, was accompanied by a safety profile consistent with previous reports.3 This was reflected in the low on-study attrition rates, where almost 90% of all patients who entered the OLE phase completed year 5, indicating that OCR was generally well-tolerated. The reported rates of AEs per 100 patient-years with OCR during the OLE out to year 5 continue to be generally consistent with those seen during the DBP in patients with RMS. Consistent with results of previously reported trials,3,14 the incidence rates of malignancies in patients treated with OCR remain within the range of placebo data from clinical trials in MS and epidemiologic data for this patient population.14,15 A small increase in serious infections has been previously reported during OLE observations in patients with primary progressive MS treated with OCR.16 No cases of PML occurred in the controlled treatment period of the OCR MS clinical trials (pivotal phase III studies and the phase II study) and to date, no cases have been observed in the ongoing OLE of these studies or in the other ongoing MS clinical trials. Outside of clinical trials, as of October 2019, there have been 8 confirmed cases of PML in patients with MS treated with OCR: 7 cases of probable carryover PML (6 switching from natalizumab, 1 from fingolimod); in one case, the patient had not been treated with other DMTs but had contributing risk factors for PML, including old age (78 years) and preexisting grade 1 lymphopenia (which worsened to grade 2 during treatment). No other PML cases with OCR have been reported to date (based on drug product sales as of October 2019, where an estimated 130,000 patients with RMS and PPMS have received OCR treatment for approximately 140,000 patient-years).16 The observed decrease in Ig levels and potential implications for patient safety, such as serious infections, need to be considered in the context of longer follow-up data.

As with other extension studies of DMTs, definitive conclusions related to efficacy outcomes are limited by the absence of a control arm, and the influence of regression to the mean, which has been described in MS studies, cannot be excluded.17 As blinding was not maintained in the OLE phase, some rater assessment bias could have been introduced, although EDSS raters continue to be blinded to all other procedures, and MRI interpretation remains masked in the OLE phase. There is a possibility of selection bias given that participation in the extension was voluntary. However, this is unlikely to be significant as over 94% of patients in both groups who completed the DBP entered the OLE, with 88% of these patients completing year 5. It should also be noted that the disease duration at baseline for the majority of the patients enrolled in the OPERA I/II studies was longer than the 5 years defined in one study as the threshold for early MS,9 but the duration was typical of other clinical trials in the higher-efficacy DMT era. The long-term outcome of ocrelizumab therapy in patient populations with earlier MS disease course requires further study.

Studies that demonstrate the maintenance of long-term efficacy and safety of DMTs are valuable since patients with MS need to receive DMTs over the long term. The results of this analysis of 5-year data from the DBP and OLE of the pooled OPERA studies underscore persistence of the OCR treatment effect and suggest that early and continuous treatment provides sustained long-term benefit. These and other data support the early use of highly effective therapies that impact clinical and MRI measures of disease activity and progression in RMS to optimize short- and long-term patient outcomes.18

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in this trial (including the OPERA Study Steering Committee, which provided study oversight); the independent data monitoring committee for performing data analysis and safety monitoring; and Gisèle von Büren (of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd) for additional critical review of this manuscript and technical advice.

Glossary

- AE

adverse event

- ARR

annualized relapse rate

- CDI

confirmed disability improvement

- CDP

confirmed disability progression

- CI

confidence interval

- DBP

double-blind controlled treatment phase

- DMT

disease-modifying therapy

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- FSS

Functional Systems Score

- Gd

gadolinium

- GMV

gray matter volume

- HR

hazard ratio

- IFN

interferon

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- LLN

lower limit of normal

- MMRM

mixed-effect model of repeated measures

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NEDA

no evidence of disease activity

- OCR

ocrelizumab

- OLE

open-label extension

- OPERA

A Study of Ocrelizumab in Comparison With Interferon Beta-1a (Rebif) in Participants With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis

- PML

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- RMS

relapsing multiple sclerosis

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- WBV

whole brain volume

- WMV

white matter volume

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

CME Course: NPub.org/cmelist

Study funding

This research was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland. Terence Smith of Articulate Science, UK, wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on input from the authors; his work was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

Disclosure

S.L. Hauser serves on the board of trustees for Neurona and on scientific advisory boards for Alector, Annexon, Bionure, Molecular Stethoscope, and Symbiotix and has received travel reimbursement and writing assistance from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd for CD20-related meetings and presentations. L. Kappos' institution, the University Hospital Basel, has received research support and payments that were used exclusively for research support for L. Kappos' activities as principal investigator and member or chair of planning and steering committees or advisory boards for trials sponsored by Actelion, Addex, Almirall, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, CLC Behring, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Genentech, Inc, GeNeuro SA, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Mitsubishi Pharma, Novartis, Octapharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Receptos, Sanofi, Santhera, Siemens, Teva, UCB, and XenoPort; has received license fees for Neurostatus products; and has received research grants from the European Union, Novartis Research Foundation, Roche Research Foundation, Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Society, Swiss National Research Foundation, and Innosuisse. D.L. Arnold has received personal fees for consulting from Acorda, Albert Charitable Trust, Biogen, Celgene, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Frequency Therapeutics, MedImmune, MedDay, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, and Wave Life Sciences; grants from Biogen, Immunotec, and Novartis; and an equity interest in NeuroRx Research. A. Bar-Or has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Genentech, Inc, GlaxoSmithKline, Guthy-Jackson/GGF, MedImmune, Merck/EMD Serono, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Ono, Receptos, and Sanofi-Genzyme and has received research support from Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme. B. Brochet has received research support from Bayer, Merck, Genzyme, Biogen, Novartis, Roche, Actelion, MedDay, and Teva and has consulting agreements with Novartis and Biogen. R.T. Naismith reports financial relationships with Alkermes, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech, Inc, Genzyme, Novartis, and TG Therapeutics. A. Traboulsee has received research support from Sanofi Genzyme, Roche, Chugai, Novartis, and Biogen; has received consulting fees from Sanofi Genzyme, Roche, Teva Neuroscience, Novartis, Biogen, and EMD Serono; and has received honoraria for his involvement in speaker bureau activities for Sanofi Genzyme and Teva Neuroscience. J.S. Wolinsky has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with AbbVie, Acorda Therapeutics, Alkermes, Biogen, Bionest, Celgene, Clene Nanomedicine, EMD Serono, Forward Pharma A/S, GeNeuro, GW Pharma, MedDay Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Otsuka, PTC Therapeutics, Roche/Genentech, and Sanofi Genzyme; royalties are received for out-licensed monoclonal antibodies through UTHealth from Millipore Corporation. S. Belachew was an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd during the completion of the work related to this manuscript. S. Belachew is now an employee of Biogen (Cambridge, MA), which was not in any way associated with this study. H. Koendgen is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. V. Levesque is an employee of Genentech, Inc, and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. M. Manfrini is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. F. Model is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. S. Hubeaux is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. L. Mehta was an employee of Genentech, Inc., and a shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. during the completion of the work related to this manuscript. L. Mehta is now an employee of Alder Biopharmaceuticals Inc (Bothell, WA), which was not in any way associated with this study. X. Montalban has received speaker honoraria and travel expense reimbursement for participation in scientific meetings, been a steering committee member of clinical trials, or served on advisory boards of clinical trials for Actelion, Almirall, Bayer, Biogen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Genzyme, Merck, Novartis, Octapharma, Receptos, Sanofi, Teva, and Trophos. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.DiLillo DJ, Hamaguchi Y, Ueda Y, et al. Maintenance of long-lived plasma cells and serological memory despite mature and memory B cell depletion during CD20 immunotherapy in mice. J Immunol 2008;180:361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein C, Lammens A, Schäfer W, et al. Epitope interactions of monoclonal antibodies targeting CD20 and their relationship to functional properties. MAbs 2013;5:22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith SM, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, et al. Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage 2002;17:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Guizard N, Fonov VS, Narayanan S, Collins DL, Arnold DL. Jacobian integration method increases the statistical power to measure gray matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin 2014;4:10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodin DS, Reder AT, Bermel RA, et al. Relapses in multiple sclerosis: relationship to disability. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;6:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:536–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA 2019;321:175–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naegelin Y, Naegelin P, von Felten S, et al. Association of rituximab treatment with disability progression among patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:274–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He A, Merkel B, Zhovits L, et al. Early start of high-efficacy therapies improves disability outcomes over 10 years. Presented at the 34th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS); October 10–12, 2018; Berlin. Poster P919.

- 12.Battaglini M, Giorgio A, Luchetti L, et al. Dynamics of pseudo-atrophy in relapsing-remitting MS patients treated with interferon beta-1a as assessed by monthly brain MRI. Presented at the 34th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS); October 10–12, 2018; Berlin. Poster P798.

- 13.De Stefano N, Stromillo ML, Giorgio A, et al. Establishing pathological cut-offs of brain atrophy rates in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser SL, Kappos L, Montalban X, et al. Safety of ocrelizumab in multiple sclerosis: updated analysis in patients with relapsing and primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Presented at the 34th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS); October 10–12, 2018; Berlin, Germany. Poster P1229.

- 15.Nørgaard M, Veres K, Didden EM, Wormser D, Magyari M. Multiple sclerosis and cancer incidence: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;28:81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauser SL, Kappos L, Montalban X, et al. Safety of ocrelizumab in multiple sclerosis: updated analysis in patients with relapsing and primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Presented at the 14th World Congress of Neurology Meeting; October 27–31, 2019; Dubai, UAE.

- 17.Martínez-Yélamos S, Martínez-Yélamos A, Martín Ozaeta G, Casado V, Carmona O, Arbizu T. Regression to the mean in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2006;12:826–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziemssen T, De Stefano N, Sormani MP, Van Wijmeersch B, Wiendl H, Kieseier BC. Optimizing therapy early in multiple sclerosis: an evidence-based view. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015;4:460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level data through the clinical study data request platform (vivli.org). Further details on Roche's criteria for eligible studies are available at vivli.org/members/ourmembers. For further details on Roche's Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm.