Abstract

Hoarding disorder has significant health consequences, including the devastating threat of eviction. In this pilot study, critical time intervention (CTI), an evidence-based model of case management shown to be effective for vulnerable populations, was adapted for individuals with severe symptoms of hoarding disorder at risk for eviction (CTI-HD). Of the 14 adults who enrolled, 11 participants completed the 9-month intervention. Completers reported a modest decrease in hoarding severity, suggesting that, while helpful, CTI-HD alone is unlikely to eliminate the risk of eviction for individuals with severe symptoms of hoarding disorder.

Clinicaltrials.gov Registry Numbers: NCT02367430

Keywords: hoarding disorder, hoarding, critical time intervention

Introduction

Hoarding disorder, characterized by difficulty discarding and accumulation of clutter, prevents the normal use of the living space and causes distress. Hoarding disorder causes significant public health consequences, including fire hazards, unsanitary living conditions, and structural damage that may lead to eviction and/or homelessness due to violation of building, fire, or property maintenance codes. In one community eviction-prevention agency, the prevalence of hoarding behaviors was 4 to 10 times higher in their client population compared to the general population (22% vs. 2–6%, respectively) (1). Evictions are a major cause of homelessness (2,3). A UK study evaluated the prevalence of hoarding disorder in 78 randomly selected homeless individuals newly admitted to Salvation Army shelters (Mataix-Cols D, Grayton L, Bonner A, Luscombe C, Taylor PJ, van den Bree M. A putative link between compulsive hoarding and homelessness: A pilot study [submitted for publication]): up to 21% of these individuals endorsed hoarding symptoms and 8% reported that hoarding problems directly contributed to their homeless state.

Despite the impairment and negative repercussions of the clutter, individuals with hoarding disorder are often hesitant to seek treatment, possibly due to the stigma associated with the disorder (4). Instead, these individuals often come to the attention of non-mental health agencies (e.g., fire department, police) during emergencies (e.g., pest infestation, fire, or eviction) (1, 4, 5); if they do seek mental health treatment, it is often for the treatment of other disorders. Therefore, resources such as community eviction prevention agencies represent an important way to identify individuals with hoarding disorder who may benefit from treatment and may not otherwise seek it out.

To increase the likelihood for individuals with hoarding disorder to utilize community resources and prevent eviction, the evidence-based case management model Critical Time Intervention (CTI) was adapted and pilot tested with individuals with hoarding disorder who were concerned that they were at risk for eviction. CTI is a well-established, cost-effective model of case management designed to help vulnerable individuals with mental illness through particularly difficult periods in their lives (6). CTI was originally designed as a way to prevent previously homeless men with severe mental illnesses from returning to homelessness during the transition period from institutional living (hospital, shelter, etc.) to community living (community housing) (6). Adaptation of CTI for individuals with hoarding disorder (CTI-HD) uses the threat of eviction, including receiving an eviction notice or concern about eviction, as the critical time period.

The authors hypothesized CTI-HD would be an effective intervention for individuals with hoarding disorder who were at risk for eviction and enrolled 14 participants with hoarding disorder at risk for eviction into the CTI-HD program. The feasibility of CTI-HD was assessed via three outcomes: rate of participant study completion at nine months, usage of six services and resources offered, and change in hoarding severity as measured by the Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R) and Clutter Image Rating Scale (CIR).

Critical Time Intervention for Hoarding Disorder

The model.

CTI-HD’s guiding principles include: collaborative and flexible decision-making, ongoing engagement, continued assessment, and a time-limited approach. The goal of CTI-HD is to provide supports and resources during a critical risk period for eviction, in order to prevent negative outcomes (e.g. eviction, homelessness) and promote positive outcomes (e.g. decrease in hoarding disorder symptoms). Continuity of support is hypothesized to lead to better outcomes. For this study, case managers helped increase the number and strength of participants’ ties to community resources by developing rapport, gathering information about eviction risk, and providing support over a nine-month period.

In Phase 1 of the CTI-HD program (first three months), the case managers used engagement strategies to establish rapport with each client and lay the foundation for the intervention that included the following specific activities: (a) assessing the current eviction risk and risk status, (b) assessing mental health needs with a full psychiatric evaluation and referral to providers for medication management of comorbid conditions as needed, (c) referral to an evidence-based facilitated self-help support group called Buried in Treasures workshop (BIT) (8), which includes psycho-education about hoarding disorder, developing ways to tolerate urges to acquire items, and building skills for parting with possessions, (d) connecting the client to free legal counseling, entitlement registration clinics, and accompanying the client to initial appointments, (e) taking inventory of clients current and potential support network, and organizing family meetings, and (f) engaging in frequent face-to-face meetings (at least one check-in per week). Weekly home visits to assess level of clutter and weekly phone check-ins to assess progress of decluttering efforts were also available.

In Phase 2 (four months), case managers focused on titrating down their involvement, conducted one check-in per two weeks, assessed the functioning of support network and mental health and other resources, and adjusted plans for delivery of services as necessary. Case managers also anticipated risk factors for relapse and worked with clients to enhance hope that if risk factors could be anticipated and avoided, the likelihood of relapse could be reduced.

In Phase 3 (two months), case managers sought to optimize community support networks, conducted one check-in per month, and planned termination. Throughout all phases of the intervention, case managers tracked level of satisfaction and attendance of utilized referrals as well as the progress of decluttering efforts.

Application.

Preparation of the pilot study included adapting the CTI manual for use with individuals with hoarding disorder who are at risk for eviction and consulting with CTI experts (D.H. & S.C.). Specifically, key elements of the adaptation included using the threat of eviction, including receiving an eviction notice or concern about eviction, as the critical time period, offering evidence-based hoarding disorder treatment (e.g., BIT), and connection to hoarding specific needs surrounding eviction (e.g., legal services). Case managers were hired and trained in delivering the nine-month CTI model in three distinct phases (as detailed above). A local resource guide for referrals was created by building relationships with community providers and the director of an eviction intervention service (A.T.).

Participants.

With institutional review board approval, eligible adults with hoarding difficulties were recruited (January 2013 to July 2014) through flyers, social media advertisements, and referrals from housing authorities, a local non-profit eviction intervention service, and other external providers. All participants provided written informed consent. They were required to meet the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria for hoarding disorder (as assessed by the Structured Interview for Hoarding Disorder) and to report concern with the threat of eviction due to clutter and/or receiving an eviction notice. Potential participants were excluded if they were severely depressed (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale > 30) or at risk of suicide (Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale > 4).

Procedures and Assessments.

Potential participants were screened and completed an evaluation, including the Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R) and Clutter Image Rating Scale (CIR), which were used to track changes in hoarding symptoms during the CTI-HD intervention and were collected at baseline, 3, 6, and 9 months. The SI-R is a 23-item self-report questionnaire that measures hoarding symptoms and has good test-retest reliability (kappa = 0.86). The CIR is a 3-item picture scale administered by independent evaluators (S.V., A.S., and E.J.) to assess level of clutter. The CIR has high internal consistency (αs ranging from 0.77 to 0.91) and established test-retest reliability.

Results.

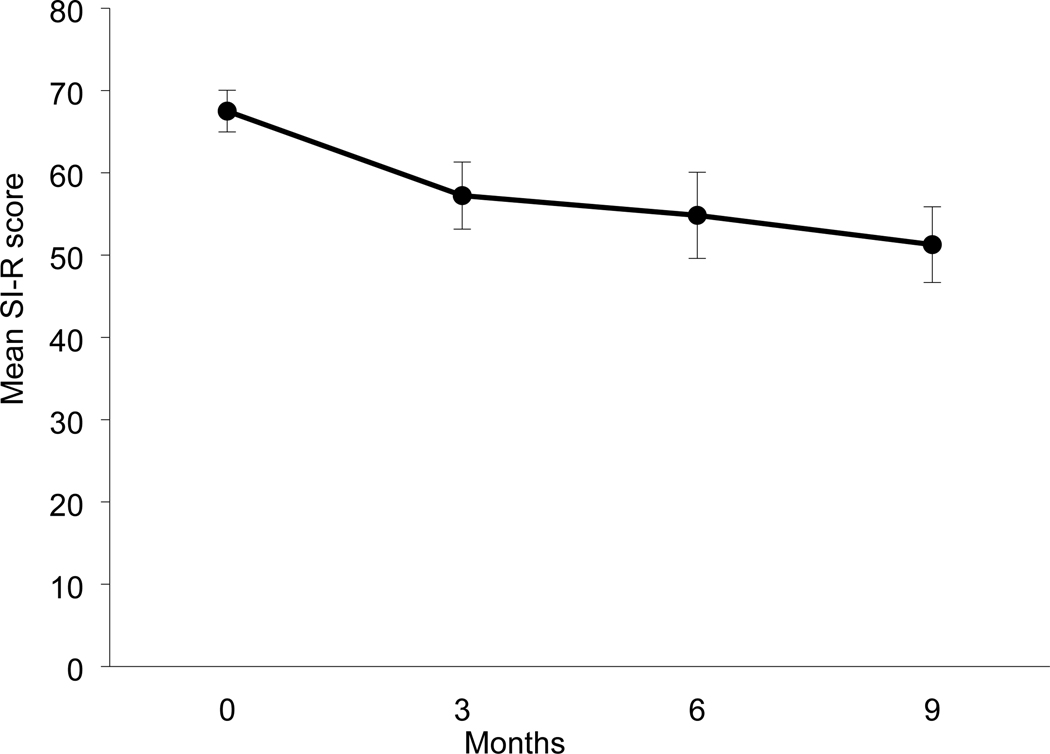

Of the 14 adults who enrolled, 11 participants completed the nine-month intervention (80%). Participants (N=14) were mostly female (N=10, 71%), with mean age of 60.6 years (SD = 8.0). Eight participants were Caucasian, five were African American, and one was Hispanic. Participants met criteria for major depression (n=8), specific phobia (n=5), dysthymic disorder (n=3), panic disorder (n=3), binge eating disorder (n=2), mood disorder due to a general medical condition (n=1), and agoraphobia without panic disorder (n=1). Of the six CTI-HD program treatments and services offered to the 14 participants, the following were utilized: facilitated self-help group (n=14), legal counseling (n=9), decluttering assistance (n=9), psychiatric evaluation (n=7), coordination of family and support network (n=6), and entitlement registration (n=4). Figure 1 shows the change in hoarding severity—a 25% decrease in mean SI-R score. Challenges included difficulty scheduling appointments, with four participants requesting rescheduling at least once.

Figure 1:

Mean Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R) Changes Over Time (N =14)

Error bars represent 1 standard error from the mean.

Discussion

This pilot study was the first study to address the gap in treatment resources for individuals with hoarding disorder by providing a low-cost, flexible, and time-limited community based program to improve quality of life and prevent eviction. The findings indicate the feasibility of the intervention: a high rate of retention (11 out of 14 participants; 80%), facilitated self-help group (BIT) as the most utilized resource (100% enrolled in the group), and a 25% decrease in hoarding symptoms as measured by the SI-R and CIR. No participant was evicted.

The likelihood of participants completing the BIT intervention were similar to those of a study that used cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) group intervention for individuals with hoarding disorder, in which 67% of the sample (30 out of 45 participants) completed study procedures (7). Two other studies assessed the retention of participants in group and individual therapy interventions for hoarding disorder. Frost, Ruby, and Shuer (2012) reported 95% of the sample (41 out of 43 participants) completed a thirteen-week peer-lead BIT group (8). Another study reported 100% of the sample (12 participants) completed a 17-week individual CBT therapy for hoarding disorder (9).

The observed decreases in hoarding severity were comparable with other more intensive and costly treatments (8). Over the course of nine months, hoarding symptom severity decreased by 25% in this sample as measured by the SI-R. In comparison, Gilliam et al. (2011) reported a 26% decrease in SI-R ratings for group CBT for hoarding disorder (7); Frost, Ruby, and Shuer (2012) found a 25% decrease in SI-R ratings for a BIT group (8); and Ayers et al. (2011) reported a 21% decrease in SI-R ratings for individual CBT therapy for hoarding disorder (9). In our sample, the level of clutter, as assessed by the CIR decreased (on average from 6 to 5), but the level of clutter was still severe enough to put clients at continued risk for eviction.

The leaders of CTI-HD met with the New York City Office of Mental Health as well as Supportive Housing of New York and informed officials about the CTI-HD program, system barriers identified, and lessons learned. Specifically, one lesson learned was that difficulty in communication and organization may reflect the inherent nature of hoarding disorder.

Given the modest effects on clutter and continued risk for eviction for people with severe symptoms of hording disorder, a treatment that goes beyond CTI-HD is needed. Future studies should explore which interventions are most effective in addressing residual clutter as well as maximizing community stakeholder engagement (10) and participant engagement in hoarding disorder treatment modalities.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the individuals who generously donated their time to participate in this research study. We appreciate Dr. Lisa Dixon’s feedback on adapting the CTI manual for use with individuals who have HD and are at risk for eviction.

Funding Support: This study was supported by a grant from the New York Office of Mental Health Policy Scholars Program (Dr. Rodriguez), by the New York Presbyterian Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (Dr. Rodriguez), K23MH092434 (Dr. Rodriguez) and K24MH09155 (Dr. Simpson) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Financial disclosures:

In the last three years, Dr. Simpson has received royalties from Cambridge University Press and UpToDate, Inc., research grant support from Biohaven Inc., and a stipend from JAMA for her role as Associate Editor at JAMA Psychiatry.

Dr. Rodriguez has served as a consultant for Allergan, BlackThorn Therapeutics, Rugen Therapeutics, and Epiodyne, receives research grant support from Biohaven Inc., and a stipend from APA Publishing for her role as Deputy Editor at The American Journal of Psychiatry. The other authors report no additional financial or other relationships relevant to the subject of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodriguez CI, Herman D, Alcon J, et al. : Prevalence of hoarding disorder in individuals at potential risk of eviction in New York City: a pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis 200:91–4, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crane M, Byrne K, Fu R, et al. : The causes of homelessness in later life: findings from a 3-nation study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 60:S152–9, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Laere I, De Wit M, Klazinga N: Preventing evictions as a potential public health intervention: Characteristics and social medical risk factors of households at risk in Amsterdam. Scand J Public Health 37:697–705, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams L: Hoarding: a community health problem. Health Soc Care Community 8:229–34, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez C, Panero L, Tannen A: Personalized intervention for hoarders at risk of eviction. Psychiatr Serv 61:205, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, Felix A, Tsai WY, & Wyatt RJ (1997). Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a “critical time” intervention after discharge from a shelter. American journal of public health, 87(2), 256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilliam CM, Norberg MM, Villavicencio A, et al. : Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: an open trial. Behav Res Ther 49:802–7, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost RO, Ruby D, Shuer LJ: The Buried in Treasures Workshop: waitlist control trial of facilitated support groups for hoarding. Behav Res Ther 50:661–7, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayers CR, Wetherell JL, Golshan S, et al. : Cognitive-behavioral therapy for geriatric compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 49:689–94, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson J, Wilkerson E, Filippou-Frye M, et al. : A Workshop to Engage Community Stakeholders to Deliver Evidence-Based Treatment for Hoarding Disorder: A Pilot Study. Psychiatr Serv 68 (12):1325–1326, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]