Highlights

-

•

Seizure frequency remained stable for most patients during the lockdown period.

-

•

Comorbidities such as behavioral and sleep disorder were more affected than epilepsy.

-

•

Due to lockdown, visits were canceled/postponed for 41.0%.

-

•

Patients/caregivers who had remote consultation were mostly satisfied.

-

•

Most of patients/caregivers are willing to embrace telemedicine for epilepsy care.

Keywords: Pediatric epilepsy, COVID-19, Telemedicine, Remote consultation, Telehealth, Lockdown

Abstract

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted care systems around the world. We assessed how the COVID-19 pandemic affected children with epilepsy in Italy, where lockdown measures were applied from March 8 to May 4, 2020. We compiled an Italian-language online survey on changes to healthcare and views on telehealth. Invitations were sent to 6631 contacts of all patients diagnosed with epilepsy within the last 5 years at the BambinoGesù Children’s Hospital in Rome. Of the 3321 responses received, 55.6% of patients were seizure-free for at least 1 year before the COVID-19-related lockdown, 74.4% used anti-seizure medications (ASMs), and 59.7% had intellectual disability. Only 10 patients (0.4%) became infected with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Seizure frequency remained stable for most patients during the lockdown period (increased in 13.2%; decreased in 20.3%), and seizure duration, use of rescue medications, and adherence to treatment were unchanged. Comorbidities were more affected (behavioral problems worsened in 35.8%; sleep disorder worsened in 17.0%). Visits were canceled/postponed for 41.0%, but 25.1% had remote consultation during the lockdown period (93.9% were satisfied). Most responders (67.2%) considered continued remote consultations advantageous. Our responses support that patients/caregivers are willing to embrace telemedicine for some scenarios.

1. Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic, caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), spread in few months from a small focus in Wuhan (Hubei province, China) to over 28 million people worldwide, causing over 910 thousand deaths to date (Coronavirus Research Center, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html visited on September 11, 2020). Several countries independently adopted strict containment measures to slow the local spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. In Italy, widespread lockdown measures were applied from March 8 to May 4, 2020 that restricted physical contacts, individual movement, and dramatically changed healthcare services, most notably for patients with chronic diseases, with increased adoption of telehealth tools [1].

Prevalence of epilepsy in children ranges from 3.2 to 5.5 per 1000, being highest in the first year of life, but matching adult rates by the end of the first decade [2]. Epilepsy in children is the second greatest neurological disorder burden worldwide [3], often associated with cognitive and psychiatric comorbidities [4], stigma [5], and high economic costs [6]. The most severe pediatric epilepsies are developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEE), which have a variety of etiologies, and are often resistant to epilepsy treatment except to improve developmental outcome.

We aimed to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected children with epilepsy in Italy, one of the countries most affected early in the pandemic. We created and administered online an Italian-language survey on how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed healthcare delivery to children with epilepsy and views of patients and their caregivers on the use of telehealth in the care of children with epilepsy.

2. Material and methods

We compiled 45 questions for all patients diagnosed with “epilepsy” within the last 5 years at the Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome. The questionnaire comprised selection from both written options and open responses, and was subdivided into five sections: demographics, baseline information (prior to pandemic), change during COVID-19-lockdown period, use of remote medical assistance during COVID-19-related lockdown, and possibility to use remote medical assistance after COVID-19-related lockdown period.

The questionnaire guaranteed anonymity and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bambino Gesù Children Hospital in Rome. The lockdown period in Italy was from March 8 to May 4, 2020. Invitation to fill in the questionnaire was sent to 6631 contacts (patients and caregivers) by short message service (SMS) on May 8, 2020 and the link to the questionnaire remained open for 23 days.

2.1. Statistical methods

Frequencies are presented for categorical variables and data were summarized with descriptive statistics. A chi‐square test or Fisher’s exact test was performed, as appropriate. A P value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical tests were two‐tailed. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org/).

3. Results

We received 3321 responses to the survey (50% response rate) and all questions were answered in 2012 responses (60.6% of 3321). Most responders were caregivers (96.6%; Table 1 ). Patients represented were 52.4% male and 82.5% were younger than 18 years. For 57.6% of responses, patients lived in the same region as the Bambino Gesù Hospital (Lazio); responders spanned 19 other Italian regions.

Table 1.

Frequency table for selected questionnaire responses on demographic and clinical data before the COVID-19-pandemic lockdown measures in Italy.

| Demographic and pre-COVID-19 pandemic lockdown | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Responders | 3321 (100) |

|

3209 (96.6) |

|

112 (3.4) |

| Patient’s age | |

|

72 (2.2) |

|

529 (15.9) |

|

1394 (41.9) |

|

746 (22.5) |

|

580 (17.5) |

| Gender | |

|

1741 (52.4) |

|

1580 (47.6) |

| Italian region of domicile | |

|

1914 (57.6) |

|

121 (3.6) |

|

62 (1.9) |

|

178 (5.4) |

|

396 (11.9) |

|

21 (1) |

|

8 (<1) |

|

4 (<1) |

|

20 (<1) |

|

36 (1.1) |

|

42 (1.3) |

|

9 (<1) |

|

2 (<1) |

|

233 (7.0) |

|

47 (1.4) |

|

102 (3.1) |

|

19 (0.6) |

|

74 (2.2) |

|

15 (0.5) |

|

18 (0.5) |

| Time from epilepsy diagnosis | |

|

452 (13.6) |

|

1232 (37.1) |

|

1637 (49.3) |

| ASM ongoing | |

|

2471 (74.4) |

|

850 (25.6) |

| Number of ASMs (% of 2450 responders) | |

|

1198 (48.9) |

|

682 (27.8) |

|

343 (14.0) |

|

227 (9.3) |

| Comorbidity associated to epilepsy (% of 2711 responders) | |

|

1621 (59.8) |

|

1254 (46.3) |

|

1201 (44.3) |

|

216 (7.9) |

|

296 (10.9) |

Before the COVID-19-related lockdown, 55.6% of patients were seizure-free for at least 1 year; the remaining patients had seizures with frequency from daily to sporadic. Anti-seizure medications (ASMs) were being taken by 74.4% of patients, 59.7% of patients had intellectual disability and 44.3% had behavioral disturbances. Other clinical data before and during the COVID-19-pandemic lockdown measures in Italy are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 .

Table 2.

Frequency table for selected questionnaire responses on clinical data during the COVID-19-pandemic lockdown measures in Italy.

| Changes during COVID-19 pandemic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Seizure frequency during lockdown period (% of 1387 responders) | |

|

921 (66.4) |

|

184 (13.3) |

|

282 (20.3) |

| Behavioral disturbances (% of 2340 responders) | |

|

839 (35.9) |

|

859 (36.7) |

|

642 (27.4) |

| Sleep disturbances (% of 2340 responders) | |

|

398 (17.0) |

|

685 (29.3) |

|

1257 (53.7) |

| Major concerns during COVID19 pandemic (% of 2568 responders) | |

|

1571 (61.2) |

|

843 (32.8) |

|

392 (15.3) |

|

464 (18.1) |

|

484 (18.8) |

| Rehabilitation treatment (% of 2568 responders) | |

|

152 (5.9) |

|

194 (7.6) |

|

838 (32.6) |

|

197 (7.7) |

| Difficulties in getting drugs (% of 2377 responders) | |

|

187 (7.9) |

|

63 (2.6) |

|

47 (2.0) |

|

2080 (87.5) |

3.1. Changes during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

During the lockdown period, seizure frequency was reported to have increased in 13.2% and decreased in 20.3% of patients (Table 2). Behavioral problems worsened in 35.8% of patients and sleep disorder worsened in 17.0% of patients, with 2.2% of those requiring pharmacological treatment.

Rehabilitation program was interrupted due to temporary suspension of service in 33% of responders, though 8.2% of patients continued rehabilitation under changed circumstances (private, home rehabilitation therapy, tele-rehabilitation); only 6.5% reported no problem/difference compared with the pre-lockdown period.

No major difference was evident for the use of rescue medications between the pre-lockdown and lockdown period (13.4% vs 11.3%). Treatment adherence was also reported as unchanged in 91.8% of cases.

The most frequent concerns were on the possibility of infection from visiting the hospital for routine visits or the emergency department for prolonged or subsequent seizures (Table 2). Another frequent concern was on supply of drugs; however, only 12.6% of responders reported difficulties in obtaining ASMs: 7.9% because ASMs were not available in pharmacy, 2.7% for problems in reaching the pharmacy, and 2.0% for lack of prescription.

Only 11.4% of responders considered epilepsy as a risk factor for COVID-19. Overall, ten patients (0.4%) and 24 of their relatives had SARS-CoV-2 infection.

3.2. Care for epileptic patients during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

For 41.0% (937/2283) of patients, the routine visit for epilepsy was postponed; these were mostly patients coming from outside Lazio (P < 0.05). Reasons for cancelation varied: 64.4% of patients due to fear of infection with SARS-CoV-2; 23.9% due to the neurological condition being stable. Only 11.6% canceled because of SARS-CoV-2 infection or contact with subjects with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Most responders (85.0%) had no difficulties in contacting their epileptologist. The contact media was reported as telephone in 58.4%, email in 44.2%, text messages in 22.7%, and video-call in 1.4% cases. Only 18.9% of patients had a face-to-face visit compared with 25.1% who had a structured remote-consultation for epilepsy. Patients who had a remote consultation were mostly from outside Lazio (P < 0.05).

Of those with remote consultations, 93.9% were satisfied, most commonly citing the convenience of having the consultation at home (50.0%) and a shorter waiting list (23.9%) as drivers. The 6% unsatisfied/disappointed with the remote consultation cited problems with internet connection (61.1%) and considered remote consultation inadequate for their purposes (20.2%).

Psychologic consultations were reported for 23.6% of patients, reasons for which were behavioral problems (36.9%), support for problems related to changes of routine life to due to lockdown (31.7%), anxious state (38.1%), and depression (18.6%). Only 13.6% of patients had a consultation for follow-up.

3.3. Considerations on telehealth for the care of epilepsy beyond the COVID-19 pandemic

Remote consultation was considered by 67.2% of responders as a valid tool for routine visits for the care of patients with epilepsy after the lockdown period. This opinion was most frequent among patients from outside Lazio (P < 0.05).

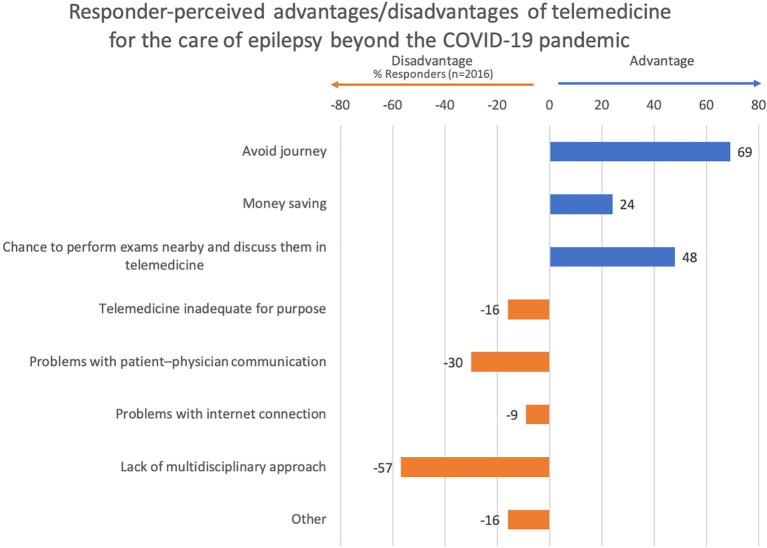

Perceived advantages included avoidance of long journeys and economics (Fig. 1 ). Many responders (48.3%) would consider a remote consultation appropriate to discuss locally performed tests (blood test, ASM blood levels, EEG, brain MRI), planning of examinations (70.9%), and delivery of reports (79.7%). Remote consultations were considered inappropriate for neurological assessment (60.7%) and psychological consultation (59.6%).

Fig. 1.

Responder-perceived advantages and disadvantages of telemedicine for the care of epilepsy beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. 1443 patients answered about advantages: the major was to avoid journey, followed by the chance to perform exams nearby and discuss them in telemedicine, and money saving. 2016 patients answered about disadvantages: the major was the lack of multidisciplinary approach, followed by problem with patient-physician communication. 16% considered this mean of communication inadequate to the purpose and 9% had problems with internet connection.

4. Discussion

We investigated the effect of COVID-19-pandemic on the particularly vulnerable population of pediatric patients with epilepsy. These patients were not highly susceptible to COVID-19: only ten patients (0.4%) became sick. Viral infection is a risk factor for seizures in children with certain DEEs with fever sensitivity, such as Dravet Syndrome and SCN1A-related phenotypes [7]. In our cohort, epilepsy did not worsen during the lockdown period; for most patients, seizure frequency remained stable and seizure duration, use of rescue medications, and adherence to treatment were unchanged by lockdown. This low influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on epilepsy in pediatric patients may be related to the high rate of mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 in the general pediatric populations [8].

In contrast, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on comorbidities was greater, mostly on behavior and sleep, probably due to enforced changes in routines due to the COVID-19-related lockdown [9]. Similar results were reported in a cohort of patients with DEE in Spain, in which twice as many patients had worsening of behavioral problems (30%) than had increased seizure frequency (14.1%) [10]. Our data concur (behavioral worsening, 35.8%; increase in seizure frequency, 13.2%) – differences likely accountable to our inclusion of types of epilepsies other than DEE.

Generally, care of patients changed dramatically during the lockdown period [9], [11], [12]. In regions with high COVID-19 burden, hospitals restructured and postponed, rescheduled, or even canceled outpatient visits by patients with chronic disorders, including epilepsy, both to respect physical distancing rules and to aid in resourcing for managing SARS-CoV-2 infections [1], [13].

Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital has a tertiary care epilepsy center to which patients with more complex epilepsy are referred. Patients are often refractory to medical therapy, thus requiring frequent and multidisciplinary follow-up visits. Of our patients, 41.0% had canceled or postponed visits for epilepsy and 36% had interrupted motor and speech therapies. However, 23% of our patients – mainly those who had the greatest difficulties to travel – had a remote consultation during the lockdown period and almost all were satisfied with this type of assistance.

Most responders (67%) considered that remote consultation would have some advantages, such as to avoid long journeys (69%) and save money (24%) (Fig. 1). Cost savings for patients (in terms of transportation, accommodation, and missed work) with telemedicine technology were demonstrated in previous studies [14], [15], which also showed a similar high level of satisfaction among patients with telemedicine as suggested from our survey [14].

Most responders (86.4%) had been affected by epilepsy for at least one year, which may have contributed to their willingness to participate in a remote consultation. Of the few concerns on telehealth, the ability to have a multidisciplinary consultation in a single session was the most frequent (Fig. 1). Other repeated concerns were about the suitability for neurological physical assessment and psychological consultation; patients considered remote assistance suitable only to discuss about performed exams, planning of exams, and delivery of reports.

In the few other studies on the use of telemedicine for the care of patients with epilepsy, patients assisted with either telemedicine or in-person clinic were similar in seizure control and medication compliance, very low utilization of emergency rooms, and few hospitalizations [16]. For patients at epilepsy onset, clinic visit would still be preferable for both diagnosis and neurological assessment, which might require a hospital setting [14], [17], as well as for beginning the physician–patient relationship [16]. A limitation of the study is the response bias. Responder anonymity means that we are unable to comment on non-responders, but considering demographic and clinical results (age, gender, age of disease, number of patients on treatments, patients with comorbidities), we might argue that our real-world experience seems to reflect the general population of patients affected by epilepsy which are followed in our hospital.

5. Conclusions

Our real-world experience supports that patients are willing to embrace telehealth and raises the question of whether to continue use of telehealth beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. We hope that continued use will clarify the patients and clinical scenarios for which telehealth has outcomes comparable with traditional outpatient-care.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the patients and their families for participation in this study. We also thank Dr. David Macari for English editing of the text.

Disclosure

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. We have no conflict of interest for this paper. This article was not funded.

References

- 1.Ciofi Degli Atti M.L., Campana A., Muda A.O., Concato C., Ravà L., Ricotta L. Facing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic at a COVID-19 Regional Children's Hospital in Italy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(9):e221–e225. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camfield P., Camfield C. Incidence, prevalence and aetiology of seizures and epilepsy in children. Epileptic Disord. 2015;17(02):117–123. doi: 10.1684/epd.2015.0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray C.J., Vos T., Lozano R., Naghavi M., Flaxman A.D., Michaud C. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellez-Zenteno J.F., Patten S.B., Jette N., Williams J., Wiebe S. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: a population-based analysis. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2336–2344. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiest K.M., Birbeck G.L., Jacoby A., Jette N. Stigma in epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14:444. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begley C.E., Beghi E. The economic cost of epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsia. 2002;43(suppl 4):3–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.4.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheffer I.E., Nabbout R. SCN1A-related phenotypes: Epilepsy and beyond. Epilepsia. 2019;60(Suppl 3):S17–S24. doi: 10.1111/epi.16386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding Y., Yan H., Guo W. Clinical characteristics of children with COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:431. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French J.A., Brodie M.J., Caraballo R., Devinsky O., Ding D., Jehi L. Keeping people with epilepsy safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020;94(23):1032–1037. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aledo-Serrano Á., Mingorance A., Jiménez-Huete A., Toledano R., García-Morales I., Anciones C. Genetic epilepsies and COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from the caregiver perspective. Epilepsia. 2020;61(6):1312–1314. doi: 10.1111/epi.16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuroda N. Epilepsy and COVID-19: Associations and important considerations. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuchenbuch M., D'Onofrio G., Wirrell E., Jiang Y., Dupont S., Grinspan Z.M. An accelerated shift in the use of remote systems in epilepsy due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirrell E.C., Grinspan Z.M., Knupp K.G., Jiang Y., Hammeed B., Mytinger J.R. Care delivery for children with epilepsy during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international survey of clinicians. J Child Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0883073820940189. 883073820940189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed S.N., Mann C., Sinclair D.B., Heino A., Iskiw B., Quigley D. Feasibility of epilepsy follow-up care through telemedicine: a pilot study on the patient's perspective. Epilepsia. 2008;49(4):573–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velasquez S.E., Chaves-Carballo E., Nelson E.L. Pediatric teleneurology: A model of epilepsy care for rural populations. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;64:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson V., Bingham E. Telemedicine for epilepsy: a useful contribution. Epilepsia. 2005;46(5):614–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.05605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasmusson K.A., Hartshorn J.C. A comparison of epilepsy patients in a traditional ambulatory clinic and a telemedicine clinic. Epilepsia. 2005;46(5):767–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.44804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]