Abstract

Introduction:

Rates of opioid overdose (OD) have risen to unprecedented numbers and more than half of incarcerated individuals meet the criteria for substance use disorder, placing them at high risk. This review describes the relationship between incarceration history and OD.

Methods:

A scoping review was conducted and criteria for inclusion were: set in North America, published in English, and non-experimental study of formerly incarcerated individuals. Due to inconsistent definitions of opioid OD, we included all studies examining OD where opioids were mentioned.

Results:

The 18 included studies were all published in 2001 or later. Four associations between incarceration history and OD were identified: (1) six studies assessed incarceration history as a risk factor for OD and four found a significantly higher risk of OD among individuals with a history of incarceration compared to those without; (2) nine studies examined the rate of OD compared to the general population: eight found a significantly higher risk of fatal OD among those with a history of incarceration and three documented the highest risk of death immediately following release; (3) six studies found demographic, substance use and mental health, and incarceration-related risk factors for OD among formerly incarcerated individuals; and (4) four studies assessed the proportion of deaths due to OD and found a range from 5% to 57% among formerly incarcerated individuals.

Discussion:

Findings support the growing call for large-scale implementation of evidence-based OD prevention interventions in correctional settings and among justice-involved populations to reduce OD burden in this high-risk population.

Keywords: overdose, opioids, incarceration, jails, prisons, scoping review

1. Introduction

The United States (U.S.) has experienced an alarming rise in the rate of opioid overdose (OD) deaths. More than 52,000 people nationwide died of an OD in 2015, followed by nearly 64,000 in 2016 (Seth et al., 2018). Recent data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate this number increased again in 2017 to over 70,000 (Scholl et al., 2019). The majority of these fatal ODs, over 47,000, involved opioids, a category of substances that includes prescription opioid analgesics, heroin, and synthetic opioids like fentanyl. The age-adjusted rate of OD deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone increased by 45% between 2016 and 2017, while the number of people who reported opioid misuse fell from 11.8 to 10.3 million during this time (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2019). Increased availability of high-potency fentanyl in the drug supply has contributed to the high and growing risk of overdose among people who use opioids (Fogarty et al., 2018).

The current opioid OD epidemic has the potential to disproportionately impact people who have been incarcerated. More than 6.6 million individuals were under the supervision of U.S. adult correctional systems (i.e. jail, prison, parole, or probation) at the end of 2016 (Kaeble and Cowhig, 2018), and at least 95% of them will be released back to their communities at some point (Hughes and Wilson, 2004), as the average length of stay in jails and prisons is 25 days and 2.3 years, respectively (Kaeble, 2018; Zeng, 2020). U.S. jails also process more than 10 million admissions every year (Zeng, 2020). Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that 58% of people incarcerated in state prisons and 63% of the sentenced population in local jails meet criteria for substance use disorders (Bronson et al., 2017). Incarcerated individuals also face dramatically increased risk of death from OD, especially for opioid-involved overdose, upon their release due to the period of abstinence commonly experienced while in custody and the lack of social and financial support that many face upon reentry into the community (Wakeman et al., 2009).

Recent evidence suggests that the leading cause of death after release from incarceration is unintentional poisoning (of which, OD is a type), with the highest risk occurring early after release (Binswanger et al., 2007; Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2016; Merrall et al., 2010; Ranapurwala et al., 2018). An international meta-analysis of drug-related deaths after release identified a three-to eightfold increased risk in the first 2 weeks after release compared with subsequent two-week periods, up to the twelfth week (Merrall et al., 2010). This literature suggests a relationship between history of incarceration and OD risk. To mitigate this risk, a growing body of evidence shows that provision of OD prevention services in and following release from correctional settings, including overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND), medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and linkage to care, reduces OD risk (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2017; Malta et al., 2019). Scholars and national organizations representing both public health and criminal justice call for the scale-up of these services (National Association of Counties, 2019; National Sheriffs’ Association, 2018; Zucker et al., 2015). To appropriately target and scale-up these services a review that describes all research examining this relationship is needed to identify gaps in knowledge, future research priorities, and inform programs and policies (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). The purpose of this review is to carry out an examination of the current evidence on the relationship between history of incarceration and OD in North America.

2. Material and methods

We conducted a scoping review of the literature on the relationship between history of incarceration and OD. Unlike systematic reviews, which typically restrict inclusion to studies with narrowly defined exposure and outcome variables in order to test a specific causal relationship, scoping reviews consider a wider swath of scientific literature in order to map existing evidence on a broad topic (Munn et al., 2018). In conducting this scoping review, we followed a five-step process adapted from Levac et. al.: (1) quantify the body of literature; (2) examine how research has been conducted; (3) clarify the concepts of the research question within the evidence; (4) determine the types of evidence that exist; and (5) summarize the findings of that research (Levac et al., 2010). All the above activities were guided by our primary research question: what evidence exists of the relationship between history of incarceration and opioid OD in North America?

2.1. Search strategy

We used an iterative search strategy, beginning with basic keyword searches (e.g. “prison AND overdose AND opioid”) in the United States National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health Medical Database (PubMed) database, identifying additional keywords and citations in relevant literature identified through these initial queries. These iterative, exploratory searches were continued until all authors agreed that all keywords commonly used in the literature related to opioid use or opioid use disorder in criminal justice contexts were identified. These keywords were used to develop the following search string:

(overdose* OR over-dose*)

AND

(heroin OR opioid* OR opiate* OR morphine OR opium OR painkiller* OR pain-killer* OR methadone OR buprenorphine OR naltrexone)

AND

(prison* OR inmate* OR incarcerat* OR imprison* OR (detention ADJ2 (center* OR camp* OR facilit*)) OR offender* OR jail* OR (correction* ADJ2 (facilit* OR institution* OR system)) OR penitentiar* OR (penal ADJ2 (institution* OR facilit*)) OR parole* OR probation OR halfway house* OR recidivism OR convict* OR ex-convict*)

The final literature search for this review was run using these search terms on July 2, 2019 in the following databases: Medline, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, Criminal Justice Database, Sociological Abstracts, NTIS, and NCJRS. No restrictions were placed on date of study publication.

2.2. Study selection

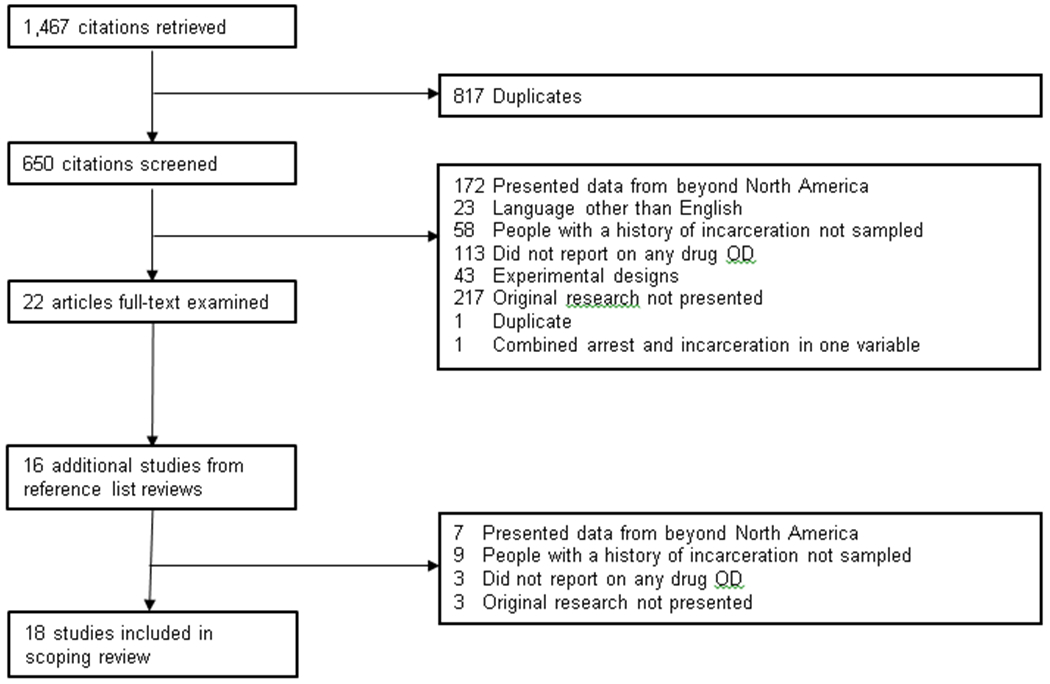

Our final search returned 1,467 studies out of which 817 were duplicates, leaving 650 for title and abstract review. Figure 1 outlines the full selection process. Studies were excluded for failing to meet any of the following criteria defined a priori: (1) set in North America (n=172); (2) published in English (n=23); and (3) observed people with a history of incarceration in either a jail or prison facility (n=58). The studies remaining after these initial exclusions varied in their operationalization of opioid use in the context of an OD event. Therefore, we decided to examine how opioids and opioid OD were referenced in the abstraction process and excluded studies that did not report on any drug OD, opioid-involved or otherwise (n=113). We made this decision in line with the parameters of a scoping review, which allows inclusion of studies with heterogenous outcomes for the purposes of exploring the literature on incarceration history and OD (Munn et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2015). This also allows us to describe studies referring to opioids and assess definitions of OD.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies for scoping review on the relationship between incarceration history and overdose (OD) in North America

Additional exclusion criteria were iteratively developed after reviewing the returned studies. Studies presenting experimental designs that otherwise met these inclusion criteria were not included in this review, because they described the implementation of a program or intervention among current or formerly incarcerated individuals, not the risk of OD as it manifests outside of that intervention (n=43). Reviews, media reports, and other studies not presenting original research were also excluded (n=217). Finally, two additional studies were removed at this stage: one newly-identified duplicate and one in which arrest and incarceration were combined into a single variable. We conducted a reference list review of the remaining 22 studies and identified 16 new sources that met our inclusion criteria. Thus, we conducted a full-text review of 38 studies. After completing the full text review, 20 of these remaining studies were also excluded based on the criteria outlined above, leaving 18 studies to be included in this scoping review.

2.3. Charting the data

The 18 articles determined to merit inclusion in this review were abstracted for the following information: author name, publication year, the type of comparison between incarceration history and overdose presented, operationalization of opioid and OD, study design, study location, recruitment/eligibility period, study population size and description, exposure/comparison of interest, primary and secondary outcomes, analytic strategy, main findings and measure of association presented, and multivariable adjustment variables. Potential threats of bias were also noted. Each study was reviewed for data extraction by two members (SM and JC) of the research team, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus among all authors.

2.4. Data synthesis

Finally, we collated, summarized, and interpreted the findings. We organized studies by the type of comparison presented and performed a thematic review to qualitatively assess the relationships between incarceration and OD presented in these studies. To produce a numerical summary of study findings, we reported on descriptive statistics and unadjusted measures of association only when adjusted measures were not presented in the article. The definition of OD presented in each study is also described to allow for interpretation of study findings. We also assessed risk of bias for each study using criteria based on those developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and outlined in the RTI Item Bank, which is appropriate for observational studies (Norris et al., 2011; Viswanathan and Berkman, 2012). Items relevant for each study design from the 13-item bank were applied to detect possible sources of bias for each study included in the review and are included in Appendix 1 (Viswanathan et al., 2013). This information was used to assist with the interpretation of study findings. Below, we report on how studies examine the relationship between history of incarceration and OD, the potential risks of bias, and the types of comparisons made in the literature; we then synthesize the findings for each comparison.

3. Results

Table 1 provides an overview of the 18 included studies, along with the risks of bias identified in each study. Since cohort designs were employed in 13 of the included studies, differential losses to follow-up introduced selection bias (Alex et al., 2017; Binswanger et al., 2013; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018a; Groot et al., 2016; Hacker et al., 2018; Kinner et al., 2012; Krinsky et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2012; Loeliger et al., 2018; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Ranapurwala et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2008; Spaulding et al., 2015). Additionally, nine studies reported unadjusted associations, introducing potential for confounding into the results (Alex et al., 2017; Binswanger et al., 2016; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018a; Hacker et al., 2018; Kinner et al., 2012; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2008; Seal et al., 2001), and four studies relied on self-reported data which can lead to information bias (i.e. social desirability and recall biases) (Barocas et al., 2015; Jenkins et al., 2011; Ochoa et al., 2005; Seal et al., 2001). Opioid OD was operationalized in various ways; only seven studies reported on opioid-involved OD (Alex et al., 2017; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018a; Hacker et al., 2018; Jenkins et al., 2011; Ochoa et al., 2005; Ranapurwala et al., 2018; Seal et al., 2001). An additional four studies measured OD that aggregated opioid OD and other drug OD into one outcome variable (Binswanger et al., 2013; Groot et al., 2016; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2008) while four other studies examined OD among individuals who use opioids (Barocas et al., 2015; Binswanger et al., 2016; Kinner et al., 2012; Loeliger et al., 2018). The three remaining studies examined OD (or drug poisoning) but only referenced opioids in the introduction or discussion of the study (Krinsky et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2012; Spaulding et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Overview of included studies in scoping review of relationship between incarceration history and overdose (OD) in North America

| Reference | Study Design | Comparison(s) Presented* | Threat(s) of Bias Detected using RTI Item Bank | How opioid OD is referenced | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Information | Confounding | ||||

| Alex, et al. 2017 | Retrospective cohort | 4 | X | X | outcome: opioid OD | |

| Barocas, et al. 2015 | Cross-sectional | 1 | X | sample: primarily people with history of heroin injection | ||

| Binswanger, et al. 2013 | Retrospective cohort | 2 & 3 | X | outcome: 58% of OD involved opioids | ||

| Binswanger, et al. 2016 | Case-Control | 3 | X | X | sample: 35% with history of heroin use | |

| Brinkley-Rubenstein, et al. 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 2 | X | X | outcome: opioid OD | |

| Groot, et al. 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 2 | X | outcome: 77% of OD involved opioids | ||

| Hacker, et al 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 1 | X | X | outcome: opioid OD | |

| Jenkins, et al. 2011 | Cross-sectional | 1 | X | outcome: opioid OD | ||

| Kinner, et al. 2012 | Prospective cohort | 1 & 3 | X | X | sample: primarily people with history of heroin injection | |

| Krinsky, et al. 2009 | Retrospective cohort | 2 & 4 | heroin referenced in introduction | |||

| Lim, et al. 2012 | Retrospective cohort | 2 & 3 | X | X | opioid OD referenced in discussion | |

| Loeliger, et al. 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 4 | X | sample: 70% IDU (majority report opioid use) | ||

| Ochoa, et al. 2005 | Cross-sectional | 1 | X | outcome: opioid OD | ||

| Pizzicato, et al. 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 2 & 3 | X | X | outcome: 83% of OD involved opioids | |

| Ranapurwala, et al. 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 2 & 3 | X | outcome: opioid OD | ||

| Rosen, et al. 2008 | Retrospective cohort | 2 & 4 | X | X | outcome: drug OD | |

| Seal, et al. 2001 | Cross-sectional | 1 | X | X | outcome: opioid OD | |

| Spaulding, et al. 2011 | Retrospective cohort | 2 | X | heroin OD referenced in discussion | ||

The risk of OD among the formerly incarcerated compared to individuals without a history of incarceration;

The risk of OD among formerly incarcerated individuals compared to the general population;

Factors associated with increased risk of OD among formerly incarcerated individuals;

Fatal OD compared to other causes of mortality among formerly incarcerated individuals.

All studies included in this review reported on at least one of the following four comparisons: (1) the risk of OD among formerly incarcerated individuals compared to individuals without a history of incarceration; (2) the rate of OD among recently incarcerated individuals compared to the general population; (3) factors associated with increased risk of OD among formerly incarcerated individuals; and (4) fatal OD compared to other causes of mortality among the recently incarcerated.

3.1. Prior incarceration as a risk factor for OD

Six studies assessed history of incarceration as a risk factor for OD; of these, four identified a statistically significant relationship between history of incarceration and non-fatal OD among people with a history of opioid use and one described the proportion of fatal opioid ODs that occurred among individuals with a history of incarceration (Table 2). That was the most recently conducted study which retrospectively examined all fatal opioid ODs (n=1,399) in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania from 2008-2014, and found that 55% occurred among individuals with a history of incarceration (Hacker et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Studies examining incarceration history as a risk factor for overdose (OD)

| Reference | Study Design | Population | Sample size (% female) | Exposure* | Outcome | Measure of Association (95% CI) | Adjustment variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hacker, et al. 2018 | Retrospective cohort | All individuals who experienced an opioid-involved overdose death in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania between 2008-2014 | 1399 (32) | At least 1 episode of incarceration in county jail | Fatal opioid-involved overdose | None, only descriptive measures 55% of OD deaths among individuals with history of incarceration | None |

| Barocas, et al. 2015 | Cross-sectional | Adult, syringe exchange program clients who primarily inject opioids in Madison and Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 2012 | 543 (31) | Incarceration of at least 30 days | Non-fatal overdose in lifetime | AOR 2.4 (1.7, 3.5) | Age, Sex, Race |

| Kinner, at al. 2012 | Prospective cohort | Street-recruited and self-referred people who primarily use heroin in Vancouver, British Columbia from 1996-2010 (age 13-58) | 2515 (34) | Arrest and incarceration of at least 1 day in the past 6 months | Non-fatal overdose in past 6 months | OR 2.13 (1.89, 2.40) | None |

| Jenkins, et al. 2011 | Cross-sectional | Syringe exchange program clients who use opioids in Seattle, Washington in 2009 | 443 (29) | Incarceration of at least 5 days in the past year | Non-fatal opioid overdose in past year | AOR 1.88 (1.04, 3.40) | Age, Sex, Uses opioid with alcohol, uses opioids with sedatives, Uses speedballs, Uses goofballs, Uses buprenorphine, Prescription opioid administration route, No permanent housing, Gender of sex partners, Syringe sharing |

| Ochoa, et al. 2005 | Cross-sectional | Street-recruited young (age 15-29), people who inject drugs in San Francisco, California between 2000-2001 | 617 (26) | Incarceration of at least 20 months | Non-fatal heroin overdose in past year | AOR 2.99 (1.52, 5.88) | Injected heroin in last 3 months, Injected cocaine in past 2 months, Injected goofball in last 3 months, Ever tested for Hepatitis, Ever witnessed an overdose |

| Seal, et al. 2001 | Cross-sectional | Street-recruited people who inject a cocaine and heroin mixture (speedball) in San Francisco, California between 1998-1999 | 1427 (31) | Incarceration of 1-2 weeks | Non-fatal heroin overdose in past year | OR 2.27 (0.81, 6.34) | None |

OR: Odds ratio; AOR: Adjusted odds ratio

Lifetime history unless otherwise indicated

The remaining five studies produced unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR and AOR) to compare the risk of non-fatal OD among those with and without a history of incarceration. These five studies were conducted among individuals reporting injection drug use, specifically. Four of the five found a statistically significant relationship between previous incarceration and history of non-fatal OD. The most recent of these five studies was a cross-sectional study carried out between June and August of 2012 among 543 people who inject drugs utilizing a syringe services program in Madison or Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Those who had experienced an OD were more likely to have a history of incarceration (AOR 2.40, 95% CI 1.70, 3.50), after adjusting for age, sex, and race (Barocas et al., 2015). The second most recent study among 2,515 street-recruited and self-referred people from 1996 to 2010 who primarily use heroin in Vancouver, British Columbia used a prospective cohort design. In bivariate analysis, those with an incarceration history of at least one day within the past six months were at increased odds of non-fatal overdose in the past six months (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.89, 2.40) (Kinner et al., 2012). In 2009, participants of a syringe services program in Seattle, Washington (n=443) were surveyed, among whom past year incarceration of five or more days was associated with past year opioid OD in a multivariate model (AOR 1.88, 95% CI 1.04, 3.40) that adjusted for demographics, substance use, and sexual behavior characteristics (Jenkins et al., 2011). An earlier cross-sectional study conducted among young people who inject drugs in San Francisco, California recruited between 2000-2001 (n=617) found that lifetime incarceration of 20 months or more was an independent predictor of lifetime heroin OD (AOR 2.99, 95% CI 1.52, 5.88) , compared to no history of incarceration in an adjusted analysis (Ochoa et al., 2005). The final and most dated study, among 1,427 street-recruited people who inject drugs in San Francisco recruited between 1998-1999, found that, compared to those without a history of incarceration, those who had ever spent 1-2 weeks incarcerated did not have a statistically significant different odds of past-year OD (OR 2.27, 95% CI 0.81, 6.34) (Seal et al., 2001).

3.2. OD risk among formerly incarcerated individuals

Nine studies included in this review compared the risk of OD in formerly incarcerated individuals to the risk of OD among the general population (i.e. those without a history of incarceration) using retrospective cohort designs (Table 3). Eight studies found a significantly higher risk of fatal OD among those with a history of incarceration and three used stratified analyses to document the highest risk of death immediately after release, followed by a reduced risk over time (Lim et al., 2012; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Ranapurwala et al., 2018). All studies examined fatal OD as an outcome of interest, although this outcome was operationalized inconsistently, as OD, drug toxicity, drug poisoning, or drug-involved death.

Table 3.

Retrospective cohort studies examining the risk of overdose (OD) among formerly incarcerated individuals

| Reference | Eligibility period | Study population | Cohort size | Comparison population | Outcome | Overall measure of association (95% CI)* | Difference by time since release | Adjustment variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brinkley-Rubenstein, et al. 2018 | 2014-2015 | Rhode Islanders who were incarcerated in the past year and died in 2014 or 2015 of drug overdose | 220 | Rhode Islanders who were not incarcerated in the past year who died in 2014 or 2015 of drug overdose | Fentanyl-involved overdose death | Not reported (p=0.584) | N/A | n/a |

| Pizzicato, et al. 2018 | 2010-2016 | People (age 15 and older) released from the Philadelphia Department of Prisons | 82,780 | General, noninstitutionalized population of Philadelphia | Overdose deaths (83.5% opioid-involved) | SMR 5.29 (4.93, 5.65) | 0-2 weeks: SMR 36.91 (29.92, 43.90) 3-4 weeks: SMR 13.86 (9.51, 18.21) ≥ 5 weeks: SMR 4.53 (4.19, 4.87) |

Age, Sex, Race |

| Ranapurwala, et al. 2018 | 2000-2015 | Adults released from a North Carolina prison | 229,274 | General population of North Carolina | Opioid overdose death | SMR 8.3 (7.8, 8.7) | 0-2 weeks: SMR 40.5 (29.7, 51.3) 0-12 months: SMR 10.6 (9.5, 11.7) |

Age, Sex, Race, Year of prison release |

| Groot, et al. 2016 | 2006-2013 | Adults released from all provincial correctional facilities in Ontario | 6,987 | General, noninstitutionalized population of Ontario | Drug-toxicity death within 1 year of incarceration (77% opioid-involved) | SMR 11.59 (6.38, 16.79) | N/A | Age, Sex |

| Binswanger, et al. 2013 | 1999-2009 | Adults released from Washington State Department of Corrections Prisons | 76,280 | General, noninstitutionalized population of Washington State | Overdose deaths (58.6% opioid-involved) | SMR 10.33 (6.61, 11.10) | N/A | Age, Sex, Race, and Median age at death by cause |

| Lim, et al. 2012 | 2001-2005 | People (age 16-89) who spent at least 1 night incarcerated in New York City Department of Corrections jail | 155,272 | General, noninstitutionalized population of New York City | Drug-involved death | SMR 2.2 (1.9, 2.5) | 1-2 weeks: 8.0 (5.2, 11.8) 3-4 weeks: 4.2 (2.1, 7.3) 5-6 weeks: 3.7 (1.8, 6.8) 7-8 weeks: 2.0 (0.6, 4.6) ≥ 9 weeks: 1.9 (1.6, 2.2) |

n/a |

| Spaulding, et al. 2011 | 1991-2006 | All individuals incarcerated in Georgia on June 30, 1991 | 23,510 | General population of Georgia | Mortality due to accidental poisoning | SMR 3.48 (2.76, 4.33) | N/A | n/a |

| Krinsky, et al. 2009 | 2001-2003 | All people released from the New Mexico Department of Corrections | 8,380 | General population of New Mexico | Accidental deaths (including drug overdose) | Not reported (p<0.0001) | N/A | n/a |

| Rosen, et al. 2008 | 1980-2005 | Black or white males (aged 20 to 69) released from a North Carolina prison | 169,795 | General, noninstitutionalized population of North Carolina | Drug overdose death | SMR for Whites 8.70 (7.98, 9.47) SMR for Blacks 2.06 (1.79, 2.36) |

N/A | n/a |

CI: Confidence interval; SMR: Standardized mortality ratio; RR: Risk ratio; n/a = not applicable

p-value reported if CI was not presented in study.

The most recently conducted study stratified all OD deaths in Rhode Island from 2014-2015 by fentanyl involvement. No significant difference in the fentanyl-involved death rate (p=0.584) was found between those with and without a history of incarceration (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018a). This was the only study that assessed a specific class of opioids related to OD, rather than opioid OD generally. The second most recent study consisted of 82,780 individuals released from the Philadelphia Department of Corrections between 2010 and 2016. These recently incarcerated individuals were observed to have a risk of OD death that was 5.29 times higher than non-incarcerated Philadelphians of the same age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Pizzicato et al., 2018). The highest risk of OD was observed closest to time since release (≤2 weeks; standardized mortality ratio [SMR] 36.91; 95% CI 29.92, 43.90). The largest of these studies, which followed a cohort of 229,274 formerly incarcerated individuals in North Carolina released between 2000 and 2015, observed an odds ratio of death from OD among this cohort of 40.5 (95% CI 29.7, 51.3) within the first two weeks after release compared to the general population of the state (Ranapurwala et al., 2018) and an overall SMR of 8.3 (95% CI 7.8, 8.7). An analysis of 6,978 drug toxicity deaths occurring in Ontario, Canada between 2006 and 2013 observed a SMR of 11.59 (95% CI 6.38, 16.79) among formerly incarcerated individuals within the first year after release from custody, compared to the general population (Groot et al., 2016).

Next, a study described a cohort of individuals released from Washington State Department of Corrections between 1999 and 2009 (n=76,280) using a retrospective cohort design and found a SMR for OD deaths of 10.33 (95% CI 6.61, 11.10) compared to the general, non-institutionalized population of Washington State (Binswanger et al., 2013). In another study, all people aged 16-89 who spent at least one night incarcerated in a New York City (NYC) jail between 2001 and 2005 (n=155,272) were followed to assess causes of death. An overall SMR of 2.2 (95% CI 1.9, 2.5) for drug-involved deaths was documented, compared to the general, noninstitutionalized population of NYC (Lim et al., 2012). The highest risk was observed within 1-2 weeks of release (SMR 8.0; 95% CI 5.2. 11.8), compared to an SMR of 1.9 (95% CI 1.6, 2.2) nine or more weeks after release. In Georgia, all individuals currently incarcerated on June 30, 1991 were enrolled into a cohort (n=23,510) and followed for up to 15 years. Those who died after release were at higher risk of mortality due to accidental poisoning (including drug overdose) compared to the general population of Georgia (SMR 3.48; 95% CI 2.76, 4.33) (Spaulding et al., 2015). Individuals released from the New Mexico Department of Corrections (n=8,380) from 2001-2003 had a higher risk of accidental death (including drug OD), compared to the general population of New Mexico (p<0.0001). Finally, the most dated study was conducted among black and white males (n=169,795) released from North Carolina prisons and represented the longest period for study (1980-2005). Stratified findings revealed a significant risk of drug overdose death among whites (SMR 8.70; 95% CI 7.98, 9.47) and blacks (SMR 2.06; 95% CI 1.79, 2.06), compared to the noninstitutionalized populations of North Carolina of the same race (Rosen et al., 2008).

3.3. Factors associated with increased risk of OD among formerly incarcerated individuals

Six studies examined risk factors for OD among formerly incarcerated individuals and found demographic, substance use and mental health, and incarceration-related characteristics that were associated with increased risk (Table 4). In terms of demographics, increased risk was observed for female sex in one study (Binswanger et al., 2013), but no significant difference by sex was observed in two others (Lim et al., 2012; Pizzicato et al., 2018). Non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity was associated with increased risk compared to Hispanic, American Indian, and other race/ethnicities, but findings were mixed in comparison to African American race (Binswanger et al., 2013, 2016; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Ranapurwala et al., 2018, Binswanger 2013). Findings related to age were also mixed. Several studies observed an association between older age and increased risk of fatal OD among formerly incarcerated individuals (Binswanger et al., 2013; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Ranapurwala et al., 2018), whereas one study found younger age to be associated with increased OD risk (Kinner et al., 2012). Having children, compared to not having children, was identified as a protective factor in the cohort of formerly incarcerated individuals from Washington state (Binswanger et al., 2016). Finally, spending at least one night in a homeless shelter, compared to spending no time in a homeless shelter, was identified as a risk factor for OD (Lim et al., 2012).

Table 4.

Summary of factors associated with overdose among formerly incarcerated individuals

| Characteristic | Risk or protective factor (reference group) | Measure of association (95% CI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Sex | Female (male) | HR 1.39 (1.09, 1.79) | Binswanger 2013 |

| HR 1.15 (0.97, 1.35)* | Pizzicato 2018 | ||

| RR 1.25 (0.67, 2.0)* | Lim 2012 | ||

| Race | Non-white (White) | AHR 0.09 (0.08, 0.10)* | Ranapurwala 2018 |

| Black, non-Hispanic (White, non-Hispanic) | HR 0.32 (0.22, 1.79) | Binswanger 2013 | |

| HR 0.17 (0.14, 0.19) | Pizzicato 2018 | ||

| AOR 0.99 (0.59, 1.66) | Binswanger 2016 | ||

| RR 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | Lim 2012 | ||

| Hispanic (White, non-Hispanic) | HR 0.30 (0.17, 0.51) | Binswanger 2013 | |

| AOR 0.40 (0.19, 0.87) | Binswanger 2016 | ||

| HR 0.41 (0.34, 0.50) | Pizzicato 2018 | ||

| RR 0.3 (0.2, 0.6) | Lim 2012 | ||

| American Indian, non-Hispanic (White, non-Hispanic) | OR 0.64 (0.20, 2.03) | Binswanger 2016 | |

| Non-Hispanic other (White, non-Hispanic) | OR 0.17 (0.04, 0.87) | Binswanger 2016 | |

| HR 0.15 (0.08, 0.28) | Pizzicato 2018 | ||

| RR 0.2 (0.0, 1.7) | Lim 2012 | ||

| Age | 25-34 (15-24) | HR 1.88 (1.47, 2.40) | Pizzicato 2018 |

| 35-44 (15-24) | HR 2.25 (1.74, 2.91) | Pizzicato 2018 | |

| 45-54 (15-24) | HR 3.22 (2.49, 4.15) | Pizzicato 2018 | |

| 55-84 (15-24) | HR 2.89 (2.09, 4.01) | Pizzicato 2018 | |

| 26-50 (18-25) | AHR 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| ≥51 (18-25) | AHR 1.0 (0.78, 1.3) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| ≥33 (less than 33) | RR 5.9 (3.0, 11.7) | Lim 2012 | |

| Per year older | AOR 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | Kinner 2012 | |

| Children | Has children (does not have children) | AOR 0.56 (0.37, 0.85) | Binswanger 2016 |

| Homelessness | Spent at least 1 night in homeless shelter (no time spent in a homeless shelter) | RR 3.4 (2.1, 5.5) | Lim 2012 |

| Substance use and mental health | |||

| Substance use | Screened positive for any substance use disorder (none) | AOR 2.33 (1.32, 3.86) | Binswanger 2016 |

| Alcohol use caused most problems prior to incarceration (no substance use) | AOR 0.42 (0.24, 0.73) | Binswanger 2013 | |

| Cocaine, other stimulants, inhalants caused most problems prior to incarceration (no substance) | AOR 0.42 (0.24, 0.73) | Binswanger 2016 | |

| Marijuana caused most problems prior to incarceration (no substance) | AOR 0.54 (0.19, 1.52) | Binswanger 2016 | |

| Opioids and sedatives caused most problems prior to incarceration (no substance) | AOR 2.81 (1.40, 5.63) | Binswanger 2016 | |

| Daily methamphetamine use (less than daily) | AOR 1.98 (1.21, 3.22) | Kinner 2012 | |

| Daily benzodiazapine use (less than daily) | AOR 1.90 (1.29, 2.80) | Kinner 2012 | |

| Injection drug use | Lifetime history (none) | AOR 2.43 (1.53, 3.86) | Binswanger 2016 |

| Daily heroin injection (less than daily) | AOR 1.29 (1.05, 1.59) | Kinner 2012 | |

| Daily cocaine injection (less than daily) | AOR 1.49 (1.22, 1.83) | Kinner 2012 | |

| Public injecting in past 6 months (none) | AOR 1.34 (1.10, 1.65) | Kinner 2012 | |

| Substance use treatment | Lifetime receipt of methadone maintenance treatment (none) | AOR 0.64 (0.48, 0.85) | Kinner 2012 |

| Mental health issues | History of panic disorder (none) | AOR 3.87 (1.62, 9.21) | Binswanger 2016 |

| Serious mental illness (none) | HR 1.54 (1.27, 1.87) | Pizzicato 2018 | |

| Incarceration-related | |||

| Mental health treatment | Receipt of psychiatric medications within 60 days of release (none) | AOR 2.44 (1.55, 3.85) | Binswanger 2016 |

| In-prison mental health treatment received (not received) | AHR 1.9 (1.7, 2.2) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| Substance use treatment | Non-pharmacological treatment during incarceration (none) | AOR 0.57 (0.36, 0.90) | Binswanger 2016 |

| Education during incarceration (none) | AHR 0.93 (0.77, 1.1) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| Non-pharmacological, short-term to intermediate treatment during incarceration (none) | AHR 1.1 (0.95, 1.3) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| Non-pharmacological, intermediate to long-term during incarceration (none) | AHR 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| Length of incarceration | 31 days to 6 months (≤30 days) | HR 1.32 (1.13, 1.54) | Pizzicato 2018 |

| Per year | HR 0.93 (0.84, 1.03) | Binswanger 2013 | |

| AOR 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | Binswanger 2016 | ||

| 4 or more days (less than 4 days) | RR 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | Lim 2012 | |

| Previous incarcerations | 1 or 2 (none) | AHR 1.1 (0.95, 1.3) | Ranapurwala 2018 |

| >2 (none) | AHR 1.6 (1.4, 1.8) | Ranapurwala 2018 | |

| 1 or more (none) | RR 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | Lim 2012 | |

| Incarceration type | Due to violations of terms of community supervision (standard) | HR 1.16 (0.85, 1.58) | Binswanger 2013 |

| Minimal custody (medium/maximum) | AOR 1.06 (0.68, 1.65) | Binswanger 2016 | |

HR: Hazard ratio; AHR: Adjusted hazard ratio; OR: Odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; RR: relative risk

Inversed so referenced group is comparable

Substance use characteristics associated with increased risk for OD included: screening positive for any substance use disorder; drug injection; polydrug use; and daily drug use, compared to less than daily drug use (Binswanger et al., 2016; Kinner et al., 2012). Lifetime receipt of methadone maintenance treatment, an evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder, was protective against OD risk (Kinner et al., 2012). Mental health characteristics associated with increased OD risk were history of panic disorder and history of serious mental illness, compared to no history of mental health concerns (Binswanger et al., 2016; Pizzicato et al., 2018).

Findings describing the relationship between OD and incarceration length and/or number of previous incarcerations were mixed (Binswanger et al., 2013; Binswanger et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2012; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Ranapurwala et al., 2018). Two studies found that receipt of mental health treatment in prison, compared to receiving no mental health treatment in prison, was associated with increased risk of fatal OD, whereas no relationship was observed between receipt of non-pharmacological substance use treatment and OD risk (Binswanger et al., 2016; Pizzicato et al., 2018).

3.4. OD as a cause of mortality among formerly incarcerated individuals

Four additional studies assessed the extent to which OD was a cause of death among formerly incarcerated individuals using cohort designs (Table 5). The proportion of deaths observed due to OD ranged from 5% to 57%. The most recent study examining time to and cause of death was among individuals living with HIV released from corrections in Connecticut between 2007 and 2014 (n=1,350) (Loeliger et al., 2018). By the end of the follow-up period, drug OD was the second leading cause of death (15% of all reported deaths) after HIV/AIDS (46%) and time to death was shorter for those who experienced fatal drug OD or accidental injury, compared to HIV/AIDS-related causes. Among individuals who died within six weeks of release from New York City jails in 2011 and 2012, opioid OD was the leading cause of death (37% of all deaths), followed by chronic disease (25%) and assaultive trauma (20%) (Alex et al., 2017). Individuals released from the New Mexico Department of Corrections between 2001 and 2003 were 5.1 (95% CI 1.01, 34.8) times more likely to die from a drug-related cause, compared to a non-drug related death (Krinsky et al., 2009). Of all deaths among formerly incarcerated individuals in this cohort, 57% were caused by drug OD. Finally, the most dated study was among white and black males who were followed for up to two years after release from a North Carolina prison between 1980 and 2005. Authors found that 5% of deaths were caused by drug OD (Rosen et al., 2008).

Table 5.

Fatal OD compared to other causes of death among formerly incarcerated individuals

| Reference | Study population | Overdose outcome (comparison, where applicable) | Time between release and death | Mortality rate/measure of association among formerly incarcerated individuals | Proportion of deaths caused by drug overdose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loeliger, et al. 2018 | Adults with HIV released from jails and prisons in Connecticut between 2007 to 2014 | Drug overdose death after first incarceration | Up to 9 years | 2,868 per 100,000 PYs (all-cause) | 15% |

| Alex, et al. 2017 | All individuals released from New York City jails in 2011 and 2012 | Opioid overdose within 6 weeks of release | Up to 6 weeks | 5.89 per 1,000 PYs (all-cause) | 37% |

| Krinsky, et al. 2009 | All individuals released from New Mexico Department of Corrections between 2001 and 2003 | Drug-involved death (nondrug-related death) | Up to 2 months | RR 5.1 (95% CI: 1.01, 34.8) | 57% |

| Rosen, et al. 2007 | Black and white males released from North Carolina prisons between 1990 and 2004 | Drug overdose death among formerly incarcerated individuals | Up to 24 years | N/A | 5% |

PY = person-years; RR = risk ratio; N/A = not applicable

4. Discussion

The evidence gathered in this scoping review suggests that incarceration is associated with increased risk for fatal and non-fatal OD in North America. Our review of 18 studies, which examined relationships between incarceration history and OD, returned evidence that: (1) former incarceration is a risk factor for OD among people who inject opioids; (2) formerly incarcerated individuals are at greater risk of OD than the general population; (3) certain demographic, substance use, and incarceration-related characteristics are associated with increased risk of OD (some of these include substance use disorder, no history of MOUDs for opioid use disorder, and mental health issues); and (4) OD is a leading cause of death among formerly incarcerated individuals.

While study designs ranged from cross-sectional surveys among urban samples of people who use opioids to retrospective cohorts covering decades and entire states, all but two studies that sought to establish a significant association between incarceration and OD did. Of note, the first of these two studies was the oldest study included in this review, enrolling participants as early as 1998 and 1999, prior to recent large increased in opioid-involved deaths; ultimately, data from this study may not be comparable with others in this review (Seal et al., 2001). This study may have also been underpowered to detect statistical significance for this relationship as only 5% of the sample reported no history of incarceration and, of that proportion, 6% reported no history of OD. The second study with null results examined fentanyl-specific OD deaths among all OD deaths and found no significant difference by incarceration history (about 40% of fatal OD in both comparison groups were fentanyl-involved), suggesting that the impacts of fentanyl-contamination in local drug supplies are severe and deadly among not only those with a history of incarceration (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018a).

Despite some compelling evidence presented in this review—such as one study that observed 40-fold increased odds of opioid OD within two weeks of release from incarceration compared to the general population (Ranapurwala et al., 2018)—the current evidence base describing the relationship between incarceration and OD risk in North America is generally limited. Few of the studies reviewed in this analysis initially set out to examine this relationship, specifically. Further, poor definitions of and/or inconsistent use of common measures greatly constrains our ability to examine this relationship across a wider literature. Many of the studies identified in our initial search assessed exposure and outcome variables related to OD, substance use, and involvement with the criminal justice system, yet did not indicate what substances were involved in the OD event, the types of substance regularly used, or whether criminal justice involvement included a period of incarceration. We originally sought to understand the relationship between recent incarceration history and opioid-involved OD (i.e. all ODs where opioids were found in the individual’s system) but felt it necessary to broaden the scope of this review to include all formerly incarcerated individuals and all OD in which opioids were mentioned given these poor definitions.

Other studies excluded from this review measured opioid-involved OD and incarceration history but did not report on the relationship between these variables. Secondary analyses of these data would expand the evidence base and set the stage for meta-analyses, which could explore this relationship with greater methodological precision. It bears mentioning, as well, that surveys providing national estimates on the burden of opioid use and associated risks exclude incarcerated populations and/or do not report individual measures of incarceration history, which further curtails the quality of available evidence (Saloner et al., 2018). We also note that many of the studies included in this review were recently published, indicating that this is an emerging area of study; seven of the 18 studies were published within the last three years. That we identified mixed findings on risk factors for OD among formerly incarcerated individuals with a history of opioid use (e.g. sex, race, age, length of incarceration) (Binswanger et al., 2013; Kinner et al., 2012; Pizzicato et al., 2018) is of particular importance for setting policy to reduce the burden of fatal OD among recently incarcerated populations. There is a real and pressing need to further explore these mixed findings through secondary analysis of existing data and intentional investigation of the relationship between opioid OD and incarceration history.

Collectively, the body of literature on this topic suggests a relationship between jail or prison time and a post-release OD. Though not conclusive, numerous criteria for the establishment of a causal relationship are proposed in these studies. Several studies in this review demonstrate a strong relationship with large measures of association (i.e. individuals with a history of incarceration have an OD mortality rate 10 times or higher than the general population) (Binswanger et al., 2013; Groot et al., 2016; Pizzicato et al., 2018; Ranapurwala et al., 2018). Consistency is suggested in that almost every study and multiple designs support the relationship. The cohort studies included demonstrate a clear temporal sequence of these two events, where incarceration consistently occurs before fatal events. Previous literature demonstrates biologic plausibility through reduced tolerance following release. Finally, analogy can be found through research demonstrating increased OD risk following in-patient opioid detoxification when MOUD is not provided upon discharge (Davoli et al., 2007; Strang et al., 2003).

Our findings support the growing call for large-scale implementation of evidence-based OD prevention interventions in correctional settings and among criminal justice-involved populations (Aronowitz and Laurent, 2016; Barglow, 2018; Bone et al., 2018; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018c; Carroll et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2019). Fortunately, the evidence for preventing fatal and non-fatal OD, specifically among persons involved in the criminal justice system, is available and well-documented. Ensuring linkage to treatment (i.e. conducting a warm hand-off to service providers rather than simply providing information and a referral) is associated with reduced risk of relapse and subsequent reduced OD risk (Gordon et al., 2014; Kinlock et al., 2007). Linkage can consist of assigning a case manager, screening and identifying accessible treatment options prior to release, providing transport and escorted visits to treatment, and following up after release. OEND programs that train incarcerated individuals to recognize and respond to OD with naloxone, an opioid antagonist that can reverse an OD with timely administration, show promising results. One OEND program review reported a 36% reduction in opioid-involved deaths within four weeks post-release (Bird et al., 2016).

Mostly importantly, the provision of MOUD to individuals with opioid use disorder during incarceration, post-release linkage to community-based care with MOUD treatment modalities, and the provision of OEND services upon release can substantially reduce OD when properly implemented (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2017; Carroll et al., 2018; Green et al., 2018). A recent evaluation of MOUD provision where methadone, buprenorphine and, naltrexone were all offered in Rhode Island correctional facilities found that this intervention reduced the rate of fatal OD among recently released individuals by more than 60% (Green et al., 2018). Recent reviews also conclude that the provision of MOUD, specifically methadone and buprenorphine, in prisons and jails provide the added benefit of increasing treatment retention post-release and these medications, along with some evidence for naltrexone, reduce substance use upon release (Hedrich et al., 2012; Moore et al., 2019).

Despite strong evidence from experimental studies that a direct relationship exists between jail- or prison-based MOUD with methadone or buprenorphine and reduced risk of opioid OD (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018b; Crowley and Van Hout, 2017; Green et al., 2018; Lincoln et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2016), few correctional facilities currently provide MOUD (Vestal, 2016). Furthermore, many facilities that do provide MOUD to incarcerated individuals either while in custody or upon release provide only one of the three FDA-approved MOUD, naltrexone, despite strong evidence that attrition is high with naltrexone and that ensuring a choice of all three medications significantly improves health outcomes (Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2018; Lott, 2018). Formerly incarcerated individuals are a large population at great risk of OD in the U.S. Effective tools and strategies to reduce the burden of opioid OD among this population have been established, but implementation of those strategies remains insufficient.

The evidence presented in this scoping review should be considered with certain limitations in mind. Due to the nature of scoping reviews as well as our use of broad search terms, our strategy erred on the side of sensitivity over specificity. While we initially intended to explore opioid-involved OD as an outcome, unspecific and inconsistent applications of this measure forced us to broaden our search. In the future, researchers should explicitly frame studies in terms of opioid-involved OD—if that is truly what is being measured. Additionally, studies could examine differences in OD by type of OD if these definitions were made clear and consistent. Next, only observational studies were included as experimental studies related to incarceration and OD only examine the effect of unique interventions on these outcomes, rather than explore the real-life association between the two. Since it is unethical to randomize study participants to incarceration, observational studies are the only way to explore the relationship between incarceration and opioid overdose. Nonetheless, reliance on observational studies introduced risk of attrition bias and confounding which may result in over- or underestimating measures of association, as detected during the assessment we conducted.

Despite these limitations, we consider our overall findings to be compelling given the largely consistent evidence toward establishing a relationship between history of incarceration and OD. Future studies could adjust comparison calculations for length of follow-up, length of incarceration, and demographic factors found in previous studies to modify the relationship between incarceration and OD. Second, all four of the cross-sectional studies comparing risk of OD among formerly and never incarcerated individuals exclusively sampled people who inject opioids. The fact that people who inject are at higher risk of OD than those who use other routes of administration (Binswanger et al., 2016; Kinner et al., 2012) should be considered in interpreting these findings. Future research examining this relationship among broader populations of people who use opioids is merited. Further, the cross-sectional studies included are subject to recall and social desirability bias, which may have resulted in an underestimation of non-fatal OD experience and opioid use.

5. Conclusion

Many studies report a relationship between history of incarceration and OD risk. To our knowledge, this is the first review examining the ways this relationship has been studied. While the field would benefit from clearer definitions of opioid OD to specifically examine this event as an outcome of incarceration, we conclude that upon release from incarceration, individuals are at heightened risk of drug OD. Interventions with a strong evidence base, such as low-barrier MOUD provision to persons with opioid use disorder in correctional settings, effective linkage-to-care programs upon release, and provision of OEND to currently and formerly incarcerated individuals, can protect against OD in this highly vulnerable population. Implementation science research can identify strategies that assure quality and uptake of these interventions, with the goal of reducing OD deaths.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Sasha Mital, National Center for Injury Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, Atlanta, GA 30341, United States.

Jessica Wolff, National Center for Injury Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, Atlanta, GA 30341, United States.

Jennifer J. Carroll, Department of Sociology & Anthropology, Elon University, 100 Campus Drive, Elon, NC 27244, United States

References

- Alex B, Weiss D, Kaba F, Rosner Z, Lee D, Lim S, Venters H, MacDonald R, 2017. Death after jail release: Matching to improve care delivery. J. Correct. Health Care 23, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L, 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz SV, Laurent J, 2016. Screaming behind a door: The experiences of individuals incarcerated without medication-assisted treatment. J. Correct. Health Care 22, 98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barglow P, 2018. Commentary: The opioid overdose epidemic: Evidence-based interventions. Am. J. Addict 27, 605–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocas JA, Baker L, Hull SJ, Stokes S, Westergaard RP, 2015. High uptake of naloxone-based overdose prevention training among previously incarcerated syringe-exchange program participants. Drug Alcohol Depend. 154, 283–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF, 2013. Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann. Intern. Med 159, 592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD, 2007. Release from prison — a high risk of death for former inmates. N. Engl. J. Med 356, 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Yamashita TE, Mueller SR, Baggett TP, Blatchford PJ, 2016. Clinical risk factors for death after release from prison in Washington state: A nested case-control study. Addiction 111, 499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C, 2016. Effectiveness of scotland’s national naloxone programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: A before (2006-10) versus after (2011-13) comparison. Addiction 111, 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone C, Eysenbach L, Bell K, Barry DT, 2018. Our ethical obligation to treat opioid use disorder in prisons: A patient and physician’s perspective. J. Law. Med. Ethics 46, 268–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Cloud DH, Davis C, Zaller N, Delany-Brumsey A, Pope L, Martino S, Bouvier B, Rich J, 2017. Addressing excess risk of overdose among recently incarcerated people in the USA: Harm reduction interventions in correctional settings. Int. J. Prison Health 13, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Macmadu A, Marshall BDL, Heise A, Ranapurwala SI, Rich JD, Green TC, 2018a. Risk of fentanyl-involved overdose among those with past year incarceration: Findings from a recent outbreak in 2014 and 2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 185, 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, McKenzie M, Macmadu A, Larney S, Zaller N, Dauria E, Rich J, 2018b. A randomized, open label trial of methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal in a combined us prison and jail: Findings at 12 months post-release. Drug Alcohol Depend. 184, 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Zaller N, Martino S, Cloud DH, McCauley E, Heise A, Seal D, 2018c. Criminal justice continuum for opioid users at risk of overdose. Addict. Behav 86, 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson J, Stroop J, Zimmer S, Berzofsky M, 2017. Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007-2009, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JJ, Green TC, Noonan RK, 2018. Evidence-based strategies for prevention opioid overdose: What’s working in the United States. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley D, Van Hout MC, 2017. Effectiveness of pharmacotherapies in increasing treatment retention and reducing opioid overdose death in individuals recently released from prison: A systematic review. Heroin Addict. Relat. Clin. Probl 19. [Google Scholar]

- Davoli M, Bargagli AM, Perucci CA, Schifano P, Belleudi V, Hickman M, Salamina G, Diecidue R, Vigna-Taglianti F, Faggiano F, Group VS, 2007. Risk of fatal overdose during and after specialist drug treatment: The vedette study, a national multi-site prospective cohort study. Addiction 102, 1954–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty MF, Papsun DM, Logan BK, 2018. Analysis of fentanyl and 18 novel fentanyl analogs and metabolites by lc-ms-ms, and report of fatalities associated with methoxyacetylfentanyl and cyclopropylfentanyl. J. Anal. Toxicol 42, 592–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE, Vocci FJ, 2014. A randomized controlled trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine: Prison outcomes and community treatment entry. Drug Alcohol Depend. 142, 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Clarke J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Marshall BDL, Alexander-Scott N, Boss R, Rich JD, 2018. Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 405–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot E, Kouyoumdjian FG, Kiefer L, Madadi P, Gross J, Prevost B, Jhirad R, Huyer D, Snowdon V, Persaud N, 2016. Drug toxicity deaths after release from incarceration in ontario, 2006-2013: Review of coroner’s cases. PLos One 11, e0157512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Jones LD, Brink L, Wilson A, Cherna M, Dalton E, Hulsey EG, 2018. Linking opioid-overdose data to human services and criminal justice data: Opportunities for intervention. Public Health Rep. 133, 658–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stöver H, Møller L, Mayet S, 2012. The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: A systematic review. Addiction 107, 501–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Wilson DJ, 2004. Reentry trends in the united states. Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins LM, Banta-Green CJ, Maynard C, Kingston S, Hanrahan M, Merrill JO, Coffin PO, 2011. Risk factors for nonfatal overdose at Seattle-area syringe exchanges. J. Urban Health 88, 118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble D, 2018. Time served in state prison, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble D, Cowhig M, 2018. Correctional populations in the united states, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, O’Grady K, Fitzgerald TT, Wilson M, 2007. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 1-month post-release. Drug Alcohol Depend. 91, 220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinner SA, Milloy M-J, Wood E, Qi J, Zhang R, Kerr T, 2012. Incidence and risk factors for non-fatal overdose among a cohort of recently incarcerated illicit drug users. Addict. Behav 37, 691–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky CS, Lathrop SL, Brown P, Nolte KB, 2009. Drugs, detention, and death: A study of the mortality of recently released prisoners. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol 30, 6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, McDonald R, Grossman E, McNeely J, Laska E, Rotrosen J, Gourevitch MN, 2015. Opioid treatment at release from jail using extended-release naltrexone: A pilot proof-of-concept randomized effectiveness trial. Addiction 110, 1008–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Nunes EV, Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, Farkas S, Fishman M, Gauthier P, Hodgkins CC, King J, Lindblad R, Liu D, Matthews AG, May J, Peavy KM, Ross S, Salazar D, Schkolnik P, Shmueli-Blumberg D, Stablein D, Subramaniam G, Rotrosen J, 2018. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (x:Bot): A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 391, 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK, 2010. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci 5, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, Luther CW, Mavinkurve MP, Binswanger IA, Kerker BD, 2012. Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City jails, 2001–2005. Am. J. Epidemiol 175, 519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln T, Johnson BD, McCarthy P, Alexander E, 2018. Extended-release naltrexone for opioid use disorder started during or following incarceration. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 85, 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeliger KB, Altice FL, Ciarleglio MM, Rich KM, Chandra DK, Gallagher C, Desai MM, Meyer JP, 2018. All-cause mortality among people with HIV released from an integrated system of jails and prisons in Connecticut, USA, 2007-14: A retrospective observational cohort study. The Lancet HIV 5, e617–e628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott DC, 2018. Extended-release naltrexone: Good but not a panacea. Lancet 391, 283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malta M, Varatharajan T, Russell C, Pang M, Bonato S, Fischer B, 2019. Opioid-related treatment, interventions, and outcomes among incarcerated persons: A systematic review. PLoS Medicine 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2016. An assessment of opioid-related deaths in Massachusetts (2013-2014). Department of Public Health, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Merrall ELC, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, 2010. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction 105, 1545–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Roberts W, Reid HH, Smith KMZ, Oberleitner LMS, McKee SA, 2019. Effectiveness of medication assisted treatment for opioid use in prison and jail settings: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 99, 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E, 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 18, 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Counties, 2019. Meeting the needs of individuals with substance use disorders: Strategies for jails, Safety + Justice Challenge. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- National Sheriffs’ Association, 2018. Jail-based medication assisted treatment: Promising practices, guidelines, and resources for the field.

- Norris SL, Atkins D, Bruening W, Fox S, Johnson E, Kane R, Morton SC, Oremus M, Ospina M, Randhawa G, Schoelles K, Shekelle P, Viswanathan M, 2011. Observational studies in systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness: AHRQ and the effective health care program. J. Clin. Epidemiol 64, 1178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa KC, Davidson PJ, Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR, 2005. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug Alcohol Depend. 80, 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB, 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc 13, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzicato LN, Drake R, Domer-Shank R, Johnson CC, Viner KM, 2018. Beyond the walls: Risk factors for overdose mortality following release from the Philadelphia Department of Prisons. Drug Alcohol Depend. 189, 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranapurwala SI, Shanahan ME, Alexandridis AA, Proescholdbell SK, Naumann RB, Edwards D, Marshall SW, 2018. Opioid overdose mortality among former North Carolina inmates: 2000–2015. Am. J. Public Health, e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA, 2008. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among men released from state prison, 1980–2005. Am. J. Public Health 98, 2278–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, McGinty EE, Beletsky L, Bluthenthal R, Beyrer C, Botticelli M, Sherman SG, 2018. A public health strategy for the opioid crisis. Public Health Rep. 133, 24S–34S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G, 2019. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Recomm. Rep 67, 1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Kral AH, Gee L, Moore LD, Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Edlin BR, 2001. Predictors and prevention of nonfatal overdose among street-recruited injection heroin users in the San Francisco Bay area, 1998-1999. Am. J. Public Health 91, 1842–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, Bacon S, 2018. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants—United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Recomm. Rep 67, 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, O’Grady KE, Kelly SM, Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG, Schwartz RP, 2016. Pharmacotherapy for opioid dependence in jails and prisons: Research review update and future directions. Subst. Abuse Rehabil 7, 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding A, Sharma A, Messina L, Zlotorzynska M, MIller L, Minswanger I, 2015. A comparison of liver disease mortality with HIV and overdose mortality among Georgia prisoners and releasees: A 2-decade cohort study of prisoners incarcerated in 1991. Am. J. Public Health 105, e51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, Beswick T, Bearn J, Rees S, Gossop M, 2003. Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: Follow up study. BMJ 326, 959–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2019. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the united states: Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Vestal C, 2016. At rikers island, a legacy of medication-assisted opioid treatment. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/05/23/at-rikers-island-a-legacy-of-medication-assisted-opioid-treatment. (Accessed January 3 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, 2012. Development of the RTI item bank on risk of bias and precision of observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol 65, 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, Hartling L, 2013. Assessing risk of bias and confounding in observational studies of interventions or exposures: Further development of the RTI item bank. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, Bowman SE, McKenzie M, Jeronimo A, Rich JD, 2009. Preventing death among the recently incarcerated: An argument for naloxone prescription before release. J. Addict. Dis 28, 124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, 2020. Jail inmates in 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistice. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker H, Annucci AJ, Stancliff S, Catania H, 2015. Overdose prevention for prisoners in New York: A novel program and collaboration. Harm. Reduct. J 12, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.