Abstract

Purpose

To explore how the COVID-19 pandemic and physical distancing measures have impacted the wellbeing and sexual health among adolescent sexual minority males (ASMM) during the initial phase of physical distancing mandates in the United States (U.S.).

Methods

From March 27, 2020 to May 8, 2020, U.S. ASMM (N = 151; ages 14–17) completed the online baseline survey of a sexual health intervention trial. COVID-19-related closed- and open-ended questions were included. A mixed-methods approach assessed COVID-19-related changes in wellbeing and sexual health by outness with an accepting guardian.

Results

The majority (57%) of participants reported being worried about COVID-19. Almost all (91%) were physical distancing. Participants noted that COVID-19 changed school, home, work, and family life. Participants highlighted that COVID-19 reduced their ability to socialize and had a deleterious effect on their mental health. In the past three months, participants reported seeing sexual partners in person less often, masturbating and viewing pornography more often, and sexting and messaging on men-seeking-men websites/phone applications about the same amount. Many described being physically distanced from sexual partners and some noted an increase in their use of virtual ways to connect with partners (e.g., video chatting). There were no differences by outness with an accepting guardian in quantitative or qualitative responses.

Conclusions

These findings provide a snapshot of the initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic among a convenience sample of U.S. ASMM and underscore the need to provide access to resources sensitive to their social, developmental, and sexual health needs during this crisis.

Keywords: adolescents, sexual minority, ASMM, YMSM, sexual health, mental health, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

By April 7, 2020 the majority of the United States (U.S.) population was living in a state with stay-at-home orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2 Emerging evidence underscores the potential toll of such distancing measures on mental, physical, and sexual health.3–6 Adolescents may be uniquely impacted by such measures compared to adult populations;4,6,7 however, very little is known about the effects of “social distancing”—referred to herein as physical distancing because of the ability to virtually connect—on adolescent sexual minority males’ (ASMM) wellbeing and sexual health.

Compared to heterosexual adolescents, ASMM in general have lower connection, more isolation, and less social status in peer networks, all of which have been associated with greater depressive symptoms among ASMM.8 Social support may be a protective factor against anxiety caused by COVID-19;9 yet sexual minority adolescents report lower levels of social support than their heterosexual peers,8,10 potentially placing them at greater risk of mental health concerns during the pandemic. Schools can play an important buffering role for sexual minority adolescents, with school connectedness, contact with a supportive adult at school, and having a gay-straight alliance at school all providing a protective effect against adverse mental health outcomes for sexual minority adolescents.11–14 Closure of schools to support physical distancing may remove these protective factors, leaving ASMM at especially heightened risk for negative health outcomes.

In addition to peers, the mental health of sexual minority adolescents is also affected by parents and families; parental and familial support may play a larger role than non-familial support.15,16 Physical distancing due to COVID-19 may lead family relationships—including those that are supportive and those that are unsupportive—to play a larger role in the mental and physical health of sexual minority adolescents than ever before. Sexual minority adolescents who are not out to their parent/guardians report more fear of harassment or rejection from their parents/guardians than adolescents who are out,17 and the mental health consequences of family rejection and a lack of support on sexual minority adolescents are well-documented.18 Family rejection and/or support may have unique implications on the wellbeing and sexual health of ASMM during times of stay-at-home orders and onward.

ASMM’s sexual behaviors can be influenced by depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns,19–21 all of which may be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although physical distancing is likely to reduce in-person contact with sexual partners, it is possible that youth may turn to more virtual (i.e., online) sexual experiences,22 such as sharing sexually explicit photos and videos, also known as “sexting.” Sexual minority adolescents are more likely to send and receive sexts, and they are also more likely to experience pressure to send sexts than their heterosexual peers.23 Sexting is associated with condomless sex, substance use, and negative mental health issues among adolescents.24,25 It is also common for ASMM to use men-seeking-men networking applications to meet partners for sex26 and it is not yet known whether or how COVID-19 related physical distancing measures are changing the ways that ASMM interact with sexual partners. Finally, most ASMM report viewing pornography, which they perceive to impact their own sexual behaviors.27 Physical distancing measures may lead adolescents to spend more time watching condomless sex via pornography, consequently impacting their current or future sexual behavior.27 Virtual sexual activity during physical distancing could therefore have long term implications on ASMM’s sexual health. As such, we explored how the COVID-19 pandemic and physical distancing measures have affected the wellbeing and sexual activities of a convenience sample of ASMM during the initial phase of physical distancing mandates in the U.S.

METHODS

Participants

Data for this analysis are from the baseline survey of a pilot randomized controlled trial testing the preliminary impact of an online sexual health intervention to promote critical examination of online media, including pornography, and decrease sexual risk-taking among ASMM. Participants (N = 154) were recruited via online advertisements and posts on social media sites from March 27, 2020 to May 8, 2020. Eligibility criteria were: (1) age 14 to 17, (2) cisgender male, (3) self-identify as gay/bisexual, report being sexually attracted to males, OR report having voluntary sexual contact with a male partner (past year), (4) have ever intentionally viewed pornography—relevant to the aims of the parent study, (5) reside in the U.S., (6) have a personal email address, and (7) be new to the study. All participants agreed to participate via an online consent procedure, including a capacity to consent assessment. To protect against fraudulent or duplicative enrollments, study advertisements did not include eligibility information and screening and baseline survey responses were cross-referenced using age (age vs. date of birth), location (zip code vs. state of residence), sexual activity (multiple questions across the screener and survey assessing sexual behavior), and email address.28,29 A $15 e-gift card was provided after completion of the survey. All procedures, including a waiver of guardian consent, were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Boston University Medical Campus.

Measures

Socio-demographics

Characteristics included recruitment source, census region of the U.S. based on self-reported state residence, age, race/ethnicity, enrollment in school, living situation, urbanicity based on participant ZIP code,30 employment, sexual orientation, and age realized sexually attracted to men.

Outness with an accepting guardian

Participants indicated whether they had told their guardian(s) that they are sexually attracted to other boys/males and, if yes, whether that guardian was accepting of their attraction to males on a four point scale of very accepting to very rejecting.31 Guardians were considered accepting if the participant reported that guardians were either very accepting or somewhat accepting. Separate questions assessing primary and secondary guardian (if they had one) were combined to form a variable indicating whether they were out with at least one accepting guardian.

Changes to wellbeing in the era of COVID-19

Participants were asked to reflect on how COVID-19 may be impacting them. Specifically, participants were asked: (1) “How worried are you about the new corona virus?” (not at all, a little, a medium amount, a lot); (2) “Are you currently ‘social distancing’ or ‘physical distancing’ (i.e., not going out of the house unless you are required to and having less in-person interactions with people outside of your family)? (yes, no); and following an open-ended question about how COVID-19 has changed their sexual life (see section below) participants were asked (3) “What other ways has the new corona virus (COVID-19) changed your life in the past three months?”

Changes to sexual behavior in the era of COVID-19

Participants were asked questions related to changes in their sexual behaviors in the past three months—a time period that encompasses the emergence of COVID-19 and related public health policies in the U.S.2 All participants were asked “In the past three months, have you seen potential sexual partners in-person less often, the same amount, or more often?” Answers were provided on a sliding scale from 0 to 100 (provided anchors were 0 = less often, 50 = the same amount, 100 = more often). Participants were then asked if they had ever (a) “sexted (traded naked pictures with another person using text messaging),” (b) “messaged with people on men-seeking-men dating websites or phone apps (e.g., Grindr, Scruff),” (c) “masturbated (touched your own genitals in a sexual way),” or (d) “received money in exchange for naked pictures, videos, or streaming videos” (check all that apply). For each checked behavior participants were asked if they had done more, less, or the same amount of that behavior in the past three months on the same sliding scale from 0 (less often) to 100 (more often). Participants were also asked whether they had “watched online pornography” more, less, or the same amount in the past three months on the same sliding scale from 0 (less often) to 100 (more often). Lastly, participants were asked to “describe some of the main ways the new corona virus (COVID-19) has changed your sexual life in the past three months, if at all” (open-ended).

Mandated reporting procedure

Multiple sensitive and, in some cases, potentially reportable behaviors were measured in this study (e.g., receiving money in exchange for naked photos/videos). We measured both whether participants ever participated in these behaviors and if there were any changes to their engagement in these behaviors in the past three months. Information about who participants engaged in these behaviors with, where they engaged in these behaviors, or when they engaged these behaviors was not collected. To protect participants’ confidentiality, we collected as few pieces of identifiable information necessary to conduct the study. As such, we did not collect participant names or addresses and only email addresses and, for some participants, telephone numbers (optional) were collected. As states differ in their definitions of child abuse and under what circumstances reporting is necessary, the laws in the states of participants who disclosed potentially reportable behaviors were reviewed. Given the definitions provided in those laws, the limited information we have about the participants, and the limited information about the circumstances under which they engaged in the reported behaviors, participants who reported such behaviors were contacted to check on their wellbeing and conduct a safety check, after which a determination was made about whether reporting was necessary.

Analyses

Since our analyses centered around outness with an accepting guardian, we excluded three participants who had missing data on outness with a guardian, leaving a final analytic sample of 151 ASMM.

Quantitative analysis

Differences by outness with an accepting guardian and socio-demographic, overall wellbeing, and sexual behavior variables were assessed using Fisher’s exact and t- tests for categorical and continuous outcomes, respectively.

Qualitative analysis

Two coders from the study team independently reviewed answers to the two open-ended questions and identified emergent concepts. The coders agreed upon a set of initial codes, which included deductive codes drawn from research questions (e.g., less access to in person sexual partners) and inductive codes representing concepts raised in participant answers (e.g., increased boredom). The codebook was revised throughout. Data from the open-ended questions were double-coded in NVivo 1232 and disagreements were resolved through discussions between the coders. Overall Cohen’s kappa was 0.81 for the final codes, indicating excellent interrater reliability.33

A framework matrix analysis was conducted to summarize, aggregate, and establish frequencies of code endorsement.34 A mixed-methods analysis was conducted to explore whether endorsement of codes differed according to whether participants were out to an accepting guardian. Following prior studies,35–37 we performed these analyses only on codes endorsed by at least five participants, and considered differences by outness with an accepting guardian in code application rates of at least 20% to be meaningful.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 1,183 potential participants clicked on the survey link, 1,144 (97%) agreed to the screener, and 422 (37%) were eligible. About half of the eligible respondents (n = 208; 49%) completed the consent process, agreed to participate, and were emailed the survey. Of these, 183 (88%) completed the baseline survey. Twenty-nine (16%) participants were excluded due to internal discrepancies suggesting ineligibility, a potential duplicate, or a programming error in the screening process. Three (0.2%) participants had missing data about outness with an accepting guardian. This left a final analytic sample of 151 ASMM. There were no differences in enrollment attrition at any step by age, race/ethnicity, or sexual orientation.

Of the 151 ASMM, 22 (15%) had missing quantitative data on at least one of the wellness and sexual behavior variables. There were no socio-demographic differences between participants with missing quantitative data versus those with complete data. Most participants (n = 134, 89%) answered at least one of the open-ended questions. Black/African American participants had the lowest rate of answering at least one open-ended question compared to White, Latino, and Mixed Race/Another Race participants (White: 91% vs. Latino: 88% vs. Black/African American: 69% vs. Mixed Race/Another Race: 100%, χ2 = 8.8, p = 0.04). There were no other significant differences in response rates.

The average age of participants was 16 years (SD = 0.9) and half (52%) were out to ≥1 accepting guardian(s) (see Table 1 for details). Participants who were out with at least one accepting guardian were more likely to live in the Midwest and be White. There were no other socio-demographic differences by outness with an accepting guardian.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics by outness with at least one accepting parent/guardian among 14-to-17-year-old sexual minority males in the United States.

| Total | Out | Not out | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 151 | n = 79 | n = 72 | ||

| Socio-demographics | n (%) | n (%) | u (%) | X2 |

| Recruitment source | 0.2 | |||

| 77 (51) | 39 (50) | 38 (53) | ||

| 57 (38) | 31 (40) | 26 (36) | ||

| From a friend | 16 (11) | 8 (10) | 8 (11) | |

| Region | 8.7* | |||

| Northeast | 26 (17) | 12 (15) | 14 (19) | |

| Midwest | 37 (25) | 27 (35) | 10 (14) | |

| South | 41 (27) | 18 (23) | 23 (32) | |

| West | 46 (31) | 21 (27) | 25 (35) | |

| Age | 3.7 | |||

| 14 | 9 (6) | 7 (9) | 2 (3) | |

| 15 | 31 (21) | 18 (23) | 13 (18) | |

| 16 | 69 (46) | 32 (41) | 37 (51) | |

| 17 | 42 (28) | 22 (28) | 20 (28) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 12.2** | |||

| White | 78 (52) | 47 (60) | 31 (43) | |

| Latino | 40 (27) | 21 (27) | 19 (26) | |

| Black/African American | 16 (11) | 8 (10) | 8 (11) | |

| Mixed Race/Another Race | 16 (11) | 2 (3) | 14 (19) | |

| Currently enrolled in school | 150 (99) | 79 (100) | 71 (99) | 1.1 |

| Live in parents’/guardians’ s home | 147 (97) | 76 (96) | 71 (99) | 0.8 |

| Metropolitan residence | 130 (87) | 69 (90) | 61 (85) | 0.8 |

| Employed ≥ part-time | 39 (26) | 22 (28) | 17 (24) | 0.4 |

| Sexual Orientation | 7.6 | |||

| Gay | 79 (53) | 47 (60) | 32 (44) | |

| Bisexual | 58 (39) | 27 (35) | 31 (43) | |

| Heterosexual | 8 (5) | 1 (1) | 7 (10) | |

| Queer/Another sexual orientation | 5 (3) | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | |

| m (SD) | m (SD) | m (SD) | t | |

| Age realized sexually attracted to males | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | 0.8 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Changes to overall wellbeing

Quantitative Data

The majority (57%) of participants reported being worried about COVID-19 a medium amount or more. Almost all participants (91%) reported engaging in physical distancing at the time of the survey. There were no differences by outness with an accepting guardian.

Qualitative Data

Most (n = 124, 82%) participants responded to the open-ended question about how COVID-19 has changed their life generally (out: n = 67, 54%; not out: n = 57, 46%). Among those who responded, participants reported that COVID-19 had changed multiple areas of their life, including school (mentioned by 40%; out: 37%, not out: 44%), home (mentioned by 22%; out: 19%, not out: 25%), work (mentioned by 17%; out: 18%, not out: 16%), and family life (mentioned by 10%; out: 12%, not out: 9%). See Table 2 for coding rates by outness with an accepting guardian.

Table 2:

Code endorsements for open-ended questions about the impact of COVID-19 on the wellbeing and sexual life of 14-to-17-year-old sexual minority males in the United States by outness with at least one accepting parent/guardian.

| Total | Out | Not out | |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Please describe some of the main ways the new corona virus (COVID-19) has changed your sexual life in the past three months, if at all:” |

N = 125 n (%) |

n = 61 n (%) |

n = 58 n (%) |

| Seeing paitner(s) less frequently than prior to COVID-19 | 48 (38) | 26 (39) | 22 (38) |

| No change in sexual activity since COVTD-19 | 47 (38) | 21 (31) | 26 (45) |

| Increased solo masturbation | 16 (13) | 9 (13) | 7 (12) |

| Increased virtual sex (sexting, exchanging nude photographs, etc.) | 12 (10) | 8 (12) | 4 (7) |

| Being stuck at home | 9 (7) | 6 (9) | 3 (5) |

| No sexual activity, unclear if this is a change due to COVID-19 | 8 (6) | 5 (7) | 3 (5) |

| Increased pornography use | 6 (5) | 3 (4) | 3 (5) |

| Being stuck inside | 6 (5) | 3 (4) | 3 (5) |

| “What other ways has the new corona virus (COVID-19) changed your life in the past three months?” |

N = 124 n (%) |

n = 61 n (%) |

n = 57 n (%) |

| Impact on school (grades, virtual classes, college, etc.) | 50 (40) | 25 (37) | 25 (44) |

| Decreased non-sexual socialization | 44 (35) | 24 (36) | 20 (35) |

| Negative mental health (depression, anxiety, stress, etc.) | 40 (32) | 23 (34) | 17 (30) |

| Being stuck at home | 27 (22) | 13 (19) | 14 (25) |

| Impact on employment (participant and parent/guardian) | 21 (17) | 12 (18) | 9 (16) |

| Strained relationship and increased time spent with family | 13 (10) | 8 (12) | 5 (9) |

| Being stuck inside | 12 (10) | 7 (10) | 5 (9) |

| Increased boredom | 10 (8) | 8 (12) | 2 (4) |

| Concern about the national and global impacts of COVID-19 | 5 (4) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) |

Many youth highlighted that COVID-19 drastically reduced their ability to socialize (mentioned by 35%; out: 36%, not out: 35%) and has had a deleterious effect on their mental health (e.g., increased stress, anxiety, depression, mentioned by 32%; out: 34%, not out: 30%). As one participant put it, “It’s made me isolate like never before and I really hate it” (17 years old, White, out). As another participant shared, “It has been very stressful, worrying about everything going on” (15 years old, Latino, not out). Another noted, “Staying in all the time is stressful” (16 years old, Black/African American, not out). Or as one simply put it, “I’ve been a lot less social and more anxious” (15 years old, White, not out).

Changes to sexual behaviors

Quantitative Data

Most participants reported sexting (n = 106, 70%) and masturbating (n = 148, 98%) in their lifetime. Over one third (n = 59, 39%) reported messaging with people on men-seeking-men websites or phone applications. Due to the small number of participants (n = 4, 3%) who reported ever receiving money in exchange for naked pictures, videos, or streaming videos we did not do further analyses specific to this behavior. Participants who were out with at least one accepting guardian were more likely to have messaged with people on men-seeking-men websites or phone applications (out: 48% vs. not out: 29%, χ2 = 5.7, p = 0.01). There were no other sexual behavior differences by outness with an accepting guardian.

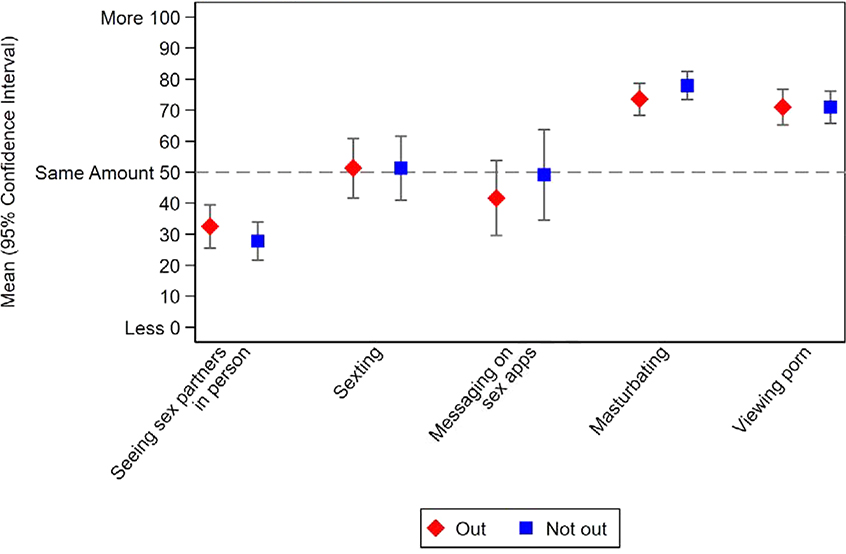

On average participants reported seeing sexual partners in person less often (M = 30.3, 95% CI = 25.7 – 34.9) in the past three months, whereas participants reported masturbating (M = 75.6, 95% CI = 72.2 – 79.1) and viewing pornography (M = 71.0, 95% CI = 67.2 – 74.9) more often. Participants reported sexting (M = 51.3, 95% CI = 44.4 – 58.3) and messaging on men-seeking-men websites and phone applications (M = 44.3, 95% CI = 35.2 – 53.4) about the same amount. As shown in Figure 1, there were no differences in the average amount of change in sexual behaviors by outness with an accepting guardian.

Figure 1.

Average changes in sexual behaviors since COVID-19 among 14–17-year-old sexual minority males in the United States by outness with an accepting parent/guardian

Qualitative Data

As shown in Table 2, among the 125 (83%) participants who answered the open-ended question about how COVID-19 has changed their sexual life (out: n = 71, 85%, not out: n = 53, 79%), many described being physically distanced from sexual partners (mentioned by 38%; out: 39%, not out: 48%). As one participant stated, “I haven’t left my house in weeks so I haven’t been able to have sex in weeks” (16 years old, White, out). Another described it this way, “I can’t go outside to see my friends, and I can’t come into contact with people I don’t know so I’m definitely not going to see anyone or have sex because of the Covid-19” (15 years old, Mixed Race/Another Race, not out).

Some also noted an increase in their use of virtual ways to connect with sexual partners (e.g., sexting, video chatting; mentioned by 10%; out: 12%, not out: 7%). As one participant said, “I can’t see my friend that I have sex with, so I can’t have sexual intercourse with him. But we have been masturbating on call together more” (14 years old, Latino, out). Or as one described, “I definitely think that the age of physical sex is over for now. A lot more guys are bored, and horny, so they tend to want to have virtual sex via Skype or Snapchat” (16 years old, Black/African American, not out). Finally, as one succinctly described it, “[my sex life] has ceased to a halt, excluding sexting (both sending pictures and dirty talk)” (17 years old, White, out).

A substantial proportion also noted that there was no change in their sexual activities, mostly because they were not having sex prior to COVID-19 (38%; out: 31%, not out: 45%). As one participated stated, “None, I am not sexually active” (16 years old, Latino, out). Another put it this way, “I never had a lotta sex to begin with so it feels like nothing has really changed” (16 years old, Black/African American, not out). Most simply stated, “It has not changed” (16 years old, Black/African American, not out).

DISCUSSION

This study examined changes in wellbeing and sexual health among a convenience sample of ASMM during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. The findings add to our knowledge on the pandemic’s impact on sexual and gender minority youth mental health and extend the literature by providing insight into early impacts of shelter-in-place and physical distancing measures on participant’s sexual behavior.

Most participants expressed worry about COVID-19, and nearly all reported engaging in physical distancing at the time of survey completion. Consistent with prior work on sexual and gender minority youth during the COVID-19 pandemic,38 physical distancing adversely impacted participants’ mental health by reducing their sense of social connectedness. Several described how the lack of in-person encounters worsened feelings of loneliness and isolation. Indeed, prior work has reported elevated symptoms of depression or anxiety among children and adolescents related to disease containment measures in prior pandemics (e.g., H1N1, SARS)39 as well as during COVID-19.40 As sexual minority youth are already vulnerable to adverse mental health outcomes related to stigma and lack of family acceptance, longer-term physical distancing measures that separate them from supportive adults, peers, and romantic partners may widen these disparities relative to their heterosexual peers.

ASMM in our sample reported reduced or no in-person sexual contact, with some explicitly stating no interest in risking exposure to COVID-19 to have in-person sexual encounters. Participants also reported increases in virtual sexual behaviors via text or videochat, and similar rates of sexual networking application use. These results largely parallel findings on the early impacts of COVID-19 on adult sexual minority men’s sexual behavior.4 Although limiting in-person sexual contact during the pandemic may have a positive public health impact resulting in lower rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among ASMM, the concurrent increase in virtual sexual behaviors can have other negative social and legal consequences. These consequences include the potential for terms of service violations on applications/sites that ban sexually explicit content, sexually explicit photos or videos being shared or viewed by others without the adolescent’s knowledge, and nonconsensual online sexual encounters between minors and adults. These findings point to the need for educators, parents, and providers who work with adolescents to acknowledge the reality that ASMM may turn to virtual spaces for sexual exploration in the absence of in-person opportunities, and address how to manage their privacy, anonymity, and safety during Internet-mediated sexual encounters. If physical distancing restrictions related to COVID-19 persist in the U.S., researchers and public health officials should monitor their long-term ramifications on adolescent sexual health and behavior.

Finally, we observed similar changes to mental health and sexual behavior regardless of whether participants were out to a supportive guardian or not. Although this was unexpected, these findings may reflect that we collected data during the first few weeks of restrictions related to the pandemic in the U.S., at a time that many were struggling to adapt to new circumstances irrespective of their situation or personal characteristics. Over time, ASMM who are not out to a supportive parent/guardian may be more likely to be negatively impacted by social isolation and increased exposure to their guardians/families. It is also possible that over time youth may start to disregard physical distancing recommendations to meet their social or sexual needs in person, especially as the pandemic persists and risk-reward assessments change.

There were several limitations to our analysis. Although we present data from a relatively diverse convenience sample from across the U.S., the findings may not generalize to all ASMM (e.g., transgender ASMM). Further, this study is not designed to compare how COVID-19 is impacting adolescents differentially by sexual identity, attraction, or behavior. It is possible that youth interested exclusively in opposite-gender/sex partners may be experiencing similar or the same impacts. Adolescents who were able to participate during this period may differ in distinct ways from those who were not (e.g., had free time or privacy to complete the survey, could prioritize study participation over other acute needs). In addition, the recall period for some participants included several weeks prior to COVID-19 shutdowns in the U.S. Thus, changes in sexual behaviors reported by these participants in the past 3 months may not exclusively reflect the impact of COVID-19 containment measures. Further, measures specific to changes in mental health outcomes were not collected. As participants spontaneously raised mental health concerns in their qualitative responses, research should measure mental health impacts moving forward. Lastly, it is possible that the dichotomous measure of outness with an accepting parent/guardian does not fully capture the complex ways that parent/guardian acceptance may impact youth.

Overall, these findings provide a snapshot of the initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in a convenience sample of U.S. ASMM and underscore the need to provide access to resources sensitive to their social, developmental, and sexual health needs during this prolonged public health crisis. Otherwise, lack of supports related to mental health, wellbeing, and sexuality may further widen the health disparities experienced by this population.

Implications and Contribution.

The COVID-19 pandemic is having potentially detrimental impacts on the wellbeing and sexual health of adolescent sexual minority males in the United States. There is a need to provide access to resources sensitive to adolescent sexual minority males’ social, developmental, and sexual health needs during this prolonged public health crisis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants. This work and the first author are supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH109346; PI: Nelson). Additional author support was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH118939; PI: John). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ASMM

adolescent sexual minority males

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mervosh S, Lee J, Gamio L, Popovich N. See which states are reopening and which are still shut down. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html Published May 13, 2020 Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 2.Raifman J, Nocka K, Jones D, et al. COVID-19 US State Policy Database. Boston University School of Public Health; 2020. Accessed May 15, 2020 www.tinyurl.com/statepolicies [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turban JL, Keuroghlian AS, Mayer KH. Sexual Health in the SARS-CoV-2 Era. Ann Intern Med. Published online May 8, 2020. doi: 10.7326/M20-2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the Impact of COVID-19 on Men Who Have Sex with Men Across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav. Published online April 29, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02894-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flentje A, Obedin-Maliver J, Lubensky ME, Dastur Z, Neilands T, Lunn MR. Depression and Anxiety Changes Among Sexual and Gender Minority People Coinciding with Onset of COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. Published online June 17, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05970-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Published online June 2020:S0890856720303373. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danese A, Smith P, Chitsabesan P, Dubicka B. Child and adolescent mental health amidst emergencies and disasters. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;216(3):159–162. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Xuan Z. Social networks and risk for depressive symptoms in a national sample of sexual minority youth. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(7):1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Button DM, O’Connell DJ, Gealt R. Sexual Minority Youth Victimization and Social Support: The Intersection of Sexuality, Gender, Race, and Victimization. J Homosex. 2012;59(1):18–43. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.614903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson MN, Asbridge M, Langille DB. School Connectedness and Protection From Symptoms of Depression in Sexual Minority Adolescents Attending School in Atlantic Canada. J Sch Health. 2018;88(3):182–189. doi: 10.1111/josh.12595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seil KS, Desai MM, Smith MV. Sexual Orientation, Adult Connectedness, Substance Use, and Mental Health Outcomes Among Adolescents: Findings From the 2009 New York City Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(10):1950–1956. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duong J, Bradshaw C. Associations Between Bullying and Engaging in Aggressive and Suicidal Behaviors Among Sexual Minority Youth: The Moderating Role of Connectedness. J Sch Health. 2014;84(10):636–645. doi: 10.1111/josh.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, Clark CM, Truong NL. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. GLSEN; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McConnell EA, Birkett MA, Mustanski B. Typologies of Social Support and Associations with Mental Health Outcomes Among LGBT Youth. LGBT Health. 2015;2(1):55–61. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicidality Among Sexual Minority Youth: Risk Factors and Protective Connectedness Factors. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7) :715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Factors Associated with Parents’ Knowledge of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youths’ Sexual Orientation. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2010;6(2):178–198. doi: 10.1080/15504281003705410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, et al. A Systematic Review of Parental Influences on the Health and Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth: Time for a New Public Health Research and Practice Agenda. J Prim Prev. 2010;31(5–6):273–309. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. A Model of Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Young Gay and Bisexual Men: Longitudinal Associations of Mental Health, Substance Abuse, Sexual Abuse, and the Coming-Out Process. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(5):444–460. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook SH, Valera P, Wilson PA, The Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. HIV status disclosure, depressive symptoms, and sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive young men who have sex with men. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):507–517. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9624-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghobadzadeh M, McMorris BJ, Sieving RE, Porta CM, Brady SS. Relationships Between Adolescent Stress, Depressive Symptoms, and Sexual Risk Behavior in Young Adulthood: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(4):394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan DJ, Card KG, Collict D, Jollimore J, Lachowsky NJ. How Might Social Distancing Impact Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Trans and Two-Spirit Men in Canada? AIDS Behav. Published online April 30, 2020:s10461–020-02891–02895. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02891-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Ouytsel J, Walrave M, Ponnet K. An Exploratory Study of Sexting Behaviors Among Heterosexual and Sexual Minority Early Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(5):621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dake JA, Price JH, Maziarz L, Ward B. Prevalence and Correlates of Sexting Behavior in Adolescents. Am J Sex Educ. 2012;7(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2012.650959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frankel AS, Bass SB, Patterson F, Dai T, Brown D. Sexting, Risk Behavior, and Mental Health in Adolescents: An Examination of 2015 Pennsylvania Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. J Sch Health. 2018;88(3):190–199. doi: 10.1111/josh.12596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macapagal K, Moskowitz DA, Li DH, et al. Hookup app use, sexual behavior, and sexual health among adolescent men who have sex with men in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(6):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson KM, Perry NS, Carey MP. Sexually explicit media use among 14–17-year-old sexual minority males in the U.S. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(8):2345–2355. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01501-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan PS, Grey JA, Simon Rosser BR. Emerging technologies for HIV prevention for MSM: what we have learned, and ways forward. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;63 Suppl 1:S102–107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182949e85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowen AM, Daniel CM, Williams ML, Baird GL. Identifying multiple submissions in Internet research: preserving data integrity. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):964–973. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9352-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.University of North Dakota Center for Rural Health. RUCA 3.10. Published August 4, 2014 Accessed July 7, 2017 https://ruralhealth.und.edu/ruca

- 31.Glick SN, Golden MR. Early male partnership patterns, social support, and sexual risk behavior among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(8):1466–1475. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0678-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo 12.; 2018. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- 33.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Medica. 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Third Edition edition. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson KM, Carey MP, Fisher CB. Is guardian permission a barrier to online sexual health research among adolescent males interested in sex with males? J Sex Res. 2019;56(4–5):593–603. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1481920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magee JC, Bigelow L, Dehaan S, Mustanski BS. Sexual health information seeking online: a mixed-methods study among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young people. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2012;39(3):276–289. doi: 10.1177/1090198111401384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mustanski B, Coventry R, Macapagal K, Arbeit MR, Fisher CB. Sexual and gender minority adolescents’ views on HIV research participation and parental permission: A mixed-methods study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(2):111–121. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fish JN, McInroy LB, Paceley MS, et al. “I’m kinda stuck at home with unsupportive oarents right now”: LGBTQ youths’ experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. J Adolesc Health. Published online June 2020:S1054139X20303116. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(1): 105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, et al. Behavioral and emotional Disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020;221:264–266.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]