Abstract

Soil physical properties and soil organic carbon (SOC) are considered as important factors of soil quality. Arable land, grassland, and forest land coexist in the saline-alkali reclamation area of the Yellow River Delta (YRD), China. Such different land uses strongly influence the services of ecosystem to induce soil degradation and carbon loss. The objective of this study is to evaluate the variation of soil texture, aggregates stability, and soil carbon affected by land uses. For each land use unit, we collected soil samples from five replicated plots from “S” shape soil profiles to the depth of 50 cm (0–5, 5–10, 10–20, 20–30, and 30–50 cm). The results showed that the grassland had the lowest overall sand content of 39.98–59.34% in the top 50 cm soil profile. The content of soil aggregates > 0.25 mm (R0.25), mean weight diameter and geometric mean diameter were significantly higher in grassland than those of the arable and forest land. R0.25, aggregate stability in arable land in the top 30 cm were higher than that of forest land, but lower in the soil profile below 20 cm, likely due to different root distribution and agricultural practices. The carbon management index (CMI) was considered as the most effective indicator of soil quality. The overall SOC content and CMI in arable land were almost the lowest among three land use types. In combination with SOC, CMI and soil physical properties, we argued that alfalfa grassland had the advantage to promote soil quality compared with arable land and forest land. This result shed light on the variations of soil properties influenced by land uses and the importance to conduct proper land use for the long-term sustainability of the saline-alkali reclamation region.

Subject terms: Agroecology, Grassland ecology, Wetlands ecology, Agroecology, Grassland ecology, Wetlands ecology, Ecology, Ecology

Introduction

Land uses strongly influence the processes and capacity of ecosystem, causing the change of ecosystem functions and services1,2. Understanding ecological consequence of land use conversion is critical for maintaining ecosystem services and conserving biodiversity3,4. Conversion of land use from natural ecosystems to agricultural ecosystems may lead to the degradation of most of the ecosystem services, which may pose a direct threat to regional and global substantial environmental developments5. One important property of ecosystems that is likely to change with land uses is soil carbon stock, which is linked to carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in the atmosphere6 and may have a significant feedback to the global carbon cycle, as the amount of carbon stored in soil is approximately twice more than that in the atmosphere7,8. Soil organic carbon (SOC) is the main component of soil carbon stock and plays a critical role in maintaining the services of ecosystems9, such as food production, water quality provision, soil fertilization, climate change abatement etc10,11. Land use changes have been largely expanded over last several decades due to the increase of population and food demand12,13, which may have caused increased CO2 emission and intensified greenhouse effect14. Hence, variations of SOC as a result of land use changes have caught much attention worldwide as a critically important issue for agricultural management, ecosystem restoration and environmental conservation5,9.

Soil physical factors are known to affect SOC. Both aggregate stability and soil particle size are among the most important soil physical properties15. Differences in human activities and vegetation types had a strong effect on the changes in soil biological properties16,17, and biomass and litter types also affected soil organic matter (SOM)18. The SOM is an effective indicator of soil resource condition that reflects functional traits such as soil aggregate stability, water holding capacity, and microbial activity19 and had close relationship with aggregate stability and soil erodibility20. Therefore, the loss of soil carbon with disturbed cultivation was often linked to the deterioration of soil physical properties. Conversely, soil aggregation structure had a great extent to affect soil biological and physic-chemical processes21, and was also closely related to SOM content. Thus, changes of soil aggregation may play an important role in SOC stock and soil quality under cultivation22. Soil bulk density (BD) and porosity are functions of SOM, soil particle size and aggregate stability, and soil particle density. Decrease of SOM would cause the increase of BD and the decrease of porosity, consequently reducing soil infiltration, and water and air storage capacities20.

Stocks of SOC generally decreased after land use conversion from grassland or forests to arable land due to the decreased carbon input and physical protection of SOM23, and the increased aboveground carbon output in arable land. Tillage can break soil aggregates through the action of soil disturbance and make SOM within aggregates exposed to microbial decomposition24. According to the conceptual models of soil aggregation, aggregates of different sizes have different strength of SOM protection25. So agricultural practices within land uses may be the important reason to alter SOC stocks26, such as reduced tillage, no-till with straw retention and conventional tillage. The SOC size-fractionation was a sensitive indictor and was used to assessing short-term SOC changes induced by land uses22,27. The coarse (2–0.05 mm) organic carbon represented the recently residues derived from litters and dead roots28. Specifically, the identification of more sensitive SOC fractions would help to detect changes in SOC pools with different land uses29. Among different SOC pools, those associated with sand fraction and particulate organic matter intimately showed early alterations in SOC resulting from land uses23,30. Also some studies reported that variation in SOM content through different land uses would lead to a large modification in soil BD, porosity, infiltration rate, aggregate stability and ultimately cycling23, and land use changes played a critical role in soil moisture31.

This study site is located at an area with a fragile wetland ecosystem under saline-alkali stress in the Yellow River Delta (YRD) of China. Frequent land use conversion occurred in this area due to anthropogenic activities and secondary salinization, which leads to serious soil degradation and threats the sustainability of the ecosystem. Charactering carbon changes and soil properties among different land uses is essential to assess the impacts of land uses on local ecosystem. Some studies have examined the impacts of different land uses on SOC or soil physicochemical properties in the YRD, but few studies have provided a comprehensive (e.g., deep in the soil profile of 0–50 cm, high density of sampling etc.) understanding of soil physical properties, soil carbon and their relationship among different land uses. Understanding these relationships in the saline-alkali reclamation region may be of particular importance for developing proper management practices for sustainable production. The objectives of this study were: (1) to assess the effect of different land uses on soil particle size and aggregate stability, (2) to determine the effect of land uses on soil carbon and (3) to provide insights into the coupling relationships between soil physical properties and soil carbon influenced by different land uses. These results are expected to help improve the understanding to conduct proper land uses and agricultural management strategies for the long-term sustainability of the saline-alkali reclamation region.

Results

Soil physical properties for different land uses

Soil water content varied significantly among different land uses (P < 0.05), and it was lower in the top layers than the deeper layers and followed the order: arable land > grassland > forest land (Table 1). Soil bulk density (BD) and soil porosity (Pt) among the land uses varied slightly, and significant differences were only detected in the layers of 10–20 cm and 20–30 cm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Soil water content (SWC), soil bulk density (BD) and total soil porosity (Pt) among different land uses (mean ± SD).

| Soil depths | Land uses | BD (g cm−3) | SWC (%) | Pt (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 cm | AL | 1.33 ± 0.11a | 13.80 ± 1.42a | 49.94 ± 4.13a |

| GL | 1.28 ± 0.04a | 8.84 ± 1.12b | 51.84 ± 1.61a | |

| FL | 1.32 ± 0.07a | 3.72 ± 1.57c | 50.12 ± 2.68a | |

| 5–10 cm | AL | 1.30 ± 0.08a | 16.34 ± 0.43a | 50.92 ± 3.11a |

| GL | 1.37 ± 0.05a | 11.12 ± 0.20b | 48.28 ± 2.11a | |

| FL | 1.34 ± 0.06a | 5.79 ± 1.52c | 49.46 ± 1.99a | |

| 10–20 cm | AL | 1.25 ± 0.10b | 18.13 ± 0.32a | 52.82 ± 3.71a |

| GL | 1.50 ± 0.02a | 13.09 ± 0.45b | 43.44 ± 0.54b | |

| FL | 1.28 ± 0.01b | 5.69 ± 0.66c | 51.77 ± 0.21a | |

| 20–30 cm | AL | 1.39 ± 0.04a | 20.56 ± 1.02a | 47.40 ± 1.32b |

| GL | 1.38 ± 0.02a | 15.15 ± 0.10b | 47.75 ± 0.72b | |

| FL | 1.29 ± 0.04b | 8.24 ± 0.42c | 51.10 ± 1.24a | |

| 30–50 cm | AL | 1.34 ± 0.06a | 22.20 ± 0.38a | 49.48 ± 2.16a |

| GL | 1.36 ± 0.07a | 18.56 ± 0.38a | 48.66 ± 2.65a | |

| FL | 1.33 ± 0.02a | 12.20 ± 4.39b | 49.90 ± 0.67a |

Different letters at the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) among different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

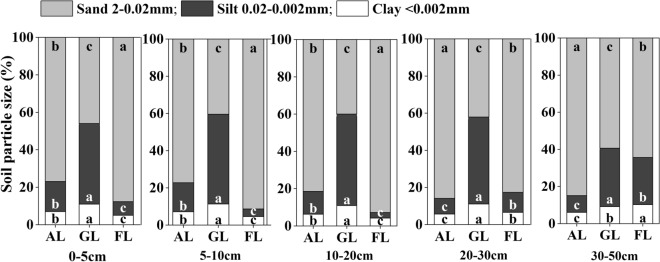

Soil particle size among different land uses varied significantly. Soil texture was mainly composed of silt and sand, and the clay only occupied for less than 12% among three land uses in the YRD, and sand was dominant soil particle in arable land and forest land, accounting for nearly 80%. Silt and clay contents were generally the highest in grassland among different land uses in each layer of the top 50 cm soil profile (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Soil particle size among different land uses at 0-50 cm depth. Different letters with the same particle size at the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) among different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

Land uses had strong effect on soil aggregates. The aggregate content at R0.25 had significant difference among different land uses (Table 2), and this aggregate content was generally the highest in grassland among different land uses in the entire top 50 cm soil profile. Stability of soil aggregates, as measured by mean weight diameter (MWD) and geometric mean diameter (GMD), followed the order of grassland > arable land > forest land (Table 3).

Table 2.

Effect of land uses on soil dry-stable aggregates (%) at different depth (mean ± SD).

| Soil depths | Land uses | > 5 mm | 5–2 mm | 2–1 mm | 0.5–1 mm | 0.5–0.25 mm | R0.25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 cm | AL | 14.01 ± 1.68a | 14.18 ± 4.36a | 6.54 ± 1.30b | 8.03 ± 1.48b | 5.64 ± 1.64b | 48.41 ± 9.27b |

| GL | 10.57 ± 0.43b | 16.06 ± 2.80a | 14.30 ± 1.76a | 24.80 ± 3.24a | 14.15 ± 2.46a | 79.89 ± 4.59a | |

| FL | 1.98 ± 1.12c | 3.03 ± 0.87b | 1.70 ± 0.56c | 2.14 ± 0.62c | 2.37 ± 0.95c | 11.22 ± 3.50c | |

| 5–10 cm | AL | 16.15 ± 2.57b | 14.86 ± 1.16b | 7.86 ± 1.50b | 8.60 ± 1.29b | 5.58 ± 0.51b | 53.04 ± 4.74b |

| GL | 23.67 ± 4.84a | 23.72 ± 1.91a | 12.60 ± 0.81a | 14.51 ± 2.14a | 8.41 ± 2.15a | 82.93 ± 3.92a | |

| FL | 4.44 ± 3.65c | 4.98 ± 3.63c | 1.55 ± 0.87c | 1.31 ± 0.69c | 1.30 ± 0.44c | 13.57 ± 9.06c | |

| 10–20 cm | AL | 23.04 ± 3.80b | 13.21 ± 2.69b | 8.12 ± 2.76b | 8.64 ± 1.84b | 5.17 ± 0.74b | 58.17 ± 7.01b |

| GL | 37.49 ± 3.75a | 25.65 ± 2.10a | 10.98 ± 0.53a | 11.78 ± 1.55a | 6.15 ± 0.66a | 92.04 ± 1.49a | |

| FL | 2.59 ± 0.57c | 3.35 ± 0.57c | 1.28 ± 0.16c | 1.35 ± 0.15c | 1.46 ± 0.53c | 10.03 ± 1.07c | |

| 20–30 cm | AL | 7.06 ± 2.79c | 19.48 ± 11.30a | 5.60 ± 1.24b | 7.09 ± 2.70b | 3.86 ± 1.29b | 43.07 ± 16.94b |

| GL | 39.45 ± 4.08a | 25.89 ± 1.39a | 9.77 ± 2.81a | 10.76 ± 1.14a | 5.38 ± 0.75a | 91.25 ± 3.77a | |

| FL | 13.68 ± 0.98b | 8.58 ± 1.43b | 4.53 ± 2.50b | 3.62 ± 1.78c | 2.37 ± 0.95c | 32.78 ± 6.21b | |

| 30–50 cm | AL | 9.97 ± 0.43c | 12.45 ± 4.83c | 6.04 ± 0.22b | 4.99 ± 2.04b | 3.00 ± 1.58a | 36.45 ± 8.49c |

| GL | 44.76 ± 4.87a | 31.28 ± 4.36a | 10.62 ± 1.52a | 9.13 ± 0.98a | 3.67 ± 0.49a | 99.47 ± 6.88a | |

| FL | 23.50 ± 3.97b | 24.63 ± 1.41b | 9.49 ± 1.35a | 7.03 ± 1.54ab | 3.81 ± 0.59a | 68.46 ± 3.85b |

Different letters with the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) between different land uses by one-way ANOVA. R0.25 is aggregates of diameter > 0.25 mm.

Table 3.

MWD, GMD values and PAD0.25 of soil dry stable aggregates for different land uses (mean ± SD).

| Parameters | Land uses | Soil depth (cm) | Average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | 5–10 | 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–50 | |||

| MWD (mm) | AL | 1.50 ± 0.24a | 1.65 ± 0.12b | 1.93 ± 0.19b | 1.33 ± 0.46b | 1.23 ± 0.18c | 1.53 ± 0.19b |

| GL | 1.59 ± 0.10a | 2.39 ± 0.27a | 3.07 ± 0.14a | 3.15 ± 0.17a | 3.58 ± 0.32a | 2.75 ± 0.04a | |

| FL | 0.48 ± 0.08b | 0.65 ± 0.30c | 0.51 ± 0.05c | 1.26 ± 0.09b | 2.33 ± 0.18b | 1.04 ± 0.11c | |

| GMD (mm) | AL | 0.71 ± 0.15b | 0.78 ± 0.07b | 0.92 ± 0.14b | 0.66 ± 0.23b | 0.56 ± 0.09c | 0.73 ± 0.12b |

| GL | 0.95 ± 0.08a | 1.46 ± 0.24a | 2.15 ± 0.16a | 2.22 ± 0.24a | 3.01 ± 0.65a | 1.96 ± 0.08a | |

| FL | 0.31 ± 0.02c | 0.35 ± 0.08c | 0.31 ± 0.01c | 0.54 ± 0.05b | 1.27 ± 0.14b | 0.55 ± 0.05c | |

| PAD0.25 | AL | 97.33 ± 0.40a | 97.69 ± 0.40c | 98.20 ± 0.55a | 98.88 ± 0.15a | 99.66 ± 0.36a | 98.35 ± 0.09a |

| GL | 95.67 ± 1.22b | 98.41 ± 0.35b | 98.25 ± 0.53a | 96.26 ± 3.02b | 98.07 ± 0.98b | 97.33 ± 0.65b | |

| FL | 97.21 ± 0.45a | 99.14 ± 0.50a | 98.15 ± 0.41a | 99.67 ± 0.04a | 98.83 ± 0.96ab | 98.60 ± 0.17a | |

Different letters with the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) among different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

MWD the mean weight diameter of dry stable aggregates, GMD the geometric mean diameter of dry stable aggregates, PAD0.25 the > 0.25 mm percentage of aggregate disruption.

Soil organic carbon fractions for different land uses

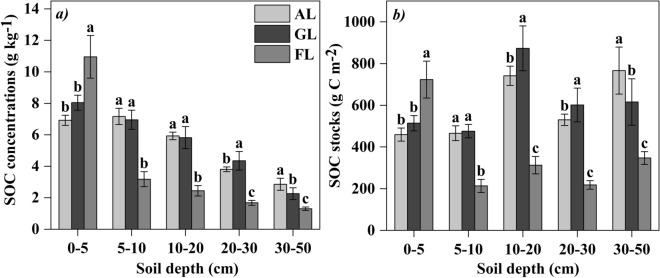

The concentration of SOC in forest land was significantly higher than arable land and grassland in the top 5 cm soil layer (Fig. 2a). The overall SOC stock showed similar patterns with SOC concentration among different land uses, except for the grassland in 10–30 cm soil profile, which was significant higher than arable land and forest land (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Soil organic carbon (SOC) concentration and (b) SOC stock (mean ± SD) with different land uses. Different letters at the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) among different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

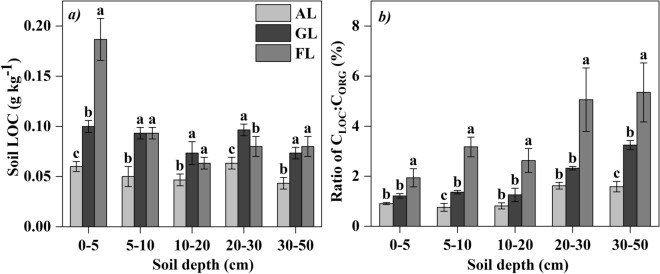

The concentration of soil labile carbon (LOC) in arable land was significant lower than both grassland and forest land in the top 50 cm soil profile (Fig. 3a). The CLOC to CORG ratio followed the order of forest land > grassland > arable land (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Soil labile carbon (LOC) concentration and (b) the CLOC to CORG ratios (mean ± SD) with different land uses. Different letters at the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) among different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

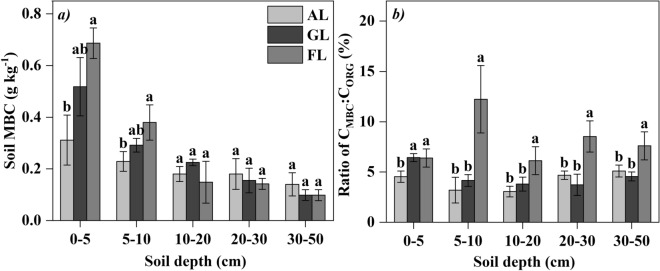

The concentration of soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) decreased with the increase of soil depth among different land uses and followed the order of forest land > grassland > arable land (Fig. 4a). The CMBC to CORG ratio was significantly higher in forest land than in arable land and grassland at soil profile below 5 cm (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) concentration and (b) the CMBC to CORG ratios (mean ± SD) with different land uses. Different letters at the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) among different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

We calculated the carbon management index (CMI) for the soil of forest land and used it as the reference soil. The relationship between NL and CPI and between L and LI had the same patterns of variation (Table 4). The CMI showed significant difference among different land uses, and changed according to the patterns of the LOC concentration. The CMI in arable land in the top 50 cm soil profile was the lowest, and decreased with the increase of soil depth. The CMI in grassland was more than 100 in the depths of 10–20 cm and 20–30 cm, suggesting that the CMI of grassland was higher than forest land (reference soil).

Table 4.

Soil carbon management index (CMI) with different land uses (mean ± SD).

| Soil depths | LAND uses | NL (g kg-1) | L | LI | CPI | CMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 cm | AL | 6.86 ± 0.24b | 0.01 ± 0.00b | 0.46 ± 0.02c | 0.70 ± 0.02c | 32.63 ± 0.97c |

| GL | 7.99 ± 0.51ab | 0.01 ± 0.00b | 0.62 ± 0.05b | 0.82 ± 0.05b | 50.96 ± 0.81b | |

| FL | 9.66 ± 1.52a | 0.02 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | |

| 5–10 cm | AL | 7.10 ± 0.29a | 0.01 ± 0.00c | 0.23 ± 0.05c | 2.37 ± 0.09a | 54.72 ± 9.50b |

| GL | 6.82 ± 0.17a | 0.01 ± 0.00b | 0.42 ± 0.02b | 2.29 ± 0.06a | 96.37 ± 6.47a | |

| FL | 2.93 ± 0.36b | 0.03 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00b | 100.00 ± 0.00a | |

| 10–20 cm | AL | 6.10 ± 0.26a | 0.01 ± 0.00b | 0.3 ± 0.05c | 2.56 ± 0.11a | 77.39 ± 8.74b |

| GL | 5.64 ± 0.35a | 0.01 ± 0.00b | 0.47 ± 0.1b | 2.37 ± 0.14a | 110.78 ± 18.21a | |

| FL | 2.34 ± 0.45b | 0.03 ± 0.01a | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00b | 100.00 ± 0.00ab | |

| 20–30 cm | AL | 3.75 ± 0.03a | 0.02 ± 0.00b | 0.31 ± 0.03c | 2.31 ± 0.02b | 71.05 ± 6.54c |

| GL | 4.15 ± 0.31a | 0.02 ± 0.00b | 0.44 ± 0.01b | 2.58 ± 0.19a | 114.35 ± 5.64a | |

| FL | 1.57 ± 0.54b | 0.05 ± 0.01a | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00c | 100.00 ± 0.00b | |

| 30–50 cm | AL | 2.83 ± 0.04a | 0.02 ± 0.00c | 0.28 ± 0.04c | 1.84 ± 0.02a | 52.08 ± 6.64c |

| GL | 2.20 ± 0.14a | 0.03 ± 0.00b | 0.59 ± 0.03b | 1.45 ± 0.09b | 86.11 ± 8.08b | |

| FL | 1.48 ± 0.53b | 0.06 ± 0.01a | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00c | 100.00 ± 0.00a |

Different letters with the same soil depth indicate significant difference (n = 5, p < 0.05) between different land uses by one-way ANOVA.

NL non-labile carbon concentration (g kg−1), L Carbon pool lability, LI lability index, CPI Carbon pool index.

Relationship between soil carbon and physical properties

Pearson’s correlation revealed that the CPI was significantly (P < 0.01) and positively correlated with the SWC, R0.25, MWD, GMD, BD and silt content (Table 5). The CMBC to CORG ratio was strongly positively correlated with sand content, but negatively correlated with the contents of clay, silt and R0.25, MWD and GMD. A similar, negative correlation was also found between MBC and R0.25, MWD and GMD. Finally, we found that SWC was negatively correlated with LOC, MBC, CMBC to CORG ratio and LI.

Table 5.

Pearson’s correlation between the characteristics of soil carbon and soil physical properties.

| Factors | SWC (%) | BD (g cm−3) | Pt (%) | Clay (%) | Silt (%) | Sand (%) | R0.25 | MWD | GMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC | − 0.193 | − 0.028 | 0.039 | 0.120 | 0.214 | − 0.203 | 0.050 | − 0.125 | − 0.136 |

| LOC | − 0.639** | − 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.093 | − 0.086 | − 0.177 | − 0.202 | − 0.078 |

| MBC | − 0.508** | − 0.243 | 0.246 | − 0.223 | − 0.147 | 0.155 | − 0.366* | − 0.450** | − 0.378* |

| LOC:SOC | − 0.260 | − 0.072 | 0.069 | − 0.007 | − 0.143 | 0.125 | − 0.124 | 0.013 | 0.040 |

| MBC:SOC | − 0.391** | − 0.207 | 0.204 | − 0.356* | − 0.360* | 0.360* | − 0.462** | − 0.413** | − 0.371* |

| NLC | − 0.186 | − 0.027 | 0.038 | 0.121 | 0.215 | − 0.203 | 0.053 | − 0.123 | − 0.136 |

| L | − 0.256 | − 0.072 | 0.070 | − 0.004 | − 0.142 | 0.124 | − 0.122 | 0.014 | 0.037 |

| LI | − 0.801** | − 0.215 | 0.216 | − 0.253 | − 0.288 | 0.283 | − 0.469** | − 0.402** | − 0.281 |

| CPI | 0.599** | 0.333* | − 0.334* | 0.266 | 0.338* | − 0.329* | 0.442** | 0.483** | 0.390** |

| CMI | − 0.408** | 0.213 | − 0.215 | 0.142 | 0.209 | − 0.203 | 0.050 | 0.208 | 0.290 |

*Correlation significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

**Correlation significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Discussion

Soil physical properties are critical to soil quality in aspects of root growth, infiltration, water and nutrient holding capacity32. Land uses and vegetation types can significantly influence soil physical properties, particularly soil aggregates distribution33,34. In this study, the variation of SWC, BD and porosity occurred among three land uses, the higher SWC observed in arable land was likely related to the fact that farmland undergone the artificial irrigation. The lower SWC in forest land than that in alfalfa grassland was probably related to the lower surface cover and the characteristic of roots in forest land, which both lead to greater transpiration35,36. This result agreed with the study of Zhang et al. (2016) that SWC at the grass stage was a significantly higher than that at the forest stage32. The high soil BD of the arable land was likely the result of combined influence of the ploughing in tillage layer, roots distribution and decreased SOC and soil aggregation, as a result of repeated events of sowing and harvesting20,37.

Soil particles and soil aggregate are the important physical properties for the process of soil physiochemical and biological properties, and soil particle size distribution is the fundamental physical factor affecting aggregate stability38. Results of our study indicated that sand is the primary soil particle among three land uses in the YRD, and the lowest sand content of 39.98–59.34% occurred in the grassland in the top 50 cm soil profile (Fig. 1). This result may be explained by different effects of soil erosion control under different land uses39. The vegetation types, coverage, and root system condition among different land uses are correlated to soil particle composition; higher root growth and litter input can improve soil physiochemical and biological properties, accelerate the formation of humus, reduce the surface wind erosion and facilitate the fixation of fine sand particles. In the grassland, high vegetation coverage and root activity can prevent soil erosion from rain splash therefore the loss of fine soil grains, because root activity of plant could greatly affect the distribution of soil particle size in newly formed wetlands in the YRD34. The soil aggregates were mainly non water-stable aggregates, and the number of water-stable aggregates was very small (Tables S1), which may be related with the special saline-alkali environment and local soil texture due to its new and fast formation of alluvial plain. To a certain extent, the situation of water-stable aggregates affects soil aeration and erosion resistance, and its small portion indicates the poor soil fertility and stability in this region. Averaged across three land uses, the contents of silt, clay and soil dry-stable aggregates (R0.25) in grassland was highest among all three land uses studies, which is in agree with a previous study by Liu et al.40. It should be noted that tillage and harvesting practices in arable land and low vegetation coverage in forest land may promote soil erosion and cause the loss of silt and clay contents and the decrease of soil aggregate stability in topsoil41,42. The alfalfa plants generally have a well-developed root system, which produces more organic matter as the roots decompose. High content of soil organic matter will produce more soil aggregates and improve the soil structure20,43.

Soil acts as either a carbon source or a carbon sink, and land uses can change the function of source and sink32,44. For the top soil (0–5 cm), our study found that SOC content and stock in forest land were the highest, which was resulted from the input of litter on the surface soil. While the arable land had less litter, frequent disturbance and strong soil respiration in the surface, which accelerated the consumption of SOC in the top soil45. But at the deeper section of the soil profile (5–50 cm), SOC content and stock in arable land and grassland were higher than that in forest land due to continuous root production and decomposition. This result was probably related to the rich root system of arable land and grassland concentrated in the deeper soil profile18,46, while lower root production and poor soil permeability in forest land, because different vegetation type can regulate the distribution of SOC through plant growth and root distribution, and the lack of oxygen soil has a fundamental restriction on microbial decomposition47. Some studies confirmed that vegetation restoration and belowground biomass had a close relationship with SOC48, and played a critical role in improving SOC stock in a degraded salt land47. Chen et al. confirmed that soil carbon accumulation was strongly driven by the establishment of vegetation49. As a salt-tolerate plant, alfalfa has high biomass and root activity, which is the main reason why artificial alfalfa grassland has high carbon content and stock compared to arable land and forest land in the saline-alkali reclamation region. Xiao et al.50 showed that conversion of natural system to other land uses decreased MBC, and the content of the LOC in TOC indicates soil quality51,52. As CMI is a good indicator of soil carbon quality53, we argued that alfalfa grassland, which has the highest CMI values, seems to provide better options for soil carbon management and soil quality.

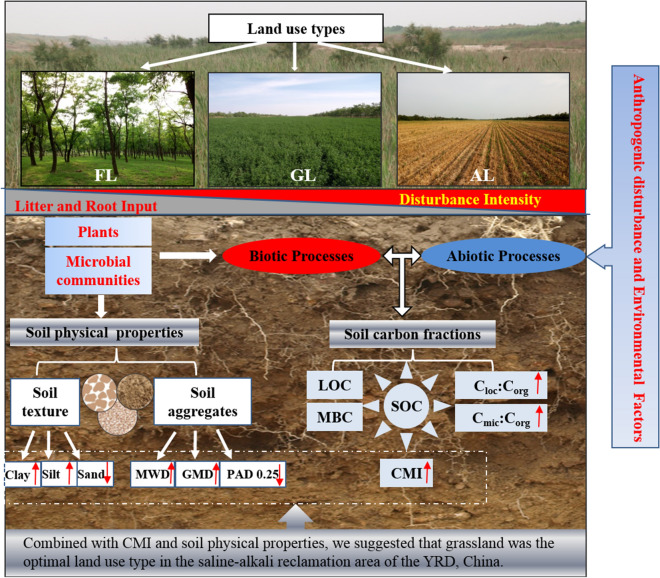

Soil organic carbon, particularly active component of organic carbon, has been reported to act as important binding agents for soil aggregates and their stability54,55, and this assertation was demonstrated by the strong correlation between CPI and soil physical properties in our study. Moreover, we found that CPI were particularly sensitive to soil water content (SWC) and aggregate stability. According to Zhao et al., higher SWC could reduce the impact of soil salinity on soil carbon stock due to the variations of salt concentrations and O2 diffusion of soil layers, because high salinity could influence solubility of SOM, inhibit microbial processes and the final soil carbon stock47, which could explain higher carbon content and stock in arable land and grassland than those in forest land in the deeper soil profile. Increased SOC could improve aggregate stability indirectly through increasing energy and nutrient availability for soil microbes53. Moreover, some studies found that the aggregate stability was related to SOM composition and had good correlations between carbohydrate content and soil aggregate stability40. Specifically, the occurrence of SOC and aggregate stability in arable land and grassland were higher than that in forestland in this region studies, but lower active component of organic carbon in arable land which resulted in lower carbon management. In brief, land use types had changed the vegetation types with different disturbance intensities, litter and roots inputs. The soil physical properties changed through biotic process regulated by plants and soil microbial communities; the inputs and accumulation of organic matter resulted from complex interactions between biotic processes and abiotic processes driven by anthropogenic disturbance and environmental factors (Fig. 5). Under different vegetation types, the soil texture and soil aggregate stability was improved; SOC and active carbon increased, followed by the increase of CMI in grassland. Therefore, combining soil physical properties and soil carbon index with land uses in comprehensive consideration, we believed that alfalfa grassland is the best land use type to improve soil physical properties and the quality of soil carbon in the YRD, which experienced frequent secondary salinization in the past decades. As a result, the proper land use, or the conversion of forest and grassland into arable land should be of concern in the context of soil quality and environmental degradation. In view of the arable land, to conduct proper agricultural practices, such as less impact of land tillage practices, may be a better option to improve soil quality for the long-term production and sustainability of the saline-alkali reclamation region.

Figure 5.

Relationship between soil physical properties and soil organic carbon with different land uses. The photographs in Fig. 5 were taken from three land uses (FL, GL, AL) in the study area by the author ‘Shuying Jiao’.

Conclusions

Soil physical properties play an important role in the formation and transformation of soil carbon during the process of land use and land cover change. The study showed strong changes in soil physical properties and soil carbon among the arable land, grassland and forest land and these changes were not uniform along the soil profile to the depth of 50 cm. Overall, we found that alfalfa grassland had effectively improved soil physical properties and soil carbon, and the soil layer of 20–30 cm may be the turning point for soil physical properties change between the arable land and forest land. Land management practices, such as plowing and harvesting, had strong impact on the SOC, suggested by higher SOC in the arable land compared to forest land except 0–5 cm soil layer. Additionally, CMI of arable land was the lowest relative to grassland and forest land. Therefore, the long-term conventional cultivation of arable land is not favorable to soil carbon management and soil quality improvement, and more attention should be paid to improve the soil quality and ecosystem sustainability in the saline-alkali reclamation region.

Materials and methods

Study site

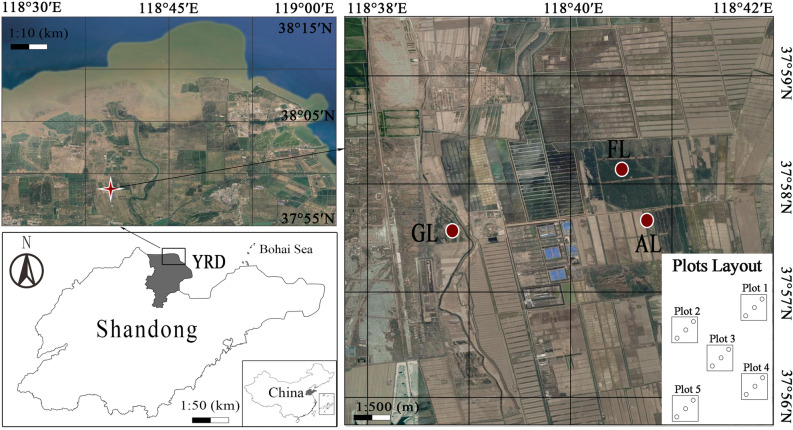

The study sites are located in the Hekou district of Dongying city, in the Yellow River Delta (YRD), Shandong Province, China (37°54′10.19″ N, 118°31′13.83″ E Fig. 6). It is a typical alluvial plain of the Yellow River and belongs to the semi-humid monsoon climate zone with warm temperate. Mean annual precipitation is about 692 mm occurring mainly during June, July and August, and mean annual temperature is 13.2 °C with seasonal variation. The soils are mainly of Calcaric Fluvisols (moisture soil) and Gleyic Solonchaks (coastal saline moisture soil) according to FAO56. The mixed forest is dominated by a Robinia pseudoacacia L. and an adjacent crop land situated side by side for the study. The cultivation vegetation after reclamation consists of wheat–maize and purple alfalfa predominantly, the arable land and artificial grassland sometimes were converted to each other due to the serious secondary salinization.

Figure 6.

The location of the study area in the Yellow River Delta of Shandong Province and the layout of the study plots (not to scale); this map was created using the software of Photoshop CS6 and Bigemap 14.1 https://www.bigemap.com/.

Experimental design

Three typical land use units (annual arable land, artificial grassland and artificial forestland) were selected according to the main land use types in the study area, and were investigated in detail for the history and current situation of land cultivation. The annual arable land was ploughed, fertilized, irrigated and planted with crop every year since reclamation of the 1950s, and rotationally planted with winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and summer maize (Zea may L.) under conventional tillage for more than ten years. Winter wheat was sown in early October and harvested in early June next year, and summer maize was sown in mid-June and harvested in late September. The artificial grassland was transformed from the previous arable land in 2011, and then continuously planted with purple alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) for five years. The alfalfa was harvested for four times each year as a source of livestock fodder. For the alfalfa field, base fertilizer was applied at sowing and no other fertilizer was applied during five-year of growth. The forestland is the result of artificial afforestation occurred in the 1960s on the saline-alkali land dominated with Robinia pseudoacacia L. without reclamation. The three types of land use have similar physiographic conditions and slope gradients, which belongs to the same region and has the same parent materials. The crop and plantation of the study sites are as follows: (1) annual arable land (AL): wheat–maize rotation plantation; (2) artificial grassland (GL): alfalfa pasture; (3) Forest land (FL): Robinia pseudoacacia L. forest.

Field work

A field survey was conducted in late September in 2016 (after the summer maize was harvested). In this study, we determined the sampling areas according to the size of the communities30, selecting five 2 m × 2 m plots from representative terrain in the herbaceous communities of the arable land and artificial grassland, five 5 m × 5 m plots in the forest land. The sampling plots were distributed according to a “S” shape in each land use unit, and 100 m apart between sampling plots. At each sampling plot, three soil sampling sites were located at the two diagonal corners and the center of the plot. Soils at each sampling site were collected from soil profiles to 50 cm depth (0–5, 5–10, 10–20, 20–30, and 30–50 cm) by using a drill. A composite soil sample at certain soil depth was obtained by mixed all these samples at each plot. The composite soil samples for soil water content (SWC) were stored in sealed aluminum cases to prevent potential moisture loss. Soil samples for SOC fractionation, particle sizes were stored in zip-top plastic bags. The undisturbed soil samples for aggregate analysis were wrapped up with paper to avoid destroying the aggregates. Soil bulk density (BD) was measured at the intermediate position of each soil layer using a cutting ring with inner diameter of 5.0 cm, and volume of 100 cm3. Overall, 75 composite soil samples were collected, representing three land uses, five depths and five replicates. The fresh soil samples were immediately taken back to the lab for the analysis preparation.

Laboratory analysis

In the laboratory, the moist soil samples were crushed to pass through 2 mm sieve, and removed the roots and other debris by tweezers. The sieved soil samples were divided into two sub-samples for air-dried and stored at low temperature, respectively. A part of air-dried samples was sieved through 0.18 mm screen to measure the soil SOC and labile organic carbon (LOC). The moist samples about 200 g each sample were immediately stored at 4 °C to measure the soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC). SWC was determined by oven-dried at 105 °C to constant weight (approximately 24 h). BD was calculated as the ratio of dry soil weight by oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h of the soil (volume: 100 cm3). Total soil porosity (Pt), Eq. (1) was obtained from measured BD and soil particle density (2.65 g cm−3)57, the calculation equation according to the following:

| 1 |

where Pt is the total soil porosity, ρb refers to the soil bulk density, and ρp refers to the soil density (2.65 g cm−3).

The pipette method was used to measure the soil particle size with Na hexametaphosphate after soil organic matter oxidation with H2O2 by a Laser Grain-size Analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Instruments Inc., Worcestershire, UK) with international classification58, then calculated the proportions of the clay (< 0.002 mm), silt (0.002–0.02 mm), and sand (> 0.02 mm) contents.

The soil aggregates were measured by the dry-sieving method and wet-sieving method using soil aggregate analyzer (TTF-100, Shunlong experimental instrument factory, Shangyu city, China). A set of five stacking sieves with openings of 5, 2, 1, 0.5 and 0.25 mm were selected to determine the dry-stable aggregates and wet-stable aggregates with air-dried soil samples of 100 g and 50 g with three replicates respectively. The aggregates were divided into aggregates sized > 5 mm, 2–5 mm, 1–2 mm, 0.5–1 mm, 0.25–0.5 mm. The contents of > 0.25 mm mechanically stable aggregates (R0.25) were calculated using Eq. (2), for which the > 0.25 mm fraction was the most susceptible to changes in land use or management40,59, and soil aggregate fractions obtained by the dry-sieving method have been successfully used to analyze SOC pool60. The soil structural stability was characterized using the mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD) of soil aggregates according to Eqs. (3) and (4)61,62. The > 0.25 mm percentage of aggregate disruption (PAD0.25) was calculated using Eq. (5).

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where R0.25 is the content of soil aggregates > 0.25 mm, Mr>0.25 is weight of aggregate > 0.25 mm, MT is the total weight of soil tested. Xi is the mean diameter of each size classes (< 0.25 mm, 0.25–0.5 mm, 0.5–1 mm, 1–2 mm, 2–5 mm and > 5 mm), and Wi is the weight fraction of aggregates in size class i, and n is the number of size fractions. D0.25 is the > 0.25 mm dry-sieved aggregate content, and W0.25 is the > 0.25-mm water-stable aggregate content.

The total SOC concentrations were determined following the dry combustion method63 using a CHN analyzer. The MBC was measured by chloroform-fumigation extraction method51,64. LOC was determined by using 333 mmol L−1 KMnO4 Oxidation Method, and measured by the spectrophotometric of 565 nm wave length65. The total SOC was considered as equal to the total soil carbon because the measured inorganic carbon (carbonates) contents of the samples were almost nil66. Carbon Management Index (CMI) was calculated using the procedure outlined below 65,66, using the no-reclamation forest soil as reference sample:

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was carried out using the SPSS software, ver. 16.0 (IBM, USA) to analyze the differences of soil physical properties and soil carbon among different land use types. Means of the main effect were compared using Duncan multiple-range procedure test at P ≤ 0.05 for significance. Pearson correlation coefficients were used for the correlation analysis between soil physical properties and soil carbon. All the figures were produced using Origin 10.0 (Originlab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31302014), the National Key Research and Development Project of China (Nos. 2017YFD0800602; 2018YFD0800403), Forestry Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shandong Province (No. 2019LY005), and Major Science and Technology Innovation Projects in Shandong Province (2019JZZY010723).

Author contributions

Y.Q.L. and S.Y.J. conceived the research, carried out the field investigations, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.R.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Y.W.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. Z.Y.X., B.S.K. and Y.L. coordinated and conducted field investigations and laboratory analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-77303-8.

References

- 1.Lawler JJ, et al. Projected land-use change impacts on ecosystem services in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:7492–7497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405557111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X, Wang S, Fu B, Liu Y, Zhu Y. Land use optimization based on ecosystem service assessment: A case study in the Yanhe watershed. Land Use Policy. 2018;72:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma T, et al. Four decades' dynamics of coastal blue carbon storage driven by land use/land cover transformation under natural and anthropogenic processes in the yellow river delta, china. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;655:741–750. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teixeira Z, Teixeira H, Marques JC. Systematic processes of land use/land cover change to identify relevant driving forces: implications on water quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;470:1320–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu B, et al. Ecosystem services in changing land use. J. Soils Sediments. 2015;15:833–843. doi: 10.1007/s11368-015-1082-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith P. Land use change and soil organic carbon dynamics. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 2008;81:169–178. doi: 10.1007/s10705-007-9138-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Post WM, Kwon KC. Soil carbon sequestration and land-use change: Processes and potential. Glob. Change Biol. 2000;6:317–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00308.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo L, Gifford RM. Soil carbon stocks and land use change: A meta analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2002;8(4):345–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1354-1013.2002.00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ou Y, Rousseaub AN, Wang L, Yan B. Spatio-temporal patterns of soil organic carbon and pH in relation to environmental factors: A case study of the black soil region of northeastern China. Agric. Ecosyst. and Environ. 2017;245:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2017.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson M. Ecosystems services. Encycl. Environ Health. 2011;35(15):225–233. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52272-6.00416-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng YH, et al. Contrasting responses of salinity-stressed salt-tolerant and intolerant winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars to ozone pollution. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012;52:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, et al. Photosynthetic characteristics and uptake and translocation of nitrogen in peanut in a wheat-peanut rotation system under different fertilizer management regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:86. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, et al. Response of summer maize photosynthate accumulation and distribution to shading stress assessed by using 13CO2 stable isotope tracer in the field. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1821. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizanur Rahman M, Nabiul Islam Khan M, Fazlul Hoque AK, Ahmed I. Carbon stock in the Sundarbans mangrove forest: Spatial variations in vegetation types and salinity zones. Wetlands Ecol. Manag. 2015;23:269–283. doi: 10.1007/s11273-014-9379-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domínguez J, Negrín MA, Rodrguez CM. Aggregate water-stability, particle-size and soil solution properties in conducive and suppressive soils to Fusarium wilt of banana from Canary Islands (Spain) Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001;33:449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00184-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan K, et al. Physiological adaptive mechanisms of plants grown in saline soil and implications for sustainable saline agriculture in coastal zone. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013;35(10):2867–2878. doi: 10.1007/s11738-013-1325-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen P, Yan K, Shao HB, Zhao SJ. Physiological mechanisms for high salt tolerance in wild soybean (Glycine soja) from Yellow River Delta, China: Photosynthesis, osmotic regulation, ion flux and antioxidant capacity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:12. doi: 10.1371/annotation/dd945f7c-c50b-461d-ab38-15e8b0966458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi Y, et al. Response of soil physical, chemical and microbial biomass properties to land use changes in fixed desertified land. CATENA. 2018;160:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2017.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeh L, Buddenbaum H, Steffens M. Imaging Vis-NIR spectroscopy-mapping SOM quality and quantity in undisturbed soil profiles of semiarid steppe in Inner Mongolia. EGU General Assem. 2014. 2015;16:13506. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li XG, Li FM, Zed R, Zhan ZY, Bhupinderpal S. Soil physical properties and their relations to organic carbon pools as affected by land use in an alpine pastureland. Geoderma. 2007;139:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2007.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peixoto RS, et al. Soil aggregation and bacterial community structure as affected by tillage and cover cropping in the Brazilian cerrados. Soil Till. Res. 2006;90:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2005.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, et al. Changes in soil organic carbon, nutrients and aggregation after conversion of native desert soil into irrigated arable land. Soil Till. Res. 2009;104:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2009.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beheshti A, Raiesi F, Golchin A. Soil properties, C fractions and their dynamics in land use conversion from native forests to croplands in northern Iran. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012;148(2):121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2011.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Ti J, Chen F. Soil aggregates response to tillage and residue management in a double paddy rice soil of the Southern China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2017;109:103–114. doi: 10.1007/s10705-017-9864-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei Y, Wu X, Xia J, Shen X, Cai C. Variation of soil aggregation along the weathering gradient: Comparison of grain size distribution under different disruptive forces. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0160960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang XM, Drury CF, Reynolds WD, Tan CS. Impacts of long-term and recently imposed tillage practices on the vertical distribution of soil organic carbon. Soil Till. Res. 2008;100:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2008.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dou X, He P, Zhu P, Zhou W. Soil organic carbon dynamics under long-term fertilization in a black soil of china: Evidence from stable C isotopes. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21488. doi: 10.1038/srep21488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conant RT, Six J, Paustian K. Land use effects on soil carbon fractions in the southeastern United States. I. Management-intensive versus extensive grazing. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2003;38:386–392. doi: 10.1007/s00374-003-0652-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balesdent J, Chenu C, Balabane M. Relationship of soil organic matter dynamics to physical protection and tillage. Soil Till. Res. 2000;53:215–230. doi: 10.1016/S0167-1987(99)00107-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen BT. Physical fractionation of soil and structural and functional complexity in organic matter turnover. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2001;52:345–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2001.00417.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hupet F, Vanclooster M. Intraseasonal dynamics of soil moisture variability within a small agricultural maize cropped field. J. Hydrol. 2002;261:86–101. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(02)00016-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YW, Shangguan ZP. The coupling interaction of soil water and organic carbon storage in the long vegetation restoration on the Loess Plateau. Ecol. Eng. 2016;91:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.03.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, et al. Spatio-temporal variation of rhizosphere soil microbial abundance and enzyme activities under different vegetation types in the coastal zone, Shandong China. Plant Biosyst. 2014;148(3):403–409. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2013.770804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu JB, et al. Fractal features of soil particle size distribution in newly formed wetlands in the Yellow River Delta. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:10540. doi: 10.1038/srep10540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YQ, Shao MA, Shao HB. A preliminary investigation of the dynamic characteristics of dried soil layers on the Loess Plateau of China. J. Hydrol. 2010;381:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.09.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang YQ, Zhang XC, Cong W, Wei QC. Spatial variability of soil moisture on slope-land under different land uses on the Loess Plateau. Trans. CSAE. 2006;22(12):65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen HY, et al. Root order-dependent seasonal dynamics in the carbon and nitrogen chemistry of poplar fine roots. New For. 2017;48(5):587–607. doi: 10.1007/s11056-017-9587-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Six J, Paustian K. Aggregate-associated soil organic matter as an ecosystem property and a measurement tool. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014;68:A4–A9. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao P, Niu X, Lv S, Zhang G. Fractal characterization of soil particle-size distribution under different land-use patterns in the Yellow River Delta Wetland in China. J. Soils Sediments. 2014;14:1116–1122. doi: 10.1007/s11368-014-0876-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu MY, Chang QR, Qi YB, Liu J, Chen T. Aggregation and soil organic carbon fractions under different land uses on the tableland of the loess plateau of China. CATENA. 2014;115:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2013.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, Fu B, Zhao W, Hu H, Wang Y. Multifractal characteristics of soil particle size distribution under different land-use types on the loess plateau, china. CATENA. 2008;72(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2007.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia XY, et al. Effects of tillage managements and maize straw returning on soil microbiome using 16S rDNA sequencing. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019;61(6):765–777. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dameni H, Wang J, Qin L. Soil aggregate and organic carbon stability under different land uses in the north china plain. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2010;41(9):1144–1157. doi: 10.1080/00103621003711297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng L, Wang KB, Chen ML, Shangguan ZP, Sweeney S. Soil organic carbon storage capacity positively related to forest succession on the Loess Plateau China. CATENA. 2013;110:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2013.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang WQ, et al. Improved salt tolerance in a wheat stay-green mutant tasg1. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018;40(2):39. doi: 10.1007/s11738-018-2617-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, et al. Distribution of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in coastal wetland soil related land use in the Modern Yellow River Delta. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37940. doi: 10.1038/srep37940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao QQ, et al. Effects of water and salinity regulation measures on soil carbon sequestration in coastal wetlands of the Yellow River Delta. Geoderma. 2018;319:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.10.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller JK, et al. Soil organic carbon storage in restored salt marshes in Huntington Beach California. Bull. South. Calif. Acad. Sci. 2012;111(2):153–161. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen W, et al. Soil carbon and nitrogen storage in recently restored and mature native Scirpus marshes in the Yangtze Estuary, China: Implications for restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2017;104:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao S, Zhang W, Ye Y, Zhao J, Wang K. Soil aggregate mediates the impacts of land uses on organic carbon, total nitrogen, and microbial activity in a Karst ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:41402. doi: 10.1038/srep41402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu LQ, et al. Short-term responses of soil organic carbon and carbon pool management index to different annual straw return rates in a rice-wheat cropping system. CATENA. 2015;135:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2015.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghosh BN, et al. Effects of fertilization on soil aggregation, carbon distribution and carbon management index of maize-wheat rotation in the north-western Indian Himalayas. Ecol. Ind. 2018;205:415–424. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sainepo BM, Gachene CK, Karuma A. Assessment of soil organic carbon fractions and carbon management index under different land use types in Olesharo Catchment, Narok County Kenya. Carbon Balance Manag. 2018;13(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13021-018-0091-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang B, et al. Soil microbial community dynamics over a maize (Zea mays L.) growing season under conventional-and no-tillage practices in a rain fed agroecosystem. Soil Tillage Res. 2012;124:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2012.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Six J, et al. Soil organic matter, biota and aggregation in tempérante and tropical soils: Effects of no-tillage. Agronomie. 2002;22:755–760. doi: 10.1051/agro:2002043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang T, et al. Assessing impact of land uses on land salinization in the Yellow River Delta, China using an integrated and spatial statistical model. Land Use Policy. 2011;28:857–866. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qi YB, et al. Desert soil properties after thirty years of vegetation restoration in northern Shanxi Province of China. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2015;29:454–472. doi: 10.1080/15324982.2015.1030799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng BZ. Technical guide to soil analysis. 1. Beijing: China Agriculture Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tisdall JM, Oades JM. Organic matter and water-stable aggregates in soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1982;33:141–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.1982.tb01755.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhong XL, et al. Physical protection by soil aggregates stabilizes soil organic carbon under simulated N deposition in a subtropical forest of China. Geoderma. 2017;285:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kemper WD, Rosenau RC. Aggregate stability and size distribution. In: Klute A, editor. Methods of soil analysis: part I-physical and mineralogical methods. 2. Madison: American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science; 1986. pp. 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ju Z, Du Z, Guo K, Liu X. Irrigation with freezing saline water for 6 years alters salt ion distribution within soil aggregates. J. Soils Sediments. 2019;19:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s11368-018-2017-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nelson DW, Sommers LE. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In: Page, A.L. (ed.). Methods of Soil Analysis, (2nd ed.) ASA Monograph. 1982;9(2):539–579. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vance ED, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987;19(6):703–707. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(87)90052-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blair GJ, Lefroy RDB. Soil C fractions based on their degree of oxidation and the development of a C management index for agricultural systems. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1995;46:1459–1466. doi: 10.1071/AR9951459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghosh BN, et al. Impact of conservation practices on soil aggregation and the carbon management index after seven years of maize–wheat cropping system in the Indian himalayas. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016;216:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2015.09.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.