Abstract

Despite the importance for both animal welfare and scientific integrity of effective welfare assessment in non-human primates, there has been little or no consensus as what should be assessed. A Delphi consultation process was undertaken to identify the animal- and environment-based measures of welfare for laboratory-housed macaques and to determine their relative importance in on-site welfare assessments. One-hundred fifteen potential indictors were identified through a comprehensive literature search, followed by a two-round iterative electronic survey process to collect expert opinion. Stable group response and consensus about the validity, reliability, and feasibility of the proposed indicators (67.5% agreement) was achieved by the completion of Round Two. A substantially higher proportion of environment-based measures (72%: n = 44/61) were considered as valid, reliable, and feasible compared to the animal-based measures (22%: n = 12/54). The indicators that ranked most highly for assessing welfare were the presence of self-harm behaviours and the provision of social enrichment. This study provides an empirical basis upon which these indicators can be validated and then integrated into assessment tools developed for macaques and emphasises the need to include both animal- and environment-based indicators for accurate welfare monitoring.

Subject terms: Animal behaviour, Experimental models of disease

Introduction

The effective assessment of macaque welfare is critical for determining the current welfare state of animals, maintaining and then improving this state, and determining the effectiveness of any efforts made to improve their welfare. Globally, macaques are the most commonly used non-human primate (NHP) in research1,2, for example 3000 procedures carried out on them in United Kingdom3 and comprising 75% of the NHPs expected to be used in research in the United States in 20194. Although NHP research forms a small proportion of the research carried out on animals (e.g. < 0.5% in the United States5), primates play a critical role in some of the most important biomedical research undertaken6. The welfare of these animals is of increasing focus for the public, those who care for these animals, those who regulate their use, and those who use them in their research. The established driver for this is our appreciation for their capacity to suffer and experience positive welfare7, which appears to be potentially greater than most other laboratory animal species. Added to this, is the increasing understanding of the negative impact of poor welfare on the validity of the data collected from such animals8. The more intact the animal, the better the research model9,10. For example, provision of species-appropriate environmental enrichment, like access to social partners, enhances NHP welfare, and consequently, experimental validity and reproducibility11,12.

Currently, there is no consensus on the welfare indicators for laboratory-housed macaques beyond those that are often used as evaluative tools to determine compliance with minimum standards of care which are more akin to risk assessments. These are primarily legislative or accreditation-driven, and so are often more focused on ensuring intact animal models for quality science13. They tend to rely heavily on the assessment of environmental parameters describing management practices and environment features (e.g. inputs), as they are objective and easy to measure accurately14,15. However, to more effectively evaluate the welfare state of an individual per se, we should be assessing quantifiable animal-based outcome indicators, as they represent animals’ reaction (e.g. behaviour, physiology, and health) to the environment (outputs)14,16–19 and other aspects of captivity. The use of animal-based output measures either alone20 or in combination with the assessment of environment-based inputs21,22 is critical for robust and effective assessment of welfare assessment that reflects welfare as a dynamic entity23,24 on a multi-dimensional continuum rather than as “good” or “poor”17,25,26. The modern assessment of farm animal welfare has been using such an approach for more than 40 years (e.g. Welfare Quality assessment protocols27) and was suggested as a framework for how to evaluate and promote captive NHP welfare 30 years ago28.

To effectively evaluate welfare of laboratory-housed macaques and, in turn, make recommendations for future improvement requires effective assessment of welfare, as these allow us to benchmark the current welfare state and identify any improvement. Such benchmarking ensures the existing empirically based refinement recommendations involving human influence, the environment, and management practices29–31 that are often underutilized (e.g. positive reinforcement training32–34) are effectively applied, and new means of defining and mitigating poor welfare in captive NHPs (e.g. self-injurious behaviour35,36, output of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis37) are tested and validated. Development of an additional welfare tool for use in regulatory assessment, for in-house benchmarking, and to increase public transparency and trust, would be beneficial to ensure welfare standards are met and to strengthen scientific validity of primate-based studies.

Despite some efforts to identify effective indicators for assessing macaque welfare38,39, no attempt has been made to collectively define what they are, whether they are effective (i.e. valid, reliable and feasible), and how they can be used. Parameters should show content validity (i.e. assessing all aspects of welfare), reliability (i.e. can be consistently measured across and between users), and feasibility (i.e. can be measured with limited time, resources, and within facility constraints)14,40–43. Validation involves initially establishing that an indicator meets each of these criteria in a captive environment (see Welfare Quality project as a model44). This process is necessary to design and implement assessment tools for the identification of both the causes of and areas for improvement for diminished welfare41. One method of identifying indices thought to reflect an animal’s welfare is the Delphi consultation, which consists of a multi-round process (usually two to three) of questionnaire administration and controlled feedback to a panel of experts (i.e. stakeholders who interact with NHPs in varying capacities) from various backgrounds who participate anonymously; their responses are used to reach a group consensus on a topic, as indicated by response stability between rounds45–48. This approach has been used previously to identify welfare indicators for species maintained on farm (e.g. dairy cows, laying hens, pigs49; broiler chickens50), in semi-captive environments (e.g. elephants involved in wildlife tourism51; dogs in catch-neuter-release programs52), and in the laboratory (mice21,22). This systematic approach is more rigorous than other group consensus approaches, like case studies or focus groups, because of its reliance on scientific evidence and involvement of expert opinion, which results in enhanced decision-making, identification of quality indicators, and the confluence of expertise47.

The aim of this study was to use a Delphi consultation process to identify and determine the relative value of different potential measures of laboratory-housed macaque welfare based on the validity, reliability, and feasibility of the measures.

Results

Demographics

Of the 39 experts who completed the two survey rounds, 74% had some form of post-graduate qualification (n = 29/39), and 62% had more than 10 years’ experience with macaques (n = 24/39). Eighty percent of the experts (n = 31/39) had experience with both of the two macaque species most utilized in research, M. mulatta (n = 39/39; 100%) and M. fascicularis (n = 31/39; 80%). Ninety percent of the experts were North American (n = 35/39).

Behavioural management, animal welfare, and research-oriented experts comprised 74% of the panel (n = 29/39), with veterinary medicine (18%; n = 7/39), and animal care, colony management, and unlisted but related occupations (8%; n = 3/39) making up the remainder of the panel. (see Supplementary Tables S1–S3 online for all demographics data).

Survey

Consensus and group stability

There was a significant effect of individual respondent (F1, 26906 = 4.71, p = 0.030), survey round (F1, 26906 = 10.22, p = 0.001), and indicator (F1, 26906 = 286.54, p < 0.001) on survey response (Table 1). Strong stability in individual responses across both within and between rounds is illustrated by back-transformed means (Table 1), which approached a high degree of stability in Rounds One and Two and did not appreciably change between these rounds.

Table 1.

Consensus and group stability of welfare indicators: generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) 1 [respondent, round, indicator (fixed effects); respondent (random effect)].

| Mean | Back-transformed mean | SEM (avg) | SEM (lower) | SEM (upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | |||||

| 1 | 0.8349 | 0.6974 | 0.01908 | 0.01891 | 0.01925 |

| 2 | 0.9211 | 0.7153 | |||

Group stability, or the consistency of participant responses between successive iterations of a survey53, amongst the 39 experts who participated in both rounds was assessed with Krippendorff’s alpha test of the responses they provided on 115 indicators with three response types (validity, reliability, feasibility). The group’s level of disagreement across all 345 items was high in both rounds (Round 1, α = 0.1947; Round 2, α = 0.1358); however, levels remained relatively consistent between rounds (Δ 0.0589) and the movement that did occur was in the direction of agreement (signifying convergence, i.e. consensus).

Across the 115 proposed welfare indicators, the overall consensus (for validity, reliability, feasibility) was 67.5% (n = 233/345) agreement. Within this, consensus for validity, reliability, and feasibility was 73% (n = 84/115), 63% (n = 72/115), and 67% (n = 77/115) respectively. This varied according to indicator type, with 63% respondent agreement for animal-based indicators and 86% for environment-based indicators.

Fifty-six of the 115 indicators (49%) were considered valid, reliable, and feasible at the set level of ≥ 70% agreement. This comprised of 12 animal- and 44 environment-based measures (Tables 2, 3). Consensus that an indicator was less valid, reliable, or feasible was reached for two indicators: acute phase proteins and telomere length (animal-based measures). The remaining indicators either approached consensus (65–69.99%) for either validity, reliability, or feasibility, or there was mixed agreement amongst the experts (dissensus). Supplementary Table S4 online shows a complete listing of agreement for the 115 welfare indicators by response type.

Table 2.

Animal-based welfare indicators reaching consensus by percentage agreement scores.

| Indicator description | Valid (%) | Reliable (%) | Feasible (%) | Composite score (avg of V + R + F) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appetite | 92.3 | 79.5 | 82.1 | 84.6 |

| Blood in waste | 94.9 | 89.7 | 82.1 | 88.9 |

| Body weight | 79.5 | 79.5 | 94.9 | 84.6 |

| Discharge | 87.1 | 82.1 | 82.1 | 83.8 |

| Dyspnoea | 94.9 | 82.1 | 89.7 | 88.9 |

| Huddled posture | 89.7 | 76.9 | 92.3 | 86.3 |

| Injuries, environmental | 84.6 | 71.8 | 82.1 | 79.5 |

| Injuries, non-human primate | 92.3 | 79.5 | 82.1 | 84.6 |

| Mortality | 79.5 | 82.1 | 79.5 | 80.3 |

| Prolapse | 71.8 | 71.8 | 76.9 | 73.5 |

| Self-harm behaviours | 100.0 | 87.2 | 94.9 | 94.0 |

| Stereotypical behaviours | 82.1 | 87.2 | 97.4 | 88.9 |

Table 3.

Environment-based welfare indicators reaching consensus by percentage agreement scores.

| Indicator description | Valid (%) | Reliable (%) | Feasible (%) | Composite score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal caregiver observations | 97.1 | 76.5 | 91.2 | 88.3 |

| Behavioural management program | 100 | 88.2 | 94.1 | 94.1 |

| Browse provision | 88.2 | 76.5 | 91.2 | 85.3 |

| Cage complexity | 88.2 | 79.4 | 73.5 | 80.4 |

| Cage dimension | 79.4 | 85.3 | 88.2 | 84.3 |

| Cage furniture | 97.1 | 91.2 | 88.2 | 92.2 |

| Cage position | 85.3 | 79.4 | 88.2 | 84.3 |

| Chair restraint frequency | 85.3 | 76.5 | 79.4 | 80.4 |

| Destructible enrichment | 94.1 | 82.4 | 88.2 | 88.2 |

| Disease surveillance | 100 | 85.3 | 91.2 | 92.2 |

| Experiments, lifetime | 73.5 | 67.6^ | 85.3 | 79.4 |

| Field of view | 85.3 | 82.4 | 76.5 | 81.4 |

| Food enrichment | 97.1 | 94.1 | 97.1 | 96.1 |

| Food variety | 88.2 | 82.4 | 97.1 | 89.2 |

| Health monitoring | 100 | 94.1 | 100 | 98.0 |

| Hear other NHPs | 88.2 | 91.2 | 97.1 | 92.2 |

| Humane euthanasia program | 100 | 94.2 | 100 | 98.1 |

| Humidity | 76.5 | 85.3 | 88.2 | 83.3 |

| Inoculations, lifetime | 79.4 | 82.4 | 88.2 | 83.3 |

| Light intensity | 79.4 | 85.3 | 88.2 | 84.3 |

| Manipulanda | 88.2 | 79.4 | 94.1 | 87.2 |

| Moves, lifetime | 91.2 | 76.5 | 73.5 | 80.4 |

| Novelty exposure, intentional | 85.3 | 82.4 | 97.1 | 88.3 |

| Number of meals, daily | 76.5 | 79.4 | 97.1 | 84.3 |

| Physical enrichment | 100 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 96.1 |

| Positive reinforcement training | 94.1 | 82.4 | 79.4 | 85.3 |

| Rearing history | 100 | 85.3 | 76.5 | 87.3 |

| Room cleaning frequency | 88.2 | 88.2 | 91.2 | 89.2 |

| Sedations, lifetime | 91.2 | 82.4 | 79.4 | 84.3 |

| See humans | 79.4 | 70.6 | 73.5 | 74.5 |

| See other non-human primates | 73.5 | 91.2 | 82.4 | 82.4 |

| Sensory enrichment | 85.3 | 73.5 | 85.3 | 81.4 |

| Social density | 82.4 | 88.2 | 76.5 | 82.4 |

| Social enrichment | 94.1 | 91.2 | 97.1 | 94.1 |

| Staff training | 97.1 | 70.6 | 88.2 | 85.3 |

| Surgeries, lifetime | 97.1 | 85.3 | 94.1 | 92.2 |

| Temperature of room | 85.3 | 94.1 | 97.1 | 92.2 |

| Timing of meals, daily | 73.5 | 73.5 | 91.2 | 79.4 |

| Ventilation | 94.1 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 94.1 |

| Vertical space | 85.3 | 85.3 | 79.4 | 83.3 |

| Vet med procedures, lifetime | 82.4 | 76.5 | 79.4 | 79.4 |

| Visual barrier, between caging | 82.4 | 91.2 | 97.1 | 90.2 |

| Visual barrier, within caging | 82.4 | 88.2 | 82.4 | 84.3 |

| Weaning age | 85.3 | 76.5 | 76.5 | 79.4 |

The top animal-based indicators predominately focused on behaviours and health and appearance measures, whereas, for the environment-based indicators, the focus was on enrichment, environment, and management practice measures (Table 4).

Table 4.

Top ten animal- and top ten environment-based indicators by composite percentage agreement score after Round Two.

| Indicator type | Indicator description | Valid (%) | Reliable (%) | Feasible (%) | Composite score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal-based | Self-harm behaviours | 100 | 87.2 | 94.9 | 94.0 |

| Blood in waste | 94.9 | 89.7 | 82.1 | 88.9 | |

| Dyspnoea | 94.9 | 82.1 | 89.7 | 88.9 | |

| Stereotypical behaviours | 82.1 | 87.2 | 97.4 | 88.9 | |

| Huddled posture | 89.7 | 76.9 | 92.3 | 86.3 | |

| Appetite | 92.3 | 79.5 | 82.1 | 84.6 | |

| Injuries, NHP-induced | 92.3 | 79.5 | 82.1 | 84.6 | |

| Body weight | 79.5 | 79.5 | 94.9 | 84.6 | |

| Discharge | 87.1 | 82.1 | 82.1 | 83.8 | |

| Fear of NHPs | 92.3 | 69.2^ | 89.7 | 83.7 | |

| Environment-based | Humane euthanasia program | 100 | 94.2 | 100 | 98.1 |

| Health monitoring program | 100 | 94.1 | 100 | 98.0 | |

| Food enrichment | 97.1 | 94.1 | 97.1 | 96.1 | |

| Physical enrichment | 100 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 96.1 | |

| Social enrichment | 94.1 | 91.2 | 97.1 | 94.1 | |

| Ventilation | 94.1 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 94.1 | |

| Behavioural management program | 100 | 88.2 | 94.1 | 94.1 | |

| Hear other NHPs | 88.2 | 91.2 | 97.1 | 92.2 | |

| Cage furniture | 97.1 | 91.2 | 88.2 | 92.2 | |

| Temperature of room | 85.3 | 94.1 | 97.1 | 92.2 |

^Indicates approaching agreement at a level of 65–69.99% agreement.

Ranking of welfare measures between rounds

For the top indicators in Round Two (Table 4), the inter-rater agreement (i.e. consensus) concerning the ranking of the top 20 indicators (10 animal- and 10 environment-based) selected from Round One, was good (W = 0.703 (P < 0.001)); however, there was some movement of items within Round Two (Table 5). Based on composite expert scores (n = 39) in Round Two, only five of the 10 animal-based indicators (50%) and nine of the 10 environment-based indicators (90%) from Round One were still considered valid, reliable, and feasible (Table 5) in Round Two. The remaining animal-based indicators were rated as less reliable (anxiety, body condition score, affiliative behaviours), less reliable or feasible (species-typical behaviour at abnormal levels), and less valid, reliable, or feasible (activity level), and so did not appear in the Round Two top indicators. For the remaining environment-based indicators, only qualifications/training of staff was not rated as valid, reliable, and feasible; four additional indicators (complexity of the cage/enclosure, daily observation by animal caregivers, cage/enclosure dimension, positive reinforcement training program) were considered as valid, reliable, and feasible, but dropped out of the top 10 highest ranked environment-based indicators based on composite scores (Table 5). Agreement about the ranking order of those indicators that were found in both Rounds One and Two improved between rounds.

Table 5.

Expert ranking of welfare measures.

| Indicator type | Indicator | Round One (n = 111) | Round Two, final (n = 39) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group rank | Respondent agreement (%) | Group rank | Respondent agreement (%) | Composite score (%) | ||

| Animal-based | Self-harm behaviours* | 1 | 60.2 | 1 | 94.9 | 94.0 |

| Species-typical behaviour at abnormal levels# | 7 | 19.5 | 2 | 69.2 | 63.2 | |

| Appetite* | 4 | 36.3 | 4 | 64.1 | 84.6 | |

| Anxiety behaviours^ | 3 | 41.6 | 4 | 64.1 | 80.3 | |

| Body condition score^ | 9 | 15.9 | 4 | 64.1 | 77.8 | |

| Affiliative behaviours^ | 6 | 26.6 | 6.5 | 61.5 | 73.5 | |

| Activity level## | 8 | 17.7 | 6.5 | 61.5 | 56.4 | |

| Stereotypical behaviours* | 2 | 46.0 | 8 | 59.0 | 88.9 | |

| Injuries, NHP-induced* | 5 | 31.9 | 9 | 53.8 | 84.6 | |

| Body weight* | 9 | 15.9 | 10 | 38.5 | 84.6 | |

| Environment-based | Social enrichment* | 1 | 54.0 | 1 | 94.9 | 94.9 |

| Complexity of the cage/enclosure* | 10 | 19.5 | 2 | 66.7 | 80.3 | |

| Behavioural management program* | 2 | 42.5 | 3 | 64.1 | 93.2 | |

| Daily observation by animal caregivers* | 3 | 39.8 | 4 | 61.5 | 88.9 | |

| Cage/enclosure dimension* | 9 | 22.1 | 5 | 59.0 | 84.6 | |

| Positive reinforcement training program* | 4 | 25.7 | 6 | 56.4 | 86.3 | |

| Health monitoring program* | 6 | 24.8 | 7 | 48.7 | 97.4 | |

| Food enrichment* | 4 | 25.7 | 8.5 | 23.1 | 96.6 | |

| Qualifications/ training of staff^ | 6 | 24.8 | 8.5 | 23.1 | 70.1 | |

| Physical enrichment* | 6 | 24.8 | 10 | 17.9 | 96.6 | |

Italics = indicators eliminated from experts’ top 10 between rounds one and two.

*Valid, reliable, and feasible.

^Less reliable.

#Less reliable or feasible.

##Less valid, reliable, or feasible.

Welfare measures by indictor type

Indicator type influenced response selection (Table 6); specifically, environment-based indicators were selected more across rounds One and Two than animal-based indicators. A binomial test indicated that the proportion of animal-based indicators of 0.47 was lower than the expected 0.51, P < 0.001 (1-sided). Back-transformed means in this model again confirm that the responses between rounds remained stable. Additionally, respondents found indicators to be valid more than they did feasible or reliable.

Table 6.

Selection of animal- and environment-based indicators across rounds One and Two: GLMM 2 [round, indicator type, response type (fixed effects); respondent (random effect)].

| Mean | Back-transformed mean | SEM (avg) | SEM (lower) | SEM (upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | |||||

| 1 | 0.8540 | 0.7014 | 0.01933 | 0.01916 | 0.01951 |

| 2 | 0.9421 | 0.7195 | |||

| Indicator type | |||||

| Animal-based | 0.5249 | 0.6283 | 0.01935 | 0.01845 | 0.02026 |

| Environment-based | 1.2712 | 0.7809 | |||

| Response type | |||||

| Valid | 1.0623 | 0.7431 | 0.02367 | 0.02307 | 0.02448 |

| Reliable | 0.7727 | 0.6841 | |||

| Feasible | 0.8590 | 0.7025 | |||

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify and determine the relative value of different potential measures of laboratory-housed macaque welfare through expert consultation about the validity, reliability, and feasibility of the measures. The overall level of consensus reached by the experts as to 115 measures that should be used to assess macaque welfare based on their validity, reliability, and feasibility was 67.5%. This was just below the pre-determined level of 70% agreement necessary for consensus as applied in other welfare studies21,54,55. Attempting to reach ≥ 70% consensus on all 115 indicators over three factors was always going to be a challenge and is more complex than other studies in other contexts21,55. As such, the consensus of 67.5% was deemed sufficient for this study as important insight was gained in breaking down the indicators into categories55. For almost half of the indicators (n = 57), consensus was approached (65–69.99%) or there was mixed agreement/dissensus (see Supplementary Table S4 online); this is likely due to a combination of factors including the specific indicator, the supplied on-site assessment scenario within the survey instrument, and differences in the demographics of the experts. A third round was not pursued as consensus (67.5%) was only just short of the predetermined level of 70% for the 115 indicators. The diminished rate of return for the second round (n = 72) was more than twice what was expected, suggesting that an additional round would result in too few respondents for any relevant analysis. Nonetheless, there were enough respondents in Round Two (n = 39) to reach reliable consensus56. This is further supported by the relatively high group stability observed between rounds, serving as a secondary criterion for termination of the iterative process48,57. The responses of the experts were generally consistent, both as individual (i.e. within an expert) and as a group (i.e. between experts), leading to high between-round stability. This could be either due to the group feedback provided from Round One inducing little change in their responses in Round Two, i.e. they remained firm in their original Round One choices despite the feedback, or that respondents ignored the feedback from Round One, which would also lead to round stability.

The group agreed that environment-based measures of welfare are better suited for on-site assessment than animal-based ones. Although animal-based measures were considered as valid, experts did not consider as many of them to be either as reliable or feasible to measure (see Supplementary Table S4 online), echoing the difficulties found in practically using them in welfare assessment protocols58. The European Food Safety Authority’s Panel on Animal Health and Welfare17 recommends assessing validity (i.e. whether the indictor measures and reflects a welfare outcome) of animal-based welfare indicators via study-based validation, which has not been completed for most in use for macaques as evidenced by the dearth of literature on the topic, or by expert opinion, as done in this study. The experts reaching consensus concerning the validity, reliability and/or feasibility of the 115 indicators presented (animal- and environment-based) in this study implies that these indices can now be used as a form of benchmark. Other indices that are used currently for welfare assessment but have yet to be validated or novel indices that have not been used can be compared against the indices identified in this study, for example some of the animal-based items listed on the NC3Rs website on macaques59.

Observable behaviour, an animal-based indicator, is most typically used to assess macaque welfare60, as well as the welfare of other laboratory-housed animals61, because of its ease in collection (i.e. feasibility). Furthermore, the expression of abnormal behaviour, which includes stereotypical/abnormal repetitive and self-harm behaviours, among others, is thought to reflect poor welfare as it is either pathological or associated with environmental coping36,62 and so is often used as a proxy for welfare61,63,64. However, many types of observable behaviour are yet to be validated as a means of assessing welfare and are only now being empirically explored to define their role in macaque welfare assessment (e.g. hair-loss as a biomarker for stress65).

The results of this study serve to narrow the field of indices requiring validation, lend some credence to those currently used to measure welfare within the laboratory (e.g. abnormal behaviour), and highlight indices that are not considered effective for welfare assessment. For example, telomere length was specifically rejected as experts agreed that it is not valid, reliable, or feasible to measure within a half-day site visit. Further, this Delphi study can be viewed as a starting point for eventual scientific assessment of macaque welfare, as has been done in similar studies with other captive species, like commercial finishing pigs49,66 and laboratory mice21,22,67.

In addition to confirming potential indicators, experts were asked to place a relative value on them. Experts were asked to rank the top ten most important animal and environmental indicators for welfare assessment without guidance (i.e. based on validity, reliability, or feasibility). Across rounds, experts agreed that self-harm behaviours and provision of social enrichment are the most important indicators for assessing macaque welfare. These are in-line with the focus of research publications specific to laboratory-housed macaques, including on how to minimize or treat self-harm behaviours35,36,68–74, and the importance of social housing12,75,76, and associated techniques77,78 and so emphasising the utility of these findings. Agreement of the ranking of each item improved between rounds; however, this could be attributed to a smaller sample in Round Two or to the composition of the panel. Heterogeneity of a group is thought to lead to better results within a group decision-making process47; however, nearly half of those completing both rounds were employed in behavioural management or animal welfare positions. It is likely that those who opted to participate in each survey round not only have a vested interest in the finished product in their occupation (i.e. a list of macaque welfare indicators), but also share similar selection criteria for indicator ratings. The composite score percentage agreement of the items identified as the top welfare measures (Table 5) indicates dissensus as to the order of their importance. For example, activity level, included in the ranking of welfare measures from Round One, was rejected in Round Two as not valid, reliable, or feasible. Body weight, an indicator deemed valid, reliable, and feasible, is ranked 10th most important as an animal-indicator, but there is disagreement as to where it should rank as only 38.5% of experts agree to its positioning. Other items were less reliable or both less reliable and less feasible, suggesting that validity was the primary consideration in the ranking of items. The top welfare indicators by composite percentage agreement score (Table 4) indicate that reliability is a concern for experts more so than feasibility and validity (i.e. percentage agreement scores are lower for reliability) with both indicator types; this may be related to the subjective judgements involved with observer ratings while conducting assessments.

While observer ratings have been widely used for many types of research and can be practical to implement (e.g. welfare monitoring in zoos79; QBA of sheep80), they can be influenced by knowledge and experience61 and subject to expectation bias, in which an opinion is shaped by non-task-related information especially confirmatory information81. For example, if a caretaker is asked to report the occurrence of abnormal behaviours in an individual, they might spend more time observing that animal than in their normal routine, looking for any occurrence; a newly trained caretaker might report more types and higher occurrences of such behaviours than a seasoned individual because of uncertainty in what they are observing. This bias, along with fear of anthropomorphism and the reliance of interpretation on an animal’s experience82, may be why there is hesitancy to implement and draw conclusions from observer ratings in some circumstances, such as on-site welfare assessment. However, observer ratings are unavoidable if relevant welfare indicators, particularly behavioural ones, are to be included in a comprehensive assessment tool. To be useful in an on-site assessment, ratings must be valid, reliable, and feasible. Reliability, the extent to which a measurement is repeatable and consistent (reproducible), hinges upon operationally defining measurement techniques, and adequately defining what it is that is being measured, both of which can impact inter-observer and test–retest reliability83. For example, detailed scoring systems with multiple classes can pose reliability issues as there are more opportunities for disagreement in scoring; collapsing classes where possible could alleviate reliability issues, but risks elimination of data that might be helpful in discriminating between levels of welfare84. Nevertheless, scoring systems, like those used to measure alopecia85,86 and body condition87,88 in macaques, can be successfully implemented as along as inter- and intra-observer reliability are regularly assessed. Indicator usefulness will be determined by whether people can use it to assess welfare, despite difficulties; hence the importance for empirical-based evaluations that explore and define the potential limitations of each for on-site assessment.

There was little difference in the number of parameters offered for rating between the two indicator types, yet experts selected more than three times the number of environment-based input measures (72%) as valid, reliable, and feasible for on-site welfare assessments compared to the animal-based output measures (22%). There may be several reasons for this based on the characteristics of each indicator type. Although environmental input parameters have the potential for low validity since they are indirect measures of welfare and can be experienced differently by the individual, they are typically easier to measure (i.e. more feasible) and can be more reliably measured between raters43. For example, measuring temperature of a room is simple enough—it requires little time to measure, is low cost because of no associated training or extra equipment, and can be measured repeatedly across raters and visits. In contrast, even though outcome or performance measures assessed directly from the animal, like behavioural or health measures, are likely to reflect the actual welfare state of the individual17, they are often time-consuming to assess, pose reliability problems, and can be impractical if difficult to measure, especially when trained personnel are required to gather data (e.g. veterinary personnel to sample blood). If, for instance, an assessor was interested in macaque hair loss, they would have to either score all or a sample of the population of the animals or rely on in-house records, if they exist. Next, they would need to address temporal considerations (e.g. when did the hair loss occur?) and factors associated with data collection (e.g. are personnel adequately trained? have behavioural and/or veterinary courses of action been pursued for causality and treatment?). Finally, they would need to contextualize the welfare indicator (e.g. is the hair loss associated with a research study that typically results in hair loss or is it due to over-grooming in a social pair?). Identifying welfare indicators is the first step in providing scientific-based guidance for managing perceived welfare issues; clearly, validation to simplify some of this process, especially for animal-based indicators, is needed.

The ability of the environment-based measures to be implemented quickly to a large population of animals (i.e. large colony) is of particular importance for laboratory animals such as macaques. Unlike other captive environments like zoos and sanctuaries, laboratories sometimes house more primates, and individuals can be found in a range of housing types, such as outdoor corrals, indoor-outdoor runs, or indoor caging; assessing these populations in a day or less poses challenges similar to farm assessments, like implementation of animal-based indicators. Although, a population size was provided in the scenario for the survey, optimal sampling sizes and observation periods for each indicator were not, as they have yet to be established. Establishing these via a Delphi process, as Leach and colleagues21 did in their study identifying assessment measures of welfare for laboratory mice, could drastically alter respondent answers. If respondents could indicate validity, reliability, and feasibility within the context of multiple sampling scenarios, this might be more informative than the approach taken in this study and might reveal the scenarios in which animal-based indicators are preferred.

To effectively evaluate the present welfare status of an animal and measure improvement of that state over time based on any management interventions, it is important that all components of welfare be measured and in a meaningful way. This study provides an empirical basis upon which to start the validation of indicators that can be integrated into assessment tools developed for macaques and emphasizes the need to include both environment- and animal-based indicators in any such tools for accurate welfare monitoring. This study provides guidance on the next steps for developing a tool to help ensure good welfare, rather than just meeting minimum standards of care. Expert respondents have provided a list of animal- and environment-based items considered valid, reliable, and feasible for on-site assessment, most of which need to undergo empirical assessment in a variety of captive environments (e.g. laboratories, zoos, sanctuaries). These indicators may be helpful to zoos, for example, as they could be integrated into existing tools for assessing smaller populations of macaques (e.g. Detroit Zoological Society Individual Animal/Environment Welfare Assessment89). Application of the Delphi consultation process with zoo employees and stakeholders in other captive environments could be beneficial so that cross-environment indicators can be identified and validated; this is of particular importance as more laboratory NHPs are retired and move to different surroundings. Once validation is undertaken, development of a comprehensive welfare assessment tool, one that includes negative and positive measures of welfare, can be explored.

Methods

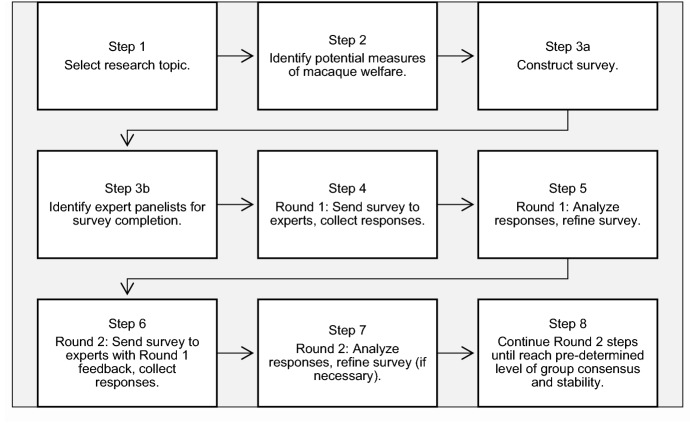

The modified Delphi consultation process was completed using steps illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Steps in a modified Delphi process.

Ethical consideration

Data collection procedures were approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee, University of Edinburgh (approval #HERC_157_17). Due to the iterative nature of the Delphi consultation process (i.e. the need to tie responses to users to provide individualized feedback), quasi-anonymity was maintained—responses remained unknown to other participants but were known to the researchers. However, to maximize anonymity, response data were coded by username after receipt so that individuals’ responses could not be readily linked and identifying information and data results were kept separate always. All data were handled and stored in compliance with the UK Data Protection Act 1998.

Identification of initial list of indicators

A list of 115 potential measures of laboratory-housed macaque welfare was generated using multiple literature searches on Web of Science between January 1965 and August 2017; English language results were used to search abstract content and titles. A total of 709 unique results were yielded from the following keywords and phrases: health, macaque(s), primate(s), macaca, welfare, well-being, P(sychological)W(ell)B(eing), alopecia, quality of life; ape(s), orangutan(s), and chimp(anzee)(s) were excluded. Potential welfare indicators were selected if an item was related to the welfare, quality-of-life, or well-being of macaques. Items related to environmental enrichment, housing, and health and management practices were categorized as environment-based (input) measures; those related to the animals’ appearance and physical health and the behavioural and physiological response to the environment were categorized as animal-based (output) measures (see Fig. 1, Steps 1–2).

The initial list of 115 potential indicators comprised 61 environment-based and 54 animal-based items (Tables 7 and 8).

Table 7.

Initial list of potential environment-based indicators.

| Enrichment | Environment | Health and management practices |

|---|---|---|

| Access to exercise/play area | Auditory access to neighbouring conspecifics | Behavioural management program |

| Browse provision | Cage/enclosure dimension | Blunting of canine teeth |

| Frequency of exposure to novel items, intentional (e.g. toys) | Cage/enclosure furniture (e.g. swings, ladders, perching) | Daily observation by animal caregivers |

| Frequency of exposure to novel items, unintentional (e.g. new uniform) | Clear visual access to approaching humans | Disease surveillance & diagnosis |

| Multiple manipulanda in/on caging/enclosure | Clear visual access to neighbouring conspecifics | Frequency of handling by humans: chair restraint |

| Positive reinforcement training (PRT) program | Complexity of the cage/enclosure | Frequency of handling by humans: hand-catching |

| Provision of cognitive/occupational enrichment (e.g. computerized tasks, exercise opportunities) | Escape-proof enclosures (e.g. self-closing doors) | Health monitoring program |

| Provision of destructible enrichment (e.g. cardboard, paper, wood) | Exterior windows to hallways or outdoors | Humane euthanasia procedure |

| Provision of food enrichment | Flooring type | Inoculation history per lifetime |

| Provision of materials for thermoregulation | Frequency of enclosure/room cleaning procedures | Meals per day, number |

| Provision of natural materials in housing | Humidity, room | Meals per day, timing |

| Provision of physical enrichment | Increased field of view (e.g. provision of cage extension/porch, mirror) | Number of moves within/between caging/housing areas per lifetime |

| Provision of sensory (visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory, olfactory) enrichment | Intensity of lighting | Number of sedations/anesthetizations per lifetime |

| Provision of social enrichment | Light source (fluorescent, natural) | Number of surgical procedures (major, minor) per lifetime |

| Substrate type | Noise levels | Number of times participated in an experiment per lifetime |

| Variety of enrichment food types | Position of the caging in the room | Number of veterinary procedures per lifetime |

| Presence of vibration | Qualifications/training of staff | |

| Social density | Quality of life assessments | |

| Social stability | Rearing history | |

| Spatial density | Weaning age | |

| Temperature, room | ||

| Ventilation, room | ||

| Vertical space | ||

| Visual barrier(s), between caging | ||

| Visual barrier(s), within caging |

Table 8.

Initial list of potential animal-based indicators.

| Appearance and health measures | Behaviour | Physiology and genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Alopecia score | Abuses/neglects infant | Acute phase proteins |

| Ambulation/gait | Activity level | Blood pressure |

| Appetite | Affiliative behaviour with conspecific(s) | Body temperature |

| Atrophy | Aggressive behaviour with conspecific(s) | Body weight |

| Blood in urine/stool | Anxiety behaviour | Cortisol concentration |

| Body condition score | Cagemate(s) behaviour towards individual | Genotype |

| Coat condition | Decreased maintenance behaviours | Heart rate |

| Coughing | Excessive fear of or withdrawal from conspecifics | Heterophil: lymphocyte ratio |

| Discharge, ocular/nasal | Facial expression, changes in | Lymphocyte activity |

| Dyspnoea (laboured breathing) | Huddled posture | Respiration rate |

| Fatigue/lethargy | Neophobia | Telomere length |

| Fertility/Ability to produce offspring for non-sterilized individual | Overgroom/hair pluck of cagemate(s) | |

| Growth/development rate | Piloerection | |

| Hydration status | Play | |

| Injuries, environmentally induced | Reaction to human approach: Aggressive | |

| Injuries, self- or cagemate-induced (e.g. bite wound) | Reaction to human approach: Fearful | |

| Morbidity rate | Self-harm behaviours | |

| Mortality rate | Species-typical behaviour at abnormal levels | |

| Number of diarrhoea diagnoses per lifetime | Stereotypical/abnormal repetitive behaviours | |

| Prolapse | Vocalizations | |

| Prostration | ||

| Urination, excessive or lack of | ||

| Water intake |

Panel formation

The aim was to purposively sample approximately 400 qualified persons to meet the set response rate of 25% for Round One (n = 100), adequate for a Delphi survey49. The rate of attrition between Delphi rounds is reported at 30%90; this would leave 70 potential respondents for a second round, more than the 25–60 needed to reach reliable consensus56. A relatively poor response rate in a Delphi process is expected because of its iterative nature46,91.

Concurrent with survey construction, a research panel was formed. The panel was comprised of participants with expertise in one or more of the following fields as they pertain to captive Macaca: veterinary medicine, behavioural management/animal welfare, animal husbandry, facility management, and research. For inclusion, panellists had to be 18 years or older and have more than one year of experience working with or studying one or more macaque species. Purposive and snowball sampling resulted in a total of 477 panellists that were asked to participate. Prospective respondents were identified through authorship of the literature reviewed for potential indicators, the professional network of the researchers, and employment of a snowballing technique92 (Fig. 1, Step 3b).

Data collection

Survey—Round One: piloting and finalization

The survey was created using the Bristol Online Survey (BOS) software (Jisc 2017), and consisted of multiple sections: project information and participant consent request; demographics questions to establish subject eligibility; the rating of macaque welfare indicators; and the selection of indicators viewed as the most important for macaque welfare assessment. The survey was reviewed in a two-part piloting phase by 12 persons that included both laypersons and non-macaque captive NHP experts. This pilot panel ensured face and content validity of indicators, the appropriateness of the questionnaire items in relation to the study aims, and that the survey was properly categorized, organized, functional, clear, for an approximate completion time of 25 min. Pilot test phase respondents did not serve as survey respondents; their feedback was incorporated in the version of the survey created for Round One distribution (see Supplementary Fig. S5 online for example of Round One survey).

Survey—Round One

Two versions of the Round One survey were created for randomized equal distribution between the potential respondents to minimize response order effects; the order of the environment-based and animal-based items were swapped; the surveys were otherwise identical (Fig. 1, Step 3a).

Initially, demographic questions were asked relating to Macaca experience, occupation, education, age, and country of residence. This was then followed by participants being asked to rate the 115 potential indicators provided as valid, reliable, and feasible (or not). They could also select “undecided” when considering each measure and add missing indicators (if desired). These questions were asked within the context of the following half-day welfare assessment scenario:

‘Assume that you are participating in a welfare audit in an institution housing approximately 500 macaques. Individuals are housed indoors in 25 animal rooms which each hold 5 racks; each rack holds 4 cages and each cage houses 1 monkey. Monkeys are either singly housed with access to one cage or are socially housed in pairs or groups with access to multiple adjacent cages (1 per animal) within a single rack; some individuals are participating in active research studies’.

The participants were then asked to choose a total of ten animal and ten environmental indicators they thought most important for assessing macaque welfare from the provided list of 115 items; they were not given guidance in how to select these (e.g. the most valid or the most feasible). Definitions were provided for these terms: welfare, indicator, valid, reliable, and feasible.

One-hundred fourteen respondents from eight countries (Canada, England, France, Germany, Netherlands, South Africa, Taiwan, USA) completed the survey (24% response rate) between the allotted period, 17 January to 7 February 2018. Three responses were discarded as two respondents did not meet inclusion criteria and one withdrew (Fig. 1, Step 4). Responses were analysed to compile response feedback and the survey was refined for Round Two (Fig. 1, Step 5).

Survey—Round Two

For the second round of the consultation process, an electronic survey was created using Microsoft Excel (2016) and distributed electronically to the 111 qualified participants who completed the first-round survey. Each participant received a personalized survey (see Supplementary Fig. S6 online for example of Round Two survey) based on the results of Round One that included their responses to the questions posed, the combined responses of the group, presented as respondent percentage agreement (i.e. controlled feedback, Fig. 1, Step 6), and the ten measures most selected by respondents from both the animal- and environment-based indicators in the form of group agreement (%) and each indicator’s rank position. Participants were initially given the opportunity to alter their choices (or not) relating to the 115 potential welfare indicators from Round One, in terms of their validity, reliability, and feasibility in the context of the same hypothetical scenario (described in Round One), and to re-rank the top ten animal- and top ten environment-based indicators if they disagreed with the presented order from Round One.

A total of 39 surveys were returned (35% response rate) in the provided response time, 18 February to 11 March 2018. Participants were from Canada, France, South Africa, and the United States. Responses were analysed to determine whether the group had reached consensus and response stability on the presented indicators; this informed whether a third round was necessary (Fig. 1, Steps 7–8).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were generated by SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 2013; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and GenStat (GenStat for Windows, 19th edition 2017; VSN Intl, Hemel Hempstead, UK) statistical packages, and Excel 2016 for graphical output. Non-parametric statistical procedures were used due to the relatively small sample size and ordinal data, with a set significance value of P < 0.05. Percentage agreements were calculated to supplement each statistical test. The mean of the validity, reliability, and feasibility percentage agreement scores was calculated for each indicator to provide a composite respondent agreement score.

The indicator scoring scales consisted of categorical, ordinal data. Scores were dichotomized into agree (valid/reliable/feasible) and disagree (not valid/reliable/feasible and undecided) for analysis. Ranked ordinal data were not dichotomized.

For binary scores, multiple generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used to assess the differently distributed responses sampled by group (i.e. the same respondents over two rounds) and to account for both random and fixed effects. Multiple GLMM regressions with a binomial distribution were run (see Supplementary Fig. S7 online); all included unique respondent number (UserID) as a random effect since the data were paired between rounds. Round was included as a fixed effect in each model, as were other variables (e.g. indicator, indicator type, response type, UserID) dependent on the question of interest.

Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient (α) test93 was employed to test group stability of respondents. For interpretation, a value of 0 indicates perfect disagreement whereas 1 indicates perfect agreement; a value of 0.667 or more permits (tentative) conclusions to be made94.

Agreement between raters on the ranking of the top ten animal- and environment-based indicators was assessed using Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W); a value of 0 indicates no agreement, less than or equal to 0.30 weak agreement, 0.31–0.50 moderate, 0.51–0.70 good, 0.71–0.99 strong, and 1 perfect agreement95.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The Roslin Institute is funded by a BBSRC Institute Strategic Program Grant BB/P013759/1. The first author carried out this project in part fulfilment of the MSc International Animal Welfare, Ethics and Law at the University of Edinburgh. The authors wish to thank Wendy Watson for providing study design refinement and Ivone Campos-Luna for providing valuable advice in undertaking a Delphi consultation process. We also would like to thank the participants of the pilot test and Rounds One and Two of the survey.

Author contributions

M.T. and M.L. conceived of, designed, and coordinated the study. M.T. carried out the data collection. M.T., F.L., and J.M. analysed the data. M.T., J.M. and M.L. interpreted the results. All authors drafted the initial manuscript and then reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to compliance with General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Melissa A. Truelove, Email: mtruelo@emory.edu

Matthew C. Leach, Email: matthew.leach@newcastle.ac.uk

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-77437-9.

References

- 1.Lankau EW, Turner PV, Mullan RJ, Galland GG. Use of nonhuman primates in research in North America. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2014;53(3):278–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Centre for the Replacement Refinement & Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs). Welfare assessment. Macaque Websitehttps://www.nc3rs.org.uk/macaques/welfare-assessment/ (2020).

- 3.Home Office. Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain 2018. Her Majesties Stationary Office, London, UKhttps://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835935/annual-statistics-scientific-procedures-living-animals-2018.pdf (2018).

- 4.National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs. Nonhuman Primate Evaluation and Analysis Part 1: Analysis of Future Demand and Supply. https://orip.nih.gov/nonhuman-primate-evaluation-and-analysis-part-1-analysis-future-demand-and-supply (2018).

- 5.United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Annual report animal usage by fiscal year [2018]: Total number of animals research facilities used for regulated activities. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_welfare/annual-reports/Annual-Report-Summaries-State-Pain-FY18.pdf (2020).

- 6.Friedman H, et al. The critical role of nonhuman primates in medical research. Pathog. Immun. 2017;2(3):352–365. doi: 10.20411/pai.v2i3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfensohn, S. & Honess, P. Primates: their characteristics and relationship with man in Handbook of Primate Husbandry and Welfare (eds. Wolfensohn, S. & Honess, P.) 1–13 (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2008).

- 8.Descovich KA, et al. Opportunities for refinement in neuroscience: Indicators of wellness and post-operative pain in laboratory macaques. Altex. 2019;36(4):535–554. doi: 10.14573/altex.1811061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poole T. Happy animals make good science. Lab. Anim. 1997;31(2):116–124. doi: 10.1258/002367797780600198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumans V. Science-based assessment of animal welfare: laboratory animals. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2005;24(2):503–513. doi: 10.20506/rst.24.2.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayne K, Würbel H. The impact of environmental enrichment on the outcome variability and scientific validity of laboratory animal studies. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2014;33(1):273–280. doi: 10.20506/rst.33.1.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannibal DL, Bliss-Moreau E, Vandeleest J, McCowan B, Capitanio J. Laboratory rhesus macaque social housing and social changes: implications for research. Am. J. Primatol. 2017;79(1):e22528. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchant-Forde JN. The science of animal behavior and welfare: challenges, opportunities, and global perspective. Front. Vet. Sci. 2015;2(16):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2015.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnsen PF, Johannesson T, Sandøe P. Assessment of farm animal welfare at herd level: many goals, many methods. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2001;51(S30):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mench JA. Assessing animal welfare at the farm and group level: a United States perspective. Anim. Welf. 2003;12(4):493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capdeville J, Veissier I. A method of assessing welfare in loose housed dairy cows at farm level, focusing on animal observations. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2001;51(S30):62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW) Statement on the use of animal-based measures to assess the welfare of animals. EFSA Journal 10(6), 2767 (2012).

- 18.Brambell, F.W.R. Report of the technical committee to enquire into the welfare of animals kept under intensive livestock husbandry systems. Command paper 2836, HMSO London. https://edepot.wur.nl/134379 (1965).

- 19.Dawkins MS. A user's guide to animal welfare science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006;21(2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spangenberg EM, Keeling LJ. Assessing the welfare of laboratory mice in their home environment using animal-based measures–a benchmarking tool. Lab. Anim. 2016;50(1):30–38. doi: 10.1177/0023677215577298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leach MC, Thornton PD, Main DCJ. Identification of appropriate measures for the assessment of laboratory mouse welfare. Anim. Welf. 2008;17(2):161–170. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campos-Luna I, Miller A, Beard A, Leach M. Validation of mouse welfare indicators: a Delphi consultation survey. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45810-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster J. The assessment and implementation of animal welfare: theory into practice. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2005;24(2):723–734. doi: 10.20506/rst.24.2.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Main DCJ, Webster AJF, Green LE. Animal welfare assessment in farm assurance schemes. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2010;51(S30):108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Main DCJ, et al. Best practice framework for animal welfare certification schemes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014;37(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemsworth PH, Mellor DJ, Cronin GM, Tilbrook AJ. Scientific assessment of animal welfare. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015;63(1):24–30. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2014.966167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welfare Quality Network. Assessment protocols. https://www.welfarequalitynetwork.net/en-us/reports/assessment-protocols/ (2018).

- 28.Widowski, T. The evaluation and promotion of well-being in farm animals and laboratory primates: Common problems in contemporary animal care in Well-being of Nonhuman Primates in Research (eds. Mench, J.A. & Krulisch, L.) 19–25 (Scientists Center for Animal Welfare, 1990).

- 29.Rennie AE, Buchanan-Smith HM. Refinement of the use of non-human primates in scientific research Part I: the influence of humans. Anim. Welf. 2006;15(3):203–213. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rennie AE, Buchanan-Smith HM. Refinement of the use of non-human primates in scientific research Part II: housing, husbandry and acquisition. Anim. Welf. 2006;15(3):215–238. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rennie AE, Buchanan-Smith HM. Refinement of the use of non-human primates in scientific research Part III: refinement of procedures. Anim. Welf. 2006;15(3):239–261. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perlman JE, et al. Implementing positive reinforcement animal training programs at primate laboratories. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012;137(3):114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prescott M, Buchanan-Smith H. Training laboratory-housed non-human primates, part I: a UK survey. Anim. Welf. 2007;16(1):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulip J, Zimmermann JB, Farningham D, Jackson A. An automated system for positive reinforcement training of group-housed macaque monkeys at breeding and research facilities. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2017;285:6–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutz C, Well A, Novak M. Stereotypic and self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques: a survey and retrospective analysis of environment and early experience. Am. J. Primatol. 2003;60(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novak MA. Self-injurious behavior in rhesus monkeys: new insights into its etiology, physiology, and treatment. Am. J. Primatol. 2003;59(1):3–19. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novak MA, Hamel AF, Kelly BJ, Dettmer AM, Meyer JS. Stress, the HPA axis, and nonhuman primate well-being: a review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013;143(2):135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tasker, L. Linking welfare and quality of scientific output in cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) used for regulatory toxicology. Doctoral dissertation, University of Stirling (2012).

- 39.Kirchner, M. & Bakker, J. Construction of an integrated welfare assessment system (MacWel) for Macaques (Macaca spp.) in human husbandry in Proceedings of the International Conference on Diseases of Zoo and Wild Animals 2015 (eds. Szentiks, C.A. & Schumann, A.) (Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, 2015).

- 40.Council of Europe . ETS 123: European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes. Council of Europe: Strasbourg, Germany; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waiblinger S, Knierim U, Winckler C. The development of an epidemiologically based on-farm welfare assessment system for use with dairy cows. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2001;51(S30):73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spoolder H, De Rosa G, Horning B, Waiblinger S, Wemelsfelder F. Integrating parameters to assess on-farm welfare. Anim. Welf. 2003;12(4):529–534. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velarde A, Dalmau A. Animal welfare assessment at slaughter in Europe: Moving from inputs to outputs. Meat Sci. 2012;92(3):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Botreau R, Veissier I, Perny P. Overall assessment of animal welfare: strategy adopted in Welfare Quality. Anim. Welf. 2009;18(4):363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holey EA, Feeley JL, Dixon J, Whittaker VJ. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007;7(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. 2007;12(10):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. 2011 Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2012;79(8):1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whaytt HR, Main DCJ, Green LE, Webster AJF. Animal-based measures for the assessment of welfare state of dairy cattle, pigs and laying hens: consensus of expert opinion. Anim. Welf. 2003;12(2):205–217. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Souza APO, Soriano VS, Schnaider MA, Rucinque D, Molento CFM. Development and refinement of three animal-based broiler chicken welfare indicators. Anim. Welf. 2018;27(3):263–274. doi: 10.7120/09627286.27.3.263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Mori B, et al. Scientific and ethical issues in exporting welfare findings to different animal subpopulations: the case of semi-captive elephants involved in animal-visitor interactions (AVI) in South Africa. Animals. 2019;9(10):831. doi: 10.3390/ani9100831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bacon H, Walters H, Vancia V, Connelly L, Waran N. Development of a robust canine welfare assessment protocol for use in dog (Canis familiaris) catch-neuter-return (CNR) programmes. Animals. 2019;9(8):564. doi: 10.3390/ani9080564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dajani JS, Sincoff MZ, Talley WK. Stability and agreement criteria for the termination of Delphi studies. Technol. Forecast Soc. Change. 1979;13(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/0040-1625(79)90007-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green, P.J. The content of a college-level outdoor leadership course. Presented at the Conference of the Northwest District Association for the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, Spokane, WA (1982).

- 55.Keeney, S., Hasson, F., & McKenna, H. Conducting the research using the Delphi technique in The Delphi technique in nursing and health research (eds. Keeney, S., Hasson, F., & McKenna, H.) 69–83 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

- 56.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevenson VD. Some initial methodological considerations in the development and design of Delphi surveys. Cardiff, UK: Low Carbon Research Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Temple D, Manteca X, Dalmau A, Velarde A. Assessment of test–retest reliability of animal-based measures on growing pig farms. Livest. Sci. 2013;151(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2012.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.NC3Rs. About macaques. Macaque websitehttps://www.nc3rs.org.uk/macaques/macaques/ (2020).

- 60.Baker KC, Dettmer AM. The well-being of laboratory non-human primates. Am. J. Primatol. 2017;79(1):e22520. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bayne K. Reliance on behavior as a metric of animal welfare. ALTEX Proc. 2012;1(12):461–463. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gottlieb DH, Capitanio JP, McCowan B. Risk factors for stereotypic behavior and self-biting in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): Animal's history, current environment, and personality. Am. J. Primatol. 2013;75(10):995–1008. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gottlieb DH, Maier A, Coleman K. Evaluation of environmental and intrinsic factors that contribute to stereotypic behavior in captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015;171:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lutz CK. A cross-species comparison of abnormal behavior in three species of singly-housed old world monkeys. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018;199:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Novak MA, et al. Assessing significant (> 30%) alopecia as a possible biomarker for stress in captive rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Am. J. Primatol. 2017;79(1):e22547. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whay HR, Leeb C, Main DCJ, Green LE, Webster AJF. Preliminary assessment of finishing pig welfare using animal-based measurements. Anim. Welf. 2007;16(2):209–211. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leach MC, Main DCJ. An assessment of laboratory mouse welfare in UK animal units. Anim. Welf. 2008;17(2):171–187. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weed JL, et al. Treatment of persistent self-injurious behavior in rhesus monkeys through socialization: a preliminary report. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2003;42(5):21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Symons FJ, Thompson A, Rodriguez MC. Self-injurious behavior and the efficacy of naltrexone treatment: a quantitative synthesis. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2004;10(3):193–200. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fontenot MB, et al. The effects of fluoxetine and buspirone on self-injurious and stereotypic behavior in adult male rhesus macaques. Comp. Med. 2005;55(1):67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiefenbacher S, et al. The efficacy of diazepam treatment for the management of acute wounding episodes in captive rhesus macaques. Comp. Med. 2005;55(4):387–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fontenot BM, Wilkes MN, Lynch CS. Effects of outdoor housing on self-injurious and stereotypic behavior in adult male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2006;45(5):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rommeck I, Anderson K, Heagerty A, Cameron A, McCowan B. Risk factors and remediation of self-injurious and self-abuse behavior in rhesus macaques. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2009;12(1):61–72. doi: 10.1080/10888700802536798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kempf DJ, et al. Effects of extended-release injectable naltrexone on self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Comp. Med. 2012;62(3):209–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DiVincenti L, Jr, Wyatt JD. Pair housing of macaques in research facilities: a science-based review of benefits and risks. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2011;50(6):856–863. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baker KC, et al. Benefits of pair housing are consistent across a diverse population of rhesus macaques. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012;137(3):148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Truelove MA, Martin AL, Perlman JE, Wood JS, Bloomsmith MA. Pair housing of Macaques: a review of partner selection, introduction techniques, monitoring for compatibility, and methods for long-term maintenance of pairs. Am. J. Primatol. 2017;79(1):e22485. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Worlein JM, et al. Socialization in pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) Am. J. Primatol. 2017;79(1):e22556. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Whitham JC, Wielebnowski N. Animal-based welfare monitoring: using keeper ratings as an assessment tool. Zoo Biol. 2009;28(6):545–560. doi: 10.1002/zoo.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phythian CJ, et al. Validating indicators of sheep welfare through a consensus of expert opinion. Animal. 2011;5(6):943–952. doi: 10.1017/S1751731110002594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tuyttens FAM, et al. Observer bias in animal behaviour research: can we believe what we score, if we score what we believe? Anim. Behav. 2014;90:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meagher RK. Observer ratings: validity and value as a tool for animal welfare research. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009;119(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2009.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Knierim U, Winckler C. On-farm welfare assessment in cattle: validity, reliability and feasibility issues and future perspectives with special regard to the Welfare Quality approach. Anim. Welf. 2009;18(4):451–458. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brenninkmeyer C, et al. Reliability of a subjective lameness scoring system for dairy cows. Anim. Welf. 2007;16(2):127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Honess PE, Gimple JL, Wolfensohn SE, Mason GJ. Alopecia scoring: The quantitative assessment of hair loss in captive macaques. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2005;33(3):193–206. doi: 10.1177/026119290503300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bellanca RU, et al. A simple alopecia scoring system for use in colony management of laboratory-housed primates. J. Med. Primatol. 2014;43(3):153–161. doi: 10.1111/jmp.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clingerman KJ, Summers L. Development of a body condition scoring system for nonhuman primates using Macaca mulatta as a model. Lab. Anim. 2005;34(5):31–36. doi: 10.1038/laban0505-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clingerman KJ, Summers L. Validation of a body condition scoring system in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): inter-and intrarater variability. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2012;51(1):31–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kagan R, Carter S, Allard S. A universal animal welfare framework for zoos. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2015;18(sup1):S1–S10. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2015.1075830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sumison T. The Delphi technique: an adaptive research tool. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 1998;61(4):153–156. doi: 10.1177/030802269806100403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iqbal S, Pipon-Young L. The Delphi method. Psychologist. 2009;22(7):598–601. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Katz, H. Global surveys or multi-national surveys? On sampling for global surveys. Globalization and Social Science Data Workshop UCSB. https://www.global.ucsb.edu/orfaleacenter/conferences/ngoconference/Katz_for-UCSB-data-workshop.pdf (2006).

- 93.Hayes AF, Krippendorff K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun. Methods Meas. 2007;1(1):77–89. doi: 10.1080/19312450709336664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Krippendorff K. Reliability in content analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004;30(3):411–433. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cafiso S, Di Graziano A, Pappalardo G. Using the Delphi method to evaluate opinions of public transport managers on bus safety. Saf. Sci. 2011;57:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2013.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to compliance with General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.