Abstract

Here, we demonstrate the in vivo efficacy of glucose microparticles (GMPs) to serve as porogens within calcium phosphate cements (CPCs) to obtain a fast-degrading bone substitute material. Composites were fabricated incorporating 20 wt% GMPs at two different GMP size ranges (100-150 μm (GMP-S) and 150-300μm (GMP-L)), while CPC containing 20 wt% poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles (PLGA) and plain CPC served as controls. After 2 and 8 weeks implantation in a rat femoral condyle defect model, specimens were retrieved and analyzed for material degradation and bone formation. Histologically, no adverse tissue response to any of the CPC-formulations was observed. All CPC-porogen formulations showed faster degradation compared to plain CPC control, but only GMP-containing formulations showed higher amounts of new bone formation compared to plain CPC controls. After 8 weeks, only CPC-porogen formulations with GMP-S or PLGA porogens showed higher degradation compared to plain CPC controls. Overall, the inclusion of GMPs into CPCs resulted in a macroporous structure that initially accelerated the generation of new bone. These findings highlight the efficacy of a novel approach that leverages simple porogen properties to generate porous CPCs with distinct degradation and bone regeneration profiles.

Keywords: calcium phosphate cements, porogens, degradation, bone regeneration

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Pathologies such as trauma, post-traumatic complications, congenital defects, or tumor resection commonly result in extensive loss of bone tissue and the formation of a critical size defect unable to heal.[1] These critical size bone defects require bone grafting to aid in bone regeneration or augmentation. Currently, autologous bone grafting is the gold standard and the second most commonly transplanted tissue in the United States, with more than half a million procedures annually. [2-6] Autologous bone grafts have been shown to be osteoinductive, osteoconductive, as well as osteogenic.[7] Yet, patients may present with donor site morbidity at the harvesting location, and treatments involving autologous bone transplantation are limited by the volume of available donor tissue.[8] Given these drawbacks, a clinical need to develop new treatment strategies that facilitate bone regeneration is apparent. Toward this end, the development of synthetic biomaterials for bone graft applications has been a focal point for researchers over the recent decades. Specifically, calcium phosphate (CaP) based ceramics have been widely used in the fields of orthopedic surgery, oral-maxillofacial surgery, and dentistry, since the CaP phase hydroxyapatite is the main inorganic component of bone extracellular matrix.[9] In the clinical setting, CaP biomaterials are available in several different configurations, including dense blocks, granules, and cements.[10-12]

Due to a small intrinsic pore size (1-15 μm) within calcium phosphate cements (CPCs), bone tissue growth is limited to the surface of the cement and is unable to penetrate into the internal architecture of the cement.[13] Macroporosity, defined as porosity of pores larger than 100 μm, can be introduced within CPCs to increase surface area, thus fostering the active degradation of CPCs.[14] Particularly when macropores form an interconnected porous network, cells can penetrate into the internal structure of the cement and promote angiogenesis.[15] Several techniques have been explored for the creation of interconnected macropores, including the addition of foaming agents, the introduction of biodegradable microspheres, and water-soluble crystals.[14, 16-19] Specifically, several in vivo studies demonstrated the utility of leveraging poly(lactic-co-glycolic-acid) (PLGA) porogens for enhanced bone regeneration [14, 20-23], with almost full material degradation and bone replacement after 26 weeks of implantation in a rabbit femoral condyle bone defect.[24] However, the hydrolytic degradation of PLGA results in a delayed onset of CPC erosion that is highly dependent on several factors such as the molecular weight, copolymer ratio, and particle size.[25] Ideally, the rate of CPC degradation and new bone formation should approximately match. As such, the infiltration of cells, blood vessels, and ultimately bone tissue could be constrained by the degradation rate of the porogen. In order to overcome this challenge, one could incorporate a porogen with an earlier onset of degradation or dissolution. Previously, we demonstrated the feasibility of fabricating an injectable CPC in which glucose microparticles (GMPs) served as a porogen.[26] In that study, it was observed that by altering the weight fraction and size of GMPs one could control the porosity and degradability of GMP/CPC composites. Furthermore, GMPs were completely dissolved within 3 days of incubation in phosphate-buffered saline, resulting in an interconnected, macroporous CPC.[26]

In this study we evaluated the efficacy of GMPs as a fast-acting porogen for CPCs in vivo. We hypothesized that incorporation of GMPs would rapidly generate a macroporous CPC composite after GMP dissolution without an adverse tissue response. Furthermore, we hypothesized that CPC-GMP formulations would show an early onset of CPC degradation in contrast to the delayed onset of CPC-PLGA degradation. Consequently, the fast dissolution of GMPs would promote early bone tissue ingrowth into the scaffold. Regarding particle size, we hypothesized that small GMPs would show enhanced material degradation and bone formation compared to large GMPs due to the relatively increased surface area that forms upon porogen dissolution. Formulations were implanted as pre-set samples in a rat femoral bone defect for screening purposes of the newly developed experimental CPC-GMP composites. Histological and histomorphometric analyses for material degradation and newly formed bone were performed after 2 and 8 weeks of implantation to cover the differential degradation times of formulations with (early) GMP and (late) PLGA porogens.

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of CPC-porogen formulations

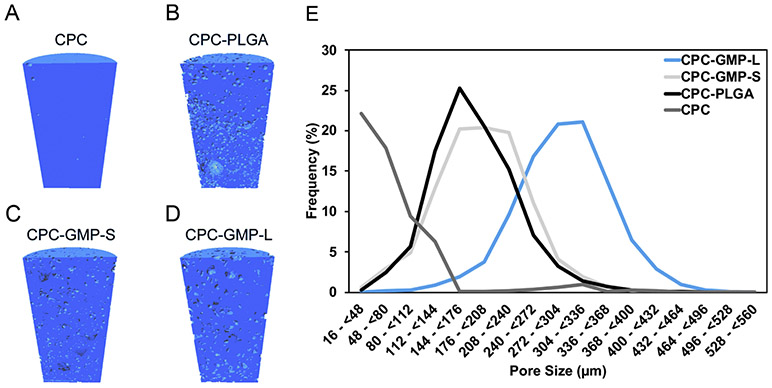

Figure 1 A-D shows representative longitudinal cross-sectional micro-CT images of the pre-implanted composites. The incorporation of GMPs resulted in a homogenous pore distribution. In addition, larger pores can be observed in composites that included GMPs compared to composites that incorporated PLGA MPs. As shown in Figure 1E, the addition of 20 wt% GMP-S resulted in the majority of the pores being between 112-304 μm. While the addition of GMP-L resulted in the majority of pores being between 240-400 μm. In addition, the incorporation of PLGA MPs created a majority of pores between 112-272 μm. On the contrary, the majority of the pores in the CPC control were not large enough to be considered macropores (>100 μm).

Figure 1.

Representative longitudinal cross-sectional images of the implanted cylindrical (2.5 mm in Ø, 5.0 mm in length) composites, generated by Micro-CT; CPC-GMP-L (A); CPC-GMP-S (B); CPC-PLGA (C); CPC (D). Pore size distributions from representative sections of the composites (E).

2.2. Descriptive light microscopy

The surgical procedure was uneventful for all animals. Animals regained mobility within one day after surgery. During the course of the experiment, no signs of inflammation or adverse tissue responses at the surgical site were observed. At each time point (i.e. 2 and 8 weeks), 18 rats were euthanized, from which 72 total specimens were retrieved. A total of 10 samples were excluded from the study, 5 due to inferior staining quality and 5 samples were excluded due to the quality of the implanted scaffold (i.e. cracks in the scaffold). An overview of the number of implants placed, retrieved and analyzed is presented in Table S2.

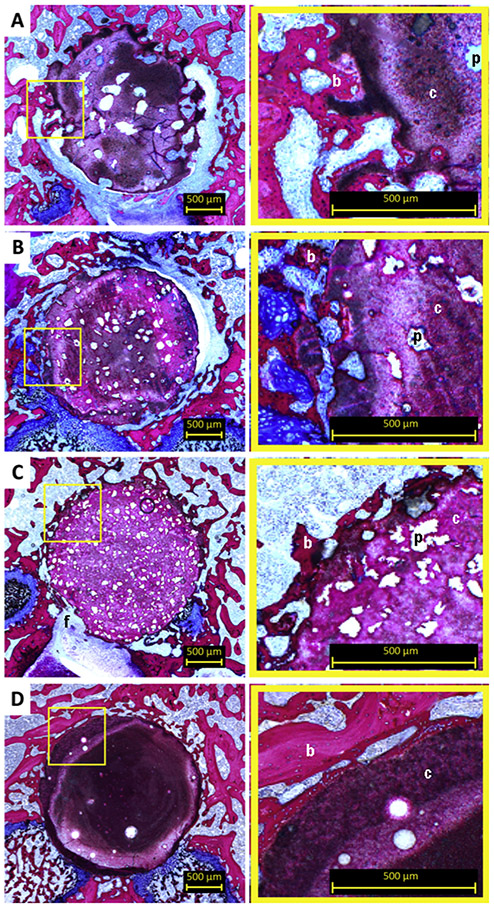

2.2.1. 2-week implantation period

Light microscopic evaluation revealed that after 2 weeks all implants maintained their integrity (Figure 2) and there was no sign of an adverse tissue response. Irregularly formed pores (indicated by ‘p’ in Figure 2) were observed within both CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S. Both CPC-GMP implants showed a porous structure at the surface of the implant. This observation was more apparent for CPC-GMP-L than for CPC-GMP-S. Pores of CPC-GMP-L were observed adjacent to the implant border. Newly formed bone (indicated by ‘b’ in Figure 2) was observed in the pores of CPC-GMP-L and in the smaller pores of CPC-GMP-S adjacent to the perimeter of the implant (magnifications Figure 2A and 2B, respectively). A homogeneous pore distribution was observed for CPC-PLGA. Borders of CPC-PLGA implants were clearly distinguishable. A line of newly formed bone adjacent to the original border of the implants was observed for CPC-GMP-L, CPC-GMP-S, and CPC-PLGA for the samples in which the borders were in close contact to the original bone tissue (magnifications Figure 2A, 2B, and 2C, respectively). A fibrous tissue layer (indicated by ‘f’ in Figure 2) was observed in between the bone and the CPC for few implants of each group where the scaffolds did not exhibit adequate contact with the bone. No material degradation was observed for CPC (Figure 2D). Light microscopic analysis revealed that bone was in direct contact with the CPC surface. At some locations, trabecular voids were observed, including bone marrow (magnification Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Histological overview and magnifications of CPC formulations implanted in a rat femoral bone defect at 2 weeks. Pores resulting from GMP-L (A), GMP-S (B) and PLGA MPs (C) can be discriminated based on size differences. Smaller pores showed a more homogenous pore distribution. Limited tissue infiltration in peripheral pores was apparent for CPC-GMP-L (magnification A). Pure CPC (D) showed no material degradation. Bone guided over the surface of the CPC was observed (magnification of 2D). p, pore; b, bone; c, cement; f, fibrous tissue.

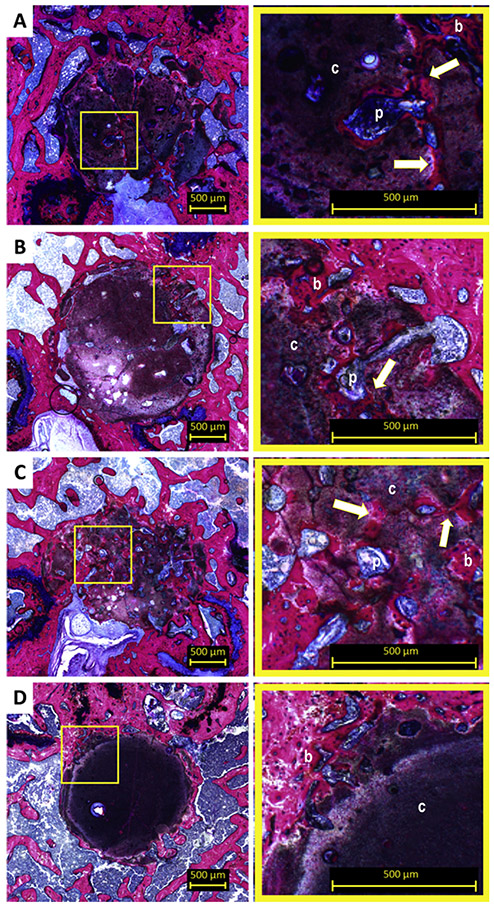

2.2.2. 8-week implantation period

Light microscopic evaluation revealed that 8 weeks after implantation, CPC-GMP-L, and CPC-PLGA showed substantial material degradation toward the center of the implant (Figure 3A and 3C, respectively). For CPC-GMP-S, material degradation towards the center of the implant was observed in a lesser extent (Figure 3B). The original borders of the CPC-GMP implants and CPC-PLGA implants were not clearly distinguishable. Newly formed bone (indicated by ‘b’ in Figure 3) was present in the ROI in areas where the material had degraded and in the macropores within material remnants. For CPC-PLGA, increased pore size (indicated by ‘p’ in Figure 3) was observed compared to 2 weeks of implantation and interconnection (indicated with arrow in Figure 3C) between macropores was observed. Furthermore, the newly formed bone was observed in the interconnected structure of macropores present in the remnants of the CPC-PLGA implants (magnification Figure 3C). For CPC, limited material degradation was observed solely at the periphery of the implant (Figure 3D). However, newly formed bone was observed at the periphery of the implant, within the ROI (magnification Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Histological overview and magnifications of CPC formulations implanted in a rat femoral bone defect at 8 weeks. At 8 weeks, CPC-GMP-L (A) and CPC-GMP-S (B) showed further degradation. Bone ingrowth in the pores was observed (magnifications A and B). Significant degradation of CPC-PLGA (C) and a newly formed bone network within the porous structure was observed (magnification C). Pure CPC solely showed degradation at the periphery of the CPC (D). p, pore; b, bone; c, cement; arrow, interconnection of pores.

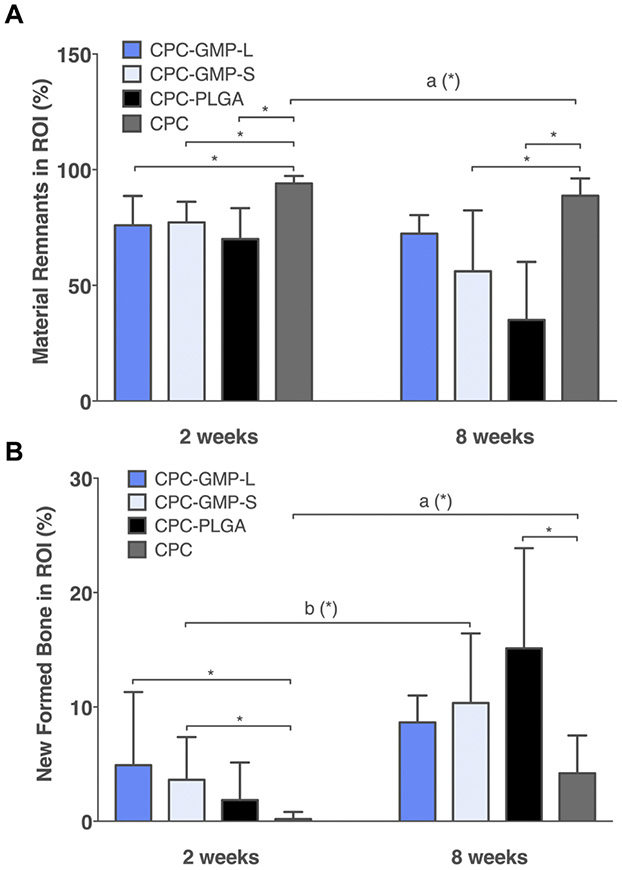

2.3. Histomorphometry

2.3.1. Material degradation

Histomorphometric results concerning material degradation are presented in Figure 4A. After 2 weeks of implantation, CPC-GMP-L, CPC-GMP-S, and CPC-PLGA all showed significantly lower material remnant values compared to CPC (p < 0.05). After 8 weeks of implantation, CPC-GMP-S and CPC-PLGA showed significantly lower material remnant values compared to CPC (p < 0.05). No significant difference in material remnant values was detected for CPC-GMP-L compared to CPC (p > 0.05). Material remnant values were similar for CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S (p > 0.05). CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S showed similar material remnant values at the 8 weeks time point compared to the 2 weeks time point (p > 0.05). CPC-PLGA showed significantly lower material remnant values at 8 weeks compared to 2 weeks (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Histomorphometric quantification of material remnants (A) and newly formed bone (B) in the region of interest (ROI) for CPC-GMP-L, CPC-GMP-S, CPC-PLGA and CPC after 2 (n=6, n=7, n=6, and n=8, respectively) and 8 weeks (n=7, n=6, n=7 and n=7, respectively) of implantation in a rat femoral bone defect (error bars represent standard deviation (SD); *p < 0.05, indicate significance of the CPC-porogen formulations in comparison to CPC; a, b indicate significant temporal changes of the individual experimental groups). In both panels error bars represent the standard deviation.

2.3.2. Bone formation

Histomorphometric results concerning new bone formation are presented in Figure 4B. At 2 weeks, CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S showed a higher amount of newly formed bone compared to CPC (p < 0.05 for both CPC-GMP formulations), while CPC-PLGA showed a similar amount of newly formed bone compared to CPC (p > 0.05). In addition, the amount of newly formed bone was similar for CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S (p > 0.05). At 8 weeks, CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S showed similar amounts of newly formed bone compared to CPC (p > 0.05). CPC-PLGA showed a significantly higher amount of newly formed bone compared to CPC (p < 0.05). The amount of newly formed bone was similar for CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S (p > 0.05). CPC-GMP-S and CPC-PLGA showed significantly higher amounts of newly formed bone at the 8 weeks time point compared to the 2 weeks time point (p < 0.05), while CPC-GMP-L showed similar amounts of newly formed bone at 8 and 2 weeks (p > 0.05).

3. Discussion

We determined the efficacy of glucose microparticles (GMPs) as a fast-acting porogen for calcium phosphate cements (CPCs) in vivo. Due to the high solubility of GMPs, we hypothesized that their incorporation would rapidly generate a macroporous CPC matrix without adverse tissue responses to allow for early bone ingrowth and acceleration of CPC degradation compared to both (i) CPC controls, and (ii) PLGA porogens with delayed hydrolytic degradation. Additionally, we hypothesized that GMP size would affect in vivo degradation with accelerated CPC degradation for composites with smaller GMPs due to increase CPC surface area after dissolution of GMPs. Histomorphometric analysis indeed revealed significantly higher bone formation for CPC-GMP formulations after 2 weeks, irrespective of GMP size, whereas CPC-PLGA did not. After 8 weeks, both small GMPs and PLGA MPs showed significantly increased material degradation, and only CPC-PLGA showed significantly higher bone formation compared to CPC controls.

PLGA degrades in the presence of water, by means of hydrolysis of the ester linkages within PLGA.[28] Upon hydrolysis, the degradation products of PLGA (i.e. lactic and glycolic acid) create an acidic environment. While the acidification itself accelerates the passive resorption of CPC, osteoclastic dependent active resorption of CPCs is equally important.[29, 30] It has been reported that osteoclastic activity can be stimulated under acidic conditions.[28, 31, 32] This indicates a beneficial role of active resorption besides passive resorption in the degradation of PLGA and CPC-PLGA composites. The degradation process of PLGA MPs over time has been extensively explored and depends on several factors such as: (i) end-group functionalization; (ii) molecular weight and; (iii) copolymer composition.[41] Studies reported initial pore formation due to partial PLGA degradation after approximately 2 weeks and complete PLGA degradation within approximately 8 weeks of implantation.[33, 34] CPC-PLGA material degradation was thus not expected to be significantly different compared to full CPC after 2 weeks of implantation, although results after a prolonged implantation period (i.e. 8 weeks) corroborated results reported previously.[28, 35, 36] It should be noted that the histological methods used in here allow for quantification of CPC remnants but cannot differentiate between partially and fully degraded PLGA MPs. GMPs on the other hand, disappear out of CPC by means of dissolution, which is a passive resorption process. The dissolution time of carbohydrate porogens could be extended by cooling of the liquid phase or the use of frozen carbohydrate microparticles. This ensures the presence of the carbohydrate porogen after CPC setting.[19, 26] The process of GMP dissolution will thus start when interstitial fluids reach the GMPs present in the CPC. Prior research showed that increased levels of glucose stimulate osteoclastic activity.[37, 38] As such, the local increase in glucose concentration after GMP dissolution likely stimulates active, osteoclastic-dependent CPC degradation. Considering complete dissolution of GMPs in the first two weeks of implantation and disappearance of the majority of precipitated glucose from the CPC within 3 days after incubation in PBS at 37 °C, glucose solely had an effect on active material degradation from zero to 2 weeks of implantation.[26] These results corroborate prior research that has investigated the ability to use glucono-delta-lactone (GDL) as a porogen within CPCs.[39] The hydrolysis of GDL into gluconic acid occurs within a day, creating macropores within the CPC.[39] Histomorphometric evaluation after 2 weeks of implantation in a rabbit condyle defect revealed that CPCs containing 10 wt% GDL not only degraded faster but also evoked higher bone formation compared to CPCs that incorporated PLGA or gelatin porogens.[39] Here, an implantation period of 2 weeks was based on previous research on the dissolution of GMPs in PBS and considered adequate to observe dissolution of GMPs, early onset of CPC degradation, and differences in the initial performance of CPC-GMP versus CPC-PLGA formulations. An implantation period of 8 weeks was deemed to be sufficient to observe PLGA degradation and concomitant CPC degradation, since multiple studies showed the degradation of PLGA takes several weeks.[26, 28, 36]

The incorporation of small GMPs significantly increased material degradation after 8 weeks compared to the CPC control. However, material degradation and new bone formation were similar for CPC-GMP-L and CPC-GMP-S at both time points. In addition, groups that had small GMPs showed a significant temporal increase in bone formation between 2 and 8 weeks. In the scientific community, a consensus on the optimum macropore size that maximizes bone growth has yet to be reached. As such, several studies have investigated the effect of macropore size on the resorption rate of CPCs.[40-43] Galois et al. investigated the effect of four different pore sizes in CPCs on bone regeneration in a femoral condyle defect of rabbits and concluded that a pore size above 80 μm is recommended to accelerate bone ingrowth.[41] Furthermore, no statistical difference in bone regeneration was observed between the pores sizes of 80-140, 140-200, and 200-250 μm, suggesting that the optimal pore size could be between the intervals of 80-250 μm.[41] In contrast, Unchida et al. investigated the efficacy of two different interconnected pore size ranges (150-210 μm and 210-300 μm) on bone growth. In this study, there was not an observable effect of pore size on bone regeneration.[40] To explain these contradictory results, Bohner et al. developed a resorption model which predicted that as the fraction of porogens decreases so does the effect of macropore size on bone ingrowth.[44] In the model, it was hypothesized that if the porosity of the structure is less than a minimum value the pores are not interconnected and thus cannot enable bone ingrowth. In the present study, the fraction of porogens was maximized to 20 wt%. As such, this explains why there was no observable effect between the two different size fractions of GMPs. Lopez-Heredia et al., observed that general porosity of CPC would be increased by the use of smaller particles, generating faster resorption.[45] Furthermore, they noted that smaller particles require a higher loading concentration compared to large particles in order to maintain the desired interconnectivity.

The CPC-formulations evaluated here each have a different relationship with physiological bone remodeling: the necessity for active material resorption is apparent for pure CPC, while CPC-formulations with porogens each aid in material degradation in a distinct manner depending on the porogen properties. Pure CPC resembles the mineral phase of bone tissue after transition of the crystal phase upon contact with aqueous solutions [46], but as a bulk material with intrinsic porosity of subcellular dimension. In contrast, CPC-formulations with porogens represent large, microscale pores within the same bulk material after degradation of the porogens. This increases the surface area of the material for passive and active degradation. Only PLGA porogens have an additional effect on the CPC-matrix degradation due to the acidic degradation products of PLGA and their local interaction with(in) the bulk material [14]. The data obtained here are in accordance with the anticipated regenerative properties of the different formulations, showing hardly any regeneration for pure CPC, moderate regeneration for CPC-GMP, and substantial regeneration for CPC-PLGA.

We envision GMPs could be combined with porogens with a later onset of forming a macroporous structure, such as PLGA, to enhance the generation of bone. The ultimate goals of these multimodal porogen composites are the gradual replacement of the CPC by newly formed bone and enabling this process to start directly after implantation in a bone defect. An injectable, multimodal porogen platform CPC comprising these beneficial characteristics will be of high interest for clinical application in the field of non-load bearing bone regenerative medicine.

4. Conclusion

In the present study, the in vivo efficacy of GMPs as a porogen within CPCs was investigated. For the duration of the study no adverse tissue response was observed due to the incorporation of GMPs. Specifically, it was observed that in as little as 2 weeks CPC-GMP formulations accelerated material degradation and bone formation in a rat femoral bone defect model compared to CPC controls. Most notably, implants that incorporated smaller GMPs significantly increased the amount of bone formed after 2 weeks compared to plain CPC controls, while there was no observable difference between implants that incorporated PLGA MPs and CPC controls. These findings highlight the efficacy of a novel approach that leverages simple porogen properties to generate porous CPCs with distinct degradation and bone regeneration profiles.

5. Experimental Section

Preparation of CPC porogen formulations and scaffolds:

Scaffolds were fabricated as previously described.[26] Briefly, GMPs (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or PLGA MPs (sieved between 50-100 μm, acid terminated, lactic:glycolic acid ratio (L:G) = 50:50, generously supplied by Purac (Gorinchem, Netherlands)) were added to CPC powder (100% αTCP, kindly provided by CAM Bioceramics B. V. (Leiden, the Netherlands)) following the experimental groups outline in Table S1.A solution of 24 wt% Na2HPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) saturated in glucose (saturated liquid, 0.909 g/mL) was then added at a liquid/powder ratio of 0.53 and vigorously shaken for 25 s. The resulting cement paste was injected into Teflon molds (2.5 mm diameter, 5 mm high), left to set at room temperature for 24 h, and the formed constructs were stored in a lyophilizer. To analyze the porosity and pore distribution, constructs (n=3) were scanned by microcomputed tomography (micro-CT, Skyscan 1272, Aartselaar, Belgium) at a resolution of 12 μm/pixel. Raw images were reconstructed in NReconn and analyzed in CTan (SkyScan, Aartselaar, Belgium) using a region of interest that was 2 mm in diameter and 3 mm tall. Finally, all samples were sterilized by gamma irradiation at a minimum dose of 25kGy (Synergy Health Ede, B. V., Ede, the Netherlands).

Animal model and surgical procedure:

Thirty two skeletally mature, male, Wistar rats with weights ranging from 200 to 250 grams were used as experimental animals (n=8 per experimental group, per time point). The animals were housed at the Central Animal Laboratory (Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands) with respect to the national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals, following the guidelines of the 2010/63/EU directive. The study was reviewed and approved in advance by the Centrale Commissie Dierproeven (CCD; Central Commission for Animal Experiments; CCD number AVD103002015227). Surgery was performed according to the procedure described previously by our laboratory.[27] The rats underwent a one session surgical procedure under general inhalation anesthesia induced by and maintained with a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen through a constant volume ventilator. The surgical sites were shaved and disinfected with povidone iodine, followed by a sterile dressing. A longitudinal incision was made medially from the patella. Subsequently, the distal femur was made visual by lateralizing the patella (Figure S1A). The periosteum was bluntly dissected of the femoral bone. Bone defects were created in the longitudinal direction of the bone using a dental drill (Figure S1B), increasing the diameter of the bur until a defect of 2.5 mm in diameter and 5 mm in depth was reached (Figure S1C). Pre set cement samples were placed into the bone defects (Figure S1D). Subcutaneous tissue was closed with resorbable sutures (Vicryl 4.0, Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey, USA). The skin was closed with surgical staples. Materials were allocated over the 64 defects through randomization with respect to the fact that the right and left femur would contain different experimental materials. Carprofen (Rimadyl®, Zoetis B.V., Capelle aan de IJssel, the Netherlands) was administered before surgery and for 3 days post-surgery to reduce post operative pain and inflammatory response. After either 2 or 8 weeks, animals were euthanized by an overdose of CO2, the femora were retrieved, the excess soft tissue was removed, and the excess bone was cut off with a diamond blade saw.

Histological procedures:

Specimens were fixed in 4% phosphate buffered formaldehyde solution (pH 7.2), dehydrated in graded series of ethanol concentrations (70-100%) and finally embedded in poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). Thin sections of 10 μm in thickness were prepared in a cross sectional direction perpendicular to the longitudinal direction of the bone defect using a saw microtome with a diamond blade (Leica SP 1600, Leica Biosystems Nussloch GmbH, Nussloch, Germany). The sections were stained with methylene blue and basic fuchsine to stain bone tissue, CPC, and fibrous tissue.

Histological and histomorphometric analysis:

Histological evaluation (n ≥ 3) was performed using a light microscope (Leica Microsystems AG, Wetzlar, Germany). Histomorphometric analysis was performed by quantifying the amount of material remaining or newly formed bone within the region of interest (ROI) in each of the sections. To this end, a circular ROI of 2.45 mm in diameter was imposed on the histological image and centered in the middle of bone defect (Figure S2). The relative area of material remnants and bone tissue (based on staining and morphology) was quantified using image analysis software (ImageJ2, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). The percentage of material remaining and newly formed bone was calculated by taking the respective area measured by ImageJ and dividing it by the ROI area. Next, the percentage of material remnants and percentage of newly formed bone were compared at both time points.

Statistical analyses:

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Sample size varied per experimental group. Table S2 shows an overview of the sample size per implantation period.

A Kruskal Wallis test with a Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used to identify significant differences among CPC GMP L, CPC GMP S, CPC PLGA, and CPC. A Mann Whitney test was used to determine significant differences from 2 to 8 weeks within each experimental group. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Tailoring degradation and bone regeneration using distinct CPC-porogen formulations is feasible using different porogens. Depending on chemical properties and size, their incorporation into CPC results in control over material degradation and bone regeneration. The CPC-porogen formulations can be used for bone regenerative applications.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Army, Navy, NIH, Air Force, VA and Health Affairs to support the AFIRM II effort, under Award No. W81XWH-14-2-0004. The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. B.T.S. received support from Ruth L. Kirschstein Fellowships from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (F30 AR071258). B.T.S acknowledges the Baylor College of Medicine Medical Scientist Training Program. E-C.G. and B.T.S. contributed equally to this work.

Data availability:

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Calori GM, Mazza E, Colombo M, Ripamonti C, The use of bone-graft substitutes in large bone defects: Any specific needs?, Injury, Int. J. Care Injured 42 (2011) S56–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Campana V, Milano G, Pagano E, Barba M, Cicione C, Salonna G, Lattanzi W, Logroscino G, Bone substitutes in orthopaedic surgery: from basic science to clinical practice, Journal of materials science. Materials in medicine 25(10) (2014) 2445–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Greenwald AS, Boden SD, Goldberg VM, Khan Y, Laurencin CT, Rosier RN, Bone-graft substitutes: facts, fictions, and applications, J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A Suppl 2 Pt 2 (2001) 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Finkemeier CG, Bone-grafting and bone-graft substitutes, J Bone Joint Surg Am 84-a(3) (2002) 454–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Van Heest A, Swiontkowski M, Bone-graft substitutes, Lancet (London, England) 353 Suppl 1 (1999) Si28–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Faour O, Dimitriou R, Cousins CA, Giannoudis PV, The use of bone graft substitutes in large cancellous voids: any specific needs?, Injury 42 Suppl 2 (2011) S87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pape HC, Evans A, Kobbe P, Autologous Bone Graft: Properties and Techniques, Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 24 (2010) S36–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sen M, Miclau T, Autologous iliac crest bone graft: should it still be the gold standard for treating nonunions?, Injury 38(1) (2007) S75–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goulet JA, Senunas LE, DeSilva GL, Greenfield MLV, Autogenous iliac crest bone graft: complications and functional assessment, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 339 (1997) 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schmitz JP, Hollinger JO, Milam SB, Reconstruction of bone using calcium phosphate bone cements: a critical review, Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 57(9) (1999) 1122–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dorozhkin SV, Calcium orthophosphates as bioceramics: state of the art, Journal of functional biomaterials 1(1) (2010) 22–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bohner M, Gbureck U, Barralet J, Technological issues for the development of more efficient calcium phosphate bone cements: a critical assessment, Biomaterials 26(33) (2005) 6423–6429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Del Valle S, Miño N, Muñoz F, González A, Planell JA, Ginebra M-P, In vivo evaluation of an injectable macroporous calcium phosphate cement, Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 18(2) (2007) 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lanao RPF, Leeuwenburgh SC, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Bone response to fast-degrading, injectable calcium phosphate cements containing PLGA microparticles, Biomaterials 32(34) (2011) 8839–8847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cama G, Calcium phosphate cements for bone regeneration, Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration, Elsevier; 2014, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Habraken W, Wolke J, Mikos A, Jansen J, PLGA microsphere/calcium phosphate cement composites for tissue engineering: in vitro release and degradation characteristics, Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 19(9) (2008) 1171–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Del Real R, Ooms E, Wolke J, Vallet - Regí M, Jansen J, In vivo bone response to porous calcium phosphate cement, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 65(1) (2003) 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bigi A, Bracci B, Panzavolta S, Effect of added gelatin on the properties of calcium phosphate cement, Biomaterials 25(14) (2004) 2893–2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lodoso - Torrecilla I, van Gestel NA, Diaz - Gomez L, Grosfeld EC, Laperre K, Wolke JG, Smith BT, Arts JJ, Mikos AG, Jansen JA, Multimodal pore formation in calcium phosphate cements, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 106(2) (2018) 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hoekstra JWM, Ma J, Plachokova AS, Bronkhorst EM, Bohner M, Pan J, Meijer GJ, Jansen JA, van den Beucken JJJP, The in vivo performance of CaP/PLGA composites with varied PLGA microsphere sizes and inorganic compositions, Acta Biomaterialia 9(7) (2013) 7518–7526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Link DP, van den Dolder J, van den Beucken JJ, Cuijpers VM, Wolke JG, Mikos AG, Jansen JA, Evaluation of the biocompatibility of calcium phosphate cement/PLGA microparticle composites, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 87(3) (2008) 760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liao H, Walboomers XF, Habraken WJEM, Zhang Z, Li Y, Grijpma DW, Mikos AG, Wolke JGC, Jansen JA, Injectable calcium phosphate cement with PLGA, gelatin and PTMC microspheres in a rabbit femoral defect, Acta Biomaterialia 7(4) (2011) 1752–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Link DP, Van den Dolder J, Jurgens WJ, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Mechanical evaluation of implanted calcium phosphate cement incorporated with PLGA microparticles, Biomaterials 27(28) (2006) 4941–4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Grosfeld EC, Hoekstra JW, Herber RP, Ulrich DJ, Jansen JA, van den Beucken JJ, Long-term biological performance of injectable and degradable calcium phosphate cement, Biomedical materials (Bristol, England) 12(1) (2016) 015009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Habraken WJ, Wolke JG, Mikos AG, Jansen JA, Injectable PLGA microsphere/calcium phosphate cements: physical properties and degradation characteristics, J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 17 (2006) 1057–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith BT, Santoro M, Grosfeld EC, Shah SR, van den Beucken JJ, Jansen JA, Mikos AG, Incorporation of fast dissolving glucose porogens into an injectable calcium phosphate cement for bone tissue engineering, Acta biomaterialia 50 (2017) 68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].van Houdt CI, Tim CR, Crovace MC, Zanotto ED, Peitl O, Ulrich DJ, Jansen JA, Parizotto NA, Renno AC, van den Beucken JJ, Bone regeneration and gene expression in bone defects under healthy and osteoporotic bone conditions using two commercially available bone graft substitutes, Biomedical Materials 10(3) (2015) 035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Felix Lanao RP, Leeuwenburgh SC, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Bone response to fast-degrading, injectable calcium phosphate cements containing PLGA microparticles, Biomaterials 32(34) (2011) 8839–8847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yuan H, Li Y, De Bruijn J, De Groot K, Zhang X, Tissue responses of calcium phosphate cement: a study in dogs, Biomaterials 21(12) (2000) 1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schilling AF, Linhart W, Filke S, Gebauer M, Schinke T, Rueger JM, Amling M, Resorbability of bone substitute biomaterials by human osteoclasts, Biomaterials 25(18) (2004) 3963–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pereverzev A, Komarova SV, Korcok J, Armstrong S, Tremblay GB, Dixon SJ, Sims SM, Extracellular acidification enhances osteoclast survival through an NFAT-independent, protein kinase C-dependent pathway, Bone 42(1) (2008) 150–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Arnett T, Regulation of bone cell function by acid-base balance, The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 62(2) (2003) 511–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hedberg EL, Kroese-Deutman HC, Shih CK, Crowther RS, Carney DH, Mikos AG, Jansen JA, In vivo degradation of porous poly(propylene fumarate)/poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid) composite scaffolds, Biomaterials 26(22) (2005) 4616–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liao H, Walboomers XF, Habraken WJ, Zhang Z, Li Y, Grijpma DW, Mikos AG, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Injectable calcium phosphate cement with PLGA, gelatin and PTMC microspheres in a rabbit femoral defect, Acta biomaterialia 7(4) (2011) 1752–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Renno AC, Nejadnik MR, van de Watering FC, Crovace MC, Zanotto ED, Hoefnagels JP, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, van den Beucken JJ, Incorporation of bioactive glass in calcium phosphate cement: material characterization and in vitro degradation, Journal of biomedical materials research. Part A 101(8) (2013) 2365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Felix Lanao RP, Sariibrahimoglu K, Wang H, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Leeuwenburgh SC, Accelerated calcium phosphate cement degradation due to incorporation of glucono-delta-lactone microparticles, Tissue Eng Part A 20(1-2) (2014) 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Williams JP, Blair HC, McDonald JM, McKenna MA, Jordan SE, Williford J, Hardy RW, Regulation of osteoclastic bone resorption by glucose, Biochemical and biophysical research communications 235(3) (1997) 646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ng KW, Regulation of glucose metabolism and the skeleton, Clinical endocrinology 75(2) (2011) 147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Félix Lanao RP, Sariibrahimoglu K, Wang H, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Leeuwenburgh SC, Accelerated calcium phosphate cement degradation due to incorporation of glucono-delta-lactone microparticles, Tissue Engineering Part A 20(1-2) (2013) 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Uchida A, Nade S, McCartney ER, Ching W, The use of ceramics for bone replacement. A comparative study of three different porous ceramics, Bone & Joint Journal 66(2) (1984) 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Galois L, Mainard D, Bone ingrowth into two porous ceramics with different pore sizes: an experimental study, Acta orthopaedica Belgica 70(6) (2004) 598–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].von Doernberg M-C, von Rechenberg B, Bohner M, Grünenfelder S, van Lenthe GH, Müller R, Gasser B, Mathys R, Baroud G, Auer J, In vivo behavior of calcium phosphate scaffolds with four different pore sizes, Biomaterials 27(30) (2006) 5186–5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Eggli P, Müller W, Schenk R, Porous hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate cylinders with two different pore size ranges implanted in the cancellous bone of rabbits. A comparative histomorphometric and histologic study of bony ingrowth and implant substitution, Clinical orthopaedics and related research (232) (1988) 127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bohner M, Baumgart F, Theoretical model to determine the effects of geometrical factors on the resorption of calcium phosphate bone substitutes, Biomaterials 25(17) (2004) 3569–3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lopez-Heredia MA, Sariibrahimoglu K, Yang W, Bohner M, Yamashita D, Kunstar A, van Apeldoorn AA, Bronkhorst EM, Felix Lanao RP, Leeuwenburgh SC, Itatani K, Yang F, Salmon P, Wolke JG, Jansen JA, Influence of the pore generator on the evolution of the mechanical properties and the porosity and interconnectivity of a calcium phosphate cement, Acta biomaterialia 8(1) (2012) 404–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lodoso-Torrecilla I, Grosfeld EC, Marra A, Smith BT, Mikos AG, Ulrich DJ, Jansen JA, van den Beucken JJ, Multimodal porogen platforms for calcium phosphate cement degradation, J Biomed Mater Res A. 107(8) (2019):1713–1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.