Abstract

Introduction

Pandemics are known to affect mental health of the general population and various at-risk groups like healthcare workers, students and people with chronic medical diseases. However, not much is known of the mental health of people with pre-existing mental illness during a pandemic. This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates, whether people with pre-existing mental illness experience an increase in mental health symptoms and experience more hospitalizations during a pandemic.

Materials and methods

A systematic search was conducted in the EMBASE, OVID-MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases to identify potentially eligible studies. Data were extracted independently and continuous data were used in calculating pooled effect sizes of standardized mean difference (SMD) using the random-effects model.

Results

Of 1791 records reviewed 15 studies were included. People with pre-existing mental illness have significantly higher psychiatric symptoms, anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms compared to controls during a pandemic with pooled effect sizes (SMD) of 0.593 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.46 to 0.72), 0.616 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.73) and 0.597 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.80) respectively. Studies also found a reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations and utilization of psychiatric services during pandemics.

Conclusion

The review highlights the need for mental health services to address the increased mental health symptoms in people with pre-existing mental illnesses during a pandemic. Future research should focus on better designed controlled studies of discrete illness groups, so as to provide a robust basis for policy makers to plan appropriate level of support and care for people with mental illness during a pandemic.

Keywords: Anxiety, COVID-19, Mental health, Pandemic, Review

Highlights

-

•

People with pre-existing mental illness are highly vulnerable during a pandemic.

-

•

They experience higher rates of psychiatric morbidity during the pandemic.

-

•

Anxiety symptoms were significantly higher with SMD of 0.616 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.73).

-

•

During pandemics psychiatric hospitalizations and utilization of services is reduced.

-

•

Need for longitudinal studies to understand impact of pandemic in mental illness.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines a pandemic as the worldwide spread of a new disease. COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV2 corona virus is the latest of several pandemics that the world has seen in the past century. It was officially classified as a pandemic by the WHO on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020a). As of November 9, 2020 over 50 million people have been infected and over 1.25 million people have died of the COVID-19 disease (WHO, 2020b). Most of the pandemics in the past 100 years have been caused by viral infections. These include the Influenza pandemics of 1918, 1957 and 2009, and the Corona virus pandemics of 2002, 2012 and 2019–20. The latter have been named SARS-CoV (Severe acute respiratory syndrome), MERS (Middle-East respiratory syndrome) and the SARS-CoV2 respectively.

Pandemics of infective diseases can adversely impact both the physical and mental health of the general population. Research suggests that the mental health impact is felt both during the pandemic and after it declines, and is commonly manifested as symptoms of stress, anxiety, fear, apprehension, excessive worry and depression (Rajkumar 2020; Vindegaard and Benros, 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020). There is also some evidence to suggest an increased occurrence of psychotic presentations during and soon after a pandemic (Brown et al., 2020).

However, there has been little research into how pandemics affect people with pre-existing mental illness. People with mental illness have a number of risk factors that render them vulnerable to adverse health outcomes. These range from poorer physical health, low levels of physical activities, higher rates of smoking, alcohol and substance misuse, and social & economic disadvantage (Rodgers et al., 2016; Leucht et al., 2007; Hert et al., 2011).

The situation for people with mental illness is made worse during pandemics as health care systems adjust to deal with the physical consequences of the pandemic itself. Routine care (including mental health care) is hampered and resources are diverted to support and limit the damage caused by the pandemic. Public health measures like travel bans, physical-distancing, self-isolation and quarantine further magnify the stress faced by people with mental illness. While there has been extensive work on the effect of past pandemics (and the current Covid-19) on the mental health of the general population, health care workers, infected persons and survivors, there has been little research on the impact of pandemics on people living with mental illness. A recent review described the impact of Covid-19 on new-onset psychosis rather than in people with pre-existing psychotic illnesses (Brown et al., 2020). A living systematic review by Thombs et al. is exploring the mental health impact of Covid-19 on the general population (Thombs et al., 2020). Another review explored the psychiatric and neuropsychiatric manifestations of Covid-19 disease (Rogers et al., 2020).

This paper is an attempt to synthesize available research on the effects of pandemics on the mental health of people with pre-existing mental illness. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing literature to answer the following questions:

-

a.

Do people with pre-existing mental illness experience an increase in mental health symptoms during a pandemic?

-

b.

Do people with pre-existing mental illness experience more hospitalizations during a pandemic?

It was felt important to answer these questions in order to better understand how pre-existing symptoms might be impacted by a pandemic.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

A search strategy was iteratively developed to identify studies that reported on the effects of a pandemic in people with mental illness. Unlike randomized controlled studies, the observational studies are not well indexed; therefore a search strategy was developed empirically by examining the indexing of author’s personal databases and early studies relating to the Covid-19 pandemic. The sensitivity of the search strategy was confirmed by checking the reference lists of relevant papers and ensuring no relevant paper was missed. The search was conducted in English-language databases of Ovid-Medline (including Epub, in-process & ahead of print), EMBASE and PSYCINFO using the OVID technologies (Table 1). The search was initially completed on May 2, 2020 with further updates on May 28, 2020 and finally on June 4, 2020. Further articles were added to the retrieval by scrutinizing the reference lists of relevant articles and recent reviews. This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) and Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) consensus statement (Stroup et al., 2000). The study protocol is available as supplementary material.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Search strategy | Database | Search fieldsa | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| ((“mental illness##" or “mental disorder#" or “mental health” or “severe mental” or “mental health condition#" or " (psychiatr## ADJ1 disorder#)" or " (psychiatr## ADJ1 illness##)" or " (mental## ADJ1 ill)" or " (mental## ADJ1 unwell)" or " (psychiatric ADJ1 patient)" or “schizophrenia” or “schizophrenic” or “psychosis” or “psychotic” or “bipolar” or “mania” or " (manic ADJ2 disorder#)" or “depression” or " (depressive ADJ1 disorder#)" or " (anxiety ADJ1 disorder#)" or " (neurotic ADJ1 disorder#)") and (“pandemic” or “covid-19″ or “covid” or " (coronavirus ADJ3 outbreak)" or " (sars ADJ3 outbreak)" or " (mers ADJ3 outbreak)" or " (swine flu ADJ3 outbreak)" or " (sars ADJ3 epidemic#)" or " (mers ADJ3 epidemic#)" or " (swine flu ADJ3 epidemic#)")). | EMBASE | ab,hw,kw,ot,sh,ti | 1006 |

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print. | ab,hw,kf,kw,ot,sh,ti | 621 | |

| APA Psychinfo | ab,hw,mh,ot,sh,ti | 160 |

ab-abstract, hw-heading word, kw – keyword heading, ot-original title, sh-subject heading, ti-title, kf-keyword, mh-MeSH word.

2.2. Study selection

NA and JN independently reviewed the final list of retrieved articles. Studies/articles meeting all the following five criteria were included:

-

a)

Study describing original data,

-

b)

Study providing description of participants with pre-existing mental illness with or without a control group

-

c)

Study exploring the psychiatric symptoms, and/or hospitalization,

-

d)

Study providing quantitative data including scores of rating scales or percentages and

-

e)

Study objective to assess the effects of a pandemic.

Studies were excluded if they were a) only describing mental health in people without mental illness, b) not assessing the effects of a known pandemic as recognized by WHO, c) not reporting any quantitative data, d) if they were editorials, letters, commentaries or reviews without describing any original data or a case report, or e) primarily describing impact of HIV or AIDS on mental illness. The meta-analysis only included controlled studies with means and standard deviations. Any disagreements or unclear studies were resolved with involvement of KN and VD.

2.3. Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by NA and JN from all included studies using a proforma. KN and VD were involved in resolving any disagreements in data extraction. The data extraction proforma included several items: study name, country of origin, type of pandemic, study design, description of participants and control group, type of mental illness, details of any rating scales, quantitative data in the form of means, sample size, standard deviations, percentages or prevalence rates or proportions. Findings from all included studies were used in the synthesis of the systematic review (Fig. 1) and all studies were subjected to a formal risk of bias assessment. Risk of Bias Assessment of Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS) was used to formally assess the Risk of Bias in included studies. The RoBANS is a domain-based evaluation tool that contains six domains: the selection of participants, confounding variables, the measurement of exposure, the blinding of the outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting rated for risk of bias as low, high or unclear (Kim et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

PRIMSA Flow diagram of review.

Mean scores, standard deviations and sample sizes were extracted from controlled studies that used a rating scale of psychiatric symptoms. Prevalence rates and proportions were extracted from cross-sectional studies that did not have a control group. Studies used different rating scales to assess mental health symptoms. If a study was found to be eligible but did not provide mean scale scores, KN contacted the authors of the study for the mean scores to include in the meta-analysis.

2.4. Data synthesis

The systematic review included a narrative synthesis from all included studies. The review describes the key study findings with a view to answer the review questions. The review describes the study design, type of mental disorders, pandemic type and critically evaluates the included original studies and builds evidence as to whether people with pre-existing mental illness have an increase in mental health symptoms or hospitalizations. The meta-analysis only included studies that allowed the appropriate data extraction. For the meta-analysis data were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2, a dedicated meta-analysis program (BioStat, Inc, Englewood, NJ). The analysis was based on included studies that provided mean scores, standard deviations and sample size. All authors of potentially eligible studies were contacted for confirming and/or providing break-down of required data for the review if not originally provided or unclear in the article.

As the purpose of the study is to examine if people with pre-existing mental illness experience increase in mental health symptoms we combined all reported mental health symptoms. This is to understand the magnitude of the impact on overall mental health of people with pre-existing mental illness during a pandemic. The analysis included all psychiatric symptoms (combined) and other predominant psychiatric symptom domains among studies that allowed pooling of rating scales under similar domain. For example, if studies assessed anxiety symptoms using a recognized anxiety symptom rating scale these were pooled together to calculate a pooled effect size on anxiety symptoms. Similarly if studies reported depressive symptoms using recognized depressive symptoms rating scale they were pooled together in the meta-analysis. This allowed categorizing the effects of pandemic on particular predominant symptom domains. This approach was considered to be of translational research value that would inform clinical services to plan effective use of resources during a pandemic. The effect size of standardized mean difference (SMD) was calculated across the studies using a random-effects model of analysis. The standardized mean difference (SMD) is a widely used measure of effect size and is defined as the difference in means between the two groups, standardized by dividing this by the with-in groups’ pooled standard deviation. The SMD effect size can be interpreted as the average percentile standing of the mean in the comparison group relative to the mean in the control group. Cohen defined a standardized mean difference of 0.2 as small, 0.5 as medium, and 0.8 as large (Cohen 1988).

Random-effects model was used for all analyses as the data were from different populations and from studies with different protocols based on the systematic review of literature. The random-effects model assumes the studies to have different levels of impact and considers the studies to be picked from several populations (Borenstein et al., 2010). Therefore, the effect size from random-effects model is applicable to the several populations of effect sizes. I-squared and p-value are reported to give an indication of heterogeneity between studies. Tau-squared is provided to give an estimate of variance in effect sizes between the studies. The impact of publication bias if any was assessed by calculating fail-safe number of studies needed to shift the significance level. Sensitivity analyses and sub-group analyses were carried out using a random-effects model to assess the impact of removing each one of the studies in calculating the pooled effect size and assessing the effects of country of origin, pandemic type and mean age. A meta-regression was conducted on mean age of participants.

3. Results

The systematic search identified 1791 articles. Duplicates were excluded and titles of the remaining articles were screened. Of these, 322 articles were felt to be relevant to the topic of interest, and their abstracts were further screened to ascertain whether they met the criteria for this review. Of these 237 articles were excluded, and the remaining 85 full text articles were reviewed. Fifteen studies were finally found to be eligible and Table 2 provides the description of the included studies (Lara et al., 2020; Berthelot et al., 2020; Clerici et al., 2020; Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020; Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., 2020; Goodman-Casanova et al., 2020; Hao et al., 2020; Iancu et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2020; Maguire et al. 2019; Ozdin and Ozdin, 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020; Van Der Heide and Coutinho 2006; Zhou et al., 2020; Pang and Tam, 2004).

Table 2.

Description of included studies.

| Study | Country | Pandemic | Type of study | Participants | Age |

Measure/Evaluation of mental health symptoms |

Summary of findings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric Patients | Control Group | Measuring Scales | Psychiatric Patients |

Controls |

||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||||||

| Hao et al., (2020)∗ | China | Covid-19 | Case-control study OP | 76 people with mental illness and 109 healthy controls | 32.8 (11.8) | 33.1 (11.2) | IES –R (PTSD) | 17.7 | 14.2 | 11.3 | 10.1 | Psychiatry patients were at higher risk of displaying higher levels of symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia as compared to healthy controls. |

| DASS-21 (Anxiety) | 6.6 | 90 | 1.5 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| DASS-21 (Depression) | 8.3 | 10.3 | 2.2 | 3.5 | ||||||||

| DASS-21 (Stress) | 8.0 | 9.8 | 2.7 | 4.2 | ||||||||

| ISI(Insomnia) | 10.1 | 7.16 | 4.63 | 4.04 | ||||||||

| Maguire et al., (2019)∗ | Australia | Influenza | Case control study purposive sample, cases IP and OP, controls OP | 71 people with schizophrenia and 238 controls without mental illness | 36.1 (9.7) | 36.6 (14.0) | K10: Anxiety | 8.66 | 3.25 | 7.06 | 2.84 | Patients with schizophrenia had higher levels of anxiety and psychological distress than the general population. |

| K10: Depression | 12.68 | 4.74 | 11.54 | 4.78 | ||||||||

| Iancu et al., (2005)∗ | Israel | SARS | Case control study of inpatients with schizophrenia | 30 patients with a diagnosis of Schizophrenia and 30 healthy controls who were HCWs | 36.5 (12.0) | 33.2 (7.0) | MSAS | 16.6 | 4.9 | 13.5 | 3.5 | The patient group had higher MSAS and psychotic interpretation scores than controls. Psychological reactions (anxiety, depression, fright or despair) to SARS were similar in both groups, but patients with schizophrenia felt they were more protected from SARS than the control sample. |

| Psychotic interpretation score | 12.16 | 4.0 | 8.66 | 1.7 | ||||||||

| Anxiety about SARS | 1.8 | 1.17 | 1.56 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| Depression about SARS | 1.23 | 0.81 | 1.10 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Frightened due to SARS | 1.53 | 0.94 | 1.56 | 0.73 | ||||||||

| Liu et al., (2020) | China | Covid-19 | Retrospective case-control, Case note based study (Inpatient wards) | 21 patients with schizophrenia suspected of having Covid-19 compared with 30 patients with schizophrenia not suspected of covid-19 | 43.1 (2.6) | 45 (9.2) | Suspected sample | Clean sample | No difference in psychotic symptoms, but suspected group (in isolation ward) was more depressed, anxious, stressed and had more sleep problems. | |||

| PANSS psychotic symptoms | 67.1 (19.5) | 61.5 (14.9) | ||||||||||

| PSS stress | 26.5 (6) | 11.6 (4) | ||||||||||

| HAMD depression | 14.1 (8.1) | 0.4 (0.8) | ||||||||||

| HAMA anxiety | 13.9 (9.3) | 2.2 (2.1) | ||||||||||

| PSQI sleep | 8 (3.8) | 4.7 (3.6) | ||||||||||

| Ozdin and Ozdin (2020)∗ | Turkey | Covid-19 | Internet based Cross-sectional study (Community) | 343 participants | 37.16 (10.39) | 37.16 (10.39) | Subjects with previous psychiatric illness (n = 75) | Subjects without previous psychiatric illness (n = 268) | People with previous psychiatric illness were among the groups most affected by Covid-19 pandemic. Cross sectional study, generalisability unclear, self-selected sample, but power calculation done. |

|||

| HADS (Anxiety) | 7.8 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 4.1 | ||||||||

| HADS (Depression) | 8.3 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 4.1 | ||||||||

| HAI | 18.3 | 7.2 | 14.8 | 6.9 | ||||||||

| Phillipou et al., (2020)∗ | Australia | Covid-19 | Internet based study cross sectional. Self-selected sample, self-reported diagnosis |

5496 respondents of which 108 self-reported an Eating Disorder | 30.47 | 40.62 | Eating disorder patients | General population | In the eating disorders group, increased restricting, binge eating, purging and exercise behaviours were found. | |||

| DASS-21 (Anxiety) | 12.2 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 7.3 | ||||||||

| DASS-21 (Depression) | 18.7 | 11.7 | 11.1 | 9.1 | ||||||||

| DASS-21 (Stress) | 21.0 | 10.7 | 14.5 | 8.8 | ||||||||

| Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., (2020)∗ | Spain | Covid-19 | Cross sectional-online (Community) | 213 patients with mental illness, control group were 2937 people without any illness. Author provided mean scores | 37.92 | 37.92 | PCL-C-2 (PTSD) | 2.08 | 2.34 | 1.34 | 1.76 | Presence of mental health problems were associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD. |

| GAD-2 (Anxiety) | 2.74 | 1.93 | 1.68 | 1.54 | ||||||||

| PHQ-2 (Depression) | 2.66 | 1.79 | 1.5 | 1.42 | ||||||||

| Goodman-Casanova et al., (2020) | Spain | Covid-19 | Cross-sectional telephone survey- nested in a Clinical trial TV Assist Dem (Community) | 93 patients (out of 100 who were approached) with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Consecutive sample |

73.34 (6.07) | Proportions – n(%) | Those who lived alone were at higher risk of psychological distress and sleep problems. | |||||

| Well | 57 (61%) | |||||||||||

| Calm | 8 (9%) | |||||||||||

| Sad | 27 (29%) | |||||||||||

| Worried | 20 (22%) | |||||||||||

| Afraid | 10 (11%) | |||||||||||

| Anxious | 22 (24%) | |||||||||||

| Bored | 13 (14%) | |||||||||||

| Lara et al., (2020) | Spain | Covid-19 | Follow-up study (Pre and post Covid-19 lockdown study) | 40 subjects (out of 42) seen within the last month with a diagnosis of MCI (20) or mild AD (20) | Mean age of whole sample 77.4 (5.25) | NPI | Pre covid-19 score 333.75 (22.28) |

Post confinement score 39.05 (27.96) |

Worsening of neuro-psychiatric symptoms in patients with AD and MCI during 5 weeks of lockdown, with agitation, apathy and aberrant motor activity being the most affected symptoms. | |||

| Berthelot et al., (2020) | Canada | Covid-19 | Cross sectional study of 2 cohorts of pregnant women (1 pre covid-19 pandemic sample and 1 sample during covid-19 pandemic) | 1258 Pregnant women recruited during the Covid-19 pandemic compared with 496 pregnant women recruited prior to the pandemic. | 29.35 (4.04) (mean age of Covid-19 sample) | K-10 | Scores in sample with pre-existing/lifetime psychiatric disorders not reported by authors | Pregnant women from the COVID-19 pandemic cohort reported more prenatal psychiatric distress than pregnant women from the pre-COVID-19 cohort, even when controlling for the effect of age, gestational age, education, household income and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. | ||||

| PANAS | ||||||||||||

| PCL-5 (PTSD) | ||||||||||||

| DES-II (Dissociative experiences) | ||||||||||||

| Zhou et al., (2020) | China | Covid-19 | Online Cross-sectional Questionnaire Survey (Community) | 2065 (out of 3441 out-patients who attended the Psychiatry, Neurology and Sleep medicine depts during the study period). Of these, 1434 had pre-existing psychiatric disorders. Sampling not specified |

GAD (anxiety) | Data not reported separately for patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders | 20.9% of patients with psychiatric disorders reported deterioration of their mental health. | |||||

| PHQ (depression) | ||||||||||||

| ISI (sleep) | ||||||||||||

| Fernandez-Aranda et al., (2020) | Spain | Covid-19 | Cross sectional Telephone Survey (Community) | 32 patients with Eating disorders (sampling method not specified) | 29.5 | ED symptoms | Increased in 12 (38%) | Eating disorder patients on survey reported increase in ED symptoms including grazing behaviours and emotional eating alongside over half reporting additional anxiety. | ||||

| Anxiety | Increased in 18 (56.2%) | |||||||||||

| Van Der Heide and Coutinho, (2006) | Netherlands | Influenza pandemic | Ecological time trend study | Non-significant increased number of compulsory psychiatric admissions during the peak of the 1918 Influenza pandemic in Amsterdam. Pandemic did not have a significant effect on provision of psychiatric care. | ||||||||

| Pang and Tam, (2004) | Hong Kong | SARS | Service evaluation of Psychiatric unit | There was reduction in number of patients admitted into psychiatric unit and in average length of hospitalization. Drop in outpatient attendance while people delayed entering treatment. In community services, number of home visits dropped by 50%. |

||||||||

| Clerici et al., (2020) | Italy | Covid-19 | Ecological time trend study | Reduction in the total number of psychiatry admissions. This was explained by voluntary admissions, while there was not a noticeable reduction for involuntary admissions. | ||||||||

Keywords: SD – Standard deviation,IES-R– Impact of Event Scale – Revised; DASS 21 – The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 Items; ISI –Insomnia Severity Index; K10 –Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; MSAS – Modified Spielberg Anxiety Scale; PANSS –The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSS –Perceived Stress Scale; HAMD –Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAMA –Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PSQI – Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HADS –Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAI – Health Anxiety Inventory; PCL-C-2 – PTSD Checklist Calculator 2; GAD – Generalized Anxiety Disorder;PHQ-2 –Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2);MCI – Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD – Alzheimer’s Dementia; QOL– Quality of Life; NPI– Neuropsychiatric Inventory;PANAS - Positive and negative affect schedule;PCL-5 – PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; DES-II – Dissociative Experiences Scale – II; ED – Eating disorder. ∗ indicates studies included in meta-analysis with details of scales combined.

Twelve studies reported on the mental health of people with mental illness during a pandemic, and 3 studies reported on hospitalization rates of mentally ill people during a pandemic. Of the former, 5 were case-control studies, 6 were cross-sectional studies and 1 was a cohort study. Five studies were online questionnaire surveys, 2 were telephone surveys and 2 were ecological time-trend studies. In all, there were 12 original papers, 2 commentaries and 1 editorial describing original data. Table 3 reports the RoBANS rating of the 15 included studies.

Table 3.

Risk of Bias Assessment of the 15 included studies.

| Study | Selection of participants | Confounding variables | Measurement of exposure | Blinding of outcome assessments | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hao et al., (2020) | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Maguire et al., (2019) | Unclear | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Iancu et al., (2005) | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Liu et al., (2020) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ozdin and Ozdin (2020) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Phillipou et al., (2020) | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., (2020) | High | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| Goodman-Casanova et al., (2020) | High | High | Low | High | Unclear | High |

| Lara et al., (2020) | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Berthelot et al., (2020) | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Zhou et al. (2020) | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Fernandez-Aranda et al., (2020) | High | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Van Der Heide and Coutinho, (2006) | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Pang and Tam, (2004) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Clerici et al., (2020) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Risk of Bias Assessment for Non-randomised studies (RoBANS) – 6-domains rated as low, high or unclear risk.

Of the 15 studies, 11 studies related to the Covid 19 pandemic, 2 each related to the SARS and Influenza pandemics. Studies were conducted in a mix of countries including China, Turkey, Australia, Israel, Netherlands, USA, Canada and Hong Kong. Five studies were conducted on Inpatients (or were concerned with inpatient admissions), 9 were conducted on community samples or outpatients, and 1 study recruited subjects from both an IP and OP setting.

In the case-control studies, subjects with mental illnesses had higher scores on various psychiatric symptoms (depression, anxiety, stress, psychological distress, insomnia, PTSD) than the control samples (Hao et al., 2020; Iancu et al., 2005; Maguire et al., 2019). Subjects with mental illnesses (mostly affective and anxiety disorders) were also more worried about their physical health, more angry and impulsive and harbored more suicidal ideas than the control subjects (Hao et al., 2020). The study from Israel found that in-patients with schizophrenia had higher scores on a scale assessing psychotic interpretation of pandemic related events than the control group of health care workers (Iancu et al., 2005). However a more recent study by Liu et al. (2020) which compared schizophrenic subjects who were suspected of having Covid 19 with those who were not suspected of the same, found no difference in PANSS scores in the two groups. They found that the Covid suspect group was found to have more anxiety, depression, stress and sleep problems than the comparator group (Liu et al., 2020).

There were only 2 studies that compared subjects before the pandemic with those during a pandemic. Both these were conducted during the Covid 19 pandemic. Berthelot et al. from Canada compared pregnant women recruited during the Covid 19 pandemic with another sample that had been recruited prior to the pandemic, and found that previous diagnosis of psychiatric disorder predicted elevated distress and psychiatric symptoms (Berthelot et al., 2020). Lara et al. (2020) studied neuropsychiatric symptoms amongst elderly patients with Mild Cognitive impairment or Mild Dementia before the Covid 19 pandemic and 5 weeks after the Covid lockdown began. They found a significant increase in neuropsychiatric symptoms-especially agitation, apathy and aberrant motor activity after the lockdown started. However, they did not find any significant change in the QOL after the lockdown started.

Amongst the observational cross-sectional studies, previous psychiatric illnesses predicted anxiety in an online survey of 343 Turkish subjects (Ozdin and Ozdin, 2020). Two studies reported higher scores on anxiety, depression, stress and eating-related symptoms (or an increase in these) amongst patients with eating disorders. Of these one was an online survey of 5469 subjects in Australia (Phillipou et al., 2020) and the other was a pilot study of 32 subjects at an Eating disorder unit in Spain (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020). Previous psychiatric illness was significantly associated with depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms in an online survey of 3480 Spanish subjects (Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., 2020). One study that looked at the mental health of subjects with mild cognitive decline or dementia found their overall mental health to be optimal. However, a proportion of subjects were found to be sad, worried or anxious, and the likelihood of psychological distress was higher amongst those who lived on their own (Goodman-Casanova et al., 2020). Finally, Zhou et al. (2020), in a commentary article, reported that 21% (n = 300) of patients with pre-existing mental illness (n = 1434) experienced a deterioration in their mental health.

With respect to hospitalization rates, both Pang and Tam (2004) and Clerici et al. (2020) reported a reduction in psychiatric admission rates, outpatient attendance and community visits during the SARS and Covid 19 pandemics. But this reduction in psychiatric admissions was not noted by Van Der Heide and Coutinho (2006) in their ecological time-trend study of the Influenza pandemic of 1918 (Van Der Heide and Coutinho 2006).

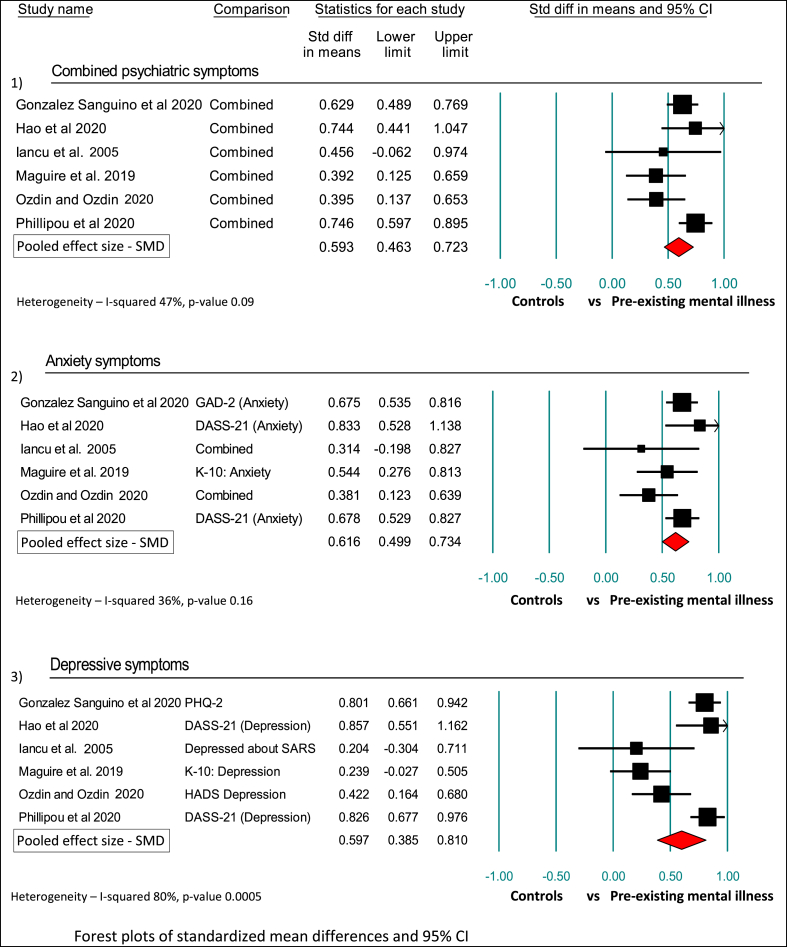

For the meta-analysis, six studies provided computable data allowing sample size totaling 9516 participants (Lara et al. 2020; Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., 2020; Hao et al., 2020; Iancu et al., 2005; Maguire et al., 2019; Ozdin and Ozdin, 2020). These included people with pre-existing mental illness (n = 645) and controls (n = 8871). The six studies provided mean scores and standard deviations in both groups that were used to calculate a pooled effect size of SMD. The calculations of SMD are presented for anxiety and depressive symptoms which were the predominant continuous data reported in studies. A combined SMD including all reported psychiatric symptoms has also been calculated using random-effects model. The SMD of the combined psychiatric symptoms (includes stress, insomnia, PTSD, depression, anxiety, psychotic symptoms) across six studies was 0.593 (C.I. 95% 0.46 to 0.72). SMD specifically for anxiety symptoms was 0.616 (C.I. 95% 0.49 to 0.73), likewise the SMD for depressive symptoms was 0.597 (C.I. 95% 0.38 to 0.80). All the effect sizes were statistically significant with p-values < 0.0001. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Tau-squared and I-squared. The tau-squared across the three analyses were significantly low. The combined psychiatric symptoms and anxiety symptoms pooling did not indicate any significant heterogeneity and had I-squared of 47% and 36% with p-value of 0.09 and 0.16 respectively. However, the pooling of depressive symptoms showed I-squared of 80% and significant p-value. Fig. 2, shows forest plot of all three analyses with the pooled effect size, SMD of each study and the overall measures of heterogeneity.

Fig. 2.

1) Forest plot of standardized mean difference for combined psychiatric symptoms in controls and people with pre-existing mental illness (includes data from rating scales assessing insomnia, stress, PTSD, anxiety, depression and psychotic symptoms-see Table 2), tau-squared of 0.011.2) Forest plot of standardized mean difference for Anxiety symptoms in controls and people with pre-existing mental illness (combined in Iancu et al., 2005 includes data of Modified Spielberg Anxiety scale and SARS anxiety, combined in Ozdin and Ozdin, 2020 includes data from Health Anxiety Inventory and anxiety scores from Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale), tau-squared 0.007.3) Forest plot of standardized mean difference for depressive symptoms in controls and people with pre-existing mental illness, tau-squared 0.05. Red diamond marker indicates pooled effect size of standardized mean difference (SMD), black square marker indicates computed individual study SMD, and line across square marker indicates 95% confidence interval (CI). GAD-2 – Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2, DASS-21 – Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale, K-10 – Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, and HADS – Hamilton Depression Rating scale. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The significance held up against sensitivity analyses including removing each one of the studies in calculating the pooled effect size. Meta-regression of mean age of people with mental illness did not show any significant association with the effect size (p-value 0.229). The effect size in sub-group analysis held up significance in Covid-19 and Influenza pandemic but not in SARS. Likewise, effect size in sub-group analysis of the country of origin held significance for Australia, China and Spain but not for Israel and Turkey. As the overall p-value of the SMD from the analyses was <0.0001 the significance of publication bias was assessed by calculating number of fail-safe studies with null effect (SMD of 0) needed to shift the p-value from <0.0001 to 0.05. A total of 347 unpublished studies would be needed to shift our p-value from <0.0001 to 0.05 (Zc (α = 0.05) = 1.645). Rosenberg (2005) described the Fail-safe N as an intuitive approach that allows a better estimate of potential of unpublished or missing studies to alter study conclusions. Rosenberg suggests a low fail-safe N may require further complex modeling of publication bias whilst high fail-safe N is unlikely to be a problem. Publication bias in our study is unlikely to influence the meta-analysis results as a high fail-safe N of 347 unpublished or missing studies with null effect are needed to shift the p-value.

Three studies were identified that reported on hospitalization rates amongst people with mental illness during pandemics. These are retrospective ecological time-trend studies that looked at psychiatric hospital admissions during a pandemic. The Van Der Heide study reported a (non-significant) increase in compulsory hospital admissions in Amsterdam during the 1918 Influenza pandemic (Van Der Heide and Coutinho 2006). Both studies Pang and Tam (2004) and Clerici et al. (2020) reported reduction in the psychiatric admissions (voluntary, but not compulsory) during the SARS and the Covid-19 pandemics respectively. They also reported a reduction in the length of stay in hospital, OP attendance and community visits.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to review evidence on the effects of pandemics on the mental health of people with mental illness. The search strategy was broad-based, and was devised to include all research that reported on the index questions, i.e., mental health of people with pre-existing mental illness and psychiatric hospitalization rates during a pandemic. Fifteen studies were found that addressed these questions.

4.1. Quality of studies, bias and limitations

Most of the available research has been done in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. As such, the findings of this review are likely to be more applicable to this pandemic, which is probably quite different to the earlier pandemics that the world has seen-both in terms of the effects of the pandemic itself, as well as how the world has responded to it. With respect to the studies included in this review, the study designs were heterogeneous. Five studies were conducted through online questionnaires (Berthelot et al., 2020; Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020; Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., 2020; Ozdin and Ozdin, 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020). Some cross-sectional studies from the search results were conducted in subjects with defined disorders (e.g. schizophrenia, eating disorders or cognitive disorders), while others reported upon subjects with a history of psychiatric illness. None of these studies detailed the nature or the severity of the psychiatric illness, nor did they specify whether the subjects included were actively symptomatic or in remission. This could be important as people in remission may be affected differently by the pandemic, as compared to those who are actively psychiatrically symptomatic. This factor needs to be considered when drawing inferences from this review. Studies used a number of different control samples and included a group of healthcare workers, general hospital outpatients and asymptomatic community respondents. Convenience or purposive sampling was used to recruit subjects; a power calculation of sample size estimation was mentioned in only one study (Ozdin and Ozdin, 2020). It is therefore unclear as to whether many studies were sufficiently representative and powered to draw valid conclusions.

Most of the studies were online or telephone surveys. As such, the reliability of self-reported psychiatric diagnoses cannot be ascertained. With respect to the assessments used, studies used various measures of anxiety, depression, stress, sleep problems and overall psychiatric distress, and these were reported in a number of different ways. For example, some studies reported means and standard deviations of these measures in the cases and the controls, others only reported prevalence of these parameters in the study population. Some others only reported upon associations of a history of psychiatric illness with these mental health parameters.

There was some heterogeneity in the types of subjects studied, study methods, instruments used and the data analysis. The cross-sectional nature of most studies does not allow for any causal interpretations on the effect of the disease pandemic on exacerbations of psychiatric symptoms. The only credible study design from which firm conclusions can be drawn is a repeated measures (i.e. before and during the pandemic, or during and after) case control design. The only prospective study that touched upon this aspect was the report by Lara et al. (2020) on an elderly sample with a cognitive disorder, who experienced an increase in neuropsychiatric symptoms after the lockdown.

4.2. Increase in symptoms during pandemics

Our first research question was whether people with mental illness experience an increase in symptoms during pandemics. We analyzed twelve studies that looked at how current and past pandemics affected the mental health of this group of people. All included studies showed that people with mental illness experienced more psychiatric symptoms during pandemics when compared to control groups. Major symptoms identified included increased anxiety, depression and insomnia. However, whether this higher rate is causally related to the pandemic itself is not shown in most of these studies due to their limited designs.

Social interaction is known to be beneficial to recovery in schizophrenia. Pandemics are generally followed by disease control measures like isolation, quarantines and physical distancing. These measures limit social contact, which is crucial for mentally ill people to recover from their illnesses. Most are unable to continue with established daily routines and group activities. This leaves them with time to ruminate on negative cognitions that manifest as depression and paranoid thoughts.

The meta-analysis from the six studies evidences increased levels of psychiatric symptoms in people with pre-existing mental illnesses. The SMD effect size was over 0.5 indicating clinically and statistically significant higher rates of symptoms on recognized psychiatric rating scales in people with pre-existing mental illness compared to controls exposed to the same effects of pandemic. Although the measure of heterogeneity was statistically non-significant and the tau-squared low the degree of combinability has logical limitations as the studies are from different populations. Likewise, publication bias was assessed with a fail-safe N approach calculating missing studies with null effect. This can be considered as arbitrary as there could be missing negative studies. The findings of this review highlight the need to devise pandemic-management strategies that are supportive of the needs of people with mental illness and enable their recovery. In particular during pandemics anxiety symptoms are significantly higher in people with pre-existing mental illnesses than those without history of mental illness.

4.3. Psychiatric hospitalizations during pandemics

Our second research question was whether people with mental illness experience more hospitalizations during pandemics. From the outcome of our search, it is evident that there has been paucity of research work that attempted to categorically answer this question. There have been many opinions and observations suggesting patterns as they are observed but we found only 3 previous studies that attempted to provide an objective insight.

While one study suggests a non-significant increase in compulsory hospital admissions during the 1918 Influenza pandemic in Amsterdam, two others reported a reduction in admissions (mainly voluntary) and use of mental health services in more recent disease pandemics.

One interpretation of the review might be that psychiatric symptoms are exacerbated during pandemics, but the fact that no consequent increase in service utilization was observed suggests that the symptom severity simply reflected pre-existing morbidity, with important implications for the future design of longitudinal observational studies in this crucial area. There could be other plausible explanations for this apparent incongruity. It is likely that pandemic management strategies of different governments discourage close physical proximity, and this is reflected by health services striving to avoid hospital admissions as much as possible. This possibility is supported by the finding in Clerici et al. (2020) study of a reduction in voluntary (but not involuntary) admissions. Zhou et al. (2020) identified transportation restrictions, isolation, and fear of cross-infection at hospitals as major concerns and barriers to treatment which may also explain the reduction of service utilization. In their study, patients even reduced or stopped medications completely because they could not gain access to further prescriptions from physicians during the outbreak. In similar light, Hao et al. (2020) identified three factors which they attributed to the cause in reduction in service. First being that mental health services become a lower priority in the face of acute physical health problems seen in pandemics like covid-19. Secondly, psychiatric patients are actively encouraged to keep away from attending hospitals to reduce pressure on services and finally, lockdown measures made it difficult for psychiatric patients to attend to see psychiatrists. There is also the fear of being infected when they visit hospitals. Suspension of routine consultations and community mental health services to facilitate physical distancing is also likely to have contributed to the increase in mental distress in people with mental illnesses.

5. Conclusion

The salient findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis can be distilled as follows: Most of the studies identified in this review relate to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, which is quite different from past pandemics in a number of ways. These differences range from the extent of the pandemic and its severity, to the extent of control measures like social distancing, isolation and quarantine measures, and the use of extended restrictions and lockdown measures across the world-all of which can impact upon the mental health and services. From the studies included, elderly people with cognitive disorders experienced a worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms (mainly apathy, anger and aberrant motor activities) during the Covid 19 pandemic. Subjects with eating disorders reported an increase in eating disorder related symptoms-restricting, purging and bingeing during a disease pandemic. There was no evidence of worsening psychotic symptoms in people with schizophrenia. Overall, people with pre-existing mental illnesses experience high levels of anxiety, depression, stress and sleep problems during pandemics. These are higher than that observed amongst control subjects exposed to the similar pandemic with significant effect size (SMD) of 0.593. Whether this is clearly due to the pandemic or simply reflects higher levels of symptoms in a clinical population is unclear. Although, a precise effect size with reasonable consistency suggests a need for mental health services to address the increased mental health symptoms in people with pre-existing mental illnesses during a pandemic. The small number of studies and their design shortcomings indicate how important well-designed repeated measure case control studies will be during a pandemic.

Authors’ contributions

KN conceived and designed the study. VD and SL further updated the study design. KN and NA developed the search strategy. NA and JN reviewed the literature, identified potential articles, study selection and data extraction. KN performed the meta-analyses. All authors interpreted the results, contributed to the preparation of the manuscript, revised manuscript drafts, read and approved the final version.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Coulshed of GMMH NHS Trust Library for procuring some of the articles used for this review. KN would like to thank the University of Manchester for the Honorary Senior Lecturer appointment and for the access to resources.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100177

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Berthelot Nicolas, Lemieux Roxanne, Garon-Bissonnette Julia, Drouin-Maziade Christine, Martel Elodie, Maziade Michel. ‘Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic’. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99(7):848–855. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J.P., Rothstein H.R. ’A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods. 2010;1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Ellie, Gray Richard, Monaco Samantha Lo, O’Donoghue Brian, Nelson Barnaby, Thompson Andrew, Francey Shona, McGorry Pat. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: a rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222(Aug):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M., Durbano F., Spinogatti F., Vita A., De Girolamo G., Micciolo R. ’Psychiatric hospitalization rates in Italy before and during covid-19: did they change? an analysis of register data. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020;(May):1–8. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ): 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Aranda F., Casas M., Claes L., Bryan D.C., Favaro A., Granero R., Gudiol C., Jimenez-Murcia S., Karwautz A., Le Grange D., Menchon J.M., Tchanturia K., Treasure J. ’COVID-19 and implications for eating disorders. Eur. Eat Disord. Rev. 2020;28:239–245. doi: 10.1002/erv.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sanguino Clara, Ausin Berta, Castellanos Miguel Angel, Jesus Saiz, Lopez-Gomez Aida, Ugidos Carolina, Munoz Manuel. ‘Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain’. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87(July):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Casanova, Marian Jessica, Dura-Perez Elena, Guzman-Parra Jose, Cuesta-Vargas Antonio, Mayoral-Cleries Fermin. ‘Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study’. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Fengyi, Tan Wanqiu, Jiang Li, Zhang Ling, Zhao Xinling, Zou Yiran, Hu Yirong, Luo Xi, Jiang Xiaojiang, McIntyre Roger S., Tran Bach, Sun Jiaqian, Zhang Zhisong, Ho Roger, Ho Cyrus, Tam Wilson. ‘Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry’. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87(July):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hert M.D.E., Correll C.U., Bobes J., Cetkovich-Bakmas M., Cohen D., Asai I., Detraux J., Gautam S., Moller H.J., Ndetei D.M., Newcomer J.W., Uwakwe R., Leucht S. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatr. 2011;10:52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iancu I., Strous R., Poreh A., Kotler M., Chelben Y. ’Psychiatric inpatients’ reactions to the SARS epidemic: an Israeli survey’. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2005;42:258–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Park J.E., Lee Y.J. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;66(4):408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara B., Carnes A., Dakterzada F., Benitez I., Pinol-Ripoll G. ‘Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish Alzheimer’s disease patients during COVID-19 lockdown’. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020;27:1744–1747. doi: 10.1111/ene.14339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S., Burkard T., Henderson J., Maj M., Sartorius N. ’Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007;116:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xuebing, Lin Hong, Jiang Haifeng, Li Ruihua, Zhong Na, Su Hang, Li Yi, Zhao Min. ’Clinical characteristics of hospitalised patients with schizophrenia who were suspected to have coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China’. General Psychiatry. 2020;33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire Paul A., Reay Rebecca E., Looi Jeffrey Cl. ’A sense of dread: affect and risk perception in people with schizophrenia during an influenza pandemic. Australas. Psychiatr. 2019;27:450–455. doi: 10.1177/1039856219839467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Prisma Group ’Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdin Selcuk, Ozdin Sukriye Bayrak. ‘Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender’. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2020;66(5):504–511. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Pui-Fai, Tam Woon-chi. Psychiatric Times; 2004. The Impact of SARS on Psychiatric Services: Report from Hong Kong; pp. 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. ‘Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis’. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88(Aug):901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipou Andrea, Meyer Denny, Neill Erica, Tan Eric J., Toh Wei Lin, Tamsyn E., Van Rheenen, Rossell Susan L. ‘Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project’. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020;53:1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/eat.23317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar Ravi Philip. ‘COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature’. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;52(Aug):102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers Mark, Dalton Jane, Harden Melissa, Street Andrew, Parker Gillian, Eastwood Alison. Health Services and Delivery Research. 4(13) NIHR; 2016. Integrated Care to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness : a Rapid Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers Jonathan P., Chesney Edward, Oliver Dominic, Pollak Thomas A., McGuire Philip, Fusar-Poli Paolo, Zandi Michael S., Lewis Glyn, David Anthony S. ‘Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic’. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M.S. The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution. 2005;59(2):464–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., Olkin I., Williamson G.D., Rennie D., Moher D., Becker B.J., Sipe T.A., Thacker S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000 Apr 19;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs Brett D., Bonardi Olivia, Rice Danielle B., Boruff Jill T., Azar Marleine, Chen He, Markham Sarah, Sun Ying, Wu Yin, Krishnan Ankur, Thombs-Vite Ian, Benedetti Andrea. ’Curating evidence on mental health during COVID-19: a living systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;133(Jun):110113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Heide D.H., Coutinho R.A. ’No effect of the 1918 influenza pandemic on the incidence of acute compulsory psychiatric admissions in Amsterdam. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2006;21:249–250. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-0007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;89(Oct):531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Junying, Liu Liu, Xue Pei, Yang Xiaorong, Tang Xiangdong. ‘Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China’. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2020;177(7):574–575. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (a) 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19--11-march-2020

- World Health Organization (b) 2020. https://covid19.who.int/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.