Abstract

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vertigo worldwide. This review considers recent advances in the diagnosis and management of BPPV including the use of web-based technology and artificial intelligence as well as the evidence supporting the use of vitamin D supplements for patients with BPPV and subnormal serum vitamin D.

Keywords: Dizziness, Vertigo, Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Introduction

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is characterized by paroxysms of vertigo triggered by head position changes in the direction of gravity [1]. BPPV is explained by migration of degenerated otoconia into the semicircular canals, rendering them sensitive to head motion [2]. BPPV is the most common cause of dizziness/vertigo worldwide with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%, a 1-year prevalence of 1.6%, and 1-year incidence of 0.6% [3]. BPPV accounts for 24.1% of all hospital visits due to dizziness/vertigo [4]. BPPV is most common in elderly women with a peak incidence in their sixties and a women-to-men ratio of 2.4:1 [4]. Recurrences of BPPV are frequent [5, 6] with an annual recurrence rate of 15–20% [7, 8].

Even though benign in nature, patients with BPPV are markedly limited in their daily activities [10, 11]. The medical costs for diagnosis of BPPV have been estimated at 2,000 US$ in the USA [12], 364 Euros (~ 450 US$) in Spain [13], RMB 4165.2 Yuan (~ 600 US$) in China [14], and 180 US$ in South Korea [9]. Therefore, the healthcare burden due to BPPV totals around 2 billion US$ in the USA per year [15] and is likely to increase as the population ages. According to data from South Korea, the number of hospital visits per 100,000 of general population due to dizziness and vertigo was around 3974 in 2019 and could increase to 6057 by 2050, which corresponds to an increase of 52% [4].

Pathophysiology

The cause of BPPV is mostly unknown although cases may be associated with head trauma, a prolonged recumbent position, or various disorders involving the inner ear [16]. Other risk factors for BPPV may include female gender, age under 65 years, a high income, living in a metropolis, osteoporosis, hypertension, and non-apnea sleep disorders [17–20]. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis found that female gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and vitamin D deficiency are risk factors for recurrences of BPPV [19]. Linked to this is the finding that elderly women with a lack of physical activity have a 2.6 times higher risk for BPPV than those who undertake regular activity [21]. Furthermore, vitamin D deficiency (< 10 ng/ml) and insufficiency (10–20 ng/ml) have been associated with BPPV with an odds ratios of 3.8 and 23.0 [22]. This has obvious therapeutic implications (see below).

Clinical features

In the western countries, the posterior canal (PC) has been known to be the most commonly involved (88–90%) in BPPV with a predilection for the right ear [23, 24]. In studies conducted in South Korea, however, involvement of other semicircular canals (not just the PC) has been shown to be more common than previously reported in western countries [25]. Even though the PC was most commonly involved (59–61%), BPPV of the non-pure PC-BPPV type comprises about 40% of total BPPV, especially with involvement of the horizontal canal (HC-BPPV), where the otolithic debris may be located either in the canal (canalolithiatic or geotropic, 61–66%) or attached to the cupula (cupulolithiatic or apogeotropic, 31–33%) [10, 21]. The causes for this discrepancy is unknown [25].

Diagnosis

The International Classification of Vestibular Disorders (ICVD) formulated by the Barany Society established the diagnostic criteria for BPPV [26], which include recurrent attacks of positional vertigo/dizziness provoked by position changes, and the characteristic positional nystagmus elicited by each positional maneuver according to the subtype and affected ear [26]. During the Dix-Hallpike maneuver for diagnosis of PC-BPPV, a pillow may be placed under the shoulders instead of extending the patient’s neck about 30° below the table [27]. This modified maneuver may be useful in the limited clinical setting or in patients with a limited range of motion or difficulty relaxing their neck. HC-BPPV is diagnosed by determining the direction and relative intensity of the horizontal nystagmus induced during head-turning while supine. In both the canalolithiatic (geotropic) and cupulolithiatic (apogeotropic) types of HC-BPPV, the nystagmus beating to the lesion side is greater than that to the healthy side [1]. The accuracy of bedside lateralization of the affected side is acceptable in HC-BPPV when the nystagmus asymmetry is more than 30% [28]. When the intensities of nystagmus triggered during supine head-rolling test are similar between the directions, the direction of nystagmus induced by lying down or head bending (bow and lean test) may aid in lateralization of the involved side [29, 30]. The lying-down nystagmus mostly beats away from the affected ear in geotropic HC-BPPV but beats toward the affected ear in the apogeotropic type, while the reverse holds for the head-bending nystagmus [29, 30]. Patients with PC-BPPV may show vertical nystagmus during the bow-and-lean test [31]. A recent study found that head-shaking nystagmus (the nystagmus observed after head oscillation at 2–3 Hz in the horizontal plane for 20 cycles) occurs in about a half of the patients with HC-BPPV in the direction of head-bending nystagmus, thus helping lateralize the affected side [32].

The duration of vertigo and nystagmus is typically less than one minute in the canalolithiatic type of HC-BPPV [33]. Nevertheless, patients occasionally show persistent geotropic nystagmus while supine head-turning. This persistent geotropic positional nystagmus may be observed in association with focal central lesions [34], alterations in the specific gravity of the cupula or endolymph (light cupula) [35–37], or in migraine [38, 39] even though the mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus may be observed during head extension not only in central lesions or BPPV involving the anterior canal (AC-BPPV) but due to compression of both vertebral arteries [40]. Positional nystagmus due to central lesions (central positional nystagmus, CPN) may be either paroxysmal or persistent, and both types of CPN may be ascribed to impaired central processing of canal and otolith signals [41]. Even though CPN may be differentiated from BPPV based on the temporal patterns of nystagmus intensity, occurrence of nystagmus in multiple planes, and additional ocular motor or other neurological findings indicative of central lesions [41, 42], clinicians should be careful when the seemingly BPPV does not respond to repeated canalith repositioning procedures.

Otolin-1 is an inner ear-specific collagen that forms a scaffold to promote optimal formation of the otoconia. Owing to its potential passage through the labyrinth-blood barrier, otolin-1 can be detected in the peripheral blood and may serve a biomarker for BPPV [19]. Thus, high serum levels of otolin-1 (> 300 pg/ml) may discriminate patients with BPPV from healthy controls [20].

The gold standard for diagnosing and determining the subtype of BPPV is the observation of characteristic nystagmus triggered during the positional maneuvers as mentioned above. However, a few studies have explored the utility of questionnaires in confirming BPPV and determining the subtypes [43–45] based on the characteristics (positional triggering, duration etc.) of the vertigo and positional changes that mostly induce it. [43]. A recent study investigating this questionnaire approach showed an acceptable sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of BPPV [45]. The questionnaire is comprised of six questions. The first three are designed to diagnose BPPV, and the latter three to determine the subtype and affected ear. This new approach for self-diagnosis of BPPV using a questionnaire would pave the way for self-administration of an appropriate canalith repositioning procedure when BPPV occurs and recurs.

By virtue of both recent developments in information (IT) and biology (BT) technology through programs available on mobile devices [46] and using artificial intelligence and a deep-learning model, interest has turned to whether this approach can be used to determine the underlying disorder(s) causing dizziness and vertigo, and with this the subtype of BPPV [47]. Furthermore, recording of nystagmus during the attacks of vertigo may also become feasible in near future using various portable devices [48]. These kinds of approaches adopting artificial intelligence, deep-learning, wearable devices, and mobile applications, will become more important in determining the cause of vertigo, especially when we have to rely more on telemedicine as is the case now given the COVID-19 pandemic.

BPPV patients show 1-year recurrence rates of approximately 20% and 5-year recurrence rates of approximate.

Treatments

Even though BPPV may resolve spontaneously, canalith repositioning procedure (CRP) has been established as the gold standard for the treatment of BPPV during the attacks [1, 49–51]. CRPs may result in resolution of symptoms and positional nystagmus in 80% with a single application [52], and in up to 92% with a repetition [53]. Various CRPs have shown efficacy in randomized controlled trials, and this includes the Epley and Semont maneuvers for PC-BPPV [54, 55], barbecue rotation and Gufoni’s maneuver for geotropic HC-BPPV [56], and head-shaking and Gufoni’s maneuvers for apogeotropic HC-BPPV [57]. For AC-BPPV, several maneuvers including the reversed Epley’s [58] and Yacovino’s maneuvers [59] may be attempted [60]. A multi-axis positioning chair attached to the video-oculography may be applied for treatment of BPPV [61, 62]. Modified or simplified versions of CRPs have also been proposed [63]. The Gans maneuver has shown long-term efficacy similar to Epley maneuver for PC-BPPV [64]. The efficacy of Li’s quick repositioning maneuver was similar to that of the barbecue maneuver for geotropic HC-BPPV [65]. Another maneuver adopted an affected-ear-up 90° position for geotropic HC-BPPV and reported resolution of the symptoms in 83% [66]. These maneuvers, however, require further validation through randomized controlled trials. A recent study established the efficacy of forced prolonged position for HC-BPPV in comparison to a sham maneuver using a double-blind randomized trial [67]. In this study, patients with geotropic HC-BPPV (n = 149) were instructed to stay lying on the healthy side in the treatment group and on the involved side in the sham group (76.9 vs. 11.3%, p < 0.0001), and vice versa in the apogeotropic type (n = 72, 60.5 vs. 17.6%, p = 0.0003) [67].

These CRPs may be attempted by the patients themselves at home. Adding self-treatments at home after the CRPs performed at the office/clinic is more effective than the office/clinic-based CRPs alone [68, 69]. Some devices have also been developed for an easy and accurate application of the CRPs at home [70, 71]. However, self-application of CRPs requires an accurate identification of the involved canal and subtype of BPPV. For this purpose, a simple questionnaire consisting of six questions, which was mentioned above, was developed and showed an accuracy of 71.2% in diagnosing BPPV and determining the involved canal and type [45]. Furthermore, a clinical trial is under way for self-application of CRPs based on the results of this questionnaire (CRIS registry no. KCT00002364) [45].

Patients with BPPV occasionally suffer from persistent vertigo after CRPs. In these instances, the residual otolithic debris may be located in the distal portion of the PC, and the patients may show positional downbeat nystagmus due to migration of the debris toward the ampulla during the positioning [72]. In this instance, repetition of CRPs may help treat the residual vertigo.

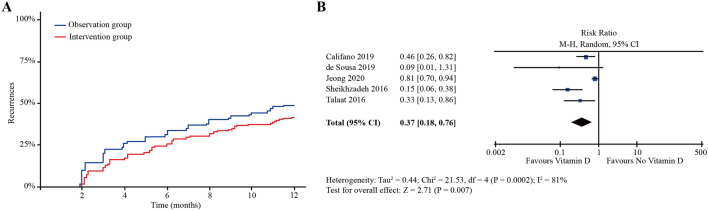

Repeat attacks of BPPV are frequent [5, 6] with the recurrences in a half of the patients within 40 months [7, 8]. A recent study found that these recurrences were somewhat random with only 24% of them involving the same canal on the same side as was affected in the previous attack [9]. A role for vitamin D in BPPV has recently been shown to be significant. In a recent randomized clinical trial, patients with BPPV were randomly allocated either to have measurements of serum vitamin D and take 400 IU vitamin D and 500 mg calcium twice a day when the serum vitamin D level was subnormal or to be simply followed-up for the recurrences without intervention. A significant reduction in the recurrences was found in the treatment group (Fig. 1a) [73]. A subsequent meta-analysis of six randomized trials also proved the preventive effect of vitamin D supplementation on recurrences of BPPV (Fig. 1b) [74]. Thus, supplementation of vitamin D should be considered in patients with recurrent BPPV and subnormal serum vitamin D.

Fig. 1.

a Intake of vitamin D 400 IU and calcium carbonate 500 mg twice a day for 1 year significantly lowered the recurrences of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in patients with BPPV and subnormal serum vitamin D. b A meta-analysis showed a preventive effect of vitamin D supplementation on the recurrences of BPPV.

Adapted from the reference [74]

Otolith dysfunction could be associated with an increase in the recurrences of BPPV [75, 76]. Thus, the vestibular rehabilitation program including may reduce the recurrence rate of BPPV [77]. This program includes jumping on the trampoline-like surface with eyes open and closed, reading a text during linear head movements, standing on the tilt board and using an exercise ball.

Conclusion

Even though benign, BPPV brings with it major socio-economic impacts. Being able to better diagnose this, especially using remote devices would be a major breakthrough and ways to do this are being actively explored with encouraging data to support their adoption. In addition, while a range of physical therapies can be successfully used to treat BPPV, there are interesting new data suggesting a role for vitamin D supplementation in a subgroup of patients with low serum levels of this vitamin.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare (Grant no. HI16C0429).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

Dr. H-J Kim, and Dr. J-H Park report no disclosures. Dr. J-S Kim serves as an Associate Editor of Frontiers in Neuro-otology and on the editorial boards of the Journal of Clinical Neurology, Frontiers in Neuro-ophthalmology, Journal of Neuroophthalmology, and Journal of Vestibular Research.

Footnotes

Hyo-Jung Kim and JaeHan Park equally contributed to this study.

Change history

2/23/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s00415-021-10476-y

References

- 1.Kim JS, Zee DS. Clinical practice. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1138–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1309481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) CMAJ. 2003;169(7):681–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, Lempert T, Neuhauser H. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):710–715. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HJ, Lee JO, Choi JY, Kim JS. Etiologic distribution of dizziness and vertigo in a referral-based dizziness clinic in South Korea. J Neurol. 2020;267(8):2252–2259. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balatsouras DG, Koukoutsis G, Ganelis P, Economou NC, Moukos A, Aspris A, Katotomichelakis M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to vestibular neuritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(5):919–924. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanimoto H, Doi K, Nishikawa T, Nibu K. Risk factors for recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(6):832–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt T, Huppert D, Hecht J, Karch C, Strupp M. Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: a long-term follow-up (6–17 years) of 125 patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126(2):160–163. doi: 10.1080/00016480500280140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunez RA, Cass SP, Furman JM. Short- and long-term outcomes of canalith repositioning for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(5):647–652. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HJ, Kim JS. The patterns of recurrences in idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and self-treatment evaluation. Front Neurol. 2017;8:690. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martens C, Goplen FK, Aasen T, Nordfalk KF, Nordahl SHG. Dizziness handicap and clinical characteristics of posterior and lateral canal BPPV. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(8):2181–2189. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira AB, Santos JN, Volpe FM. Effect of Epley's maneuver on the quality of life of paroxismal positional benign vertigo patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(6):704–708. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000600006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li JC, Li CJ, Epley J, Weinberg L. Cost-effective management of benign positional vertigo using canalith repositioning. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(3):334–339. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.100752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez P, Manrique C, Álvarez MJ, Aldama P, Álvarez JC, Luisa Fernández M, Méndez JC. Evaluation of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in primary health-care and first level specialist care. Acta Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed) 2008;59(6):277–282. doi: 10.1016/S2173-5735(08)70238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang YL, Wu MY, Cheng PL, Pei SF, Liu Y, Liu YM. Analysis of cost and effectiveness of treatment in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019;132(3):342–345. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, Fife T, Holmberg JM, Mahoney K, Hollingsworth DB, Roberts R, Seidman MD, Steiner RW, Do BT, Voelker CC, Waguespack RW, Corrigan MD. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (update) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(3_suppl):S1–S47. doi: 10.1177/0194599816689667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baloh RW, Honrubia V, Jacobson K. Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology. 1987;37(3):371–378. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byun H, Chung JH, Lee SH, Park CW, Kim EM, Kim I. Increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in osteoporosis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3469. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39830-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih CP, Wang CH, Chung CH, Lin HC, Chen HC, Lee JC, Chien WC. Increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with non-apnea sleep disorders: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(12):2021–2029. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Zhang S, Cui K, Liu C. Risk factors for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang H, Gu H, Sun W, Li Y, Wu H, Burnee M, Zhuang J. Estradiol deficiency is a risk factor for idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in postmenopausal female patients. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(4):948–953. doi: 10.1002/lary.26628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazoni JA, Mendes WS, Meneses-Barriviera CL, Melo JJ, Costa Vde S, Teixeira Dde C, Marchiori LL. Physical activity in the prevention of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: probable association. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;18(4):387–390. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1384815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong SH, Kim JS, Shin JW, Kim S, Lee H, Lee AY, Kim JM, Jo H, Song J, Ghim Y. Decreased serum vitamin D in idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol. 2013;260(3):832–838. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korres S, Balatsouras DG, Kaberos A, Economou C, Kandiloros D, Ferekidis E. Occurrence of semicircular canal involvement in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(6):926–932. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200211000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soto-Varela A, Santos-Perez S, Rossi-Izquierdo M, Sanchez-Sellero I. Are the three canals equally susceptible to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Audiol Neurotol. 2013;18(5):327–334. doi: 10.1159/000354649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moon SY, Kim JS, Kim BK, Kim JI, Lee H, Son SI, Kim KS, Rhee CK, Han GC, Lee WS. Clinical characteristics of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Korea: a multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21(3):539–543. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Brevern M, Bertholon P, Brandt T, Fife T, Imai T, Nuti D, Newman-Toker D. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2015;25(3–4):105–117. doi: 10.3233/VES-150553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeon EJ, Lee DH, Park JM, Oh JH, Seo JH. The efficacy of a modified Dix–Hallpike test with a pillow under shoulders. J Vestib Res. 2019;29(4):197–203. doi: 10.3233/VES-190666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SY, Oh SW, Kim HJ, Kim JS. Determinants for bedside lateralization of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo involving the horizontal semicircular canal. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1709–1714. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han BI, Oh HJ, Kim JS. Nystagmus while recumbent in horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2006;66(5):706–710. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201184.69134.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choung YH, Shin YR, Kahng H, Park K, Choi SJ. 'Bow and lean test' to determine the affected ear of horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(10):1776–1781. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000231291.44818.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choo OS, Kim H, Jang JH, Park HY, Choung YH. Vertical nystagmus in the bow and lean test may indicate hidden posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: hypothesis of the location of otoconia. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6514. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63630-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H, Kim HA. The association of head shaking nystagmus with head-bending and lying-down nystagmus in horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res. 2020;30(2):95–100. doi: 10.3233/VES-200696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Brevern M, Bertholon P, Brandt T, Fife T, Imai T, Nuti D, Newman-Toker D. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: diagnostic criteria consensus document of the Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Barany Society. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2017;68(6):349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi SY, Jang JY, Oh EH, Choi JH, Park JY, Lee SH, Choi KD. Persistent geotropic positional nystagmus in unilateral cerebellar lesions. Neurology. 2018;91(11):e1053–e1057. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim CH, Kim MB, Ban JH. Persistent geotropic direction-changing positional nystagmus with a null plane: the light cupula. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):E15–19. doi: 10.1002/lary.24048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi JY, Lee ES, Kim HJ, Kim JS. Persistent geotropic positional nystagmus after meningitis: evidence for light cupula. J Neurol Sci. 2017;379:279–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MB, Hong SM, Choi H, Choi S, Pham NC, Shin JE, Kim CH. The light cupula: an emerging new concept for positional vertigo. J Audiol Otol. 2018;22(1):1–5. doi: 10.7874/jao.2017.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beh SC. Horizontal direction-changing positional nystagmus and vertigo: a case of vestibular migraine masquerading as horizontal canal BPPV. Headache. 2018;58(7):1113–1117. doi: 10.1111/head.13356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lechner C, Taylor RL, Todd C, Macdougall H, Yavor R, Halmagyi GM, Welgampola MS. Causes and characteristics of horizontal positional nystagmus. J Neurol. 2014;261(5):1009–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun SY, Lee JY, Kwon EJ, Jung C, Yang X, Kim JS. Compression of both vertebral arteries during neck extension: a new type of vertebral artery compression syndrome. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):276–278. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi JY, Glasauer S, Kim JH, Zee DS, Kim JS. Characteristics and mechanism of apogeotropic central positional nystagmus. Brain. 2018;141(3):762–775. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi JY, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Glasauer S, Kim JS. Central paroxysmal positional nystagmus: characteristics and possible mechanisms. Neurology. 2015;84(22):2238–2246. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higashi-Shingai K, Imai T, Kitahara T, Uno A, Ohta Y, Horii A, Nishiike S, Kawashima T, Hasegawa T, Inohara H. Diagnosis of the subtype and affected ear of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo using a questionnaire. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(12):1264–1269. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.611535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li L, Liu JG, Wang ZW, Qi XK. Formulation and evaluation of diagnostic questionnaire for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;97(14):1061–1064. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2017.14.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HJ, Song JM, Zhong L, Yang X, Kim JS. Questionnaire-based diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2020;94(9):e942–e949. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feil K, Feuerecker R, Goldschagg N, Strobl R, Brandt T, von Muller A, Grill E, Strupp M. Predictive capability of an iPad-based medical device (medx) for the diagnosis of vertigo and dizziness. Front Neurol. 2018;9:29. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim EC, Park JH, Jeon HJ, Kim HJ, Lee HJ, Song CG, Hong SK. Developing a diagnostic decision support system for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo using a deep-learning model. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):633. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young AS, Lechner C, Bradshaw AP, MacDougall HG, Black DA, Halmagyi GM, Welgampola MS. Capturing acute vertigo: a vestibular event monitor. Neurology. 2019;92(24):e2743–e2753. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imai T, Ito M, Takeda N, Uno A, Matsunaga T, Sekine K, Kubo T. Natural course of the remission of vertigo in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2005;64(5):920–921. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152890.00170.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerber KA, Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Meurer WJ, Callaghan BC, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, McLaughlin TJ, Fendrick AM, Morgenstern LB. Use of BPPV processes in emergency department dizziness presentations: a population-based study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(3):425–430. doi: 10.1177/0194599812471633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Helminski JO, Zee DS, Janssen I, Hain TC. Effectiveness of particle repositioning maneuvers in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(5):663–678. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Brevern M, Seelig T, Radtke A, Tiel-Wilck K, Neuhauser H, Lempert T. Short-term efficacy of Epley's manoeuvre: a double-blind randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(8):980–982. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.085894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon CR, Gadoth N. Repeated vs single physical maneuver in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;110(3):166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, Furman JM, Baloh RW, Tusa RJ, Hain TC, Herdman S, Morrow MJ, Gronseth GS, Subcommittee QS, AAoN, Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70(22):2067–2074. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313378.77444.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh SY, Kim JS, Choi KD, Park JY, Jeong SH, Lee SH, Lee HS, Yang TH, Kim HJ. Switch to Semont maneuver is no better than repetition of Epley maneuver in treating refractory BPPV. J Neurol. 2017;264(9):1892–1898. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim JS, Oh SY, Lee SH, Kang JH, Kim DU, Jeong SH, Choi KD, Moon IS, Kim BK, Kim HJ. Randomized clinical trial for geotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;79(7):700–707. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182648b8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim JS, Oh SY, Lee SH, Kang JH, Kim DU, Jeong SH, Choi KD, Moon IS, Kim BK, Oh HJ, Kim HJ. Randomized clinical trial for apogeotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;78(3):159–166. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823fcd26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Honrubia V, Baloh RW, Harris MR, Jacobson KM. Paroxysmal positional vertigo syndrome. Am J Otol. 1999;20(4):465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yacovino DA, Hain TC, Gualtieri F. New therapeutic maneuver for anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol. 2009;256(11):1851–1855. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anagnostou E, Kouzi I, Spengos K. Diagnosis and treatment of anterior-canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol. 2015;11(3):262–267. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakayama M, Epley JM. BPPV and variants: improved treatment results with automated, nystagmus-based repositioning. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedersen MF, Eriksen HH, Kjaersgaard JB, Abrahamsen ER, Hougaard DD. Treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with the TRV reposition chair. J Int Adv Otol. 2020;16(2):176–182. doi: 10.5152/iao.2020.6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michael P, Munoz D, Tuma A, Garate M, Barraza C, Nunez M, Breinbauer HA. A Chair-based Abbreviated Repositioning Maneuver (ChARM) for fast treatment of posterior BPPV. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(8):2191–2198. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saberi A, Nemati S, Sabnan S, Mollahoseini F, Kazemnejad E. A safe-repositioning maneuver for the management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Gans vs. Epley maneuver; a randomized comparative clinical trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(8):2973–2979. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J, Zou S, Tian S. A prospective randomized controlled study of Li quick repositioning maneuver for geotropic horizontal canal BPPV. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138(9):779–784. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2018.1476778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ichijo H. A new treatment (the affected-ear-up 90 degrees maneuver) for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the lateral semicircular canal. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019;139(7):588–592. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2019.1609700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mandala M, Califano L, Casani AP, Faralli M, Marcelli V, Neri G, Pecci R, Scasso F, Scotto di Santillo L, Vannucchi P, Giannoni B, Dasgupta S, Bindi I, Salerni L, Nuti D. Double-blind randomized trial on the efficacy of the forced prolonged position for treatment of lateral canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2020 doi: 10.1002/lary.28981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Piromchai P, Eamudomkarn N, Srirompotong S, Ratanaanekchai T, Yimtae K. The efficacy of a home treatment program combined with office-based canalith repositioning procedure for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo—a randomized controlled trial. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(7):951–956. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.You J, Yu D, Yin S, Feng Y, Tan J, Song Q, Chen B. Complementary self-treatment for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2014;28(10):693–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beyea JA, Wong E, Bromwich M, Weston WW, Fung K. Evaluation of a particle repositioning maneuver web-based teaching module. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):175–180. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31814b290d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bromwich M, Hughes B, Raymond M, Sukerman S, Parnes L. Efficacy of a new home treatment device for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(7):682–685. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oh EH, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Choi SY, Choi KD, Choi JH. Incidence and clinical significance of positional downbeat nystagmus in posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Clin Neurol. 2019;15(2):143–148. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jeong SH, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Choi JY, Koo JW, Choi KD, Park JY, Lee SH, Choi SY, Oh SY, Yang TH, Park JH, Jung I, Ahn S, Kim S. Prevention of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with vit D supplementation: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeong SH, Lee SU, Kim JS. Prevention of recurrent benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09952-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen G, Zhao X, Yu G, Jian H, Li Y, Xu G. Otolith dysfunction in recurrent benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019;139(1):18–21. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2018.1562214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martinez Pascual P, Amaro Merino P. Otolithic damage study in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with vestibular evoked myogenic potentials. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2019;70(3):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoseinabadi R, Pourbakht A, Yazdani N, Kouhi A, Kamali M, Abdollahi FZ, Jafarzadeh S. The effects of the vestibular rehabilitation on the benign paroxysmal positional vertigo recurrence rate in patients with otolith dysfunction. J Audiol Otol. 2018;22(4):204–208. doi: 10.7874/jao.2018.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]