Abstract

Background and Aims

Fruit pedicels have to deal with increasing loads after pollination due to continuous growth of the fruits. Thus, they represent interesting tissues from a mechanical as well as a developmental point of view. However, only a few studies exist on fruit pedicels. In this study, we unravel the anatomy and structural–mechanical relationships of the pedicel of Adansonia digitata, reaching up to 90 cm in length.

Methods

Morphological and anatomical analyses included examination of stained cross-sections from various positions along the stalk as well as X-ray microtomography and scanning electron microscopy. For mechanical testing, fibre bundles derived from the mature pedicels were examined via tension tests. For establishing the structural–mechanical relationships, the density of the fibre bundles as well as their cellulose microfibril distribution and chemical composition were analysed.

Key Results

While in the peduncle the vascular tissue and the fibres are arranged in a concentric ring-like way, this organization shifts to the polystelic structure of separate fibre bundles in the pedicel. The polystelic pedicel possesses five vascular strands that consist of strong bast fibre bundles. The fibre bundles have a Young’s modulus of up to 5 GPa, a tensile strength of up to 400 MPa, a high density (>1 g cm−3) and a high microfibril angle of around 20°.

Conclusions

The structural arrangement as well as the combination of high density and high microfibril angle of the bast fibre bundles are probably optimized for bearing considerable strain in torsion and bending while at the same time allowing for carrying high-tension loads.

Keywords: Adansonia digitata L, pedicel, mechanical stresses, strengthening tissue, fibre characteristics, biomechanics, composite material, density, specific Young’s modulus, Angola

INTRODUCTION

The relationship of morphology and tissue properties to handle mechanical stresses has been studied for many different tissues including various types of wood or bast fibres. In contrast, only a few studies exist that have addressed fruit pedicels, most of them for commercial and breeding reasons, although studies on fruit pedicels would be very interesting from a mechanical point of view: load conditions differ because (1) fruits are usually hanging on a pedicel and (2) the fruit grows continuously resulting in a gradually changing load. With increasing fruit weight, mechanical elements in fruit pedicels are modified, and tensile strength rises (Schwarz, 1929). What type of adaptations are the pedicels developing and what are the safety factors for these arrangements? To investigate these questions, we investigated in detail the long pedicels of Adansonia digitata that hold huge fruits and compared them with other species. In tomato pedicels, Rančić et al. (2010) detected groups of fibres in the outer region of the pericycle and at the inner side of the inner phloem. They argued that additionally to these fibres, the xylem might have an important mechanical role to support much larger and heavier fruits. Apart from xylem, fibrous tissues, albeit only a few, were also detected for citrus (Bustan et al., 1995; Erner, 1996) and olive pedicel (Ganino et al., 2011). While these prosenchymatic cells provide an increased maximum tensile strength, isodiametric sclereids can contribute to peduncle bending stiffness and strength, which was shown for Malus (Horbens et al., 2014). The tropical tree Kigelia pinnata (syn. Kigelia africana subsp. africana) bears fruits with a weight of 2–5 kg and peduncles with a length of 3.5 m that are comparatively long and form reaction wood (Sivan et al., 2010). The only studied member of Malvaceae is Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, pedicels of whihc exhibit collenchymatous and parenchymatous tissues as well as a group of intermittent lignified fibre cells (Zahid et al., 2015). The aim of the present study, therefore, was to unravel adaptations in anatomy and structure–mechanics relationships of the remarkably long A. digitata pedicels according to the forces they face.

The baobab tree (A. digitata) is distributed widely in the savannahs of subsaharan Africa. Because of its peculiar bottle-shaped trunk, it is an iconic tree. Due to the manifold traditional uses of this tree, a large body of literature exists. For example, the use of stem fibres to produce clothing and other hand-crafted items is known from numerous African countries (Van Wyk et al., 1997; Wickens and Lowe, 2008; Gebauer et al., 2014). The species prefers savannahs with perennially high temperatures, low precipitation and long drought periods (Wickens and Lowe, 2008). Its inflorescence shows just one single flower usually appearing at the beginning of the rainy season and subsequently forming the fruits, which hang on long pedicels and are defined as ‘amphisarcum’. The pericarp forms a dry crust outwards and inwards with one or more fleshy layers (Stuppy, 2004). The flower stalk consists of a proximal peduncle and a distal pedicel demarcated by a distinct joint (Baum, 1995). The pedicel is polystelic with five vascular strands. Each strand exhibits a central lacunose medulla that is surrounded by a considerable amount of woody and fibrous cells (Walpers, 1852; Dumont, 1889), which provides the mechanical support to the whole structure. Several authors have described the pronounced differences between fruit size and pedicel length across Africa (Wickens, 1982; Gebauer et al., 2002, 2014). They can reach a length up to 20 cm in southern and eastern Africa, but can be up to 90 cm long in West Africa and Angola. Fruit weights vary from 50 g in Sudan to at least 1400 g in Angola, which represents a considerable load for the pedicel. Furthermore, dynamic loads under oscillating wind speed and predator pressure (e.g. elephants dragging the fruits) need to be tolerated.

Malvaceae, including A. digitata, are an important plant family due to numerous species having strong bast fibres in their stems. As plant fibres are a major component of many commercial tissues and other products, a large number of species have been studied and their fibres biomechanically characterized (Brink and Achigan-Dako, 2012). However, except for the recent description of secondary phloem fibres in the stems of A. digitata and their arrangement into tangential bands (Kotina et al., 2017), no material characterization of these traditionally used fibres is available.

Here, we analysed the mechanics, especially of the fibres of the pedicel of A. digitata collected in Angola which are known to be the largest baobab fruits. In addition, microfibril angles of the fibres were measured by wide-angle X‐ray diffraction. The transition zone between branch and pedicel was analysed by X-ray microtomography (µ-CT). Furthermore, the chemical composition of fibres was studied to address the following questions: (1) How do morphology and varying fibre properties correlate with each other in counteracting the mechanical stresses the pedicel has to withstand? (2) Are fibre characteristics comparable to values from baobab stems? (3) Is the distribution of strengthening tissue comparable to other pedicels such as in Malus domestica or Kigelia pinnata? (4) How is the transition from peduncle to pedicel formed?

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Material

Bast fibres of the stem and the pedicel of Adansonia digitata L. were analysed. In botany, the term ‘fibre’ refers to a single cell whose length exceeds its width many times (Sfiligoj Smole et al., 2013). In the present study, the term ‘fibre’ is applied to bundles of individual fibre cells in line with DIN EN ISO 6938: 2015-01 (https://www.beuth.de/de/norm/din-en-iso-6938/225357042). In July 2014 as well as in November and February 2015, fruit stalks in different states of maturity were collected in the provinces Luanda and Bengo, Angola. Fibres were isolated from the mature and dried pedicels via a natural retting process and subsequently air-dried. Further fresh stalks were preserved in 70 % ethanol. Stem fibre samples of A. digitata were collected in 2017 in Sudan employing the same procedure as used for the fibres of the fruit stalks and provided by Jens Gebauer. Additionally, flower stalks of A. digitata were made available by the ‘Palmengarten’ of Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Morphological and anatomical analyses

The morphology and anatomy of A. digitata stalks were studied using ethanol-preserved samples. Cross-sections from positions along the stalk were obtained by using a razor blade according to the classification of Fig. 1B into six segments from A (peduncle) to F (near the fruit). The samples were stained with Safranin/Astrablue and analysed by light microscopy in reflection mode (SZX16, Olympus Corporation, Japan). Safranin and Astrablue are indicators of lignin and cellulose, respectively. The proportions of bast fibres were determined using the area calculation function of the software ‘cellSens’ (Olympus Corporation). Two cross-sectional areas of the stalks near the flower were similarly examined. Furthermore, the transition zone between peduncle and pedicel for one stalk was analysed by µ-CT. Finally, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Zeiss Supra 40VP, Germany) was used to obtain a more precise view of the secondary phloem.

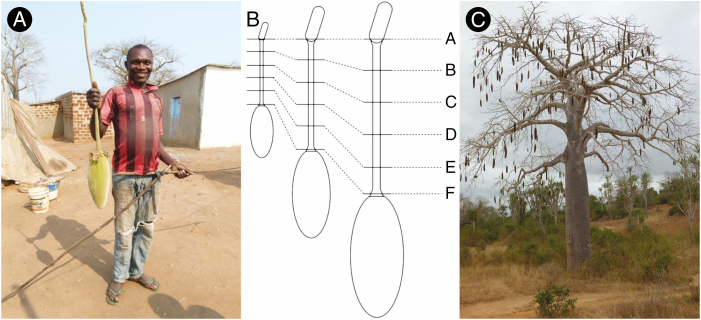

Fig. 1.

(A) Freshly cut Adansonia digitata fruit stalk from Angola; (B) arrangements of cross-sections for anatomical studies; (C) A. digitata tree during dry season in the Kissama National Park, Angola.

For µ-CT scans, one mature baobab peduncle/pedicel transition zone in a 70 % EtOH solution was successively transferred into a 70, 80, 90 and finally 100 % MeOH solution and incubated in each solution for 24 h. It was then dissected into nine small pieces with a fine razor blade. Each sample was dried in a critical-point dryer CPC030 (BALTEC AG, Liechtenstein) following standard protocol. Samples were consecutively fixed on a sample holder and scanned in a SkyScan 1272 µ-CT scanner (Bruker microCT, Kontich/Belgium) at a current of the X-ray tube of 200 µA and a voltage of 50 kV. Only scans of the two most apical samples were further evaluated. For the most apical sample, the following parameters were chosen: image pixel size 11 µm, rotation step 0.4°, frame averaging value of 8, 360° rotation and random movement correction. The second sample (directly below) was scanned with an image pixel size of 8.5 µm, a 180° rotation and otherwise identical parameters to the most apical sample. Image reconstruction was performed in the software NRecon (Version 1.7.1.0, Bruker microCT) and images were visualized – in the trans-axial plane and as orthoslice images – via DataViewer (Version 1.5.4.0, Bruker microCT). The orthoslice images are shown with inverted greyscale to enhance contrast and visibility of the tissues in the longitudinal direction (Hesse et al., 2019).

For determination of the cell length of the bast fibres of the pedicel and the stem, they were macerated twice for 6 h in a solution of hydrogen peroxide and glacial acetic acid (Frey et al., 2018) and then measured. Furthermore, the weight of fully grown but still unripe fruits was determined using a precision balance in order to characterize the load acting on the pedicel. Fruits were dried to constant weight in a drying cabinet and later measured again to determine the water content.

Chemical analyses

Chemical analyses were performed using 5 g of fibre material of one mature pedicel. Cellulose contents were determined according to Kuerschner and Hoffer (1931). Lignin contents were investigated according to the modified method T222 om-02 of TAPPI (Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry). Holocellulose contents were analysed according to Wise (1946, modified). Because only very little material was available for this analysis it could only be conducted once.

Density measurements

According to DIN EN ISO 1183-1:2013-04 (https://www.beuth.de/de/norm/din-en-iso-1183-1/151803335), fibre density was determined using a precision balance and a pycnometer with an accuracy of 0.01 g and 0.05 mL. An initial test was conducted with 25 samples without any position sensing (relative position along the pedicel), while in a second examination, three samples for each position and in addition in dry and wet conditions were tested.

Mechanical analyses

The biomechanical properties of the extracted fibre bundles with a length of ~2 cm (test length 5 mm) derived from mature pedicels were examined via tension tests using a universal testing machine BZ2.5/TS1S (Zwick/Roell GmbH, Germany) equipped with a 50-N load cell. The samples were tested at a displacement rate of 2 mm min–1 (position-controlled). The tension tests were performed at constant room temperature (22 °C) and a relative humidity of 30–40 %. Preliminary tests were conducted with 100 fibre samples from one pedicel to optimize the test setup. Based on these results, additional tests were performed with ten samples derived from the stem, 14 samples derived from the pedicel near the branch and ten samples derived from the pedicel near the fruit. For testing close to natural conditions, we furthermore soaked ten fibres of each position along the pedicel in water for 1 h. In total, 54 samples were tested. Stress–strain diagrams were calculated with the testXpert software (Zwick/Roell GmbH). Young’s moduli in tension were obtained using the calculated values of the cross-sectional areas and the corresponding slopes of the linear part between 20 and 40 % of the average strength derived from the stress–strain curve. The fibres exhibited an almost rectangular cross-section. Therefore, thickness and width of the samples were examined by light microscopy (Carl Zeiss Axioskop 2, Germany) and taken to calculate the individual cross-sectional areas. Tensile strength and breaking strain were likewise determined using the compiled data.

X-ray diffraction

Cellulose microfibril orientation [microfibril angle (MFA)] of all mechanically tested fibre bundles from the pedicel and of three fibre bundles from the stem was determined by wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) with a Nanostar (Bruker AXS, Germany). CuKα radiation with a wavelength of 1.54 Å was used. The X-ray beam diameter was ~300 µm and the sample–detector distance was set to 90.9 mm. For each sample, one diffraction image was taken. For cellulose orientation analysis, azimuthal intensity profiles of the (200)-Bragg peak of cellulose were generated from the diffraction images by radial integration with the contribution of amorphous parts being removed by baseline subtraction. These profiles were then fitted with simulated azimuthal intensity profiles, which were generated by a combination of two Gaussian distributions of microfibrils considering the cell geometry of the fibre cells according to Rüggeberg et al. (2013). The fitted azimuthal profiles were then used to determine microfibril angles.

RESULTS

Morphological analyses

At the beginning of stalk development, three bracteoles cover the flower bud, but are shed soon, leaving three scars as remaining marks (Fig. 2A–C). According to our observation, the stalk reaches its maximum length before the flower bud opens. At the mature stage, it develops a length up to 90 cm and consists of a proximal peduncle, which occupies only about one-tenth of the entire length and the long pendulous pedicel (Fig. 2D–E). The two organs grow simultaneously in length and diameter. During development from the flower to the mature fruit, the proportion of fibres in the segments increases to different degrees. While the fibre content near the branch increases by only 46 %, the increase near the fruit amounts to 540 % (Table 1). Nevertheless, in the fully developed mature state the proportion of fibres in the stalk segments near the branch and near the fruit are the same. This different developmental pattern might be explained simply by the steadily growing fruit weight influencing the apical pedicel differentiation whereas the fibre connection between branch and stalk is developed much earlier during flower production. The diameter of the mature pedicel differs along its length, although the proportion of fibres remains roughly the same, on average 36 % (Table 2).Weight analysis revealed that during ripening fruits lose more than two-thirds of their weight due to the strong dehydration.

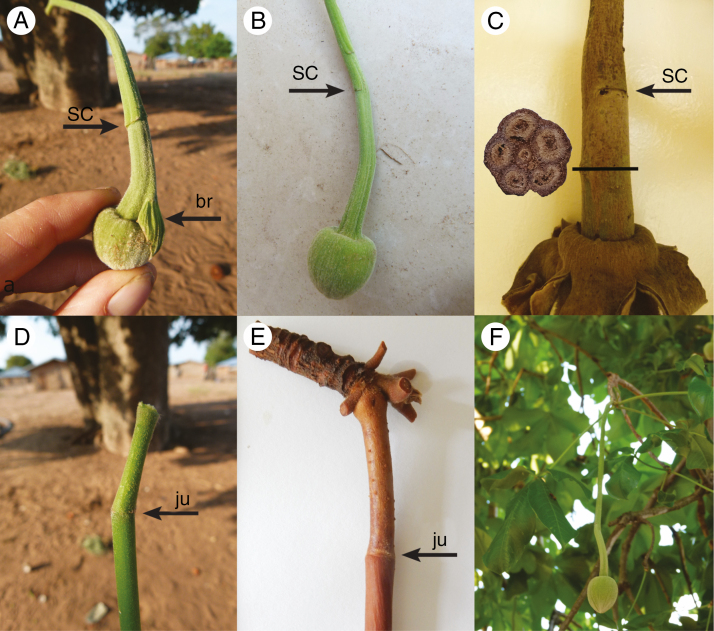

Fig. 2.

Morphological characteristics of Adansonia digitata inflorescence: (A) young flower bud with bracteoles arising on the pedicel; (B) scars of the caducous bracteoles near the flower bud; (C) the same but on a mature pedicel and cross-section of dry mature pedicel near fruit; (D) junction between peduncle and pedicel from a young inflorescence; (E) junction between peduncle and pedicel from a mature inflorescence; (F) flower bud pending from the tree on its long peduncle/pedicel. Abbreviations: sc = scar of bracteole, br = bracteole, ju = junction.

Table 1.

Proportion of fibres near the branch and near the fruit during different stages of maturity of the pedicel of Adansonia digitata. Stage I is defined as pedicel during flowering, stage IV is the full-grown pedicel.

| Near branch (A) | Near fruit (F) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of maturity | Cross sectional area (mm2) | Relative proportion of fibres (%) | Stage of maturity | Cross-sectional area (mm2) | Relative proportion of fibres (%) |

| I | 38.5 | 24 | I | 33.4 | 5 |

| II | 49.1 | 27 | II | 49.5 | 7 |

| III | 151.6 | 38 | III | 259.1 | 30 |

| IV | 537.8 | 35 | IV | 579.7 | 32 |

Table 2.

Proportion of fibres within the cross-sectional areas along one pedicel of Adansonia digitata, starting near the branch (A) to the fruit (F). Linear regression analysis showed a clear positive correlation of total cross-sectional area and fibre area along the stalk axis (P = 0.0003).

| Segment from branch to fruit | Cross-sectional area (mm2) | Area of fibres (mm2) | Relative proportion of fibres (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 537.8 | 190.4 | 35 |

| B | 154.3 | 64.6 | 42 |

| C | 155.8 | 62.7 | 40 |

| D | 195.9 | 77.4 | 40 |

| E | 488.0 | 145.8 | 30 |

| F | 579.7 | 187.7 | 32 |

Anatomical analyses

The cross-section of a mature pedicel reveals the following tissues (Fig. 3). The outer layer is composed of the epidermis and a cortical parenchyma. The next layer consisting of parenchymatous tissue with scattered mucilage ducts then encloses the vascular strands. Each of the five strands has a central medulla with loose tissue and therein partially embedded mucilage ducts.

Fig. 3.

Cross-section of a mature Adansonia digitata pedicel: (A) Near the branch; (B) near the fruit. Abbreviations: s: sclerenchyma cap, b: bast, c: cambium, x: xylem, e: epidermis, p: cortical parenchyma, m: mucilage ducts. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Besides the five large strands, several very small vascular strands are observed. The central medulla of each strand is surrounded by secondary xylem, cambium and secondary phloem (Fig. 3B). Xylem rays and bast rays, respectively, separate these vascular tissues. The secondary phloem is divided into hard bast and soft bast (Fig. 4). By means of the retting process, only the hard bast fibres remain. As already shown in previous studies (Lautenschläger et al., 2016; Senwitz et al., 2016), the thickness of the cell wall increases from the cambium to the outer regions of the secondary phloem with the result that the fibres exhibit different degrees of density. The bast fibre cells in the pedicel are 1.6 ± 0.133 mm long (mean ± s.d.). The stem bast fibres are 2.0 ± 0.203 mm long.

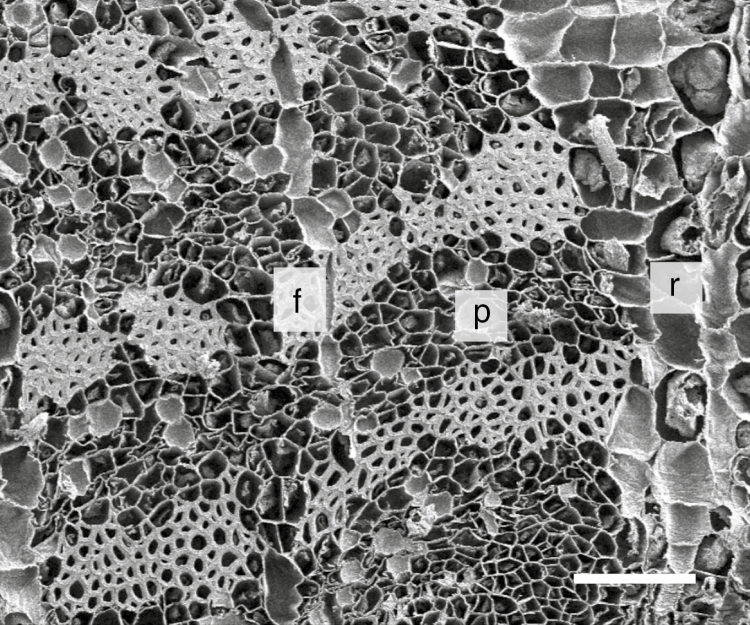

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron micrograph of the bast region. Abbreviations: f: fibre bundles, p: phloem, r: ray. Scale bar = 100 µm.

During flower development, secondary phloem is still not developed but the primary phloem shows an accumulation of sclerenchymatous cells in the outer part (sclerenchyma cap). Xylem vessels are starting to lignify. In the flower pedicel, the proportion of fibres in the entire cross-sectional area is much lower than in the mature pedicel (Table 1).

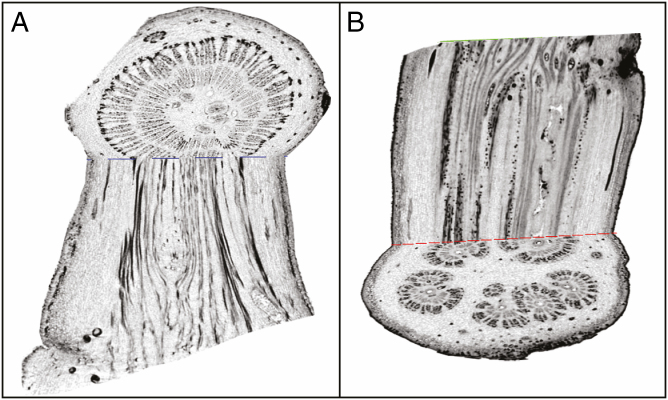

Transition zone between peduncle and pedicel

The transition zone between the peduncle and the pedicel reveals a peculiar structure, as can be seen by light microscopy (Fig. 5) and µ-CT images (Fig. 6). While in the peduncle the vascular tissue and the fibres are arranged in a ring-like cylindrical structure, this organization shifts into the polystelic structure of the pedicel (Metcalfe and Chalk, 1957; Wickens and Lowe, 2008). The polystelic pedicel possesses five vascular strands (Walpers, 1852), a feature which can be particularly seen in dried specimens due to desiccation of the parenchyma (Fig. 2C). This pattern can be observed even in the earliest stage of flower stalk development. Furthermore, the number of strands can vary along the pedicel as they can merge into one strand or branch into two.

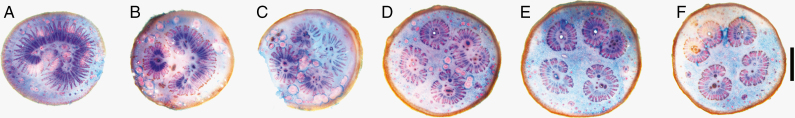

Fig. 5.

Cross-section of Adansonia digitata covering the transition zone from peduncle (A and B) to pedicel (C–F; 1 cm from a to f; using light microscopy, stained with Astrablue–Safranin. Scale bar = 2 mm.

Fig. 6.

Orthoslice reconstruction of an X-ray microtomography scan through a basal (A) and apical (B) part of a baobab peduncle/pedicel transition zone. (A) Course of longitudinal phloem tissue during the beginning of stelar reorientation. (B) Course of longitudinal phloem and xylem tissue during division of vascular bundles. Greyscale has been inverted for better visualization of tissues.

Chemical composition, density and microfibril angle

The bast fibres consist of 48 % cellulose, 29 % hemicelluloses and 14 % lignin. Compared to other bast fibres, the value for lignin is rather high (Table 3). Bast fibre density differs from 0.58 ± 0.02 g cm–3 in the stem to 1.28 ± 0.11 g cm–3 in the pedicel near the fruit (Table 4). Microfibril angles were determined for some of the mechanically tested fibres. Similar angles in the range 20–22° were observed for fibres of all three positions (pedicel near fruit and branch and stem fibres; Table 4).

Table 3.

Chemical composition and density of bast fibres from the mature pedicel.

| Species | Extract content (%) | Lignin content (%) | Cellulose content (%) | Hemicellulose content (%) | Holocellulose content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. digitata | 2.13 | 14.07 | 48.20 | 28.65 | 76.85 |

| Jutea | 12–13 | 61–71 | 14–20 | ||

| Flaxa | 2.2 | 71 | 18.6–20.6 | ||

| Hempa | 10 | 68 | 15 |

aData republished from Faruk et al. (2012).

Table 4.

Mechanical properties and microfibril angle of Adansonia digitata stem and fruit pedicel fibres in dry condition. MFA = microfibril angle. Note: values are means ± s.d. Same letters and asterisks respectively indicate significant differences (Tukey-Kramer test, P ˂ 0.05).

| Young’s modulus (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Breaking strain (%) | MFA (°) | Density (g cm–3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry fibres | |||||

| Stem | 1699 ± 588a,b | 122 ± 50c | 9.3 ± 3.8d | 21 ± 0 | 0.58 ± 0.02f,g |

| Near branch | 5090 ± 1934a,* | 408 ± 173c | 9.6 ± 1.7e | 21 ± 3 | 1.05 ± 0.11f |

| Near fruit | 4755 ± 1632b,** | 272 ± 100c | 6.2 ± 1.2d,e | 20 ± 3 | 1.28 ± 0.11g |

| Wet fibres | |||||

| Stem | – | – | – | – | 0.61 ± 0.01k,l |

| Near branch | 2499 ± 585h,* | 299 ± 112i | 11.6 ± 2.7j | – | 1.05 ± 0.06k |

| Near fruit | 2176 ± 663h,** | 169 ± 80i | 7.5 ± 2.5j | – | 1.10 ± 0.20l |

Mechanical analyses

The mechanical properties of the fibre samples were determined via tension tests that revealed differences between pedicel and stem fibres, between fibres of different position within the pedicel as well as between fibres with different treatments (Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2).

Fibres from near the branch of A. digitata pedicels had a Young’s modulus of 5.1 ± 1.9 GPa, which is similar to that of fibres from near the fruit (4.8 ± 1.6 GPa). Fibres hydrated before tension tests had lower Young’s moduli of 2.5 ± 0.6 GPa for samples near the branch and 2.2 ± 0.7 GPa for samples near the fruit. Stem fibre samples, by contrast, had a Young’s modulus of 1.7 ± 0.6 GPa. These values are significantly lower than those obtained for the pedicel fibres (Table 4).

Fibres from near the branch of A. digitata pedicels had the highest tensile strength of 408 ± 173 MPa, which decreased after hydrating the samples to 300 ± 106 MPa. Fibres from near the fruit of A. digitata pedicels had a significantly lower tensile strength of 272 ± 100 MPa but a similar relative decrease after wetting (169 ± 80 MPa). Stem fibre samples had a tensile strength of 122 ± 50 MPa.

Stem fibre samples exhibited a breaking strain of 9.3 ± 3.8 %. The breaking strain of untreated, dry fibres from near the branch of A. digitata pedicels was higher, 9.6 ± 1.7 %, than of fibres from near the fruit, 6.2 ± 1.2 %, but here after wetting an increase was observed (11.6 ± 2.7 % or 7.5 ± 2.5 %). The high standard deviation may be explained by the increasing cell wall thickness with distance from the cambium, which results in different mechanical properties.

Discussion

Only a few pedicels such as those of tomato (Rančić et al., 2010), Kigelia (Sivan et al., 2010) or apple (Horbens et al., 2014) have been studied so far. Our study shows that the Adansonia fruit pedicel has a fundamentally different structure than these previously investigated pedicels. Its mechanically important tissues are arranged in five main bundles and consist of strong bast fibres each surrounding a small wooden core embedded in a rather distinct parenchymatous tissue. Strong bast fibres are typical for Malvaceae whose stems do not possess reaction wood. Furthermore, we could not detect sclereids. The arrangement in single strands may result in high torsional flexibility. Its unusual organization as well as its ability to be more flexible resembles the internal structure of some lianas and most probably prevents xylem vessels from becoming damaged under bending and torsion loads (Rowe et al., 2004; Rowe and Speck, 2014). This is also in line with the lower cross-sectional area in the middle part of the pedicel resulting in higher bending and torsion flexibility.

The transition from the cylindrical arrangement of the strengthening bast fibres in the branch to the polystelic structure of single strands in the pedicel occurs in the peduncle and was documented in detail using µ-CT. Both structures can be considered optimized for their specific mechanical functions, i.e. carrying heavy fruits and facing different kinds of static and dynamic loading by fruit weight, wind and feeding animals.

In terms of static loading, the pedicels of baobab trees represent rope-like structures with an increasing end load caused by the growing fruit inducing increasing tensile stress. However, with a cross-sectional area of the load-bearing fibres of ~60 mm2 for the lowest diameter of the pedicel and an average strength >200 MPa, a load of at least 12 kN could be (theoretically) sustained by the pedicel under static loads. This would result in safety factors of nearly 1000 for this load situation. While this simplified calculation assumes continuity of the load-bearing tissue and excludes any weakening due to imperfections and discontinuities, it can be assumed that the tensile stress induced by the fruit does not represent a critical load for the pedicel.

Structural analysis of the bast fibres of the pedicel revealed a combination of a high density (>1 g cm−3) and a microfibril angle of around 20°. The density of the pedicel fibres near the branch is comparable to that of other plant fibres such as the bast fibres of hemp (Cannabis sativa), or flax (Linum usitatissimum) or the leaf fibres of sisal (Agave sisalana), while the density of the fibres near the fruit is slightly lower. The microfibril angle of 20° found for all analysed baobab fibres is higher than that of other bast fibres such as flax or hemp (Mwaikambo and Ansell, 2006), but comparable to those of sisal fibres (Mukherjee and Satyanarayana, 1984), for talipot fibres originating from the leaf stalks of the palm Corypha umbraculifera (Satyanarayana et al., 1986) and for juvenile wood (Donaldson, 2008; Özparpucu et al., 2017, 2018). Higher values of 30–40° are found for the leaf stalk fibres from the palmyrah palm (Borassus flabellifer) (Satyanarayana et al., 1986) and for coir fibres (Cocos nucifera) (Mwaikambo and Ansell, 2006).

The stiffness and strength of a tissue parallel to the fibre direction (L-direction) are positively correlated with density (Gibson, 2005) and negatively correlated with microfibril angle (Cave, 1968, 1969; Reiterer et al., 1999). Breaking strain and, in many cases, toughness are, however, often positively correlated with microfibril angle (up to around 30°) (Reiterer et al., 1999, 2001).

With a strength of up to 400 MPa and a stiffness of 4.8 GPa, the baobab pedicel fibres have lower values compared to bast fibres such as hemp or flax fibres (Biagiotti et al., 2004; Mwaikambo, 2006) with a strength of up to 1 GPa and a stiffness beyond 30 GPa. This can be explained by the comparatively high microfibril angle of the baobab pedicel fibres. Strength values are similar to those of sisal and talipot fibres of around 500 and 200 MPa with comparable microfibril angle, respectively (Satyanarayana et al., 1986), while stiffness values of the pedicel fibres (4.8 ± 1.9 GPa) are lower than those of talipot and sisal fibres with values between 10 and 20 GPa.

The biomechanical properties of the extracted fibre bundles with a length of ~2 cm (test length 5 mm) derived from the mature pedicels were examined. Mechanical tests revealed high breaking strains of more than 10 %, which may be explained by the microfibril angle of 20°. Fibres near the fruit showed lower breaking strains of around 6 %, which may explain the lower strength values despite similar stiffness values compared to the fibres near the branch. The high microfibril angle and high extensibility of the baobab pedicel fibres indicates an optimization towards flexibility at lower hierarchical levels of the pedicel. Similar adaptation mechanisms towards flexibility may be found for the fibres of the petioles (leaf stalks) of the talipot and palmyrah palms and for juvenile wood. Both tissues show similar or even higher microfibril angles compared to the baobab pedicel fibres and correspondingly high strain values. The leaf stalks are exposed to considerable bending and torsional deformation by the wind-induced swaying of the large leaves, while juvenile wood bears the wind-induced bending of the thin stems (Lichtenegger et al., 1999).

The combination of high density and comparatively high microfibril angle further results in high toughness, which may be important for dynamic load situations such as wind exposure, but potentially also for withstanding dragging of the fruits by elephants prior to maturity of the fruits. The latter may result on the one hand in torsional loads exceeding those induced by the wind, but on the other hand, in tensile forces well beyond those exerted by the fruit and could explain the seemingly very high safety factors. This specific combination of tissue arrangement and fibre cell wall setup in baobab pedicels represents an iconic example of an adaptation to specific mechanical loading situations made possible by the hierarchical organization of plant materials (Fratzl and Weinkamer, 2007). It is also a valuable example in demonstrating convergent structural adaption to a particular mechanical loading situation across plant families.

CONCLUSION

From an anatomical point of view, the Adansonia digitata pedicel shows a unique organization and formation of tissues that is comparable to that of some liana cross-sections. The structural arrangement, composed of separate bundles, is probably optimized for bearing considerable bending and torsion loads without failure and at the same time allowing for carrying high tension loads. This structure is developed by the gradual transition of the strengthening tissues from a cylindrical structure in the branch to a polystelic one in the pedicel. At the bast fibre level we were able to demonstrate a high safety factor. The fibres exhibit significantly higher values of density and Young’s modulus than the stem fibres. The requirements on the different plant parts are therefore fulfilled as in the stem and branch stiffness is ensured while in the pedicel torsion may play a considerable role. Due to the high microfibril angle, bast fibres are adapted to high breaking strains, which again highlights its flexibility.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Fig. S1: Stress–strain diagrams for the different test settings of Adansonia digitata fibres. Fig. S2: Different test settings of Adansonia digitata fibres.

Acknowledgements

These published results were obtained in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional da Biodiversidade e Áreas de Conservação (INBAC) of the Ministério do Ambiente da República de Angola. We thank the administration and the staff of the University of Kimpa Vita in Uíge for logistical support during our stay in Angola. We are grateful to Jens Gebauer for providing stem fibres of Adansonia digitata from Sudan as well as to the Palmgarten Frankfurt am Main for providing flower samples. The chemical analyses were performed at the Institute of Wood and Plant Chemistry of the Technische Universität Dresden in Germany. We thank Martin Horstmann for his efforts to improve the orthoslice images as well as the reviewers for their very valuable recommendations. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

K.B. and T.S. acknowledge funding by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) as part of the Transregional Collaborative Research Centre (SFB/Transregio) 141 ‘Biological Design and Integrative Structures’.

LITERATURE CITED

- Baum DA. 1995. Systematic revision of Adansonia (Bombacaceae). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 82: 440–471. [Google Scholar]

- Biagiotti J, Puglia D, Kenny JM. 2004. A review on natural fibre-based composites-Part I. Journal of Natural Fibers 1: 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Brink M, Achigan-Dako EG. 2012. Fibres. Wageningen: PROTA Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bustan A, Erner V, Goldschmidt EE. 1995. Interactions between developing citrus fruits and their supportive vascular system. Annals of Botany 76: 657–666. [Google Scholar]

- Cave ID. 1968. The anisotropic elasticity of the plant cell wall. Wood Science and Technology 2: 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cave ID. 1969. The longitudinal Young’s modulus of Pinus radiata. Wood Science and Technology 3: 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson L. 2008. Microfibril angle: measurement, variation and relationships - a review. IAWA Journal 29: 345–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont A. 1889. Recherches sur l’anatomie comparée des Malvacées, Bombacées, Tiliacées, Sterculiacées. Annales des sciences naturelles 7: 129–246. [Google Scholar]

- Erner Y. 1996. Morphology and anatomy of stems and pedicels of spring flush shoots associated with citrus fruit set. Annals of Botany 78: 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Faruk O, Bledzki AK, Fink HP, Sain M. 2012. Biocomposites reinforced with natural fibers: 2000–2010. Progress in Polymer Science 37: 1552–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Fratzl P, Weinkamer R. 2007. Nature’s hierarchical materials. Progress in Materials Science 52: 1263–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Frey M, Widner D, Segmehl JS, Casdorff K, Keplinger T, Burgert I. 2018. Delignified and densified cellulose bulk materials with excellent tensile properties for sustainable engineering. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 10: 5030–5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganino T, Rapoport HF, Fabbri A. 2011. Anatomy of the olive inflorescence axis at flowering and fruiting. Scientia Horticulturae 129: 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer J, Assem A, Busch E, et al. 2014. Der Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.): Wildobst aus Afrika für Deutschland und Europa?! Erwerbs-Obstbau 56: 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer J, El-Siddig K, Ebert G. 2002. Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.): a review on a multipurpose treewith promising future in the Sudan. Gartenbauwissenschaft 67: 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson LJ. 2005. Biomechanics of cellular solids. Journal of Biomechanics 38: 377–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse L, Bunk K, Leupold J, Speck T, Masselter T. 2019. Structural and functional imaging of large and opaque plant specimens. Journal of Experimental Botany 70: 3659–3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbens M, Feldner A, Höfer M, Neinhuis C. 2014. Ontogenetic tissue modification in Malus fruit peduncles: the role of sclereids. Annals of Botany 113: 105–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotina EL, Oskolski AA, Tilney PM, Wyk B-EV. 2017. Bark anatomy of Adansonia digitata L. (Malvaceae). Adansonia 39: 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kuerschner K, Hoffer A. 1931. Eine neue quantitative Cellulosebestimmung. Chemiker Zeitung 17: 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschläger T, Kempe A, Neinhuis C, Wagenführ A, Siwek S. 2016. Not only delicious: papaya bast fibres in biocomposites. BioResources 11: 6582–6589. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenegger H, Reiterer A, Stanzl-Tschegg SE, Fratzl P. 1999. Variation of cellulose microfibril angles in softwoods and hardwoods-a possible strategy of mechanical optimization. Journal of Structural Biology 128: 257–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe CR, Chalk L. 1957. Anatomy of the dicotyledons: Leaves, stem, and wood in relation to taxonomy with notes on economic uses. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee PS, Satyanarayana KG. 1984. Structure and properties of some vegetable fibres. Journal of Materials Science 19: 3925–3934. [Google Scholar]

- Mwaikambo LY. 2006. Review of the history, properties and application of plant fibres. African Journal of Science and Technology 7: 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Mwaikambo LY, Ansell MP. 2006. Mechanical properties of alkali treated plant fibres and their potential as reinforcement materials II. Sisal fibres. Journal of Materials Science 41: 2497–2508. [Google Scholar]

- Özparpucu M, Gierlinger N, Burgert I, et al. 2018. The effect of altered lignin composition on mechanical properties of CINNAMYL ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE (CAD) deficient poplars. Planta 247: 887–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özparpucu M, Rüggeberg M, Gierlinger N, et al. 2017. Unravelling the impact of lignin on cell wall mechanics: a comprehensive study on young poplar trees downregulated for CINNAMYL ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE (CAD). The Plant Journal 91: 480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rančić D, Quarrie SP, Pećinar I. 2010. Anatomy of tomato fruit and fruit pedicel during fruit development. Microscopy: Science, Technology, Applications and Education 2: 851–861. [Google Scholar]

- Reiterer A, Lichtenegger H, Fratzl P, Stanzl-Tschegg SE. 2001. Deformation and energy absorption of wood cell walls with different nanostructure under tensile loading. Journal of Materials Science 36: 4681–4686. [Google Scholar]

- Reiterer A, Lichtenegger H, Tschegg S, Fratzl P. 1999. Experimental evidence for a mechanical function of the cellulose microfibril angle in wood cell walls. Philosophical Magazine A-Physics Of Condensed Matter Structure Defects And Mechanical Properties 79: 2173–2184. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe N, Isnard S, Speck T. 2004. Diversity of mechanical architectures in climbing plants: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 23: 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe NP, Speck T. 2015. Stem biomechanics, strength of attachment, and developmental plasticity of vines and lianas. Ecology of Lianas 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rüggeberg M, Saxe F, Metzger TH, Sundberg B, Fratzl P, Burgert I. 2013. Enhanced cellulose orientation analysis in complex model plant tissues. Journal of Structural Biology 183: 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayana KG, Ravikumar KK, Sukumaran K, Mukherjee PS, Pillai SGK, Kulkarni AG. 1986. Structure and properties of some vegetable fibres. Journal of Materials Science 21: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz W. 1929. Zur physiologischen Anatomie der Fruchtstiele schwerer Früchte. Planta 8: 185–251. [Google Scholar]

- Senwitz C, Kempe A, Neinhuis C, Mandombe JL, Branquima MF, Lautenschläger T. 2016. Almost forgotten resources – biomechanical properties of traditionally used bast fibers from northern Angola. BioResources 11: 7595–7607. [Google Scholar]

- Sfiligoj Smole M, Hribernik S, Stana Kleinschek K, Kreže T. 2013. Plant fibres for textile and technical applications. Advances in Agrophysical Research: 369–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sivan P, Mishra P, Rao KS. 2010. Occurrence of reaction xylem in the peduncle of Couroupita guianensis and Kigelia pinnata. IAWA Journal 31: 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stuppy W. 2004. Glossary of seed and fruit morphological terms. Kew: Seed Conservation Department, Royal Botanic Gardens. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk BE, Oudtshoorn BV, Gericke N. 1997. Medicinal plants of South Africa. Pretoria: Briza. [Google Scholar]

- Walpers G. 1852. Über Adansonia digitata. Linn. Botanische Zeitung 10: 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens GE. 1982. The baobab: Africa’s upside-down tree. Kew Bulletin 37: 173. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens GE, Lowe P. 2008. Baobabs: pachycauls of Africa, Madagascar, and Australia. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wise LE. 1946. Chlorite holocellulose, its fractionation and bearing on summative wood analysis and on studies on the hemicelluloses. Paper Trade 122: 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid H, Rizwani GH, Khalid L, Shareef H. 2015. Comparative profile of Hibiscus schizopetalus (Mast) hook and Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. (Malvaceae). Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 5: 131–136. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.