Abstract

Medical diagnosis has seen a tremendous advancement in the recent years due to the advent of modern and hybrid techniques that aid in screening and management of the disease. This paper figures a predictive model for detecting neurodegenerative diseases like glaucoma, Parkinson’s disease and carcinogenic diseases like breast cancer. The proposed approach focuses on enhancing the efficiency of adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) using a modified glowworm swarm optimization algorithm (M-GSO). This algorithm is a global optimization wrapper approach that simulates the collective behavior of glowworms in nature during food search. However, it still suffers from being trapped in local minima. Hence in order to improve glowworm swarm optimization algorithm, differential evolution (DE) algorithm is utilized to enhance the behavior of glowworms. The proposed (DE–GSO–ANFIS) approach estimates suitable prediction parameters of ANFIS by employing DE–GSO algorithm. The outcomes of the proposed model are compared with traditional ANFIS model, genetic algorithm-ANFIS (GA-ANFIS), particle swarm optimization-ANFIS (PSO-ANFIS), lion optimization algorithm-ANFIS (LOA-ANFIS), differential evolution-ANFIS (DE-ANFIS) and glowworm swarm optimization (GSO). Experimental results depict better performance and superiority of the DE–GSO–ANFIS over the similar methods in predicting medical disorders.

Keywords: Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system, Differential evolution, Glowworm swarm optimization, Neuro-ophthalmic disorders

Introduction

Clinical datasets are widely used in predicting and managing many diseases like glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, Parkinson’s disease, breast cancer, etc. Healthcare applications find extensive use of data mining approaches in analyzing the trends in subject’s records leading to overall improvement in healthcare. Prediction from the data mining process leads to systematic support in enhancing decision making [1]. The clinical data of the patients possess uncertainty in many ways, and hence, complete decision making with certainty is practically challenging. Certain diseases need early diagnosis and continual treatment as in the case of glaucoma for which computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems will be of much use to the clinicians in taking a second opinion before making a concrete decision and plan for treatment. In [2], a framework to get knowledge mining from patient’s clinical datasets has been presented. Numerous literatures have used various techniques in predicting the diseases like lung cancer [3–5]. A similar framework for diagnosing gait disturbances in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is detailed in [6]. Studies have shown several approaches in detecting retinal abnormalities as in [7–9]. In all the CAD systems, feature extraction and classification is the major part. Initially, a supervised learning algorithm is employed in training the classifier with a training set. Then a test set is used to evaluate the classifier. Normally used classifiers are decision trees (DT), random forest (RF), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), support vector machines (SVM), etc. Irrelevant and redundant features in the training dataset decide the classifier performance. In order to improve the performance, these irrelevant and redundant features have to be pruned and optimal feature sub-sets have to be selected. There is numerous feature selection algorithms proposed in the literatures [10–12].

Biology-inspired computational algorithms are aimed at providing improved CAD-based diagnosis and decision-making. A study of various bio-inspired algorithms such as genetic algorithm, particle swarm, firefly, bat, bacterial foraging, flower pollination, etc., is illustrated in [13]. Despite the dominance of various predicting models to predict the disease occurrence, a detailed investigation is required to enhance their efficiency or performance. Numerous machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches are extensively used. Even though they offer better performances, such methods report challenges in optimizing parameters and also have over-fitting issues. With a motive to overcome such issues, hybrid models have been used in the recent years [14]. Advantages of each individual model are integrated to overcome the defects of the individual models. With this inspiration, the proposed work presents a hybrid model to increase the prediction accuracy in medical diagnosis by combining ANFIS [15] with a modified glowworm swarm algorithm (GSO) [16]. ANFIS provides better flexibility in estimating the nonlinearity in the dataset and combines the properties of artificial neural network (ANN) and fuzzy environment, whereas the conventional GSO simulates glowworm’s behaviors during food search process. However, in order to overcome the limitations normally encountered in meta-heuristic algorithms like stagnating at a local point, the GSO is coupled with DE to improve the glowworm’s behavior. Modified GSO, called DE–SSA, is then applied to compute the parameters of ANFIS to improve prediction rate and quality. Selecting input variables is a major step toward predicting the class in any kind of diagnosis system. In this work, the input features are taken from the datasets of respective medical cases pertaining to the relevant disorders which will be dealt in the feature selection section. Summary of the main contributions of the study is given below.

Propose an improved version of glowworm swarm algorithm using a differential evolution algorithm to enhance the performance of ANFIS in predicting medical disorders.

Employ a new novel model called DE–GSO for diagnosing ophthalmic and neurodegenerative disorders.

Introduce suspect cases and provide early treatment in case of diseases that require immediate medical attention.

Rest of the paper is organized as: A brief relevant literature section for medical diagnosis using predictive models is reviewed in Sect. 2. Section 3 outlines the basics of ANFIS, DE and GSO and the proposed methodology. Experimental outcomes are discussed in Sect. 4. Section 5 gives the conclusion and scope for future work.

Related works

In this section, a brief review on the predictive methods for the identified medical disorders is presented. Leema et al. [17] designed a back propagation network (BPN)-based CAD system to classify medical datasets. Global information-added DE was employed for global search with back propagation (BP) for local search. Weight adjustment was done using the above algorithms. Particle swarm optimization (PSO) was considered to model the DE in terms of mutation process. An overall accuracy of 85.71% was reported with Pima Indian Diabetes (PID), 98.5% with Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer (WDBC) and 86.66% with Cleveland Heart Disease (CHD) datasets acquired from University of California, Irvine (UCI) machine learning repository.

In [18], Nahato et al. reported a method by integrating the advantages of fuzzy and extreme learning machine (ELM). Datasets obtained were converted to fuzzy sub-sets by making use of trapezoidal membership function. Feed forward neural network was deployed as a classifier with one hidden layer using ELM. Experiments conducted on UCI machine learning repository datasets such as Cleveland heart disease (CHD), Pima Indian Diabetes (PID) and Statlog heart disease (SHD) datasets revealed accuracies of 73.77%, 92.54% and 94.44%, respectively. Anter and Ali [19] proposed a hybrid feature selection strategy using crow search optimization (CSO) and chaos theory with fuzzy C-means (FCM) algorithm. The work reported a balance between exploration and exploitation strategies increasing the performance and attaining a good convergence speed. Experiments conducted on WDBC dataset attained 98.6% accuracy and for 68% for the Hepatitis dataset.

Wind-driven swarm optimization was proposed by Christopher et al. [20] to be used in clinical diagnosis. A novel evaluation parameter Jval was introduced to determine the rule set size and accuracy of classification. The method was reported to outperform the conventional PSO in terms of accuracy. Liver disorder and CHD dataset from UCI was used with reported accuracies of 64.6% and 77.8%, respectively.

DE-based model was reported by Storn and Price [21] to optimize nonlinear functions. Recombination was performed when initializing population done through weighted difference between randomly generated solutions summed to another third solution. The method was experimented on some standard function such as Hyper–Ellipsoid function, Ackley’s function, etc. Compared with other similar strategies, DE was reported to outperform in evaluating the number of test functions required to identify global optimum levels.

Seera and Lim [14] proposed a fuzzy min–max model combined with regression tree (CART) and random forest. It was reported that tenfold cross-validation attained better performance on UCI datasets as 78.39% for PID, 98.84% for WDBC and 95.01% for the Liver Disorder dataset.

Authors in [22] developed an Elman Neural Network using whale optimization algorithm (WOA) in optimizing NN weights. The approach was implemented in conversion velocity process of polymerization. Experiment carried out depicted that the algorithm helped in enhancing the accuracy by avoiding local trap fall. Retinal blood vessel segmentation based on PSO and its variants were discussed in [23–25]. In a nutshell, application of fuzzy expert and neural systems is expanding in predicting and screening numerous risks of abnormality in diseases as reported in [26–29].

Materials and methods

Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

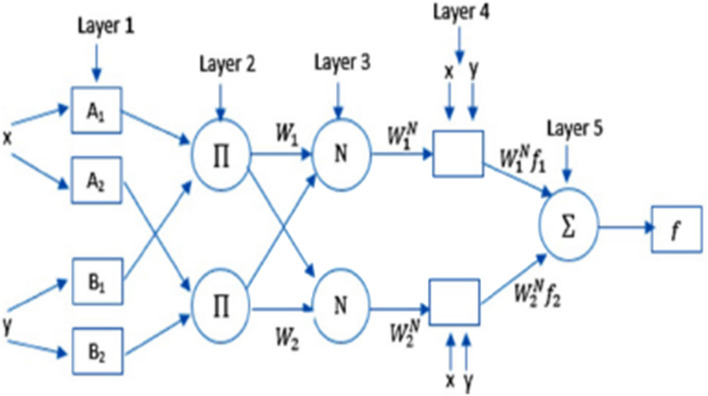

Jang in 1993 [15] presented a hybrid model, inheriting the merits of neural networks (NN) and fuzzy into a single framework called ANFIS. Takagi–Sugeno inference model is utilized which generates a nonlinear mapping from input space onto output employing fuzzy IF–THEN rules. ANFIS comprises of 5 layers as illustrated in Fig. 1

Fig. 1.

Basic structure of ANFIS [30]

Let x and y be defined crisp input to the node i, then in the first layer, the output of each node is stated as

| 1 |

| 2 |

where Ai and Bi are the values of membership function and , respectively. These values are defined by the following generalized Gaussian function [1]:

| 3 |

where pi and αi are the mean and standard deviation of data, respectively. In the literature, they are known as premise parameters set.

In the second layer, each node produces the firing strength by the following rule:

| 4 |

The output of each node, in the third layer, is the normalized firing strength obtained by the following equation:

| 5 |

The fourth layer is composed of adaptive nodes and each adaptive node creates the output, according to the function:

| 6 |

where pi, qi and ri are the consequent parameters of the ith adaptive node.

Finally, in the fifth layer there is a single node as the overall output. The value of the output is defined as:

| 7 |

The adjustable parameters such as premise and the consequent play a vital role in deciding the performance of the ANFIS. Non-steady parameters pose issues in ANFIS. Wider search space, slower convergence and getting trapped easily in local optima are some of the issues in ANFIS which can be minimized using a hybrid algorithm for optimization. To reduce this problem, hybrid techniques are widely employed. Inconsistent accuracy, more computational time, has demanded the use of hybrid algorithms to overcome these drawbacks.

Differential evolution

Differential evolution (DE) is an evolutionary algorithm, introduced in 1997 by Storn and Price [21]. The algorithm comprises of the following operations namely: mutation, crossover and selection. Wrapper method is adopted in the feature selection in selecting the feature set. Considering an optimization problem of d-dimension with d parameters, an n solution vector population is first generated. Consider xi, where i = 1, 2… n. For each solution at any generation t, chromosomes are represented by

Mutation: At any generation t, for each xi, three vectors xp, xq, xr are chosen randomly at t. By this method of mutation, the donors are represented by

F is the real and constant factor ranged [0, 2] called differential weight or mutation factor. Ideal choice will be 0 to 1 for stability. The mutation factor F is a positive control parameter preferred to scale and control the difference vector amplification. Value of F has to be carefully chosen as small values would lead to small mutation step sizes resulting in longer convergence time of the algorithm. On the other hand, large F values will facilitate exploration, instead would lead to overshooting good optima. In order to improve local exploration and maintain diversity, usually small F values are chosen.

Crossover: This process is controlled by crossover constant C which ranges between 0 and 1. The crossover constant influences on the algorithm diversity, as it takes control of the number of elements that would change. Larger values will tend to introduce more variation in the new population, therefore increasing exploration capabilities. A compromise has to be performed in ensuring both local and global search capabilities. Crossover was performed on each parameter. A uniformly distributed number generated randomly ri [0, 1]; the jth component of vi is computed as

| 10 |

One can randomly decide on exchanging each of the component with donor.

Selection: Selection follows the same step as in GA. Fittest individual is chosen with the minimum cost value as

The search performance depends on controlling the most sensitive crossover probability Cr and differential weight F. Cr = 0.5 is found to be suitable in most cases and n can be chosen between 5d – 10d. Pseudo code for DE is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Pseudo code for differential evolution

Glowworm swarm optimization (GSO)

This algorithm, proposed by Krishnanand and Ghose [16], is a simple method with fewer parameters to be adjusted and said to have a better rate of convergence. Most glowworms are able to find their position and share information by transmitting rhythm like beam. Glowworms find neighbors in their search scope by moving from one initial position to other better position. Lastly they confine to one or more extreme valued points. In GSO, the attraction of the individual glowworm is in proportion to its brightness and inverse to the distance between two individual glowworms. Fitness function depends on the position of the individuals. Pseudo code is given in Fig. 3

Fig. 3.

Pseudo code for GSO

The steps followed in GSO process are detailed below

Initialize parameters such as: n individual glowworm, lO—fluorescein value, rO—dynamic decision domain, s—step number, nt—threshold value in the domain, ρ—fluorescein elimination coefficient, γ—fluorescein update coefficient, β—update co-efficient of the domain, rs—maximum search radius, t—iteration number.

- Fitness function from J(xi(t)) is transmuted into li(t) which is given below

12 - In each , select the higher fluorescein valued individuals that form a set of neighborhood Ni(t).

13 - Probability of the individual i that move toward j as

14 - Position of the individual i could be updated by

15 -

Dynamic decision domain could be updated as

16 Initial neighborhood range of each glowworm is denoted by r0 and the parameter that controls the neighbor numbers is denoted by nt.

Iteration is continued till a maximum luciferin is obtained.

FCM clustering

Defining the membership function is the most vital concept in ANFIS. It is a clustering-based problem. Hence FCM is employed to attain smaller number of fuzzy rules. In FCM, the degree of data belonging to different clusters was obtained by minimizing the objective function:

| 17 |

where r represents a real number > 1. git denotes degree of membership of the measured data xi ∈ Rd belonging to the cluster with center ct ∈ Rd. Minimizing the above equation results in fuzzy partitioning with update of the membership (git) and the center of clusters (ct) using Eqs. (18) and (19).

| 18 |

| 19 |

This iteration will stop when maxit{|git(k+1) − git(k)|} < ∈ ,, here ∈ [0, 1] is a stopping criterion. Previous steps are repeated until the stopping condition is attained.

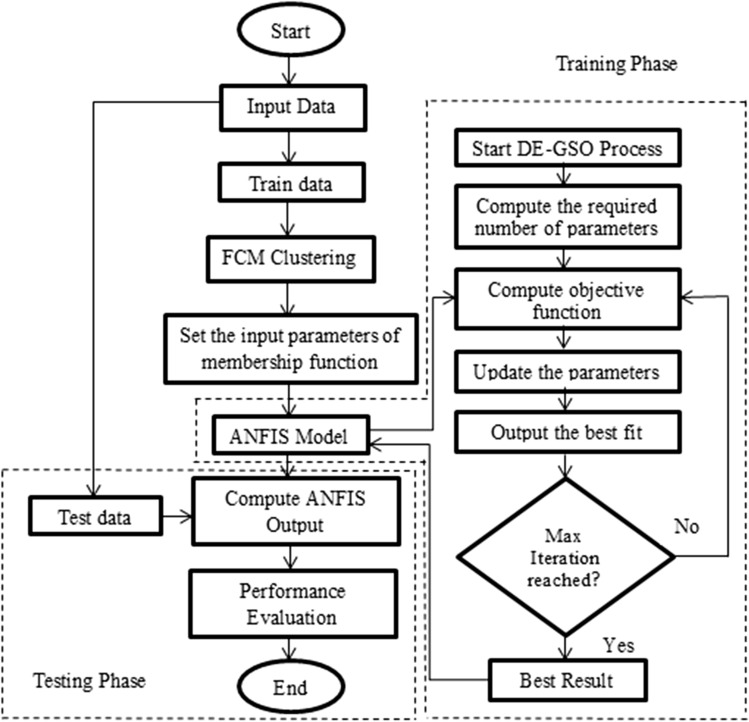

Proposed methodology

In the proposed work, a novel predictive model for medical diagnosis using a modified glowworm swarm algorithm (GSO) is used in enhancing the performance of ANFIS. In order to avoid GSO from getting trapped or stuck at local minima, DE is used to support GSO in improving the behavior of GSO. The methodology is illustrated in Fig. 4. The proposed approach enhances the ANFIS model using DE and GSO algorithms, called DE-GSO-ANFIS model. ANFIS parameters are adjusted by supplying best weights between the layers 4 and 5 of ANFIS.

Fig. 4.

Proposed Frame work

Input is obtained from datasets and divided as train and test set, normally in 70:30 ratios. Fuzzy C-mean (FCM) is applied to compute the required number of membership functions through clustering process [31]. Dataset is clustered into different sets or groups. Then, ANFIS utilizes these outcomes to initiate rest of the process. The weights of ANFIS are adapted using DE–GSO algorithm. Exploration starts now wherein the DE–GSO searches for solution in the problem search space.

DE is employed in generating the initial population of GSO. The GSO then makes use of this generated population to initiate the search for best possible weights for the ANFIS. The following equation represents the fitness value of population given by

| 20 |

where Obsi is the ith observed value and Predi is the ith predicted value.

This function depicts the summation of the square error between the original value and the predicted value. The best solution is the one which has the minimum objective function value. Hence, the weights that are chosen are updated in accordance to error reduction between the true or observed value and the predicted value during training. These weights are then carried forward to the ANFIS that prepares the problem outcomes. Training phase is stopped if the stop conditions (maximum number of iterations and error less than the small value) are satisfied. The DE–GSO continues till maximum number of iterations is reached. ANFIS is thus constructed based on the parameters arriving from the best solution. Testing phase now starts, and the best detected weights are carried to the ANFIS to generate the result.

Experiment and results

The experimental results of DE–GSO–ANFIS model, tested on predefined medical datasets, are summarized in this section and its performance is evaluated as a predictive method for medical diagnosis.

Description of the dataset

For evaluating the DE–GSO–ANFIS method, two medical diagnostic problems were experimented namely: Parkinson’s disease and Retinal abnormalities. The datasets were taken from publicly available UCI machine learning data repository and RIM-ONE dataset. Parkinson’s database comprises of biomedical voice measurement which ranges taken from 31 people out of which 23 are Parkinson’s. The database aims to discriminate normal subjects from Parkinson affected ones. The datasets are recorded with numerous medical tests on the subject. Age group of the people tested is in the range 46–85 years having 65.8 as mean age. An average of 6 vowel phonations with 36 s length each is recorded on the subject [32]. The PD dataset has 195 cases in total with 147 affected and 48 normal cases. Table 1 shows the description of Parkinson’s disease database.

Table 1.

Parkinson’s disease Dataset Description

| Features | Attribute | Description |

|---|---|---|

| F1 | MDVP: Fo (Hz) | Average vocal fundamental frequency |

| F2 | MDVP: Fhi (Hz) | Maximum vocal fundamental frequency |

| F3 | MDVP: Fo (Hz) | Minimum vocal fundamental frequency |

| F4 | MDVP: Jitter (%) | Several measures of variation in fundamental frequency |

| F5 | MDVP: Jitter (Abs) | |

| F6 | MDVP: RAP | |

| F7 | MDVP: PPQ | |

| F8 | Jitter: DDP | |

| F9 | MDVP: Shimmer | Several measures of variation in amplitude |

| F10 | MDVP: Shimmer (dB) | |

| F11 | Shimmer: APQ3 | |

| F12 | Shimmer: APQ5 | |

| F13 | MDVP: APQ | |

| F14 | Shimmer: DDA | |

| F15 | NHR |

Two measures of ratio of noise to tonal components in the voice |

| F16 | HNR | |

| F17 | RPDE | Two nonlinear dynamical complexity measures |

| F18 | D2 | |

| F19 | DFA | Signal fractal scaling exponent |

| F20 | Spread 1 | Three nonlinear measures of fundamental frequency variation |

| F21 | Spread 2 | |

| F22 | PPE |

The RIM-ONE retinal dataset contains 261 healthy images, 194 affected images accounting for a total of 455 images. The dataset can be used to study retinal abnormalities like glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy which are considered as the leading eye disorders globally. Nidek AFC-210 camera having 21.1MP resolution is utilized to acquire images [33]. Obtained images are preprocessed using morphological operations and filters to remove background noise. Adaptive histogram equalization (AHE) is done to image enhancement. Texture is vital feature of eye description. Gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) [34] is a statistical approach commonly employed in biomedical image feature extraction. Common features used are entropy, energy, homogeneity, contrast and correlation. These are called Haralick features and are defined in [35].

Description of features used from RIM-ONE.

Contrast: Measure of local changes in the image.

Homogeneity: It is a closeness measure portraying the distribution of elements in relation with the diagonal of the GLCM.

Entropy: Randomness measure of image intensity.

Energy: Uniformity measure and estimated from angular second moment (ASM). Similar pixels generate high values of ASM.

Correlation: Measure of linear dependency of gray-level values in an image.

Experimental setup

MATLAB was used to conduct the test, run on Windows 7 ultimate operating system (OS) with Intel Core i3-3217U CPU, 8 GB RAM. The algorithms were designed from scratch. For comparison with other algorithms, the parameters were standardized with population size fixed as 25 and maximum iteration fixed to 100. Number of features is taken as the problem dimension. For ease of computation, data scaling was done as [− 1, 1]. K-fold cross-validation was performed to get unbiased results [36].

Performance evaluation

For a classifier, each instance is directly mapped on to positive [P] and negative [N] class labels. A confusion matrix consists of information on the actual or true classes and the predicted classes performed by classifier. Table 2 shows such an instance on confusion matrix normally followed in classification.

Table 2.

Confusion matrix

| Actual/true class | ||

|---|---|---|

| P | N | |

| Predicted class | ||

| P | True positive (TP) | False positive (FP) |

| N | False negative (FN) | True negative (TN) |

True positive (TP): Number of correct predictions that an instance is positive

False positive (FP): Number of incorrect predictions that an instance is positive

True negative (TN): Number of correct predictions that an instance is negative

False negative (FN): Number of incorrect predictions that an instance is negative

The different evaluation criteria used are mentioned in Table 3

Table 3.

Performance indices

| Parameter | Expression |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Sen) | |

| Specificity (Spec) | |

| Accuracy (Acc) |

Apart from the above metrics, following are also utilized in computing the efficiency of the DE–GSO–ANFIS method as defined below:

- Mean square error (MSE) Measure of data dispersion around zero value calculated by

denotes ith predicted element, yi shows ith measured element, sample number is denoted by n yi shows the average of the corresponding predicted value.21 - Mean absolute error (MAE): Measure of the mean absolute deviation of output values from that of target values given by

22 - RootMSE (RMSE): Measure of the square of MSE computed by

23 - Coefficient of determination (R2): Measure of relationship between the obtained data value and the predicted data value defined by

24 - Standard deviation (SD):

25

Results and discussion

Assessment of the proposed DE-GSO-ANFIS method for medical diagnosis is performed. The input dataset is categorized into 70% training and the rest onto testing. Besides, the proposed method is also compared with other similar methods, such as traditional ANFIS model, genetic algorithm–ANFIS (GA–ANFIS), particle swarm optimization–ANFIS (PSO-ANFIS), lion optimization algorithm—ANFIS (LOA-ANFIS), differential evolution–ANFIS (DE–ANFIS) and gray wolf optimization–ANFIS (GWO–ANFIS). These were chosen based on their performance as predictive models in various applications. In swarm algorithms, the population size and iterations are considered as key factors. In order to optimize the process, iteration was fixed and population size was iterated to show the hybrid nature of the algorithm proposed. Parameter settings were done owing to proven records in the literatures as given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter settings for comparison

| Algorithm | Parameter setting |

|---|---|

| K for Cross-validation | 10 |

| ANFIS |

Maximum epochs = 100, Initial Step = 0.01 Error goal = 0, Increase rate = 1, Decrease rate = 0.9, |

| GA-ANFIS | Crossover = 0.8, mutation = 0.01 |

| DE-ANFIS | F = 0.8, C = 0.5 |

| LOA-ANFIS | Nomads = 40, Prides = 20 |

| PSO-ANFIS | wMax = 0.9, wMin = 0.2, C1 = 2, C2 = 2 |

| GSO-ANFIS | ρ = 0.4, γ = 0.6, β = 0.08, nt = 5, s = 0.03, lO = 5 |

FCM is executed to compute the optimal number of membership functions (no. of clusters). FCM is applied at different cluster number values, and the results are shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that the optimal numbers of memberships are 3 and 6 with RMSE 0.33 and 0.32, respectively. Therefore, the number of memberships is set to 6.

Fig. 5.

Results to compute optimal number of clusters of FCM

Table 5 depicts the details of prediction results in terms of prediction accuracy, sensitivity and specificity on the Parkinson’s dataset using DE–GSO–ANFIS as a classifier model with 100 iterations.

Table 5.

Performance of DE–GSO–ANFIS on Parkinson’s disease dataset

| Population Size | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 93.37 | 96.14 | 92.68 |

| 10 | 97.99 | 98.4 | 94.97 |

| 16 | 94.24 | 95.22 | 87.65 |

| 20 | 95.11 | 94.88 | 93.07 |

From the table, for the Parkinson’s dataset, it can be inferred that a population size of 10 attained the best accuracy with 98.4% sensitivity and 94.97% specificity for the DE–GSO–ANFIS model. While the population size is increased, the accuracy has some rise and falls. Similarly, for the RIM-ONE dataset, 98.66% accuracy was achieved with DE–GSO–ANFIS model for a population size of 10. As the population size is increased, the accuracy varies. Figure 6 shows the overall performance of DE–GSO–ANFIS in predicting the disease on Parkinson’s dataset for varying population size.

Fig. 6.

Performance of DE–GSO–ANFIS in predicting the disease on Parkinson’s dataset

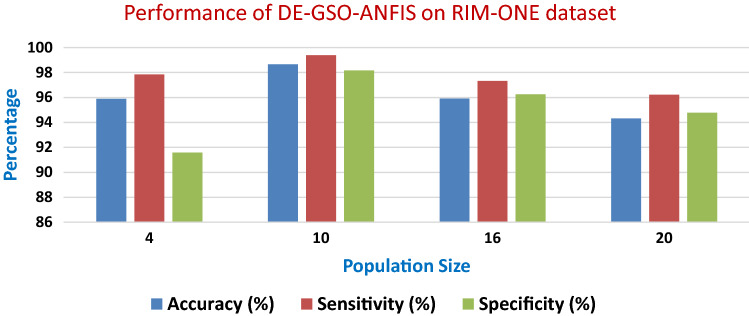

Table 6 depicts the details of prediction results in terms of accuracy, sensitivity and specificity on the RIM-ONE dataset using DE–GSO–ANFIS as a classifier model with 100 iterations.

Table 6.

Performance of DE-GSO-ANFIS on RIM-ONE dataset

| Population Size | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 95.89 | 97.84 | 91.58 |

| 10 | 98.66 | 99.38 | 98.16 |

| 16 | 95.92 | 97.33 | 96.26 |

| 20 | 94.32 | 96.22 | 94.77 |

Figure 7 shows the overall performance of DE–GSO–ANFIS in predicting the disease on RIM-ONE for varying population size.

Fig. 7.

Performance of DE–GSO–ANFIS in predicting the disease on RIM-ONE dataset

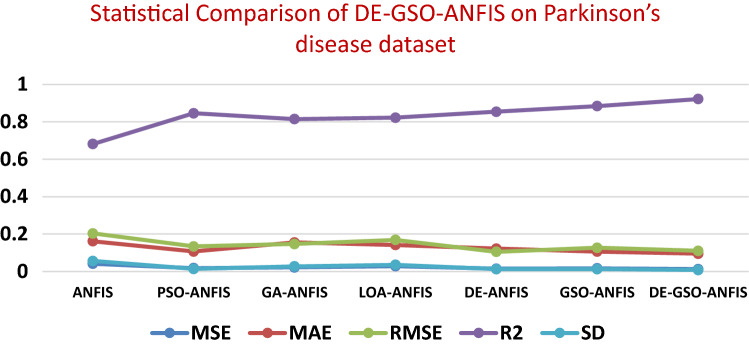

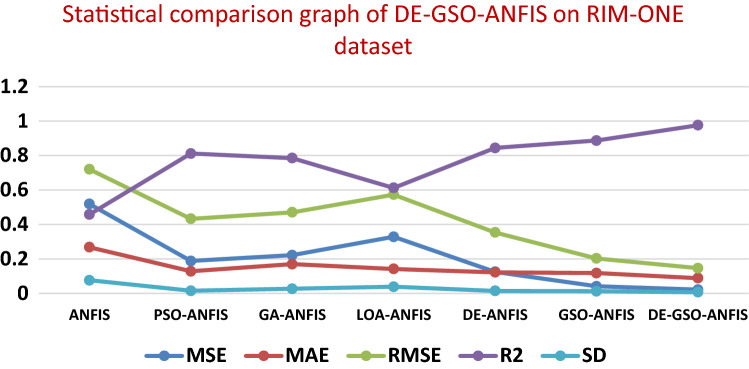

A comparison of the proposed with well-known models by means of statistical analysis is illustrated in Tables 7 and 8. Figures 8 and 9 show the statistical comparison of DE–GSO–ANFIS on Parkinson’s disease dataset and RIM-ONE dataset. It clearly shows the performance of the proposed model on different datasets with statistical parameters like MSE, MAE, RSME, R2 and SD.

Table 7.

Statistical comparison of DE–GSO–ANFIS on Parkinson’s disease dataset

| Model | MSE | MAE | RMSE | R2 | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANFIS | 0.0415 | 0.1614 | 0.2037 | 0.6814 | 0.0563 |

| PSO–ANFIS | 0.0180 | 0.1065 | 0.1341 | 0.8462 | 0.0138 |

| GA–ANFIS | 0.0216 | 0.1551 | 0.1469 | 0.8145 | 0.0273 |

| LOA–ANFIS | 0.0284 | 0.1418 | 0.1685 | 0.8226 | 0.0356 |

| DE–ANFIS | 0.0150 | 0.1218 | 0.1052 | 0.8541 | 0.0125 |

| GSO–ANFIS | 0.0163 | 0.1062 | 0.1267 | 0.8842 | 0.0124 |

| DE–GSO–ANFIS | 0.0122 | 0.0948 | 0.1104 | 0.9218 | 0.0078 |

Table 8.

Statistical comparison of DE–GSO–ANFIS on RIM-ONE dataset

| Model | MSE | MAE | RMSE | R2 | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANFIS | 0.5184 | 0.268 | 0.72 | 0.458 | 0.0762 |

| PSO–ANFIS | 0.1878 | 0.1278 | 0.433 | 0.812 | 0.0148 |

| GA–ANFIS | 0.2216 | 0.1697 | 0.4708 | 0.785 | 0.0266 |

| LOA–ANFIS | 0.3284 | 0.142 | 0.5731 | 0.612 | 0.0386 |

| DE–ANFIS | 0.1250 | 0.122 | 0.3535 | 0.844 | 0.0145 |

| GSO–ANFIS | 0.0412 | 0.118 | 0.203 | 0.887 | 0.0122 |

| DE–GSO–ANFIS | 0.0215 | 0.0886 | 0.1466 | 0.976 | 0.0068 |

Fig. 8.

Statistical comparison graph of DE-GSO-ANFIS on Parkinson’s dataset

Fig. 9.

Statistical comparison graph of DE-GSO-ANFIS on RIM-ONE dataset

The lowest values of MSE, RMSE, MAE indicate the best method, and the higher R2 value depicts better correlation for the method. It can be seen from the table that DE–GSO–ANFIS provides the lowest MSE, RMSE and MAE values next to GSO–ANFIS. R2 value is also seen to be high. Lowest standard deviation is also achieved comparatively by this method. The traditional ANFIS provided high MSE and RMSE values. Appreciable values are obtained by DE and GSO individually but next only to the proposed method. It can also be seen that the GSO–ANFIS and DE–ANFIS also performed well in terms of R2 and standard deviation compared to other algorithms other than the DE–GSO–ANFIS model on both the datasets. The combination of DE and GSO has proved its effectiveness by attaining a balanced performance as the benefits of both the individual algorithms are utilized in this work.

Conclusions and future work

Improvement of ANFIS model using DE–GSO algorithm is proposed in enhancing its prediction capabilities with respect to medical diagnosis such as Parkinson’s disease and retinal abnormalities, considering it as an optimization challenge. Experimental outcomes have proved that the proposed DE–GSO–ANFIS model for the UCI dataset and RIM-ONE dataset has outperformed other similar algorithms in terms of performance indices and statistical analysis. It is inferred that the DE–GSO–ANFIS has recorded lowest MSE, RMSE and MAE values and has highest R2 measure. The performance of ANFIS relies on the parameters, and those parameters have to be estimated by a suitable method. Hence, differential evolution and glowworm swarm algorithms are combined and applied to ANFIS to determine its parameters. This novel combination, called DE–GSO, focused on enhancing the ability of GSO in finding a global solution (ANFIS parameters). The proposed DE–GSO–ANFIS model can be used as a second opinion expert to grade suspect classes in medical diagnosis. This model can prove as an expert system where skilled professionals are in demand. The method has to be tested on real-time retinal datasets to prove the efficiency of model. As seen from the results, the proposed DE–GSO–ANFIS model can be applied to predict other diseases like COVID-19, coronary heart disease, hepatitis, etc., and also applied to forecast commodities in industrial sector like refineries, foreign exchange, mining, agriculture projects.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest and no funding is obtained related to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bellazzi R, Zupan B. Predictive data mining in clinical medicine: current issues and guidelines. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(2):81–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nahato KB, Harichandran KN, Arputharaj K (2015) Knowledge mining from clinical datasets using rough sets and back propagation neural network. Comput Math Methods Med 2015, Article ID 460189. 10.1155/2015/460189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Elizabeth DS, Raj CSR, Nehemiah HK, Kannan A. Computer-aided diagnosis of lung cancer based on analysis of the significant slice of chest computed tomography image. IET Image Process. 2012;6(6):697–705. doi: 10.1049/iet-ipr.2010.0521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweetlin JD, Nehemiah HK, Kannan A. Computer aided diagnosis of pulmonary hamartoma from CT scan images using ant colony optimization based feature selection. Alexandria Engineering Journal. 2018;57(3):1557–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2017.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Titus A, Nehemiah HK, Kannan A. Classification of interstitial lung diseases using particle swarm optimized support vector machine. Int J Soft Comput. 2015;10(1):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jane YN, Nehemiah HK, Arputharaj K. A Q-backpropagated time delay neural network for diagnosing severity of gait disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. J Biomed Inform. 2016;60:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acharya U, Rajendra U, Ng EYK, Wei L, Eugene J, et al. Decision support system for the glaucoma using Gabor transformation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2015;15:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2014.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acharya U, et al. Decision support system for the glaucoma using Gabor transformation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2015;15:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2014.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhaskaranand M, et al. Automated diabetic retinopathy screening and monitoring using retinal fundus image analysis. J Diabet Sci Technol. 2016;10(2):254–261. doi: 10.1177/1932296816628546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dy JG, Brodley CE. Feature selection for unsupervised learning. J Mach Learn Res. 2004;5:845–889. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Z, Liu H (2007) Semi-supervised feature selection via spectral analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2007 SIAM international conference on data mining, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Minneapolis, MN, USA, pp 641–646

- 12.Song L, Smola A, Gretton A, Borgwardt KM, Bedo J (2017) Supervised feature selection via dependence estimation. In: Proceedings of the 24th international conference on Machine learning, ACM, Corvallis, OR, USA, pp 823–830

- 13.Kar AK. Bio inspired computing—a review of algorithms and scope of applications. Expert Syst Appl. 2016;59:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2016.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seera M, Lim CP. A hybrid intelligent system for medical data classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2014;41(5):2239–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2013.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang JSR. Anfis: Adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1993;23(3):665–685. doi: 10.1109/21.256541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnanand KN, Ghose D. Glowworm swarm optimization: a new method for optimizing multi-modal functions. Int J Comput Intell Stud. 2009;1(1):93–119. doi: 10.1504/IJCISTUDIES.2009.025340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leema N, Nehemiah HK, Kannan A. Neural network classifier optimization using differential evolution with global information and back propagation algorithm for clinical datasets. Applied Soft Computing. 2016;49:834–844. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2016.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nahato KB, Nehemiah KH, Kannan A. Hybrid approach using fuzzy sets and extreme learning machine for classifying clinical datasets. Inform Med Unlocked. 2016;2:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anter AM, Ali M (2019) Feature selection strategy based on hybrid crow search optimization algorithm integrated with chaos theory and fuzzy c-means algorithm for medical diagnosis problems. Soft Comput 1–20

- 20.Christopher JJ, Nehemiah HK, Kannan A. A swarm optimization approach for clinical knowledge mining. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;121(3):137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storn R, Price K. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J Global Optim. 1997;11(4):341–359. doi: 10.1023/A:1008202821328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun WZ, Wang JS (2017) Elman neural network soft-sensor model of conversion velocity in polymerization process optimized by Chaos Whale optimization algorithm. IEEE, pp 13062–13076

- 23.Hassan G, Hassanien AE. Retinal fundus vasculature multilevel segmentation using whale optimization algorithm. Signal Image Video Process. 2018;12(2):63–270. doi: 10.1007/s11760-017-1154-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sreejini KS, Govindan VK. Improved multi-scale matched filter for retina vessel segmentation using PSO algorithm. Egyptian Inf J. 2015;16(3):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.eij.2015.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palraj P, Vennila I. Retinal fundus image registration via blood vessel extraction using binary particle swarm optimization. J Med Imaging Health Inf. 2016;6(2):328–337. doi: 10.1166/jmihi.2016.1701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrbakhsh N, Hossein A, Leila S, et al. A predictive method for hepatitis disease diagnosis using ensembles of neuro-fuzzy technique. J Infection Public Health. 2019;12(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alejandro M, Elena N, Javier J, Pascual G (2019) Fuzzy-description logic for supporting the rehabilitation of the elderly. Exp Syst e12464

- 28.Amita D, Priti D, Soumya SP, Sukanta S. Adaptive fuzzy clustering-based texture analysis for classifying liver cancer in abdominal CT images. Int J Comput Biol Drug Des. 2018;11(3):192–208. doi: 10.1504/IJCBDD.2018.094629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulzar A, Muhammad AK et al (2019) Automated diagnosis of hepatitis b using multilayer mamdani fuzzy inference system. J Healthcare Eng [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.El Aziz MA, Hemdan AM, Ewees AA et al (2017) Prediction of biochar yield using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system with particle swarm optimization. In Power Africa, 2017 IEEE PES, pp 115–120

- 31.Bezdek JC, Ehrlich R, Full W. FCM: the fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm. Comput Geosci. 1984;10:191–203. doi: 10.1016/0098-3004(84)90020-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little MA, McSharry PE, Hunter EJ, et al. Suitability of dysphonia measurements for telemonitoring of Parkinson’s disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2009;56(4):1015–1022. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.2005954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fumero F, et al. RIM-ONE: An open retinal image database for optic nerve evaluation. Int Symp Comput Based Med Syst. 2011;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1973;3(6):610–621. doi: 10.1109/TSMC.1973.4309314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo TS et al (2002) Engineering and algorithm design for an image processing API: a technical report on ITK—the insight toolkit. In: Proceedings of medicine meets virtual reality, J. Westwood, ed., IOS Press Amsterdam, pp 586–592 [PubMed]

- 36.Kohavi R (1995) A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In: Proceedings of the 14th international joint conference on artificial intelligence (IJCAI’95), Canada, vol 2, pp 1137–1143