Abstract

In the spring of 2020, our hospital faced a surge of critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients, with intensive care unit (ICU) occupancy peaking at 204% of the baseline maximum capacity. In anticipation of this surge, we developed a remote communication liaison program to help the ICU and palliative care teams support families of critically ill patients. In just nine days from inception until implementation, we recruited and prepared ambulatory specialty providers to serve in this role effectively, despite minimal prior critical care experience. We report here the primary elements needed to reproduce and scale this program in other hospitals facing similar ICU surges, including a checklist for replication (Appendix I). Keys to success include strong logistical support, clinical reference material designed for rapid evolution, and a liaison team structure with peer coaching.

Key Words: COVID-19, communication liaison, ICU surge, redeployment

Key Message

This article describes the rapid implementation of a remote communication liaison program to support intensive care units facing a surge of coronavirus disease 2019-related patients. The program model is reproducible in a variety of settings, and key implementation materials are included.

Background

On April 13, 2020, Victor Zapana, Jr., invited an audience to observe his father's death from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The audience bore witness much as Zapana, Jr., had: not live, nor with video or audio, but through two brief excruciating pages of transcribed text messages, published in a New Yorker Magazine article.1 His father, Victor Zapana, Sr., lay in a New York hospital bed at the height of the city's COVID-19 crisis, too short of breath to speak by phone. The reader learns of Mr. Zapana Sr.'s hospital course as his son did, bit by bit, through a dwindling series of fractured and ambiguous text messages from his father, tapering to days of unexplained silence. Excluded from his father's bedside, and unable to reach any of the besieged caregivers for an update, Mr. Zapana, Jr., and his readers, receive the crushing news of his father's death having never been informed of the elder Zapana's intubation three days prior.

A defining tragedy of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the separation of families from their critically ill loved ones, especially at the last moments of life. Necessarily prohibitive hospital visitation policies exclude families from the bedside; at the same time, the need to deploy significant numbers of additional physicians and nurses to the intensive care unit (ICU), some with little to no critical care experience, leaves few with the time or expertise to hold difficult conversations and compassionately support families. Strategies to optimize palliative care team responses to COVID-19 patient influxes have been reported,2, 3, 4 but during severe surges, the need for frequent and expert family communication can, and did, overwhelm even the largest palliative care teams' capacities.

At our institution, we faced this challenge by rapidly developing a remote communication liaison program (RCLP) to help the ICU and palliative care teams support families of critically ill patients. We report here the primary elements needed to reproduce and scale this program in other hospitals facing similar ICU surges.

Defining the Need

In the spring of 2020, Massachusetts saw thousands of COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals throughout the state. Facing an impending surge, our 335-bed tertiary care teaching hospital prepared to expand ICU capacity from 52 beds at baseline to at least 160 ventilator-ready beds. The surge plan relied heavily on redeployment of physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and medical assistants to care for patients in units repurposed as COVID-19 wards and ICUs. ICU occupancy quickly surpassed historic capacity, peaking at 204% of the baseline ICU maximum, with 106 critical care patients on April 30, 2020.

By late March, well before the ICU census peaked, the volume of COVID-19 inpatients requiring daily family communication and support began to overwhelm frontline palliative care and ICU teams, causing great distress for providers and bedside nurses, who were often the only individuals present to comfort dying patients. Concurrently, many subspecialty providers who had not been deployed to the ICUs were eager to help and had excess capacity because all elective surgeries and many ambulatory visits were suspended. Some of these providers had not been deployed because their age or health status imparted unacceptably high risk to on-site service. More commonly, however, these providers had not been selected for ICU service because they lacked the critical care experience to justify their presence, especially when critically low personal protective equipment supplies required thoughtful distribution to only those caregivers able to provide care most effectively. The challenge quickly became clear: how to remotely provide family support and palliative care with a cadre of providers who were willing to provide this service but who lacked the critical care skill set or formal training in palliative care.

Program Design

In response, we developed the RCLP to support communication between ICU teams, the palliative care team, and families of ICU patients during the COVID-19 ICU surge (Appendix I). The RCLP was designed for a dual mission to support the families of critically ill COVID-19 patients and the ICU teams delivering care to those patients. To achieve these goals, communication liaisons needed to speak with families at least once a day and to provide timely and accurate clinical updates, empathic guidance through difficult decisions, and consistent emotional support.

The next challenge was to provide rapid training for liaisons in the basics of critical care medicine and palliative care communication. A large plurality of liaisons were dermatologists, pathologists, and ophthalmologists; very few had recent or substantial experience with either critical care medicine or end-of-life care. Errors in communication stemming from liaison misunderstanding or misrepresentation could cause substantial emotional harm to patients and families. Liaisons needed to reliably extract and relay pertinent clinical information, without seeing the patient directly, without the presence of rounds, without extensive contact with the ICU teams, and without substantial prior expertise in the subject matter at either end of the communication.

The pilot phase of the program quickly demonstrated that effective communication under these circumstances was indeed possible, if liaisons were provided three basic ingredients for success:

-

1.

Logistical support

-

2.

Clinical reference materials provided through a wiki

-

3.

Liaison team coaching

Logistical Support

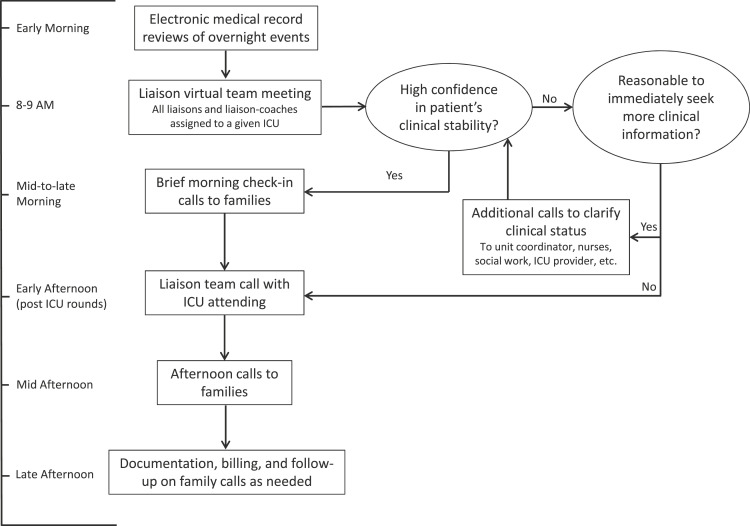

Liaisons participated in interactive virtual orientation sessions and received a comprehensive reference guide detailing all structural components of the program, including a recommended daily schedule (Fig. 1 ), documentation instructions, coding and billing guidelines, and links to other pertinent reference material (Appendix II). A new liaison communication note type was created in the electronic health record to clearly distinguish liaison notes from consult notes related to the liaison's primary specialty. A new liaison note template streamlined and standardized documentation and provided liaisons with memory triggers to help them navigate through difficult discussions (Appendix III). To maintain liaison privacy, outgoing calls to families were routed through the hospital; families could reach out to their liaison through virtual pagers established for the program.

Fig. 1.

Daily liaison schedule. ICU = intensive care unit.

Clinical Reference Wikis

The program created two collaborative guides, a palliative care wiki and a critical care wiki, populated initially with abbreviated key content from subject matter experts (Appendix IV). All program participants were encouraged to amend the documents as they learned from experience during their liaison service blocs. The palliative care wiki included sections on medicolegal documents and considerations, goals-of-care basics, and a guide to challenging conversations. The critical care wiki included instruction on performing an ICU chart biopsy and quick guides to hemodynamic assessments, common infusions, and ventilator settings. With constant updates, both wikis quickly evolved into refined, effective, and stand-alone references.

Liaison Team Coaching

Early in the pilot phase, it became clear that even novice liaisons consulting with each other could work through many of their questions without the need for extensive consultation with critical care teams or other experts. Therefore, each ICU was assigned a team of two to three liaisons who would discuss their respective patients each morning, leveraging their complementary expertise as they grappled with challenging situations.

Each team had one team member with more extensive experience with critical care medicine, end-of-life care issues, or challenging conversations who served as a coach, in addition to performing the typical functions of a communication liaison. The liaison coaches were typically experienced providers in fields, such as medical oncology, surgical oncology, neurology, and primary care. Many held clinical and academic leadership positions, through which they had experience guiding less experienced providers through various challenges. Finally, the liaisons and coaches could escalate deeper concerns to the program's lead coach, or to the palliative care providers, who participated in many of the liaison daily team meetings, and who could assume the primary communication role when a higher level of expertise was required.

Outcomes

The RCLP was established swiftly to match the speed of the surge, with liaison coverage to all COVID-19 ICUs commencing on April 11, just nine days after the program's inception. Liaisons set aside other professional obligations for four-day shifts, staggered with the ICU team blocs to provide continuity through team transitions.

Liaisons worked remotely, gathering information from chart reviews and discussions with critical care team members (Fig. 1). Early each morning, liaisons reviewed their patients' electronic records to learn about overnight events and any changes in clinical status. After these chart reviews, all liaisons and liaison coaches assigned to a given unit would meet together virtually to confirm or clarify their understanding of their chart reviews and to discuss anticipated challenges in the planned phone calls for that day. Palliative care providers, who also divided themselves according to specific ICUs during the surge, joined these morning liaison team calls for their units whenever possible.

For patients whose chart review suggested overnight stability, liaisons would make the first of two planned daily calls to their family member, after the morning of liaison team meeting. In these calls, liaisons would inform a patient's family of the patient's stable status, remind them that the liaison would be in touch later in the day after speaking with the ICU team, and inquire whether the family member had any specific questions or concerns to relay to the ICU team. A primary purpose of these brief check-in calls was to reaffirm to family members that their loved ones had the attention of hospital caregivers; by calling and assuaging anxiety early in the day, liaisons pre-empted family members' calls into the ICU early in the day during rounds when it was difficult for the ICU team members to meet their needs. When the chart review suggested a clinical status change, or raised questions the liaison could not answer from the chart alone, the morning check-in call was deferred until the liaison could speak to an on-site ICU team member for clarification.

In the early afternoon, after the ICU team finished their on-site rounds, the liaison team would meet virtually with the ICU attending. In these calls, the ICU attending would answer liaisons' questions and ensure mutual understanding of the care plan. They would discuss any major changes in prognosis, goals, or clinical course that would inform the communication between the liaison and the family members later that afternoon. In the case of a substantial clinical status change, the ICU attending might ask the liaison to defer the afternoon family phone call to the on-site ICU providers or palliative care team. The program's training in the basics of critical care medicine allowed liaisons to converse with ICU teams efficiently and then to reliably address many of the clinical questions posed by family members.

Liaisons would then call the patients' family members a second time to provide more detailed updates, answer questions, provide emotional support, and retrieve information that would help the ICU team care for the patient. Liaisons were trained to remain attentive to comments from family members that might further inform goals-of-care considerations and how to pivot on those comments to help family members discuss difficult and emotional issues to make the best possible decisions for their critically ill relatives.

During the course of the program, liaisons provided extensive clinical updates to patients' families. However, providing emotional support remained the top priority for these family phone conversations, over other important tasks such as providing test results and clarifying goals of care. Liaison schedules were structured to allow them the time to build trust with families, so that when critical time-sensitive information needed to be conveyed in either direction, liaisons would be well positioned to facilitate that communication. We repeatedly reminded liaisons of program's core mission to support families and ICU team colleagues, with emphasis on the word support, recognizing that liaisons could achieve much of the program's intended benefit by listening actively and responding with empathy. By explicitly elevating the provision of emotional support above other important liaison functions, we sought to protect liaisons from pressure to interpret or communicate data beyond their fund of knowledge, thereby minimizing the risk of harm from delivery of erroneous clinical details. Because of the program's core supportive mission, liaisons could leverage their pre-existing empathy and interpersonal skills to mitigate the key problem at the heart of the liaison program's inception: the exclusion of family from the bedsides of their critically ill loved ones.

The rapidly evolving COVID-19 surge challenged hospital and ICU leaders to adapt operations swiftly, in broad, sometimes unforeseen ways that often caused sudden fluctuations in the immediate need for liaisons. Increasingly, close communication between the RCLP leadership and the ICU surge leaders during the course of the program moderated these impacts, and the liaisons responded to disruptions with magnanimity, volunteering on very short notice, shifting liaison teams without complaint, or graciously agreeing to delay service blocs despite having cleared their schedules for their expected four-day shifts.

The program ran for 53 days until June 2, 2020, when the surge waned sufficiently to disband. In that time, 65 providers from 19 specialties served in at least one four-day liaison bloc. They included 44 physicians, 19 advanced practitioners, and two psychologists. Twenty-four of them served as liaison coaches at some point during the program. Fifty-four of the 65 liaisons chose to return for at least one additional service bloc, and 14 liaisons volunteered at least four times. In all, the liaisons supported families of more than 140 COVID-19-positive ICU patients and wrote more than 1450 notes documenting their conversations and any implications relevant to patient care.

Conclusions

We present here a model for rapidly deploying a broad range of providers to support families of the critically ill and provide relief to ICU teams working through severe and taxing conditions. This model is feasible in a variety of settings (Appendix I), easily scalable, and can be successful in supporting overstretched palliative care and critical care teams. Adapting our training paradigm, clinicians with even minimal prior exposure to critical care or palliative medicine can quickly learn to perform such a liaison service skillfully and to great benefit. Liaisons exhibited a high degree of engagement with the program, evidenced by the high (>80%) proportion of repeat volunteers and their magnanimous responses to scheduling disruptions, as well as by informal strongly positive feedback from many of the liaisons. Keys to success include strong logistical support, a team-based system with peer coaching, and just-in-time training with quick guides in wiki format to allow constant updates. As the nation faces new COVID-19-related ICU surges, expanded communication support remains a critical need in this pandemic.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix I.

Checklist for Establishing a Remote Communication Liaison Service Amidst an ICU Surge

| Key Step | How LHMC Achieved This Step |

|---|---|

| Lay the groundwork | |

| Form a planning committee | Included chair of palliative care, two critical care providers, chair of medicine, chief academic officer (surgical palliative care expert), chair of dermatology (operational lead), and director of the cancer center (lead coach) |

| Explicitly define the mission | To support families of critically ill COVID-19 patients and the ICU teams caring for them. (Note that the program may look quite different if the primary mission is for liaisons to communicate with families in a way that mirrors typical ICU team communication as closely as possible) |

| Ensure buy-in from ICU | Discussed with critical care chair, surge planning lead, and incident command. Created a brief guide to the program for ICU-attending physicians |

| Develop key telecommunication and electronic medical record tools | |

| Paging system | New communication liaison service virtual pagers. Each ICU's pager automatically signed out daily to that unit's primary liaison, as identified on the master schedule |

| Virtual phone system | Calls from liaisons' personal devices displayed on recipients' devices as a hospital phone number |

| Conference call support | Google Meet for daily conference calls between liaison teams and ICUs |

| Electronic medical record tools | New communication liaison note type and care team relationship. New note template (Appendix III) |

| Recruit liaisons | |

| Identify candidate liaisons | Asked division chairs and hospital leaders for recommendations. Asked liaisons to recommend peers |

| Request participation and gather information on availability | Used a survey (Google Form) to determine candidate willingness to serve as liaisons and/or coaches and to provide their expected availability during a four- to five-week period. Repeated monthly |

| Confirm commitment | Ensured volunteers and their chairs/directors understood that their liaison work would be full time during their four-day service blocs |

| Scheduling tools | Created a spreadsheet to track volunteer availability and rotation assignments and a master schedule to identify specific unit assignments within each bloc |

| Educate and prepare liaisons | |

| Pilot program(s) | Four-day pilot with the most experienced or prepared liaisons, to seed the coaching system, refine the operations, and develop the training materials |

| Develop a written guide | Included all key operational information for liaisons (Appendix II) |

| Critical care clinical reference | Critical care wiki (Appendix IV) initiated by planning committee and pilot liaisons |

| Palliative care clinical reference | Palliative care wiki (Appendix IV) initiated by planning committee and pilot liaisons |

| Orientation sessions | Several one-hour virtual orientations, recorded for future reference |

| Coaching tip sheet | Coaches serve as both expert liaisons and team leads, organizing all communication within each liaison team and between the liaison team and the ICU-attending physicians |

| Provide ongoing liaison support | |

| Assign liaison teams | A team consisted of one liaison coach and at least one additional liaison. Aimed for a ratio of one liaison (or coach) per five to six ICU beds. Tried to ensure complementary experience within teams (e.g., a psychologist with advanced communication skills paired with a gastroenterologist familiar with ICU care) |

| Remind coaches of key tasks | Coaches were to arrange a preservice team conference call, daily morning team calls, daily afternoon calls between the liaison team and the ICU attending, and a postservice handoff to the incoming coach or whole team |

| Reinforce options for escalation | Liaisons and coaches could always request assistance from peer liaisons and the program's lead coach. Palliative care providers often joined daily conference calls to guide liaisons, and they would assume responsibility for cases that surpassed a liaison's abilities or comfort levels |

| Solicit feedback | Electronically mailed liaisons after each bloc and asked for feedback with each round of bloc sign-ups. Requested their ongoing flexibility to meet unexpected challenges that invariably arose |

ICU = intensive care unit; LHMC = Lahey Hospital & Medical Center; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Appendix II.

Key Sections of the Communication Liaison Program Guide

| Section | Selected Key Details |

|---|---|

| Introduction | |

| Mission | To support families of COVID-19-positive critical care patients and the providers caring for them |

|

Liaisons must be able to serve families and critical care teams

|

|

|

|

|

| Technical elements | |

|

|

| Prerotation instructions | |

|

|

|

|

| Daily schedule/instructions: see Fig. 1 |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ICU = intensive care unit.

Appendix III.

Communication Liaison Note Template and Smart Tool Index:

| Communication Liaison Note Template Critical Care Communication Liaison Note Patient: @NAME@ Date of Service: @TD@ DOB: @DOB@ MRN#: @MRN@ CSN: @CSN@ Critical Care Liaison Provider @MECRED@ HPI: @NAME@ is a @AGE@ @SEX@ admitted on @ADMITDT@ for ∗∗∗. Current status: ∗∗∗ vital signs: Critical Care Liaison Provider televisit performed primarily for {Palliative Care Reason for Consult:30421401} Meeting conducted by telephone. The following people (names and relationships to the patient) participated in the meeting:

Markers of progress or setbacks and expected milestones (and what we might do if they are not achieved) {WERE/WERE NOT: 19,253} discussed: ∗∗∗ The patient's functional status, health characteristics, and/or social history prior to admission {WERE/WERE NOT: 19,253} discussed: ∗∗∗ What are the patient's goals as they relate to the current clinical status? {Goals: 304000950} Are the patient's goals realistic in the context of the current clinical status and the patient's status prior to admission? ∗∗∗ Healthcare Proxy/Advance Directive/Consent: Has the healthcare proxy been activated? {HCP Activated: 304009027} Are there existing advanced directives? {Responses: 304009028} Confirm code status: {Code Status: 304000943} Who was code status confirmed with? {Confirmed With: 304000944} SUMMARY, ASSESSMENT, PLAN, NEXT STEPS: ∗∗∗ @telehealthdocumentation@ @TD@ @NOW@ @mecred@

|

| Smart Tool Index | |

|---|---|

| Smart Link | Output |

| @NAME@ | Patient's full name |

| @TD@ | Today's date |

| @DOB@ | Patient's date of birth |

| @MRN@ | Patient's medical record number |

| @CSN@ | Encounter's contact serial number |

| @MECRED@ | Author's name and credentials |

| @AGE@ | Patient's age |

| @SEX@ | Patient's sex |

| @ADMITDT@ | Date of admission |

| @VS@ | Vital signs |

| @telehealthdocumentation@ | Institution-specific phrase with smart lists to drive telemedicine billing |

| @NOW@ | Current time |

| Smart List | Options Presented |

|---|---|

| Palliative care reason for consult: 30421401 | Assistance with advance directives Assistance with clarification of goals of care Assistance with withdrawal of life-prolonging measures Facilitation of family care conference Hospice referral or discussion Nonpain symptoms Pain Psychosocial support Spiritual support ∗∗∗ |

| WERE/WERE NOT: 19,253 | Were or were not |

| Goals: 304000950 | Recovery to baseline before this admission Recovery to rehabilitation/long-term assisted care (different than baseline before admission) Comfort Unsure ∗∗∗ |

| HCP activated: 304009027 | Yes Not indicated There is no health care proxy, consider pursuit of guardianship if indicated ∗∗∗ |

| Responses: 304009028 | Yes, directive states: ∗∗∗ There is a copy in the patient's chart HCP has been asked to provide a copy No |

| Code status: 304000943 | Full DNR/DNI Partial Other: ∗∗∗ |

| Confirmed with: 304000944 | Patient Health care proxy, name: ∗∗∗ No health care proxy in place, next of kin: ∗∗∗ Not able to confirm code status at this time because of: ∗∗∗ |

| Blank single: 19,197 | Generic smart list for end user to develop. Choices appear in note |

HCP = health care proxy; DNR = do not resuscitate; DNI = do not intubate.

Appendix IV.

Clinical Reference Guide Subject Headings (as of June 2, 2020)a

| Reference Guide | Section Headings (and Select Descriptions) |

|---|---|

| Critical care wiki |

|

| Palliative care wiki |

|

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ICU = intensive care unit; POLST = Portable orders for life-sustaining treatment.

These guides were constantly in flux throughout the program. Remote communication liaison program participants were all encouraged to contribute to these reference guides by continually adding and editing, using their experiences to refine the guides in real time, so that all participants could benefit from newly acquired knowledge shared as quickly as possible.

References

- 1.Zapana V., Jr. A Son's story: Texts from my father, in Elmhurst hospital. The New Yorker. April 13, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fausto J., Hirano L., Lam D. Creating a palliative care inpatient response plan for COVID-19-the UW medicine experience. J pain symptom Manag. 2020;60:e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams C. Goals of care in a pandemic: our experience and Recommendations. J pain symptom Manag. 2020;60:e15–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin K.M., Karas M.G., Ivascu N.S., Lief L. Hospital Preparedness for COVID-19: a Practical guide from a critical care Perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1337–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1037CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]