Abstract

As we have previously demonstrated that some breast cancer cell lines secrete DJ‐1 protein, we examined here whether breast cancer cells secrete DJ‐1 protein in vivo. To this end, the levels of DJ‐1 protein present in 136 specimens of nipple fluid was examined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The average concentration of DJ‐1 protein detected in diluted samples from 47 patients with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was 22.4 ng/mL, while it was 18.6 ng/mL in 26 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). In contrast, the average DJ‐1 concentration in samples from 63 women with benign lesions was 2.7 ng/mL, demonstrating that higher DJ‐1 protein levels were detected in nipple fluid in the presence of cancer cells than in the presence of benign lesions (P < 0.0001). When a cut‐off level of 3.0 ng/mL was applied, the higher level of DJ‐1 was shown to be of significant clinical value for predicting the presence of breast cancer (85.9% specificity, 75% sensitivity; P < 0.0001). Multivariate logistic analysis that included established factors such as nipple discharge cytology, ductoscopic cytology, and carcinoembryonic antigen level further showed that the level of DJ‐1 protein alone is of significant value for predicting the presence of breast cancer. Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization also showed that the low expression of DJ‐1 protein, despite high mRNA expression, was significantly correlated with high DJ‐1 protein levels in the nipple fluid. These data indicate that breast cancer cells secrete DJ‐1 protein in vivo, and that its level is a potential indicator of breast cancer in patients with nipple discharge. (Cancer Sci 2012; 103: 1172–1176)

Nipple discharge is a common complaint among women that is classified as normal or abnormal depending on features such as laterality, cyclic variation, quantity, or color.1, 2, 3 Although the majority of cases of nipple discharge are due to benign conditions such as intraductal papilloma, ductal ectasia, or plasma cell mastitis, approximately 10–20% of cases are attributable to malignant conditions such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), or the early clinical stages of invasive ductal and/or lobular carcinoma.4, 5 While it has been proposed that patients with nipple discharge should undergo biopsy or subareolar exploration based on the presence or absence of a palpable mass, less invasive, non‐surgical methods can also be applied in these cases.6, 7

The cytological evaluation of nipple discharge obtained directly from the nipple is widely used for clinical examination. In previous investigations of asymptomatic women with nipple discharge, a definitive diagnosis of malignancy was not possible in approximately 70% of cases8, 9; however, cytology has been improved by new techniques such as “duct lavage” and “duct endoscopy” (ductoscopy).10, 11, 12 These newer techniques are designed to examine the abnormal cells that travel from the ducts to the nipple. Moreover, biological markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) or human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2 have also been analyzed in liquid specimens,13, 14, 15 although this technique is associated with a high false‐negative rate. Therefore, the identification of a new biomarker capable of detecting the presence of breast cancer is needed in patients with nipple discharge.

Although there are a number of candidate biomarkers for the detection of breast cancer, we focused on DJ‐1 in the present study because the results of a previous investigation that used immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization to examine 273 invasive ductal carcinomas (IDCs) and 41 DCISs of the breast suggested that DJ‐1 may be secreted by cancer cells.16 We revealed in this previous study that DJ‐1 protein was expressed at low levels although there was high expression of DJ‐1 mRNA in the MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cell line. Rather, DJ‐1 protein was detectable in the culture medium of the cells. Such an expression pattern, which may reflect secretion, was further found to predict poor outcome in patients with IDC.

DJ‐1 was originally reported to be a putative oncogene with transforming activity in mouse NIH‐3T3 cells, both alone and in synergy with H‐ras.17 It is also a negative regulator of phosphatase and tensin homolog deletion on chromosome 10 (PTEN).18 Although the physiological and/or pathological role of DJ‐1 secretion by cancer cells is not clearly understood, it has been reported that a high level of DJ‐1 is detectable in the peripheral blood of patients with breast cancers.19, 20 DJ‐1 was localized both in the cytoplasm and nucleus and is translocated by stress or mitogen stimulation of cells.17 After oxidative stress, DJ‐1 is translocated to mitochondria,21, 22 and oxidation of DJ‐1 protein facilitates secretion through microdomains.20 We therefore hypothesized that breast cancer cells would directly secrete DJ‐1 into the duct, and that a high level of DJ‐1 would subsequently be detectable in nipple fluid.

In order to test this hypothesis, we examined 136 samples of nipple fluid by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The clinical significance of the level of DJ‐1 protein detected in the nipple fluid was compared with established techniques such as CEA levels as detected by diagnostic patch, nipple discharge cytology, and ductoscopic cytology. The detection of a high level of DJ‐1 protein in nipple discharge was shown to be of clinical relevance for predicting the presence of malignancy.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

After Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent had been obtained, nipple fluid specimens were collected from 136 Japanese patients at the Department of Breast Surgery, Cancer Institute Hospital between 2006 and 2009. The 136 patients had a chief complaint of nipple discharge, and the presence or absence of cancer was based on whether or not disease was present in a given breast. Both cytologic and histopathologic examinations were performed for all patients, and their clinical features are listed in Table 1. The cases classified as benign were followed for a median period of 11.5 months and cytologic examinations were repeated two or three times, while all of the specimens from women with breast cancer were collected before definitive diagnosis and/or treatment. CEA levels in the nipple fluid were estimated using the diagnostic patch method (Mammotec; Mochida Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1.

Clinical features of 136 patients with nipple discharge

| Clinical variables | Benign (n = 63) | Malignant (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤50 | 43 | 45 |

| 50< | 20 | 28 |

| Menopausal status | ||

| Premenopausal | 42 | 46 |

| Postmenopausal | 21 | 27 |

| Location | ||

| Right | 30 | 37 |

| Left | 33 | 36 |

| History of breast cancer | ||

| Present | 4 | 5 |

| Absent | 59 | 68 |

Nipple fluid

An expert surgeon (MM) collected nipple fluid following cleansing of the nipple with alcohol. The breast was then gently massaged from the chest wall towards the nipple, and fluid in the form of droplets was collected in capillary tubes. Samples were immediately frozen at −80°C. If keratin plugs were obtained, they were removed with an alcohol swab and the massage procedure was repeated. After the collection of nipple fluid, mammary ductoscopy was performed as described previously, and the lavage fluid was used for cytology.23

ELISA

Frozen samples of nipple fluid were resuspended by crushing the tube into phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). After a preliminarily experiment to determine the appropriate dilution for each sample, all samples were diluted at a constant ratio of 100 μL of PBS buffer to 1 μL of nipple fluid in order to ensure that protein levels were comparable among samples. The level of DJ‐1 was measured using a sandwich solid‐phase ELISA kit (DJ‐1/PARK7 ELISA kit; CycLex, Nagano, Japan). ELISA tests were repeated three times. The concentration of DJ‐1 in each diluted sample was calculated using a standard curve.

Immunohistochemistry

We stained 3‐μm thick paraffin sections with a monoclonal antibody against human DJ‐1 (3E8; Medical and Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan). Briefly, after blocking endogenous peroxidase activity, the antigen was retrieved in 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) by autoclaving for 10 min. The sections were then allowed to cool to room temperature and incubated overnight with the anti‐DJ‐1 antibody, diluted 10 000‐fold. The sections were subsequently stained using Simple Stain MAX PO (Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan), visualized using Stable 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB) solution (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA), and followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. Three observers (MO, KI, and BT) judged the expression of DJ‐1 protein by breast cancer cells independently, and representative areas of both cancerous and non‐cancerous tissues were captured as digital images when all three observers judged that the staining intensity in more than 10% of cancer cells was distinctly lower than that in the non‐cancerous mammary gland epithelium from the same individual. If the average level of staining intensity in the cancerous area was confirmed to be two times lower than that in the non‐cancerous area using an image analyzer (WinROOF, Mitani, Tokyo, Japan), the case was categorized as having low expression. Otherwise, the expression was judged to be retained.

In situ hybridization

cRNA probes for in situ hybridization to detect DJ‐1 were generated with T7 RNA polymerase promoter region–tailed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers (sense primer: 5′‐ATGACTTCCAAGCTGGCCGT‐3′; antisense primer: 5′‐CTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTTGTAAGAATCAGGCCGTCT‐3′). The PCR products were transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase and labeled with digoxigenin‐dCTP (DIG in vitro transcription kit; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Primers were designed from the human DJ‐1 mRNA sequence with Primer Express, version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and we used the primer sequences for β‐2‐microglobulin mRNA as an internal positive control. The specificity of the PCR‐generated templates was confirmed by direct sequencing.

In situ hybridization was carried out as follows: 3‐μm thick sections were deparaffinized and treated with 10 μg/mL proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics) for 30 min at 37°C. The sections were then post‐fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, treated with 0.2 N HCl, and acetylated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 mol/L triethanolamine (pH 8.0) for 10 min each. After treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 1 h, the sections were dehydrated and air‐dried. Hybridization mixture (50 μL; mRNA in situ Hybridization Solution; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) containing 0.5 μL of each cRNA probe was loaded onto each section and hybridized for 16–18 h at 50°C. After hybridization, the sections were rinsed briefly in 5× standard saline‐citrate (SSC) (1× SSC: 0.15 mol/L NaCl and 0.015 mol/L sodium citrate), then washed in 50% formamide/2× SSC for 30 min at 55°C. After rinsing in TNE buffer (10 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mol/L NaCl) for 10 min at 37°C, the sections were treated with 10 μg/mL RNase A (Roche Diagnostics) for 30 min at 37°C. After a further 10‐min rinse in TNE buffer at 37°C, the sections were subjected to stringent sequential washes in 2× SSC, 0.2× SSC, and 0.1× SSC for 20 min each at 55°C. After three 5‐min rinses in TBS‐2T (0.01 mol/L Tris–HCl, pH 7.5; 300 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% Tween‐20) and a 10‐min rinse in 0.5% casein/TBS (0.01 mol/L Tris–HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mmol/L NaCl), the sections were reacted sequentially with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated rabbit anti‐DIG antibody diluted 1:400 (DAKO), 0.7 μmol/L biotinylated tyramide solution, and an HRP‐conjugated streptavidin antibody diluted 1:500 (DAKO) for 15 min each at room temperature. Finally, mRNA localization was visualized with a DAB Liquid System (DAKO). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted for viewing. In a similar way to evaluate immunohistochemical staining, non‐cancerous mammary gland was used as an internal control for mRNA DJ‐1expression.When the staining intensity was more than 10% of cancer cells was higher than that in the non‐cancerous mammary gland epithelium, the case was categorized as having high expression. And when the staining intensity in more than 10% of cancer cells was lower than that in the non‐cancerous mammary gland epithelium, the case was judged as having low expression. Otherwise, the case was judged as having maintained the expression.

Statistical analysis

We applied Student's t‐tests when comparing two independent groups. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn in order to determine the threshold level of DJ‐1 protein. Logistic regression was applied to identify the clinical and biological parameters likely to predict the presence of cancer. In all instances, significance was set at P < 0.05. All of the data were analyzed with JMP® Statistical Discovery Software 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Subjects

Table 1 lists the clinical features of the 136 nipple fluid samples divided according to the types of breast lesion from which they originated: 73 cases were malignant, and 63 were benign. Among the clinical variables (age, menopausal status, location, or history of breast cancer), none was related to the presence of breast lesions.

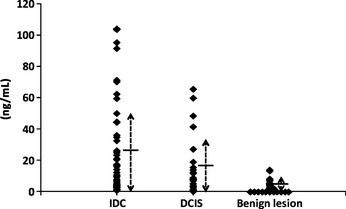

DJ‐1 expression level and histologic type

The levels of DJ‐1 expression according to histologic type are shown in Table 2 and the distribution of DJ‐1 level was drawn by scattered graph (Fig. 1). The average level of expression in the diluted samples was 22.4 ng/mL in the 47 IDC cases, and 18.6 ng/mL in the 26 cases of DCIS. In contrast, the average DJ‐1 expression level in the fluid obtained from the 63 patients with benign lesions (62 cases were diagnosed as papilloma and one as fibrocystic disease) was 2.7 ng/mL. No correlations between DJ‐1 levels and tumor size, lymph node status, histologic grade, or estrogen receptor status were observed.

Table 2.

DJ‐1 protein levels according to histologic type

| Histologic type | No. | Average DJ‐1 level (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 47 | 22.4 (0.5–104.4) |

| DCIS | 26 | 18.6 (0.6–65.6) |

| Benign lesion | 63 | 2.7 (0–14.1) |

| Papilloma | 62 | 2.7 |

| Fibrocystic disease | 1 | 3.8 |

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

Figure 1.

Scattered graph of DJ‐1 protein level according to the histologic type. DJ‐1 protein levels according to invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and benign lesion were drawn by the scattered graph. Dotted line with arrows shows the extent of standard deviation and short horizontal line shows the mean value of DJ‐1 protein level.

Sensitivity and specificity of the detection of DJ‐1 protein levels

Using a ROC curve, the cut‐off level of DJ‐1 expression that could successfully distinguish the benign and malignant categories were estimated to be 3.0 ng/mL, which was found to have a sensitivity of 85.9% (73/85) and a specificity of 75.0% (48/64) (Table 3). Univariate analysis showed that the DJ‐1 level in nipple fluid was a significant factor that differentiates between cancerous and benign conditions (P < 0.0001). Other factors such as the CEA level estimated using a diagnostic patch (56.5% sensitivity, 77.1% specificity; P < 0.0009), nipple discharge cytology (19.0% sensitivity, 100% specificity; P < 0.0001), and ductoscopic cytology (40.8% sensitivity, 98.1% specificity; P < 0.0001) were also significantly predictive of cancer when nipple fluid was analyzed. Multivariate conditional logistic regression analysis including these factors selected only DJ‐1 expression as significant (P = 0.0301) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of the predictive factors

| DJ‐1 | CEA | Nipple discharge cytology | Ductoscopic cytology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | 85.9 | 56.5 | 19.0 | 40.8 |

| Specificity (%) | 75.0 | 77.1 | 100 | 98.1 |

| PPV (%) | 82.0 | 70.3 | 100 | 95.2 |

| NPV (%) | 80.0 | 64.9 | 54.8 | 64.6 |

NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the predictive value for breast carcinoma

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P‐value | Hazard rate | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| DJ‐1, cut off level; 3.0 ng/mL | <0.0001 | 13.7 | 3.239–58.470 | 0.0301 |

| CEA, cut off level; 400 ng/mL | 0.0009 | 0.1622 | ||

| Nipple discharge cytology | 0.0054 | 0.9721 | ||

| Ductoscopic cytology | <0.0001 | 0.9785 | ||

CI, confidence interval.

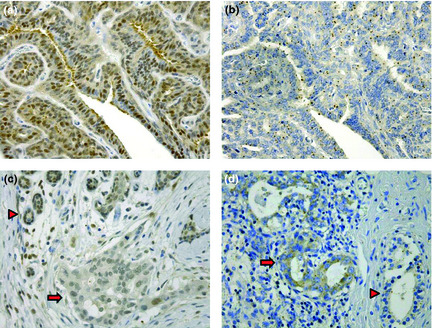

DJ‐1 expression levels in tumor tissue and nipple fluid

All eight papillomas examined for DJ‐1 expression by immunostaining and in situ hybridization demonstrated high expression of both DJ‐1 protein and mRNA (Fig. 2a,b). The average level of DJ‐1 protein in nipple fluid samples from women with these papillomas was 1.7 ng/mL, whereas various proportions of cancer cells exhibited decreased DJ‐1 protein expression in the 31 cancer cases, even though the mRNA expression level was maintained or high. The levels of DJ‐1 protein detected in the nipple fluid samples from the 31 women with cancer were high (average, 15.5 ng/mL); however, DJ‐1 protein expression was judged to be low in 13 (42%) of those cases (Fig. 2c,d). The average level of DJ‐1 protein in the nipple fluid from those women (24.4 ng/mL) was significantly higher than that in samples from the other 18 women with cancer (9.1 ng/mL) (P = 0.02).

Figure 2.

Expression of DJ‐1 in papilloma and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). (a) A specimen immunostained for DJ‐1 showing the retention of DJ‐1 expression in papilloma cells. (b) In situ hybridization of DJ‐1 corresponding to (a) showing distinct DJ‐1 mRNA expression in the papilloma cells. (c) Low expression of DJ‐1 protein in cells of IDC. Arrow head indicates non‐cancerous mammary glands, and cancerous area is marked by arrow. (d) In situ hybridization of DJ‐1 corresponding to (c) demonstrating distinct mRNA expression in ductal carcinoma cells (original magnification × 400). Arrow head indicates non‐cancerous glands, and cancerous area is marked by arrow.

Discussion

Nipple fluid contains more than 1000 protein species,24 including DJ‐1. This protein is detectable in nipple fluid by ELISA, and we have shown in this study that its high level is significantly associated with the presence of cancer cells. We detected high levels of DJ‐1 protein in samples of nipple fluid from not only patients with IDC, but also from those with DCIS.

As nipple fluid samples are rich in protein and are viscous, they were diluted 1:100 in order to adjust the concentration within the range recommended by the manufacturer's protocol for detection using the DJ‐1 ELISA kit (0.55–100 ng/mL). None of the fluid samples from the cancer patients investigated in this study contained DJ‐1 concentrations lower than the detection limit (0 of 73 cases). As for benign conditions, ELISA did not detect the DJ‐1 protein in 11 of 63 (17.5%) lesions, although one sample exceeded the recommended high range of the kit (104.4 ng/mL). This case was found to involve IDC in the given breast, and was included in the data as it was stated in the user's manual that no hook effect is observed with DJ‐1 concentrations lower than 200 ng/mL. The actual DJ‐1 concentration detected in the nipple fluid of this patient was approximately 10 mg/mL (104.4 × 100 ng/mL).

The majority of the nipple fluid samples examined in this study contained total protein concentrations between 30 and 300 mg/mL, and DJ‐1 protein was found to be abundant in the samples. Of the 73 cancer cases, DJ‐1 levels in nipple fluid were higher than 1 mg/mL in 39 cases (53.4%). In contrast, no benign cases were found to express DJ‐1 at a concentration >1 mg/mL, with the exception of one case (1.6%), in which atypical duct epithelial cells presented with calcification in the breast biopsy specimen.

The same DJ‐1 ELISA kit used in this study has previously been used to detect DJ‐1 protein levels in sera from normal control individuals and Parkinson's disease patients.25 In that study, it was found that DJ‐1 levels in the sera of most participants, including the healthy controls (n = 194), were under 300 ng/mL, which was chosen as the cut‐off level. In a further study, DJ‐1 levels in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were found to range 8.9–80.4 ng/mL despite the use of sophisticated detection methods.26 Although DJ‐1 may be translocated by oxidative stress, it is a relatively abundant cellular protein of unknown function, and has been detected in various human body fluids,25, 26, 27, 28 the average DJ‐1 level detected in nipple fluid from patients with breast cancer shown in this study was much higher than previously reported in other body fluids. Similarly, CEA levels in the nipple fluid in the patients with breast cancer were reported to detect about 100 times higher than those in the sera.29 Protein levels such as DJ‐1 and CEA may be concentrated in the nipple fluid.

At the tissue level, it has been previously demonstrated that the majority of ductal carcinoma cells express high levels of DJ‐1 mRNA, although low expression of DJ‐1 protein was detected in 13 (42%) of 31 women with ductal carcinoma.16 Le Naour et al.19 reported similar low expression of DJ‐1 protein. A pattern of high mRNA expression but low protein expression is known to occur in several physiological processes, including secretion. In our study, only low levels of DJ‐1 were detected in the samples of nipple fluid from papilloma cases, and decreased protein expression was not detected. Furthermore, the average level of DJ‐1 protein detected in fluid specimens from women with carcinomas exhibiting such an expression pattern was higher than that detected in samples from women with carcinoma lacking this secretion expression pattern. These data indicate that carcinoma cells directly secrete DJ‐1 protein into the duct; as a result, DJ‐1 levels are high in the nipple fluid from women with breast cancer.

Identifying the level of DJ‐1 protein that may be used as a biomarker may aid in the screening of early breast cancer using not only pathological nipple fluid, but also aspiration fluid. Previous proteomic analyses have shown that women with and without breast cancer have different proteomic expression patterns.30, 31 Though our data were not conducted by 2‐D analysis or surface‐enhanced laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (SELDI‐TOF‐MS), we believe that the level of DJ‐1 detected in nipple fluid could support, in part, a more accurate diagnosis of breast cancer in combination with other biomarkers such as gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP)‐15, α1‐acid glycoprotein, basic fibroblast growth factor, and HER2.32, 33, 34

In summary, our findings suggest that the level of DJ‐1 protein in nipple fluid is a potentially useful marker for the detection of breast cancer, with sensitivity and specificity superior to those of other clinical parameters, including cytology.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, a Ministry of Defense Grant (Osamu Matsubara and Keiichi Iwaya), and a Grant‐in‐Aid from the Japanese Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research (Masujiro Makita).

References

- 1. Devitt JE. Management of nipple discharge by clinical findings. Am J Surg 1985; 149: 789–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vargas HI, Romero L, Chlebowski RT. Management of bloody nipple discharge. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2002; 3: 157–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamed H, Fentiman IS. Benign breast disease. Int J Clin Pract 2001; 55: 461–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Louie LD, Crowe JP, Dawson AE et al Identification of breast cancer in patients with pathologic nipple discharge: does ductoscopy predict malignancy? Am J Surg 2006; 192: 530–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Montroni I, Santini D, Zucchini G et al Nipple discharge: is its significance as a risk factor for breast cancer fully understood? Observation study including 915 consecutive patients who underwent selective duct excision. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 123: 895–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gülay H, Bora S, Klliçturgay S, Hamaloğlu E, Göksel HA. Management of nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg 1994; 178: 471–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simmons R, Adamovich T, Brennan M et al Nonsurgical evaluation of pathologic nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2003; 10: 113–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krishnamurthy S, Sneige N, Thompson PA et al Nipple aspirate fluid cytology in breast carcinoma. Cancer 2003; 99: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takeda T, Matsui A, Sato Y et al Nipple discharge cytology in mass screening for breast cancer. Acta Cytol 1990; 34: 161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khan SA, Mangat A, Rivers A, Revesz E, Susnik B, Hansen N. Office ductoscopy for surgical selection in woman with pathologic nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 3785–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamamoto D, Shoji T, Kawanishi H, Nakagawa H, Haijima H, Gondo H. A utility of duoctoscopy and fiber optic ductoscopy for patients with nipple discharge. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001; 70: 103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sauter ER, Klein‐Szanto A, Macgibbon B, Ehya H. Nipple aspirate fluid and ductoscopy to detect breast cancer. Diagn Cytopathol 2010; 38: 244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mori T, Inaji H, Koyama H et al Evaluation of an improved dot‐immunobinding assay for carcinoembryonic antigen determination in nipple discharge in early breast cancer: results of multicenter study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1992; 22: 371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao Y, Verselis SJ, Klar N et al Nipple fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and prostate‐specific antigen in cancer‐bearing and tumor‐free breasts. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 1462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Motomura K, Koyama H, Noguchi S, Inaji H, Azyma C. Detection of c‐erbB‐2 gene amplification in nipple discharge by means of polymerase chain reaction. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1995; 33: 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsuchiya B, Iwaya K, Kohno N et al Clinical significance of DJ‐1 as a secretion molecule: retrospective study of expression of both DJ‐1 mRNA and protein in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Histopathology 2011; doi: 10.1111/(ISSN)1349-7006 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagakubo D, Taira T, Kitaura H et al DJ‐1, a novel oncogene which transforms mouse NIH3T3 cells in cooperation with ras. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 231: 509–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim RH, Peters M, Jang YJ, Shi W, Pintilie M, Fletcher GC. DJ‐1, a novel regulator of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cancer Cell 2005; 7: 263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Naour F, Misek DE, Krause MC et al Proteomic‐based identification of RS/DJ‐1 as a novel circulating tumor antigen in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 3328–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsuboi Y, Munemoto H, Ishikawa S, Matsumoto K, Iguchi‐Ariga SM, Ariga H. DJ‐1, a causative gene product of a familial form of Parkinson's disease, is secreted through microdomains. FEBS Lett 2008; 582: 2643–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Canet‐Aviles RM, Wilson MA, Cookson MR et al The Parkinson's disease protein DJ‐1 is neuroprotective due to cysteine‐sulfinic acid‐driven mitochondrial localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 9103–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li HM, Niki T, Taira T, Iguchi‐Ariga SMM, Ariga H. Association of DJ‐1 with chaperones and enhanced association and colocalization with mitochondrial Hsp 70 by oxidative stress. Free Radiac Res 2005; 39: 1091–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Makita M, Akiyama F, Gomi N, Iwase T, Kasumi F, Sakamoto G. Endoscopic and histologic findings of intraductal lesions presenting with nipple discharge. Breast J 2006; 12(5 Suppl 2): S210–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuerer HM, Goldknopf IL, Fritsche H, Krishnamurthy S, Sheta EA, Hunt KK. Identification of distinct protein expression patterns in bilateral matched pair breast ductal fluid specimens from women with unilateral invasive breast carcinoma. High‐throughput biomarker discovery. Cancer 2002; 95: 2276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maita C, Tsuji S, Yabe I et al Secretion of DJ‐1 into the serum of patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 2008; 431: 86–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hong Z, Shi M, Chung KA et al DJ‐1 and α–synuclein in human cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers of Parkinson's disease. Brain 2010; 133: 713–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tian M, Cui YZ, Song GH et al Proteomic analysis identifies MMP‐9, DJ‐1 and AIBG as overexpressed proteins in pancreatic juice from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Cancer 2008; 8: 241–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He XY, Liu BY, Yao WY et al Serum DJ‐1 as a diagnostic marker and prognostic factor for pancreatic cancer. J Dig Dis 2011; 12: 131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foretova L, Garber JE, Sadowsky NL et al Carcinoembryonic antigen in breast nipple aspirate fluid. Cancer Epidemiol Biomakers Prev 1998; 7: 195–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sauter ER, Shan S, Hewett JE et al Proteomic analysis of nipple fluid using SELDI‐TOF‐MS. Int J Cancer 2005; 114: 791–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alexander H, Stegner AL, Wagner‐Mann C, Bois GCD, Alexander S, Sauter ER. Proteomic analysis to identify breast cancer biomarkers in nipple aspirate fluid. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 7500–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sartippour MR, Zhang L, Lu M, Wang HJ, Brooks MN. Nipple fluid basic fibroblast growth factor in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14: 2995–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kuerer HM, Thompson PA, Krishnamurthy S et al High and differential expression of HER‐2/neu extracellular domain in bilateral ductal fluids from women with unilateral invasive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 601–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Knobbe CB, Revett TJ, Bai Y et al Choice of biological source material supersedes oxidative stress in its influence on DJ‐1 in vivo interactions with HSP90. J Proteome Res 2011; 10: 4388–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]