Abstract

During 2018 and 2019, the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover investigated the chemistry, morphology, and stratigraphy of Vera Rubin ridge (VRR). Using orbital data from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, scientists attributed the strong 860 nm signal associated with VRR to the presence of red crystalline hematite. However, Mastcam multispectral data and CheMin X‐ray diffraction (XRD) measurements show that the depth of the 860 nm absorption is negatively correlated with the abundance of red crystalline hematite, suggesting that other mineralogical or physical parameters are also controlling the 860 nm absorption. Here, we examine Mastcam and ChemCam passive reflectance spectra from VRR and other locations to link the depth, position, and presence or absence of iron‐related mineralogic absorption features to the XRD‐derived rock mineralogy. Correlating CheMin mineralogy to spectral parameters showed that the ~860 nm absorption has a strong positive correlation with the abundance of ferric phyllosilicates. New laboratory reflectance measurements of powdered mineral mixtures can reproduce trends found in Gale crater. We hypothesize that variations in the 860 nm absorption feature in Mastcam and ChemCam observations of VRR materials are a result of three factors: (1) variations in ferric phyllosilicate abundance due to its ~800–1,000 nm absorption; (2) variations in clinopyroxene abundance because of its band maximum at ~860 nm; and (3) the presence of red crystalline hematite because of its absorption centered at 860 nm. We also show that relatively small changes in Ca‐sulfate abundance is one potential cause of the erosional resistance and geomorphic expression of VRR.

Keywords: Mastcam, multispectral, laboratory, phyllosilicates, hematite, ferric iron

Key Points

Hematite likely controls the wavelength position of the ~860 nm absorption in Mastcam multispectral observations of drill targets

Lab results show that the ~860 nm band depth increases with ferric phyllosilicate abundance due to its ~800–1,000 nm feature

The reflectance maximum near 860 nm in pyroxene affects the ~860 nm band depth in spectra of lab mixtures and drilled rocks on Mars

1. Introduction

In August 2012, the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission's Curiosity rover landed in Gale crater, Mars (Figure 1 inset) with the main goal of assessing the landing site for evidence of habitability, including evidence for past liquid water on or near the surface (Grotzinger et al., 2012; Vasavada et al., 2014). Gale crater was chosen as the landing site in part because orbital data suggested the presence of minerals indicative of aqueous processes, including phyllosilicates and iron oxides (Grotzinger et al., 2012; Milliken et al., 2010). These detections of oxidized and hydrous phases are concentrated within the lower units of Aeolis Mons (known informally as Mt. Sharp), a ~5 km tall mound of sedimentary rocks near the center of Gale crater.

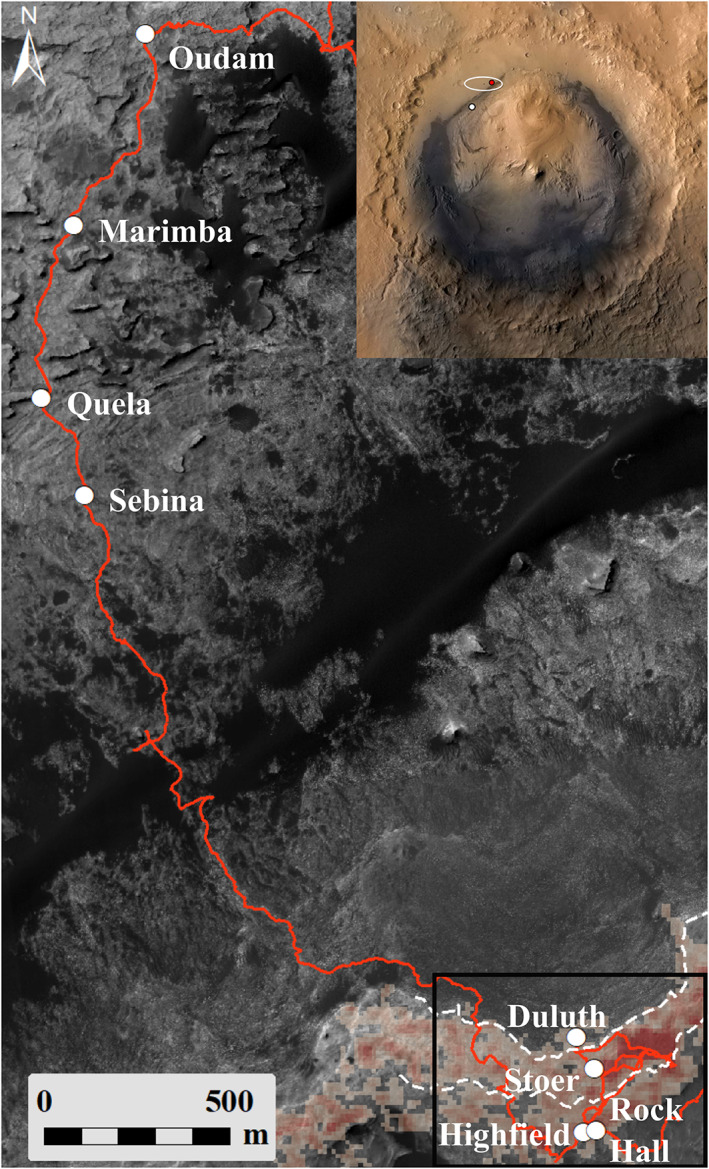

Figure 1.

Map showing part of the Murray formation and locations of the eight successful drill targets (white circles) discussed here. Base map is a 25 cm resolution HiRISE mosaic (NASA/JPL/University of Arizona). Red line is the rover traverse. Dashed white lines are the contacts of the Pettegrove Point and Jura members of the Vera Rubin ridge (see text). At lower right, CRISM data are overlain showing the strength of the 860 nm from low (gray) to high (red; Fraeman et al., 2016). Inset shows Gale crater, the landing ellipse, the Bradbury landing site (red circle), and VRR (white circle). Black box outlines area shown in Figure 2.

The geologic units that the Curiosity rover has traversed from its landing site to the flanks of Mt. Sharp have been divided into three stratigraphic groups: the Bradbury group, the Mt. Sharp group, and the Siccar Point group (Fraeman et al., 2016; Grotzinger et al., 2015). Within the Mt. Sharp group lies a package of dominantly subaqueous, lacustrine‐deposited rocks known as the Murray formation (Grotzinger et al., 2015; Stack et al., 2016). One highly anticipated target area for Curiosity's exploration of Mt. Sharp was Vera Rubin ridge (VRR), a ~6.5 km long by 200 m wide mesa‐like topographic feature that stands ~10 m above the surrounding units (Figure 2). VRR is distinct among the Murray deposits because of its apparent erosional resistance and association with a strong near‐infrared (IR) absorption feature seen from orbital imaging and spectroscopic data (e.g., Anderson & Bell, 2010; Milliken et al., 2010; Thomson et al., 2011). Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) data show that VRR has some of the strongest 530 and 860 nm band depths in the region, suggesting the presence of red crystalline hematite (α‐Fe2O3; Fraeman et al., 2013; Milliken et al., 2010; Morris et al., 1985). The presence and variation in abundance of crystalline hematite could be consistent with oxidized lake waters in Gale crater (Hurowitz et al., 2017; Rampe et al., 2017), which could in turn be consistent with a warmer, wetter climate on Mars that was much different from its current cold, dry climate.

Figure 2.

Map of the Vera Rubin ridge showing the location of the four successful drill targets (white circles) and the five unsuccessful drill targets (black circles) discussed here. Dashed white lines are the contacts of the Pettegrove Point and Jura members of VRR (Edgar et al., 2020). Overlain on the HiRISE base map is a CRISM parameter map showing the variations in the strength of the 860 nm signal (Fraeman et al., 2013).

Accurately identifying the mineral assemblage of rocks on Mars is vital to understanding the planet's paleoclimates but can be equivocal when orbital spectral data are the only resources available. Some minerals, especially those with strong visible colors such as hematite, can overwhelm the spectral signal and mask the presence of other minerals like ferric phyllosilicates. Quantitative X‐ray diffraction (XRD) measurements, from Curiosity's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument, of drilled samples throughout the Murray formation have helped identify ferric phyllosilicates in much larger abundances than anticipated from orbital data, as well as ferric minerals such as jarosite (KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6) and akaganeite (β‐Fe3+O(OH,Cl)) in minor abundances that were also not predicted from orbital data (Bristow et al., 2018; Rampe et al., 2017, 2020). This paper correlates multispectral parameters derived from Mastcam imaging data and Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) relative reflectance spectra to mineral abundances derived from CheMin XRD data to (a) help identify the effects of various Fe2+ and Fe3+‐bearing minerals on the interpretation of reflectance data and (b) help understand the mineralogy of Murray formation rocks in places that were not drilled and thus where the quantitative crystalline mineralogy is unknown. We focus on rocks that were drilled on and stratigraphically below VRR and that were analyzed by multiple instruments onboard the Curiosity rover. New laboratory reflectance studies also discussed in this paper provide important validation and ground truth benchmarks for both orbital and in situ remote sensing observations. Along with the spectral properties of the ridge, this paper investigates whether composition is affecting the erosional resistance of VRR. Finally, we discuss how the spectral, compositional, and mineralogic characteristics of VRR and the broader Murray formation help narrow down the possible hypotheses for the formation of these units.

2. Overview of the Murray Formation and VRR Science Campaigns

2.1. Overview of VRR

Most of the Murray formation, including VRR, is composed of laminated mudstone and thin beds of cross‐laminated sandstone (e.g., Edgar et al., 2020; Grotzinger et al., 2015). VRR has been mapped into two geomorphically distinct members, the lower Pettegrove Point member and the upper Jura member (Fraeman et al., 2018). The Pettegrove Point member is characterized by light‐toned, fractured, planar‐laminated mudstone, whereas the Jura member is darker toned, retains more craters, and has numerous depressions ~10 m in diameter exposing brighter‐toned, gray material (Edgar et al., 2020). The Jura and Pettegrove Point members are similar in composition to each other and the previously explored Murray formation deposits, with only minor variations in trace elements (Frydenvang et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020). Despite the chemical similarity, Mastcam multispectral data documented spectral variability similar to and in places greater than that observed in the underlying Murray rocks (Jacob et al., 2019). The most noticeable variations in multispectral data were in the presence or absence and depth of the 867 nm ferric absorption feature (Fraeman, Edgar, et al., 2020; Jacob et al., 2019).

VRR bedrock is variably reddish in visible color, with some locations appearing darker and more “purple” in approximate true color renderings of Mastcam images (Figure 3; Fraeman, Johnson, et al., 2020; Horgan et al., 2020); those locations correspond to areas with strong ferric absorptions in Mastcam multispectral data and ChemCam passive spectra (Fraeman, Edgar, et al., 2020). The Jura member exhibits especially strong color variations in Mastcam images, including bright “red” float rocks with strong hematite signatures and a dark “purple” capping unit with no hematite signatures. However, the most notable feature of the otherwise “purple” to “red”‐toned Jura is pervasive decameter‐scale patches of light‐toned and smooth “gray” bedrock in shallow topographic depressions (Horgan et al., 2020). Visible to near‐IR spectra of these regions collected by Curiosity exhibit a notable lack of short wavelength ferric absorptions, and instead are relatively flat, consistent with the presence of coarse‐grained iron oxides (cf. Johnson et al., 2019). The boundary between these two parts of the Jura (referred to as the “red” and “gray” Jura) can be mottled at the centimeter scale in Mastcam images and exhibits variable spectral properties (Horgan et al., 2020). Both red and gray Jura exhibit small and dark‐toned diagenetic features spectrally and chemically consistent with magnetite or hematite, but these features are much more prevalent in the gray bedrock (Horgan et al., 2019).

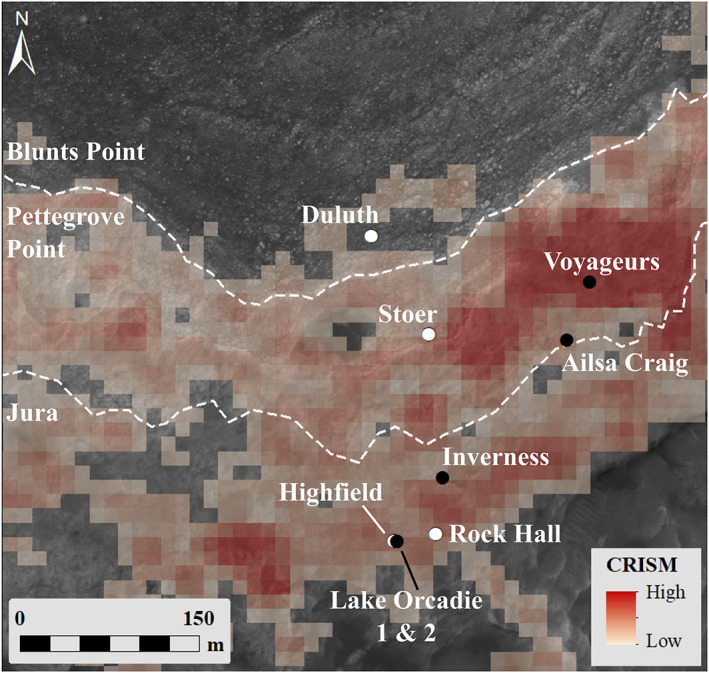

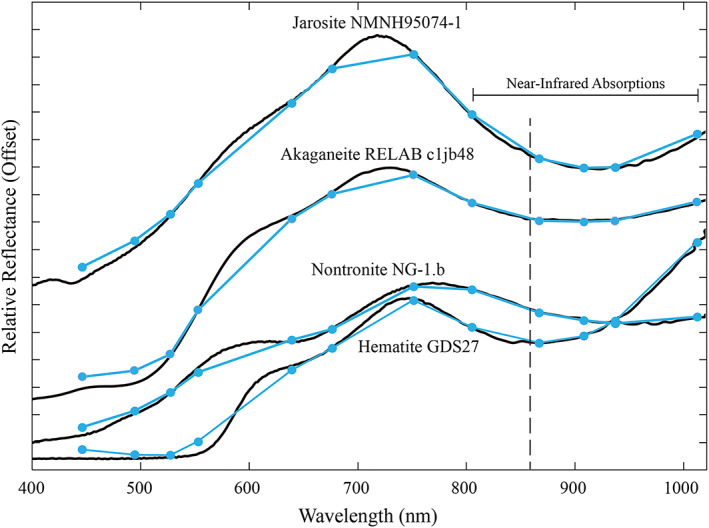

Figure 3.

Mastcam landscape mosaic of the Jura member of VRR, showing extreme color variations as seen in the white balanced RGB Bayer filters (mcam10419; Sol 1988).

2.2. VRR Science Campaign

Throughout the Murray formation, rocks were analyzed using the Mastcam cameras (Malin et al., 2017), the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI; Edgett et al., 2012), the ChemCam (Maurice et al., 2012; Wiens et al., 2012) instrument, the Alpha Particle X‐ray Spectrometer (APXS; Campbell et al., 2012), and the CheMin (Blake et al., 2012) instrument. The Murray formation rocks below VRR were drilled in eight locations, the early four targets are located in the Pahrump Hills member and the later four drill targets are in various other Murray formation groups. The four Pahrump Hills targets have a distinctly different elemental and mineralogical composition compared to the later four Murray and VRR drill targets (Rampe et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2020). For this reason, we will only be comparing the later four Murray drill targets (Oudam, Marimba, Quela, and Sebina) to the VRR drill targets.

During the campaign across the Murray formation a problem with the drill translation mechanism was discovered during a drill attempt on Sol 1536. Between December 2016 and May 2018, the Curiosity rover did not complete a successful drill. The area traversed during this time frame, including the majority of the Sutton Island member, was thus not analyzed by the CheMin instrument, and therefore, its quantitative crystalline mineralogy is unknown. Understanding the relationship of CheMin mineralogy and Mastcam and ChemCam spectral parameters in the successfully drilled locations could allow us to constrain the mineralogy of rocks that were unable to be drilled but were imaged by Mastcam and were observed with passive spectra by ChemCam.

While Curiosity was exploring VRR, a team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) developed a new method for drilling called Feed Extended Drilling using Percussion (FEDuP). The first successful drill sample acquired using FEDuP was Duluth, a target in the Blunts Point member just below VRR. Duluth and all the VRR drill targets (Stoer, Highfield, and Rock Hall) were drilled using FEDuP. Prior to the successful drill activity at Duluth, two drill campaigns were attempted on VRR using rotary‐mode drilling only. These two targets, Lake Orcadie and Lake Orcadie 2, did not produce full‐depth drill holes. Additionally, three other drill attempts using percussion on VRR were unsuccessful because the targeted rocks were too strong; the FEDuP algorithm worked as planned until the operation was aborted because of the resistance of the rock and the lack of sufficient forward progress of the drill.

Drill targets across VRR were predominantly chosen by the team to understand the chemical and mineralogical differences associated with the physical appearance of VRR rocks. Multispectral data, along with in situ analyses, were used by the team to determine if the chosen drill targets accurately represented the various types of VRR rocks, although as mentioned above, the physical strength of the rocks presented another constraint on the sampling strategy. The Stoer drill target was chosen to represent the red Pettegrove Point material, and Highfield was picked to represent the gray Jura material. Though Rock Hall is a VRR drill target, it was determined to be chemically distinct from the average Murray composition making it unique from any of the Jura or Pettegrove Point material. Rock Hall was tactically chosen as a drill target based on its physical characteristics that made this target drillable, unlike other red Jura targets.

One goal of this paper, and the VRR science campaign, is to understand the physical characteristics of VRR and to help determine why the ridge is erosionally resistant compared to the surrounding Murray units. Previous studies have used orbital spectral data to support the hypothesis that Mt. Sharp rocks have been cemented by sulfate or clay cements (Milliken et al., 2014). Additionally, studies on the mechanical properties of terrestrial sandstones have shown that compressive strength increases with the abundance of cement (Cook et al., 2014). In this paper, we compare the strength and composition of drill targets to determine if there is a compositional component causing variations in the strength of the rocks on and below VRR.

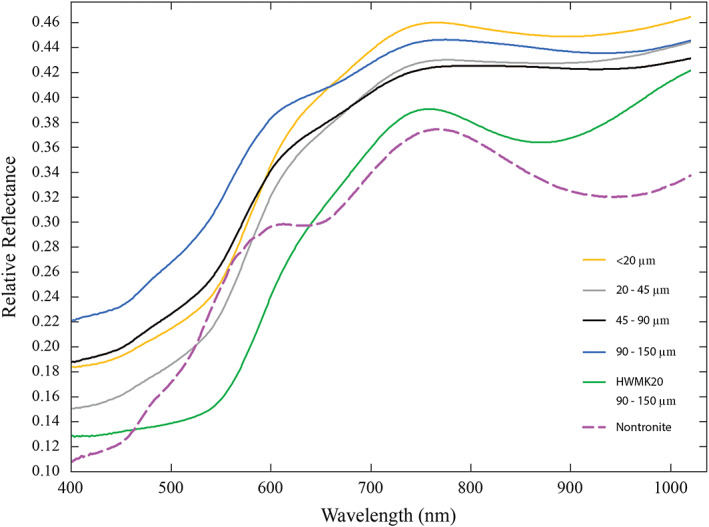

3. Background: Spectral Signatures of Ferric Minerals

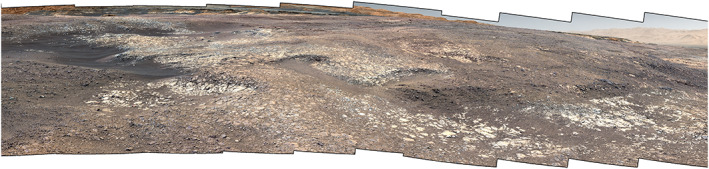

Numerous laboratory multispectral investigations of pure mineral samples show that red crystalline hematite has characteristic spectral absorptions near 530 and 860 nm and an absorption “edge” from ~500–700 nm (Figure 4; Bell et al., 1990; Morris et al., 1985, 1997). Early studies showed that the depth of the 860 nm absorption feature typically increases with increasing abundance of crystalline hematite (α‐Fe2O3; Morris et al., 1989). That same study also showed that nanophase hematite (particle size <10 nm) does not have the 860 nm absorption feature that is characteristic of more crystalline hematite. Nanophase hematite does, however, maintain the visible wavelength absorption edge similar to red crystalline hematite. Recent studies have shown that the depth of the 860 and 530 nm absorptions increase with decreasing grain size below ~100–200 μm (Johnson et al., 2019). Other minerals that have absorption features near 860 nm include jarosite, akaganeite, and ferric phyllosilicates (Figure 4; e.g., Morris et al., 1985). Previous studies have also shown that iron‐bearing phyllosilicates, like nontronite, have an absorption feature near 920 nm (Morris et al., 1995). Similar to hematite, the depth of phyllosilicate spectral absorption features is affected by both abundance and changes in grain size (Ehlmann et al., 2009; Roush et al., 2015).

Figure 4.

Laboratory spectra of ferric minerals with absorption features near 860 nm. Black solid lines denote laboratory spectra from either the USGS Digital Spectral Library (Kokaly et al., 2017) or the RELAB spectral library (Pieters, 1983). Colored lines and markers show the lab spectra convolved to Mastcam filters. ChemCam spectra provide high resolution up to a cutoff around 840 nm. The vertical black dashed line shows the location of the 860 nm absorption features discussed throughout the text. The akaganeite and jarosite spectra have been offset vertically by 0.1 and 0.3, respectively, for clarity. Vertical axis tick marks are at 0.05 increments.

The spectral signature of a natural sample, such as from rocks or soils on Mars, is a composite of the scattering properties of each mineral in the sample and the surrounding or encompassing matrix materials. This mixing is nonlinear, especially in visible to near‐IR wavelengths that are comparable in scale to the sizes of typical particles making up the surface (e.g., Johnson et al., 2004). The scattering properties of some minerals, especially of pigmenting minerals like hematite, can mask the spectral response of other minerals that are in the same sample. Laboratory mixing experiments of the type described below are helpful to understand the effects of mineral abundance and grain size on the spectral signature of natural surfaces acquired with remote sensing techniques.

4. Data Sets and Methods

4.1. Drilling Campaign Activities

Understanding how the drilling protocol has changed since December 2016 will showcase how the strength of Murray and VRR rocks has been calculated and used to investigate the erosional resistance of VRR. The observations discussed in this paper (supporting information Tables S1 and S2) were acquired on targets that were either successfully drilled or attempted to be drilled using the rover's Sample Acquisition, Processing, and Handling system (SA/SPaH; Anderson et al., 2012). Information about the hardness of the rocks can be obtained from the ancillary data of the drill (Peters et al., 2018). Under the original drilling protocol, loading of the drill bit was maintained by the drill's translation mechanism, which moves along a linear path independently of a set of stabilizers. The robotic arm loads the stabilizers against the targeted rock slab, thus allowing the robotic arm to remain fixed even as the drill mechanism translates into the rock. During the new FEDuP protocol, the drill system is extended past the robotic arm's stabilizers and left there. In this configuration, instead of the drill translation mechanism providing the loading on the bit, the robotic arm must do this work. Therefore, the drill is not stabilized against the targeted rock, and the system must perform periodic checks throughout the drilling operation and adjust the arm to guard against side loading the drill bit. Changes in the new FEDuP protocol include the robotic arm providing the reaction force against the rock instead of the drill feed mechanism, a rotary‐only component, the weight on the drill bit has been increased, and the targeted borehole depth has been decreased. Four of the targets analyzed in this study were drilled using the nominal drilling protocol, while the later four targets were drilled after the implementation of FEDuP because of the malfunction with the SA/SPaH system.

Once a target has been selected as a potential drill sample, the bedrock is brushed using the steel wire Dust Removal Tool (DRT). After brushing but before drilling, Mastcam multispectral, APXS, and ChemCam observations are taken of the DRT spot to further evaluate the composition of the rock to see if it will meet the desired scientific goals. If the drilling activity achieved full depth (~40 mm), the powdered sample is processed and ultimately delivered to the internal instruments including CheMin. Postdrill Mastcam multispectral, APXS, and ChemCam observations are taken to document the composition of the drill tailings produced around the drill hole. After the sample is processed by the internal laboratories, CheMin and the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument, the remaining sample is dumped from the drill bit onto the surface near the drill hole and analyzed again by Mastcam, APXS, and ChemCam.

4.2. Mastcam Observations and Calibration

Of the two stereo cameras that make up the Mastcam instrument, the left camera has a focal length of 34 mm (M‐34), and the right camera has a focal length of 100 mm (M‐100) (Bell et al., 2017; Malin et al., 2017). Each camera contains a CCD, a Bayer color filter array, and an eight‐position color filter wheel (Bell et al., 2017; Malin et al., 2017). The Bayer color filter allows Mastcam to obtain “true color” images of the surface to aid in geologic interpretations of units surrounding the rover. Two of the positions on the filter wheel are solar filters to allow for imaging of the Sun. The remaining 12 filter positions allow for multispectral imaging at nine unique wavelengths covering a range of 445–1,013 nm. Calibration of the raw images converts the data number (DN) values to physically meaningful radiometric quantities of reflectance using near‐simultaneous observations of an onboard color and grayscale calibration target.

Mastcam multispectral observations were calibrated and converted to radiance factor (unitless I/F, where I is the measured radiance and πF is the incident solar irradiance) using the standard calibration pipeline at Arizona State University (ASU) as described in Bell et al. (2017) and Wellington et al. (2017). A dust model correction was implemented shortly after Curiosity landed to account for accumulating dust on the Mastcam calibration target. The dust model used is similar to that used for the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) as described in Kinch et al. (2013, 2015), because the Mastcam calibration target is a flight spare of the MER/Pancam calibration targets. Relative reflectance spectra were extracted from Mastcam observations at select regions of interest (ROIs) that were chosen from spectrally and physically uniform materials (e.g., Wellington et al., 2017). Because I/F data are created using near‐simultaneous calibration target observations, and the dust correction is part of the standard calibration pipeline, the large Martian dust storm during summer 2018 did not significantly affect the derived reflectance values under both nominal and high opacity conditions. This was verified by comparing spectra from two DRT targets (Stranraer and Voyageurs) from the same slab of bedrock, taken before the dust storm began and during the storm. Both show essentially the same Mastcam multispectral results, to within the typical uncertainties of the data.

The longer focal length and wider field of view (FOV) of the M‐34 camera allows for landscape images to capture large‐scale transitions in the geologic scene, while the M‐100's 3 times higher resolution and narrower FOV allows for a more detailed examination of the textures and fine‐scale features of the surface. During the VRR campaign, M‐34 multispectral images were taken to analyze the spectral and mineralogic transitions between the Pettegrove Point and Jura members on a large‐scale and the differences between the various colors of material within an individual member. M‐100 multispectral images were used to augment VRR multispectral coverage and to provide greater detail of targets such as drill holes, drill tailings, diagenetic features, and many other fine‐scale features.

4.3. Band Parameter Calculations

Mastcam multispectral band parameters were used to characterize the spectral differences in the various units and drill targets described below (e.g., Wellington et al., 2017). We focus primarily on the depth of the 535 nm absorption feature, the 860 nm absorption feature, and the slope of the red absorption edge (represented mathematically by the red/blue ratio; Figure 4). Table 1 describes how each band parameter was calculated, while Table S1 lists the Mastcam multispectral observations discussed throughout the paper. Uncertainties for the Mastcam band parameters were estimated using the 1‐σ standard deviation of a population of potential band depth values modeled for each target. The error of the Mastcam reflectance values was modeled using a uniform distribution of ±2% of the observed reflectance value. This 2% is the worst case estimate of the relative band‐to‐band‐derived reflectance uncertainties estimated from preflight calibration of the Mastcam instrument (Bell et al., 2017). From the uniform distribution of the various filters used for band depth calculations, a population of ~100 band depths was modeled, and the 1‐σ standard deviation of this population was used as the uncertainty.

Table 1.

Mastcam (_M) and ChemCam (_CC) Spectral Band Parameter Calculations

| Symbol | Description | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| BD527_M | 527 nm band depth (446 to 676 nm continuum) | BD527 = 1 − (R*527/continuum) |

| Continuum = 0.648 × R*446 + 0.352 × R*676 | ||

| BD867_M | 867 nm band depth (751 to 1,012 nm continuum) | BD867 = 1 − (R*867/continuum) |

| Continuum = 0.556 × R*751 + 0.444 × R*1012 | ||

| RB_M | Slope of red absorption edge (676 to 446 nm ratio) | RB = R*676/R*446 |

| BD535_CC | 535 nm band depth (500 to 600 nm continuum) | BD535 = 1 − (R535/continuum) |

| Continuum = 0.65 × R500 + 0.35 × R600 | ||

| RB_CC | Slope of red absorption edge (670 to 440 nm ratio) |

RB = R670/R440 |

| S7584_CC | 750 to 840 nm slope | S7584 = (R840 − R750)/(840–750) |

Although the dump piles of powdered material analyzed by CheMin would be the ideal material to use in comparing spectral parameters to quantitative mineralogy, oftentimes, the dump piles do not provide clean, reliable Mastcam multispectral data. Of the eight targets discussed in this paper that have dump piles, about half of them were windswept into thin piles, which resulted in the multispectral results being contaminated with spectral properties of the material onto which the dump pile was placed. Based on APXS analyses comparing drill tailings to dump piles and ChemCam analyses inside the drill holes, there is no evidence for chemical variations that would preclude the use of multispectral data from drill tailings as a valid representation of the multispectral properties of the material actually measured by the CheMin instrument (Rampe et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020). Additionally, by using analyses of drill tailings for our comparisons with CheMin quantitative results, we can also make qualitative comparisons of unsuccessful drill targets with no dump piles to the quantitative comparisons that we found with the successful drill targets that were analyzed by CheMin.

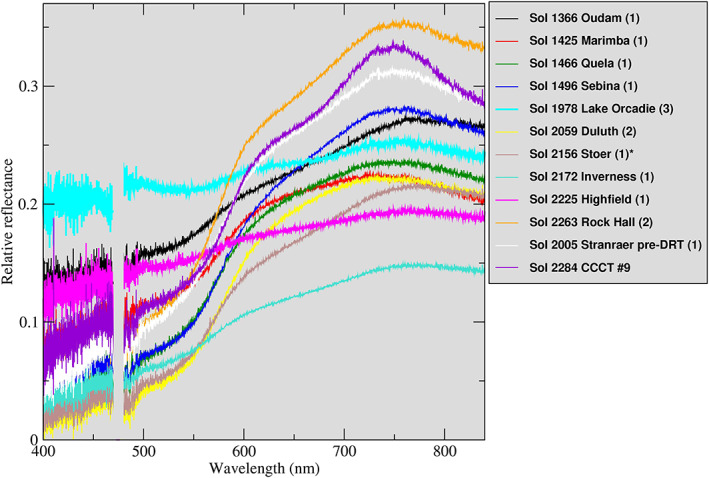

4.4. ChemCam Passive Reflectance Observations

After every ChemCam Laser Induced Breakdown Spectrometer (LIBS) measurement, a 3 ms exposure passive (“dark”) measurement was acquired without the laser for calibration purposes (Wiens et al., 2013, 2015). Johnson et al. (2015) demonstrated that these “dark” measurements could be used as passive reflectance spectra. Longer exposure measurements at 30 ms were acquired for specific targets of interest to increase the signal‐to‐noise ratio. The 0.74 mrad FOV of the spectra corresponds to a ~2 mm spot size at an observation distance of 3 m. Raw data were converted to radiance using the methods described by Johnson et al. (2015). Observations acquired at 3 and 30 ms exposures on Sol 76 of the ChemCam calibration target holder were used to minimize dark‐current variations between scene and calibration targets. The ratio of the scene and calibration target radiance measurements, multiplied by the known laboratory reflectance of the calibration target material (Wiens et al., 2012), provided an estimate of relative reflectance in the 400–840 nm range. Johnson et al. (2015) estimated that the radiance absolute calibration uncertainty was 6–8%. However, this calibration method was subject to much higher uncertainties during the 2018 dust storm when atmospheric opacity (τ) was greater than ~2. This was sufficiently different than the opacity during acquisition of the Sol 76 calibration target (τ = 0.76). Data acquired between Sols 2075 and 2155 were influenced by the contribution of atmospheric dust, rendering passive spectra of targets acquired during that period unusable via the current calibration method (Table S2).

ChemCam spectral parameters were calculated using ±5 nm averages around a central wavelength. In the near‐IR, the 750 to 840 nm slope is sensitive to the depth of iron absorptions. The 670/440 nm ratio is sensitive to oxidation state and/or dust deposition. The 535 nm band depth is sensitive to the presence of crystalline ferric oxides (e.g., Morris et al., 1997, 2000). See Table 1 for description of how each band parameter was calculated (cf. Bell et al., 2000).

4.5. Laboratory Methods

The goal of the lab work described below was to showcase how the wavelength position and/or depth of the near‐IR (~860–1,000 nm) absorption changed with variations in the abundances of ferric and ferrous minerals. For this purpose, powdered physical mixtures of the four major minerals plagioclase (albite), pyroxene (augite), phyllosilicate (nontronite), and hematite found in the drill targets discussed above (Achilles et al., 2020; Bristow et al., 2018; Rampe et al., 2020) were created in a lab at ASU (Table 2). The albite and pyroxene used were obtained from Minerals Unlimited. The albite is sourced from Canada, and the pyroxene (augite) is from the 1944 eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The nontronite sample used was the NG‐1 nontronite cemented sandstone obtained from the Clay Minerals Society Repository (Clark et al., 1990). Because this paper looks at relative variations in band depths any contamination in the end‐member samples, that is, quartz in the NG‐1 sample, does not affect the results and comparisons that are shown below. Spectra of all end‐member minerals were analyzed and determined to have the necessary absorption features for this study that were not affected by any potential contamination of the sample. Because much work has been done previously on the effects of hematite abundance on the 860 nm band depth, the mixtures for this new lab work either had no red crystalline hematite, or a constant 5 wt.% hematite, which is near the minimum amount necessary to produce the 860 nm absorption (Morris et al., 1989). Maintaining a constant hematite abundance across multiple mixtures helped to highlight the effects on spectral parameters produced by other ferric and ferrous minerals. For all of these mixtures, the four minerals used were ground and dry sieved to a grain size of 76–106 μm.

Table 2.

Abundances of the Minerals Used in Laboratory Mixtures and Corresponding Band Parameters

| Phyllosilicate (wt.%) | Pyroxene + plagioclase (wt.%) | Plagioclase (wt.%) | Pyroxene (wt.%) | Hematite (wt.%) | Band minimum (nm) | 867 nm band depth | 527 nm band depth | Similar Mars drill target | Hematite grain size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 77.5 | 22.5 | 0 | 1,019 | −0.036 | −0.039 | N/A | |

| 0 | 95 | 75 | 20 | 5 | 861 | 0.046 | 0.077 | 76–106 | |

| 8 | 87 | 71 | 16 | 5 | 863 | 0.068 | 0.105 | Oudam | 76–106 |

| 23 | 65 | 57 | 8 | 5 a | 897 | 0.0243 | 0.176 | <20 | |

| 877 | 0.0172 | 0.183 | 20–45 | ||||||

| 925 | 0.0046 | 0.106 | 45–90 | ||||||

| 933 | 0.0123 | 0.044 | 90–150 | ||||||

| 25 | 70 | 61 | 9 | 5 | 869 | 0.073 | 0.102 | Stoer | 76–106 |

| 25 | 75 | 66 | 9 | 0 | 985 | −0.017 | −0.035 | N/A | |

| 28 | 60 | 51 | 9 | 12 | 866 | 0.139 | 0.228 | Duluth | 76–106 |

| 56 | 39 | 31 | 8 | 5 | 876 | 0.101 | 0.142 | Sebina | 76–106 |

| 95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 882 | 0.166 | 0.223 | 76–106 | |

| 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 918 | 0.053 | −0.080 | N/A |

The abundance of each mineral in the laboratory mixtures was dictated by the desire to mimic the relative abundance of crystalline phyllosilicate, plagioclase, and pyroxene in drill samples on Mars as determined by CheMin. For example, mixtures were made to mimic the drill targets Oudam and Sebina because Oudam has the highest plagioclase + pyroxene abundance and the lowest phyllosilicate abundance, whereas Sebina has the lowest abundance of plagioclase + pyroxene. Although Stoer has the highest hematite abundance of the eight drill targets discussed, this abundance was purposefully not captured in the lab mixtures. Other mixtures were made to understand the spectral changes caused by a small percentage (5 wt.%) of hematite mixed with nearly end‐member mixtures, such as the mixture with 95 wt.% nontronite and 5 wt.% hematite. These mixtures do not represent any particular drill target on Mars. Additionally, a mixture with 12 wt.% red crystalline hematite was made to represent the relative abundances of all four minerals, including hematite, of the Duluth drill target on Mars.

Lastly, in order to understand spectral variations caused by changes in hematite grain size, a mixture was made using the natural sulfatetic tephra sample HWMK20 from the Mauna Kea Volcano in Hawaii (Table 2). Mössbauer patterns indicate that the HWMK20 sample consists of 42 wt.% red crystalline hematite and 58 wt.% tetrahedrally coordinated Fe3+, likely iron‐bearing glass (Fleischer et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2000). We made a mixture with this particular sample because it is an analog for hematite‐bearing surfaces on Mars and its spectral signature is well documented. Unfortunately, there was not enough of this sample to use for all mixtures in this study. The mixture created for this project used 12 wt.% HWMK20, which resulted in ~5 wt.% hematite and ~7 wt.% iron‐bearing glass in the analyzed mixture due to the mixed composition of HWMK20.

For all lab mixtures in this study bidirectional reflectance spectra from 350–2,500 nm were acquired using an Analytical Spectral Devices (ASD) Field‐Spec Pro HR® spectrophotometer at 3 nm spectral sampling. Spectra were acquired at an incidence angle of 0° and an emission angle of 30°. The resulting laboratory spectra were convolved to Mastcam wavelengths and spectral resolution. Band depths of the laboratory spectra (Table 2) were calculated using the same methods as for the Mastcam flight imaging data (Table 1) to allow for direct comparison to Mastcam multispectral observations.

4.6. Calculating Strength From Drill Percussion Energy

The original drilling algorithm (known as “standard”) started the drilling operation at Percussion Level 4, adjusting percussion energies up or down based on performance. The standard percussion algorithm was used during the first four drilling campaigns at outcrops John Klein on Sol 182, Cumberland on Sol 279, Windjana on Sol 621, and Confidence Hills on Sol 759. However, after twice fracturing the slabs of drill targets before they could be sampled, another percussion algorithm was developed. This second percussion algorithm, “reduced percussion”, starts the drilling operation at Percussion Level 1 and then adds more percussion energy based on the rate of penetration (ROP). Because the drill does not deliver extra percussive energy in the process of drilling the rock and works to maintain a prescribed ROP, drill performance during reduced percussion was used to approximate the strengths of some rocks drilled at Gale crater (Peters et al., 2018).

A third drilling algorithm called “rotary only” was developed as rover data suggested that percussion was exacerbating a periodic electrical short identified in the voice coil mechanism (Lakdawalla, 2018). However, after a rotary‐only attempt failed to penetrate the outcrop at drill target Lake Orcadie on Sol 1973, MSL engineers developed the FEDuP algorithm. The FEDuP algorithm starts the drilling operation without percussion (rotary only), but much like the reduced percussion algorithm, FEDuP allows the system to add or subtract percussion levels, based on drilling performance. Even though FEDuP resembles reduced percussion, when using FEDuP, the drill is less stabilized, the drilling preloads are different, and significant portions of the rock can be drilled without percussion. As a result, the rock strengths of FEDuP drilled rocks cannot yet be directly compared to those that were drilled using reduced percussion. Quantitative strengths cannot be reported for FEDuP drilled rocks without further study. However, relative trends in rock strengths can be assessed, using drill telemetry data, for rocks drilled using the FEDuP algorithm by evaluating what percussion level and how much time was necessary to reach the full drill depth.

5. Results

Our results focus on the spectral data from the Mastcam multispectral and ChemCam passive observations and how they correlate to the mineralogic differences between drill targets. Drill targets discussed here include Oudam, Marimba, Quela, Sebina, and Duluth, which are all targets from Murray formation units below VRR (Figures 1 and 2). The three drill targets analyzed on VRR are Highfield, Stoer, and Rock Hall. The drill targets are discussed below in chronological and inferred relative stratigraphic order, from oldest (lowest stratigraphic level) to youngest (highest stratigraphic level). Additional details regarding the APXS, ChemCam LIBS, and CheMin results can be found in (Achilles et al., 2020; Bristow et al., 2018; Frydenvang et al., 2020; Rampe et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020).

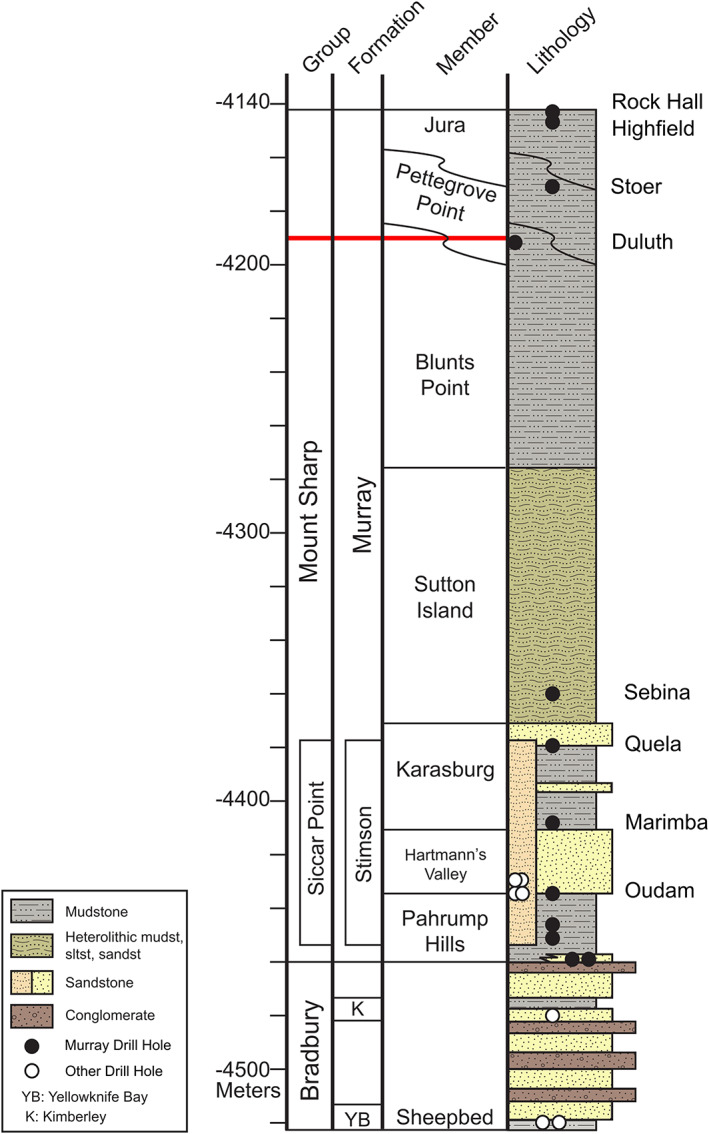

Figure 5 shows the inferred relative stratigraphic positions of the drill targets discussed here. Based on the composition of these eight successful drill targets, they can be divided into two mineralogical categories: (1) Oudam, Duluth, Stoer, Highfield, and Rock Hall are all targets with high plagioclase + pyroxene and lower abundances of phyllosilicates, and (2) Marimba, Quela, and Sebina are all targets with low plagioclase + pyroxene and higher abundances of phyllosilicates. Hematite abundance also varies among the samples, but hematite does not vary consistently with other minerals (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Inferred Gale crater relative stratigraphic column (Siebach et al., 2019) showing the location of the drill targets discussed here. Red line shows the approximate location of VRR in the stratigraphic sequence of the Murray formation.

Table 3.

Rock Strength and CheMin Abundances of the Bulk Sample for Successful Drill Targets

| Drill target | Rock strength (MPa) | Plagioclase (wt.%) | Pyroxene (wt.%) | Hematite (wt.%) | Ca‐sulfate (wt.%) | Phyllosilicate (wt.%) | Amorphous (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oudam a , b | 12–18 | 27.8 (0.5) | 5.3 (0.9) | 13.9 (0.4) | 6.4 (0.3) | 3 (1) | 43 (20) |

| Marimba a , b | >18 | 14.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.6) | 6.7 (0.4) | 7.4 (0.6) | 28 (5) | 40 (20) |

| Quela a , b | 8.5–12 | 13.9 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.7) | 7.3 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.4) | 16 (3) | 52 (25) |

| Sebina a , b | >18 | 10.7 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.4) | 6.9 (0.6) | 7.4 (0.6) | 19 (4) | 51 (25) |

| Duluth c | 27.1 (0.6) | 4.5 (1.1) | 6.1 (1.0) | 5.3 (0.5) | 15 (4) | 37 | |

| Stoer c | 23.2 (1.0) | 3.3 (0.9) | 14.7 (0.8) | 6.0 (0.9) | 10 (3) | 38 | |

| Highfield c | 19.9 (0.9) | 4.2 (1.5) | 8.5 (0.5) | 6.8 (0.8) | 5 (1) | 49 | |

| Rock Hall c | 20.2 (2.2) | 9.1 (1.0) | 2.9 (0.2) | 11.2 (1.4) | 13 (3) | 34 (8) |

Note. Numbers in parentheses are associated errors. Quantitative rock strengths for Duluth and the VRR drill targets have not yet been calculated. Amorphous abundances reported for Duluth, Stoer, and Highfield represent the minimum based on mass balance calculations and, therefore, do not have errors associated with them. See Rampe et al. (2020) for more details.

Peters et al. (2018).

Bristow et al. (2018).

Rampe et al. (2020).

5.1. Successful Drill Targets

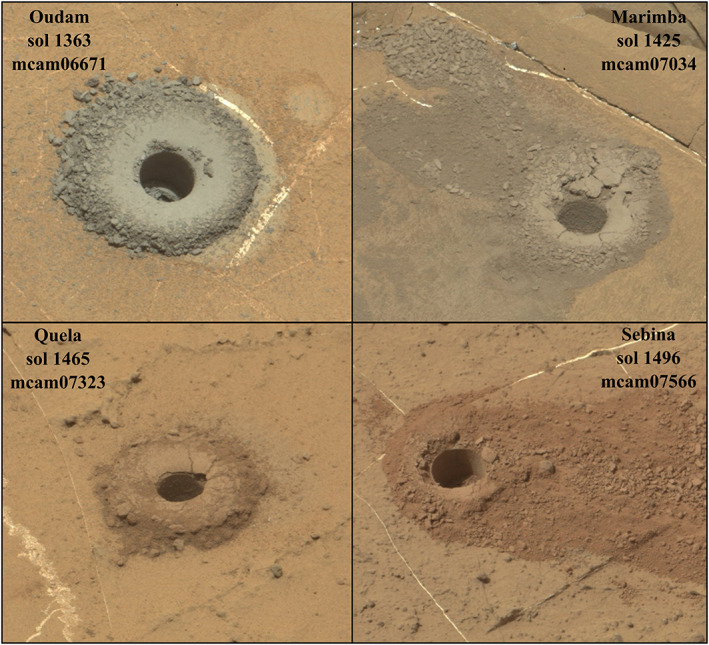

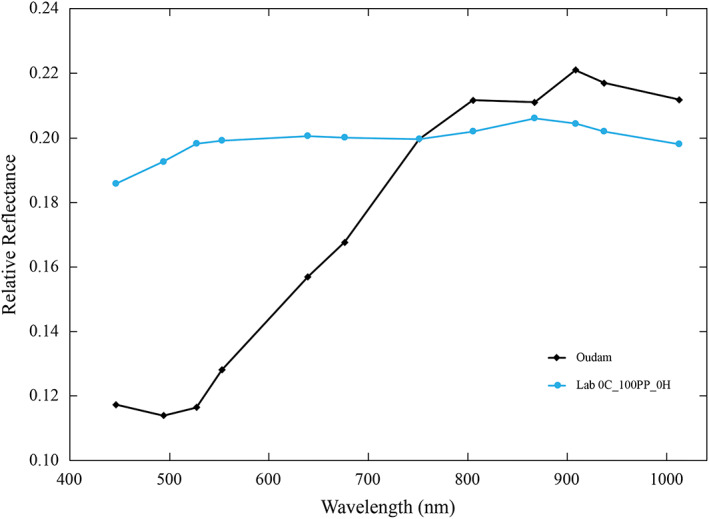

5.1.1. Oudam

The target Oudam was drilled on Sol 1361 and is located in the Hartmann's Valley member of the Murray formation (Figure 6, top left). Of the eight drill targets compared here, Oudam has the lowest abundance of phyllosilicates (3 wt.%) and the second highest abundance of crystalline hematite (13.9 wt.%) as measured in the bulk fraction by CheMin (Bristow et al., 2018). Oudam has a moderate rock strength of 12–18 MPa (Table 3). In the Mastcam multispectral data, the Oudam drill tailings have the weakest 867 nm band depth (Table 4 and Figure 7). The Oudam drill tailings have the highest abundance of SiO2 (52.87 wt.%) as measured by APXS; this abundance is higher than average Murray SiO2 abundance (Thompson et al., 2020). ChemCam passive spectra exhibit among the lowest 535 nm band depths and 670/400 nm ratios and the lowest 750–840 nm slopes (Figure 8 and Table 5).

Figure 6.

Mastcam right eye visible wavelength RGB approximate true color images of the Murray drill tailings below VRR. Top row, left: Oudam (Sol 1363; mcam06671); right: Marimba (Sol 1425; mcam07034). Bottom row, left: Quela (Sol 1465; mcam07323); right: Sebina (Sol 1496; mcam07566). For scale, the drill hole is 1.6 cm in diameter.

Table 4.

Band Parameters for Mastcam Spectra of the Drill Tailings for the Successful and Unsuccessful (Shaded Cells) Drill Targets Studied Here

| Drill target | 867 nm band depth | 527 nm band depth | 676/446 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oudam | −0.029 (0.009) | 0.138 (0.007) | 1.43 (0.022) |

| Marimba | 0.058 (0.008) | 0.160 (0.007) | 1.75 (0.029) |

| Quela | 0.023 (0.008) | 0.255 (0.007) | 4.30 (0.072) |

| Sebina | 0.055 (0.008) | 0.363 (0.006) | 4.78 (0.081) |

| Lake Oracdie | 0.005 (0.008) | 0.184 (0.007) | 0.86 (0.014) |

| Lake Oracdie 2 | 0.027 (0.008) | 0.177 (0.007) | 1.06 (0.017) |

| Duluth | 0.038 (0.008) | 0.472 (0.005) | 7.81 (0.111) |

| Voyageurs | 0.138 (0.007) | 0.415 (0.005) | 3.91 (0.061) |

| Ailsa_Craig | 0.076 (0.008) | 0.408 (0.006) | 4.87 (0.073) |

| Stoer Tailings | 0.017 (0.009) | 0.205 (0.006) | 2.71 (0.045) |

| Stoer Dump Pile | 0.020 (0.008) | 0.247 (0.007) | 2.71 (0.047) |

| Inverness | 0.028 (0.008) | 0.132 (0.007) | 1.06 (0.018) |

| Highfield | −0.008 (0.007) | 0.101 (0.008) | 1.18 (0.019) |

| Rock Hall | 0.098 (0.008) | 0.344 (0.006) | 4.50 (0.072) |

Note. Numbers in parentheses are the error associated with the band parameter.

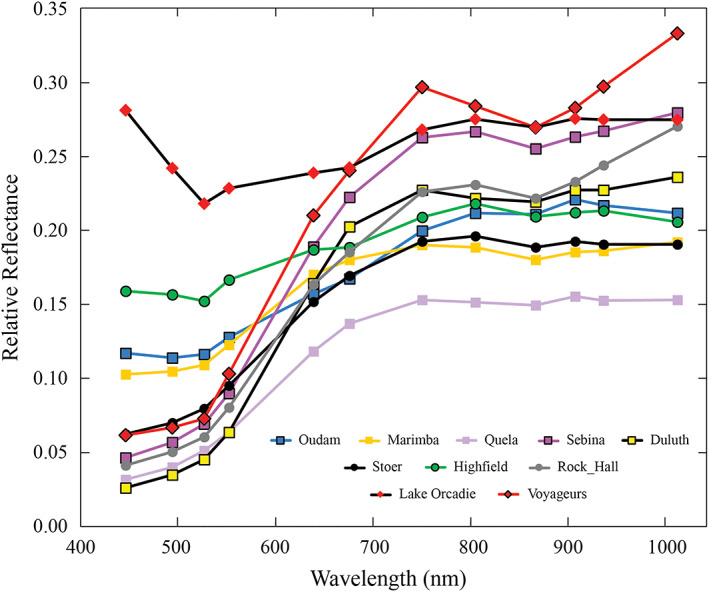

Figure 7.

Mastcam spectra from eight successful drill targets and two unsuccessful drill targets discussed in this work. Square markers are for the drill targets below VRR, circles are for drill targets on VRR, and diamonds are for the unsuccessful drill targets on VRR. The average error is 0.008, which is about the size of the markers.

Figure 8.

ChemCam passive spectra of the drill targets discussed here. Numbers in parentheses correspond to location within ChemCam raster for a given target. The Sol 2156 Stoer measurement was acquired under atmospheric opacity conditions of τ = 1.8 and may be influenced by residual atmospheric dust (see text). CCCT #9 is the ChemCam onboard calibration target that contains 9 wt.% hematite (Vaniman et al., 2012).

Table 5.

Average Spectral Parameters Calculated From Five‐Location ChemCam Rasters of the Drill Tailings for the Successful and Unsuccessful (Shaded Cells) Drill Targets Studied Here

| Drill target [sol] | 750–840 nm slope | 535 nm band depth | 670/440 nm ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oudam drill tailings (loose) [1364] | 0.46e − 04 (6.63e − 06) | 0.061 (0.001) | 1.98 (0.04) |

| Oudam drill tailings (packed) [1366] | −0.14e − 04 (5.54e − 06) | 0.050 (0.001) | 1.72 (0.01) |

| Oudam dump pile presieve [1368] | −0.31e − 04 (6.62e − 06) | 0.048 (0.001) | 1.66 (0.01) |

| Marimba drill tailings (loose) [1425] | −2.32e − 04 (4.88e − 06) | 0.101 (0.001) | 2.36 (0.02) |

| Marimba drill tailings (packed 3–5) [1425] | −2.64e − 04 (3.78e − 05) | 0.094 (0.003) | 2.19 (0.09) |

| Marimba dump pile presieve [1427] | −2.15e − 04 (5.21e − 06) | 0.095 (0.002) | 2.20 (0.01) |

| Quela drill tailings [1466] | −1.73e − 04 (7.41e − 06) | 0.162 (0.002) | 4.28 (0.07) |

| Quela dump pile presieve [1467] | −1.78e − 04 (5.27e − 06) | 0.140 (0.002) | 3.69 (0.08) |

| Sebina drill tailings [1496] | −2.13e − 04 (9.90e − 06) | 0.194 (0.007) | 4.12 (0.23) |

| Lake Orcadie drill tailings [1978] | −1.39e − 04 (5.64e − 06) | 0.042 (0.002) | 1.16 (0.01) |

| Stranraer predust removal tool [2005] | −2.97e − 04 (1.65e − 05) | 0.156 (0.020) | 3.85 (0.34) |

| Duluth drill tailings [2059] | −1.45e − 04 (1.85e − 05) | 0.279 (0.011) | 7.15 (0.38) |

| Stoer dump pile [2156] | −0.51e − 04 (3.09e − 06) | 0.200 (0.002) | 5.38 (0.06) |

| Inverness drill tailings [2172] | −0.37e − 04 (5.93e − 07) | 0.074 (0.002) | 2.84 (0.05) |

| Highfield drill tailings [2225] | −0.54e − 04 (6.09e − 06) | 0.027 (0.001) | 1.39 (0.04) |

| Rock Hall tailings [2263] | −2.13e − 04 (8.30e − 06) | 0.165 (0.001) | 4.11 (0.05) |

Note. Numbers in parentheses are the standard deviation of the average spectral parameter.

5.1.2. Marimba

Marimba was drilled on Sol 1420 and is located in the Karasburg member of the Murray formation (Figure 6, top right). Marimba has abundant Ca‐sulfate (7.4 wt.%) and the highest abundance of phyllosilicates (28 wt.%) of the samples discussed here as assessed by CheMin (Bristow et al., 2018). The phyllosilicates are likely Al‐rich, ferric dioctahedral smectites (Bristow et al., 2018). Marimba also has one of the lowest abundances of crystalline hematite (6.7 wt.%) among the drill samples studied in this area (Bristow et al., 2018). Marimba has the second strongest 867 nm band depth of the successful drill targets (Table 4) and is inferred to be the strongest successfully drilled target (>18 MPa; Table 3) among the drill samples studied here. ChemCam passive spectra of Marimba exhibit relatively low 535 nm band depths (~0.1) and 670/400 nm ratios (~2.2) and intermediate 750–840 nm slopes (−2.3 × 10−4).

5.1.3. Quela

The full drill of the target Quela was completed on Sol 1464. This target is located in the Karasburg member of the Murray formation (Figure 6, bottom left). CheMin mineralogy shows that Quela has the second lowest abundance of plagioclase (13.9 wt.%) and pyroxene (2.8 wt.%) but one of the highest estimated abundances of amorphous material (52 wt.%; Bristow et al., 2018). Quela has a weak 867 nm band depth (Table 4) and is inferred to have been a fairly weak rock to drill (8.5–12 MPa; Table 3). The Quela drill tailings have the lowest abundance of SiO2 (44.81 wt.%) as measured by APXS (Thompson et al., 2020). Quela's passive ChemCam spectra 750–840 nm slope values of −1.7 × 10−4 were slightly weaker compared to Marimba, but Quela was slightly redder (670/440 nm ratios ~4), with stronger 535 nm band depths (~0.15).

5.1.4. Sebina

The Sebina target was drilled on Sol 1495 and is located in the Sutton Island member of the Murray formation (Figure 6, bottom right). Sebina has the lowest abundance of plagioclase (10.7 wt.%) and the second highest abundance of amorphous material (51 wt.%) as determined from CheMin measurements (Bristow et al., 2018). Sebina has the second strongest 867 nm band depth (Table 4) and was the second hardest successful drill target (>18 MPa; Table 3) among the drill samples studied in this area. The Sebina drill tailings have the highest SiO2 abundance (46.17 wt.%) for drill targets within the typical Murray SiO2 range (Thompson et al., 2020). Sebina exhibited even stronger 535 nm band depths (~0.2) than Quela but similar 670/440 nm ratios (~4.1) and 750–840 nm slopes (−2.1 × 10−4) in ChemCam passive spectra.

5.1.5. Duluth

The Duluth drill target (Figure 9, top left) was completed on Sol 2057 and was the first full‐depth drill hole to be produced with the FEDuP protocol. Duluth is part of the Blunts Point member of the Murray formation, just below VRR. CheMin results show that Duluth has the lowest abundance of Ca‐sulfate (5.3 wt.%) and the second lowest abundance of hematite (6.1 wt.%; Rampe et al., 2020). The Duluth drill tailings have an average 867 nm band depth (Table 4), and it is most likely the weakest drill target of the Upper Murray and VRR drill targets. The drill progressed to 33 mm depth using rotary only and then increased to Percussion Level 2 for the duration of the drilling process, behavior that is consistent with Duluth being weaker than all other rocks within this study area, including those drilled using the reduced percussion algorithm. ChemCam passive spectra of Duluth exhibited the strongest 535 nm band depths (~0.28) and 670/400 nm ratios (~7.1) of all drill tailings but lower 750–840 nm slope values (−1.5 × 10−4) than Quela and Sebina. CheMin results show that Duluth has the second lowest abundance of amorphous material in the drill tailings (37 wt.%; Rampe et al., 2020). This is consistent with a potential correlation between amorphous components and spectral contrast in ChemCam reflectance spectra (cf. Johnson et al., 2019).

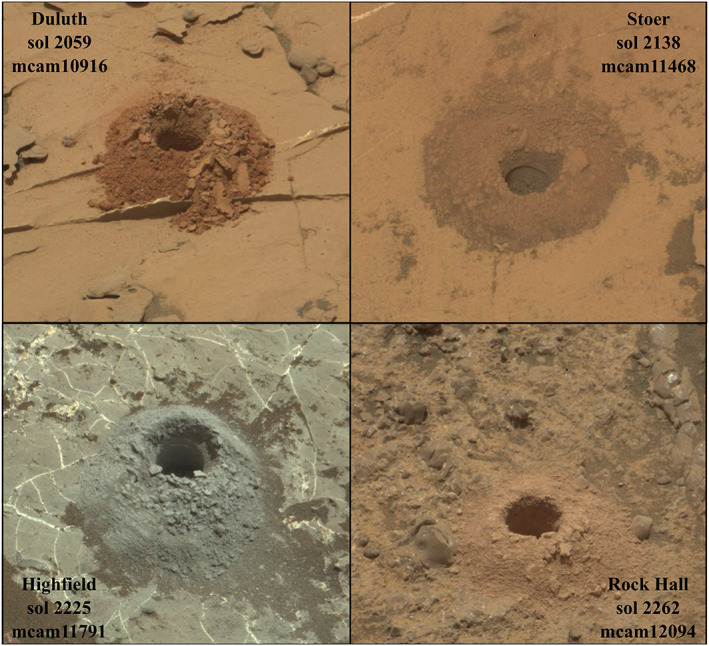

Figure 9.

Mastcam right eye visible wavelength RGB approximate true color images of VRR and Blunts Point drill tailings. Top row, left: Duluth (Sol 2059; mcam10916); right: Stoer (Sol 2138; mcam11468). Bottom row, left: Highfield (Sol 2225; mcam11791); right: Rock Hall (Sol 2262; mcam12094). For scale, the drill hole is 1.6 cm in diameter.

5.1.6. Stoer

Stoer, drilled on Sol 2136, was the first successful drill target on VRR and is the only successful drill target located in the Pettegrove Point member (Figure 9, top right). CheMin results show that Stoer has the highest abundance of hematite (14.7 wt.%) measured during the MSL mission thus far (Rampe et al., 2020). However, Stoer has an extremely weak 867 nm band depth (Table 4) compared to other rocks drilled in this area. Drilling of Stoer progressed to 25 mm without percussion, then the penetration progress stalled while the system rapidly increased percussive energy to reach Percussion Level 5. The telemetry from the first half of the Stoer borehole drilling process is consistent with the rock being as weak as Duluth. However, the telemetry from the second half of the drilling operation is consistent with a much stronger layer present at depth.

The sample portion CheMin analyzed was likely from a depth right after the drill telemetry suggested a change in rock strength. Therefore, the CheMin sample might have included material from the harder portion of the Stoer drill target. The Stoer dump pile did provide clean multispectral data, and comparing the spectral parameters of the dump pile to the drill tailings did not show significant differences in the band depths (Table 4). ChemCam passive spectra were acquired during the final phase of the 2018 global‐scale dust storm, and only data on the dump pile were acquired under suitable atmospheric conditions conducive to accurate calibration. At that time, atmospheric opacity values were still somewhat high (τ ~ 1.8), but the spectra appeared less affected than earlier spectra of the Stoer drill tailings. Nonetheless, Stoer exhibited high 535 nm band depths (0.2) and 670/440 nm ratios (5.4) and relatively low 750–840 nm slopes (similar to Oudam and Highfield). Stoer's relatively low amorphous content (38 wt.%) might explain some of its spectral characteristics, although residual atmospheric influence may play a role as well.

5.1.7. Highfield

Highfield was drilled on Sol 2224 and is located in the Jura member of VRR (Figure 9, bottom left). Highfield is the only gray‐colored rock successfully drilled on VRR and has the second lowest abundance of phyllosilicates (5 wt.%; Rampe et al., 2020). Highfield does not have an 867 nm absorption feature (Table 4) and is interpreted based on drill telemetry to be the strongest VRR drill target. During drilling the drill alternated between Percussion Levels 3 and 4 with no significant portion of the outcrop being drilled using rotary only. Highfield is stronger than Duluth, Rock Hall, and the upper part of Stoer but likely weaker than the lower part of Stoer. The Highfield drill tailings also have higher than average Murray SiO2 abundance as measured by APXS (52.38 wt.%; Thompson et al., 2020) and detectable opal‐CT in CheMin analyses (Rampe et al., 2020). The gray nature of the Highfield drill tailings was manifested in passive ChemCam spectra by a relatively flat spectral response and among the lowest 535 nm band depths (~0.03), 670/400 nm ratios (~1.4), and 750–840 nm slopes (−0.5 × 10−4). The relatively large amount of crystalline hematite detected by CheMin (Rampe et al., 2020) is considered to be gray (coarser‐grained) hematite, consistent with the lack of spectral contrast in the drill tailings samples.

5.1.8. Rock Hall

Rock Hall was drilled on Sol 2261 and is located in the Jura member of VRR (Figure 9, bottom right). Rock Hall is unusual compared to the other drill targets studied here because it does not have the same average Murray composition as the rest. For instance, APXS results show that Rock Hall has the lowest SiO2 abundance (35.43 wt.%) and significantly higher CaO (9.16 wt.%) and SO3 (14.96 wt.%) abundance compared to other successful drill targets (Thompson et al., 2020). However, ChemCam's 47 LIBS observations of the Rock Hall surface and inside the drill hole yield a mean SiO2 abundance of 47.6 wt.% and a correspondingly lower CaO abundance compared to APXS (discussed in section 5.4). CheMin analysis revealed 1.3 wt.% fluorapatite (Ca5(PO4)3F) in Rock Hall (but not in the other nearby samples), and Rock Hall has a significantly larger quantity of akaganeite (a chloride‐containing ferric oxyhydroxide; 6.0 wt.%) than any other targets studied in this region. Additionally, Rock Hall has the highest relative abundances of pyroxene (9.1 wt.%) and Ca‐sulfate 11.2 (wt.%) and the lowest relative abundance of hematite (2.9 wt.%) of any of the samples studied in this area (Rampe et al., 2020). Rock Hall has a strong 867 nm band depth (Table 4) and is interpreted to be a weak rock based on drilling telemetry. The drill was able to progress to 17 mm in rotary‐only mode, and then the system alternated between Percussion Levels 2 and 3 to maintain the prescribed ROP. Drill telemetry suggests that Rock Hall is stronger than Duluth and the upper part of Stoer but weaker than Highfield and the lower part of Stoer. Rock Hall's passive spectra from ChemCam exhibited the highest relative reflectance of all samples at wavelengths beyond 600 nm but exhibited intermediate 535 nm band depths (0.17), 670/440 nm ratios (~4), and 750–840 nm slopes (−2.1 × 10−4). These parameters could be consistent with the sample's low hematite abundance and/or low amorphous component (~34 wt.%).

5.2. Unsuccessful Drill Targets

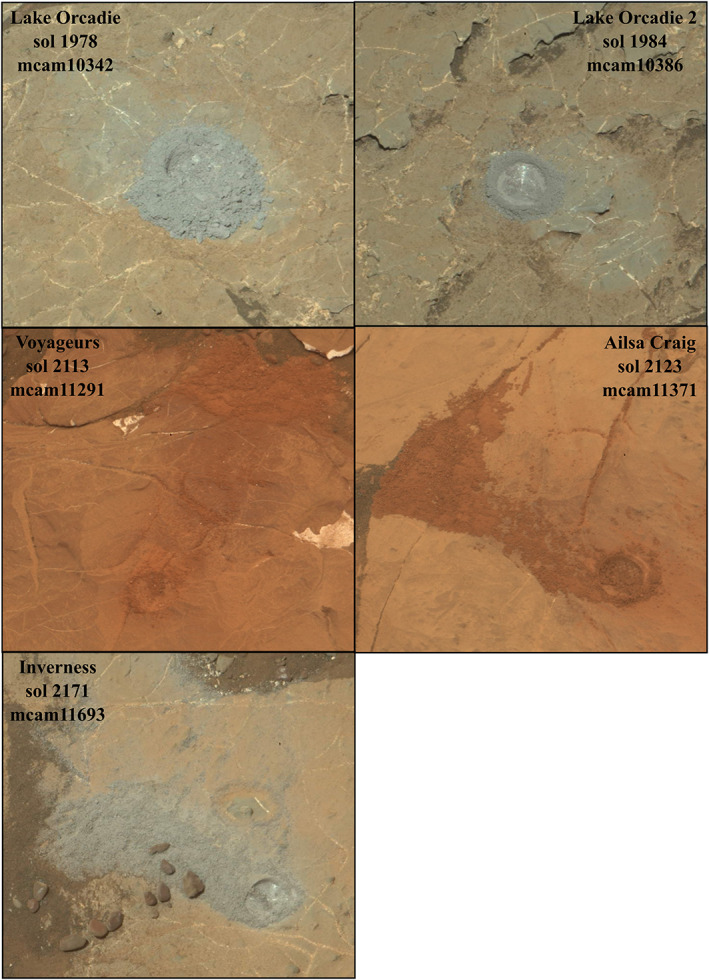

5.2.1. Lake Orcadie and Lake Orcadie 2

Lake Orcadie (Figure 10, top left) was the first drill attempt made after the drilling hiatus on Sol 1976. The Lake Orcadie 2 (Figure 10, top right) drill attempt was on Sol 1983 and was ~10 cm from the Lake Orcadie drill location. Both Lake Orcadie targets are located in the Jura member of VRR. For these targets, engineers used a rotary‐only feed extended method, meaning no percussive motion was used to attempt to reach full drill depth. While the drill attempts did not produce enough drill tailings at either location for CheMin analyses, the tailings resulting from the aborted drill attempt were still of sufficient areal extent to acquire APXS measurements, Mastcam multispectral, and ChemCam passive observations. Results from APXS showed that both Lake Orcadie targets have a similar average Murray composition as the successful drill targets described above. Multispectral data show that the first Lake Orcadie target has a very weak 867 nm band depth, while Lake Orcadie 2 has a slightly stronger 867 nm band depth (Table 4). The ChemCam spectra were unique in that they exhibited an absorption centered near 550 nm in an otherwise relatively flat spectral response. The 535 nm band depths (~0.04) and 750/840 nm slopes (−1.4 × 10−4) were relatively low, and the 670/400 nm ratios (~1.2) were the lowest of all drill tailings studied in this area.

Figure 10.

Mastcam right eye visible wavelength RGB approximate true color images of the unsuccessful VRR drill targets. Top row, left: Lake Orcadie (Sol 1978; mcam10342); right: Lake Orcadie 2 (Sol 1984; mcam10386). Middle row, left: Voyageurs (Sol 2113; mcam11291); right: Ailsa Craig (Sol 2123; mcam11371). Bottom row: Inverness (Sol 2171; mcam11693). For scale, the drill hole is 1.6 cm in diameter.

5.2.2. Voyageurs

The Voyageurs drill target (Figure 10, middle left) was attempted on Sol 2112 using percussive drilling. Voyageurs is located in the Pettegrove Point member and was chosen because of its deep red color compared to other nearby bedrock outcrops. Due to the strength of the target, the drill only achieved a few millimeters before the drilling sequence terminated. Although unsuccessful, the drill attempt did produce a small amount of drill tailings from which we acquired Mastcam multispectral data. Mastcam results show that Voyageurs has the strongest 867 nm band depth (Table 4) of all targets discussed in this paper. APXS analyses of the drill tailings show that Voyageurs has average Murray composition.

5.2.3. Ailsa Craig

The Curiosity rover team attempted to drill the Ailsa Craig target (Figure 10, middle right) on Sol 2122 as another attempt to sample red material in the Pettegrove Point member. However, the rock was also too strong to achieve full drill depth. Mastcam results show that Ailsa Craig drill tailings have a strong 867 nm band depth (Table 4) as is typical of most red rocks on VRR.

5.2.4. Inverness

The Inverness target (Figure 10, bottom image) was attempted on Sol 2170. Inverness is a gray rock located in the Jura member of VRR. Previous unsuccessful drill attempts using percussive drilling were on the red rocks of VRR, and it was thought that the gray rocks might be softer. However, Inverness was also too strong to achieve full drill depth. Multispectral data show that Inverness has the strongest 867 nm band depth (Table 4) for the gray rocks of VRR. The ChemCam passive spectra of the Inverness aborted drill target's tailings exhibited the lowest relative reflectance of all tailings at wavelengths longer than 600 nm, with relatively low 535 nm band depths (~0.07), 670/440 nm ratios (~2.8), and 750–840 nm slopes (−0.4 × 10−4).

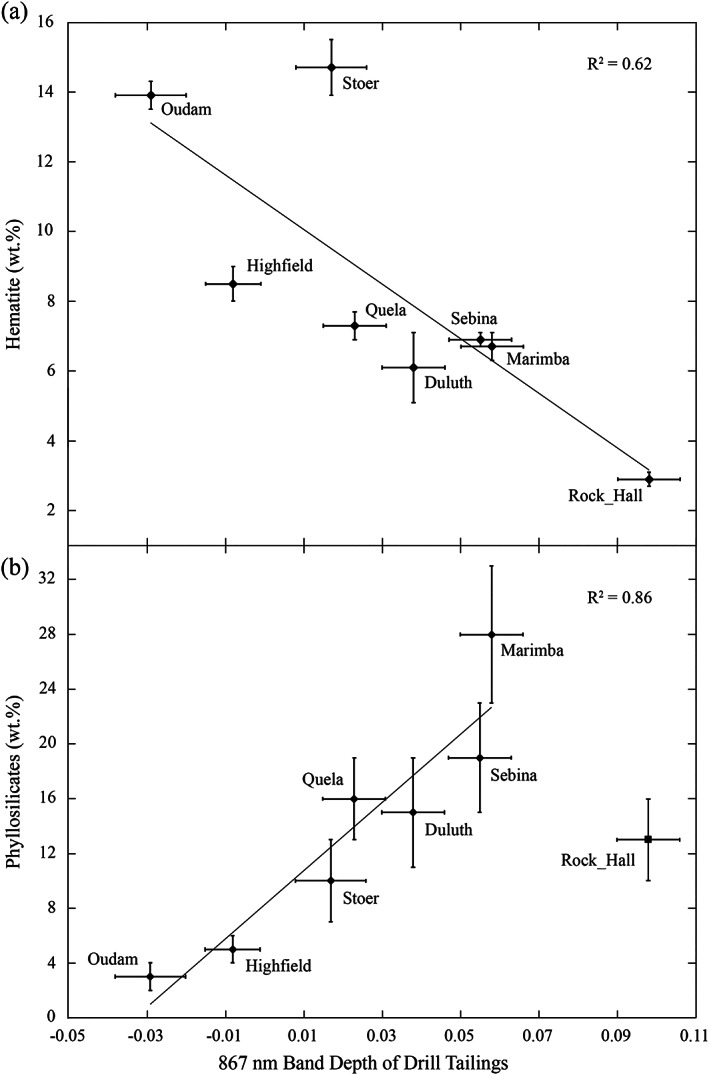

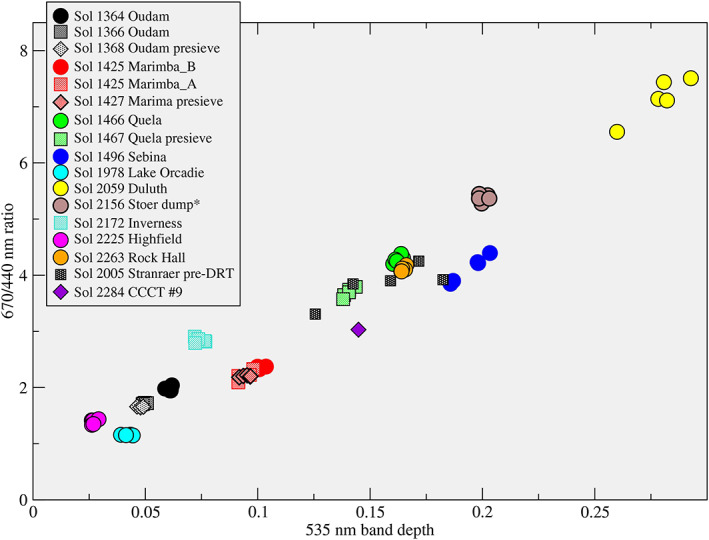

5.3. Correlations Between Spectral and Mineralogical Properties

For the comparisons of Mastcam multispectral, ChemCam passive, and CheMin results presented below, the reflectance data come from the drill tailings observations. Hematite has previously been invoked to explain the strong 860 nm signal from orbital data of VRR (Fraeman et al., 2013; Milliken et al., 2010). Surface analyses of drilled samples, however, show a moderate (R 2 = 0.4–0.7) negative correlation between the abundance of crystalline hematite and the depth of the 867 nm absorption feature in the drill tailings studied here (Figure 11a). In contrast, CheMin and Mastcam data show a strong positive correlation between the abundance of phyllosilicates and the depth of the 867 nm absorption feature in the drill tailings (Figure 11b). CheMin and SAM evolved gas analyses suggest that these phyllosilicates represent a mix of trioctahedral Mg‐smectite and dioctahedral ferric‐Al‐bearing smectite in Marimba, Quela, and Sebina, nontronite in Duluth, and a fully collapsed smectite or ferripyrophyllite in Oudam, Stoer, Highfield, and Rock Hall (Bristow et al., 2018; McAdam et al., 2020; Rampe et al., 2020).

Figure 11.

CheMin XRD‐based mineral abundance (y axis) and Mastcam 867 nm multispectral band depth parameter (x axis) comparisons for the successfully drilled targets in our study area, showing (a) a moderate negative correlation between the abundance of crystalline hematite and 867 nm band depth and (b) a strong positive correlation between the abundance of crystalline phyllosilicates and 867 nm band depth (excluding Rock Hall).

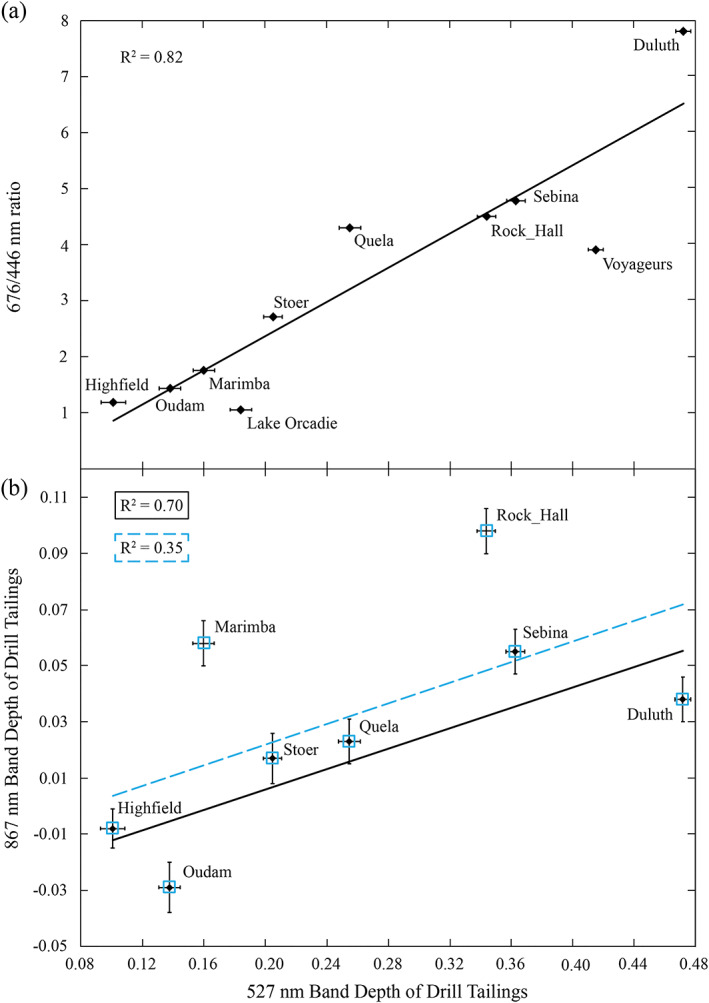

Other spectral trends that highlight variations in the physical and/or mineralogic properties of the rocks are the 535 nm band depth and the red/blue ratio. The presence of either or both of these spectral parameters can indicate the presence of hematite, while the increase in 535 nm band depth and red/blue ratio can sometimes indicate smaller hematite grain sizes (Johnson et al., 2019; Morris et al., 1985). Additionally, an increase in the red/blue ratio typically indicates a redder visible color of the rock (Horgan et al., 2020). Comparisons from both ChemCam passive and Mastcam multispectral data show a strong (R 2 > 0.7) positive correlation between the 535 nm band depth and the red/blue ratio (Figures 12 and 13a). Comparing the band depth of the 867 and 527 nm Mastcam absorption features produces only a weak positive correlation (Figure 13b), with two potential outlier drill targets: Marimba and Rock Hall. One possible reason that Marimba and Rock Hall have stronger 867 nm band depths is that Marimba has the highest abundance of phyllosilicates and Rock Hall has a significant abundance of akaganeite and jarosite. Without these two targets, the above correlation becomes significantly stronger.

Figure 12.

ChemCam passive spectral parameters comparing the red/blue ratio and 535 nm band depth of drill targets studied in this region. The low values of both parameters for gray rocks such as Lake Orcadie and Highfield could be consistent with coarser‐grained hematite relative to finer‐grained hematite for targets such as Duluth (cf. Johnson et al., 2019).

Figure 13.

(a) Comparison of the Mastcam‐derived red/blue ratio to the 527 nm band depth, showing a correlation similar to that seen in ChemCam data (Figure 12). Y axis error bars are smaller than the height of the symbols. (b) Comparison of the Mastcam‐derived 867 and 527 nm band depths of the eight successful drill targets. The dashed blue line shows the best fit correlation with all eight targets (blue square outlines). The solid black line shows the best fit correlation without the possible outlier targets Marimba and Rock Hall.

The weak trend between the 867 and 527 nm band depths could indicate a minimal effect of hematite grain‐size variations on the absorption features observed in the spectra of the Oudam, Quela, Sebina, Duluth, Highfield, and Stoer drill targets. If the depth of the 527 nm band depth is used as a proxy for relative grain‐size variations (Johnson et al., 2017), ChemCam passive and Mastcam multispectral data suggest that Duluth has the smallest grain size, while Highfield and Oudam have the largest grain sizes of the targets discussed here. This is in agreement with measurements of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of hematite XRD peaks by the CheMin team (Rampe et al., 2020), and overall spectral trends on VRR indicating hematite grain‐size coarsening upward toward the Jura (Horgan et al., 2020). A second explanation for the apparent lack of correlation among all eight drill targets is the effect of small number statistics; given that Figure 13b only contains data from drill targets, the overall positive correlation that Fraeman, Edgar, et al. (2020) show between the 750/840 slope (ChemCam proxy for 867 nm band depth) and BD535 as measured by ChemCam may not be evident. Both of these explanations likely affect the trend seen in Figure 13b.

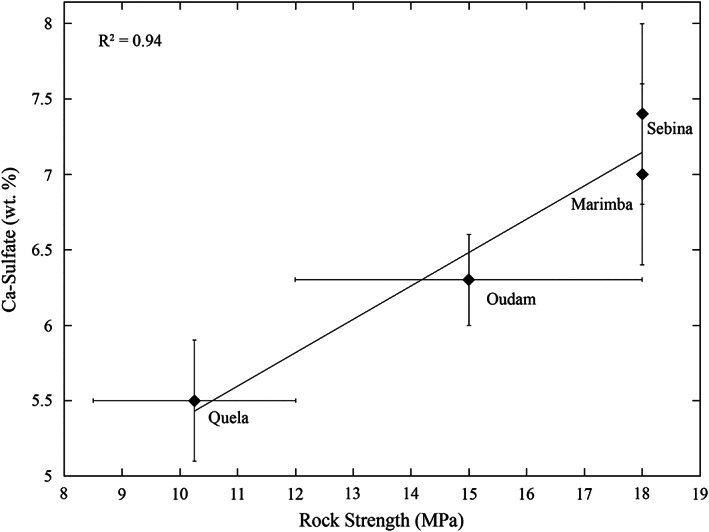

5.4. Correlations Between Rock Strength and Mineralogical Properties

The eight successful drill holes discussed above span a significant range of rock strengths as determined by drill telemetry. In addition to those, there were multiple rocks encountered during the VRR science campaign that were too strong for the rover's drill to achieve full drill depth (~40 mm). As shown above, all of the drilled or attempted rocks have varied spectral and morphologic properties, so it is difficult to determine the precise contributing factor(s) responsible for the variation in strengths of all the rocks. We did, however, find a strong correlation between the abundance of Ca‐sulfate (based on CheMin analyses from Rampe et al., 2020) and rock strength (Figure 14) between the four Upper Murray rocks that have calculated strengths available in Peters et al. (2018). ChemCam LIBS analyses have shown that most drill targets have some regions with locally enhanced (>13 wt.%) CaO, suggesting the presence of a localized Ca‐sulfate cement (Newsom et al., 2017). While there are Ca‐sulfate veins present near some of these drill holes, ChemCam Remote Microscopic Imager (RMI) images show that most of the localized regions with high CaO did not sample a vein but instead are located in areas that appear texturally and morphologically similar to other localized regions with low CaO (Newsom et al., 2017). Thus, the abundance of CaO (potentially indicating Ca‐sulfate) is not solely the result of sampling Ca‐sulfate veins but could represent a cementing material within the outcrop. While we do not yet have quantitative strengths for the Duluth and VRR drill targets, this trend found among the Murray targets could suggest that a Ca‐sulfate cement is one reason why VRR is so erosionally resistant. There were no significant correlations found between amorphous abundance and rock strength or between any other chemical component (elemental or mineralogical) other than with the abundance of Ca‐sulfate.

Figure 14.

Comparison between inferred rock strength from drill telemetry (x axis; Peters et al., 2018) and Ca‐sulfate abundance from CheMin analyses (y axis; Rampe et al., 2020) shows a strong positive correlation between the four Upper Murray drill targets. The Duluth and VRR drill targets are not included because they do not have quantitative strengths available. The x‐axis error bars represent the range of possible strengths listed in Peters et al. (2018).

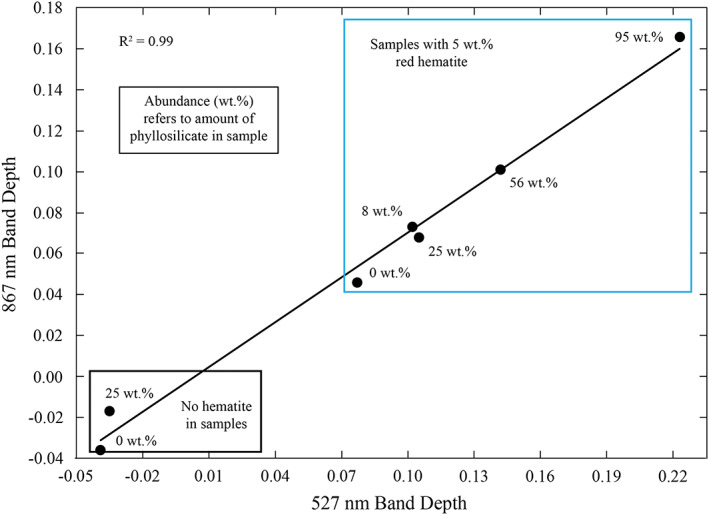

5.5. Laboratory Mixture Spectral Parameters

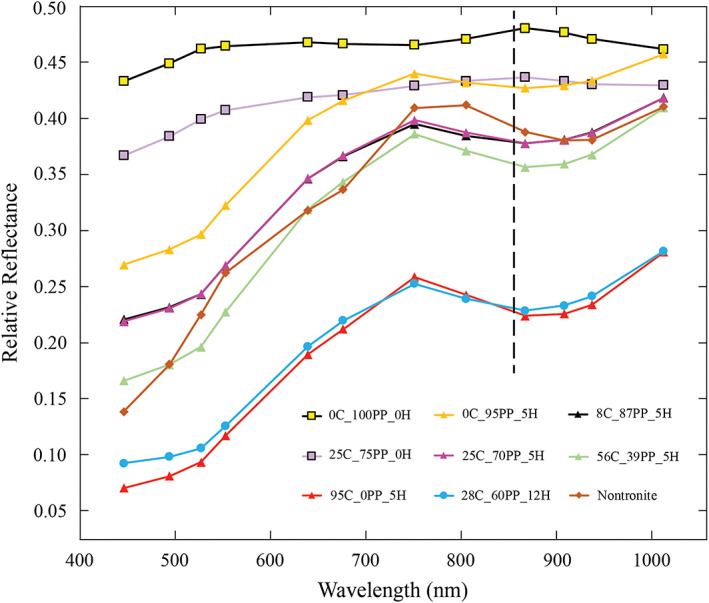

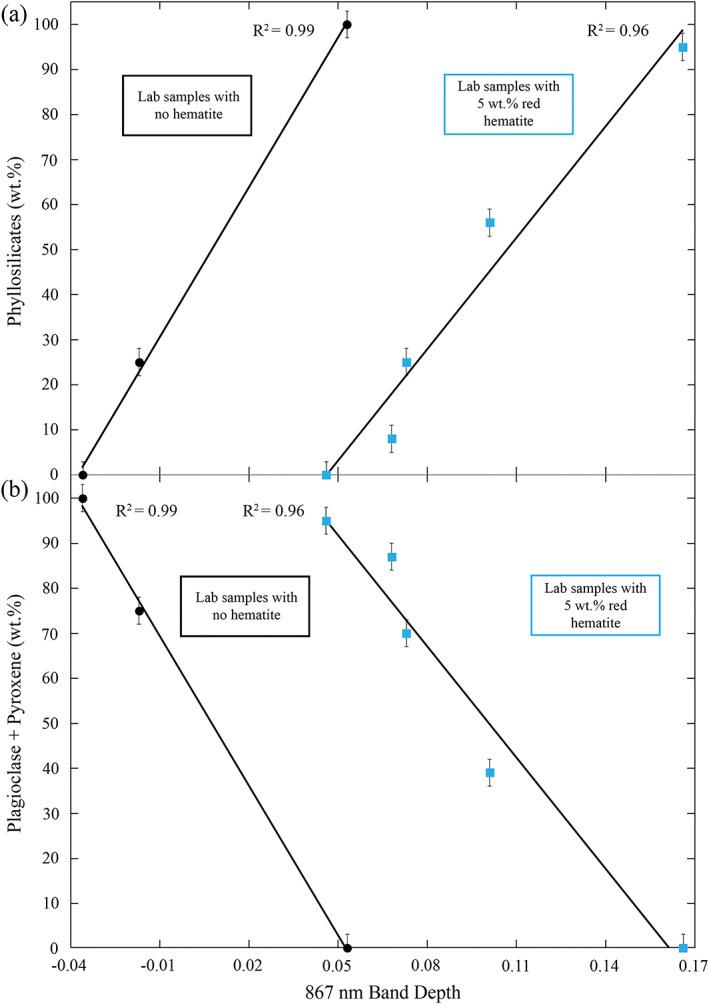

Figure 15 presents spectra of the laboratory mixtures (Table 2) and nontronite end‐member convolved to Mastcam filter wavelengths to demonstrate variations in band depths and band minima of the near‐IR absorption feature as a function of different mixtures. Mixtures with 5 wt.% red crystalline hematite demonstrate that even just a small abundance can shift the band minima from greater than 1,000 to ~860 nm. These laboratory results show a strong positive trend between phyllosilicate abundance and 867 nm band depth (Figure 16a), as well as a strong negative correlation between pyroxene + plagioclase abundance and 867 nm band depth (Figure 16b). Additionally, lab analyses of the HWMK20 mixture with 5 wt.% red crystalline hematite and 23 wt.% nontronite showed that for larger hematite grain sizes (90–150 μm), the phyllosilicate absorption features were still recognizable in the spectrum (Figure 17). The hematite absorption feature at ~860 nm was not obviously apparent until the hematite grains were <20 μm. Lab results show that grain‐size variations can not only change the band depth but also cause the band minima to shift from ~920 to ~860 nm (Figure 17) with variations in hematite grain size.

Figure 15.

Spectra of the laboratory mixtures (Table 2) and nontronite end‐member convolved to Mastcam filter wavelengths, showing changes in band depth and shifts in band minimum of the near‐IR absorption feature. The legend entries denote the fractions of nontronite clay (C), plagioclase + pyroxene (PP), and hematite (H) in the mixture represented. The black dashed line indicates the location of the 860 nm wavelength. The average error is 0.008, which is about the size of the markers.

Figure 16.

Comparison of band parameters and mineral abundances of lab mixtures. Blue squares are mixtures with 5 wt.% red hematite, and black circles are mixtures with 0 wt.% hematite. (a) Strong positive correlation between phyllosilicate abundance and 860 nm band depth in the laboratory mixtures (Table 2). (b) Strong negative correlation between plagioclase + pyroxene abundance and 860 nm band depth in the laboratory mixtures (Table 2).

Figure 17.

Lab spectra of the HWMK20 mixture with different hematite grain sizes (Table 2), the nontronite NG‐1 end‐member (dashed purple line), and the HWMK20 end‐member (green line). The relative reflectance of the pure HWMK20 spectrum is offset by 0.1, and the nontronite spectrum is offset by 0.05.

6. Discussion

6.1. Controls on Multispectral Parameters

Prior to in situ observations of the northern portion of the Murray formation and VRR, ferric phyllosilicates had only been identified in the clay‐bearing unit south of VRR using longer wavelength (>1 μm) CRISM orbital observations (Fraeman et al., 2013; Milliken et al., 2010). Without CheMin XRD and SAM evolved gas analyses of in situ samples the presence of ferric phyllosilicates on VRR and in the Murray formation below the ridge would have only been speculative. Mastcam wavelengths do not extend past 1 μm and can only use the ~920 nm absorption feature to identify ferric phyllosilicates. However, as shown above in Figure 7, the Mastcam spectra of the eight drill targets discussed do not show evidence for a prominent absorption feature in that region. The fact that the near‐IR Mastcam absorption feature is centered at ~860 nm suggests that the ferric phyllosilicate absorption feature was overwhelmed by the spectral signature of red crystalline hematite. It was only in correlating the Mastcam 867 nm band depths of the drill tailings to the CheMin crystalline phyllosilicate abundances (Figure 11b) that the effect of the ferric phyllosilicates on Mastcam spectra was realized. While the abundance of phyllosilicates appears to be the main control on depth of the 867 nm absorption feature, the presence of red crystalline hematite is still controlling the wavelength position of the near‐IR feature in Mastcam spectra. Therefore, both ferric phyllosilicates and hematite are necessary to explain the Mastcam spectra shown for the eight drill targets discussed. The purpose of the new lab work was to validate the possibility of ferric phyllosilicates controlling the depth of an ~860 nm absorption feature without variations in hematite abundance (Figure 16).

Hematite and iron‐bearing phyllosilicates have band minima near 860 nm (Figure 4), whereas augite exhibits a band maximum near 860 nm. All three of these minerals were detected to varying degrees by CheMin in the drill targets described above, and likely, all influence the wavelength position and depth of the broad near‐IR absorption feature observed in Mastcam spectra. In our laboratory mixtures with fixed hematite abundance, the band depth at 860 nm is observed to increase with increasing phyllosilicate abundance, but the band position remains at 860 nm (Table 2). We interpret this as being due to an increase in the overall 800–1,000 nm absorption in the mixture caused by a very broad near‐IR band in iron‐bearing phyllosilicates. However, the phyllosilicate absorption is so broad and shallow that it does not significantly alter the band minimum in the mixtures with hematite, which remains near 860 nm in convolved data. The addition of augite in our mixtures also changes the band depth at 860 nm, but in the opposite way from phyllosilicates. Specifically, because the pyroxene we used has a relative reflectance *maximum* near 860 nm and a broad absorption at longer near‐IR wavelengths, the observed band depth at 860 nm in our mixtures actually decreases with increasing pyroxene abundance. However, like for the addition of phyllosilicates, the addition of pyroxene does not noticeably change the wavelength position of the broad near‐IR absorption band in our mixtures, which remains near 860 nm.

Therefore, based on our mixture studies, the presence of hematite (in relatively low abundance) is hypothesized to be the reason for the wavelength position of the 860 nm band minimum observed in Mastcam spectra, while variable abundances of iron‐bearing phyllosilicates and pyroxene are hypothesized to be the dominant sources of variations in the 860 nm band depth. Understanding how the combination of minerals affects the spectral signature of surface materials is crucial to maximizing interpretations of visible/near‐IR spectral observations both from orbit and from the surface of any planet.

One example of the interplay between these minerals is the comparison of the Oudam drill tailings spectrum to that of the laboratory mixture with only plagioclase and pyroxene and no phyllosilicate or hematite (Figure 18). The lack of a red absorption edge and no 860 nm absorption in the laboratory spectrum is consistent with the fact that this mixture has no fine‐grained, red hematite. Oudam is the drill target with the lowest phyllosilicate abundance (~3 wt.%) and has the second highest hematite (~13.9 wt.%) and plagioclase + pyroxene abundances (~33 wt.%). Despite the abundance of hematite, Oudam lacks an appreciable near‐IR (860 nm or greater) absorption feature. The minimal amount of phyllosilicates suggests that ~3 wt.% phyllosilicates may not be enough to cause a detectable Mastcam absorption feature near ~920 nm. The similarity in the slope of both the Oudam and lab spectra from 908–1,012 nm suggests that the availability of longer near‐IR wavelengths may have revealed a near‐IR absorption feature longward of 1,000 nm in the Oudam spectrum. A longer near‐IR absorption feature would be consistent with the abundance of plagioclase and pyroxene in the Oudam sample.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the Oudam drill tailings (black diamonds) to the lab mixture (blue circles) with only plagioclase and pyroxene. Lab spectrum scaled to Oudam at 751 nm. The y‐axis error bars are about the size of the markers for both the Mastcam and lab spectrum.

There are multiple lines of evidence from both rover and laboratory data that factors other than variations in red hematite abundance can vary the depth of the 860 nm absorption feature. If red hematite abundance was the dominant factor contributing to the 867 nm absorption in spectra of the drill tailings we would expect Stoer, which has the greatest abundance of crystalline hematite, to have the strongest 867 nm band depth. This is not the case in the Mastcam multispectral data, however, which show that Stoer has a fairly weak 867 nm band depth and a 750–840 nm slope more like the gray targets Highfield and Oudam (Tables 4 and 5 and Figure 11). Additionally, results from our laboratory mixtures show considerable variation in the depth of the 860 nm absorption feature, despite the constant 5 wt.% abundance of red hematite.

Another possible contributing factor to the depth of the 867 nm absorption feature is a change in grain size. During the nominal drilling protocol, the powdered drill sample is passed through a sieve before reaching the CheMin instrument, located inside the rover body. Therefore, grains in the Oudam, Marimba, Quela, and Sebina samples analyzed by CheMin are 150 μm or smaller. However, for the new FEDuP drilling protocol, CheMin receives the sample directly from the drill bit. This means the Duluth, Stoer, Highfield, and Rock Hall sample grain sizes are less constrained. While the rover cannot directly measure grain sizes of the drill samples, we can use Mastcam multispectral and ChemCam relative reflectance data with results from CheMin analyses to constrain the relative grain‐size variations between drill samples. For example, the red/blue ratio and ~530 and ~860 nm band depths in spectral data increase with decreasing grain size (smaller than ~100–200 μm; cf. Johnson et al., 2019; Lane et al., 1999). This is also shown in Figure S1, which plots variations in the 527 and 867 nm band depths as a function of hematite grain size from the laboratory mixture containing 23/65/5 wt.% phyllosilicates/pyroxene + plagioclase/hematite (Table 2).

However, new lab work shows that the 527 and 867 nm absorption bands for the laboratory mixtures with constant 5 wt.% hematite abundance (grain size 76–106 mm) can vary independently of grain‐size variations (Figure 19 and Table 2). The results do suggest that the presence of red crystalline hematite is required for appreciable absorptions at 527 and 867 nm. This affirms that greater phyllosilicate abundances can independently increase band depths in the types of mixtures studied here (cf. Ehlmann et al., 2009; Roush et al., 2015). Thus, while variations in grain size could affect the band depth of Mastcam spectra, it is not a unique source of band depth variations. This suggests that the lack of a correlation among the two possible outlier targets, Marimba and Rock Hall, in Figure 13b, and the weaker overall correlation when all targets are considered, is perhaps more consistent with the 867 nm band depths of the drill samples studied here being controlled mainly by the abundances of ferric phyllosilicates and ferrous minerals rather than grain size.

Figure 19.

Comparison of the 867 and 527 band depths for lab mixtures where hematite grain size and abundance are constant in mixtures with hematite. The strong trend between the two parameters suggests that variations in band depth can occur even when grain size remains constant.

7. Depositional and Postdepositional History of VRR

The Mastcam and ChemCam spectra discussed above do not show any variations correlated with stratigraphic location of the drill target. In fact, multiple instruments onboard Curiosity have shown a lack of drastic differences in the composition of Upper Murray formation targets north of VRR and VRR targets (Fraeman, Edgar, et al., 2020; Frydenvang et al., 2020; Rampe et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020). The spectral and compositional similarities between the targets discussed here suggest that all of the targets formed in similar depositional environments. Multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain the abundance of ferric phyllosilicates and hematite and lack of aluminum‐rich phyllosilicates. Hurowitz et al. (2017) suggested a stratified lake environment to explain the mineralogical variations seen in the Murray. The samples discussed above would have formed in the shallow portion of the lake where the oxidant was in greater abundance than soluble Fe2+ and thus able to oxidize the ferrous iron and precipitate ferric minerals. While this explanation explains the lack of significant mineralogical differences, it does not provide an explanation for the erosional resistance of VRR. Thus, the erosional resistance is not likely caused by major mineralogical variations and instead is the result of postdepositional processes like cementation.