Abstract

SARS CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus which has caused many deaths in the recent pandemic. This study aimed to determine zinc, copper and magnesium status on pregnant women with COVID-19. 100 healthy (33/32/35) and 100 SARS-CoV-2 positive (34/33/33) pregnant women were included in the study according to their trimesters. Blood samples were obtained from the patients along with the initial laboratory tests for clinical outcomes upon their first admission to hospital. In the first and third trimesters serum zinc level was lower (p:0,004 and p:0,02), serum copper level was higher (p:0,006 and p:0,008), the Zn / Cu ratio decreased(p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001) and the serum magnesium level was higher(p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001) in the COVID-19 group.In the second trimester COVID-19 patients had lower serum zinc (p:0,05) and copper levels (p:0,0003) compared to controls. Disease severity correlated with zinc/copper ratio in COVID19 patients (p:0.018, r:-0.243). Serum zinc and Zn/Cu ratio levels had a negative relationship with acute phase markers such as IL-6, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, procalcitonin and C-reactive Protein. Also, increased serum magnesium level may play a role in decreased white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte cell count and increased CRP levels in the third trimester. This study indicated that trace element status changed in pregnant women with COVID-19. The effect of trace elements on pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 infection was investigated in comparison with healthy pregnant women for the first time. This effect will be revealed better in more comprehensive studies to be planned in the future.

Keywords: Copper, COVID-19, Magnesium, Infection, Pregnancy, Zinc

Introductıon

SARS-CoV is a virus which is capable to bind the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor that presents in several locations such as lung alveolar epithelial cells, enterocytes, endothelial cells and arterial smooth muscle cells in the human body. This novel coronavirus has caused many deaths in the recent pandemic. Evidence to date suggests that in the severe COVID-19 cases, cytokine storm syndrome accompanies the infection.

In a systematic review of 385 pregnant women from 33 studies with COVID-19, it was shown that pregnant women with mild, severe and critical levels were 95.6%, 3.6% and 0.8%, respectively. In this review, 17 pregnant women needed intensive care and 6 pregnant women needed mechanical ventilation. One maternal death has occurred. Of the 252 women who gave birth, 69.4% of them had cesarean section and 30.6% of them had vaginal delivery. Four neonates were SARS-CoV-2 positive, there were two stillbirths and one neonatal death [1].

According to data obtained from 108 pregnant women with COVID-19, lymphocytopenia was reported in the 59% of them with elevated C-reactive protein levels (70%) [2]. In another systematic review study of pregnant women with COVID-19 was concluded that the adverse outcomes are not common however our knowledge is still very limited about SARS-COV-2 and its effects on pregnancy [3].

The recent studies showed that zinc status is a critical factor that can influence antiviral immunity, particularly as zinc-deficient populations are mostly at risk of acquiring viral infections. Zinc is a component of many viral enzymes, proteases, and polymerases and cellular and systemic zinc homeostasis have the importance to prevent the viral infections. Despite the lack of clinical data, certain indications suggest that modulation of zinc status may be beneficial in COVID-19. In vitro experiments of Velthuis et al., it was shown that Zn+2 cations especially in combination with zinc ionophore pyrithione were shown to inhibit SARS-coronavirus RNA polymerase activity by decreasing its replication [4]. Also, pregnant women need more zinc intake because of its quite important roles for both maternal and neonatal health such as fertility for pre-pregnancy, on growth and development during pregnancy and the neonatal period [5]. But the association between the zinc level in pregnancy and COVID-19 is still unclear.

In humans, copper is involved in the structure of Cytochrome C-oxidase and steps associated with oxidative stress, but high copper levels may have negative effects during inflammation. The balance between zinc and copper is important for the zinc to neutralize the negative effects that copper may cause. Furthermore copper is an essential trace element for pathogens as well as for humans [6]. As a common feature of the infection, regardless of the agent (virus, bacteria, fungi), there is a progressive increase in serum copper [7–9]. But, there is no data about copper levels during COVID-19 infection not only in pregnant women but also in adults.

Magnesium is one of the important ions which is required as a cofactor for ATP enzyme that is involved in many essential enzymatic reactions. It has also immune importance that Mg2+ has a role on CD8+ T cell activation in infection by regulating the active sites of specific kinases [10]. A recent study has shown that serum magnesium level might have a protective effect against lung function loss in asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is an important result to understand the potential relationship between magnesium and pulmonary outcomes of COVID-19 disease [11]. To our knowledge, there is no study evaluating the relationship between magnesium and COVID-19 infection prior to this study. Also, it is of additional importance to evaluate pregnant COVID-19 patients because magnesium is a frequently used trace element for treatment [12, 13] during pregnancy.

This study aimed to evaluate the status of zinc, copper and magnesium in pregnant women diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection by comparing with the trimester clinical outcomes of healthy pregnant women.

Material and Methods

Study Groups & Ethics

Pregnant women who were admitted to Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Turkish Ministry of Health Ankara City Hospital between 11 May 2020 and 30 August 2020 were included in the study. The groups consist of the SARS-CoV-2 positive and control group with similar clinical and demographic characteristics. For the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test of the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal samples were evaluated [14]. Both the Turkish Ministry of Health and institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol (E1-20–1009) and informed consent was obtained from all patients. All COVID-19 cases were managed with guidance by the national guideline.

Examination of Biochemical and Clinical Profile

Blood samples were obtained from the patients along with the initial laboratory tests on the first admission to the hospital. Demographic features, clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters were analyzed. Maternal age, body-mass index (BMI)(kg/m2), gravidity, parity, comorbid conditions, gestational age, pregnancy status, obstetric complications, haemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), white blood cell, platelet, lymphocyte, neutrophil counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, interleukin 6 (IL-6), ferritin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, liver function tests (Aspartat Aminotransferase, Alanine Amino Transferase) were obtained to determine biochemical and clinical profile of patients.

Measurement of Tissue Trace Element Concentrations

Zinc, copper and magnesium levels were analyzed with atomic absorption spectroscopy. Perkin Elmer Analyst 800 device and “WinLab32” program were used for atomic absorption spectroscopy method. The calibration curve was generated following to guideline with standard solutions of each trace element, 2 repetitive measurements of each sample were measured [15].

Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (Armonk, NY, USA) software was used for statistical analysis and the data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median an minimum maximum values according to normal distribution. Student T test was used to analyze differences between study groups and Pearson correlation was used for correlation analysis between data. p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. Graphpad PRISM 6.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for visualizing the data.

Results

Totally 200 pregnant women were included in this study, the number of pregnant with COVID-19 infection were 100 and the other 100 patients were also healthy pregnant women. Each group was divided into trimesters: Respectively Thirty-four, 33 and 33 patients were in the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy in the COVID-19 group. On the other hand, 33, 32 and 35 patients were in the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy in the control group, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characterictics of SARS-CoV-2 ( +) pregnant women and controls

| Variables | SARS-CoV-2 ( +) | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Median |

SD Min–Max |

Mean Median |

SD Min–Max |

||

|

Age year |

1st Trimester | 28* | 17–38 | 26* | 19–34 |

| 2nd Trimester | 29 | 18–41 | 27 | 17–41 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 30 | 22–41 | 26 | 19–41 | |

|

BMI kg/m2 |

1st Trimester | 25,65 | 3,96 | 25,60 | 4,46 |

| 2nd Trimester | 26,72 | 3,32 | 26,02 | 5,14 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 29,11 | 5,68 | 28,36 | 3,34 | |

| Gestational Age | 1st Trimester | 8,5 | 5–14 | 9 | 5–14 |

| 2nd Trimester | 25 | 17–28 | 25 | 15–28 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 35 | 29–39 | 35 | 28–40 | |

| Gravidity | 1st Trimester | 2 | 1–7 | 2 | 1–4 |

| 2nd Trimester | 2 | 1–7 | 2 | 1–6 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 2 | 1–7 | 2 | 1–5 | |

| Parity | 1st Trimester | 1 | 0–5 | 1 | 0–2 |

| 2nd Trimester | 1 | 0–6 | 1 | 0–5 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 1 | 0–4 | 1 | 0–3 | |

| WBC per ml | 1st Trimester | 5380** | 3320–15,620 | 8300** | 3630–12,860 |

| 2nd Trimester | 5970*** | 3490–10,810 | 9435*** | 4040–15,030 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 8050*** | 3930–14,380 | 9220*** | 5400–14,140 | |

| Neutrophil per ml | 1st Trimester | 3735* | 1710–14,030 | 5710* | 2150–9460 |

| 2nd Trimester | 4310*** | 2350–8140 | 6635*** | 2750–11,450 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 5950*** | 2100–10,160 | 6810*** | 3830–10,110 | |

|

Lymphocyte per ml |

1st Trimester | 1270*** | 520–2600 | 1900*** | 460–2850 |

| 2nd Trimester | 1160*** | 360–2220 | 1815*** | 930–3200 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 1280*** | 350–3330 | 1700*** | 1070–3230 | |

|

CRP mg/dl |

1st Trimester | 13,2* | 14,48 | 7,36* | 7,9 |

| 2nd Trimester | 29,49* | 52,71 | 7,27* | 4,92 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 22,93* | 27,88 | 5,11* | 3,20 | |

| ESR | 1st Trimester | 29,40*** | 5,71 | 15,78*** | 7,48 |

| 2nd Trimester | 30,27 | 11,76 | 28,03 | 13,65 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 37,90 | 15,85 | 35,43 | 15,40 | |

|

IL-6 pg/ml |

1st Trimester | 8,53** | 7,88 | 3,56** | 0,841 |

| 2nd Trimester | 9,73 | 11,19 | 5,82 | 9,82 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 18,99 | 24,63 | 3,80 | 1,10 | |

|

Procalcitonin ng/ml |

1st Trimester | 0,037** | 0,01 | 0,026** | 0,005 |

| 2nd Trimester | 0,35 | 1,73 | 0,026 | 0,005 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 0,05 | 0,04 | 0,03 | 0,01 | |

|

Ferritin ng/ml |

1st Trimester | 39,44 | 50,35 | 22,78 | 20,21 |

| 2nd Trimester | 61,03 | 156,11 | 14,10 | 9,17 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 31,39 | 38,95 | 13,45 | 16,20 | |

|

Haemoglobin g/dl |

1st Trimester | 12,46 | 1,08 | 12,86 | 1,04 |

| 2nd Trimester | 11,20* | 1,14 | 12,05* | 0,99 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 10,96** | 1,16 | 11,46** | 0,98 | |

|

Hematocrit % |

1st Trimester | 37,45* | 2,80 | 38,97* | 3,15 |

| 2nd Trimester | 34,25* | 3,43 | 37,12* | 2,93 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 33,58** | 3,22 | 35,62** | 2,66 | |

|

BUN mg/dl |

1st Trimester | 18,55 | 4,80 | 19,63 | 5,61 |

| 2nd Trimester | 14,36* | 4,08 | 17,59* | 3,90 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 16,39** | 7,25 | 16,85** | 4,35 | |

|

Creatinine mg/dl |

1st Trimester | 0,53 | 0,08 | 0,55 | 0,07 |

| 2nd Trimester | 0,45 | 0,09 | 0,47 | 0,08 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 0,47 | 0,09 | 0,47 | 0,08 | |

|

ALT IU |

1st Trimester | 29,26 | 26,15 | 20,75 | 17,46 |

| 2nd Trimester | 31,90* | 33,70 | 18,90* | 8,39 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 20,63* | 13,59 | 13,55* | 13 | |

|

AST IU |

1st Trimester | 22,41* | 15,25 | 14,57* | 7,64 |

| 2nd Trimester | 41,87* | 63,91 | 15,59* | 4,47 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 23,03* | 13,12 | 15,35* | 3,96 | |

ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase, BUN: Blood urea nitrogen, CRP: C-Reactive Protein, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, IL: Interleukine, IU: International Unit, SD: Standart Deviation, WBC: White Blood Cell. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

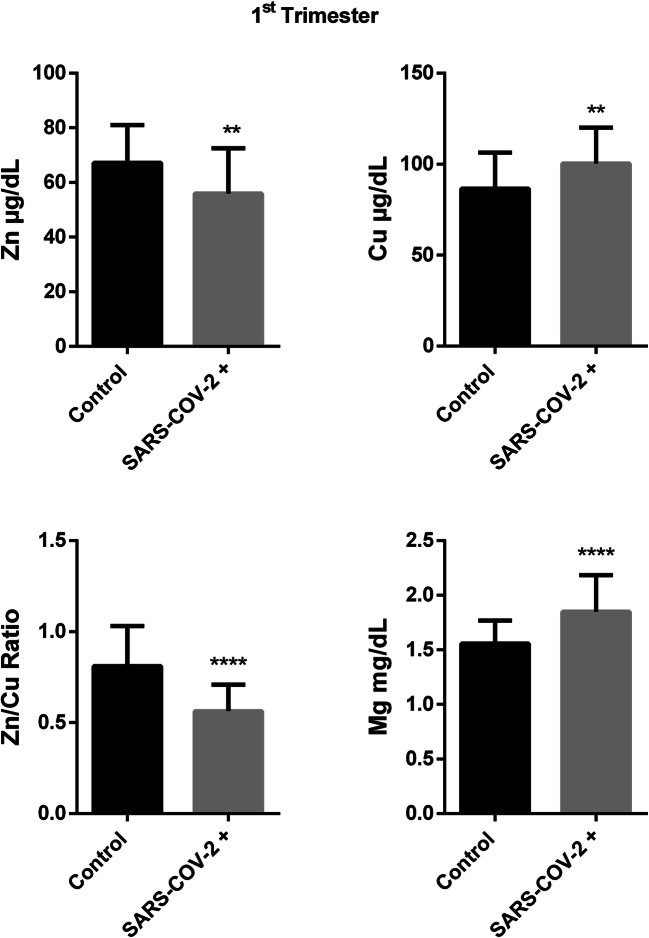

In the first trimester, serum zinc level was found significantly lower in pregnant group with COVID-19 compared to control (67,19 ± 13,87 vs 55,97 ± 16,57, p: 0,004). Serum copper level was higher in patient group than in control ones (86,56 ± 19,70 vs 100,4 ± 19,73, p:0,006) that cause important difference in Zn/Cu ratio between groups (0,811 ± 0,219 vs 0,563 ± 0,144, p < 0,0001). Serum Magnesium level was also significantly higher in COVID-19 group compared to control (1,557 ± 0,211 vs 1,848 ± 0,335, p < 0,0001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trace element results in first trimester of SARS-Cov-2 ( +) and control group.(Mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

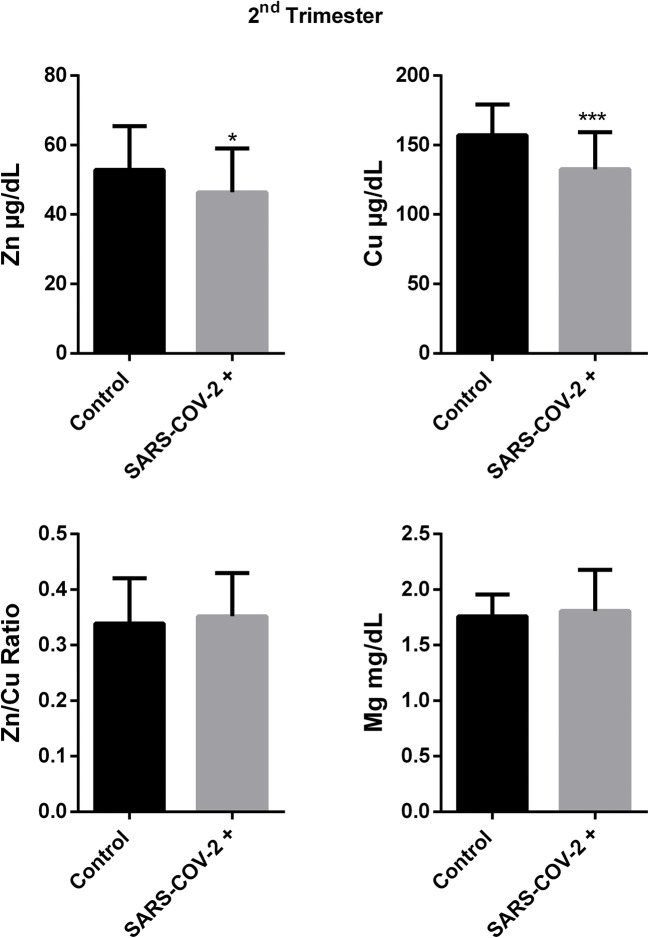

It was observed that zinc and copper levels were different between patient and control group during the second trimester. Serum zinc level was lower level in pregnant group with COVID-19 than control similar to first trimester (52,84 ± 12,57 vs 46,38 ± 12,66, p:0,05). Although serum copper level was higher in patients in the first trimester, it was seen that copper level was decreased in SARS-CoV-2( +) group compared to control in the second trimester (157,2 ± 22,16 vs 132,6 ± 26,66, p:0,0003). Zn/Cu ratio (0,339 ± 0,081 vs 0,351 ± 0,077, p: 0,529) and magnesium level (1,759 ± 0,195 vs 1,817 ± 0,387, p: 0,467) wasn’t found different between groups in the second trimester(Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Trace element results in second trimester of SARS-Cov-2 ( +) and control group.(Mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

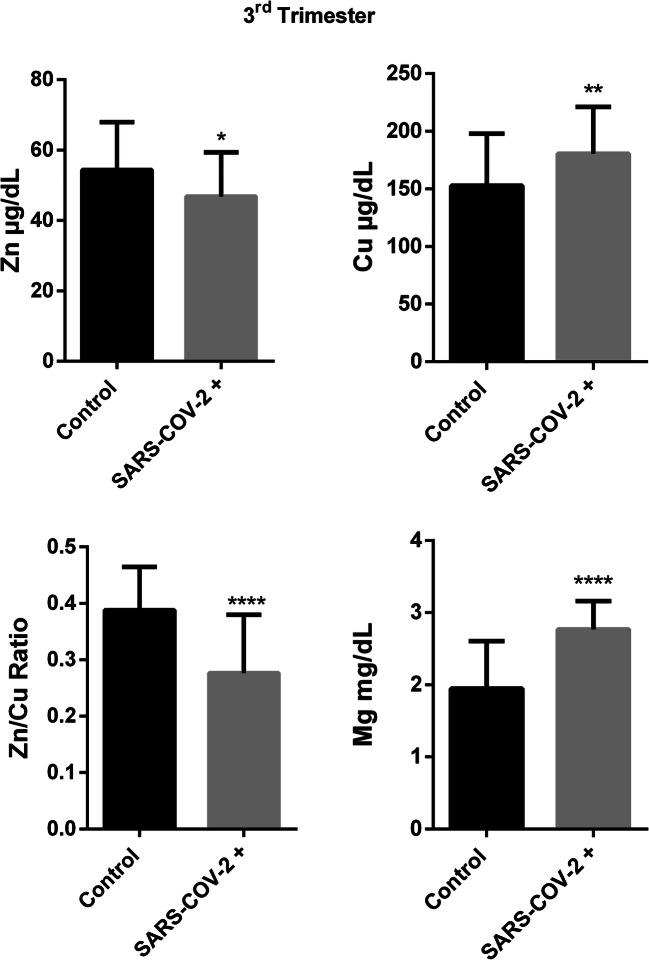

Third trimester data showed that serum zinc level was lower in COVID-19 group than controls (54,37 ± 13,57 vs 46,82 ± 12,51, p:0,02). Serum copper level was found higher in COVID-19 group compared to control similar to first trimester results in the third trimester (152,8 ± 45,27 vs 180,5 ± 40,56, p:0,008). Zn/Cu ratio was found significantly lower in pregnant group with COVID-19 infection compared to control in the third trimester (0,411 ± 0,129 vs 0,276 ± 0,103, p < 0,0001). Serum magnesium level was found significantly higher in COVID-19 group compared to healthy pregnant women in the third trimester(1,947 ± 0,657 vs 2,767 ± 0,394, p < 0,0001)(Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Trace element results in third trimester of SARS-Cov-2 ( +) and control group.(Mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

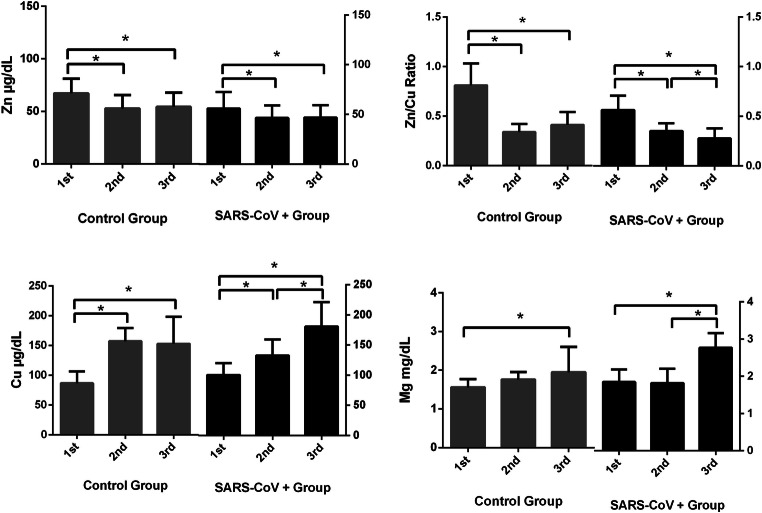

As it was shown in Fig. 4, trace element status was changed during pregnancy period. Anova test results showed that both in control and COVID19 group, there were significant differences in serum magnesium, zinc, copper and zinc/copper ratio between trimesters (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Changes in trace element concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 ( +) and control groups during pregnancy according to trimesters

Correlation Analysis

According to correlation analysis, disease severity correlated with zinc/copper ratio (p:0.018, r:-0.243) while it was tend to be correlated with serum zinc level (p:0.07, r:-0.182) and there wasn’t correlation between disease severity and serum magnesium and copper levels.

In first trimester, zinc concentration was significantly correlated with IL-6 level (p:0.003, r:-0.357) and ESR (p:0.01, r:-0,312). Copper concentration showed correlation with WBC (p:0.03, r:-0.263), procalcitonin (p:0.03, r:0.262), ALT (p:0.02, r:0.277) and AST (p:0.01, r:0.298) levels. There were correlations between Zn/Cu Ratio and IL-6 (p:0.01, r:-0.306), lymphocyte (p:0.01, r:-0.217), ESR (p:0.0009, r:-0.404) and procalcitonin (p:0.03, r:-0.270). Magnesium concentration of pregnant women was correlated with WBC (p:0,0003, r:-0,435), Neutrophil (p:0,002, r:-0,366), Lymphocyte (0,002, r:-0,378), ESR (p:0,001, r:0,384), haematocrit (p:0.02, r:-0.276) and creatinine (p:0,04, r:-0,250).

Second trimester data of pregnant women showed that serum zinc level correlated with procalcitonin (p:0.04, r:-0.254) and BUN (p:0.02, r:0.279). Copper level was correlated with IL-6 (p:0.01, r:-0.312), WBC (p:0.02, r:0.295), Neutrophil (p:0.03, r:0.264), Lymphocyte (p:0.01, r:0.308), CRP (p:0.008, r:-0.334), procalcitonin (p:0.01, r:-0.327), ferritin (p:0.008, r:-0.334), hemoglobin (p:0.008, r:0.335), hematocrit (p: 0.008, r:0.333), BUN (p:0.01, r:0.298) and creatinine (p:0.03, r:0.271).

Third trimester correlation data showed that zinc level was correlated with CRP (p:0.004, r:-0.360). Copper level was found to be correlated with Lymphocyte (p:0.01, r:0.355), ALT (p:0.02, r:0.278). Zn/Cu ratio was correlated with IL-6 (p:0.01, r:-0.308), CRP (p:0.004, r:-0.463) levels. Magnesium concentration was correlated with Lymphocyte (p:0.04, r:-0.254), CRP (p:0.03, r:0.271), ferritin (p:0.03, r:-0.272) and creatinine (p:0.01, r:0.306) levels.

Discussion

Impaired Balance of Zinc and Copper in Pregnant Women with COVID-19

Our study showed that serum zinc level has relation with infection and inflammation status. As we mentioned before, serum zinc levels decreased in COVID-19 patients in all trimesters compared to healthy pregnant women (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Also serum zinc levels from different trimesters were found negatively correlated with acute phase markers such as IL-6, ESR, procalcitonin and CRP.

Zinc is well-known with its regulatory character on inflammatory responses via Nuclear Factor Kappa B(NF-κB) signaling pathway to control oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines [16]. However, during the acute-phase of infection, zinc uptake into cells increase and zinc is placed within zincosome or organelles, which may lead to decreased serum zinc levels. Also, during acute phase response, urinary zinc excretion was shown to be increased and it was found to be correlated with increased CRP [17]. As a key cytokine of acute phase response of human body, IL-6 is important for diagnosis, and prognosis in different diseases based on immunity [18, 19]. It was observed that IL-6 stimulated the zinc transporter (ZIP14) which is settled in cell membrane and ease to zinc entering into cells [20, 21]. Therefore, with these mentioned mechanisms, zinc has an importance on inflammatory response and tends to decrease during acute phase by increased zinc uptake into cells which indicates that maintenance of serum zinc uptake is necessary in pregnant women with infection.

In a recent study in COVID-19 patients showed that the patients with low zinc level were found higher complication rate (p:0.009) such as prolonged hospital stay (p:0.05), received corticosteroid therapy (p:0.02) and increased mortality rates (18.5% vs %0). The odds ratio of complications associated with low level serum zinc was found to be 5.54 [22]. Our study was the first study which investigates zinc status in pregnant women with COVID-19 and similar results were found about zinc and COVID-19 relationship such as in the literature.

Our data showed that serum copper level elevated in pregnant women with COVID-19 in first and third trimester besides natural increase during pregnancy as it can be seen in Fig. 4.At the same time we observed control serum copper levels increased during the trimesters but according to T test results, COVID-19 patients had higher copper level than control group in the first and third trimesters (Figs. 1 and 3). Our study is the first study which indicates higher serum copper levels in pregnancy with COVID-19 infection however considering the other infectious diseases, there are similar results in the literature. When we look at other infections in the literature, Huang et al. showed that serum copper and urinary copper levels were increased in chronic Hepatitis B patients compared to control [23]. Serum copper level was found higher in HIV patients compared to control [24].

The decrease in zinc level with an increase in copper level leads to a very significant decrease in Zn/Cu Ratio of pregnant women with COVID-19 infection (Figs. 1 and 3). It is well-known that zinc and copper have a balanced mechanism in the human body therefore these results suggest that impaired Zn-Cu balance is also related with outcomes. As it can be seen in correlation analysis, Zn1/Cu ratio showed correlation with inflammatory and acute phase markers including IL-6, CRP, ESR, procalcitonin.

There was a decrease in serum copper level with COVID19 in only second trimester instead of increase such as first and third trimesters. It was thought that this result might be depended on a significant increase in serum copper level with the second trimester in the control group. There was slight increase in COVID19 serum copper level with the second trimester. These difference in increase rate (Fig. 4) between control and COVID19 group leads statistically significant difference in serum copper level between groups as shown in Fig. 2. The significant increase in serum copper levels with the second trimester in a healthy pregnancy was also stated in the literature [25, 26]. On the other hand, it should be stated that decrease trend in trace element status during pregnancy might be depended on the physiological changes which include volume expansion, hormonal changes, and increased trace element requirement with different trimesters. Micronutrient requirements might be changed with trimesters due to the role of micronutrients during pregnancy such as the formation of new cells and tissues, enzyme activity, signal transduction and transcription pathways, and combating oxidative stress [27, 28].

Is the Increase in Magnesium Levels Cause or Consequence?

As an important result of our study, serum magnesium level increased during pregnancy in COVID-19 group and especially it was observed that serum magnesium levels were significantly higher in COVID-19 pregnant women in the first and third trimesters than control pregnant women. Our correlation results showed that serum magnesium level might have a negative role on WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte cell concentrations and which might explain the correlation between serum magnesium level and CRP level in the third trimester. These results indicate that higher level magnesium might have a negative role in COVID-19 infection or infection cause a higher of serum magnesium in pregnant women. This is the first study which showed magnesium status in pregnant women with COVID-19 infection. However, considering the other cases in the literature there are interesting results.

Hafizi et al. observed higher level of serum magnesium in helicobacter pylori positive kidney transplant patients compared to helicobacter pylori negative ones (p:0,0005). Additionally, they mentioned that higher level of magnesium might aggravate H. pylori infection in kidney transplant patients [29].

It was observed in another study on visceral leishmaniasis (VL) infectious disease that chronic LV patiens had significantly higher serum magnesium level compared to both acute LV patients and healthy controls. They also suggested that higher serum magnesium levels reduced nitric oxide production, which may be associated with the chronic stage of the disease. Another finding was Mg2+dependent ecto-ATPase activity in parasite may avoid the microbicidal activity of macrophages. It is also important that the investigator found a decreased level of zinc and increased level of copper as well as increased level of magnesium in only chronic VL patients which researcher thought that might be predictive for clinical evaluation of chronic stage of VL infection [30]. In another similar study, it was observed that the serum magnesium level in malaria patients increased about threefold compared to controls. In this study, they also mentioned that the increase in magnesium levels may be due to hemolysis since red blood cells contain high amounts of magnesium [31]. In another study, a relationship was found between magnesium levels on admission and 30-day mortality in pneumonia patients. Mortality rates were 18.8%, 14.8% and 50% in patients with hypomagnesemic (< 1.35 mg / dl), normomagnesemic (1.35–2 mg / dl) and hypermagnesemic (> 2.4 mg / dl), respectively. Even, magnesium levels within the upper normal limit (2–2.4 mg/dl), was also associated with 30.3% mortality rates. The adjustments for several clinical parameters such as albumin, BUN and age didn’t change the results [32].

Conclusion

This study showed that in pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 in the first and third trimesters, serum zinc levels decreased and serum copper and magnesium levels increased compared to controls. The correlation between zinc, copper and magnesium changes and acute phase reactants in COVID-19 infection was demonstrated for the first time in pregnant women. These results showed zinc relation with COVID-19 disease which is recently debating. Furthermore, magnesium increase in pregnant women with COVID-19 should be concerned as magnesium is used as medication in the obstetric field for especially in the treatment of cramps.. For the first time, with this study, the effect of trace elements on pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 infection was investigated in comparison with healthy pregnant women. This effect will be revealed better in more comprehensive studies to be planned in the future.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Ankara City Hospital and Turkish Ministry of Health (E1-20–1009).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Elshafeey F, Magdi R, Hindi N, Elshebiny M, Farrag N, Mahdy S, Sabbour M, Gebril S, Nasser M, Kamel M. A systematic scoping review of COVID-19 during pregnancy and childbirth. Int J GynecolObstet. 2020;150(1):47–52. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: a systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obst Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:823–829. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Della Gatta AN, Rizzo R, Pilu G, Simonazzi G. COVID19 during pregnancy: a systematic review of reported cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Te Velthuis AJ, van den Worm SH, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. Zn2+ inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001176. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terrin G, Berni Canani R, Di Chiara M, Pietravalle A, Aleandri V, Conte F, De Curtis M. Zinc in early life: a key element in the fetus and preterm neonate. Nutrients. 2015;7(12):10427–10446. doi: 10.3390/nu7125542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kardos J, Héja L, Simon Á, Jablonkai I, Kovács R, Jemnitz K. Copper signalling: causes and consequences. CCS. 2018;16(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12964-018-0277-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilbäck N-G, Frisk P, Tallkvist J, Gadhasson I-L, Blomberg J, Friman G. Gastrointestinal uptake of trace elements are changed during the course of a common human viral (Coxsackievirus B3) infection in mice. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2008;22(2):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cernat R, Mihaescu T, Vornicu M, Vione D, Olariu R, Arsene C. Serum trace metal and ceruloplasmin variability in individuals treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(9):1239–1245. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besold AN, Culbertson EM, Culotta VC. The Yin and Yang of copper during infection. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2016;21(2):137–144. doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1335-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanellopoulou C, George AB, Masutani E, Cannons JL, Ravell JC, Yamamoto TN, Smelkinson MG, Jiang PD, Matsuda-Lennikov M, Reilley J. Mg2+ regulation of kinase signaling and immune function. J Exp Med. 2019;216(8):1828–1842. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye M, Li Q, Xiao L, Zheng Z. Serum magnesium and fractional exhaled nitric oxide in relation to the severity in asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmadi S, Naderifar M, Samimi M, Mirhosseini N, Amirani E, Aghadavod E, Asemi Z. The effects of magnesium supplementation on gene expression related to inflammatory markers, vascular endothelial growth factor, and pregnancy outcomes in patients with gestational diabetes. Magnes Res. 2018;31(4):131–142. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2019.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso LG, Prieto MP, Colmenero EG, Guisán AC, Albo MS, Fernández-Feijoo CD, Durán LG, Lorenzo JF. Prenatal therapy with magnesium sulfate and its correlation with neonatal serum magnesium concentration. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(02):170–176. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanacan A, Erol SA, Turgay B, Anuk AT, Secen EI, Yegin GF, Ozyer S, Kirca F, Dinc B, Unlu S. The rate of SARS-CoV-2 positivity in asymptomatic pregnant women admitted to hospital for delivery: experience of a pandemic center in Turkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ThePerkin-ElmerCorporation (1996) Analytical methods for atomic absorption spectroscopy. USA

- 16.Prasad AS, Bao B, Beck FW, Sarkar FH. Zinc-suppressed inflammatory cytokines by induction of A20-mediated inhibition of nuclear factor-κB. Nutrition. 2011;27(7–8):816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melichar B, Malír F, Tichý M. Urinary zinc excretion in patients with different disorders: the acute phase response in the kidney. Sbornik vedeckych praci Lekarske fakulty Karlovy university v Hradci Kralove. 1993;36(4–5):325–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unver N, McAllister F. IL-6 family cytokines: key inflammatory mediators as biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018;41:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Germolec DR, Frawley RP, Evans E (2010) Markers of inflammation. In: Immunotoxicity testing. Springer, Humana Press, pp 53–73

- 20.Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA, Rivera S, Blanchard RK, Aydemir TB, Knutson MD, Ganz T, Cousins RJ. Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to the hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(19):6843–6848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502257102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aydemir TB, Chang S-M, Guthrie GJ, Maki AB, Ryu M-S, Karabiyik A, Cousins RJ. Zinc transporter ZIP14 functions in hepatic zinc, iron and glucose homeostasis during the innate immune response (endotoxemia) PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e48679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jothimani D, Kailasam E, Danielraj S, Nallathambi B, Ramachandran H, Sekar P, Manoharan S, Ramani V, Narasimhan G, Kaliamoorthy I. COVID-19: poor outcomes in patients with Zinc deficiency. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y, Zhang Y, Lin Z, Han M, Cheng H. Altered serum copper homeostasis suggests higher oxidative stress and lower antioxidant capability in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Medicine. 2018;97(24):e11137. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno T, Artacho R, Navarro M, Perez A, Ruiz-Lopez M. Serum copper concentration in HIV-infection patients and relationships with other biochemical indices. Sci Total Environ. 1998;217(1–2):21–26. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vukelić J, Kapamadžija A, Petrović Đ, Grujić Z, Novakov-Mikić A, Kopitović V, Bjelica A. Variations of serum copper values in pregnancy. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2012;140(1–2):42–46. doi: 10.2298/SARH1202042V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awadallah S, Abu-Elteen K, Elkarmi A, Qaraein S, Salem N, Mubarak M. Maternal and cord blood serum levels of zinc, copper, and iron in healthy pregnant Jordanian women. J Trace Elem Exp Med. 2004;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/jtra.10032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Looman M, Geelen A, Samlal RA, Heijligenberg R, Klein Gunnewiek JM, Balvers MG, Wijnberger LD, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, Feskens EJ. Changes in micronutrient intake and status, diet quality and glucose tolerance from preconception to the second trimester of pregnancy. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):460. doi: 10.3390/nu11020460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabrizi FM, Pakdel FG. Serum level of some minerals during three trimesters of pregnancy in Iranian women and their newborns: a longitudinal study. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2014;29(2):174–180. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0336-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hafizi M, Mardani S, Borhani A, Ahmadi A, Nasri P, Nasri H. Association of helicobacter pylori infection with serum magnesium in kidney transplant patients. JRIP. 2014;3(4):101. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lal CS, Kumar S, Ranjan A, Rabidas VN, Verma N, Pandey K, Verma RB, Das S, Singh D, Das P. Comparative analysis of serum zinc, copper, magnesium, calcium and iron level in acute and chronic patients of visceral leishmaniasis. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013;27(2):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garba I, Ubom G. Potential role of serum magnesium measurement as a biomarker of acute falciparum malaria infection in adult patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2006;114(1–3):115–120. doi: 10.1385/BTER:114:1:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasser R, Naffaa ME, Mashiach T, Azzam ZS, Braun E. The association between serum magnesium levels and community-acquired pneumonia 30-day mortality. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):698. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3627-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.