ABSTRACT

Background: Both post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) have been included in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Although the validity of CPTSD has been controversial, a growing number of studies support the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD. However, the majority of this research has originated in high-income countries (HICs), whereas the prevalence of trauma experience associated with PTSD/CPTSD diagnosis is significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Objective: This study assessed whether a sample from an LMIC setting produced distinct classes that reflect ICD-11 criteria for PTSD and CPTSD. Furthermore, this study investigated whether childhood trauma distinguished between PTSD and CPTSD.

Method: International Trauma Questionnaire responses from a sample of South African university undergraduates were used as indicator variables in a latent class analysis (LCA). Chi-squared tests of independence and Kruskal–Wallis H tests were used to assess between-class differences.

Results: The LCA identified four distinct classes: a PTSD class with elevated symptoms of PTSD, but low endorsement of disturbances in self-organization (DSO; symptoms that are specific to CPTSD); a CPTSD class with elevated symptoms of PTSD and DSO; a DSO class with low symptoms of PTSD, but elevated symptoms of DSO; and a Low class with low endorsements on all symptoms. Regarding childhood trauma, participants in the CPTSD class had more severe childhood abuse and neglect, specifically emotional abuse and neglect, than participants in the PTSD class.

Conclusions: Findings were consistent with the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD symptom profiles in the ICD-11. Our findings support a similar qualitative distinction between PTSD and CPTSD in our LMIC context, as previously reported in HICs. This distinction is especially relevant in LMICs because of the significant number of individuals vulnerable to these disorders.

KEYWORDS: ICD-11, PTSD, CPTSD, ITQ, CTQ, LMIC, LCA

HIGHLIGHTS:

• Latent class analysis revealed distinct post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) classes in a sample of South African students. • Both symptom profile and childhood trauma severity differentiated between PTSD and CPTSD. • These findings are consistent with those reported in high-income countries.

Antecedentes: Tanto el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) como el trastorno de estrés postraumático complejo (TEPT-C) se han incluido en la 11ª edición de la Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (CIE-11). Aunque la validez del TEPT-C ha sido controvertida, un número creciente de estudios apoyan la distinción entre TEPT y TEPT-C. Sin embargo, la mayor parte de esta investigación se ha originado en países de ingresos altos (HIC en su sigla en inglés), mientras que la prevalencia de experiencias traumáticas asociadas con el diagnóstico de TEPT/TEPT-C es significativamente mayor en países de ingresos bajos y medios (LMIC en su sigla en inglés).

Objetivo: Este estudio evaluó si una muestra de un entorno de LMIC produjo clases distintas que reflejan los criterios de la CIE-11 para TEPT y TEPT-C. Además, este estudio investigó si el trauma infantil distinguía entre TEPT y TEPT-C.

Método: Las respuestas del Cuestionario Internacional de Trauma (ITQ en su sigla en inglés) de una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de Sudáfrica se utilizaron como variables indicadoras en un análisis de clase latente (LCA en su sigla en inglés). Se utilizaron pruebas de independencia de chi-cuadrado y pruebas H de Kruskal-Wallis para evaluar las diferencias entre clases.

Resultados: El LCA identificó cuatro clases distintas: una clase de trastorno de estrés postraumático con síntomas elevados de trastorno de estrés postraumático, pero baja validación de las alteraciones en la autoorganización (DSO en su sigla en inglés; síntomas que son específicos de TEPT-C); una clase de TEPT-C con síntomas elevados de TEPT y DSO; una clase de DSO con síntomas bajos de TEPT, pero síntomas elevados de DSO; y una clase baja con baja validación de todos los síntomas. Con respecto al trauma infantil, los participantes en la clase de TEPT-C tuvieron abuso y negligencia infantil más severos, específicamente abuso y negligencia emocional, que los participantes en la clase de TEPT.

Conclusiones: Los hallazgos fueron consistentes con la distinción entre los perfiles de síntomas de TEPT y TEPT-C según la CIE-11. Nuestros hallazgos apoyan una distinción cualitativa similar entre TEPT y TEPT-C en nuestro contexto de LMIC a lo reportado anteriormente en los HIC. Esta distinción es especialmente relevante en los países de ingresos bajos y medios debido al número significativo de personas vulnerables a estos trastornos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: CIE-11, TEPT, TEPT-C, ITQ, CTQ, LCA, LMIC

背景:创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 和复杂性创伤后应激障碍 (CPTSD) 均被纳入第11版《国际疾病分类》 (ICD-11) 。尽管CPTSD的效度一直存在争议, 越来越多的研究支持了PTSD和CPTSD之间的区别。但是, 这类研究大部分来自高收入国家 (HIC), 而有PTSD/CPTSD诊断的创伤经历流行率在中低收入国家 (LMIC) 明显更高。

目的:本研究评估了来自LMIC背景的样本是否产生了反映ICD-11 PTSD和CPTSD标准的不同类别。此外, 本研究考查了PTSD和CPTSD之间的童年期创伤是否存在区别。

方法:将南非大学本科生样本对国际创伤调查问卷 (ITQ) 的作答用作潜在类别分析 (LCA) 中的指标变量。卡方独立性检验和Kruskal-Wallis H检验用于评估类间差异。

结果:LCA确定了四个不同的类别:高PTSD, 低自组织失调症状 (DSO;CPTSD特有症状) 的PTSD类; 高PTSD, 高DSO症状的CPTSD类; 低PTSD, 高DSO症状的DSO类;所有症状均低的低症状类。对于童年期创伤, CPTSD类的参与者比PTSD类的参与者有更严重的童年期虐待和忽视, 尤其是情感虐待和忽视。

结论:研究结果与ICD-11中PTSD和CPTSD症状剖面的区别一致。我们的发现支持了PTSD和CPTSD在LMIC背景中存在与前人在HIC中报告的类似的定性区别。由于在LMIC中存在大量易患这些疾病的个体, 这一区别尤为重要。

关键词: ICD-11, PTSD, CPTSD, ITQ, CTQ, LCA, LMIC

1. Introduction

In accordance with an overarching emphasis on clinical utility, the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019) includes simplified diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and a related yet distinct diagnostic category, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). Whereas PTSD may follow a circumscribed traumatic event, risk factors for CPTSD include exposure to prolonged or repeated traumas, commonly occurring during childhood, from which escape is difficult or impossible, such as prolonged domestic violence or repeated childhood sexual or physical abuse (Hyland et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2019). The ICD-11 characterizes PTSD by three clusters of symptoms: re-experiencing of trauma in the present, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, and sense of current threat. ICD-11 criteria for CPTSD comprise the same PTSD symptoms and three additional symptom clusters that reflect disturbances in self-organization (DSO): affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbances in relationships. For both disorders, diagnosis follows if symptoms persist for several weeks and result in significant functional impairment. However, PTSD symptoms may lead to PTSD diagnosis only in the absence of DSO, whereas CPTSD requires endorsement of both PTSD and DSO symptoms. This hierarchical structure ensures that PTSD and CPTSD never co-occur.

Although the validity of CPTSD as a clinical syndrome has been questioned (Herman, 2012; Resick et al., 2012), primarily owing to overlapping symptomology with other trauma-related disorders (Wolf et al., 2015), there is now a significant body of literature that supports the hierarchical structure presented in the ICD-11. This includes a notable systematic review (Brewin et al., 2017) and a variety of validation studies: latent class analyses (Barbieri et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2020; Hyland et al., 2018; Jowett, Karatzias, Shevlin, & Albert, 2019; Karatzias et al., 2017), confirmatory factor analyses (Hyland et al., 2017; Karatzias et al., 2016; Kazlauskas, Gegieckaite, Hyland, Zelviene, & Cloitre, 2018; Murphy et al., 2020; Owczarek et al., 2020), and network analyses (Gilbar, 2020; Knefel et al., 2019, 2020; Knefel, Tran, & Lueger-Schuster, 2016; McElroy et al., 2019). These studies have used the only standardized self-report measure for symptoms of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD, the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ; Cloitre et al., 2018).

However, most of this research has been restricted to high-income countries (HICs), whereas significantly fewer studies have analysed samples from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); e.g. Uganda (Dokkedahl, Ovuga, & Elklit, 2015; Murphy, Elklit, Dokkedahl, & Shevlin, 2016, 2018); Angola (Rocha et al., 2019); Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria (Ben-Ezra et al., 2020; Owczarek et al., 2020); Ukraine (McElroy et al., 2019; Shevlin et al., 2018); and Lebanon (Hyland et al., 2018; Vallières et al., 2018). Further research in LMICs is therefore necessary to determine whether ICD-11 criteria for PTSD and CPTSD are internationally relevant.

Furthermore, many LMICs are vulnerable to risk factors that may lead to traumatic experience. The World Risk Report provides a comprehensive dataset of country vulnerability indices composed of various social, physical, economic, and environmental factors, such as malnutrition, extreme poverty, political corruption, illiteracy rate, and water resources (Day et al., 2019). Of 180 listed countries, all of those with vulnerability indices above the 46th percentile are LMICs.

Civil violence and post-conflict populations are also prevalent in many LMICs (Dorrington et al., 2014). Consistent with aetiological factors associated with CPTSD, trauma experience in these settings is therefore likely to be protracted and impact both adults and children. For example, approximately 40% of adult participants in samples from northern Uganda were abducted in the 1980s as child soldiers, and civil conflict is ongoing in the region (Dokkedahl et al., 2015; Murphy et al., 2016, 2018). In the case of South Africa, many people live in communities that are hubs of ongoing trauma, where violence is persistent and pervasive (Kaminer, Eagle, & Crawford-Browne, 2018), and many trauma survivors are children (Artz et al., 2016; Hsiao et al., 2018).

Somewhat surprisingly, the prevalence of PTSD does not follow this trend, with lifetime prevalence greater in some HICs than in LMICs, a phenomenon that Dückers, Alisic, and Brewin (2016) term the ‘vulnerability paradox’. For example, whereas South Africa and Iraq have reported lifetime prevalences of PTSD at 2.3% and 2.5% respectively, France and the USA report these statistics as 3.9% and 6.8%, respectively (Dückers et al., 2016). Considering (a) the discordance between rates of trauma experience and PTSD in many LMICs and (b) that trauma experience in these settings is commonly prolonged/repeated and experienced during childhood, it may be that conventional PTSD diagnosis fails to capture the full spectrum of clinical symptoms (Kaminer et al., 2018). In such contexts, it may be especially relevant to refine the pathological clinical profile that is associated with trauma.

The clinical utility of distinguishing between conventional PTSD and CPTSD lies in furthering the development of differential treatments for complex trauma. Therefore, LMICs characterized by disproportionately high rates of violence against children and multiple sources of ongoing trauma stand to benefit from the above distinction. In summary, our study aimed to use a sample from an LMIC setting characterized by both early onset and ongoing trauma (a) to examine the validity of the ITQ according to ICD-11 criteria, and (b) to test associations of CPTSD with childhood trauma. We set out to test the following hypotheses:

Analysis of the ITQ results will identify two distinct groups characterized by the following symptom profiles: (a) a PTSD symptom profile with high endorsement of PTSD symptoms and low endorsement of DSO symptoms, and (b) a CPTSD symptom profile with high endorsement of both PTSD and DSO symptoms.

Relative to a PTSD group, a CPTSD group will exhibit: (a) significantly more severe childhood trauma, and (b) significantly more types of childhood trauma exposure.

2. Method

2.1. Design, participants, and procedures

The data for this cross-sectional study were collected at a university institution in South Africa during a time of substantial civil unrest, violence, and student protest (Brits et al., 2019; Konik & Konik, 2018). Data were collected via online survey from undergraduate students, recruited using a research participation programme. Students were made aware of the study and invited to participate via online platforms and at the beginning of lectures. Conversational proficiency in English and minimum age of 18 years were the only eligibility criteria. Questionnaires measuring PTSD symptoms, DSO symptoms, and childhood trauma were compiled into the online survey using the Google Forms platform. All procedures in this study received ethical approval from the relevant bodies at our institution and participants provided electronic consent before commencing with any of the study measures.

A total of 625 response sets were recorded from the online survey, but the exclusion of responses due to multiple entries by the same participants reduced the final sample size to N = 576. The majority of the sample was female (84.55%, n = 487), with a mean age of M = 20.46 years (SD = 2.76). The majority of participants (42.19%) identified their most traumatic experience as occurring within the past year, 31.42% between 1 and 5 years ago, 14.76% between 5 and 10 years ago, and 11.63% as occurring > 10 years ago. Household income converted to USD per annum was as follows: < 1450 (‘lower’; 18.23%), 1450–23,190 (‘middle’; 54.51%), and > 23,190 (‘upper’; 27.26%). Therefore, most participants lived in households that earned considerably less than the estimated US median household income (63,179 USD per annum; Semega, Kollar, Creamer, & Mohanty, 2019).

Power analyses appropriate to this study’s latent class analysis (LCA) and to non-parametric tests determined that this N is sufficient to achieve a power of at least 0.8 with Cohen’s w = 0.3 (Dziak, Lanza, & Tan, 2014; Wurpts & Geiser, 2014).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. International Trauma Questionnaire

The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) is a 12-item self-report measure that focuses on the core features of PTSD and CPTSD, as they have been formulated in the ICD-11 (Cloitre et al., 2018).

After describing the index trauma as the most troubling personal life event, individuals complete six items that measure three clusters of PTSD symptoms: re-experiencing, avoidance, and sense of threat. Six further items measure three clusters of DSO symptoms: affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbances in relationships. In addition, individuals rate their functional impairment associated with PTSD symptoms and DSO symptoms (three items each), as reported in the last month. All items are scored on a five-point scale, from ‘not at all applicable’ (0) to ‘extremely applicable’ (4), and endorsement of a symptom requires a score of at least 2. Meeting criteria for PTSD requires endorsement of at least one symptom for each of the three PTSD symptom clusters, and endorsement of at least one symptom of functional impairment associated with PTSD symptoms. Meeting criteria for DSO requires endorsement of at least one symptom for each of the three DSO symptom clusters, and endorsement of at least one symptom of functional impairment associated with DSO symptoms. PTSD is diagnosed if criteria are met for PTSD and not for DSO, whereas CPTSD is diagnosed if criteria are met for both PTSD and DSO. These symptom profiles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) symptom profiles, and corresponding items in the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ)

| Symptom profiles |

||

|---|---|---|

| ICD-11 PTSD | ICD-11 CPTSD | Items in the ITQ |

| PTSD symptoms | PTSD symptoms | |

| Re-experiencing | Re-experiencing | |

| Dreams | Dreams | Having upsetting dreams that replay part of the experience or are clearly related to the experience |

| Flashbacks | Flashbacks | Having powerful images or memories that sometimes come into your mind in which you feel the experience is happening again in the here and now |

| Avoidance | Avoidance | |

| Thoughts | Thoughts | Avoiding internal reminders of the experience (for example, thoughts, feelings, or physical sensations) |

| Behaviour | Behaviour | Avoiding external reminders of the experience (for example, people, places, conversations, objects, activities, or situations) |

| Sense of threat | Sense of threat | |

| Hypervigilance | Hypervigilance | Being ‘super-alert’, watchful, or on guard |

| Startle | Startle | Feeling jumpy or easily startled |

| DSO symptoms | ||

| Affective dysregulation | ||

| Hyperactivation | When I am upset, it takes me a long time to calm down | |

| Hypoactivation | I feel numb or emotionally shut down. | |

| Negative self-concept | ||

| Guilty | I feel like a failure | |

| Worthless | I feel worthless | |

| Disturbances in relationships | ||

| Distant | I feel distant or cut off from people | |

| Detached | I find it hard to stay emotionally close to people | |

ICD-11, 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases.

The ITQ has shown good psychometric properties in previous studies (Ben-Ezra et al., 2018; Hyland et al., 2018; Knefel et al., 2020). In the current sample, the internal consistencies of the PTSD subscale (α = .83), the DSO subscale (α = .88), and the total scale (α = .90) were satisfactory.

2.2.2. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) is a 28-item self-report measure for identifying history of abuse and neglect during childhood in both clinical and non-clinical populations (Bernstein et al., 2003). All items are scored on a five-point scale ranging from ‘never true’ (1) to ‘very often true’ (5). Total scores can be summed to reflect a quantitative index of childhood trauma; however, the CTQ also has five subscales, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, as well as emotional and physical neglect. CTQ-related cut-off scores for each subscale produce levels of trauma severity, ranging from ‘none/minimal’ to ‘low’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’. In this study, severity indices were calculated by averaging raw scores for abuse and neglect and for each subscale. Binary variables were calculated to indicate subscale endorsement, where ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ subscale severity was considered to reflect endorsement of that subscale.

The CTQ also includes three additional items to measure minimization/denial of childhood trauma. Scores for these items were dichotomized as ‘very often true’ (1) and all other responses (0), and summed. A maximum score of 3 for minimization/denial and extremely low severity for all subscales was considered to indicate extreme minimization/denial.

Assessment of the CTQ has confirmed a five-factor model and has shown good psychometric properties in community samples (Kim, Bae, Han, Oh, & MacDonald, 2013; Lochner et al., 2011). In the current sample, the total CTQ scale (α = .82) and four of the five main subscales (α = .77–.91) showed satisfactory internal consistency.

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Latent class analysis

We chose to use LCA because latent variable modelling is well suited to evaluate construct validity (Oberski, 2016) and because this statistical method is commonly used to investigate the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD (Brewin et al., 2017).

Items from the ITQ were coded as 12 binary categorical variables in the LCA: six items representing PTSD symptoms and six items representing DSO symptoms. A general practice in LCA is to fit models with a successively increasing number of classes (Brewin et al., 2017; Oberski, 2016). Therefore, models with two to six classes were estimated using robust maximum likelihood and assessed for optimal fit. Selection of the best-fitting model was informed by a combination of parsimony and information criterion indices, including the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the sample-size adjusted BIC (SSA-BIC), and the Akaike information criterion (AIC), where lower values for each indicate better fit. The Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-A) and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) were further used to compare models, where those with non-significant p-values generally indicate better fit for models with one less class. For the estimation of each model, 400 initial random starting values and 50 final stage optimizations were used. For BLRT values, 50 bootstrap draws were used.

Although no explicit standard exists for selecting a class solution as the best-fitting model, evidence from a widely referenced simulation study investigating the performance of the above-mentioned fit indices indicated that the BIC outperformed the other information criterion indices and that the BLRT outperformed the LMR-A (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). Therefore, the BIC and BLRT were considered more definitive than alternative indices for model selection.

Estimation and comparison of models with graphical representations were conducted in R version 3.5.3. Calculation of fit indices and likelihood ratio tests was conducted in MPLUS version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

2.3.2. Between-class differences in sociodemographic variables, diagnostic variables, symptom variables, and childhood trauma

Classes were evaluated for significant differences in sociodemographic variables (age, sex, and household income), rates of probable PTSD and CPTSD diagnostic endorsements, rates of PTSD and DSO symptom endorsements, severity of childhood trauma (abuse and neglect), severity of childhood trauma subscales (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect), and rates of childhood trauma subscale endorsements. Chi-squared tests of independence were conducted for categorical variables, following the precedent set by several CPTSD studies (Cloitre, Garvert, Weiss, Carlson, & Bryant, 2014; Frost, Hyland, Shevlin, & Murphy, 2020; Karatzias et al., 2017), and Kruskal–Wallis H tests were conducted for continuous variables, as assumptions of normality and homogeneous error variance across classes were violated. Where significant between-class differences warranted post-hoc comparisons, results were reported at the α = .05 level with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction. Effect sizes were interpreted according to guidelines presented by Cohen (1988). SPSS version 25 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics

Of the total sample, 14.93% (n = 86) of participants met diagnostic criteria for PTSD and 11.46% (n = 66) met diagnostic criteria for CPTSD. The most severe subscale of childhood trauma was emotional neglect (M = 1.95, SD = 0.84), followed by emotional abuse (M = 1.90, SD = 0.87), physical neglect (M = 1.42, SD = 0.54), physical abuse (M = 1.39, SD = 0.58), and sexual abuse (M = 1.35, SD = 0.81). The majority of the sample (59.55%, n = 343) showed low endorsement of childhood trauma, whereas 18.58% (n = 107) endorsed one subscale, 10.34% (n = 63) endorsed two subscales, 6.08% (n = 35) endorsed three subscales, and 4.86% (n = 28) endorsed four or more subscales.

3.2. Latent class analysis

Table 2 shows the fit indices calculated for the models estimated in the LCA. The SSA-BIC and the AIC did not converge on any class solution and were therefore considered unreliable indices for these data. The LMR-A, BIC, and BLRT indicated three-, four-, and five-class solutions, respectively. However, given the priority we afforded to the BIC and BLRT over the other indices, we considered only the four- and five-class solutions. We selected the four-class solution for three reasons: (a) this model was more theoretically interpretable, (b) it showed superior class separation (entropy = .784), and (c) the evidence of better fit for the four- versus three-class solution was very strong (Raferty, 1999; ΔBIC > 10) and greater than that for the five- versus four-class solution (ΔBIC < 4).

Table 2.

Fit indices for latent class solutions

| Model | Log-likelihood | BIC | SSA-BIC | AIC | LMR-A p | BLRT p | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 classes | −4117.42 | 8383.74 | 8314.37 | 8284.84 | < .001 | < .001 | .796 |

| 3 classes | −4002.61 | 8246.75 | 8126.12 | 8081.22 | .044 | < .001 | .773 |

| 4 classes | −3926.35 | 8176.86 | 8014.95 | 7954.70 | .280 | .001 | .784 |

| 5 classes | −3886.55 | 8179.89 | 7976.72 | 7901.01 | .937 | < .001 | .777 |

| 6 classes | −3860.20 | 8209.83 | 7965.39 | 7874.41 | .310 | .140 | .783 |

Selected model in bold.

BIC, Bayesian information criterion; SSA-BIC, sample-size adjusted BIC; AIC, Akaike information criterion; LMR-A, Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test; BLRT, bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

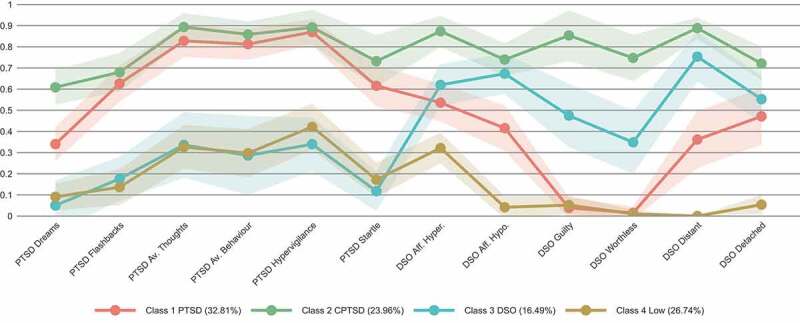

The profile plot of symptom endorsement probabilities for the four classes is shown in Figure 1. Descriptive labels for each class were determined by assessing the patterns of endorsement probabilities for all 12 symptoms. Class 1 showed high probabilities of endorsing all PTSD symptoms (except for PTSD Dreams, which showed low probability) and low-to-moderate probability of endorsing all DSO symptoms. Class 1 was thus labelled the ‘PTSD class’. Class 2 showed high endorsement probabilities for all PTSD and DSO symptoms and was thus labelled the ‘CPTSD class’. Endorsement probabilities for class 3 were low for PTSD symptoms and moderate to high for DSO symptoms, and it was therefore labelled the ‘DSO class’. Class 4 showed low endorsement probabilities for all symptoms and was thus labelled the ‘Low class’.

Figure 1.

Estimated class-conditional response probabilities for the four-class model. The 95% confidence interval is shown by the ribbon range. Sample proportions are shown in parentheses. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CPTSD, complex post-traumatic stress disorder; DSO, disturbances in self-organization; Av., avoidance; Aff., affective dysregulation; Hyper., hyperactivation; Hypo., hypoactivation

Average probabilities for most likely class membership were acceptable, with 86.00% for the PTSD class, 93.60% for the CPTSD class, 84.90% for the DSO class, and 87.90% for the Low class. These figures indicate moderate- to high-quality indicator variables (Wurpts & Geiser, 2014). The model showed no classes with a disproportionately low number of participants. The proportions of individuals fitted into each class were 32.81% (n = 189) for the PTSD class, 23.96% (n = 138) for the CPTSD class, 16.49% (n = 95) for the DSO class, and 26.74% (n = 154) for the Low class.

3.3. Between-class differences in sociodemographic variables

Results are shown in Table 3. Analyses indicated that classes did not differ significantly by age. Significant differences in sex were detected between classes and post-hoc tests indicated that the proportion of females to males was significantly larger in the PTSD class compared to the Low class, χ2(1, N = 343) = 8.45, p = .022, V = .157. The four classes did not differ significantly by categories of household income.

Table 3.

Between-class differences in sociodemographic variables (N = 576)

| Class 1 PTSD | Class 2 CPTSD | Class 3 DSO | Class 4 Low | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable |

(n = 189) |

(n = 138) |

(n = 95) |

(n = 154) |

H/χ2 |

df |

p |

ESE |

| Age | 20.37 (2.15) | 20.20 (2.33) | 21.18 (3.96) | 20.34 (2.79) | 7.79 | 3 | .051 | .014 |

| Sex | 13.12 | 3 | .004** | .151 | ||||

| Female | 169 (0.89) | 123 (0.89) | 75 (0.79) | 120 (0.78) | ||||

| Male | 20 (0.11) | 15 (0.11) | 20 (0.19) | 34 (0.22) | ||||

| Household income | 6.71 | 6 | .349 | .076 | ||||

| Lower | 45 (0.24) | 20 (0.15) | 17 (0.18) | 23 (0.15) | ||||

| Middle | 96 (0.51) | 81 (0.59) | 51 (0.54) | 86 (0.56) | ||||

| Upper | 48 (0.25) | 37 (0.27) | 27 (0.28) | 45 (0.29) |

For Age, means are presented with standard deviations in parentheses. For Sex and Household income, raw numbers are presented with column percentages in parentheses.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CPTSD, complex post-traumatic stress disorder; DSO, disturbances in self-organization; ESE, effect size estimate.

ESE was calculated using epsilon squared (ε2) for Kruskal–Wallis H tests and Cramer’s V for chi-squared tests of independence.

**p < .01.

3.4. Between-class differences in diagnostic and symptom variables

Chi-squared tests of independence were conducted to assess between-class differences in rates of probable PTSD and CPTSD diagnostic endorsements and rates of PTSD and DSO symptom endorsements, corresponding directly to endorsement probabilities shown in Figure 1. All tests were significant (p < .001). Results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Between-class differences in diagnostic and symptom variables (N = 576)

| Class 1 PTSD |

Class 2 CPTSD |

Class 3 DSO |

Class 4 Low |

||||

| Variable |

(n = 189) |

(n = 138) |

(n = 95) |

(n = 154) |

χ2 |

ESE |

Significant post-hoc comparisons |

| ICD-11 PTSD | 67 (0.35) | 18 (0.13) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 0.01) | 104.44 | .426 | 1 > 2, 3, 4 2 > 3, 4 |

| ICD-11 CPTSD | 0 (0) | 66 (0.48) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 236.59 | .641 | 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| PTSD symptoms | |||||||

| Dreams | 70 (0.37) | 85 (0.62) | 3 (0.03) | 12 (0.08) | 140.06 | .493 | 1 > 3, 4 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| Flashbacks | 126 (0.67) | 93 (0.67) | 16 (0.17) | 18 (0.12) | 163.81 | .533 | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| Av. Thoughts | 161 (0.85) | 124 (0.90) | 30 (0.32) | 50 (0.32) | 185.17 | .567 | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| Av. Behaviour | 156 (0.83) | 118 (0.86) | 26 (0.27) | 48 (0.31) | 173.48 | .549 | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| Hypervigilance | 168 (0.89) | 123 (0.89) | 30 (0.32) | 66 (0.43) | 166.51 | .538 | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| Startle | 119 (0.63) | 103 (0.75) | 10 (0.11) | 26 (0.17) | 168.56 | .541 | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| DSO symptoms | |||||||

| Aff. Hyper. | 105 (0.56) | 120 (0.87) | 58 (0.61) | 51 (0.33) | 87.46 | .390 | 1, 3 > 4 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| Aff. Hypo. | 86 (0.46) | 100 (0.72) | 65 (0.68) | 5 (0.03) | 171.94 | .546 | 1 > 4 2, 3 > 1, 4 |

| Guilty | 4 (0.02) | 125 (0.91) | 47 (0.49) | 8 (0.05) | 359.71 | .790 | 2, 3 > 1 2 > 3, 4 3 > 4 |

| Worthless | 2 (0.01) | 109 (0.79) | 34 (0.36) | 1 (0.01) | 323.87 | .750 | 2, 3 > 1 2 > 3, 4 3 > 4 |

| Distant | 71 (0.38) | 122 (0.88) | 76 (0.80) | 0 (0) | 280.02 | .697 | 1, 2, 3 > 4 2, 3 > 1 |

| Detached | 95 (0.50) | 98 (0.71) | 53 (0.56) | 8 (0.05) | 143.29 | .499 | 1, 2, 3 > 4 2 > 1 |

Raw numbers are presented with column percentages in parentheses.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CPTSD, complex post-traumatic stress disorder; DSO, disturbances in self-organization; ESE, effect size estimate; ICD-11, 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases; Av., avoidance; Aff., affective dysregulation; Hyper., hyperactivation; Hypo., hypoactivation.

ESE was calculated using Cramer’s V for chi-squared tests of independence. For all tests, df = 3 and p < .001. For Significant post-hoc comparisons, numbers represent class labels. Bonferroni correction was used for all comparisons.

The classes differed significantly on diagnostic endorsements for PTSD and CPTSD. PTSD diagnosis was significantly more frequent in the PTSD class relative to the CPTSD class, χ2(1, N = 327) = 20.82, p < .001, V = .252. Conversely, CPTSD diagnosis was significantly more frequent in the CPTSD class relative to the PTSD class, χ2(1, N = 327) = 113.25, p < .001, V = .588. These differences represent large effect sizes.

Of participants in the entire sample who endorsed the PTSD diagnosis, 77.90% (n = 67) were in the PTSD class, and of those in the entire sample who endorsed CPTSD, 100% (n = 66) were in the CPTSD class. The DSO class had no participants who endorsed either PTSD or CPTSD and the Low class contained one participant who endorsed PTSD.

Table 4 indicates that the classes differed significantly for all PTSD and DSO symptoms. With the exception of one PTSD symptom [PTSD Dreams; χ2(1, N = 327) = 19.29, p < .001, V = .243], the PTSD and CPTSD classes showed no significant differences in rates of PTSD symptom endorsements between each other, and both showed significantly higher rates of PTSD symptom endorsements relative to the DSO and Low classes. Endorsement rates for all DSO symptoms were significantly higher in the CPTSD class relative to the PTSD class. Effect sizes for all comparisons were large. These relative differences in symptom endorsement rates therefore indicate significantly higher PTSD symptomology associated with both the PTSD and CPTSD classes relative to the other classes, and significantly different DSO symptomology associations between each other: lower for the PTSD class and higher for the CPTSD class. These results therefore indicate a significant distinction between PTSD and CPTSD symptom profiles.

3.5. Between-class differences in childhood trauma variables

Chi-squared tests of independence and Kruskal–Wallis H tests were conducted to assess between-class differences in severity of childhood trauma, severity of childhood trauma subscales, and rates of subscale endorsements. Results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Between-class differences in childhood trauma variables (N = 543)a.

| Class 1 PTSD |

Class 2 CPTSD |

Class 3 DSO |

Class 4 Low |

||||||

| Variable |

(n = 181) |

(n = 135) |

(n = 93) |

(n = 134) |

H/χ2 |

df |

p |

ESE |

Significant post-hoc comparisons |

| CTQ severity | |||||||||

| Abuse | 1.59 (0.57) | 1.82 (0.69) | 1.58 (0.53) | 1.30 (0.29) | 58.24 | 3 | < .001*** | .107 | 2 > 1 1, 2, 3 > 4 |

| Neglect | 1.70 (0.62) | 1.91 (0.66) | 1.85 (0.60) | 1.48 (0.52) | 46.28 | 3 | < .001*** | .085 | 2 > 1 1, 2, 3 > 4 |

| CTQ subscale severity | |||||||||

| Emotional abuse | 1.94 (0.88) | 2.30 (0.97) | 2.01 (0.86) | 1.51 (0.50) | 57.38 | 3 | < .001*** | .106 | 2 > 1 1, 2, 3 > 4 |

| Physical abuse | 1.42 (0.61) | 1.56 (0.78) | 1.40 (0.51) | 1.25 (0.32) | 10.40 | 3 | .015* | .019 | 2 > 4 |

| Sexual abuse | 1.40 (0.88) | 1.61 (1.04) | 1.29 (0.70) | 1.13 (0.42) | 26.67 | 3 | < .001*** | .049 | 2 > 3 1, 2 > 4 |

| Emotional neglect | 1.94 (0.80) | 2.27 (0.84) | 2.50 (0.87) | 1.67 (0.72) | 53.02 | 3 | < .001*** | .098 | 1, 2, 3 > 4 2, 3 > 1 |

| Physical neglect | 1.47 (0.56) | 1.56 (0.63) | 1.44 (0.48) | 1.30 (0.42) | 15.77 | 3 | .001** | .029 | 1, 2 > 4 |

| CTQ subscale endorsement | 53.51 | 12 | < .001*** | .181 | |||||

| None | 101 (0.56) | 54 (0.40) | 51 (0.55) | 104 (0.78) | 1 > 2 4 > 1, 2, 3 |

||||

| 1 | 34 (0.19) | 38 (0.28) | 16 (0.17) | 19 (0.14) | 2 > 4 | ||||

| 2 | 27 (0.15) | 16 (0.12) | 12 (0.13) | 8 (0.06) | |||||

| 3 | 11 (0.06) | 12 (0.09) | 10 (0.11) | 2 (0.02) | 2, 3 > 4 | ||||

| ≥ 4 | 8 (0.04) | 15 (0.11) | 4 (0.04) | 1 (< 0.01) | 2 > 4 |

For CTQ severity and CTQ subscale severity, means are presented with standard deviations in parentheses. For CTQ subscale endorsement, raw numbers are presented with column percentages in parentheses.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CPTSD, complex post-traumatic stress disorder; DSO, disturbances in self-organization; ESE, effect size estimate; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

ESE was calculated using epsilon squared (ε2) for Kruskal–Wallis H tests and Cramer’s V for chi-squared tests of independence. For Significant post-hoc comparisons, numbers represent class labels. Bonferroni correction was used for all comparisons.

an = 33 participants were excluded for extreme minimization/denial.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Regarding overall scores for abuse and neglect, there were significant between-class differences. Mann–Whitney U post-hoc tests revealed that mean rank scores for the CPTSD class (178.23 for abuse; 177.49 for neglect) were significantly higher than those for the PTSD class (143.78 for abuse; 144.34 for neglect) for both abuse (U = 14,881.50, z = 3.321, p = .005, r = .187) and neglect (U = 14,781, z = 3.197, p = .008, r = .180). The effects for these post-hoc differences were small. The Low class had significantly lower scores than all other classes.

Regarding CTQ subscales, mean rank scores were significantly higher in the CPTSD class (179.51 for emotional abuse; 179.62 for emotional neglect) than in the PTSD class (142.83 for emotional abuse; 142.75 for emotional neglect) for two of the five subscales: emotional abuse (U = 15,054, z = 3.543, p = .002, r = .199) and emotional neglect (U = 15,069, z = 3.562, p = .002, r = .200). These post-hoc differences had small effect sizes. The Low class had significantly lower scores compared to all other classes for emotional abuse and emotional neglect, to the PTSD and CPTSD classes for sexual abuse and physical neglect, and to the CPTSD class for physical abuse. These post-hoc differences represent small to medium effect sizes, with the largest effects seen for emotional abuse and emotional neglect.

Finally, the classes differed significantly in terms of CTQ subscale endorsement rates, for all possible subscale quantities except for the endorsement of two subscales. Compared to the PTSD class, the CPTSD class contained significantly fewer participants who did not endorse any subscale, χ2(1, N = 316) = 7.72, p = .033, V = .156. This difference represents a medium effect size. The Low class consistently endorsed significantly fewer subscales of childhood trauma compared to the other classes.

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD was valid in an LMIC sample of university undergraduates. Our analyses revealed that a CPTSD class was distinct from a PTSD class, with acceptable discrimination between classes. The assessment of childhood trauma characteristics showed that, compared to the PTSD class, the CPTSD class was associated with more severe trauma, specifically emotional abuse and neglect.

Furthermore, the symptoms of nearly a quarter of our sample were estimated to resemble a CPTSD diagnostic profile (i.e. full or subthreshold), and those of approximately a third of the sample to resemble a PTSD diagnostic profile. Considering that analyses showed that these syndromes represent mutually exclusive populations and that their proportions in the sample were relatively comparable, CPTSD should be given similar clinical consideration.

Our first hypothesis stated that a latent class with a CPTSD symptom profile would be distinct from one with a PTSD symptom profile. High endorsement of PTSD symptoms and low endorsement of DSO symptoms were hypothesized to correspond to a PTSD class, whereas high endorsement of both was hypothesized to correspond to a CPTSD class. Significant relative differences in the patterns of symptom endorsement between the PTSD and CPTSD classes were thus consistent with the first hypothesis and support the validity of the ITQ measure in terms of ICD-11 criteria. Our findings contrast with research showing that differences between PTSD and CPTSD are related to symptom severity only, with CPTSD representing a more severe form of PTSD (Wolf et al., 2015). These findings are also consistent with those of several previous studies (Barbieri et al., 2019; Hyland et al., 2018; Karatzias et al., 2017; Kazlauskas et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2016).

Surprisingly, our data supported the emergence of another distinct class, namely a DSO class. Most previous studies have not found evidence of this class (Barbieri et al., 2019; Hyland et al., 2018; Jowett et al., 2019; Karatzias et al., 2017; Kazlauskas et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2016). However, Kazlauskas et al. (2020) also reported a DSO class in their study examining the validity of PTSD and CPTSD in adolescents, albeit with an adapted version of the ITQ best suited to their sample. They noted that the DSO class may represent individuals who are experiencing symptoms that overlap with those from other psychiatric disorders (e.g. symptoms of feeling worthless and emotionally dysregulated, related to depressive disorders). Another study, by Cloitre et al. (2014), also reported similar results. Our findings dovetail with those of Kazlauskas et al. (2020) because of some similarities in our recruited sample. Although we did not recruit adolescents, our sample consisted of young adults (Mdn = 20 years) who would have been facing significant life changes and instability. For example, university students are widely reported to experience greater emotional dysregulation and instability in their relationships and self-concept compared to middle-aged or older adults (Meier, Orth, Denissen, & Kühnel, 2011; Monteiro, Balogun, & Oratile, 2014; Orgeta, 2009).

This study’s second hypothesis stated that significant differences in childhood trauma would distinguish between PTSD and CPTSD. Specifically, we hypothesized that a CPTSD class would demonstrate significantly more severe childhood trauma and significantly more types of childhood trauma exposure. Our findings supported this hypothesis in part. Regarding trauma severity, participants in the CPTSD class had higher childhood abuse and neglect severity scores than participants in the PTSD class. Specifically, an analysis of the CTQ subscales revealed that associations with emotional abuse and neglect are significantly different between PTSD and CPTSD syndromes. This finding highlights the importance of interpersonal trauma in the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD. It is also consistent with findings reported by Karatzias et al. (2017), who similarly found significantly greater emotional abuse and emotional neglect associated with CPTSD compared to PTSD, albeit with larger effects than those found in our sample. There were, however, no significant differences between PTSD and CPTSD classes in our sample for one to four or more types of childhood trauma exposure. The CPTSD class did, nonetheless, have significantly fewer participants who reported no childhood trauma exposure, compared to the PTSD class.

In our LMIC context, these findings suggest that what carries more weight in determining a CPTSD pattern of symptoms may not be a greater number of trauma types in childhood, but rather the severity of childhood trauma experience. In South Africa, the overall prevalence of childhood trauma is extremely high (Artz et al., 2016; Hsiao et al., 2018). For example, a report describing rape cases in 2012 in South Africa showed that 46% of all reported rapes were paediatric (Machisa et al., 2017). Speculatively, in an environment where so many children are exposed to trauma, and where this experience is somewhat normalized (Artz et al., 2016; Kaminer & Eagle, 2010), severe cases of abuse and neglect may be more likely to result in complex trauma. Our findings are largely consistent with a substantial body of literature detailing the long-term harmful effects of prolonged interpersonal trauma in childhood on psychiatric outcomes (Karatzias et al., 2017; Roth, Newman, Pelcovitz, van der Kolk, & Mandel, 1997).

Together, these results indicate that CPTSD is distinct from PTSD in both its symptom profile and severity of childhood trauma experience. Notably, the majority of previous data supporting the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD has originated in HICs. Our study is one of a handful of studies that (a) use an LMIC sample and (b) are consistent with the findings of studies with HIC samples regarding the validity of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD constructs. This is relevant, because LMIC samples are significantly under-researched in the literature and trauma exposure is typically higher in LMICs compared to HICs, suggesting that many LMICs stand to benefit from refining the clinical profile associated with trauma.

Notably, approximately 15% of our sample fully satisfied diagnostic criteria for ICD-11 PTSD and approximately 11% satisfied those for ICD-11 CPTSD. Both these proportions are extremely high given commonly reported prevalence rates (2.3%; Atwoli et al., 2013). Although some studies have noted a ‘vulnerability paradox’, where low vulnerability countries (typically HICs) have higher conditional PTSD prevalence rates and high vulnerability countries (typically LMICs) show the opposite pattern, our data are not consistent with this observed trend. That is, our PTSD and CPTSD prevalence rates are high, despite the fact that our sample is drawn from an LMIC context with individuals drawing predominantly low- and middle-level earnings. However, this study was conducted during a time of significant and ongoing political unrest at our university campus, which included violence and civil disobedience (Brits et al., 2019; Konik & Konik, 2018).

Another emergent implication of the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD is the need to develop and test differential treatment methodologies. As a disorder characterized by trauma symptomology and DSO, CPTSD warrants modalities of treatment focused on the amelioration of symptoms consistent with DSO, rather than sole focus on the reprocessing and rescripting of traumatic memory (Cloitre et al., 2014).

We note a number of limitations. First, the sample consisted of university undergraduates recruited via convenience sampling. As such, this sample is not representative of the general population. However, since our study was conducted during a time when trauma exposure was elevated, the context was appropriate for research of this nature. Secondly, the data we used in this study were cross-sectional and based on self-administered questionnaires rather than structured clinical interviews. Our data therefore cannot be used to determine causal effects and they are subject to reporting bias inherent to this data collection method.

5. Conclusion

Our study supports the distinction made in the ICD-11 between PTSD and CPTSD. Furthermore, the data highlight that CPTSD is associated with more severe childhood abuse and neglect than PTSD. We show consistency between HICs and LMICs regarding the validity of CPTSD, which is relevant because in LMICs trauma exposure is higher and often more severe than in HICs, resulting in large numbers of individuals who are vulnerable to either one of these disorders. Our findings also indicate a comparable proportion of individuals assigned to the PTSD and CPTSD classes, emphasizing the relevance of the CPTSD diagnosis. Furthermore, the most significant contribution that a unique CPTSD classification is likely to make to patient care is a change in treatment emphasis, from sole focus on the reprocessing and rescripting of traumatic memory to the incorporation of therapies aimed at the amelioration of symptoms consistent with DSO.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation. The funding agency had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the article; nor in the decision to submit it for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical approval

Full ethical approval was obtained from the relevant bodies at the hosting institution, and the research met the standards described in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework repository at http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3FR4A.

References

- Artz, L., Burton, P., Ward, C. L., Leoschut, L., Phyfer, J., Lloyd, S., & Le Mottee, C. (2016). Sexual victimisation of children in South Africa, final report of the Optimus Foundation Study: South Africa [Report] (pp. 1–12). UBS Optimus Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.cjcp.org.za/uploads/2/7/8/4/27845461/08_cjcp_report_2016_d.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Atwoli, L., Stein, D. J., Williams, D. R., Mclaughlin, K. A., Petukhova, M., Kessler, R. C., & Koenen, K. C. (2013). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in South Africa: Analysis from the South African stress and health study. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, A., Visco-Comandini, F., Fegatelli, D. A., Schepisi, C., Russo, V., Calò, F., … Stellacci, A. (2019). Complex trauma, PTSD and complex PTSD in African refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1700621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ezra, M., Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Maercker, A., Hamama-Raz, Y., Lavenda, O., … Shevlin, M. (2020). A cross-country psychiatric screening of ICD-11 disorders specifically associated with stress in Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1720972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ezra, M., Karatzias, T., Hyland, P., Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Bisson, J. I., … Shevlin, M. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD) as per ICD-11 proposals: A population study in Israel. Depression and Anxiety, 35(3), 264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., … Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Maercker, A., Bryant, R. A., … Reed, G. M. (2017). A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brits, H., Joubert, G., Lomberg, L., Djan, P., Makoro, G., Mokoena, M., … Tengu, D. (2019). #FeesMustFall2016: Perceived and measured effect on clinical medical students. South African Medical Journal, 109(7), 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Weiss, B., Carlson, E. B., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Maercker, A., … Hyland, P. (2018). The international trauma questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 536–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J., Forster, T., Himmelsbach, J., Korte, L., Mucke, P., Radtke, K., … Weller, D. (2019). World risk report 2019 [Report] (pp. 1–65). Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/WorldRiskReport-2019_Online_english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dokkedahl, S., Ovuga, E., & Elklit, A. (2015). ICD-11 trauma questionnaires for PTSD and complex PTSD: Validation among civilians and former abducted children in Northern Uganda. Journal of Psychiatry, 18, 1000335. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington, S., Zavos, H., Ball, H., McGuffin, P., Rijsdijk, F., Siribaddana, S., … Hotopf, M. (2014). Trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder and psychiatric disorders in a middle-income setting: Prevalence and comorbidity. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(5), 383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dückers, M. L. A., Alisic, E., & Brewin, C. R. (2016). A vulnerability paradox in the cross-national prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak, J. J., Lanza, S. T., & Tan, X. (2014). Effect size, statistical power, and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 534–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R., Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., & Murphy, J. (2020). Distinguishing complex PTSD from borderline personality disorder among individuals with a history of sexual trauma: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4(1), 100080. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbar, O. (2020). Examining the boundaries between ICD-11 PTSD/CPTSD and depression and anxiety symptoms: A network analysis perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders, 262, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, J. (2012). CPTSD is a distinct entity: Comment on Resick et al. (2012). Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 256–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, G. W. K., Bressington, D., Karatzias, T., Chien, W. T., Inoue, S., Yang, P. J., … Hyland, P. (2020). Patterns of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and their associations with mental health: A survey of 1346 university students in East Asia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(3), 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, C., Fry, D., Ward, C. L., Ganz, G., Casey, T., Zheng, X., & Fang, X. (2018). Violence against children in South Africa: The cost of inaction to society and the economy. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, P., Ceannt, R., Daccache, F., Abou Daher, R., Sleiman, J., Gilmore, B., … Vallières, F. (2018). Are posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex-PTSD distinguishable within a treatment-seeking sample of Syrian refugees living in Lebanon? Global Mental Health, 5, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, P., Murphy, J., Shevlin, M., Vallières, F., McElroy, E., Elklit, A., … Cloitre, M. (2017). Variation in post-traumatic response: The role of trauma type in predicting ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD symptoms. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Downes, A. J., Jumbe, S., … Roberts, N. P. (2017). Validation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD using the international trauma questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 136(3), 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett, S., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., & Albert, I. (2019). Differentiating symptom profiles of ICD-11 PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis in a multiply traumatized sample. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 36–45. doi: 10.1037/per0000346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer, D., & Eagle, G. (2010). Traumatic stress in South Africa. Wits University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oapen.org/record/626383 [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer, D., Eagle, G., & Crawford-Browne, S. (2018). Continuous traumatic stress as a mental and physical health challenge: Case studies from South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(8), 1038–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., Hyland, P., Efthymiadou, E., Wilson, D., … Cloitre, M. (2016). An initial psychometric assessment of an ICD-11 based measure of PTSD and complex PTSD (ICD-TQ): Evidence of construct validity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 44, 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., Hyland, P., Efthymiadou, E., Wilson, D., … Cloitre, M. (2017). Evidence of distinct profiles of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) based on the new ICD-11 trauma questionnaire (ICD-TQ). Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas, E., Gegieckaite, G., Hyland, P., Zelviene, P., & Cloitre, M. (2018). The structure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in Lithuanian mental health services. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1414559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas, E., Zelviene, P., Daniunaite, I., Hyland, P., Kvedaraite, M., Shevlin, M., & Cloitre, M. (2020). The structure of ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD in adolescents exposed to potentially traumatic experiences. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D., Bae, H., Han, C., Oh, H. Y., & MacDonald, K. (2013). Psychometric properties of the childhood trauma questionnaire-short form (CTQ-SF) in Korean patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 144(1–3), 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knefel, M., Karatzias, T., Ben-Ezra, M., Cloitre, M., Lueger-Schuster, B., & Maercker, A. (2019). The replicability of ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress disorder symptom networks in adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 214(6), 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knefel, M., Lueger‐Schuster, B., Bisson, J., Karatzias, T., Kazlauskas, E., & Roberts, N. P. (2020). A cross-cultural comparison of ICD-11 complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptom networks in Austria, the UK, and Lithuania. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(1), 41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knefel, M., Tran, U. S., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2016). The association of posttraumatic stress disorder, complex posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder from a network analytical perspective. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konik, I., & Konik, A. (2018). The #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall student protests through the Kübler-Ross grief model. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(4), 575–589. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner, C., Seedat, S., Allgulander, C., Kidd, M., Stein, D., & Gerdner, A. (2011). Childhood trauma in adults with social anxiety disorder and panic disorder: A cross-national study. African Journal of Psychiatry, 13(5), 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machisa, M., Jina, R., Labuschagne, G., Vetten, L., Loots, L., Swemmer, S., … Jewkes, R. (2017). Rape justice in South Africa: A retrospective study of the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of reported rape cases from 2012 [Report]. Gender and Health Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council. Retreived from https://www.samrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/files/2017-10-30/RAPSSAreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- McElroy, E., Shevlin, M., Murphy, S., Roberts, B., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., … Hyland, P. (2019). ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: Structural validation using network analysis. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 236–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, L. L., Orth, U., Denissen, J. J. A., & Kühnel, A. (2011). Age differences in instability, contingency, and level of self-esteem across the life span. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(6), 604–612. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, N. M., Balogun, S. K., & Oratile, K. N. (2014). Managing stress: The influence of gender, age and emotion regulation on coping among university students in Botswana. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 19(2), 153–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D., Shevlin, M., Pearson, E., Greenberg, N., Wessely, S., Busuttil, W., & Karatzias, T. (2020). A validation study of the international trauma questionnaire to assess post-traumatic stress disorder in treatment-seeking veterans. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(3), 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S., Elklit, A., Dokkedahl, S., & Shevlin, M. (2016). Testing the validity of the proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD criteria using a sample from Northern Uganda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 32678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S., Elklit, A., Dokkedahl, S., & Shevlin, M. (2018). Testing competing factor models of the latent structure of post-traumatic stress disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder according to ICD-11. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1457393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/Mplus%20user%20guide%20Ver_7_r6_web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Oberski, D. (2016). Mixture models: Latent profile and latent class analysis. In Robertson J. & Kaptein M. (Eds.), Modern statistical methods for HCI (pp. 275–287). Springer International Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Orgeta, V. (2009). Specificity of age differences in emotion regulation. Aging & Mental Health, 13(6), 818–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owczarek, M., Ben-Ezra, M., Karatzias, T., Hyland, P., Vallieres, F., & Shevlin, M. (2020). Testing the factor structure of the international trauma questionnaire (ITQ) in African community samples from Kenya, Ghana, and Nigeria. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(4), 348–363. [Google Scholar]

- Raferty, A. E. (1999). Bayes factors and BIC: Comment on “A critique of the Bayesian information criterion for model selection”. Sociological Methods & Research, 27(3), 411–427. [Google Scholar]

- Resick, P. A., Bovin, M. J., Calloway, A. L., Dick, A. M., King, M. W., Mitchell, K. S., … Wolf, E. J. (2012). A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: Implications for DSM-5. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, J., Rodrigues, V., Santos, E., Azevedo, I., Machado, S., Almeida, V., … Cloitre, M. (2019). The first instrument for complex PTSD assessment: Psychometric properties of the ICD-11 trauma questionnaire. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 1–5. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, S., Newman, E., Pelcovitz, D., van der Kolk, B., & Mandel, F. S. (1997). Complex PTSD in victims exposed to sexual and physical abuse: Results from the DSM-IV field trial for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10(4), 539–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semega, J., Kollar, M., Creamer, J., & Mohanty, A. (2019). Income and poverty in the USA: 2018 [Report No. P60-266(RV)] (pp. 1–77). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Vallières, F., Bisson, J., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., … Roberts, B. (2018). A comparison of DSM-5 and ICD-11 PTSD prevalence, comorbidity and disability: An analysis of the Ukrainian internally displaced person’s mental health survey. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 137(2), 138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallières, F., Ceannt, R., Daccache, F., Daher, R. A., Sleiman, J., Gilmore, B., … Hyland, P. (2018). ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD amongst Syrian refugees in Lebanon: The factor structure and the clinical utility of the international trauma questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E. J., Miller, M. W., Kilpatrick, D., Resnick, H. S., Badour, C. L., Marx, B. P., … Friedman, M. J. (2015). ICD–11 complex PTSD in U.S. national and veteran samples: Prevalence and structural associations with PTSD. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(2), 215–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2019). International classification of diseases 11th ed. Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/en [Google Scholar]

- Wurpts, I. C., & Geiser, C. (2014). Is adding more indicators to a latent class analysis beneficial or detrimental? Results of a Monte-Carlo study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(Article), 920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework repository at http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3FR4A.