Abstract

Over 10 years ago, Baer and colleagues proposed the integration of skills training and motivational strategies for the treatment of substance abuse. Since that time, several studies evaluating the efficacy of such hybrid approaches have been published, but few have been efficacious. Motivation and Problem Solving (MAPS) is a comprehensive, dynamic, and holistic intervention that incorporates empirically supported cognitive behavioral and social cognitive theory–based treatment strategies within an overarching motivational framework, and has been demonstrated to be effective in a randomized clinical trial focused on the prevention of postpartum smoking relapse. MAPS was designed to be applicable to not only relapse prevention but also the cessation of substance use, and is relevant for individuals regardless of their motivation to change. MAPS views motivation as dynamically fluctuating from moment to moment throughout the behavior change process, and comprehensively addresses multiple issues important to the individual and relevant to change through the creation of a wellness program. As a result, we believe that MAPS enhances the likelihood that individuals will successfully achieve and maintain abstinence from substance use, and that its comprehensive focus on addressing diverse and salient issues enhances both engagement in treatment and its applicability in modifying other health risk behaviors. The current paper introduces MAPS, distinguishes it from other hybrid and stage-based substance use treatments, and provides detailed information and clinical text regarding how MAPS is specifically and uniquely implemented to address key mechanisms relevant to quitting smoking and maintaining abstinence.

Keywords: motivation, skills training, social cognitive theory, smoking cessation, tobacco dependence

Overview and Rationale for Motivation and Problem Solving

Over 10 years ago, Baer and colleagues (Baer, Kivlahan, & Donovan, 1999) described how treatments for substance abuse could be enhanced by drawing from and integrating skills training and motivational strategies. Despite their call for the integration of two well-defined and empirically supported treatments, relatively little research on the efficacy of such hybrid approaches has been published to date. A notable exception to this is the combined behavioral intervention (CBI) tested in the COMBINE study, which was focused on the treatment of alcohol dependence (Anton et al., 2006). Also, Arkowitz and Westra (2004) have described how therapists may shift into Motivational Interviewing (MI) during the course of another treatment, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), when ambivalence or resistance emerges (Constantino, DeGeorge, Dadlani, & Overtree, 2009). To our knowledge, however, this specific treatment approach has not yet been empirically tested for substance abuse disorders. Other researchers have evaluated treatments that combine skills training and motivational strategies using a stepped approach. That is, one or more initial sessions typically focus solely on increasing motivation whereas subsequent sessions focus exclusively on skills training (Budney, Higgins, Radonovich, & Novy, 2000; Haddock et al., 2003; Kertes, Westra, Angus, & Marcus, 2010; McKee et al., 2007; Westra, Arkowitz, & Dozois, 2009). Others have evaluated somewhat more flexible approaches that integrate CBT-based skills training within the context of MI-based treatment (Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2009) or that shift from MI to CBT and back to MI again if individuals fail to change their behavior or relapse (Stein, Hagerty, Herman, Phipps, & Anderson, 2011; Stein et al., 2006). However, none of these approaches dynamically shift therapeutic strategies on a moment-to-moment basis within a single treatment session, and none are anchored by a formal wellness program intended to guide the course of treatment.

The purpose of the current paper is to describe a new treatment for substance use based on the fluid integration of skills training and motivational enhancement, which follows from and extends previous treatments that have combined skills training with motivational strategies. This hybrid approach, entitled Motivation and Problem Solving (MAPS), focuses heavily on rapid and dynamic shifts between skills training and motivational strategies. Much of the current research on MAPS focuses on tobacco use and dependence. Therefore, tobacco use and dependence is utilized as the target behavior throughout the paper. The paper opens with a broad description of and rationale for MAPS, and then elucidates how MAPS differs conceptually from other prominent hybrid and stage-based treatment approaches. Next, the theoretical basis for MAPS is described, and detailed information is provided regarding how MAPS is specifically and uniquely implemented to addresses three key mechanisms relevant to quitting smoking and maintaining abstinence: motivation, stress and negative affect, and social cognitive constructs (self-efficacy, coping behavior). Each section includes a clinical text scenario intended to illustrate how a counselor trained in MAPS would typically interact with a client to address issues surrounding each mechanism (i.e., motivation, stress and negative affect, and self-efficacy/agency). Finally, a brief overview of the general content of each treatment session is presented. The paper concludes with an overall summary.

Broad Description of MAPS

A comprehensive, dynamic, and holistic approach to facilitating behavior change, MAPS, consistent with the Baer et al. (1999) model, incorporates empirically validated cognitive behavioral and social cognitive theory-based treatment strategies such as coping skills training and practical problem-solving techniques (Fiore et al., 2008) within an overarching motivational framework (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005; Miller & Rollnick, 2002) that addresses multiple issues relevant to considering, initiating, and maintaining behavior change. The motivational framework for MAPS is derived from MI, a goal-oriented and client-centered therapeutic approach designed to minimize resistance, enhance motivation for change, and increase self-efficacy in a nonconfrontational manner (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1995; Rollnick & Miller, 1995). In sum, MAPS utilizes an innovative combination of motivational enhancement and cognitive-behavioral treatment techniques, is built around a structure derived from effective approaches to chronic care management and patient navigation, is designed for all individuals regardless of their readiness to change, and specifically targets cardinal mechanisms underlying substance use, including motivation, agency/self-efficacy, and stress/negative affect.

MAPS is a unique treatment approach for several reasons. For example, although other conceptualizations of behavior change also emphasize both motivation and skills training, motivational shifts are conceptualized as relatively stable changes in “stage” (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Similarly, MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2009) has two distinct phases of treatment: building motivation (Phase 1) and strengthening commitment (Phase 2; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The transition to Phase 2 is prompted by participant cues of readiness to change, and the initiation of Phase 2 is a process entailing recapitulation, asking key questions, developing a change plan, etc. (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). In contrast to an emphasis on stages and phases, MAPS is unique in that it conceptualizes motivation as a fluid construct that can fluctuate on a moment-to-moment basis depending on context. Counselors carefully assess and attend to changes in motivation so that treatment strategies are appropriately matched to motivation in the moment.

MAPS counselors follow a treatment manual and are trained to carefully attend to language used by their clients to help determine when to shift—on a moment-to-moment basis—from a discussion focused on CBT-based skills development to motivational enhancement and back again. Specifically, “change” and “sustain” talk expressed by the client serve as triggers intended to facilitate a shift from one approach to the other and back again. Change talk refers to language that indicates that an individual is moving toward or even just thinking about change (expressed desire, ability, reasons, or need for change). Examples of change talk are provided below.

“I really want to quit.”

“I think I could start cutting back if I tried. I’ve done it before.”

“I don’t want my kids to see me smoking.”

“I need to do this before I get cancer or some other terrible disease.”

When counselors consistently hear the client voicing change talk, it serves as a signal that it is time to transition from motivational enhancement to a more CBT-based skills training approach, while maintaining the integrity of the MI framework.

Sustain talk refers to language that clients use to resist change. Examples of sustain talk are provided below.

“I really don’t think I want to quit anymore.”

“I’ve tried so many times, and I just don’t have the willpower to do it.”

“Smoking is the only thing that eases my anxiety.”

“I need to smoke in order to relax.”

When counselors begin to hear this type of language, it serves as a signal to move out of or stay away from a problem-solving, skills-building-based approach. Shifts from motivational enhancement to CBT-based skills training can occur at any time, during any session, and even from one target behavior/goal to another.

The use of client language to help guide the course of treatment on a moment-to-moment basis is consistent with research by Amrhein and colleagues (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003), who evaluated the role of client commitment language during MI treatment in predicting substance use outcomes. They found that the strength of commitment language expressed by clients uniquely predicted substance use outcomes such that stronger commitment language was associated with significantly more days abstinent following treatment, particularly when stronger commitment language was expressed toward the end of the treatment sessions. By attending to client language carefully and adapting the course of treatment to appropriately match the client’s degree of motivation and commitment in the moment, MAPS should enhance treatment outcomes compared to other more static treatment approaches that incorporate components of MI and CBT.

Given the emphasis in MAPS on shifting back and forth between MI and CBT based on client language, it is critical that MAPS be implemented in a consistent way across therapists. Therefore, the degree to which MAPS counselors are effectively delivering the treatment is regularly evaluated by listening to and coding a random sample of recorded sessions each month. A modified version of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code 3.1.1 (MITI) is used to measure therapists’ adherence to MAPS. We have added a global scale, Desirable Shifting, to the MITI. This scale rates each counselor’s skill at shifting back and forth between MI and CBT on a 1–5 scale (1 = a complete absence of shifting appropriately in response to client language and 5 = an ability to always shift appropriately from one modality to another based on client language). If counselors begin to consistently score below minimum coding standards, more intense supervision is provided.

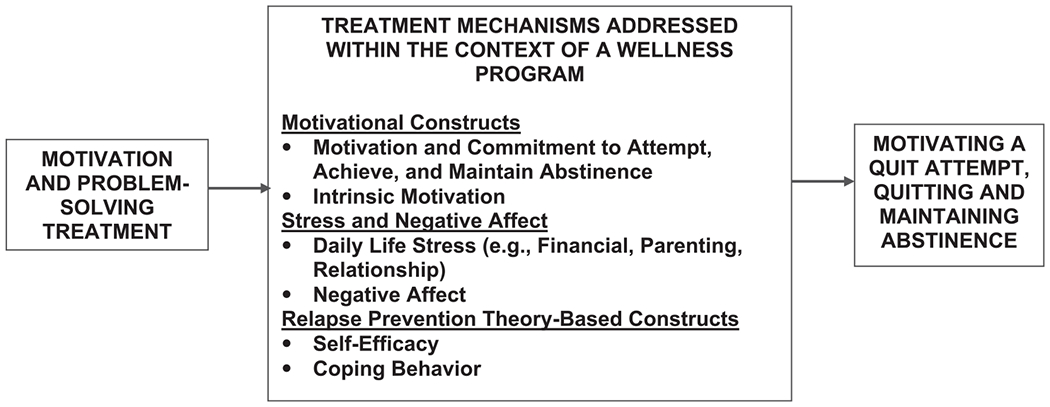

MAPS utilizes motivationally based techniques to enhance commitment and intrinsic motivation for change, and cognitive-behavioral techniques to target self-efficacy, coping, stress, and negative affect (Fig. 1). Moreover, MAPS targets motivation and skills training within the context of a wellness program created in collaboration with each patient. Such a program includes not only goals related to behavior change, but also a plan for addressing other salient concerns such as anxiety, stress, depression, interpersonal issues, and family problems. MAPS also includes a focus on connecting participants with resources in the community to address their needs, such as vocational and educational training, and free or low-cost child care and medical treatment. Thus, in addition to directly targeting behavior change, the goal in MAPS is to assist individuals with general life stressors that are ultimately presumed to influence motivation, difficulty changing, and relapse (Drobes, Meier, & Tiffany, 1994; Shiffman & Waters, 2004; Wetter, Fiore, et al., 1999). By addressing the larger context in which behavior change occurs, not only are many of the barriers for success addressed, but adherence may be increased because individuals perceive that the counselors care about them as whole people, and are not solely interested in their target behavior. Moreover, prioritizing and addressing substance users’ prominent concerns is also hypothesized to help individuals maintain their investment in the therapy process.

Fig. 1.

Proposed Treatment Mechanisms.

Our wellness program is similar to an approach recently described by Wagner and Ingersoll (2009) that uses MI to target multiple problematic behaviors simultaneously and facilitate broad lifestyle changes. Because MAPS is focused on both enhancing motivation and problem-solving/coping skills, this approach is appropriate for individuals who are not motivated to change, those who are ready to change, and those who have already initiated change. Most important, our previous research has demonstrated the efficacy of MAPS and its precursors for motivating a smoking quit attempt, increasing smoking cessation, and preventing relapse (McClure, Westbrook, Curry, & Wetter, 2005a; Reitzel et al., 2010; Wetter et al., 2007; Wetter et al., 2010).

Targeting Shifts in Motivation to Change

Applied to tobacco use and dependence, MAPS utilizes a motivational enhancement approach to develop discrepancy between the patient’s values, goals, and their smoking behaviors/history that is expected to have utility in treating all smokers regardless of their motivation to quit. This is important because a number of studies support that intention and motivation to quit smoking may vary over short periods of time. For example, one study found that intention to quit among smokers in the U.S. and Sweden changed rapidly and spontaneously over the course of a 4-week assessment period (Hughes, Keely, Fagerstrom, & Callas, 2005). Similarly, Werner and colleagues found that 41% of smokers reported that their motivation to quit smoking changed daily (Werner, Lovering, & Herzog, 2004). Larabie (2005) found that a majority of smokers and ex-smokers reported making unplanned quit attempts, suggesting that cessation may have been influenced by abrupt increases in motivation and/or intentions to quit. Finally, nearly half of smokers who responded to a household survey reported that their most recent quit attempt had been unplanned, and that unplanned (vs. planned) quit attempts were more likely to be successful (West & Sohal, 2006). These findings are consistent with a new model of cessation based on catastrophe theory recently proposed by West (2006). The model holds that smokers have varying levels of motivational “tension” to quit smoking, and that even rather small environmental “triggers” may lead to either (a) sudden cessation attempts, or (b) plans to quit at some later point in time. A plan to delay quitting (vs. attempting to quit immediately) may reflect a lower level of motivation or commitment to quitting (West, 2006). Thus, measures of motivation or intentions to quit may only be valid for short periods of time, as motivation and intentions may fluctuate within the course of a single day.

Distinction Between MAPS and Other Prominent Hybrid Treatments

As described above, MAPS follows from and seeks to extend previously developed treatments that have combined skills training with motivational strategies. Several previous studies have evaluated hybrid treatment studies for substance abuse involving the combination of skills training with motivational enhancement strategies (Anton et al., 2006; Babor et al., 2004; Budney et al., 2000; COMBINE Study Research Group, 2003; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2009; McKee et al., 2007; Stein et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2006; Stephens, Babor, Kadden, & Miller, 2002). Consistent with these approaches, MAPS draws heavily upon and overlaps considerably with MI. Specifically, MAPS is grounded in MI in that all CBT-based treatment components are delivered within an MI framework. However, MAPS extends purely MI-based approaches in that the counselor shifts completely from motivational enhancement to CBT-based skills training and back again based on the degree to which the client expresses “sustain talk” versus “change talk.” Therefore, the degree to which MAPS counselors draw upon MI versus CBT is heavily guided by client language within sessions, and counselors may shift back and forth between MI and CBT multiple times during the course of a single treatment session. In contrast, previous hybrid treatments have generally emphasized motivational enhancement at the beginning of treatment and more a CBT-based approach later in treatment, with the caveat that the focus of counseling may shift back to motivational enhancement if a client lapses or relapses to substance use. Furthermore, although existing approaches that draw upon both MI and CBT are likely to address issues salient to the client that are broadly related to substance use such as general stress, depression, anxiety, and relationship and family issues, MAPS is unique in that it is built around a formal wellness program developed jointly by the client and therapist at the beginning of treatment that is used to guide the treatment. Because the wellness program is a central component of MAPS, it is revisited often throughout the course of treatment.

Distinction Between MAPS and Stage-Based Interventions

Interventions based on the transtheoretical model (TTM) are intended to address both motivation and skills training through matching the content of cessation treatment to an individual’s stage of readiness to change, which is intended to facilitate forward movement of the individual through the change process. The model posits that an individual’s stage of change should be reassessed often to ensure that the treatment content is optimally tailored. Thus, stage-based interventions are dynamic in that they are intended to evolve as individuals move through the stages of change (Prochaska et al., 1992). For example, the treatment focus for individuals who are in earlier stages of change with regard to quitting smoking (i.e., precontemplation, contemplation) is generally on enhancing motivation to quit. For individuals who are in more advanced stages (i.e., action or maintenance), the focus of treatment is on training in the use of coping skills to achieve and/or maintain abstinence from smoking.

Thus far, interventions that target motivation based on stage of change have yielded equivocal results. Sutton (2001) conducted a review of TTM-based interventions for substance use and concluded that “current evidence for the model as applied to substance use is meager and inconsistent.” Similarly, Riemsma and colleagues (2003) systematically reviewed 23 randomized controlled stage-based counseling and self-help trials for smoking cessation and concluded that “The evidence suggests that stage-based interventions are no more effective than non-stage based interventions or no intervention in changing smoking behavior.” However, as acknowledged in the review (Riemsma et al., 2003), the evidence base for smoking cessation interventions based on the TTM is limited because of weaknesses in study designs, lack of clarity about the algorithms used to assign participants to stage, and inconsistency in the interventions for a given stage (see Sutton, 2001, for further elaboration). In fact, Sutton (2005) and others have noted that a number of these studies may not have been proper applications of the TTM (e.g., it is unclear whether some interventions were truly stage-matched). It is also important to note that two studies not included in the Riemsma et al. review (2003) have supported the efficacy of stage-matched self-help interventions for smoking cessation (Dijkstra, De Vries, Roijackers, & van Breukelen, 1998; Prochaska, DiClemente, Velicer, & Rossi, 1993), and the Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline concluded that such interventions are promising (Fiore et al., 2000). Sutton (2001) has proposed that a motivational continuum (rather than distinct stages) underlies the change process. MAPS attempts to address this motivational continuum by being responsive to moment-to-moment changes in motivation, as well as by addressing multiple life issues influencing the motivation to attempt, achieve, and maintain abstinence.

MAPS is intended to build upon and extend previous hybrid interventions for substance abuse. MAPS is most similar to the CBI evaluated in the COMBINE trial (Anton et al., 2006) and to integrative approaches described by Arkowitz and Westra (2004) and by Constantino and colleagues (2009), in that skills training and motivational strategies are truly integrated throughout treatment. In contrast, the other approaches generally combined motivational techniques with skills training by delivering motivationally based treatment during the initial session or sessions, followed by subsequent sessions devoted to skills training (Budney et al., 2000; Kertes et al., 2010; McKee et al., 2007; Westra et al., 2009). MAPS was designed to extend previous hybrid approaches through focusing heavily on fluid shifts between skills training and motivational strategies throughout treatment delivery.

MAPS was recently evaluated in an NCI-funded randomized clinical trial intended to prevent postpartum smoking relapse among underserved pregnant women who quit smoking because of their pregnancy (Reitzel et al., 2010). Participants (N=251) were very diverse (65% minority) and primarily low income (55% with total annual household incomes <$30,000). Importantly, MAPS significantly increased biochemically verified postpartum abstinence through 6 months postpartum (OR=1.60; p=.05). Further, each of the hypothesized motivational mechanisms was significant (stage of change, motivation, intrinsic motivation; all p’s<.05) and the other key mechanisms approached significance (self-efficacy for positive/social situations and negative affect situations, negative affect, all p’s<.10; Wetter et al., 2010). In sum, even in this small trial of largely unmotivated women, MAPS positively influenced the mechanisms of abstinence and key treatment mechanisms.

In addition, MAPS is currently being evaluated in a small randomized clinical trial to treat both tobacco dependence and at-risk alcohol use among smokers who are also at-risk alcohol users (NIAAA, 1995; USDHHS & USDA, 1990), a large randomized clinical trial among low-income smokers who are not ready to quit, a randomized clinical trial among college students participating in a Quit and Win contest, and a church-based randomized clinical trial to promote positive changes in diet and physical activity among overweight/obese African American adults. Thus, MAPS is being evaluated for efficacy across the spectrum of tobacco cessation, as well as for multiple and other health risk behaviors. Although MAPS has demonstrated efficacy in one completed randomized clinical trial (Reitzel et al., 2010) and is currently being evaluated in several other ongoing trials, a limitation of MAPS is that it has not yet been directly compared with stage-based treatment in a randomized clinical trial. This is an important direction for future research.

Theoretical Basis for MAPS

Social Cognitive Theory

The overarching theoretical rationale for MAPS is the social cognitive or “relapse prevention” model of Marlatt and colleagues (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). Based on cognitive social learning theory (Bandura, 1977, 1986), the model posits that both individual and contextual factors (e.g., affect, smoking cues, cigarette availability) increase drug use motivation and produce high-risk situations, thereby undermining motivation to quit, reducing the likelihood of cessation, and increasing the probability of relapse. Coping behaviors are posited to be instrumental in navigating high-risk situations without using drugs. Moreover, they have been demonstrated to be powerful determinants of success (Davis & Glaros, 1986; Hall, Rugg, Tunstall, & Jones, 1984; Shiffman, 1984; Shiffman, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Hickcox, 1996; Zelman, Brandon, Jorenby, & Baker, 1992). Self-efficacy and outcome expectancies are hypothesized to be causal determinants of coping behaviors and they have been among the better predictors of smoking abstinence (Businelle et al., 2010; Copeland, Brandon, & Quinn, 1995; DiClemente, Fairhurst, & Piotrowski, 1995; Juliano & Brandon, 2002; Wetter et al., 1994). The model has generated a tremendous amount of intervention research demonstrating that social cognitive/relapse prevention theory-based treatments for smoking cessation are effective (Carroll, 1996; Fiore et al., 2000; Irvin, Bowers, Dunn, & Wang, 1999). Furthermore, these treatment components have become fairly standard components of substance use treatments. Nevertheless, such interventions have not yielded consistently superior results relative to other treatment approaches (Carroll, 1996; Lichtenstein & Glasgow, 1992).

One attribution for the lack of superiority of social cognitive theory-based approaches is that the translation of theory into specific treatment components has been incomplete. Relapse prevention theory posits that “High levels of both motivation and self-efficacy are important ingredients … an individual may fail to engage in a specific behavior despite high levels of self-efficacy if the motivation for performance is low or absent” (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). That is, the performance of coping behaviors in high-risk situations during and after a quit attempt requires that individuals be sufficiently motivated to avoid lapse and relapse. As noted by Miller and colleagues (1995), “the key element for lasting change is a motivational shift that instigates a decision and commitment to change. In the absence of such a shift, skill training is premature.” Although the conceptual model used to guide social cognitive theory–based interventions addresses motivation, the interventions themselves have generally focused on skills training with much less of an emphasis on motivation. Therefore, to address this gap, MAPS embeds practical problem-solving strategies drawn from social cognitive theory-based treatments within an overarching motivational enhancement framework drawn from MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Motivational Interviewing

In contrast to social cognitive theory–based interventions, MI-based interventions have predominantly focused on enhancing motivation for change. There are four basic clinical principles underlying MI: (a) expressing empathy, (b) developing discrepancy, (c) rolling with resistance, and (d) supporting self-efficacy. MI avoids labeling, seeks to increase awareness, emphasizes individual responsibility for behavior, facilitates the development of dissonance between desired and problematic behavior, and utilizes goal setting to facilitate movement from behavioral intention to behavioral action within a client-oriented and nonconfrontational therapist perspective.

At least three meta-analyses of MI-based approaches to behavior change have been conducted, with the results unequivocally supporting the efficacy of the approach for alcohol use and other substance use (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Hettema & Hendricks, 2010; Rubak, Sandbaek, Lauritze, & Christensen, 2005). However, only two smoking cessation studies met the inclusion criteria for the Burke et al. meta-analysis (2003), and only one demonstrated a significant treatment effect. The treatment effect in this study (Butler, 1999) was significant for 24-hour point prevalence abstinence, but not for 1-month abstinence. In the meta-analysis conducted by Rubak and colleagues (2005), 12 smoking cessation studies were reviewed with 8 demonstrating significant treatment effects. However, only 3 of the 12 studies included adequate statistical data for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Although the overall effect size for these 3 studies only approached significance (p<.10), the studies were plagued by substantial methodological problems, including very small sample sizes (n’s ranging from 29 to 121) and very minimal MI interventions (e.g., a single session with only short-term follow-up). Subsequent to these meta-analyses, McClure and colleagues (McClure, Westbrook, Curry, & Wetter, 2005b) found that a proactive, MI-based phone counseling intervention targeted at women with a recent abnormal Pap or colposcopy result produced greater treatment seeking and higher abstinence at the 6-month (but not 12-month) follow-up as compared with usual care. The results of a recent comprehensive meta-analysis of MI-based interventions for smoking cessation (Hettema & Hendricks, 2010) indicated significant but very modest effects. The meta-analysis included 31 controlled trials with smoking abstinence as the outcome variable. The overall effect size for MI corresponded to only a 2.3% difference in abstinence rates between MI and comparison treatments. The authors concluded that the overall effect of MI on cessation was similar to the effects observed for other types of behavioral interventions for smoking cessation evaluated in the Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline (Fiore et al., 2008). Thus, MI-based interventions have demonstrated modest success in promoting abstinence from smoking, and there is clearly room for improvement.

How MAPS Addresses Key Mechanisms Relevant to Quitting and Maintaining Abstinence

Evidence suggests that mechanisms such as motivation, self-efficacy, coping behaviors, depression, negative affect, and stress may be crucial to successfully quitting smoking and maintaining abstinence (Businelle et al., 2010; Cinciripini et al., 2003; Davis & Glaros, 1986; DiClemente et al., 1995; Hall et al., 1984; Piasecki, Fiore, McCarthy, & Baker, 2002; Shiffman et al., 1996; Wetter et al., 1994; Zelman et al., 1992). Moreover, theory suggests that there are reciprocal relations between stress/negative affect, social cognitive constructs such as coping, and motivation. That is, stress and negative affect can suppress motivation for behavior change and are likely to erode motivation for maintaining change over time, as well as reduce self-efficacy and inhibit the performance of coping behaviors (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005; Piasecki et al., 2002).

Providing empirical support for these reciprocal relations, Crittenden, Manfredi, Cho, and Dolecek (2007) examined associations over time between general life stress and smoking outcomes among a large sample of low–socioeconomic-status women smokers and found that variations in perceived stress had negative effects on all smoking cessation outcomes examined (i.e., motivation to quit, action toward quitting, stage of readiness to quit, confidence, and abstinence). Conversely, ambivalence and a weak commitment to abstinence can increase stress and negative affect, particularly during high-risk situations (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005). Therefore, addressing each of the mechanisms, in a manner consistent with participants’ preeminent needs and concerns, is an explicit goal of MAPS. For example, the focus of therapy in MAPS could flexibly switch from cognitive-behavioral methods to increase positive affect, to practical problem solving about time management, to strategies to enhance motivation to maintain smoking abstinence, based on the therapist’s attention to the client’s explicit statements about needs, wants, readiness, and importance, as well as their tone and nonverbal behaviors (for face-to-face therapy).

Motivation

A substantial body of evidence demonstrates that motivation is a critical factor underlying both the decision to make a quit attempt, and the likelihood of cessation (Prochaska et al., 1992; Sciamanna, Hoch, Duke, Fogle, & Ford, 2000). Motivation for the maintenance of behavior change has received relatively little attention in the literature despite the fact that relapse prevention theory posits that “The final and most important stage of the change process is the maintenance stage. It is during the maintenance stage (which begins the moment after the initiation of abstinence or control) that the individual must work the hardest to maintain the commitment to change over time” (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Specifically, motivation for maintaining abstinence may weaken and ambivalence may increase as the individual is exposed to temptations and stressors (Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). The extant empirical data support the hypothesis that motivational deficits are important in determining the maintenance of abstinence (Baker, Brandon, & Chassin, 2004; Heppner et al., 2011).

The importance of motivational deficits is also underscored by contextual analyses of relapse indicating that 24% of all relapse episodes are characterized by a prelapse plan to smoke (Shiffman et al., 1996). Not surprisingly, this motivational deficit substantially reduces the likelihood of performing coping behaviors and lapses are often preceded by a lack of coping (Shiffman et al.). Taken together, the findings highlight that both motivation and intentions to quit and remain abstinent change rapidly and dynamically over time, indicating that a flexible and dynamic approach to targeting motivation is required. Thus, MAPS is designed to specifically address this issue.

MAPS attempts to address motivational deficits by having the therapist continually attend to subtle motivational cues, and to adjust therapeutic strategies in response to fluid changes in motivation; for example, from active problem solving to exploring and resolving ambivalence about a problem-solving strategy. That is, a person’s level of motivation determines the degree to which the therapist emphasizes problem-solving and coping skills training versus motivational enhancement. For example, a typical therapeutic exchange between a client and a therapist that addresses ambivalence about quitting smoking during a MAPS-based therapy session might play out as follows.

CLIENT: I’d like to quit because I know it’s supposed to be bad for you, but nothing bad has really happened to me from smoking.

THERAPIST: Even though nothing bad has happened to you yet, you feel a little bit of pressure to do something about your smoking because of everything you hear about what it could do to your health.

CLIENT: Well, I mean, sure it would probably be bad if I kept smoking for years or something … I mean, eventually something bad might happen.

THERAPIST: Your health is important to you, but unless you feel that you are immediately at risk for health problems, you might not want to change your smoking behaviors.

CLIENT: I guess so, but that doesn’t sound so good. You know, my grandmother found out she had emphysema from smoking and by then it was too late to really fix anything. She couldn’t even stop smoking after she found out her diagnosis! I don’t want to end up like that. She was miserable her last few years …

THERAPIST: It’s scary to think that something like that could happen to you. You want to be healthy and smoking might not fit into the picture very well.

CLIENT: Apparently not. Maybe I should give more thought to quitting. I haven’t thought of my grandmother and what she went through in a long time. I don’t see what it would hurt to at least try to quit.

From this point, the therapist might redirect the session to focus on enhancing the commitment and self-efficacy to quit.

THERAPIST: So you are willing to try to quit.

CLIENT: Yes, I’m willing.

THERAPIST: That’s great! One of the things we know from research is that quitting is often the best thing people can do for their health. If it’s okay with you, we can talk a bit about how you might go about quitting, and if you’re ready, after that we can set a quit date.

CLIENT: Sure.

THERAPIST: You mentioned that you tried quitting before, and that you were able to stay quit for almost two weeks last time. Tell me a little about what worked to keep you from smoking for those two weeks.

CLIENT: Well, I stopped going to bars—that was a big one.

THERAPIST: You stopped going to bars, and that helped you not to smoke. What else do you remember?

CLIENT: I guess. … I talked with my wife about it and she was encouraging. I threw out all my ashtrays and cigarettes, and I stayed in my office at lunch rather than going to eat at the picnic tables outside.

THERAPIST: Well, that’s a lot you did right last time. How do you think some of these things might work for you during your quit attempt this time?

CLIENT: Yeah, I see what you’re saying. Maybe I’ve learned something during my previous attempts to quit that will be useful in helping me finally kick the habit.

This example illustrates how the therapist works in MAPS to help build self-efficacy. An example of a possible transition from increasing self-efficacy to identifying critical barriers to quitting follows.

THERAPIST: What we usually do next is to try to understand what situations or barriers have been problematic for you in the past. I know this might be a little difficult since we are talking about things that have kept you smoking. I’m not sure how you feel about this, but often people find that doing this is helpful because they can begin to anticipate difficult situations, which helps them better plan with respect to overcoming these barriers. What are some of the things that have tripped you up in the past?

CLIENT: Well, I can usually make it a few days until something trips me up. Last time, I had a big argument with my wife and left the house to clear my head. On my way home, I bought a pack of cigarettes, and that was the end of that quit attempt!

THERAPIST: It sounds like arguing with your wife has been really difficult for you to handle when you’ve tried to quit in the past. What specifically was difficult about this for you?

CLIENT: I was just so mad that I really needed a cigarette to calm down.

From this point, the therapist might transition directly to coping skills training, and then back to enhancing motivation, as in the following example, but always interacting with the client in a manner consistent with MI.

THERAPIST: Okay, so it sounds like you made that connection between having an argument with your wife and going back to smoking. Tell me about how you think you might be able to get through arguments with your wife this time without smoking.

CLIENT: I just don’t know how I’ll do it. We just argue constantly.

THERAPIST: Would it be okay if I share something with you that other people have told me? Most smokers find it difficult to handle stress and anger—things like arguing with a spouse—when they are trying to stay abstinent. Many smokers try to avoid arguing at all, and even ask for extra support and understanding from their spouse when they are quitting smoking. How might that fit for you, if at all?

CLIENT: I don’t think that really fits for me at all. When my wife and I get really angry at each other, we each become convinced that we’re right. It often takes us hours or even a day or two to get over it. And there is no way I can handle that time while we’re not speaking without smoking. I think I’m just one of those people who will never be able to quit.

THERAPIST: When you think about the changes that might be needed to help you quit smoking, it seems overwhelming. so even though you really want to become a nonsmoker, it seems pointless to even try. It’s really difficult for you to imagine yourself living your life without cigarettes.

CLIENT: Well, I really do want to quit. I can imagine myself being a nonsmoker down the road, but it’s hard for me to see myself actually getting there.

THERAPIST: It’s difficult for you to see how you’ll actually make the transition from smoker to nonsmoker.

CLIENT: Exactly. I guess it might help to talk about some of the situations that are going to be so difficult to get through without smoking.

Stress and Negative Affect

Stress and negative affect in smokers’ lives is likely to result from both the quit attempt itself (e.g., nicotine withdrawal, cue-induced craving), and from general life stressors that are completely independent of the quitting process. Several studies have indicated that such day-today experiences with stress and negative affect may impinge on successful quitting and abstinence maintenance. For example, most smokers experience elevated levels of postcessation negative affect that continue for relatively long periods of time, and these findings hold for smokers who receive nicotine replacement therapy as well as for those smokers who do not (Piasecki, Fiore, & Baker, 1998). In addition, Shiffman and colleagues (1996) demonstrated a strong dose–response relation between smoking-related acute events and the severity of stress/negative affect. The magnitude and trajectory of stress/negative affect over time are also powerful predictors of cessation (Burgess et al., 2002; Piasecki, Jorenby, Smith, Fiore, & Baker, 2003), as are individual differences in affective vulnerability (Glassman et al., 1990; Wetter, Kenford, et al., 1999).

In addition, recent data indicate that financial stress is closely linked with smoking cessation success (Kendzor et al., 2010; Siahpush & Carlin, 2006). Thus, life stressors that are unrelated to the acute quitting process may play a critical role in behavior change. Although MAPS often targets these general life stressors as a focus of counseling without explicitly linking them back to quitting or maintaining abstinence, it is important to note that many of these situations are likely to be ultimately related to successful cessation (Siahpush et al., 2006).

A typical therapeutic exchange between a client and a MAPS counselor that addresses how stress and negative affect influence the success of an initial cessation attempt might occur as follows. In this scenario, the counselor may have begun the session with the mindset that the client was going to use CBT because the previous day was the client’s quit day. However, as soon as the session begins it becomes apparent from the amount of sustain talk used that the client has relapsed. Therefore, the counselor quickly switches to MI.

CLIENT: The past week has been a real struggle for me. I’ve just had so much going on in my life that it’s hard to even think about quitting smoking right now. I know yesterday was my quit day, but when I got home from work I couldn’t take it anymore and I smoked. Last that time we talked I felt like I might be ready to do this, but I just don’t know if I’m ready anymore.

THERAPIST: Life is a little overwhelming lately, and you can’t imagine putting anything else on your plate right now.

CLIENT: Exactly! I just have so much going on. Lately, it seems like the kids have been getting into so much trouble at school. I’m constantly having to deal with phone calls and notes from their teachers, and I’ve tried everything I can think of but nothing seems to be working. Plus, I’m under a lot of stress at work, and I have so many bills to pay! Sometimes I even feel like I’m smoking more than I usually do just to deal with this stress.

THERAPIST: I’m sorry things have been stressful lately. It sounds like you’re working hard just to hold it all together.

CLIENT: The fact that I haven’t quit still weighs heavily on me. I really wish I wasn’t smoking, because I know it’s bad for me and I hate spending money on it. But to be honest, I just can’t see myself doing it right now.

THERAPIST: And that’s completely your choice. I’m not here to push you to do anything you’re not ready for. It sounds like you’re really torn. You can’t see yourself doing it right now, and at the same time it’s not a goal you’re willing to give up on.

CLIENT: That’s true. I definitely know I have to do it, but I feel like it’s something I need to work towards. Maybe once I can get some other things in my life under control, it’ll be easier for me to try again. plus, I feel like there are a lot of things in my life that just add to the smoking. Maybe I could work on some of those first.

THERAPIST: Tell me more about that. What sorts of things do you think are contributing to your smoking more?

CLIENT: Well, we’ve kind of already talked about this before, and I don’t think I really saw it as a problem early on. Lately I’ve noticed that I smoke a lot more when I drink. My family has been getting together a lot on the weekends, and we always have a few drinks when we get together to barbeque. Plus, I have a couple of drinks every now and then to unwind after work. I don’t have a problem with drinking or anything, but it feels like I smoke a lot more when I drink.

THERAPIST: You’ve started to notice that the two kind of go hand in hand, and you’re feeling like maybe it’s time to make some changes with the drinking so you won’t smoke so much.

CLIENT: The smoking may be hard for me to manage, but I know the drinking is something I can control. I really think if I cut back, or even cut it out all together I won’t smoke as much, especially on the weekends.

THERAPIST: I’m not sure if this is something you’d be interested in or not, but what are your thoughts about adding that as a goal on your wellness program? If you’d like, we can talk about how much you’d like to cut back, and when you’d like to start, and we can go from there.

CLIENT: That sounds good to me! I’m willing to work on a plan. I think it would be a good place for me to start.

As illustrated within the scenario, the counselor continuously used an MI framework, and maintained the focus on MI when discussing the topic of smoking and setting a quit day. However, the client expressed more change talk than sustain talk with regard to drinking, which signaled the counselor to switch to a CBT-based problem-solving approach to address drinking behavior.

Social Cognitive Constructs

Because self-efficacy is a determinant of coping behavior (Bandura, 1977, 1986), standard social cognitive approaches to increasing self-efficacy are incorporated within MAPS. Thus, the therapist’s role is to help individuals learn to identify and verbalize issues of concern, recognize when difficult and high-risk situations or behaviors occur, learn to plan ahead for those situations, and acquire and perform coping strategies as appropriate. For example, to increase self-efficacy, the therapist will work to enhance individuals’ perceptions that they can be successful in making changes through identifying steps taken to change or reduce their smoking, providing positive reinforcement for those steps, reframing even small changes as positive steps toward reaching goals, and emphasizing the role of choice in making difficult behavior changes. The therapist’s first step in providing training in the use of coping skills is to help the individuals operationally define goals for change. The therapist then helps the individual to identify potentially difficult situations or barriers that might influence accomplishing the goal, and provides a menu of potential options for coping with difficult high-risk situations and overcoming barriers to change (e.g., avoiding high-risk situations such as bars, coping with urges to smoke and negative affect through positive self-talk, deep breathing, or distraction, and escaping situations that become too overwhelming to effectively cope with).

The following therapeutic exchange illustrates how a typical MAPS session might evolve for a client who has recently quit smoking and experiences a decline in motivation to maintain abstinence as he anticipates attending his birthday party at a bar where his friends will be drinking.

THERAPIST: So the first thing that we have on your wellness program, after your goal of quitting smoking, is to get back into exercising. The last time we spoke you mentioned that you wanted to start off by going to the park down the street a couple of times per week and walking at least 30 minutes. How’s that been going?

CLIENT: It’s actually been going well. It’s been so long since I’ve been active. I was kind of worried that I would be too busy or that I just wouldn’t be very motivated when I got home from work, but I’ve actually stuck with it. I talked to my wife about it after our last session, and she’s been a big help on the days that I don’t feel like going.

THERAPIST: She helps keep you motivated.

CLIENT: She really does! She’s actually been going with me, which helps. But the best thing is that I’ve noticed that I can breathe so much better now that I’m not smoking. I think that’s one of the biggest reasons I stopped being active. It was just so much harder to breathe when I tried to be active before.

THERAPIST: It’s a good feeling to actually know that your health is improving as a result of quitting smoking.

CLIENT: It’s a great feeling! My main priority is to improve my health so I can be around for my family.

THERAPIST: It’s an accomplishment you’ve worked really hard for! So tell me what you would like to do with your physical activity over the next couple of weeks. How would you like to modify what you’re doing, if at all?

CLIENT: I think I’d like to keep it at two days a week for now. Every time I’ve tried to get back into exercising in the past, it seems like I always set such big goals that aren’t realistic. Then, when I’m not able to meet them, I get discouraged and give up. I want to make sure I stick with it this time.

THERAPIST: Sounds great! You really know yourself well. We will keep it at twice per week. Are you still aiming for 30 minutes each time as well?

CLIENT: For now, yes.

THERAPIST: Alright. We will stick to 30 minutes, twice per week. Now the next thing we have on the wellness program is limiting yourself to 1 or 2 beers when you’re out with friends or at family gatherings on the weekends. How has that been for you?

CLIENT: So far, so good—but I’m not sure how much longer I can keep going with that. I mean, I really don’t want anything to jeopardize everything I’ve done with the smoking, but it’s just so hard to not really be able to drink when you’re having a good time. Next weekend is my birthday party, so it may be even harder to stick to the 1- to 2-drink limit.

THERAPIST: It’s hard to see yourself keeping up with this for the long term, and at the same time, you don’t want anything to get in the way of your staying away from smoking.

CLIENT: Yeah, there have been so many times in the past where I’m able to quit smoking and I’m doing well, then I have a night out with friends and it all just goes out the window. It’s harder to say no to a cigarette when your inhibitions are lowered. Once I have that first cigarette, I’m back to full-blown smoking. Even then, I don’t know how realistic it is to not really drink on my birthday, at my own party. All my friends and my family are going to my favorite bar, and I just want to have a good time.

THERAPIST: I can see how that would be an incredibly tempting situation. While you’d like to be able to control your drinking on your birthday, you’re not really confident that you’ll be able to.

CLIENT: It’s just so hard when everyone around you is drinking and having a good time. Plus, it’s hard to say no when people keep offering you drinks. I’m just not sure how it’s going to go….

At this point in the session, because the client is engaging in much more sustain talk than change talk about drinking, the counselor should continue with MI. Next, the counselor uses the decisional balance exercise to help the client clarify his thoughts and feelings about a high-risk situation for drinking and smoking relapse.

THERAPIST: Now David, I know we had a similar discussion when you were thinking about smoking, but I’m just curious about what the good things about drinking might be for you?

CLIENT: Well, there aren’t that many. I don’t feel like drinking is something I have to do, but it does help me to unwind.

THERAPIST: It relaxes you.

CLIENT: It does. Plus, it’s just something I do when I’m out with friends or at a get-together with family.

THERAPIST: A part of your social life.

CLIENT: There’s always a little bit of drinking at our social gatherings. People don’t usually get carried away or anything, but it’s just something that’s around when we get together.

THERAPIST: Sure. It’s something you do in moderation, and usually have good control over. Now what do you think some of the not-so-good things about drinking are for you?

CLIENT: Well, this usually doesn’t happen, but every once in a while I get a little carried away. It’s rare, though. It usually only happens on special occasions.

THERAPIST: On holidays or birthdays.

CLIENT: Exactly, that’s what worries me about this weekend. The aftermath isn’t very fun either. Usually when I get carried away, I feel terrible the next day. I kind of just lay around all day, trying to recover from the night before. My wife hates it, and has no problem pointing it out.

THERAPIST: The consequences aren’t the best when you have too much to drink. You mentioned that you’re worried about getting carried away. What might happen if you did?

CLIENT: Well the worst thing that could happen is that I would have a cigarette. That would be terrible! I’d be really upset with myself, and I think my wife would be disappointed.

THERAPIST: You feel like you would be giving up everything you worked so hard for.

CLIENT: It took a lot for me to be able to quit smoking. It wasn’t easy at all. I’ve tried so many times in the past, and this is the longest I’ve gone without smoking. The more I think about it, I don’t know that I want to do anything to risk giving up everything I’ve worked so hard for. It’s not like I have to go out and drink to celebrate my birthday.

THERAPIST: Maintaining your abstinence is just too important to you.

CLIENT: I’ve just come way too far to go back to smoking.

THERAPIST: So if we go back to your wellness program, where does that leave you? What would you like to do with your goal of limiting the amount of alcohol you drink?

Now that the client is exhibiting a good amount of change talk (rather than sustain talk), the therapist shifts back into CBT-based skills training.

CLIENT: I guess I could try to stick to what I already planned, and try to keep it at one or two drinks. Maybe I should just have some friends over at my place instead of going out somewhere. It seems like I drink more when I’m out at a bar. Now I just have to find a way to not go overboard.

THERAPIST: If you’re interested I can share some ideas that other people we’ve worked with sometimes use. I’m not sure if they would work for you, but you can let me know.

CLIENT: Sure, I’m okay with that.

THERAPIST: Often people that we work with try using some of the same skills that they used when they were trying to cut back or quit smoking. For example, they’ll avoid situations or people that they think may influence them to drink more. Some people will talk to their friends or family ahead of time and ask that they help encourage them or not pressure them to drink too much. I’ve even had some people say that they will just keep the same drink in their hand throughout the night or drink a lot of water in between drinks. What ideas come to mind for you?

CLIENT: Well, I’ve actually done that last one before and it worked out okay. I drank several glasses of soda or water in between drinks, and people didn’t really push me to drink a whole lot because it always seemed as though I had a drink in my hand.

THERAPIST: So you’re thinking that may work for you on your birthday.

CLIENT: I’m going to give it a shot.

Presented below is a brief session-by-session overview intended to represent the general therapeutic content that should be addressed during a six-session MAPS-based treatment protocol.

Session-by-Session Overview of a Six-Session MAPS-Based Treatment Protocol

Session 1

The goals for the first session include: (a) introduction of the agenda and establishing rapport; (b) review of confidentiality; (c) collection of information regarding smoking history, previous quit attempts, and current smoking; (d) administration of importance, confidence, and readiness rulers; (e) building motivation and completing the decisional balance exercise if the client is not ready to quit or preparing for the quit attempt if the client is ready to quit; (f) introduction of the wellness program; and (g) ending the session and scheduling the next session.

The introduction of the wellness program is a critical component of the first treatment session. To introduce the wellness program/plan, the counselor might use the following language: “The final thing on today’s agenda is to talk with you about the wellness program. The wellness program is like a list of goals that can remind us of what you’d like to accomplish during the time we work together. May I have your permission to work on this plan with you? The first goal usually refers to something about your smoking. You’ve already indicated that you are/aren’t ready to make a quit attempt.”

For clients who are not ready to quit, the counselor might use the following language to talk about goal setting: “You’re not yet ready to quit, but even deciding that you are willing to talk with me about smoking again in the future, or that you’d be interested in thinking about what things would be like if you were to quit would be reasonable goals? So, what should we write for yours?” For clients who are ready to quit, the counselor might says self the followingp: “So, what should we write for your smoking goal?” The counselor then follows up by asking what else can be done to help the client prepare for the goal, and ensures that the goal is measurable.

For all clients (regardless of whether or not they are ready to quit smoking), the counselor then introduces the topic of expanding the wellness program using language similar to the following: “Now, we’ll talk about this more fully the next time we speak, but the wellness program can contain a number of other goals. For example, people usually list other things that are important to them, things that have not been going well for them, or things that are connected with their smoking that they might also want to change, such as their stress level, feelings of depression, relationship issues, or their drinking. The wellness program gives us some specific things to touch base on during our next few sessions. What else should we list on your wellness program ?” At the end of the session, the counselor tells the client that the goals will be revisited during each session and that goals on the wellness program can change at any time. The counselor then summarizes the goals and checks in with the client to make sure nothing has been forgotten.

Session 2

In the second session, in addition to introducing the agenda, the therapist’s goal is to continue building rapport. Therapist and client also review—and possibly revise—wellness program goals. If the client has not set a quit date, the counselor inquires about how things are going with smoking, and explores the client’s thoughts about quitting with the readiness rulers. If the client is ready to take action, the counselor draws from the “Preparing to Quit Smoking” module of the manual. If the client is not ready to take action, the counselor draws upon MI strategies to build motivation. At this stage, many smokers are ambivalent about their decision to quit and may lead themselves into negative self-talk. The counselor listens carefully and then reflects the client’s change talk statements in an effort to bolster motivation and enhance self-efficacy. The counselor also informs the client that wellness program goals can be set to “increase readiness to make a quit attempt.” If the client has quit, the counselor inquires about how things are going and listens carefully for ambivalence about maintaining abstinence. The counselor positively reflects change talk expressed by the client to help bolster motivation, enhance self-efficacy, and highlight small achievements in an effort to increase motivation to remain quit. If the client is at all willing to address smoking, the counselor begins to address high-risk situations for returning to smoking, and the remainder of the wellness program goals are reviewed, addressed, and revised if needed.

Values identification is another important element of Session 2. The therapist assists in identifying valiues that are important to the client. These values are linked to the goals listed in the wellness program to help the client move toward change. The counselor might say the following: “If it’s okay with you, we can move on to exploring values that are most important to you and your family. Sometimes our goals, such as the ones you listed on your wellness program, are important to us because of the values that we have in life, and it may be helpful to see how that might or might not apply to the goals you listed, such as your [insert smoking goal here].”

The remainder of the session focuses on enhancement of self-efficacy and scheduling of the next session.

Sessions 3, 4, and 5

The goals for the third, fourth, and fifth sessions are as follows: (a) continuation of rapport building and introduction of the agenda; (b) review and possible revision of wellness program goals (review of progress with quitting; review of barriers to quitting; review of high-risk situations, CBT-based skills training strategies, and lapses); (c) check-in with importance, confidence, and readiness rulers; (d) repetition of decisional balance exercise as needed; (e) use of CBT-based treatment modules as needed; and (f) scheduling of next session.

Session 6

The goals for the final session include (a) reconnection with the client; (b) review of progress made during treatment; (c) consideration of next steps; and (d) saying goodbye and providing referrals as necessary.

Summary and Conclusions

Despite strong theoretical and empirical bases for focusing on both motivational and social cognitive constructs, there are few evidence-based counseling interventions for substance use that encompass both motivational enhancement strategies and coping skills training, and to the best of our knowledge, even fewer that address motivation as a dynamic factor than can fluctuate rapidly and fluidly, or that include a strong emphasis on motivation following behavior change (i.e., it is generally assumed, whether explicitly or implicitly, that individuals in the action or maintenance stage are sufficiently and consistently motivated to maintain behavior changes (Burke et al., 2003; Fiore et al., 2000; McClure et al., 2005b). In response to these omissions, MAPS is a hybrid treatment for substance use based on the clinical integration of empirically supported coping skills training/problem-solving techniques derived from social cognitive theory (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004) and motivational enhancement techniques derived from MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MAPS draws heavily from the model proposed by Baer and colleagues (1999) nearly 10 years ago, yet is unique in that it addresses substance use within the context of general life stressors and dynamically switches between skills training and motivational enhancement strategies based on motivation to attempt, achieve, and maintain abstinence. MAPS has demonstrated efficacy in the prevention of postpartum smoking relapse (Reitzel et al., 2010) and we believe that it also has relevance for other health risk behaviors. Hybrid approaches, such as MAPS, for the treatment of substance use have the potential to profoundly affect public health. Therefore, we believe that the call for further research on hybrid approaches made by Baer over a decade ago remains salient today. In addition to describing MAPS, the current paper is intended to serve as a call for further research on hybrid approaches for the treatment of substance abuse and dependence.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA89350; R01CA125413; R25TCA57730) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (K01DP000086; K01DP001120).

Contributor Information

Jennifer Irvin Vidrine, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Lorraine R. Reitzel, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Patricia Y. Figueroa, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Mary M. Velasquez, The University of Texas–Austin

Carlos A. Mazas, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Paul M. Cinciripini, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

David W. Wetter, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

References

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, & Fulcher L (2003). Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 862–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, … COMBINE Study Research Group. (2006). Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. Jama, 295(17), 2003–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H, & Westra HA (2004). Integrating motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 18, 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Carroll K, Christiansen K, Kadden R, Litt M, McRee B, …, Herrell J (2004). Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, & Donovan DM (1999). Integrating skills training and motivational therapies. Implications for the treatment of substance dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 17(1–2), 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Brandon TH, & Chassin L (2004). Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 463–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Radonovich KJ, & Novy PL (2000). Adding voucher-based incentives to coping skills and motivational enhancement improves outcomes during treatment for marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 1051–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess ES, Brown RA, Kahler CW, Niaura R, Abrams DB Goldstein MG & Miller IW (2002). Patterns of change in depressive symptoms during smoking cessation: Who’s at risk for relapse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, & Menchola M (2003). The efficacy of Motivational Interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 843–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Reitzel LR, Costello TJ, Cofta-Woerpel L, Li Y, …, Wetter DW (2010). Mechanisms linking socioeconomic status to smoking cessation: a structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychology, 29, 262–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RN (1999). Motivating patients to change. Geriatrics, 54, 3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM (1996). Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 4, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cinciripini PM, Wetter DW, Fouladi RT, Blalock JA, Carter BL, Cinciripini LG, & Baile WF (2003). The effects of depressed mood on smoking cessation: mediation by postcessation self-efficacy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMBINE Study Research Group. (2003). Testing combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions in alcohol dependence: rationale and methods. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 27, 1107–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino MJ, DeGeorge J, Dadlani MB, & Overtree CE (2009). Motivational interviewing: A bellwether for context-responsive psychotherapy integration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 1246–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Brandon TH, & Quinn EP (1995). The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment, 7, 484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden KS, Manfredi C, Cho YI, & Dolecek TA (2007). Smoking cessation processes in low-SES women: The impact of time-varying pregnancy status, health care messages, stress, and health concerns. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1347–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JR, & Glaros AG (1986). Relapse prevention and smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors, 11, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Fairhurst SK, & Piotrowski NA (1995). Self-efficacy and addictive behaviors In Maddux J (Ed.), Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: Theory, research, and application (pp. 109–141). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J, & van Breukelen G (1998). Tailored interventions to communicate stage-matched information to smokers in different motivational stages. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobes DJ, Meier EA, & Tiffany ST (1994). Assessment of the effects of urges and negative affect on smokers’ coping skills. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32, 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, …, Wewers ME (2000). Treating tobacco use and dependence: Clinical practice guideline (No. 1-58763-007-9). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NJ, Curry SJ, …, Wewers ME (2008). Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, & Johnson J (1990). Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. Journal of the American Medical Association, 264, 1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock G, Barrowclough C, Tarrier N, Moring J, O’Brien R, Schofield N, …, Lewis S (2003). Cognitive-behavioural therapy and motivational intervention for schizophrenia and substance misuse: 18-month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Rugg D, Tunstall C, &Jones RT (1984). Preventing relapse to cigarette smoking by behavioral skill training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 372–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner WL, Ji L, Reitzel LR, Castro Y, Correa-Fernandez V, Vidrine JI, … (2011). The role of prepartum motivation in the maintenance of postpartum smoking abstinence. Health Psychology, 30, 736–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, & Hendricks PS (2010). Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 868–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely JP, Fagerstrom KO, & Callas PW (2005). Intentions to quit smoking change over short periods of time. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, & Wang MC (1999). Efficacy of relapse prevention: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano LM, & Brandon TH (2002). Effects of nicotine dose, instructional set, and outcome expectancies on the subjective effects of smoking in the presence of a stressor. J Abnorm Psychol, 111(1), 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Costello TJ, Castro Y, Reitzel LR, Cofta-Woerpel LM, …, Wetter DW (2010). Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 702–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes A, Westra HA, Angus L, & Marcus M (2010).The impact of motivational interviewing on client experiences of cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 18, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Larabie LC (2005). To what extent do smokers plan quit attempts? Tobacco Control, 14, 425–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, & Glasgow RE (1992). Smoking cessation: What have we learned over the past decade? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Stanton CA, Papandonatos GD, Shadel WG, Stein M, Tashima K,…, Niaura R (2009). Motivation and patch treatment for HIV+ smokers: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 104, 1891–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Donovan DM (2005). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behavior, 2nd Ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Gordon JR (1985). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McClure JB, Westbrook E, Curry SJ, & Wetter DW (2005). Proactive, motivationally enhanced smoking cessation counseling among women with elevated cervical cancer risk. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 7, 881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure JB, Westbrook E, Curry SJ, & Wetter DW (2005). Proactive, motivationally enhanced smoking cessation counseling among women with elevated cervical cancer risk. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 7, 881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Carroll KM, Sinha R, Robinson JE, Nich C, Cavallo D, & O’Malley S (2007). Enhancing brief cognitive-behavioral therapy with motivational enhancement techniques in cocaine users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91, 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior, 2nd Ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2009). Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37, 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, & Rychtarik RG (1995). Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence (No. 94–3723). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA (1995). The physician’s guide to helping patients with alcohol problems (Publication No. 95–3769). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, & Baker TB (1998). Profiles in discouragement: Two studies of variability in the time course of smoking withdrawal symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 238–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, McCarthy DE, & Baker TB (2002). Have we lost our way? The need for dynamic formulations of smoking relapse proneness. Addiction, 97, 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, & Baker TB (2003). Smoking withdrawal dynamics: II. Improved tests of withdrawal-relapse relations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, & Norcross JC (1992). In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Velicer WF, & Rossi JS (1993). Standardized, individualized, interactive, and personalized self–help programs for smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 12, 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Costello TJ, Li Y, …, Wetter DW (2010). Preventing postpartum smoking relapse among diverse low-income women: A randomized clinical trial. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 12, 326–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemsma RP, Pattenden J, Bridle C, Sowden AJ, Mather L, Watt IS, & Walker A (2003). Systematic review of the effectiveness of stage based interventions to promote smoking cessation. British Medical Journal, 326(7400), 1175–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, & Miller WR (1995). What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritze T, & Christensen B (2005). Motivational Interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice, 305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciamanna CN, Hoch JS, Duke GC, Fogle MN, & Ford DE (2000). Comparison of five measures of motivation to quit smoking among a sample of hospitalized smokers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(1), 16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S (1984). Coping with temptations to smoke. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, & Hickcox M (1996). First lapses to smoking: within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, & Waters AJ (2004). Negative affect and smoking lapses: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]