The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains and lack of efficient vaccines have made Shigella a priority organism for the World Health Organization (1). Therefore, bacteriophage therapy has received increasing attention as an alternative therapeutic approach. LPS Oag is the most variable part of LPS due to chemical modifications and is the target of bacteriophage Sf6 (S. flexneri specific). We dissected the evolution of S. flexneri serotype Y to 2a2, which revealed a new role for a gene acquired during serotype conversion and furthermore identified new specific forms of LPS receptor for Sf6. Collectively, these results unfold the importance of the acquisition of those Oag modification genes and further our understanding of the relationship between Sf6 and S. flexneri.

KEYWORDS: O-acetylation, O antigen, Sf6, Shigella flexneri, bacteriophages, glucosylation, lipopolysaccharide, serotypes

ABSTRACT

Shigella flexneri is a major causative agent of bacillary dysentery in developing countries, where serotype 2a2 is the prevalent strain. To date, approximately 30 serotypes have been identified for S. flexneri, and the major contribution to the emergence of new serotypes is chemical modifications of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) component O antigen (Oag). Glucosylation, O-acetylation, and phosphoethanolamine (PEtN) modifications increase the Oag diversity, providing benefits to S. flexneri. LPS Oag acts as a primary receptor for bacteriophage Sf6, which infects only a limited range of S. flexneri serotypes (Y and X). It uses its tailspike protein (Sf6TSP) to establish initial interaction with LPS Oags that it then hydrolyzes. Currently, there is a lack of comprehensive study on the parent and serotype variant strains from the same genetic background and an understanding of the importance of LPS Oag O-acetylations. Therefore, a set of isogenic strains (based on S. flexneri 2457T [2a2]) with deletions of different Oag modification genes (oacB, oacD, and gtrII) that resemble different naturally occurring serotype Y and 2a strains was created. The impacts of these Oag modifications on S. flexneri sensitivity to Sf6 and the pathogenesis-related properties were then compared. We found that Sf6TSP can hydrolyze serotype 2a LPS Oag, identified that 3/4-O-acetylation is essential for resistance of serotype 2a strains to Sf6, and showed that serotype 2a strains have better invasion ability. Lastly, we revealed two new serotype conversions for S. flexneri, thereby contributing to understanding the evolution of this important human pathogen.

IMPORTANCE The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains and lack of efficient vaccines have made Shigella a priority organism for the World Health Organization (1). Therefore, bacteriophage therapy has received increasing attention as an alternative therapeutic approach. LPS Oag is the most variable part of LPS due to chemical modifications and is the target of bacteriophage Sf6 (S. flexneri specific). We dissected the evolution of S. flexneri serotype Y to 2a2, which revealed a new role for a gene acquired during serotype conversion and furthermore identified new specific forms of LPS receptor for Sf6. Collectively, these results unfold the importance of the acquisition of those Oag modification genes and further our understanding of the relationship between Sf6 and S. flexneri.

INTRODUCTION

Shigella is a highly contagious human pathogen that causes shigellosis or bacillary dysentery via fecal-oral route infection. Shigellosis is a global issue that has high morbidity (incidence of 36.4/1,000) and mortality (2.9 deaths/100,000) rates (2), especially in children under the age of 5 years old in developing countries. As few as 10 organisms are sufficient to cause shigellosis (3). The major situations giving rise to shigellosis are the presence of poor sanitation systems, travel to areas of endemicity, and men having sex with men (4). Shigella can be divided into four species: S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei (5, 6). These species are subdivided based on the structure of their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O antigen (Oag) repeat units (RUs) (7). To date, 30 Oag variants have been reported for S. flexneri (5). S. flexneri is the most prevalent species in developing countries (6), while S. sonnei is the leading cause of shigellosis in developed countries such as the United States (8). The three most prevalent serotypes of S. flexneri in Asian countries are 2a (which includes 2a1 and 2a2) (29%), 3a (14%), and 1a (9%) (9, 10).

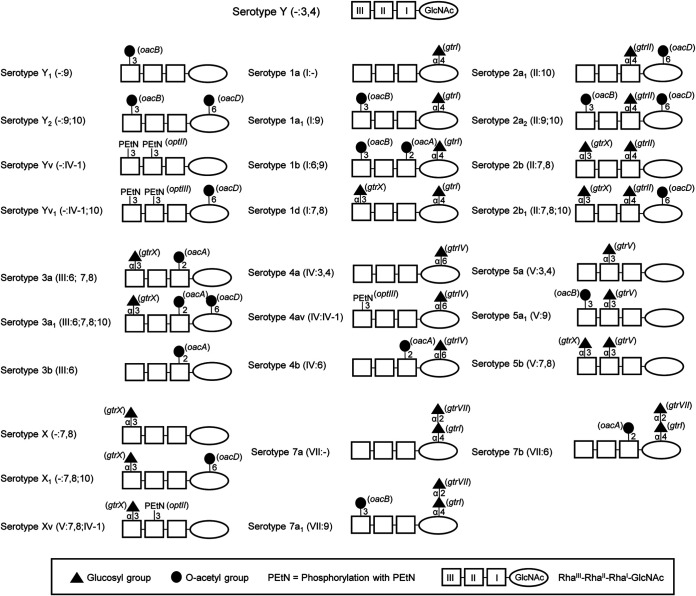

All known S. flexneri serotypes except serotype 6 share the same Oag polysaccharide backbone, which is composed of three l-rhamnose residues (RhaIII-RhaII-RhaI) and one residue of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (11). This forms the basic Oag polysaccharide, which is referred to as serotype Y. The addition of various chemical groups (α-d-glucopyranosyl, O-acetyl, or phosphoethanolamine [PEtN]) to different sugars within the Oag backbone gives rise to the diversity in Oag structure and serotypes (Fig. 1) (5). According to the typing scheme of Boyd, S. flexneri serotypes are defined by a series of type and group antigenic determinants (O-factors) (12, 13). Type O-factors are defined by Roman numerals I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII and are found only within one serotype (e.g., serotypes 2a and 2b share the type O-factor II). Group O-factors are defined by Arabic numerals 3,4; 6; 7,8; 9; and 10. These group O-factors can be shared among different serotypes (e.g., group O-factor 7,8 is found in serotypes 2b, 3a, 5b, and X) (13). Serotypes 2a, 3b, 4a, 5a, and Y contain the group O-factor 3,4, which is defined as a backbone epitope linked to the linear RhaI-GlcNAc-RhaIII trisaccharide fragment (14, 15). The antigenic formula for serotype Y is [-:3,4], as it does not have any type O-factor (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Chemical structures of S. flexneri serotypes 1 through 5, 7, X, and Y. The basic O-polysaccharide backbone (serotype Y, group O-factor 3,4) is comprised of repeat units of three l-rhamnose residues (RhaIII-RhaII-RhaI) and one N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc). Each serotype differs by the addition of a glucosyl group, O-acetyl group, or phosphoethanolamine (PEtN) on different sugars within the repeat unit via the linkages indicated. Specific O antigen modification genes are indicated in parentheses. Each serotype has one type-specific (Roman numeral) and one or more group-specific (Arabic numeral) antigenic determinants. Serotypes 2a, 3b, 4a, 5a, and Y possess group O-factor 3,4, which is associated with the O-polysaccharide backbone but is omitted from the antigenic formula when other group O-factors are present.

In S. flexneri, O-acetylations have been reported at position 2 of RhaI (2-O-acetylation), at position 3 or 4 of RhaIII (3/4-O-acetylation), and at position 6 of GlcNAc (6-O-acetylation), which confer group O-factors 6, 9, and 10, respectively (Fig. 1) (16–18). 2-O-acetylation is mediated by the oacA (O-acetyltransferase-encoding) gene carried by the temperate bacteriophage Sf6 and occurs in serotypes 1b, 3a, 3b, 4b, and 7b (19, 20). 3/4-O-acetylation is mediated by the oacB gene carried by a transposon-like mobile element and occurs in serotypes 1a1, 1b, 2a2, 5a1, 6, 7a1, Y1, and Y2 (17, 21). 6-O-acetylation is mediated by the oacD gene carried by the bacteriophage SfII prophage and occurs in serotypes 2a1, 2a2, 2b1, 3a1, X1, Y2, and Yv1 (18).

Glucosylation at different positions of any of the sugar residues within the Oag backbone is the second type of Oag modification found in S. flexneri. Glucosylation contributes to type O-factors I, II, IV, and V, as well as the group O-factor 7,8 in various serotypes (16). The gtr operon carried by bacteriophages SfI, SfII, SfIV, SfV, and SfX caries 3 genes, gtrA, gtrB, and gtr (type specific) (22–27). In serotype 7, GlcNAc has an α-d-Glcp-(1→2)-α-d-Glcp-(1→ disaccharide which confers type O-factor VII (20, 28). The first glucosyl group addition is mediated by the gtr operon within the SfI prophage, while the second glucosyl group addition is mediated by the gtrVII (formerly known as gtrIC) gene from the novel bacteriophage SfVII (Fig. 1) (29).

The addition of PEtN at position 3 of either RhaII or RhaIII or both is the third type of Oag modification that has been identified in S. flexneri. PEtN modification confers the variant (v) factor in serotypes Xv, 4av, and Yv (30–33). The optII or optIII (Oag phosphoethalamine transferase) gene located on a plasmid (pSFxv_2 or pSFyv_2) is responsible for PEtN modification (31–33).

Two types of Oag modifications have been reported in S. flexneri 2457T serotype 2a2 (34, 35): 3/4-O-acetylation on RhaIII (confers group O-factor 9) and 6-O-acetylation on GlcNAc (confers group O-factor 10), by oacB and oacD, respectively, and glucosylation on RhaI at position 4 by the gtr (gtrII gtrB gtrA) operon (confers type O-factor II) (Fig. 1). Therefore, the antigenic formula of S. flexneri 2457T (2a2) is designated [II:9;10] (5). The degrees of 3/4-O-acetylation (30 to 70% at position 3 and 15 to 30% at position 4) on RhaIII and 6-O-acetylation (30 to 75%) on GlcNAc vary among different strains and can be affected by storage and cultivation conditions (5). In serotype 2a strains, the SfII prophage, which carries both the gtr locus and oacD, is inserted between proA and adrA, while the oacB gene, which is flanked by integrase and insertion sequences, is located upstream of adrA (5, 17).

LPS Oag acts as a virulence factor and plays important roles in S. flexneri pathogenesis. LPS provides resistance to serum complement, promotes adherence to and invasion of host cells, and, most recently discovered, prevents apoptosis of host cells by inhibiting effector caspases (36–39). Oag modification (glucosylation) has previously been reported to enhance virulence of S. flexneri M90T (5a) (36). Serotype conversion or Oag modification confers immune avoidance by S. flexneri (40).

Serotype conversion of S. flexneri is linked to the serotype-converting bacteriophages, such as SfI, SfII, Sf6, SfIV, SfV, and SfX which can convert serotype Y to serotypes 1a, 2a, 3b, 4a, 5a, and X, respectively (41). Bacteriophages utilize the Oag as a receptor to initiate infection and subsequently introduce the Oag modification genes into the host, giving rise to new serotypes and potentially resistance to bacteriophages using the same receptor. In addition to bacteriophage infection and acquisition of plasmids, S. flexneri can evolve via other horizontal gene transfers, such as acquisition of transposons and pathogenicity islands (42).

Bacteriophage Sf6 is a Shigella-specific temperate bacteriophage that infects serotypes X and Y. The oacA gene carried by Sf6 is sufficient to convert serotypes X, Y, 1a, and 4a into serotypes 3a, 3b, 1b, and 4b, respectively (17, 43). Sf6 belongs to the family Podoviridae. Sf6 tailspike protein (Sf6TSP) possesses endo-1,3-α-l-rhamnosidase (endorhamnosidase) activity, binds to the Oag repeat units reversibly, and cleaves the 1,3-α-linkage between the RhaII and RhaI residues in the repeating unit of the Oag, releasing an octasaccharide product (44, 45). Hydrolysis of Oag repeat units brings Sf6 closer to the surface of S. flexneri. Sf6 then binds to OmpA/OmpC (secondary receptor) on the outer membrane and establishes irreversible binding (46).

Presently, there is a lack of a comprehensive study that compares both the parent and serotype variant strains from the same genetic background. Therefore, S. flexneri 2457T serotype 2a2 was used to generate a set of isogenic mutants that are deficient in combinations of Oag modifications (glucosylation and/or O-acetylation) in this study. These isogenic mutants resemble different naturally occurring serotype Y and 2a strains. We determined the impact of the Oag acetylations and glucosylation on S. flexneri 2457T susceptibility to infection by Sf6 and on pathogenesis-related properties. We found that O-acetylation had a dramatic effect on Sf6 sensitivity and receptor activity but had little or no impact on invasion. This contributes to our understanding of the pathways of S. flexneri serotype evolution.

RESULTS

Construction of S. flexneri O antigen modification gene deletion mutants.

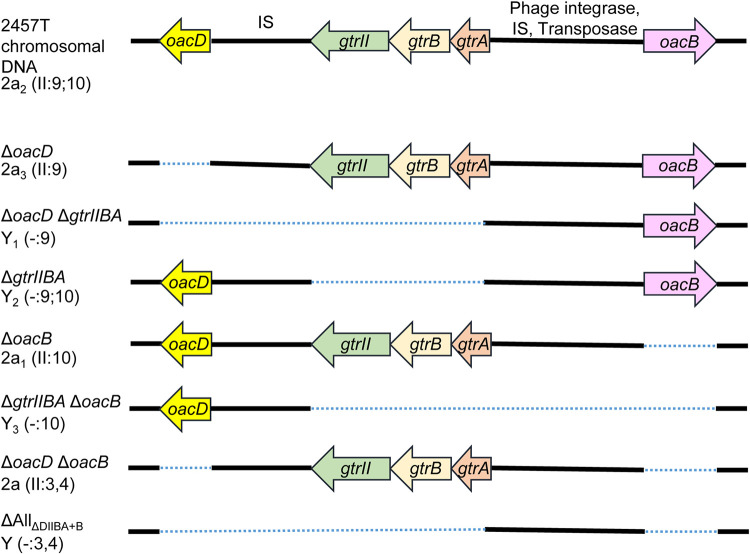

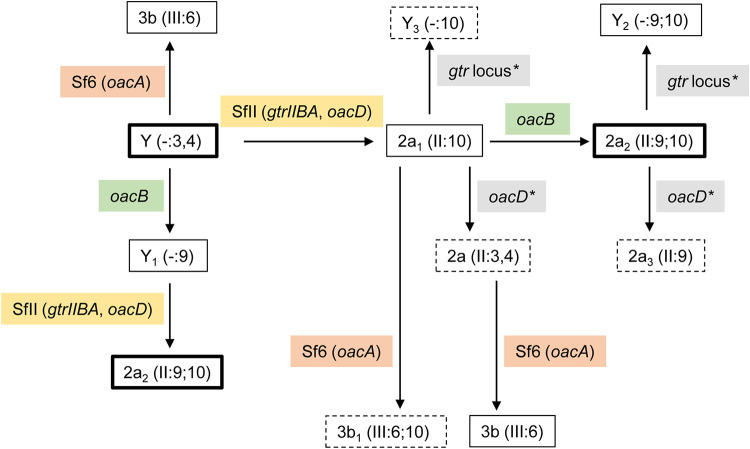

S. flexneri 2457T (2a2) was used as the parent strain in this study. Different combinations of gene deletions (oacB, oacD, and gtrIIBA) were performed using lambda Red mutagenesis to create a set of isogenic strains that are defective in combinations of Oag modifications. A total of 7 isogenic strains were created (Fig. 2). Primers used are summarized in Table S2 in the supplemental material. All serotype Y and 2a strains used in this study contain group O-factor 3,4 but this is omitted from the antigenic formula when either group O-factor 9 or 10 is present. All isogenic strains are addressed with their genotypes in this context, and the respective strain names are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

FIG 2.

Schematic diagram of various S. flexneri isogenic strains. Serotypes shown are both internationally approved and provisional, based on O antigen modifications such as O-acetylation (by oacD or oacB) and glucosylation (by gtrII). A dotted line represents the extent of the deleted region. IS, insertion sequence.

The serotypes (or provisional serotypes) for each isogenic strain and their Oag modifications are illustrated in Table 1. The oacD gene was reported to be conserved in S. flexneri 2a strains. This is due to the integration of the serotype-converting bacteriophage SfII, which carries both the gtrII locus and oacD into the chromosome of S. flexneri (18). The mutant strain with all O modification genes deleted was made by deleting the oacB gene of the ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA mutant, yielding the mutant strain ΔAllΔDIIBA+B, which has a serotype designation of “Y.”

TABLE 1.

O antigen structure of various S. flexneri serotypes

| Serotype (antigenic formula)a | O antigen structureb | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Y (-:3,4) |  |

11, 33 |

| Y2 (-:9;10) |  |

14 |

| Y1 (-:9) |  |

5 |

| Y3 (-:10)c |  |

This study |

| 2a2 (II:9;10) |  |

34, 35 |

| 2a1 (II:10) |  |

51 |

| 2a3 (II:9)c |  |

This study |

| 2a (II:3,4)c |  |

This study |

The serotypes shown are both internationally approved and provisional, based on O antigen modifications such as O-acetylation (on N-acetylglucosamine [GlcNAc] or rhamnose III [RhaIII]) and glucosylation (on rhamnose I [RhaI]). For the antigenic formulae, type and group O-factors are represented in Roman and Arabic numerals, respectively, separated by a colon. All serotypes contain group O-factor 3,4, but this is omitted from antigenic formula when group O-factor 9 or 10 is present.

O-acetylation on RhaIII and GlcNAc is nonstoichiometric. A minor 4-O-acetylation on RhaIII is not shown.

Provisional serotype that has not been reported previously.

Several of the created isogenic strains resemble different naturally occurring serotype Y and 2a strains that have either acquired or lost certain LPS Oag modification genes, as indicated in Table 1. S. flexneri serotype Y3 (ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB), 2a3 (ΔoacD), and 2a (ΔoacD ΔoacB) strains have not been identified or reported in nature and hence are given a provisional serotype.

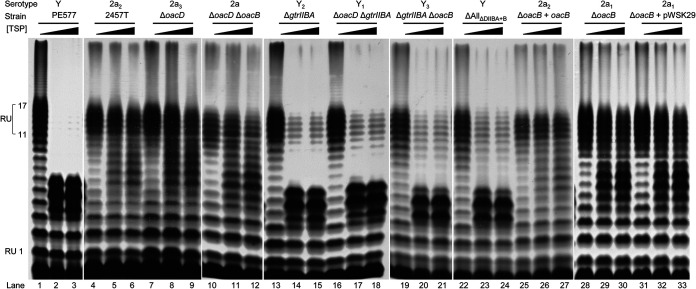

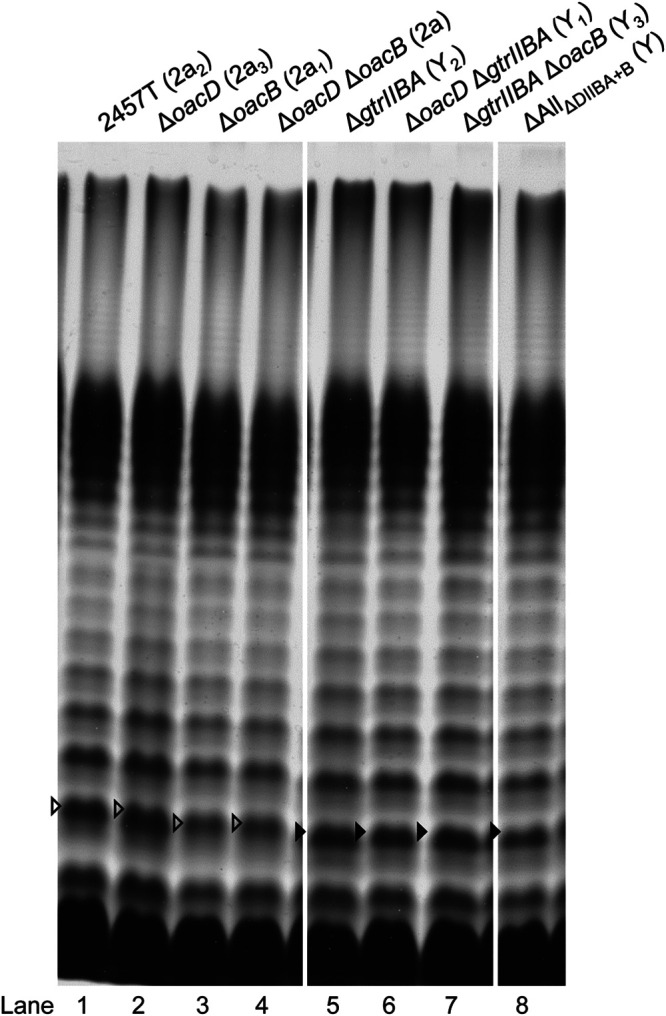

LPS profiles of S. flexneri mutants defective in O antigen modifications.

The LPS profiles of various 2457T-derived isogenic mutant strains were determined via LPS SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Fig. 3). All strains displayed smooth LPS profiles, and strains with gtrIIBA deletion had a shift in the Oag band size, as indicated by the filled arrowheads in Fig. 3 (lanes 5 to 8), in comparison to the LPS profile of S. flexneri 2457T (2a2) (Fig. 3, lane 1). This corresponds to the loss of glucosylation on the RhaI residue (Table 1). In addition, the Oag polysaccharides of the various isogenic S. flexneri strains were checked by two-dimensional 1H,13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to differentiate between serotypes 2a and Y, which readily can be done due to the presence or absence of the side chain glucosyl residue in the former (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (35, 47). The results from the NMR analysis confirm whether gtrIIBA was kept and expressed or was absent in the genetic constructs. Slide agglutination was also performed using anti-type II antiserum, which agglutinates serotype 2a strains, to confirm the loss of glucosylation in gtrIIBA-deleted strains (data not shown). Strains that do not have the gtrIIBA operon did not agglutinate. As expected, all strains in this study agglutinated with anti-group 3,4 antiserum (data not shown), which reacts with a common epitope on the Oag of all Y serotype strains.

FIG 3.

LPS profiles of various S. flexneri isogenic strains. S. flexneri strains were grown for 4 h at 37°C with aeration, followed by LPS sample preparation and SDS-PAGE and LPS silver staining as described in Materials and Methods. The open arrowheads indicate the higher-molecular-weight Oag repeat unit due to glucosylation on RhaI, while the filled arrowheads indicate the Oag repeat unit of serotype Y strains that does not have modification on RhaI. Serotypes are indicated in parentheses.

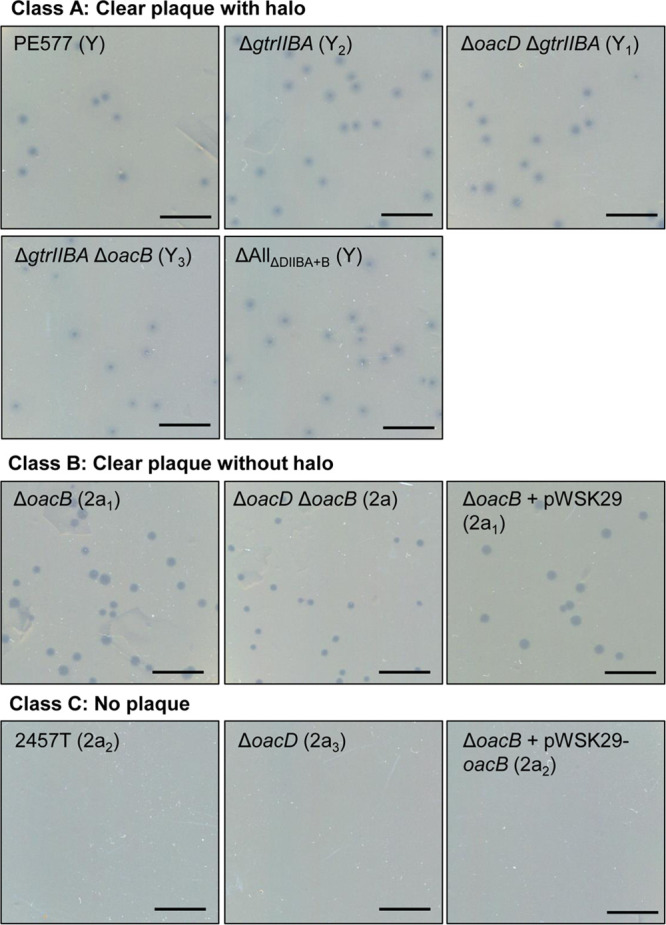

Bacteriophage Sf6c infection.

The isogenic 2457T-derived strains created in this study were used in bacteriophage Sf6c plaque assays to examine the effect of Oag modification on Sf6c recognition and infection. Figure 4 shows the results of plaque formation after infecting each strain with Sf6c. The Sf6c plaque assay results can be divided into three classes: class A, clear plaque with halo; class B, clear plaque without halo; and class C, no plaque formation. The plaque formation results are summarized in Table 2.

FIG 4.

Sensitivity of various S. flexneri mutants to Sf6c phage. For bacteriophage Sf6c plaque assay, 100 μl of overnight cultures of various S. flexneri isogenic strains was incubated with 100 μl Sf6c phage (10−8), followed by the addition of 3 ml of soft LB agar, and overlaid on 25-ml LB agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. Serotypes are indicated in parentheses. Shigella strains were classified into three classes according to three phenotypes: class A, clear plaque with halo; class B, clear plaque without halo; class C, no plaque. Scale bars, 10 mm.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity of strains created in this study to Sf6c infection

| Strain | Complementation | Serotype (antigenic formula)a | Sf6c plaque formation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE577 | Y (-:3,4) | +b | |

| 2457T | 2a2 (II:9;10) | Resistant | |

| ΔoacB mutant | 2a1 (II:10) | + | |

| ΔoacD mutant | 2a3 (II:9) | Resistant | |

| ΔoacD ΔoacB mutant | 2a (II:3,4) | + | |

| ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA mutant | Y1 (-:9) | + | |

| ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB mutant | Y3 (-:10) | + | |

| ΔgtrIIBA mutant | Y2 (-:9;10) | + | |

| ΔAllΔDIIBA+B mutant | Y (-:3,4) | + | |

| ΔoacB mutant | pWSK29 | 2a1 (II:10) | + |

| pWSK29-oacB | 2a2 (II:9;10) | Resistant | |

| ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA mutant | pBCKS+ | Y1 (-:9) | + |

| pBCKS+-gtrIIBA | 2a3 (II:9) | Resistant | |

| ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB mutant | pBCKS+ | Y3 (-:10) | + |

| pBCKS+-gtrIIBA | 2a1 (II:10) | + | |

| ΔgtrIIBA mutant | pBCKS+ | Y2 (-:9;10) | + |

| pBCKS+-gtrIIBA | 2a2 (II:9;10) | Resistant | |

| ΔAllΔDIIBA+B mutant | pBCKS+ | Y (-:3,4) | + |

| pBCKS+-gtrIIBA | 2a (II:3,4) | + |

All strains in this table have the group O-factor 3,4, but this is omitted when group O-factor 9 or 10 antigen is shown.

+, sensitive to Sf6c and formed plaques.

As expected, PE577 (serotype Y control strain) and any serotype Y isogenic strain derived from 2457T that has the gtrIIBA operon deleted (ΔgtrIIBA, ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA, ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB, and ΔAllΔDIIBA+B) were sensitive to Sf6c and formed plaques with halos, albeit with different plaque morphology. These strains are categorized under class A (Fig. 4).

Members of class B are comprised of type II strains such as the ΔoacB (2a1), ΔoacB complemented with pWSK29 empty vector (2a1), and ΔoacD ΔoacB (2a) strains. Sf6c formed clear plaques without a halo on these strains (Fig. 4), which is different from class A. This is a surprising and novel result because Sf6c has never been reported to infect a type II strain before. As expected, the pWSK29-complemented ΔoacB strain showed the same phenotype as the ΔoacB strain. Class C members are comprised of type II strains such as the 2457T wild-type strain (2a2) and the ΔoacD (2a3) and ΔoacB complemented with pWSK29-oacB (2a2) strains. These strains were resistant to Sf6c and were not permissive for plaque formation (Fig. 4). Complementation of oacB in the ΔoacB mutant was successful, as this reverted its serotype from 2a1 to 2a2 (resembles the parent strain 2457T) and restored its resistance to Sf6c.

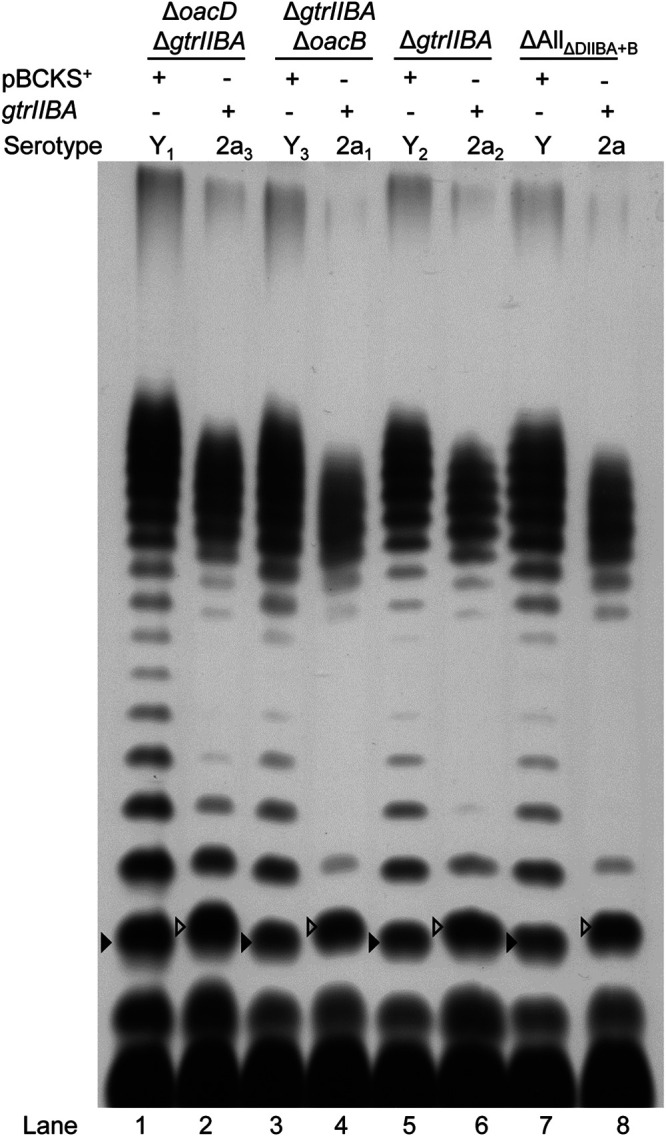

Isogenic strains from class A were subsequently complemented with pRMM264 (pBCKS+-gtrIIBA) (22) or pBCKS+ empty vector. Slide agglutination confirmed that the gtrIIBA-complemented strains were successfully converted into type II (Table 2). This is supported by analysis of their LPSs by SDS-PAGE and silver staining, which showed that the LPS Oag band size was shifted back to that of the 2a LPS profile (Fig. 5). Both ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA and ΔgtrIIBA strains complemented with the gtrIIBA operon became resistant to Sf6c infection, which is consistent with the ΔoacD (2a3) and 2457T wild-type (2a2) strains (Table 2). In contrast, ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB and ΔAllΔDIIBA+B strains complemented with the gtrIIBA operon remained sensitive to Sf6c infection, which is consistent with ΔoacB (2a1) and ΔoacD ΔoacB (2a) (Table 2). The pBCKS+-complemented strains had the same phenotypes as the noncomplemented strains.

FIG 5.

Complementation of the gtrIIBA operon in S. flexneri isogenic strains. LPS profiles of S. flexneri isogenic strains (ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA, ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB, ΔgtrIIBA, and ΔAllΔDIIBA+B) complemented with the gtrIIBA operon encoded on pRMM264 or pBCKS+ empty plasmid are shown. S. flexneri strains were grown for 4 h at 37°C with aeration, followed by LPS sample preparation and SDS-PAGE and LPS silver staining as described in Materials and Methods. The open arrowheads indicate the shift in Oag repeat unit size due to glucosylation on residue RhaI.

Collectively, Sf6c is capable of infecting various serotype Y isogenic strains, regardless of the acetylation of Oag status, and for the first time we find that strains with serotypes 2a [II:3,4] (missing O-factors 9 and 10 as determined by oacB and oacD, respectively) and 2a1 [II:10] (missing O-factor 9) are vulnerable to bacteriophage Sf6c infection. The presence of glucosylation alone is insufficient to prevent Sf6c infection (as shown by serotype 2a and 2a1 strains), and 3/4-O-acetylation of RhaIII mediated by the oacB gene is required.

Sf6TSP-mediated LPS hydrolysis.

As Sf6 uses its TSP for initial interaction with Oag, we investigated its activity on the LPS Oag produced by the Oag modification mutant strains detailed above. Purified Sf6TSP protein at increasing concentrations was incubated with various isogenic strains, and their resulting LPS profiles were determined by LPS silver staining (Fig. 6). The untreated and Sf6TSP-treated LPS Oags (repeat units 11 to 17) of each strain in Fig. 6 were quantified by densitometry, and the results are presented as a percentage of LPS hydrolysis/reduction in Table 3. In general, the LPS Oags of all strains tested were either partially (>50%) or modestly (>15%) hydrolyzed by Sf6TSP. Among those whose LPS Oags were partially hydrolyzed (Fig. 6, lanes 14 and 15, lanes 17 and 18, lanes 20 and 21, and lanes 23 and 24), two types of LPS hydrolysis profile were observed. All were serotype Y variant strains that belong to class A which had plaques with halos upon infected with Sf6c (Fig. 4). These strains were further classified as class A1 or A2, based on the LPS hydrolysis profiles (Table 3).

FIG 6.

LPS profiles of various S. flexneri isogenic strains after hydrolysis with different concentrations of purified Sf6TSP. Overnight cultures of various S. flexneri strains were formalin fixed for 45 min at RT, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in 40 μl of Sf6TSP (22 ng/ml and 44 ng/ml) in PBS or in PBS alone (no-Sf6TSP control). The bacterial and Sf6TSP mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, washed twice with Milli-Q water, and resuspended in 50 μl lysis buffer. LPS samples were subsequently prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and LPS silver staining as described in Materials and Methods. RU, repeat unit.

TABLE 3.

Classification of various S. flexneri isogenic strains based on LPS O antigen profiles after treatment with Sf6TSP

| Classa | Strain | Serotype | Major hydrolyzed LPS RUs | % of LPS hydrolysisb,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1b | PE577 | Y | 5–6 | >99 |

| ΔgtrIIBA mutant | Y2 | >65 | ||

| ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA mutant | Y1 | >60 | ||

| A2b | ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB mutant | Y3 | 4–5 | >50 |

| ΔAllΔDIIBA+B mutant | Y | >60 | ||

| B | ΔoacB mutant | 2a1 | 5–8 | >30 |

| ΔoacD ΔoacB mutant | 2a | >20 | ||

| ΔoacB mutant + pWSK29 | 2a1 | >30 | ||

| C | 2457T mutant | 2a2 | 6–9 | >20 |

| ΔoacD mutant | 2a3 | >15 | ||

| ΔoacB mutant + pWSK29-oacB | 2a2 | >15 |

Based on Sf6c plaque assay.

Based on LPS profile on silver-stained SDS-PAGE.

Densitometry measurement of LPS Oag repeat units 11 to 17 using ImageLab 6.1 (Bio-Rad) and normalized to untreated sample.

The PE577, ΔgtrIIBA, and ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA strains had LPS whose Oag chains had approximately 5 to 6 repeat units after Sf6TSP treatment (Fig. 6) and are classified under class A1 (Table 3). However, only PE577 showed complete (>99%) LPS Oag hydrolysis (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 3) while the ΔgtrIIBA and ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA strains had LPS profiles indicating that hydrolysis was incomplete (>65% and >60%, respectively) (Fig. 6, lanes 14 and 15 and lanes 17 and 18, respectively). The ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB and ΔAllΔDIIBA+B strains are under class A2 (Table 3). These strains had LPS whose Oag chains had approximately 4 or 5 repeat units after Sf6TSP treatment and also exhibited incomplete LPS hydrolysis (>50% and >60%, respectively) (Fig. 6, lanes 20 and 21 and lanes 23 and 24). It has previously been shown that Sf6TSP cleavage of S. flexneri PE577 LPS resulted in LPS with approximately 5 tetrasaccharide repeat units (45). Our results are consistent with that report.

The strains with modest hydrolysis of LPS Oags are members of class B and class C, which are type II strains (Table 3). Class B members, the ΔoacB, ΔoacD ΔoacB, and ΔoacB+pWSK29 strains, had 5 to 8 repeat units as major products after Sf6TSP treatment, with LPS hydrolysis of >30%, >20%, and >30%, respectively (Fig. 6, lanes 29 and 30, lanes 11 and 12, and lanes 32 and 33, respectively). The reduced level of LPS hydrolysis is an unexpected result, as Sf6c formed large clear plaques on class B members and hence their LPS Oags were predicted to be more extensively hydrolyzed by Sf6TSP. Interestingly, the LPS Oag of class C members (the 2457T, ΔoacD, and ΔoacB+pWSK29-oacB strains) which were resistant to Sf6c infection (Fig. 4) exhibited a low level of hydrolysis by Sf6TSP (>20% and >15%, respectively), and LPS with 6 to 9 Oag repeat units was detected after Sf6TSP treatment (Fig. 6, lanes 5 and 6, lanes 8 and 9, and lanes 29 and 30). The degree of LPS hydrolysis for class B members is slightly higher than that for the class C members, as shown in Table 3. Notably, the LPS Oag hydrolysis detected for class B and class C members was Sf6TSP dose dependent.

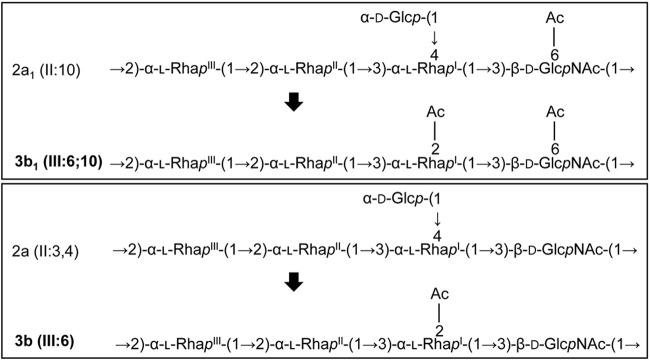

Serotype 2a1 and 2a strains are converted into serotype 3b1 and 3b by lysogenic Sf6.

As we have shown that serotype 2a1 (ΔoacB) and 2a (ΔoacD ΔoacB) strains were susceptible to Sf6c infection, we hypothesized that these strains are also sensitive to lysogenic Sf6 and that the lysogens formed will undergo serotype conversion as a result of incorporation of the Sf6 genome. PE577 has previously been shown to form lysogens by Sf6 and converted its serotype from Y to 3b (48). Hence, PE577 was included as a serotype conversion control in this assay. S. flexneri 2457T (2a2), which is resistant to Sf6 infection, was not included in this assay. Sf6 lysogens of the ΔoacB, ΔoacD ΔoacB, and PE577 strains were isolated as described in Materials and Methods. PCR was performed on these strains to screen for the presence of the Sf6 tailspike protein gene (gp14) (data not shown), which indicates the integration of the Sf6 genome in the lysogens.

Slide agglutination assays were performed to confirm serotype conversion. All three lysogens agglutinated strongly with anti-group 6 antiserum (which detects 2-O-acetylation on RhaI that is mediated by the oacA gene carried by Sf6) but did not agglutinate with anti-type II (Table 4). These data indicate that ΔoacB (Sf6), ΔoacD ΔoacB (Sf6), and PE577 (Sf6) lysogens have undergone serotype conversion from serotype 2a1 [II:10], 2a [II:3,4], and Y [-:3,4] to 3b1 [III:6;10], 3b [III:6], and 3b [III:6], respectively. Notably, the ΔoacB (Sf6) lysogen retained a weak reactivity, while the ΔoacD ΔoacB (Sf6) and PE577 (Sf6) lysogens did not agglutinate with anti-group 3,4. Serotype conversion of 2a1 and 2a into 3b1 and 3b is illustrated in Fig. 7.

TABLE 4.

Agglutination reactions of Sf6 lysogens

| Strain | Serotype | Antigenic formula | Agglutinationc

with: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-type II | Anti-group 6 | |||

| ΔoacB mutant | 2a1 | II:10a | +++ | − |

| ΔoacD ΔoacB mutant | 2a | II:3,4 | +++ | − |

| PE577 | Y | -:3,4 | − | − |

| ΔoacB (Sf6) mutant | 3b1 | III:6;10a | − | +++ |

| ΔoacD ΔoacB (Sf6) mutant | 3b | III:6b | − | +++ |

| PE577 (Sf6) | 3b | III:6b | − | +++ |

This strain has group O-factor 3,4.

This strain does not have group O-factor 3,4.

+++, 100% agglutination; −, no agglutination.

FIG 7.

Serotype conversion of 2a1 and 2a strains into 3b1 and 3b. Serotype conversion of S. flexneri as a result of incorporation of the Sf6 genome is shown. OacA adds an acetyl group at position 2 of RhaI, which competes with GtrII that adds a glucosyl group at position 4 of RhaI.

This study shows for the first time that type II strains can be converted into type III by bacteriophage Sf6 and identifies serotype 3b1 [III:6;10] as a new subserotype.

Effect of LPS O antigen modifications on S. flexneri cell invasion.

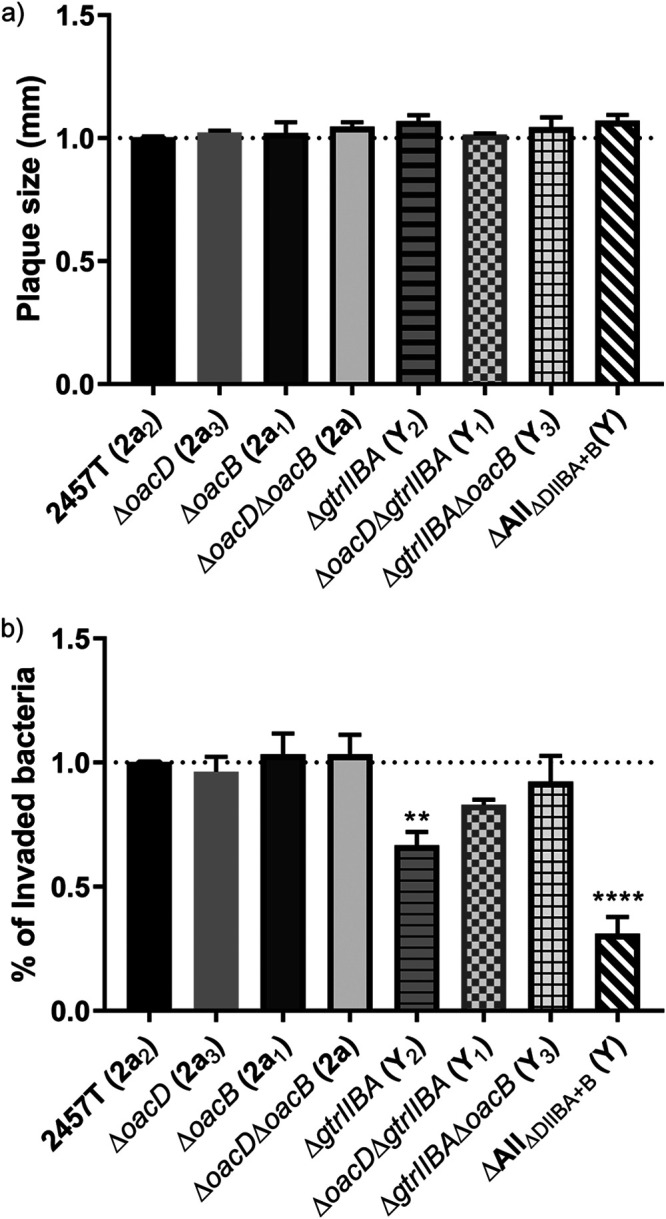

We and others (36, 37, 49, 50) have shown that Oag has a role in S. flexneri adherence and invasion of human cells, with Oag glucosylation affecting the latter (36). We therefore investigated the effect of Oag modifications on cell invasion and cell-to-cell spread by S. flexneri. Initially, HeLa cell plaque assays were performed. The results showed that all strains formed plaques of similar size (Fig. 8a), suggesting that their actin-based motility is not affected.

FIG 8.

Characterization of the invasion ability of various S. flexneri isogenic strains. HeLa cell plaque (a) and invasion (b) assays were performed using virulent S. flexneri isogenic strains. (a) Confluent HeLa cell monolayers were infected with mid-log-phase S. flexneri strains for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, and plaques were observed at 48 h postinfection. The plaque size of each strain was normalized to that of 2457T. (b) Semiconfluent HeLa cell monolayers were infected with mid-log-phase S. flexneri strains at an MOI of 300, spun at 2,000 rpm for 7 min, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 60 min. Infected monolayers were washed thrice with Dulbecco’s PBS, followed by the addition of MEM supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) FCS and 40 μg/ml gentamicin and incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 90 min. Infected HeLa cells were washed thrice with PBS and lysed with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS. Viable counts were performed by plating onto LB agar plates, and results are presented as percentage of invaded bacteria normalized to 2457T. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to perform statistical analysis. **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

HeLa cells invasion assays were then performed to examine if there was any variation in invasion ability between the serotype-modified mutants. In general, the Y serotype strains showed a reduction in invasion. ΔAllΔDIIBA+B (Y) in particular showed significantly reduced invasion ability (P ≤ 0.0001; 0.7-fold reduction) compared with that of S. flexneri 2457T (2a2) (Fig. 8b). In addition, ΔgtrIIBA (Y2) also has a slight reduction in invasion ability (P ≤ 0.01; 0.3-fold reduction). All serotype 2a strains showed a similar level of invasion (Fig. 8b).

Our data showed that structural modification of LPS Oag can affect the invasion ability of S. flexneri but showed no effect on cell-to-cell spreading ability as detected in the assay used.

DISCUSSION

In the past, studies of LPS Oag modifications have always been performed serologically, chemically, and genetically on strains from various sources (5, 35, 41, 51). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive study on both parent and serotype variant strains from the same genetic background. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of LPS Oag modifications such as glucosylation and O-acetylation on S. flexneri sensitivity to bacteriophage Sf6c and its pathogenesis-related properties (invasion and cell-to-cell spread) in a set of isogenic strains. S. flexneri 2457T 2a2, which contains three types of identified LPS Oag modification genes (oacB, oacD, and the gtrIIBA operon), was used as a parent strain, and those genes were deleted in different combinations. As a result, the S. flexneri 2457T 2a2 strain was converted into subserotype or serotype 2a1, 2a3, 2a, Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y (Fig. 2). This allows direct comparison of isogenic strains in terms of their pathogenicity and the understanding of evolution of S. flexneri from serotype Y to 2a by acquiring Oag modification genes, which may provide benefits to the bacteria (36).

We showed that isogenic mutant strains with different Oag modifications reacted differently to Sf6c infection and Sf6TSP-mediated LPS Oag hydrolysis. All class A members (serotype Y) formed Sf6c plaques with halos and had two types of LPS hydrolysis profiles after being treated with Sf6TSP. It has recently been reported that O-acetylation and/or glucosylation on the highly flexible serotype Y backbone caused the S. flexneri Oag molecule to adopt different conformations (52). This may explain the production of two different LPS hydrolysis profiles among the class A members, whereby the pattern of cleavage activity of Sf6TSP is affected. It is unknown why the created serotype Y isogenic strains (including AllΔDIIBA+B [Y] with all Oag modification genes deleted) could not achieve complete Sf6-mediated LPS Oag hydrolysis as seen with strain PE577. Analysis of the PE577 genomic sequence (accession number NZ_CP042980.1) indicates that this strain does not have any of the known Oag modification genes in its genome. We speculate that there is an unknown factor in S. flexneri 2457T (2a2) which is preventing the LPS Oag from being completely hydrolyzed by Sf6TSP.

Excitingly, for the first time we provided molecular evidence that serotype 2a1 (ΔoacB) and 2a (ΔoacD ΔoacB) strains, which lack either 3/4-O-acetylation or both 3/4- and 6-O-acetylations, respectively, were highly sensitive to Sf6c even though their LPS Oags were not as sensitive to Sf6TSP cleavage as those of serotype Y strains (class A). LPS Oags of all serotype 2a isogenic strains created in this study (both class B and class C) were only modestly hydrolyzed by Sf6TSP in a dose-dependent manner.

The importance of 3/4-O-acetylation on RhaIII to S. flexneri serotype 2a strains was reflected by the complementation of oacB in the ΔoacB strain, which became resistant to Sf6c (Fig. 4). This suggests that the acquisition of the oacB gene in S. flexneri serotype 2a strains provides an enormous protective advantage to these strains in nature, and hence, most of the tested serotype 2a strains possess this gene (17, 34, 35). Our data showed that serotype Y1 and Y2 strains which contain the oacB gene were susceptible to Sf6c infection. This implies that the presence of the oacB gene (3/4-O-acetylation of RhaIII) can provide protection only when the gtr locus (glucosylation of RhaI) is present. Glucosylation of RhaI is insufficient to prevent Sf6c infection when 3/4-O-acetylation is absent. This finding is further supported by the gtrIIBA complementation in ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB and AllΔDIIBA+B strains, as the complemented strains were still susceptible to Sf6c infection (Table 2).

Class B and class C members had modest LPS Oag hydrolysis (Table 3). This could be due to a conformation change in LPS Oags which affects the cleavage activity of Sf6TSP, as mentioned above. This also implies that Sf6TSP has low binding affinity and low cleavage activity to serotype 2a LPS Oag chains. This is consistent with a recently reported matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry study showing that Sf6TSP binds to serotype 2a2 LPS weakly and cleaves the 2a2 LPS Oag (53). Therefore, we speculate that the formation of clear plaques without halos on ΔoacB and ΔoacD ΔoacB strains could be due to a lower rate of infection by Sf6c. The formation of a plaque with a halo in serotype Y strains could be due to rapid killing of bacteria by Sf6c released from lysed bacteria. Alternatively, the formation of a halo can be due to diffusion of metabolic products or phage lysozyme.

A recent molecular dynamics simulation study showed that a serotype 2a3 LPS with 3/4-O-acetylation (resembles ΔoacD LPS) formed a more stable helix conformation, while serotype 2a LPS without O-acetylation (resembles ΔoacD ΔoacB LPS) formed a flexible C-curve conformation (52). We speculate that ΔoacB LPS Oag, which contains 6-O-acetylation, will be most likely adopting a C-curve conformation, as the ΔoacB and ΔoacD ΔoacB strains share similar phenotypes. However, this requires further confirmation. The formation of a C-curve LPS structure as a result of glucosylation might form a more compact and shorter LPS structure on the bacterial surface, as shown by S. flexneri M90T (serotype 5a) (36). S. flexneri M90T LPS Oag chains lack O-acetylation but contain glucosylation on RhaII residues (51). Despite weak interaction between Sf6c and serotype 2a strains, the flexible C-curve and shorter LPS conformation of S. flexneri lacking the oacB gene may facilitate infection by Sf6c without needing extensive LPS Oag hydrolysis. Recently, it was reported that the T5-like bacteriophages DT57C and DT571/2 are able to penetrate through the Oag layer and bind to the secondary receptor in Escherichia coli 4s without hydrolyzing LPS Oags (54). Therefore, Sf6c may have the ability to penetrate the Oag layer when 3/4-O-acetylation of RhaIII is absent. The detailed mechanism employed by Sf6c to infect S. flexneri serotype 2a strains lacking the oacB gene remains to be elucidated.

The effect of LPS Oag modification on S. flexneri cell invasion and spread was investigated. Our invasion assay results showed that all serotype 2a strains were more invasive than serotype Y strains. This is consistent with the data of West et al. (36). Notably, ΔAllΔDIIBA+B is the least invasive strain, compared to other isogenic serotype Y strains. This suggests that chemical modifications of serotype Y LPS Oag may have some effects on their invasion ability that are positive but weaker than that seen with serotype 2a strains. On the other hand, O-acetylation of LPS Oag does not have a significant effect on the invasion ability of serotype 2a strains, as all serotype 2a isogenic strains have invasive levels similar to that of the parent strain. Furthermore, the actin-based motility and cell-to-cell spreading of various isogenic strains as detected by plaque assays were not affected by chemical modifications of LPS Oag, as all strains tested formed plaques of similar size on HeLa cells.

The results indicate that Oag modifications have subtle effects on interaction of S. flexneri with human cells which in some cases may result in variants such as the 2a serotype that are selected in human populations and become predominant. Collectively, our data demonstrated that serotype 2a strains (regardless of subserotype) are more invasive than serotype Y strains, consistent with serotype 2a being the most prevalent serotype in developing countries.

We found that the ΔoacD strain (2a3) has a phenotype almost identical to that of the parent S. flexneri 2457T (2a2), indicating that the function of 6-O-acetylation (O-factor 10) on GlcNAc is not important for protection from Sf6c infection, LPS hydrolysis by Sf6TSP, and S. flexneri pathogenesis. Coincidently, a previous study reported that 6-O-acetylation (O-factor 10) on a synthetic serotype 2a LPS Oag had little effect on S. flexneri 2a-specific monoclonal antibody binding, suggesting that the epitope of O-factor 10 is not essential for antigenicity (55). Collectively, the results indicate that 6-O-acetylation on GlcNAc does not affect Oag interaction with proteins (TSP and antibodies). Nevertheless, O-factor 10 contributes to the diversities of S. flexneri Oag reservoirs and is immunogenic, as anti-O-factor 10 antibody could be affinity purified from polyclonal antisera (18).

Our study included the investigation of potential intermediate serotypes during serotype conversion from Y to 2a2, and the pathways of serotype conversions are summarized in Fig. 9. The sequence of Oag modification gene acquisition (oacB and SfII prophage) in S. flexneri serotype Y is unknown. Hence, two pathways of serotype conversions are illustrated.

FIG 9.

Serotype conversion pathways of S. flexneri. Serotype conversions mediated by bacteriophages SfII and Sf6 are highlighted in yellow and pink boxes, respectively. Serotype conversion mediated by the oacB transposon-like mobile element is highlighted in green boxes. Gene mutations are marked with asterisks and highlighted in gray boxes. The figure is based on this study and a study by Knirel et al. (5). Serotypes that have not been identified naturally are within dashed boxes. The order of serotype conversion from Y to 2a2 is not known; hence, two separate pathways are illustrated.

We investigated if OacA encoded by Sf6 would compete with GtrII in adding an acetyl or a glucosyl group, respectively, at positions 2 and 4 of RhaI, respectively. S. flexneri serotype 2a1 and 2a lysogenized by Sf6 were converted into serotype 3b1 and 3b, respectively, as shown by the agglutination assay (Table 4). It is unclear why only the ΔoacB (Sf6) strain showed some reactivity to anti-group 3,4. A previous study reported that the Sf6 lysogen of PE577 retained some 3,4 antigenicity (48) which was not detected in PE577 (Sf6). This could be due to different sources of antisera being used and indicates that these lysogens had 2-O-acetylation on the RhaI residue when the oacA gene is present. The mechanism that results in O-acetylation being the preferable modification remains to be elucidated. This is a novel finding that showed serotype conversion from 2a to 3b, because previous studies have reported that serotype 2a can be converted into other serotypes, such as Y, Yv, and 4s (56–58), but not serotype 3b. As a result of serotype conversion mediated by oacA of Sf6, we discovered a new subserotype for S. flexneri, serotype 3b1 [III:6;10] (Fig. 7).

In conclusion, we have successfully identified two new specific forms of LPS for Sf6c binding, the LPS Oag of S. flexneri serotypes 2a1 and 2a. Our novel finding showed that the acquisition of the oacB gene is essential for Sf6c resistance but not for cell invasion by S. flexneri serotype 2a strains. On the other hand, the oacD gene does not have a significant role in either Sf6c infection or pathogenesis. Together, the importance of the oacB gene and the similar invasion abilities among serotype 2a strains may explain why serotype 2a2 is the prevalent strain in causing shigellosis. We also provided evidence that Sf6TSP is capable of detectably hydrolyzing all serotype 2a LPS Oags and that complete LPS hydrolysis of serotype 2a strains lacking the oacB gene is not required for Sf6c infection. Lastly, we demonstrated two new serotype conversions for strains converted from 2a1 [II:10] and 2a [II:3,4] into 3b1 [III:6;10] and 3b [III:6], respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Growth media and growth conditions.

All strains used in this study were routinely grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium. Virulence plasmid-positive S. flexneri strains were grown from a Congo red-positive colony as previously described (50). Bacterial cultures were cultured for 18 h, diluted 1:20, and grown to mid-exponential phase (2 h) with aeration at 37°C. Where appropriate, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; or kanamycin, 50 μg/ml.

DNA methods.

E. coli K-12 DH5α was used for all cloning. DNA manipulation, PCR, transformation, and electroporation into S. flexneri were performed as previously described (59, 60).

Constructions of various S. flexneri deletion mutants.

The S. flexneri mutants (ΔoacD, ΔoacB, ΔgtrII gtrB gtrA [ΔgtrIIBA], ΔoacD ΔgtrII gtrB gtrA [ΔoacD ΔgtrIIBA], ΔgtrII gtrB gtrA ΔoacB [ΔgtrIIBA ΔoacB], ΔoacD ΔoacB, and ΔoacD ΔgtrII gtrB gtrA ΔoacB [ΔAllΔDIIBA+B]) were constructed using lambda Red-mediated recombination as previously described (61). S. flexneri 2457T (2a2) was used as the parental strain. Primers involved in PCR amplifying the FLP recombination target (FRT)-kanamycin (Kan)-FRT cassette from pKD4 are summarized in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The resulting PCR fragments with appropriate homologous regions were then electroporated into 0.2% (wt/vol) arabinose-induced S. flexneri 2457T carrying plasmid pKD46. All mutations were confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. The Kan cassette was flipped out by introducing pCP20 into the mutant strains, leaving the FRT scar in the genome.

Construction of plasmid pWSK29-oacB.

The oacB gene together with approximately 1 kb upstream of oacB was PCR amplified using primers MY_192_oacB_SalI_F and MY_193_oacB_EcoRI_R (Table S2) from S. flexneri 2457T chromosomal DNA. The PCR product was subsequently cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) and subcloned into pWSK29 via SalI and EcoRI sites.

LPS analysis.

LPS samples and gels were prepared as described previously (62). Briefly, bacterial cultures were diluted 1:20 and grown at 37°C for 4 h. The bacterial samples were standardized to 1 × 109 bacteria/ml, resuspended in 50 μl lysis buffer, heated at 100°C for 10 min, treated with 2.5 mg/ml proteinase K (AM2542; Thermo Fisher), and incubated at 56°C for at least 4 h. The samples were then subjected to LPS SDS-PAGE and silver staining (62).

LPS hydrolysis by Sf6TSP.

Treatment with the Sf6 tailspike protein (Sf6TSP) was performed as described previously (63) with some modifications. Bacteria (1 × 109/ml) were fixed with 1% (vol/vol) formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. Formalin-fixed bacteria were washed once with PBS and incubated with purified Sf6TSP protein (64) at 37°C for 1 h. Different concentrations of Sf6TSP (0 ng/ml [control], 22 ng/ml, and 44 ng/ml) were used in the assay. The bacteria were then pelleted and washed twice with Milli-Q water. The pellets were subsequently resuspended in 50 μl lysis buffer and LPS samples prepared as described above.

HeLa cell plaque assay.

Plaque assays were performed as described previously (65) using the method of Oaks et al. (66) with some modifications. HeLa cells were grown to confluence in a 6-well tray at 37°C with 5% CO2 in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. On the day of infection, 5 × 108 mid-exponential-phase bacteria/ml were diluted 1:1,000 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), and 0.25 ml of bacterial suspension was added to each well. The 6-well tray was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and was rocked gently every 15 min. At 2 h postinfection, the bacterial inoculum was carefully aspirated, and 3 ml of the first overlay (0.5% [wt/vol] SeaKem ME agarose, DMEM, 5% [vol/vol] FCS, 20 μg/ml gentamicin) was added to each well. The second overlay (0.5% [wt/vol] SeaKem ME agarose, DMEM, 5% [vol/vol] FCS, 0.1% [wt/vol] Neutral Red [Gibco BRL]) was added at 48 h postinfection, and plaques were imaged 4 h later. The size of plaques was measured with the MetaMorph software program (version 7.7.3.0; Molecular Devices).

HeLa cell invasion assay.

Invasion assays were performed as described previously (65) with some modifications. HeLa cells were seeded at 8 × 104 cells/ml in a 24-well tray and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2. HeLa monolayer cells were infected with invasive S. flexneri strains (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 300) for 1 h, washed three times with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline, and treated with MEM supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) FCS and 40 μg/ml gentamicin for another 1.5 h. The infected monolayers were washed three times with PBS and lysed with 500 μl of 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS for 10 min at RT. Serial dilution (10−1 and 10−2) was performed, and 20 μl of bacterial suspension was spotted onto LB agar (in triplicates). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 h, and viable bacteria were counted.

Bacteriophage Sf6c plaque assay.

Sf6c (clear-plaque-forming) phage (7.2 × 1010 phage/ml) was serially 10-fold diluted to 10−8. One hundred microliters of diluted Sf6c was then mixed with 100 μl of overnight culture, prior to adding 3 ml of soft LB agar (0.75% [wt/vol] agar), and overlaid on 25 ml LB agar. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 h.

Isolation of Sf6 lysogen.

Wild-type Sf6 (5 μl) was spotted onto soft agar that contained PE577, 2457T ΔoacB, or 2457T ΔoacD ΔoacB. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Lysogens formed within the plaques were streaked onto LB agar plates three times. PCR screening was performed to confirm the incorporation of the Sf6 genome. Primers (MY_227_tsp_F and MY_199_tsp_R) (Table S2) that target the tailspike protein gene (gp14) were used in the screening. Serotype conversion of lysogens was confirmed using slide agglutination assay as described below.

Slide agglutination assay.

The serotype of Shigella was determined by slide agglutination test using a commercially available Shigella anti-type II antiserum (295019; Denka Seiken), anti-group 6 antiserum (295057; Denka Seiken), and anti-group 3,4 antiserum (294999; Denka Seiken). Briefly, bacterial colonies were obtained from LB agar plates and resuspended in 100 μl of PBS, and 10 μl of the bacterial emulsion was spotted onto a microscope slide, followed by an equal amount of antiserum. Agglutination was determined visually and by phase-contrast light microscopy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by ARC Discovery Project DP170104325, the Swedish Research Council (2017-03703), and The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, Pulcini C, Kahlmeter G, Kluytmans J, Carmeli Y, Ouellette M, Outterson K, Patel J, Cavaleri M, Cox EM, Houchens CR, Grayson ML, Hansen P, Singh N, Theuretzbacher U, Magrini N, WHO Pathogens Priority List Working Group. 2018. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil IA, Troeger C, Blacker BF, Rao PC, Brown A, Atherly DE, Brewer TG, Engmann CM, Houpt ER, Kang G, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Luby SP, MacLennan CA, Pan WK, Pavlinac PB, Platts-Mills JA, Qadri F, Riddle MS, Ryan ET, Shoultz DA, Steele AD, Walson JL, Sanders JW, Mokdad AH, Murray CJL, Hay SI, Reiner RC Jr. 2018. Morbidity and mortality due to Shigella and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Infect Dis 18:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DuPont HL, Levine MM, Hornick RB, Formal SB. 1989. Inoculum size in shigellosis and implications for expected mode of transmission. J Infect Dis 159:1126–1128. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.6.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotloff KL, Riddle MS, Platts-Mills JA, Pavlinac P, Zaidi AKM. 2018. Shigellosis. Lancet 391:801–812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knirel YA, Sun Q, Senchenkova SN, Perepelov AV, Shashkov AS, Xu J. 2015. O-antigen modifications providing antigenic diversity of Shigella flexneri and underlying genetic mechanisms. Biochemistry (Mosc) 80:901–914. doi: 10.1134/S0006297915070093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livio S, Strockbine NA, Panchalingam S, Tennant SM, Barry EM, Marohn ME, Antonio M, Hossain A, Mandomando I, Ochieng JB, Oundo JO, Qureshi S, Ramamurthy T, Tamboura B, Adegbola RA, Hossain MJ, Saha D, Sen S, Faruque AS, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Zaidi AK, Sur D, Sow SO, Berkeley LY, O'Reilly CE, Mintz ED, Biswas K, Cohen D, Farag TH, Nasrin D, Wu Y, Blackwelder WC, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Levine MM. 2014. Shigella isolates from the global enteric multicenter study inform vaccine development. Clin Infect Dis 59:933–941. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindberg AA, Karnell A, Weintraub A. 1991. The lipopolysaccharide of Shigella bacteria as a virulence factor. Rev Infect Dis 13(Suppl 4):S279–S284. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_4.s279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ram PK, Crump JA, Gupta SK, Miller MA, Mintz ED. 2008. Analysis of data gaps pertaining to Shigella infections in low and medium human development index countries, 1984–2005. Epidemiol Infect 136:577–603. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807009351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye C, Lan R, Xia S, Zhang J, Sun Q, Zhang S, Jing H, Wang L, Li Z, Zhou Z, Zhao A, Cui Z, Cao J, Jin D, Huang L, Wang Y, Luo X, Bai X, Wang Y, Wang P, Xu Q, Xu J. 2010. Emergence of a new multidrug-resistant serotype X variant in an epidemic clone of Shigella flexneri. J Clin Microbiol 48:419–426. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00614-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Seidlein L, Kim DR, Ali M, Lee H, Wang X, Thiem VD, Canh DG, Chaicumpa W, Agtini MD, Hossain A, Bhutta ZA, Mason C, Sethabutr O, Talukder K, Nair GB, Deen JL, Kotloff K, Clemens J. 2006. A multicentre study of Shigella diarrhoea in six Asian countries: disease burden, clinical manifestations, and microbiology. PLoS Med 3:e353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenne L, Lindberg B, Petersson K. 1977. Basic structure of the oligosaccharide repeating-unit of the Shigella flexneri O-antigens. Carbohydr Res 56:363–370. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)83357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd JS. 1938. The antigenic structure of the mannitol-fermenting group of dysentery bacilli. J Hyg (Lond) 38:477–499. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400011335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlin NI, Rahman M, Sack DA, Zaman A, Kay B, Lindberg AA. 1989. Use of monoclonal antibodies to type Shigella flexneri in Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol 27:1163–1166. doi: 10.1128/JCM.27.6.1163-1166.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perepelov AV, Shekht ME, Liu B, Shevelev SD, Ledov VA, Senchenkova SN, L'Vov VL, Shashkov AS, Feng L, Aparin PG, Wang L, Knirel YA. 2012. Shigella flexneri O-antigens revisited: final elucidation of the O-acetylation profiles and a survey of the O-antigen structure diversity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 66:201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlin NI, Lindberg AA. 1987. Monoclonal antibodies specific for Shigella flexneri lipopolysaccharides: clones binding to type IV, V, and VI antigens, group 3,4 antigen, and an epitope common to all Shigella flexneri and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 stains. Infect Immun 55:1412–1420. doi: 10.1128/IAI.55.6.1412-1420.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allison GE, Verma NK. 2000. Serotype-converting bacteriophages and O-antigen modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol 8:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Knirel YA, Lan R, Senchenkova SN, Luo X, Perepelov AV, Wang Y, Shashkov AS, Xu J, Sun Q. 2014. Identification of an O-acyltransferase gene (oacB) that mediates 3- and 4-O-acetylation of rhamnose III in Shigella flexneri O antigens. J Bacteriol 196:1525–1531. doi: 10.1128/JB.01393-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Q, Knirel YA, Wang J, Luo X, Senchenkova SN, Lan R, Shashkov AS, Xu J. 2014. Serotype-converting bacteriophage SfII encodes an acyltransferase protein that mediates 6-O-acetylation of GlcNAc in Shigella flexneri O-antigens, conferring on the host a novel O-antigen epitope. J Bacteriol 196:3656–3666. doi: 10.1128/JB.02009-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenne L, Lindberg B, Petersson K, Katzenellenbogen E, Romanowska E. 1978. Structural studies of Shigella flexneri O-antigens. Eur J Biochem 91:279–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb20963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster RA, Carlin NI, Majcher M, Tabor H, Ng LK, Widmalm G. 2011. Structural elucidation of the O-antigen of the Shigella flexneri provisional serotype 88-893: structural and serological similarities with S. flexneri provisional serotype Y394 (1c). Carbohydr Res 346:872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakhetia R, Marri A, Stahle J, Widmalm G, Verma NK. 2014. Serotype-conversion in Shigella flexneri: identification of a novel bacteriophage, Sf101, from a serotype 7a strain. BMC Genomics 15:742. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mavris M, Manning PA, Morona R. 1997. Mechanism of bacteriophage SfII-mediated serotype conversion in Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol 26:939–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6301997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Q, Lan R, Wang Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Li P, Du P, Xu J. 2013. Isolation and genomic characterization of SfI, a serotype-converting bacteriophage of Shigella flexneri. BMC Microbiol 13:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan S, Bastin DA, Verma NK. 1999. Functional analysis of the O antigen glucosylation gene cluster of Shigella flexneri bacteriophage SfX. Microbiology 145:1263–1273. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison GE, Angeles D, Tran-Dinh N, Verma NK. 2002. Complete genomic sequence of SfV, a serotype-converting temperate bacteriophage of Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol 184:1974–1987. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.7.1974-1987.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adhikari P, Allison G, Whittle B, Verma NK. 1999. Serotype 1a O-antigen modification: molecular characterization of the genes involved and their novel organization in the Shigella flexneri chromosome. J Bacteriol 181:4711–4718. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.15.4711-4718.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams MM, Allison GE, Verma NK. 2001. Type IV O antigen modification genes in the genome of Shigella flexneri NCTC 8296. Microbiology 147:851–860. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wehler T, Carlin NI. 1988. Structural and immunochemical studies of the lipopolysaccharide from a new provisional serotype of Shigella flexneri. Eur J Biochem 176:471–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stagg RM, Tang SS, Carlin NI, Talukder KA, Cam PD, Verma NK. 2009. A novel glucosyltransferase involved in O-antigen modification of Shigella flexneri serotype 1c. J Bacteriol 191:6612–6617. doi: 10.1128/JB.00628-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perepelov AV, L'Vov VL, Liu B, Senchenkova SN, Shekht ME, Shashkov AS, Feng L, Aparin PG, Wang L, Knirel YA. 2009. A new ethanolamine phosphate-containing variant of the O-antigen of Shigella flexneri type 4a. Carbohydr Res 344:1588–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Q, Knirel YA, Lan R, Wang J, Senchenkova SN, Jin D, Shashkov AS, Xia S, Perepelov AV, Chen Q, Wang Y, Wang H, Xu J. 2012. A novel plasmid-encoded serotype conversion mechanism through addition of phosphoethanolamine to the O-antigen of Shigella flexneri. PLoS One 7:e46095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Q, Lan R, Wang J, Xia S, Wang Y, Wang Y, Jin D, Yu B, Knirel YA, Xu J. 2013. Identification and characterization of a novel Shigella flexneri serotype Yv in China. PLoS One 8:e70238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knirel YA, Lan R, Senchenkova SN, Wang J, Shashkov AS, Wang Y, Perepelov AV, Xiong Y, Xu J, Sun Q. 2013. O-antigen structure of Shigella flexneri serotype Yv and effect of the lpt-O gene variation on phosphoethanolamine modification of S. flexneri O-antigens. Glycobiology 23:475–485. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubler-Kielb J, Vinogradov E, Chu C, Schneerson R. 2007. O-Acetylation in the O-specific polysaccharide isolated from Shigella flexneri serotype 2a. Carbohydr Res 342:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perepelov AV, L'Vov VL, Liu B, Senchenkova SN, Shekht ME, Shashkov AS, Feng L, Aparin PG, Wang L, Knirel YA. 2009. A similarity in the O-acetylation pattern of the O-antigens of Shigella flexneri types 1a, 1b, and 2a. Carbohydr Res 344:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West NP, Sansonetti P, Mounier J, Exley RM, Parsot C, Guadagnini S, Prevost MC, Prochnicka-Chalufour A, Delepierre M, Tanguy M, Tang CM. 2005. Optimization of virulence functions through glucosylation of Shigella LPS. Science 307:1313–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1108472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohler H, Rodrigues SP, McCormick BA. 2002. Shigella flexneri interactions with the basolateral membrane domain of polarized model intestinal epithelium: role of lipopolysaccharide in cell invasion and in activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK. Infect Immun 70:1150–1158. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.3.1150-1158.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong M, Payne SM. 1997. Effect of mutations in Shigella flexneri chromosomal and plasmid-encoded lipopolysaccharide genes on invasion and serum resistance. Mol Microbiol 24:779–791. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3731744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunther SD, Fritsch M, Seeger JM, Schiffmann LM, Snipas SJ, Coutelle M, Kufer TA, Higgins PG, Hornung V, Bernardini ML, Honing S, Kronke M, Salvesen GS, Kashkar H. 2020. Cytosolic Gram-negative bacteria prevent apoptosis by inhibition of effector caspases through lipopolysaccharide. Nat Microbiol 5:354–367. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthuirulandi Sethuvel DP, Devanga Ragupathi NK, Anandan S, Veeraraghavan B. 2017. Update on: Shigella new serogroups/serotypes and their antimicrobial resistance. Lett Appl Microbiol 64:8–18. doi: 10.1111/lam.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Q, Lan R, Wang Y, Zhao A, Zhang S, Wang J, Wang Y, Xia S, Jin D, Cui Z, Zhao H, Li Z, Ye C, Zhang S, Jing H, Xu J. 2011. Development of a multiplex PCR assay targeting O-antigen modification genes for molecular serotyping of Shigella flexneri. J Clin Microbiol 49:3766–3770. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01259-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Das A, Mandal J. 2019. Extensive inter-strain diversity among clinical isolates of Shigella flexneri with reference to its serotype, virulence traits and plasmid incompatibility types, a study from south India over a 6-year period. Gut Pathog 11:33. doi: 10.1186/s13099-019-0314-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark CA, Beltrame J, Manning PA. 1991. The oac gene encoding a lipopolysaccharide O-antigen acetylase maps adjacent to the integrase-encoding gene on the genome of Shigella flexneri bacteriophage Sf6. Gene 107:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90295-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindberg AA, Wollin R, Gemski P, Wohlhieter JA. 1978. Interaction between bacteriophage Sf6 and Shigella flexneri. J Virol 27:38–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.27.1.38-44.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chua JE, Manning PA, Morona R. 1999. The Shigella flexneri bacteriophage Sf6 tailspike protein (TSP)/endorhamnosidase is related to the bacteriophage P22 TSP and has a motif common to exo- and endoglycanases, and C-5 epimerases. Microbiology 145:1649–1659. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parent KN, Erb ML, Cardone G, Nguyen K, Gilcrease EB, Porcek NB, Pogliano J, Baker TS, Casjens SR. 2014. OmpA and OmpC are critical host factors for bacteriophage Sf6 entry in Shigella. Mol Microbiol 92:47–60. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubler-Kielb J, Vinogradov E, Mocca C, Pozsgay V, Coxon B, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. 2010. Immunochemical studies of Shigella flexneri 2a and 6, and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 O-specific polysaccharide-core fragments and their protein conjugates as vaccine candidates. Carbohydr Res 345:1600–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gemski P Jr, Koeltzow DE, Formal SB. 1975. Phage conversion of Shigella flexneri group antigens. Infect Immun 11:685–691. doi: 10.1128/IAI.11.4.685-691.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Day CJ, Tran EN, Semchenko EA, Tram G, Hartley-Tassell LE, Ng PS, King RM, Ulanovsky R, McAtamney S, Apicella MA, Tiralongo J, Morona R, Korolik V, Jennings MP. 2015. Glycan:glycan interactions: high affinity biomolecular interactions that can mediate binding of pathogenic bacteria to host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E7266–7275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421082112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morona R, Daniels C, van Den Bosch L. 2003. Genetic modulation of Shigella flexneri 2a lipopolysaccharide O antigen modal chain length reveals that it has been optimized for virulence. Microbiology (Reading) 149:925–939. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Lan R, Knirel YA, Luo X, Senchenkova SN, Shashkov AS, Xu J, Sun Q. 2014. Serological identification and prevalence of a novel O-antigen epitope linked to 3- and 4-O-acetylated rhamnose III of lipopolysaccharide in Shigella flexneri. J Clin Microbiol 52:2033–2038. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00197-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hlozek J, Ravenscroft N, Kuttel MM. 2020. Effects of glucosylation and O-acetylation on the conformation of Shigella flexneri serogroup 2 O-antigen vaccine targets. J Phys Chem B 124:2806–2814. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kunstmann S, Scheidt T, Buchwald S, Helm A, Mulard LA, Fruth A, Barbirz S. 2018. Bacteriophage Sf6 tailspike protein for detection of Shigella flexneri pathogens. Viruses 10:431. doi: 10.3390/v10080431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golomidova A, Kulikov E, Prokhorov N, Guerrero-Ferreira R, Knirel Y, Kostryukova E, Tarasyan K, Letarov A. 2016. Branched lateral tail fiber organization in T5-like bacteriophages DT57C and DT571/2 is revealed by genetic and functional analysis. Viruses 8:26. doi: 10.3390/v8010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gauthier C, Chassagne P, Theillet FX, Guerreiro C, Thouron F, Nato F, Delepierre M, Sansonetti PJ, Phalipon A, Mulard LA. 2014. Non-stoichiometric O-acetylation of Shigella flexneri 2a O-specific polysaccharide: synthesis and antigenicity. Org Biomol Chem 12:4218–4232. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42586j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen JH, Hsu WB, Chiou CS, Chen CM. 2003. Conversion of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a to serotype Y in a shigellosis patient due to a single amino acid substitution in the protein product of the bacterial glucosyltransferase gtrII gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett 224:277–283. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun Q, Knirel YA, Lan R, Wang J, Senchenkova SN, Shashkov AS, Wang Y, Wang Y, Luo X, Xu J. 2014. Dissemination and serotype modification potential of pSFxv_2, an O-antigen PEtN modification plasmid in Shigella flexneri. Glycobiology 24:305–313. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang C, Li P, Zhang X, Ma Q, Cui X, Li H, Liu H, Wang J, Xie J, Wu F, Sheng C, Du X, Qi L, Su W, Jia L, Xu X, Zhao J, Xia S, Zhou N, Ma H, Qiu S, Song H. 2016. Molecular characterization and analysis of high-level multidrug-resistance of Shigella flexneri serotype 4s strains from China. Sci Rep 6:29124. doi: 10.1038/srep29124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morona R, van den Bosch L, Manning PA. 1995. Molecular, genetic, and topological characterization of O-antigen chain length regulation in Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol 177:1059–1068. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1059-1068.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baker SJ, Gunn JS, Morona R. 1999. The Salmonella typhi melittin resistance gene pqaB affects intracellular growth in PMA-differentiated U937 cells, polymyxin B resistance and lipopolysaccharide. Microbiology 145:367–378. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teh MY, Tran EN, Morona R. 2012. Absence of O antigen suppresses Shigella flexneri IcsA autochaperone region mutations. Microbiology (Reading) 158:2835–2850. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morona R, van den Bosch L. 2003. Lipopolysaccharide O antigen chains mask IcsA (VirG) in Shigella flexneri. FEMS Microbiol Lett 221:173–180. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freiberg A, Morona R, van den Bosch L, Jung C, Behlke J, Carlin N, Seckler R, Baxa U. 2003. The tailspike protein of Shigella phage Sf6. A structural homolog of Salmonella phage P22 tailspike protein without sequence similarity in the beta-helix domain. J Biol Chem 278:1542–1548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teh MY, Morona R. 2013. Identification of Shigella flexneri IcsA residues affecting interaction with N-WASP, and evidence for IcsA-IcsA co-operative interaction. PLoS One 8:e55152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oaks EV, Wingfield ME, Formal SB. 1985. Plaque formation by virulent Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun 48:124–129. doi: 10.1128/IAI.48.1.124-129.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.